Wisconsin Territory Delegation: Copper Harbor

April 11, 2016

By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from Mackinac and Sault Ste Marie.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

July 22, 1845.

TERRITORY OF WISCONSIN.

“The Wisconsin Territorial Seal was designed in 1836 by John S. Horner, the first secretary of the territory, in consultation with Henry Dodge, the first territorial governor. It features an arm holding a pick and a pile of lead ore.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Gen. Henry Dodge, having been re-appointed Governor of the Territory, from which he had been “so ingloriously ejected after the election of 1840, by his political opponents, his valuable services” have ceased as a member of Congress. It became necessary, of course, to elect another delegate. To choose a candidate for this office, a democratic convention was held at the capitol, in Madison, on the 25th June. Horatio N. Wells, of Milwaukie, was elected president; 18 ballots were taken before any one obtained a majority of the votes. Mr. Morgan L. Martin finally received 49, D. A. J. Upham 20, scattering 10. Mr. Martin accepts the nomination.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

July 29, 1845.

[From our regular correspondent.]

COPPER HARBOR, LAKE SUPERIOR,

JULY 15, 1845.

“Ojibwa village near Sault Ste Marie” by Paul Kane in 1845.

~ Wikipedia.org

Having chartered a Mackinac boat at the Sault St. Marie, and stored away our luggage, tents, provisions, with general camp equipage, &c., taking on board six able-bodied voyageurs, consisting of four descendants of Canadian French, and two half-breed Indians, (one of whom acted as our pilot,) we set off, on the 4th of July, at about 11, a.m., to coast it up the southern shore of Lake Superior, to Copper Harbor – a distance, by the way we were to travel, of over 280 miles.

The heat of the sun, combined with the attacks of musquitoes at night, annoyed us very much at first. I have seen what musquitoes are in many other parts of the world; but I never found them more abundant and troublesome than at some points on Lake Superior.

It took us eleven days’ voyaging to reach this place, travelling all day when the weather was favorable, and lying by when it became stormy, with strong head winds. At night we camped on shore, and generally rose every morning between three and four o’clock, being under way on the water as soon as it was light enough to see. In voyaging in this way, we had a better opportunity to view the country as we passed along, many portions of which were full of interest – such as the Grand Sable, the Pictured Rocks, &c. The former are immense cliffs, rising to the height of two hundred feet above the level of the lake, being composed of pure sand, and reaching about six miles in length along the lake shore, with its front aspects almost perpendicular. It is said, the sand of which they are formed maintains its perpendicularity by reason of the moisture which it derives from the vapor of the lake. The summits contain no vegetation, save here and there a solitary shrub or bush. The rest of this high, bold, and solemn mass stretches out, in silent and naked grandeur, beneath the horizon, forming a picture of desolate sublimity. We passed it late in the afternoon, during a bright and clear sky, when the sun had just begun to hide himself behind its huge masses.

“Once a vessel was sailing over a northern ocean in the midst of the short, Arctic summer. The sun was hot, the air was still, and a group of sailors lying lazily upon the deck were almost asleep, when an exclamation of fear from one of them made them all spring to their feet. The one who had uttered the cry pointed into the air at a little distance, and there the awe-stricken sailors saw a large ship, with all sails set, gliding over what seemed to be a placid ocean, for beneath the ship was the reflection of it.”

~ Round-about Rambles in Lands of Fact and Fancy, by Frank Richard Stockton, 1910, page 277.

I have never travelled on a sheet of water where the effect of mirage is so frequently witnessed as on Lake Superior. For instance: early on Sunday morning, the 6th of July, soon after leaving our encampment, near White Fish Point, the morning being slightly foggy, we saw distinctly the Grand Sable, which must have been fifty miles in advance of us, with intervening points of land. I witnessed a similar instance of mirage when coming through Lake Huron. Early one morning, I distinctly saw Drummond’s island, which the officers of the boat assured me was eighty miles off!

I have never seen an atmosphere through which I could discern objects so far as on Lake Superior. Cliffs, headlands, islands, and hills, which often appeared as if within a mile or two of us, were found, on being approached, to be from five to ten miles off. Hence, in making what “voyageurs” called “traverses” – that is, a passage in a direct line from one headland to another, instead of curving with the shore of the lake – inexperienced voyageurs are very liable to be deceived, by supposing the distance to be short, when it is in reality very long. In making which, should a strong wind spring up from shore, a small boat would be liable to be blown out to sea, and the boat and people run the hazard of being lost. We had some brief but painful experience of this deception in apparent distance, by attempting one morning, after having camped at the mouth of the Dead river, to sail before what seemed to be a fair wind from Presqu’isle to Granite Point; but we had not made much over half the distance, when the wind suddenly changed to the west, and blew a gale on our beam, and we came very near being blown out into the open lake – which is just about equivalent to being blown into the Atlantic, for the storms are just as strong, and the waves roll equally as high. Finding we were going to leeward, we dropped sail, and took to our oars; and, although within half a mile of the point we wished to make, it took us hard oaring for about an hour to reach it.

“Pictured Rocks Splash © Lou Waldock”

~ National Park Service

I have never seen a sheet of water, where the wind can succeed in so suddenly throwing the water into turbulent waves, as on Lake Superior. This is owing to its freshness, making it so much lighter than salt water. One night, just as we had oared past a perpendicular red sandstone cliff a mile or two in length, where it would have been impossible for us to make a landing, and had reached a sand beach at the mouth of a small river, where we camped, the surface of the lake up to that time being as smooth as glass, we had no sooner pitched our tents, than a violent wind sprang up from the northeast, and blew a gale nearly all night, shifting from one point to another. In fifteen or twenty minutes after the commencement of the blow, the water of the lake seemed lashed into a fury of commotion, in which our boat could scarcely have survived.

The grandest scenery beheld in the whole route was that presented by the celebrated “Pictured Rocks.” They lie stretched out for nine miles in length, a little east of Grand island. They are considered very dangerous to pass by voyageurs, who generally select favorable spells of weather for the trip.

“Grand Sable Dunes”

~ National Park Service

On the morning of Tuesday, the 8th instant, soon after leaving our camp, the fog cleared up, sufficient to give us a glimpse of these stupendous sandstone cliffs. As the sun rose, the fog became dispersed, and its brilliant beams fell upon and illuminated every portion of them.

They rise in perpendicular walls from the water of the lake shore, to the height of from 200 to 300 feet. They are so precipitous, that they in some places appear to lean over the lake at top, to which small trees are seen leaning over the lake, hanging by their frail roots to the giddy crags above. At one point, a small creek tumbles over a portion of them in a cascade of 100 feet in height. They stretch for nine miles in length, and in all that distance there are only two places where boats can land – one cove being called the Chapel, and the second Miner’s river.

Photograph of “Chapel Rock” by David Kronk.

~ National Park Service

“Bridalveil Falls”

~ National Park Service

So deep is the water, that a boat can pass close along shore, almost touching the cliffs. Indeed, a seventy-four-gun ship can ride with perfect safety within ten feet of their base. Taken altogether, their solemn grandeur, and the awful sublimity of their gigantic forms and elevation, far surpass anything of the kind, probably, on the continent, if not in the world. Next to the Falls of Niagara, they are the greatest natural curiosity they eyes of man can behold. When steamboats are introduced on Lake Superior, they cannot fail to attract the attention of the tourist. They contain vast caves, one of which is only 30 feet wide at its mouth, but, on entering it, suddenly expands to 200 feet in width, beneath a lofty dome of 200 feet high. Different portions of the cliffs go by different names – such as the “Portailles,” the “Doric Rock,” the “Gros Cap,” the “Chapel,” &c. We went into a small bay at the base of the “Chapel,” which consists of an immense mass of rude sandstone, with trees growing on it, expanded in the form of an arch, its extremities resting on irregularly shaped columns, to the number of three or four under each end. Beneath the arch, a deep gorge enters the lake, crowded and choked with luxuriant vegetation. It appeared to me like the finest and most natural Druidical altar to be seen anywhere, not excepting even Stonehenge. Near the Chapel, a brisk little stream falls rapidly over the rocks into the water below. It is impossible to do justice to the splendid appearance of “the Pictured Rocks,” so called on account of the [???? ????? ???????] composed being mixed with iron ore, drippings from which they have stained the surface of the rocks with a variety of tints. The painter alone can convey any just image to the mind’s eye of these grand cliffs, and they will afford him a hundred views, every one of which will differ from the other. I will defy anybody to visit them, as we did, on a clear, bright day, when the lake is smooth, in an open boat, close by the side of them, without having his expectations of their natural grandeur far surpassed.

“Preliminary Chart of Grand Island and Its Approaches, Lake Superior, 1859″

~ Maritime History of the Great Lakes

Boats have sometimes been caught in the Chapel by sudden, high, and contrary winds, and compelled to remain there for three or four days, before being able to proceed. A few miles beyond the “Pictured Rocks,” we came to Grand Island, where, entering its harbor, we stopped at Mrs. Williams’s place, the only settlement on the island, which is very large. This is one of the most splendid and safe harbors on Lake Superior – perfectly land-locked on every side, and extensive enough to contain a large fleet of vessels, being easy of ingress or egress. From Grand Island we continued to persevere in our voyage, and finally reached Copper Harbor, via the Anse, in eleven days from the Sault Ste. Marie.

“The beginning of Methodism in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan west of Sault Ste. Marie is credited to the missionary trail blazers who came to Kewawenon, now known as Keweenaw Bay. The first, in 1832 with John Sunday a converted Canadian Indian. In 1833 Rev. John Clark continued the mission work started by Sunday. He was followed by Rev. Daniel Chandler in 1834 who remained here for two years. Rev. Clark was appointed Superintendent of Lake Superior Missions in 1834 and was instrumental in having a mission house and church school house erected during Rev. Chandler’s mission stay. Houses for the local natives were also erected along the lake shore in the vicinity of the present Whirl-I-Gig Road”

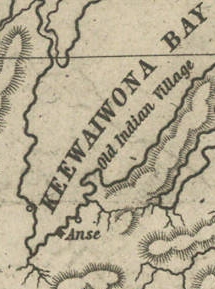

At the Anse we fell in with Mr. Ord, the United States Indian agent at the Sault Ste. Marie, who was on a visit to the Indians at that point, to take the census, and to hold a talk with their chiefs in council. We arrived at the Anse a few hours before the council began. The chiefs all sat around a hall on wooden benches, while Mr. Ord, with the interpreter, was seated at the head of the circle. Many of the Indians were fine-looking men. They had a great many petty grievances to relate to the agent, who listened to them with patient attention. The Chippewas about the Anse are said to be much better off than those who trade to La Pointe, at the upper end of the lake.

The Methodists have a missionary station and school on the east side of the bay of Keweewena, and near its head; around which there is an Indian village, consisting of 600 or 700 souls. The Catholics have also a missionary station on the opposite side of the bay, which is here only about a mile or two wide.

Reverend William Hadley Brockway: “The first Methodist minister licensed to preach in the State of Michigan.”

~ Geni.com

The government employs at this Indian post one blacksmith, (Mr. Brockaway,) one carpenter, (Mr. Johnson,) and one teacher, in the person of the Methodist minister. We left the Anse about half-past 4 o’clock, p.m., sailing before a fair wind, reaching the mouth of the Portage, or Sturgeon river, where we camped on a flat point of land severely infested by musquitoes, with the heat equal to any in intensity (which had prevailed during the day) that I ever experienced. At Fort Wilkins, Copper Harbor, on the same day, I have since learned the mercury rose to 100° in the shade. This would seem to be a tremendous degree of heat for such a high latitude, the fort standing on the parallel of 47° 30′.

Detail of “Keewaiwona Bay” with “Anse” and the “Old Indian Village” from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

During the night, we could occasionally hear the plunges of sturgeon floundering in the water, which abound in this lake river. A thunder-storm, also, passed near, before day, which had the effect to cool the air. About half-past 1 o’clock, I was awakened by the loud talk and whooping of Indians, carried on between our Indian half-breed pilot, Jean Baptiste, and a lot of freshly-arrived Indian voyageurs, conducted in the Indian dialect. On looking out of our tent, I discovered a plain-dressed Yankee-looking man, standing in front of it. On hailing him, he proved to be the Rev. Mr. Brockaway, a Methodist minister, and superintendent of Indian missions in this part of the world. He had been on a visit to the missions at the upper end of the lake, and was returning to the Anse, which he was anxious to reach in time to attend to Sunday morning service, (the next day being Sunday,) and from whence he expected to proceed to the Sault Ste. Marie, where he is stationed in the capacity of chaplain to the garrison at that post. He said he had, on reaching our encampment, travelled that day from the Ontonagon river, 80 miles distance, in a bark canoe, accompanied by four Indian voyageurs. After the Indians had prepared some food, with tea, of which Mr. B. and themselves partook, they again set off for the Anse, about 15 miles from us, where they must have arrived at a very early hour. This despatch far exceeded the expedition of our movements, and displayed unusual activity on the part of the enterprising missionary of an extensive and practical church organization.

We rose at three a.m., and in half an hour were under way on the lake. In these latitudes it is light at three in the morning; twilight continuing till eight and nine in the afternoon.

The following night we camped near the mouth of Little Montreal river, in full view of the high mountains or large round hills of trap rocks running along the peninsula of Keweewena towards its extreme point, some of which rise to the elevation of eight hundred feet above the level of the lake.

The next day, after some detention, we reached Copper Harbor, and landed near the United States Mineral Agency on Porter’s island, where we found quite a village, consisting of white canvas tents of various sizes and forms, occupied by miners, geologists, speculators, voyageurs, visitors, &c.

The only tenement on the island is a miserable log-cabin, in which General Stockton, for the want of better quarters, is compelled to keep his office. The room which he occupies, is only about eight feet square – just large enough to admit a narrow bed for himself, a table, and two or three chairs. In this salt-box of a room, he is compelled to transact all the business relating to the mineral lands embraced within this important agency. As many as a dozen men at a time are pressing forward to his “bee gum” apartment, endeavoring to have their business transacted.

The office of the surveyor of this mineral lands, in charge of Mr. Gray, at this agency, is still worse adapted to the transaction of public business. He is compelled to occupy the garret of the log-cabin, with a hole cut through the logs in the gable to serve as a window. In this garret he is obliged to have all his draughting performed, subject to the constant interruption of parties wishing to see plans of the mineral lands. It would seem almost impossible, under such circumstances, for the officers to avoid making mistakes; yet, by dint of unwearied labor and attention to their official duties, they have conducted their affairs with an accuracy and despatch highly creditable to them.

The government has been fortunate in the selection of its agents in the mineral region of Lake Superior. To untiring industry, punctuality, and close attention to business, they unite, in a high degree, the bland, mild, and patient bearing of gentlemen.

Gen. Stockton’s labor are severe and perplexing. He is continually beset by crowds of applicants for locations, all anxiously pressing forward to secure leases for copper-mines – among whom are found some utterly reckless of all principles of justice and equity, who endeavor to bend the agent into a compliance with their unjust and unreasonable demands – such as wishing him to supersede prior locations for their benefit, or to grant locations evidently intended to cover town sites, beyond the bounds of his agency, where no mineral exists, which he has no authority to grant; and because he has, in every instance of the kind, resisted their unreasonable applications, he has not escaped making a few enemies among such persons, who are collecting together to abuse and misrepresent him. Considering the cramped quarters furnished him by the government, and the great rush of people upon him from all quarters, under the excitement of a copper fever raging at its height, and many anxious to obtain exclusive advantages, it is surprising how he has succeeded so well as he has done in giving such general satisfaction. His official duties are discharged with a promptitude, fidelity, firmness, and impartiality, which are creditable to the public service. He seems peculiarly fitted, both by habit and nature, for the discharge of the responsible duties involved in the administration of an agency established in a wild an uninhabited country, being traversed at present by bands of people in search of mineral treasures, as diversified in character, dispositions, &c., as the various sections of country from whence they come – many of whom are by no means scrupulous as to the means for promoting their own interest – who probably suppose they can play the same game in the copper mineral region that was practiced in the early leasing of the lead mineral districts of Illinois: that is, seize upon government lands, work and raise mineral ore, cheat the government, and sell rights, where they have never had a claim.

It is enough to say that, while such men as Gen. Stockton, Major Campbell, and Mr. Gray, remain in office on the southern shore of Lake Superior, all such desperadoes will be completely foiled and disappointed. The frauds committed on the government in the working of the lead-mines, cannot be repeated in the copper mineral region of the United States. When fraudulently-inclined adventurers find they cannot make the faithful officers of government stationed in this quarter swerve from the strict and impartial discharge of their duty, they will probably unite for the purpose of operating upon government to procure their removal, and endeavor to get men in their places more likely to act as plaint tools in promoting their selfish ends.

Detail of Porter’s Island, Fort Wilkins, Copper Harbor, Agate Harbor, Eagle Harbor, and Little Montreal River along the tip of the Keweenaw Peninsula from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The agency being on a narrow small island, half a mile from the mainland, makes it very inconvenient. The island does not afford sufficient timber for fire-wood, and in winter is isolated by ice, &c. It should by all means be removed to the main shore, and placed near Fort Wilkins, which is nearly two miles distant on the main land, or removed up to Eagle Harbor, which is a far preferable and more convenient site for the agency.

There is no question by the great range of trap-rock, running parallel with the southern shore of Lake Superior for a great distance, is [????????] with many valuable veins of copper ore; but to find them and develop them, must be the work of time. The impenetrable stunted forest seems to be little else than a thick, universal hedge, formed by the horizontal interlocked limbs of dwarf white cedars, intermingled with tamarack, birch, and maple. Persons who attempt to penetrate through them, without being protected by a mail of dressed buck-skin, have their clothes soon slit and torn from their bodies in shreds.

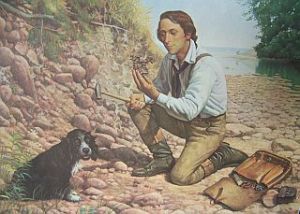

Painting of Professor Douglass Houghton by Robert Thom. Houghton first explored the south shore of Lake Superior in 1840, and died on Lake Superior during a storm on October 13, 1845. Chequamegon Bay’s City of Houghton was named in his honor, and is now known as Houghton Falls State Natural Area.

Dr. Houghton says, so considerable is the attraction of the trap-rock for the needle, that, on many places, when surveying over its ranges, he cannot rely upon it, and is compelled to run his lines by the sun and stellar observations.

So far as practicable mining operations have progressed in the country, the following seems to be the result:

At Eagle river several locations are being worked, superintended by Col. Gratiot, and on which from 70 to 80 men are employed.

At Agate Harbor another company have this season commenced operations under the direction of Mr. Larned, of New York, in whose service from 15 to 20 laborers find employment.

At Copper Harbor a company from Pittsburg are working a vein of black oxide of copper, under the superintendence of Dr. Pettit, who has from 30 to 40 hands employed under him. Besides these, there are other small parties at work in various directions. So that it would appear that mining in the United States copper mineral lands has fairly commenced.

Up to this time, the returns made to the agency by two of the above companies – the Eagle River, alias Boston Company, and the Pittsburg Company – amount to the following quantities of ore: The former have raised 500,000 lbs. of ore, worth not less than $125 per ton. The latter company have raised 6,670 lbs. of the black oxide copper ore, the value of which I do not exactly know.

Other companies are organizing for mining purposes, and will probably commence operations the present, or early in the next season.

The country still in the possession of the Chippewa Indians, embraced between the northwestern part of the lake and the British frontier, along Pigeon river, might be easily obtained from them by treaty. And, if poor in mineral wealth, it is a very rich soil and a good agricultural country; and by its acquisition we should at once extend and square out our possession and settlements to the British frontier, which should be protected by detached forts, extending along our lines, towards the Lake of the Woods. According to the present Indian boundary, it is made to pass along the water-line of the lake shore, from Pigeon river, around Fond du Lac; and when some distance east and south of the lake, strikes a straight line west from the Mississippi. The United States, by being cut off by this water-line from all landing sites for harbors or fortifications for one or two hundred miles of the western and northern shore of the lake, will be subject to great inconvenience.

The number of persons at present exploring or visiting the mineral region of Lake Superior, is supposed to amount to five hundred or more. The water of the lake, especially in deep places is remarkably fine and cool for drinking. The surface of the water in the upper part of the lake is said to be 900 feet above the level of the Atlantic. The shores of this great lake are, at many places, bold, high, grand, and solitary – the favorite resort of large eagles, several of which we saw – one, in particular, was a splendid specimen of the bald eagle. The lake abounds in white fish, trout, siskomit, and bass.

The Siscowet, or Fat Trout, is a subspecies of Lake Trout. Drawn by David Starr Jordan, and Barton Warren Evermann, 1911.

~ University of Washington

We caught fine trout almost every day during our voyage, by trailing a hook and line at the end of our boat. On the 13th inst., (the day before reaching Copper Harbor) we caught four fine large trout.

The scenery, climate, &c., of Lake Superior, strike the traveller as being peculiar, and something very different from what is met with in any part of the United States. Game is not abundant. With the exception of a porcupine, and a squirrel or two, we succeeded in killing nothing. Wild fowl, pigeon, and ducks are more plentiful. we killed many of the former, and two pheasants, during our trip. Our half-breed Indians skinned and dressed our porcupine for us, whose flesh we found quite palatable.

At one point I purchased the hind-quarters of a beaver, which some Indians had killed. The tail being considered a great delicacy, I sent it to Mr. Ord and party, who were then travelling in a separate boat, in company with us. We found the beaver meat, when dressed, most delicious food.

Our party, although sleeping in and exposed to showers for a day or two, all enjoyed excellent health. Many voyageurs are attacked with dysentery, but it is very slight, and easily overcome by the use of simple medicine.

I remain yours,

Very truly and respectfully,

MORGAN.

To be continued in The Copper Region…

Perrault, Curot, Nelson, and Malhoit

March 8, 2014

I’ve been getting lazy, lately, writing all my posts about the 1850s and later. It’s easy to find sources about that because they are everywhere, and many are being digitized in an archival format. It takes more work to write a relevant post about the earlier eras of Chequamegon History. The sources are sparse, scattered, and the ones that are digitized or published have largely been picked over and examined by other researchers. However, that’s no excuse. Those earlier periods are certainly as interesting as the mid-19th Century. I needed to just jump in and do a project of some sort.

I’m someone who needs to know the names and personalities involved to truly wrap my head around a history. I’ve never been comfortable making inferences and generalizations unless I have a good grasp of the specific. This doesn’t become easy in the Lake Superior country until after the Cass Expedition in 1820.

But what about a generation earlier?

The dawn of the 19th-century was a dynamic time for our region. The fur trade was booming under the British North West Company. The Ojibwe were expanding in all directions, especially to west, and many of familiar French surnames that are so common in the area arrived with Canadian and Ojibwe mix-blooded voyageurs. Admittedly, the pages of the written record around 1800 are filled with violence and alcohol, but that shouldn’t make one lose track of the big picture. Right or wrong, sustainable or not, this was a time of prosperity for many. I say this from having read numerous later nostalgic accounts from old chiefs and voyageurs about this golden age.

We can meet some of the bigger characters of this era in the pages of William W. Warren and Henry Schoolcraft. In them, men like Mamaangazide (Mamongazida “Big Feet”) and Michel Cadotte of La Pointe, Beyazhig (Pay-a-jick “Lone Man) of St. Croix, and Giishkiman (Keeshkemun “Sharpened Stone”) of Lac du Flambeau become titans, covered with glory in trade, war, and influence. However, there are issues with these accounts. These two authors, and their informants, are prone toward glorifying their own family members. Considering that Schoolcraft’s (his mother-in law, Ozhaawashkodewike) and Warren’s (Flat Mouth, Buffalo, Madeline and Michel Cadotte Jr., Jean Baptiste Corbin, etc.) informants were alive and well into adulthood by 1800, we need to keep things in perspective.

The nature of Ojibwe leadership wasn’t different enough in that earlier era to allow for a leader with any more coercive power than that of the chiefs in 1850s. Mamaangazide and his son Waabojiig may have racked up great stories and prestige in hunting and war, but their stature didn’t get them rich, didn’t get them out of performing the same seasonal labors as the other men in the band, and didn’t guarantee any sort of power for their descendants. In the pages of contemporary sources, the titans of Warren and Schoolcraft are men.

Finally, it should be stated that 1800 is comparatively recent. Reading the journals and narratives of the Old North West Company can make one feel completely separate from the American colonization of the Chequamegon Region in the 1840s and ’50s. However, they were written at a time when the Americans had already claimed this area for over a decade. In fact, the long knife Zebulon Pike reached Leech Lake only a year after Francois Malhoit traded at Lac du Flambeau.

The Project

I decided that if I wanted to get serious about learning about this era, I had to know who the individuals were. The most accessible place to start would be four published fur-trade journals and narratives: those of Jean Baptiste Perrault (1790s), George Nelson (1802-1804), Michel Curot (1803-1804), and Francois Malhoit (1804-1805).

The reason these journals overlap in time is that these years were the fiercest for competition between the North West Company and the upstart XY Company of Sir Alexander MacKenzie. Both the NWC traders (such as Perrault and Malhoit) and the XY traders (Nelson and Curot) were expected to keep meticulous records during these years.

I’d looked at some of these journals before and found them to be fairly dry and lacking in big-picture narrative history. They mostly just chronicle the daily transactions of the fur posts. However, they do frequently mention individual Ojibwe people by name, something that can be lacking in other primary records. My hope was that these names could be connected to bands and villages and then be cross-referenced with Warren and Schoolcraft to fill in some of the bigger story. As the project took shape, it took the form of a map with lots of names on it. I recorded every Ojibwe person by name and located them in the locations where they met the traders, unless they are mentioned specifically as being from a particular village other than where they were trading.

I started with Perrault’s Narrative and tried to record all the names the traders and voyageurs mentioned as well. As they were mobile and much less identified with particular villages, I decided this wasn’t worth it. However, because this is Chequamegon History, I thought I should at least record those “Frenchmen” (in quotes because they were British subjects, some were English speakers, and some were mix-bloods who spoke Ojibwe as a first language) who left their names in our part of the world. So, you’ll see Cadotte, Charette, Corbin, Roy, Dufault (DeFoe), Gauthier (Gokee), Belanger, Godin (Gordon), Connor, Bazinet (Basina), Soulierre, and other familiar names where they were encountered in the journals. I haven’t tried to establish a complete genealogy for either, but I believe Perrault (Pero) and Malhoit (Mayotte) also have names that are still with us.

For each of the names on the map, I recorded the narrative or journal they appeared in:

JBP= Jean Baptiste Perrault

GN= George Nelson

MC= Michel Curot

FM= Francois Malhoit

Red Lake-Pembina area: By this time, the Ojibwe had started to spread far beyond the Lake Superior forests and into the western prairies. Perrault speaks of the Pillagers (Leech Lake Band) being absent from their villages because they had gone to hunt buffalo in the west. Vincent Roy Sr. and his sons later settled at La Pointe, but their family maintained connections in the Canadian borderlands. Jean Baptiste Cadotte Jr. was the brother of Michel Cadotte (Gichi-Mishen), the famous La Pointe trader.

Leech Lake and Sandy Lake area: The names that jump out at me here are La Brechet or Gaa-dawaabide (Broken Tooth), the great Loon-clan chief from Sandy Lake (son of Bayaaswaa mentioned in this post) and Loon’s Foot (Maangozid). The Maangozid we know as the old speaker and medicine man from Fond du Lac (read this post) was the son of Gaa-dawaabide. He would have been a teenager or young man at the time Perrault passed through Sandy Lake.

Fond du Lac and St. Croix: Augustin Belanger and Francois Godin had descendants that settled at La Pointe and Red Cliff. Jean Baptiste Roy was the father of Vincent Roy Sr. I don’t know anything about Big Marten and Little Marten of Fond du Lac or Little Wolf of the St. Croix portage, but William Warren writes extensively about the importance of the Marten Clan and Wolf Clan in those respective bands. Bayezhig (Pay-a-jick) is a celebrated warrior in Warren and Giishkiman (Kishkemun) is credited by Warren with founding the Lac du Flambeau village. Buffalo of the St. Croix lived into the 1840s. I wrote about his trip to Washington in this post.

Lac Courte Oreilles and Chippewa River: Many of the men mentioned at LCO by Perrault are found in Warren. Little (Petit) Michel Cadotte was a cousin of the La Pointe trader, Big (Gichi/La Grande) Michel Cadotte. The “Red Devil” appears in Schoolcraft’s account of 1831. The old, respected Lac du Flambeau chief Giishkiman appears in several villages in these journals. As the father of Keenestinoquay and father-in-law of Simon Charette, a fur-trade power couple, he traded with Curot and Nelson who worked with Charette in the XY Company.

La Pointe: Unfortunately, none of the traders spent much time at La Pointe, but they all mention Michel Cadotte as being there. The family of Gros Pied (Mamaangizide, “Big Feet”) the father of Waabojiig, opened up his lodge to Perrault when the trader was waylaid by weather. According to Schoolcraft and Warren, the old war chief had fought for the French on the Plains of Abraham in 1759.

Lac du Flambeau: Malhoit records many of the same names in Lac du Flambeau that Nelson met on the Chippewa River. Simon Charette claimed much of the trade in this area. Mozobodo and “Magpie” (White Crow), were his brothers-in-law. Since I’ve written so much about chiefs named Buffalo, I should point out that there’s an outside chance Le Taureau (presumably another Bizhiki) could be the famous Chief Buffalo of La Pointe.

L’Anse, Ontonagon, and Lac Vieux Desert: More Cadottes and Roys, but otherwise I don’t know much about these men.

At Mackinac and the Soo, Perrault encountered a number of names that either came from “The West,” or would find their way there in later years. “Cadotte” is probably Jean Baptiste Sr., the father of “Great” Michel Cadotte of La Pointe.

Malhoit meets Jean Baptiste Corbin at Kaministiquia. Corbin worked for Michel Cadotte and traded at Lac Courte Oreilles for decades. He was likely picking up supplies for a return to Wisconsin. Kaministiquia was the new headquarters of the North West Company which could no longer base itself south of the American line at Grand Portage.

Initial Conclusions

There are many stories that can be told from the people listed in these maps. They will have to wait for future posts, because this one only has space to introduce the project. However, there are two important concepts that need to be mentioned. Neither are new, but both are critical to understanding these maps:

1) There is a great potential for misidentifying people.

Any reading of the fur-trade accounts and attempts to connect names across sources needs to consider the following:

- English names are coming to us from Ojibwe through French. Names are mistranslated or shortened.

- Ojibwe names are rendered in French orthography, and are not always transliterated correctly.

- Many Ojibwe people had more than one name, had nicknames, or were referenced by their father’s names or clan names rather than their individual names.

- Traders often nicknamed Ojibwe people with French phrases that did not relate to their Ojibwe names.

- Both Ojibwe and French names were repeated through the generations. One should not assume a name is always unique to a particular individual.

So, if you see a name you recognize, be careful to verify it’s reall the person you’re thinking of. Likewise, if you don’t see a name you’d expect to, don’t assume it isn’t there.

2) When talking about Ojibwe bands, kinship is more important than physical location.

In the later 1800s, we are used to talking about distinct entities called the “St. Croix Band” or “Lac du Flambeau Band.” This is a function of the treaties and reservations. In 1800, those categories are largely meaningless. A band is group made up of a few interconnected families identified in the sources by the names of their chiefs: La Grand Razeur’s village, Kishkimun’s Band, etc. People and bands move across large areas and have kinship ties that may bind them more closely to a band hundreds of miles away than to the one in the next lake over.

I mapped here by physical geography related to trading posts, so the names tend to group up. However, don’t assume two people are necessarily connected because they’re in the same spot on the map.

On a related note, proximity between villages should always be measured in river miles rather than actual miles.

Going Forward

I have some projects that could spin out of these maps, but for now, I’m going to set them aside. Please let me know if you see anything here that you think is worth further investigation.

Sources:

Curot, Michel. A Wisconsin Fur Trader’s Journal, 1803-1804. Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites. Wisconsin Historical Collections, vol. XX: 396-472, 1911.

Malhoit, Francois V. “A Wisconsin Fur Trader’s Journal, 1804-05.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Reuben Gold Thwaites. Vol. 19. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1910. 163-225. Print.

Nelson, George, Laura L. Peers, and Theresa M. Schenck. My First Years in the Fur Trade: The Journals of 1802-1804. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 2002. Print.

Perrault, Jean Baptiste. Narrative of The Travels And Adventures Of A Merchant Voyager In The Savage Territories Of Northern America Leaving Montreal The 28th of May 1783 (to 1820) ed. and Introduction by, John Sharpless Fox. Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections. vol. 37. Lansing: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, Crawford Co., 1900.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Information Respecting The History,Condition And Prospects OF The Indian Tribes Of The United States. Illustrated by Capt. S. Eastman. Published by the Authority of Congress. Part III. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Company, 1953.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi. East Lansing: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his