Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Coda

June 1, 2024

My last post ended up containing several musings on the nature of primary-source research and how to acknowledge mistakes and deal with uncertainty in the historical record. This was in anticipation of having to write this post. It’s a post I’ve been putting off for years.

Amorin forced the issue with his important work on the speeches at the 1842 Treaty negotiations. While working on it, he sent me a message that read something like, “Hey, the article quotes Chief Buffalo and describes him in a blue military coat with epaulets. Is the world ready for that picture that Smithsonian guy sent us years ago?”

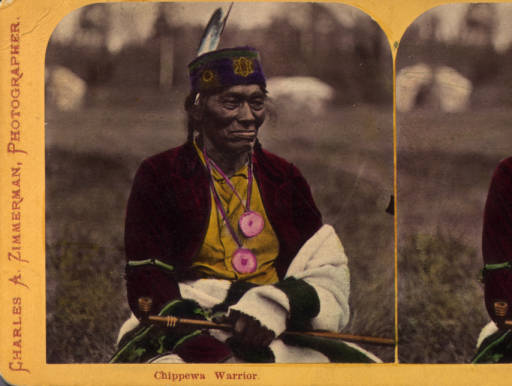

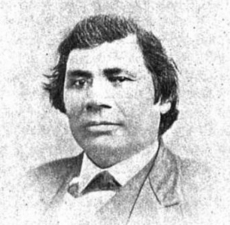

This was the image in question:

Henry Inman, Big Buffalo (Chippewa), 1832-1833, oil on canvas, frame: 39 in. × 34 in. × 2 1/4 in. (99.1 × 86.4 × 5.7 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Gerald and Kathleen Peters, 2019.12.2

We first learned of this image from a Chequamegon History comment by Patrick Jackson of the Smithsonian asking what we knew about the image and whether or not it was Chief Buffalo from La Pointe.

We had never seen it before.

This was our correspondence with Mr. Jackson at the time:

July 17, 2019

Hello, my name is Patrick, and I am an intern at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I’m working on researching a recent acquisition: a painting which came to us identified as a Henry Inman portrait of “Big Buffalo Ke-Che-Wais-Ke, The Great Renewer (1759-1855) (Chippewa).” We have run into some confusion about the identification of the portrait, as it came to us identified as stated above, yet at Harvard Peabody Museum, who was previously the owner of the portrait, it was listed as an unidentified sitter. Seeing as you’ve written a few posts about the identification of images of the three different Chief Buffalos, I thought you might be able to give some insight into perhaps who is or isn’t in the portrait we have. Thank you for your time.

July 17, 2019

Hello,

I would be happy to comment. Can you send a photo to this email?

I am pretty sure Inman painted a copy of Charles Bird King’s portrait of Pee-che-kir.

Doe it resemble that portrait? Pee-che-kir (Bizhiki) means Buffalo in Ojibwe (Chippewa). From my research, I am fairly certain that King’s portrait is not of Kechewaiske, but of another chief named Buffalo who lived in the same era.

Leon Filipczak

July 17, 2019

Dear Leon,

I have attached our portrait—it’s not the best scan, but hopefully there’s enough detail for you to work with. I’ve compared it with the Peechikir in McKenney & Hall, as well as to the Chief Buffalo painted ambrotype and the James Otto Lewis portrait of Pe-schick-ee. The ambrotype has a close resemblance, as does the Peecheckir, though if that is what Charles Bird King painted I have doubts that Inman would make such drastic changes in clothing and pose.

The identification as Big Buffalo/Ke-Che-Wais-Ke/The Great Renewer, as far as I understand, refers to the La Pointe Bizhiki/Buffalo rather than the St. Croix or Leech Lake Buffalos, though of course that is a questionable identification considering Kechewaiske did not (I think) visit Washington until after Inman’s death in January of 1846. McKenney, however, did visit the Ojibwe/Chippewa for the negotiations for the Treaty of Fond du Lac in 1825/1826, and could feasibly have met multiple Chief Buffalos. Perhaps a local artist there would be responsible for the original? Another possibility is, since the identification was not made at the Peabody, who had the portrait since the 1880s, is that it has been misidentified entirely and is unrelated to any of the Ojibwe/Chippewa chiefs. Though this, to me, would seem unlikely considering the strong resemblance of the figure in our portrait to the Peechikir portrait and Chief Buffalo ambrotype.

Thank you again for the help.

Sincerely,

Patrick

July 22, 2019

Hello Patrick,

This is a head-scratcher. Your analysis is largely what I would come up with. My first thought when I saw it was, “Who identified it as someone named Buffalo? When? and using what evidence?” Whoever associated the image with the text “Ke-Che-Wais-Ke, The Great Renewer (1759-1855)” did so decades after the painting could be assumed to be created. However, if the tag “Big Buffalo” can be attached to this image in the era it was created, then we may be onto something. This is what I know:

1) During his time as Superintendent of Indian Affairs (late 1820s), Thomas McKenney amassed a large collection of portraits of Indian chiefs for what he called the “Indian Gallery” in the War Department. He sought the portraits out wherever and whenever he could. When chiefs would come to Washington, he would have Charles Bird King do the work, but he also received portraits from the interior via artists like James Otto Lewis.

2) In 1824, Bizhiki (Buffalo) from the St. Croix River (not Great Buffalo from La Pointe), visited Washington and was painted by King. This painting is presumed to have been destroyed in the Smithsonian fire that took out most of the Indian Gallery.

3) In 1825 at Prairie du Chien and in 1826 at Fond du Lac (where McKenney was present) James Otto Lewis painted several Ojibwe chiefs, and these paintings also ended up in the Indian Gallery. Both chief Buffalos were present at these treaties.

4) A team of artists copied each others’ work from these originals. King, for example remade several of Lewis’ portraits to make the faces less grotesque. Inman copied several Indian Gallery portraits (mostly King’s) to be sent to other institutions. These are the ones that survived the Smithsonian fire.

5) In the late 1830s, 10+ years after most of the portraits were painted, Lewis and McKenney sold competing lithograph collections to the American public. McKenney’s images were taken from the Indian Gallery. Lewis’ were from his works (some of which were in the Indian Gallery, often redone by King). While the images were printed with descriptions, the accuracy of the descriptions leaves something to be desired. A chief named Bizhiki appears in both Lewis and McKenney-Hall. In both, the chiefs are dressed in white and faced looking left, but their faces look nothing alike. One is very “Lewis-grotesque.” and the other is not at all. There are Lewis-based lithographs in both competing works, and they are usually easy to spot.

6) Not every image from the Indian Gallery made it into the published lithographic collections. Brian Finstad, a historian of the upper-St. Croix country, has shown me an image of Gaa-bimabi (Kappamappa, Gobamobi), a close friend/relative of the La Pointe Chief Buffalo, and upstream neighbor of the St. Croix Buffalo. This image is held by Harvard and strongly resembles the one you sent me in style. I suspect it is an Inman, based on a Lewis (possibly with a burned-up King copy somewhere in between).

7) “Big Buffalo” would seemingly indicate Buffalo from La Pointe. The word gichi is frequently translated as both “great” and “big” (i.e. big in size or big in power). Buffalo from La Pointe was both. However, the man in the painting you sent is considerably skinnier and younger-looking than I would expect him to appear c.1826.

My sense is that unless accompanying documentation can be found, there is no way to 100% ID these pictures. I am also starting to worry that McKenney and the Indian Gallery artists, themselves began to confuse the two chief Buffalos, and that the three originals (two showing St. Croix Buffalo, and one La Pointe Buffalo) burned. Therefore, what we are left with are copies that at best we are unable to positively identify, and at worst are actually composites of elements of portraits of two different men. The fact that King’s head study of Pee-chi-kir is out there makes me wonder if he put the face from his original (1824 portrait of St. Croix Buffalo?) onto the clothing from Lewis’ portrait of Pe-shick-ee when it was prepared for the lithograph publication.

A few weeks later, Patrick sent a follow-up message that he had tracked down a second version and confirmed that Inman’s portrait was indeed a copy of a Charles Bird King portrait, based on a James Otto Lewis original. It included some critical details.

Portrait of Big Buffalo, A Chippewa, 1827 Charles Bird King (1785-1862), signed, dated and inscribed ‘Odeg Buffalo/Copy by C King from a drawing/by Lewis/Washington 1826’ (on the reverse) oil on panel 17 1⁄2 X 13 3⁄4 in. (44.5 x 34.9 cm.) Last sold by Christie’s Auction House for $478,800 on 26 May 2022

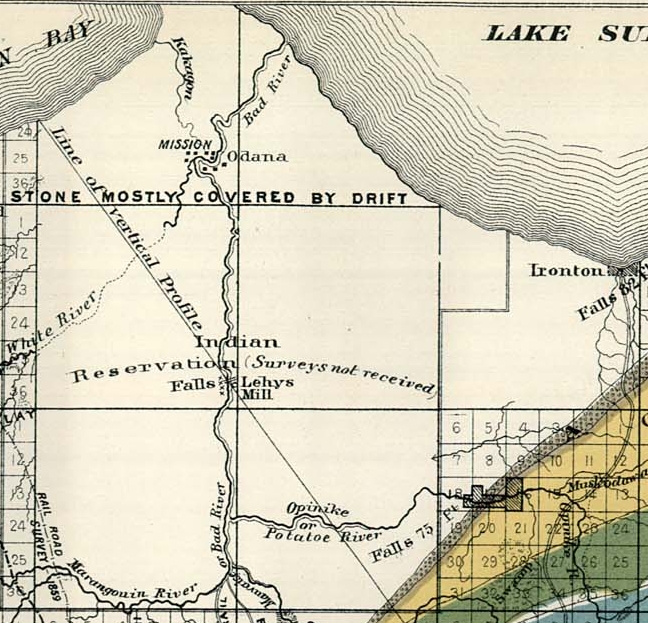

The date of 1826 makes it very likely that Lewis’ original was painted at the Treaty of Fond du Lac. Chief Buffalo of La Pointe would have been in his 60s, which appears consistent with the image of Big Buffalo. Big Buffalo also does not appear as thin in King’s intermediate version as he does in Inman’s copy, lessening the concerns that the image does not match written descriptions of the chief.

Another clue is that it appears Lewis used the word Odeg to disambiguate Big Buffalo from the two other chiefs named Buffalo present at Fond du Lac in 1826. This may be the Ojibwe word Andeg (“crow”). Although I have not seen any other source that calls the La Pointe chief Andeg, it was a significant name in his family. He had multiple close relatives with Andeg in their names, which may have all stemmed from the name of Buffalo’s grandfather Andeg-wiiyaas (Crow’s Meat). As hereditary chief of the Andeg-wiiyaas band, it’s not unreasonable to think the name would stay associated with Buffalo and be used to distinguish him from the other Buffalos. However, this is speculative.

So, there we were. After the whole convoluted Chief Buffalo Picture Search, did we finally have an image we could say without a doubt was Chief Buffalo of La Pointe? No. However, we did have one we could say was “likely” or even “probably” him. I considered posting at the time, but a few things held me back.

In the earliest years of Chequamegon History, 2013 and 2014, many of the posts involved speculation about images and me trying to nitpick or disprove obvious research mistakes of others. Back then, I didn’t think anyone was reading and that the site would only appeal to academic types. Later on, however, I realized that a lot of the traffic to the site came from people looking for images, who weren’t necessarily reading all the caveats and disclaimers. This meant we were potentially contributing to the issue of false information on the internet rather than helping clear it up. So by 2019, I had switched my focus to archiving documents through the Chequamegon History Source Archive, or writing more overtly subjective and political posts.

So, the Smithsonian image of Big Buffalo went on the back burner, waiting to see if more information would materialize to confirm the identity of the man one way or the other. None did, and then in 2020 something happened that gave the whole world a collective amnesia that made those years hard to remember. When Amorin asked about using the image for his 1842 post, my first thought was “Yeah, you should, but we should probably give it its own post too.” My second thought was, “Holy crap! It’s been five years!”

Anyway, here is Chequamegon History’s statement on the identity of the man in Henry Inman’s 1832-33 portrait of Big Buffalo (Chippewa).

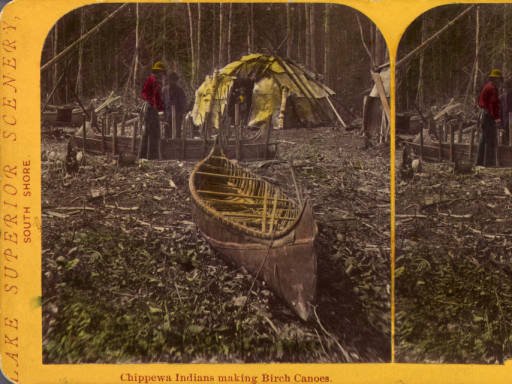

Likely Chief Buffalo of La Pointe: We are not 100% certain, but we are more certain than we have been about any other image featured in the Chief Buffalo Picture Search. This is a copy of a copy of a missing original by James Otto Lewis. Lewis was a self-taught artist who struggled with realistic facial features. Charles Bird King and Henry Inman, who made the first and second copies, respectively, had more talent for realism. However, they did not travel to Lake Superior themselves and were working from Lewis’ original. Therefore, the appearance of Big Buffalo may accurately show his clothing, but is probably less accurate in showing his actual physical appearance.

And while we’re on the subject of correcting misinformation related to images, I need to set the record straight on another one and offer my apologies to a certain Benjamin Green Armstrong. I promise, it relates indirectly to the “Big Buffalo” painting.

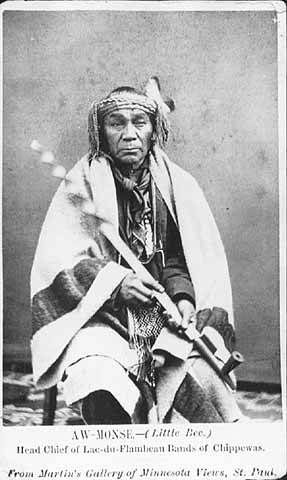

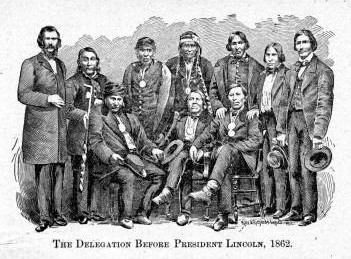

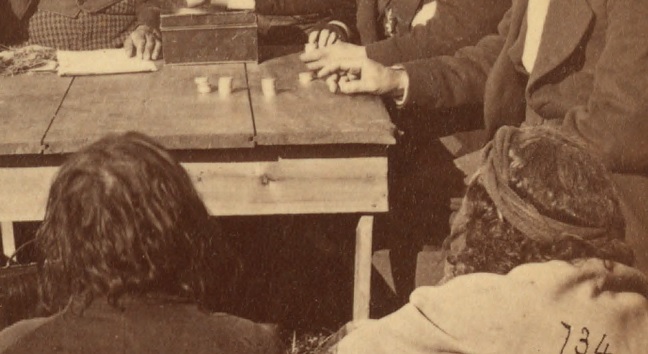

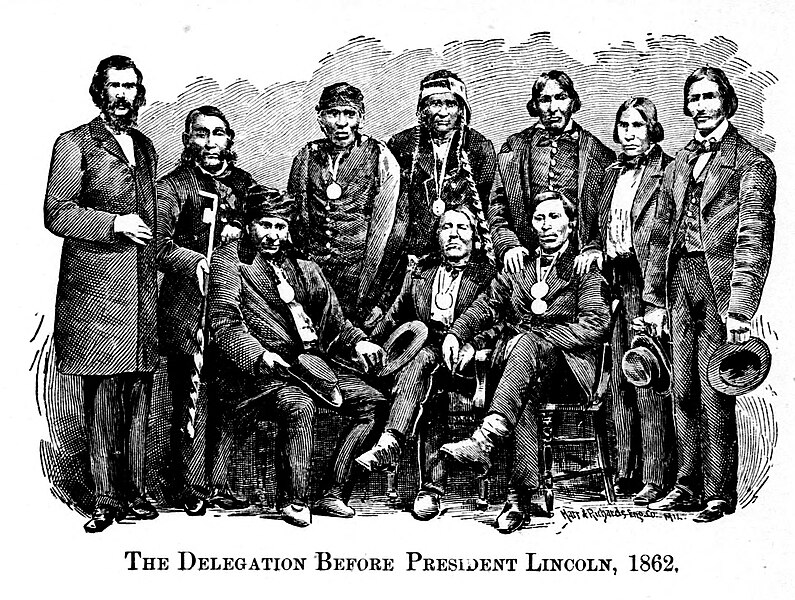

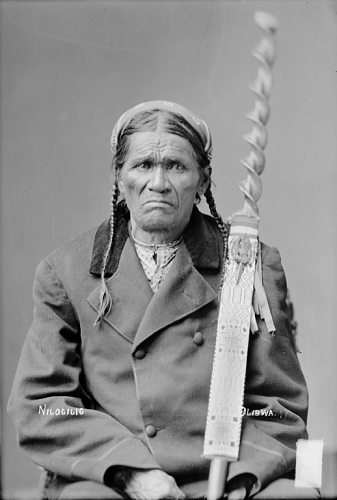

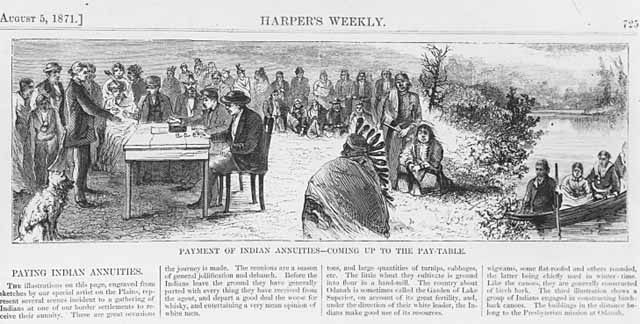

An engraving of the image in question appears in Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians.

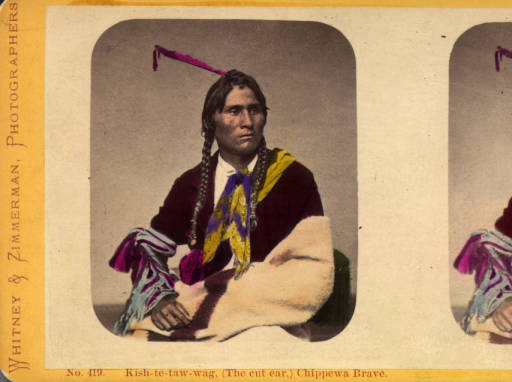

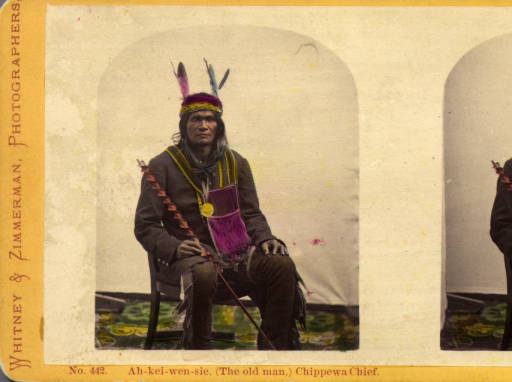

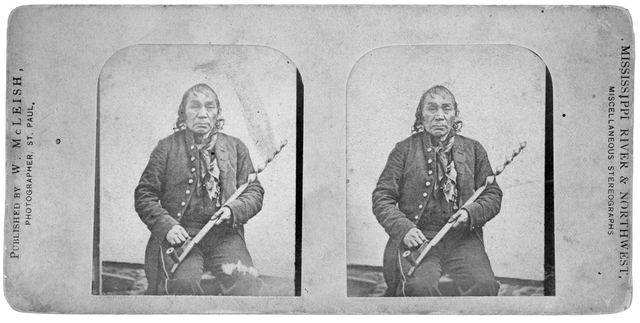

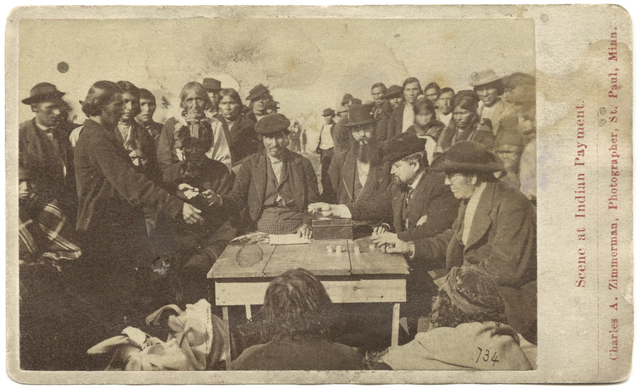

Ah-moose (Little Bee) from Lac Flambeau Reservation, Kish-ke-taw-ug (Cut Ear) from Bad River Reservation, Ba-quas (He Sews) from Lac Courte O’Rielles Reservation, Ah-do-ga-zik (Last Day) from Bad River Reservation, O-be-quot (Firm) from Fond du Lac Reservation, Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation, Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell) from La Pointe Reservation, Na-gon-ab (He Sits Ahead) from Fond du Lac Reservation, and O-ma-shin-a-way (Messenger) from Bad River Reservation.

In this post, we contested these identifications on the grounds that Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Little Buffalo) from La Pointe Reservation died in 1860 and therefore could not have been part of the delegation to President Lincoln. In the comments on that post, readers from Michigan suggested that we had several other identities wrong, and that this was actually a group of chiefs from the Keweenaw region. We commented that we felt most of Armstrong’s identifications were correct, but that the picture was probably taken in 1856 in St. Paul.

Since then, a document has appeared that confirms Armstrong was right all along.

[Antoine Buffalo, Naagaanab, and six other chiefs to W.P. Dole, 6 March 1863

National Archives M234-393 slide 14

Transcribed by L. Filipczak 12 April 2024]

To Our Father,

Hon W P. Dole

Commissioner of Indian Affairs–

We the undersigned chiefs of the chippewas of Lake Superior, now present in Washington, do respectfully request that you will pay into the hands of our Agent L. E. Webb, the sum of Fifteen Hundred Dollars from any moneys found due us under the head of “Arrearages in Annuity” the said money to be expended in the purchase of useful articles to be taken by us to our people at home.

Antoine Buffalo His X Mark | A daw we ge zhig His X Mark

Naw gaw nab His X Mark | Obe quad His X Mark

Me zhe na way His X Mark | Aw ke wen zee His X Mark

Kish ke ta wag His X Mark | Aw monse His X Mark

I certify that I Interpreted the above to the chiefs and that the same was fully understood by them

Joseph Gurnoe

U.S. Interpreter

Witnessed the above Signed } BG Armstrong

Washington DC }

March 6th 1863 }

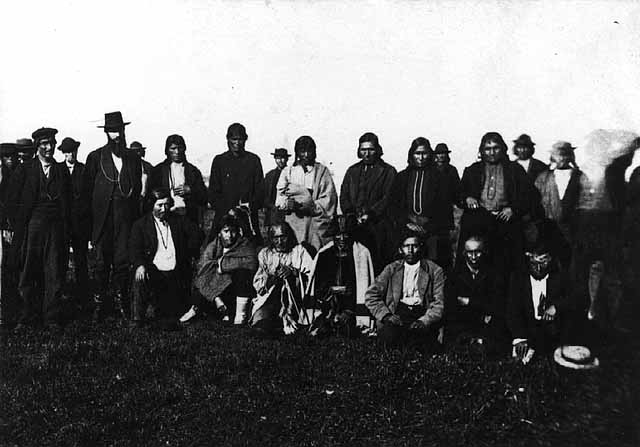

There were eight Lake Superior chiefs, an interpreter, and a witness in Washington that spring, for a total of ten people. There are ten people in the photograph. Chequamegon History is confident that this document confirms they are the exact ten identified by Benjamin Armstrong.

The Lac Courte Oreilles chief Ba-quas is the same person as Akiwenzii. It was not unusual for an Ojibwe chief to have more than one name. Chief Buffalo, Gaa-bimaabi, Zhingob the Younger, and Hole-in-the-Day the Younger are among the many examples.

The name “Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation” seems to be absent from the letter, but he is there too. Let’s look at the signature of the interpreter, Joseph Gurnoe.

Gurnoe’s beautiful looping handwriting will be familiar to anyone who has studied the famous 1864 bilingual petition. We see this same handwriting in an 1879 census of Red Cliff. In this document, Gurnoe records his own Ojibwe name as Shingwākons, The young Pine tree.

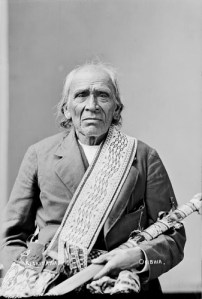

So the man standing on the far right is Gurnoe. This can be confirmed by looking at other known photos of him.

Finally, it confirms that the chief seated on the bottom left is not Jechiikwii’o (Little Buffalo), but rather his son Antoine, who inherited the chieftainship of the Buffalo Band after the death of his father two years earlier. Known to history as Chief Antoine Buffalo, in his lifetime he was often called Antoine Tchetchigwaio (or variants thereof), using his father’s name as a surname rather than his grandfather’s.

So, now we need to address the elephant in the room that unites the Henry Inman portrait of Big Buffalo with the photograph of the 1862-63 Delegation to Washington:

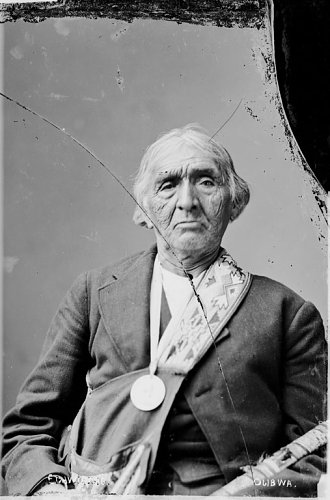

Wisconsin Historical Society

This is the “ambrotype” referenced by Patrick Jackson above. It’s the image most associated with Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. It’s also one for which we have the least amount of background information. We have not been able to determine who the original photographer/painter was or when the image was created.

The resemblance to the portrait of “Big Buffalo” is undeniable.

However, if it is connected to the 1862-63 image of Chief Antoine Buffalo, it would support Hamilton Nelson Ross’s assertions on the Wisconsin Historical Society copy.

Clearly, multiple generations of the Buffalo family wore military jackets.

Inconclusive: uncertainty is no fun, but at this point Chequamegon History cannot determine which Chief Buffalo is in the ambrotype. However, the new evidence points more toward the grandfather (Great Buffalo) and grandson (Antoine) than it does to the son (Little Buffalo).

We will keep looking.

When we die, we will lay our bones at La Pointe.

March 20, 2024

By Leo

From individual historical documents, it can be hard to sequence or make sense of the efforts of the United States to remove the Lake Superior Ojibwe from ceded territories of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan in the years 1850 and 1851. Most of us correctly understand that the Sandy Lake Tragedy was caused an alliance of government and trading interests. Through greed, deception, racism, and callous disregard for human life, government officials bungled the treaty payment at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi River in the fall and winter of 1850-51, leading to hundreds of deaths. We also know that in the spring of 1852, Chief Buffalo and a delegation of La Pointe Ojibwe chiefs travelled to Washington D.C. to oppose the removal. It is what happened before and between those events, in the summers of 1850 and 1851, where things get muddled.

Confusion arises because the individual documents can contradict our narrative. A particular trader, who we might want to think is one of the villains, might express an anti-removal view. A government agent, who we might wish to assign malicious intent, instead shows merely incompetence. We find a quote or letter that seems to explain the plans and sentiments leading to the disaster at Sandy Lake, but then we find the quote is dated after the deaths had already occurred.

Therefore, we are fortunate to have the following letter, written in November of 1851, which concisely summarizes the events up to that point. We are even more fortunate that the letter is written by chiefs, themselves. It is from the Office of Indian Affairs archives, but I found a copy in the Theresa Schenck papers. It is not unknown to Lake Superior scholarship, but to my knowledge it has not been reproduced in full.

The context is that Chief Buffalo, most (but not all) of the La Pointe chiefs, and some of their allies from Ontonagon, L’Anse, Upper St. Croix Lake, Chippewa River and St. Croix River, have returned to La Pointe. They have abandoned the pay ground at Fond du Lac in November 1851, and returned to La Pointe. This came after getting confirmation that the Indian Agent, John S. Watrous, has been telling a series of lies in order to force a second Sandy Lake removal–just one year removed from the tragedy. This letter attempts to get official sanction for a delegation of La Pointe chiefs to visit Washington. The official sanction never came, but the chiefs went anyway, and the rest is history.

La Pointe, Lake Superior, Nov. 6./51

To the Hon Luke Lea

Commissioner of Indian Affairs Washington D.C.

Our Father,

We send you our salutations and wish you to listen to our words. We the Chiefs and head men of the Chippeway Tribe of Indians feel ourselves aggrieved and wronged by the conduct of the U.S. Agent John S. Watrous and his advisors now among us. He has used great deception towards us, in carrying out the wishes of our Great Father, in respect to our removal. We have ever been ready to listen to the words of our Great Father whenever he has spoken to us, and to accede to his wishes. But this time, in the matter of our removal, we are in the dark. We are not satisfied that it is the President that requires us to remove. We have asked to see the order, and the name of the President affixed to it, but it has not been shewn us. We think the order comes only from the Agent and those who advise with him, and are interested in having us remove.

Kicheueshki. Chief. X his mark

Gejiguaio X “

Kishkitauʋg X “

Misai X “

Aitauigizhik X “

Kabimabi X “

Oshoge, Chief X “

Oshkinaue, Chief X “

Medueguon X “

Makudeua-kuʋt X “

Na-nʋ-ʋ-e-be, Chief X “

Ka-ka-ge X “

Kui ui sens X “

Ma-dag ʋmi, Chief X “

Ua-bi-shins X “

E-na-nʋ-kuʋk X “

Ai-a-bens, Chief X “

Kue-kue-Kʋb X “

Sa-gun-a-shins X “

Ji-bi-ne-she, Chief X “

Ke-ui-mi-i-ue X “

Okʋndikʋn, Chief X “

Ang ua sʋg X “

Asinise, Chief X “

Kebeuasadʋn X “

Metakusige X “

Kuiuisensish, Chief X “

Atuia X “

Gete-kitigani[inini? manuscript torn]

L. H. Wheeler

We the undersigned, certify, on honor, that the above document was shown to us by the Buffalo, Chief of the Lapointe band of Chippeway Indians and that we believe, without implying and opinion respecting the subjects of complaint contained in it, that it was dictated by, and contains the sentiments of those whose signatures are affixed to it.

S. Hall

C. Pulsifer

H. Blatchford

When I started Chequamegon History in 2013, the WordPress engine made it easy to integrate their features with some light HTML coding. In recent years, they have made this nearly impossible. At some point, we’ll have to decide whether to get better at coding or overhaul our signature “blue rectangle” design format. For now, though, I can’t get links or images into the blue rectangles like I used to, so I will have to list them out here:

Joseph Austrian’s description of the same

Boutwell’s acknowledgement of the suspension of the removal order, and his intent to proceed anyway

Chequamegon History has looked into the “Great Father” fur trade theater language of ritual kinship before in our look at Blackbird’s speech at the 1855 Payment. You may have noticed Makadebines (Blackbird) didn’t sign this letter. He was working on a different plant to resist removal. Look for a related post soon.

If you’re really interested in why the president was Gichi-noos (Great Father), read these books:

Watrous, and many of the Americans who came to the Lake Superior country at this time, were from northeastern Ohio. Watrous was able to obtain and keep his position as agent because his family was connected to Elisha Whittlesey.

In the summer and fall of 1851, Watrous was determined to get soldiers to help him force the removal. However, by that point, Washington was leaning toward letting the Lake Bands stay in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Last spring, during one of the several debt showdowns in Congress, I wrote on how similar antics in Washington contributed to the disaster of 1850. My earliest and best understanding of the 1850-1852 timeline, and the players involved, comes from this book:

We know that Kishkitauʋg (Cut Ear), and Oshoge (Heron) went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852. Benjamin Armstrong’s account is the most famous, but the delegation’s other interpreter, Vincent Roy Jr., also left his memories, which differ slightly in the details.

One of my first posts on the blog involved some Sandy Lake material in the Wheeler Family Papers, written by Sherman Hall. Since then, having seen many more of their letters, I would change some of the initial conclusions. However, I still see Hall as having committing a great sin of omission for not opposing the removal earlier. Even with the disclaimer, however, I have to give him credit for signing his name to the letter this post is about. Although they shared the common goal of destroying Ojibwe culture and religion and replacing it with American evangelical Protestantism, he A.B.C.F.M. mission community was made up of men and women with very different personalities. Their internal disputes were bizarre and fascinating.

Early Life among the Indians: Chapter II

March 21, 2018

By Amorin Mello

Early life among the Indians

by Benjamin Green Armstrong

continued from Chapter I.

CHAPTER II

In Washington.—Told to Go Home.—Senator Briggs, of New York.—The Interviews with President Fillmore.—Reversal of the Removal Order.—The Trip Home.—Treaty of 1854 and the Reservations.—The Mile Square.—The Blinding. »

After a fey days more in New York City I had raised the necessary funds to redeem the trinkets pledged with the ‘bus driver and to pay my hotel bills, etc., and on the 22d day of June, 1852, we had the good fortune to arrive in Washington.

“Washington Delegation, June 22, 1852“

Engraved from an unknown photograph by Marr and Richards Co. for Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians. Chief Buffalo, his speaker Oshogay, Vincent Roy, Jr., two other La Pointe Band members, and Armstrong are assumed to be in this engraving.

I took my party to the Metropolitan Hotel and engaged a room on the first floor near the office for the Indians, as they said they did not like to get up to high in a white man’s house. As they required but a couple mattresses for their lodgings they were soon made comfortable. I requested the steward to serve their meals in their room, as I did not wish to take them into the dining room among distinguished people, and their meals were thus served.

Undated postcard of the Metropolitan Hotel, formerly known as Brown’s India Queen Hotel.

~ StreetsOfWashington.com

The morning following our arrival I set out in search of the Interior Department of the Government to find the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to request an interview with him, which he declined to grant and said :

“I want you to take your Indians away on the next train west, as they have come here without permission, and I do not want to see you or hear of your Indians again.”

I undertook to make explanations, but he would not listen to me and ordered me from his office. I went to the sidewalk completely discouraged, for my present means was insufficient to take them home. I paced up and down the sidewalk pondering over what was best to do, when a gentleman came along and of him I inquired the way to the office of the Secretary of the Interior. He passed right along saying,

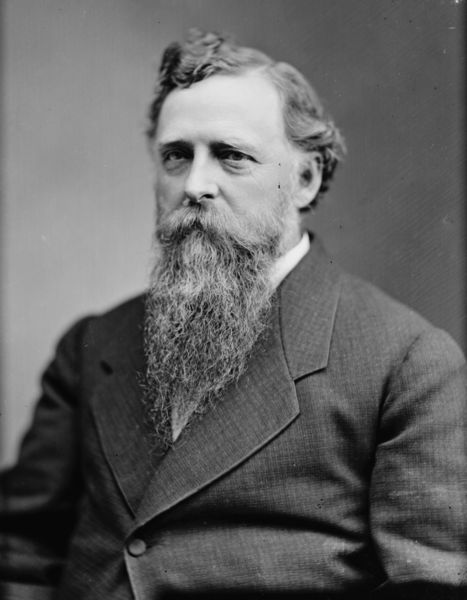

Secretary of the Interior

Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart

~ Department of the Interior

“This way, sir; this way, sir;” and I followed him.

He entered a side door just back of the Indian Commissioner’s office and up a short flight of stairs, and going in behind a railing, divested himself of hat and cane, and said :

“What can I do for you sir.”

I told him who I was, what my party consisted of, where we came from and the object of our visit, as briefly as possible. He replied that I must go and see the Commissioner of Indian Affairs just down stairs. I told him I had been there and the treatment I had received at his hands, then he said :

“Did you have permission to come, and why did you not go to your agent in the west for permission?”

I then attempted to explain that we had been to the agent, but could get no satisfaction; but he stopped me in the middle of my explanation, saying :

“I can do nothing for you. You must go to the Indian Commissioner,”

and turning, began a conversation with his clerk who was there when we went in.

I walked out more discouraged than ever and could not imagine what next I could do. I wandered around the city and to the Capitol, thinking I might find some one I had seen before, but in this I failed and returned to the hotel, where, in the office I found Buffalo surrounded by a crowd who were trying to make him understand them and among them was the steward of the house. On my entering the office and Buffalo recognizing me, the assemblage, seeing I knew him, turned their attention to me, asking who he was, etc., to all of which questions I answered as briefly as possible, by stating that he was the head chief of of the Chippewas of the Northwest. The steward then asked:

“Why don’t you take him into the dining room with you? Certainly such a distinguished man as he, the head of the Chippewa people, should have at least that privilege.”

United States Representative George Briggs

~ Library of Congress

I did so and as we passed into the dining room we were shown to a table in one corner of the room which was unoccupied. We had only been seated a few moments when a couple of gentlemen who had been occupying seats in another part of the dining room came over and sat at our table and said that if there were no objections they would like to talk with us. They asked about the party, where from, the object of the visit, etc. I answered them briefly, supposing them to be reporters and I did not care to give them too much information. One of these gentlemen asked what room we had, saying that himself and one or two others would like to call on us right after dinner. I directed them where to come and said I would be there to meet them.

About 2 o’clock they came, and then for the first time I knew who those gentlemen were. One was Senator Briggs, of New York, and the others were members of President Filmore’s cabinet, and after I had told them more fully what had taken me there, and the difficulties I had met with, and they had consulted a little while aside. Senator Briggs said :

“We will undertake to get you and your people an interview with the President, and will notify you here when a meeting can be arranged. ”

During the afternoon I was notified that an interview had been arranged for the next afternoon at 3 o’clock. During the evening Senator Briggs and other friends called, and the whole matter was talked over and preparations made for the interview the following day, which were continued the next day until the hour set for the interview.

United States President

Millard Fillmore.

~ Library of Congress

When we were assembled Buffalo’s first request was that all be seated, as he had the pipe of peace to present, and hoped that all who were present would partake of smoke from the peace pipe. The pipe, a new one brought for the purpose, was filled and lighted by Buffalo and passed to the President who took two or three draughts from it, and smiling said, “Who is the next?” at which Buffalo pointed out Senator Briggs and desired he should be the next. The Senator smoked and the pipe was passed to me and others, including the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Secretary of the Interior and several others whose names I did not learn or cannot recall. From them, to Buffalo, then to O-sho-ga, and from him to the four braves in turn, which completed that part of the ceremony. The pipe was then taken from the stem and handed to me for safe keeping, never to be used again on any occasion. I have the pipe still in my possession and the instructions of Buffalo have been faithfully kept. The old chief now rose from his seat, the balance following his example and marched in single file to the President and the general hand-shaking that was began with the President was continued by the Indians with all those present. This over Buffalo said his under chief, O-sha-ga, would state the object of our visit and he hoped the great father would give them some guarantee that would quiet the excitement in his country and keep his young men peaceable. After I had this speech thoroughly interpreted, O-sha-ga began and spoke for nearly an hour. He began with the treaty of 1837 and showed plainly what the Indians understood the treaty to be. He next took up the treaty of 1842 and said he did not understand that in either treaty they had ceded away the land and he further understood in both cases that the Indians were never to be asked to remove from the lands included in those treaties, provided they were peaceable and behaved themselves and this they had done. When the order to move came Chief Buffalo sent runners out in all directions to seek for reasons and causes for the order, but all those men returned without finding a single reason among all the Superior and Mississippi Indians why the great father had become displeased. When O-sha-ga had finished his speech I presented the petition I had brought and quickly discovered that the President did recognize some names upon it, which gave me new courage. When the reading and examination of it had been concluded the meeting was adjourned, the President directing the Indian Commissioner to say to the landlord at the hotel that our hotel bills would be paid by the government. He also directed that we were to have the freedom of the city for a week.

Read Biographical Sketch of Vincent Roy, Jr. manuscript for a different perspective on their meeting the President.

The second day following this Senator Briggs informed me that the President desired another interview that day, in accordance with which request we went to the White House soon after dinner and meeting the President, he told the, delegation in a brief speech that he would countermand the removal order and that the annuity payments would be made at La Pointe as before and hoped that in the future there would be no further cause for complaint. At this he handed to Buffalo a written instrument which he said would explain to his people when interpreted the promises he had made as to the removal order and payment of annuities at La Pointe and hoped when he had returned home he would call his chiefs together and have all the statements therein contained explained fully to them as the words of their great father at Washington.

The reader can imagine the great load that was then removed from my shoulders for it was a pleasing termination of the long and tedious struggle I had made in behalf of the untutored but trustworthy savage.

On June 28th, 1852, we started on our return trip, going by cars to La Crosse, Wis., thence by steamboat to St. Paul, thence by Indian trail across the country to Lake Superior. On our way from St. Paul we frequently met bands of Indians of the Chippewa tribe to whom we explained our mission and its results, which caused great rejoicing, and before leaving these bands Buffalo would tell their chief to send a delegation, at the expiration of two moons, to meet him in grand council at La Pointe, for there was many things he wanted to say to them about what he had seen and the nice manner in which he had been received and treated by the great father.

At the time appointed by Buffalo for the grand council at La Pointe, the delegates assembled and the message given Buffalo by President Filmore was interpreted, which gave the Indians great satisfaction. Before the grand council adjourned word was received that their annuities would be given to them at La Pointe about the middle of October, thus giving them time to get together to receive them. A number of messengers was immediately sent out to all parts of the territory to notify them and by the time the goods arrived, which was about October 15th, the remainder of the Indians had congregated at La Pointe. On that date the Indians were enrolled and the annuities paid and the most perfect satisfaction was apparent among all concerned. The jubilee that was held to express their gratitude to the delegation that had secured a countermanding order in the removal matter was almost extravagantly profuse. The letter of the great father was explained to them all during the progress of the annuity payments and Chief Buffalo explained to the convention what he had seen; how the pipe of peace had been smoked in the great father’s wigwam and as that pipe was the only emblem and reminder of their duties yet to come in keeping peace with his white children, he requested that the pipe be retained by me. He then went on and said that there was yet one more treaty to be made with the great father and he hoped in making it they would be more careful and wise than they had heretofore been and reserve a part of their land for themselves and their children. It was here that he told his people that he had selected and adopted, me as his son and that I would hereafter look to treaty matters and see that in the next treaty they did not sell them selves out and become homeless ; that as he was getting old and must soon leave his entire cares to others, he hoped they would listen to me as his confidence in his adopted son was great and that when treaties were presented for them to sign they would listen to me and follow my advice, assuring them that in doing so they would not again be deceived.

Map of Lake Superior Chippewa territories ceded in 1836, 1837, 1842, and 1854.

~ Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission

After this gathering of the Indians there was not much of interest in the Indian country that I can recall until the next annual payment in 1853. This payment was made at La Pointe and the Indians had been notified that commissioners would be appointed to make another treaty with them for the remainder of their territory. This was the territory lying in Minnesota west of Lake Superior; also east and west of the Mississippi river north to the territory belonging to the Boisfort and Pillager tribe, who are a part of the Chippewa nation, but through some arrangement between themselves, were detached from the main or more numerous body. It was at this payment that the Chippewa Indians proper desired to have one dollar each taken from their annuities to recompense me for the trouble and expense I had been to on the trip to Washington in their behalf, but I refused to accept it by reason of their very impecunious condition.

It was sometime in August, 1854, before the commissioners arrived at LaPointe to make the treaty and pay the annuities of that year. Messengers were despatched to notify all Indians of the fact that the great father had sent for them to come to La Pointe to get their money and clothing and to meet the government commissioners who wished to make another treaty with them for the territory lying west of Lake Superior and they were further instructed to have the Indians council among themselves before starting that those who came could be able to tell the wishes of any that might remain away in regards to a further treaty and disposition of their lands. Representatives came from all parts of the Chippewa country and showed a willingness to treat away the balance of their country. Henry C. Gilbert, the Indian agent at La Pointe, formerly of Ohio, and David B. Herriman, the agent for the Chippewas of the Mississippi country, were the commissioners appointed by the government to consumate this treaty.

While we were waiting the arrival of the interior Indians I had frequent talks with the commissioners and learned what their instructions were and about what they intended to offer for the lands which information I would communicate to Chief Buffalo and other head men in our immediate vicinity, and ample time was had to perfect our plans before the others should arrive, and when they did put in an appearance we were ready to submit to them our views for approval or rejection. Knowing as I did the Indians’ unwillingness to give up and forsake their old burying grounds I would not agree to any proposition that would take away the remainder of their lands without a reserve sufficient to afford them homes for themselves and posterity, and as fast as they arrived I counselled with them upon this subject and to ascertain where they preferred these reserves to be located. The scheme being a new one to them it required time and much talk to get the matter before them in its proper light. Finally it was agreed by all before the meeting of the council that no one would sign a treaty that did not give them reservations at different points of the country that would suit their convenience, that should afterwards be considered their bona-fide home. Maps were drawn of the different tracts that had been selected by the various chiefs for their reserve and permanent home. The reservations were as follows :

One at L’Anse Bay, one at Ontonagon, one at Lac Flambeau, one at Court O’Rilles, one at Bad River, one at Red Cliff or Buffalo Bay, one at Fond du Lac, Minn., and one at Grand Portage, Minn.

Joseph Stoddard (photo c.1941) worked on the 1854 survey of the Bad River Reservation exterior boundaries, and shared a different perspective about these surveys.

~ Bad River Tribal Historic Preservation Office

The boundaries were to be as near as possible by metes and bounds or waterways and courses. This was all agreed to by the Lake Superior Indians before the Mississippi Chippewas arrived and was to be brought up in the general council after they had come in, but when they arrived they were accompanied by the American Fur Company and most of their employees, and we found it impossible to get them to agree to any of our plans or to come to any terms. A proposition was made by Buffalo when all were gathered in council by themselves that as they could not agree as they were, a division should be drawn, dividing the Mississippi and the Lake Superior Indians from each other altogether and each make their own treaty After several days of counselling the proposition was agreed to, and thus the Lake Superiors were left to make their treaty for the lands mouth of Lake Superior to the Mississippi and the Mississippis to make their treaty for the lands west of the Mississippi. The council lasted several days, as I have stated, which was owing to the opposition of the American Fur Company, who were evidently opposed to having any such division made ; they yielded however, but only when they saw further opposition would not avail and the proposition of Buffalo became an Indian law. Our side was now ready to treat with the commissioners in open council. Buffalo, myself and several chiefs called upon them and briefly stated our case but were informed that they had no instructions to make any such treaty with us and were only instructed to buy such territory as the Lake Superiors and Mississippis then owned. Then we told them of the division the Indians had agreed upon and that we would make our own treaty, and after several days they agreed to set us off the reservations as previously asked for and to guarantee that all lands embraced within those boundaries should belong to the Indians and that they would pay them a nominal sum for the remainder of their possessions on the north shores. It was further agreed that the Lake Superior Indians should have two- thirds of all money appropriated for the Chippewas and the Mississippi contingent the other third. The Lake Superior Indians did not seem, through all these councils, to care so much for future annuities either in money or goods as they did for securing a home for themselves and their posterity that should be a permanent one. They also reserved a tract of land embracing about 100 acres lying across and along the Eastern end of La Pointe or Madeline Island so that they would not be cut off from the fishing privilege.

It was about in the midst of the councils leading up to the treaty of 1854 that Buffalo stated to his chiefs that I had rendered them services in the past that should be rewarded by something more substantial than their thanks and good wishes, and that at different times the Indians had agreed to reward me from their annuity money but I had always refused such offers as it would be taking from their necessities and as they had had no annuity money for the two years prior to 1852 they could not well afford to pay me in this way.

“And now,” continued Buffalo, “I have a proposition to make to you. As he has provided us and our children with homes by getting these reservations set off for us, and as we are about to part with all the lands we possess, I have it in my power, with your consent, to provide him with a future home by giving him a piece of ground which we are about to part with. He has agreed to accept this as it will take nothing from us and makes no difference with the great father whether we reserve a small tract of our territory or not, and if you agree I will proceed with him to the head of the lake and there select the piece of ground I desire him to have, that it may appear on paper when the treaty has been completed.”

The chiefs were unanimous in their acceptance of the proposition and told Buffalo to select a large piece that his children might also have a home in future as has been provided for ours.

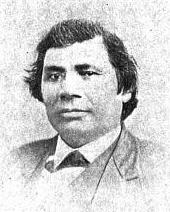

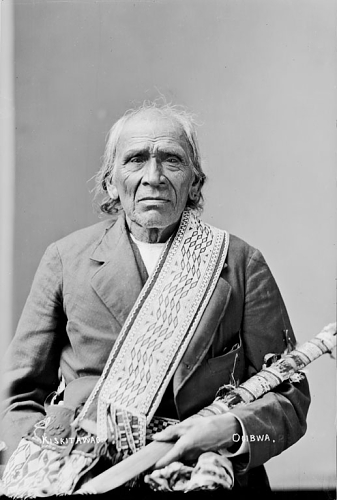

Kiskitawag (Giishkitawag: “Cut Ear”) signed earlier treaties as a warrior of the Ontonagon Band and became associated with the La Pointe Band at Odanah.

~C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections

This council lasted all night and just at break of day the old chief and myself, with four braves to row the boat, set out for the head of Lake Superior and did not stop anywhere only long enough to make and drink some tea, until we reached the head of St. Louis Bay. We landed our canoe by the side of a flat rock quite a distance from the shore, among grass and rushes. Here we ate our lunch and when completed Buffalo and myself, with another chief, Kish-ki-to-uk, waded ashore and ascended the bank to a small level plateau where we could get a better view of the bay. Here Buffalo turned to me, saying: .

“Are you satisfied with this location? I want to reserve the shore of this bay from the mouth of St. Louis river. How far that way do you you want it to go?” pointing southeast, or along the south shore of the lake.

I told him we had better not try to make it too large for if we did the great father’s officers at Washington might throw it out of the treaty and said:

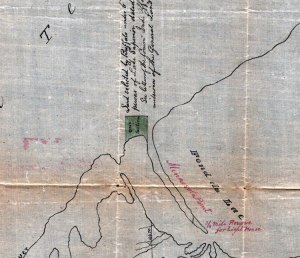

“I will be satisfied with one mile square, and let it start from the rock which we have christened Buffalo rock, running easterly in the direction of Minnesota Point, taking in a mile square immediately northerly from the head of St. Louis Bay”

As there was no other way of describing it than by metes and bounds we tried to so describe it in the treaty, but Agent Gilbert, whether by mistake or not I am unable to say, described it differently. He described it as follows: “Starting from a rock immediately above and adjoining Minnesota Point, etc.”

We spent an hour or two here in looking over the plateau then went back to our canoe and set out for La Pointe. We traveled night and day until we reached home.

During our absence some of the chiefs had been talking more or less with the commissioners and immediately on our return all the Indians met in a grand council when Buffalo explained to them what he had done on the trip and how and where he had selected the piece of land that I was to have reserved in the treaty for my future home and in payment for the services I had rendered them in the past. The balance of the night was spent in preparing ourselves for the meeting with the treaty makers the next day, and about 10 o’clock next morning we were in attendance before the commissioners all prepared for a big council.

Agent Gilbert started the business by beginning a speech interpreted by the government interpreter, when Buffalo interrupted him by saying that he did not want anything interpreted to them from the English language by any one except his adoped son for there had always been things told to the Indians in the past that proved afterwards to be untrue, whether wrongly interpreted or not, he could not say;

“and as we now feel that my adopted son interprets to us just what you say, and we can get it correctly, we wish to hear your words repeated by him, and when we talk to you our words can be interpreted by your own interpreter, and in this way one interpreter can watch the other and correct each other should there be mistakes. We do not want to be deceived any more as we have in the past. We now understand that we are selling our lands as well as the timber and that the whole, with the exception of what we shall reserve, goes to the great father forever.”

Commissioner of Indian affairs. Col. Manypenny, then said to Buffalo:

“What you have said meets my own views exactly and I will now appoint your adopted son your interpreter and John Johnson, of Sault Ste. Marie, shall be the interpreter on the part of the government,” then turning to the commissioners said, “how does that suit you, gentlemen.”

They at once gave their consent and the council proceeded.

Buffalo informed the commissioners of what he had done in regard to selecting a tract of land for me and insisted that it become a part of the treaty and that it should be patented to me directly by the government without any restrictions. Many other questions were debated at this session but no definite agreements were reached and the council was adjourned in the middle of the afternoon. Chief Buffalo asking for the adjournment that he might talk over some matters further with his people, and that night the subject of providing homes for their half-breed relations who lived in different parts of the country was brought up and discussed and all were in favor of making such a provision in the treaty. I proposed to them that as we had made provisions for ourselves and children it would be only fair that an arrangement should be made in the treaty whereby the government should provide for our mixed blood relations by giving to each person the head of a family or to each single person twenty-one years of age a piece of land containing at least eighty acres which would provide homes for those now living and in the future there would be ample room on the reservations for their children, where all could live happily together. We also asked that all teachers and traders in the ceded territory who at that time were located there by license and doing business by authority of law, should each be entitled to 160 acres of land at $1.25 per acre. This was all reduced to writing and when the council met next morning we were prepared to submit all our plans and requests to the commissioners save one, which we required more time to consider. Most of this day was consumed in speech-making by the chiefs and commissioners and in the last speech of the day, which was made by Mr. Gilbert, he said:

“We have talked a great deal and evidently understand one another. You have told us what you want, and now we want time to consider your requests, while you want time as you say to consider another matter, and so we will adjourn until tomorrow and we, with your father. Col. Manypenny, will carefully examine and consider your propositions and when we meet to-morrow we will be prepared to answer you with an approval or rejection.”

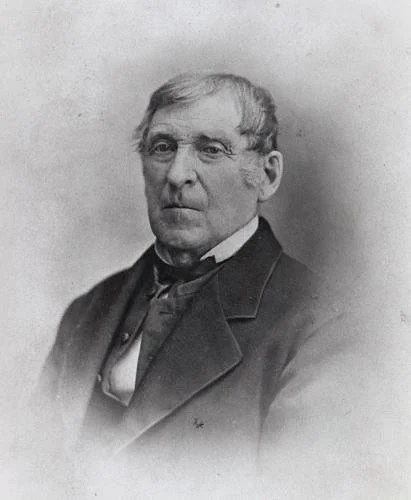

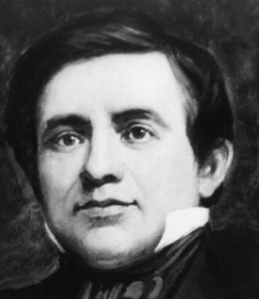

Julius Austrian purchased the village of La Pointe and other interests from the American Fur Company in 1853. He entered his Town Plan of La Pointe on August 29th of 1854. He was the highest paid claimant of the 1854 Treaty at La Pointe. His family hosted the 1855 Annuity Payments at La Pointe.

~ Photograph of Austrian from the Madeline Island Museum

That evening the chiefs considered the other matter, which was to provide for the payment of the debts of the Indians owing the American Fur Company and other traders and agreed that the entire debt could not be more than $90,000 and that that amount should be taken from the Indians in bulk and divided up among their creditors in a pro-rata manner according to the amount due to any person or firm, and that this should wipe out their indebtedness. The American Fur Company had filed claims which, in the aggregate, amounted to two or three times this sum and were at the council heavily armed for the purpose of enforcing their claim by intimidation. This and the next day were spent in speeches pro and con but nothing was effected toward a final settlement.

Col. Manypenny came to my store and we had a long private interview relating to the treaty then under consideration and he thought that the demands of the Indians were reasonable and just and that they would be accepted by the commissioners. He also gave me considerable credit for the manner in which I had conducted the matter for Indians, considering the terrible opposition I had to contend with. He said he had claims in his possession which had been filed by the traders that amounted to a large sum but did not state the amount. As he saw the Indians had every confidence in me and their demands were reasonable he could see no reason why the treaty could not be speedily brought to a close. He then asked if I kept a set of books. I told him I only kept a day book or blotter showing the amount each Indian owed me. I got the books and told him to take them along with him and that he or his interpreter might question any Indian whose name appeared thereon as being indebted to me and I would accept whatever that Indian said he owed me whether it be one dollar or ten cents. He said he would be pleased to take the books along and I wrapped them up and went with him to his office, where I left them. He said he was certain that some traders were making claims for far more than was due them. Messrs. Gilbert and Herriman and their chief clerk, Mr. Smith, were present when Mr. Manypenny related the talk he had with me at the store. He considered the requests of the Indians fair and just, he said, and he hoped there would be no further delays in concluding the treaty and if it was drawn up and signed with the stipulations and agreements that were now understood should be incorporated in it, he would strongly recommend its ratification by the President and senate.

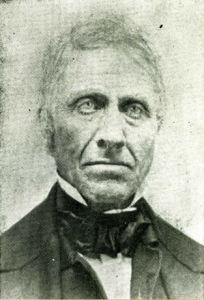

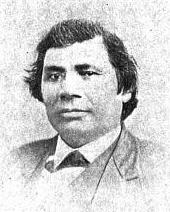

Naagaanab of Fond Du Lac

~ Minnesota Historical Society

The day following the council was opened by a speech from Chief Na-gon-ab in which he cited considerable history.

“My friends,” he said, “I have been chosen by our chief, Buffalo, to speak to you. Our wishes are now on paper before you. Before this it was not so. We have been many times deceived. We had no one to look out for us. The great father’s officers made marks on paper with black liquor and quill. The Indian can not do this. We depend upon our memory. We have nothing else to look to. We talk often together and keep your words clear in our minds. When you talk we all listen, then we talk it over many times. In this way it is always fresh with us. This is the way we must keep our record. In 1837 we were asked to sell our timber and minerals. In 1842 we were asked to do the same. Our white brothers told us the great father did not want the land. We should keep it to hunt on. Bye and bye we were told to go away; to go and leave our friends that were buried yesterday. Then we asked each other what it meant. Does the great father tell the truth? Does he keep his promises? We cannot help ourselves! We try to do as we agree in treaty. We ask you what this means? You do not tell from memory! You go to your black marks and say this is what those men put down; this is what they said when they made the treaty. The men we talk with don’t come back; they do not come and you tell us they did not tell us so! We ask you where they are? You say you do not know or that they are dead and gone. This is what they told you; this is what they done. Now we have a friend who can make black marks on paper When the council is over he will tell us what we have done. We know now what we are doing! If we get what we ask our chiefs will touch the pen, but if not we will not touch it. I am told by our chief to tell you this: We will not touch the pen unless our friend says the paper is all right.”

Na-gon-ab was answered by Commissioner Gilbert, saying:

“You have submitted through your friend and interpreter the terms and conditions upon which you will cede away your lands. We have not had time to give them all consideration and want a little more time as we did not know last night what your last proposition would be. Your father. Col. Manypenny, has ordered some beef cattle killed and a supply of provisions will be issued to you right away. You can now return to your lodges and get a good dinner and talk matters over among yourselves the remainder of the day and I hope you will come back tomorrow feeling good natured and happy, for your father, Col. Manypenny, will have something to say to you and will have a paper which your friend can read and explain to you.”

When the council met next day in front of the commissioners’ office to hear what Col. Manypenny had to say a general good feeling prevailed and a hand-shaking all round preceded the council, which Col. Manypenny opened by saying:

“My friends and children: I am glad to see you all this morning looking good natured and happy and as if you could sit here and listen to what I have to say. We have a paper here for your friend to examine to see if it meets your approval. Myself and the commissioners which your great father has sent here have duly considered all your requests and have concluded to accept them. As the season is passing away and we are all anxious to go to our families and you to your homes, I hope when you read this treaty you will find it as you expect to and according to the understandings we have had during the council. Now your friend may examine the paper and while he is doing so we will take a recess until afternoon.”

Chief Buffalo, turning to me, said:

“My son, we, the chiefs of all the country, have placed this matter entirely in your hands. Go and examine the paper and if it suits you it will suit us.”

Then turning to the chiefs, he asked,

“what do you all say to that?”

The ho-ho that followed showed the entire circle were satisfied.

I went carefully through the treaty as it had been prepared and with a few exceptions found it was right. I called the attention of the commissioners to certain parts of the stipulations that were incorrect and they directed the clerk to make the changes.

The following day the Indians told the commissioners that as their friend had made objections to the treaty as it was they requested that I might again examine it before proceeding further with the council. On this examination I found that changes had been made but on sheets of paper not attached to the body of the instrument, and as these sheets contained some of the most important items in the treaty, I again objected and told the commissioners that I would not allow the Indians to sign it in that shape and not until the whole treaty was re-written and the detached portions appeared in their proper places. I walked out and told the Indians that the treaty was not yet ready to sign and they gave up all further endeavors until next day. I met the commissioners alone in their office that afternoon and explained the objectionable points in the treaty and told them the Indians were already to sign as soon as those objections were removed. They were soon at work putting the instrument in shape.

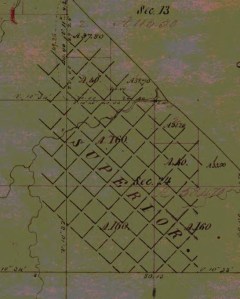

“One version of the boundaries for Chief Buffalo’s reservation is shown at the base of Minnesota Point in a detail from an 1857 map preserved in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Other maps show a larger and more irregularly shaped versions of the reservation boundary, though centered on the same area.”

~ DuluthStories.net

The next day when the Indians assembled they were told by the commissioners that all was ready and the treaty was laid upon a table and I found it just as the Indians had wanted it to be, except the description of the mile square. The part relating to the mile square that was to have been reserved for me read as follows:

“Chief Buffalo, being desirous of providing for some of his relatives who had rendered them important services, it is agreed that he may select one mile square of the ceded territory heretofore described.”

“Now,” said the commissioner,

“we want Buffalo to designate the person or persons to whom he wishes the patents to issue.”

Buffalo then said:

“I want them to be made out in the name of my adopted son.”

This closed all ceremony and the treaty was duly signed on the 30th day of September, 1854. This done the commissioners took a farewell shake of the hand with all the chiefs, hoping to meet them again at the annuity payment the coming year. They then boarded the steamer North Star for home. In the course of a few days the Indians also disappeared, some to their interior homes and some to their winter hunting grounds and a general quiet prevailed on the island.

Portrait of the Steamer North Star from American Steam Vessels, by Samuel Ward Stanton, page 40.

~ Wikimedia.org

About the second week in October, 1854, I went from La Pointe to Ontonagon in an open boat for the purpose of purchasing my winter supplies as it had got too late to depend on getting them from further below. While there a company was formed for the purpose of going into the newly ceded territory to make claims upon lands that would be subject to entry as soon as the late treaty should be ratified. The company consisted of Samuel McWaid, William Whitesides, W. W. Kingsbury, John Johnson, Oliver Melzer, John McFarland, Daniel S. Cash, W. W. Spaulding, all of Ontonagon, and myself. The two last named gentlemen, Daniel S. Cash and W. W. Spaulding, agreeing to furnish the company with supplies and all necessaries, including money, to enter the lands for an equal interest and it was so stipulated that we were to share equally in all that we, or either of us, might obtain. As soon as the supplies could be purchased and put aboard the schooner Algonquin we started for the head of the lake, stopping at La Pointe long enough for me to get my family aboard and my business matters arranged for the winter. I left my store at La Pointe in charge of Alex. Nevaux, and we all sailed for the head of Lake Superior, the site of which is now the city of Duluth. Reaching there about the first week in December—the bay of Superior being closed by ice—we were compelled to make our landing at Minnesota Point and take our goods from there to the main land on the north’ shore in open boats, landing about one and-one half miles east of Minnesota Point at a place where I desired to make a preemption for myself and to establish a trading post for the winter. Here I erected a building large enough for all of us to live in, as we expected to make this our headquarters for the winter, and also a building for a trading post. The other members of the company made claims in other places, but I did no more land looking that winter.

Detail of Superior City townsite at the head of Lake Superior from the 1854 U.S. General Land Office survey by Stuntz and Barber.

About January 20th, 1855, I left my place at the head of the lake to go back to La Pointe and took with me what furs I had collected up to that time, as I had a good place at La Pointe to dry and keep them. I took four men along to help me through and two dog trains. As we were passing down Superior Bay and when just in front of the village of West Superior a man came to us on the ice carrying a small bundle on his back and asked me if I had any objections to his going through in my company. He said the snow was deep and the weather cold and it was bad for one man to travel alone. I told him I had no objections provided he would take his turn with the other men in breaking the road for the dogs. We all went on together and camped that night at a place well known as Flag River. We made preparations for a cold night as the thermometer must have been twenty-five or thirty degrees below zero and the snow fully two feet deep. As there were enough of us we cut and carried up a large quantity of wood, both green and dry, and shoveled the snow away to the ground with our snow shoes and built a large fire. We then cut evergreen boughs and made a wind break or bough camp and concluded we could put in a very comfortable night. We then cooked and ate our supper and all seemed happy. I unrolled a bale of bear skins and spread them out on the ground for my bed, filled my pipe and lay down to rest while the five men with me were talking and smoking around the camp fire. I was very tired and presume I was not long in falling asleep. How long I slept I cannot tell, but was awakened by something dropping into my face, which felt like a powdered substance. I sprang to my feet for I found something had got into my eyes and was smarting them badly. I rushed for the snow bank that was melting from the heat and applied handful after handful to my eyes and face. I found the application was peeling the skin off my face and the pain soon became intense. I woke up the crew and they saw by the firelight the terrible condition I was in. In an hour’s time my eyeballs were so swollen that I could not close the lids and the pain did not abate. I could do nothing more than bathe my eyes until morning, which I did with tea-grounds. It seemed an age before morning came and when it did come I could not realize it, for I was totally blind. The party started with me at early dawn for La Pointe. The man who joined us the day before went no further, but returned to Superior, which was a great surprise to the men of our party, who frequently during the day would say:

“There is something about this matter that is not right,”

and I never could learn afterward of his having communicated the fact of my accident to any one or to assign any reason or excuse for turning back, which caused us to suspect that he had a hand in the blinding, but as I could get no proof to establish that suspicion, I could do nothing in the matter. This man was found dead in his cabin a few months afterwards.

At La Pointe I got such treatment as could be procured from the Indians which allayed the inflamation but did not restore the sight. I remained at La Pointe about ten days, and then returned home with dog train to my family, where I remained the balance of the winter, when not at Superior for treatment. When the ice moved from the lake in the spring I abandoned everything there and returned to La Pointe and was blind or nearly so until the winter of 1861.

Returning a little time to the north shore I wish to relate an incident of the death of one of our Ontonagon company. Two or three days after I had reached home from La Pointe, finding my eyes constantly growing worse I had the company take me to Superior where I could get treatment. Dr. Marcellus, son of Prof. Marcellus, of an eye infirmary in Philadelphia, who had just then married a beautiful young wife, and come west to seek his fortune, was engaged to treat me. I was taken to the boarding house of Henry Wolcott, where I engaged rooms for the winter as I expected to remain there until spring. I related to the doctor what had befallen me and he began treatment. At times I felt much better but no permanent relief seemed near. About the middle February my family required my presence at home, as there was some business to be attended to which they did not understand. My wife sent a note to me by Mr. Melzer, stating that it was necessary for me to return, and as the weather that day was very pleasant, she hoped that I would come that afternoon. Mr. Melzer delivered me the note, which I requested him to read. It was then 11 a. m. and I told him we would start right after dinner, and requested him to tell the doctor that I wished to see him right away, and then return and get his dinner, as it would be ready at noon, to which he replied:

“If I am not here do not wait for me, but I will be here at the time you are ready for home.”

Mr. Melzer did return shortly after we had finished our dinner and I requested him to eat, as I would not be ready to start for half an hour, but he insisted he was not hungry. We had no conveyance and at 1 p. m. we set out for home. We went down a few steps to the ice, as Mr. Wolcott’s house stood close to the shore of the bay, and went straight across Superior Bay to Minnesota Point, and across the point six or eight rods and struck the ice on Lake Superior. A plain, hard beaten road led from here direct to my home. After we had proceeded about 150 yards, following this hard beaten road, Melzer at once stopped and requested me to go ahead, as I could follow the beaten road without assistance, the snow being deep on either side.

“Now,” he says go ahead, for I must go back after a drink.”

I followed the road quite well, and when near the house my folks came out to meet me, their first inquiry being:

“Where is Melzer?”

I told them the circumstances of his turning back for a drink of water. Reaching the bank on which my house stood, some of my folks, looking back over the road I had come, discovered a dark object apparently floundering on the ice. Two or three of our men started for the spot and there found the dead body of poor Melzer. We immediately notified parties in Superior of the circumstances and ordered a post-mortem examination of the body. The doctors found that his stomach was entirely empty and mostly gone from the effects of whisky and was no thicker than tissue paper and that his heart had burst into three pieces. We gave him a decent burial at Superior and peace to his ashes, His last act of kindness was in my behalf.

To be continued in Chapter III…

Among The Otchipwees: I

May 28, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 2 December 1884

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 86-91.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

Like all the northern tribes, the Chippewas are known by a variety of names. The early French called them Sauteus, meaning people of the Sault. Later missionaries and historians speak of them as Ojibways, or Odjibwes. By a corruption of this comes the Chippewa of the English.

“No-tin” copied from 1824 Charles Bird King original by Henry Inman in 1832-33. Noodin (Wind) was a prominent Chippewa chief from the St. Croix country.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

On the south of the Chippewas, in 1832, across the Straits of Mackinaw, were the Ottawas. Some of this nation were found by Champlain on the Ottawa River of Canada, whom he called Ottawawas. In later years there were some of them on Lake Superior, of whom it is probable the Lake Court Oreille band, in northwestern Wisconsin, is a remainder. The French call them “Court Oreillés,”, or short ears. All combined, it is not a powerful nation. Many of them pluck the hair from a large part of the scalp, leaving only a scalp lock. This custom they explain as a concession to their enemies, in order to make a more neat and rapid job of the scalping process. A thick head of coarse hair, they say, is a great impediment. Probably the true reason is a notion of theirs that a scalp lock is ornamental. The practice is not universal among Ottawas, and is not common with the neighboring tribes. These were the people who committed the massacre of the English garrison at Old Mackinaw, in 1763.

![Mah-kée-mee-teuv, Grizzly Bear, Chief of the [Menominee] Tribe by George Catlin, 1831. ~ Smithsonian Institute](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/1831-mah-kee-mee-teuv-grizzly-bear-by-george-catlin.jpg?w=230)

“Mah-kée-mee-teuv, Grizzly Bear, Chief of the [Menominee] Tribe” by George Catlin, 1831.

~ Smithsonian Institute

The Oneidas, a small remnant of that nation, from New York, were located on Duck River, near Fort Howard, and the Tuscaroras on the south shore of Lake Winnebago.

Detail from “Among The Winnebago [Ho-Chunk] Indians. Wah-con-ja-z-gah (Yellow Thunder) Warrior chief 120 y’s old” stereograph by Henry Hamilton Bennett, circa 1870s.

~ J. Paul Getty Museum

Plaster life cast of Sac leader Black Hawk (Makatai Meshe Kiakiak) reproduced by Bill Whittaker (original was made circa 1830) on display at Black Hawk State Historic Site.

~ Wikipedia.org

Next to the Menominees on the west were the Winnebagoes, a barbarous, warlike and treacherous people, even for Indians. Their northern border joined the Chippewas. Yellow Thunder’s village, in 1832, was on the trail from Lake Winnebago to Fort Winnebago, south of the Fox River about half way. He was more of a prophet, medicine man or priest, than warrior. In the Black Hawk war man of the Winnebago bucks joined the Sacs and the Foxes. Only four years before the United States was obliged to send an expedition against them, and to build a stockade at the portage. Their chiefs, old men, and medicine men, professed to be very friendly to us, but kept up constant communications with Black Hawk. When he was beaten at the Bad Ax River, and his warriors dispersed, they followed the old chief into the northern forest, captured him, and delivered him to the United States forces.

One of the causes of the Black Hawk War in 1832 was the murder of a party of Menominees near Fort Crawford, by the Sacs and Foxes. There was an ancient feud between those tribes which implies a series of scalping parties from generation to generation.

Sac leader “Ke-o-kuk or the Watchful Fox” by Thomas M. Easterly, 1847.

~ Missouri History Museum

As the Menominees were at peace with the United States, and their camps were near the garrison, they were considered to have been under Federal protection, and their murder as an insult to its authority. The return of Keokuk’s band to the Rock River country brought on a crisis in the month of May. The Menominees were anxious to avenge themselves, but were quieted by the promise of the government that the Sacs and Foxes should be punished. They offered to accompany our troops as scouts or spies, which was not accepted until the month of July, when Black Hawk had returned to the Four Lakes, where is now the city of Madison.

On a bright afternoon, about the middle of the month, a company of Menominee warriors emerged in single file from the woods in rear of Fort Howard at the head of Green Bay. They numbered about seventy-five, each one with a gun in his right hand, a blanket over his right shoulder, held across the breast by the naked left arm, and a tomahawk. Around the waist was a belt, on which was a pouch and a sheath, with a scalping knife. Their step was high and elastic, according to the custom of the men of the woods. On their faces was an excess of black paint, made more hideous by streaks of red. Their coarse black hair was decorated with all the ribbons and feathers at their command. Some wore moccasins and leggings of deer skin, but a majority were barefooted and barelegged. They passed across the common to the ferry, where they were crossed to Navarino, and marched to the Indian Agency at Shantytown. Here they made booths of the branches of trees. Captain or Colonel Hamilton, a son of Alexander Hamilton, was their commander. As they had an abundance to eat and were filled with martial prowess, they were exceedingly jubilant.

“A view of the Butte des Morts treaty ground with the arrival of the commissioners Gov. Lewis Cass and Col. McKenney in 1827” by James Otto Lewis, 1835.

~ Library of Congress

Their march was up the valley of the river, recrossing above Des Peres, passing the great Kakolin, and the Big Butte des Morts to the present site of Oshkosh. Thence crossing again they followed the trail to the Winnebago villages, past the Apukwa or Rice lakes to Fort Winnebago, making about twenty miles a day. On the route they were inclined to straggle, presenting nothing of military aspect except a uniform of dirty blankets. Colonel Hamilton was not able to make them stand guard, or to send out regular pickets. They were expert scouts in the day time, but at night lay down to sleep in security, trusting to their dogs, their keen sense of hearing and the great spirit. On the approach of day they were on the alert. It is a rule in Indian tactics to operate by surprises, and to attack at the first show of light in the morning.

From Fort Winnebago they moved to the Four Lakes, where Madison now is. Black Hawk had retired across the Wisconsin River, where there was a skirmish on the 21st of July, and the battle of the Bad Ax was being fought.

Photograph of Pierre Jean Édouard Desor (Swiss geologist and professor at Neuchâtel academy) from Wisconsin Historical Society. Desor and others were employed to survey for Report on the geology and topography of a portion of the Lake Superior Land District in the state of Michigan: Part I, Copper Lands; Part II, The Iron Region.

A few miles southwesterly of Waukedah, on the branch railroad to the iron mines of the upper Menominee, is a lake called by the Indians “Shope,” or Shoulder Lake, which I visited in the fall of 1850, in company with the late Edward Desor, a scientist of reputation in Switzerland. It discharges into the Sturgeon River, one of the eastern branches of the Menominee. There was a collection of half a dozen lodges, or wigwams, covered with bark, with a small field of corn, and the usual filth of an Indian village. The patriarch, or “chief” of that clan, came out to meet us, attended by about thirty men, women and children. By the traders he was called “Governor.” His nose was prominently Roman. He stood evenly on both feet, with his limbs bare below the knees. The right arm was also bare, and over the left shoulder was thrown a dirty blanket, covering the chest and the hips. A mass of coarse black hair covered the head, but was pushed away from the face. The usual dark, steady, snakelike, black eye of the race examined us with a piercing gaze. His face, with its large, well proportioned features, was almost grand. his pose was easy, unstudied and dignified, like one’s ideal of the Roman patrician of the time of Cicero, such as sculptors would select as a model.

This band were the Chippewas, but the coast of Green Bay was occupied by Menominees or Menomins, known to the French as “Folle Avoines,” or “Wild Rice” Indians, for which Menomin is the native name. Above the Twin Falls of the Menominee was an ancient village of Chippewas, called the “Bad Water” band, which is their name for a series of charming lakes not far distant, on the west of the river. They said their squaws, a long time since, were on the lakes in a bark canoe. Those on the land saw the canoe stand up on end, and disappear beneath the surface with all who were in it. “Very bad water.” From that time they were called the “Bad Water” lakes.

The Bad Water Band of Lake Superior Chippewa was first documented by Captain Thomas Jefferson Cram in his 1840 report to Congress.

~ Dickinson County Library