1837 Petitions from La Pointe to the President

January 29, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs:

La Pointe Agency 1831-1839

National Archives Identifier: 164009310

O. I. A. La Pointe J171.

Hon Geo. W. Jones

Ho. of Reps. Jany 9, 1838

Transmits petition dated 31st Augt 1837, from Michel Cadotte & 25 other Chip. Half Breeds, praying that the amt to be paid them, under the late Chip. treaty, be distributed at La Pointe, and submitting the names of D. P. Bushnell, Lyman M. Warren, for the appt of Comsr to make the distribution.

Transmits it, that it may receive such attention as will secure the objects of the petitioners, says as the treaty has not been satisfied it may be necessary to bring the subject of the petition before the Comsr Ind Affrs of the Senate.

Recd 10 Jany 1838

file

[?] File.

House of Representatives Jany 9th 1838

Sir

I hasten to transmit the inclosed petition, with the hope, that the subject alluded to, may receive such attention, as to secure the object of the petitioners. As the Chippewa Treaty has not yet been ratified it may be necessary to bring the subject of the petition before the Committee of Indian Affairs of the Senate.

I am very respectfully

Your obt svt

Geo W. Jones

C. A. Harris Esqr

Comssr of Indian Affairs

War Department

To the President of the United States of America

The humble petition of the undersigned Chippewa Half-Breeds citizens of the United Sates, respectfully Shareth:

Bizhiki (Buffalo), Dagwagaane (Two Lodges Meet), and Jechiikwii’o (Snipe, aka Little Buffalo) signed the 1837 Treaty of St Peters for the La Pointe Band.

That, your petitioners having lately heard that a Treaty had been concluded between the Government of the United Sates and the Chippewa Indians at St Peters, for the cession of certain lands belonging to that tribe:

ARTICLE 3.

“The sum of one hundred thousand dollars shall be paid by the United States, to the half-

breeds of the Chippewa nation, under the direction of the President. It is the wish of the

Indians that their two sub-agents Daniel P. Bushnell, and Miles M. Vineyard, superintend

the distribution of this money among their half-breed relations.”

That, the said Chippewa Indians X, having a just regard to the interest and welfare of their Half Breed brethren, did there and then stipulate; that, a certain sum of money should be paid once for all unto the said Half-Breeds, to satisfy all claim they might have on the lands so ceded to the United States.

That, your petitioners are ignorant of the time and place where such payment is to be made.

That the great majority of the Half-Breeds entitled to a distribution of said sum of money, are either residing at La Pointe on Lake Superior, or being for the most part earning their livelihood from the Traders, are consequently congregated during the summer months at the aforesaid place.

Your petitioners humbly solicit their father the President, to take their case into consideration, and not subject them to a long and costly journey in ordering the payments to be made at any inconvenient distance, but on the contrary they trust that in his wisdom he will see the justice of their demand in requiring he will be pleased to order the same to be distributed at Lapointe agreeable to their request.

Your petitioners would also intimate that, although they are fully aware that the Executive will make a judicious choice in the appointment of the Commissioners who will be selected to carry into effect the Provisions of said Treaty, yet, they would humbly submit to the President, that they have full confidence in the integrity of D. P. Bushnell Esqr. resident Indian Agent for the United States at this place and Lyman M Warren Esquire, Merchant.

Your petitioners entertain the flattering hope, that, their petition will not be made in vain, and as in duty bound will ever pray.

La Pointe, Lake Superior,

Territory of Wisconsin 31st August 1837

Michel Cadotte

Michel Bosquet X his mark

Seraphim Lacombe X his mark

Joseph Cadotte X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Chs W Borup for wife & Children

A Morrison for wife & children

Pierre Cotte

Henry Cotte X his mark

Frances Roussan X his mark

James Ermatinger for wife & family

Lyman M Warren for wife & family

Joseph Dufault X his mark

Paul Rivet X his mark for wife & family

Charles Chaboullez wife & family

George D. Cameron

Alixis Corbin

Louis Corbin

Jean Bste Denomme X his mark and family

Ambrose Deragon X his mark and family

Robert Morran X his mark ” “

Jean Bst Couvillon X his mark ” “

Alix Neveu X his mark ” “

Frances Roy X his mark ” “

Alixis Brisbant X his mark ” “

Signed in presence of G. Pauchene

John Livingston

O.I.A. La Pointe W424.

Governor of Wisconsin

Mineral Pt. Feby 19, 1838

Transmits the talk of “Buffalo,” a Chip. Chief, delivered at the La Pointe SubAgt, Dec. 9, 1837, asking that the am. due the half-breeds under the late Treaty, be divided fairly among them, & paid them there, as they will not go to St Peters for it, &c.

Says Buffalo has great influence with his tribe, & is friendly to the whites; his sentiments accord with most of those of the half-breeds & Inds in that part of the country.

File

Recd 13 March 1838

[?] File.

Superintendency of Indian Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point, Feby 19, 1838

Sir,

I have the honor to inclose the talk of “Buffalo,” a principal chief of the Chippewa Indians in the vicinity of La Pointe, delivered on the 9th Dec’r last before Mr Bushnell, sub-agent of the Chippewas at that place. Mr. Bushnell remarks that the speech is given with as strict an adherence to the letter as the language will admit, and has no doubt the sentiments expressed by this Chief accord with those of most of the half-breeds and Indians in that place of the Country. The “Buffalo” is a man of great influence among his tribe, and very friendly to the whites.

Very respectfully,

Your obed’t sevt.

Henry Dodge

Supt Ind Affs

Hon C. A. Harris

Com. of Ind. Affairs

Subagency

Lapointe Dec 10 1837

Speech of the Buffalo principal Chief at Lapointe

Father I told you yesterday I would have something to say to you today. What I say to you now I want you to write down, and send it to the Great American Chief that we saw at St Peters last summer, (Gov. Dodge). Yesterday, I called all the Indians together, and have brought them here to hear what I say; I speak the words of all.

ARTICLE 1.

“The said Chippewa nation cede to the United States all that tract of country included

within the following boundaries:

[…]

thence to and along the dividing ridge between the waters of Lake Superior and those of the Mississippi

[…]“

Father it was not my voice, that sold the country last summer. The land was not mine; it belonged to the Indians beyond the mountains. When our Great Father told us at St Peters that it was only the country beyond the mountains that he wanted I was glad. I have nothing to say about the Treaty, good, or bad, because the country was not mine; but when it comes my time I shall know how to act. If the Americans want my land, I shall know what to say. I did not like to stand in the road of the Indians at St Peters. I listened to our Great Father’s words, & said them in my heart. I have not forgotten them. The Indians acted like children; they tried to cheat each other and got cheated themselves. When it comes my time to sell my land, I do not think I shall give it up as they did.

What I say about the payment I do not say on my own account; for myself I do not care; I have always been poor, & don’t want silver now. But I speak for the poor half breeds.

There are a great many of them; more than would fill your house; some of them are very poor They cannot go to St Peters for their money. Our Great Father told us at St Peters, that you would divide the money, among the half breeds. You must not mind those that are far off, but divide it fairly, and give the poor women and children a good share.

Father the Indians all say they will not go to St Peters for their money. Let them divide it in this parts if they choose, but one must have ones here. You must not think you see all your children here; there are so many of them, that when the money and goods are divided, there will not be more than half a Dollar and a breech cloth for each one. At Red Cedar Lake the English Trader (W. Aitken) told the Indians they would not have more than a breech cloth; this set them to thinking. They immediately held a council & their Indian that had the paper (The Treaty) said he would not keep it, and would send it back.

It will not be my place to come in among the first when the money is paid. If the Indians that own the land call me in I shall come in with pleasure.

ARTICLE 4.

“The sum of seventy thousand dollars shall be applied to the payment, by the United States, of certain claims against the Indians; of which amount twenty eight thousand dollars shall, at their request, be paid to William A. Aitkin, twenty five thousand to Lyman M. Warren, and the balance applied to the liquidation of other just demands against them—which they acknowledge to be the case with regard to that presented by Hercules L. Dousman, for the sum of five thousand dollars; and they request that it be paid.“

We are afraid of one Trader. When at St Peters I saw that they worked out only for themselves. They have deceived us often. Our Great Father told us he would pay our old debts. I thought they should be struck off, but we have to pay them. When I heard our debts would be paid, it done my heart good. I was glad; but when I got back here my joy was gone. When our money comes here, I hope our Traders will keep away, and let us arrange our own business, with the officers that the President sends here.

Father I speak for my people, not for myself. I am an old man. My fire is almost out – there is but little smoke. When I set in my wigwam & smoke my pipe, I think of what has past and what is to come, and it makes my heart shake. When business comes before us we will try and act like chiefs. If any thing is to be done, it had better be done straight. The Indians are not like white people; they act very often like children. We have always been good friends to the whites, and we want to remain so. We do not [even?] go to war with our enemies, the Sioux; I tell my young men to keep quiet.

Father I heard the words of our Great Father (Gov. Dodge) last summer, and was pleased; I have not forgotten what he said. I have his words up in my heart. I want you to tell him to keep good courage for us, we want him to do all he can for us. What I have said you have written down; I [?] you to hand him a copy; we don’t know your ways. If I [?] said any thing [?] dont send it. If you think of any thing I ought to say send it. I have always listened to the white men.

O.I.A. Lapointe, B.458

D. P. Bushnell

Lapointe, March 8, 1838

At the request of some of the petitioners, encloses a petition dated 7 March 1838, addressed to the Prest, signed by 167 Chip. half breeds, praying that the amt stipulated by the late Chip. Treaty to be paid to the half breeds, to satisfy all claims they ma have on the lands ceded by this Treaty, may be distributed at Lapointe.

Hopes their request will be complied with; & thinks their annuity should likewise be paid at Lapointe.

File

Recd 2nd May, 1838

Subagency

Lapointe Mch 6 1838

Sir

I have the honor herewith to enclose a petition addressed to the President of the United States, handed to me with a request by several of the petitioners that I would forward it. The justice of the demand of these poor people is so obvious to any one acquainted with their circumstances, that I cannot omit this occasion to second it, and to express a sincere hope that it will be complied with. Indeed, if the convenience and wishes of the Indians are consulted, and as the sum they receive for their country is so small, these should, I conciev, be principle considerations, their annuity will likewise as paid here; for it is a point more convenient of access for the different bands, that almost any other in their own country, and one moreover, where they have interests been in the habit of assembling in the summer months.

I am sir, with great respect,

your most obt servant,

D. P. Bushnell

O. I. A.

C. A. Harris Esqr.

Comr Ind. Affs

To the President of the United States of America

The humble petition of the undersigned Chippewa Half-Breeds citizens of the United States respectfully shareth

That your petitioners having lately heard, that a Treaty has been concluded between the Government of the United States and the Chippewa Indians at St Peters for the cession of certain lands belonging to that tribe;

That the said Chippewa Indians having a just regard to the interest and wellfare of their Half-Breed brethern, did there and then stipulate, that a certain sum of money should be paid once for all unto the said Half-Breeds, to satisfy all claims, they might have on the lands so ceded to the United States;

That your petitioners are ignorant of the time and place, where such payment is to be made; and

That the great majority of the Half-Breeds entitled to a portion of said sum of money are either residing at Lapointe on Lake Superior, or being for the most part earning their livelihood from the Traders, are consequently congregated during the summer months at the aforesaid place;

Your petitioners therefore humbly solicit their Father the President to take their case into consideration, and not subject them to a long and costly journey on ordering the payment to be made at any convenient distance, but on the contrary, they wish, that in his wisdom he will see the justice of this petition and that he will be pleased to order the same to be distributed at Lapointe agreeably to their request.

Your petitioners entertain the flattering hope, that their petition will not be made in vain and as in duly bound will ever pray.

Half Breeds of Folleavoine Lapointe Lac Court Oreilles and Lac du Flambeau

Georg Warren

Edward Warren

William Warren

Truman A Warren

Mary Warren

Michel Cadott

Joseph Cadotte

Joseph Dufault

Frances Piquette X his mark

Michel Bousquet X his mark

Baptiste Bousquet X his mark

Jos Piquette X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Cadotte X his mark

Seraphim Lacombre X his mark

Angelique Larose X her mark

Benjamin Cadotte X his mark

J Bte Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Danis X his mark

Henry Brisette X his mark

Charles Brisette X his mark

Jehudah Ermatinger

William Ermatinger

Charlotte Ermatinger

Larence Ermatinger

Theodore Borup

Sophia Borup

Elisabeth Borup

Jean Bte Duchene X his mark

Agathe Cadotte X her mark

Mary Cadotte X her mark

Charles Cadotte X his mark

Louis Nolin _ his mark

Frances Baillerge X his mark

Joseph Marchand X his mark

Louis Dubay X his mark

Alexis Corbin X his mark

Augustus Goslin X his mark

George Cameron X his mark

Sophia Dufault X her mark

Augt Cadotte No 2 X his mark

Jos Mace _ his mark

Frances Lamoureau X his mark

Charles Morrison

Charlotte L. Morrison

Mary A Morrison

Margerike Morrison

Jane Morrison

Julie Dufault X her mark

Michel Dufault X his mark

Jean Bte Denomme X his mark

Michel Deragon X his mark

Mary Neveu X her mark

Alexis Neveu X his mark

Michel Neveu X his mark

Josette St Jean X her mark

Baptist St Jean X his mark

Mary Lepessier X her mark

Edward Lepessier X his mark

William Dingley X his mark

Sarah Dingley X her mark

John Hotley X his mark

Jeannette Hotley X her mark

Seraphim Lacombre Jun X his mark

Angelique Lacombre X her mark

Felicia Brisette X her mark

Frances Houle X his mark

Jean Bte Brunelle X his mark

Jos Gauthier X his mark

Edward Connor X his mark

Henry Blanchford X his mark

Louis Corbin X his mark

Augustin Cadotte X his mark

Frances Gauthier X his mark

Jean Bte Gauthier X his mark

Alexis Carpentier X his mark

Jean Bte Houle X his mark

Frances Lamieux X his mark

Baptiste Lemieux X his mark

Pierre Lamieux X his mark

Michel Morringer X his mark

Frances Dejaddon X his mark

John Morrison X his mark

Eustache Roussain X his mark

Benjn Morin X his mark

Adolphe Nolin X his mark

Half-Breeds of Fond du Lac

John Aitken

Roger Aitken

Matilda Aitken

Harriet Aitken

Nancy Scott

Robert Fairbanks

George Fairbanks

Jean B Landrie

Joseph Larose

Paul Bellanges X his mark

Jack Belcour X his mark

Jean Belcour X his mark

Paul Beauvier X his mark

Frances Belleaire

Michel Comptois X his mark

Joseph Charette X his mark

Chl Charette X his mark

Jos Roussain X his mark

Pierre Roy X his mark

Joseph Roy X his mark

Vincent Roy X his mark

Jack Bonga X his mark

Jos Morrison X his mark

Henry Cotte X his mark

Charles Chaboillez

Roderic Chaboillez

Louison Rivet X his mark

Louis Dufault X his mark

Louison Dufault X his mark

Baptiste Dufault X his mark

Joseph Dufault X his mark

Chs Chaloux X his mark

Jos Chaloux X his mark

Augt Bellanger X his mark

Bapt Bellanger X his mark

Joseph Bellanger X his mark

Ignace Robidoux X his mark

Charles Robidoux X his mark

Mary Robidoux X her mark

Simon Janvier X his mark

Frances Janvier X his mark

Baptiste Janvier X his mark

Frances Roussain X his mark

Therese Rouleau X his mark

Joseph Lavierire X his mark

Susan Lapointe X her mark

Mary Lapointe X her mark

Louis Gordon X his mark

Antoine Gordon X his mark

Jean Bte Goslin X his mark

Nancy Goslin X her mark

Michel Petit X his mark

Jack Petit X his mark

Mary Petit X her mark

Josette Cournoyer X her mark

Angelique Cournoyer X her mark

Susan Cournoyer X her mark

Jean Bte Roy X his mark

Frances Roy X his mark

Baptist Roy X his mark

Therese Roy X her mark

Mary Lavierge X her mark

Toussaint Piquette X his mark

Josette Piquette X her mark

Susan Montreille X her mark

Josiah Bissel X his mark

John Cotte X his mark

Isabelle Cotte X her mark

Angelique Brebant X her mark

Mary Brebant X her mark

Margareth Bell X her mark

Julie Brebant X her mark

Josette Lefebre X her mark

Sophia Roussain X her mark

Joseph Roussain X his mark

Angelique Roussain X her mark

Joseph Bellair X his mark

Catharine McDonald X her mark

Nancy McDonald X her mark

Mary Macdonald X her mark

Louise Landrie X his mark

In presence of

Chs W Borup

A Morrison

A. D. Newton

Lapointe 7th March 1838

1827 Deed for Old La Pointe

December 27, 2022

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Chief Buffalo and other principal men for the La Pointe Bands of Lake Superior Chippewa began signing treaties with the United States at the 1825 Treaty of Prairie Du Chien; followed by the 1826 Treaty of Fond Du Lac, which reserved Tribal Trust Lands for Chippewa Mixed Bloods along the St. Mary’s River between Lake Superior and Lake Huron:

ARTICLE 4.

The Indian Trade & Intercourse Act of 1790 was the United States of America’s first law regulating tribal land interests:

SEC. 4. And be it enacted and declared, That no sale of lands made by any Indians, or any nation or tribe of Indians the United States, shall be valid to any person or persons, or to any state, whether having the right of pre-emption to such lands or not, unless the same shall be made and duly executed at some public treaty, held under the authority of the United States.

It being deemed important that the half-breeds, scattered through this extensive country, should be stimulated to exertion and improvement by the possession of permanent property and fixed residences, the Chippewa tribe, in consideration of the affection they bear to these persons, and of the interest which they feel in their welfare, grant to each of the persons described in the schedule hereunto annexed, being half-breeds and Chippewas by descent, and it being understood that the schedule includes all of this description who are attached to the Government of the United States, six hundred and forty acres of land, to be located, under the direction of the President of the United States, upon the islands and shore of the St. Mary’s river, wherever good land enough for this purpose can be found; and as soon as such locations are made, the jurisdiction and soil thereof are hereby ceded. It is the intention of the parties, that, where circumstances will permit, the grants be surveyed in the ancient French manner, bounding not less than six arpens, nor more than ten, upon the river, and running back for quantity; and that where this cannot be done, such grants be surveyed in any manner the President may direct. The locations for Oshauguscodaywayqua and her descendents shall be adjoining the lower part of the military reservation, and upon the head of Sugar Island. The persons to whom grants are made shall not have the privilege of conveying the same, without the permission of the President.

The aforementioned Schedule annexed to the 1826 Treaty of Fond du Lac included (among other Chippewa Mixed Blood families at La Pointe) the families of Madeline & Michel Cadotte, Sr. and their American son-in-laws, the brothers Truman A. Warren and Lyman M. Warren:

-

To Michael Cadotte, senior, son of Equawaice, one section.

-

To Equaysay way, wife of Michael Cadotte, senior, and to each of her children living within the United States, one section.

-

To each of the children of Charlotte Warren, widow of the late Truman A. Warren, one section.

-

To Ossinahjeeunoqua, wife of Michael Cadotte, Jr. and each of her children, one section.

-

To each of the children of Ugwudaushee, by the late Truman A. Warren, one section.

-

To William Warren, son of Lyman M. Warren, and Mary Cadotte, one section.

Detail of Michilimackinac County circa 1818 from Michigan as a territory 1805-1837 by C.A. Burkhart, 1926.

~ UW-Milwaukee Libraries

Now, if it seems odd for a Treaty in Minnesota (Fond du Lac) to give families in Wisconsin (La Pointe) lots of land in Michigan (Sault Ste Marie), just remember that these places were relatively ‘close’ to each other in the sociopolitical fabric of Michigan Territory back in 1827. All three places were in Michilimackinac County (seated at Michilimackinac) until 1826, when they were carved off together as part of the newly formed Chippewa County (seated at Sault Ste Marie). Lake Superior remained Unceded Territory until later decades when land cessions were negotiated in the 1836, 1837, 1842, and 1854 Treaties.

Ultimately, the United States removed the aforementioned Schedule from the 1826 Treaty before ratification in 1827.

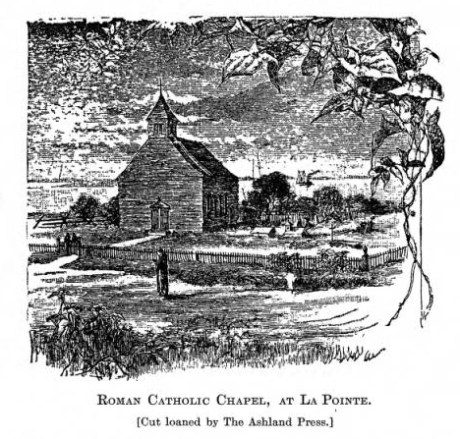

Several months later, at Michilimackinac, Madeline & Michel Cadotte, Sr. recorded the following Deed to reserve 2,000 acres surrounding the old French Forts of La Pointe to benefit future generations of their family.

Register of Deeds

Michilimackinac County

Book A of Deeds, Pages 221-224

Michel Cadotte and

Magdalen Cadotte

to

Lyman M. Warren

~Deed.

Received for Record

July 26th 1827 at two Six O’Clock A.M.

J.P. King

Reg’r Probate

Bizhiki (Buffalo), Gimiwan (Rain), Kaubuzoway, Wyauweenind, and Bikwaakodowaanzige (Ball of Dye) signed the 1826 Treaty of Fond Du Lac as the Chief and principal men of La Pointe.

“Copy of 1834 map of La Pointe by Lyman M. Warren“ at Wisconsin Historical Society. Original map (not shown here) is in the American Fur Company papers of the New York Historical Society.

Whereas the Chief and principal men of the Chippeway Tribe of indians, residing on and in the parts adjacent to the island called Magdalen in the western part of Lake Superior, heretofore released and confirmed by Deed unto Magdalen Cadotte a Chippeway of the said tribe, and to her brothers and sisters as tenants in common, thereon, all that part of the said Island called Magdalen, lying south and west of a line commencing on the eastern shore of said Island in the outlet of Great Wing river, and running directly thence westerly to the centre of Sandy bay on the western side of said Island;

and whereas the said brothers and sisters of said Magdalen Cadotte being tenants in common of the said premises, thereafterwards, heretofore, released, conveyed and confirmed unto their sister, the said Magdalen Cadotte all their respective rights title, interest and claim in and to said premises,

and whereas the said Magdalen Cadotte is desirous of securing a portion of said premises to her five grand children viz; George Warren, Edward Warren and Nancy Warren children of her daughter Charlotte Warren, by Truman A. Warren late a trader at said island, deceased, and William Warren and Truman A. Warren children of her daughter Mary Warren by Lyman M. Warren now a trader at said Island;

and whereas the said Magdalen Cadotte is desirous to promote the establishment of a mission on said Island, by and under the direction, patronage and government of the American board of commissioners for foreign missions, according to the plan, wages, and principles and purposes of the said Board.

William Whipple Warren was one of the beneficiary grandchildren named in this Deed.

Now therefore, Know all men by these presents that we Michael Cadotte and Magdalen Cadotte, wife of the said Michael, of said Magdalen Island, in Lake Superior, for and in consideration of one dollar to us in hand paid by Lyman M. Warren, the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged, and for and in consideration of the natural love and affection we bear to our Grandchildren, the said George, Edward, Nancy, William W., and Truman A. Warren, children of our said daughters Charlotte and Mary;

and the further consideration of our great desire to promote the establishment of a mission as aforesaid, under and by the direction, government and patronage of Board aforesaid, have granted, bargained, sold, released, conveyed and confirmed, and by these presents do grant, bargain, sell, release, convey and confirm unto the said Lyman M. Warren his heirs and assigns, out of the aforerecited premises and as part and parcel thereof a certain tract of land on Magdalen Island in Lake Superior, bounded as follows,

Detail of Ojibwemowin placenames on GLIFWC’s webmap.

that is to say, beginning at the most southeasterly corner of the house built and now occupied by said Lyman M. Warren, on the south shore of said Island between this tract and the land of the grantor, thence on the east by a line drawn northerly until it shall intersect at right angles a line drawn westerly from the mouth of Great Wing River to the Centre of Sandy Bay, thence on the north by the last mentioned line westward to a Point in said line, from which a line drawn southward and at right angles therewith would fall on the site of the old fort, so called on the southerly side of said Island; thence on the west by a line drawn from said point and parallel to the eastern boundary of said tract, to the Site of the old fort, so called, thence by the course of the Shore of old Fort Bay to the portage; thence by a line drawn eastwardly to the place of beginning, containing by estimation two thousand acres, be the same more or less, with the appurtenances, hereditaments, and privileges thereto belonging.

To have and to hold the said granted premises to him the said Lyman M. Warren his heirs and assigns: In Trust, Nevertheless, and upon this express condition, that whensoever the said American Board of Commissioners for foreign missions shall establish a mission on said premises, upon the plan, usages, principles and purposes as aforesaid, the said Lyman M. Warren shall forthwith convey unto the american board of commissioners for foreign missions, not less than one quarter nor more than one half of said tract herein conveyed to him, and to be divided by a line drawn from a point in the southern shore of said Island, northerly and parallel with the east line of said tract, and until it intersects the north line thereof.

And as to the residue of the said Estate, the said Lyman M. Warren shall divided the same equally with and amongst the said five children, as tenants in common, and not as joint tenants; and the grantors hereby authorize the said Lyman M. Warren with full powers to fulfil said trust herein created, hereby ratifying and confirming the deed and deeds of said premises he may make for the purpose ~~~

In witness whereof we have hereunto set our respective hands, this twenty fifth day of july A.D. one thousand eight hundred and twenty seven, of Independence the fifty first.

(Signed) Michel Cadotte {Seal}

Magdalen Cadotte X her mark {Seal}

Signed, Sealed and delivered

in presence of us }

Daniel Dingley

Samuel Ashman

Wm. M. Ferry

(on the third page and ninth line from the top the word eastwardly was interlined and from that word the three following lines and part of the fourth to the words “to the place” were erased before the signing & witnessing of this instrument.)

~~~~~~

Territory of Michigan }

County of Michilimackinac }

Be it known that on the twenty sixth day of July A.D. 1827, personally came before me, the subscriber, one of the Justices of the Peace for the County of Michilimackinac, Michel Cadotte and Magdalen Cadotte, wife of the said Michel Cadotte, and the said Magdalen being examined separate and apart from her said husband, each severally acknowledged the foregoing instrument to be their voluntary act and deed for the uses and purposes therein expressed.

(Signed) J. P. King

Just. peace

Cxd

fees Paid $2.25

“Considerable Altercation Ensued”

March 11, 2017

By Leo

Here is another gem from Wheeler. It appears to be a short description of a meeting in Odanah that quickly devolves into absurdity. It appears without any associated documents in the chronological professional papers of the Wheeler Family Collection at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center. For what it lacks in length and context, it makes up for in insight into the personalities of some prominent Chequamegon residents.

Odanah July 6, 1856

Council of Indians called by Mr Warren to make regulations in regard to the partitions of Domestic Arrivals & crops here. Mr S. C. Collins was appointed chairman & L. H. Wheeler Secretary.

Mr Warren presented some resolutions stating the object of the meeting , which was interpreted to the Indians.

After reading the paper Mr. Warren added remarks explaining the importance of some such regulations for the good of both the Whites & Indians.

After he stopped Blackbird spoke. The substance of his remarks was that the commissioner & agent told him to be still and do nothing till the agent should come, and therefore he should have nothing to do with what was proposed to them.

Out of contempt to Mr Warren he proposed that he should be made chief. He said it was treating them like children for Mr W to pass laws & rules for them to observe, just as though they were not able to take care of their own interests. He was asked more fully Mr Stoddard regarding the concluding remarks of Black Bird in substance, as a motion, to drop the whole subject, seconded the motion upon which considerable altercation ensued. The result of which was that the question should be considered still open for discussion and free remarks be allowed on both sides.

Odanah in 1856, just two years removed from the Treaty of 1854, was a community in flux. The cities of Ashland and Bayfield were growing rapidly with white American settlers. Being the largest of the newly-created reservations, Bad River was also growing as some of the Ojibwe bands from the Island, Ontonagon, St. Croix and the Chippewa River relocated there. In contrast to the Buffalo Bay (Red Cliff) reservation whose population included numerous mix-blood and Catholic families, the people of Bad River were largely full-bloods practicing traditional ways.

A handful of mix-blood and white families did live in Odanah, sponsored by the US Government and eastern missionary societies for Christianizing and “civilizing” the Ojibwe. These included the families of Reverend Leonard H. Wheeler founder of the Odanah mission, Truman A. Warren the government farmer, and John Stoddard the government carpenter. At this point in history, each of these men had lived in or around Odanah for several years and were well-known to area residents.

Truman A. Warren, brother of William W. Warren (Wisconsin Historical Society).

From the document, it appears that Warren called a meeting to create rules for the distribution of crops and goods to the Bad River Band. Warren was born at La Pointe in the mid-1820s to fur-trader Lyman Warren and Marie Cadotte Warren. Most Ojibwe men of the era avoided farming as it was considered women’s work. Warren, however, did not appear to share this view. He was a Christian mix-blood whose grandfather, Michel Cadotte, planted numerous crops on the Island. As a teenager, Truman, spent several years at school in New York learning English and doing farm labor.

Getting the farmer position, which had been created by the Treaty of 1842, was seen as a stroke of good fortune. His sister, Julia Warren Spears later described it as such:

My brother Truman A. Warren was the government farmer for the Indians, who lived at Bad River about 15 miles on the main land from La Pointe. That is where they made there garden and what other farming they did. The government farmer, carpenter, and blacksmith all had good houses to live in and received good salaries. (Spears to Bartlett; October 26, 1924)

Leonard H. Wheeler (Wisconsin Historical Society)

S. C. Collins is listed as the chairman of the meeting. I have been unable to find any other information about his connection to this area. I suspect he may have been a visitor or brief resident enlisted by Leonard Wheeler as a neutral party to conduct the meeting.

The Wheelers and Warrens were very close. Truman’s father was the original force behind bringing the Protestant missions into the area and Leonard and Harriet Wheeler helped raise Truman’s younger sister.

John Stoddard, the government carpenter has been identified by Amorin Mello as the most likely author of the mystery journal found in the Wheeler Collection. He was also close to Wheeler. As was Blackbird, the most prominent chief of the Bad River Ojibwe.

I’ve written before on how Blackbird and Wheeler were an odd couple. Wheeler was dedicated to the destruction of Ojibwe culture while Blackbird was perhaps the strongest advocate for maintaining traditional ways. Even so, the primary sources seem to indicate the men had a strong respect for one another.

Blackbird’s affections for Wheeler, however, don’t appear to extend to Warren. This isn’t overly surprising. Truman, and his deceased brother William, had run counter to the chief’s wishes on multiple occasions. William Warren criticized Blackbird directly at the time of the Martell Delegation. Blackbird also wanted to limit the power of Henry Rice’s “Indian Ring,” which employed numerous La Pointe mix-bloods including the Warrens.

In Theresa Schenck’s excellent William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader, the Warrens occasionally betray a paternalistic attitude toward their Ojibwe relatives. For example, William and Truman both initially supported the tragic Sandy Lake Removal of 1850-51 even though the Ojibwe leadership was rightfully opposed to it. Blackbird, of all the chiefs, seemed the least willing to accept condescension and threats to tribal sovereignty so it’s not surprising that a “considerable altercation ensued.”

For Wheeler’s part, I haven’t found any evidence he tried to force Robert’s Rules of Order on this area again.

Davidson, John N. In Unnamed Wisconsin. N.p.: Nabu, 2010. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star of St. Cloud, 2013. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln, Neb.: U of Nebraska, 2009. Print.

In the Fall of 1850, the Lake Superior Ojibwe (Chippewa) bands were called to receive their annual payments at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi River. The money was compensation for the cession of most of northern Wisconsin, Upper Michigan, and parts of Minnesota in the treaties of 1837 and 1842. Before that, payments had always taken place in summer at La Pointe. That year they were switched to Sandy Lake as part of a government effort to remove the entire nation from Wisconsin and Michigan in blatant disregard of promises made to the Ojibwe just a few years earlier.

There isn’t enough space in this post to detail the entire Sandy Lake Tragedy (I’ll cover more at a later date), but the payments were not made, and 130-150 Ojibwe people, mostly men, died that fall and winter at Sandy Lake. Over 250 more died that December and January, trying to return to their villages without food or money.

George Warren (b.1823) was the son of Truman Warren and Charlotte Cadotte and the cousin of William Warren. (photo source unclear, found on Canku Ota Newsletter)

If you are a regular reader of Chequamegon History, you will recognize the name of William Warren as the writer of History of the Ojibway People. William’s father, Lyman, was an American fur trader at La Pointe. His mother, Mary Cadotte was a member of the influential Ojibwe-French Cadotte family of Madeline Island. William, his siblings, and cousins were prominent in this era as interpreters and guides. They were people who could navigate between the Ojibwe and mix-blood cultures that had been in this area for centuries, and the ever-encroaching Anglo-American culture.

The Warrens have a mixed legacy when it comes to the Sandy Lake Tragedy. They initially supported the removal efforts, and profited from them as government employees, even though removal was completely against the wishes of their Ojibwe relatives. However, one could argue this support for the government came from a misguided sense of humanitarianism. I strongly recommend William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader by Theresa Schenck if you are interested in Warren family and their motivations. The Wisconsin Historical Society has also digitized several Warren family letters, and that’s what prompted this post. I decided to transcribe and analyze two of these letters–one from before the tragedy and one from after it.

The first letter is from Leonard Wheeler, a missionary at Bad River, to William Warren. Initially, I chose to transcribe this one because I wanted to get familiar with Wheeler’s handwriting. The Historical Society has his papers in Ashland, and I’m planning to do some work with them this summer. This letter has historical value beyond handwriting, however. It shows the uncertainty that was in the air prior to the removal. Wheeler doesn’t know whether he will have to move his mission to Minnesota or not, even though it is only a month before the payments are scheduled.

Sept 6, 1850

Dear Friend,

I have time to write you but a few lines, which I do chiefly to fulfill my promise to Hole in the Day’s son. Will you please tell him I and my family are expecting to go Below and visit our friends this winter and return again in the spring. We heard at Sandy Lake, on our way home, that this chief told [Rev.?] Spates that he was expecting a teacher from St. Peters’ if so, the Band will not need another missionary. I was some what surprised that the man could express a desire to have me come and live among his people, and then afterwards tell Rev Spates he was expecting a teacher this fall from St. Peters’. I thought perhaps there was some where a little misunderstanding. Mr Hall and myself are entirely undecided what we shall do next Spring. We shall wait a little and see what are to be the movements of gov. Mary we shall leave with Mr Hall, to go to school during the winter. We think she will have a better opportunity for improvement there, than any where else in the country. We reached our home in safety, and found our families all well. My wife wishes a kind remembrance and joins me in kind regards to your wife, Charlotte and all the members of your family. If Truman is now with you please remember us to him also. Tomorrow we are expecting to go to La Pointe and take the Steam Boat for the Sault monday. I can scarcely realize that nine years have passed away since in company with yourself and Pa[?] Edward[?] we came into the country.

Mary is now well and will probably write you by the bearer of this.

Very truly yours

L. H. Wheeler

By the 1850s, Young Hole in the Day was positioning himself to the government as “head chief of all the Chippewas,” but to the people of this area, he was still Gwiiwiizens (Boy), his famous father’s son. (Minnesota Historical Society)

By the 1850s, Young Hole in the Day was positioning himself to the government as “head chief of all the Chippewas,” but to the people of this area, he was still Gwiiwiizens (Boy), his famous father’s son. (Minnesota Historical Society)Samuel Spates was a missionary at Sandy Lake. Sherman Hall started as a missionary at La Pointe and later moved to Crow Wing.

Mary, Charlotte, and Truman Warren are William’s siblings.

The Wheeler letter is interesting for what it reveals about the position of Protestant missionaries in the 1850s Chequamegon region. From the 1820s onward, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent missionaries, mostly Congregationalists and Presbyterians from New England, to the Lake Superior Country. Their names, Wheeler, Hall, Ely, Boutwell, Ayer, etc. are very familiar to historians, because they produced hundreds of pages of letters and diaries that reveal a great deal about this time period.

Leonard H. Wheeler (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Ojibwe people reacted to these missionaries in different ways. A few were openly hostile, while others were friendly and visited prayer, song, and school meetings. Many more just ignored them or regarded them as a simple nuisance. In forty-plus years, the amount of Ojibwe people converted to Protestantism could be counted on one hand, so in that sense the missions were a spectacular failure. However, they did play a role in colonization as a vanguard for Anglo-American culture in the region. Unlike the traders, who generally married into Ojibwe communities and adapted to local ways to some degree, the missionaries made a point of trying to recreate “civilization in the wilderness.” They brought their wives, their books, and their art with them. Because they were not working for the government or the Fur Company, and because they were highly respected in white-American society, there were times when certain missionaries were able to help the Ojibwe advance their politics. The aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy was such a time for Wheeler.

This letter comes before the tragedy, however, and there are two things I want to point out. First, Wheeler and Sherman Hall don’t know the tragedy is coming. They were aware of the removal, and tentatively supported it on the grounds that it might speed up the assimilation and conversion of the Ojibwe, but they are clearly out of the loop on the government’s plans.

Second, it seems to me that Hole in the Day is giving the missionaries the runaround on purpose. While Wheeler and Spates were not powerful themselves, being hostile to them would not help the Ojibwe argument against the removal. However, most Ojibwe did not really want what the missionaries had to offer. Rather than reject them outright and cause a rift, the chief is confusing them. I say this because this would not be the only instance in the records of Ojibwe people giving ambiguous messages to avoid having their children taken.

Anyway, that’s my guess on what’s going on with the school comment, but you can’t be sure from one letter. Young Hole in the Day was a political genius, and I strongly recommend Anton Treuer’s The Assassination of Hole in the Day if you aren’t familiar with him.

I read this as “passed away since in company with yourself and Pa[?] Edward we came into the country.” Who was Wheeler’s companion when a young William guided him to La Pointe? I intend to find out and fix this quote. (from original in the digital collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society)

In 1851, Warren was in failing health and desperately trying to earn money for his family. He accepted the position of government interpreter and conductor of the removal of the Chippewa River bands. He feels removing is still the best course of action for the Ojibwe, but he has serious doubts about the government’s competence. He hears the desires of the chiefs to meet with the president, and sees the need for a full rice harvest before making the journey to La Pointe. Warren decides to stall at Lac Courte Oreilles until all the Ojibwe bands can unite and act as one, and does not proceed to Lake Superior as ordered by Watrous. The agent is getting very nervous.

Clement and Paul (pictured) Hudon Beaulieu, and Edward Conner, were mix-blooded traders who like the Warrens were capable of navigating Anglo-American culture while maintaining close kin relationships in several Ojibwe communities. Clement Beaulieu and William Warren had been fierce rivals ever since Beaulieu’s faction drove Lyman Warren out of the American Fur Company. (Photo original unknown: uploaded to findadagrave.com by Joan Edmonson)

Clement and Paul (pictured) Hudon Beaulieu, and Edward Conner, were mix-blooded traders who like the Warrens were capable of navigating Anglo-American culture while maintaining close kin relationships in several Ojibwe communities. Clement Beaulieu and William Warren had been fierce rivals ever since Beaulieu’s faction drove Lyman Warren out of the American Fur Company. (Photo original unknown: uploaded to findadagrave.com by Joan Edmonson)For more on Cob-wa-wis (Oshkaabewis) and his Wisconsin River band, see this post.

“Perish” is what I see, but I don’t know who that might be. Is there a “Parrish”, or possibly a “Bineshii” who could have carried Watrous’ letter? I’m on the lookout. (from original in the digital collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society)

Aug 9th 1851

Friend Warren

I am now very anxiously waiting the arrival of yourself and the Indians that are embraced in your division to come out to this place.

Mr. C. H. Beaulieu has arrived from the Lake Du Flambeau with nearly all that quarter and by an express sent on in advance I am informed that P. H. Beaulieu and Edward Conner will be here with Cob-wa-wis and they say the entire Wisconsin band, there had some 32 of the Pillican Lake band come out and some now are in Conner’s Party.

I want you should be here without fail in 10 days from this as I cannot remain longer, I shall leave at the expiration of this time for Crow Wing to make the payment to the St. Croix Bands who have all removed as I learn from letters just received from the St. Croix. I want your assistance very much in making the Crow Wing payment and immediately after the completion of this, (which will not take over two days[)] shall proceed to Sandy Lake to make the payment to the Mississippi and Lake Bands.

The goods are all at Sandy Lake and I shall make the entire payment without delay, and as much dispatch as can be made it; will be quite lots enough for the poor Indians. Perish[?] is the bearer of this and he can tell you all my plans better then I can write them. give My respects to your cousin George and beli[e]ve me

Your friend

J. S. Watrous

W. W. Warren Esq.}

P. S. Inform the Indians that if they are not here by the time they will be struck from the roll. I am daily expecting a company of Infantry to be stationed at this place.

JSW

![Group of people, including a number of Ojibwe at Minnesota Point, Duluth, Minnesota [featuring William Howenstein] ~ University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/howenstein-minnesota-point.jpg?w=300&h=259)