Wisconsin Territory Delegation: La Pointe

April 23, 2016

By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from The Copper Region.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 9, 1845.

La Pointe, Lake Superior

July 26, 1845

To the Editor of the Union:

View of La Pointe, circa 1843.

“American Fur Company with both Mission churches. Sketch purportedly by a Native American youth. Probably an overpainted photographic copy enlargement. Paper on a canvas stretcher.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

I have just time to state that, having spent five days at Copper Harbor, examining the copper mine, &c. at that place, and having got everything in readiness, we set off for this place, along the coast, in an open Mackinac boat, travelling by day, and camping out at night. We reached this post on yesterday, the 25th instant. We have now been under tents 21 nights. In coming up the shore of the lake, we on one occasion experienced a tremendous rain accompanied with thunder, which wetted our things to a considerable extent, and partly filled the boat with water.

On our way we spent a good part of a day at Eagle river, and examined the mine in the process of being worked at that place, but found it did not equal our expectations.

We also stopped at the Ontonagon, the mineral region bordering which, some fifteen miles from the lake, promises to be as good as any other portion of the mineral region, if not better.

I have not time at present to enter fully into the results of observations I have made, or to describe the incidents and adventures of the long journey I have performed along the lake shore for the distance of about 500 miles, from Sault Ste. Marie to La Pointe. There are many things I wish to say, and to describe, &c.; but as the schooner “Uncle Tom,” by which I write, is just about leaving, I have not time at present. I must reserve these things for a future opportunity.

I am, very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

MORGAN.

P.S. – I set off in a day or two for the Mississippi and Falls of St. Anthony, via the Brulé and St. Croix rivers.

Yours, &c., M.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 25, 1845

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE

—

[From our regular Northern correspondant.]

La Pointe, Lake Superior,

July 28, 1845.

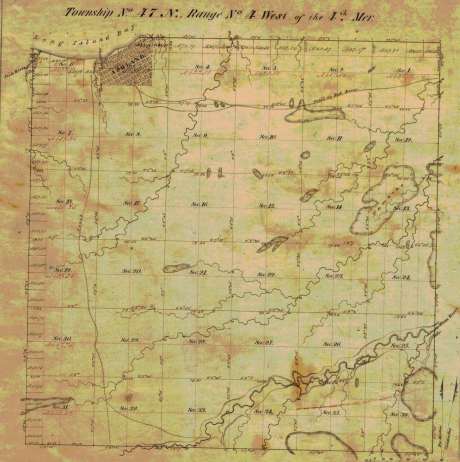

Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

In what I said in my last letter of this date, in relation to the extent, value, and prospects of the copper-mines opened on Lake Superior, I had no wish to dampen the ardor, would the feelings or injure the interest of any one concerned. My only wish is to state facts. This, in all cases, I feel it my duty to do; although, in so doing, as in the present case, my individual interest suffers thereby. Could I have yielded to the impulses and influences prevailing in the copper region, I might have been greatly benefited in a pecuniary point of view by pursuing a different course ; but, knowing those whom I represented, as well as the public and the press for which I write, wanted the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, I could do nothing less than make the statement I did. Previous to visiting the country, I could, of course, know nothing of its real character. I had to judge, like others, from published reports of its mineral wealth, accompanied with specimens, &c., which appeared very flattering; but which, I am now convinced, have been rather overdrawn, and the mineral region set out larger and richer than it really is. The authors of the reports were, doubtlessly, actuated by pure motives. They, no doubt, had a wish, in laying down the boundaries of the mineral region, so to extend it as to leave out no knoll or range of trap-rock, or other formation, if any indicative of mineral deposites, which usually appear in connexion with them, occurred.

I consider, in conclusion, that the result thus far is this: that the mines opened may possibly, in their prosecution, lead to rich and permanent veins; and probably pay or yield something, in some cases, while exploring them. But, however rich the specimens of one raised, at present there is nothing in them, geologically speaking, that indicates, conclusively, that they have reached a vein, or that the mines will continue permanently as rich as they are at present. This would be my testimony, according to the best of “my knowledge and belief,” on the witness’s stand, under oath.

“The remarkable copper-silver ‘halfbreed’ specimen shown above comes from northern Michigan’s Portage Lake Volcanic Series, an extremely thick, Precambrian-aged, flood-basalt deposit that fills up an ancient continental rift valley.”

~ Creative Commons from James St. John

That the region, as before said, is rich in copper and silver ores, cannot be denied. And I think the indications that veins may or do exist somewhere in great richness, are sufficiently evident to justify continued explorations in search of them, by those who have the means and leisure to follow them up for several years. To find the veins, and most permanent deposites, must be the work of time; and as the season is short, on Lake Superior, for such operations, several years may be necessary before a proper and practical examination can be made of the country.

The general features of Lake Superior are very striking, and differ very much in appearance from what I have ever met with in any other part of the continent. The vastness and depth of such a body of pure fresh cold water so far within the continent, is an interesting characteristic. When we consider it is over 900 feet deep, with an area of over 30,000 square miles, and yet that, throughout its whole extent, it presents as pure and as fresh-tasted water as though it were taken from a mountain brook, the question naturally arises, Where can such a vast supply of pure water come from? It is true, it has great many streams flowing into it, but they are nearly all quite small, and would seem to be wholly inadequate to supply such a vast mass of water, and preserve it in such a state of purity. The water supplied by most of the rivers is far less pure than that in the lake itself. East of Keweena point, we found the water of the rivers discolored, being tinged by pine and other roots, clay, &c., often resembling the hue of New England rum. Such rivers, or all combined, would seem to be inadequate to supply such a vast quantity of pure clear water as fills this inland ocean!

~ United States Geological Survey

It is possible that this great lake is freely supplied with water from subterranean springs opening into it from below. The river St. Mary’s also seems inadequate, from its size, to discharge as much water as comes into the lake from the rivers which it receives. In this case, evaporation may be so great as to diminish the water that would otherwise pass out at it.

As relates to tides in the other lakes, we have nothing to say; but, as far as Lake Superior is concerned, we feel assured, from observation, as well as from the reports of others upon whom we can rely, that there are tides in it – variously estimated at from 8 to 12 inches; influenced, we imagine, by the point of observation, and the season of the year at which such tides are noticed.

The Voyageurs (1846) by Charles Deas.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

What strikes the voyageur with the most interest, in the way of scenery, is the wild, high, bold, and precipitous coast of the southern shore, for such much of the whole distance between Grand Sable and La Pointe, and, indeed, for some distance beyond La Pointe ; the picturesque appearance of which often seemed heightened to us, as on a clear morning, or late afternoon, or voyageurs would conduct our boat for miles near their bases. Above us, the cliffs would rise in towering heights, while the bald eagle would be soaring in grand circular flights above their summits; our voyageurs, at the same time, chanting in chorus many of their wildest boat songs, as we glided along on the smooth and silent bosom of the lake. I have heard songs among various nations, and in various parts of the world; but, whether it was the wild scenery resting in solemn grandeur before me, with the ocean-like waste of water around us, which lent wilderness to the song, I never listened to any which appeared to sing a verse in solo, and then repeat a chorus, in which the whole crew would join. This would often be continued for several miles at a time, as the boat glided forward over smooth water, or danced along over the gentle swells of a moderate sea; the voyageurs, at the same moment, keeping time with their oars.

Jean Baptiste, our pilot, had an excellent voice, full, loud, and strong. He generally led off, in singing; the others falling in at the choruses. All their songs were in French, sometimes sentimental or pathetic, sometimes comic, and occasionally extempore, made, as sung, from the occurrences of the preceding day, or suggested by passing scenes.

The Chippewa Indians are poor singers; yet they have songs (such as they are) among them; one of which is a monotonous air repeated at their moccasin games.

Stereographic view of a moccasin game, by J. H. Hamilton, 1880.

~ University of Minnesota Duluth

Next to the love of liquor, many of the Indians have a most unconquerable passion for gambling. While at La Pointe, I had an opportunity of seeing them play their celebrated moccasin game. They were to the number of two, or three aside, seated on the ground opposite to each other, which a blanket spread out between them, on which were placed four or five moccasins. The had two lead bullets, one of which was made rough, while the other remained smooth. Two f the gamesters were quite young men, with their faces painted with broad horizontal red and blue stripes, their eyelashes at the same time being dyed of a dark color. They played the game, won and lost, with as much sang froid as old and experienced gamblers. Those who sat opposite, especially one of them, was much older, but no means a match, at the time of my visit, for the young rascals, his antagonists. One takes the balls in his hands, keeps his eye directly on the countenance of the opposite party, at the same time tossing the balls in his hands, and singing, in a changing voice, words which sound somewhat like “He-he-hy-er-he-he-hy-er-haw-haw-haw-yer. He-he-hy-er,” &c. During which he keeps raising, shifting, and putting down the moccasins, till, finally, he raises his hands, having succeeded in concealing the balls under two of the moccasins, for which the other proceeds to search; and if he succeeds, on the first trial, in finding the rough ball, he wins. Then he takes the balls to hide, and commences singing himself. If he fails, he loses; and the first party repeats the song and the secretion of the balls. They hold in their hands small bundles of splinters of wood. When one loses, he gives to the winner so many sticks of wood. A certain number of them gained by any one of the party, wins the game. When I saw them, they had staked up their beads, belts, garters, knife-cases, &c. Their love of gaming is so strong, as to cause them to bet and lose everything they possess in the world – often stripping the last blanket from their naked backs, to stake on the game. It is said that some Indians acquire so much dexterity at this game, that others addicted to it refuse to play with them. In playing the game, they keep up a close watch on each other’s eyes, as being the best index to the movement of the hands. The song is repeated, no doubt, to diver the attention of the antagonists.

Among other peculiarities of Lake Superior, and one of its greatest recommendations, is the abundance and superiority of its fish, consisting of trout of large size, white fish, siskomit, ( a species of salmon,) and bass. The trout and siskomit are the finest and noblest fresh-water fish I ever saw. Almost every day we could catch trout by trailing a hook and line in the water behind out boat. In this way we caught one fine siskomit. Its meat, when fresh-cooked, we found about the color of salmon. The fish itself is about as heavy as a common-sized salmon, but less flat, being more round in form.

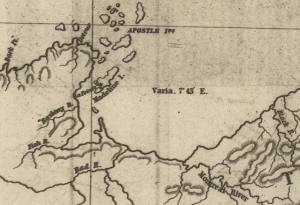

Detail of “The 12 Apostles” from Captain Jonathan Carver’s journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766.

~ Boston Public Library

If you will look at a map of Lake Superior, you will find, near its upper end, a labyrinth of islands, called by the early French voyageurs, of whom P. Charlevoix was one, (a Jesuit,) “the Madelaine islands.” They are sometimes called “the Twelve Apostles.” The largest island is now generally known as “the Madelaine island” – being the largest of the group. Just inside, and near its southern extremity, at the head of a large, regular bay, with a sandy beach, with an open and gently-rising scattered pine and spruce land in the rear of the beach, stands La Pointe – one of the most pleasant, beautiful, and desirable places for a residence on Lake Superior, and the very place where Fort Wilkins should have been placed, instead of its present location, which must be conceded, by every impartial person, to be among the very worst that could have been selected on the whole lake.

The garrison at Copper harbor, located, as it is, upon the rocky surface of trap conglomerate, affording a surface so scantily supplied with soil amidst masses of pebbly rock and trap fragments as to be wholly unfit for any sort of cultivation whatever, is altogether out of place. It is wholly inaccessible by land, and can only be reached by water in summer. It is at a spot where Indians usually never passed within forty miles of it, till since its occupation.

Detail of the Indian trail or “mail route” between La Pointe and St. Anthony Falls.

~ A new map of the State of Wisconsin, by Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co., 1850

The very next Congress should direct its prompt removal to La Pointe. Here, from the foot of the bay in front of the Madelaine island, there is an Indian trail, connecting La Pointe with St. Anthony’s Falls, and over which the mail is carried in winter by voyageurs on foot. La Pointe is the favorite resort of the Indians. Their lodges, in villages, bark canoes, &c. are found here the year round.

They delight to paddle and sail their canoes about the beautiful bays, harbors, &c. of these islands, employing their time in canoe building, hunting, fishing, &c. At every annual payment of their annuities, they flock to La Pointe in great numbers. Not only is that section of the great Chippewa nation sharing in the annuities brought together, but large parties of the same tribe, who receive no annuity, come at the same time from the British possessions to the north of Pigeon river. The Chippewas, called the “Pillageurs,” (so called from their thievish propensities,) inhabiting the country about Mille and Leech lakes, also attend – to meet relations, to traffic , and, perhaps, to steal a little. The great advantage of a government outpost is felt in the moral effect it exercises over the Indians. I know of no place where this influence would be more decidedly and beneficially exerted than at La Pointe. here should be daily unfurled the “stars and stripes,” and the sound of the evening gun be heard over the beautiful bays, and along the shores of the Twelve Apostles, which the Indians would learn to reverence with little less respect than they do the voice of the Manitou – the guardian spirit of the mines, embowelled in the dark trap hills of the lake.

Here, too, is an exceedingly healthy place, a good soil, and every convenience for raising the finest potatoes, turnips, and every kind of garden stuff.

1856 oil painting of Doctor Charles William Wulff Borup, a native of Copenhagen, Denmark. Borup married Elizabeth Beaulieu, a Lake Superior Chippewa daughter of Bazil Hudon Beaulieu and Ogimaagizzhigokwe. Borup and his brothers-in-law Charles Henry Oakes and Clement Hudon Beaulieu were co-signers of the 1842 Treaty with the Chippewa at La Pointe. Borup and Oakes became the first bankers of Minnesota.

Dr. Borup, the agent for the American Fur Company, (who have an extensive trading-post at this place,) has a superb garden. In walking through it with him, I saw very fine crops of the usual garden vegetables growing in it. His red currant bushes were literally bent down beneath their weight of ripe fruit. His cherry-trees had also borne well. Gooseberries also succeed well. The doctor also had some young apple-trees, that were in a thriving condition. Poultry, likewise, does well. Mrs. B. had her yard well stocked with turkeys, geese, ducks, and chickens. There was also a good garden at the mission-house of the American board.

However infinitely better is such a place for a United States garrison than Copper harbor, located, as it were, on a barren rock, where no Indians are seen, unless induced to go there by the whites – where there is nothing to protect – where intercourse is cut off in winter, and food can only reach it in summer – where there is no soil on which to raise a potato or a cabbage. I can only say that a greater blunder, in the location of a military post, was probably never committed. And if made (of which I am assured it was not) by a military man, he ought to be court-martialed and cashiered.

The mouth of the Ontonagon river is a far better spot for the fort than Copper harbor. It has a good soil, and a beautiful site for a fort. Furthermore, the country between it and Fort Winnebago, on the Wisconsin river, is favorable to the construction of a military road, which ought, at no distant day, to be opened. Another road should be cut from Fort Snelling, near the falls of St. Anthony, to La Pointe. In cutting these roads, it would seem to me as if the United States soldiers themselves might be usefully employed.

~ FortWiki.com

While at Copper harbor, I frequently visited Fort Wilkins, in command of Captain Cleary, whom I consider in every way an ornament and an honor to the service. In the brief space of time he has been at this post, and with the slender materials at command afforded by the country, he has nevertheless succeeded in making an “oasis” in a wilderness. He has erected one of the neatest, most comfortable, and best-planned garrisons it has been my lot to enter on the western frontier. He keeps all in excellent condition. His men look clean, healthy, and active. He drills them daily, and keeps them under most excellent discipline. He seems to take both pleasure and ride in the service. He says he never has any difficulty with is soldiers while he can exclude ardent spirits from them, as he succeeds in doing here, notwithstanding the great number of visitors to Copper harbor this summer.

To all travellers who are interested in objects of leading curiosity, the character of the Indians they fall in with cannot fail to arrest a share of attention.

The Chippewas are the only Indians now met with from the Sault Ste. Marie and Mackinac, extending from thence west along the southern shore of Lake Superior, to Fond du Lac, and from thence, in the same direction, to the Mississippi river. Within the United States they extend over the country south from the British boundary, to the country low down on the St. Croix and Chippewa rivers. The same tribe extends from our boundary northwest of the lake, entirely around its northern shore on British territory, till they reach the Sault Ste. Marie, opposite the American shore. It is said this tribe, spread over such a vast tract of country, is a branch of the powerful race of the Algonquins. They are sometimes called O-jib-was. They do not exist as a consolidated nation, or strictly as a confederation of bands. The entire nation on both sides of the line is divided into a great number of bands, with a chief at the head of each, which not uncommonly go by his name, such as “Old Martin’s band,” “Hole in the Day’s band,” &c.

The chief’s son, especially if he exhibits the right qualities, is expected to succeed his father at the head of the band; but very frequently the honor is reached by usurpation. The whole nation, which widely differ in circumstances, according to the part of the country they inhabit, nevertheless all speak the Chippewa language, and have extensive connexion by marriage, &c. The bands inhabiting the southern shore of Lake Superior are by far the best of any others. Though polygamy still prevails among them, and especially among their chiefs, it is nevertheless said to be becoming less common, especially where they are much influenced by Catholic and other missions. While at La Pointe, an Indian wedding was consummated, being conducted according to the ceremonies of the Catholic church, and performed by the missionary priest of that persuasion stationed at the Pointe.

There is one trait of character possessed by the Chippewas, (if we except, perhaps, the band of “pillageurs,” who have a kind of “Bedouin Arab” reputation among their countrymen,) which, I am sorry to say, the whites do not possess in an equal degree – that is, “very great honesty.”

White men can travel among them with the most perfect safety as to life and property. I will venture to say, that a man may carry baskets filled with gold and silver, and set them down in Indian villages, or leave them lying where he likes, or go to sleep by them, with Indians encamped all around him, and not one cent will be touched. Such a thing as a house being broken open and robbed at a Chippewa Indian trading-post was never heard of – within between two and three years’ intercourse with them – in time of peace. Dr. Borup said he would not be afraid, if concealed to look on, to leave his store door open all night; and the fact alone of its being left open, might be made known to the Indians at the Pointe. He would expect to see no Indian enter the store, nor would he expect to lose anything; such was his confidence in their honesty!!

Last winter, flour at the Pointe rose to $40 per barrel. The poor Indians were nearly famished for bread, but were unable to purchase it at such a price. They knew the American Fur Company had a considerable lot in store, guarded by nothing stronger than a padlock, yet they never offered the least violence towards the company’s agents or store! Would white people have acted as honestly? The poor Indians, by nature honest, have too often known the whites by the wrongs inflicted upon them, which God can forgive, but time can never blot out! They are very superstitious, but not as basely and insanely so, but a great deal, as the Mormons, Millerites, and other moon-stricken sects among the whites. They believe in one Great and Good Spirit, or a Being who can at will inflict good or evil on mankind; and there’s an end of it. They often denominate the mysterious spirit of evil import the Manitou, making him to dwell in the wild hills, islands, grottoes, and caves of Lake Superior.

From these huge birds the Indians obtained their first knowledge of fire, which they kindled with fire-sticks. These mythical birds were the most powerful of the animal deities of the Indians of the woodlands and of the plains. When the weather was stormy they flew about high in the heavens. When they flapped their great wings, one heard the crashes of thunder, when they opened and closed their eyes flashes of lightning were seen. Some carried lakes of water on their backs, these slopped over and caused downpours of rain. Their arrows, or thunderbolts, were the eggs which they dropped in their flight. These shattered the rocks and set fire to the forests and prairies.

A Chippewa Indian hunter, who was carried away to his nest by a Thunderer, saved his life by killing one of the young birds and flying back to earth in its feathered hide.

In the Smoky Mountains, a wild and rugged region in the southwestern part of Bayfield County, was the home of Winneboujou (Nenebozho), the fabled hero of the Ojibwa Indians. This all-powerful manitou was a blacksmith, and had his forge on the flat top of the highest mountain. Here he shaped the native copper of the Lake Superior region into useful implements for his Indian children. Much of his work at his forge was done at night, and the ringing blows of his great hammer could be heard throughout the Brule Valley and Lake Superior region. The fire of his forge reddened the sky. When he was not busy at his forge he was away hunting or seeking other adventures. Many stories of the exploits of this giant manitou have been told by the Chippewa and other Wisconsin Algonquian tribes.”

~ Legends of the Hills of Wisconsin by Dorothy Moulding Brown; The Wisconsin Archaeologist, Volume 18, Number 1, 1937, pages 20-21.

At times, it is said, a peculiar noise issues from the Porcupine mountains, and from the high hills on the main land, both east and west of La Pointe, some distance off. It is said to resemble the distant discharge of ordnance, or thunder. At one time, they said it was so loud and frequent, that they mistook it for signal guns fired from the brig Astor, which they thought might be in distress, and actually sent out a boat in search of her.

“Ojibwe shoulder pouch depicting two thunderbirds in quillwork, Peabody Museum, Harvard University.”

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

These sounds the Indians believe to be the voice of the spirit “Manitou,” who guards the deposites of mineral wealth embowelled beneath the hills, and to whom any attempt made to dig them up, and carry them off, would be highly offensive, and followed by some kind of punishment. I have never yet heard of an Indian’s leading a white man to a locality of copper, or telling where he has found a piece when picked up!

Some have supposed that the noise in question arises from volcanic action; but, as no vibration is felt in the earth, and no other proof exists of such being the case, we are led to believe that the noise is produced by the lashing of the waves of the lake after a storm, as they are driven forward into the grottoes, caves, &c. of the tall sandstone cliffs, formed at their bases by the disintegrating effects of water and ice. Some distance east of La Pointe, about the Little Girl’s Point and Montreal river, as well as west of the same place, some fifteen or twenty miles, high red sandstone cliffs occur. At their bases, near the water’s edge, a great many curiously-shaped caves and grottoes appeared. In places, the sandstone had been so cut away, that only pillars remained standing at some ten or fifteen feet in the lake, from the top of which a high rude arch would extend to the main shore, and beneath which boats could easily pass. This was particularly the case near where the islands are parted with going west up the southern shore of the lake. Some caves, with small openings for mouths, run for a long distance back beneath the hills, expanding, likely, into large halls with high vaulted roofs, &c. After a storm, a heavy sea continues to roll into these grottoes and caverns, the waves lashing themselves against their sides and roofs – thus producing sounds resembling those heard at La Pointe, &c.

As the weather is generally calm after a storm, before the sea goes down, it is likely at such times these sounds are heard.

We had occasion to pass these places when a considerable sea would be on, close to the cliffs, and could hear the hollow heavy sounds of the waves as they broke into the caverns within the cliffs and hills. Every day, while we remained, parties of Indians continued to arrive, to be present at the payment.

We finally became prepared to leave for the Mississippi, having bought two bark canoes, and hired four new voyageurs – two for each canoe – one Indian, one half-breed, and two descendants of Canadian French; and, with a stock of provisions, we were ready to be off. From this place, I sent back three voyageurs to the Sault Ste. Marie, all that I hired to come as far as La Pointe. So, after paying our respects to Mr. Hays, our worthy Indian agent, and to Dr. Borup, (to both of whom I had borne letters of introduction,) and having many “bon voyages” heaped upon us by our friends and the friends of the voyageurs, we bade adieu to La Pointe.

You will not hear from me again till I reach the Falls of St. Croix.

I am yours, very truly, &c.

MORGAN.

To be continued in Saint Croix Falls…

Wisconsin Territory Delegation: The Copper Region

April 17, 2016

By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from Copper Harbor.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 21, 1845.

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE.

—

[From our Regular Correspondent.]

THE COPPER REGION.

La Pointe, Lake Superior

July 28, 1845.

Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

In my last brief letter from this place, I had not time to notice many things which I desired to describe. I have now examined the whole coast of the southern shore of Lake Superior, extending from the Sault Ste. Marie to La Pointe, including a visit to the Anse, and the doubling of Keweena point. During the trip, as stated previously, we had camped out twenty-one nights. I examined the mines worked by the Pittsburg company at Copper harbor, and those worked by the Boston company at Eagle river, as well as picked up all the information I could about other portions of the mineral district, both off and on shore. The object I had in view when visiting it, was to find out, as near as I could, the naked facts in relation to it. The distance of the lake-shore traversed by my part to La Pointe was about five hundred miles – consuming near four weeks’ time to traverse it. I have still before me a journey of three or four hundred miles before I reach the Mississippi river, by the way of the Brulé and St. Croix rivers. I know the public mind has been recently much excited in relation to the mineral region of country of Lake Superior, and that a great many stories are in circulation about it. I know, also, that what is said and published about it, will be read with more or less interest, especially by parties who have embarked in any of the speculations which have been got up about it. It is due to truth and candor, however, for me to declare it as my opinion, that the whole country has been overrated. That copper is found scattered over the country equal in extent to the trap-rock hills and conglomerate ledges, either in its native state, or in the form of a black oxide, as a green silicate, and, perhaps, in some other forms, cannot be denied;- but the difficulty, so far, seems to be that the copper ores are too much diffused, and that no veins such as geologist would term permanent have yet positively been discovered.

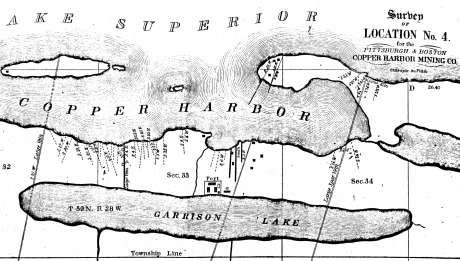

Detail of a Survey of Location No. 4 for the Pittsburgh & Boston Copper Harbor Mining Co. Image digitized by the Detroit Public Library Burton Historical Collection for The Cliff Mine Archeology Project Blog.

The richest copper ore yet found is that raised from a vein of black oxide, at Copper harbor, worked by the Pittsburg company, which yields about seventy per cent. of pure copper. But this conglomerate cementation of trap-rock, flint, pebbles, &c., and sand, brought together in a fused black mass, (as is supposed, by the overflowings of the trap, of which the hills are composed near this place,) is exceedingly hard and difficult to blast. An opinion seems to prevail among many respectable geologist, that metallic veins found in conglomerate are never thought to be very permanent. Doctor Pettit, however, informed me that he had traced the vein for near a mile through the conglomerate, and into the hill of trap, across a small lake in the rear of Fort Wilkins. The direction of the vein is from northwest to southeast through the conglomerate, while the course of the lake-shore and hills at this place varies little from north and south. Should the doctor succeed in opening a permanent vein in the hill of trap opposite, of which he is sanguine, it is probable this mine will turn out to be exceedingly valuable. As to these matters, however, time alone, with further explorations, must determine. The doctor assured me that he was at present paying his way, in merely sinking shafts over the vein preparatory to mining operations; which he considered a circumstance favorable to the mine, as this is not of common occurrence.

The mines at Copper harbor and Eagle river are the only two as yet sufficiently broached to enable one to form any tolerably accurate opinion as to their value or prospects.

~ Encyclopedia of the Earth

Other companies are about commencing operations, or talk of doing so – such as a New York, or rather Albany company, calling themselves “The New York and Lake Superior Mining Company,” under the direction of Mr. Larned, of Albany, in whose service Dr. Euhts has been employed as geologist. They have made locations at various points – at Dead river, Agate harbor, and at Montreal river. I believe they have commenced mining to some extent at Agate harbor.

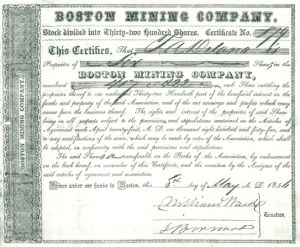

One or two other Boston companies, besides that operating at Eagle river, have been formed with the design of operating at other points. Mr. Bernard, formerly of St. Louis, is at the head of one of them. Besides these, there is a kind of Detroit company, organized, it is said, for operating on the Ontonagon river. It has its head, I believe, in Detroit, and its tail almost everywhere. I have not heard of their success in digging, thus far; though they say they have found some valuable mines. Time must determine that. I wish it may be so.

Boston Mining Company stock issued by Joab Bernard in 1846.

~ Copper Country Reflections

From Copper harbor, I paid a visit to Eagle river – a small stream inaccessible to any craft larger than a moderate-sized Mackinac boat. There is only the open lake for a roadstead off its mouth, and no harbor nearer than Eagle harbor, some few miles to the east of it. In passing west from Copper harbor along the northern shore of Keweena point, the coast, almost from the extremity of Keweena point, to near Eagle river, is an iron-bound coast, presenting huge, longitudinal, black, irregular-shaped masses of trap-conglomerate, often rising up ten or fifteen feet high above water, at some distance from the main shore, leaving small sounds behind them, with bays, to which there are entrances through broken continuities of the advanced breakwater-like ledges. Copper harbor is thus formed by Porter’s island, on which the agency has been so injudiciously placed, and which is nothing but a conglomerate island of this character; with its sides next the lake raised by Nature, so as to afford a barrier against the waves that beat against it from without. The surface of the island over the conglomerate is made up of a mass of pebbles and fragmentary rock, mixed with a small portion of earth, wholly or quite incapable of cultivation. Fort Wilkins is located about two miles from the agency, on the main land, between which and the fort communication in winter is difficult, if not impossible. Of the inexcusable blunder made in putting this garrison on its present badly-selected site, I shall have occasion to speak hereafter.

“Grand Sable Dunes”

~ National Park Service

In travelling up the coast from Sault Ste. Marie, the first 50 or 100 miles, the shore of Lake Superior exhibits, for much of the distance, a white sandy beach, with a growth of pines, silver fir, birch, &c., in the rear. This beach is strewed in places with much whitened and abraded drift-wood, thrown high on the banks by heavy waves in storms, and the action of ice in winter. This drift-wood is met with, at places, from one end of the lake to the other, which we found very convenient for firewood at our encampments. The sand on the southern shore terminates, in a measure, at Grand Sables, which are immense naked pure sand-hills, rising in an almost perpendicular form next to the lake, of from 200 to 300 feet high. Passing this section, we come to white sand-stone in the Pictured Rocks. Leaving these, we make the red sand-stone promontories and shore, at various points from this section, to the extreme end of the lake. It never afterwards wholly disappears. Between promontories of red stone are headlands, &c., standing out often in long, high irregular cliffs, with traverses of from 6, 7, to 8 miles from one to the other, while a kind of rounded bay stretches away inland, having often a sandy beach at its base, with pines growing in the forest in the rear. Into these bays, small rivers, nearly or quite shut in summer with sand, enter the lake.

The first trap-rock we met with, was near Dead river, and at some few points west of it. We then saw no more of it immediately on the coast, till we made the southern shore of Keweena point. All around the coast by the Anse, around Keweena bay, we found nothing but alternations of sand beaches and sand-stone cliffs and points. The inland, distant, and high hills about Huron river, no doubt, are mainly composed of trap-rock.

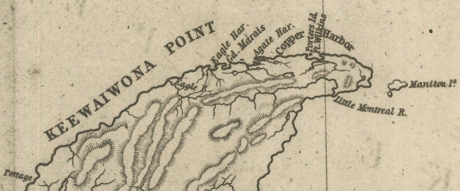

Detail from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Going west from Eagle river, we soon after lost both conglomerate and trap-rock, and found, in their stead, our old companions – red sand-stone shores, cliffs, and promontories, alternating with sandy or gravelly beaches.

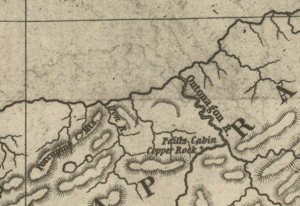

Detail of the Ontonagon River, “Paul’s Cabin,” the Ontonagon Boulder, and the Porcupine Mountains from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The trap-rock east and west of the Portage river rises with, and follows, the range of high hills running, at most points irregularly, from northeast to southwest, parallel with the lake shore. It is said to appear in the Porcupine mountain, which runs parallel with Iron river, and at right angles to the lake shore. This mountain is so named by the Indians, who conceived its principal ridge bore a likeness to a porcupine; but, to my fancy, it bears a better resemblance to a huge hog, with its snout stuck down at the lake-shore, and its back and tail running into the interior. This river and mountain are found about twenty miles west of the Ontonagon river, which is said to be the largest stream that empties into the lake. The site for a farm, or the location of an agency, at its mouth, is very beautiful, and admirably suited for either purpose. The soil is good; the river safe for the entrance and secure anchorage of schooners, and navigable to large barges and keel-boats for twelve miles above its mouth. The trap range, believed to be as rich in copper ores as any part of Lake Superior, crosses this river near its forks, about fifteen miles above its mouth. The government have organized a mineral agency at its mouth, and appointed Major Campbell as agent to reside at it; than whom, a better selection could not have been made.

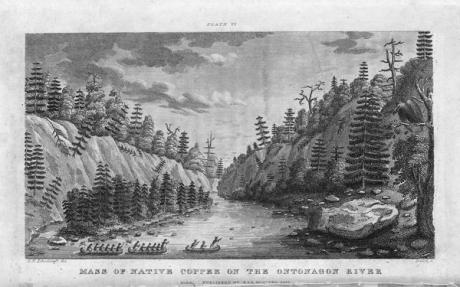

“Engraving depicting the Schoolcraft expedition crossing the Ontonagon River to investigate a copper boulder.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Detail of the Montreal River, La Pointe, and Chequamegon bay from from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The nearest approach the trap-rock hills make to the lake-shore, beyond the Porcupine mountain, is on the Montreal river, a short distance above the falls. Beyond Montreal river, to La Pointe, we found red-clay cliffs, based on red sand-stone, to occur. Indeed, this combination frequently occurred at various sections of the coast – beginning, first, some miles west of the Portage.

From Copper harbor to Agate harbor is called 7 miles; to Eagle river, 20 miles; to the Portage, 40 miles; to the Ontonagon, 80 miles; to La Pointe, from Copper harbor, 170 miles. From the latter place to the river Brulé is about 70 miles; up which we expect to ascend for 75 miles, make a portage of three miles to the St. Croix river, and descend that for 300 miles to the Mississippi river.

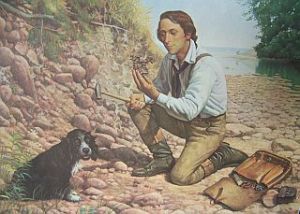

Painting of Professor Douglass Houghton by Robert Thom. Houghton first explored the south shore of Lake Superior in 1840, and died on Lake Superior during a storm on October 13, 1845. Chequamegon Bay’s City of Houghton was named in his honor, and is now known as Houghton Falls State Natural Area.

Going back to Eagle river, at the time of our visit, we found at the mine Mr. Henshaw, Mr. Williams, and Dr. Jackson of Boston, and Dr. Houghton of Michigan, who was passing from Copper harbor to meet his men at his principal camp on Portage river, which he expected to reach that night. The doctor is making a rapid and thorough survey of the country. This work he is conducting in a duplicate manner, under the authority of the United States government. It is both a topographical and geological survey. All his surveyors carry sacks, into which they put pieces of rock broken from every prominent mass they see, and carry into camp at night, for the doctor’s examination, from which he selects specimens for future use. The doctor, from possessing extraordinary strength of constitution, can undergo exposure and fatigue sufficient to break down some of the hardiest men that can be found in the West. He wears his beard as long as a Dunkard’s; has a coat and patched pants made of bed ticking; wears a flat-browned ash-colored, wool hat, and a piece of small hemp cord off a guard chain; and, with two half-breed Indians and a small dog as companions, embarks in a small bark, moving and travelling along the lake shore with great celerity.

Probably no company on Lake Superior has had a longer and harder struggle against adversity than the Phœnix. The original concern, the Lake Superior Copper Company, was among the first which operated at Lake Superior after the relinquishment of the Indian rights to this country in 1843. The trustees of this early organization were David Henshaw and Samuel Williams of Boston, and D. G. Jones and Col. Chas. H. Gratiot, of Detroit; Dr. Charles T. Jackson examined the veins on the property, and work was begun in the latter part of the year 1844. The company met with bad luck from the start, and, the capital stock having become exhausted, it has been reorganized several times in the course of its history.”

~ The Lake Superior Copper Properties: A Guide to Investors and Speculators in in Lake Superior Copper Shares Giving History, Products, Dividend Record and Future Outlook for Each Property, by Henry M. Pinkham, 1888, page 9.

We all sat down to dinner together, by invitation of Mr. Williams, and ate heartily of good, wholesome fare.

After dinner we paid a visit to the shafts at the mine, sunk to a considerable depth in two or three places. Only a few men were at work on one of the shafts; the others seemed to be employed on the saw-mill erecting near the mouth of the river. Others were at work in cutting timbers, &c.

They had also a crushing-mill in a state of forwardness, near the mine.

It is what has been said, and put forth about the value of this mineral deposite, which has done more to incite and feed the copper fever than all other things put together.

Professor Charles Thomas Jackson.

~ Contributions to the History of American Geology, plate 11, opposite page 290.

Dr. Jackson was up here last year, and has this year come up again in the service of the company. Without going very far to explore the country elsewhere, he has certainly been heard to make some very extravagant declarations about this mine,- such as that he “considered it worth a million of dollars;” that some of the ore raised was “worth $2,000 or $3,000 per ton!” So extravagant have been the talk and calculations about this mine, that shares (in its brief lease) have been sold, it is said, for $500 per share! – or more, perhaps!! No doubt, many members of the company are sincere, and actually believe the mine to be immensely valuable. Mr. Williams and General Wilson, both stockholders, strike a trade between themselves. One agrees or offers to give the other $36,000 for his interest, which the other consents to take. This transaction, under some mysterious arrangement, appears in the newspapers, and is widely copied.

Without wishing to give an opinion as to the value and permanency of this mine, (in which many persons have become, probably, seriously involved,) even were I as well qualified to do so as some others, I can only state what are the views of some scientific and practical gentlemen with whom I fell in while in the country, who were from the eastern cities, and carefully examined the famous Eagle river silver and copper mine. I do not allude to Dr. Houghton; for he declines to give an opinion to any one about any part of the country.

“The remarkable copper-silver ‘halfbreed’ specimen shown above comes from northern Michigan’s Portage Lake Volcanic Series, an extremely thick, Precambrian-aged, flood-basalt deposit that fills up an ancient continental rift valley.”

~ Shared with a Creative Commons license from James St. John

They say this mine is a deposite mine of native silver and copper in pure trap-rock, and no vein at all; that it presents the appearance of these metals being mingled broadcast in the mass of trap-rock; that, in sinking a shaft, the constant danger is, that while a few successive blasts may bring up very rich specimens of the metals, the succeeding blast or stroke of the pick-axe may bring up nothing but plain rock. In other words, that, in all such deposite mines, including deposition of diffused particles of native meteals, there is no certainly their PERMANENT character. How far this mine will extend through the trap, or how long it will hold out, is a matter of uncertainty. Indeed, time alone will show.

It is said metallic veins are most apt to be found in a permanent form where the mountain limestone and trap come in contact.

I have no prejudice against the country, or any parties whatever. I sincerely wish the whole mineral district, and the Eagle mine in particular, were as rich as it has been represented to be. I should like to see such vast mineral wealth as it has been held forth to be, added to the resources of the country.

Unless Dr. Pettit has succeeded in fixing the vein of black oxide in the side of the mountain or hill, it is believed by good judges that no permanent vein has yet been discovered, as far as has come to their knowledge, in the country!! That much of the conglomerate and trap-rock sections of the country, however, presents strong indications and widely diffused appearances of silver and copper ores, cannot be denied; and from the great number of active persons engaged in making explorations, it is possible, if not probable, that valuable veins may be discovered in some portions of the country.

To find such out, however, if they exist, unless by accident, must be the work of time and labor – perhaps of years – as the interior is exceedingly difficult, or rather almost impossible, to examine, on account of the impenetrable nature of the woods.

During our long and tedious journey, we were favored with a good deal of fine weather. We however experienced, first and last, five or six thunderstorms, and some tolerably severe gales.

Coasting for such a great length, and camping out at night, was not without some trials and odd incidents – mixed with some considerable hardships.

On the night before we reached La Pointe, we camped on a rough pebbly beach, some six or eight miles east of Montreal river, under the lea of some high clay cliffs. We kindled our fire on what appeared to be a clear bed of rather large and rounded stones, at the mouth of a gorge in the cliffs.

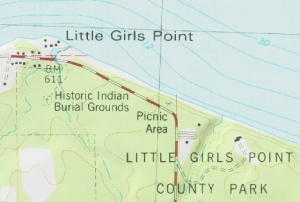

Topographic map of the gorge in the cliffs at Little Girl’s Point County Park.

~ United States Geological Survey

Next morning early, the fire was rekindled at the same spot, although some rain had falled in the night it being still cloudy, and heavy thunder rolling, indicating an approaching storm. I had placed some potatoes in the fire to roast, while some of the voyageurs were getting other things ready for breakfast; but before we could get anything done, the rain down upon us in torrents. We soon discovered that we had kindled our fire in the bed of a wet weather creek. The water rapidly rose, put out the fire, and washed away my potatoes.

We had then to kindle a new fire at a higher place, which was commenced at the end of a small crooked log. One of the voyageurs had set the frying-pan on the fire with an Indian pone or cake an inch thick, and large enough to cover the bottom it. The under side had begun to bake; another hand had mixed the coffee, and set the coffee-pot on to boil; while a third had been nursing a pot boiling with pork and potatoes, which, as we were detained by rain, the voyageurs thought best to prepare for two meals. One of the part, unfortunately, not observing the connexion between the crooked pole, and the fire at the end of it, jumped with his whole weight on it, which caused it suddenly to turn. In its movement, it turned the frying-pan completely over on the sand, with its contents, which became plastered to the dirt. The coffee-pot was also trounced bottom upwards, and emptied its contents on the sand. The pot of potatoes and pork, not to be outdone, turned over directly into the fire, and very nearly extinguished it. We had, in a measure, to commence operations anew, it being nearly 10 o’clock before we could get breakfast. When near the Madelaine islands, (on the largest of which La Pointe is situated,) the following night, our pilot, amidst the darkness of the evening, got bewildered for a time, when we thought best to land and camp; which, luckily for us, was at a spot within sight of La Pointe. Many trifling incidents of this character befell us in our long journey.

Lake Bands:

“Ki ji ua be she shi, 1st [Chief].

Ke kon o tum, 2nd [Chief].”

Pelican Lakes:

“Kee-che-waub-ish-ash, 1st chief, his x mark.

Nig-gig, 2d chief, his x mark.“

Lac Courte Oreilles Band:

At the mouth of the Montreal river, we fell in with a party of seventeen Indians, composed of old Martin and his band, on their way to La Pointe, to be present at the payment expected to take place about the 15th of August.

They had their faces gaudily painted with red and blue stripes, with the exception of one or two, who had theirs painted quite black, and were said to be in mourning on account of deceased friends. They had come from Pelican lake (or, as the French named it, Lac du Flambeau,) being near the headwaters of the Wisconsin river, and one hundred and fifty miles distant. They had with them their wives; children, dogs, and all, walked the whole way. They told our pilot, Jean Baptiste, himself three parts Indian, that they were hungry, and had no canoe with which to get on to La Pointe. We gave them some corn meal, and received some fish from them for a second supply. For the Indians, if they have anything they think you want, never offer generally to sell it to you, till they have first begged all they can; then they will produce their fish, &c., offering to trade; for which they expect an additional supply of the article you have been giving them. Baptiste distributed among them a few twists of tobacco, which seemed very acceptable. Old Martin presented Baptiste with a fine specimen of native copper which he had picked up somewhere on his way – probably on the headwaters of the Montreal river. He desired us to take one of his men with us to La Pointe, in order that he might carry a canoe back to the party, to enable them to reach La Pointe the next day, which we accordingly complied with. We dropped him, however, at his own request, on the point of land some miles south of La Pointe, where he said he had an Indian acquaintance, who hailed him from shore.

Having reached La Pointe, we were prepared to rest a few days, before commencing our voyage to the Mississippi river.

Of things hereabouts, and in general, I will discourse in my next.

In great haste I am,

Very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

MORGAN.

To be continued in La Pointe…

John Johnston Describes La Pointe (1807-09)

June 12, 2014

Susan Johnston, or Ozhaawashkodewekwe, the wife of John Johnston ( Chicago Newberry Library)

The name of John Johnston will be familiar to those who have read the works of his son-in-law Henry Schoolcraft. Johnston (1762-1828) was born into the Anglo-Protestant gentry of Northern Ireland and came to the Chequamegon region in 1791. After marrying Ozhaawashkodewekwe, the daughter of Waabojiig, he cemented his alliance with a prominent Ojibwe trading family. The Johnstons settled at Sault Ste. Marie, and their influence as a fur-trade power couple in the eastern part of Lake Superior parallels that of Michel and Madeline (Ikwezewe) Cadotte around La Pointe. The Johnstons played a key role in resistance to American encroachment in Lake Superior during the War of 1812 but later became centrally-connected to the United States Government efforts to establish a foothold in the northern country. A nice concise biography of John Johnston is available in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

Roderick MacKenzie (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1806, John Johnston was trading at the Soo for the North West Company when he received a printed request from Roderick MacKenzie, one of the heads of the Company. It called for information on the physical and cultural geography of the different parts of North America where the NWC traded. Johnston took it upon himself to describe the Lake Superior region and prepared An Account of Lake Superior, an 82-page manuscript.

By the end of the 19th century, the manuscript had found its way to Louis Rodrigue Masson (a grandson-in-law of MacKenzie) who edited it and published it in Les Bourgeois de la Compagnie du Nord-Ouest; recits de voyages, lettres et rapports inedits relatifs au Nord-Ouest Canadien (1889-90). The Masson archives were later donated to the McGill University Library in Montreal and are now digitized.

Much of Johnston’s account concerns the Sault and the eastern part of Lake Superior. However, he does include some information from his time at La Pointe, which is reproduced below. While it doesn’t say much about the political topics that I tend to focus on, this document is fascinating for its geographic toponyms and terminology, which is much more reflective of the 18th century than the 19th. Enjoy:

[Ojibwe names for geographic locations are taken from Gidakiiminaan: An Anishinaabe Atlas of the 1836 (Upper Michigan), 1837, and 1842 Treaty Ceded Territories (GLIFWC 2007)].

[pg. 49-56]

…The coast runs almost due West from the Kakewiching or Porcupine Mountain to the Montreal River a distance of fifteen leagues, and the beach is a shelving rock the same as the Mountain all the way with here and there a little gravelly strand. There is but one river, and that a very small one, from the Black to the Montreal River. This last takes its rise from the Wa[s]wagonnis or flambeau Lake about 80 leagues to the Southwest: it is one continued rapid from within ten leagues of its source, and a few hundred yards from the entrance has a fall of fifteen or twenty feet: – there are two high clay banks which distinguish the entrance. The lands tends to the Northwest and is a stiff clay for three leagues rent into deep gutters at short distances; it then gradually declines to a sandy beach for three leagues farther until you arrive at the Mouskissipi or bad river so called from its broad and shallow stream in which it is almost impossible to mount even an Indian Canoe.

It takes its rise from the Ottawa Lake about 125 leagues to the Westward: the Lake has its waters divided very partially as the chief part takes a southerly course and falls into the Mississipi and is called Ottawa River.

The Flambeau Lake has its waters also, the better part taking a southeasterly direction to the Mississipi and is called Ouisconsin or the medicine River. From the bad river the coast runs north four leagues to Chogowiminan or La Pointe; it is a fine strand all the way, behind which are sand hills covered with bent and sand cherry shrubs – and behind the hills there runs all the length a shallow bay which is a branch from the Bay of St Charles.

At Lapointe you are nearly opposite the Anse or Keegwagnan the distance I should conjecture to be twenty leagues in a straight line.

The Bay of St Charles runs southwest from La Pointe and is four leagues in depth and better than a league broad at the entrance. Opposite Lapointe to the Northeast is the Island of Montreal, one of the largest of those called the twelve Apostles. On the main land the Indians had once a Village amounting to 200 huts but since the Traders have multiplied, they no longer assemble at Netoungan or the sand beach, but remain in small bands near their hunting grounds. When you double the Point of Netoungan the coast tends nearly west and is composed of high rocky points of Basaltes with some freestone; there is one place in particular which is an humble imitation of the Portals but not near so high: it is about a leagues from La Pointe and is a projection from the highest mountain from Porcupine bay to fond du lac, a distance of more than 45 leagues. From the Summit of the Mountain; you can count twenty six Islands extending to the North and North east, Islands which has never been visited by the boldest Indians and lying out of the way of the N.W.Co’s Vessel: have a chance of never being better known. Of the Islands opposite La pointe ten or twelve have been visited by the Indians, some of which have a rich soil covered with oak and beech, and round all of them there is deep water and fine fishing for Trout. The Trout in this part of the Lake are equal to those of Mackinac in size & richness – I myself saw one taken off the Northeast end of Montreal Island that weighed fifty two Pounds. How many Islands this Archipelago actually contains will not be easily ascertained; but I take Carribou Island to be the eastern end of the chain. It lies a little to the Southward of the course of the Co’s Vessel, is about three miles round, has a flat shore and good anchorage, and is allowed to be half passage from Camanitiquia to St. Mary’s. However, no other land is seen from it by the Vessel; but that may be owing to the Islands being low and lying too much to the Southward of the course. It is to be observed this account of the number of Islands is upon Indian Authority, which though not the best, is still less apocryphal than that of the Canadians.

There are several rivers between Lapointe and Fond du Lac, the distance is allowed to be thirty leagues, and the breadth of the bay from a high Rocky point within a leagues of Netoungan to the roche deboute, or the upright rock, which is a lofty Mountain right opposite, cannot be less than twenty leagues.

The Metal River is within ten leagues of Fond du Lac; it is only remarkable from the Old Chief of Lapointe’s having once found a large piece of Silver ore in descending it. The Burnt river is three leagues to the Westward of Metal river; it issues from one of the Lakes of the little wild Oats Country about thirty leagues to the Southward, and is only navigable for small Canoes: it has several rapids and the Portages are dangerous, several of them lying along the edge of the river, and over precipices where one false step would be fatal. It empties itself into the Bay of Fond du Lac through a stiff Clay Bank which continues all along the shore until it joins the sands of Fond du Lac river.

About sixteen years ago, Wabogick, or the Whitefisher, the Chief of Lapointe, made his sugar on the skirt of a high mountain four days march from the entrance of the river to the south west, his eldest daughter then a girl of fourteen with a cousin of hers who was two or three years older, rambling one day up the eastern side of the Mountain came to a perpendicular Cliff, which exactly fronted the rising sun, and had an apparently artificial level before it, on which near the base of the Cliff they found a pieces of yellow metal as they called it, about eighteen inches long, a foot broad, and four inches thick; and perfectly Smooth: – it was so heavy that they could raise it with great difficulty: – after amusing themselves with examining it for some time, it occured to the eldest girl that it belonged to the Gitchi Manitou or the great spirit; upon which they abandoned the place with precipitation. As the Chipeways are not Idolators, it occurs to me that some of the Southern tribes must have once Migrated thus far to the North, and that the piece, either of copper or gold, is part of an alter dedicated to the sun. If my conjecture is right, the slab is most probably gold as the Mexicans have more of that Metal than they have of copper. I have often regretted the premature death of the Chief the same autumn that he told me the story, as he had promised to go and bring it to me if he recovered: and circumstances since have precluded my making any attempt to procure it.

The river of Fond du Lac is deep, wide and serpentine, but is only navigable for four or five leagues from its entrance. The Portages are many and different until you arrive at the sand Lake, where the tribe of Chipeways, called the Pillagers, reside. The furs from this country are the best assorted of any on the Continent; and the quantity would much increase were it possible to repress the mutual incursions of the Scieux and Chipeways, who caray on perpetual war. The tract of country lying between the two nations for near 150 leagues in length and from thirty to forty in breadth is only visited by stealth, and if peaceably hunted would be more productive than the richest mine of Peru…

[pg. 75-76]

…The wild Vine is not found at St Mary’s nor any where along the lake except at Lapointe, where however it is scarce. The wild Hop is very abundant at Lapointe but I do not recollect to have seen it elsewhere. There are three distinct species of Whortleberry. The blue or real whortleberry is by far the most wholesome and agreeable: the abundance of this fruit on the borders of Lake Superior is incredible; the Indians dry great quantities of them which they preserve during the winter, and which make an agreeable taste when repeatedly washed in warm water to take away the smoky taste from them. The black Whortleberry grows much higher than the blue; its seeds are very hard and astringent – the largest species the Indians call Hareberry; it grows to 2 or 3 feet high and bears a fruit as large as a cherry, but it is neither so agreeable nor so wholesome as either of the others…

Poisson Blanc (whitefish), Broche (pike) and Truite Comune (Lake Trout) from the Codex Canadensis.

Poisson Blanc (whitefish), Broche (pike) and Truite Comune (Lake Trout) from the Codex Canadensis. (Photo: Wikimedia Images)

(Photo: Wikimedia Images) This is all for now on John Johnston, but this document is a potential jumping-off point for several potential research topics. Look for an upcoming post on the meaning of “La Pointe” and “La Pointe Band.”

Sources:

Armour, David A. “JOHNSTON, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed June 12, 2014, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/johnston_john_6E.html.

Gidakiiminaan = Our Earth. Odanah, WI: Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, 2007. Print.

Masson, L. R. Les Bourgeois De La Compagnie Du Nord-Ouest: Recits De Voyages, Lettres Et Rapports Inedits Relatifs Au Nord-ouest Canadien. Québec: A. Côté, 1889. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Oneóta, or Characteristics of the Red Race of America. New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845. Print

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. The Indian in His Wigwam, Or, Characteristics of the Red Race of America from Original Notes and Manuscripts. New York: W.H. Graham, 1848. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Fun With Maps

June 28, 2013

I’m someone who loves a good historical map, so one of my favorite websites is memory.loc.gov, the digital collections of the Library of Congress. You can spend hours zooming in on neat vintage maps. This post has snippets from eleven of them, stretching from 1674 to 1843. They are full of cool old inaccuracies, but they also highlight important historical trends and eras in our history. This should not be considered an exhaustive survey of the best maps out there, nor is it representative of all the LOC maps. Really, it’s just 11 semi-random maps with my observations on what I found interesting. Click on any map to go to the Library of Congress site where you can browse more of it. Enjoy:

French 1674

Nouvelle decouverte de plusieurs nations dans la Nouvelle France en l’année 1673 et 1674 by Louis Joliet. Joliet famously traveled from the Great Lakes down the Mississippi with the Jesuit Jacques Marquette in 1673.

- Cool trees.

- Baye des Puans: The French called the Ho-Chunk Puans, “Stinky People.” That was a translation of the Ojibwe word Wiinibiigoo (Winnebago), which means “stinky water people.” Green Bay is “green” in summer because of the stinky green algae that covers it. It’s not surprising that the Ho-Chunk no longer wish to be called the Winnebago or Puans.

- 8tagami: The French used 8 in Indian words for the English sound “W.” 8tagami (Odagami) is the Ojibwe/Odawa/Potawatomi word for the Meskwaki (Fox) People.

- Nations du Nord: To the French, the country between Lake Superior and Hudson Bay was the home of “an infinity of nations,” (check out this book by that title) small bands speaking dialects of Ojibwe, Cree, and Assiniboine Sioux.

- The Keweenaw is pretty small, but Lake Superior has generally the right shape.

French 1688

Carte de l’Amerique Septentrionnale by Jean Baptiste Louis Franquelin: Franquelin created dozens of maps as the royal cartographer and hydrographer of New France.

- Lake Superior is remarkably accurate for this time period.

- Nations sous le nom d’Outouacs: “Nations under the name of Ottawas”–the French had a tendency to lump all Anishinaabe peoples in the west (Ojibwe, Ottawa, Potawatomi, etc.) under the name Outouais or Outouacs.

- River names, some are the same and some have changed. Bois Brule (Brule River) in French is “burnt wood” a translation of the Ojibwe wiisakode. I see ouatsicoto inside the name of the Brule on this map (Neouatsicoton), but I’m not 100% sure that’s wiisakode. Piouabic (biwaabik is Ojibwe word for Iron) for the Iron River is still around. Mosquesisipi (Mashkiziibi) or Swampy River is the Ojibwe for the Bad River.

- Madeline Island is Ile. St. Michel, showing that it was known at “Michael’s Island” a century before Michel Cadotte established his fur post.

- Ance Chagoüamigon: Point Chequamegon

French 1703

Carte de la riviere Longue : et de quelques autres, qui se dechargent dans le grand fleuve de Missisipi [sic] … by Louis Armand the Baron de Lahontan. Baron Lahontan was a military officer of New France who explored the Mississippi and Missouri River valleys.

- Lake Superior looks quite strange.

- “Sauteurs” and Jesuits at Sault Ste. Marie: the French called the Anishinaabe people at Sault Ste. Marie (mostly Crane Clan) the Sauteurs or Saulteaux, meaning “people of the falls.” This term came to encompass most of the people who would now be called Ojibwe.

- Fort Dulhut: This is not Duluth, Minnesota, but rather Kaministiquia (modern-day Thunder Bay). It is named for the same person–Daniel Greysolon, the Sieur du Lhut (Duluth).

- Riviere Du Tombeau: “The River of Tombs” at the west end of the Lake is the St. Croix River, which does not actually flow into Lake Superior but connects it to the Mississippi over a short portage from the Brule River.

- Chagouamigon (Chequamegon) is placed much too far to the east.

- The Fox River is gigantic flowing due east rather than north into Green Bay. We see the “Savage friends of the French:” Outagamis (Meskwaki/Fox), Malumins (Menominee), and Kikapous (Kickapoo).

French 1742

Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques N. Bellin 1742. Bellin was a famous European mapmaker who compiled various maps together. The top map is a detail from the Carte de Lacs. The bottom one is from a slightly later map.

- Of the maps shown so far, this has the best depiction of Chequamegon, but Lake Superior as a whole is much less accurate than on Franquelin’s map from fifty years earlier.

- The mysterious “Isle Phillipeaux,” a second large island southeast of Isle Royale shows prominently on this map. Isle Phillipeaux is one of those cartographic oddities that pops up on maps for decades after it first appears even though it doesn’t exist.

- Cool river names not shown on Franquelin’s map: Atokas (Cranberry River) and Fond Plat “Flat-bottom” (Sand River)

- The region west of today’s Herbster, Wisconsin is lablled “Papoishika.” I did an extensive post about an area called Ka-puk-wi-e-kah in that same location.

- Ici etoit une Bourgade Considerable: “Here there was a large village.” This in reference to when Chequamegon was a center for the Huron, Ottawa (Odawa) and other refugee nations of the Iroquois Wars in the mid-1600s.

- “La Petite Fille”: Little Girl’s Point.

- Chequamegon Bay is Baye St. Charles

- Catagane: Kakagon, Maxisipi: Mashkizibi

- The islands are “The 12 Apostles.”

British 1778

A new map of North America, from the latest discoveries 1778. Engrav’d for Carver’s Travels. In 1766 Jonathan Carver became one of the first Englishmen to pass through this region. His narrative is a key source for the time period directly following the conquest of New France, when the British claimed dominion over the Great Lakes.

- Lake Superior still has two giant islands in the middle of it.

- The Chipeway (Ojibwe), Ottaway (Odawa), and Ottagamie (Meskwaki/Fox) seem to have neatly delineated nations. The reality was much more complex. By 1778, the Ojibwe had moved inland from Lake Superior and were firmly in control of areas like Lac du Flambeau and Lac Courte Oreilles, which had formerly been contested by the Meskwaki.

Dutch 1805

Charte von den Vereinigten Staaten von Nord-America nebst Louisiana by F.L. Gussefeld: Published in Europe.

- The Dutch never had a claim to this region. In fact, this is a copy of a German map. However, it was too cool-looking to pass up.

- Over 100 years after Franquelin’s fairly-accurate outline of Lake Superior, much of Europe was still looking at this junk.

- “Ober See” and Tschippeweer” are funny to me.

- Isle Phillipeau is hanging on strong into the nineteenth century.

American 1805

A map of Lewis and Clark’s track across the western portion of North America, from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean : by order of the executive of the United States in 1804, 5 & 6 / copied by Samuel Lewis from the original drawing of Wm. Clark. This map was compiled from the manuscript maps of Lewis and Clark.

- The Chequamegon Region supposedly became American territory with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. The reality on the ground, however, was that the Ojibwe held sovereignty over their lands. The fur companies operating in the area were British-Canadian, and they employed mostly French-Ojibwe mix-bloods in the industry.

- This is a lovely-looking map, but it shows just how little the Americans knew about this area. Ironically, British Canada is very well-detailed, as is the route of Lewis and Clark and parts of the Mississippi that had just been visited by the American, Lt. Zebulon Pike.

- “Point Cheganega” is a crude islandless depiction of what we would call Point Detour.

- The Montreal River is huge and sprawling, but the Brule, Bad, and Ontonagon Rivers do not exist.

- To this map’s credit, there is only one Isle Royale. Goodbye Isle Phillipeaux. It was fun knowing you.

- It is striking how the American’s had access to decent maps of the British-Canadian areas of Lake Superior, but not of what was supposedly their own territory.

English 1811

A new map of North America from the latest authorities By John Cary of London. This map was published just before the outbreak of war between Britain and the United States.

- These maps are starting to look modern. The rivers are getting more accurate and the shape of Lake Superior is much better–though the shoreline isn’t done very well.

- Burntwood=Brule, Donagan=Ontonagon

- The big red line across Lake Superior is the US-British border. This map shows Isle Royale in Canada. The line stops at Rainy Lake because the fate of the parts of Minnesota and North Dakota in the Hudson Bay Watershed (claimed by the Hudson Bay Company) was not yet settled.

- “About this place a settlement of the North West Company”: This is Michel Cadotte’s trading post at La Pointe on Madeline Island. Cadotte was the son of a French trader and an Anishinaabe woman, and he traded for the British North West Company.

- It is striking that a London-made map created for mass consumption would so blatantly show a British company operating on the American side of the line. This was one of the issues that sparked the War of 1812. The Indian nations of the Great Lakes weren’t party to the Treaty of Paris and certainly did not recognize American sovereignty over their lands. They maintained the right to have British traders. America didn’t see it that way.

American 1820

Map of the United States of America : with the contiguous British and Spanish possessions / compiled from the latest & best authorities by John Melish

- Lake Superior shape and shoreline are looking much better.

- Bad River is “Red River.” I’ve never seen that as an alternate name for the Bad. I’m wondering if it’s a typo from a misreading of “bad”

- Copper mines are shown on the Donagon (Ontonagon) River. Serious copper mining in that region was still over a decade away. This probably references the ancient Indian copper-mining culture of Lake Superior or the handful of exploratory attempts by the French and British.

- The Brule-St. Croix portage is marked “Carrying Place.”

- No mention of Chequamegon or any of the Apostle Islands–just Sand Point.

- Isle Phillipeaux lives! All the way into the 1820s! But, it’s starting to settle into being what it probably was all along–the end of the Keweenaw mistakenly viewed from Isle Royale as an island rather than a peninsula.

American 1839

From the Map of Michigan and part of Wisconsin Territory, part of the American Atlas produced under the direction of U.S. Postmaster General David H. Burr.

- Three years before the Ojibwe cede the Lake Superior shoreline of Wisconsin, we see how rapidly American knowledge of this area is growing in the 1830s.

- The shoreline is looking much better, but the islands are odd. Stockton (Presque Isle) and Outer Island have merged into a huge dinosaur foot while Madeline Island has lost its north end.

- Weird river names: Flagg River is Spencer’s, Siskiwit River is Heron, and Sand River is Santeaux. Fish Creek is the gigantic Talking Fish River, and “Raspberry” appears to be labeling the Sioux River rather than the farther-north Raspberry River.

- Points: Bark Point is Birch Bark, Detour is Detour, and Houghton is Cold Point. Chequamegon Point is Chegoimegon Point, but the bay is just “The Bay.”

- The “Factory” at Madeline Island and the other on Long Island refers to a fur post. This usage is common in Canada: Moose Factory, York Factory, etc. At this time period, the only Factory would have been on Madeline.

- The Indian Village is shown at Odanah six years before Protestant missionaries supposedly founded Odanah. A commonly-heard misconception is that the La Pointe Band split into Island and Bad River factions in the 1840s. In reality, the Ojibwe didn’t have fixed villages. They moved throughout the region based on the seasonal availability of food. The traders were on the island, and it provided access to good fishing, but the gardens, wild rice, and other food sources were more abundant near the Kakagon sloughs. Yes, those Ojibwe married into the trading families clustered more often on the Island, and those who got sick of the missionaries stayed more often at Bad River (at least until the missionaries followed them there), but there was no hard and fast split of the La Pointe Band until long after Bad River and Red Cliff were established as separate reservations.

American 1843

Hydrographical basin of the upper Mississippi River from astronomical and barometrical observations, surveys, and information by Joseph Nicollet. Nicollet is considered the first to accurately map the basin of the Upper Mississippi. His Chequamegon Region is pretty good also.

- You may notice this map decorating the sides of the Chequamegon History website.

- This post mentions this map and the usage of Apakwa for the Bark River.

- As with the 1839 map, this map’s Raspberry River appears to be the Sioux rather than the Miskomin (Raspberry) River.

- Madeline Island has a little tail, but the Islands have their familiar shapes.

- Shagwamigon, another variant spelling

- Mashkeg River: in Ojibwe the Bad River is Mashkizibi (Swamp River). Mashkiig is the Ojibwe word for swamp. In the boreal forests of North America, this word had migrated into English as muskeg. It’s interesting how Nicollet labels the forks, with the White River fork being the most prominent.

That’s all for now folks. Thanks for covering 200 years of history with me through these maps. If you have any questions, or have any cool observations of your own, go ahead and post them in the comments.

Note: This is the second of four posts about Lt. James Allen, his ten American soldiers and their experiences on the St. Croix and Brule rivers. They were sent from Sault Ste. Marie to accompany the 1832 expedition of Indian Agent Henry Schoolcraft to the source of the Mississippi River. Each of the posts will give some general information about the expedition and some pages from Allen’s journal.