The 1856 Reservation for Chief Buffalo’s Estate

November 5, 2025

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

This is one of many posts on Chequamegon History exploring the original La Pointe Band Reservations of La Pointe County on Chequamegon Bay, now known as the Bad River and Red Cliff Reservations. Specifically, today’s post is about the 1856 Reservation for Chief Buffalo’s subdivision of the La Pointe Band and how it got selected in accordance with the Sixth Clause of the Second Article of the 1854 Treaty with the Chippewa at La Pointe:

1854 Treaty with the Chippewa at La Pointe

…

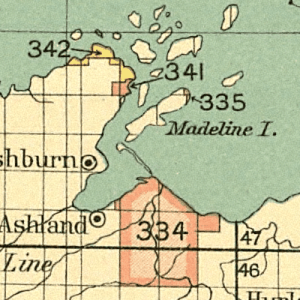

Map of La Pointe Band Reservations:

334 – Bad River Reservation

335 – La Pointe Fishing Reservation

341 – Chief Buffalo’s Reservation

342 – Red Cliff Reservation

18th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1896-’97

Printed by U.S. Congress in 1899

ARTICLE 2. The United States agree to set apart and withhold from sale, for the use of the Chippewas of Lake Superior, the following-described tracts of land, viz:

…

6th [Clause]. The Ontonagon band and that subdivision of the La Pointe band of which Buffalo is chief, may each select, on or near the lake shore, four sections of land, under the direction of the President, the boundaries of which shall be defined hereafter. And being desirous to provide for some of his connections who have rendered his people important services, it is agreed that the chief Buffalo may select one section of land, at such place in the ceded territory as he may see fit, which shall be reserved for that purpose, and conveyed by the United States to such person or persons as he may direct.

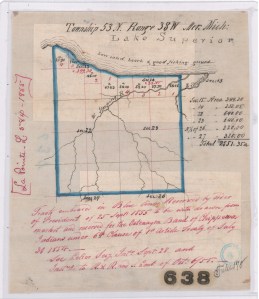

Map of “Tract embraced in blue lines reserved by order of President of 25 September 1855 to be withdrawn from market and reserved for the Ontonagon Band of Chippewa Indians“ on a “low sand beach & good fishing ground”.

Central Map File No. 638 (Tube No. 138)

NAID: 232923886 cites “La Pointe L.584-1855”.

The Ontonagon Band and Chief Buffalo’s Subdivision of the La Pointe Band got lumped together in this clause, so let’s review the Ontonagon Band first. Less than one year after the 1854 Treaty, the Ontonagon Band selected four square miles for their Reservation as approved by President Franklin Pierce’s Executive Order of September 25, 1855. Today the Ontonagon Band Reservation still has its original shape and size from 1855 despite heavy “checkerboarding” of its landownership over time.

In comparison to the Ontonagon Band Reservation, the history of how Chief Buffalo’s Reservation got selected is not so straightforward. Despite resisting and surviving the Sandy Lake Tragedy and Ojibwe Removal, making an epic trip to meet the President at Washington D.C., and securing Reservations as permanent homelands for the Chippewa Bands in the 1854 Treaty, Chief Buffalo of La Pointe died in 1855 before being able to select four square miles for his Subdivsion of the La Pointe Bands.

Fortunately, President Franklin Pierce’s Executive Order of February 21, 1856 withheld twenty-two square miles of land near the Apostle Islands from federal public land sales, allowing Chief Buffalo’s Estate to select four of those twenty-two square miles for their Reservation without competition from squatters and other land speculators, while other prime real estate in the ceded territory of La Pointe County was being surveyed and sold to private landowners by the United States General Land Office.

This 1856 Reservation of twenty-two square miles for Chief Buffalo’s Estate set the stage for what would eventually become the Red Cliff Reservation. We will return to this 1856 Reservation for Chief Buffalo’s Estate in several upcoming posts exploring more records about Red Cliff and the other La Pointe Band Reservations.

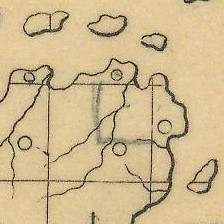

Maps marked “A” showing certain lands reserved by the 1854 Treaty:

Central Map File No. 793 (Tube 446)

NAID: 232924228 cites “La Pointe L.579-1855″.

Central Map File No. 816 (Tube 298)

NAIDs: 232924272 & 50926136 cites “Res. Chippewa L.516-1855”.

1878 Copy of President Franklin Pierce’s Executive Order of February 26, 1856 for Chief Buffalo’s Subdivision (aka “Red Cliff”).

NAID: 117092990

Office of Indian Affairs.

(Miscellaneous)

L.801.17.1878

Copy of Ex. Order of Feby. 21. 1856.

Chippewas (Red Cliff.)

Wisconsin.

Enc. in G.L.O. letter of Nov 23, 1878 (above file mark.)

in answer to office letter of Nov. 18, 1878.

Ex. Order File.

Department of the Interior

February 21, 1856

Sir,

I herewith return the diagram enclosed in your letter of the 20th inst, covering duplicates of documents which accompanied your letter of the 6th Sept. last, as well as a copy of the latter, the originals of which were submitted to the President in letter from the Department of the 8th Sept. last and cannot now be found.

You will find endorsements on said diagram explanatory of the case and an order of the President of this date for the withdrawal of the land in question for Indian purposes as recommended.

Respectfully

Your obt. Servt

R McClelland

Secretary

To

Hon Thos A Hendrick

Commissioner of the

General Land Office

(Copy)

General Land Office

September 6, 1855

Hon R. McClelland

Sec. of Interior

Sir:

Enclosed I have the honor to submit an abstract from the Acting Commissioner of Indian Affairs letter of the 5th instant, requesting the withdrawal of certain lands for the Chippewa Indians in Wisconsin, under the Treaty of September 30th, 1854, referred by the Department to this office on the 5th. instant, with orders to take immediate steps for the withdrawal of the lands from sale.

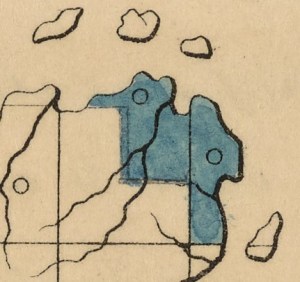

Detail of 1856 Reservation in pencil on “a map marked A.“

Central Map File No. 816 (Tube 298)

NAIDs: 232924272 & 50926136 cites “Res. Chippewa L.516-1855”.

In obedience to the above order I herewith enclose a map marked A. Showing by the blue shades thereon, the Townships and parts of Townships desired to be reserved, no portion of which are yet in market, to wit:

Township 51 N. of Range 3 West 4th Prin. Mer. Wis.

N.E. ¼ of Town 51 N ” 4 ” ” ” “.

Township 52 ” ” 3 & 4 ” ” ” “.

For the reservation of which, until the contemplated Selections under the 6th Clause of the Chippewa Treaty of 30th September 1854 can be made, I respectfully recommend that the order of the President may be obtained.

The requisite reports on the subject of the new surveys, and respecting preemption claims, referred to in the same order, will be prepared and communicated at an early day.

I am respectfully

Your Ob’t Serv’t

Thos. A. Hendricks

Commissioner

Department of the Interior

Feb. 20. 1856

Detail of 1856 Reservation in blue on “duplicate of the original“.

NAID: 117092990

This plat represents by the blue shade, certain land to be withdrawn with a view to a reservation, under Chippewa Treaty of 30 Sept 1854, and as more particularly described in Commissioner of the General Land Office in letter of 6th Sept 1855. The subject was referred to the President for his sanction of the recommendation made in Secretary’s letter of 8th Sept 1855 and the original papers cannot now be found. This is a duplicate of the original, received in letter of Comm’r of the General Land Office of this date and is recommended to the President for his sanction of the withdrawal desired.

R. McClelland

Secretary

1856 Reservation in red and modern Red Cliff in brown. Although different in shape, both are roughly twenty-two square miles in size.

February 21st 1856

Let the withdrawal be made as recommended.

Franklin Pierce

Audit of the 1854 Treaty Claims

January 18, 2018

By Amorin Mello

This is one of many posts on Chequamegon History that feature the $90,000 of Indian trader debts that were debated during the 1854 Treaty and the 1855 Annuity Payments at La Pointe.

In summary, the Chiefs of the Chippewas made it a condition of the treaty that they would be granted $90,000 to settle outstanding debts with Indian traders, under the condition that a Council of Chiefs would determine which debts claimed by the traders were fair and accurate. The following quote is the fourth article of the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe, with the sentence about the $90,000 underlined for emphasis:

ARTICLE 4. In consideration of and payment for the country hereby ceded, the United States agree to pay to the Chippewas of Lake Superior, annually, for the term of twenty years, the following sums, to wit: five thousand dollars in coin; eight thousand dollars in goods, household furniture and cooking utensils; three thousand dollars in agricultural implements and cattle, carpenter’s and other tools and building materials, and three thousand dollars for moral and educational purposes, of which last sum, three hundred dollars per annum shall be paid to the Grand Portage band, to enable them to maintain a school at their village. The United States will also pay the further sum of ninety thousand dollars, as the chiefs in open council may direct, to enable them to meet their present just engagements. Also the further sum of six thousand dollars, in agricultural implements, household furniture, and cooking utensils, to be distributed at the next annuity payment, among the mixed bloods of said nation. The United States will also furnish two hundred guns, one hundred rifles, five hundred beaver traps, three hundred dollars’ worth of ammunition, and one thousand dollars’ worth of ready made clothing, to be distributed among the young men of the nation, at the next annuity payment.

~ 1854 Treaty with the Chippewa at La Pointe

Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties; Volume II by Charles Kappler, 1904

This $90,000 appear to have been an unexpected expense that the United States government incurred in order to successfully negotiate this Treaty. Indian Agent Henry Clark Gilbert was a commissioner of the Treaty, and was obliged to explain this $90,000 to his superiors at the Office of Indian Affairs in Washington D.C. The following is his explanation written a few weeks after the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe was concluded:

The Chiefs who were notified to attend brought with them in every instance their entire bands. We made a careful estimate of the number present and found there were about 4,000. They all had to be fed and taken care of, thus adding greatly to the expenses attending the negotiations.

A great number of traders and claim agents were also present as well as some of the persons from St. Paul’s who I had reason to believe attended for the purpose of preventing if possible the consummation of the treaty. The utmost precautions were taken by me to prevent a knowledge of the fact that negotiations were to take place from being public. The Messenger sent by me to Mr Herriman was not only trust worthy but was himself totally ignorant of the purport of the dispatches to Major Herriman. Information however of the fact was communicated from some source and the persons present in consequence greatly embarrassed our proceedings.

~ Treaty Commissioner Henry C. Gilbert’s explanation of the treaty concluded in 1854 with the assistance of David B. Herriman

Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters: Volume 79, No. 1, Appendix 5

Indian Agent Gilbert’s explanation suggests that there was some effort on his behalf to preemptively avoid the subject of outstanding debts from occuring during the Treaty negotiations. In January of 1855, a few months after the Treaty was negotiated, President Franklin Pierce budgeted for this $90,000 in the fund appropriated for fulfilling the terms of the Treaty:

For the payment of such debts as may be directed by the chiefs in open council, and found to be just and correct by the Secretary of the Interior, per 4th article of the treaty of September 30, 1854…….. 90,000

~ United States House of Representatives Documents, Volume 11, 33d Congress, 2nd Session, Ex. Doc. No. 61.

1854 Treaty of La Pointe Appropriations

As quoted above, the $90,000 negotiated during the treaty were to be distributed by a Council of the Chiefs following the treaty. How the $90,000 were actually distributed did not honor the intent or terms of the treaty. The following is a public notice from Indian Agent Gilbert that invited Indian traders with claims against Tribe to come forth with their claims before or during the 1855 Annuity, and makes no mention of any distribution to be determined by a Council of Chiefs:

PUBLIC NOTICE.

OFFICE MICHIGAN INDIAN AGENT,

DETROIT, June 12, 1855.ALL PERSONS having just and legal claims against the Chippewa Indians of Lake Superior are hereby notified that all such claims must be presented without delay to the undersigned, for investigation. Each claim must be accompanied by such evidence of its justice and legality as the claimant may be able to furnish; and in all cases where the idebtedness claimed is on book account, or is composed of aggregated items, transcripts of such accounts specifying the items in detail, with the charge for each item, and the name of the person to whom, and time when, the same was furnished, must accompany the claims submitted. The original books of entry must also in all cases be prepared for examination.

Claims may be presented at any time prior to the close of the next annuity payment at La Pointe, which will take place in the month of August next; but after that time they will not be received or acted upon.

This notice is given in accordance with instructions received from the United States Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

HENRY C. GILBERT.

Indian Agent.

jy 10 4t~ Superior Chronicle newspaper, July 10th, 1855

Library of Congress

The distribution of this $90,000 was hotly debated by Blackbird and other members of the Council of Chiefs during the 1855 Annuity Payments. It is clear from the speeches transcribed from this important event that the Council was not being allowed to determine the distribution of this $90,000. The following is one of many speeches that touched upon this subject:

In what Blackbird said he expressed the mind of a majority of the chiefs now present. We wish the stipulations of the treaty to be carried out to the very letter.

I wish to say our word about our reserves. Will these reserves made for each of our bands, be our homes forever?

When we took credits of our trader last winter, and took no furs to pay him, and wish to get hold of this 90,000 dollars, that we may pay him off of that. This is all we came here for. We want the money in our own hands & we will pay our own traders. We do not think it is right to pay what we do not owe. I always know how I stand my acct. and we can pay our own debts. From what I have now said I do not want you to think that we want the money to cheat our creditors, but to do justice to them I owe. I have my trader & know how much I owe him, & if the money is paid into the hands of the Indians we can pay our own debts.

~ Adikoons, Chief of Grand Portage Band

(Wheeler to Smith, 18 Jan. 1856)

Blackbird’s Speech at the 1855 Payment

With the above quotes as an introduction to this subject, we will now investigate what exactly happened to the $90,000 to be disbursed as “directed by the chiefs in open council”. What we have found so far appears to suggest that the federal government did not honor their Trust responsibility to the Tribe:

Senate Documents, Volume 112

[Page 295 of audit]

Indian Disbursements

Statement containing a list of the names of all persons to whom goods, money, or effects have been delivered, from July 1, 1856, to June 30, 1857, specifying the amounts and objects for which they were intended, the amount accounted for, and the balances under each specified head still remaining in their hands; prepared in obedience to an act of Congress of June 30, 1834, entitled “An act to provide for the organization of the department of Indian affairs.”

[Pages 303-305 of audit]

Fulfilling treaties with Chippewas of Lake Superior, September 30, 1854

| When issued | To whom issued. | For what purpose. | Amount of requisition. | Am’t accounted for. |

Amount unaccounted for.

|

| 1856 | |||||

| July 3 | John B. Jacobs | Fulfilling Treaties, (due) | $1,718.73 | $1,718.73 | |

| 22 | Henry C. Gilbert | …do… | $7,000.00 | $7,000.00 | |

| Do | …do… | $5,000.00 | $5,000.00 | ||

| Aug. 14 | Henry E. Leman | …do…(due)… | $1,412.50 | $1,412.50 | |

| 18 | Ramsey Crooks | …do…do… | $6,617.64 | $6,617.64 | |

| Adam Noongoo | …do…do… | $66.00 | $66.00 | ||

| Wm. Parsons | …do…do… | $28.50 | $28.50 | ||

| Erwin Leiky | …do…do… | $119.75 | $119.75 | ||

| Robert Morrin | …do…do… | $163.56 | $163.56 | ||

| Charles Bellisle | …do…do… | $191.00 | $191.00 | ||

| Posh-qway-gin | …do…do… | $47.88 | $47.88 | ||

| 22 | W. A. Pratt | …do…do… | $50.00 | $50.00 | |

| John G. Kittson | …do…do… | $1,280.93 | $1,280.93 | ||

| Asaph Whittlesey | …do…do… | $25.00 | $25.00 | ||

| Louis Bosquet | …do…do… | $72.00 | $72.00 | ||

| David King | …do…do… | $100.00 | $100.00 | ||

| P. O. Johnson | …do…do… | $10.12 | $10.12 | ||

| Henry Elliott | …do…do… | $399.02 | $399.02 | ||

| McCullough & Elliott | …do…do… | $475.78 | $475.78 | ||

| Edward Assinsece | …do…do… | $50.00 | $50.00 | ||

| John Southwind | …do…do… | $21.00 | $21.00 | ||

| Kay-kake | …do…do… | $35.00 | $35.00 | ||

| Goff & Co. | …do…do… | $556.21 | $556.21 | ||

| Jame Halliday | …do…do… | $67.88 | $67.88 | ||

| Peter Crebassa | …do…do… | $1,013.99 | $1,013.99 | ||

| S. L. Vaugh | …do…do… | $57.08 | $57.08 | ||

| David King | …do…do… | $191.72 | $191.72 | ||

| Peter B. Barbean | …do…do… | $1,200.00 | $1,200.00 | ||

| 23 | Antoine Gaudine | …do…do… | $3,250.94 | $3,250.94 | |

| Peter Markman | …do…do… | $300.00 | $300.00 | ||

| Pat L. Philan | …do…do… | $90.08 | $90.08 | ||

| Treasurer of township of Lapointe | …do…do… | $224.77 | $224.77 | ||

| Michael Bosquet | …do…do… | $219.63 | $219.63 | ||

| James Ermatinger | …do…do… | $2,000.00 | $2,000.00 | ||

| Louison Demaris | …do…do… | $2,000.00 | $2,000.00 | ||

| Joseph Morrison | …do…do… | $250.00 | $250.00 | ||

| John W. Bell | …do…do… | $253.11 | $253.11 | ||

| 27 | Paul H. Beaubien | …do…do… | $600.00 | $600.00 | |

| R. Sheldon & Co. | …do…do… | $1,124.71 | $1,124.71 | ||

| Abraham Place | …do…do… | $450.00 | $450.00 | ||

| Michael James | …do…do… | $195.00 | $195.00 | ||

| R. J. Graveract | …do…do… | $269.19 | $269.19 | ||

| Reuben Chapman | …do…do… | $71.11 | $71.11 | ||

| Miller Wood | …do…do… | $38.50 | $38.50 | ||

| Robert Reed | …do…do… | $21.60 | $21.60 | ||

| Louis Gurno | …do…do… | $179.00 | $179.00 | ||

| Gregory S. Bedel | …do…do… | $142.63 | $142.63 | ||

| Geo. R. Stuntz | …do…do… | $537.41 | $537.41 | ||

| Usop & Hoops | …do…do… | $49.43 | $49.43 | ||

| May-yan-wash | …do…do… | $45.50 | $45.50 | ||

| John Hartley | …do…do… | $41.01 | $41.01 | ||

| B. F. Rathbun | …do…do… | $8.07 | $8.07 | ||

| W. W. Spaulding | …do…do… | $258.92 | $258.92 | ||

| Stephen Bonge | …do…do… | $40.00 | $40.00 | ||

| Abel Hall | …do…do… | $160.00 | $160.00 | ||

| Louis Cadotte | …do…do… | $200.00 | $200.00 | ||

| John Senter & Co. | …do…do… | $17.00 | $17.00 | ||

| John B. Roy | …do…do… | $150.00 | $150.00 | ||

| L. Y. B. Birchard | …do…do… | $26.00 | $26.00 | ||

| Peter Roy | …do…do… | $250.00 | $250.00 | ||

| Jacob F. Shaffer | …do…do… | $150.00 | $150.00 | ||

| Peter Vandeventer | …do…do… | $216.31 | $216.31 | ||

| Sept. 4 | John Hotley, jr. | …do…do… | $538.48 | $538.48 | |

| G. B. Armstrong | …do…do… | $950.00 | $950.00 | ||

| Lathrop Johnson | …do…do… | $376.00 | $376.00 | ||

| 6 | Wm. Mathews | …do…do… | $1,741.50 | $1,741.50 | |

| Cronin, Hurxthal & Sears | …do…do… | $4,583.77 | $4,583.77 | ||

| 13 | Henry C. Gilbert | …do… | $12,500.00 | ||

| 24 | B. W. Brisbois | …do…(due)… | $4,000.00 | $4,000.00 | |

| 27 | John Brunet | …do…do… | $2,000.00 | $2,000.00 | |

| John B. Roy | …do…do… | $80.00 | $80.00 | ||

| Edward Connor | …do…do… | $600.00 | $600.00 | ||

| Alexis Corbin | …do…do… | $1,000.00 | $1,000.00 | ||

| Louis Corbin | …do…do… | $1,108.47 | $1,108.47 | ||

| Vincent Roy | …do…do… | $645.36 | $645.36 | ||

| Abner Sherman | …do…do… | $568.00 | $568.00 | ||

| John B. Landry | …do…do… | $502.64 | $502.64 | ||

| Thomas Conner | …do…do… | $1,050.00 | $1,050.00 | ||

| Augustus Corbin | …do…do… | $238.50 | $238.50 | ||

| Julius Austrain | …do…do… | $6,000.00 | $6,000.00 | ||

| Do… | …do…do… | $1,876.86 | $1,876.86 | ||

| John B. Corbin | …do…do… | $750.00 | $750.00 | ||

| Cruttenden & Lynde | …do…do… | $1,300.00 | $1,300.00 | ||

| Orrin W. Rice | …do…do… | $358.09 | $358.09 | ||

| Francis Ronissaie | …do…do… | $817.74 | $817.74 | ||

| Dec. 6 | W. G. and G. W. Ewing | …do…do… | $787.02 | $787.02 | |

| 1857 | |||||

| Jan. 2 | Henry C. Gilbert | …do… | $674.73 | $674.73 | |

| Feb 21 | Do | …do… | $8,133.33 | $8,133.33 | |

| 24 | John B. Cadotte | …do…(due)… | $1,265.00 | $1,265.00 | |

| Cruttenden & Lynde | …do…do… | $1,615.00 | $1,615.00 | ||

| J. B. Landry | …do…do… | $560.00 | $560.00 | ||

| P. Chouteau, jr., & Co. | …do…do… | $935.00 | $935.00 | ||

| Vincent Roy | …do…do… | $5,000.00 | $5,000.00 | ||

| Northern Fur Company | …do…do… | $625.00 | $625.00 | ||

| J. B. Landry | …do…do… | $90.00 | $90.00 | ||

| $105,071.70 | $84,363.64 | $20,708.06 |

Many of the Indian traders listed above make regular appearances in other primary documents of Chequamegon History. Some of the names are misspelled but still recognizable to regular readers. In summary let’s take a closer look at the top ten Indian traders that received the most disbursements related to the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe:

9½.) James Ermatinger

$2,000.00

James Ermatinger was involved with the American Fur Company in earlier years. He seems to have become an independent Indian trader in later years leading up to the 1854 Treaty:

James founded Jim Falls, Wis., arriving by canoe from La Pointe, Wis. where he was involved in fur trading. He settled in Jim Falls, initially managing a trading post there for the American Fur Company. Others in the Ermatinger family were prominent fur traders in Canada, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and Wisconsin.

9½.) Louison Demaris

$2,000.00

According to Theresa Schenck’s research in her book All Our Relations, Louison Demarais may have been a son of Jean Baptiste Demarais who was an interpreter for Alexander Henry the Younger’s North West Company on the Red River:

Louison Desmarais residing at Chippewa River a ½ breed Chippewa 50 yrs of age born at Pembina and remained in the North until 9 years back when he came to Chippewa river where he has resided since claims for himself and wfie Angelique a ½ breed, 35 yrs of age born at Fond du Lac where she remained until she was married 23 years since when she went to the North with her husband and has since lived with him.

~ 1839 Mixed Blood Census

All Our Relations by Theresa M. Schenck, 2010, page 60

8.) Cruttenden & Lynde

$1,615.00 + $1,300.00 = $2,915.00

“Here lie the remains of Hon. J. W. Lynde Killed by Sioux Indians Aug. 18.1862″

~ Findagrave.com

James William Lynde was an Indian Agent, Senator, and first casualty of 1862 Sioux Uprising. Mr. Lynde was also a signatory of the 1854 Treaty, which may be a conflict of interest:

Hon. James W. Lynd was a native of Baltimore, born in 1830, but was reared and educated at Cincinnati. He had received a college education at Woodward College, having attended from 1842 – 1844. He was a man of accomplishments and ability. He thoroughly mastered the Indian language, married successively two Indian wives, and spent years in the study of the history and general character of the Sioux or Dakota tribe. For some time prior to his death he had been engaged in revising for publication the manuscript of an elaborate work containing the results of his studies and researches. Under the circumstances the greater part of this manuscript was lost. He was a young man, of versatile talents had been an editor, lecturer, public speaker, and was a member of the Minnesota State Senate in 1861.

~ Sketches: Historical and Descriptive of the Monuments and Tablets Erected by the Minnesota Valley Historical Society in Renville and Redwood Counties, Minnesota by the Minnesota Valley Historical Society, 1902, page 6

Joel D. Cruttenden was Mr. Lynch’s business partner:

Col. Cruttenden, of whom I have spoken briefly in another place, left St. Louis in 1846 and removed to Prairie du Chien, where he was employed by Brisbois & Rice. In 1848 he came to ST. PAUL and remained up to 1850, when he took up his residence in St. Anthony and engaged in business with R. P. Russel. He then went to Crow Wing and was connected with Maj. J. W. Lynde. In 1857 he was elected to the House of Representatives, and on the breaking out of the war was commissioned Captain Assistant Quartermaster; was taken prisoner, and on being exchanged rose to the rank of Colonel. At the close of the war he was honorably discharged, and soon after removed to Bayfield, Wisconsin, where he has held many offices and is greatly esteemed. He is a pleasant, genial gentleman, well known and well liked.

~ Pen Pictures of St. Paul, Minnesota, and Biographical Sketches of Old Settlers: Volume 1, by Thomas McLean Newson, 1886, page 95

7.) Antoine Gaudine

$3,250.94

~ Antoine Gordon

~ Noble Lives of a Noble Race by the St. Mary’s Industrial School (Odanah), page 207

Antoine Gaudine (a.k.a. Gordon) as one of those larger-than-life mixed-blood members of the La Pointe Band leading up to the 1854 Treaty and beyond:

Mr Gordon was the founder of the village of Gordon and for years had a trading post there which was the only store there. It is but a few years since he discontinued this store. He was a full-blooded Chippewa Indian, and came here from Madelaine Island, where he ran a post years ago. He was formerly the owner of the famous Algonquin, the first ship to come through the Soo locks, and used her in the lumber trade.

~ Eau Claire Leader newspaper, May 8, 1907

6.) B. W. Brisbois

$4,000.00

Bernard Walter Brisbois was a son of Michael Brisbois, Sr.:

Bernard Brisbois was born in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, in 1808, to Michel Brisbois, a French-Canadian voyageur, and his second wife Domitelle (Madelaine) Gautier de Verville.

Like his father, Brisbois also began his career in the fur trade, working as agent for the American Fur Company. Bernard married Therese LaChappelle [daughter of metis Pélagie LaPointe (herself the daughter of Pierre LaPointe and Etoukasahwee) and Antoine LaChapelle]. Later he engaged in the mercantile business in Prairie du Chien until 1873 when he was appointed consul at Verviers, Belgium. He returned to Prairie du Chien in 1874 and lived there until his death in 1885.

5.) Cronin, Hurxthal & Sears

$4,583.77

Advertisement of Cronin, Hurxthal & Sears

~ The Prairie News (Okolona, Miss.), April 15, 1858, page 4

According to a receipt from this company, the partners behind this firm were John B. Cronin, Ben. Hurxthal and J. Newton Sears. No further biographical information could be found about these individuals, who are presumed to have been New York City businessmen. In general they appear to have been involved with trades associated with slavery and Indians. Per their advertisement, they were the successors to the firm of Grant and Barton:

Grant and Barton nevertheless remained active in the [Texas] region, winning government contracts to supply the Bureau of Indian affairs with “blankets and dry goods” in the late 1840s and early 1850s…

~ The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism, 1815-1860, by Calvin Schermerhorn, 2015, page 225

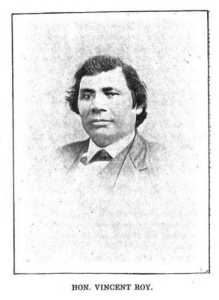

4.) Vincent Roy

$5,000.00 + $645.36 = $5,645.36

Vincent Roy, Jr. (III)

~ Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, by Chrysostom Verwyst, 1900, pages 472-476

Vincent Roy, Sr. (II) and his son Vincent Roy, Jr. (III) were prominent members of the La Pointe Band mixed-bloods. Sr. was recognized by Gilbert as the Head of the Mixed Bloods of the La Pointe Band of Lake Superior Chippewas. Jr. was allegedly an interpreter at the 1854 Treaty, but is not identified in the Treaty itself and cannot find primary source. Jr. is described as a skilled trader in many sources, including this one:

“Leopold and Austrian (Jews) doing a general merchandize and fur-trading business at LaPointe were not slow in recognizing ‘their man.’ Having given employment to Peter Roy, who by this time quit going to school, they also, within the first year of his arrival at this place, employed Vincent to serve as handy-man for all kind of things, but especially, to be near when indians from the woods were coming to trade, which was no infrequent occurrence. After serving in that capacity about two years, and having married, he managed (from 1848 to 1852) a trading post for the same Leopold and Austrian; at first a season at Fond du Lac, Minn., then at Vermillion Lake, and finally again at Fond du Lac.”

~ Miscellaneous materials related to Vincent Roy, 1861-1862, 1892, 1921

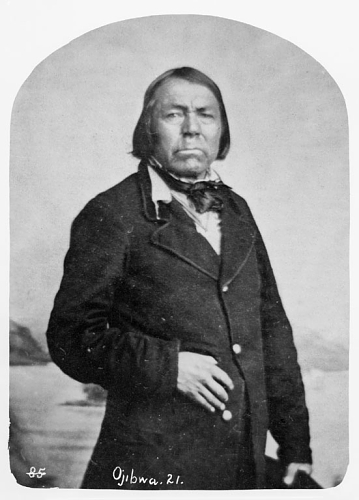

3.) R. Crooks

$6,617.64

Ramsay Crooks

~ Madeline Island Museum

Ramsey Crooks enjoyed a long history with the American Fur Company outfit at La Pointe in the decades leading up to the 1854 Treaty:

“Ramsey Crooks (also spelled Ramsay) was born in Scotland in 1787. He immigrated to Canada in 1803 where he worked as a fur trader and explorer around the Great Lakes. He began working for the American Fur Company, which was started by John Jacob Astor, America’s first multi-millionaire, and made an expedition to the Oregon coast from 1809-1813 for the company. By doing so he also became a partner in the Pacific Fur Company. In 1834 he became acting president of the American Fur Company following Astor’s retirement to New York. A great lakes sailing vessel the Ramsey Crooks was constructed in 1836 by the American Fur Co. A nearly identical sister ship was built in the same year and was called the Astor. Both ships were sold by the dissolving fur company in 1850. Ramsay Crooks passed away in 1859, but had made a name for himself in the fur trade not only in Milwaukee and the Great Lakes, but all the way to the Pacific Ocean.”

2.) J. Austrian

$ 6,000.00 + $1,876.86 = $7,876.86

Julius Austrian

~ Madeline Island Museum

Julius Austrian was competitor and successor of the American Fur Company during the decade immediately leading up to the 1854 Treaty. Chequamegon History’s research has explored the previously uncovered circumstances of Austrian’s purchase of the Village of La Pointe from American Fur Company in 1853, being the unnamed and de facto host of the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe, being the host of the 1855 Annuities at La Pointe, and the host of the 1855 High Holy Days at La Pointe:

“In 1855 a number of Jewish Indian traders met on an island in Lake Superior in the frontier village of La Pointe, Wisconsin. The Indians were assembled there to collect their annuities and the Jews were present to dun their debtors before they dispersed. There were enough Jews for a minyan and a service was held. That was the beginning and the end of La Pointe Jewry.”

~ United States Jewry 1776-1985: Vol. 2; the Germanic Period, Part 1 by Jacob Rader Marcus Wayne State University Press , 1991, page 196

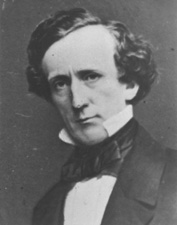

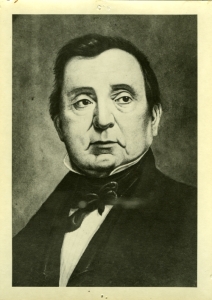

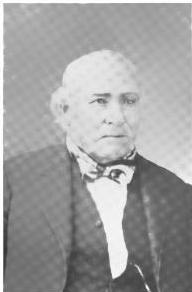

1.) Henry C. Gilbert

$0.00 ?

Henry Clark Gilbert

~ Branch County Photographs

Mackinac Indian Agent Henry Clark Gilbert was the Commissioner of the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe along with David B. Herriman.

Gilbert submitted requisitions for $5,000.00, $7,000.00, $12,500.00, $674.73, and $8,133.33; which is a total amount of $33,308.06. The amount accounted for in his name is $0.00, but his total amount unaccounted for is $20,808.06. The difference between the total amount Gilbert requisitioned and his total amount unaccounted for is $12,500, which is the same amount that Gilbert requisitioned for on September 4th, 1856.

A closer look at all of the 1854 Treaty accounts as a whole suggests that Gilbert was paid his $12,500.00 despite what is shown on paper. The total amount accounted for is actually $71,763.64; which is $12,600.00 less than the total amount on paper. The total amount unaccounted for is $20,808.06; which is $100 greater than the total amount on paper (all of which was in Gilbert’s name). We are left with a puzzle missing some pieces. Did Gilbert obtain his $12,500.00 fraudulently? Was the extra $100 accounted for taken from the unaccounted amounts by someone else as a bribe?

Did Gilbert abuse his Trust responsibility to the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe? Or was this simply a case of sloppy reporting by a federal clerk?

1854 Treaty of La Pointe Appropriations

November 29, 2017

By Amorin Mello

House Documents, Volume 112

By United States House of Representatives

33d Congress,

2nd Session.

Ex. Doc. No. 61.

TREATY WITH CHIPPEWA INDIANS.

————————

MESSAGE

FROM

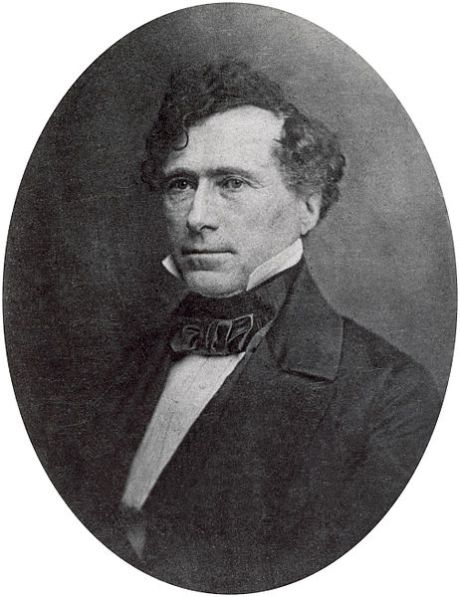

THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES,

United States President

Franklin Pierce

circa 1855

~ Commons.Wikimedia.com

TRANSMITTING

Estimates of appropriations for carrying into effect the treaty with the Chippewa Indians &c.

————————

February 8, 1855.—Laid upon the table and ordered to be printed.

————————

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:

I communicate to Congress the following letter from the Secretary of the Interior, with its enclosure, on the subject of a treaty between the United States and the Chippewa Indians of Lake Superior, and recommend that the appropriations therein asked for may be made.

FRANLIN PEIRCE.

Washington, February 7, 1855.

Department Of The Interior,

Washington, February 6,1855.

Secretary of the Interior

Robert McClelland

circa 1916

~ Commons.Wikipedia.com

SIR: I have the honor to transmit to you, herewith, a copy of a communication from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, dated the 5th instant, calling my attention to the subject of a treaty made at La Pointe, Wisconsin, by Henry C. Gilbert and Daniel B. Herriman, commissioners on the part of the United States, and the Chippewa Indians of Lake Superior; and, to enable this department to carry the treaty into effect, recommend that Congress be requested to make the appropriations specified in the letter of the Commissioner, and which will be immediately required for that purpose.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

R. McCLELLAND,

Secretary.

To the President.

Department Of The Interior,

Office Indian Affairs, February 5, 1855.

Mackinac Indian Agent

Henry Clark Gilbert

~ Branch County Photographs

Sir: Having received the official information on the 24th ultimo of the approval and ratification, by the President and Senate, of the articles of agreement and convention made and entered into at La Pointe, in the State of Wisconsin, by Henry C. Gilbert and Daniel B. Herriman, commissioners on the part of the United States, and the Chippewa Indians of Lake Superior and Mississippi, I have the honor now to call your attention to the appropriations that will be required immediately to enable the department to carry the treaty into effect, viz:

For fulfilling treaties with the Chippewas of Lake Superior.

- For expenses (in part) of selecting reservations, and surveying and marking the boundaries thereof, per 2d, 3d, and 12th articles of the treaty of September 30, 1854 …….. $3,000

- For the payment of the first of twenty instalments in coin, goods, &c, agricultural implements, &c, and education, &c, per 4th article of the treaty of September 30, 1854 …….. 19,000

- For the purchase of clothing and other articles to be given to the young men at the next annuity payment, as per 4th article of the treaty of September 30, 1854 …….. 4,800

- For the purchase of agricultural implements and other articles, as presents for the mixed bloods, per 4th article of the treaty of September 30, 1854 …….. 6,000

- For the payment of such debts as may be directed by the chiefs in open council, and found to be just and correct by the Secretary of the Interior, per 4th article of the treaty of September 30, 1854 …….. 90,000

- For the payment of such debts of the Bois Forte bands as may be directed by their chiefs, and found lo be just and correct by the Secretary of the Interior, per 12th article of the treaty of September 30, 1844 …….. 10,000

- For the payment of the first of five instalments in blankets, cloth, &c, to the Bois Forte band, per 12th article of the treaty of September 30, 1854 …….. 2,000

- For the first of twenty instalments for the pay of six smiths and assistants, per 5th and 2d articles of the treaty of September 30, 1854 …….. 5,040

- For the first of twenty instalments for the support of six smith shops, per 5th and 2d articles of the treaty of September 30, 1854 …….. 1,320

It will be observed that the treaty of September 30, 1854, recognized the Chippewas of Lake Superior as a branch of the nation, and that the pecuniary and beneficiary stipulations therein are for their exclusive use.

By the fifth article of the treaty the Lake Superior Chippewas are to have six blacksmiths and assistants, and they relinquish, by the same article, all other employés to which they might otherwise have been entitled under former treaties.

The Chippewas of the Mississippi are, by the eighth article of the treaty, entitled to one-third of the benefits of treaties prior to 1847; and, by consequence, retain an interest of one-third in the stipulations for smith shops, &c., and farmers, &c, per second article of the treaty of July 29, 1837; and in the farmers, and carpenters, and smiths, &c., mentioned in the fourth article of the treaty of October 4, 1842.

On an examination of the condition of existing appropriations to fulfil the stipulations just mentioned, it is found that the balances in the treasury are sufficient to sustain these employés and otherwise meet the requirements of the stipulations referred to, so far as the Chippewas of the Mississippi are interested, during the next fiscal year.

In case appropriations are made by Congress, in pursuance of the foregoing estimates, it will be perceived that the following items of the Indian appropriation bill now before Congress might, with propriety, be stricken out, viz:

House bill 555, reported, with amendments, January 16, 1855:

- Page 4, lines 68, 69, 70, and 71, “three thousand dollars,” ($3,000.)

- Page 4, lines 72, 73, 74, 75, and 76, “one thousand dollars,” ($1,000.)

- Page 5, lines 89, 90, 91, 92, and 93, “two thousand dollars,” ($2,000.)

- Page 5, lines 94, 95, and 96, “one thousand dollars,” ($1,000.) Page 5, lines 97, 98, and 99, “one thousand two hundred dollars,” ($1,200.)

Director of of the Bureau of Indian Affairs

George Washington Manypenny

circa 1886

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

As it is not deemed necessary, I do not therefore submit, at present an estimate for appropriations to pay employés for the Bois Forte band, as per twelfth article of the treaty of September 30, 1854, or to liquidate a balance, should any be found due to these Indians by the investigation, which it is provided by the ninth article of the same treaty shall be made.

Should the foregoing estimates and suggestions be approved by you, I respectfully recommend that they be laid before Congress as early as practicable.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

GEO. W. MANYPENNY,

Commissioner.

Hon. R. McCLELLAND,

Secretary of the Interior.

The Enemy of my Enemy: The 1855 Blackbird-Wheeler Alliance

November 29, 2013

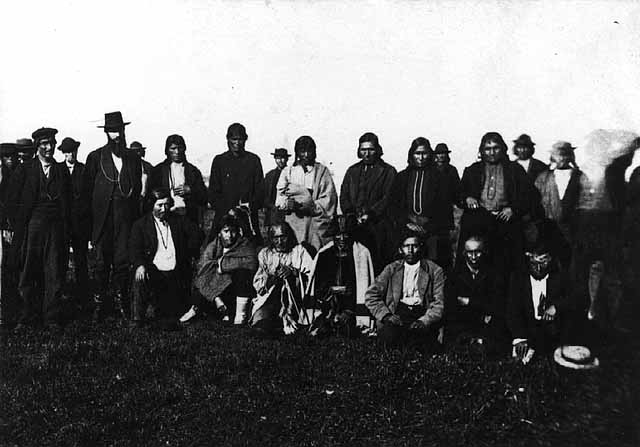

Identified by the Minnesota Historical Society as “Scene at Indian payment, probably at Odanah, Wisconsin. c. 1865.” by Charles Zimmerman. Judging by the faces in the crowd, this is almost certainly the same payment as the more-famous image that decorates the margins of the Chequamegon History site (Zimmerman MNHS Collections)

A staunch defender of Ojibwe sovereignty, and a zealous missionary dedicating his life’s work to the absolute destruction of the traditional Ojibwe way of life, may not seem like natural political allies, but as Shakespeare once wrote, “Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows.”

In October of 1855, two men who lived near Odanah, were miserable and looking for help. One was Rev. Leonard Wheeler who had founded the Protestant mission at Bad River ten years earlier. The other was Blackbird, chief of the “Bad River” faction of the La Pointe Ojibwe, that had largely deserted La Pointe in the 1830s and ’40s to get away from the men like Wheeler who pestered them relentlessly to abandon both their religion and their culture.

Their troubles came in the aftermath of the visit to La Pointe by George Manypenny, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to oversee the 1855 annuity payments. Many readers may be familiar with these events, if they’ve read Richard Morse’s account, Chief Buffalo’s obituary (Buffalo died that September while Manypenny was still on the island), or the eyewitness account by Crockett McElroy that I posted last month. Taking these sources together, some common themes emerge about the state of this area in 1855:

- After 200 years, the Ojibwe-European relationship based on give and take, where the Ojibwe negotiated from a position of power and sovereignty, was gone. American government and society had reached the point where it could by impose its will on the native peoples of Lake Superior. Most of the land was gone and with it the resource base that maintained the traditional lifestyle, Chief Buffalo was dead, and future chiefs would struggle to lead under the paternalistic thumb of the Indian Department.

- With the creation of the reservations, the Catholic and Protestant missionaries saw an opportunity, after decades of failures, to make Ojibwe hunters into Christian farmers.

- The Ojibwe leadership was divided on the question of how to best survive as a people and keep their remaining lands. Some chiefs favored rapid assimilation into American culture while a larger number sought to maintain traditional ways as best as possible.

- The mix-blooded Ojibwe, who for centuries had maintained a unique identity that was neither Native nor European, were now being classified as Indians and losing status in the white-supremacist American culture of the times. And while the mix-bloods maintained certain privileges denied to their full-blooded relatives, their traditional voyageur economy was gone and they saw treaty payments as one of their only opportunities to make money.

- As with the Treaties of 1837 and 1842, and the tragic events surrounding the attempted removals of 1850 and 1851, there was a great deal of corruption and fraud associated with the 1855 payments.

This created a volatile situation with Blackbird and Wheeler in the middle. Before, we go further, though, let’s review a little background on these men.

This 1851 reprint from Lake Superior Journal of Sault Ste. Marie shows how strongly Blackbird resisted the Sandy Lake removal efforts and how he was a cultural leader as well as a political leader. (New Albany Daily Ledger, October 9, 1851. Pg. 2).

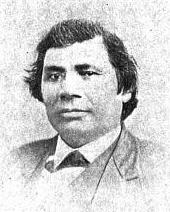

Who was Blackbird?

Makadebineshii, Chief Blackbird, is an elusive presence in both the primary and secondary historical record. In the 1840s, he emerges as the practical leader of the largest faction of the La Pointe Band, but outside of Bad River, where the main tribal offices bear his name, he is not a well-known figure in the history of the Chequamegon area at all.

Unlike, Chief Buffalo, Blackbird did not sign many treaties, did not frequently correspond with government officials, and is not remembered favorably by whites. In fact, his portrayal in the primary sources is often negative. So then, why did the majority of the Ojibwe back Blackbird at the 1855 payment? The answer is probably the same reason why many whites disliked him. He was an unwavering defender of Ojibwe sovereignty, he adhered to his traditional culture, and he refused to cooperate with the United States Government when he felt the land and treaty rights of his people were being violated.

One needs to be careful drawing too sharp a contrast between Blackbird and Buffalo, however. The two men worked together at times, and Blackbird’s son James, later identified his father as Buffalo’s pipe carrier. Their central goals were the same, and both labored hard on behalf of their people, but Buffalo was much more willing to work with the Government. For instance, Buffalo’s response in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, when the fate of Ojibwe removal was undecided, was to go to the president for help. Blackbird, meanwhile, was part of the group of Ojibwe chiefs who hoped to escape the Americans by joining Chief Zhingwaakoons at Garden River on the Canadian side of Sault Ste. Marie.

Still, I hesitate to simply portray Blackbird and Buffalo as rivals. If for no other reason, I still haven’t figured out what their exact relationship was. I have not been able to find any reference to Blackbird’s father, his clan, or really anything about him prior to the 1840s. For a while, I was working under the hypothesis that he was the son of Dagwagaane (Tugwaganay/Goguagani), the old Crane Clan chief (brother of Madeline Cadotte), who usually camped by Bad River, and was often identified as Buffalo’s second chief.

However, that seems unlikely given this testimony from James Blackbird that identifies Oshkinawe, a contemporary of the elder Blackbird, as the heir of Guagain (Dagwagaane):

Statement of James Blackbird: Condition of Indian affairs in Wisconsin: hearings before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, [61st congress, 2d session], on Senate resolution, Issue 263. pg 203. (Digitized by Google Books).

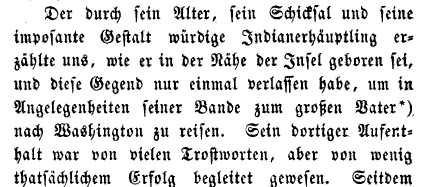

It seems Commissioner Manypenny left La Pointe before the issue was entirely settled, because a month later, we find a draft letter from Blackbird to the Commissioner transcribed in Wheeler’s hand:

Mushkesebe River Oct. 1855

Blackbird. Principal chief of the Mushkisibi-river Indians to Hon. G. Manepenny Com. of Indian Affairs Washington City.

Father; Although I have seen you face to face, & had the privilege to talking freely with you, we did not do all that is to be attended to about our affairs. We have not forgotten the words you spoke to us, we still keep them in our minds. We remember you told us not to listen to all the foolish stories that was flying about–that we should listen to what was good, and mind nothing about anything else. While we listened to your advice we kept one ear open and the other shut, & [We?] kept retained all you spoke said in our ears, and. Your words are still ringing in our ears. The night that you left the sound of the paddles in boat that carried you away from us was had hardly gone ceased before the minds of some of the chiefs was were tuned by the traders from the advice you gave, but we did not listen to them. Ja-jig-wy-ong, (Buffalo’s son) son says that he & Naganub asked Mr. Gilbert if they could go to Washington to see about the affairs of the Indians. Now father, we are sure you opened your heart freely to us, and did not keep back anything from us that is for our good. We are sure you had a heart to feel for us & sympathise with us in our trials, and we think that if there is any important business to be attended to you would not have kept it secret & hid it from us, we should have knew it. If I am needed to go to Washington, to represent the interests of our people, I am ready to go. The ground that we took against about our old debts, I am ready to stand shall stand to the last. We are now in Mr. Wheelers house where you told us to go, if we had any thing to say, as Mr. W was our friend & would give us good advice. We have done so. All the chiefs & people for whom I spoke, when you were here, are of the same mind. They all requested before they left that I should go to Washington & be sure & hold on to Mr. Wheeler as one to go with me, because he has always been our steadfast friend and has al helped us in our troubles. There is another thing, my father, which makes us feel heavy hearted. This is about our reservation. Although you gave us definite instructions about it, there are some who are trying to shake our reserve all to pieces. A trader is already here against our will & without any authority from Govt, has put him up a store house & is trading with our people. In open council also at La Pointe when speaking for our people, I said we wanted Mr. W to be our teacher, but now another is come which whom we don’t want, and is putting up a house. We supposed when you spoke to us about a teacher being permitted to live among us, you had reference to the one we now have, one is enough, we do not wish to have any more, especially of the kind of him who has just come. We forbid him to build here & showed him the paper you gave us, but he said that paper permitted him rather than forbid him to come. If the chiefs & young men did not remember what you told them to keep quiet there would already be have been war here. There is always trouble when there two religions come together. Now we are weak and can do nothing and we want you to help us extend your arms to help us. Your arms can extend even to us. We want you to pity & help us in our trouble. Now we wish to know if we are wanted, or are permitted, three or four of us to come to which Washington & see to our interests, and whether our debts will be paid. We would like to have you write us immediately & let us know what your will is, when you will have us come, if at all. One thing further. We do not want any account to be allowed that was not presented to us for us to pass our opin us to pass judgement on, we hear that some such accounts have been smuggled in without our knowledge or consent.

The letter is unsigned, lacks a specific date, and has numerous corrections, which indicate it was a draft of the actual letter sent to Manypenny. This draft is found in the Wheeler Family Papers in the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center. As interesting as it is, Blackbird’s letter raises more questions than answers. Why is the chief so anxious to go to Washington? What are the other chiefs doing? What are these accounts being smuggled in? Who are the people trying to shake the reservation to pieces and what are they doing? Perhaps most interestingly, why does Blackbird, a practitioner of traditional religion, think he will get help from a missionary?

For the answer to that last question, let’s take a look at the situation of Leonard H. Wheeler. When Wheeler, and his wife, Harriet came here in 1841, the La Pointe mission of Sherman Hall was already a decade old. In a previous post, we looked at Hall’s attitudes toward the Ojibwe and how they didn’t earn him many converts. This may have been part of the reason why it was Wheeler, rather than Hall, who in 1845 spread the mission to Odanah where the majority of the La Pointe Band were staying by their gardens and rice beds and not returning to Madeline Island as often as in the past.

When compared with his fellow A.B.C.F.M. missionaries, Sherman Hall, Edmund Ely, and William T. Boutwell, Wheeler comes across as a much more sympathetic figure. He was as unbending in his religion as the other missionaries, and as committed to the destruction of Ojibwe culture, but in the sources, he seems much more willing than Hall, Ely, or Boutwell to relate to Ojibwe people as fellow human beings. He proved this when he stood up to the Government during the Sandy Lake Tragedy (while Hall was trying to avoid having to help feed starving people at La Pointe). This willingness to help the Ojibwe through political difficulties is mentioned in the 1895 book In Unnamed Wisconsin by John N. Davidson, based on the recollections of Harriet Wheeler:

From In Unnamed Wisconsin pg. 170 (Digitized by Google Books).

So, was Wheeler helping Blackbird simply because it was the right thing to do? We would have to conclude yes, if we ended it here. However, Blackbird’s letter to Manypenny was not alone. Wheeler also wrote his own to the Commissioner. Its draft is also in the Wheeler Family Papers, and it betrays some ulterior motives on the part of the Odanah-based missionary:

example not to meddle with other peoples business.

Mushkisibi River Oct. 1855

L.H. Wheeler to Hon. G.W. Manypenny

Dear Sir. In regard to what Blackbird says about going to Washington, his first plan was to borrow money here defray his expenses there, & have me start on. Several of the chiefs spoke to me before soon after you left. I told them about it if it was the general desire. In regard to Black birds Black Bird and several of the chiefs, soon after you left, spoke to me about going to Washington. I told them to let me know what important ends were to be affected by going, & how general was the desire was that I should accompany such a delegation of chiefs. The Indians say it is the wish of the Grand Portage, La Pointe, Ontonagun, L’anse, & Lake du Flambeaux Bands that wish me to go. They say the trader is going to take some of their favorite chiefs there to figure for the 90,000 dollars & they wish to go to head them off and save some of it if possible. A nocturnal council was held soon after you left in the old mission building, by some of the traders with some of the Indians, & an effort was made to get them Indians to sign a paper requesting that Mr. H.M. Rice be paid $5000 for goods sold out of the 90,000 that be the Inland Indians be paid at Chippeway River & that the said H.M. Rice be appointed agent. The Lake du Flambeau Indians would not come into the [meeting?] & divulged the secret to Blackbird. They wish to be present at [Shington?] to head off [sail?] in that direction. I told Blackbird I thought it doubtful whether I could go with him, was for borrowing money & starting immediately down the Lake this fall, but I advised him to write you first & see what you thought about the desirability of his going, & know whether his expenses would be born. Most of the claimants would be dread to see him there, & of course would not encourage his going. I am not at all certain certain that I will be [considered?] for me to go with Blackbird, but if the Dept. think it desirable, I will take it into favorable consideration. Mr. Smith said he should try to be there & thought I had better go if I could. The fact is there is so much fraud and corruption connected with this whole matter that I dread to have anything to do with it. There is hardly a spot in the whole mess upon which you can put your finger without coming in contact with the deadly virus. In regard to the Priest’s coming here, The trader the Indians refer to is Antoine [Gordon?], a half breed. He has erected a small store house here & has brought goods here & acknowledges that he has sold them and defies the Employees. Mssrs. Van Tassel & Stoddard to help [themselves?] if they can. He is a liquer-seller & a gambler. He is now putting up a house of worship, by contract for the Catholic Priest. About what the Indians said about his coming here is true. In order to ascertain the exact truth I went to the Priest myself, with Mr. Stoddard, Govt [S?] man Carpenter. His position is that the Govt have no right to interfere in matters of religion. He says he has a right to come here & put up a church if there are any of his faith here, and they permit him to build on his any of their claims. He says also that Mr. Godfrey got permission of Mr. Gilbert to come here. I replied to him that the Commissioner told me that it was not the custom of the Gov. to encourage but one denomination of Christians in a place. Still not knowing exactly the position of Govt upon the subject, I would like to ask the following questions.

1. When one Missionary Society has already commenced labors a station among a settlement of Indians, and a majority of the Indians people desire to have him for their religious teacher, have missionaries of another denomination a right to come in and commence a missionary establishment in the same settlement?

Have they a right to do it against the will of a majority of the people?

Have they a right to do it in any case without the permission of the Govt?

Has any Indian a right, by sold purchase, lease or otherwise a right to allow a missionary to build on or occupy a part of his claim? Or has the same missionary a right to arrange with several missionaries Indians for to occupy by purchase or otherwise a part of their claims severally? I ask these questions, not simply with reference to the Priest, but with regard to our own rights & privileges in case we wish to commence another station at any other point on the reserve. The coming of the Catholic Priest here is a [mere stroke of policy, concocted?] in secret by such men as Mssrs. Godfrey & Noble to destroy or cripple the protestant mission. The worst men in the country are in favor of the measure. The plan is under the wing of the priest. The plan is to get in here a French half breed influence & then open the door for the worst class of men to come in and com get an influence. Some of the Indians are put up to believe that the paper you gave Blackbird is a forgery put up by the mission & Govt employ as to oppress their mission control the Indians. One of the claimants, for whom Mr. Noble acts as attorney, told me that the same Mr. Noble told him that the plan of the attorneys was to take the business of the old debts entirely out of your hands, and as for me, I was a fiery devil they when they much[?] tell their report was made out, & here what is to become of me remains to be seen. Probably I am to be hung. If so, I hope I shall be summoned to Washington for [which purpose?] that I may be held up in [t???] to all missionaries & they be [warned?] by my […]

The dramatic ending to this letter certainly reveals the intensity of the situation here in the fall of 1855. It also reveals the intensity of Wheeler’s hatred for the Roman Catholic faith, and by extension, the influence of the Catholic mix-blood portion of the La Pointe Band. This makes it difficult to view the Protestant missionary as any kind of impartial advocate for justice. Whatever was going on, he was right in the middle of it.

So, what did happen here?

From Morse, McElroy, and these two letters, it’s clear that Blackbird was doing whatever he could to stop the Government from paying annuity funds directly to the creditors. According to Wheeler, these men were led by U.S. Senator and fur baron Henry Mower Rice. It’s also clear that a significant minority of the Ojibwe, including most of the La Pointe mix-bloods, did not want to see the money go directly to the chiefs for disbursement.

I haven’t uncovered whether the creditors’ claims were accepted, or what Manypenny wrote back to Blackbird and Wheeler, but it is not difficult to guess what the response was. Wheeler, a Massachusetts-born reformist, had been able to influence Indian policy a few years earlier during the Whig administration of Millard Fillmore, and he may have hoped for the same with the Democrats. But this was 1855. Kansas was bleeding, the North was rapidly turning toward “Free Soil” politics, and the Dred Scott case was only a few months away. Franklin Pierce, a Southern-sympathizer had won the presidency in a landslide (losing only Massachusetts and three other states) in part because he was backed by Westerners like George Manypenny and H. M. Rice. To think the Democratic “Indian Ring,” as it was described above, would listen to the pleas coming from Odanah was optimistic to say the least.

“[E]xample not to meddle with other peoples business” is written at the top of Wheeler’s draft. It is his handwriting, but it is much darker than the rest of the ink and appears to have been added long after the fact. It doesn’t say it directly, but it seems pretty clear Wheeler didn’t look back on this incident as a success. I’ll keep looking for proof, but for now I can say with confidence that the request for a Washington delegation was almost certainly rejected outright.

So who are the good guys in this situation?

If we try to fit this story into the grand American narrative of Manifest Destiny and the systematic dispossession of Indian peoples, then we would have to conclude that this is a story of the Ojibwe trying to stand up for their rights against a group of corrupt traders. However, I’ve never had much interest in this modern “Dances With Wolves” version of Indian victimization. Not that it’s always necessarily false, but this narrative oversimplifies complex historical events, and dehumanizes individual Indians as much as the old “hostile savages” framework did. That’s why I like to compare the Chequamegon story more to the Canadian narrative of Louis Riel and company than to the classic American Little Bighorn story. The dispossession and subjugation of Native peoples is still a major theme, but it’s a lot messier. I would argue it’s a lot more accurate and more interesting, though.

So let’s evaluate the individuals involved rather than the whole situation by using the most extreme arguments one could infer from these documents and see if we can find the truth somewhere in the middle:

Henry Mower Rice (Wikimedia Images)

Henry M. Rice

The case against: H. M. Rice was businessman who valued money over all else. Despite his close relationship with the Ho-Chunk people, he pressed for their 1847 removal because of the enormous profits it brought. A few years later, he was the driving force behind the Sandy Lake removal of the Ojibwe. Both of these attempted removals came at the cost of hundreds of lives. There is no doubt that in 1855, Rice was simply trying to squeeze more money out of the Ojibwe.

The case for: H. M. Rice was certainly a businessman, and he deserved to be paid the debts owed him. His apparent actions in 1855 are the equivalent of someone having a lien on a house or car. That money may have justifiably belonged to him. As for his relationship with the Ojibwe, Rice continued to work on their behalf for decades to come, and can be found in 1889 trying to rectify the wrongs done to the Lake Superior bands when the reservations were surveyed.

From In Unnamed Wisconsin pg. 168. It’s not hard to figure out which Minnesota senator is being referred to here in this 1895 work informed by Harriet Wheeler. (Digitized by Google Books).

Antoine Gordon from Noble Lives of a Noble Race (pg. 207) published by the St. Mary’s Industrial School in Odanah.

Antoine Gordon

The case against: Antoine Gaudin (Gordon) was an unscrupulous trader and liquor dealer who worked with H. M. Rice to defraud his Ojibwe relatives during the 1855 annuities. He then tried to steal land and illegally squat on the Bad River Reservation against the expressed wishes of Chief Blackbird and Commissioner Manypenny.

The case for: Antoine Gordon couldn’t have been working against the Ojibwe since he was an Ojibwe man himself. He was a trader and was owed debts in 1855, but most of the criticism leveled against him was simply anti-Catholic libel from Leonard Wheeler. Antoine was a pious Catholic, and many of his descendants became priests. He built the church at Bad River because there were a number of people in Bad River who wanted a church. Men like Gordon, Vincent Roy Jr., and Joseph Gurnoe were not only crucial to the development of Red Cliff (as well as Superior and Gordon, WI) as a community, they were exactly the type of leaders the Ojibwe needed in the post-1854 world.

Portrait of Naw-Gaw-Nab (The Foremost Sitter) n.d by J.E. Whitney of St. Paul (Smithsonian)

Naaganab

The case against: Chiefs like Naaganab and Young Buffalo sold their people out for a quick buck. Rather than try to preserve the Ojibwe way of life, they sucked up to the Government by dressing like whites, adopting Catholicism, and using their favored position for their own personal gain and to bolster the position of their mix-blooded relatives.

The case for: If you frame these events in terms of Indians vs. Traders, you then have to say that Naaganab, Young Buffalo, and by extension Chief Buffalo were “Uncle Toms.” The historical record just doesn’t support this interpretation. The elder Buffalo and Naaganab each lived for nearly a century, and they each strongly defended their people and worked to preserve the Ojibwe land base. They didn’t use the same anti-Government rhetoric that Blackbird used at times, but they were working for the same ends. In fact, years later, Naaganab abandoned his tactic of assimilation as a means to equality, telling Rice in 1889:

“We think the time is past when we should take a hat and put it on our heads just to mimic the white man to adopt his custom without being allowed any of the privileges that belong to him. We wish to stand on a level with the white man in all things. The time is past when my children should stand in fear of the white man and that is almost all that I have to say (Nah-guh-nup pg. 192).”

Leonard H. Wheeler

L. H. Wheeler (WHS Image ID 66594)

The case against: Leonard Wheeler claimed to be helping the Ojibwe, but really he was just looking out for his own agenda. He hated the Catholic Church and was willing to do whatever it took to keep the Catholics out of Bad River including manipulating Blackbird into taking up his cause when the chief was the one in need. Wheeler couldn’t mind his own business. He was the biggest enemy the Ojibwe had in terms of trying to maintain their traditions and culture. He didn’t care about Blackbird. He just wanted the free trip to Washington.

The case for: In contrast to Sherman Hall and some of the other missionaries, Leonard Wheeler was willing to speak up forcefully against injustice. He showed this during the Sandy Lake removal and again during the 1855 payment. He saw the traders trying to defraud the Ojibwe and he stood up against it. He supported Blackbird in the chief’s efforts to protect the territorial integrity of the Bad River reservation. At a risk to his own safety, he chose to do the right thing.

Blackbird

The case against: Blackbird was opportunist trying to seize power after Buffalo’s death by playing to the outdated conservative impulses of his people at a time when they should have been looking to the future rather than the past. This created harmful factional differences that weakened the Ojibwe position. He wanted to go to Washington because it would make him look stronger and he manipulated Wheeler into helping him.

The case for: From the 1840s through the 1860s, the La Pointe Ojibwe had no stronger advocate for their land, culture, and justice than Chief Blackbird. While other chiefs thought they could work with a government that was out to destroy them, Blackbird never wavered, speaking consistently and forcefully for land and treaty rights. The traders, and other enemies of the Ojibwe, feared him and tried to keep their meetings and Washington trip secret from him, but he found out because the majority of the people supported him.

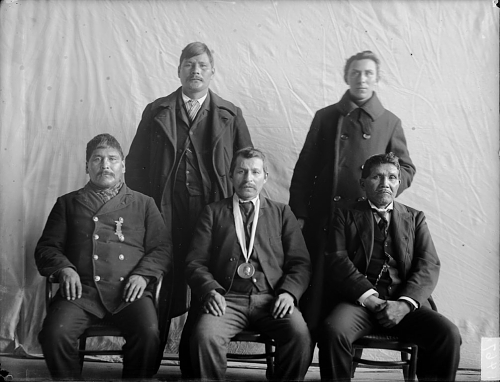

I’ve yet to find a picture of Blackbird, but this 1899 Bad River delegation to Washington included his son James (bottom right) along with Henry and Jack Condecon, George Messenger, and John Medegan–all sons and/or grandsons of signers of the Treaty of 1854 (Photo by De Lancey Gill; Smithsonian Collections).

Final word for now…

An entire book could be written about the 1855 annuity payments, and like so many stories in Chequamegon History, once you start the inquiry, you end up digging up more questions than answers. I can’t offer a neat and tidy explanation for what happened with the debts. I’m inclined to think that if Henry Rice was involved it was probably for his own enrichment at the expense of the Ojibwe, but I have a hard time believing that Buffalo, Jayjigwyong, Naaganab, and most of the La Pointe mix-bloods would be doing the same. Blackbird seems to be the hero in this story, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if there was a political component to his actions as well. Wheeler deserves some credit for his defense of a position that alienated him from most area whites, but we have to take anything he writes about his Catholic neighbors with a grain of salt.

As for the Blackbird-Wheeler relationship, showcasing these two fascinating letters was my original purpose in writing this post. Was Blackbird manipulating Wheeler, was Wheeler manipulating Blackbird, or was neither manipulating the other? Could it be that the zealous Christian missionary and the stalwart “pagan” chief, were actually friends? What do you think?

Sources:

Davidson, J. N., and Harriet Wood Wheeler. In Unnamed Wisconsin: Studies in the History of the Region between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi. Milwaukee, WI: S. Chapman, 1895. Print.

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

McElroy, Crocket. “An Indian Payment.” Americana v.5. American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Pupil’s of St. Mary’s, and Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration. Noble Lives of a Noble Race. Minneapolis: Brooks, 1909. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Capitol Busts

July 17, 2013

This post is one of several that seek to determine how many images exist of Great Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855. To learn why this is necessary, please read this post introducing the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

Posts on Chequamegon History are generally of the obscure variety and are probably only interesting to a handful of people. I anticipate this one could cause some controversy as it concerns an object that holds a lot of importance to many people who live in our area. All I can say about that is that this post represents my research into original historical documents. I did not set out to prove anybody right or wrong, and I don’t think this has to be the last word on the subject. This post is simply my reasoned conclusions based on the evidence I’ve seen. Take from it what you will.

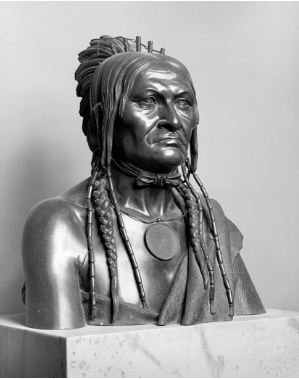

Be sheekee, or Buffalo by Francis Vincenti, Marble, Modeled 1855, Carved 1856 (United States Senate)

Be Sheekee: A Chippewa Warrior from the Sources of the Mississippi, bronze, by Joseph Lassalle after Francis Vincenti, House wing of the United States Capitol (U.S. Capitol Historical Society).

“A Chippewa Warrior from the Sources of the Mississippi”

There is no image that has been more widely identified with Chief Buffalo from La Pointe than the marble bust and bronze copy in the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington D.C. Red Cliff leaders make a point of visiting the statues on trips to the capital city, the tribe uses the image in advertising and educational materials, and literature from the United States Senate about the bust includes a short biography of the La Pointe chief.

I can trace the connection between the bust and the La Pointe chief to 1973, when John O. Holzhueter, editor of the Wisconsin Magazine of History wrote an article for the magazine titled Chief Buffalo and Other Wisconsin-Related Art in the National Capitol. From Holzhueterʼs notes we can tell that in 1973, the rediscovery of the story of the La Pointe Buffalo was just beginning at the Wisconsin Historical Society (the publisher of the magazine). Holzhueter deserves credit for helping to rekindle interest in the chief. However, he made a critical error.

In the article he briefly discusses Eshkibagikoonzhe (Flat Mouth), the chief of the Leech Lake or Pillager Ojibwe from northern Minnesota. Roughly the same age as Buffalo, Flat Mouth is as prominent a chief in the history of the upper Mississippi as Buffalo is for the Lake Superior bands. Had Holzhueter investigated further into the life of Flat Mouth, he may have discovered that at the time the bust was carved, the Pillagers had another leader who had risen to prominence, a war chief named Buffalo.

Holzhueter clearly was not aware that there was more than one Buffalo, and thus, he had to invent facts to make the history fit the art. According to the article (and a book published by Holzhueter the next year) the La Pointe Buffalo visited President Pierce in Washington in January of 1855. Buffalo did visit Washington in 1852 in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, but the old chief was nowhere near Washington in 1855. In fact, he was at home on the island in declining health having secured reservations for his people in Wisconsin the previous summer. He would die in September of 1855. The Buffalo who met with Pierce, of course, was the war chief from Leech Lake.

“He wore in his headdress 5 war-eagle feathers“

The Pillager Buffalo was in Washington for treaty negotiations that would transfer most of the remaining Ojibwe land in northern Minnesota to the United States and create reservations at the principal villages. The minutes of the February 1855 negotiations between the Minnesota chiefs and Indian Commissioner George Manypenny are filled with Ojibwe frustration at Manypennyʼs condescending tone. The chiefs, included the powerful young Hole-in-the-Day, the respected elder Flat Mouth, and Buffalo, who was growing in experience and age, though he was still considerably younger than Flat Mouth or the La Pointe Buffalo. The men were used to being called “red children” in communications with their “fathers” in the government, but Manypennyʼs paternalism brought it to a new low. Buffalo used his clothing to communicate to the commissioner that his message of assimilation to white ways was not something that all Ojibwes desired. Manypennyʼs words and Buffaloʼs responses as interpreted by the mix- blooded trader Paul Beaulieu follow:

The commissioner remarked to Buffalo, that if he was a young man he would insist upon his dispensing with his headdress of feathers, but that, as he was old, he would not disturb a custom which habit had endeared to him.

Buffalo repoled ithat the feathered plume among the Chippewas was a badge of honor. Those who were successful in fighting with or conquering their enemies were entitled to wear plumes as marks of distinction, and as the reward of meritorious actions.The commissioner asked him how old he was.

Buffalo said that was a question which he could not answer exactly. If he guessed right, however, he supposed he was about fifty. (He looked, and was doubtless, much

older).Commissioner. I would think, my firend, you were older than that. I would like to philosophise with you about that headdress, and desired to know if he had a farm, a house, stock, and other comforts about him.

Buffalo. I have none of those things which you have mentioned. I live like other members of the tribe.

Commissioner. How long have you been in the habit of painting—thirty years or more?

Buffalo. I can not tell the number of years. It may have been more or it may have been less. I have distinguished myself in war as well as in peace among my people and the whites, and am entitled to the distinction which the practice implies.

Commissioner. While you, my firend, have been spending your time and money in painting your face, how many of your white brothers have started without a dollar in the world and acquired all those things mentioned so necessary to your comfort and independent support. The paint, with the exception of what is now on my friend’s face, has disappeared, but the white persons to whom I alluded by way of contrast are surrounded by all the comforts of life, the legitimate fruits of their well-directed industry. This illustrates the difference between civilized and savage life, and the importance of our red brothers changing their habits and pursuits for those of the white.

Major General Montgomery C. Meigs was a Captain before the Civil War and was in charge of the Capitol restoration, As with Thomas McKenney in the 1820s, Meigs was hoping to capture the look of the “vanishing Indian.” He commissioned the busts of the Leech Lake chiefs during the 1855 Treaty negotiations. (Wikimedia Images)

While Manypenny clearly did not like the Ojibwe way of life or Buffaloʼs style of dress, it did catch the attention of the authorities in charge of building an extension on the U.S. Capitol. Captain Montgomery Meigs, the supervisor, had hired numerous artists and much like Thomas McKenney two decades earlier, was looking for examples of the indigenous cultures that were assumed to be vanishing. On February 17th, Meigs received word from Seth Eastman that the Ojibwe delegation was in town.

The Captain met Bizhiki and described him in his journal: