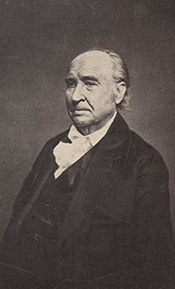

Colonel Charles Whittlesey

May 27, 2016

By Amorin Mello

C.C. Baldwin was a friend, colleague, and biographer of Charles Whittlesey.

~ Memorial of Charles Candee Baldwin, LL. D.: Late President of the Western Reserve Historical Society, 1896, page iii.

This is a reproduction of Colonel Charles Whittlesey’s biography from the Magazine of Western History, Volume V, pages 534-548, as published by his successor Charles Candee Baldwin from the Western Reserve Historical Society. This biography provides extensive and intimate details about the life and profession of Whittlesey not available in other accounts about this legendary man.

Whittlesey came to Lake Superior in 1845 while working for the Algonquin Mining Company along the Keweenaw Peninsula’s copper region. His first trip to Chequamegon Bay appears to have been in 1849 while doing do a geological survey of the Penokee Mountains for David Dale Owen. Whittlesey played a dramatic role in American settlement of the Chequamegon Bay region. Whittlesey convinced his brother, Asaph Whittlesey Jr., to move from the Western Reserve in 1854 establish what became the City of Ashland at the head of Chequamegon Bay as a future port town for extracting and shipping minerals from the Penokee Mountains. Whittlesey’s influence can still be witnessed to this day through local landmarks named in his honor:

Whittlesey published more than two hundred books, pamphlets, and articles. For additional research resources, the extensive Charles Whittlesey Papers are available through the Western Reserve Historical Society in two series:

Magazine of Western History, Volume V, pages 534-548.

COLONEL CHARLES WHITTLESEY.

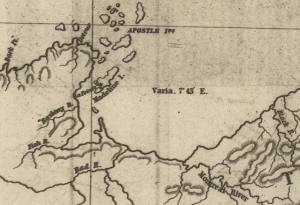

Map of the Connecticut Western Reserve in Ohio by William Sumner, September 1826.

~ Cleveland Public Library

![Asaph Whittlesey [Sr], Late of Tallmadge, Summit Co., Ohio by Vesta Hart Whittlesey and Susan Everett Whittlesey, né Fitch, 1872.](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/asaph-whittlesey-vesta-hart.jpg?w=186&h=300)

[Father] Asaph Whittlesey [Sr], Late of Tallmadge, Summit Co., Ohio by [mother] Vesta Hart Whittlesey [posthumously] and [stepmother] Susan Everett Whittlesey, né Fitch, 1872.

~ Archive.org

War was then in the west, and his neighbors feared they might be the victims of the scalping knife. But the danger was different. In passing the Narrows, between Pittsburgh and Beaver, the wagon ran off a bank and turned completely over on the wife and children. They were rescued and revived, but the accident permanently impaired the health of Mr. Whittlesey.

Mr. Whittlesey was in Tallmadge, justice of the peace from soon after his arrival till near the close of his life, and postmaster from 1814, when the office was first established, to his death. He was again severely injured, but a strong constitution and unflinching will enabled him to accomplish much. He had a store, buying goods in Pittsburgh and bringing them in wagons to Tallmadge; and an ashery; and in 1818 he commenced the manufacture of iron on the Little Cuyahoga, below Middlebury.

The times were hard, tariff reduced, and in 1828 he returned to his farm prematurely old. He died in 1842. Says General Bierce,

“His intellect was naturally of a high order, his religious convictions were strong and never yielded to policy or expediency. He was plain in speech, sometimes abrupt. Those who respected him were more numerous than those who loved him. But for his friends, no one had a stronger attachment. His dislikes were not very well concealed or easily removed. In short, he was a man of strong mind, strong feelings, strong prejudices, strong affections and strong attachments, yet the whole was tempered with a strong sense of justice and strong religious feelings.”

[Uncle] Elisha Whittlesey

~ Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

Portrait of Reverend David Bacon from ConnecticutHistory.org:

“David Bacon (1771 – August 27, 1817) was an American missionary in Michigan Territory. He was born in Woodstock, Connecticut. He worked primarily with the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes, although they were not particularly receptive to his Christian teachings. He founded the town of Tallmadge, Ohio, which later became the center of the Congregationalist faith in Ohio.”

~ Wikipedia.org

Tallmadge was settled in 1808 as a religious colony of New England Congregationalists, by a colony led by Rev. David Bacon, a missionary to the Indians. This affected the society in which the boy lived, and exercised much influence on the morality of the town and the future of its children, one of whom was the Rev. Leonard Bacon. Rev. Timlow’s History of Southington says, “Mr. Whittlesey moved to Tallmadge, having become interested in settling a portion of Portage county with Christian families.” And that he was a man “of surpassing excellence of character.”

If it should seem that I have dwelt upon the parents of Colonel Whittlesey, it is because his own character and career were strongly affected by their characters and history. Charles, the son, combined the traits of the two. He commenced school at four years old in Southington; the next year he attended the log school house at Tallmadge until 1819, when the frame academy was finished and he attended it in winter, working on the farm in summer until he was nineteen.

The boy, too, saw early life on foot, horseback and with ox-teams. He found the Indians still on the Reserve, and in person witnessed the change from savage life and new settlements, to a state of three millions of people, and a large city around him. One of Colonel Whittlesey’s happiest speeches is a sketch of log cabin times in Tallmadge, delivered at the semi-centennial there in 1857.

~ Annual Report on the Geological Survey of the State of Ohio: 1837 by Ohio Geologist William Williams Mather, 1838, page 22.

In 1827 the youngster became a cadet at West Point. Here he displayed industry, and in some unusual incidents there, coolness and courage. He graduated in 1831, and became brevet second lieutenant in the Fifth United States infantry, and in November started to join his regiment at Mackinaw. He did duty through the winter with the garrison at Fort Gratiot. In the spring he was assigned at Green Bay to the company of Captain Martin Scott, so famous as a shot. At the close of the Black Hawk War he resigned from the army. Though recognizing the claim of the country to the services of the graduates of West Point, he tendered his services to the government during the Seminole Mexican war. By a varied experience his life thereafter was given to wide and general uses. He at first opened a law office in Cleveland, Ohio, and was fully occupied in his profession, and as part owner and co-editor of the Whig and Herald until the year 1837. He was that year appointed assistant geologist of the state of Ohio. Through very uneconomical economy, the survey was discontinued at the end of two years, when the work was partly done and no final reports had been made. Of course most of the work and its results were lost. Great and permanent good indeed resulted to the material wealth of the state, in disclosing the rich coal and iron deposit of southeastern Ohio, thus laying the foundation for the vast manufacturing industries which have made that portion of the state populous and prosperous. The other gentlemen associated with him were Professor William Mather as principal; Dr. Kirtland was entrusted with natural history. Others were Dr. S. P. Hildreth, Dr. Caleb Briggs, Jr., Professor John Locke and Dr. J. W. Foster. It was an able corps, and the final results would have been very valuable and accurate. In 1884, Colonel Whittlesey was sole survivor and said in this Magazine:

“Fifty years since, geology had barely obtained a standing among the sciences even in Europe. In Ohio it was scarcely recognized. The state at that time was more of a wilderness than a cultivated country, and the survey was in progress little more than two years. It was unexpectedly brought to a close without a final report. No provision was made for the preservation of papers, field notes and maps.”

Report of Progress in 1869, by J. S. Newberry, Chief Geologist, by the Geological Survey of Ohio, 1870.

Professor Newbury, in a brief resume of the work of the first survey (report of 1869), says the benefits derived “conclusively demonstrate that the geological survey was a producer and not a consumer, that it added far more than it took from the public treasury and deserved special encouragement and support as a wealth producing agency in our darkest financial hour.” The publication of the first board, “did much,” says Professor Newberry, “to arrest useless expenditure of money in the search for coal outside of the coal fields and in other mining enterprises equally fallacious, by which, through ignorance of the teachings of geology, parties were constantly led to squander their means.” “It is scarcely less important to let our people know what we have not, than what we have, among our mineral resources.”

“Descriptions of Ancient Works in Ohio. By Charles Whittlesey, of the late Geological Corps of Ohio.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume III., Article 7, 1852.

The topographical and mathematical parts of the survey were committed to Colonel Whittlesey. He made partial reports, to be found in the ‘State Documents’ of 1838 and 1839, but his knowledge acquired in the survey was of vastly greater service in many subsequent writings, and, as a foundation for learning, made useful in many business enterprises of Ohio. He had, during this survey, examined and surveyed many ancient works in the state, and, at its close, Mr. Joseph Sullivant, a wealthy gentleman interested in archaeology, residing in Columbus, proposed that, he bearing the actual expense, Whittlesey should continue the survey of the works of the Mound Builders, with a view to joint publication. During the years 1839 and 1840, and under the arrangement, he made examination of nearly all the remaining works then discovered, but nothing was done toward their publication. Many of his plans and notes were used by Messrs. Squier & Davis, in 1845 and 1846, in their great work, which was the first volume of the Smithsonian Contributions, and in that work these gentlemen said:

“Among the most zealous investigators in the field of American antiquarian research is Charles Whittlesey, esq., of Cleveland, formerly topographical engineer of Ohio. His surveys and observations, carried on for many years and over a wide field, have been both numerous and accurate, and are among the most valuable in all respects of any hitherto made. Although Mr. Whittlesey, in conjunction with Joseph Sullivant, esq., of Columbus, originally contemplated a joint work, in which the results of his investigations should be embodied, he has, nevertheless, with a liberality which will be not less appreciated by the public than by the authors, contributed to this memoir about twenty plans of ancient works, which, with the accompanying explanations and general observations, will be found embodied in the following pages.

“It is to be hoped the public may be put in possession of the entire results of Mr. Whittlesey’s labor, which could not fail of adding greatly to our stock of knowledge on this interesting subject.”

“Marietta Works, Ohio. Charles Whittlesey, Surveyor 1837.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume I., Plate XXVI.

It will be seen that Mr. Whittlesey was now fairly started, interested and intelligent, in the several fields which he was to make his own. And his very numerous writings may be fairly divided into geology, archaeology, history, religion, with an occasional study of topographical geology. A part of Colonel Whittlesey’s surveys were published in 1850, as one of the Smithsonian contributions; portions of the plans and minutes were unfortunately lost. Fortunately the finest and largest works surveyed by him were published. Among those in the work of Squier & Davis, were the wonderful extensive works at Newark, and those at Marietta. No one again could see those works extending over areas of twelve and fifteen miles, as he did. Farmers cannot raise crops without plows, and the geography of the works at Newark must still be learned from the work of Colonel Whittlesey.

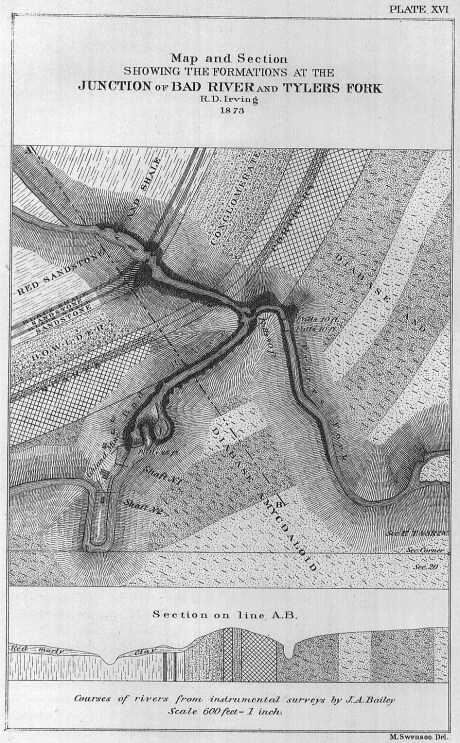

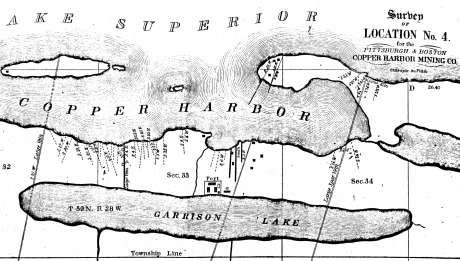

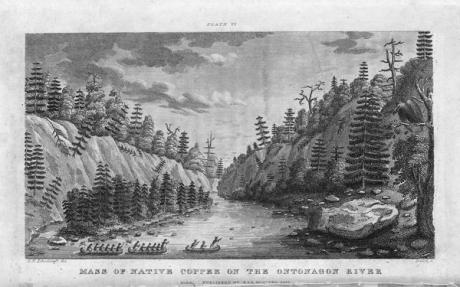

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume XIII., Article IV., page 2 of “Ancient Mining on the Shores of Lake Superior” by Charles Whittlesey.

He made an agricultural survey of Hamilton county in 1844. That year the copper mines of Michigan began to excite enthusiasm. The next year a company was organized in Detroit, of which Colonel Whittlesey was the geologist. In August they launched their boat above the rapids of the Sault St. Marie and coasted along the shore to where is now Marquette. Iron ore was beneath notice, and in truth was no then transportable, and they pulled away for Copper Harbor, and then to the region between Portage lake and Ontonagon, where the Algonquin and Douglas Houghton mines were opened. The party narrowly escaped drowning the night they landed. Dr. Houghton was drowned the same night not far from them. A very interesting and life-like account of their adventures was published by Colonel Whittlesey in the National Magazine of New York City, entitled “Two Months in the Copper Regions.” From 1847 to 1851 inclusive, he was employed by the United States in the survey of the country around Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi, in reference to mines and minerals. After that he spent much time in exploring and surveying the mineral district of the Lake Superior basin. The wild life of the woods with a guide and voyageurs threading the streams had great attractions for him and he spent in all fifteen seasons upon Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi, becoming thoroughly familiar with the topography and geological character of that part of the country.

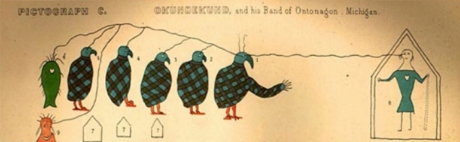

“Pictograph C. Okundekund [Okandikan] and his Band of Ontonagon – Michigan,” as reproduced from birch bark by Seth Eastman, and published as Plate 62 in Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, Volume I., by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, 1851. This was one of several pictograph petitions from the 1849 Martell delegation:

“By this scroll, the chief Kun-de-kund of the Eagle totem of the river Ontonagon, of Lake Superior, and certain individuals of his band, are represented as uniting in the object of their visit of Oshcabewis. He is depicted by the figure of an eagle, Number 1. The two small lines ascending from the head of the bird denote authority or power generally. The human arm extended from the breast of the bird, with the open hand, are symbolic of friendship. By the light lines connecting the eye of each person with the chief, and that of the chief with the President, (Number 8,) unity of views or purpose, the same as in pictography Number 1, is symbolized. Number 2, 3, 4, and 5, are warriors of his own totem and kindred. Their names, in their order, are On-gwai-sug, Was-sa-ge-zhig, or The Sky that lightens, Kwe-we-ziash-ish, or the Bad-boy, and Gitch-ee-man-tau-gum-ee, or the great sounding water. Number 6. Na-boab-ains, or Little Soup, is a warrior of his band of the Catfish totem. Figure Number 7, repeated, represents dwelling-houses, and this device is employed to deonte that the persons, beneath whose symbolic totem it is respectively drawn, are inclined to live in houses and become civilized, in other words, to abandon the chase. Number 8 depicts the President of the United States standing in his official residence at Washington. The open hand extended is employed as a symbol of friendship, corresponding exactly, in this respect, with the same feature in Number 1. The chief whose name is withheld at the left hand of the inferior figures of the scroll, is represented by the rays on his head, (Figure 9,) as, apparently, possessing a higher power than Number 1, but is still concurring, by the eye-line, with Kundekund in the purport of pictograph Number 1.”

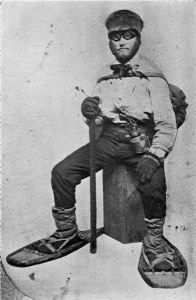

“Studio portrait of geologist Charles Whittlesey dressed for a field trip.” Circa 1858.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

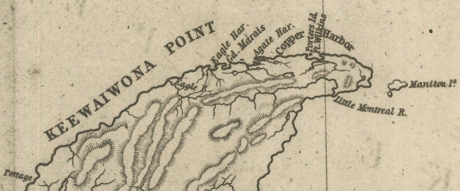

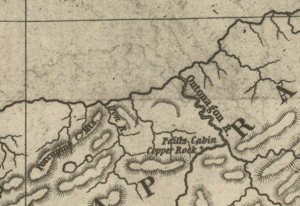

His detailed examination extended along the copper range from the extreme east of Point Keweenaw to Ontonagon, through the Porcupine mountain to the Montreal river, and thence to Long lake in Wisconsin, a distance of two hundred miles. In 1849, 1850 and 1858 he explored the valley of the Menominee river from its mouth to the Brule. He was the first geologist to explore the South range. The Wisconsin Geological Survey (Vol. 3 pp. 490 and 679) says this range was first observed by him, and that he many years ago drew attention to its promise of merchantable ores which are now extensively developed from the Wauceda to the Commonwealth mines, and for several miles beyond. He examined the north shore from Fond du Lac east, one hundred miles, the copper range of Minnesota and on the St. Louis river to the bounds of our country. His report was published by the state in 1865, and was stated by Professor Winchill to be the most valuable made.

All his geological work was thorough, and the development of the mineral resources which he examined, and upon which he reported, gave the best proofs of his scientific ability and judgment.

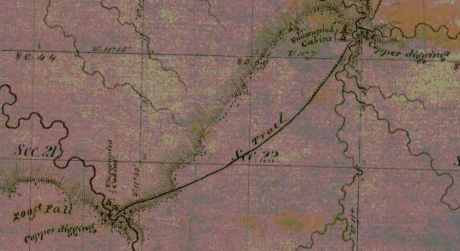

“Outline Map Showing the Position of the Ancient Mine Pits of Point Keweenaw, Michigan by Charles Whittlesey.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume XIII., Article IV., frontpiece of “Ancient Mining on the Shores of Lake Superior” by Charles Whittlesey, 1863.

With the important results from his labors in Ohio in mind, the state of Wisconsin secured his services upon the geological survey of that state, carried on in 1858, 1859 and 1860, and terminated only by the war. The Wisconsin survey was resumed by other parties, and the third volume of the Report for Northern Wisconsin, page 58, says:

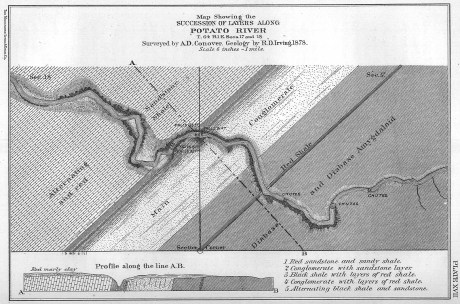

The Contract of James Hall with Charles Whittlesey is available from the Journal of the Assembly of Wisconsin, Volume I, pages 178-179, 1862. Whittlesey was to perform “a careful geological survey of the country lying between the Montreal river on the east, and the westerly branches of [the] Bad River on west”. This contract was unfulfilled due to the outbreak of the American Civil War. Whittlesey independently published his survey of the Penokee Mountains in 1865 without Hall. Some of Whittlesey”s pamphlets have been republished here on Chequamegon History in the Western Reserve category of posts.“The only geological examinations of this region, however, previous to those on which the report is based, and deserving the name, were those of Colonel Charles Whittlesey of Cleveland, Ohio. This gentleman was connected with Dr. D. D. Owen’s United States geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota, and in this connection examined the Bad River country, in 1848. The results are given in Dr. Owen’s final report, published in Washington, in 1852. In 1860 (August to October) Colonel Whittlesey engaged in another geological exploration in Ashland, Bayfield and Douglass counties, as part of the geological survey of Wisconsin, then organized under James Hall. His report, presented to Professor Hall in the ensuing year, was never published, on account of the stoppage of the survey. A suite of specimens, collected by Colonel Whittlesey during these explorations, is at present preserved in the cabinet of the state university at Madison, and it bears testimony to the laborious manner in which that gentleman prosecuted the work. Although the report was never published, he has issued a number of pamphlet publications, giving the main results obtained by him. A list of them, with full extracts from some of them, will be found in an appendix to the report. In the same appendix I have reproduced a geological map of this region, prepared by Colonel Whittlesey in 1860.”

“Geological Map of the Penokie Range.” by Charles Whittlesey, Dec. 1860.

~ Geology of Wisconsin. Survey of 1873-1879. Volume III., 1880, Plate XX, page 214.

~ Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, since its establishment in 1802 by George W. Cullum, page 496.

“The Baltimore Plot was an alleged conspiracy in late February 1861 to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln en route to his inauguration. Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, played a key role by managing Lincoln’s security throughout the journey. Though scholars debate whether or not the threat was real, clearly Lincoln and his advisors believed that there was a threat and took actions to ensure his safe passage through Baltimore, Maryland.”

~ Wikipedia.org

Such was Colonel Whittlesey’s employment when the first signs of the civil war appeared. He abandoned it at once. He became a member of one of the military companies that tendered its services to President-elect Lincoln, when he was first threatened, in February, 1861. He became quickly convinced that war was inevitable, and urged the state authorities that Ohio be put at once in preparation for it; and it was partly through his influence that Ohio was so very ready for the fray, in which, at first, the general government relied on the states. Two days after the proclamation of April 15, 1861, he joined the governor’s staff as assistant quartermaster-general. He served in the field in West Virginia with the three months’ men, as state military engineer; with the Ohio troops, under General McClellan, Cox and Hill. At Seary Run, on the Kanawha, July 17, 1861, he distinguished himself by intrepidity and coolness during a severe engagement, in which his horse was shot under him. At the expiration of the three months’ service, he was appointed colonel of the Twentieth regiment, Ohio volunteers, and detailed by General Mitchell as chief engineer of the department of Ohio, where he planned and constructed the defenses of Cincinnati.

“[Brother] Asaph Whittlesey [Jr.] dressed for his journey from Ashland to Madison, Wisconsin, to take up his seat in the state legislature. Whittlesey is attired for the long trek in winter gear including goggles, a walking staff, and snowshoes.” Circa 1860.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

“SIR: Will you allow me to suggest the consideration of a great movement by land and water, up the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers.

“First, Would it not allow of water transportation half way to Nashville?

“Second, Would it not necessitate the evacuation of Columbus, by threatening their railway communications?

“Third, Would it not necessitate the retreat of General Buckner, by threatening his railway lines?

“Fourth, Is it not the most feasible route into Tennessee?”

This plan was adopted, and Colonel Whittlesey’s regiment took part in its execution.

In April, 1862, on the second day of the battle of Shiloh, Colonel Whittlesey commanded the Third brigade of General Wallace’s division — the Twentieth, Fifty-sixth, Seventy-sixth and Seventy-eighth Ohio regiments. “It was against the line of that brigade that General Beauregard attempted to throw the whole weight of his force for a last desperate charge; but he was driven back by the terrible fire, that his men were unable to face.” As to his conduct, Senator Sherman said in the United States senate.1

The official report of General Wallace leaves little to be said. The division commander says, “The firing was grand and terrible. Before us was the Crescent regiment of New Orleans; shelling us on our right was the Washington artillery of Manassas renown, whose last charge was made in front of Colonel Whittlesey’s command.”

“This is an engraved portrait of Charles Whittlesey, a prominent soldier, attorney, scholar, newspaper editor, and geologist during the nineteenth century. He participated in a geological survey of Ohio conducted in the late 1830s, during which he discovered numerous Native American earthworks. In 1867, Whittlesey helped establish the Western Reserve Historical Society, and he served as the organization’s president until his death in 1886. Whittlesey also wrote approximately two hundred books and articles, mostly on geology and Ohio’s early history.”

~ Ohio History Central

General Force, then lieutenant-colonel under Colonel Whittlesey, fully describes the battle,2 and quotes General Wallace. “The nation is indebted to our brigade for the important services rendered, with the small loss it sustained and the manner in which Colonel Whittlesey handled it.”

Colonel Whittlesey was fortunate in escaping with his life, for General Force says, it was ascertained that the rebels had been deliberately firing at him, sometimes waiting to get a line shot.

Colonel Whittlesey had for some time been in bad health, and contemplating resignation, but deferring it for a decisive battle. Regarding this battle as virtually closing the campaign in the southwest, and believing the Rebellion to be near its end, he now sent it in.

General Grant endorsed his application, “We cannot afford to lose so good an officer.”

“Few officers,” it is said, “retired from the army with a cleaner or more satisfactory record, or with greater regret on the part of their associates.” The Twentieth was an early volunteer regiment. The men were citizens of intelligence and character. They reached high discipline without severity, and without that ill-feeling that often existed between men and their officers. There was no emergency in which they could not be relied upon. “Between them and their commander existed a strong mutual regard, which, on their part, was happily expressed by a letter signed by all the non-commissioned officers.”

“CAMP SHILOH, NEAR PITTSBURGH LANDING, TENNESSEE, April 21, 1862.

“COL. CHAS. WHITTLESEY:

“Sir — We deeply regret that you have resigned the command of the Twentieth Ohio. The considerate care evinced for the soldiers in camp, and, above all, the courage, coolness and prudence displayed on the battle-field, have inspired officers and men with the highest esteem for, and most unbounded confidence in our commander.

“From what we have seen at Fort Donelson, and at the bloody field near Pittsburgh, on Monday, the seventh, all felt ready to follow you unfalteringly into any contest and into any post of danger.

“While giving expression to our unfeigned sorrow at your departure from us, and assurance of our high regard and esteem for you, and unwavering confidence as our leader, we would follow you with the earnest hope that your future days may be spent in uninterrupted peace and quiet, enjoying the happy reflections and richly earned rewards of well-spent service in the cause of our blessed country in its dark hour of need.”

Said Mr. W. H. Searles, who served under him, at the memorial meeting of the Engineers Club of Cleveland: “In the war he was genial and charitable, but had that conscientious devotion to duty characteristic of a West Point soldier.”

Since Colonel Whittlesey’s decease the following letter was received:

“CINCINNATI, November 10, 1886.

“DEAR MRS. WHITTLESEY: — Your noble husband has got release from the pains and ills that made life a burden. His active life was a lesson to us how to live. His latter years showed us how to endure. To all of us in the Twentieth Ohio regiment he seemed a father. I do not know any other colonel that was so revered by his regiment. Since the war he has constantly surprised me with his incessant literary and scientific activity. Always his character was an example and an incitement. Very truly yours,

“M. F. Force.”

Colonel Whittlesey now turned his attention at once again to explorations in the Lake Superior and upper Mississippi basins, and “new additions to the mineral wealth of the country were the result of his surveys and researches.” His geological papers commencing again in 1863, show his industry and ability.

It happened during his life many times, and will happen again and again, that his labors as an original investigator have borne and will bear fruit long afterwards, and, as the world looks at fruition, of much greater value to others than to himself.

~ Report of a geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota: and incidentally of a portion of Nebraska Territory, by David Dale Owen, 1852, page 420.

He prognosticated as early as 1848, while on Dr. Owen’s survey, that the vast prairies of the northwest would in time be the great wheat region. These views were set forth in a letter requested by Captain Mullen of the Topographical Engineers, who had made a survey for the Northern Pacific railroad, and was read by him in a lecture before the New York Geographical society in the winter of 1863-4.

He examined the prairies between the head of the St. Louis river and Rainy Lake, between the Grand fork of Rainy Lake river and the Mississippi, and between the waters of Cass Lake and those of Red Lake. All were found so level that canals might be made across the summits more easily than several summits already cut in this country.

In 1879 the project attracted attention, and Mr. Seymour, the chief engineer and surveyor of New York, became zealous for it, and in his letters of 1880, to the Chambers of Commerce of Duluth and Buffalo, acknowledged the value of the information supplied by Colonel Whittlesey.

Says the Detroit Illustrated News:

“A large part of the distance from the navigable waters of Lake Superior to those of Red river, about three hundred and eight miles, is river channel easily utilized by levels and drains or navigable lakes. The lift is about one thousand feet to the Cass Lake summit. At Red river this canal will connect with the Manitoba system of navigation through Lake Winnipeg and the valleys of the Saskatchewan. Its probable cost is given at less than four millions of dollars, which is below the cost of a railway making the same connections. And it is estimated that a bushel of wheat may be carried from Red river to New York by water for seventeen cents, or about one-third of the cost of transportation by rail.”

We approach that part of the life of Colonel Whittlesey which was so valuable to our society. The society was proposed in 1866.3 Colonel Whittlesey’s own account of its foundation is: “The society originally comprised about twenty persons, organized in May, 1867, upon the suggestion of C. C. Baldwin, its present secretary. The real work fell upon Colonel Whittlesey, Mr. Goodman and Mr. Baldwin, Mr. Goodman devoting nearly all of his time until 1872 (the date of his death).” The statement is a very modest one on the part of Colonel Whittlesey. All looked to him to lead the movement, and none other could have approached his efficiency or ability as president of the society.

The society seemed as much to him as a child is to a parent, and his affection for it has been as great. By his learning, constant devotion without compensation from that time to his death, his value as inspiring confidence in the public, his wide acquaintance through the state, he has accomplished a wonderful result, and this society and its collections may well be regarded as his monument.

Mr. J. P. Holloway, in his memorial notice before the Civil Engineer’s club, of which Colonel Whittlesey was an honorary member, feelingly and justly said:

“Colonel Whittlesey will be best and longest remembered in Cleveland and on the Reserve, for his untiring interest and labors in seeking to rescue from oblivion the pioneer history of this portion of the state, and which culminated in the establishment of the present Western Reserve Historical society, of which for many years he was the presiding officer. It will be remembered by many here, how for years there was little else of the Western Reserve Historical society, except its active, hard working president. But as time moved on, and one by one the pioneers were passing away, there began to be felt an increasing interest in preserving not only the relics of a by-gone generation, but also the records of their trials and struggles, until now we can point with a feeling of pride to the collections of a society which owes its existence and success to a master spirit so recently called away.”

The colonel was remarkably successful in collecting the library, in which he interested with excellent pecuniary purpose the late Mr. Case. He commenced the collection of a permanent fund which is now over ten thousand dollars. It had reached that amount when its increase was at once stopped by the panic of 1873, and while it was growing most rapidly. The permanent rooms, the large and very valuable museum, are all due in greatest measure to the colonel’s intelligent influence and devotion.

I well remember the interest with which he received the plan; the instant devotion to it, the zeal with which at once and before the society was started, he began the preparation of his valuable book, The Early History of Cleveland, published during the year.

Colonel Whittlesey was author of — I had almost said most, and I may with no dissent say— the most valuable publications of the society. His own very wide reputation as an archaeologist and historian also redounded to its credit. But his most valuable work was not the most showy, and consisted in the constant and indefatigable zeal he had from 1867 to 1886, in its prosperity. These were twenty years when the welfare of the society was at all times his business and never off his mind. During the last few years Colonel Whittlesey has been confined to his home by rheumatism and other disorders, the seeds of which were contracted years before in his exposed life on Lake Superior, and he has not been at the rooms for years. He proposed some years since to resign, but the whole society would have felt that the fitness of things was over had the resignation been accepted. Many citizens of Cleveland recall that if Colonel Whittlesey could no longer travel about the city he could write. And it was fortunate that he could. He took great pleasure in reading and writing, and spent much of his time in his work, which continued when he was in a condition in which most men would have surrendered to suffering.

Colonel Whittlesey did not yet regard his labors as finished. During the last few years of his life religion, and the attitude and relation of science to it, engaged much of his thought, and he not unfrequently contributed an editorial or other article to some newspaper on the subject. Lately these had taken more systematic shape, and as late as the latter part of September, and within thirty days of his death, he closed a series of articles which were published in the Evangelical Messenger on “Theism and Atheism in Science.” These able articles were more systematic and complete than his previous writings on the subject, and we learn from the Messenger that they will be published in book form. The paper says:

Colonel Charles Whittlesey of this city, known to our readers as the author of an able series of articles on “Theism and Atheism in Science” just concluded, has fallen asleep in Jesus. One who knew the venerable man and loved him for his genuine worth said to us that “his last work on earth was the preparation of these articles . . . which to him was a labor of love and done for Christ’s sake.”

!["The Old Whittlesey Homestead, Euclid Avenue [Cleveland, Ohio]." ~ Historical Collections of Ohio in Two Volumes, by Henry Howe, 1907, page 521.](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/whittlesey-home-cleveland.jpg?w=300&h=207)

“The Old Whittlesey Homestead, Euclid Avenue.” [Cleveland, Ohio]

~ Historical Collections of Ohio in Two Volumes by Henry Howe, 1907, page 521.

Colonel Whittlesey was married October 4, 1858, to Mrs. Mary E. (Lyon) Morgan4 of Oswego, New York, who survives him; they had no children.

!["Char. Whittlesey - Cleveland Ohio, Oct. 30, 1895[?] - Geologist of Ohio." ~ Wisconsin Historical Society](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/charles-whittlesey-geologist.jpg?w=179&h=300)

Charles Whittlesey died on October 18th, 1886, and was never Ohio’s State Geologist.

“Char. Whittlesey – Cleveland Ohio, Oct. 30, 1895[?] – Geologist of Ohio.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Much of his work does not therefore appear in that complete and systematic shape which would make it best known to the general public. But by scholars in his lines of study in Europe and America, he was well known and very highly respected. “His contributions to literature,” said the New York Herald,5 “have attracted wide attention among the scientific men of Europe and America.”

Whittlesey Culture:

A.D. 1000 to 1600

“‘Whittlesey Culture’ is an archaeological designation referring to a Late Prehistoric (more appropriately: Late Pre-Contact) North American indigenous group that occupied portions of northeastern Ohio. This culture isdistinguished from other so-called Late Prehistoric societies mainly by distinctive kinds of pottery. Many Whittlesey communities were located on plateaus overlooking stream valleys or the shores of Lake Erie. The villages often were surrounded with a pallisade or a ditch, suggesting a need for defense.

“The Whittlesey culture is named for Charles Whittlesey, a 19th century geologist and archaeologist who was a founder of the Western Reserve Historical Society.”

As an American archaeologist, Colonel Whittlesey was very learned and thorough. He had in Ohio the advantage of surveying its wonderful works at an early date. He had, too, that cool poise and self-possession that prevented his enthusiasm from coloring his judgment. He completely avoided errors into which a large share of archaeologists fall. The scanty information as to the past and its romantic interest, lead to easy but dangerous theories, and even suffers the practice of many impositions. He was of late years of great service in exposing frauds, and thereby helped the science to a healthy tone. It may be well enough to say that in one of his tracts he exposed, on what was apparently the best evidence, the supposed falsity of the Cincinnati tablet so called. Its authenticity was defended by Mr. Robert Clarke of Cincinnati, successfully and convincingly, to Colonel Whittlesey himself. I was with the colonel when he first heard of the successful defense and with a mutual friend who thought he might be chagrined, but he was so much more interested in the truth for its own sake, than in his relations to it, that he appeared much pleased with the result.

Whittlesey Culture artifacts: “South Park Village points (above) and pottery fragment (below)”

~ Cuyahoga Valley National Park

Among American writers, Mr. Short speaks of his investigations as of “greater value, due to the eminence of the antiquarian who writes them.” Hon. John D. Baldwin says, “in this Ancient America speaks of Colonel Whittlesey as one of the best authorities.” The learned Frenchman, Marquis de Nadaillac and writers generally upon such subjects quote his information and conclusions with that high and safe confidence in his learning and sound views which is the best tribute to Colonel Whittlesey, and at the same time a great help to the authors. And no one could write with any fullness on the archaeology of America without using liberally the work of Colonel Whittlesey, as will appear in any book on the subject. He was an extensive, original investigator, always observing, thoughtful and safe, and in some branches, as in Ancient Mining at Lake Superior, his work has been the substantial basis of present learning. It is noticeable that the most eminent gentlemen have best appreciated his safe and varied learning. Colonel Whittlesey was early in the geological field. Fifty years ago little was known of paleontology, and Colonel Whittlesey cared little for it, perhaps too little; but in economic geology, in his knowledge of Ohio, its surface, its strata, its iron, its coal and its limestone in his knowledge of the copper and iron of the northwest, he excelled indeed. From that date to his death he studied intelligently these sections. As Professor Lapham said he was studying Wisconsin, so did Colonel Whittlesey give himself to Ohio, its mines and its miners, its manufactures, dealings in coal and iron, its history, archaeology, its religion and its morals. Nearly all his articles contributed to magazines were to western magazines, and anyone who undertook a literary enterprise in the state of Ohio that promised value was sure to have his aid.6

In geology his services were great. The New York Herald, already cited, speaks of his help toward opening coal mines in Ohio and adds,“he was largely instrumental in discovering and causing the development of the great iron and copper regions of Lake Superior.” Twenty-six years ago he discovered a now famous range of iron ore.

“ On the Mound Builders and on the geological character and phenomena of the region of the lakes and the northwest he was quoted extensively as an authority in most of the standard geological and anthropological works of America and Europe,” truthfully says the ‘Biographical Cyclopedia.

Colonel Whittlesey was as zealous in helping to preserve new and original material for history as for science. In 1869 he pushed with energy the investigation, examination and measures which resulted in the purchase by the State of Ohio of the St. Clair papers so admirably, fully and ably edited by Mr. William Henry Smith, and in 1882 published in two large and handsome volumes by Messrs. Robert Clarke and Co. of Cincinnati.

Colonel Whittlesey was very prominent in the project which ended in the publication of the Margry papers in Paris. Their value may be gathered from the writing of Mr. Parkman (La Salle) and The Narrative and Critical History of America, Volume IV., where on page 242 is an account of their publication.7 In 1870 and 1871 an effort to enlist congress failed. The Boston fire defeated the efforts of Mr. Parkman to have them published in that city. Colonel Whittlesey originated the plan eventually adopted, by which congress voted ten thousand dollars as a subscription for five hundred copies, and, as says our history: “at last by Mr. Parkman’s assiduous labors in the east, and by those of Colonel Whittlesey, Mr. O. H. Marshall and others in the west,” the bill was passed.

The late President Garfield, an active member of our society, took a lively interest in the matter, and instigated by Colonel Whittlesey used his strong influence in its favor. Mr. Margry has felt and expressed a very warm feeling for Colonel Whittlesey for his interest and efforts, and since the colonel’s death, and in ignorance of it, has written him a characteristic letter to announce to the colonel, first of any in America, the completion of the work. A copy of the letter follows :

“PARIS, November 4, 1886.

“VERY DEAR AND HONORED SIR: It is to-day in France, St. Charles’ day, the holiday I wished when I had friends so called. I thought it suitable to send you to-day the good news to continue celebrating as of old. You will now be the first in America to whom I write it. I have just given the check to be drawn, for the last leaves of the work, of which your portrait may show a volume under your arm.8 Therefore there is no more but stitching to be done to send the book on its way.

“In telling you this I will not forget to tell you that I well remembered the part you took in that, publication as new, as glorious for the origin of your state, and for which you can congratulate yourself, in thanking you I have but one regret, that Mr. Marshall can not have the same pleasure. I hope that your health as well as that of Madame Whittlesey is satisfactory. I would be happy to hear so. For me if I am in good health it is only by the intervention of providence. However, I have lost much strength, though I do not show it. We must try to seem well.

“Receive, dear and honored sir, and for Madame, the assurance of my profound respect and attachment.

“PIERRE MARGRY.”

Colonel Whittlesey views of the lives of others were affected by his own. Devoted to extending human learning, with little thought of self interest, he was perhaps a little too impatient with others, whose lives had other ends deemed by them more practical. Yet after all, the colonel’s life was a real one, and his pursuits the best as being nearer to nature and far removed from the adventitious circumstances of what is ordinarily called polite life.

He impressed his associates as being full of learning, not from books, but nevertheless of all around — the roads the fields, the waters, the sky, men animals or plants. Charming it was to be with him in excursions; that was really life and elevated the mind and heart.

He was a profoundly religious man, never ostentatiously so, but to him religion and science were twin and inseparable companions. They were in his life and thought, and he wished to and did live to express in print his sense that the God of science was the God of religion, and that the Maker had not lost power over the thing made.

He rounded and finished his character as he finished his life, by joint and hearty affection and service to the two joint instruments of God’s revelation, for so he regarded them. Rev. Dr. Hayden testifies: “He had no patience with materialism, but in his mature strength of mind had harmonized the facts of science with the truths of religion.”

Charles Whittlesey

~ Magazine of Western History, Volume V, page 536.

Colonel Whittlesey’s life was plain, regular and simple. During the last few years he suffered much from catarrhal headache, rheumatism and kindred other troubles, and it was difficult for him to get around even with crutches. This was attributed to the exposure he had suffered for the fifteen years he had been exposed in the Lake Superior region, and his long life and preservation of a clear mind was no doubt due to his simple habits. With considerable bodily suffering, his mind was on the alert, and he seemed to have after all considerable happiness, and, to quote Dr Hayden, he could say with Byrd, “thy mind to me a kingdom is.”

Colonel Whittlesey was an original member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, an old and valued member of the American Antiquarian society, an honorary member of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical society, with headquarters at Columbus. He was trustee of the former State Archaeological society (making the archaeological exhibition at the Centennial), and although each of these is necessarily to some extent a rival of his pet society, he took a warm interest in the welfare of each.

He was a member of the Society of Americanites of France, and his judgment, learning and communications were much esteemed by the French members of that society. Of how many other societies he was an honorary or other member I can not tell.

C. C. Baldwin.

1 – Speech of May 9, 1862.

2 – Cincinnati Commercial, April 9, 1862.

3 – The society was organized under the auspices of the Cleveland Library Association (now Case Library). The plan occurred to the writer while vice-president of that association. At the annual meeting in 1867, the necessary changes were made in the constitution, and Colonel Whittlesey was elected to the Case Library board for the purpose of heading the historical committee and movement. The result appears in a scarce pamphlet issued in 1867 by the library association, containing, among other things, an account of the formation of the society and an address by Colonel Whittlesey, which is an interesting sketch of the successive literary and library societies of Cleveland, of which the first was in 1811.

4 – Mary E. Lyon was a daughter of James Lyon of Oswego, and sister of John E. Lyon, now of Oswego but years ago a prominent citizen of Cleveland. She m. first Colonel Theophilus Morgan,6 Theophilus,5 Theophilus,4 Theophilus,3 John,2 James Morgan.1 Colonel Morgan was an honored citizen of Oswego. Colonel Morgan and his wife Mary, had a son James Sherman, a very promising young man, killed in 1864 in a desperate cavalry charge in which he was lieutenant, in Sherman’s march to the sea. Mrs. Whittlesey survives in Cleveland.

5 – October, 19, 1886.

6 – The Hesperian, American Pioneer, the Western Literary Journal and Review of Cincinnati, the Democratic Review and Ohio Cultivator of Columbus, and later the Magazine of Western History at Cleveland, all received his hearty support.

7 – These papers were also described in an extract from a congressional speech of the late President Garfield. The extract is in Tract No. 20 of the Historical society.

8 – Alluding to a photograph of Colonel Whittlesey

then with a book under his arm.

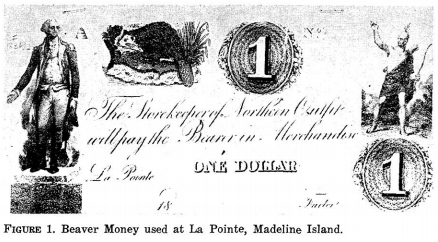

Wisconsin Territory Delegation: La Pointe

April 23, 2016

By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from The Copper Region.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 9, 1845.

La Pointe, Lake Superior

July 26, 1845

To the Editor of the Union:

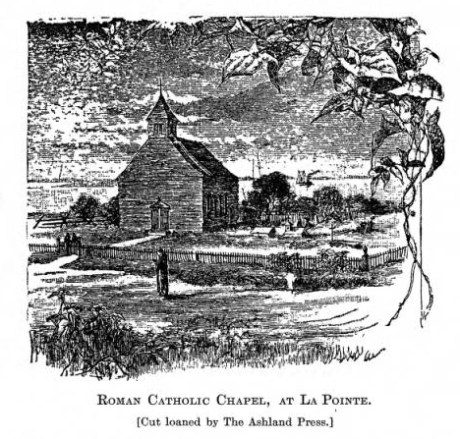

View of La Pointe, circa 1843.

“American Fur Company with both Mission churches. Sketch purportedly by a Native American youth. Probably an overpainted photographic copy enlargement. Paper on a canvas stretcher.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

I have just time to state that, having spent five days at Copper Harbor, examining the copper mine, &c. at that place, and having got everything in readiness, we set off for this place, along the coast, in an open Mackinac boat, travelling by day, and camping out at night. We reached this post on yesterday, the 25th instant. We have now been under tents 21 nights. In coming up the shore of the lake, we on one occasion experienced a tremendous rain accompanied with thunder, which wetted our things to a considerable extent, and partly filled the boat with water.

On our way we spent a good part of a day at Eagle river, and examined the mine in the process of being worked at that place, but found it did not equal our expectations.

We also stopped at the Ontonagon, the mineral region bordering which, some fifteen miles from the lake, promises to be as good as any other portion of the mineral region, if not better.

I have not time at present to enter fully into the results of observations I have made, or to describe the incidents and adventures of the long journey I have performed along the lake shore for the distance of about 500 miles, from Sault Ste. Marie to La Pointe. There are many things I wish to say, and to describe, &c.; but as the schooner “Uncle Tom,” by which I write, is just about leaving, I have not time at present. I must reserve these things for a future opportunity.

I am, very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

MORGAN.

P.S. – I set off in a day or two for the Mississippi and Falls of St. Anthony, via the Brulé and St. Croix rivers.

Yours, &c., M.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 25, 1845

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE

—

[From our regular Northern correspondant.]

La Pointe, Lake Superior,

July 28, 1845.

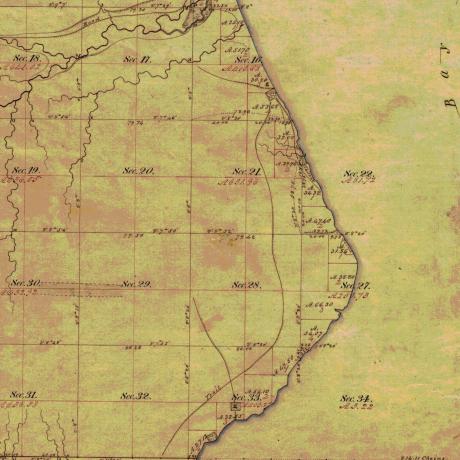

Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

In what I said in my last letter of this date, in relation to the extent, value, and prospects of the copper-mines opened on Lake Superior, I had no wish to dampen the ardor, would the feelings or injure the interest of any one concerned. My only wish is to state facts. This, in all cases, I feel it my duty to do; although, in so doing, as in the present case, my individual interest suffers thereby. Could I have yielded to the impulses and influences prevailing in the copper region, I might have been greatly benefited in a pecuniary point of view by pursuing a different course ; but, knowing those whom I represented, as well as the public and the press for which I write, wanted the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, I could do nothing less than make the statement I did. Previous to visiting the country, I could, of course, know nothing of its real character. I had to judge, like others, from published reports of its mineral wealth, accompanied with specimens, &c., which appeared very flattering; but which, I am now convinced, have been rather overdrawn, and the mineral region set out larger and richer than it really is. The authors of the reports were, doubtlessly, actuated by pure motives. They, no doubt, had a wish, in laying down the boundaries of the mineral region, so to extend it as to leave out no knoll or range of trap-rock, or other formation, if any indicative of mineral deposites, which usually appear in connexion with them, occurred.

I consider, in conclusion, that the result thus far is this: that the mines opened may possibly, in their prosecution, lead to rich and permanent veins; and probably pay or yield something, in some cases, while exploring them. But, however rich the specimens of one raised, at present there is nothing in them, geologically speaking, that indicates, conclusively, that they have reached a vein, or that the mines will continue permanently as rich as they are at present. This would be my testimony, according to the best of “my knowledge and belief,” on the witness’s stand, under oath.

“The remarkable copper-silver ‘halfbreed’ specimen shown above comes from northern Michigan’s Portage Lake Volcanic Series, an extremely thick, Precambrian-aged, flood-basalt deposit that fills up an ancient continental rift valley.”

~ Creative Commons from James St. John

That the region, as before said, is rich in copper and silver ores, cannot be denied. And I think the indications that veins may or do exist somewhere in great richness, are sufficiently evident to justify continued explorations in search of them, by those who have the means and leisure to follow them up for several years. To find the veins, and most permanent deposites, must be the work of time; and as the season is short, on Lake Superior, for such operations, several years may be necessary before a proper and practical examination can be made of the country.

The general features of Lake Superior are very striking, and differ very much in appearance from what I have ever met with in any other part of the continent. The vastness and depth of such a body of pure fresh cold water so far within the continent, is an interesting characteristic. When we consider it is over 900 feet deep, with an area of over 30,000 square miles, and yet that, throughout its whole extent, it presents as pure and as fresh-tasted water as though it were taken from a mountain brook, the question naturally arises, Where can such a vast supply of pure water come from? It is true, it has great many streams flowing into it, but they are nearly all quite small, and would seem to be wholly inadequate to supply such a vast mass of water, and preserve it in such a state of purity. The water supplied by most of the rivers is far less pure than that in the lake itself. East of Keweena point, we found the water of the rivers discolored, being tinged by pine and other roots, clay, &c., often resembling the hue of New England rum. Such rivers, or all combined, would seem to be inadequate to supply such a vast quantity of pure clear water as fills this inland ocean!

~ United States Geological Survey

It is possible that this great lake is freely supplied with water from subterranean springs opening into it from below. The river St. Mary’s also seems inadequate, from its size, to discharge as much water as comes into the lake from the rivers which it receives. In this case, evaporation may be so great as to diminish the water that would otherwise pass out at it.

As relates to tides in the other lakes, we have nothing to say; but, as far as Lake Superior is concerned, we feel assured, from observation, as well as from the reports of others upon whom we can rely, that there are tides in it – variously estimated at from 8 to 12 inches; influenced, we imagine, by the point of observation, and the season of the year at which such tides are noticed.

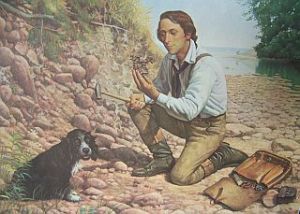

The Voyageurs (1846) by Charles Deas.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

What strikes the voyageur with the most interest, in the way of scenery, is the wild, high, bold, and precipitous coast of the southern shore, for such much of the whole distance between Grand Sable and La Pointe, and, indeed, for some distance beyond La Pointe ; the picturesque appearance of which often seemed heightened to us, as on a clear morning, or late afternoon, or voyageurs would conduct our boat for miles near their bases. Above us, the cliffs would rise in towering heights, while the bald eagle would be soaring in grand circular flights above their summits; our voyageurs, at the same time, chanting in chorus many of their wildest boat songs, as we glided along on the smooth and silent bosom of the lake. I have heard songs among various nations, and in various parts of the world; but, whether it was the wild scenery resting in solemn grandeur before me, with the ocean-like waste of water around us, which lent wilderness to the song, I never listened to any which appeared to sing a verse in solo, and then repeat a chorus, in which the whole crew would join. This would often be continued for several miles at a time, as the boat glided forward over smooth water, or danced along over the gentle swells of a moderate sea; the voyageurs, at the same moment, keeping time with their oars.

Jean Baptiste, our pilot, had an excellent voice, full, loud, and strong. He generally led off, in singing; the others falling in at the choruses. All their songs were in French, sometimes sentimental or pathetic, sometimes comic, and occasionally extempore, made, as sung, from the occurrences of the preceding day, or suggested by passing scenes.

The Chippewa Indians are poor singers; yet they have songs (such as they are) among them; one of which is a monotonous air repeated at their moccasin games.

Stereographic view of a moccasin game, by J. H. Hamilton, 1880.

~ University of Minnesota Duluth

Next to the love of liquor, many of the Indians have a most unconquerable passion for gambling. While at La Pointe, I had an opportunity of seeing them play their celebrated moccasin game. They were to the number of two, or three aside, seated on the ground opposite to each other, which a blanket spread out between them, on which were placed four or five moccasins. The had two lead bullets, one of which was made rough, while the other remained smooth. Two f the gamesters were quite young men, with their faces painted with broad horizontal red and blue stripes, their eyelashes at the same time being dyed of a dark color. They played the game, won and lost, with as much sang froid as old and experienced gamblers. Those who sat opposite, especially one of them, was much older, but no means a match, at the time of my visit, for the young rascals, his antagonists. One takes the balls in his hands, keeps his eye directly on the countenance of the opposite party, at the same time tossing the balls in his hands, and singing, in a changing voice, words which sound somewhat like “He-he-hy-er-he-he-hy-er-haw-haw-haw-yer. He-he-hy-er,” &c. During which he keeps raising, shifting, and putting down the moccasins, till, finally, he raises his hands, having succeeded in concealing the balls under two of the moccasins, for which the other proceeds to search; and if he succeeds, on the first trial, in finding the rough ball, he wins. Then he takes the balls to hide, and commences singing himself. If he fails, he loses; and the first party repeats the song and the secretion of the balls. They hold in their hands small bundles of splinters of wood. When one loses, he gives to the winner so many sticks of wood. A certain number of them gained by any one of the party, wins the game. When I saw them, they had staked up their beads, belts, garters, knife-cases, &c. Their love of gaming is so strong, as to cause them to bet and lose everything they possess in the world – often stripping the last blanket from their naked backs, to stake on the game. It is said that some Indians acquire so much dexterity at this game, that others addicted to it refuse to play with them. In playing the game, they keep up a close watch on each other’s eyes, as being the best index to the movement of the hands. The song is repeated, no doubt, to diver the attention of the antagonists.

Among other peculiarities of Lake Superior, and one of its greatest recommendations, is the abundance and superiority of its fish, consisting of trout of large size, white fish, siskomit, ( a species of salmon,) and bass. The trout and siskomit are the finest and noblest fresh-water fish I ever saw. Almost every day we could catch trout by trailing a hook and line in the water behind out boat. In this way we caught one fine siskomit. Its meat, when fresh-cooked, we found about the color of salmon. The fish itself is about as heavy as a common-sized salmon, but less flat, being more round in form.

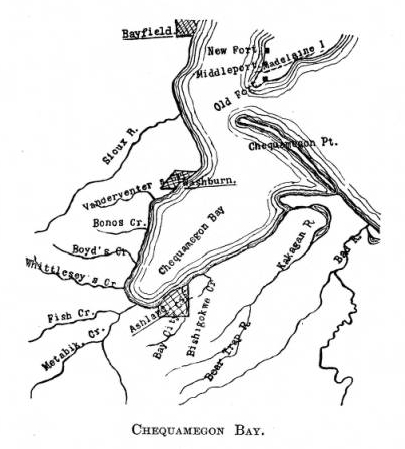

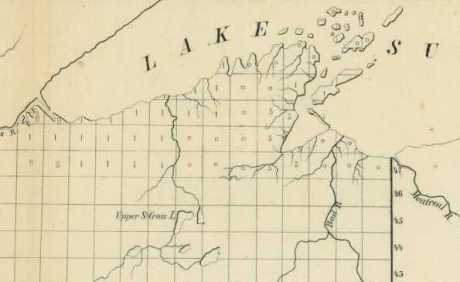

Detail of “The 12 Apostles” from Captain Jonathan Carver’s journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766.

~ Boston Public Library

If you will look at a map of Lake Superior, you will find, near its upper end, a labyrinth of islands, called by the early French voyageurs, of whom P. Charlevoix was one, (a Jesuit,) “the Madelaine islands.” They are sometimes called “the Twelve Apostles.” The largest island is now generally known as “the Madelaine island” – being the largest of the group. Just inside, and near its southern extremity, at the head of a large, regular bay, with a sandy beach, with an open and gently-rising scattered pine and spruce land in the rear of the beach, stands La Pointe – one of the most pleasant, beautiful, and desirable places for a residence on Lake Superior, and the very place where Fort Wilkins should have been placed, instead of its present location, which must be conceded, by every impartial person, to be among the very worst that could have been selected on the whole lake.

The garrison at Copper harbor, located, as it is, upon the rocky surface of trap conglomerate, affording a surface so scantily supplied with soil amidst masses of pebbly rock and trap fragments as to be wholly unfit for any sort of cultivation whatever, is altogether out of place. It is wholly inaccessible by land, and can only be reached by water in summer. It is at a spot where Indians usually never passed within forty miles of it, till since its occupation.

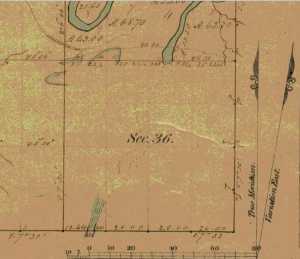

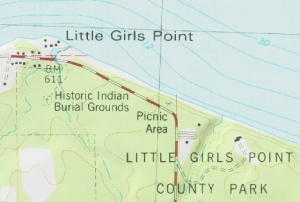

Detail of the Indian trail or “mail route” between La Pointe and St. Anthony Falls.

~ A new map of the State of Wisconsin, by Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co., 1850

The very next Congress should direct its prompt removal to La Pointe. Here, from the foot of the bay in front of the Madelaine island, there is an Indian trail, connecting La Pointe with St. Anthony’s Falls, and over which the mail is carried in winter by voyageurs on foot. La Pointe is the favorite resort of the Indians. Their lodges, in villages, bark canoes, &c. are found here the year round.

They delight to paddle and sail their canoes about the beautiful bays, harbors, &c. of these islands, employing their time in canoe building, hunting, fishing, &c. At every annual payment of their annuities, they flock to La Pointe in great numbers. Not only is that section of the great Chippewa nation sharing in the annuities brought together, but large parties of the same tribe, who receive no annuity, come at the same time from the British possessions to the north of Pigeon river. The Chippewas, called the “Pillageurs,” (so called from their thievish propensities,) inhabiting the country about Mille and Leech lakes, also attend – to meet relations, to traffic , and, perhaps, to steal a little. The great advantage of a government outpost is felt in the moral effect it exercises over the Indians. I know of no place where this influence would be more decidedly and beneficially exerted than at La Pointe. here should be daily unfurled the “stars and stripes,” and the sound of the evening gun be heard over the beautiful bays, and along the shores of the Twelve Apostles, which the Indians would learn to reverence with little less respect than they do the voice of the Manitou – the guardian spirit of the mines, embowelled in the dark trap hills of the lake.

Here, too, is an exceedingly healthy place, a good soil, and every convenience for raising the finest potatoes, turnips, and every kind of garden stuff.

1856 oil painting of Doctor Charles William Wulff Borup, a native of Copenhagen, Denmark. Borup married Elizabeth Beaulieu, a Lake Superior Chippewa daughter of Bazil Hudon Beaulieu and Ogimaagizzhigokwe. Borup and his brothers-in-law Charles Henry Oakes and Clement Hudon Beaulieu were co-signers of the 1842 Treaty with the Chippewa at La Pointe. Borup and Oakes became the first bankers of Minnesota.

Dr. Borup, the agent for the American Fur Company, (who have an extensive trading-post at this place,) has a superb garden. In walking through it with him, I saw very fine crops of the usual garden vegetables growing in it. His red currant bushes were literally bent down beneath their weight of ripe fruit. His cherry-trees had also borne well. Gooseberries also succeed well. The doctor also had some young apple-trees, that were in a thriving condition. Poultry, likewise, does well. Mrs. B. had her yard well stocked with turkeys, geese, ducks, and chickens. There was also a good garden at the mission-house of the American board.

However infinitely better is such a place for a United States garrison than Copper harbor, located, as it were, on a barren rock, where no Indians are seen, unless induced to go there by the whites – where there is nothing to protect – where intercourse is cut off in winter, and food can only reach it in summer – where there is no soil on which to raise a potato or a cabbage. I can only say that a greater blunder, in the location of a military post, was probably never committed. And if made (of which I am assured it was not) by a military man, he ought to be court-martialed and cashiered.

The mouth of the Ontonagon river is a far better spot for the fort than Copper harbor. It has a good soil, and a beautiful site for a fort. Furthermore, the country between it and Fort Winnebago, on the Wisconsin river, is favorable to the construction of a military road, which ought, at no distant day, to be opened. Another road should be cut from Fort Snelling, near the falls of St. Anthony, to La Pointe. In cutting these roads, it would seem to me as if the United States soldiers themselves might be usefully employed.

~ FortWiki.com

While at Copper harbor, I frequently visited Fort Wilkins, in command of Captain Cleary, whom I consider in every way an ornament and an honor to the service. In the brief space of time he has been at this post, and with the slender materials at command afforded by the country, he has nevertheless succeeded in making an “oasis” in a wilderness. He has erected one of the neatest, most comfortable, and best-planned garrisons it has been my lot to enter on the western frontier. He keeps all in excellent condition. His men look clean, healthy, and active. He drills them daily, and keeps them under most excellent discipline. He seems to take both pleasure and ride in the service. He says he never has any difficulty with is soldiers while he can exclude ardent spirits from them, as he succeeds in doing here, notwithstanding the great number of visitors to Copper harbor this summer.

To all travellers who are interested in objects of leading curiosity, the character of the Indians they fall in with cannot fail to arrest a share of attention.

The Chippewas are the only Indians now met with from the Sault Ste. Marie and Mackinac, extending from thence west along the southern shore of Lake Superior, to Fond du Lac, and from thence, in the same direction, to the Mississippi river. Within the United States they extend over the country south from the British boundary, to the country low down on the St. Croix and Chippewa rivers. The same tribe extends from our boundary northwest of the lake, entirely around its northern shore on British territory, till they reach the Sault Ste. Marie, opposite the American shore. It is said this tribe, spread over such a vast tract of country, is a branch of the powerful race of the Algonquins. They are sometimes called O-jib-was. They do not exist as a consolidated nation, or strictly as a confederation of bands. The entire nation on both sides of the line is divided into a great number of bands, with a chief at the head of each, which not uncommonly go by his name, such as “Old Martin’s band,” “Hole in the Day’s band,” &c.

The chief’s son, especially if he exhibits the right qualities, is expected to succeed his father at the head of the band; but very frequently the honor is reached by usurpation. The whole nation, which widely differ in circumstances, according to the part of the country they inhabit, nevertheless all speak the Chippewa language, and have extensive connexion by marriage, &c. The bands inhabiting the southern shore of Lake Superior are by far the best of any others. Though polygamy still prevails among them, and especially among their chiefs, it is nevertheless said to be becoming less common, especially where they are much influenced by Catholic and other missions. While at La Pointe, an Indian wedding was consummated, being conducted according to the ceremonies of the Catholic church, and performed by the missionary priest of that persuasion stationed at the Pointe.

There is one trait of character possessed by the Chippewas, (if we except, perhaps, the band of “pillageurs,” who have a kind of “Bedouin Arab” reputation among their countrymen,) which, I am sorry to say, the whites do not possess in an equal degree – that is, “very great honesty.”

White men can travel among them with the most perfect safety as to life and property. I will venture to say, that a man may carry baskets filled with gold and silver, and set them down in Indian villages, or leave them lying where he likes, or go to sleep by them, with Indians encamped all around him, and not one cent will be touched. Such a thing as a house being broken open and robbed at a Chippewa Indian trading-post was never heard of – within between two and three years’ intercourse with them – in time of peace. Dr. Borup said he would not be afraid, if concealed to look on, to leave his store door open all night; and the fact alone of its being left open, might be made known to the Indians at the Pointe. He would expect to see no Indian enter the store, nor would he expect to lose anything; such was his confidence in their honesty!!

Last winter, flour at the Pointe rose to $40 per barrel. The poor Indians were nearly famished for bread, but were unable to purchase it at such a price. They knew the American Fur Company had a considerable lot in store, guarded by nothing stronger than a padlock, yet they never offered the least violence towards the company’s agents or store! Would white people have acted as honestly? The poor Indians, by nature honest, have too often known the whites by the wrongs inflicted upon them, which God can forgive, but time can never blot out! They are very superstitious, but not as basely and insanely so, but a great deal, as the Mormons, Millerites, and other moon-stricken sects among the whites. They believe in one Great and Good Spirit, or a Being who can at will inflict good or evil on mankind; and there’s an end of it. They often denominate the mysterious spirit of evil import the Manitou, making him to dwell in the wild hills, islands, grottoes, and caves of Lake Superior.

From these huge birds the Indians obtained their first knowledge of fire, which they kindled with fire-sticks. These mythical birds were the most powerful of the animal deities of the Indians of the woodlands and of the plains. When the weather was stormy they flew about high in the heavens. When they flapped their great wings, one heard the crashes of thunder, when they opened and closed their eyes flashes of lightning were seen. Some carried lakes of water on their backs, these slopped over and caused downpours of rain. Their arrows, or thunderbolts, were the eggs which they dropped in their flight. These shattered the rocks and set fire to the forests and prairies.

A Chippewa Indian hunter, who was carried away to his nest by a Thunderer, saved his life by killing one of the young birds and flying back to earth in its feathered hide.

In the Smoky Mountains, a wild and rugged region in the southwestern part of Bayfield County, was the home of Winneboujou (Nenebozho), the fabled hero of the Ojibwa Indians. This all-powerful manitou was a blacksmith, and had his forge on the flat top of the highest mountain. Here he shaped the native copper of the Lake Superior region into useful implements for his Indian children. Much of his work at his forge was done at night, and the ringing blows of his great hammer could be heard throughout the Brule Valley and Lake Superior region. The fire of his forge reddened the sky. When he was not busy at his forge he was away hunting or seeking other adventures. Many stories of the exploits of this giant manitou have been told by the Chippewa and other Wisconsin Algonquian tribes.”

~ Legends of the Hills of Wisconsin by Dorothy Moulding Brown; The Wisconsin Archaeologist, Volume 18, Number 1, 1937, pages 20-21.

At times, it is said, a peculiar noise issues from the Porcupine mountains, and from the high hills on the main land, both east and west of La Pointe, some distance off. It is said to resemble the distant discharge of ordnance, or thunder. At one time, they said it was so loud and frequent, that they mistook it for signal guns fired from the brig Astor, which they thought might be in distress, and actually sent out a boat in search of her.

“Ojibwe shoulder pouch depicting two thunderbirds in quillwork, Peabody Museum, Harvard University.”

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

These sounds the Indians believe to be the voice of the spirit “Manitou,” who guards the deposites of mineral wealth embowelled beneath the hills, and to whom any attempt made to dig them up, and carry them off, would be highly offensive, and followed by some kind of punishment. I have never yet heard of an Indian’s leading a white man to a locality of copper, or telling where he has found a piece when picked up!

Some have supposed that the noise in question arises from volcanic action; but, as no vibration is felt in the earth, and no other proof exists of such being the case, we are led to believe that the noise is produced by the lashing of the waves of the lake after a storm, as they are driven forward into the grottoes, caves, &c. of the tall sandstone cliffs, formed at their bases by the disintegrating effects of water and ice. Some distance east of La Pointe, about the Little Girl’s Point and Montreal river, as well as west of the same place, some fifteen or twenty miles, high red sandstone cliffs occur. At their bases, near the water’s edge, a great many curiously-shaped caves and grottoes appeared. In places, the sandstone had been so cut away, that only pillars remained standing at some ten or fifteen feet in the lake, from the top of which a high rude arch would extend to the main shore, and beneath which boats could easily pass. This was particularly the case near where the islands are parted with going west up the southern shore of the lake. Some caves, with small openings for mouths, run for a long distance back beneath the hills, expanding, likely, into large halls with high vaulted roofs, &c. After a storm, a heavy sea continues to roll into these grottoes and caverns, the waves lashing themselves against their sides and roofs – thus producing sounds resembling those heard at La Pointe, &c.

As the weather is generally calm after a storm, before the sea goes down, it is likely at such times these sounds are heard.

We had occasion to pass these places when a considerable sea would be on, close to the cliffs, and could hear the hollow heavy sounds of the waves as they broke into the caverns within the cliffs and hills. Every day, while we remained, parties of Indians continued to arrive, to be present at the payment.

We finally became prepared to leave for the Mississippi, having bought two bark canoes, and hired four new voyageurs – two for each canoe – one Indian, one half-breed, and two descendants of Canadian French; and, with a stock of provisions, we were ready to be off. From this place, I sent back three voyageurs to the Sault Ste. Marie, all that I hired to come as far as La Pointe. So, after paying our respects to Mr. Hays, our worthy Indian agent, and to Dr. Borup, (to both of whom I had borne letters of introduction,) and having many “bon voyages” heaped upon us by our friends and the friends of the voyageurs, we bade adieu to La Pointe.

You will not hear from me again till I reach the Falls of St. Croix.

I am yours, very truly, &c.

MORGAN.

To be continued in Saint Croix Falls…

Wisconsin Territory Delegation: The Copper Region

April 17, 2016

By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from Copper Harbor.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 21, 1845.

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE.

—

[From our Regular Correspondent.]

THE COPPER REGION.

La Pointe, Lake Superior

July 28, 1845.

Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society