The 1856 Reservation for Chief Buffalo’s Estate

November 5, 2025

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

This is one of many posts on Chequamegon History exploring the original La Pointe Band Reservations of La Pointe County on Chequamegon Bay, now known as the Bad River and Red Cliff Reservations. Specifically, today’s post is about the 1856 Reservation for Chief Buffalo’s subdivision of the La Pointe Band and how it got selected in accordance with the Sixth Clause of the Second Article of the 1854 Treaty with the Chippewa at La Pointe:

1854 Treaty with the Chippewa at La Pointe

…

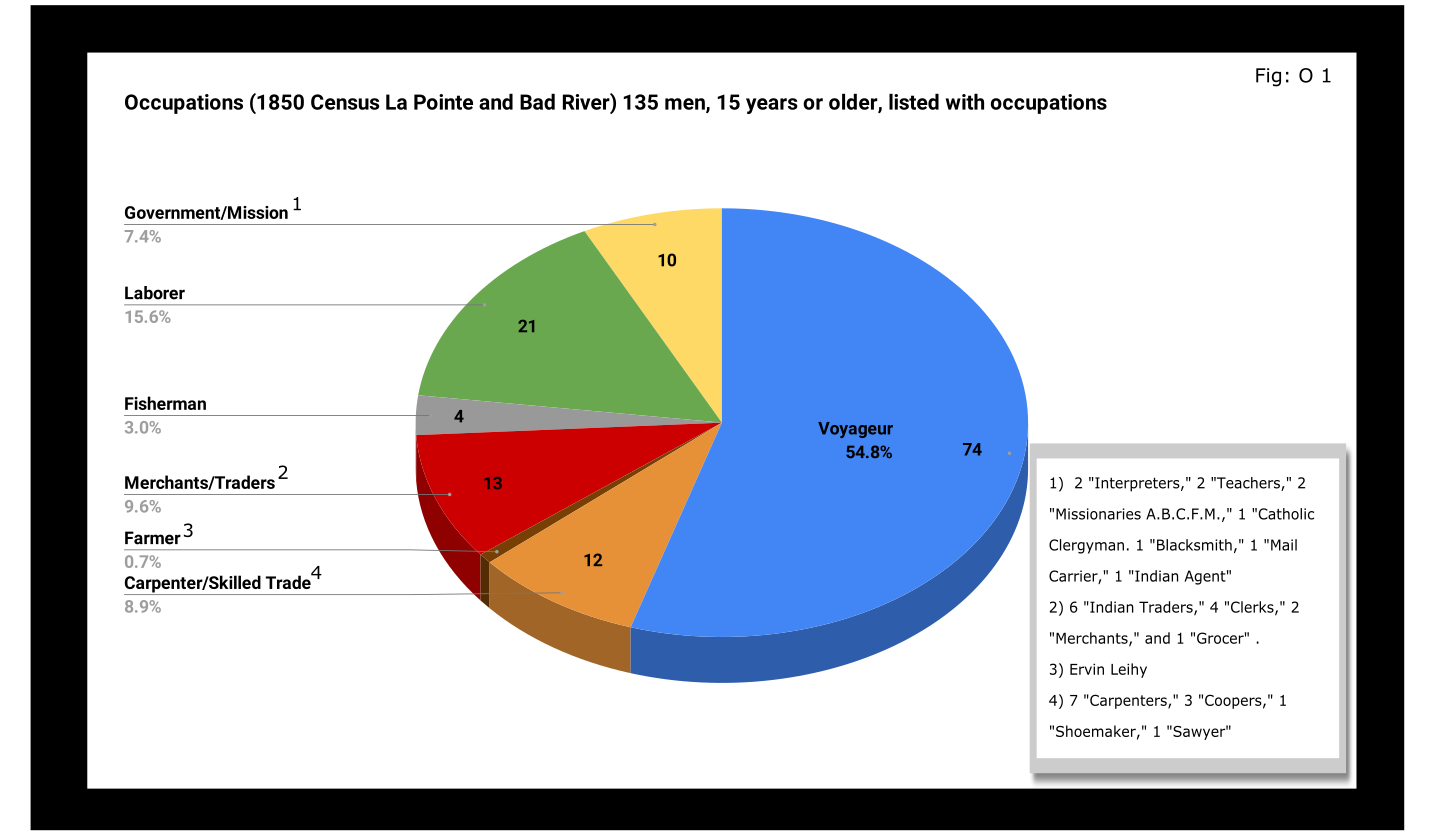

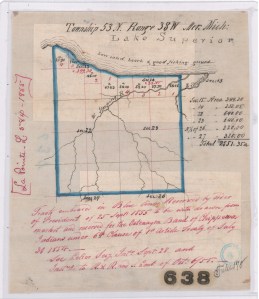

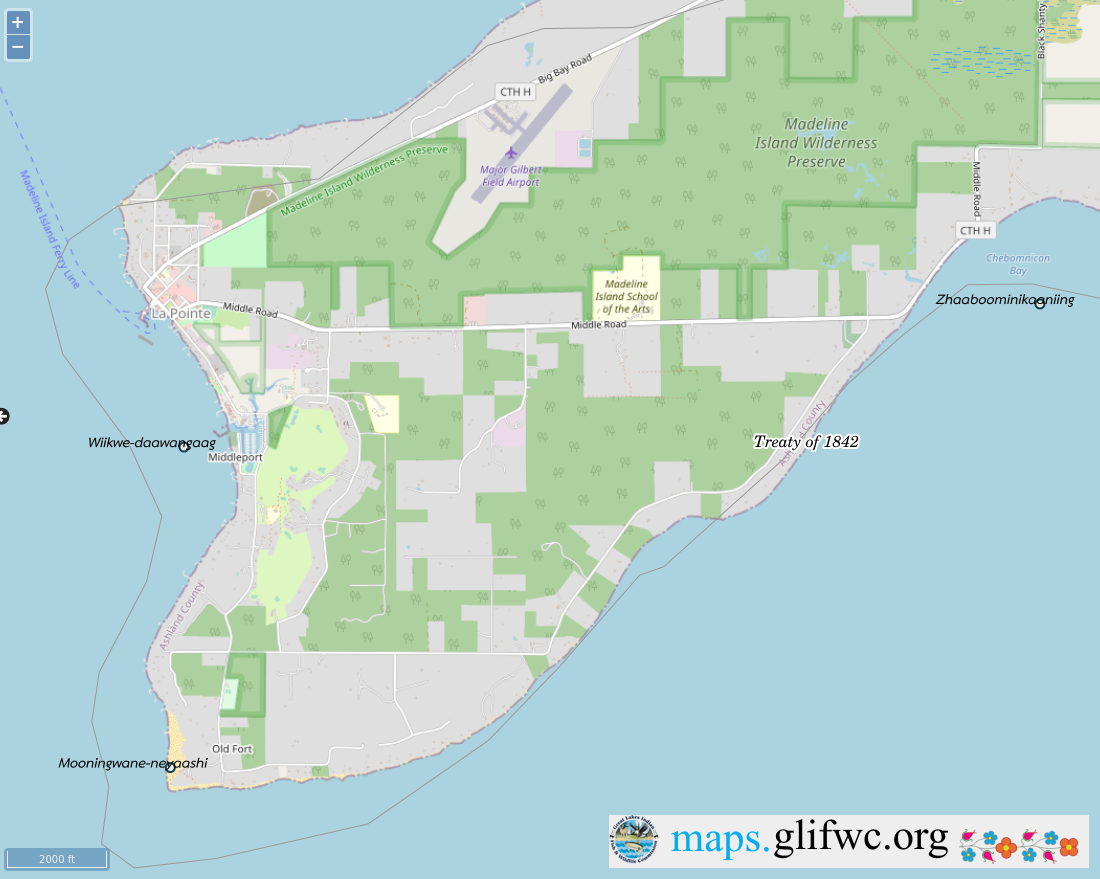

Map of La Pointe Band Reservations:

334 – Bad River Reservation

335 – La Pointe Fishing Reservation

341 – Chief Buffalo’s Reservation

342 – Red Cliff Reservation

18th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1896-’97

Printed by U.S. Congress in 1899

ARTICLE 2. The United States agree to set apart and withhold from sale, for the use of the Chippewas of Lake Superior, the following-described tracts of land, viz:

…

6th [Clause]. The Ontonagon band and that subdivision of the La Pointe band of which Buffalo is chief, may each select, on or near the lake shore, four sections of land, under the direction of the President, the boundaries of which shall be defined hereafter. And being desirous to provide for some of his connections who have rendered his people important services, it is agreed that the chief Buffalo may select one section of land, at such place in the ceded territory as he may see fit, which shall be reserved for that purpose, and conveyed by the United States to such person or persons as he may direct.

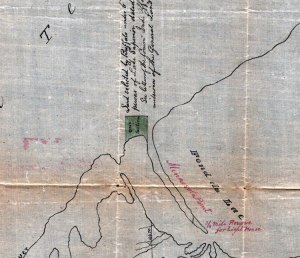

Map of “Tract embraced in blue lines reserved by order of President of 25 September 1855 to be withdrawn from market and reserved for the Ontonagon Band of Chippewa Indians“ on a “low sand beach & good fishing ground”.

Central Map File No. 638 (Tube No. 138)

NAID: 232923886 cites “La Pointe L.584-1855”.

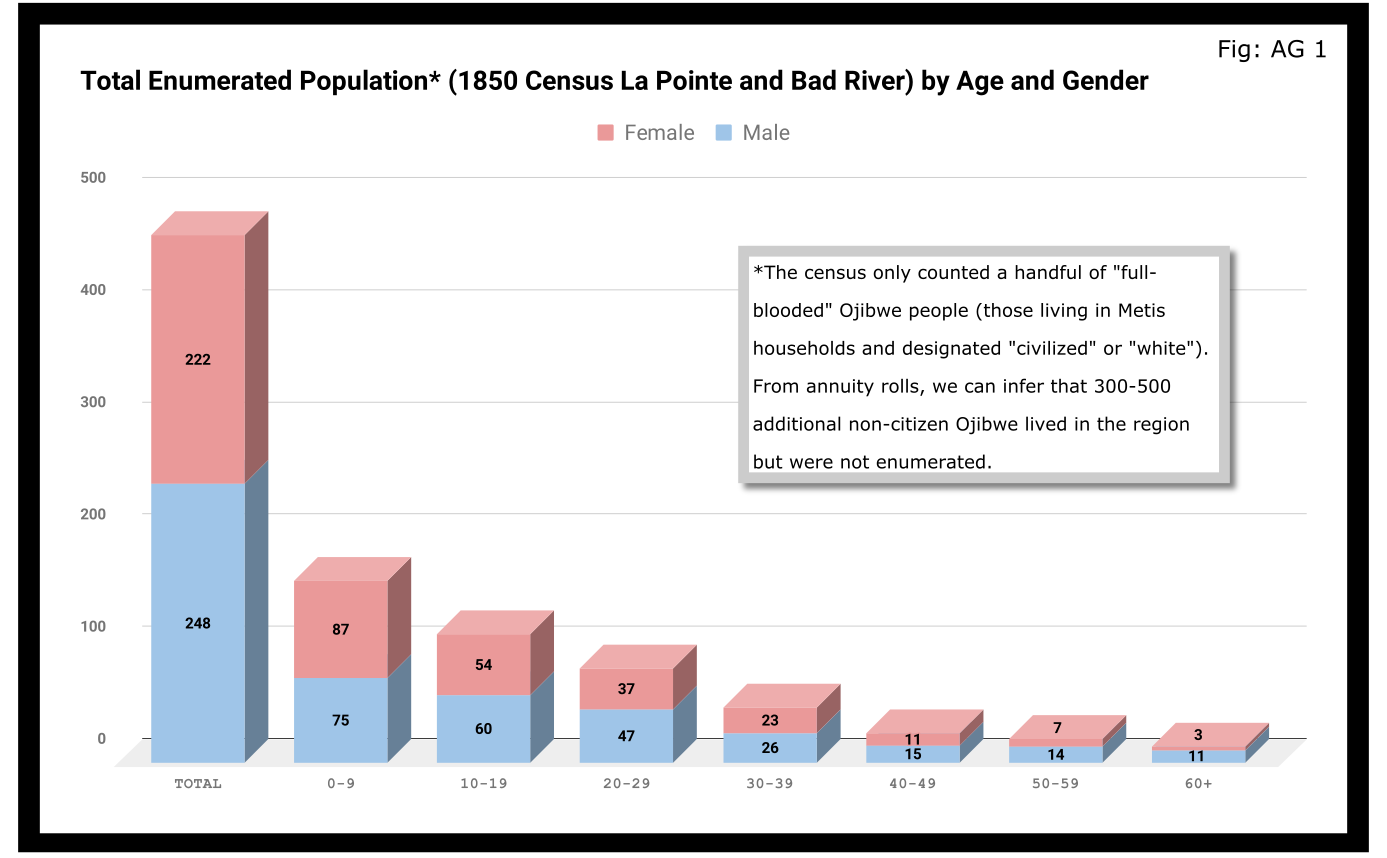

The Ontonagon Band and Chief Buffalo’s Subdivision of the La Pointe Band got lumped together in this clause, so let’s review the Ontonagon Band first. Less than one year after the 1854 Treaty, the Ontonagon Band selected four square miles for their Reservation as approved by President Franklin Pierce’s Executive Order of September 25, 1855. Today the Ontonagon Band Reservation still has its original shape and size from 1855 despite heavy “checkerboarding” of its landownership over time.

In comparison to the Ontonagon Band Reservation, the history of how Chief Buffalo’s Reservation got selected is not so straightforward. Despite resisting and surviving the Sandy Lake Tragedy and Ojibwe Removal, making an epic trip to meet the President at Washington D.C., and securing Reservations as permanent homelands for the Chippewa Bands in the 1854 Treaty, Chief Buffalo of La Pointe died in 1855 before being able to select four square miles for his Subdivsion of the La Pointe Bands.

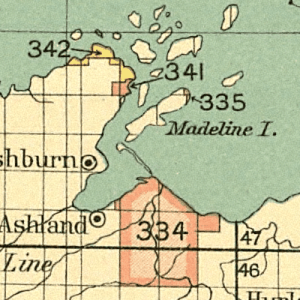

Fortunately, President Franklin Pierce’s Executive Order of February 21, 1856 withheld twenty-two square miles of land near the Apostle Islands from federal public land sales, allowing Chief Buffalo’s Estate to select four of those twenty-two square miles for their Reservation without competition from squatters and other land speculators, while other prime real estate in the ceded territory of La Pointe County was being surveyed and sold to private landowners by the United States General Land Office.

This 1856 Reservation of twenty-two square miles for Chief Buffalo’s Estate set the stage for what would eventually become the Red Cliff Reservation. We will return to this 1856 Reservation for Chief Buffalo’s Estate in several upcoming posts exploring more records about Red Cliff and the other La Pointe Band Reservations.

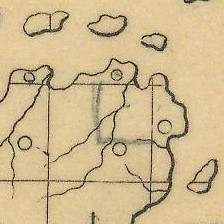

Maps marked “A” showing certain lands reserved by the 1854 Treaty:

Central Map File No. 793 (Tube 446)

NAID: 232924228 cites “La Pointe L.579-1855″.

Central Map File No. 816 (Tube 298)

NAIDs: 232924272 & 50926136 cites “Res. Chippewa L.516-1855”.

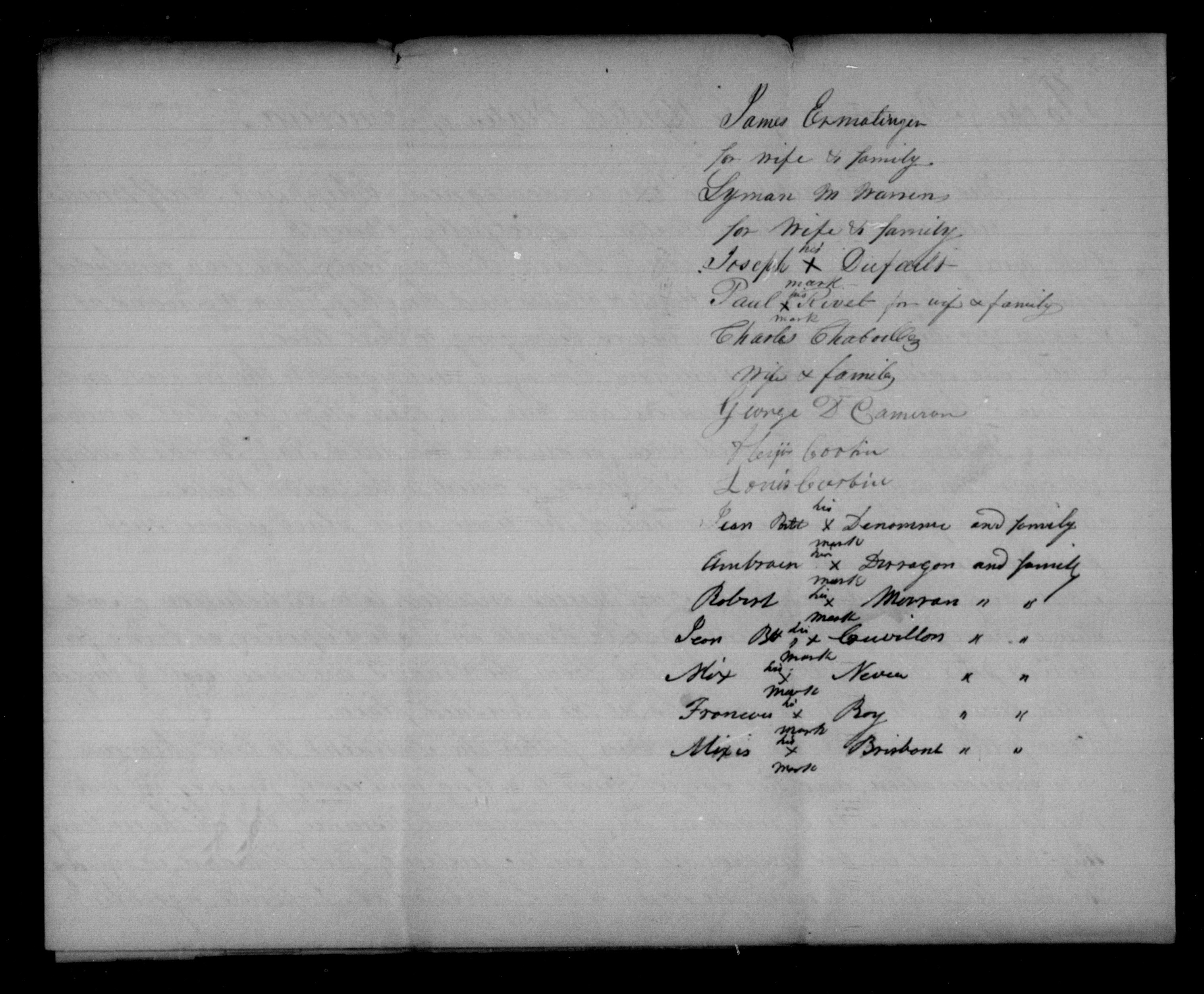

1878 Copy of President Franklin Pierce’s Executive Order of February 26, 1856 for Chief Buffalo’s Subdivision (aka “Red Cliff”).

NAID: 117092990

Office of Indian Affairs.

(Miscellaneous)

L.801.17.1878

Copy of Ex. Order of Feby. 21. 1856.

Chippewas (Red Cliff.)

Wisconsin.

Enc. in G.L.O. letter of Nov 23, 1878 (above file mark.)

in answer to office letter of Nov. 18, 1878.

Ex. Order File.

Department of the Interior

February 21, 1856

Sir,

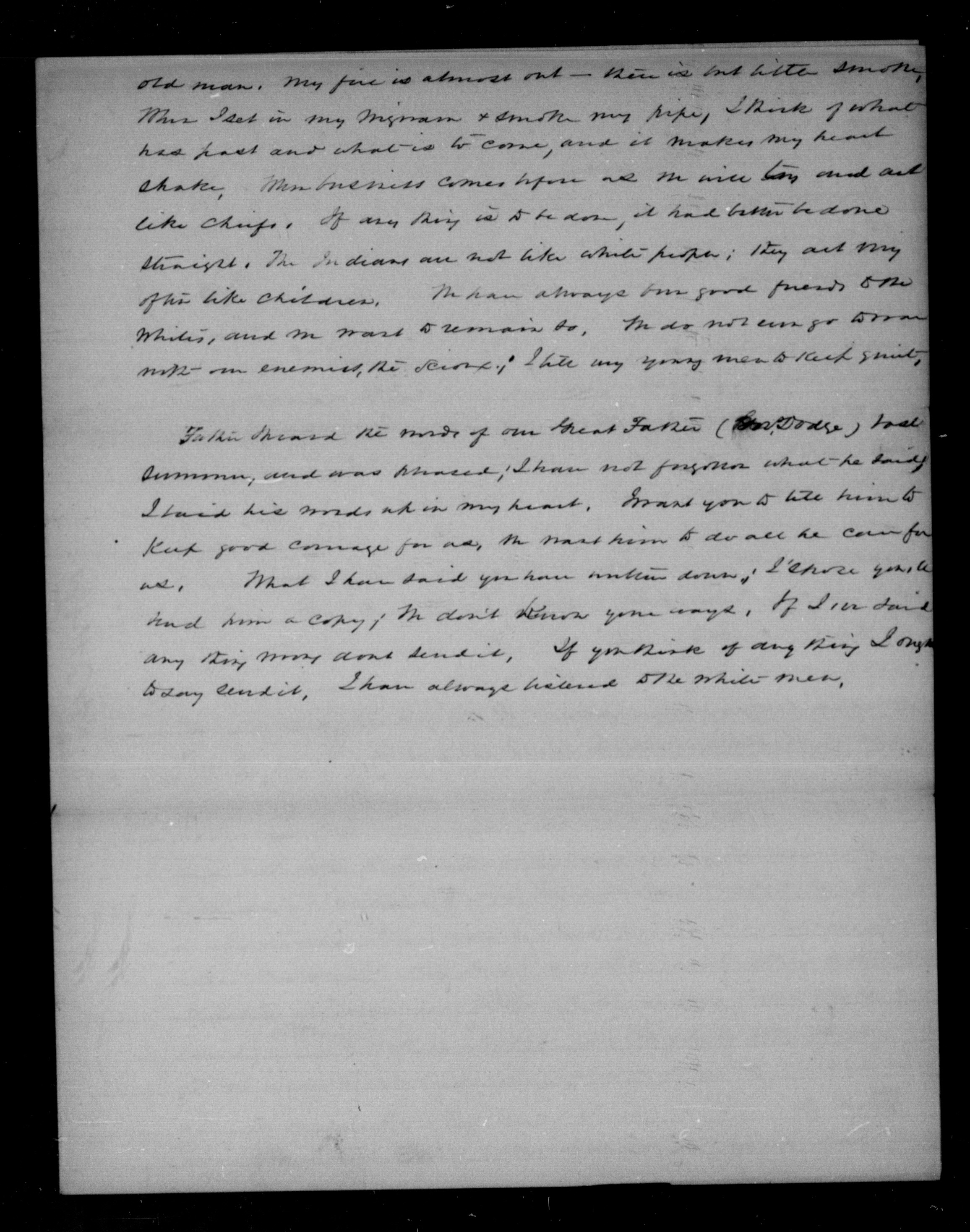

I herewith return the diagram enclosed in your letter of the 20th inst, covering duplicates of documents which accompanied your letter of the 6th Sept. last, as well as a copy of the latter, the originals of which were submitted to the President in letter from the Department of the 8th Sept. last and cannot now be found.

You will find endorsements on said diagram explanatory of the case and an order of the President of this date for the withdrawal of the land in question for Indian purposes as recommended.

Respectfully

Your obt. Servt

R McClelland

Secretary

To

Hon Thos A Hendrick

Commissioner of the

General Land Office

(Copy)

General Land Office

September 6, 1855

Hon R. McClelland

Sec. of Interior

Sir:

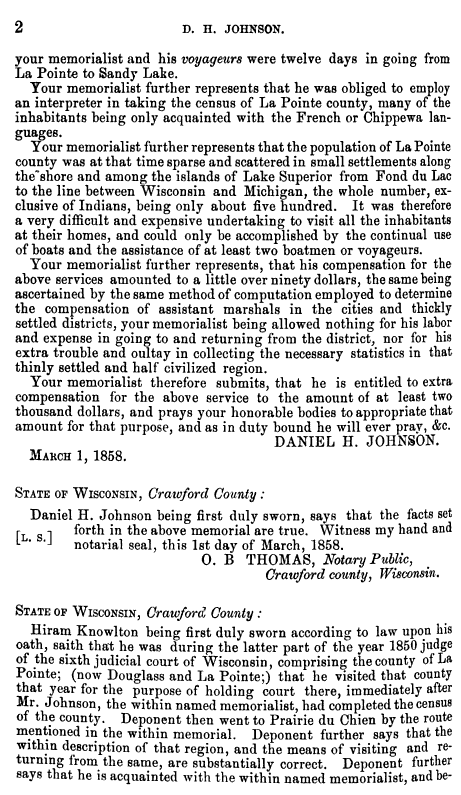

Enclosed I have the honor to submit an abstract from the Acting Commissioner of Indian Affairs letter of the 5th instant, requesting the withdrawal of certain lands for the Chippewa Indians in Wisconsin, under the Treaty of September 30th, 1854, referred by the Department to this office on the 5th. instant, with orders to take immediate steps for the withdrawal of the lands from sale.

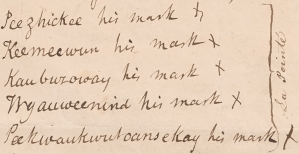

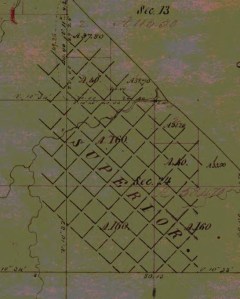

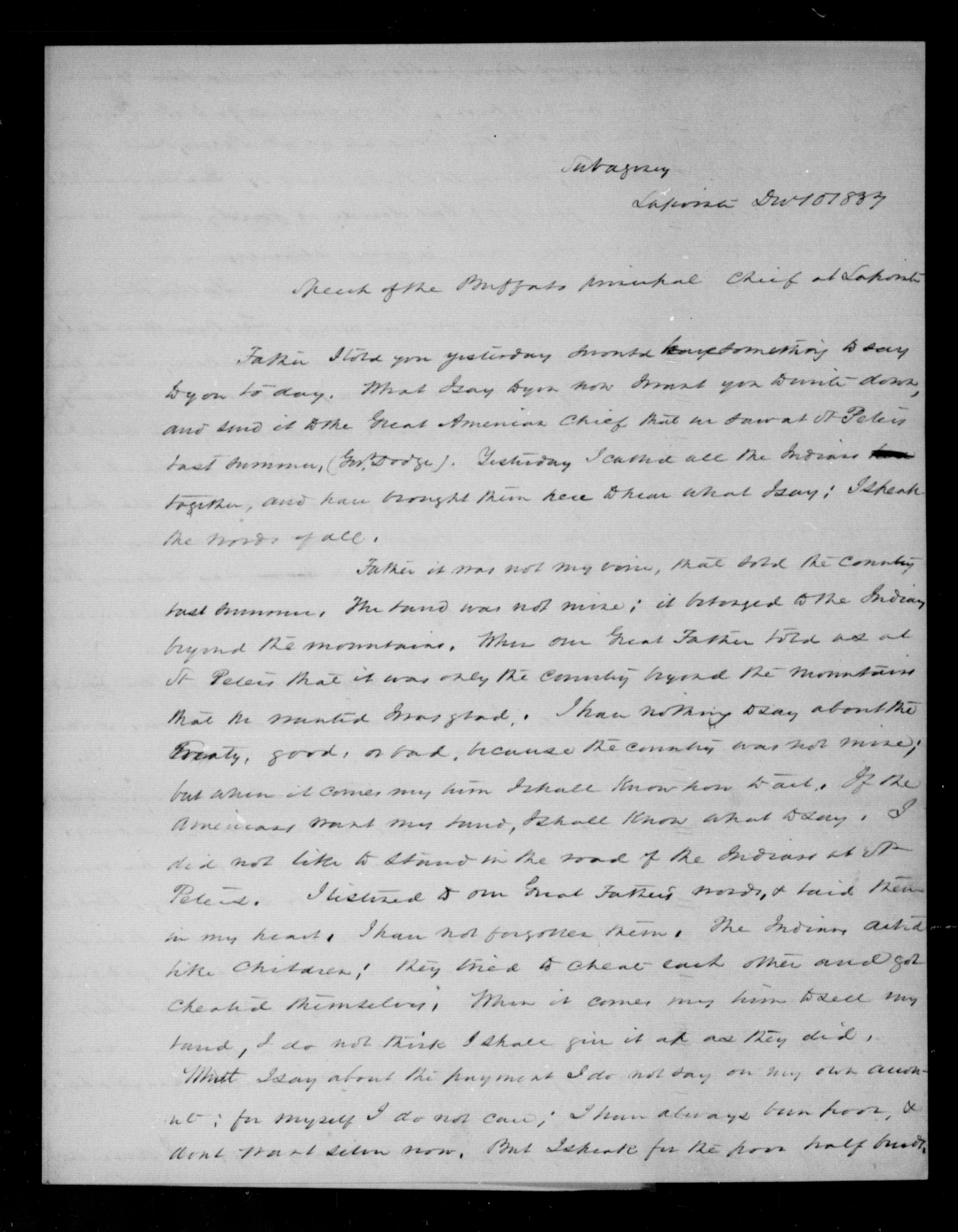

Detail of 1856 Reservation in pencil on “a map marked A.“

Central Map File No. 816 (Tube 298)

NAIDs: 232924272 & 50926136 cites “Res. Chippewa L.516-1855”.

In obedience to the above order I herewith enclose a map marked A. Showing by the blue shades thereon, the Townships and parts of Townships desired to be reserved, no portion of which are yet in market, to wit:

Township 51 N. of Range 3 West 4th Prin. Mer. Wis.

N.E. ¼ of Town 51 N ” 4 ” ” ” “.

Township 52 ” ” 3 & 4 ” ” ” “.

For the reservation of which, until the contemplated Selections under the 6th Clause of the Chippewa Treaty of 30th September 1854 can be made, I respectfully recommend that the order of the President may be obtained.

The requisite reports on the subject of the new surveys, and respecting preemption claims, referred to in the same order, will be prepared and communicated at an early day.

I am respectfully

Your Ob’t Serv’t

Thos. A. Hendricks

Commissioner

Department of the Interior

Feb. 20. 1856

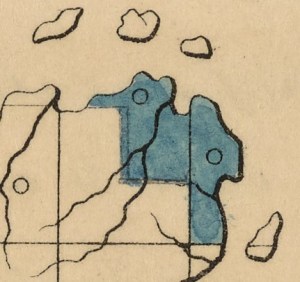

Detail of 1856 Reservation in blue on “duplicate of the original“.

NAID: 117092990

This plat represents by the blue shade, certain land to be withdrawn with a view to a reservation, under Chippewa Treaty of 30 Sept 1854, and as more particularly described in Commissioner of the General Land Office in letter of 6th Sept 1855. The subject was referred to the President for his sanction of the recommendation made in Secretary’s letter of 8th Sept 1855 and the original papers cannot now be found. This is a duplicate of the original, received in letter of Comm’r of the General Land Office of this date and is recommended to the President for his sanction of the withdrawal desired.

R. McClelland

Secretary

1856 Reservation in red and modern Red Cliff in brown. Although different in shape, both are roughly twenty-two square miles in size.

February 21st 1856

Let the withdrawal be made as recommended.

Franklin Pierce

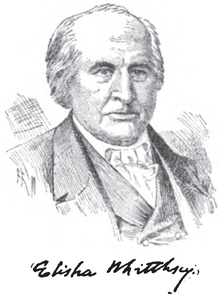

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Coda

June 1, 2024

My last post ended up containing several musings on the nature of primary-source research and how to acknowledge mistakes and deal with uncertainty in the historical record. This was in anticipation of having to write this post. It’s a post I’ve been putting off for years.

Amorin forced the issue with his important work on the speeches at the 1842 Treaty negotiations. While working on it, he sent me a message that read something like, “Hey, the article quotes Chief Buffalo and describes him in a blue military coat with epaulets. Is the world ready for that picture that Smithsonian guy sent us years ago?”

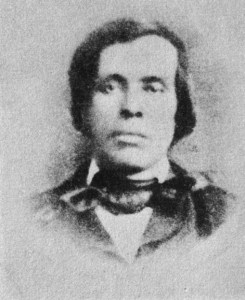

This was the image in question:

Henry Inman, Big Buffalo (Chippewa), 1832-1833, oil on canvas, frame: 39 in. × 34 in. × 2 1/4 in. (99.1 × 86.4 × 5.7 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Gerald and Kathleen Peters, 2019.12.2

We first learned of this image from a Chequamegon History comment by Patrick Jackson of the Smithsonian asking what we knew about the image and whether or not it was Chief Buffalo from La Pointe.

We had never seen it before.

This was our correspondence with Mr. Jackson at the time:

July 17, 2019

Hello, my name is Patrick, and I am an intern at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I’m working on researching a recent acquisition: a painting which came to us identified as a Henry Inman portrait of “Big Buffalo Ke-Che-Wais-Ke, The Great Renewer (1759-1855) (Chippewa).” We have run into some confusion about the identification of the portrait, as it came to us identified as stated above, yet at Harvard Peabody Museum, who was previously the owner of the portrait, it was listed as an unidentified sitter. Seeing as you’ve written a few posts about the identification of images of the three different Chief Buffalos, I thought you might be able to give some insight into perhaps who is or isn’t in the portrait we have. Thank you for your time.

July 17, 2019

Hello,

I would be happy to comment. Can you send a photo to this email?

I am pretty sure Inman painted a copy of Charles Bird King’s portrait of Pee-che-kir.

Doe it resemble that portrait? Pee-che-kir (Bizhiki) means Buffalo in Ojibwe (Chippewa). From my research, I am fairly certain that King’s portrait is not of Kechewaiske, but of another chief named Buffalo who lived in the same era.

Leon Filipczak

July 17, 2019

Dear Leon,

I have attached our portrait—it’s not the best scan, but hopefully there’s enough detail for you to work with. I’ve compared it with the Peechikir in McKenney & Hall, as well as to the Chief Buffalo painted ambrotype and the James Otto Lewis portrait of Pe-schick-ee. The ambrotype has a close resemblance, as does the Peecheckir, though if that is what Charles Bird King painted I have doubts that Inman would make such drastic changes in clothing and pose.

The identification as Big Buffalo/Ke-Che-Wais-Ke/The Great Renewer, as far as I understand, refers to the La Pointe Bizhiki/Buffalo rather than the St. Croix or Leech Lake Buffalos, though of course that is a questionable identification considering Kechewaiske did not (I think) visit Washington until after Inman’s death in January of 1846. McKenney, however, did visit the Ojibwe/Chippewa for the negotiations for the Treaty of Fond du Lac in 1825/1826, and could feasibly have met multiple Chief Buffalos. Perhaps a local artist there would be responsible for the original? Another possibility is, since the identification was not made at the Peabody, who had the portrait since the 1880s, is that it has been misidentified entirely and is unrelated to any of the Ojibwe/Chippewa chiefs. Though this, to me, would seem unlikely considering the strong resemblance of the figure in our portrait to the Peechikir portrait and Chief Buffalo ambrotype.

Thank you again for the help.

Sincerely,

Patrick

July 22, 2019

Hello Patrick,

This is a head-scratcher. Your analysis is largely what I would come up with. My first thought when I saw it was, “Who identified it as someone named Buffalo? When? and using what evidence?” Whoever associated the image with the text “Ke-Che-Wais-Ke, The Great Renewer (1759-1855)” did so decades after the painting could be assumed to be created. However, if the tag “Big Buffalo” can be attached to this image in the era it was created, then we may be onto something. This is what I know:

1) During his time as Superintendent of Indian Affairs (late 1820s), Thomas McKenney amassed a large collection of portraits of Indian chiefs for what he called the “Indian Gallery” in the War Department. He sought the portraits out wherever and whenever he could. When chiefs would come to Washington, he would have Charles Bird King do the work, but he also received portraits from the interior via artists like James Otto Lewis.

2) In 1824, Bizhiki (Buffalo) from the St. Croix River (not Great Buffalo from La Pointe), visited Washington and was painted by King. This painting is presumed to have been destroyed in the Smithsonian fire that took out most of the Indian Gallery.

3) In 1825 at Prairie du Chien and in 1826 at Fond du Lac (where McKenney was present) James Otto Lewis painted several Ojibwe chiefs, and these paintings also ended up in the Indian Gallery. Both chief Buffalos were present at these treaties.

4) A team of artists copied each others’ work from these originals. King, for example remade several of Lewis’ portraits to make the faces less grotesque. Inman copied several Indian Gallery portraits (mostly King’s) to be sent to other institutions. These are the ones that survived the Smithsonian fire.

5) In the late 1830s, 10+ years after most of the portraits were painted, Lewis and McKenney sold competing lithograph collections to the American public. McKenney’s images were taken from the Indian Gallery. Lewis’ were from his works (some of which were in the Indian Gallery, often redone by King). While the images were printed with descriptions, the accuracy of the descriptions leaves something to be desired. A chief named Bizhiki appears in both Lewis and McKenney-Hall. In both, the chiefs are dressed in white and faced looking left, but their faces look nothing alike. One is very “Lewis-grotesque.” and the other is not at all. There are Lewis-based lithographs in both competing works, and they are usually easy to spot.

6) Not every image from the Indian Gallery made it into the published lithographic collections. Brian Finstad, a historian of the upper-St. Croix country, has shown me an image of Gaa-bimabi (Kappamappa, Gobamobi), a close friend/relative of the La Pointe Chief Buffalo, and upstream neighbor of the St. Croix Buffalo. This image is held by Harvard and strongly resembles the one you sent me in style. I suspect it is an Inman, based on a Lewis (possibly with a burned-up King copy somewhere in between).

7) “Big Buffalo” would seemingly indicate Buffalo from La Pointe. The word gichi is frequently translated as both “great” and “big” (i.e. big in size or big in power). Buffalo from La Pointe was both. However, the man in the painting you sent is considerably skinnier and younger-looking than I would expect him to appear c.1826.

My sense is that unless accompanying documentation can be found, there is no way to 100% ID these pictures. I am also starting to worry that McKenney and the Indian Gallery artists, themselves began to confuse the two chief Buffalos, and that the three originals (two showing St. Croix Buffalo, and one La Pointe Buffalo) burned. Therefore, what we are left with are copies that at best we are unable to positively identify, and at worst are actually composites of elements of portraits of two different men. The fact that King’s head study of Pee-chi-kir is out there makes me wonder if he put the face from his original (1824 portrait of St. Croix Buffalo?) onto the clothing from Lewis’ portrait of Pe-shick-ee when it was prepared for the lithograph publication.

A few weeks later, Patrick sent a follow-up message that he had tracked down a second version and confirmed that Inman’s portrait was indeed a copy of a Charles Bird King portrait, based on a James Otto Lewis original. It included some critical details.

Portrait of Big Buffalo, A Chippewa, 1827 Charles Bird King (1785-1862), signed, dated and inscribed ‘Odeg Buffalo/Copy by C King from a drawing/by Lewis/Washington 1826’ (on the reverse) oil on panel 17 1⁄2 X 13 3⁄4 in. (44.5 x 34.9 cm.) Last sold by Christie’s Auction House for $478,800 on 26 May 2022

The date of 1826 makes it very likely that Lewis’ original was painted at the Treaty of Fond du Lac. Chief Buffalo of La Pointe would have been in his 60s, which appears consistent with the image of Big Buffalo. Big Buffalo also does not appear as thin in King’s intermediate version as he does in Inman’s copy, lessening the concerns that the image does not match written descriptions of the chief.

Another clue is that it appears Lewis used the word Odeg to disambiguate Big Buffalo from the two other chiefs named Buffalo present at Fond du Lac in 1826. This may be the Ojibwe word Andeg (“crow”). Although I have not seen any other source that calls the La Pointe chief Andeg, it was a significant name in his family. He had multiple close relatives with Andeg in their names, which may have all stemmed from the name of Buffalo’s grandfather Andeg-wiiyaas (Crow’s Meat). As hereditary chief of the Andeg-wiiyaas band, it’s not unreasonable to think the name would stay associated with Buffalo and be used to distinguish him from the other Buffalos. However, this is speculative.

So, there we were. After the whole convoluted Chief Buffalo Picture Search, did we finally have an image we could say without a doubt was Chief Buffalo of La Pointe? No. However, we did have one we could say was “likely” or even “probably” him. I considered posting at the time, but a few things held me back.

In the earliest years of Chequamegon History, 2013 and 2014, many of the posts involved speculation about images and me trying to nitpick or disprove obvious research mistakes of others. Back then, I didn’t think anyone was reading and that the site would only appeal to academic types. Later on, however, I realized that a lot of the traffic to the site came from people looking for images, who weren’t necessarily reading all the caveats and disclaimers. This meant we were potentially contributing to the issue of false information on the internet rather than helping clear it up. So by 2019, I had switched my focus to archiving documents through the Chequamegon History Source Archive, or writing more overtly subjective and political posts.

So, the Smithsonian image of Big Buffalo went on the back burner, waiting to see if more information would materialize to confirm the identity of the man one way or the other. None did, and then in 2020 something happened that gave the whole world a collective amnesia that made those years hard to remember. When Amorin asked about using the image for his 1842 post, my first thought was “Yeah, you should, but we should probably give it its own post too.” My second thought was, “Holy crap! It’s been five years!”

Anyway, here is Chequamegon History’s statement on the identity of the man in Henry Inman’s 1832-33 portrait of Big Buffalo (Chippewa).

Likely Chief Buffalo of La Pointe: We are not 100% certain, but we are more certain than we have been about any other image featured in the Chief Buffalo Picture Search. This is a copy of a copy of a missing original by James Otto Lewis. Lewis was a self-taught artist who struggled with realistic facial features. Charles Bird King and Henry Inman, who made the first and second copies, respectively, had more talent for realism. However, they did not travel to Lake Superior themselves and were working from Lewis’ original. Therefore, the appearance of Big Buffalo may accurately show his clothing, but is probably less accurate in showing his actual physical appearance.

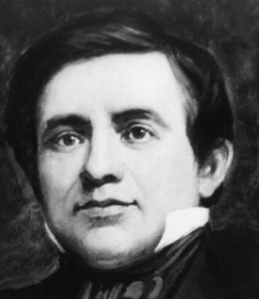

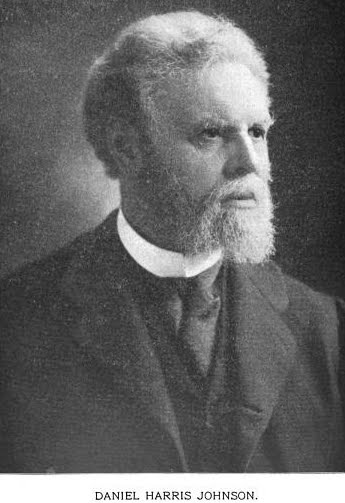

And while we’re on the subject of correcting misinformation related to images, I need to set the record straight on another one and offer my apologies to a certain Benjamin Green Armstrong. I promise, it relates indirectly to the “Big Buffalo” painting.

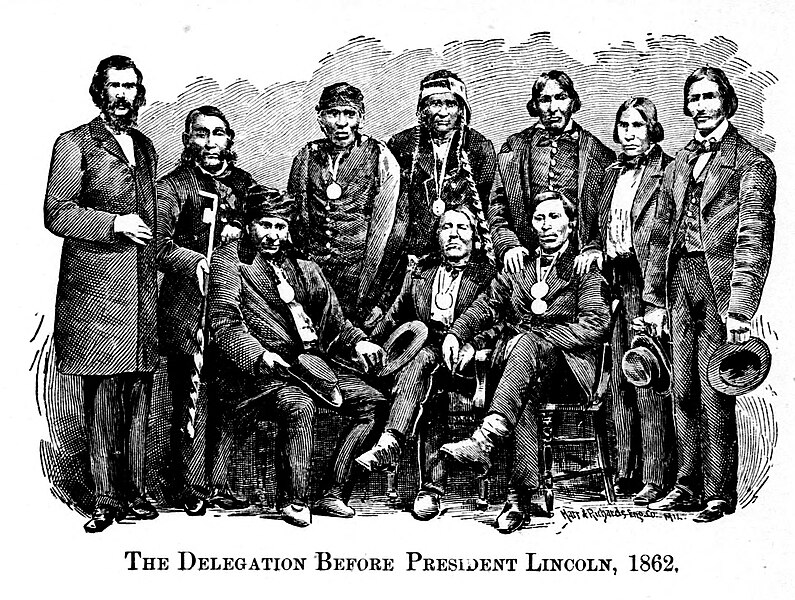

An engraving of the image in question appears in Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians.

Ah-moose (Little Bee) from Lac Flambeau Reservation, Kish-ke-taw-ug (Cut Ear) from Bad River Reservation, Ba-quas (He Sews) from Lac Courte O’Rielles Reservation, Ah-do-ga-zik (Last Day) from Bad River Reservation, O-be-quot (Firm) from Fond du Lac Reservation, Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation, Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell) from La Pointe Reservation, Na-gon-ab (He Sits Ahead) from Fond du Lac Reservation, and O-ma-shin-a-way (Messenger) from Bad River Reservation.

In this post, we contested these identifications on the grounds that Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Little Buffalo) from La Pointe Reservation died in 1860 and therefore could not have been part of the delegation to President Lincoln. In the comments on that post, readers from Michigan suggested that we had several other identities wrong, and that this was actually a group of chiefs from the Keweenaw region. We commented that we felt most of Armstrong’s identifications were correct, but that the picture was probably taken in 1856 in St. Paul.

Since then, a document has appeared that confirms Armstrong was right all along.

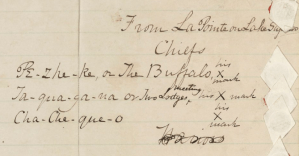

[Antoine Buffalo, Naagaanab, and six other chiefs to W.P. Dole, 6 March 1863

National Archives M234-393 slide 14

Transcribed by L. Filipczak 12 April 2024]

To Our Father,

Hon W P. Dole

Commissioner of Indian Affairs–

We the undersigned chiefs of the chippewas of Lake Superior, now present in Washington, do respectfully request that you will pay into the hands of our Agent L. E. Webb, the sum of Fifteen Hundred Dollars from any moneys found due us under the head of “Arrearages in Annuity” the said money to be expended in the purchase of useful articles to be taken by us to our people at home.

Antoine Buffalo His X Mark | A daw we ge zhig His X Mark

Naw gaw nab His X Mark | Obe quad His X Mark

Me zhe na way His X Mark | Aw ke wen zee His X Mark

Kish ke ta wag His X Mark | Aw monse His X Mark

I certify that I Interpreted the above to the chiefs and that the same was fully understood by them

Joseph Gurnoe

U.S. Interpreter

Witnessed the above Signed } BG Armstrong

Washington DC }

March 6th 1863 }

There were eight Lake Superior chiefs, an interpreter, and a witness in Washington that spring, for a total of ten people. There are ten people in the photograph. Chequamegon History is confident that this document confirms they are the exact ten identified by Benjamin Armstrong.

The Lac Courte Oreilles chief Ba-quas is the same person as Akiwenzii. It was not unusual for an Ojibwe chief to have more than one name. Chief Buffalo, Gaa-bimaabi, Zhingob the Younger, and Hole-in-the-Day the Younger are among the many examples.

The name “Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation” seems to be absent from the letter, but he is there too. Let’s look at the signature of the interpreter, Joseph Gurnoe.

Gurnoe’s beautiful looping handwriting will be familiar to anyone who has studied the famous 1864 bilingual petition. We see this same handwriting in an 1879 census of Red Cliff. In this document, Gurnoe records his own Ojibwe name as Shingwākons, The young Pine tree.

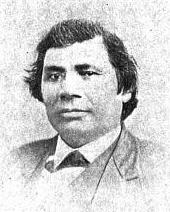

So the man standing on the far right is Gurnoe. This can be confirmed by looking at other known photos of him.

Finally, it confirms that the chief seated on the bottom left is not Jechiikwii’o (Little Buffalo), but rather his son Antoine, who inherited the chieftainship of the Buffalo Band after the death of his father two years earlier. Known to history as Chief Antoine Buffalo, in his lifetime he was often called Antoine Tchetchigwaio (or variants thereof), using his father’s name as a surname rather than his grandfather’s.

So, now we need to address the elephant in the room that unites the Henry Inman portrait of Big Buffalo with the photograph of the 1862-63 Delegation to Washington:

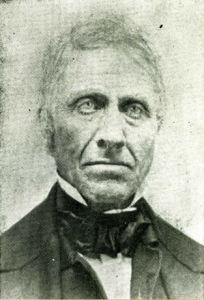

Wisconsin Historical Society

This is the “ambrotype” referenced by Patrick Jackson above. It’s the image most associated with Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. It’s also one for which we have the least amount of background information. We have not been able to determine who the original photographer/painter was or when the image was created.

The resemblance to the portrait of “Big Buffalo” is undeniable.

However, if it is connected to the 1862-63 image of Chief Antoine Buffalo, it would support Hamilton Nelson Ross’s assertions on the Wisconsin Historical Society copy.

Clearly, multiple generations of the Buffalo family wore military jackets.

Inconclusive: uncertainty is no fun, but at this point Chequamegon History cannot determine which Chief Buffalo is in the ambrotype. However, the new evidence points more toward the grandfather (Great Buffalo) and grandson (Antoine) than it does to the son (Little Buffalo).

We will keep looking.

1842 Treaty Speeches at La Pointe in the News

May 15, 2024

Collected by Amorin Mello & edited by Leo Filipczak

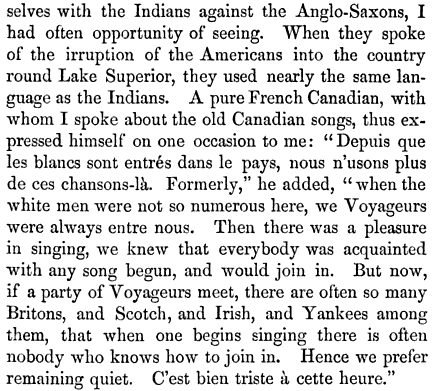

Robert Stuart was a top official in Astor’s American Fur Company in the upper Great Lakes region. Apparently, it was not a conflict of interest for him to also be U.S. Commissioner for a treaty in which the Fur Company would be a major beneficiary.

A gentleman who has recently returned from a visit to the Lake Superior Indian country, has furnished us with the particulars of a Treaty lately negotiated at La Pointe, during his sojourn at that place, by ROBERT STUART, Esq., Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the district of Michigan, on the part of the United States, and by the Chiefs and Braves of the Chippeway Indian nation on their own behalf and their people. From 3 to 4000 Indians were present, and the scene presented an imposing appearance. The object of the Government was the purchase of the Chippeway country for its valuable minerals, and to adopt a policy which is practised by Great Britain, i.e. of keeping intercourse with these powerful neighbors from year to year by paying them annuities and cultivating their friendship. It is a peculiar trait in the Indian character of being very punctual in regard to the fulfillment of any contract into which they enter, and much dissatisfaction has arisen among the different tribes toward our Government, in consequence of not complying strictly to the obligations on their part to the Indians, in the time of making the payments, for they are not generally paid until after the time stipulated in the treaty, and which has too often proven to be the means of losing their confidence and friendship.

On the 30th of September last, Mr. Stuart opened the Council, standing himself and some of his friends under an awning prepared for the occasion, and the vast assembly of the warlike Chippeways occupying seats which were arranged for their accommodation. A keg of Tobacco was rolled out and opened as a present to the Indians, and was distributed among them; when Mr. Stuart addressed them as follows:-

The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was a metaphor for infinite abundance in 1842. In less than 75 years, the species would be extinct. What that means for Stuart’s metaphor is hard to say (Biodiversity Heritage Library).

The chiefs who had been to Washington were the St. Croix chiefs Noodin (pictured below) and Bizhiki. They were brought to the capital as part of a multi-tribal delegation in 1824, which among other things, toured American military facilities.I am very glad to meet and shake hands with so many of my old friends in good health; last winter I visited your Great Father in Washington, and talked with him about you. He knows you are poor and have but little for your women and children, and that your lands are poor. He pities your condition, and has sent me here to see what can be done for you; some of your Bands get money, goods, and provisions by former Treaty, others get none because the Great Council at Washington did not think your lands worth purchasing. By the treaty you made with Gov. Cass, several years ago, you gave to your lands all the minerals; so the minerals belong no longer to you, and the white men are asking him permission to take the minerals from the land. But your Great Father wishes to pay you something for your lands and minerals before he will allow it. He knows you are needy and can be made comfortable with goods, provisions, and tobacco, some Farmers, Carpenters to aid in building your houses, and Blacksmiths to mend your guns, traps, &c., and something for schools to learn your children to read and write, and not grow up in ignorance. I hear you have been unpleased about your Farmers and Blacksmiths. If there is anything wrong I wish you would tell me, and I will write all your complaints to your Great Father, who is ever watchful over your welfare. I fear you do not esteem your teachers who come among you, and the schools which are among you, as you ought. Some of you seem to think you can learn as formerly, but do you not see that the Great Spirit is changing things all around you. Once the whole land was owned by you and other Indian Nations. Now the white men have almost the whole country, and they are as numerous as the Pigeons in the spring. You who have been in Washington know this; but the poor Indians are dying off with the use of whiskey, while others are sent off across the Mississippi to make room for the white men. Not because the Great Spirit loves the white men more than the Indians, but because the white men are wise and send their children to school and attend to instructions, so as to know more than you do. They become wise and rich while you are poor and ignorant, but if you send your children to school they may become wise like the white men; they will also learn to worship the Great Spirit like the whites, and enjoy the prosperity they enjoy. I hope, and he, that you will open your ears and hearts to receive this advice, and you will soon get great light. But said he, I am afraid of you, I see but few of you go to listen to the Missionaries, who are now preaching here every night; they are anxious that you should hear the word of the Great Spirit and learn to be happy and wise, and to have peace among yourselves.

The 1837 Treaty of St. Peters was mostly negotiated by Maajigaabaw or “La Trappe” of Leech Lake and other chiefs from outside the territory ceded by that treaty. The chiefs from the ceded lands were given relatively few opportunities to speak. This created animosity between the Lake Superior and Mississippi Bands.Your Great Father is very sorry to learn that there are divisions among his red children. You cannot be happy in this way. Your Great Father hopes you will live in peace together, and not do wrong to your white neighbors, so that no reports will be made against you, or pay demanded for damages done by you. These things when they occur displease him very much, and I myself am ashamed of such things when I hear them. Your Great Father is determined to put a stop to them, and he looks that the Chiefs and Braves will help him, so that all the wicked may be brought to justice; then you can hold up your heads, and your Great Father will be proud of you. Can I tell him that he can depend upon his Chippeway children acting in this way.

One other thing, your Great Father is grieved that you drink whiskey, for it makes you sick, poor, and miserable, and takes away your senses. He is determined to punish those men who bring whiskey among you, and of this I will talk more at another time.

Stuart would become irritated after the treaty when the Ojibwe argued they did not cede Isle Royale in 1842. This lead to further negotiations and an addendum in 1844. The Grand Portage Band, who lived closest to Isle Royale, was not party to the 1842 negotiations.When I was in New York about three moons ago I found 800 blankets which were due you last year, which by some mismanagement you did not get. Your Great Father was very angry about it, and wished me to bring them to you, and they will be given you at the payment. He is determined to see that you shall have justice done you, and to dismiss all improper agents. He despises all who would do you wrong. Now I propose to buy your lands from Fond du Lac, at the head of Lake Superior, down Lake Superior to Chocolate River near Grand Island, including all the Islands in the limits of the United States, in the Lake, making the boundary on Lake Superior about 250 miles in extent, and extending back into the country on Lake Superior about 100 miles. Mr. Stuart showed the Chiefs the boundary on the map, and said you must not suppose that your Great Father is very anxious to buy your lands, the principal object is the minerals, as the white people will not want to make homes upon them. Until the lands are wanted you will be permitted to live upon them as you now do. They may be wanted hereafter, and in this event your Great Father does not wish to leave you without a home. I propose that the Fond du Lac lands and the Sandy Lake tract (which embrace a tract 150 miles long by 100 miles deep) be left you for a home for all the bands, as only a small part of the Fond du Lac lands are to be included in the present purchase. Think well on the subject and counsel among yourselves, but allow no black birds to disturb you, your Great Father is now willing and can do you great good if you will, but if not you must take the consequences. To-morrow at the fire of the gun you can come to the Council ground and tell me whether the proposal I make in the name of your Great Father is agreeable to you; if so I will do what I can for you, you have known me to be your friend for many years. I would not do you wrong if I could, but desire to assist you if you allow me to do so. If you now refuse it will be long before you have another offer.

October 1st. At the sound of the Cannon the Council met, and when all were ready for business, Shingoop, the head Chief of the Fond du Lac band, with his 2d and 3d Chiefs, came forward and shook hands with the Commissioner and others associated with him, then spoke as follows:

Zhingob (Balsam), also known as Nindibens, signed the 1837, 1842, and 1854 treaties as chief or head chief of Fond du Lac. The Zhingob on earlier treaties is his father. See Ely, ed. Schenck, The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. ElyMy friend, we now know the purpose you came for and we don’t want to displease you. I am very glad there are so many Indians here to hear me. I wish to speak of the lands you want to buy of me. I don’t wish to displease the Traders. I don’t wish to displease the half-breeds; so I don’t wish to say at once, right off. I want to know what our Great Father will give us for them, then I will think and tell you what I think. You must not tell a lie, but tell us what our Great Father will give us for our lands. I want to ask you again, my Father. I want to see the writing, and who it is that gave our Great Father permission to take our minerals. I am well satisfied of what you said about Blacksmiths, Carpenters, Schools, Teachers, &c., as to what you said about whiskey, I cannot speak now. I do not know what the other Chiefs will say about it. I want to see the treaty and the name of the Chiefs who signed. The Chief answered that the Indians had been deceived, that they did not so understand it when they signed it.

Mr. Stuart replied that this was all talk for nothing, that the Government had a right to the minerals under former treaty, yet their Great Father wishes now to pay for the minerals and purchase their lands.

The Chief said he was satisfied. All shook hands again and the Chief retired.

The next Chief who came forward was the “Great Buffalo” Chief of the La Pointe band. Had heavy epaulettes on his shoulders and a hat trimmed with tinsel, with a heavy string of bear claws about his neck, and said:-

“Big Buffalo (Chippewa),” 1832-33 by Henry Inman, after J.O. Lewis (Smithsonian).

My father, I don’t speak for myself only, but for my Chiefs. What you said here yesterday when you called us your children, is what I speak about. I shall not say what the other Chief has said, that you have heard already.

He then made some remarks about the Missionaries who were laboring in their country and thought as yet, little had been done. About the Carpenters, he said, that he could not tell how it would work, as he had not tried it yet.

We have not decided yet about the Farmers, but we are pleased at your proposal about Blacksmiths. Can it be supposed that we can complete our deliberations in one night. We will think on the subject and decide as soon as we can.

The great Antonaugen Chief came next, observing the usual ceremony of shaking hands, and surrounded by his inferior Chiefs, said:-

The great Ontonagon Chief is almost certainly Okandikan (Buoy), depicted here in a reproduction of an 1848 pictograph carried to Washington and reproduced by Seth Eastman. Okandikan is depicted as his totem symbol, the eagle (largest, with wing extended in the center of the image).

My father and all the people listen and I call upon my Great Father in Heaven to bear witness to the rectitude of my intentions. It is now five years since we have listened to the Missionaries, yet I feel that we are but children as to our abilities. I will speak about the lands of our band, and wish to say what is just and honorable in relation to the subject. You said we are your children. We feel that we are still, most of us, in darkness, not able fully to comprehend all things on account of our ignorance. What you said about our becoming enlightened I am much pleased; you have thrown light on the subject into my mind, and I have found much delight and pleasure thereby. We now understand your proposition from our Great Father the President, and will now wait to hear what our Great Father will give us for our lands, then we will answer. This is for the Antannogens and Ance bands.

Mr. Stuart now said, that he came to treat with the whole Chippeway Nation and look upon them all as one Nation, and said

I am much pleased with those who have spoken; they are very fine orators; the only difficulty is, they do not seem to know whether they will sell their lands. If they have not made up their minds, we will put off the Council.

Lac du Flambeau Chief, “the Great Crow,” came forward with the strict Indian formalities but had but little to say, as he did not come expecting to have any part in the treaty, but wished to receive his payment and go home.

The 2d Chief of this band wished to speak. He was painted red with black spots on each cheek to set off his beauty, his forehead was painted blue, and when he came to speak, he said:-

What the last Chief has said is all I have to say. We will wait to hear what your proposals are and will answer at a proper time.

Next came forward “Noden,” or the “Great Wind,” Chief of the Mill Lac band, and said:-

Noodin (Wind) is mentioned here as representing the Mille Lacs Band, though his village was usually on Snake River of the St. Croix.

I have talked with my Great Father in Washington. It was a pity that I did not speak at the St. Peters treaty. My father, you said you had come to do justice. We do not wish to do injustice to our relations, the half-breeds, who are also our friends. I have a family and am in a hurry to get home, if my canoes get destroyed I shall have to go on foot. My father, I am hurry, I came for my payment. We have left our wives and children and they are impatient to have us return. We come a great distance and wish to do our business as soon as we can. I hope you will be as upright as our former agent. I am sorry not to see him seated with you. I fear it will not go as well as it would. I am hurry.

Mr Stuart now said that he considered them all one nation, and he wished to know whether they wished to sell their lands; until they gave this answer he could do nothing, and as it regards any thing further he could say nothing, and said they might now go away until Monday, at the firing of the Cannon they might come and tell him whether they would sell their country to their Great Father.

We intend giving the remainder of the proceedings of the treaty in our next.

Green Bay Republican:

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 1842, Page 2.

(Treaty with the Chippeways Concluded.)

Monday morning three guns were fired as a signal to open the Treaty. When all things were in readiness, Mr. Stuart said:

I am glad you have now had time for reflection, and I hope you are now ready like a band of brothers to answer the question which I have proposed. I want to see the Nation of one heart and of one mind.

Shingoop, Chief of the Fond du Lac band, came forward with full Indian ceremony, supported on each side by the inferior Chiefs. He addressed the Chippeway nation first, which was not fully interpreted; then he turned to the Commissioner and said:

in this Treaty which we are about to make, it is in my heart to say that I want our friends the traders, who have us in charge provided for. We want to provide also for our friends the half-breeds – we wish to state these preliminaries. Now we will talk of what you will give us for our country. There is a kind of justice to be done towards the traders and half-breeds. If you will do justice to us, we are ready to-morrow to sign the treaty and give up our lands. The 2d Chief of the band remarked, that he considered it the understanding that the half-breeds and traders were to be provided for.

The Great Buffalo, of La Pointe band, and his associate Chiefs came next, and the Buffalo said:

My Father, I want you to listen to what I say. You have heard what one Chief has said. I wish to say I am hurry on account of keeping so many men and women here away from their homes in this late season of the year, so I will say my answer is in the affirmative of your request; this is the mind of my Chiefs and braves and young men. I believe you are a correct man and have a heart to do justice, as you are sent here by our Great Father, the President. Father, our traders are so related to us that we cannot pass a winter without them. I want justice to be done them. I want you and our Great Father to assist us in doing them justice, likewise our half-breed children – the children of our daughters we wish provided for. It seems to me I can see your heart, and you are inclined to do so. We now come to the point for ourselves. We wish to know what you will give us for our country. Tell us, then we will advise with our friends. A part of the Antaunogens band are with me, the other part are turned Christians and gone with the Methodist band, (meaning the Ance band at Kewawanon) these are agreed in what I say.

The Bird, Chief of the Ance band, called Penasha, came forward in the usual form and said:

My Father, now listen to what I have to say. I agree with those who have spoken as far as our lands are concerned. What they say about our traders and half-breeds, I say the same. I speak for my band, they make use of my tongue to say what they would say and to express their minds. My Father, we listen to what you will offer for our country, then we will say what we have to say. We are ready to sell our country if your proposals are agreeable. All shook hands – equal dignity was maintained on each side – there was no inclination of the head or removing the hat – the Chiefs took their seats.

The White Crow next appeared to speak to the Great Father, and said:-

White Crow is apparently unaware that in the eyes of the United States, his lands, (Lac du Flambeau) were already sold five years earlier at St. Peters. Clearly, the notion of buying and selling land was not understood by him in the same way it was understood by Stuart.

Listen to what I say. I speak to the Great Father, to the Chiefs, Traders, and Half-breeds. You told us there was no deceit in what you say. You may think I am troublesome, but the way the treaty was made at St. Peters, we think was wrong. We want nothing of the kind again. We think you are a just man. You have listened to those Chiefs who live on Lake Superior. What I say is for another portion of country. It appears you are not anxious to buy the lands where I live, but you prefer the mineral country. I speak for the half-breeds, that they may be provided for: they have eaten out of the same dish with us: they are the children of our sisters and daughters. You may think there is something wrong in what I say. As to the traders, I am not the same mind with some. The old traders many years ago, charged us high and ought to pay us back, instead of bringing us in debt. I do not wish to provide for them; but of late years they have had looses and I wish those late debts to be paid. We do not consider that we sell our lands by saying we will sell them, so we consent to sell if your proposals are agreeable. We will listen and hear what they are.

Several others of the Chiefs spoke well on the subject, but the substance of all is contained in the above.

Hole-in-the-day, who is at once an orator and warrior, came forward; he had an Arkansas tooth pick in his hand which would weigh one or two pounds, and is evidently the greatest and most intelligent man in the nation, as fine a form of body, head and face, as perhaps could be found in any country.

Father, said he, I arise to speak. I have listened with pleasure to your proposal. I have come to tie the knot. I have come to finish this part of the treaty, and consent to sell our country if the offers of the President please us. Then addressing the Chiefs of the several bands he said, the knot is now tied, and so far the treaty is complete, not to be changed.

Zhaagobe (“Little” Six) signed as first chief from Snake River, and he is almost certainly the “Big Six” mentioned here. Several Ojibwe and Dakota chiefs from that region used that name (sometimes rendered in Dakota as Shakopee).

Big Six now addressed the whole Nation in a stream of eloquence which called down thunders of applause; he stands next to Hole-in-the-day in consequence and influence in the nation. His motions were graceful, his enunciation rather rapid for a fine speaker. He evidently possesses a good mind, though in person and form he is quite inferior to Hole-in-the-day. His speech was not interpreted, but was said to be in favor of selling the Chippeway country if the offer of the Government should meet their expectations, and that he took a most enlightened view of the happiness which the nation would enjoy if they would live in peace together and attend to good counsel.

Mr. Stuart now said,

I am very happy that the Chippewa nation are all of one mind. It is my great desire that they should continue to for it is the only way for them to be happy and wise. I was afraid our “White Crow” was going to fly away, but am happy to see him come back to the flock, so that you are all now like one man. Nothing can give me greater pleasure than to do all for you I can, as far as my instructions from your Great Father will allow me. I am sorry you had any cause to complain of the treaty at St. Peters. I don’t believe the Commissioner intended to do you wrong, but perhaps he did not know your wants and circumstances so as to suit. But in making this treaty we will try to reconcile all differences and make all right. I will now proceed to offer you all I can give you for your country at once. You must not expect me to alter it, I think you will be pleased with the offer. If some small things do not suit you, you can pass them over. The proposal I now make is better than the Government has given any other nation of Indians for their lands, when their situations are considered. Almost double the amount paid to the Mackinaw Indians for their good lands. I offer more than I at first intended as I find there are so many of you, and because I see you are so friendly to our Government, and on account of your kind feelings for the traders and half-breeds, and because you wish to comply with the wishes of your Great Father, and because I wish to unite you all together. At first I thought of making your annuities for only twenty years but I will make them twenty-five years. For twenty-five years I will offer you the following and some items for one year only.

$12,500 in specie each year for 25 years, $312,500

10,500 in goods ” ” ” ” ” 262,500

2,000 in provisions and tobacco, do. 50,000$625,000

This amount will be connected with the annuity paid to a part of the bands on the St. Peters treaty, and the whole amount of both treaties will be equally distributed to all the bands so as to make but one payment of the whole, so that you will be but one nation, like one happy family, and I hope there will be no bad heart to wish it otherwise. This is in a manner what you are to get for your lands, but your Great Father and the great Council at Washington are still willing to do more for you as I will now name, which you will consider as a kind of present to you, viz:

2 Blacksmiths, 25 years, $2000, $50,000

2 Farmers, ” ” 1200, 30,000

2 Carpenters, ” ” 1200, 30,000

For Schools, ” ” 2000, 50,000

For Plows, Glass, Nails, &c. for one year only, 5000

For Credits for one year only, 75,000

For Half-breeds ” ” ” 15,000$255,000

Total $880,000

With regards to the claims. I will not allow any claim previous to 1822; none which I deem unjust or improper. I will endeavor to do you justice, and if the $75,000 is not all required to pay your honest debts, the balance shall be paid to you; and if but a part of your debts are paid your Great Father requires a receipt in full, and I hope you will not get any more credits hereafter. I hope you have wisdom enough to see that this is a good offer. The white people do not want to settle on the lands now and perhaps never will, so you will enjoy your lands and annuities at the same time. My proposal is now before you.

The Fond du Lac Chief said, we will come to-morrow and give our answer.

October 4th, Mr. Stuart opened the Council.

Clement Hudon Beaulieu, was about thirty at this time and working his way up through the ranks of the American Fur Company at the beginning of what would be a long and lucrative career as an Ojibwe trader. His influence would have been very useful to Stuart as he was a close relative of Chief Gichi-Waabizheshi. He may have also been related to the Lac du Flambeau chiefs–though probably not a grandson of White Crow as some online sources suggest.

We have now met said he, under a clear sun, and I hope all darkness will be driven away. i hope there is not a half-breed whose heart is bad enough to prevent the treaty, no half-breed would prevent he treaty unless he is either bad at heart or a fool. But some people are so greedy that they are never satisfied. I am happy to see that there is one half-breed (meaning Mr. Clermont Bolio) who has heart enough to advise what is good; it is because he has a good heart, and is willing to work for his living and not sponge it out of the Indians.

We now heard the yells and war whoops of about one hundred warriors, ornamented and painted in a most fantastic manner, jumping and dancing, attended with the wild music usual in war excursions. They came on to the Council ground and arrested for a time the proceedings. These braves were opposed to the treaty, and had now come fully determined to stop the treaty and prevent the Chiefs from signing it. They were armed with spears, knives, bows and arrows, and had a feather flag flying over ten feet long. When they were brought to silence, Mr. Stuart addressed them appropriately and they soon became quiet, so that the business of the treaty proceeded. Several Chiefs spoke by way of protecting themselves from injustice, and then all set down and listened to the treaty, and Mr. Stuart said he hoped they would understand it so as to have no complaints to make afterwards.

The provisions of the treaty are the same as made in the proposals as to the amount and the manner of payment. The Indians are to live on the lands until they are wanted by the Government. They reserve a tract called the Fond du Lac and Sandy Lake country, and the lands purchased are those already named in the proposals. The payment on this treaty and that of the St. Peters treaty are to be united, and equal payments made to all the bands and families included in both treaties. This was done to unite the nation together. All will receive payments alike. The treaty was to be binding when signed by the President and the great Council at Washington. All the Chiefs signed the treaty, the name of Hole-in-the-day standing at the head of the list, and it is said to be the greatest price paid for Indian lands by the United States, their situation considered, though the minerals are said to be very valuable.

The Commissioner is said to have conducted the treaty in a very just, impartial and honorable manner, and the Indians expressed the kindest feelings towards him, and the greatest respect for all associated with him in negotiating the treaty and the best feelings towards their Agent now about leaving the country, and for the Agents of the American Fur Company and for the traders. The most of them expressed the warmest kind of feelings toward the Missionaries, who had come to their country to instruct them out of the word of the Great Spirit. The weather was very pleasant, and the scene presented was very interesting.

Le Boeuf et Le Pain: Alexis Cadotte’s letter to Chief Buffalo and Manabozho, January 11, 1840

April 30, 2024

By Leo

This was supposed to be a short post highlighting an interesting document with some light analysis of the relationship between the Ojibwe chiefs at La Pointe and the ones on the British-Canadian side of Sault Ste. Marie. It’s grown into an unwieldy musing on the challenges of doing what we do here at Chequamegon History. If you are only interested in the document, here it is:

(Copy)

Sault St. Maries 11 Janvier 1840

A Msr. le Beuf chef au tête à la pointe}

Cher grand-père,

Nous avons Recu votre par le darnier voyage des Barque de la Société. Ala nous avons apris la mort de votre fils qui nous a cose Boucup de chagrain, nous avons aussi bien compri le reste de votre, nous somme satisfait de n avoir vien neuf à la tréte de la pointe plus que vous ave vien neuf vous même nous somme de plus contents de vous pour L année prochaine arrive ici à votre endroit tachez de va espere promilles que vous nous fait que nous ayon la satisfaction an vous voyent de vous a tete cas il nous manque des Beuf ici, nous isperon que vous vous l espère Sanger il bon que vous venite a venire aucure une au Sault est Boucoup change de peu que la vie du Le Pain ne pas ici peu etre quil vous quelque chose pas cette ocation espre baucoup de vous voir l’etee prochienne, nous avons rien de particulier a vous mas que si non que faire. Baucoup a vous contée car il y a de grande nouvelles qui regarde toute votre nation et la nôtre tachez de nous faire réponse à notre lettre par le même.

2 Toute notre famille sont ans asse santé et Madame Birron qui est malade depui un mois et demi, un autre de ce petit garcon malade de pui cinq jour. Mon cher grand père nous finisson au vous Souhaitons toute sorte de Bonne prospérité croyez moi pour la vis votre tautre et efficionne fils

Signed Alexi Cadotte

Mon nomele Mainabauzo,

Je vous fais le meme Discours a vous dece que je vien de dire ici au Bouf. Il faut absolument que vous vene nous voir ici particulièrement votre patron qui moi meme et mon fils il y a un an l’été Darnier je vous espère au aspeill à la pointe nous avant neuf après ent la réponce du contenu de notre di proure si vous vere nous rejoindre nous iron ansemble à l ile Manito Wanegue au présent Anglois Car les Mitif se toi en Britanique resoive à présent comme les Sauvage vous dire à votre Jandre La pluve blanche que nous avon pas compri la lettre mon chère on ete je fini au vous enbrassan toute croyez moi pour la vie votre neveux.

signed Alexis Cadotte

Toute la famille vous fon des complément. Complement tous nous parans particulièrement

signed Cadotte

If you only want the translation, keep scrolling. If you want the story, read on.

Several years ago, I received a copy of this letter from Theresa Schenck, author and editor of several of the most important recent books on Ojibwe history. She knew that I was interested in the life of Chief Buffalo of La Pointe and described it as a charming letter written to Buffalo by one of his Cadotte relatives at Sault Ste. Marie. Dr. Schenck made a special point of telling me there were jokes inside.

My immediate reaction was what many of you might be thinking, “But I don’t speak French!” Her response was very matter-of-fact, “Well you need to know French if you’re going to study Lake Superior history. Learn French.”

During the pandemic, I finally got to it, and according to Duolingo, I now have the equivalent of three years of high-school French even though I can’t speak it at all. I can read enough to decipher Alexis Cadotte’s handwriting, though, and get the words into Google Translate. That’s where we hit a second problem.

The French that Cadotte uses in 1840 is not the same French that Duolingo and Google Translate use in 2023. Ojibwe was almost certainly the mother tongue of Alexis, who was born at Lac Courte Oreilles around 1799, but later he would have picked up French, and later still English. However, the French spoken by Cadotte and his contemporaries was commonly called patois or Metis/Michif (Alexis spells it “Mitif”), and was a mixture of French, Ojibwe, and Cree. This letter shows that Cadotte had some formal education, but even formal Quebec French deviates significantly from modern standard French. This is all to say that the letter is filled with non-standard spellings and vocabulary.

Lacking confidence in my translation, I shared the letter with Patricia McGrath, a distant relative of Alexis’ and Canadian Chequamegon History reader, and with the help of her her cousin Stéphane, we combined to produce this:

(Copy)

Sault St. Maries 11 January 1840

To Mr. Le Boeuf, Head chief at La Pointe}

Dear grandfather,

We received your communication at the last arrival of the Company Boat. It was then that we learned of the death of your son, which left us in grief. We also understood the rest of your message. You are more satisfied to have us come again to the head of “La Pointe” than for you to come here yourself. We are more than happy to see you next year, when we arrive at your place, but we hold out hope for the promise you made to give us the satisfaction of seeing you here in person. We are missing some Beef here. We hope you agree. My blood, it would be good that you should come here soon. There are many changes at the Sault. One is that Le Pain does not live here anymore. Perhaps there is something wrong with the timing. We hope to see you next summer. We have nothing new in particular to say to you. Much has been said to you because there is great news, which concerns your entire nation and ours. Try to respond to our letter in the same way.

2 Our whole family is in good health but for Madame Birron, who has been ill for a month and a half, along with one of her little boys who has been sick for five days. My dear grandfather, we end by wishing you all kinds of good prosperity. Believe me, for life, your affectionate other son

Signed Alexi Cadotte

My namesake Mainabauzo,

I am making the same speech to you as I have just said here to Le Boeuf. You absolutely have to come see us here, especially your chief, who was with me and my son a year ago last summer. I hope you will welcome us to La Pointe. Please respond to the content of our report if you wish to join us, go together to Manito Wanegue Island and receive the presents of the English, because the Mitif, if you are in British territory, now receive them as the Indians do. You tell your son-in-law White Plover that we didn’t understand his letter. My dear one, we have finished greeting you all. Believe me, for life, your nephew.

signed Alexis Cadotte

The whole family sends salutations, especially the parents.

signed Cadotte

Food puns? Long, circular statements that seem to only say “come visit your relatives.” What the heck is going on here? Another letter, written by Alexis Cadotte on the same day, sheds some light.

Sault Ste Marie, January 11 1840

Cadotte clarifies here that Le Pain is yet another food pun–this time on Le Pin, or the Pine. Zhingwaakoons (Pine) was a powerful Ojibwe chief on the British side of the Sault. The Lagardes and their in-laws, the LeSages were Metis trading families in the region.

Cadotte clarifies here that Le Pain is yet another food pun–this time on Le Pin, or the Pine. Zhingwaakoons (Pine) was a powerful Ojibwe chief on the British side of the Sault. The Lagardes and their in-laws, the LeSages were Metis trading families in the region.Eustache Legarde

My dear friend,

I write you this to wish you good health & to send my compliments to all our friends. I make known to you the result of the counsel we held yesterday with the Bread.* The answer is now received. The English Government has accepted all the applications of the Indians in favor of the half breeds, so the half breeds will begin to receive presents of the Government next summer. Furthermore the Government promises to supply the Indians with all things necessary to cultivate the soil. Besides all this the Government promises to build houses for the Half breeds, and to let them have a Forge. The Bread (Pine) is looking for a convenient place to build a half breed village. I recommend that you tell this news to all who are concerned in this matter. I am very sorry to inform you that your youngest nephew died some days ago. The rest of Sages family appear to be well. I close wishing you all kind of prosperity.

Believe me your friend

Alexis Cadotte

*Pine

From this letter, it becomes clear who “The Bread” is. It also shows that Cadotte’s motivation for writing Buffalo and Manabozho goes beyond simply missing his relatives. He wants the La Pointe chiefs to maintain their relationship with the British government and potentially relocate to Canada permanently.

By 1840, the Lake Superior Ojibwe were beginning to feel the heat of American colonization. The influx of white settlers (aside from in the lumber camps on the Chippewa and St. Croix) had yet to begin in earnest, but missionaries had settled in Ojibwe villages, and their presence was far from universally welcomed. The fur trade was in steep decline, and the monopolistic American Fur Company was well into its transition into a business model based on debts, land cessions, and annuity payments (what Witgen calls the political economy of plunder). The Treaty of St. Peters (1837) further divided Ojibwe society, creating deep resentments between the Lake Superior Bands and the Mississippi and Leech Lake Bands. Resentments also grew between the “full bloods” who were able to draw annuities from treaties, and the “mix-bloods,” who did not receive annuities but were able to use American citizenship and connections to the fur company for continued economic gain post-fur trade. Finally, the specter of removal hung over any Indian nation that had ceded its lands. The Lake Superior Ojibwe were well aware of the fates of the Meskwaki-Sauk, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Ho-Chunk and other nations to their south.

Keeping up relations with the British offered benefits beyond just the material goods described by Cadotte. It forced the American government to remain on friendly terms with the Ojibwe to prove that they were a more benevolent people than the British. In negotiations, the Ojibwe leadership often reminded the U.S. of the generosity of the “British Father.” Canadian territory also offered a potential refuge in the event of forced removal. The Jay Treaty (1796) had drawn a line through Lake Superior on European maps, but in 1840, there was still Ojibwe territory on both sides of the lake, and the people of La Pointe had many relatives on both sides of the Soo.

Zhingwaakoons was a fierce advocate of Ojibwe self-determination, and Cadotte’s letter shows that Little Pine (a.k.a. The Bread) was beginning to implement his scheme to concentrate as many Ojibwe people as possible at Garden River. If he could add the Lake Superior bands on the American side to his number, it would strengthen his position with the British-Canadian authorities. The British were open to the idea, as the Ojibwe provided a military buffer against American aggression in the event of another war between the United States and the United Kingdom. The more Ojibwe on the border in Canada, the stronger the buffer.

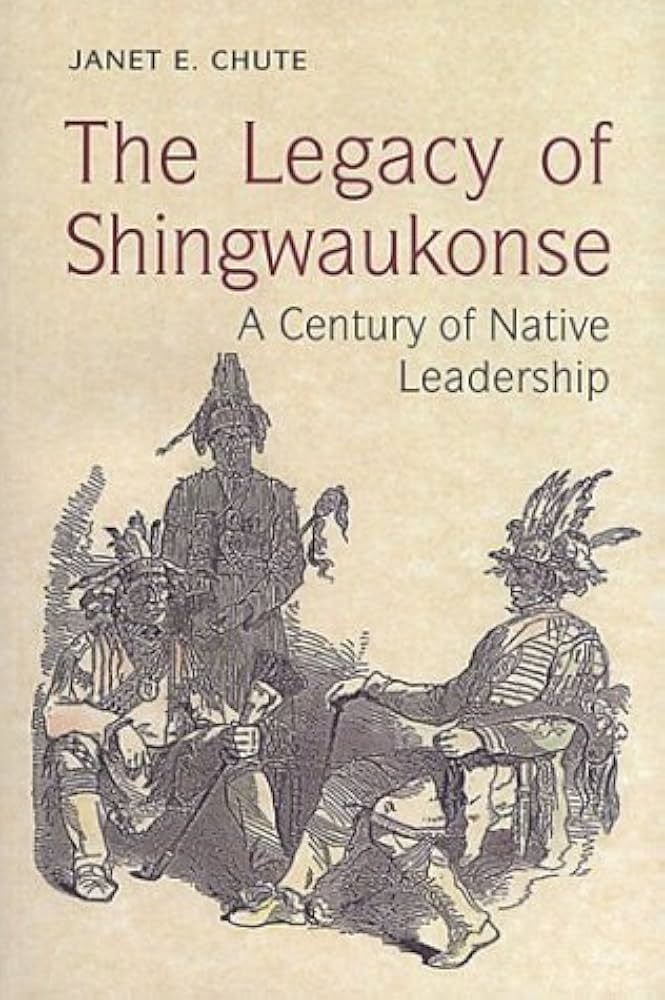

If you are interested in these topics, I strongly recommend this book:

I had already been writing Chequamegon History for a few years before I discovered The Legacy of Shingwaukonse: A Century of Native Leadership by Janet E. Chute through multiple fascinating references in Paap’s Red Cliff, Wisconsin. It was a nice wakeup call. It’s easy to get into the rut of only looking at records from the U.S. Government, the fur companies, and the missionary societies. There are other sources out there, of which the material coming from the British side of the Sault is a one example.

One of the puzzling things about the Alexis Cadotte letter is that it’s written in French. The common mother tongue of Cadotte, Buffalo, and Manabozho would have been Ojibwe. Granted, 1840 was a little early for Father Baraga’s Ojibwe writing system to have caught on, and Cadotte wouldn’t have known Sherman Hall’s system. In the following decades, letters in the Ojibwe language would become slightly more common, but at that early point, Cadotte may have still regarded Ojibwe as strictly a spoken language. It’s also possible that French offered a little more secrecy than English. Potential translators on Madeline Island would be other Metis (or Canadien heads of Metis families), whose goals would align more with Cadotte’s than with the United States Government’s. However, this is speculation.

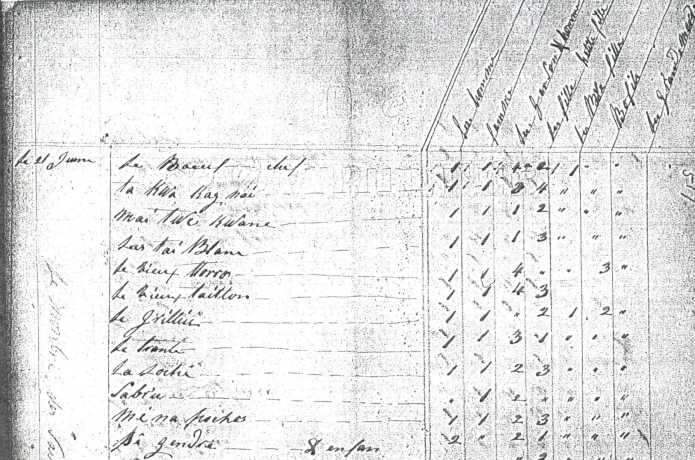

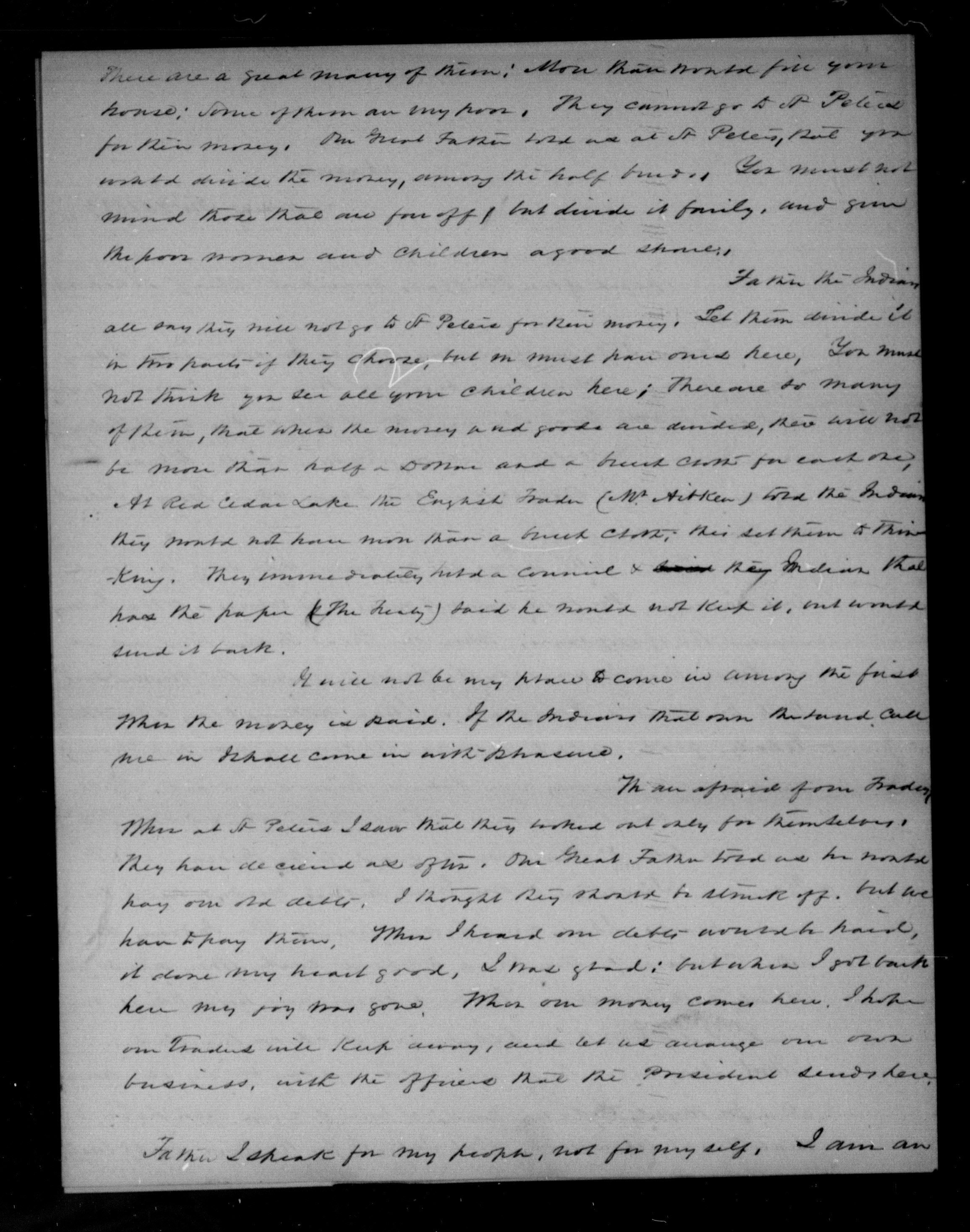

Chief Buffalo is probably referenced more than any other individual on Chequamegon History, but we haven’t had a lot to say about Manabozho. The truth is, we don’t have a lot of sources about him. From another French document, from another Cadotte, we know that he was living at La Pointe in 1831:

This 1831 census of La Pointe was taken by Big Michel Cadotte (first cousin of Alexis’ father, Little Michel Cadotte), and we see Le Boeuf listed as chief of the band. Me-na-poch-o is the eleventh household listed, and “se gendre,” an unidentified son-in-law and grandson are directly beneath him. 1 man (des hommes) 1 wife (des femmes) 2 sons (des hommes & garsons) and 3 daughters or granddaughters (des filles et petite filles) were living in Manabozho’s household.

We also see his name among the two La Pointe chiefs who signed the Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1825).

“Gitshee X Waiskee or Le Bouf of La pointe Lake superior” “Nainaboozho X of La pointe Lake Superior” Manabozho is named after the famous trickster and rabbit manitou who William Warren called “the universal uncle of the An-ish-in-aub-ag.” The initial consonant in the name of this powerful being could be an “M,” “N,” or “W” depending on grammatical context and regional dialect. Spellings in La Pointe documents from this era use all three.

And from the testimony from the 1839 payments at La Pointe, to mix-bloods and traders under the third and fourth articles of the Treaty of St. Peters (1837), we can see that Manabozho and Buffalo had a history of working with Alexis’ family. This testimony was given in favor of Alexis’ brother Louis’ claim against the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe:

Heirs of Michel Cadotte a British Subject

To amount of private property destroyed at the post occupied by Mr. Louis Corbin in the year 1809 or 1810, the claimant being then absent from said post but had left there his private property and that of his deceased father, Estimated at Eight hundred Dollars– $800.00

Louis Cadotte

His X mark

La Pointe 30th August 1838

G Franchere } witnesses

Eustache Roussain

N.B. The papers and books were all destroyed

L x C

We the undersigned Pé-jé-ké, chief of the Chippewa Tribe of Indians, residing at La Pointe and Mé-na-bou-jou, also of La pointe but formerly residing at Lac Court Oreil, do hereby certify that, to our knowledge, to the best of our recollection, about the year 1809 or 1810 the above claimant and his father had who was an Indian trader at said Lac Court Oreil, had their property destroyed by a band of Chippewa Indians, whilst said claimant was absent as well as his late father who had gone to Michilimackinac to get his usual years supply of Goods for the prosecution of his trade, which we firmly believe that the amount of Eight hundred Dollars as specified in the above account, is just and reasonable, and ought to be allowed. In witness whereof we have signed these presents the same having been read over and interpreted to us by Eustache Roussain. La Pointe this 30th day of August 1838.

Pé-jé-ké his X mark The Buffalo

Mé-na-bou-jo his X mark

This claim is for property destroyed by followers of the Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa on the Cadotte outfit post of Jean Baptiste Corbine at Lac Courte Oreille. Tenskwatawa, the brother of Tecumseh, had many followers in this region. Chequamegon History covered this incident, and Chief Buffalo’s role, back in 2013.

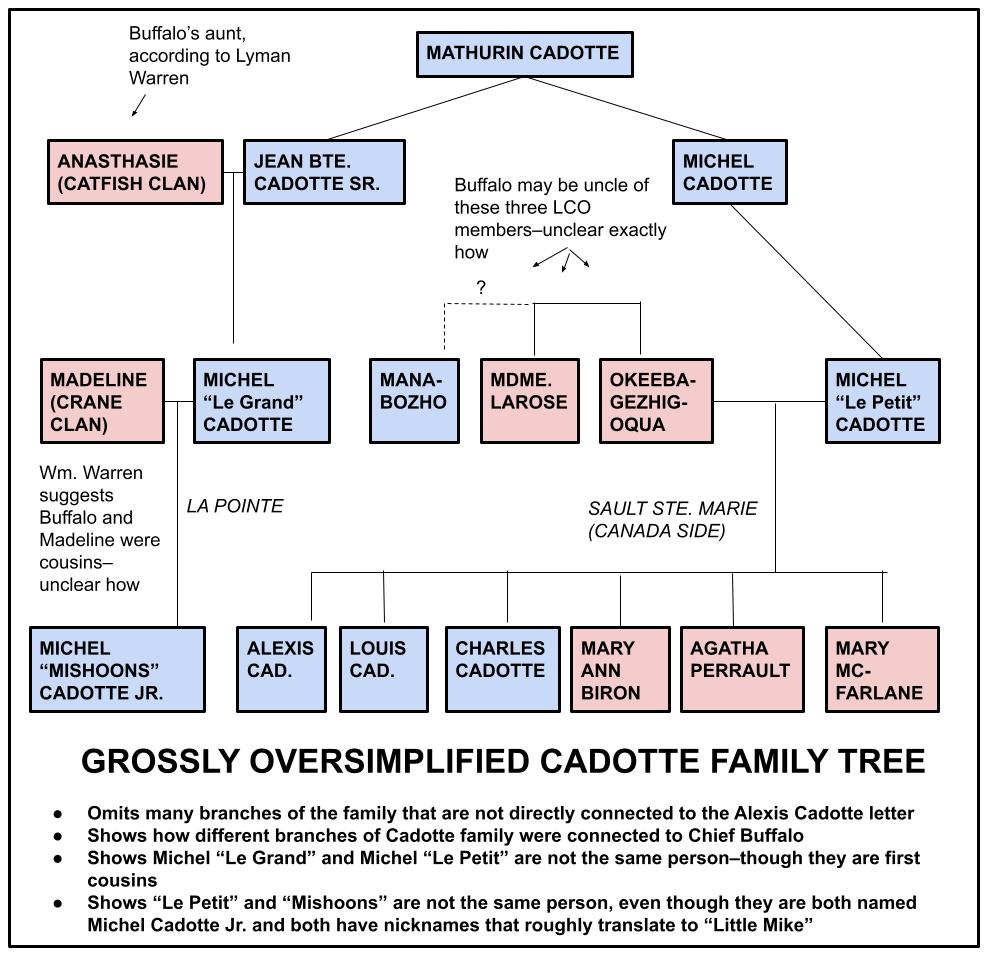

In the general mix blood claims, published in Theresa Schenck’s All Our Relations: Chippewa Mixed Bloods and the Treaty of 1837 (Amik Press; 2009), we learn more the exact relationship of Manabozho and Buffalo to the Cadottes. The former is their uncle, and the latter is their great uncle. Whether that makes the two men closely related to each other isn’t clear. The claims don’t say if they are blood relatives or in-laws of the Cadotte’s mother, Okeebagezhigoqua. However, if Manabozho was born into the band of Buffalo’s grandfather, Andegwiiyaas, and was living at Lac Courte Oreilles at the dawn of the 19th century, this would be consistent with a pattern of the “La Pointe Bands” of that era who were associated with La Pointe but living and hunting inland.

I should note that in Alexis Cadotte’s letter, he refers to Buffalo as grandpere rather than grand oncle. Don’t get too hung up on this. I am no expert on traditional Ojibwe conceptions of kinship other than to say they can be very different from European kinship systems and that it would not be at all unusual for a grandnephew to address his granduncle with the honorific title of grandfather.

From Francois, Joseph, and Charles LaRose claim

“Their Uncles are now residing at the Point, one of them is a respectable full blood Chippewa named Na-naw-bo-zho. The chief at La Pointe called Buffalo is their grand uncle. Their mother is a sister to the Cadottes. (Schenck, pg. 86)

From claims of Alexis, Louis, and Charles Cadotte, Mary Ann Biron, Agathe Perrault, and Mary McFarlane

“[Their] father was Michael Cadotte, a French trader in the ceded country, where he married a woman of the Ojibwa nation from Lake Coute Oreille named O-kee-ba-ge-zhi-go-qua.” (Schenck pg. 41)

“Five of the Earliest Indian Inhabitants of St. Mary’s Falls, 1855: 1) Louis Cadotte, John Boushe, Obogan, O’Shawan, [Louis] Gurnoe If this caption is to be trusted, andcaptions aren’t always to be trusted, there is a man named Louis Cadotte in this photo who would be about the right age to be Alexis’s brother. I read the numbers to indicate that he’s the man in the upper right. Others have interpreted this photo differently.

Sometimes different people have the same name. Very few of us can be expected to be fluent in English, Ojibwe, and regional dialects and creoles of 18th-century Quebec French (that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try!). It’s not only language. Subtle differences of religious and cultural understanding can skew the way a source is interpreted. Sources can be hard to come by, contradictory, misinterpreted by other researchers, or in unexpected places. Sometimes you stumble upon a previously unknown source that throws a monkey wrench into all your previous conclusions.

All this means that if you’re going to do this research, expect that you are going to have to humble yourself, admit mistakes, and admit when you might be pretty sure of something but not absolutely certain. My next few posts will explore these concepts further.

As always, thanks for reading,

Leo

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

P.S. Speaking of monkey wrenches…

Facts, Volumes 2-3. Facts Publishing Company. Boston, 1883. Pg. 66-68.

At Chequamegon History, we try to use reliable narrators. We try to use sources from before 1860. First-hand information is preferable to second or third-hand information, and we do not engage in much speculation or evaluation when it comes to questions of spirituality. This is especially true of traditional Ojibwe spirituality, of which we know very little.

Therefore, I strongly considered leaving out this excerpt from FACTS Prove the Truth of Science, and we do not know by any other means any Truth; we, therefore, give the so-called Facts of our Contributors to prove the Intellectual Part of Man to be Immortal. From what I can tell, this bizarre 1883 publication is dedicated to stories of “Spiritualism,” the popular late 19th-century pseudoscience (think the earliest Ouija boards, Rasputin, etc.). If you haven’t already guessed from the the length of the title, FACTS… appears to have been pretty fringe even for its own time. Take it for what it is.

Florantha (above) and Granville Sproat were more than just teachers with funny names. They wrote about 1840s La Pointe. The sex scandal that led to their departure sent a ripple through the Protestant mission community. (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Granville Sproat, however, was a real person–a schoolteacher in the Protestant mission at La Pointe. His wife, Florantha, is quoted near the top of this post, referencing the death of Chief Buffalo’s sons. The Sproats’ impact on this area’s history is pretty minimal, though they did produce a fair amount of writing in the late 1830s and early ’40s. Perhaps the most interesting part of their Chequamegon story is their abrupt departure from the Island after Granville became embroiled in what I believe is Madeline Island’s earliest recorded gay sex scandal. Since I can’t end on that cliff hanger, and it might be several years before I get to that particular story, you can learn more from Bob Mackreth’s thorough and informative treatment of Florantha’s life on youtube.

This post has really gone off the rails. Thanks for sticking with it, and as always, thanks for reading. ~LF

Special thanks to Theresa, Patricia, and Stephane for making this post possible.

When we die, we will lay our bones at La Pointe.

March 20, 2024

By Leo

From individual historical documents, it can be hard to sequence or make sense of the efforts of the United States to remove the Lake Superior Ojibwe from ceded territories of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan in the years 1850 and 1851. Most of us correctly understand that the Sandy Lake Tragedy was caused an alliance of government and trading interests. Through greed, deception, racism, and callous disregard for human life, government officials bungled the treaty payment at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi River in the fall and winter of 1850-51, leading to hundreds of deaths. We also know that in the spring of 1852, Chief Buffalo and a delegation of La Pointe Ojibwe chiefs travelled to Washington D.C. to oppose the removal. It is what happened before and between those events, in the summers of 1850 and 1851, where things get muddled.

Confusion arises because the individual documents can contradict our narrative. A particular trader, who we might want to think is one of the villains, might express an anti-removal view. A government agent, who we might wish to assign malicious intent, instead shows merely incompetence. We find a quote or letter that seems to explain the plans and sentiments leading to the disaster at Sandy Lake, but then we find the quote is dated after the deaths had already occurred.

Therefore, we are fortunate to have the following letter, written in November of 1851, which concisely summarizes the events up to that point. We are even more fortunate that the letter is written by chiefs, themselves. It is from the Office of Indian Affairs archives, but I found a copy in the Theresa Schenck papers. It is not unknown to Lake Superior scholarship, but to my knowledge it has not been reproduced in full.

The context is that Chief Buffalo, most (but not all) of the La Pointe chiefs, and some of their allies from Ontonagon, L’Anse, Upper St. Croix Lake, Chippewa River and St. Croix River, have returned to La Pointe. They have abandoned the pay ground at Fond du Lac in November 1851, and returned to La Pointe. This came after getting confirmation that the Indian Agent, John S. Watrous, has been telling a series of lies in order to force a second Sandy Lake removal–just one year removed from the tragedy. This letter attempts to get official sanction for a delegation of La Pointe chiefs to visit Washington. The official sanction never came, but the chiefs went anyway, and the rest is history.

La Pointe, Lake Superior, Nov. 6./51

To the Hon Luke Lea

Commissioner of Indian Affairs Washington D.C.

Our Father,

We send you our salutations and wish you to listen to our words. We the Chiefs and head men of the Chippeway Tribe of Indians feel ourselves aggrieved and wronged by the conduct of the U.S. Agent John S. Watrous and his advisors now among us. He has used great deception towards us, in carrying out the wishes of our Great Father, in respect to our removal. We have ever been ready to listen to the words of our Great Father whenever he has spoken to us, and to accede to his wishes. But this time, in the matter of our removal, we are in the dark. We are not satisfied that it is the President that requires us to remove. We have asked to see the order, and the name of the President affixed to it, but it has not been shewn us. We think the order comes only from the Agent and those who advise with him, and are interested in having us remove.

Kicheueshki. Chief. X his mark

Gejiguaio X “

Kishkitauʋg X “

Misai X “

Aitauigizhik X “

Kabimabi X “

Oshoge, Chief X “