When we die, we will lay our bones at La Pointe.

March 20, 2024

By Leo

From individual historical documents, it can be hard to sequence or make sense of the efforts of the United States to remove the Lake Superior Ojibwe from ceded territories of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan in the years 1850 and 1851. Most of us correctly understand that the Sandy Lake Tragedy was caused an alliance of government and trading interests. Through greed, deception, racism, and callous disregard for human life, government officials bungled the treaty payment at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi River in the fall and winter of 1850-51, leading to hundreds of deaths. We also know that in the spring of 1852, Chief Buffalo and a delegation of La Pointe Ojibwe chiefs travelled to Washington D.C. to oppose the removal. It is what happened before and between those events, in the summers of 1850 and 1851, where things get muddled.

Confusion arises because the individual documents can contradict our narrative. A particular trader, who we might want to think is one of the villains, might express an anti-removal view. A government agent, who we might wish to assign malicious intent, instead shows merely incompetence. We find a quote or letter that seems to explain the plans and sentiments leading to the disaster at Sandy Lake, but then we find the quote is dated after the deaths had already occurred.

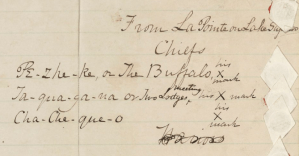

Therefore, we are fortunate to have the following letter, written in November of 1851, which concisely summarizes the events up to that point. We are even more fortunate that the letter is written by chiefs, themselves. It is from the Office of Indian Affairs archives, but I found a copy in the Theresa Schenck papers. It is not unknown to Lake Superior scholarship, but to my knowledge it has not been reproduced in full.

The context is that Chief Buffalo, most (but not all) of the La Pointe chiefs, and some of their allies from Ontonagon, L’Anse, Upper St. Croix Lake, Chippewa River and St. Croix River, have returned to La Pointe. They have abandoned the pay ground at Fond du Lac in November 1851, and returned to La Pointe. This came after getting confirmation that the Indian Agent, John S. Watrous, has been telling a series of lies in order to force a second Sandy Lake removal–just one year removed from the tragedy. This letter attempts to get official sanction for a delegation of La Pointe chiefs to visit Washington. The official sanction never came, but the chiefs went anyway, and the rest is history.

La Pointe, Lake Superior, Nov. 6./51

To the Hon Luke Lea

Commissioner of Indian Affairs Washington D.C.

Our Father,

We send you our salutations and wish you to listen to our words. We the Chiefs and head men of the Chippeway Tribe of Indians feel ourselves aggrieved and wronged by the conduct of the U.S. Agent John S. Watrous and his advisors now among us. He has used great deception towards us, in carrying out the wishes of our Great Father, in respect to our removal. We have ever been ready to listen to the words of our Great Father whenever he has spoken to us, and to accede to his wishes. But this time, in the matter of our removal, we are in the dark. We are not satisfied that it is the President that requires us to remove. We have asked to see the order, and the name of the President affixed to it, but it has not been shewn us. We think the order comes only from the Agent and those who advise with him, and are interested in having us remove.

Kicheueshki. Chief. X his mark

Gejiguaio X “

Kishkitauʋg X “

Misai X “

Aitauigizhik X “

Kabimabi X “

Oshoge, Chief X “

Oshkinaue, Chief X “

Medueguon X “

Makudeua-kuʋt X “

Na-nʋ-ʋ-e-be, Chief X “

Ka-ka-ge X “

Kui ui sens X “

Ma-dag ʋmi, Chief X “

Ua-bi-shins X “

E-na-nʋ-kuʋk X “

Ai-a-bens, Chief X “

Kue-kue-Kʋb X “

Sa-gun-a-shins X “

Ji-bi-ne-she, Chief X “

Ke-ui-mi-i-ue X “

Okʋndikʋn, Chief X “

Ang ua sʋg X “

Asinise, Chief X “

Kebeuasadʋn X “

Metakusige X “

Kuiuisensish, Chief X “

Atuia X “

Gete-kitigani[inini? manuscript torn]

L. H. Wheeler

We the undersigned, certify, on honor, that the above document was shown to us by the Buffalo, Chief of the Lapointe band of Chippeway Indians and that we believe, without implying and opinion respecting the subjects of complaint contained in it, that it was dictated by, and contains the sentiments of those whose signatures are affixed to it.

S. Hall

C. Pulsifer

H. Blatchford

When I started Chequamegon History in 2013, the WordPress engine made it easy to integrate their features with some light HTML coding. In recent years, they have made this nearly impossible. At some point, we’ll have to decide whether to get better at coding or overhaul our signature “blue rectangle” design format. For now, though, I can’t get links or images into the blue rectangles like I used to, so I will have to list them out here:

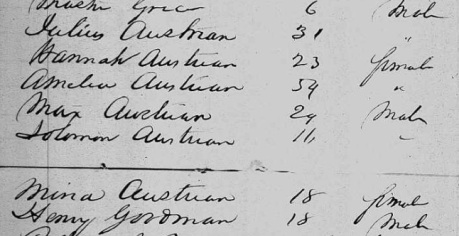

Joseph Austrian’s description of the same

Boutwell’s acknowledgement of the suspension of the removal order, and his intent to proceed anyway

Chequamegon History has looked into the “Great Father” fur trade theater language of ritual kinship before in our look at Blackbird’s speech at the 1855 Payment. You may have noticed Makadebines (Blackbird) didn’t sign this letter. He was working on a different plant to resist removal. Look for a related post soon.

If you’re really interested in why the president was Gichi-noos (Great Father), read these books:

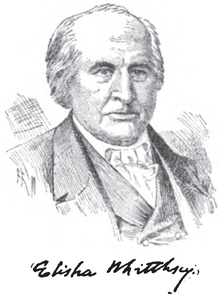

Watrous, and many of the Americans who came to the Lake Superior country at this time, were from northeastern Ohio. Watrous was able to obtain and keep his position as agent because his family was connected to Elisha Whittlesey.

In the summer and fall of 1851, Watrous was determined to get soldiers to help him force the removal. However, by that point, Washington was leaning toward letting the Lake Bands stay in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Last spring, during one of the several debt showdowns in Congress, I wrote on how similar antics in Washington contributed to the disaster of 1850. My earliest and best understanding of the 1850-1852 timeline, and the players involved, comes from this book:

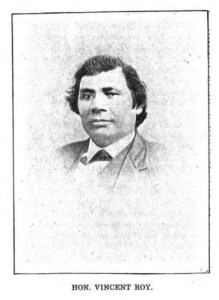

We know that Kishkitauʋg (Cut Ear), and Oshoge (Heron) went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852. Benjamin Armstrong’s account is the most famous, but the delegation’s other interpreter, Vincent Roy Jr., also left his memories, which differ slightly in the details.

One of my first posts on the blog involved some Sandy Lake material in the Wheeler Family Papers, written by Sherman Hall. Since then, having seen many more of their letters, I would change some of the initial conclusions. However, I still see Hall as having committing a great sin of omission for not opposing the removal earlier. Even with the disclaimer, however, I have to give him credit for signing his name to the letter this post is about. Although they shared the common goal of destroying Ojibwe culture and religion and replacing it with American evangelical Protestantism, he A.B.C.F.M. mission community was made up of men and women with very different personalities. Their internal disputes were bizarre and fascinating.

1838 more Petitions from La Pointe to the President

April 16, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs:

La Pointe Agency 1831-1839

National Archives Identifier: 164009310

O.I.A. Lapointe W.692.

Governor of Wisconsin

Mineral Pt. 15 Oct. 1838.

Encloses two communications

from D. P. Bushnell; one,

to speech of Jean B. DuBay, a half

breed Chippewa, delivered Aug. 15, ’38,

on behalf of the half breeds then assembled,

protesting against the decision

of the U.S. Court on the subject of the

murder of Alfred Aitkin by an Ind,

& again demanding the murderer;

with Mr Bushnell’s reply: the other,

dated 14 Aug. 1838, being a Report

in reference to the intermeddling of

any foreign Gov’t or its officers, with

the Ind’s within the limits of the U.S.

[Sentence in light text too faint to read]

12 April 1839.

Rec’d 17 Nov 1838.

See letter of 7 June 39 to Hon Lucius Lyon

Ans’d 12 April, 1839

W Ward

Superintendency of Indian Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point Oct 15, 1838.

Sir:

I have the honor to enclose herewith two communications from D. P. Bushnell Esq, Subagent of the Chippewas at La Pointe; the first, being the Speech of Jean B. DuBay, a half breed Chippewa, on behalf of the half-breeds assembled at La Pointe, on the 15th august last, in relation to the decision of the U.S. Court on the subject of the murder of Alfred Aitkin by an Indian; the last, in reference to the intermeddling of any foreign government, or the officers thereof, with the Indians within the limits of the United States.

Very respectfully

Your obed’t serv’t.

Henry Dodge

Sup’t Ind. Affs.

Hon. C. A. Harris

Com of Ind. Affairs.

D. P. Bushnell Aug. 14, 1838

W692

Subagency

La Pointe Aug 14th 1838

Sir

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your communication dated 7 ultimo enclosing an extract from a Resolution of the House of the Representatives of the 19th of March, 1838. No case of intermeddling by any foreign government on the officers, or subject thereof with the Indians under my charge or any others, directly , or indirectly, has come to my knowledge. It is believed that the English government has been in the Habit of distributing presents at a point on Lake Huron below Drummonds Island to the Chippewa for a series of years.

The Indians from this region, until recently, visited that place for their share of the annual distribution. But the Treaty made last summer between them and the United States, and the small distribution of presents that has been made within the Last Year, under the direction of our government, have had the effect to permit any of them from visiting, the English Territory this year. These Indians have generally manifested a desire to live upon terms of friendship with the American people. All of the Chiefs from the region of Lake Superior have expressed a desire to visit the seat of Gov’t where none of them have yet been. There is no doubt, but such a visit with the distribution of a few presents among them would be productive: of much good, and render their attachment to our Gov’t still stronger.

Very Resp’y

yr ms ob sev’t

D. P. Bushnell.

I. O. A.

To

His Excellency Henry Dodge

Ter, Wisconsin Sup’t Ind Affs

Half breed Speech

Speech of Jean B. DuBay,

a half breed Chippewa, on behalf of the half breeds assembled in a numerous body at the United States Sub Indian Agency office at La Pointe, on the 15th day of August 1838.

Father. We have come to you for the purpose of speaking on the subject of the murder that was committed two years ago by an Indian on one of our Brothers. I allude to Alfred Aitken. We have always considered ourselves Subject to the Laws of the United States and have consequently relied upon their protection. But it appears by the decision of the United Sates court in this case. “That it was an Indian Killed an Indian, on Indian ground, and died not therefore come under its jurisdiction,” that we have hitherto laboured under a delusion, and that a resort to the laws can avail nothing. We come therefore to you, at the agent of the Government here, to tell you that we have councilled with the Indians and, have declared to them and we have solemnly pledged ourselves in your presence, to each other, that we will enforce in the Indian Country, the Indian Law, Blood for Blood.

We pay taxes, and in the Indian Country are held amenable to the Laws, but appeal to them in vain for protection. Sir we will protect ourselves. We take the case into our own hands. Blood shall be shed! We will have justice and who can be answerable for the consequences? Our brother was a gentlemanly young man. He was educated at a Seminary in Louville in the State of New York. He was dear to us. We remember him as the companion of our childhood. The voice of his Blood now cries to us from the ground for vengence! But the stain left by his you shall be washed out by one of a deeper dye!

For injuries committed upon the persons or property of whites, although within the Indian Country we are still willing to be held responsible to the Laws of the United States, notwithstanding the decision of a United States Court that we are Indians. And for like injuries committed upon us by whites we will appeal to the same tribunal.

Sir our attachments to the American Government and people was great. But they have cast us off. The Half breeds muster strong on the northwestern frontier & we Know no distinction of tribes. In one thing at least we are all united. We might muster into the service of the United States in case of a war and officered by Americans would compose in frontier warfare a formidable corps. We can fight the Indian or white man, in his own manner, & would pledge ourselves to Keep peace among the different Indian tribes.

Sir we will do nothing rashly. We once more ask from your hands the murder of Mr. Aitken. We wish you to represent our case to the President and we promise to remain quiet for one year, giving ample time for his decision to be made Known. Let the Government extend its protection to us and we will be found its staunchest friends. If it persists in abandoning us the most painful consequences may ensue.

Sir we will listen to your reply, and shall be Happy to avail ourselves of your advice.

Reply of the Subagent.

My friends, I have lived several years on the frontier & have Known many half breeds. They have to my Knowledge paid taxes, & held offices under State, Territorial, and United States authorities, been treated in every respect by the Laws as American Citizens; and I have hitherto supposed they were entitled to the protection of the Laws. The decision of the court is this case, if court is a virtual acknowledgement of your title to the Indians as land, in common with the Indians & I see no other way for you to obtain satisfaction then to enforce the Indian Law. Indeed your own safety requires it. in the meantime I think the course you have adopted, in awaiting the results of this appeal is very proper, and cannot injure your cause although made in vain. At your request I will forward the words of your speaker, through the proper channel to the authorities at Washington. In the event of your being compelled to resort to the Indian mode of obtaining satisfaction it is to be hoped you will not wage an indiscriminate warfare. If you punish the guilty only, the Indians can have no cause for complaint, neither do I think they will complain. Any communication that may be made to me on this subject I will make Known to you in due time.

O.I.A. Lapointe. D.333.

Hon. Ja’s D. Doty.

New York. 25 March, 1839

Encloses Petition, dated

20 Dec. last, of Michel Nevou & 111

others, Chippewa Half Breeds, to the

President, complaining of the delay

in the payment of the sum granted

them, by Treaty of 29 July, 1837,

protesting against its payments on the

St Croix river, & praying that it be

paid at La Pointe on Lake Superior.

Recommends that the payment

be made at this latter place,

for reasons stated.

Rec’d 28 March, 1839.

Ans 29 Mch 1839.

(see over)

Mr Ward

D.100 3 Mch 28

Mch 38, 1839.

Indian Office.

The within may be

an [?] [?] [?] –

[guest?]. in fact will be

in accordance with [?]

[lat?] opinions and not of

the department.

W. Ward

New York

March 25, 1839

The Hon.

J.R. Pointsett

Secy of War

Sir,

I have the honour to submit to you a petition from the Half-breeds of the Chippewa Nation, which has just been received.

It must be obvious to you Sir, that the place from which the Indian Trade is prosecuted in the Country of that Nation is the proper place to collect the Half Breeds to receive their allowance under the Treaty. A very large number being employed by the Traders, if they are required to go to any other spot than La Pointe, they must lose their employment for the season. Three fourths of them visit La Pointe annually, in the course of the Trade. Very few either live or are employed on the St. Croix.

As an act of justice, and of humanity, to them I respectfully recommend that the payment be made to them under the Treaty at La Pointe.

I remain Sir, with very great respect

Your obedient Servant.

J D Doty

[D333-39.LA POINTE]

Hon.

J. D. Doty

March 29, 1839

Recorded in N 26

Page 192

[WD?] OIA

Mch 29, 1839

Sir

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 25th with the Petition of the Chippewa half breeds.

It is only necessary for me to observe his reply that it had been previously determined that the appropriation for them should be distributed at Lapointe, & the instructions with be given accordingly.

Very rcy

Hon.

J.D. Doty

New York

D100

D.333.

To the President of the United States of America

The Petition of the Half Breeds of the Chippewa nation respectfully shareth.

That we, Half Breeds of the Chippewa Nation, have recently learned, that the payment of the sum granted to the Chippewa Half Breeds, by virtue of the Treaty of 29th July 1837, has been deferred to next Spring, and, that the St Croix River has been selected as the place of payment.

That the delay in not having received our share of the above grant to the Chippewa Half Breeds, last summer, has caused us much loss, by keeping us from our regular vocations for several months, and by leaving many of us without means of support during winter, and that the arrangement of having the payment made next spring on the St Croix, will oblige us to perform a long and expensive Journey, leaving our families in our absence without any means of subsistance, and depriving us of all chance of being employed either in the Indian Trade or at fishing, by which means alone, we are able to earn our daily bread.

Your Petitioners with great deference and implicit submission to the pleasure of the President of the United States, respectfully pray, that an alteration may be made in the place assigned for payment and that Lapointe on Lake Superior may be fixed upon as the place of payment that place being the annual rendezvous of the Chippewa Half Breeds and the Chippewa Indians Traders, by whom we are employed.

And your Petitioners as in duty bound shall ever pray &c. &c.

Lake Superior Lapointe Dec. 20th 1838

Michel Neveu X his mark

Louis Neveu X his mark

Newel Neveu X his mark

Alexis Neveu X his mark

Joseph Danis X his mark

Benjamin Danis X his mark

Jean Bts Landrie Sen’r X his mark

Jean Bts Landrie Jun’r X his mark

Joseph Landrie X his mark

Jean Bts Trotercheau X his mark

George Trotercheau X his mark

Jean Bts Lagarde X his mark

Jean Bts Herbert X his mark

Antoine Benoit X his mark

Joseph Bellaire Sen’r X his mark

Joseph Bellaire Jun’r X his mark

Francois Bellaire X his mark

Vincent Roy X his mark

Jean Bts Roy X his mark

Francois Roy X his mark

Vincent Roy Jun’r X his mark

Joseph Roy X his mark

Simon Sayer X his mark

Joseph Morrison Sen’r X his mark

Joseph Morrison Jun’r X his mark

Geo. H Oakes

William Davenporte X his mark

Robert Davenporte X his mark

Joseph Charette X his mark

Chas Charette X his mark

George Bonga X his mark

Peter Bonga X his mark

Francois Roussain X his mark

Jean Bts Roussain X his mark

Joseph Montreal Maci X his mark

Joseph Montreal Larose X his mark

Paul Beauvier X his mark

Michel Comptories X his mark

Paul Bellanger X his mark

Joseph Roy Sen’r X his mark

John Aitkins X his mark

Alexander Aitkins X his mark

Alexis Bazinet X his mark

Jean Bts Bazinet X his mark

Joseph Bazinet X his mark

Michel Brisette X his mark

Augustin Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Gauthier X his mark

Isaac Ermatinger X his mark

Alexander Chaboillez X his mark

Michel Bousquet X his mark

Louis Bousquet X his mark

Antoine Cournoyer X his mark

Francois Bellanger X his mark

John William Bell, Jun’r

Jean Bts Robidoux X his mark

Robert Morin X his mark

Michel Petit Jun X his mark

Joseph Petit X his mark

Michel Petit Sen’r X his mark

Pierre Forcier X his mark

Jean Bte Rouleaux X his mark

Antoine Cournoyer X his mark

Louis Francois X his mark

Francois Lamoureaux X his mark

Francois Piquette X his mark

Benjamin Rivet X his mark

Robert Fairbanks X his mark

Benjamin Fairbanks X his mark

Antoine Maci X his mark

Joseph Maci X his mark

Edward Maci X his mark

Alexander Maci X his mark

Joseph Montreal Jun. X his mark

Peter Crebassa X his mark

Ambrose Davenporte X his mark

George Fairbanks X his mark

Francois Lemieux X his mark

Pierre Lemieux X his mark

Jean Bte Lemieux X his mark

Baptist St. Jean X his mark

Francis St Jean X his mark

Francis Decoteau X his mark

Jean Bte Brisette X his mark

Henry Brisette X his mark

Charles Brisette X his mark

Jehudah Ermatinger X his mark

Elijah Eramtinger X his mark

Jean Bte Cadotte X his mark

Charles Morrison X his mark

Louis Cournoyer X his mark

Jack Hotley X his mark

John Hotley X his mark

Gabriel Lavierge X his mark

Alexis Brebant X his mark

Eunsice Childes

Etienne St Martin X his mark

Eduard St Arnaud X his mark

Paul Rivet X his mark

Louisan Rivet X his mark

John Fairbanks X his mark

William Fairbanks X his mark

Theodor Borup

James P Scott

Bazil Danis X his mark

Alexander Danis X his mark

Joseph Danis X his mark

Souverain Danis X his mark

Frances Dechonauet

Joseph La Pointe X

Joseph Dafault X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Signed in Presnce of

John Angus

John Wood

John William Bell Sen’r

Antoine Perinier

Grenville T. Sproat

Jay P. Childes

C. La Rose

Chs W. Borup

James P. Scott

Henry Blatchford

1837 Petitions from La Pointe to the President

January 29, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs:

La Pointe Agency 1831-1839

National Archives Identifier: 164009310

O. I. A. La Pointe J171.

Hon Geo. W. Jones

Ho. of Reps. Jany 9, 1838

Transmits petition dated 31st Augt 1837, from Michel Cadotte & 25 other Chip. Half Breeds, praying that the amt to be paid them, under the late Chip. treaty, be distributed at La Pointe, and submitting the names of D. P. Bushnell, Lyman M. Warren, for the appt of Comsr to make the distribution.

Transmits it, that it may receive such attention as will secure the objects of the petitioners, says as the treaty has not been satisfied it may be necessary to bring the subject of the petition before the Comsr Ind Affrs of the Senate.

Recd 10 Jany 1838

file

[?] File.

House of Representatives Jany 9th 1838

Sir

I hasten to transmit the inclosed petition, with the hope, that the subject alluded to, may receive such attention, as to secure the object of the petitioners. As the Chippewa Treaty has not yet been ratified it may be necessary to bring the subject of the petition before the Committee of Indian Affairs of the Senate.

I am very respectfully

Your obt svt

Geo W. Jones

C. A. Harris Esqr

Comssr of Indian Affairs

War Department

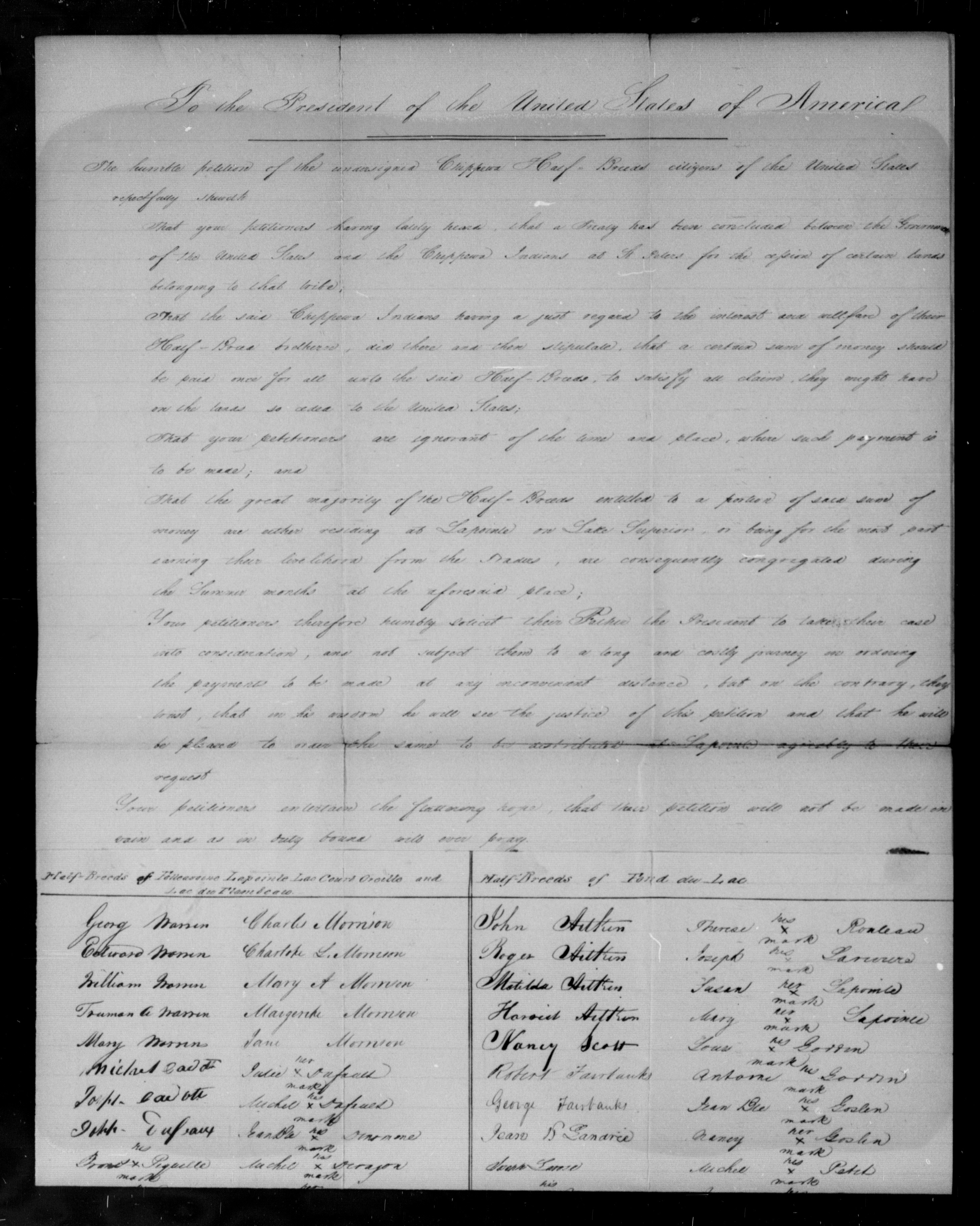

To the President of the United States of America

The humble petition of the undersigned Chippewa Half-Breeds citizens of the United Sates, respectfully Shareth:

Bizhiki (Buffalo), Dagwagaane (Two Lodges Meet), and Jechiikwii’o (Snipe, aka Little Buffalo) signed the 1837 Treaty of St Peters for the La Pointe Band.

That, your petitioners having lately heard that a Treaty had been concluded between the Government of the United Sates and the Chippewa Indians at St Peters, for the cession of certain lands belonging to that tribe:

ARTICLE 3.

“The sum of one hundred thousand dollars shall be paid by the United States, to the half-

breeds of the Chippewa nation, under the direction of the President. It is the wish of the

Indians that their two sub-agents Daniel P. Bushnell, and Miles M. Vineyard, superintend

the distribution of this money among their half-breed relations.”

That, the said Chippewa Indians X, having a just regard to the interest and welfare of their Half Breed brethren, did there and then stipulate; that, a certain sum of money should be paid once for all unto the said Half-Breeds, to satisfy all claim they might have on the lands so ceded to the United States.

That, your petitioners are ignorant of the time and place where such payment is to be made.

That the great majority of the Half-Breeds entitled to a distribution of said sum of money, are either residing at La Pointe on Lake Superior, or being for the most part earning their livelihood from the Traders, are consequently congregated during the summer months at the aforesaid place.

Your petitioners humbly solicit their father the President, to take their case into consideration, and not subject them to a long and costly journey in ordering the payments to be made at any inconvenient distance, but on the contrary they trust that in his wisdom he will see the justice of their demand in requiring he will be pleased to order the same to be distributed at Lapointe agreeable to their request.

Your petitioners would also intimate that, although they are fully aware that the Executive will make a judicious choice in the appointment of the Commissioners who will be selected to carry into effect the Provisions of said Treaty, yet, they would humbly submit to the President, that they have full confidence in the integrity of D. P. Bushnell Esqr. resident Indian Agent for the United States at this place and Lyman M Warren Esquire, Merchant.

Your petitioners entertain the flattering hope, that, their petition will not be made in vain, and as in duty bound will ever pray.

La Pointe, Lake Superior,

Territory of Wisconsin 31st August 1837

Michel Cadotte

Michel Bosquet X his mark

Seraphim Lacombe X his mark

Joseph Cadotte X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Chs W Borup for wife & Children

A Morrison for wife & children

Pierre Cotte

Henry Cotte X his mark

Frances Roussan X his mark

James Ermatinger for wife & family

Lyman M Warren for wife & family

Joseph Dufault X his mark

Paul Rivet X his mark for wife & family

Charles Chaboullez wife & family

George D. Cameron

Alixis Corbin

Louis Corbin

Jean Bste Denomme X his mark and family

Ambrose Deragon X his mark and family

Robert Morran X his mark ” “

Jean Bst Couvillon X his mark ” “

Alix Neveu X his mark ” “

Frances Roy X his mark ” “

Alixis Brisbant X his mark ” “

Signed in presence of G. Pauchene

John Livingston

O.I.A. La Pointe W424.

Governor of Wisconsin

Mineral Pt. Feby 19, 1838

Transmits the talk of “Buffalo,” a Chip. Chief, delivered at the La Pointe SubAgt, Dec. 9, 1837, asking that the am. due the half-breeds under the late Treaty, be divided fairly among them, & paid them there, as they will not go to St Peters for it, &c.

Says Buffalo has great influence with his tribe, & is friendly to the whites; his sentiments accord with most of those of the half-breeds & Inds in that part of the country.

File

Recd 13 March 1838

[?] File.

Superintendency of Indian Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point, Feby 19, 1838

Sir,

I have the honor to inclose the talk of “Buffalo,” a principal chief of the Chippewa Indians in the vicinity of La Pointe, delivered on the 9th Dec’r last before Mr Bushnell, sub-agent of the Chippewas at that place. Mr. Bushnell remarks that the speech is given with as strict an adherence to the letter as the language will admit, and has no doubt the sentiments expressed by this Chief accord with those of most of the half-breeds and Indians in that place of the Country. The “Buffalo” is a man of great influence among his tribe, and very friendly to the whites.

Very respectfully,

Your obed’t sevt.

Henry Dodge

Supt Ind Affs

Hon C. A. Harris

Com. of Ind. Affairs

Subagency

Lapointe Dec 10 1837

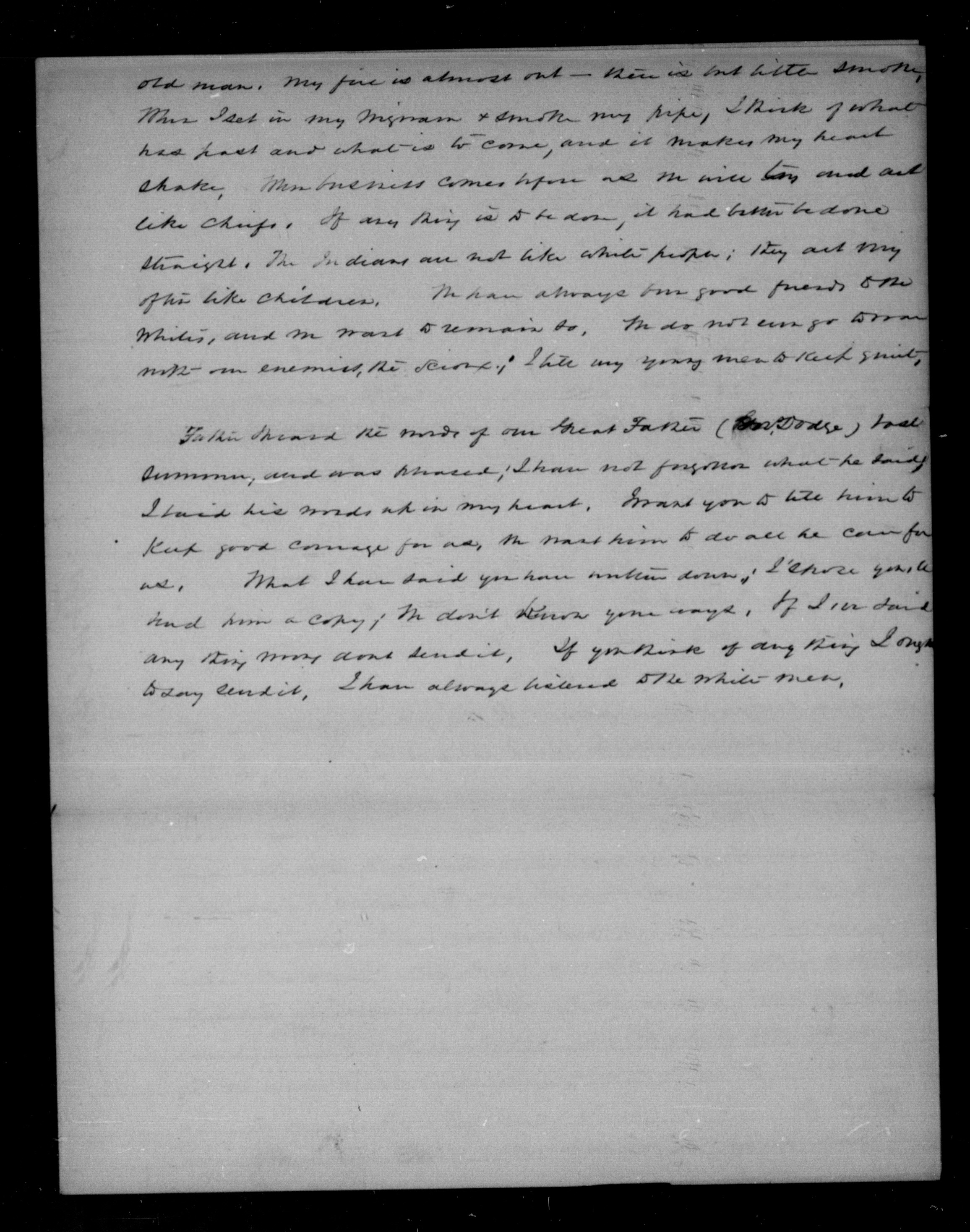

Speech of the Buffalo principal Chief at Lapointe

Father I told you yesterday I would have something to say to you today. What I say to you now I want you to write down, and send it to the Great American Chief that we saw at St Peters last summer, (Gov. Dodge). Yesterday, I called all the Indians together, and have brought them here to hear what I say; I speak the words of all.

ARTICLE 1.

“The said Chippewa nation cede to the United States all that tract of country included

within the following boundaries:

[…]

thence to and along the dividing ridge between the waters of Lake Superior and those of the Mississippi

[…]“

Father it was not my voice, that sold the country last summer. The land was not mine; it belonged to the Indians beyond the mountains. When our Great Father told us at St Peters that it was only the country beyond the mountains that he wanted I was glad. I have nothing to say about the Treaty, good, or bad, because the country was not mine; but when it comes my time I shall know how to act. If the Americans want my land, I shall know what to say. I did not like to stand in the road of the Indians at St Peters. I listened to our Great Father’s words, & said them in my heart. I have not forgotten them. The Indians acted like children; they tried to cheat each other and got cheated themselves. When it comes my time to sell my land, I do not think I shall give it up as they did.

What I say about the payment I do not say on my own account; for myself I do not care; I have always been poor, & don’t want silver now. But I speak for the poor half breeds.

There are a great many of them; more than would fill your house; some of them are very poor They cannot go to St Peters for their money. Our Great Father told us at St Peters, that you would divide the money, among the half breeds. You must not mind those that are far off, but divide it fairly, and give the poor women and children a good share.

Father the Indians all say they will not go to St Peters for their money. Let them divide it in this parts if they choose, but one must have ones here. You must not think you see all your children here; there are so many of them, that when the money and goods are divided, there will not be more than half a Dollar and a breech cloth for each one. At Red Cedar Lake the English Trader (W. Aitken) told the Indians they would not have more than a breech cloth; this set them to thinking. They immediately held a council & their Indian that had the paper (The Treaty) said he would not keep it, and would send it back.

It will not be my place to come in among the first when the money is paid. If the Indians that own the land call me in I shall come in with pleasure.

ARTICLE 4.

“The sum of seventy thousand dollars shall be applied to the payment, by the United States, of certain claims against the Indians; of which amount twenty eight thousand dollars shall, at their request, be paid to William A. Aitkin, twenty five thousand to Lyman M. Warren, and the balance applied to the liquidation of other just demands against them—which they acknowledge to be the case with regard to that presented by Hercules L. Dousman, for the sum of five thousand dollars; and they request that it be paid.“

We are afraid of one Trader. When at St Peters I saw that they worked out only for themselves. They have deceived us often. Our Great Father told us he would pay our old debts. I thought they should be struck off, but we have to pay them. When I heard our debts would be paid, it done my heart good. I was glad; but when I got back here my joy was gone. When our money comes here, I hope our Traders will keep away, and let us arrange our own business, with the officers that the President sends here.

Father I speak for my people, not for myself. I am an old man. My fire is almost out – there is but little smoke. When I set in my wigwam & smoke my pipe, I think of what has past and what is to come, and it makes my heart shake. When business comes before us we will try and act like chiefs. If any thing is to be done, it had better be done straight. The Indians are not like white people; they act very often like children. We have always been good friends to the whites, and we want to remain so. We do not [even?] go to war with our enemies, the Sioux; I tell my young men to keep quiet.

Father I heard the words of our Great Father (Gov. Dodge) last summer, and was pleased; I have not forgotten what he said. I have his words up in my heart. I want you to tell him to keep good courage for us, we want him to do all he can for us. What I have said you have written down; I [?] you to hand him a copy; we don’t know your ways. If I [?] said any thing [?] dont send it. If you think of any thing I ought to say send it. I have always listened to the white men.

O.I.A. Lapointe, B.458

D. P. Bushnell

Lapointe, March 8, 1838

At the request of some of the petitioners, encloses a petition dated 7 March 1838, addressed to the Prest, signed by 167 Chip. half breeds, praying that the amt stipulated by the late Chip. Treaty to be paid to the half breeds, to satisfy all claims they ma have on the lands ceded by this Treaty, may be distributed at Lapointe.

Hopes their request will be complied with; & thinks their annuity should likewise be paid at Lapointe.

File

Recd 2nd May, 1838

Subagency

Lapointe Mch 6 1838

Sir

I have the honor herewith to enclose a petition addressed to the President of the United States, handed to me with a request by several of the petitioners that I would forward it. The justice of the demand of these poor people is so obvious to any one acquainted with their circumstances, that I cannot omit this occasion to second it, and to express a sincere hope that it will be complied with. Indeed, if the convenience and wishes of the Indians are consulted, and as the sum they receive for their country is so small, these should, I conciev, be principle considerations, their annuity will likewise as paid here; for it is a point more convenient of access for the different bands, that almost any other in their own country, and one moreover, where they have interests been in the habit of assembling in the summer months.

I am sir, with great respect,

your most obt servant,

D. P. Bushnell

O. I. A.

C. A. Harris Esqr.

Comr Ind. Affs

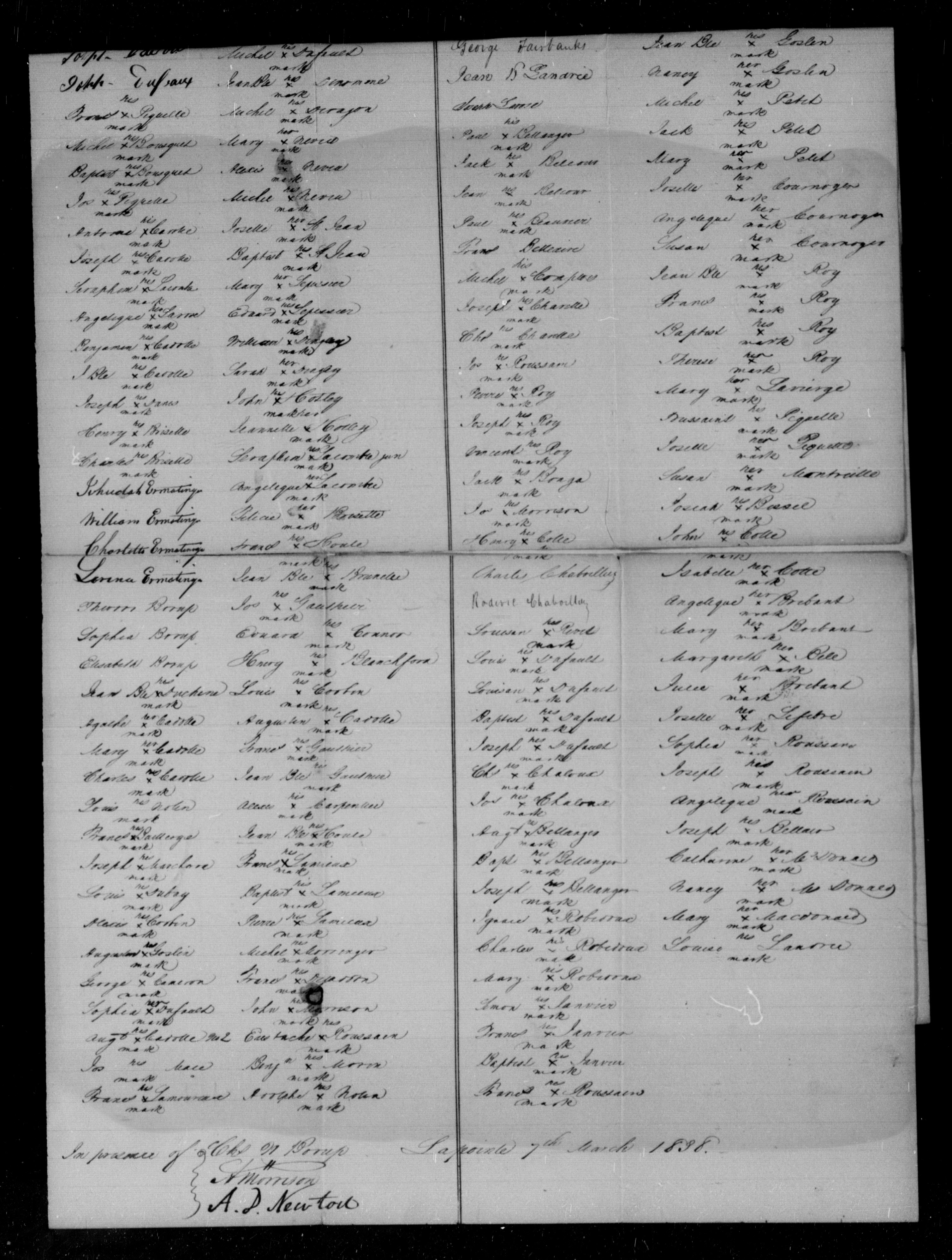

To the President of the United States of America

The humble petition of the undersigned Chippewa Half-Breeds citizens of the United States respectfully shareth

That your petitioners having lately heard, that a Treaty has been concluded between the Government of the United States and the Chippewa Indians at St Peters for the cession of certain lands belonging to that tribe;

That the said Chippewa Indians having a just regard to the interest and wellfare of their Half-Breed brethern, did there and then stipulate, that a certain sum of money should be paid once for all unto the said Half-Breeds, to satisfy all claims, they might have on the lands so ceded to the United States;

That your petitioners are ignorant of the time and place, where such payment is to be made; and

That the great majority of the Half-Breeds entitled to a portion of said sum of money are either residing at Lapointe on Lake Superior, or being for the most part earning their livelihood from the Traders, are consequently congregated during the summer months at the aforesaid place;

Your petitioners therefore humbly solicit their Father the President to take their case into consideration, and not subject them to a long and costly journey on ordering the payment to be made at any convenient distance, but on the contrary, they wish, that in his wisdom he will see the justice of this petition and that he will be pleased to order the same to be distributed at Lapointe agreeably to their request.

Your petitioners entertain the flattering hope, that their petition will not be made in vain and as in duly bound will ever pray.

Half Breeds of Folleavoine Lapointe Lac Court Oreilles and Lac du Flambeau

Georg Warren

Edward Warren

William Warren

Truman A Warren

Mary Warren

Michel Cadott

Joseph Cadotte

Joseph Dufault

Frances Piquette X his mark

Michel Bousquet X his mark

Baptiste Bousquet X his mark

Jos Piquette X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Cadotte X his mark

Seraphim Lacombre X his mark

Angelique Larose X her mark

Benjamin Cadotte X his mark

J Bte Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Danis X his mark

Henry Brisette X his mark

Charles Brisette X his mark

Jehudah Ermatinger

William Ermatinger

Charlotte Ermatinger

Larence Ermatinger

Theodore Borup

Sophia Borup

Elisabeth Borup

Jean Bte Duchene X his mark

Agathe Cadotte X her mark

Mary Cadotte X her mark

Charles Cadotte X his mark

Louis Nolin _ his mark

Frances Baillerge X his mark

Joseph Marchand X his mark

Louis Dubay X his mark

Alexis Corbin X his mark

Augustus Goslin X his mark

George Cameron X his mark

Sophia Dufault X her mark

Augt Cadotte No 2 X his mark

Jos Mace _ his mark

Frances Lamoureau X his mark

Charles Morrison

Charlotte L. Morrison

Mary A Morrison

Margerike Morrison

Jane Morrison

Julie Dufault X her mark

Michel Dufault X his mark

Jean Bte Denomme X his mark

Michel Deragon X his mark

Mary Neveu X her mark

Alexis Neveu X his mark

Michel Neveu X his mark

Josette St Jean X her mark

Baptist St Jean X his mark

Mary Lepessier X her mark

Edward Lepessier X his mark

William Dingley X his mark

Sarah Dingley X her mark

John Hotley X his mark

Jeannette Hotley X her mark

Seraphim Lacombre Jun X his mark

Angelique Lacombre X her mark

Felicia Brisette X her mark

Frances Houle X his mark

Jean Bte Brunelle X his mark

Jos Gauthier X his mark

Edward Connor X his mark

Henry Blanchford X his mark

Louis Corbin X his mark

Augustin Cadotte X his mark

Frances Gauthier X his mark

Jean Bte Gauthier X his mark

Alexis Carpentier X his mark

Jean Bte Houle X his mark

Frances Lamieux X his mark

Baptiste Lemieux X his mark

Pierre Lamieux X his mark

Michel Morringer X his mark

Frances Dejaddon X his mark

John Morrison X his mark

Eustache Roussain X his mark

Benjn Morin X his mark

Adolphe Nolin X his mark

Half-Breeds of Fond du Lac

John Aitken

Roger Aitken

Matilda Aitken

Harriet Aitken

Nancy Scott

Robert Fairbanks

George Fairbanks

Jean B Landrie

Joseph Larose

Paul Bellanges X his mark

Jack Belcour X his mark

Jean Belcour X his mark

Paul Beauvier X his mark

Frances Belleaire

Michel Comptois X his mark

Joseph Charette X his mark

Chl Charette X his mark

Jos Roussain X his mark

Pierre Roy X his mark

Joseph Roy X his mark

Vincent Roy X his mark

Jack Bonga X his mark

Jos Morrison X his mark

Henry Cotte X his mark

Charles Chaboillez

Roderic Chaboillez

Louison Rivet X his mark

Louis Dufault X his mark

Louison Dufault X his mark

Baptiste Dufault X his mark

Joseph Dufault X his mark

Chs Chaloux X his mark

Jos Chaloux X his mark

Augt Bellanger X his mark

Bapt Bellanger X his mark

Joseph Bellanger X his mark

Ignace Robidoux X his mark

Charles Robidoux X his mark

Mary Robidoux X her mark

Simon Janvier X his mark

Frances Janvier X his mark

Baptiste Janvier X his mark

Frances Roussain X his mark

Therese Rouleau X his mark

Joseph Lavierire X his mark

Susan Lapointe X her mark

Mary Lapointe X her mark

Louis Gordon X his mark

Antoine Gordon X his mark

Jean Bte Goslin X his mark

Nancy Goslin X her mark

Michel Petit X his mark

Jack Petit X his mark

Mary Petit X her mark

Josette Cournoyer X her mark

Angelique Cournoyer X her mark

Susan Cournoyer X her mark

Jean Bte Roy X his mark

Frances Roy X his mark

Baptist Roy X his mark

Therese Roy X her mark

Mary Lavierge X her mark

Toussaint Piquette X his mark

Josette Piquette X her mark

Susan Montreille X her mark

Josiah Bissel X his mark

John Cotte X his mark

Isabelle Cotte X her mark

Angelique Brebant X her mark

Mary Brebant X her mark

Margareth Bell X her mark

Julie Brebant X her mark

Josette Lefebre X her mark

Sophia Roussain X her mark

Joseph Roussain X his mark

Angelique Roussain X her mark

Joseph Bellair X his mark

Catharine McDonald X her mark

Nancy McDonald X her mark

Mary Macdonald X her mark

Louise Landrie X his mark

In presence of

Chs W Borup

A Morrison

A. D. Newton

Lapointe 7th March 1838

Early Life among the Indians: Chapter II

March 21, 2018

By Amorin Mello

Early life among the Indians

by Benjamin Green Armstrong

continued from Chapter I.

CHAPTER II

In Washington.—Told to Go Home.—Senator Briggs, of New York.—The Interviews with President Fillmore.—Reversal of the Removal Order.—The Trip Home.—Treaty of 1854 and the Reservations.—The Mile Square.—The Blinding. »

After a fey days more in New York City I had raised the necessary funds to redeem the trinkets pledged with the ‘bus driver and to pay my hotel bills, etc., and on the 22d day of June, 1852, we had the good fortune to arrive in Washington.

“Washington Delegation, June 22, 1852“

Engraved from an unknown photograph by Marr and Richards Co. for Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians. Chief Buffalo, his speaker Oshogay, Vincent Roy, Jr., two other La Pointe Band members, and Armstrong are assumed to be in this engraving.

I took my party to the Metropolitan Hotel and engaged a room on the first floor near the office for the Indians, as they said they did not like to get up to high in a white man’s house. As they required but a couple mattresses for their lodgings they were soon made comfortable. I requested the steward to serve their meals in their room, as I did not wish to take them into the dining room among distinguished people, and their meals were thus served.

Undated postcard of the Metropolitan Hotel, formerly known as Brown’s India Queen Hotel.

~ StreetsOfWashington.com

The morning following our arrival I set out in search of the Interior Department of the Government to find the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to request an interview with him, which he declined to grant and said :

“I want you to take your Indians away on the next train west, as they have come here without permission, and I do not want to see you or hear of your Indians again.”

I undertook to make explanations, but he would not listen to me and ordered me from his office. I went to the sidewalk completely discouraged, for my present means was insufficient to take them home. I paced up and down the sidewalk pondering over what was best to do, when a gentleman came along and of him I inquired the way to the office of the Secretary of the Interior. He passed right along saying,

Secretary of the Interior

Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart

~ Department of the Interior

“This way, sir; this way, sir;” and I followed him.

He entered a side door just back of the Indian Commissioner’s office and up a short flight of stairs, and going in behind a railing, divested himself of hat and cane, and said :

“What can I do for you sir.”

I told him who I was, what my party consisted of, where we came from and the object of our visit, as briefly as possible. He replied that I must go and see the Commissioner of Indian Affairs just down stairs. I told him I had been there and the treatment I had received at his hands, then he said :

“Did you have permission to come, and why did you not go to your agent in the west for permission?”

I then attempted to explain that we had been to the agent, but could get no satisfaction; but he stopped me in the middle of my explanation, saying :

“I can do nothing for you. You must go to the Indian Commissioner,”

and turning, began a conversation with his clerk who was there when we went in.

I walked out more discouraged than ever and could not imagine what next I could do. I wandered around the city and to the Capitol, thinking I might find some one I had seen before, but in this I failed and returned to the hotel, where, in the office I found Buffalo surrounded by a crowd who were trying to make him understand them and among them was the steward of the house. On my entering the office and Buffalo recognizing me, the assemblage, seeing I knew him, turned their attention to me, asking who he was, etc., to all of which questions I answered as briefly as possible, by stating that he was the head chief of of the Chippewas of the Northwest. The steward then asked:

“Why don’t you take him into the dining room with you? Certainly such a distinguished man as he, the head of the Chippewa people, should have at least that privilege.”

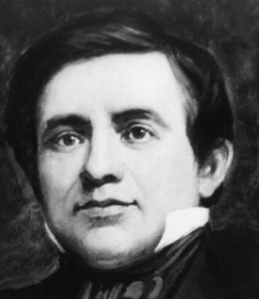

United States Representative George Briggs

~ Library of Congress

I did so and as we passed into the dining room we were shown to a table in one corner of the room which was unoccupied. We had only been seated a few moments when a couple of gentlemen who had been occupying seats in another part of the dining room came over and sat at our table and said that if there were no objections they would like to talk with us. They asked about the party, where from, the object of the visit, etc. I answered them briefly, supposing them to be reporters and I did not care to give them too much information. One of these gentlemen asked what room we had, saying that himself and one or two others would like to call on us right after dinner. I directed them where to come and said I would be there to meet them.

About 2 o’clock they came, and then for the first time I knew who those gentlemen were. One was Senator Briggs, of New York, and the others were members of President Filmore’s cabinet, and after I had told them more fully what had taken me there, and the difficulties I had met with, and they had consulted a little while aside. Senator Briggs said :

“We will undertake to get you and your people an interview with the President, and will notify you here when a meeting can be arranged. ”

During the afternoon I was notified that an interview had been arranged for the next afternoon at 3 o’clock. During the evening Senator Briggs and other friends called, and the whole matter was talked over and preparations made for the interview the following day, which were continued the next day until the hour set for the interview.

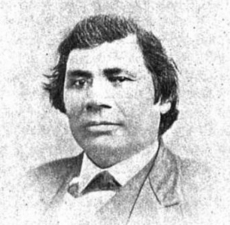

United States President

Millard Fillmore.

~ Library of Congress

When we were assembled Buffalo’s first request was that all be seated, as he had the pipe of peace to present, and hoped that all who were present would partake of smoke from the peace pipe. The pipe, a new one brought for the purpose, was filled and lighted by Buffalo and passed to the President who took two or three draughts from it, and smiling said, “Who is the next?” at which Buffalo pointed out Senator Briggs and desired he should be the next. The Senator smoked and the pipe was passed to me and others, including the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Secretary of the Interior and several others whose names I did not learn or cannot recall. From them, to Buffalo, then to O-sho-ga, and from him to the four braves in turn, which completed that part of the ceremony. The pipe was then taken from the stem and handed to me for safe keeping, never to be used again on any occasion. I have the pipe still in my possession and the instructions of Buffalo have been faithfully kept. The old chief now rose from his seat, the balance following his example and marched in single file to the President and the general hand-shaking that was began with the President was continued by the Indians with all those present. This over Buffalo said his under chief, O-sha-ga, would state the object of our visit and he hoped the great father would give them some guarantee that would quiet the excitement in his country and keep his young men peaceable. After I had this speech thoroughly interpreted, O-sha-ga began and spoke for nearly an hour. He began with the treaty of 1837 and showed plainly what the Indians understood the treaty to be. He next took up the treaty of 1842 and said he did not understand that in either treaty they had ceded away the land and he further understood in both cases that the Indians were never to be asked to remove from the lands included in those treaties, provided they were peaceable and behaved themselves and this they had done. When the order to move came Chief Buffalo sent runners out in all directions to seek for reasons and causes for the order, but all those men returned without finding a single reason among all the Superior and Mississippi Indians why the great father had become displeased. When O-sha-ga had finished his speech I presented the petition I had brought and quickly discovered that the President did recognize some names upon it, which gave me new courage. When the reading and examination of it had been concluded the meeting was adjourned, the President directing the Indian Commissioner to say to the landlord at the hotel that our hotel bills would be paid by the government. He also directed that we were to have the freedom of the city for a week.

Read Biographical Sketch of Vincent Roy, Jr. manuscript for a different perspective on their meeting the President.

The second day following this Senator Briggs informed me that the President desired another interview that day, in accordance with which request we went to the White House soon after dinner and meeting the President, he told the, delegation in a brief speech that he would countermand the removal order and that the annuity payments would be made at La Pointe as before and hoped that in the future there would be no further cause for complaint. At this he handed to Buffalo a written instrument which he said would explain to his people when interpreted the promises he had made as to the removal order and payment of annuities at La Pointe and hoped when he had returned home he would call his chiefs together and have all the statements therein contained explained fully to them as the words of their great father at Washington.

The reader can imagine the great load that was then removed from my shoulders for it was a pleasing termination of the long and tedious struggle I had made in behalf of the untutored but trustworthy savage.

On June 28th, 1852, we started on our return trip, going by cars to La Crosse, Wis., thence by steamboat to St. Paul, thence by Indian trail across the country to Lake Superior. On our way from St. Paul we frequently met bands of Indians of the Chippewa tribe to whom we explained our mission and its results, which caused great rejoicing, and before leaving these bands Buffalo would tell their chief to send a delegation, at the expiration of two moons, to meet him in grand council at La Pointe, for there was many things he wanted to say to them about what he had seen and the nice manner in which he had been received and treated by the great father.

At the time appointed by Buffalo for the grand council at La Pointe, the delegates assembled and the message given Buffalo by President Filmore was interpreted, which gave the Indians great satisfaction. Before the grand council adjourned word was received that their annuities would be given to them at La Pointe about the middle of October, thus giving them time to get together to receive them. A number of messengers was immediately sent out to all parts of the territory to notify them and by the time the goods arrived, which was about October 15th, the remainder of the Indians had congregated at La Pointe. On that date the Indians were enrolled and the annuities paid and the most perfect satisfaction was apparent among all concerned. The jubilee that was held to express their gratitude to the delegation that had secured a countermanding order in the removal matter was almost extravagantly profuse. The letter of the great father was explained to them all during the progress of the annuity payments and Chief Buffalo explained to the convention what he had seen; how the pipe of peace had been smoked in the great father’s wigwam and as that pipe was the only emblem and reminder of their duties yet to come in keeping peace with his white children, he requested that the pipe be retained by me. He then went on and said that there was yet one more treaty to be made with the great father and he hoped in making it they would be more careful and wise than they had heretofore been and reserve a part of their land for themselves and their children. It was here that he told his people that he had selected and adopted, me as his son and that I would hereafter look to treaty matters and see that in the next treaty they did not sell them selves out and become homeless ; that as he was getting old and must soon leave his entire cares to others, he hoped they would listen to me as his confidence in his adopted son was great and that when treaties were presented for them to sign they would listen to me and follow my advice, assuring them that in doing so they would not again be deceived.

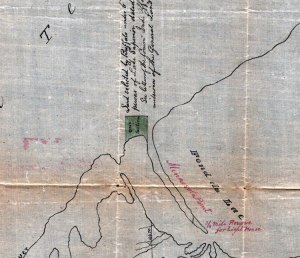

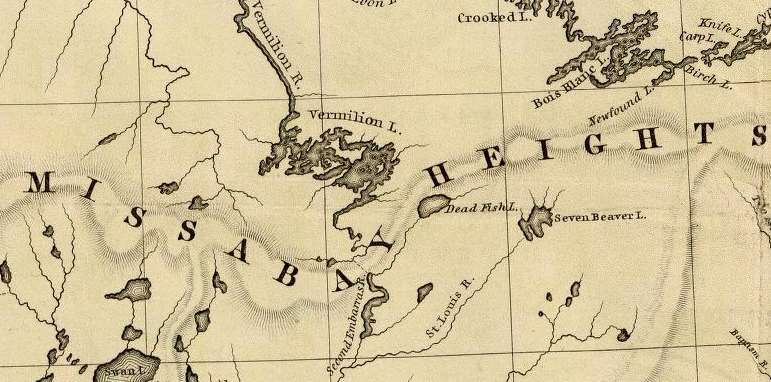

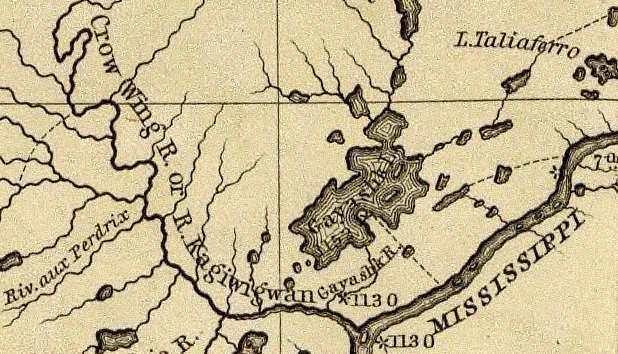

Map of Lake Superior Chippewa territories ceded in 1836, 1837, 1842, and 1854.

~ Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission

After this gathering of the Indians there was not much of interest in the Indian country that I can recall until the next annual payment in 1853. This payment was made at La Pointe and the Indians had been notified that commissioners would be appointed to make another treaty with them for the remainder of their territory. This was the territory lying in Minnesota west of Lake Superior; also east and west of the Mississippi river north to the territory belonging to the Boisfort and Pillager tribe, who are a part of the Chippewa nation, but through some arrangement between themselves, were detached from the main or more numerous body. It was at this payment that the Chippewa Indians proper desired to have one dollar each taken from their annuities to recompense me for the trouble and expense I had been to on the trip to Washington in their behalf, but I refused to accept it by reason of their very impecunious condition.

It was sometime in August, 1854, before the commissioners arrived at LaPointe to make the treaty and pay the annuities of that year. Messengers were despatched to notify all Indians of the fact that the great father had sent for them to come to La Pointe to get their money and clothing and to meet the government commissioners who wished to make another treaty with them for the territory lying west of Lake Superior and they were further instructed to have the Indians council among themselves before starting that those who came could be able to tell the wishes of any that might remain away in regards to a further treaty and disposition of their lands. Representatives came from all parts of the Chippewa country and showed a willingness to treat away the balance of their country. Henry C. Gilbert, the Indian agent at La Pointe, formerly of Ohio, and David B. Herriman, the agent for the Chippewas of the Mississippi country, were the commissioners appointed by the government to consumate this treaty.

While we were waiting the arrival of the interior Indians I had frequent talks with the commissioners and learned what their instructions were and about what they intended to offer for the lands which information I would communicate to Chief Buffalo and other head men in our immediate vicinity, and ample time was had to perfect our plans before the others should arrive, and when they did put in an appearance we were ready to submit to them our views for approval or rejection. Knowing as I did the Indians’ unwillingness to give up and forsake their old burying grounds I would not agree to any proposition that would take away the remainder of their lands without a reserve sufficient to afford them homes for themselves and posterity, and as fast as they arrived I counselled with them upon this subject and to ascertain where they preferred these reserves to be located. The scheme being a new one to them it required time and much talk to get the matter before them in its proper light. Finally it was agreed by all before the meeting of the council that no one would sign a treaty that did not give them reservations at different points of the country that would suit their convenience, that should afterwards be considered their bona-fide home. Maps were drawn of the different tracts that had been selected by the various chiefs for their reserve and permanent home. The reservations were as follows :

One at L’Anse Bay, one at Ontonagon, one at Lac Flambeau, one at Court O’Rilles, one at Bad River, one at Red Cliff or Buffalo Bay, one at Fond du Lac, Minn., and one at Grand Portage, Minn.

Joseph Stoddard (photo c.1941) worked on the 1854 survey of the Bad River Reservation exterior boundaries, and shared a different perspective about these surveys.

~ Bad River Tribal Historic Preservation Office

The boundaries were to be as near as possible by metes and bounds or waterways and courses. This was all agreed to by the Lake Superior Indians before the Mississippi Chippewas arrived and was to be brought up in the general council after they had come in, but when they arrived they were accompanied by the American Fur Company and most of their employees, and we found it impossible to get them to agree to any of our plans or to come to any terms. A proposition was made by Buffalo when all were gathered in council by themselves that as they could not agree as they were, a division should be drawn, dividing the Mississippi and the Lake Superior Indians from each other altogether and each make their own treaty After several days of counselling the proposition was agreed to, and thus the Lake Superiors were left to make their treaty for the lands mouth of Lake Superior to the Mississippi and the Mississippis to make their treaty for the lands west of the Mississippi. The council lasted several days, as I have stated, which was owing to the opposition of the American Fur Company, who were evidently opposed to having any such division made ; they yielded however, but only when they saw further opposition would not avail and the proposition of Buffalo became an Indian law. Our side was now ready to treat with the commissioners in open council. Buffalo, myself and several chiefs called upon them and briefly stated our case but were informed that they had no instructions to make any such treaty with us and were only instructed to buy such territory as the Lake Superiors and Mississippis then owned. Then we told them of the division the Indians had agreed upon and that we would make our own treaty, and after several days they agreed to set us off the reservations as previously asked for and to guarantee that all lands embraced within those boundaries should belong to the Indians and that they would pay them a nominal sum for the remainder of their possessions on the north shores. It was further agreed that the Lake Superior Indians should have two- thirds of all money appropriated for the Chippewas and the Mississippi contingent the other third. The Lake Superior Indians did not seem, through all these councils, to care so much for future annuities either in money or goods as they did for securing a home for themselves and their posterity that should be a permanent one. They also reserved a tract of land embracing about 100 acres lying across and along the Eastern end of La Pointe or Madeline Island so that they would not be cut off from the fishing privilege.

It was about in the midst of the councils leading up to the treaty of 1854 that Buffalo stated to his chiefs that I had rendered them services in the past that should be rewarded by something more substantial than their thanks and good wishes, and that at different times the Indians had agreed to reward me from their annuity money but I had always refused such offers as it would be taking from their necessities and as they had had no annuity money for the two years prior to 1852 they could not well afford to pay me in this way.

“And now,” continued Buffalo, “I have a proposition to make to you. As he has provided us and our children with homes by getting these reservations set off for us, and as we are about to part with all the lands we possess, I have it in my power, with your consent, to provide him with a future home by giving him a piece of ground which we are about to part with. He has agreed to accept this as it will take nothing from us and makes no difference with the great father whether we reserve a small tract of our territory or not, and if you agree I will proceed with him to the head of the lake and there select the piece of ground I desire him to have, that it may appear on paper when the treaty has been completed.”

The chiefs were unanimous in their acceptance of the proposition and told Buffalo to select a large piece that his children might also have a home in future as has been provided for ours.

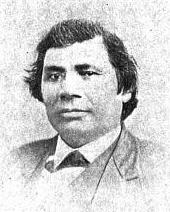

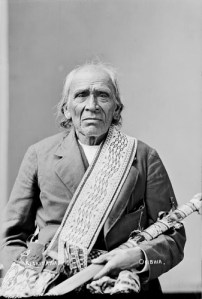

Kiskitawag (Giishkitawag: “Cut Ear”) signed earlier treaties as a warrior of the Ontonagon Band and became associated with the La Pointe Band at Odanah.

~C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections

This council lasted all night and just at break of day the old chief and myself, with four braves to row the boat, set out for the head of Lake Superior and did not stop anywhere only long enough to make and drink some tea, until we reached the head of St. Louis Bay. We landed our canoe by the side of a flat rock quite a distance from the shore, among grass and rushes. Here we ate our lunch and when completed Buffalo and myself, with another chief, Kish-ki-to-uk, waded ashore and ascended the bank to a small level plateau where we could get a better view of the bay. Here Buffalo turned to me, saying: .

“Are you satisfied with this location? I want to reserve the shore of this bay from the mouth of St. Louis river. How far that way do you you want it to go?” pointing southeast, or along the south shore of the lake.

I told him we had better not try to make it too large for if we did the great father’s officers at Washington might throw it out of the treaty and said:

“I will be satisfied with one mile square, and let it start from the rock which we have christened Buffalo rock, running easterly in the direction of Minnesota Point, taking in a mile square immediately northerly from the head of St. Louis Bay”

As there was no other way of describing it than by metes and bounds we tried to so describe it in the treaty, but Agent Gilbert, whether by mistake or not I am unable to say, described it differently. He described it as follows: “Starting from a rock immediately above and adjoining Minnesota Point, etc.”

We spent an hour or two here in looking over the plateau then went back to our canoe and set out for La Pointe. We traveled night and day until we reached home.

During our absence some of the chiefs had been talking more or less with the commissioners and immediately on our return all the Indians met in a grand council when Buffalo explained to them what he had done on the trip and how and where he had selected the piece of land that I was to have reserved in the treaty for my future home and in payment for the services I had rendered them in the past. The balance of the night was spent in preparing ourselves for the meeting with the treaty makers the next day, and about 10 o’clock next morning we were in attendance before the commissioners all prepared for a big council.

Agent Gilbert started the business by beginning a speech interpreted by the government interpreter, when Buffalo interrupted him by saying that he did not want anything interpreted to them from the English language by any one except his adoped son for there had always been things told to the Indians in the past that proved afterwards to be untrue, whether wrongly interpreted or not, he could not say;

“and as we now feel that my adopted son interprets to us just what you say, and we can get it correctly, we wish to hear your words repeated by him, and when we talk to you our words can be interpreted by your own interpreter, and in this way one interpreter can watch the other and correct each other should there be mistakes. We do not want to be deceived any more as we have in the past. We now understand that we are selling our lands as well as the timber and that the whole, with the exception of what we shall reserve, goes to the great father forever.”

Commissioner of Indian affairs. Col. Manypenny, then said to Buffalo:

“What you have said meets my own views exactly and I will now appoint your adopted son your interpreter and John Johnson, of Sault Ste. Marie, shall be the interpreter on the part of the government,” then turning to the commissioners said, “how does that suit you, gentlemen.”

They at once gave their consent and the council proceeded.

Buffalo informed the commissioners of what he had done in regard to selecting a tract of land for me and insisted that it become a part of the treaty and that it should be patented to me directly by the government without any restrictions. Many other questions were debated at this session but no definite agreements were reached and the council was adjourned in the middle of the afternoon. Chief Buffalo asking for the adjournment that he might talk over some matters further with his people, and that night the subject of providing homes for their half-breed relations who lived in different parts of the country was brought up and discussed and all were in favor of making such a provision in the treaty. I proposed to them that as we had made provisions for ourselves and children it would be only fair that an arrangement should be made in the treaty whereby the government should provide for our mixed blood relations by giving to each person the head of a family or to each single person twenty-one years of age a piece of land containing at least eighty acres which would provide homes for those now living and in the future there would be ample room on the reservations for their children, where all could live happily together. We also asked that all teachers and traders in the ceded territory who at that time were located there by license and doing business by authority of law, should each be entitled to 160 acres of land at $1.25 per acre. This was all reduced to writing and when the council met next morning we were prepared to submit all our plans and requests to the commissioners save one, which we required more time to consider. Most of this day was consumed in speech-making by the chiefs and commissioners and in the last speech of the day, which was made by Mr. Gilbert, he said:

“We have talked a great deal and evidently understand one another. You have told us what you want, and now we want time to consider your requests, while you want time as you say to consider another matter, and so we will adjourn until tomorrow and we, with your father. Col. Manypenny, will carefully examine and consider your propositions and when we meet to-morrow we will be prepared to answer you with an approval or rejection.”

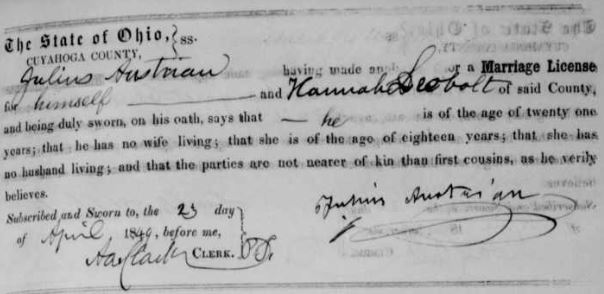

Julius Austrian purchased the village of La Pointe and other interests from the American Fur Company in 1853. He entered his Town Plan of La Pointe on August 29th of 1854. He was the highest paid claimant of the 1854 Treaty at La Pointe. His family hosted the 1855 Annuity Payments at La Pointe.

~ Photograph of Austrian from the Madeline Island Museum

That evening the chiefs considered the other matter, which was to provide for the payment of the debts of the Indians owing the American Fur Company and other traders and agreed that the entire debt could not be more than $90,000 and that that amount should be taken from the Indians in bulk and divided up among their creditors in a pro-rata manner according to the amount due to any person or firm, and that this should wipe out their indebtedness. The American Fur Company had filed claims which, in the aggregate, amounted to two or three times this sum and were at the council heavily armed for the purpose of enforcing their claim by intimidation. This and the next day were spent in speeches pro and con but nothing was effected toward a final settlement.

Col. Manypenny came to my store and we had a long private interview relating to the treaty then under consideration and he thought that the demands of the Indians were reasonable and just and that they would be accepted by the commissioners. He also gave me considerable credit for the manner in which I had conducted the matter for Indians, considering the terrible opposition I had to contend with. He said he had claims in his possession which had been filed by the traders that amounted to a large sum but did not state the amount. As he saw the Indians had every confidence in me and their demands were reasonable he could see no reason why the treaty could not be speedily brought to a close. He then asked if I kept a set of books. I told him I only kept a day book or blotter showing the amount each Indian owed me. I got the books and told him to take them along with him and that he or his interpreter might question any Indian whose name appeared thereon as being indebted to me and I would accept whatever that Indian said he owed me whether it be one dollar or ten cents. He said he would be pleased to take the books along and I wrapped them up and went with him to his office, where I left them. He said he was certain that some traders were making claims for far more than was due them. Messrs. Gilbert and Herriman and their chief clerk, Mr. Smith, were present when Mr. Manypenny related the talk he had with me at the store. He considered the requests of the Indians fair and just, he said, and he hoped there would be no further delays in concluding the treaty and if it was drawn up and signed with the stipulations and agreements that were now understood should be incorporated in it, he would strongly recommend its ratification by the President and senate.

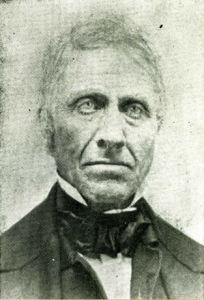

Naagaanab of Fond Du Lac

~ Minnesota Historical Society

The day following the council was opened by a speech from Chief Na-gon-ab in which he cited considerable history.

“My friends,” he said, “I have been chosen by our chief, Buffalo, to speak to you. Our wishes are now on paper before you. Before this it was not so. We have been many times deceived. We had no one to look out for us. The great father’s officers made marks on paper with black liquor and quill. The Indian can not do this. We depend upon our memory. We have nothing else to look to. We talk often together and keep your words clear in our minds. When you talk we all listen, then we talk it over many times. In this way it is always fresh with us. This is the way we must keep our record. In 1837 we were asked to sell our timber and minerals. In 1842 we were asked to do the same. Our white brothers told us the great father did not want the land. We should keep it to hunt on. Bye and bye we were told to go away; to go and leave our friends that were buried yesterday. Then we asked each other what it meant. Does the great father tell the truth? Does he keep his promises? We cannot help ourselves! We try to do as we agree in treaty. We ask you what this means? You do not tell from memory! You go to your black marks and say this is what those men put down; this is what they said when they made the treaty. The men we talk with don’t come back; they do not come and you tell us they did not tell us so! We ask you where they are? You say you do not know or that they are dead and gone. This is what they told you; this is what they done. Now we have a friend who can make black marks on paper When the council is over he will tell us what we have done. We know now what we are doing! If we get what we ask our chiefs will touch the pen, but if not we will not touch it. I am told by our chief to tell you this: We will not touch the pen unless our friend says the paper is all right.”

Na-gon-ab was answered by Commissioner Gilbert, saying:

“You have submitted through your friend and interpreter the terms and conditions upon which you will cede away your lands. We have not had time to give them all consideration and want a little more time as we did not know last night what your last proposition would be. Your father. Col. Manypenny, has ordered some beef cattle killed and a supply of provisions will be issued to you right away. You can now return to your lodges and get a good dinner and talk matters over among yourselves the remainder of the day and I hope you will come back tomorrow feeling good natured and happy, for your father, Col. Manypenny, will have something to say to you and will have a paper which your friend can read and explain to you.”

When the council met next day in front of the commissioners’ office to hear what Col. Manypenny had to say a general good feeling prevailed and a hand-shaking all round preceded the council, which Col. Manypenny opened by saying:

“My friends and children: I am glad to see you all this morning looking good natured and happy and as if you could sit here and listen to what I have to say. We have a paper here for your friend to examine to see if it meets your approval. Myself and the commissioners which your great father has sent here have duly considered all your requests and have concluded to accept them. As the season is passing away and we are all anxious to go to our families and you to your homes, I hope when you read this treaty you will find it as you expect to and according to the understandings we have had during the council. Now your friend may examine the paper and while he is doing so we will take a recess until afternoon.”

Chief Buffalo, turning to me, said:

“My son, we, the chiefs of all the country, have placed this matter entirely in your hands. Go and examine the paper and if it suits you it will suit us.”

Then turning to the chiefs, he asked,

“what do you all say to that?”

The ho-ho that followed showed the entire circle were satisfied.

I went carefully through the treaty as it had been prepared and with a few exceptions found it was right. I called the attention of the commissioners to certain parts of the stipulations that were incorrect and they directed the clerk to make the changes.

The following day the Indians told the commissioners that as their friend had made objections to the treaty as it was they requested that I might again examine it before proceeding further with the council. On this examination I found that changes had been made but on sheets of paper not attached to the body of the instrument, and as these sheets contained some of the most important items in the treaty, I again objected and told the commissioners that I would not allow the Indians to sign it in that shape and not until the whole treaty was re-written and the detached portions appeared in their proper places. I walked out and told the Indians that the treaty was not yet ready to sign and they gave up all further endeavors until next day. I met the commissioners alone in their office that afternoon and explained the objectionable points in the treaty and told them the Indians were already to sign as soon as those objections were removed. They were soon at work putting the instrument in shape.

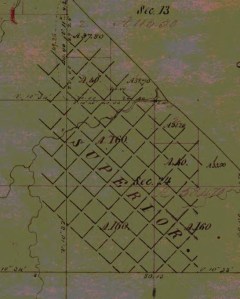

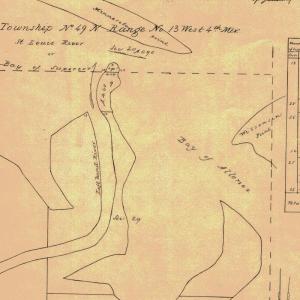

“One version of the boundaries for Chief Buffalo’s reservation is shown at the base of Minnesota Point in a detail from an 1857 map preserved in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Other maps show a larger and more irregularly shaped versions of the reservation boundary, though centered on the same area.”

~ DuluthStories.net

The next day when the Indians assembled they were told by the commissioners that all was ready and the treaty was laid upon a table and I found it just as the Indians had wanted it to be, except the description of the mile square. The part relating to the mile square that was to have been reserved for me read as follows:

“Chief Buffalo, being desirous of providing for some of his relatives who had rendered them important services, it is agreed that he may select one mile square of the ceded territory heretofore described.”

“Now,” said the commissioner,

“we want Buffalo to designate the person or persons to whom he wishes the patents to issue.”

Buffalo then said:

“I want them to be made out in the name of my adopted son.”

This closed all ceremony and the treaty was duly signed on the 30th day of September, 1854. This done the commissioners took a farewell shake of the hand with all the chiefs, hoping to meet them again at the annuity payment the coming year. They then boarded the steamer North Star for home. In the course of a few days the Indians also disappeared, some to their interior homes and some to their winter hunting grounds and a general quiet prevailed on the island.