Wheeler Papers: Bad River’s Missing Creek

October 3, 2018

By Amorin Mello

This is one of several posts on Chequamegon History featuring the original U.S. General Land Office surveys of the La Pointe (Bad River) Indian Reservation. An earlier post, An Old Indian Settler, features a contentious memoir from Joseph Stoddard contemplating his experiences as a young man working on the U.S. General Land Office’s crew surveying the original boundaries of the Reservation. In his memoir from 1937, Stoddard asserted the following testimony:

Bad River Headman

Joseph Stoddard

“As a Christian, I dislike to say that the field representatives of the United States were grafters and crooks, but the stories related about unfulfilled treaties, stipulations entirely ignored, and many other things that the Indians have just cause to complain about, seem to bear out my impressions in this respect.”

In the winter of 1854 a general survey was made of the Bad River Indian Reservation.

[…]

It did not take very long to run the original boundary line of the reservation. There was a crew of surveyors working on the west side, within the limits of the present city of Ashland, and we were on the east side. The point of beginning was at a creek called by the Indians Ke-che-se-be-we-she (large creek), which is located east of Grave Yard Creek. The figure of a human being was carved on a large cedar tree, which was allowed to stand as one of the corner posts of the original boundary lines of the Bad River Reservation.

After the boundary line was established, the head surveyor hastened to Washington, stating that they needed the minutes describing the boundary for insertion in the treaty of 1854.

We kept on working. We next took up the township lines, then the section lines, and lastly the quarter lines. It took several years to complete the survey. As I grew older in age and experience, I learned to read a little, and when I ready the printed treaty, I learned to my surprise and chagrin that the description given in that treaty was different from the minutes submitted as the original survey. The Indians today contend that the treaty description of the boundary is not in accord with the description of the boundary lines established by our crew, and this has always been a bone of contention between the Bad River Band and the government of the United States.

The mouth of Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek a.k.a. the townsite location of Ironton is featured in our Barber Papers and Penokee Survey Incidents. Today this location is known as the mouth of Oronto Creek at Saxon Harbor in Iron County, Wisconsin. The townsite of Ironton was formed at Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek by a group of land speculators in the years immediately following the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe. Some of these speculators include the Barber Brothers, who were U.S. Deputy Surveyors surveying the Reservation on behalf of the U.S. General Land Office. It appears that this was a conflict of interest and violation of federal trust responsibility to the La Pointe Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

This post attempts to correlate historical evidence to Stoddard’s memoir about the mouth of Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek being a boundary corner of the Bad River Indian Reservation. The following is a reproduction of a petition draft from Reverend Leondard Wheeler’s papers, who often kept copies of important documents that he was involved with. Wheeler is a reliable source of evidence as he established a mission at Odanah in the 1840s and was intimately familiar with the Treaty and how the Reservation was to be surveyed accordingly.

Wheeler drafted this petition six years after the Treaty occurred; this petition was drafted more than seventy-five years earlier than when Stoddard’s memoir of the same important matter was recorded. The length of time between Wheeler’s petition draft and Stoddard’s memoir demonstrates how long this was (and continued to be) a matter of great contemplation and consternation for the Tribe. Without further ado, we present Wheeler’s draft petition below:

A petition draft selected from the

Wheeler Family Papers:

Folder 16 of Box 3; Treaty of 1854, 1854-1861.

To Hon. C W Thompson

Genl Supt of Indian affair, St Paul, Min-

and Hon L E Webb,

Indian Agent for the Chippewas of Lake Superior

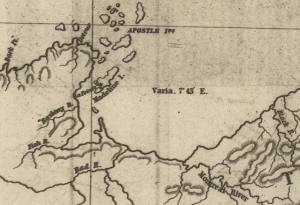

March 30th, 1855 map from the U.S. General Land Office of lands to be withheld from sale for the La Pointe (Bad River) Reservation from the National Archives Microfilm Publications; Microcopy No. 27; Roll 16; Volume 16. The northeast corner of the Reservation along Lake Superior is accurately located at the mouth of Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek (not labeled) on this map.

The undersigned persons connected with the Odanah Mission, upon the Bad River Reservation, and also a portion of those Chiefs who were present and signed the Treaty of Sept 30th, AD 1854, would most respectfully call your attention to a few Statements affecting the interests of the Indians within the limits of the Lake Superior Agency, with a view to soliciting from you such action as will speedily see one to the several Indian Bands named, all of the benefits guaranteed to them by treaty stipulation.

Under the Treaty concluded at La Pointe Sept 30th, 1854 the United States set apart a tract of Land as a Reservation “for the La Pointe Band and such other Indians as may see fit to settle with them” bounded as follows.

a.k.a.

Ke-che-se-be-we-she

“Ke-che” (Gichi) refers to big, or large.

“se-be” (ziibi) refers to a river.

“we-she” (wishe) refers to rivulets.

Source: Gidakiiminaan Atlas by the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission

“Beginning on the South shore of Lake Superior a few miles west of Montreal River at the mouth of a creek called by the Indians Ke-she-se-be-we-she, running thence South &c.”

Detail of the Bad River Reservation from GLIFWC’s Gidakiiminaan Atlas. This map clearly shows that the northeast boundary of Bad River Reservation is not located at the true location of Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek in accordance with the 1854 Treaty. Red highlights added for emphasis of discrepancies.

Your petioners would represent that at the time of the wording of this particular portion of the Treaty, the commissioner on the part of the United States inquired the number of miles between the mouth of the Montreal River and the mouth of the creek referred to, in reply to which, the Indians said “they had no knowledge of distance by miles” and therefore the commissioner assumed the language of “a few miles west of Montreal River” as discriptive of the creek in mind. This however, upon actual examination of the ground, does to the Band the greatest injustice, as the mouth of the creek to which the Indians referred at the time is even less than one mile west of the mouth of the Montreal.*

*This creek at the time was refered to as having “Deep water inside the Bar” sufficient for Boats which is definitive of the creek still claimed as the starting point, and is not descriptive of the most westerly creek.

But White men, whose interests are adverse to those of the Indians now demand that the Reservation boundary commence at an insignificant and at times scarcely visible creek some considerable distance west of the one referred to in the Treaty, which would lessen the aggregate of the Reservation from 3 to 4000 acres.

Your petioners, have for years, desired and solicited a settlement of the matter, both for the good of the Indians and of the Whites, but from lack of interest the administrations in power have paid no attention to our appeals, as is also true of other matters to which we now call your attention.

1861 resurvey of Township 47 North of Range 1 West by Elisha S. Norris for the General Land Office relocating Bad River Reservation’s northeast boundary. Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek was relocated to what is now Graveyard Creek instead of its true location at the Barber Brother’s Ironton townsite location. Red highlights added for emphasis of discrepancies.

As many heads of families now wish to select (within the portion of Town 47 North of Range 1 West belonging to the Reservation the 80 acre tract assigned to them) we desire that the Eastern Boundary of the Reservation be immediately established so that the subdivisions may be made and and land selected.

Your petioners would further [represent?] that under the 3d Section of the 2nd article of the Treaty referred to the Lac De Flabeau, and Lac Court Orelles Bands are entitled to Reservations each equal to 3 Townships, (See article 3d of Treaty. These Reservations have never been run out, none have any subdivisions been made.) which also were to be subdivided into 80 acre Tracts.

Article 4th promises to furnish each of the Reservations with a Blacksmith and assistant with the usual amount of Stock, where as the Lac De Flambeau Band have never yet had a Blacksmith, though they have repeatedly asked for one.

Wisconsin State Representative

and co-founder of Ashland

Asaph Whittlesey

As the matters have referred to one of vital importance to these several Bands of Indians, we earnestly hope that you will give your influence towards securing to them, all of the benefits named in the Treaty and as the subject named will demand labor entirely outside of the ordinary duties of an Indian Agent, and as it will be important for some one to visit the Reservations Inland, so as to be able to report intelligently upon the actual State of Things, we respectfully suggest that Mr Asaph Whittlesey be specially commissioned (provided you approve of the plan and you regard him as a suitable person to act) to attend to the taking of the necessary depositions and to present these claims, with the necessary maps and Statistics, before the Commissioner of Indian Affairs at Washington, the expense of which must of necessity, be met by the Indian Department.

Mr Whittlesey was present at the making of the Treaty to which we refer, and is well acquainted with the wants of the Indians and with what they of right can claim, and in him we have full confidence.

In addition to the points herein named should you favor this commission, we would ask him to attend to other matters affecting the Indians, upon which we will be glad to confer with you at a proper time.

The undersigned L H Wheeler and Henry Blatchford have no hesitency in saying that the representations here made are full in accordance with their understanding of the Treaty, at the time it was drawn up, they being then present and the latter being one of the Interpreters at the time employed by the General Government.

Most Respectfully Yours

Dated Odanah Wis July 1861

Names of those connected with the Odanah Mission

[None identified on this draft petition]

Names of Chiefs who were signers to the Treaty of Sept 30th 1854

[None identified on this draft petition]

Although this draft was not signed by Wheeler or Blatchford, or by the tribal leadership that they appear to be assisting, Chequamegon History believes it is possible that a signed original copy of this petition may still be found somewhere in national archives if it still exists.

Among The Otchipwees: I

May 28, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 2 December 1884

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 86-91.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

Like all the northern tribes, the Chippewas are known by a variety of names. The early French called them Sauteus, meaning people of the Sault. Later missionaries and historians speak of them as Ojibways, or Odjibwes. By a corruption of this comes the Chippewa of the English.

“No-tin” copied from 1824 Charles Bird King original by Henry Inman in 1832-33. Noodin (Wind) was a prominent Chippewa chief from the St. Croix country.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

On the south of the Chippewas, in 1832, across the Straits of Mackinaw, were the Ottawas. Some of this nation were found by Champlain on the Ottawa River of Canada, whom he called Ottawawas. In later years there were some of them on Lake Superior, of whom it is probable the Lake Court Oreille band, in northwestern Wisconsin, is a remainder. The French call them “Court Oreillés,”, or short ears. All combined, it is not a powerful nation. Many of them pluck the hair from a large part of the scalp, leaving only a scalp lock. This custom they explain as a concession to their enemies, in order to make a more neat and rapid job of the scalping process. A thick head of coarse hair, they say, is a great impediment. Probably the true reason is a notion of theirs that a scalp lock is ornamental. The practice is not universal among Ottawas, and is not common with the neighboring tribes. These were the people who committed the massacre of the English garrison at Old Mackinaw, in 1763.

![Mah-kée-mee-teuv, Grizzly Bear, Chief of the [Menominee] Tribe by George Catlin, 1831. ~ Smithsonian Institute](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/1831-mah-kee-mee-teuv-grizzly-bear-by-george-catlin.jpg?w=230&h=300)

“Mah-kée-mee-teuv, Grizzly Bear, Chief of the [Menominee] Tribe” by George Catlin, 1831.

~ Smithsonian Institute

The Oneidas, a small remnant of that nation, from New York, were located on Duck River, near Fort Howard, and the Tuscaroras on the south shore of Lake Winnebago.

Detail from “Among The Winnebago [Ho-Chunk] Indians. Wah-con-ja-z-gah (Yellow Thunder) Warrior chief 120 y’s old” stereograph by Henry Hamilton Bennett, circa 1870s.

~ J. Paul Getty Museum

Plaster life cast of Sac leader Black Hawk (Makatai Meshe Kiakiak) reproduced by Bill Whittaker (original was made circa 1830) on display at Black Hawk State Historic Site.

~ Wikipedia.org

Next to the Menominees on the west were the Winnebagoes, a barbarous, warlike and treacherous people, even for Indians. Their northern border joined the Chippewas. Yellow Thunder’s village, in 1832, was on the trail from Lake Winnebago to Fort Winnebago, south of the Fox River about half way. He was more of a prophet, medicine man or priest, than warrior. In the Black Hawk war man of the Winnebago bucks joined the Sacs and the Foxes. Only four years before the United States was obliged to send an expedition against them, and to build a stockade at the portage. Their chiefs, old men, and medicine men, professed to be very friendly to us, but kept up constant communications with Black Hawk. When he was beaten at the Bad Ax River, and his warriors dispersed, they followed the old chief into the northern forest, captured him, and delivered him to the United States forces.

One of the causes of the Black Hawk War in 1832 was the murder of a party of Menominees near Fort Crawford, by the Sacs and Foxes. There was an ancient feud between those tribes which implies a series of scalping parties from generation to generation.

Sac leader “Ke-o-kuk or the Watchful Fox” by Thomas M. Easterly, 1847.

~ Missouri History Museum

As the Menominees were at peace with the United States, and their camps were near the garrison, they were considered to have been under Federal protection, and their murder as an insult to its authority. The return of Keokuk’s band to the Rock River country brought on a crisis in the month of May. The Menominees were anxious to avenge themselves, but were quieted by the promise of the government that the Sacs and Foxes should be punished. They offered to accompany our troops as scouts or spies, which was not accepted until the month of July, when Black Hawk had returned to the Four Lakes, where is now the city of Madison.

On a bright afternoon, about the middle of the month, a company of Menominee warriors emerged in single file from the woods in rear of Fort Howard at the head of Green Bay. They numbered about seventy-five, each one with a gun in his right hand, a blanket over his right shoulder, held across the breast by the naked left arm, and a tomahawk. Around the waist was a belt, on which was a pouch and a sheath, with a scalping knife. Their step was high and elastic, according to the custom of the men of the woods. On their faces was an excess of black paint, made more hideous by streaks of red. Their coarse black hair was decorated with all the ribbons and feathers at their command. Some wore moccasins and leggings of deer skin, but a majority were barefooted and barelegged. They passed across the common to the ferry, where they were crossed to Navarino, and marched to the Indian Agency at Shantytown. Here they made booths of the branches of trees. Captain or Colonel Hamilton, a son of Alexander Hamilton, was their commander. As they had an abundance to eat and were filled with martial prowess, they were exceedingly jubilant.

“A view of the Butte des Morts treaty ground with the arrival of the commissioners Gov. Lewis Cass and Col. McKenney in 1827” by James Otto Lewis, 1835.

~ Library of Congress

Their march was up the valley of the river, recrossing above Des Peres, passing the great Kakolin, and the Big Butte des Morts to the present site of Oshkosh. Thence crossing again they followed the trail to the Winnebago villages, past the Apukwa or Rice lakes to Fort Winnebago, making about twenty miles a day. On the route they were inclined to straggle, presenting nothing of military aspect except a uniform of dirty blankets. Colonel Hamilton was not able to make them stand guard, or to send out regular pickets. They were expert scouts in the day time, but at night lay down to sleep in security, trusting to their dogs, their keen sense of hearing and the great spirit. On the approach of day they were on the alert. It is a rule in Indian tactics to operate by surprises, and to attack at the first show of light in the morning.

From Fort Winnebago they moved to the Four Lakes, where Madison now is. Black Hawk had retired across the Wisconsin River, where there was a skirmish on the 21st of July, and the battle of the Bad Ax was being fought.

Photograph of Pierre Jean Édouard Desor (Swiss geologist and professor at Neuchâtel academy) from Wisconsin Historical Society. Desor and others were employed to survey for Report on the geology and topography of a portion of the Lake Superior Land District in the state of Michigan: Part I, Copper Lands; Part II, The Iron Region.

A few miles southwesterly of Waukedah, on the branch railroad to the iron mines of the upper Menominee, is a lake called by the Indians “Shope,” or Shoulder Lake, which I visited in the fall of 1850, in company with the late Edward Desor, a scientist of reputation in Switzerland. It discharges into the Sturgeon River, one of the eastern branches of the Menominee. There was a collection of half a dozen lodges, or wigwams, covered with bark, with a small field of corn, and the usual filth of an Indian village. The patriarch, or “chief” of that clan, came out to meet us, attended by about thirty men, women and children. By the traders he was called “Governor.” His nose was prominently Roman. He stood evenly on both feet, with his limbs bare below the knees. The right arm was also bare, and over the left shoulder was thrown a dirty blanket, covering the chest and the hips. A mass of coarse black hair covered the head, but was pushed away from the face. The usual dark, steady, snakelike, black eye of the race examined us with a piercing gaze. His face, with its large, well proportioned features, was almost grand. his pose was easy, unstudied and dignified, like one’s ideal of the Roman patrician of the time of Cicero, such as sculptors would select as a model.

This band were the Chippewas, but the coast of Green Bay was occupied by Menominees or Menomins, known to the French as “Folle Avoines,” or “Wild Rice” Indians, for which Menomin is the native name. Above the Twin Falls of the Menominee was an ancient village of Chippewas, called the “Bad Water” band, which is their name for a series of charming lakes not far distant, on the west of the river. They said their squaws, a long time since, were on the lakes in a bark canoe. Those on the land saw the canoe stand up on end, and disappear beneath the surface with all who were in it. “Very bad water.” From that time they were called the “Bad Water” lakes.

The Bad Water Band of Lake Superior Chippewa was first documented by Captain Thomas Jefferson Cram in his 1840 report to Congress.

~ Dickinson County Library

Cavalier was a half-breed French and Menominee. He was a handsome young man, and was well aware of it. Though he was married, the squaws received his attentions without much reserve. Half-breeds dress like the whites of the trading post, and not as Indians. Their hair is cut, and instead of a blanket they have coarse overcoats, and wear hats. Many of them are traders, a class mid-way between the whites and Indians.

No Princess Zone: Hanging Cloud, the Ogichidaakwe is a popular feature here on Chequamegon History.

Polygamy is the most fixed of savage institutions, and one that the half-breed and trader does not despise. Chippewa maidens, and even wives, have many reasons for looking kindly upon men who wear citizens’ clothes and trade in finery. Moccasins they can make very beautifully, but shawls and strouds of broadcloth, silk ribbons, pewter broaches, brass rings, and glass beads they cannot. These are the work of the white man. But none of that race, man or maid, has a more powerful passion for the ornamental than the children of the forest, male or female. Let us not judge the latter too harshly – poor, ignorant, suffering slave, with none of the protection which the African slave could sometimes invoke against barbarian cruelty. Their children are as happy and playful as those of the white race. Before they become men and women they are frequently beautiful, the deep brunette of their complexion having, on the cheek, a faint tinge of a lighter color, especially among those from the far north, like the “Bois Forts” of Rainy Lake. Young lads and girls have well formed limbs and straight figures, with agile and graceful movements. At this age the burdens and hardships of the squaws have not deformed them. The smoke of the lodge has not tanned their skin to Arab-like blackness nor inflamed their eyes. In about ten years of drudgery, rowing the canoe, putting up lodges, bearing children, and not infrequent beatings by her lord, the squaw is an old woman. Her features become rough and angular, the melodious voice of childhood is changed to one that is sharp, shrill, piercing and disagreeable. At forty she is a decrepit old woman, and before that time, if her master has not put her away, he may have installed number two as an additional tyrant.

A Menominee village in “Village of Folle-Avoines” by Francis de Laporte de Castelnau, 1842.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Well up the Peshtigo, on a rainy, foggy afternoon, we made an early camp near a dismal swamp on the low ground. On the other side of the river, at a considerable distance, was heard the moans of a person evidently in great distress. Cavalier was sent over to investigate. He found a wigwam with a Menominee and two women, both wives. The youngest was on a bridal tour. The old wife had broken her thigh about a month before, which had not been set. She was suffering intensely, the limb very much swollen, and the bridal party wholly neglecting her. It was evident that death was her only relief. A strong dose of morphine gradually moderated her groans, which were more pathetic than anything that ever reached my ears. Before morning she was quiet.

As the water was very low I went through the gorge of the Menominee above the Great Bekuennesec, or Smoky Falls. Near the lower end, and in hearing of the cataract, I saw through the rocky chasm a mountain in the distance to the northeast. My half-breed said the Indians called it Thunder Mountain. They say that thunder is caused by an immense bird which goes there, when it is enveloped by clouds and flaps its wings furiously.

Turning away from the mists of the cataract and its never ceasing roar, we went southwesterly among the pines, over rocks and through swamps, to a time worm trail leading from the Bad Water village to the Pemenee Falls. This had been for many years the land route from Kewenaw Bay to the waters of Green Bay at the mouth of the Menominee River. When the copper mines on Point Kewenaw were opened, in 1844 and 1845, the winter mail was carried over this route on dog trains, or on the backs of men. Deer were very plenty in the Menominee valley. Bands of Pottawatomies scoured the woods, killing them by hundreds for their skins. We did not kill them until near the close of the day, when about to encamp. Cavalier went forward along the trail to make camp and shoot a deer. I heard the report of his gun, and expected the usual feast of fresh venison. “Where is your deer?” “Don’t know; some one has put a spell on my gun, and I believe I know who did it.”

Map of Lac Vieux Desert with “Catakitekon” [Gete-gitigaan (old gardens)] from Thomas Jefferson Cram’s 1840 fieldbook.

~ School District of Marshfield: Digital Time Travelers

The Chippewas are spread over the shores and the rivers of Lake Superior, Lake Nipigon, the heads of the Mississippi, the waters of Red Lake, Rainy Lake and the tributaries of the Lake of the Woods. When Du Lhut and Hennepin first became acquainted with the tribes in that region, the Sioux, Dacotas, or Nadowessioux, and the Chippewas were at war, as they have been ever since. The Sioux of the woods were located on the Rum, or Spirit River, and their warriors had defeated the Chippewas at the west end of Lake Superior. Hennepin was a prisoner with a band of Sioux on Mille Lac, in 1680, at the head of Rum River, called Isatis. When Johnathan Carver was on the upper Mississippi, in 1769, the Chippewas had nearly cleared the country between there and Lake Superior of their enemies. In 1848 their war parties were still making raids on the Sioux and the Sioux upon them.

CHARLES WHITTLESEY.

To be continued in Among The Otchipwees: II…

Wisconsin Territory Delegation: The Copper Region

April 17, 2016

By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from Copper Harbor.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 21, 1845.

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE.

—

[From our Regular Correspondent.]

THE COPPER REGION.

La Pointe, Lake Superior

July 28, 1845.

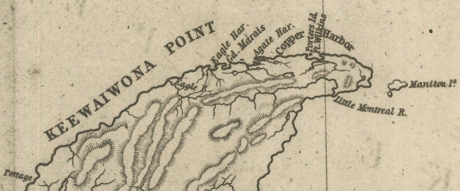

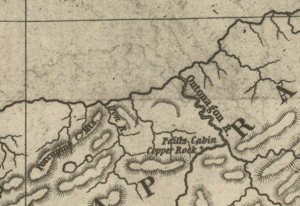

Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

In my last brief letter from this place, I had not time to notice many things which I desired to describe. I have now examined the whole coast of the southern shore of Lake Superior, extending from the Sault Ste. Marie to La Pointe, including a visit to the Anse, and the doubling of Keweena point. During the trip, as stated previously, we had camped out twenty-one nights. I examined the mines worked by the Pittsburg company at Copper harbor, and those worked by the Boston company at Eagle river, as well as picked up all the information I could about other portions of the mineral district, both off and on shore. The object I had in view when visiting it, was to find out, as near as I could, the naked facts in relation to it. The distance of the lake-shore traversed by my part to La Pointe was about five hundred miles – consuming near four weeks’ time to traverse it. I have still before me a journey of three or four hundred miles before I reach the Mississippi river, by the way of the Brulé and St. Croix rivers. I know the public mind has been recently much excited in relation to the mineral region of country of Lake Superior, and that a great many stories are in circulation about it. I know, also, that what is said and published about it, will be read with more or less interest, especially by parties who have embarked in any of the speculations which have been got up about it. It is due to truth and candor, however, for me to declare it as my opinion, that the whole country has been overrated. That copper is found scattered over the country equal in extent to the trap-rock hills and conglomerate ledges, either in its native state, or in the form of a black oxide, as a green silicate, and, perhaps, in some other forms, cannot be denied;- but the difficulty, so far, seems to be that the copper ores are too much diffused, and that no veins such as geologist would term permanent have yet positively been discovered.

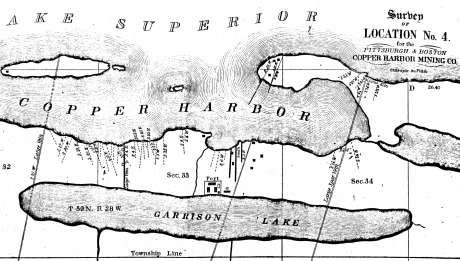

Detail of a Survey of Location No. 4 for the Pittsburgh & Boston Copper Harbor Mining Co. Image digitized by the Detroit Public Library Burton Historical Collection for The Cliff Mine Archeology Project Blog.

The richest copper ore yet found is that raised from a vein of black oxide, at Copper harbor, worked by the Pittsburg company, which yields about seventy per cent. of pure copper. But this conglomerate cementation of trap-rock, flint, pebbles, &c., and sand, brought together in a fused black mass, (as is supposed, by the overflowings of the trap, of which the hills are composed near this place,) is exceedingly hard and difficult to blast. An opinion seems to prevail among many respectable geologist, that metallic veins found in conglomerate are never thought to be very permanent. Doctor Pettit, however, informed me that he had traced the vein for near a mile through the conglomerate, and into the hill of trap, across a small lake in the rear of Fort Wilkins. The direction of the vein is from northwest to southeast through the conglomerate, while the course of the lake-shore and hills at this place varies little from north and south. Should the doctor succeed in opening a permanent vein in the hill of trap opposite, of which he is sanguine, it is probable this mine will turn out to be exceedingly valuable. As to these matters, however, time alone, with further explorations, must determine. The doctor assured me that he was at present paying his way, in merely sinking shafts over the vein preparatory to mining operations; which he considered a circumstance favorable to the mine, as this is not of common occurrence.

The mines at Copper harbor and Eagle river are the only two as yet sufficiently broached to enable one to form any tolerably accurate opinion as to their value or prospects.

~ Encyclopedia of the Earth

Other companies are about commencing operations, or talk of doing so – such as a New York, or rather Albany company, calling themselves “The New York and Lake Superior Mining Company,” under the direction of Mr. Larned, of Albany, in whose service Dr. Euhts has been employed as geologist. They have made locations at various points – at Dead river, Agate harbor, and at Montreal river. I believe they have commenced mining to some extent at Agate harbor.

One or two other Boston companies, besides that operating at Eagle river, have been formed with the design of operating at other points. Mr. Bernard, formerly of St. Louis, is at the head of one of them. Besides these, there is a kind of Detroit company, organized, it is said, for operating on the Ontonagon river. It has its head, I believe, in Detroit, and its tail almost everywhere. I have not heard of their success in digging, thus far; though they say they have found some valuable mines. Time must determine that. I wish it may be so.

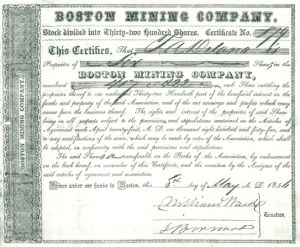

Boston Mining Company stock issued by Joab Bernard in 1846.

~ Copper Country Reflections

From Copper harbor, I paid a visit to Eagle river – a small stream inaccessible to any craft larger than a moderate-sized Mackinac boat. There is only the open lake for a roadstead off its mouth, and no harbor nearer than Eagle harbor, some few miles to the east of it. In passing west from Copper harbor along the northern shore of Keweena point, the coast, almost from the extremity of Keweena point, to near Eagle river, is an iron-bound coast, presenting huge, longitudinal, black, irregular-shaped masses of trap-conglomerate, often rising up ten or fifteen feet high above water, at some distance from the main shore, leaving small sounds behind them, with bays, to which there are entrances through broken continuities of the advanced breakwater-like ledges. Copper harbor is thus formed by Porter’s island, on which the agency has been so injudiciously placed, and which is nothing but a conglomerate island of this character; with its sides next the lake raised by Nature, so as to afford a barrier against the waves that beat against it from without. The surface of the island over the conglomerate is made up of a mass of pebbles and fragmentary rock, mixed with a small portion of earth, wholly or quite incapable of cultivation. Fort Wilkins is located about two miles from the agency, on the main land, between which and the fort communication in winter is difficult, if not impossible. Of the inexcusable blunder made in putting this garrison on its present badly-selected site, I shall have occasion to speak hereafter.

“Grand Sable Dunes”

~ National Park Service

In travelling up the coast from Sault Ste. Marie, the first 50 or 100 miles, the shore of Lake Superior exhibits, for much of the distance, a white sandy beach, with a growth of pines, silver fir, birch, &c., in the rear. This beach is strewed in places with much whitened and abraded drift-wood, thrown high on the banks by heavy waves in storms, and the action of ice in winter. This drift-wood is met with, at places, from one end of the lake to the other, which we found very convenient for firewood at our encampments. The sand on the southern shore terminates, in a measure, at Grand Sables, which are immense naked pure sand-hills, rising in an almost perpendicular form next to the lake, of from 200 to 300 feet high. Passing this section, we come to white sand-stone in the Pictured Rocks. Leaving these, we make the red sand-stone promontories and shore, at various points from this section, to the extreme end of the lake. It never afterwards wholly disappears. Between promontories of red stone are headlands, &c., standing out often in long, high irregular cliffs, with traverses of from 6, 7, to 8 miles from one to the other, while a kind of rounded bay stretches away inland, having often a sandy beach at its base, with pines growing in the forest in the rear. Into these bays, small rivers, nearly or quite shut in summer with sand, enter the lake.

The first trap-rock we met with, was near Dead river, and at some few points west of it. We then saw no more of it immediately on the coast, till we made the southern shore of Keweena point. All around the coast by the Anse, around Keweena bay, we found nothing but alternations of sand beaches and sand-stone cliffs and points. The inland, distant, and high hills about Huron river, no doubt, are mainly composed of trap-rock.

Detail from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Going west from Eagle river, we soon after lost both conglomerate and trap-rock, and found, in their stead, our old companions – red sand-stone shores, cliffs, and promontories, alternating with sandy or gravelly beaches.

Detail of the Ontonagon River, “Paul’s Cabin,” the Ontonagon Boulder, and the Porcupine Mountains from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The trap-rock east and west of the Portage river rises with, and follows, the range of high hills running, at most points irregularly, from northeast to southwest, parallel with the lake shore. It is said to appear in the Porcupine mountain, which runs parallel with Iron river, and at right angles to the lake shore. This mountain is so named by the Indians, who conceived its principal ridge bore a likeness to a porcupine; but, to my fancy, it bears a better resemblance to a huge hog, with its snout stuck down at the lake-shore, and its back and tail running into the interior. This river and mountain are found about twenty miles west of the Ontonagon river, which is said to be the largest stream that empties into the lake. The site for a farm, or the location of an agency, at its mouth, is very beautiful, and admirably suited for either purpose. The soil is good; the river safe for the entrance and secure anchorage of schooners, and navigable to large barges and keel-boats for twelve miles above its mouth. The trap range, believed to be as rich in copper ores as any part of Lake Superior, crosses this river near its forks, about fifteen miles above its mouth. The government have organized a mineral agency at its mouth, and appointed Major Campbell as agent to reside at it; than whom, a better selection could not have been made.

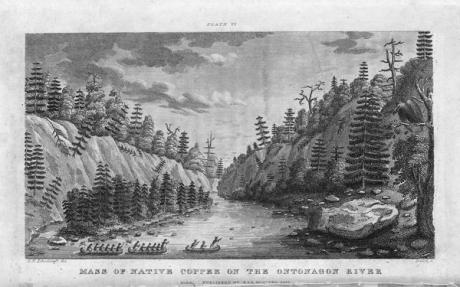

“Engraving depicting the Schoolcraft expedition crossing the Ontonagon River to investigate a copper boulder.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Detail of the Montreal River, La Pointe, and Chequamegon bay from from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The nearest approach the trap-rock hills make to the lake-shore, beyond the Porcupine mountain, is on the Montreal river, a short distance above the falls. Beyond Montreal river, to La Pointe, we found red-clay cliffs, based on red sand-stone, to occur. Indeed, this combination frequently occurred at various sections of the coast – beginning, first, some miles west of the Portage.

From Copper harbor to Agate harbor is called 7 miles; to Eagle river, 20 miles; to the Portage, 40 miles; to the Ontonagon, 80 miles; to La Pointe, from Copper harbor, 170 miles. From the latter place to the river Brulé is about 70 miles; up which we expect to ascend for 75 miles, make a portage of three miles to the St. Croix river, and descend that for 300 miles to the Mississippi river.

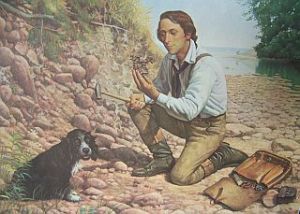

Painting of Professor Douglass Houghton by Robert Thom. Houghton first explored the south shore of Lake Superior in 1840, and died on Lake Superior during a storm on October 13, 1845. Chequamegon Bay’s City of Houghton was named in his honor, and is now known as Houghton Falls State Natural Area.

Going back to Eagle river, at the time of our visit, we found at the mine Mr. Henshaw, Mr. Williams, and Dr. Jackson of Boston, and Dr. Houghton of Michigan, who was passing from Copper harbor to meet his men at his principal camp on Portage river, which he expected to reach that night. The doctor is making a rapid and thorough survey of the country. This work he is conducting in a duplicate manner, under the authority of the United States government. It is both a topographical and geological survey. All his surveyors carry sacks, into which they put pieces of rock broken from every prominent mass they see, and carry into camp at night, for the doctor’s examination, from which he selects specimens for future use. The doctor, from possessing extraordinary strength of constitution, can undergo exposure and fatigue sufficient to break down some of the hardiest men that can be found in the West. He wears his beard as long as a Dunkard’s; has a coat and patched pants made of bed ticking; wears a flat-browned ash-colored, wool hat, and a piece of small hemp cord off a guard chain; and, with two half-breed Indians and a small dog as companions, embarks in a small bark, moving and travelling along the lake shore with great celerity.

Probably no company on Lake Superior has had a longer and harder struggle against adversity than the Phœnix. The original concern, the Lake Superior Copper Company, was among the first which operated at Lake Superior after the relinquishment of the Indian rights to this country in 1843. The trustees of this early organization were David Henshaw and Samuel Williams of Boston, and D. G. Jones and Col. Chas. H. Gratiot, of Detroit; Dr. Charles T. Jackson examined the veins on the property, and work was begun in the latter part of the year 1844. The company met with bad luck from the start, and, the capital stock having become exhausted, it has been reorganized several times in the course of its history.”

~ The Lake Superior Copper Properties: A Guide to Investors and Speculators in in Lake Superior Copper Shares Giving History, Products, Dividend Record and Future Outlook for Each Property, by Henry M. Pinkham, 1888, page 9.

We all sat down to dinner together, by invitation of Mr. Williams, and ate heartily of good, wholesome fare.

After dinner we paid a visit to the shafts at the mine, sunk to a considerable depth in two or three places. Only a few men were at work on one of the shafts; the others seemed to be employed on the saw-mill erecting near the mouth of the river. Others were at work in cutting timbers, &c.

They had also a crushing-mill in a state of forwardness, near the mine.

It is what has been said, and put forth about the value of this mineral deposite, which has done more to incite and feed the copper fever than all other things put together.

Professor Charles Thomas Jackson.

~ Contributions to the History of American Geology, plate 11, opposite page 290.

Dr. Jackson was up here last year, and has this year come up again in the service of the company. Without going very far to explore the country elsewhere, he has certainly been heard to make some very extravagant declarations about this mine,- such as that he “considered it worth a million of dollars;” that some of the ore raised was “worth $2,000 or $3,000 per ton!” So extravagant have been the talk and calculations about this mine, that shares (in its brief lease) have been sold, it is said, for $500 per share! – or more, perhaps!! No doubt, many members of the company are sincere, and actually believe the mine to be immensely valuable. Mr. Williams and General Wilson, both stockholders, strike a trade between themselves. One agrees or offers to give the other $36,000 for his interest, which the other consents to take. This transaction, under some mysterious arrangement, appears in the newspapers, and is widely copied.

Without wishing to give an opinion as to the value and permanency of this mine, (in which many persons have become, probably, seriously involved,) even were I as well qualified to do so as some others, I can only state what are the views of some scientific and practical gentlemen with whom I fell in while in the country, who were from the eastern cities, and carefully examined the famous Eagle river silver and copper mine. I do not allude to Dr. Houghton; for he declines to give an opinion to any one about any part of the country.

“The remarkable copper-silver ‘halfbreed’ specimen shown above comes from northern Michigan’s Portage Lake Volcanic Series, an extremely thick, Precambrian-aged, flood-basalt deposit that fills up an ancient continental rift valley.”

~ Shared with a Creative Commons license from James St. John

They say this mine is a deposite mine of native silver and copper in pure trap-rock, and no vein at all; that it presents the appearance of these metals being mingled broadcast in the mass of trap-rock; that, in sinking a shaft, the constant danger is, that while a few successive blasts may bring up very rich specimens of the metals, the succeeding blast or stroke of the pick-axe may bring up nothing but plain rock. In other words, that, in all such deposite mines, including deposition of diffused particles of native meteals, there is no certainly their PERMANENT character. How far this mine will extend through the trap, or how long it will hold out, is a matter of uncertainty. Indeed, time alone will show.

It is said metallic veins are most apt to be found in a permanent form where the mountain limestone and trap come in contact.

I have no prejudice against the country, or any parties whatever. I sincerely wish the whole mineral district, and the Eagle mine in particular, were as rich as it has been represented to be. I should like to see such vast mineral wealth as it has been held forth to be, added to the resources of the country.

Unless Dr. Pettit has succeeded in fixing the vein of black oxide in the side of the mountain or hill, it is believed by good judges that no permanent vein has yet been discovered, as far as has come to their knowledge, in the country!! That much of the conglomerate and trap-rock sections of the country, however, presents strong indications and widely diffused appearances of silver and copper ores, cannot be denied; and from the great number of active persons engaged in making explorations, it is possible, if not probable, that valuable veins may be discovered in some portions of the country.

To find such out, however, if they exist, unless by accident, must be the work of time and labor – perhaps of years – as the interior is exceedingly difficult, or rather almost impossible, to examine, on account of the impenetrable nature of the woods.

During our long and tedious journey, we were favored with a good deal of fine weather. We however experienced, first and last, five or six thunderstorms, and some tolerably severe gales.

Coasting for such a great length, and camping out at night, was not without some trials and odd incidents – mixed with some considerable hardships.

On the night before we reached La Pointe, we camped on a rough pebbly beach, some six or eight miles east of Montreal river, under the lea of some high clay cliffs. We kindled our fire on what appeared to be a clear bed of rather large and rounded stones, at the mouth of a gorge in the cliffs.

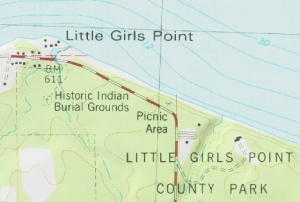

Topographic map of the gorge in the cliffs at Little Girl’s Point County Park.

~ United States Geological Survey

Next morning early, the fire was rekindled at the same spot, although some rain had falled in the night it being still cloudy, and heavy thunder rolling, indicating an approaching storm. I had placed some potatoes in the fire to roast, while some of the voyageurs were getting other things ready for breakfast; but before we could get anything done, the rain down upon us in torrents. We soon discovered that we had kindled our fire in the bed of a wet weather creek. The water rapidly rose, put out the fire, and washed away my potatoes.

We had then to kindle a new fire at a higher place, which was commenced at the end of a small crooked log. One of the voyageurs had set the frying-pan on the fire with an Indian pone or cake an inch thick, and large enough to cover the bottom it. The under side had begun to bake; another hand had mixed the coffee, and set the coffee-pot on to boil; while a third had been nursing a pot boiling with pork and potatoes, which, as we were detained by rain, the voyageurs thought best to prepare for two meals. One of the part, unfortunately, not observing the connexion between the crooked pole, and the fire at the end of it, jumped with his whole weight on it, which caused it suddenly to turn. In its movement, it turned the frying-pan completely over on the sand, with its contents, which became plastered to the dirt. The coffee-pot was also trounced bottom upwards, and emptied its contents on the sand. The pot of potatoes and pork, not to be outdone, turned over directly into the fire, and very nearly extinguished it. We had, in a measure, to commence operations anew, it being nearly 10 o’clock before we could get breakfast. When near the Madelaine islands, (on the largest of which La Pointe is situated,) the following night, our pilot, amidst the darkness of the evening, got bewildered for a time, when we thought best to land and camp; which, luckily for us, was at a spot within sight of La Pointe. Many trifling incidents of this character befell us in our long journey.

Lake Bands:

“Ki ji ua be she shi, 1st [Chief].

Ke kon o tum, 2nd [Chief].”

Pelican Lakes:

“Kee-che-waub-ish-ash, 1st chief, his x mark.

Nig-gig, 2d chief, his x mark.“

Lac Courte Oreilles Band:

At the mouth of the Montreal river, we fell in with a party of seventeen Indians, composed of old Martin and his band, on their way to La Pointe, to be present at the payment expected to take place about the 15th of August.

They had their faces gaudily painted with red and blue stripes, with the exception of one or two, who had theirs painted quite black, and were said to be in mourning on account of deceased friends. They had come from Pelican lake (or, as the French named it, Lac du Flambeau,) being near the headwaters of the Wisconsin river, and one hundred and fifty miles distant. They had with them their wives; children, dogs, and all, walked the whole way. They told our pilot, Jean Baptiste, himself three parts Indian, that they were hungry, and had no canoe with which to get on to La Pointe. We gave them some corn meal, and received some fish from them for a second supply. For the Indians, if they have anything they think you want, never offer generally to sell it to you, till they have first begged all they can; then they will produce their fish, &c., offering to trade; for which they expect an additional supply of the article you have been giving them. Baptiste distributed among them a few twists of tobacco, which seemed very acceptable. Old Martin presented Baptiste with a fine specimen of native copper which he had picked up somewhere on his way – probably on the headwaters of the Montreal river. He desired us to take one of his men with us to La Pointe, in order that he might carry a canoe back to the party, to enable them to reach La Pointe the next day, which we accordingly complied with. We dropped him, however, at his own request, on the point of land some miles south of La Pointe, where he said he had an Indian acquaintance, who hailed him from shore.

Having reached La Pointe, we were prepared to rest a few days, before commencing our voyage to the Mississippi river.

Of things hereabouts, and in general, I will discourse in my next.

In great haste I am,

Very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

MORGAN.

To be continued in La Pointe…

La Pointe Bands Part 1

April 19, 2015

By Leo Filipczak

On March 8th, I posted a map of Ojibwe people mentioned in the trade journals of Perrault, Curot, Nelson, and Malhoit as a starting point to an exploration of this area at the dawn of the 19th Century. Later the map was updated to include the journal of John Sayer.

In these journals, a number of themes emerge, some of which challenge conventional wisdom about the history of the La Pointe Band. For one, there is very little mention of a La Pointe Band at all. The traders discuss La Pointe as the location of Michel Cadotte’s trading depot, and as a central location on the lakeshore, but there is no mention of a large Ojibwe village there. In fact, the journals suggest that the St. Croix and Chippewa River basins as the place where the bulk of the Lake Superior Ojibwe could be found at this time.

In the post, I repeated an argument that the term “Band” in these journals is less identifiable with a particular geographical location than it is with a particular chief or extended family. Therefore, it makes more sense to speak of “Giishkiman’s Band,” than of the “Lac du Flambeau Band,” because Giishkiman (Sharpened Stone) was not the only chief who had a village near Lac du Flambeau and Giishkiman’s Band appears at various locations in the Chippewa and St. Croix country in that era.

In later treaties and United State’s Government relations, the Ojibwe came to be described more often by village names (La Pointe, St. Croix, Fond du Lac, Lac du Flambeau, Lac Courte Oreilles, Ontonagon, etc.), even though these oversimplified traditional political divisions. However, these more recent designations are the divisions that exist today and drive historical scholarship.

So what does this mean for the La Pointe Band, the political antecedent of the modern-day Bad River and Red Cliff Bands? This is a complicated question, but I’ve come across some little-known documents that may shed new light on the meaning and chronology of the “La Pointe Band.” In a series of posts, I will work through these documents.

This series is not meant to be an exhaustive look at the Ojibwe at Chequamegon. The goal here is much narrower, and if it can be condensed into one line of inquiry, it is this:

Fourteen men signed the Treaty of 1854 as chiefs and headmen of the La Pointe Band:

Ke-che-waish-ke, or the Buffalo, 1st chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Chay-che-que-oh, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

A-daw-we-ge-zhick, or Each Side of the sky, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

O-ske-naw-way, or the Youth, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Maw-caw-day-pe-nay-se, or the Black Bird, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Naw-waw-naw-quot, headman, his x mark. [L. S.]

Ke-wain-zeence, headman, his x mark. [L. S.]

Waw-baw-ne-me-ke, or the White Thunder, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Pay-baw-me-say, or the Soarer, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Naw-waw-ge-waw-nose, or the Little Current, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Maw-caw-day-waw-quot, or the Black Cloud, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Me-she-naw-way, or the Disciple, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Key-me-waw-naw-um, headman, his x mark. [L. S.]

She-gog headman, his x mark. [L. S.]

If we consider a “band” as a unit of kinship rather than a unit of physical geography, how many bands do those fourteen names represent? For each of those bands (representing core families at Red Cliff and Bad River), what is the specific relationship to the Ojibwe villages at Chequamegon in the centuries before the treaty?

The Fitch-Wheeler Letter

Chequamegon History spends a disproportionately large amount of time on Ojibwe annuity payments. These payments, which spanned from the late 1830s to the mid-1870s were large gatherings, which produced colorful stories (dozens from the 1855 payment alone), but also highlighted the tragedy of colonialism. This is particularly true of the attempted removal of the payments to Sandy Lake in 1850-1851. Other than the Sandy Lake years, the payments took place at La Pointe until 1855 and afterward at Odanah.

The 1857 payment does not necessarily stand out from the others the way the 1855 one does, but for the purposes of our investigation in this post, one part of it does. In July of that year, the new Indian Agent at Detroit, A.W. Fitch, wrote to Odanah missionary Leonard Wheeler for aid in the payment:

Office Michn Indn Agency

Detroit July 8th 1857

Sir,

I have fixed upon Friday August 21st for the distribution of annuities to the Chippewa Indians of Lake Supr. at Bad River for the present year. A schedule of the Bands which are to be paid there is appended.

I will thank you to apprise the LaPointe Indians of the time of payment, so that they should may be there on the day. It is not necessary that they should be there before the day and I prefer that they should not.

And as there was, according to my information a partial failure in the notification of the Lake De Flambeau and Lake Court Oreille Indians last year, I take the liberty to entrust their notification this year to you and would recommend that you dispatch two trusty Messengers at once, to their settlements to notify them to be at Bad River by the 21st of August and to urge them forward with all due diligence.

It is not necessary for any of these Indians to come but the Chiefs, their headmen and one representative for each family. The women and children need not come. Two Bands of these Indians, that is Negicks & Megeesee’s you will notice are to be notified by the same Messengers to be at L’Anse on the 7th of September that they may receive their pay there instead of Bad River.

I presume that Messengers can be obtained at your place for a Dollar a day each & perhaps less and found and you will please be particular about giving them their instructions and be sure that they understand them. Perhaps you had better write them down, as it is all important that there should be no misunderstanding nor failure in the matter and furthermore you will charge the Messenger to return to Bad River immediately, so that you may know from them, what they have done.

It is my purpose to land the Goods at the mo. of Bad River somewhere about the 1st of Aug. (about which I will write you again or some one at your place) and proceed at once to my Grand Portage and Fond Du Lac payments & then return to Bad River.

Schedule of the Bands of Chipps. of Lake Supr. to be notified of the payment at Bad River, Wisn to be made Friday August 21st for the year 1854.

____________________________

La Pointe Bands.

__________

Maw kaw-day pe nay se [Blackbird]

Chay, che, qui, oh, [Little Buffalo/Plover]

Maw kaw-day waw quot [Black Cloud]

Waw be ne me ke [White Thunder]

Me she naw way [Disciple]

Aw, naw, quot [Cloud]

Naw waw ge won. [Little Current]

Key me waw naw um [Canoes in the Rain] {This Chief lives some distance away}

A, daw, we ge zhick [Each Side of the Sky]

Vincent Roy Sen. {head ½ Breeds.}

Lakes De Flambeau & Court Oreille Bands.

__________

Keynishteno [Cree]

Awmose [Little Bee]

Oskawbaywis [Messenger]

Keynozhance [Little Pike]

Iyawbanse [Little Buck]

Oshawwawskogezhick [Blue Sky]

Keychepenayse [Big Bird]

Naynayonggaybe [Dressing Bird]

Awkeywainze [Old Man]

Keychewawbeshayshe [Big Marten]

Aishquaygonaybe–[End Wing Feather]

Wawbeshaysheence [Little Marten] {I do not know where this Band is but notify it.}

__________

And Negick’s [Otter] & Megeesee’s [Eagle] Bands, which (that is Negicks and Megeesees Bands only) are to be notified by the same Messengers to go to L’Anse the 7th of Sept. for their payt.

Very respectfully

Your Obedt Servt,

A W Fitch

Indn. Agent

Rev. L H Wheeler

Bad River msn.

Source: Wheeler Family Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, Ashland, WI

This letter reveals that in 1857, three years after the Treaty of La Pointe called for the creation of reservations for the La Pointe, Lac du Flambeau, and Lac Courte Oreilles Bands, the existence of these bands as singular political entities was still dubious. The most meaningful designation attached to the bands in the instructions to Wheeler is that of the chief’s name.

Canoes in the Rain and Little Marten clearly live far from the central villages named in the treaty, and Nigig (Otter) and Migizi (Eagle) whose villages at this time were near Lac Vieux Desert or Mole Lake aren’t depicted as attached to any particular reservation village.

Edawigijig (Edawi-giizhig “Both Sides of the Sky”), 1880 (C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections)

Additionally, Fitch makes no distinction between Red Cliff and Bad River. Jechiikwii’o (Little Buffalo) and Vincent Roy Sr. representing the La Pointe mix-bloods could be considered “Red Cliff” chiefs while the rest would be “Bad River.” However, these reservation-based divisions are clearly secondary to the kinship/leadership divisions.

This indicates that we should conceptualize the “La Pointe Band” for the entire pre-1860 historical period as several bands that were not necessarily all tied to Madeline Island at all times. This means of thinking helps greatly in sorting out the historical timeline of this area.

This is highlighted in a curious 1928 statement by John Cloud of Bad River regarding the lineage of his grandfather Edawi-giizhig (Each Side of the Sky), one of the chiefs who signed the 1854 Treaty), to E. P. Wheeler, the La Pointe-born son of Leonard Wheeler:

AN ABRAHAM LINCOLN INDIAN MEDAL

Theodore T. Brown

This medal was obtained by Rev. E. P. Wheeler during the summer of 1928 at Odanah, on the Bad River Indian Reservation, from John Cloud, Zah-buh-deece, a Chippewa Indian, whose grandfather had obtained it from President Abraham Lincoln. His grandfather, A-duh-wih-gee-zhig, was a chief of the La Pointe band of Chippewa. His name signifies “on both sides of the sky or day.” His father was Mih-zieh, meaning a “fish without scales.” The chieftain- ship of A-duh-wih-gee-zhig was certified to by the U. S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs on March 22, 1880.

His father, Mih-zieh, was one of the three chiefs who led the original migration of the Chippewa to Chequamegon Bay, the others being Uh-jih-jahk, the Crane, and Gih-chih-way-shkeenh, or the “Big Plover.” The latter was also sometimes known as Bih-zih-kih, or the “Buffalo.”

A-duh-wih-gee-zhig was a member of the delegation of Lake Superior Chippewa chiefs who went to Washington to see President Lincoln under the guidance of Benjamin G. Armstrong, during the winter of 1861…

~WISCONSIN ARCHEOLOGIST. Vol. 8, No. 3 pg.103

The three chiefs mentioned as leading the “original migration” are well known to history. Waabajijaak, the White Crane, was the father of Ikwezewe or Madeline Cadotte, the namesake of Madeline Island. According to his great-grandson, William Warren, White Crane was in the direct Crane Clan lineage that claimed chieftainship over the entire Ojibwe nation.

Mih-zieh, or Mizay (Lawyerfish) was a prominent speaker for the La Pointe band in the early 19th Century. According to Janet Chute’s research, he was the brother of Chief Buffalo, and he later settled at Garden River, the village of the great “British” Ojibwe chief Zhingwaakoons (Little Pine) on the Canadian side of the Sault.

Bizhiki, of course, is Chief Buffalo, the most famous of the La Pointe chiefs, who died in 1855. Gichi-Weshkii, his other name, is usually translated meaning something along the lines of “Great First Born,” “Great Hereditary Chief,” or more literally as “Great New One.” John Cloud and E. P. Wheeler identify him as the “Big Plover,” which is interesting. Buffalo’s doodem (clan) was the Loon, but his contemporary Zhingwaakoons was of the Plover doodem (Jiichiishkwenh in Ojibwe). How this potentially relates to the name of Buffalo’s son Jechiikwii’o (identified as “Snipe” by Charles Lippert) is unclear but worthy of further investigation.

The characterization of these three chiefs leading the “original migration” to Chequamegon stands at odds with everything we’ve ever heard about the first Ojibwe arrival at La Pointe. The written record places the Ojibwe at Chequamegon at least a half century before any of these chiefs were born, and many sources would suggest much earlier date. Furthermore, Buffalo and White Crane are portrayed in the works of William Warren and Henry Schoolcraft as heirs to the leadership of the “ancient capital” of the Ojibwes, La Pointe.

Warren and Schoolcraft knew Buffalo personally, and Warren’s History of the Ojibways even includes a depiction of Buffalo and Daagwagane (son of White Crane, great uncle of Warren) arguing over which of their ancestors first reached Chequamegon in the mists of antiquity. Buffalo and Daawagane’s exchange would have taken a much different form if they had been alive to see this “original migration.”

Still, Cloud and Wheeler’s statement may contain a grain of truth, something I will return to after filling in a little background on the controversies and mysteries surrounding the timeline of the Ojibwe bands at La Pointe.

TO BE CONTINUED

Chief Buffalo, Flat Mouth, and Tecumseh

April 28, 2013

The Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa painted by Charles Bird King c.1820 (Wikimedia Commons)

The Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa painted by Charles Bird King c.1820 (Wikimedia Commons)In contrast with other Great Lakes nations, the Lake Superior Ojibwe are often portrayed as not having had a role in the Seven Years War, Pontiac’s War, Tecumseh’s War, or the War of 1812. The Chequamegon Ojibwe are often characterized as being uniformly friendly toward whites, peacefully transitioning from the French and British to the American era. The Ojibwe leaders Buffalo of La Pointe and Flat Mouth of Leech Lake are seen as men who led their people into negotiations rather than battle with the United States.

No one tried harder to promote the idea of Ojibwe-American friendship than William W. Warren (1825-1853), the Madeline Island-born mix-blooded historian who wrote History of the Ojibway People. Warren details Ojibwe involvement in all of these late-18th and early 20th-century imperial conflicts, but then repeatedly dismisses it as solely the work of more easterly Ojibwe bands or a few rogue warriors. The reality was much more complicated.

It is true, the Lake Superior Ojibwe never entered into these wars as a single body, but the Lake Superior Ojibwe rarely did anything as a single body. Different bands, chiefs, and families pursued different policies. What is clear from digging deeper into the sources, however, is that the anti-American resistance ideologies of men like the Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa (The Prophet) had more followers around here than Warren would have you believe. The passage below, from none other than Warren himself, shows that these followers included Buffalo and Flat Mouth.

History of the Ojibway People is available free online, but I’m not going to link to it. I want you to check out or buy the second edition, edited and annotated by Theresa Schenck and published by the Minnesota Historical Society in 2009. It is not the edition I first read this story in, but this post does owe a great debt to Dr. Schenck’s footnotes. Also, if you get the book, you will find the added bonus of a second account of these same events from Julia Warren Spears, William’s sister (Appendix C). The passage that is reproduced here can be read on pages 227-231.

“… no event of any importance occured on the Chippeway and Wisconsin Rivers till the year 1808, when, under the influence of the excitement which the Shaw-nee prophet, brother of Tecumseh, succeeded in raising, even to the remotest village of the Ojibways, the men of the Lac Coutereille village, pillaged the trading house of Michel Cadotte at Lac Coutereilles, while under charge of a clerk named John Baptiste Corbin. From the lips of Mons. Corbin, who is still living at Lac Coutereille, at the advanced age of seventy-six years, and who has now been fifty-six years in the Ojibway country, I have obtained a reliable account of this transaction…”

“…In the year 1808, during the summer while John B. Corbin had charge of the Lac Coutereille post, messengers, whose faces were painted black, and whose actions appeared strange, arrived at the different principal villages of the Ojibways. In solemn councils they performed certain ceremonies, and told that the Great Spirit had at last condescended to hold communion with the red race, through the medium of a Shawano prophet, and that they had been sent to impart the glad tidings.

The Shawano sent them word that the Great Spirit was about to take pity on his red children, whom he had long forsaken for their wickedness. He bade them to return to the primitive usages and customs of their ancestors, to leave off the use of everything which the evil white race had introduced among them. Even the fire-steel must be discarded, and fire made as in ages past, by the friction of two sticks. And this fire, once lighted in their principal villages, must always be kept sacred and burning. He bade them to discard the use of fire-water—to give up lying and stealing and warring with one another. He even struck at some of the roots of the Me-da-we religion, which he asserted had become permeated with many evil medicines, and had lost almost altogether its original uses and purity. He bade the medicine men to throw away their evil and poisonous medicines, and to forget the songs and ceremonies attached thereto, and he introduced new medicines and songs in their place. He prophesied that the day was nigh, when, if the red race listened to and obeyed his words, the Great Spirit would deliver them from their dependence on the whites, and prevent their being finally down-trodden and exterminated by them. The prophet invited the Ojibways to come and meet him at Detroit, where in person, he would explain to them the revelations of the “Great Master of Life.” He even claimed the power of causing the dead to arise, and come again to life.

It is astonishing how quickly this new belief obtained possession in the minds of the Ojibways. It spread like wild-fire throughout their entire country, and even reached the remotest northern hunters who had allied themselves with the Crees and Assiniboines. The strongest possible proof which can be adduced of their entire belief, is in their obeying the mandate to throw away their medicine bags, which the Indian holds most sacred and inviolate. It is said that the shores of Sha-ga-waum-ik-ong were strewed with the remains of medicine bags, which had been committed to the deep. At this place, the Ojibways collected in great numbers. Night and day, the ceremonies of the new religion were performed, till it was at last determined to go in a body to Detroit, to visit the prophet. One hundred and fifty canoes are said to have actually started from Pt. Shag-a-waum-ik-ong for this purpose, and so strong was their belief, that a dead child was brought from Lac Coutereille to be taken to the prophet for resuscitation.

This large party arrived on their foolish journey, as far as the Pictured Rocks, on Lake Superior, when, meeting with Michel Cadotte, who had been to Sault Ste. Marie for his annual outfit of goods, his influence, together with information of the real motives of the prophet in sending for them, succeeded in turning them back.

The few Ojibways who had gone to visit the prophet from the more eastern villages of the tribe, had returned home disappointed, and brought back exaggerated accounts of the suffering through hunger, which the proselytes of the prophet who had gathered at his call, were enduring, and also giving the lie to many of the attributes which he had assumed. It is said that at Detroit he would sometimes leave the camp of the Indians, and be gone, no one knew whither, for three and four days at a time. On his return he would assert that he had been to the spirit land and communed with the master of life. It was, however, soon discovered that he only went and hid himself in a hollow oak which stood behind the hill on which the most beautiful portion of Detroit City is now built. These stories became current among the Ojibways, and each succeeding year developing more fully the fraud and warlike purpose of the Shawano, the excitement gradually died away among the Ojibways, and the medicine men and chiefs who had become such ardent believers, hung their heads in shame whenever the Shawano was mentioned.

Two men of “strong minds and unusual intelligence,” Buffalo of La Pointe (top) and Eshkibagikoonzhe or “Flat Mouth” of Leech Lake. (Wisconsin Historical Society) (Minnesota Historical Society)

Two men of “strong minds and unusual intelligence,” Buffalo of La Pointe (top) and Eshkibagikoonzhe or “Flat Mouth” of Leech Lake. (Wisconsin Historical Society) (Minnesota Historical Society)At this day it is almost impossible to procure any information on this subject from the old men who are still living, who were once believers and preached their religion, so anxious are they to conceal the fact of their once having been so egregiously duped. The venerable chiefs Buffalo, of La Pointe, and Esh-ke-bug-e-coshe, of Leech Lake, who have been men of strong minds and unusual intelligence, were not only firm believers of the prophet, but undertook to preach his doctrines.

One essential good resulted to the Ojibways through the Shawano excitement–they threw away their poisonous roots and medicines, and poisoning, which was formerly practiced by their worst class of medicine men, has since become entirely unknown.

So much has been written respecting the prophet and the new beliefs which he endeavored to inculcate amongst his red brethren, that we will no longer dwell on the merits or demerits of his pretended mission. It is now evident that he and his brother Tecumseh had in view, and worked to effect, a general alliance of the red race, against the whites, and their final extermination from the ‘Great Island which the great spirit had given as an inheritance to his red children.’”

From 1805 to 1811, the Shawnee Prophet Tenskwatawa and his brother Tecumseh spread a religious and political message from the Canadas in the north, to the Gulf of Mexico in the south, to the prairies of the west. They called for all Indians to abandon white ways, unite as one people, and create a British-protected Indian country between the Ohio and the Great Lakes. While he seldom convinced entire nations (including the Shawnee) to join him, Tecumseh gained followers from all over.

This picture of Tecumseh in British uniform was painted decades after his death by Benson John Lossing (Wikimedia Commons)

This picture of Tecumseh in British uniform was painted decades after his death by Benson John Lossing (Wikimedia Commons)His coalition came apart, however, at the Battle of Tippecanoe on November 7, 1811. Tecumseh was away recruiting more followers when American forces under William Henry Harrison defeated Tenskwatawa. Accounts suggest it was a closely-fought battle with the Americans suffering the most casualties. However, in the end Harrison prevailed due to his superior numbers.

With Tenskwatawa discredited, Tecumseh ended up raising a new coalition to fight alongside the British against the Americans in the War of 1812. He was killed in the Battle of the Thames, October 5, 1813, when the British forces under General Henry Procter abandoned their Indian allies on the battlefield.

After the War of 1812, British traders pulled out of their posts in American territory. However, the Ojibwe of Lake Superior continued to trade across the line in Canada. In 1822, the American agent Henry Schoolcraft’s gave his first description of Buffalo, a man he would come to know well over the next thirty-five years. He described “a chief decorated with British insignia.” Ten years later, Flat Mouth was telling Schoolcraft he had no right or ability to stop the Ojibwe from allying with the British. These chiefs were not men who were unwavering friends of the United States for their whole lives.

Buffalo and Flat Mouth lived to be very old men, and lived to see the Ojibwe cede their lands in treaties, suffer the tragic 1850-51 removal to Sandy Lake, and see the beginnings of a paternalist American regime on the newly-created reservations. Their Shawnee contemporary, Tecumseh, did not live that long.

Tecumseh’s life and death are documented in the second episode of the 2009 television miniseries American Experience: We Shall Remain. The episode, Tecumseh’s Vision, is very good throughout. The most interesting part comes at the very end when several of the expert interviewees comment on the meaning of Tecumseh’s death:

“I think Tecumseh is, in a sense, saved by his death. He’s saved for immortality through death on the battlefield.”

Stephen Warren, Augustana College

“One of the great things in icons is to bow out at the right time, and one of the things Tecumseh does is he never lets you down. He was there, articulating his position — uncompromisingly pro-Native American position. He never signs the treaties. He never reneges on those basic as principles of the sacrosanct aboriginal holding of this territory. He bows out at the peak of this great movement he is leading. He’s there, right at the end, whatever the odds are, fighting for it into the dying moments.”

John Sugden, author Tecumseh: A Life

“For some people, they may call him a troublemaker. And I think that’s because, in the end, he lost. Had he won, he’d have been, you know, a hero. But I think, to a degree, he still has to be recognized as a hero, for what he attempted to do. If he had a little more help, maybe he would have got a little farther down the line. If the British would have backed him up, like they were supposed to have, maybe the United States is only half as big as it is today.”

Sherman Tiger, Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

Stephen Warren and John Sugden indicate that he is a hero because of the way he died. Sherman Tiger seems to say that Tecumseh’s death, in part, is what kept him from being a hero, and that if he had more men, maybe his “vision” of a united Indian nation would have come true.

In 1811, the Ojibwe of Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi had hundreds of warriors experienced in battle with the Dakota Sioux. They were heirs to a military tradition that defeated the Iroquois and the Meskwaki (Fox). A handful of Ojibwe did fight beside Tecumseh, and according to John Baptiste Corbine through Warren, many more could have. It’s possible they could have tipped the balance and caused Tippecanoe or Thames to end differently. It is also possible that Buffalo, Flat Mouth, and other future Ojibwe leaders could have died on the battlefield.

Tecumseh died young and uncompromised. Buffalo and Flat Mouth faced many tough decisions and lived long enough to see their people lose their independence and most of their land. However, they were there to lead their people through the hard times of the removal period. Tecumseh wasn’t.

Ultimately, it’s hard to say which is more heroic? What do you think?

Sources:

Schenck, Theresa M., William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi,. [East Lansing]: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers: With Brief Notices of Passing Events, Facts, and Opinions, A.D. 1812 to A.D. 1842. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and, 1851. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1991. Print.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.