Who doesn’t love a good mystery?

In my continuing goal to actually add original archival research to this site, rather than always mooching off the labors of others, I present to you another document from the Wheeler Family Papers. Last week, I popped over to the Wisconsin Historical Society collections at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center in Ashland, and brought back some great stuff. Unlike the somber Sandy Lake letters I published July 11th, this first new document is a mysterious (and often hilarious) journal from 1843 and 1844.

It was in the Wheeler papers, but it was neither written by nor for one of the Wheelers. There is no name on it to indicate an author, and despite a year of entries, very little to indicate his occupation (unless he was a weatherman). He starts in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, bound for Fond du Lac, Minnesota–though neither was a state yet. Our guy reaches Lake Superior at a time of great change. The Ojibwe have just ceded the land in the Treaty of 1842, commercial traffic is beginning to start on Lake Superior, and the old fur-trade economy is dying out.

Our guy doesn’t seem to be a native of this area. He’s not married. He doesn’t seem to be strongly connected to the fur trade. If he works for the government, he isn’t very powerful. He is definitely not a missionary. He doesn’t seem to be a land speculator or anything like that.

Who is he, and why did he come here? I have some hunches, but nothing solid. Read it and let me know what you think.

1843

Aug. 24th 1843. left Taycheedah for Milwaukie on my route to Lake Superior, drove to Cases[?] in Fond du Lac

25th Drove to Cases on Milwaukie road, commenced rowing before we arrived, and we put up for the night.

26th Started in the rain, drove to Vinydans[?], rain all the time. wet my carpet bag and clothes—we put out 12 O’clock m. took clothes out of my traveling bag and dried them.

27th sunday Left early in the morning. arrived at Milwaukie at 12 O clock M. stayed at the Fountain house, had good fun.

Arch Rock, Mackinac Island (Jeffness upload to Wikimedia Commons CC)

28th Purchased provisions and other articles of outfit and embarked aboard the Steamboat Chesapeake for Mackinac 9 O’clock P. M. had a pleasant time.

30th Arrived at Mackinac 6 O’clock A.M. put up at Mr. Wescott’s had excellent fare and good company, charges reasonable. four Thousand Indian men encamped on the Island for Payment—very warm weather—Slept with windows raised, and uncomfortably warm. There are a few white families, but the mass of the people are a motley crowd “from snowy white to sooty[?],” I visited the curiosities, the old fort Holmes, the sugar loaf rock the arched rock—heard some good stories well told by Mr. Wescott and a gentleman from Philadelphia.

Sept 4th Left Mackinac on board the Steamer Gen. Scott 8 O’clock A. M. arrived at Sault St, Marie same night 6 O’clock—very pleasant weather. gardens look well. Put up at Johnsons. had good fare fish eggs fowls and garden vegetables.

7th Embarked on board the Brig John Jacob Astor for La Pointe. Sailed fifty miles. at midnight the wind shifted suddenly into the N.W. and blew a hurricane and we were obliged to run back into the St. Marie’s river, and lay there at Pine Point until Sunday.

10th when we best[?] out of the river, and proceeding on

1843

Sept 11th Monday heading against hard wind all day—

makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Photo: Smithsonian Institution; Definition: Ojibwe People’s Dictionary).

makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Photo: Smithsonian Institution; Definition: Ojibwe People’s Dictionary).12th Warm cloudless brilliant morning, a perfect calm—10 O’clock fair wind, and with every sail our vessel plows the deep, with majesty.

13th cloudy—fair wind, we arrive at La Pointe 9 O’clock P.M. when a cannon fired from on board the vessel announced our arrival.

Mr. Wheeler of the Presbyterian Mission was very kind in receiving me to room with him, and I am indebted to him and family for many acts of kindness during my stay at La Pointe, and I fell under [?] for about 15 lbs boiled beef and a small Mokuk of sugar, which they insisted on my taking on my departure for Fond du Lac, and which men[?] very p[?]able while wind on my way upon the shore of Lake Superior.

27th Left La Pointe about 4 O clock P. M. in small boat in company with the farmer & Blacksmith stationed at Fond du Lac. we rowed to Raspberry river and encamped.

28th Head wind—rowed to Siscowet Bay and encamped.

29th Rain and fair wind, we embarked about 8 O clock in the rain—in doubling Bark Point we got an Ocean more, but our little boat rides it nobly. the wind and rain increase, and we run into Pukwaekah river, the wind blowing directly on shore and the waves dashing to an enormous height, it was by miracle, our men chose, that struck the mouth of that small river, and entered in safety, After we had pitched our tent, we saw eight canoes with sails making directly for the river. they could not strike the entrance at the mouth of the river, and were driven on shore upon the beach and filled. We assisted in hauling our some of the first that came, and they assisted the rest.

1843

Sept 30th High wind and rain. We remained at this place until wednesday.

Oct 4th At 1 O clock A. M. the wind having abated we again embarked and rowed into the mouth of the St. Louis at 1 O clock P. M. I threw myself upon the bank, completely exhausted, and thankful to be once more on Terra firma, and determined to stay there until my strength should be reignited, however having taken dinner upon the bank and a cup of tea, the wind sprang up favorably and we sailed up the river ten miles and encamped upon an island.

5th Arrived at the A.M.F.’s Trading Post the place of our destination, at 10 O’clock A.M. (mild and pleasant from this time to the 24th weather has been remarkably.

24th Cold—snow and some ice in the river

26th The river froze over at this place.

27th Colder the ice makes fast in the river

Nov 1st Crossed the river on the ice—winter weather—

2nd Moderate

5th Sunday warm the ice is failing in the river dangerous crossing on foot

7th and 8th Warm and pleasant—the ice is melting

9th Warm and misty—thawing fort

20th Warm—rains a little—the river is nearly clean of ice—

Dec. 3rd The weather up to this date has been very mild. No snow, the ice on the river scarcely sufficient to bear a horse and train—

Jan 1st 1844 Warm and misty—more like April fool than New years day

1844

Jan 1st On this day I must record the honor of being visited by some half dozen pretty squaws expecting a New Years present and a kiss, not being aware of the etiquette of the place, we were rather taken by surprise, in not having presents prepared—however a few articles were mustered, an I must here acknowledge that although, out presents were not very valuable, we were entitled to the reward of a kiss, which I was ungallant enough not to claim, but they’ll never slip through my fingers in that way again.

March 2nd New sugar, weather pleasant

3rd Cloudy chilly wind

Bebiizigindibe (Curly Head) signed the Treaty of 1842 as 2nd Chief from Gull Lake. According to William Warren, he was known as “Little Curly Head.” “Big Curly Head” was a famous Gull Lake war chief who died in 1825 while returning home from the Treaty of Prairie du Chien. The younger chief was the son of Niigaani-giizhig (also killed by the Dakota), and the half-brother of Gwiiwizhenzhish or Bad Boy (pictured). According to Warren, this incident broke a truce between the two nations (Photo by Whitney’s of St. Paul, Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society).

17th Pleasant, two Indians arrive and bring the news that the chief of the Gull Lake band of Chippeways has been killed by the Sioux—there appears to be not much excitement among the Indians here upon the subject. The name of the chief that is killed is Babezegondeba (Curly Head)

The winter has been remarkably mild and pleasant—but little snow—no tedious storms and but two or three cold days.

31st A cloudy brilliant day—The frogs are singing

April 1st A lovely spring morning—warm—the Ducks are flying

Afternoon a little cloudy but warm

Evening, moonlight—beautiful and bright

2nd Warm morning. afternoon high wind rain

A pleasant moonlight evening—warm

3rd Briliant morning—warm afternoon appearance of rain. the ice is moving out of the river Ducks & Geese are flying and we have fresh fish

4th Clean cold morning wind N.E. afternoon high wind chilly. The clear of ice at this place.

5th Cold cloudy morning. Wind NE. After noon wind and rain from the N.E.

1844

April

6th Wind N.E. continues to rain moderately again—thunder and rain during the past night.

7th Sunday. warm rainy day—attended church

8th Cloudy morning and warm, afternoon very fair.

9th Fair frosty morning, afternoon very warm.

10th Cloudy and warm—thunder lightning and rain during the past night, afternoon fair and warm.

11th Rainy warm morning, with thunder and lightning afternoon fair and very warm.

12th Fair warm morning, after noon, cloudy with a little rain thunder and lightning—Musketoes appear

13th Most beautiful spring morning—fair warm day, wind S.W.

14th Cool cloudy day—Wind N.E. (Sunday)

15th Rainy, warm day

16th Fair cool morning—after noon warmer

17th Fair and warm day (Striker started for La Pointe Bellanger with the Blacksmith)

18th Another beautiful day.

19th Warm rainy day

20th Rainy day

21st Sunday fair and cool—high wind from N.E.

22nd Cool morning—some cloudy—P.M. high wind and rain

23rd High wind and rain from the N.E.—tremendous storm;

24th Fair morning moderately warm—afternoon fair. Musketoes

25th Rainy day

26th Cool cloudy morning

27th} fair & warm

28th

29th Beautiful April day

30th Rainy day

May 1st Warm with high wind

2nd Do. a little rain

3rd Warm—sunshine and showers

4th} Beautiful warm day

5th

6th Most beautiful brilliant day

the woods have already a shade of green

1844

May 7th Warm rainy day

June 21st Since the last date the weather has been good for the season—during the month of may occasionally a frosty night with sufficient variety of sunshine and shower. On this day I started for La Pointe in company with the farmer, the Blacksmith & Striker, and Indian, named Red Bird, in a small boat. we rowed to the River Aminicon and encamped.

22nd Three O’clock A.M. Struck our tent and embarked—took the oars, (about 6 O’clock met a large batteau from La Pointe Bound for Fond du Lac with seed Potatoes for the Indians, it also had letters for Fond du Lac, among which was one for my self—The farmer returned to Fond du Lac to attend to the distribution of the Potatoes. We breakfasted at Burnt wood River. about 7 O’clock The wind sprang up favorably and blew a steady strong blast all day, and we arrived at La Pointe about sun set.

23rd Sunday, attended church

24th Did nothing in particular—weather very warm

28th Was taken suddenly with crick in the back which laid me up for a week

July 4th Independence day—Just able to get about The batteaus were fitted out by Dr. Borup for a pleasure ride, by way of celebrating the birth day of American Independence—These boats were propelled by eight sturdy Canadian voyagers each, nearly all the inhabitants of La Pointe were on board, and I was among the number, we were conveyed , amidst the firing of pocket pistols, rifles, shot guns & the music and mirth of the half-breeds and the mild cadence of the Canadian Boat songs, to one of the Islands of the Apostles about ten miles distant from La Pointe. Here we disembarked and partook of a sumptuous dinner which had been prepared and brought on board the boats.

The brig John Jacob Astor, named for the fur baron pictured above, was one of the earliest commercial vessels on Lake Superior. It sank near Copper Harbor about two months after the La Pointe Independence Day celebration (Painting by Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Images).

Just as we had finished the repast, having done ample justice to the viands which were placed before us, Some one, by means of a large spy glass discovered the Brig Astor supposed to be about 10 or 15 miles distant beating for La Pointe in thirty minutes we were all on board our boats and bound to meet the Astor. The Canadians were all commotion, and rowed and sung with all their might for about eight miles when finding that we yet a long distance from the vessel, she making little head way, and it being past middle of the afternoon, the question arose whether we should go forward or return to La Pointe. a vote was taken, but as the chairman was unable to decide which party carried the point, he said he should be under the necessity of dividing the boat. this was accordingly done, and all those who were desirous to go a head, took one boat, and those who wished to return the other. I was anxious to go and meet the vessel, but being unwell was advised to return, and did so, and arrived at La Pointe at dusk.

July 11th Started from La Pointe for Fond du Lac with Mr. Johnson & Lady missionaries at Leech Lake. Mr. Hunter the Blacksmith, and two Indians, in our small boat. sailed about three miles a squall came up suddenly and drove us back to La Pointe—Started again after noon and rowed to Sandy River and encamped next

12th day rowed to Burnt wood (Iron) river.

13th Arrived at Fond du Lac 9 O’clock P.M.

Aug 6th Since I arrived the weather has been intensely warm Yesterday Mr. Hunter started for La Pointe to attend the Payment. I am alone

Erethizon dorsatum, North American Porcupine: I’m going to assume our author devoured one of these guys. Hedgehogs are exclusively an Old World animal (J. Glover, Wikimedia Images, CC)

Aug 27th The weather fair, the nights begin to be cooler. Musketoes and gnats have given up the contest and left us in full and peaceable possession of the country. Since Mr. hunter left for the payment I have been unwell, no appetite, foul stomac, after trying various remedies, in order to settle my stomac, I succeeded in effecting it at last by devouring a large portion of roast Hedge hog But was immediately taken down with a rheumatism in my back, which has held me to the present time and from which I am just recovering.

An Indian has just arrived from Leech Lake bringing news that the Sioux have killed a chippeway and that the Chippeways in retaliation have killed eight Sioux.

29th Johnson arrived from La Pointe—Rainy day.

31st The farmer and Blacksmith arrived from La Pointe

The weather is very warm—

Sept 5 Weather continues warm. Mr. Wright Mr Coe and wife start for Red Lake (they are Missionaries)

10 Frosty night

11 Do. “

12 Cloudy and warm

13 Do. Do. “

14 Do. Do. Do. Batteau arrived from La Pointe

15 Sunday foggy morning—very warm fair day

16 Warm

22 Do.

29 fair

Oct 3rd Warm and fair

Sunday 13th fair days & frosty nights, this month, thus far

14-15 Rainy days

19th cold

20 Snow covers the ground—the river is nightly frozen over at some places—

21 fine day

22&23 fair & warm thunder & lightning at night

24th Do. Do. (Agent arrived from La Pointe 28th)

28th Cold—snow in the afternoon and night

—————————————————————————————————————–

END OF 1843-44 JOURNAL

The last two pages of the document are written in the same handwriting, a few years later in 1847, and take the form of a cash ledger.

________________________________________________________________

| 1847 | Madam Defoe [?][?] 1847 | ||||

| Dec 3rd | [?] | [?] | |||

| p/o 4 lbs Butter | 1 | 00 | |||

| “ | “ 3 Gallons Soap | 1 | 00 | ||

| 15th | By Making 2 pr Moccasins | 50 | |||

| “ | [Washing 2 Down pieces ?] | 1 | 00 | ||

| “ | Mending pants [?] | 25 | |||

| Joseph Defoe Jr | |||||

| p/o 50 lbs Candles | 1 | 50 | |||

| “ 10 “ Pork | 1 | 50 | |||

| “ 20 “ flour | 1 | 25 | |||

| By three days work by self and son | 3 | 75 | |||

| p/o Pork 4 lbs | 50 | ||||

____________________________________________________________________________

| 1847 | Memorandum | ||||

| Aug | Went to La Pointe with Carleton | ||||

| Staid four days | |||||

| Oct 9th | Went to La Pointe (Monday) | ||||

| 12 | Returned 4 O’clock P.M. | ||||

| 16 | Went to La Pointe. returned same night | ||||

| 24th | Do. Do. | ||||

| 25th | Returned | ||||

| Nov. 28th | Lent Mr. Wood 10 lbs nails– | ||||

| 5 lbs 4[?] 5 lbs 10[?] previous to this time 12 lbs | |||||

| 4[?] Total= 22 lbs | |||||

| By three days work by self and son | |||||

| p/o Pork 4 lbs | |||||

| Nov | T.A. Warren Due to Cash | 2 | 00 | ||

Truman A. Warren, son of Lyman Warren and Marie Cadotte Warren, brother of Willam W. (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: 28289)

Truman A. Warren, son of Lyman Warren and Marie Cadotte Warren, brother of Willam W. (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: 28289)____________________________________________________________________________

While not overly significant historically, I enjoyed typing up this anonymous journal. The New Years, Independence Day, and “Hedge Hog” stories made me laugh out loud. You just don’t get that kind of stuff from an uptight missionary, greedy trader, or boring government official. It really makes me want to know who this guy was. If you can identify him, please let me know.

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 21 June 2012. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1995. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1853. Print.

Warren, William W., and Edward D. Neill. History of the Ojibway Nation. Minneapolis: Ross & Haines, 1957. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Introduction

May 26, 2013

Click the question mark under the picture to see if it shows Chief Buffalo.

?

?

Buffalo, the 19th-century chief of the La Pointe Ojibwe, is arguably the most locally-famous person in history of the Chequamegon region. He is best known for his 1852 trip to Washington D.C., undertaken when he was thought to be over ninety years old. Buffalo looms large in the written records of the time, and makes many appearances on this website.

He is especially important to the people of Red Cliff. He is the founding father of their small community at the northern tip of Wisconsin in the sense that in the Treaty of 1854, he negotiated for Red Cliff (then called the Buffalo Estate or the Buffalo Bay Reservation) as a separate entity from the main La Pointe Band reservation at Bad River. Buffalo is a direct ancestor to several of the main families of Red Cliff, and many tribal members will proudly tell of how they connect back to him. Finally, Buffaloʼs fight to keep the Ojibwe in Wisconsin, in the face of a government that wanted to move them west, has served as an inspiration to those who try to maintain their cultural traditions and treaty rights. It is unfortunate, then, that through honest mistakes and scholarly carelessness, there is a lot of inaccurate information out there about him.

During the early twentieth century, the people of Red Cliff maintained oral traditions about about his life while the written records were largely being forgotten by mainstream historians. However, the 1960s and ʻ70s brought a renewed interest in American Indian history and the written records came back to light. With them came no fewer than seven purported images of Buffalo, some of them vouched for by such prestigious institutions as the State Historical Society of Wisconsin and the U.S. Capitol. These images, ranged from well-known lithographs produced during Buffaloʼs lifetime, to a photograph taken five years after he died, to a symbolic representation of a clan animal originally drawn on birch bark. These images continue to appear connected to Buffalo in both scholarly and mainstream works. However, there is no proof that any of them show the La Pointe chief, and there is clear evidence that several of them do not show him.

The problem this has created is not merely one of mistaken identity in pictures. To reconcile incorrect pictures with ill-fitting facts, multiple authors have attempted to create back stories where none exist, placing Buffalo where he wasnʼt, in order for the pictures to make sense. This spiral of compounding misinformation has begun to obscure the legacy of this important man, and therefore, this study attempts to sort it out.

Bizhikiwag

The confusion over the images stems from the fact that there was more than one Ojibwe leader in the mid-nineteenth century named Bizhiki (Buffalo). Because Ojibwe names are descriptive, and often come from dreams, visions, or life experiences, one can be lead to believe that each name was wholly unique. However, this is not the case. Names were frequently repeated within families or even outside of families. Waabojiig (White Fisher) and Bugone-Giizhig (Hole in the Day) are prominent examples of names from Buffaloʼs lifetime that were given to unrelated men from different villages and clans. Buffalo himself carried two names, neither of which was particularly unique. Whites usually referred to him as Buffalo, Great Buffalo, or LaBoeuf, translations of his name Bizhiki. In Ojibwe, he is just as often recorded by the name Gichi-Weshkii. Weshkii, literally “new one,” was a name often given to firstborn sons in Ojibwe families. Gichi is a prefix meaning “big” or “great,” both of which could be used to describe Buffalo.

Nichols and Nyholm translate Bizhiki (Besheke, Peezhickee, Bezhike, etc.) as both “cow” and “buffalo.” Originally it meant “buffalo” in Ojibwe. As cattle became more common in Ojibwe country, the term expanded to include both animals to the point where the primary meaning of the word today is “cow” in some dialects. These dialects will use Mashkodebizhiki (Prairie Cow) to mean buffalo. However, this term is a more recent addition to the language and was not used by individuals named Buffalo in the mid- nineteenth century. (National Park Service photo)

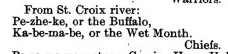

One glance at the 1837 Treaty of St. Peters shows three Buffalos. Pe-zhe-kins (Bizhikiins) or “Young Buffalo” signed as a warrior from Leech Lake. “Pe-zhe-ke, or the Buffalo” was the first chief to sign from the St. Croix region. Finally, the familiar Buffalo is listed as the first name under those from La Pointe on Lake Superior. It is these two other Buffalos, from St. Croix and Leech Lake, whose faces grace several of the images supposedly showing Buffalo of La Pointe. All three of these men were chiefs, all three were Ojibwe, and all three represented their people in Washington D.C. Because they share a name, their histories have unfortunately been mashed together.

Who were these three men?

Treaty of St. Peters (1837) For more on Dagwagaane (Ta-qua-ga-na), check out the People Index.

The familiar Buffalo was born at La Pointe in the middle of the 18th century. He was a member of the Loon Clan, which had become a chiefly clan under the leadership of his grandfather Andeg-wiiyas (Crowʼs Meat). Although he was already elderly by the time the Lake Superior Ojibwe entered into their treaty relationship with the United States, his skills as an orator were such that by the Treaty of 1854, one year before his death, Buffalo was the most influential leader not only of La Pointe, but of the whole Lake Superior country.

Treaty of St. Peters (1837) For more on Gaa-bimabi (Ka-be-ma-be), check out the People Index.

William Warren, describes the St. Croix Buffalo as a member of the Bear Clan who originally came to the St. Croix from Sault Ste. Marie after committing a murder. He goes on to declare that this Buffaloʼs chieftainship came only as a reward from traders who appreciated his trapping skills. Warren does admit, however, that Buffaloʼs influence grew and surpassed that of the hereditary St. Croix leaders.

Treaty of St. Peters (1837) For more on Flat Mouth, check out the People Index.

The “Young Buffalo,” of the Pillager or Leech Lake Ojibwe of northern Minnesota was a war chief who also belonged to the Bear Clan and was considerably younger than the other two Buffalos (the La Pointe and St. Croix chiefs were about the same age). As Biizhikiins grew into his later adulthood, he was known simply as Bizhiki (Buffalo). His mark on history came largely after the La Pointe Buffaloʼs death, during the politics surrounding the various Ojibwe treaties in Minnesota and in the events surrounding the US-Dakota War of 1862.

The Picture Search

In the coming months, I will devote several posts to analyzing the reported images of Chief Buffalo that I am aware of. The first post on this site can be considered the first in the series. Keep checking back for more.

Sources:

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 21 June 2012. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1995. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers: With Brief Notices of Passing Events, Facts, and Opinions, A.D. 1812 to A.D. 1842. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and, 1851. Print.

Treuer, Anton. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul, MN: Borealis, 2010. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

No Princess Zone: Hanging Cloud, the Ogichidaakwe

May 12, 2013

This image of Aazhawigiizhigokwe (Hanging Cloud) was created 35 years after the battle depicted by Marr and Richards Engraving of Milwaukee for use in Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).

Here is an interesting story I’ve run across a few times. Don’t consider this exhaustive research on the subject, but it’s something I thought was worth putting on here.

In late 1854 and 1855, the talk of northern Wisconsin was a young woman from from the Chippewa River around Rice Lake. Her name was Ah-shaw-way-gee-she-go-qua, which Morse (below) translates as “Hanging Cloud.” Her father was Nenaa’angebi (Beautifying Bird) a chief who the treaties record as part of the Lac Courte Oreilles band. His band’s territory, however, was further down the Chippewa from Lac Courte Oreilles, dangerously close to the territories of the Dakota Sioux. The Ojibwe and Dakota of that region had a long history of intermarriage, but the fallout from the Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1825) led to increased incidents of violence. This, along with increased population pressures combined with hunting territory lost to white settlement, led to an intensification of warfare between the two nations in the mid-18th century.

As you’ll see below, Hanging Cloud gained her fame in battle. She was an ogichidaakwe (warrior). Unfortunately, many sources refer to her as the “Chippewa Princess.” She was not a princess. Her father was not a king. She did not sit in a palace waited on hand and foot. Her marriageability was not her only contribution to her people. Leave the princesses in Europe. Hanging Cloud was an ogichidaakwe. She literally fought and killed to protect her people.

Americans have had a bizarre obsession with the idea of Indian princesses since Pocahontas. Engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe (1616) Wikimedia Images

Americans have had a bizarre obsession with the idea of Indian princesses since Pocahontas. Engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe (1616) Wikimedia ImagesIn An Infinity of Nations, Michael Witgen devotes a chapter to America’s ongoing obsession with the concept of the “Indian Princess.” He traces the phenomenon from Pocahontas down to 21st-century white Americans claiming descent from mythical Cherokee princesses. He has some interesting thoughts about the idea being used to justify the European conquest and dispossession of Native peoples. I’m going to try to stick to history here and not get bogged down in theory, but am going to declare northern Wisconsin a “NO PRINCESS ZONE.”

Ozhaawashkodewekwe, Madeline Cadotte, and Hanging Cloud were remarkable women who played a pivotal role in history. They are not princesses, and to describe them as such does not add to their credit. It detracts from it.

Anyway, rant over, the first account of Hanging Cloud reproduced here comes from Dr. Richard E. Morse of Detroit. He observed the 1855 annuity payment at La Pointe. This was the first payment following the Treaty of 1854, and it was overseen directly by Indian Affairs Commissioner George Manypenny. Morse records speeches of many of the most prominent Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs at the time, records the death of Chief Buffalo in September of that year, and otherwise offers his observations. These were published in 1857 as The Chippewas of Lake Superior in the third volume of the State Historical Society’s Wisconsin Historical Collections. This is most of pages 349 to 354:

“The “Princess”–AH-SHAW-WAY-GEE-SHE-GO-QUA–The Hanging Cloud.

The Chippewa Princess was very conspicuous at the payment. She attracted much notice; her history and character were subjects of general observation and comment, after the bands, to which she was, arrived at La Pointe, more so than any other female who attended the payment.

She was a chivalrous warrior, of tried courage and valor; the only female who was allowed to participate in the dancing circles, war ceremonies, or to march in rank and file, to wear the plumes of the braves. Her feats of fame were not long in being known after she arrived; most persons felt curious to look upon the renowned youthful maiden.

Nenaa’angebi as depicted on the cover of Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).

Nenaa’angebi as depicted on the cover of Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).She is the daughter of Chief NA-NAW-ONG-GA-BE, whose speech, with comments upon himself and bands, we have already given. Of him, who is the gifted orator, the able chieftain, this maiden is the boast of her father, the pride of her tribe. She is about the usual height of females, slim and spare-built, between eighteen and twenty years of age. These people do not keep records, nor dates of their marriages, nor of the birth of their children.

This female is unmarried. No warrior nor brave need presume to win her heart or to gain her hand in marriage, who cannot prove credentials to superior courage and deeds of daring upon the war-path, as well as endurance in the chase. On foot she was conceded the fleetest of her race. Her complexion is rather dark, prominent nose, inclining to the Roman order, eyes rather large and very black, hair the color of coal and glossy, a countenance upon which smiles seemed strangers, an expression that indicated the ne plus ultra of craft and cunning, a face from which, sure enough, a portentous cloud seemed to be ever hanging–ominous of her name. We doubt not, that to plunge the dagger into the heart of an execrable Sioux, would be more grateful to her wish, more pleasing to her heart, than the taste of precious manna to her tongue…

…Inside the circle were the musicians and persons of distinction, not least of whom was our heroine, who sat upon a blanket spread upon the ground. She was plainly, though richly dressed in blue broad-cloth shawl and leggings. She wore the short skirt, a la Bloomer, and be it known that the females of all Indians we have seen, invariably wear the Bloomer skirt and pants. Their good sense, in this particular, at least, cannot, we think, be too highly commended. Two plumes, warrior feathers, were in her hair; these bore devices, stripes of various colored ribbon pasted on, as all braves have, to indicate the number of the enemy killed, and of scalps taken by the wearer. Her countenance betokened self-possession, and as she sat her fingers played furtively with the haft of a good sized knife.

The coterie leaving a large kettle hanging upon the cross-sticks over a fire, in which to cook a fat dog for a feast at the close of the ceremony, soon set off, in single file procession, to visit the camp of the respective chiefs, who remained at their lodges to receive these guests. In the march, our heroine was the third, two leading braves before her. No timid air and bearing were apparent upon the person of this wild-wood nymph; her step was proud and majestic, as that of a Forest Queen should be.

The party visited the various chiefs, each of whom, or his proxy, appeared and gave a harangue, the tenor of which, we learned, was to minister to their war spirit, to herald the glory of their tribe, and to exhort the practice of charity and good will to their poor. At the close of each speech, some donation to the beggar’s fun, blankets, provisions, &c., was made from the lodge of each visited chief. Some of the latter danced and sung around the ring, brandishing the war-club in the air and over his head. Chief “LOON’S FOOT,” whose lodge was near the Indian Agents residence, (the latter chief is the brother of Mrs. Judge ASHMAN at the Soo,) made a lengthy talk and gave freely…

…An evening’s interview, through an interpreter, with the chief, father of the Princess, disclosed that a small party of Sioux, at a time not far back, stole near unto the lodge of the the chief, who was lying upon his back inside, and fired a rifle at him; the ball grazed his nose near his eyes, the scar remaining to be seen–when the girl seizing the loaded rifle of her father, and with a few young braces near by, pursued the enemy; two were killed, the heroine shot one, and bore his scalp back to the lodge of NA-NAW-ONG-GA-BE, her father.

At this interview, we learned of a custom among the Chippewas, savoring of superstition, and which they say has ever been observed in their tribe. All the youths of either sex, before they can be considered men and women, are required to undergo a season of rigid fasting. If any fail to endure for four days without food or drink, they cannot be respected in the tribe, but if they can continue to fast through ten days it is sufficient, and all in any case required. They have then perfected their high position in life.

This Princess fasted ten days without a particle of food or drink; on the tenth day, feeble and nervous from fasting, she had a remarkable vision which she revealed to her friends. She dreamed that at a time not far distant, she accompanied a war party to the Sioux country, and the party would kill one of the enemy, and would bring home his scalp. The war party, as she had dreamed, was duly organized for the start.

Against the strongest remonstrance of her mother, father, and other friends, who protested against it, the young girl insisted upon going with the party; her highest ambition, her whole destiny, her life seemed to be at stake, to go and verify the prophecy of her dream. She did go with the war party. They were absent about ten or twelve days, the had crossed the Mississippi, and been into the Sioux territory. There had been no blood of the enemy to allay their thirst or to palliate their vengeance. They had taken no scalp to herald their triumphant return to their home. The party reached the great river homeward, were recrossing, when lo! they spied a single Sioux, in his bark canoe near by, whom they shot, and hastened exultingly to bear his scalp to their friends at the lodges from which they started. Thus was the prophecy of the prophetess realized to the letter, and herself, in the esteem of all the neighboring bands, elevated to the highest honor in all their ceremonies. They even hold her in superstitious reverence. She alone, of the females, is permitted in all festivities, to associate, mingle and to counsel with the bravest of the braves of her tribe…”

Benjamin Armstrong

Benjamin ArmstrongBenjamin Armstrong’s memoir Early Life Among the Indians also includes an account of the warrior daughter of Nenaa’angebi. In contrast to Morse, the outside observer, Armstrong was married to Buffalo’s niece and was the old chief’s personal interpreter. He lived in this area for over fifty years and knew just about everyone. His memoir, published over 35 years after Hanging Cloud got her fame, contains details an outsider wouldn’t have any way of knowing.

Unfortunately, the details don’t line up very well. Most conspicuously, Armstrong says that Nenaa’angebi was killed in the attack that brought his daughter fame. If that’s true, then I don’t know how Morse was able to record the Rice Lake chief’s speeches the following summer. It’s possible these were separate incidents, but it is more likely that Armstrong’s memories were scrambled. He warns us as much in his introduction. Some historians refuse to use Armstrong at all because of discrepancies like this and because it contains a good deal of fiction. I have a hard time throwing out Armstrong completely because he really does have the insider’s knowledge that is lacking in so many primary sources about this area. I don’t look at him as a liar or fraud, but rather as a typical northwoodsman who knows how to run a line of B.S. when he needs to liven up a story. Take what you will of it, these are pages 199-202 of Early Life Among the Indians.

“While writing about chiefs and their character it may not be amiss to give the reader a short story of a chief‟s daughter in battle, where she proved as good a warrior as many of the sterner sex.

In the ’50’s there lived in the vicinity of Rice Lake, Wis. a band of Indians numbering about 200. They were headed by a chief named Na-nong-ga-bee. This chief, with about seventy of his people came to La Point to attend the treaty of 1854. After the treaty was concluded he started home with his people, the route being through heavy forests and the trail one which was little used. When they had reached a spot a few miles south of the Namekagon River and near a place called Beck-qua-ah-wong they were surprised by a band of Sioux who were on the warpath and then in ambush, where a few Chippewas were killed, including the old chief and his oldest son, the trail being a narrow one only one could pass at a time, true Indian file. This made their line quite long as they were not trying to keep bunched, not expecting or having any thought of being attacked by their life long enemy.

The chief, his son and daughter were in the lead and the old man and his son were the first to fall, as the Sioux had of course picked them out for slaughter and they were killed before they dropped their packs or were ready for war. The old chief had just brought the gun to his face to shoot when a ball struck him square in the forehead. As he fell, his daughter fell beside him and feigned death. At the firing Na-nong-ga-bee’s Band swung out of the trail to strike the flanks of the Sioux and get behind them to cut off their retreat, should they press forward or make a retreat, but that was not the Sioux intention. There was not a great number of them and their tactic was to surprise the band, get as many scalps as they could and get out of the way, knowing that it would be but the work of a few moments, when they would be encircled by the Chippewas. The girl lay motionless until she perceived that the Sioux would not come down on them en-masse, when she raised her father‟s loaded gun and killed a warrior who was running to get her father‟s scalp, thus knowing she had killed the slayer of her father, as no Indian would come for a scalp he had not earned himself. The Sioux were now on the retreat and their flank and rear were being threatened, the girl picked up her father‟s ammunition pouch, loaded the rifle, and started in pursuit. Stopping at the body of her dead Sioux she lifted the scalp and tucked it under her belt. She continued the chase with the men of her band, and it was two days before they returned to the women and children, whom they had left on the trail, and when the brave little heroine returned she had added two scalps to the one she started with.

She is now living, or was, but a few years ago, near Rice Lake, Wis., the wife of Edward Dingley, who served in the war of rebellion from the time of the first draft of soldiers to the end of the war. She became his wife in 1857, and lived with him until he went into the service, and at this time had one child, a boy. A short time after he went to the war news came that all the party that had left Bayfield at the time he did as substitutes had been killed in battle, and a year or so after, his wife, hearing nothing from him, and believing him dead, married again. At the end of the war Dingley came back and I saw him at Bayfield and told him everyone had supposed him dead and that his wife had married another man. He was very sorry to hear this news and said he would go and see her, and if she preferred the second man she could stay with him, but that he should take the boy. A few years ago I had occasion to stop over night with them. And had a long talk over the two marriages. She told me the circumstances that had let her to the second marriage. She thought Dingley dead, and her father and brother being dead, she had no one to look after her support, or otherwise she would not have done so. She related the related the pursuit of the Sioux at the time of her father‟s death with much tribal pride, and the satisfaction she felt at revenging herself upon the murder of her father and kinsmen. She gave me the particulars of getting the last two scalps that she secured in the eventful chase. The first she raised only a short distance from her place of starting; a warrior she espied skulking behind a tree presumably watching for some one other of her friends that was approaching. The other she did not get until the second day out when she discovered a Sioux crossing a river. She said: “The good luck that had followed me since I raised my father‟s rifle did not now desert me,” for her shot had proved a good one and she soon had his dripping scalp at her belt although she had to wade the river after it.”

At this point, this is all I have to offer on the story of Hanging Cloud the ogichidaakwe. I’ll be sure to update if I stumble across anything else, but for now, we’ll have to be content with these two contradictory stories.