By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from Copper Harbor Redux.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 29, 1845.

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE.

—

[From our regular correspondent.]

ST. LOUIS, Mo. Aug. 19, 1845.

One of the most interesting sections of the North American continent is the basin of the Upper Mississippi, being, as it is, greatly diversified by soil, climate, natural productions, &c. It embraces mineral lands of great extent and value, with immense tracts of good timber, and large and fertile bodies of farming land. This basin is separated by elevated land o the northeast, which divides the headwaters of rivers emptying into the Mississippi from those that flow into the lakes Superior and Michigan, Green Bay, &c. To the north and northwest, it is separated near the head of the Mississippi, by high ground, from the watercourses which flow towards Hudson’s bay. To the west, this extensive basin is divided from the waters of the Missouri by immense tracts of elevated plateau, or prairie land, called by the early French voyageurs “Coteau des Prairies,” signifying “prairie coast,” from the resemblance the high prairies, seen at a great distance, bear to the coast of some vast sea or lake. To the south, the basin of the Upper Mississippi terminates at the junction of the Mississippi with the Des Moines river.

The portion of the valley of the Mississippi thus described, if reduced to a square form, would measure about 1,000 miles each way, with St. Anthony’s falls near the centre.

1698 detail of Saint Anthony’s Falls and Lake Superior from Amerique Septentrionalis Carte d’un tres grand Pays entre le Nouveau Mexique et la Mer Glaciace Dediee a Guilliaume IIIe. Roy de La Grand Bretagne Par le R. P. Louis de Hennepin Mission: Recol: et Not: Apost: Chez c. Specht a Utreght 1698.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

For a long time, this portion of the country remained unexplored, except by scattered parties of Canadian fur-traders, &c. Its physical and topographical geography, with some notions of its geology, have, as it were, but recently attracted attention.

Douglas Volk painting of Father Hennepin at Saint Anthony Falls.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

Father Antoine “Louis” Hennepin

~ Wikipedia.org

Father Hennepin was no doubt the first white man who visited St. Anthony’s falls. In reaching them, however, he passed the mouth of St. Peter’s river, a short distance below, without noticing it, or being aware of its existence. This was caused by the situation of an island found in the Mississippi, directly in front of the mouth of St. Peter’s, which, in a measure, conceals it from view.

After passing the falls, Father Hennepin continued to ascend the Mississippi to the St. Francis river, but went no higher.

Portrait of Jonathan Carver from his book, Travels through the interior parts of North America in the years 1766, 1767 and 1768.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

In the year 1766, three years after the fall of Canada, Captain Johnathan Carver, who had taken an active part as an officer in the English service, and was at the surrender of Fort William Henry, where (he says) 1,500 English troops were massacred by the Indians, (he himself narrowly escaping with his life,) prepared for a tour among the Indian tribes inhabiting the shores of the upper lakes and the upper valley of the Mississippi. He left Boston in June of the year stated, and, proceeding by way of Albany and Niagara, reached Mackinac, where he fitted out for the prosecution of his journey to the banks of the Mississippi.

From Mackinac, he went to Green Bay; ascended the Fox river to the country of the Winnebago Indians; from thence, crossing some portages, and passing through Lake Winnebago, he descended the Wisconsin river to the Mississippi river; crossing which, he came to a halt at Prairie du Chien, in the country of the Sioux Indians. At the early day, this was an important trading-post between French traders and the Indians. Carver says: “It contains about three hundred families; the houses are well built, after the Indian manner, and well situated, on a very rich soil, from which they raise every necessary of life in great abundance. This town is the great mart whence all the adjacent tribes – even those who inhabit the most remote branches of the Mississippi – annually assemble about the latter end of May, bringing with them their furs to dispose of to the traders.” Carver also noticed that the people living there had some good horses.

Detail of Prairie du Chien from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766.

~ Boston Public Library

The fur-trade, which at one time centred here, and gave it much consequence, has been removed to St. Peter’s river. Indeed, this trade, which formerly gave employment to so many agents, traders, trappers, &c., conferring wealth upon those prosecuting it, is rapidly declining on this continent; in producing which, several causes conspire. The first is, the animals caught for their furs have greatly diminished; and the second is, that competition in the trade has become more extensive and formidable, increasing as the white settlements continue to be pushed out to the West.

John Jacob Astor established the American Fur Company.

~ Wikipedia.com

At Prairie du Chien is still seen the large stone warehouse erected by John Jacob Astor, at a time when he ruled the trade, and realized immense profits by the business. The United States have a snug garrison at this place, which imparts more or less animation to the scene. It stands on an extensive and rather low plain, with high hills in the rear, running parallel with the Mississippi.

The house in which Carver lodged, when he visited this place, is still pointed out. There are some men living at this post, whose grandfather acted as interpreter to Carver. The Sioux Indians, whom Carver calls in his journal “the Nadowessies,” which is the Chippewa appellation for this tribe of Indians, keep up the tradition of Carver’s visit among them. The inhabitants, descendants of the first settlers at Prairie du Chien, now living at this place, firmly believe in the truth of the gift of land made to Carver by the Sioux Indians.

From this point Carver visited St. Anthony’s falls, which he describes with great accuracy and fidelity, accompanying his description with a sketch of them.

![Detail of Saint Anthony's Falls from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766. ~ Boston Public Library](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/carver-detail-of-st-anthony-falls.jpg?w=460)

Detail of Saint Anthony’s Falls from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766.

~ Boston Public Library

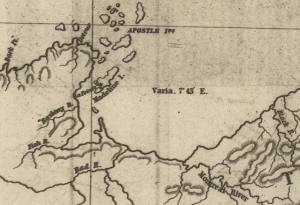

From the Mississippi river Carver crossed over to the Chippewa river; up which he ascended to its source, and then crossed a portage to the head of the Bois Brulé, which he called “Goddard’s river.” Descending this latter stream to Lake Superior, he travelled around the entire northern shore of that lake from west to east, and accurately described the general appearance of the country, including notices of the existence of the copper rock on the Ontonagon, with copper-mineral ores at points along the northeastern shore of the lake, &c.

![Detail of "Goddard's River," La Pointe, and Ontonagon from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766. ~ Boston Public Library](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/carver-detail-of-goddard-river-and-la-pointe.jpg?w=460)

Detail of “Goddard River,” La Pointe, and Ontonagon from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766.

~ Boston Public Library

He finally reached the Sault St. Marie, where he found a French Indian trader, (Monsieur Cadot,) who had built a stockade fort to protect him in his trade with the Indians.

![Detail of Sault Ste Marie from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766. ~ Boston Public Library](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/carver-detail-of-sault-ste-marie.jpg?w=460)

Detail of Sault Ste Marie from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766.

~ Boston Public Library

Descendants of this Monsieur Cadot are still living at the Sault and at La Pointe. We met one of them returning to the latter place, in the St. Croix river, as we were descending it. They, no doubt, inherit strong claims to land at the falls of the St. Mary’s river, which must ere long prove valuable to them, if properly prosecuted.

From the Sault St. Marie, Carver went to Mackinac, then garrisoned by the English, where he spent the winter. The following year he reached Boston, having been absent about two years.

From Boston he sailed for England, with a view of publishing his travels, and securing his titles to the present of land the Sioux Indians have made him, and which it is alleged the English government pledged itself to confirm, through the command of the King, in whose presence the conveyance made to Carver by the Sioux Indians was read. He not only signified his approval of the grant, but promised to fit out an expedition with vessels to sail to New Orleans, with the necessary men, &c., which Captain Carver was to head, and proceed from thence to the site of this grant, to take possession of it, by settling his people on it. The breaking out of the American revolution suspended this contemplated expedition.

Captain Carver died poor, in London, in the year 1780, leaving two sons and five daughters. I consider his description of the Indians among whom he travelled, detailing their customs, manners, and religion, the best that has ever been published.

In this opinion I am sustained by others, and especially by old Mr. Duncan Graham, whom I met on the Upper Mississippi. He has lived among the Indians ever since the year 1783. He is now between 70 and 80 years old. He told me Carver’s book contained the best account of the customs and manners of the Indians he had ever read.

His valuable work is nearly out of print, it being rather difficult to obtain a copy. It went through three editions in London. Carver dedicated it to Sir Joseph Banks, president of the Royal Society. Almost every winter on the Indians and Indian character, since Carver’s time, has made extensive plagiarisms from his book, without the least sort of acknowledgement. I could name a number of authors who have availed themselves of Carver’s writings, without acknowledgement; but as they are still living, I do not wish to wound the feelings of themselves or friends.

One of the writers alluded to, gravely puts forth, as a speculation of his own, the suggestion that the Winnebagoes, and some other tribes of Indians now residing at the north, had, in former times, resided far to the south, and fled north from the wars and persecutions of the bloodthirsty Spaniards; that the opinion was strengthened from the fact, that the Winnebagoes retained traditions of their northern flight, and of the subsequent excursions of their war parties across the plains towards New Mexico, where, meeting with Spaniards, they had in one instance surprised and defeated a large force of them, who were travelling on horseback.

Now this whole idea originated with Carver; yet Mr. ——— has, without hesitation, adopted it as a thought or discovery as his own!

Alexander Henry, The Elder.

~ Wikipedia.com

The next Englishman who visited the northwest, and explored the shores of Lake Superior, was Mr. Henry, who departed from Montreal, and reached Mackinac through Lake Huron, in a batteau laden with some goods. His travels commenced, I believe, about 1773-‘4, and ended about 1776-‘7. Mr. Henry’s explorations were conducted almost entirely with the view of opening a profitable trade with the Indians. He happened in the country while the Indians retained a strong predilection in favor of the French, and strong prejudices against the English. It being about the period of the Pontiac war, he had some hazardous adventures among the Indians, and came near losing his life. He continued, however, to prosecute his trade with the Indians, to the north and west of Lake Superior. Making voyages along the shores of this lake, he became favorably impressed with the mineral appearances of the country. Finding frequently, through is voyageurs, or by personal inspections, rich specimens of copper ore, or of the metal in its native state, he ultimately succeeded in obtaining a charter from the English government, in conjunction with some men of wealth and respectability in London, for working the mines on Lake Superior. The company, after making an ineffectual attempt to reach a copper vein, through clay, near the Ontonagon, the work was abandoned, and was not afterwards revived.

General Cass, with Colonel Allen, &c., were the next persons to pass up the southern coast of Lake Superior, and, in going to the west and northwest of the lake, they travelled through Indian tribes in search of the head of the Mississippi river. Their travels and discoveries are well known to the public, and proved highly interesting.

Mr. Schoolcraft’s travels, pretty much over the same ground, have also been given to the public; as also the expedition of General Pike on the Upper Mississippi.

Major Stephen Harriman Long published his expedition as Voyage in a Six-oared Skiff to the Falls of St. Anthony in 1817.

~ Wikipedia.org

More lately, the basin of the Upper Mississippi has received a further and more minute examination under the explorations directed by Major Long, in his two expeditions authorized by government.

Joseph Nicholas Nicollet

~ Wikipedia.org

Lastly, Mr. J. N. Nicollet, a French savan, travelling for some years through the United States with scientific objects in view, made an extensive examination of the basin of the Upper Mississippi.

He ascended the Missouri river to the Council Bluffs; where, arranging his necessary outfit of men, horses, provisions, &c., (being supplied with good instruments for making necessary observations,) he stretched across a vast tract of country to the extreme head-waters of the St. Peter’s, determining, as he went, the heights of places above the ocean, the latitude and longitude of certain points, with magnetic variations. He reached the highland dividing the waters of the St. Peter’s from those of the Red river of the North. He descended the St. Peter’s to its mouth; examined the position and geology of St. Anthony’s falls, and then ascended the same river as high as the Crow-wing river. The secondary rock observed below the falls, changes for greenstone, sienite, &c., with erratic boulders. On the east side of the river, a little below Pikwabik, is a large mass of sienitic rock with flesh-colored feldspar, extending a mile in length, half a mile in width, and 80 feet high. This is called the Little Rock. Higher up, on the same side, at the foot on the Knife rapids, there are sources that transport a very fine, brilliant, and bluish sand, accompanied by a soft and unctuous matter. This appears to be the result of the decomposition of a steachist, probably interposed between the sienitic rocks mentioned. The same thing is observed at the mouths of the Wabezi and Omoshkos rivers.

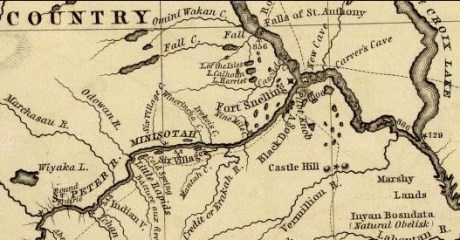

Detail of Saint Anthony’s Falls and Saint Peter’s River from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

Ascending the Crow-wing river a short distance, Mr. Nicollet turned up Gull river, and proceeded as far as Pine river, taking White Fish lake in his way; and again ascended the east fork of Pine river, and reached Little Bay river, which he descended over rapids, &c., to Leech lake, where he spent some days in making astronomical observations, &c. From Leech lake, he proceeded, through small streams and lakes, to that in which the Mississippi heads, called Itasca. Having made all necessary observations at this point, he set out on his return down the Mississippi; and finally, reaching Fort Snelling at St. Peter’s, he spent the winter there.

Detail of Leech Lake and Lake Itasca from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

Lake Itasca, in which the Mississippi heads, Mr. Nicollet found to be about 1,500 feet above the level of the ocean, and lying in lat. about 47° 10′ north, and in lon. 95° west of Greenwich.

This vast basin of the Upper Mississippi forms a most interesting and valuable portion of the North American continent. From the number of its running streams and fresh-water lakes, and its high latitude, it cannot fail to prove a healthy residence for its future population.

It also contains the most extensive body of pine timber to be found in the entire valley of the Mississippi, and from which the country extending from near St. Anthony’s falls to St. Louis, for a considerable distance on each side of the river, and up many of its tributaries, must draw supplies of lumber for building purposes.

In addition to these advantages, the upper basin is rich in mines of lead and copper; and it is not improbable that silver may also be found. Its agricultural resources are also very great. Much of the land is most beautifully situated, and fertile in a high degree. The climate is milder than that found on the same parallel of latitude east of the Alleghany mountains. Mr. Nicollet fixes the mean temperature at Itasca lake at 43° to 44°; and at St. Peter’s near St. Anthony’s falls, at 45° to 46°

“Maiden Rock. Mississippi River.“ by Currier & Ives. Maiden’s Rock Bluff. This location is now designated as Maiden Rock Bluff State Natural Area.

~ SpringfieldMuseums.org

Every part of this great basin that is arable will produce good wheat, potatoes, rye, oats, Indian corn to some extent, fine grasses, fruits, garden vegetables, &c. There is no part of the Mississippi river flanked by such bold and picturesque ranges of hills, with flattened, broad summits, as are seen extending from St. Anthony’s falls down to Prairie du Chien, including those highlands bordering Lake Pepin, &c. Among the cliffs of sandstone jutting out into perpendicular bluffs near the river, (being frequently over 100 feet high,) is seen one called Maiden’s rock. it is said an Indian chief wished to force his daughter to marry another chief, while her affections were placed on another Indian; and that, rather than yield to her father’s wishes, she cast herself over this tall precipice, and met an instant death. On hearing of which, her real lover, it is said, also committed suicide. Self-destruction is very rare among the Indians; and we imagine, when it does occur, it must be produced by the strongest kind of influence over their passions. Mental alienation, if not entirely unknown among them, must be exceedingly rare. I have no recollection of ever having heard of a solitary case.

From St. Anthony’s falls to St. Louis is 900 miles. The only impediment to the regular navigation of the river by steamboats, is experienced during low water at the upper and lower rapids.

“St. Louis Map circa 1845”

~ CampbellHouseMuseum.org

The first are about 14 miles long, with a descent of only about 25 feet. The lower rapids are 11 miles long, with a descent of 24 feet. In each case, the water falls over beds of mountain or carboniferrous limestone, which it has worn into irregular and crooked channels. By a moderate expenditure of money on the part of the general government, which ought to be made as early as practicable, these rapids could be permanently opened to the passage of boats. As it is at present, boats, in passing the rapids at low water, and especially the lower rapids, have to employ barges and keel-boats to lighten them over, at very great expense.

From the rapid settlement of the country above, with the increasing trade in lumber and lead, the business on the Upper Mississippi is augmenting at a prodigious rate. When the river is sufficiently high to afford no obstruction on the lower rapids, not less than some 28 or 30 boats run regularly between Galena and St. Louis – the distance being 500 miles. Besides these, two or three steam packets run regularly to St. Anthony’s falls, or to St. Peter’s, near the foot of them. Every year will add greatly to the number of these boats. Other fine large and well-found packets run from St. Louis to Keokuk, at the foot of the lower rapids, four miles below which the Des Moines river enters the Mississippi river. It is the opinion of Mr. Nicollet, that this river can be opened, by some slight improvements, for 100 miles above its mouth. It is said the extensive body of land lying between the Des Moines and the Mississippi, and running for a long distance parallel with the left bank of the latter, contains the most lovely,rich and beautiful land to be found on the continent, if not in the world. It is already pretty thickly settled. Splendid crops of wheat and corn have been raised on farms opened upon it, the present year. Much of the former we found had already arrived at depots on the river, in quantities far too great to find a sufficient number of boats, at the present low water, to carry it to market.

I do not see but the democratic party are regularly gaining strength throughout the great West, as the results of the recent elections, which have already reached you, sufficiently indicate.

Those who wish to obtain more general, as well as minute information, respecting the basin of the Upper Mississippi, I would recommend to consult the able report, accompanied with a fine map of the country, by Mr. J. N. Nicollet, and reprinted by order of the Congress at their last session.

I am, very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

MORGAN.

This curious series of correspondences from “Morgan” is continued in the September 1 and September 5 issues of The Daily Union, where he arrived in New York City again after 4,200 miles and two and a half months on this delegation. As those articles are not pertinent to the greater realm of Chequamegon History, this concludes our reproduction of these curious correspondences.

The End.

Wisconsin Territory Delegation: The Copper Region

April 17, 2016

By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from Copper Harbor.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 21, 1845.

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE.

—

[From our Regular Correspondent.]

THE COPPER REGION.

La Pointe, Lake Superior

July 28, 1845.

Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

In my last brief letter from this place, I had not time to notice many things which I desired to describe. I have now examined the whole coast of the southern shore of Lake Superior, extending from the Sault Ste. Marie to La Pointe, including a visit to the Anse, and the doubling of Keweena point. During the trip, as stated previously, we had camped out twenty-one nights. I examined the mines worked by the Pittsburg company at Copper harbor, and those worked by the Boston company at Eagle river, as well as picked up all the information I could about other portions of the mineral district, both off and on shore. The object I had in view when visiting it, was to find out, as near as I could, the naked facts in relation to it. The distance of the lake-shore traversed by my part to La Pointe was about five hundred miles – consuming near four weeks’ time to traverse it. I have still before me a journey of three or four hundred miles before I reach the Mississippi river, by the way of the Brulé and St. Croix rivers. I know the public mind has been recently much excited in relation to the mineral region of country of Lake Superior, and that a great many stories are in circulation about it. I know, also, that what is said and published about it, will be read with more or less interest, especially by parties who have embarked in any of the speculations which have been got up about it. It is due to truth and candor, however, for me to declare it as my opinion, that the whole country has been overrated. That copper is found scattered over the country equal in extent to the trap-rock hills and conglomerate ledges, either in its native state, or in the form of a black oxide, as a green silicate, and, perhaps, in some other forms, cannot be denied;- but the difficulty, so far, seems to be that the copper ores are too much diffused, and that no veins such as geologist would term permanent have yet positively been discovered.

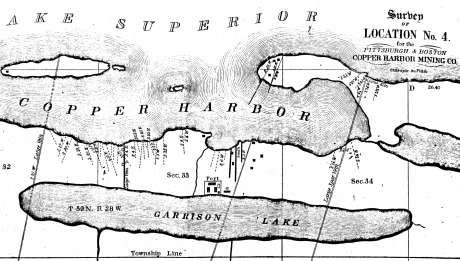

Detail of a Survey of Location No. 4 for the Pittsburgh & Boston Copper Harbor Mining Co. Image digitized by the Detroit Public Library Burton Historical Collection for The Cliff Mine Archeology Project Blog.

The richest copper ore yet found is that raised from a vein of black oxide, at Copper harbor, worked by the Pittsburg company, which yields about seventy per cent. of pure copper. But this conglomerate cementation of trap-rock, flint, pebbles, &c., and sand, brought together in a fused black mass, (as is supposed, by the overflowings of the trap, of which the hills are composed near this place,) is exceedingly hard and difficult to blast. An opinion seems to prevail among many respectable geologist, that metallic veins found in conglomerate are never thought to be very permanent. Doctor Pettit, however, informed me that he had traced the vein for near a mile through the conglomerate, and into the hill of trap, across a small lake in the rear of Fort Wilkins. The direction of the vein is from northwest to southeast through the conglomerate, while the course of the lake-shore and hills at this place varies little from north and south. Should the doctor succeed in opening a permanent vein in the hill of trap opposite, of which he is sanguine, it is probable this mine will turn out to be exceedingly valuable. As to these matters, however, time alone, with further explorations, must determine. The doctor assured me that he was at present paying his way, in merely sinking shafts over the vein preparatory to mining operations; which he considered a circumstance favorable to the mine, as this is not of common occurrence.

The mines at Copper harbor and Eagle river are the only two as yet sufficiently broached to enable one to form any tolerably accurate opinion as to their value or prospects.

~ Encyclopedia of the Earth

Other companies are about commencing operations, or talk of doing so – such as a New York, or rather Albany company, calling themselves “The New York and Lake Superior Mining Company,” under the direction of Mr. Larned, of Albany, in whose service Dr. Euhts has been employed as geologist. They have made locations at various points – at Dead river, Agate harbor, and at Montreal river. I believe they have commenced mining to some extent at Agate harbor.

One or two other Boston companies, besides that operating at Eagle river, have been formed with the design of operating at other points. Mr. Bernard, formerly of St. Louis, is at the head of one of them. Besides these, there is a kind of Detroit company, organized, it is said, for operating on the Ontonagon river. It has its head, I believe, in Detroit, and its tail almost everywhere. I have not heard of their success in digging, thus far; though they say they have found some valuable mines. Time must determine that. I wish it may be so.

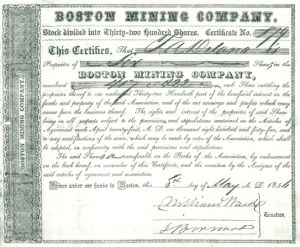

Boston Mining Company stock issued by Joab Bernard in 1846.

~ Copper Country Reflections

From Copper harbor, I paid a visit to Eagle river – a small stream inaccessible to any craft larger than a moderate-sized Mackinac boat. There is only the open lake for a roadstead off its mouth, and no harbor nearer than Eagle harbor, some few miles to the east of it. In passing west from Copper harbor along the northern shore of Keweena point, the coast, almost from the extremity of Keweena point, to near Eagle river, is an iron-bound coast, presenting huge, longitudinal, black, irregular-shaped masses of trap-conglomerate, often rising up ten or fifteen feet high above water, at some distance from the main shore, leaving small sounds behind them, with bays, to which there are entrances through broken continuities of the advanced breakwater-like ledges. Copper harbor is thus formed by Porter’s island, on which the agency has been so injudiciously placed, and which is nothing but a conglomerate island of this character; with its sides next the lake raised by Nature, so as to afford a barrier against the waves that beat against it from without. The surface of the island over the conglomerate is made up of a mass of pebbles and fragmentary rock, mixed with a small portion of earth, wholly or quite incapable of cultivation. Fort Wilkins is located about two miles from the agency, on the main land, between which and the fort communication in winter is difficult, if not impossible. Of the inexcusable blunder made in putting this garrison on its present badly-selected site, I shall have occasion to speak hereafter.

“Grand Sable Dunes”

~ National Park Service

In travelling up the coast from Sault Ste. Marie, the first 50 or 100 miles, the shore of Lake Superior exhibits, for much of the distance, a white sandy beach, with a growth of pines, silver fir, birch, &c., in the rear. This beach is strewed in places with much whitened and abraded drift-wood, thrown high on the banks by heavy waves in storms, and the action of ice in winter. This drift-wood is met with, at places, from one end of the lake to the other, which we found very convenient for firewood at our encampments. The sand on the southern shore terminates, in a measure, at Grand Sables, which are immense naked pure sand-hills, rising in an almost perpendicular form next to the lake, of from 200 to 300 feet high. Passing this section, we come to white sand-stone in the Pictured Rocks. Leaving these, we make the red sand-stone promontories and shore, at various points from this section, to the extreme end of the lake. It never afterwards wholly disappears. Between promontories of red stone are headlands, &c., standing out often in long, high irregular cliffs, with traverses of from 6, 7, to 8 miles from one to the other, while a kind of rounded bay stretches away inland, having often a sandy beach at its base, with pines growing in the forest in the rear. Into these bays, small rivers, nearly or quite shut in summer with sand, enter the lake.

The first trap-rock we met with, was near Dead river, and at some few points west of it. We then saw no more of it immediately on the coast, till we made the southern shore of Keweena point. All around the coast by the Anse, around Keweena bay, we found nothing but alternations of sand beaches and sand-stone cliffs and points. The inland, distant, and high hills about Huron river, no doubt, are mainly composed of trap-rock.

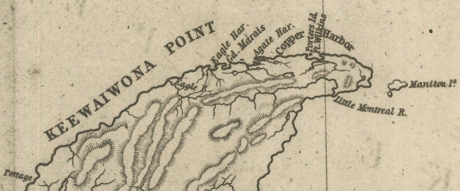

Detail from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Going west from Eagle river, we soon after lost both conglomerate and trap-rock, and found, in their stead, our old companions – red sand-stone shores, cliffs, and promontories, alternating with sandy or gravelly beaches.

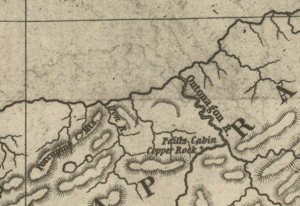

Detail of the Ontonagon River, “Paul’s Cabin,” the Ontonagon Boulder, and the Porcupine Mountains from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The trap-rock east and west of the Portage river rises with, and follows, the range of high hills running, at most points irregularly, from northeast to southwest, parallel with the lake shore. It is said to appear in the Porcupine mountain, which runs parallel with Iron river, and at right angles to the lake shore. This mountain is so named by the Indians, who conceived its principal ridge bore a likeness to a porcupine; but, to my fancy, it bears a better resemblance to a huge hog, with its snout stuck down at the lake-shore, and its back and tail running into the interior. This river and mountain are found about twenty miles west of the Ontonagon river, which is said to be the largest stream that empties into the lake. The site for a farm, or the location of an agency, at its mouth, is very beautiful, and admirably suited for either purpose. The soil is good; the river safe for the entrance and secure anchorage of schooners, and navigable to large barges and keel-boats for twelve miles above its mouth. The trap range, believed to be as rich in copper ores as any part of Lake Superior, crosses this river near its forks, about fifteen miles above its mouth. The government have organized a mineral agency at its mouth, and appointed Major Campbell as agent to reside at it; than whom, a better selection could not have been made.

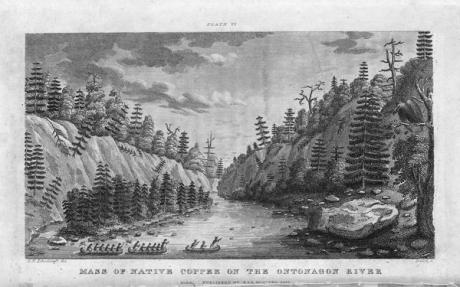

“Engraving depicting the Schoolcraft expedition crossing the Ontonagon River to investigate a copper boulder.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Detail of the Montreal River, La Pointe, and Chequamegon bay from from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The nearest approach the trap-rock hills make to the lake-shore, beyond the Porcupine mountain, is on the Montreal river, a short distance above the falls. Beyond Montreal river, to La Pointe, we found red-clay cliffs, based on red sand-stone, to occur. Indeed, this combination frequently occurred at various sections of the coast – beginning, first, some miles west of the Portage.

From Copper harbor to Agate harbor is called 7 miles; to Eagle river, 20 miles; to the Portage, 40 miles; to the Ontonagon, 80 miles; to La Pointe, from Copper harbor, 170 miles. From the latter place to the river Brulé is about 70 miles; up which we expect to ascend for 75 miles, make a portage of three miles to the St. Croix river, and descend that for 300 miles to the Mississippi river.

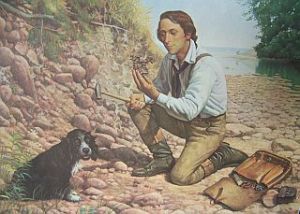

Painting of Professor Douglass Houghton by Robert Thom. Houghton first explored the south shore of Lake Superior in 1840, and died on Lake Superior during a storm on October 13, 1845. Chequamegon Bay’s City of Houghton was named in his honor, and is now known as Houghton Falls State Natural Area.

Going back to Eagle river, at the time of our visit, we found at the mine Mr. Henshaw, Mr. Williams, and Dr. Jackson of Boston, and Dr. Houghton of Michigan, who was passing from Copper harbor to meet his men at his principal camp on Portage river, which he expected to reach that night. The doctor is making a rapid and thorough survey of the country. This work he is conducting in a duplicate manner, under the authority of the United States government. It is both a topographical and geological survey. All his surveyors carry sacks, into which they put pieces of rock broken from every prominent mass they see, and carry into camp at night, for the doctor’s examination, from which he selects specimens for future use. The doctor, from possessing extraordinary strength of constitution, can undergo exposure and fatigue sufficient to break down some of the hardiest men that can be found in the West. He wears his beard as long as a Dunkard’s; has a coat and patched pants made of bed ticking; wears a flat-browned ash-colored, wool hat, and a piece of small hemp cord off a guard chain; and, with two half-breed Indians and a small dog as companions, embarks in a small bark, moving and travelling along the lake shore with great celerity.

Probably no company on Lake Superior has had a longer and harder struggle against adversity than the Phœnix. The original concern, the Lake Superior Copper Company, was among the first which operated at Lake Superior after the relinquishment of the Indian rights to this country in 1843. The trustees of this early organization were David Henshaw and Samuel Williams of Boston, and D. G. Jones and Col. Chas. H. Gratiot, of Detroit; Dr. Charles T. Jackson examined the veins on the property, and work was begun in the latter part of the year 1844. The company met with bad luck from the start, and, the capital stock having become exhausted, it has been reorganized several times in the course of its history.”

~ The Lake Superior Copper Properties: A Guide to Investors and Speculators in in Lake Superior Copper Shares Giving History, Products, Dividend Record and Future Outlook for Each Property, by Henry M. Pinkham, 1888, page 9.

We all sat down to dinner together, by invitation of Mr. Williams, and ate heartily of good, wholesome fare.

After dinner we paid a visit to the shafts at the mine, sunk to a considerable depth in two or three places. Only a few men were at work on one of the shafts; the others seemed to be employed on the saw-mill erecting near the mouth of the river. Others were at work in cutting timbers, &c.

They had also a crushing-mill in a state of forwardness, near the mine.

It is what has been said, and put forth about the value of this mineral deposite, which has done more to incite and feed the copper fever than all other things put together.

Professor Charles Thomas Jackson.

~ Contributions to the History of American Geology, plate 11, opposite page 290.

Dr. Jackson was up here last year, and has this year come up again in the service of the company. Without going very far to explore the country elsewhere, he has certainly been heard to make some very extravagant declarations about this mine,- such as that he “considered it worth a million of dollars;” that some of the ore raised was “worth $2,000 or $3,000 per ton!” So extravagant have been the talk and calculations about this mine, that shares (in its brief lease) have been sold, it is said, for $500 per share! – or more, perhaps!! No doubt, many members of the company are sincere, and actually believe the mine to be immensely valuable. Mr. Williams and General Wilson, both stockholders, strike a trade between themselves. One agrees or offers to give the other $36,000 for his interest, which the other consents to take. This transaction, under some mysterious arrangement, appears in the newspapers, and is widely copied.

Without wishing to give an opinion as to the value and permanency of this mine, (in which many persons have become, probably, seriously involved,) even were I as well qualified to do so as some others, I can only state what are the views of some scientific and practical gentlemen with whom I fell in while in the country, who were from the eastern cities, and carefully examined the famous Eagle river silver and copper mine. I do not allude to Dr. Houghton; for he declines to give an opinion to any one about any part of the country.

“The remarkable copper-silver ‘halfbreed’ specimen shown above comes from northern Michigan’s Portage Lake Volcanic Series, an extremely thick, Precambrian-aged, flood-basalt deposit that fills up an ancient continental rift valley.”

~ Shared with a Creative Commons license from James St. John

They say this mine is a deposite mine of native silver and copper in pure trap-rock, and no vein at all; that it presents the appearance of these metals being mingled broadcast in the mass of trap-rock; that, in sinking a shaft, the constant danger is, that while a few successive blasts may bring up very rich specimens of the metals, the succeeding blast or stroke of the pick-axe may bring up nothing but plain rock. In other words, that, in all such deposite mines, including deposition of diffused particles of native meteals, there is no certainly their PERMANENT character. How far this mine will extend through the trap, or how long it will hold out, is a matter of uncertainty. Indeed, time alone will show.

It is said metallic veins are most apt to be found in a permanent form where the mountain limestone and trap come in contact.

I have no prejudice against the country, or any parties whatever. I sincerely wish the whole mineral district, and the Eagle mine in particular, were as rich as it has been represented to be. I should like to see such vast mineral wealth as it has been held forth to be, added to the resources of the country.

Unless Dr. Pettit has succeeded in fixing the vein of black oxide in the side of the mountain or hill, it is believed by good judges that no permanent vein has yet been discovered, as far as has come to their knowledge, in the country!! That much of the conglomerate and trap-rock sections of the country, however, presents strong indications and widely diffused appearances of silver and copper ores, cannot be denied; and from the great number of active persons engaged in making explorations, it is possible, if not probable, that valuable veins may be discovered in some portions of the country.

To find such out, however, if they exist, unless by accident, must be the work of time and labor – perhaps of years – as the interior is exceedingly difficult, or rather almost impossible, to examine, on account of the impenetrable nature of the woods.

During our long and tedious journey, we were favored with a good deal of fine weather. We however experienced, first and last, five or six thunderstorms, and some tolerably severe gales.

Coasting for such a great length, and camping out at night, was not without some trials and odd incidents – mixed with some considerable hardships.

On the night before we reached La Pointe, we camped on a rough pebbly beach, some six or eight miles east of Montreal river, under the lea of some high clay cliffs. We kindled our fire on what appeared to be a clear bed of rather large and rounded stones, at the mouth of a gorge in the cliffs.

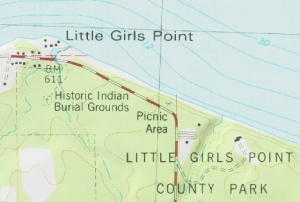

Topographic map of the gorge in the cliffs at Little Girl’s Point County Park.

~ United States Geological Survey

Next morning early, the fire was rekindled at the same spot, although some rain had falled in the night it being still cloudy, and heavy thunder rolling, indicating an approaching storm. I had placed some potatoes in the fire to roast, while some of the voyageurs were getting other things ready for breakfast; but before we could get anything done, the rain down upon us in torrents. We soon discovered that we had kindled our fire in the bed of a wet weather creek. The water rapidly rose, put out the fire, and washed away my potatoes.

We had then to kindle a new fire at a higher place, which was commenced at the end of a small crooked log. One of the voyageurs had set the frying-pan on the fire with an Indian pone or cake an inch thick, and large enough to cover the bottom it. The under side had begun to bake; another hand had mixed the coffee, and set the coffee-pot on to boil; while a third had been nursing a pot boiling with pork and potatoes, which, as we were detained by rain, the voyageurs thought best to prepare for two meals. One of the part, unfortunately, not observing the connexion between the crooked pole, and the fire at the end of it, jumped with his whole weight on it, which caused it suddenly to turn. In its movement, it turned the frying-pan completely over on the sand, with its contents, which became plastered to the dirt. The coffee-pot was also trounced bottom upwards, and emptied its contents on the sand. The pot of potatoes and pork, not to be outdone, turned over directly into the fire, and very nearly extinguished it. We had, in a measure, to commence operations anew, it being nearly 10 o’clock before we could get breakfast. When near the Madelaine islands, (on the largest of which La Pointe is situated,) the following night, our pilot, amidst the darkness of the evening, got bewildered for a time, when we thought best to land and camp; which, luckily for us, was at a spot within sight of La Pointe. Many trifling incidents of this character befell us in our long journey.

Lake Bands:

“Ki ji ua be she shi, 1st [Chief].

Ke kon o tum, 2nd [Chief].”

Pelican Lakes:

“Kee-che-waub-ish-ash, 1st chief, his x mark.

Nig-gig, 2d chief, his x mark.“

Lac Courte Oreilles Band:

At the mouth of the Montreal river, we fell in with a party of seventeen Indians, composed of old Martin and his band, on their way to La Pointe, to be present at the payment expected to take place about the 15th of August.

They had their faces gaudily painted with red and blue stripes, with the exception of one or two, who had theirs painted quite black, and were said to be in mourning on account of deceased friends. They had come from Pelican lake (or, as the French named it, Lac du Flambeau,) being near the headwaters of the Wisconsin river, and one hundred and fifty miles distant. They had with them their wives; children, dogs, and all, walked the whole way. They told our pilot, Jean Baptiste, himself three parts Indian, that they were hungry, and had no canoe with which to get on to La Pointe. We gave them some corn meal, and received some fish from them for a second supply. For the Indians, if they have anything they think you want, never offer generally to sell it to you, till they have first begged all they can; then they will produce their fish, &c., offering to trade; for which they expect an additional supply of the article you have been giving them. Baptiste distributed among them a few twists of tobacco, which seemed very acceptable. Old Martin presented Baptiste with a fine specimen of native copper which he had picked up somewhere on his way – probably on the headwaters of the Montreal river. He desired us to take one of his men with us to La Pointe, in order that he might carry a canoe back to the party, to enable them to reach La Pointe the next day, which we accordingly complied with. We dropped him, however, at his own request, on the point of land some miles south of La Pointe, where he said he had an Indian acquaintance, who hailed him from shore.

Having reached La Pointe, we were prepared to rest a few days, before commencing our voyage to the Mississippi river.

Of things hereabouts, and in general, I will discourse in my next.

In great haste I am,

Very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

MORGAN.

To be continued in La Pointe…

In the Fall of 1850, the Lake Superior Ojibwe (Chippewa) bands were called to receive their annual payments at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi River. The money was compensation for the cession of most of northern Wisconsin, Upper Michigan, and parts of Minnesota in the treaties of 1837 and 1842. Before that, payments had always taken place in summer at La Pointe. That year they were switched to Sandy Lake as part of a government effort to remove the entire nation from Wisconsin and Michigan in blatant disregard of promises made to the Ojibwe just a few years earlier.

There isn’t enough space in this post to detail the entire Sandy Lake Tragedy (I’ll cover more at a later date), but the payments were not made, and 130-150 Ojibwe people, mostly men, died that fall and winter at Sandy Lake. Over 250 more died that December and January, trying to return to their villages without food or money.

George Warren (b.1823) was the son of Truman Warren and Charlotte Cadotte and the cousin of William Warren. (photo source unclear, found on Canku Ota Newsletter)

If you are a regular reader of Chequamegon History, you will recognize the name of William Warren as the writer of History of the Ojibway People. William’s father, Lyman, was an American fur trader at La Pointe. His mother, Mary Cadotte was a member of the influential Ojibwe-French Cadotte family of Madeline Island. William, his siblings, and cousins were prominent in this era as interpreters and guides. They were people who could navigate between the Ojibwe and mix-blood cultures that had been in this area for centuries, and the ever-encroaching Anglo-American culture.

The Warrens have a mixed legacy when it comes to the Sandy Lake Tragedy. They initially supported the removal efforts, and profited from them as government employees, even though removal was completely against the wishes of their Ojibwe relatives. However, one could argue this support for the government came from a misguided sense of humanitarianism. I strongly recommend William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader by Theresa Schenck if you are interested in Warren family and their motivations. The Wisconsin Historical Society has also digitized several Warren family letters, and that’s what prompted this post. I decided to transcribe and analyze two of these letters–one from before the tragedy and one from after it.

The first letter is from Leonard Wheeler, a missionary at Bad River, to William Warren. Initially, I chose to transcribe this one because I wanted to get familiar with Wheeler’s handwriting. The Historical Society has his papers in Ashland, and I’m planning to do some work with them this summer. This letter has historical value beyond handwriting, however. It shows the uncertainty that was in the air prior to the removal. Wheeler doesn’t know whether he will have to move his mission to Minnesota or not, even though it is only a month before the payments are scheduled.

Sept 6, 1850

Dear Friend,

I have time to write you but a few lines, which I do chiefly to fulfill my promise to Hole in the Day’s son. Will you please tell him I and my family are expecting to go Below and visit our friends this winter and return again in the spring. We heard at Sandy Lake, on our way home, that this chief told [Rev.?] Spates that he was expecting a teacher from St. Peters’ if so, the Band will not need another missionary. I was some what surprised that the man could express a desire to have me come and live among his people, and then afterwards tell Rev Spates he was expecting a teacher this fall from St. Peters’. I thought perhaps there was some where a little misunderstanding. Mr Hall and myself are entirely undecided what we shall do next Spring. We shall wait a little and see what are to be the movements of gov. Mary we shall leave with Mr Hall, to go to school during the winter. We think she will have a better opportunity for improvement there, than any where else in the country. We reached our home in safety, and found our families all well. My wife wishes a kind remembrance and joins me in kind regards to your wife, Charlotte and all the members of your family. If Truman is now with you please remember us to him also. Tomorrow we are expecting to go to La Pointe and take the Steam Boat for the Sault monday. I can scarcely realize that nine years have passed away since in company with yourself and Pa[?] Edward[?] we came into the country.

Mary is now well and will probably write you by the bearer of this.

Very truly yours

L. H. Wheeler

By the 1850s, Young Hole in the Day was positioning himself to the government as “head chief of all the Chippewas,” but to the people of this area, he was still Gwiiwiizens (Boy), his famous father’s son. (Minnesota Historical Society)

By the 1850s, Young Hole in the Day was positioning himself to the government as “head chief of all the Chippewas,” but to the people of this area, he was still Gwiiwiizens (Boy), his famous father’s son. (Minnesota Historical Society)Samuel Spates was a missionary at Sandy Lake. Sherman Hall started as a missionary at La Pointe and later moved to Crow Wing.

Mary, Charlotte, and Truman Warren are William’s siblings.

The Wheeler letter is interesting for what it reveals about the position of Protestant missionaries in the 1850s Chequamegon region. From the 1820s onward, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent missionaries, mostly Congregationalists and Presbyterians from New England, to the Lake Superior Country. Their names, Wheeler, Hall, Ely, Boutwell, Ayer, etc. are very familiar to historians, because they produced hundreds of pages of letters and diaries that reveal a great deal about this time period.

Leonard H. Wheeler (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Ojibwe people reacted to these missionaries in different ways. A few were openly hostile, while others were friendly and visited prayer, song, and school meetings. Many more just ignored them or regarded them as a simple nuisance. In forty-plus years, the amount of Ojibwe people converted to Protestantism could be counted on one hand, so in that sense the missions were a spectacular failure. However, they did play a role in colonization as a vanguard for Anglo-American culture in the region. Unlike the traders, who generally married into Ojibwe communities and adapted to local ways to some degree, the missionaries made a point of trying to recreate “civilization in the wilderness.” They brought their wives, their books, and their art with them. Because they were not working for the government or the Fur Company, and because they were highly respected in white-American society, there were times when certain missionaries were able to help the Ojibwe advance their politics. The aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy was such a time for Wheeler.

This letter comes before the tragedy, however, and there are two things I want to point out. First, Wheeler and Sherman Hall don’t know the tragedy is coming. They were aware of the removal, and tentatively supported it on the grounds that it might speed up the assimilation and conversion of the Ojibwe, but they are clearly out of the loop on the government’s plans.

Second, it seems to me that Hole in the Day is giving the missionaries the runaround on purpose. While Wheeler and Spates were not powerful themselves, being hostile to them would not help the Ojibwe argument against the removal. However, most Ojibwe did not really want what the missionaries had to offer. Rather than reject them outright and cause a rift, the chief is confusing them. I say this because this would not be the only instance in the records of Ojibwe people giving ambiguous messages to avoid having their children taken.

Anyway, that’s my guess on what’s going on with the school comment, but you can’t be sure from one letter. Young Hole in the Day was a political genius, and I strongly recommend Anton Treuer’s The Assassination of Hole in the Day if you aren’t familiar with him.

I read this as “passed away since in company with yourself and Pa[?] Edward we came into the country.” Who was Wheeler’s companion when a young William guided him to La Pointe? I intend to find out and fix this quote. (from original in the digital collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society)

In 1851, Warren was in failing health and desperately trying to earn money for his family. He accepted the position of government interpreter and conductor of the removal of the Chippewa River bands. He feels removing is still the best course of action for the Ojibwe, but he has serious doubts about the government’s competence. He hears the desires of the chiefs to meet with the president, and sees the need for a full rice harvest before making the journey to La Pointe. Warren decides to stall at Lac Courte Oreilles until all the Ojibwe bands can unite and act as one, and does not proceed to Lake Superior as ordered by Watrous. The agent is getting very nervous.

Clement and Paul (pictured) Hudon Beaulieu, and Edward Conner, were mix-blooded traders who like the Warrens were capable of navigating Anglo-American culture while maintaining close kin relationships in several Ojibwe communities. Clement Beaulieu and William Warren had been fierce rivals ever since Beaulieu’s faction drove Lyman Warren out of the American Fur Company. (Photo original unknown: uploaded to findadagrave.com by Joan Edmonson)

Clement and Paul (pictured) Hudon Beaulieu, and Edward Conner, were mix-blooded traders who like the Warrens were capable of navigating Anglo-American culture while maintaining close kin relationships in several Ojibwe communities. Clement Beaulieu and William Warren had been fierce rivals ever since Beaulieu’s faction drove Lyman Warren out of the American Fur Company. (Photo original unknown: uploaded to findadagrave.com by Joan Edmonson)For more on Cob-wa-wis (Oshkaabewis) and his Wisconsin River band, see this post.

“Perish” is what I see, but I don’t know who that might be. Is there a “Parrish”, or possibly a “Bineshii” who could have carried Watrous’ letter? I’m on the lookout. (from original in the digital collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society)

Aug 9th 1851

Friend Warren

I am now very anxiously waiting the arrival of yourself and the Indians that are embraced in your division to come out to this place.

Mr. C. H. Beaulieu has arrived from the Lake Du Flambeau with nearly all that quarter and by an express sent on in advance I am informed that P. H. Beaulieu and Edward Conner will be here with Cob-wa-wis and they say the entire Wisconsin band, there had some 32 of the Pillican Lake band come out and some now are in Conner’s Party.

I want you should be here without fail in 10 days from this as I cannot remain longer, I shall leave at the expiration of this time for Crow Wing to make the payment to the St. Croix Bands who have all removed as I learn from letters just received from the St. Croix. I want your assistance very much in making the Crow Wing payment and immediately after the completion of this, (which will not take over two days[)] shall proceed to Sandy Lake to make the payment to the Mississippi and Lake Bands.

The goods are all at Sandy Lake and I shall make the entire payment without delay, and as much dispatch as can be made it; will be quite lots enough for the poor Indians. Perish[?] is the bearer of this and he can tell you all my plans better then I can write them. give My respects to your cousin George and beli[e]ve me

Your friend

J. S. Watrous

W. W. Warren Esq.}

P. S. Inform the Indians that if they are not here by the time they will be struck from the roll. I am daily expecting a company of Infantry to be stationed at this place.

JSW

Sources:

Schenck, Theresa M., William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Treuer, Anton. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul, MN: Borealis, 2010. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Note: This is the final post of four about Lt. James Allen, his ten American soldiers and their experiences on the St. Croix and Brule rivers. They were sent from Sault Ste. Marie to accompany the 1832 expedition of Indian Agent Henry Schoolcraft to the source of the Mississippi River. Each of the posts gives some general information about the expedition and some pages from Allen’s journal.

On the night of August 1, 1831, the section of the Michigan Territory that would become the state of Wisconsin, was a scene of stark contrasts regarding the United States Army’s ability to force its will on Indian people. In the south, American forces had caught up and skirmished with the starving followers of Black Hawk near the mouth of the Bad Axe River in present-day Vernon County. The next morning, with the backing of the steamboat Warrior, the soldiers would slaughter dozens of men, women, and children as they tried to retreat across the Mississippi. The massacre at Bad Axe was the end of the Black Hawk War, the last major military resistance from the Indian nations of the Old Northwest.

Less than 300 miles upstream, Lieutenant James Allen had his bread stolen right out of his fire as he slept. Presumably, it was taken by Ojibwe youths from the Yellow River village on the St. Croix. Earlier that day, he had been unable to get convince any members of the Yellow River band to guide him up to the Brule River portage. The next morning, (the same day as the Battle of Bad Axe), Allen was able to buy a new bark canoe to take some load off his leaky fleet. However, the Ojibwe family that sold it to him was able to take advantage of supply and demand to get twice the amount of flour from the soldiers that they would’ve gotten from the local traders. Later that day, the well-known chief Gaa-bimabi (Kabamappa), from the upper St. Croix, brought him a desperately-needed map, so not all of his interactions with the Ojibwe that day were negative. However, each of these encounters showed clearly that the Ojibwe were neither cowed nor intimidated by the presence of American soldiers in their country.

In fact, Allen’s detachment must have been a miserable sight. They had fallen several days behind the voyageur-paddled canoes carrying Schoolcraft, the interpreter, and the doctor. Their canoes were leaking badly and they were running out of gum (pitch) to seal them up. Their feet were torn up from wading up the rapids, and one man was too injured to walk. They were running low on food, didn’t know how to find the Brule, and their morale was running dangerously low. If the War Department’s plan was for Allen to demonstrate American power to the Ojibwe, the plan had completely backfired.

The journey down the Brule was even more difficult for the soldiers than the trip up the St. Croix. I won’t repeat it all here because it’s in the posted pages of Allen’s journal in these four posts, but in the end, it was our old buddy Maangozid (see 4/14/13 post) and some other Fond du Lac Ojibwe who rescued the soldiers from their ordeal.

Allen’s journal entry after finally reaching Lake Superior is telling:

“[T]he management of bark canoes, of any size, in rapid rivers, is an art which it takes years to acquire; and, in this country, it is only possessed by Canadians [mix-blooded voyageurs] and Indians, whose habits of life have taught them but little else. The common soldiers of the army have no experience of this kind, and consequently, are not generally competent to transport themselves in this way; and whenever it is required to transport troops, by means of bark canoes, two Canadian voyageurs ought to be assigned to each canoe, one in the bow, and another in the stern; it will then be the safest and most expeditious method that can be adopted in this country.”

The 1830s were the years of Indian Removal throughout the United States, but at that time, the American government had no hope of conquering and subduing the Ojibwe militarily. When the Ojibwe did surrender their lands (in 1837 and 1842 for the Wisconsin parts), it was due to internal politics and economics rather than any serious threat of American invasion. Rather than proving the strength of the United States, Allen’s expedition revealed a serious weakness.

The Ojibwe weren’t overconfident or ignorant. The very word for Americans, chimookomaan (long knife), referred to soldiers. A handful of Ojibwe and mix-blooded warriors had fought the United States in the War of 1812 and earlier in the Ohio country. Bizhiki and Noodin, two chiefs whose territory Allen passed through on his ill-fated journey, had been to Washington in 1824 and saw the army firsthand. The next year, many more chiefs got to see the long knives in person at the Treaty of Prairie du Chien. Finally, the removal of their Ottawa and Potawatomi cousins and other nations to Indian Territory in the 1830s was a well-known topic of concern in Ojibwe villages. They knew the danger posed by American soldiers, but the reality of the Lake Superior Country in 1832 was that American power was very limited.

The journal picks up from part 3 with Allen and crew on the Brule River with their canoes in rapidly-deteriorating condition. They’ve made contact with the Fond du Lac villagers camped at the mouth, but there are still several obstacles to overcome.

Doc. 323, pg. 66

Allen’s journal is part of Phillip P. Mason’s edition of Schoolcraft’s Expedition to Lake Itasca: The Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi (1958). However, these Google Books pages come from the original publication as part of the United States Congress Serial Set.

James Allen (1806-1846)

Collections of the Iowa Historical Society

Allen and all of his men survived the ordeal of the 1832 expedition. He returned to La Pointe on August 11 and left the next day with Dr. Houghton. The two men returned to the Soo together, stopping at the great copper rock on the Ontonagon River along the way.

On September 13, 1832, he wrote Alexander Macomb, his commander at Fort Brady. The letter officially complained about Schoolcraft “unnecessarily and injuriously” leaving the soldiers behind at the mouth of the St. Croix. When the New York American published its review of Schoolcraft’s Narrative on July 19, 1834, it expressed “indignation and dismay” at the “un-Christianlike” behavior of the agent for abandoning the soldiers in the “enemy’s country.” The resulting controversy forced Schoolcraft to defend himself in the Detroit Journal and Michigan Advertiser where he pointed out Allen’s map’s importance to the Narrative. He also reminded the public that the Ojibwe and the United States were considered allies.

James Allen went on to serve in Chicago and at the Sac and Fox agency in Iowa Territory. After the Mexican War broke out in 1846, he traveled to Utah and organized a Mormon Battalion to fight on the American side. He died on his way back east on August 23, 1846. He was only forty years old. (John Lindquist has great website about the career of James Allen with much more information about his post-1832 life).

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Loew, Patty. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2001. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi,. [East Lansing]: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.

Note: This is the third of four posts about Lt. James Allen, his ten American soldiers and their experiences on the St. Croix and Brule rivers. They were sent from Sault Ste. Marie to accompany the 1832 expedition of Indian Agent Henry Schoolcraft to the source of the Mississippi River. Each of the posts will give some general information about the expedition and some pages from Allen’s journal.

Douglass Houghton (1809-1845) was the naturalist and physician for the expedition. While traveling with Schoolcraft’s lead group, he expressed frequent concern for Allen and the soldiers as they fell behind (painted by Alva Bradish, 1850; Wikimedia Commons).

Schoolcraft’s original book takes up the first quarter of the pages in the 1958 edition of Narrative of an Expedition, edited by Phillip P. Mason. The rest of the pages are six appendixes including the journals of Douglass Houghton the surgeon and geologist, W.T. Boutwell the missionary, and Allen. Of the four, Schoolcraft’s provides the blandest reading. His positive, official spin on everything offers little glimpse into his psyche. In contrast, Houghton gives us a unique account of smallpox vaccinations, botany, and geology. Boutwell gives us detailed descriptions of Ojibwe religious practices through his zealous missionary filter. His frequent complaints about mosquitoes, profane soldiers, Indian drumming, and voyageur gambling ruining his Sabbaths are very humorous to those who aren’t sympathetic to his mission.

Allen’s journal is fascinating. He was sent by the War Department to record information about the geography of the country and its people for military purposes. Officially the Ojibwe and the United States were friendly. Schoolcraft, being married into a prominent Ojibwe family at the Sault, promoted this idea. However, a sense of future military confrontation looms over the narrative. The Indian Removal Act was only two years old, and Black Hawk’s War broke out just as the expedition was starting out. In 1832, lasting peace between the Ojibwe and the United States was not automatically guaranteed.

The journal reads, at times, like a post-modern anti-colonial novel complete with Allen as the villainous narrator looking to get rich off Lake Superior copper and making war plans against Leech Lake. However, Allen’s writing style allows the reader in as Schoolcraft’s doesn’t, and he shows himself to be thoughtful and observant.

Allen’s primary objective was to protect Schoolcraft and show the Ojibwe that the United States could easily deliver soldiers to their remotest villages. This mission proved difficult from the beginning. Once they left Lake Superior and reached the Fond du Lac portages, it became evident that Allen’s soldiers had no canoe experience and could not keep up with Schoolcraft’s mix-blooded voyageurs. Schoolcraft never seems overly concerned about this, and much of Allen’s narrative is about his men painfully trying to catch up while the Ojibwe and mix-blooded guides laugh at their floundering techniques for getting through rapids.

Through all the hardship, though, Allen did complete the journey to Elk Lake (Itasca) and back down the Mississippi to Fort Snelling. His map of the trip was praised back east as a great contribution to world geography, and Schoolcraft used it to illustrate the published narrative. However, it was the final stretch through the St. Croix and Brule, after Schoolcraft had already declared the expedition a success, where things really got bad for the soldiers.

Continued from Part 2:

Section of Allen’s map showing the St. Croix to Brule portage. Note Gaa-bimabi’s (Keppameppa’s) village on Whitefish Lake near present-day Gordon, Wisconsin. (Reproduced by John Lindquist).

At this point, Allen and his men have fallen multiple days behind Schoolcraft. They have no knowledge of the country save a few rough maps and descriptions. Their canoes are falling apart, and they are physically beaten from their difficult journey up the St. Croix. In theory, the portage over the hill to the Brule should be an easy one given the fact they have little food and supplies left to carry. However, the men are demoralized and ready to quit. Little do they know, the darkest days of their journey are still to come.

Doc. 323, pg. 63

Allen’s journal is part of Phillip P. Mason’s edition of Schoolcraft’s Expedition to Lake Itasca: The Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi (1958). However, these Google Books pages come from the original publication as part of the United States Congress Serial Set.

Note: This is the first of four posts about Lt. James Allen, his ten American soldiers and their experiences on the St. Croix and Brule rivers. They were sent from Sault Ste. Marie to accompany the 1832 expedition of Indian Agent Henry Schoolcraft to the source of the Mississippi River. Each of the posts will give some general information about the expedition and some pages from Allen’s journal. The journal picks up July 26, 1832, after the expedition has already reached the source, proceeded downriver to Fort Snelling (Minneapolis) and was on its way back to Lake Superior.

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (1793-1864)

Although I’ve been aware of it for some time, and have used parts of it before, I only recently read Henry Schoolcraft’s, Narrative of an Expedition Through the Upper Mississippi to Itasca Lake: The Actual Source of this River from cover to cover. The book, first published in 1834, details Schoolcraft’s 1832 expedition through northern Wisconsin and Minnesota. As Indian agent at Sault Ste. Marie, he was officially sent by the Secretary of War, Lewis Cass, to investigate the ongoing warfare between the Ojibwe and Dakota Sioux. His personal goal, however, was to reach the source of the Mississippi River and be recognized as its discoverer.

Schoolcraft’s expedition included a doctor to administer smallpox vaccinations, an interpreter (Schoolcraft’s brother-in-law), and a protestant missionary. Having been west before, Schoolcraft knew what it would take to navigate the country. He hired several mix-blooded voyageurs who are hardly mentioned in the narrative, but who paddled the canoes, carried the portage loads, shot ducks, and did the other work along the way.

Ozhaawashkodewekwe (Susan Johnston) was the mother-in-law of Schoolcraft and the mother of expedition interpreter George Johnston. Born in the Chequamegon region, she is a towering figure in the history of Lake Superior during the late British and early American periods.

Attached the the expedition was Lt. James Allen and a detachment of ten soldiers, whose purpose was to demonstrate American power over the Ojibwe lands. The United States had claimed this land since the Treaty of Paris, but it was only after the War of 1812 that the British withdrew allowing American trading companies to move in. Still, by 1832 the American government had very little reach beyond its outposts at the Sault, Prairie du Chien, and Fort Snelling. The Ojibwe continued to trade with the British and war with the Dakota in opposition to their “Great Father” in Washington’s wishes.

This isn’t to say the Ojibwe were ignorant of the Americans and their military. By 1832, the Ojibwe were well aware of and concerned about the chimookomaanag (long knives) and what they were doing to other Indian nations to the south and east. However, the reality on the ground was that the Ojibwe were still in power in their lands.

Doc. 323, pg. 57

Allen’s journal is part of Phillip P. Mason’s edition of Schoolcraft’s Expedition to Lake Itasca: The Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi (1958). However, these Google Books pages come from the original publication as part of the United States Congress Serial Set.