When we die, we will lay our bones at La Pointe.

March 20, 2024

By Leo

From individual historical documents, it can be hard to sequence or make sense of the efforts of the United States to remove the Lake Superior Ojibwe from ceded territories of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan in the years 1850 and 1851. Most of us correctly understand that the Sandy Lake Tragedy was caused an alliance of government and trading interests. Through greed, deception, racism, and callous disregard for human life, government officials bungled the treaty payment at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi River in the fall and winter of 1850-51, leading to hundreds of deaths. We also know that in the spring of 1852, Chief Buffalo and a delegation of La Pointe Ojibwe chiefs travelled to Washington D.C. to oppose the removal. It is what happened before and between those events, in the summers of 1850 and 1851, where things get muddled.

Confusion arises because the individual documents can contradict our narrative. A particular trader, who we might want to think is one of the villains, might express an anti-removal view. A government agent, who we might wish to assign malicious intent, instead shows merely incompetence. We find a quote or letter that seems to explain the plans and sentiments leading to the disaster at Sandy Lake, but then we find the quote is dated after the deaths had already occurred.

Therefore, we are fortunate to have the following letter, written in November of 1851, which concisely summarizes the events up to that point. We are even more fortunate that the letter is written by chiefs, themselves. It is from the Office of Indian Affairs archives, but I found a copy in the Theresa Schenck papers. It is not unknown to Lake Superior scholarship, but to my knowledge it has not been reproduced in full.

The context is that Chief Buffalo, most (but not all) of the La Pointe chiefs, and some of their allies from Ontonagon, L’Anse, Upper St. Croix Lake, Chippewa River and St. Croix River, have returned to La Pointe. They have abandoned the pay ground at Fond du Lac in November 1851, and returned to La Pointe. This came after getting confirmation that the Indian Agent, John S. Watrous, has been telling a series of lies in order to force a second Sandy Lake removal–just one year removed from the tragedy. This letter attempts to get official sanction for a delegation of La Pointe chiefs to visit Washington. The official sanction never came, but the chiefs went anyway, and the rest is history.

La Pointe, Lake Superior, Nov. 6./51

To the Hon Luke Lea

Commissioner of Indian Affairs Washington D.C.

Our Father,

We send you our salutations and wish you to listen to our words. We the Chiefs and head men of the Chippeway Tribe of Indians feel ourselves aggrieved and wronged by the conduct of the U.S. Agent John S. Watrous and his advisors now among us. He has used great deception towards us, in carrying out the wishes of our Great Father, in respect to our removal. We have ever been ready to listen to the words of our Great Father whenever he has spoken to us, and to accede to his wishes. But this time, in the matter of our removal, we are in the dark. We are not satisfied that it is the President that requires us to remove. We have asked to see the order, and the name of the President affixed to it, but it has not been shewn us. We think the order comes only from the Agent and those who advise with him, and are interested in having us remove.

Kicheueshki. Chief. X his mark

Gejiguaio X “

Kishkitauʋg X “

Misai X “

Aitauigizhik X “

Kabimabi X “

Oshoge, Chief X “

Oshkinaue, Chief X “

Medueguon X “

Makudeua-kuʋt X “

Na-nʋ-ʋ-e-be, Chief X “

Ka-ka-ge X “

Kui ui sens X “

Ma-dag ʋmi, Chief X “

Ua-bi-shins X “

E-na-nʋ-kuʋk X “

Ai-a-bens, Chief X “

Kue-kue-Kʋb X “

Sa-gun-a-shins X “

Ji-bi-ne-she, Chief X “

Ke-ui-mi-i-ue X “

Okʋndikʋn, Chief X “

Ang ua sʋg X “

Asinise, Chief X “

Kebeuasadʋn X “

Metakusige X “

Kuiuisensish, Chief X “

Atuia X “

Gete-kitigani[inini? manuscript torn]

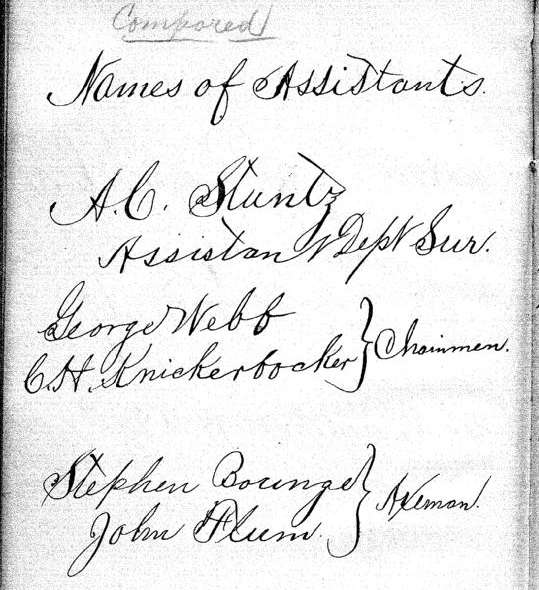

L. H. Wheeler

We the undersigned, certify, on honor, that the above document was shown to us by the Buffalo, Chief of the Lapointe band of Chippeway Indians and that we believe, without implying and opinion respecting the subjects of complaint contained in it, that it was dictated by, and contains the sentiments of those whose signatures are affixed to it.

S. Hall

C. Pulsifer

H. Blatchford

When I started Chequamegon History in 2013, the WordPress engine made it easy to integrate their features with some light HTML coding. In recent years, they have made this nearly impossible. At some point, we’ll have to decide whether to get better at coding or overhaul our signature “blue rectangle” design format. For now, though, I can’t get links or images into the blue rectangles like I used to, so I will have to list them out here:

Joseph Austrian’s description of the same

Boutwell’s acknowledgement of the suspension of the removal order, and his intent to proceed anyway

Chequamegon History has looked into the “Great Father” fur trade theater language of ritual kinship before in our look at Blackbird’s speech at the 1855 Payment. You may have noticed Makadebines (Blackbird) didn’t sign this letter. He was working on a different plant to resist removal. Look for a related post soon.

If you’re really interested in why the president was Gichi-noos (Great Father), read these books:

Watrous, and many of the Americans who came to the Lake Superior country at this time, were from northeastern Ohio. Watrous was able to obtain and keep his position as agent because his family was connected to Elisha Whittlesey.

In the summer and fall of 1851, Watrous was determined to get soldiers to help him force the removal. However, by that point, Washington was leaning toward letting the Lake Bands stay in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Last spring, during one of the several debt showdowns in Congress, I wrote on how similar antics in Washington contributed to the disaster of 1850. My earliest and best understanding of the 1850-1852 timeline, and the players involved, comes from this book:

We know that Kishkitauʋg (Cut Ear), and Oshoge (Heron) went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852. Benjamin Armstrong’s account is the most famous, but the delegation’s other interpreter, Vincent Roy Jr., also left his memories, which differ slightly in the details.

One of my first posts on the blog involved some Sandy Lake material in the Wheeler Family Papers, written by Sherman Hall. Since then, having seen many more of their letters, I would change some of the initial conclusions. However, I still see Hall as having committing a great sin of omission for not opposing the removal earlier. Even with the disclaimer, however, I have to give him credit for signing his name to the letter this post is about. Although they shared the common goal of destroying Ojibwe culture and religion and replacing it with American evangelical Protestantism, he A.B.C.F.M. mission community was made up of men and women with very different personalities. Their internal disputes were bizarre and fascinating.

American Fur Company: 1834 Reinvention of La Pointe

October 4, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

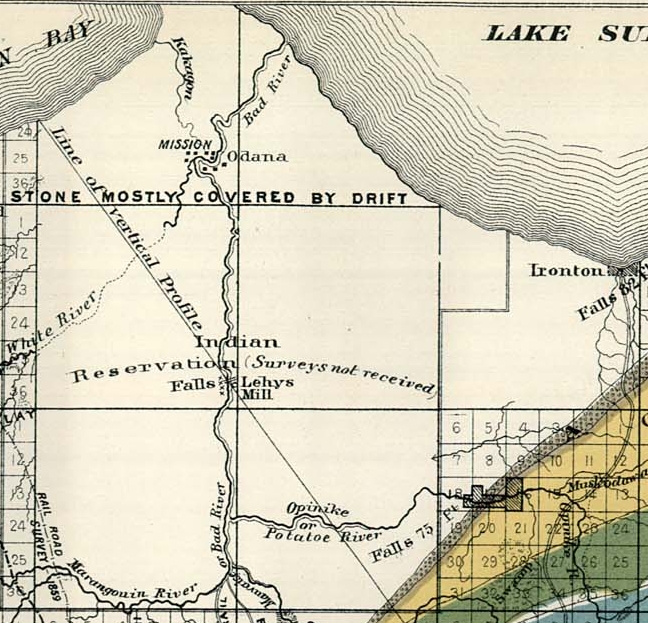

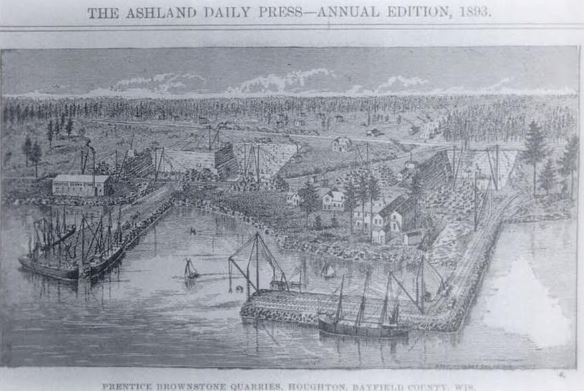

The below image from the Wisconsin Historical Society is a storymap showing La Pointe in 1834 as abstract squiggles on an oversized Madeline Island surrounded by random other Apostle Islands, Bayfield Peninsula, Houghton Point, Chequamegon Bay, Long Island, Bad River, Saxon Harbor, and Montreal River.

“Map of La Pointe”

“L M Warren”

“~ 1834 ~”

Wisconsin Historical Society

citing an original map at the New York Historical Society

My original (ongoing) goal for publishing this post is to find an image of the original 1834 map by Lyman Marcus Warren at the New York Historical Society to explore what all of his squiggles at La Pointe represented in 1834. Instead of immediately achieving my original goal, this post has become the first of a series exploring letters in the American Fur Company Papers by/to/about Warren at La Pointe.

New York Historical Society

American Fur Company Papers: 1831-1849

America’s First Business Monopoly

#16,582

Map of Lapointe

by L M Warren

~ 1834 ~

New York Historical Society

scanned as Gale Document Number GALE|SC5110110218

#36

Lapointe Lake Superior

September 20th ’34

Ramsey Crooks Esqr

Dear Sir

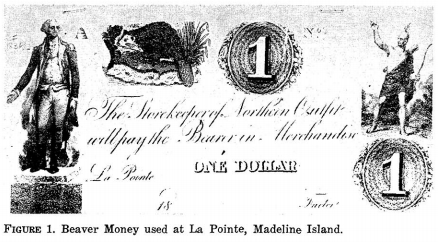

Starting in 1816, the American Fur Company (AFC) operated a trading post by the “Old Fort” of La Pointe near older trading posts built by the French in 1693 and the British in 1793.

In 1834, John Jacob Astor sold his legendary AFC to Ramsay Crooks and other trading partners, who in turn decided to relocate the AFC’s base of operations at Mackinac Island to Madeline Island, where our cartographer Lyman Marcus Warren was employed as the AFC’s trader at La Pointe.

Instead of improving any of the older trading posts on Madeline Island, Warren decided to move La Pointe to the “New Fort” of 1834 to build new infrastructure for growing business demands.

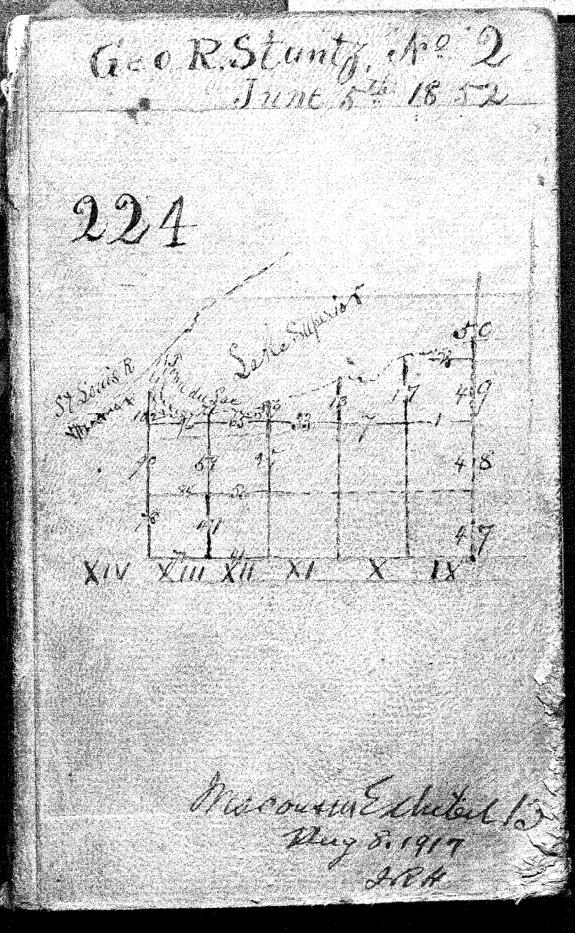

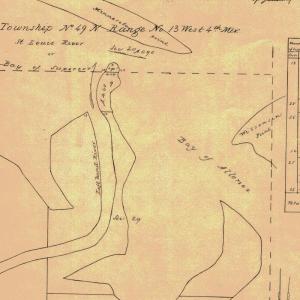

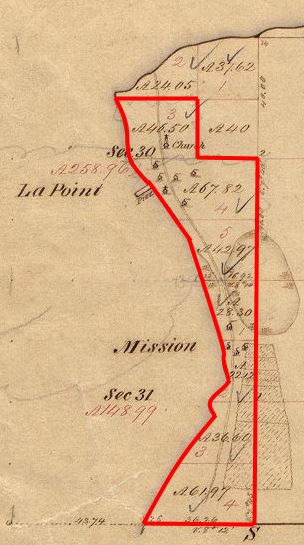

GLO PLSS 1852 survey detail of the “Am Fur Co Old Works” near Old Fort.

on My Way In as Mr Warren was was detained So Long at Mackinac I did not Wait for him at this Place as time was of So Much Consequence to me to Get my People Into the County that I Proceeded Immediately to Fond Du Lac with the Intention with the Intention of Returning to this Place When I Had Sent the Outfit off but When I Got There I Had News from the Interior Which Required me to Go In and Settle the Business there; the [appearance?] In the Interior for [????] is tolerable. Good Provision there is [none?] Whatever I [have?] Seen the [Country?] [So?] Destitute. The Indians at [Fort?] [?????] Disposed to give me Some trouble when they found they have to Get no Debts and buy their amunition and tobacco and not Get it For Nothing as usual but at Length quieted down [?????] and have all gone off to their Haunts as usual.

I Received your Instructions contained in your Circular and will be very Particular In Following them. The outfits were all off when I Received them but the men’s acts and the Invoices of the Goods Had all been Settled according to your Wishes and Every Care Will be taken not to allow the men to get In Debt the Clerks Have Strict orders on the Subject and it is made known to them that they will be Held for any of the Debts the men may Incur.

I Enclose to you the Bonds Signed and all the Funds we Received from Mr Johnston Excepting those Which Had been given to the Clerks and I could not Get them Back In time to Send them on at Present.

Mr Warren And myself Have Committed on What is to be done at this Place and I am certain all that Can be done Will be done by him. I leave here tomorrow For the Interior of Fond Du Lac Where I must be as Soon as possible.

I have written to Mr Schoolcraft as he Inquested me. Mr Brewster’s men would not Give up their [??????] and [???] [????] is [??] [?????] [????] [????] [to?] [???????] [?????] [to?] [persuade?] [more?] People for Keeping [his?] [property?] [Back?] [and] [then?] [???] by some [???] ought to be sent out of the Country [??] they are [under?] [the?] [???] [?] and [Have?] [no?] [Right?] to be [????] [????] they are trouble [????] [???] [their?] [tongues?].

GLO PLSS 1852 survey detail of the AFC’s new “La Point” (New Fort) and the ABCFM’s “Mission” (Middleport).

The Site Selected Here For the Buildings by Mr Warren is the Best there is the Harbour is good and I believe the work will go on well.

as For the Fishing we Will make Every Inquiry on the Subject and I Have no Doubt on My Mind of Fairly present that it will be more valuable than the Fur trade.

In the Month of January I will Write you Every particular How our affairs stand from St Peters. Bailly Still Continues to Give our Indians Credits and they Bring Liquor from that Place which they Say they Get from Him.

Please let Me know as Early as possible with Regard to the Price of Furs as it will Help me In the trade. the Clerks all appear anxious to do their Duty this year as the wind is now Falling and I am In Haste I Will Write you Every particular of our Business In January.

Wishing that God may Long Prosper you and your family.

In health and happiness.

I remain most truly,

and respectfully

yours $$

William A. Aitken

#42

Lake Superior

LaPointe Oct 16 1834

Ramsey Crooks Esqr

Agent American Fur Co

Honoured Sir

Your letter dated Mackinac Sept [??] reached me by Mr Chapman’s boat today.-

I will endeavour to answer it in such a manner as will give you my full and unreserved opinion on the different subjects mentioned in it.

I feel sorry to see friend Holiday health so poor, and am glad that you have provided him a comfortable place at the Sault. As you remark it is a fortunate circumstance that we have no opposition this year or we would certainly have made a poor resistance. I can see no way on which matters would be better arranged under existing circumstances than the way in which you have arranged it. If Chaboillez, and George will act in unison and according to your instructions, they will do well, but I am somewhat affeared, that this will not be the case, as I think George might perhaps from jealously refuse to obey Chaboillez or give him the proper help. Our building business prevents me from going there myself. I suppose you have now received my letter of last Sept, in which I mentioned that I had kept the Doctor here. I shall send him in a few days to see how matters comes on at the Ance. The Davenports are wanted at present in FDLac should it be necessary to make any alteration. I shall leave the Doctor at the Ance.

Undated photograph of the ABCFM Presbyterian Mission Church at it’s original 1830s location along the shoreline of Sandy Bay.

~ Madeline Island Museum

In addition to the AFC’s new La Pointe, Warren was also committed to the establishment of a mission for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) as a condition of his 1827 Deed for Old La Pointe from his Chippewa wife’s parents; Madeline & Michel Cadotte.

Starting in 1830, the ABCFM built a Mission at La Pointe’s Middleport (second French fort of 1718), where they were soon joined by a new Catholic Mission in 1835.

Madeline Island was still unceded territory until the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe. The AFC and ABCFM had obtained tribal permissions to build here via Warren’s deed, while the Catholics were apparently grandfathered in through French bloodlines from earlier centuries.

I think we will want about 2 Coopers but as you suggest I if they may be got cheaper than the [????] [????]. The Goods Mr Hall has got is for his own use that is to say to pay his men [??]. The [??] [??????] [has?] to pay for a piece of land they bot from an Indian woman at Leech Lake. As far as my information goes the Missionaries have never yet interfered with our trade. Mr Hall’s intention is to have his establishment as much disconnected with regular business as he possibly can and he gets his supplies from us.

[We?] [have?] received the boxes [Angus?] [??] [???]. [You?] mention also a box, but I have not yet received it. Possible it is at the Ance.

The report about Dubay has no doubt been exaggerated. When with me at the Ance he mentioned to me that Mr Aitkin told him he had better tell the Indians not to kill their beaver entirely off and thereby ruin their country. The idea struck me as a good one and as far as I recollect I told him, it would perhaps be good to tell them so. I have not yet heard from any one, that he has tried to prevent the Indians from paying their old Debts and I should not be astonished to fend the whole is one of those falsehoods which Indians are want to use to free themselves from paying old Debts. I consider Dubay a pretty active man, but the last years extravagancies have made it necessary to have an eye upon him to prevent him from squandering.

My health had been somewhat impaired by my voyage from the Sault to this place. Instead of going to Lac Du Flambeau myself as I intended I sent the Doctor. He has just now returned and tells me that Dubay gets along pretty well, though there were some small difficulties which toke place, but which the Dr settled. The prospect are very discouraging, particularly on a/c of provisions. We have plenty opposition and all of them with liquor in great abundance. It is provoking to see ourselves restricted by the laws from taking in liquor while our opponents deal in it as largely as ever. The traders names are as far as could be ascertained Francois Charette and [Chapy?]. The liquor was at Lac du Flambeau while the Doctor was there. I have furnished Dubay with means to procure provisions, as there is actually not 1 Sack of Corn or Rice to be got.

The same is the case on Lac Courtoreilie and Folleavoigne no provisions and a Mr Demarais on the Chippeway River gives liquor to the Indians.

You want my ideas upon the fishing business. If reliance can be put in Mr Aitkin’s assertions we will at least want the quantity of Net thread mentioned in our order. Besides this we will want for our fishing business 200 Barrels Flour, [??] Barrels Pork, 10 Kegs Butter, 1000 Bushels Corn, [??] Barrels Lard, 10 or 11 Barrels Tallow.

Besides this we want over and above the years supply an extra supply for our summer Establishments. say about 80 Barrels Flour, 30 Barrels Pork, 1500 # Butter, 400 Bushels Corn, 5 Barrels Lard, 5 Barrels Tallow. This will is partly to sell. be sold.

Mr Roussain will be as good as any if not better in my opinion for our business than Holiday. Ambrose Davenport might take the charge of the Ance but Roussain will be more able on account of his knowledge in fishing. I would recommend to take him as a partner. say take Holidays share if he could not be got for less.

I have not done much yet toward building. The greatest part of my men have been in the exterior to assist our people to get in. But they have now all arrived. We have got about 4 acres of land cleared, a wintering house put up and a considerable quantity of boards sawed. Mr Aitkin did not supply me with two Carpenters as he promised at Mackinac. I will try to get along as well as I can without them. I engaged Jos Dufault and Mr Aitkin brot me one of Abbott’s men, who he engaged. But I will still be under the necessity of hiring Mr Campbell of the mission to make our windows sashes and to superintend The framing of the buildings. Mr Aitkins have done us considerable damage by not fulfilling his promise in this respect. I told you in Mackinac that Mr Aitkin was far from being exact in business. Your letter to him I will forward by the first opportunity. I think it will have a good effect and you do right in being thus plain in stating your views. His contract deserves censure, and I will hope that your plain dealing with him will not be lost upon him. Shall I beg you to be as faithfull to me by giving me the earliest information whenever you might disapprove of any transaction of mine.

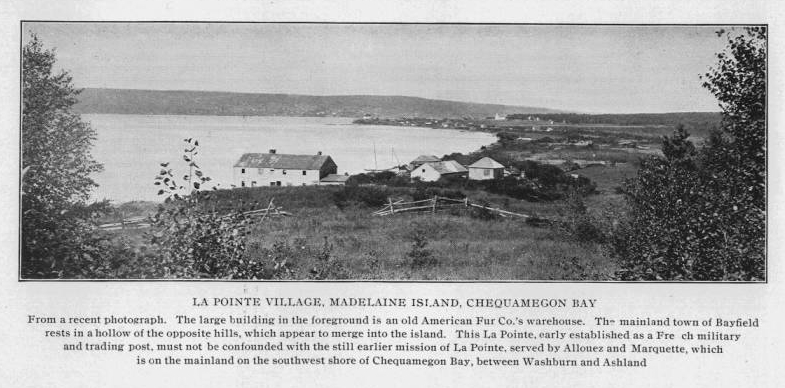

Photograph of La Pointe from Mission Hill circa 1902.

~ Wisconsin Historical Collections, Volume XVI, page 80.

I have received a supply of provisions from Mr Chapmann which will enable me to get through this season. The [?] [of?] [???] [next?], the time you have set for the arrival of the Schooner, will be sufficient, early for our business. The Glass and other materials for finishing of the buildings would be required to be sent up in the first trip but if [we?] [are?] [??] better to have them earlier. If these articles could be sent to the Sault early in the Spring a boat load might be formed of [Some?] and Provisions and sent to the Ance. From there men could be spared at that season of the year to bring the load to this place. In that way there would be no heavy expense incurred and I would be able to have the buildings in greater forwardness.

If the plan should meet your approbation please let me know by the winter express. While Mr Aitkin was here we planned out our buildings. The House will be 86 feet by 26 feet in the clear, the two stores will be put up agreeable to your Draft. We do not consider them to large.

I am afraid I shall not be able to build a wharf in season, but shall do my best to accomplish all that can be done with the means I have.

Undated photograph of Captain John Daniel Angus’ boat at the ABCFM mission dock.

~ Madeline Island Museum

I would wish to call your attention towards a few of the articles in our trade. I do not know how you have been accustomed to buy the Powder whether by the Keg or pound. If a keg is estimated at 50#, there is a great deception for some of our kegs do not contain more than 37 or 40 #s.

Our Guns are very bad particularly the barrels. They splint in the inside after been fired once or twice.

Our Holland twine is better this year than it has been for Years. One dz makes about 20 fathoms, more than last year. But it would be better if it was bleached. The NW Company and old Mr Ermantinger’s Net Thread was always bleached. It nits better and does not twist up when put into the water. Our maitre [??] [???] are some years five strand. Those are too large we have to untwist them and take 2 strands out. Our maitre this year are three strand they are rather coarse but will answer. They are not durable nor will they last as long as the nets of course they have to be [renewed?]. The best maitres are those we make of Sturgeon twine. We [?????] the twine and twist it a little. They last twice as long as our imported maitres. The great object to be gained is to have the maitres as small as possible if they be strong enough. Three coarse strands of twisted together is bulky and soon nits.

Our coarse Shoes are not worth bringing into the country. Strong sewed shoes would cost a little more but they would last longer. The [Booties?] and fine Shoes are not much better.

Our Teakettles used to have round bottoms. This year they are flat. They Indians always prefer the round bottom.

In regard to the observations you have made concerning the Doctor’s deviating from the instructions I gave him on leaving Mackinac, I must in justice to him say that I am now fully convinced in my own mind that he misunderstood me entirely, merely by an expression of mine which was intended by me in regard to his voyage from Mackinac to the Sault but by him was mistaken for the route through Lake Superior. The circumstances has hurt his feelings much and as he at all times does his best for the Interest of the Outfit I ought to have mentioned in my last letter, but it did not strike my mind at that time.

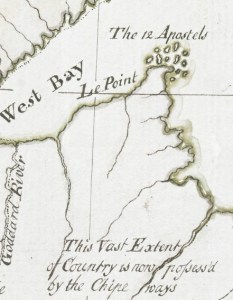

Detail from Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques Nicolas Bellin in 1744.

When Mr Aitkin was here he mentioned to me some information he had obtained from somebody in Fond du Lac who had been in the NW Co service relating to a remarkable good white fish fishery on the “Milleau” or “Millons” Islands (do not know exactly the proper name). They lay right opposite to Point Quiwinau. a vessel which passes between the island and the point can see both. Among Mr Chapmann’s crew here there is an old man who tells me that he knew the place well, he says the island is large, say 50 or 60 miles. The Indian used to make their hunts there on account of the great quantity of Beaver and Reindeer. It is he says where the NWest Co used to make their fishing for Fort William. There is an excellent harbour for the vessel it is there where the largest white fish are caught in Lake Superior. Furthermore the old man says the island is nearer the American shore than the English. Some information might be obtained from Capt. McCargo. If it proves that we can occupy the grounds I have the most sanguine hopes that we shall succeed in the fisheries upon a large scale.

I hope you will gather all the information you can on the subject. Particular where the line runs. If it belongs to the Americans we must make a permanent post on the Island next year under the charge of an active person to conduct the fisheries upon a large scale.

Jh Chevallier one of the men I got in Mackinac is a useless man, he has always been sick since he left Sault. Mr Aitkin advised me to send him back in Chapman’s Boat. I have therefore send him out to the care of Mr Franchere.

By the Winter Express I will to give you all the informations that I may be able to give. I will close by wishing you great health and prosperity. Please present my Respects to Mr Clapp.

I remain Dear Sir.

Very Respectfully Yours

Most Obedient Servant

Lyman M. Warren

To be Continued in 1835…

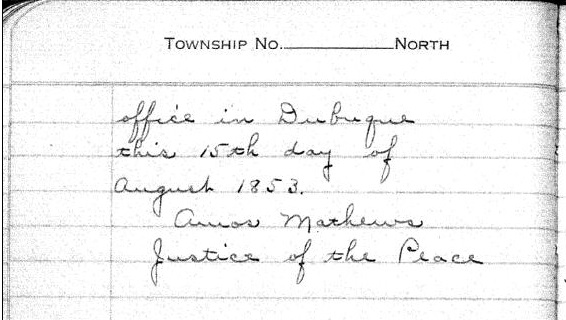

Wheeler Papers: 1854 La Pointe before the Treaty

August 7, 2017

By Amorin Mello

Selected letters from the

Wheeler Family Papers,

Box 3, Folders 11-12; La Pointe County.

Crow-wing, Min. Ter.

Jan. 9th 1854

Brother Wheeler,

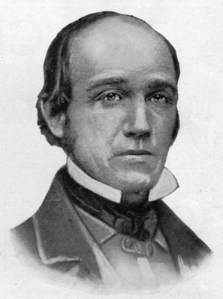

Reverend Leonard Hemenway Wheeler ~ In Unnamed Wisconsin by Silas Chapman, 1895, cover image.

Though not indebted to you just now on the score of correspondence, I will venture to intrude upon you a few lines more. I will begin by saying we are all tolerably well. But we are somewhat uncomfortable in some respects. Our families are more subject to colds this winter than usual. This probably may be attributed in part at least to our cold and open houses. We were unable last fall to do any thing more than fix ourselves temporarily, and the frosts of winter find a great many large holes to creep in at. Some days it is almost impossible for us to keep warm enough to be comfortable.

Our prospects for accomplishing much for the Indians here I do not think look more promising than they did last fall. There are but few Indians here. These get drunk every time they can get whiskey, of which there is an abundance nearby. Among the white people here, none are disposed to attend meetings much except Mr. [Welton?]. He and his wife are discontented and unhappy here, and will probably get away as soon as they can. We hear not a word from the Indian Department. Why they are minding us in this manner I cannot tell. But I should like it much better, if they would tell us at once to be gone. I have got enough of trying to do anything for Indians in connection with the Government. We can put no dependence upon any thing they will do. I have tried the experiment till I am satisfied. I think much more could be done with a boarding school in the neighborhood of Lapointe than here And my opinion is, that since things have turned out as they have here, we had better get out of it as soon as we can. With such an agent as we now have, nothing will prosper here. He is enough to poison everything, and will do more moral evil in such a community, as this, than a half a dozen missionaries can do good. My opinion is, that if they knew at Washington how things are and have been managed here, there would be a change. But I do not feel certain of this. For I sometimes am tempted to adopt the opinion that they do not care much there how things go here. But should there be a change, I have little hope that is would would make things materially better. The moral and social improvement of the Indians, I fear, has little to do with the appointment of agents and superintendents. I do not think I ought to remain here very long and keep my family here, as things are now going. If we were not involved with the Government with regard to the school matter, I would advise the Committee to quit here as soon as we can find a place to go to. My health is not very good. The scenes, and labors and attacks of sickness which I have passed through during the past two years have made almost a wreck of my constitution. It might rally under some circumstances. But I do not think it will while I stay here, so excluded from society, and so harassed with cares and perplexities as I have been and as I am likely to be in future, should we go on and try to get up a school. My wife is in no better spirits than I am. She has had several quite ill turns this winter. the children all wish to get away from here, and I do not know that I shall have power to keep them here, even if I am to stay.

But what to do I do not know. The Committee say they do not wish to abandon the Ojibwas. I cannot in future favor the removal of the lake Indians. I believe that all the aid they will receive from the Government will never civilize or materially benifit them. I judge from the manner in which things have been managed here. Our best hope is to do what we can to aid them where they are to live peaceably with the whites, and to improve and become citizens. The idea of the Government sending infidels and heathens here to civilize and Christianize the Indians is rediculous.

I always thought it doubtful whether the experiment we are trying would succeed. In that case it was my intention to remove somewhere below here, and try to get a living, either by raising my potatoes or by trying to preach to white people, or by uniting both. but I do not hardly feel strong enough to begin entirely anew in the wilderness to make me a home. I suppose my family would be as happy at Lapointe, as they would any where in the new and scattered settlements for fifty or a hundred miles below here. And if thought I could support myself then, I might think of going back there. There are our old friends for whose improvement we have laborred so many years. I feel almost as much attachment for them as for my won children. And I do not think they ought to be left like sheep upon the mountains without a shepherd. And if the Board think it best to expend money and labor for the Ojibwas, they had better expend it there than here, as things now are at least. I think we were exerting much much more influence there before we left, then we have here or are likely to exert. I have no idea that the lake Indians will ever remove to this place, or to this region.

Reverend Sherman Hall

~ Madeline Island Museum

What do you think of recommending to the Board to day to exert a greater influence on the people in the neighborhood of Lapointe[?/!] I feel reluctant to give up the Indians. And if I could get a living at Lapointe, and could get there, I should be almost disposed to go back and live among those few for whom I have labored so long, if things turn out here as I expect they will. I have not much funds to being life with now, nor much strength to dig with. But still I shall have to dig somewhere. The land is easier tilled in this region than that about the lake. But wood is more scarce. My family do not like Minesota. Perhaps they would, if they should get out of the Indian country. Edwin says he will get out of it in the spring, and Miles says he will not stay in such a lonesome place. I shall soon be alone as to help from my children. My boys must take care of themselves as soon as they arrive at a suitable age, and will leave me to take care of myself. We feel very unsettled. Our affairs here must assume a different aspect, or we cannot remain here many months longer. Is there enough to do at Lapointe; or is there a prospect that there will soon be business to draw people enough then, to make it an object to try to establish the institution of the gospel there? Write me and let me know your views on such subjects as these.

[Unsigned, but appears to be from Sherman Hall]

Crow-wing Feb. 10th 1854

Brother Wheeler:

I received your letter of jan. 16th yesterday, and consequently did not sleep as much as usual last night. We were glad to hear that you are all well and prosperous. We too are well which we consider a great blessing, as sickness in present situation would be attended with great inconvenience. Our house is exceedingly cold and has been uncomfortable during some of the severe cold weather have had during the last months. Yet we hope to get through the winter without suffering severely. In many respects our missionary spirit has been put to a severer test than at any previous time since we have been in the Indian country, during the past year. We feel very unsettled, and of course somewhat uneasy. The future does not look very bright. We cannot get a word from the Indian Department whether we may go on or not. If we cannot get some answer from them before long I shall be taking measures to retire. We have very little to hope, I apprehend, from all the aid the Government will render to words the civilization and moral and intellectual improvement of the Indians. For missionaries or Indians to depend on them, is to depend on a broken staff.

~ Minnesota Historical Society

“The American Fur Company therefore built a ‘New Fort’ a few miles farther north, still upon the west shore of the island, and to this place, the present village, the name La Pointe came to be transferred. Half-way between the ‘Old fort’ and the ‘New fort,’ Mr. Hall erected (probably in 1832) ‘a place for worship and teaching,’ which came to be the centre of Protestant missionary work in Chequamegon Bay.”

~ The Story of Chequamegon Bay

I do not see that our house is so divided against itself, that it is in any great danger of falling at present. My wife never did wish to leave Lapointe and we have ever, both of us, thought that the station ought not to be abandoned, unless the Indians were removed. But this seemed not to be the opinion of the committee or of our associates, if I rightly understood them. I had a hard struggle in my mind whether to retire wholly from the service of the Board among the Indians, or to come here and make a further experiment. I felt reluctant to leave them, till we had tried every experiment which held out any promise of success. When I remove my family here our way ahead looked much more clear than it does now. I had completed an arrangement for the school which had the approval of Gov. Ramsey, and which fell through only in consequence of a little informality on his part, and because a new set of officers just then coming into power must show themselves a little wiser than their predecessors. Had not any associates come through last summer, so as to relieve me of some of my burdens and afford some society and counsel in my perplexities I could not have sustained the burden upon me in the state of my health at that time. A change of officers here too made quite an unfavorable change in our prospects. I have nothing to reproach myself with in deciding to come here, nor in coming when we did, though the result of our coming may not be what we hoped it would be. I never anticipated any great pleasure in being connected with a school connected in any way with the Government, nor did I suppose I should be long connected with it, even if it prospered. I have made the effort and now if it all falls, I shall feel that Providence has not a work for us to do here. The prospects of the Indians look dark, what is before me in the future I do not know. My health is not good, though relief from some of the pressure I had to sustain for a time last fall and the cold season has somewhat [?????] me for the time being. But I cannot endure much excitement, and of course our present unsettled affairs operate unfavorably upon it. I need for a time to be where I can enjoy rest from everything exciting, and when I can have more society that I have here, and to be employed moderately in some regular business.

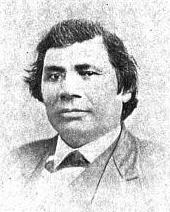

Antoine Gordon [Gaudin]

~ Noble Lives of a Noble Race by the St. Mary’s Industrial School (Bad River Indian Reservation), 1909, page 207.

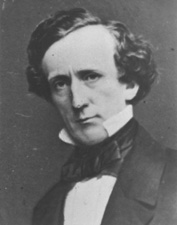

Charles Henry Oakes

~ Findagrave.com

As to your account I have not had time to examine it, but will write you something about it by & by. As to any account which Antoine Gaudin has against me, I wish you would have him send it to me in detail before you pay it. I agreed with Mr. Nettleton to settle with him, and paid him the balance due to Antoine as I had the account. I suppose he made the settlement, when he was last at Lapointe. As to the property at Lapointe, I shall immediately write to Mr. Oakes about it. But I suppose in the present state of affairs, it will be perhaps, a long time before it will be settled so as to know who does own it. It is impossible for me to control it, but you had better keep posession of it at present. I cannot send Edwin [??] through to cultivate the land & take care of it. He will be of age in the spring, and if he were to go there I must hire him. He will probably leave us in the spring. Please give my best regards to all. Write me often.

Yours truly

S. Hall

Crow-wing, Min. Ter.

Feb. 21st 1854

Brother Wheeler,

Paul Hudon Beaulieu

~ FamilySearch.org

I wrote you a few days ago, and at the same time I wrote to Mr. Oakes inquiring whether he had got possession of the Lapointe property. I have not yet got a reply from him, but Mr. Beaulieu tells me that he heard the same report which you mentioned in your letter, and that he inquired of Mr. Oakes about it when he saw him on a recent visit to St. Paul, and finds that it is all a humbug. Oakes has nothing to do with it. Mr. Beaulieu said that the sale of last spring has been confirmed, and that Austrian will hold Lapointe. So farewell to all the inhabitants’ claims then, and to anything being done for the prosperity of the peace for the present, unless it gets out of his hands.

I have written to Austrian to try to get something for our property if we can. But I fear there is not much hope. If he goes back to Lapointe in the spring, do the best you can to make him give us something. I feel sorry for the inhabitants there that they are left at his mercy. He may treat them fairly, but it is hardly to be expected.

Clement Hudon Beaulieu

~ TreatiesMatter.org

As to our affairs here, there has been no particular change in their aspects since I wrote a few days ago. There must be a crisis, I think, in a few weeks. We must either go on or break up, I think, in the spring. We are trying to get a decision. I understand our agent has been threatened with removal if he carries on as he has done. I believe there is no hope of reformation in his case, and we may get rid of him. Perhaps God sent us here to have some influence in some such matters, so intimately connected with the welfare of the Indians. I have never thought I [????] can before I was sent in deciding to come here. Some trials and disappointments have grown out of my coming, but I feel conscious of having acted in accordance with my convictions of duty at this time.

If all falls through, I know not what to do in the future. The Home Missionary Society have got more on their hands now than they have funds to pay, if I were disposed to offer myself to labor under them. I may be obliged to build me a shanty somewhere on some little unoccupied piece of land and try to dig out a living. In these matters the Lord will direct by his providence.

You must be on your guard or some body will trip you up and get away your place. There are enough unprincipled fellows who would take all your improvements and send you and all the Indians into the Lake if they could make a dollar by it. I should not enlarge much, without getting a legal claim to the land. Neither would I advise you to carry on more family than is necessary to keep what team you must have, and to supply your family with milk and vegetables. It will be advantage/disadvantage to you in a pecuniary point of view, it will load you with and tend to make you worldly minded, and give your establishment the air of secularity in the eyes of the world. If I were to go back again to my old field, I would make my establishment as small as I could & have enough to live comfortable. I with others have thought that your tendency was rather towards going to largely into farming. I do not say these things because I wish to dictate or meddle with your affairs. Comparing views sometimes leads to new investigations in regard to duty.

May the Lord bless you and yours, and give you success and abundant prosperity in your labours of love and efforts to Save the Souls around you.

Give my best regards to Mrs. W., the children, Miss S and all.

Yours truly,

S. Hall

I forgot to say that we are all well. Henry and his family have enjoyed better health here, then they used to enjoy at Lapointe.

Feb 27

Brother Wheeler.

My delay to answer your note may require an explanation. I have not had time at command to attend to it conveniently at an earlier period. As to your first questions. I suppose there will be no difference of opinion between us as to the correctness of the following remarks.

- The Gospel requires the members of a church to exercise a spirit of love, meekness and forbearance towards an offending brother. They are not to use unnecessary severity in calling him to account for his errors. Ga. 6:1.

- The Object of Church discipline is, not only to [pursue/preserve?] the Church pure in doctrine & morals, that the contrary part may have no evil thing to say of them; but also to bring the offender to a right State of mind, with regard this offense, and gain him back to duty and fidelity.

- If prejudice exist in the mind of the offender towards his brethren for any reason, the spirit of the gospel requires that he be so approached if possible as to allay that prejudice, otherwise we can hardly expect to gain a candid hearing with him.

Charles William Wulff Borup, M.D. ~ Minnesota Historical Society

I consider that these remarks have some bearing on the case before us. If it was our object to gain over Dr. B. to our views of the Sabbath, and bring him to a right State of mind with regard this Sabbath breaking, the manner of approaching him would have, in my view, much to do with the offence. He may be approached in a Kind and [forbearing?] manner, when one of sternness and dictation will only repel him from you. I think we ought, if possible, and do our duty, avoid a personal quarrel with him. To have brought the subject before the Church & made a public affair of it, before [this/then?] and more private means have been tried to get satisfaction, would, I am sure, have resulted in this. I found from my own interviews with him, that there was hope, if the rest of the brethren would pursue a similar course. I felt pretty sure they would obtain satisfaction. IF they had [commenced?] by a public prosecution before the church, it would only have made trouble without doing any good. The peace of our whole community would have been disturbed. I thought one step was gained when I conversed with him, and another when you met him on the subject. I knew also that prejudices existed both in his mind towards us, & in our minds towards him which were likely to affect the settlement of this affair, and which as I thought, would be much allayed by individuals going to him and speaking face to face on this subject in private. He evidently expected they would do so. Mutual conversations and explanations allay these feelings very much. At least it has been so in my experience.

As to your second question. I do not say that it was Mr. Ely’s duty to open the subject to Doc. Borup at the preparatory lecture. If he had done so, it would have been only a private interview; for there [was?] not enough present to transact business. All I meant to affirm respecting that occasion is, that it afforded a good opportunity to do so, if he wishes, and that Dr. B. expected he would have done so, as I afterwards learnt, if he has any objection to make against his coming to the communion.

As to your third question. I have no complaint to make of the church, that I have urged them to the performance of any “duties“ in this case they have refused to perform.

And now permit me to ask in my turn.

What “duties” have they urged me to perform in this case, which I “have been unwilling, or manifested a reluctance to perform?”

Did you intend by anything which wrote to me or said verbally, to request me to commence a public prosecution of Doc. Borup before the Church?

Will you have the goodness to state in writing, the substance of what you said to me in your study as to your opinion and that of others suspecting my delinquency in maintaining church discipline.

A reply to these questions would be gratefully received.

Your brother in Christ

S. Hall

Crow Wing. March 12th 1854

Brother Wheeler:

Your letter of Feb 17th came to hand by our last mail; and though I wrote you but a short time ago, I will say a few words in relation to one or two topics to which you allude. Shortly after I received your former letter I wrote to Mr. Oakes enquiring about the property at Lapointe. In reply, says that himself and some others purchased Mr. Austrian’s rights at Lapointe of Old Hughes on the strength of a power of attorney which he held. Austrian asserts the power of attorney to be fraudulent, and that they cannot hold the property. Oakes writes as if he did not expect to hold it. Some time ago I wrote to Mr. Austrian on the same subject, and said to him that if I could get our old place back, I might go back to Lapointe. He says in reply —

Julius Austrian

~ Madeline Island Museum

“I should feel much gratified to see you back at Lapointe again, and can hold out to you the same inducements and assurances as I have done to all other inhabitants, that is, I shall be at Lapointe early in the spring and will have my land surveyed and laid out into lots, and then I shall be ready to give to every one a deed for the lot he inhabits, at a reasonable price, not paying me a great deal more than cost trouble, and time. But with you, my dear Sir, will be no trouble, as I have always known you a just and upright man, and have provided ways to be kind towards us, therefore take my assurance that I will congratulate myself to see you back again; and it shall not be my fault if you do not come. If you come to Lapointe, at our personal interview, we will arrange the matter no doubt satisfactory.”

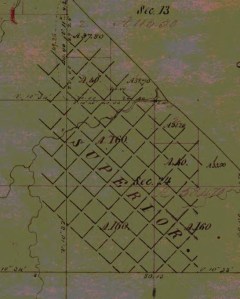

“The property” from the James Hughes Affair is outlined in red. This encompassed the Church at La Pointe (New Fort) and the Mission (Middleport) of Madeline Island. 1852 PLSS survey map by General Land Office.

I suppose Austrian will hold the property and probably we shall never realize anything for our improvements. You must do the best you can. Make your appeal to his honor, if he has any. It will avail nothing to reproach him with his dishonesty. I do not know what more I can do to save anything, or for any others whose property is in like circumstances with ours.

You speak discouragingly of my going back to Lapointe. I do not think the Home Miss. Soc. would send a missionary there only for the few he could reach in the English language. If the people want a Methodist, encourage them to get one. It is painful to me to see the place abandoned to irreligion and vices of every Kind, and the labours I have expended there thrown away. I can hardly feel that it was right to give up the station when we did. If I thought I could support myself there by working one half the time and devoting the rest to ministerial labors for the good of those I still love there, I should still be willing to go back, if could get there & had a shelter for my head, unless there is a prospect of being more useful here. But the land at Lapointe is so hard to subdue that I am discouraged about making an attempt to get a living there by farming. I am not much of a fisherman. There is some prospect that we may be allowed to go on here. Mr. Treat has been to Washington, and says he expects soon to get a decision from the Department. We have got our school farm plowed, and the materials are drawn out of the woods for fencing it. If I have no orders to the contrary, I intend to go on & plant a part of it, enough to raise some potatoes. We may yet get our school established. If we can go ahead, I shall remain here, but if not, I think it is not my duty to remain here another year, as I have the past. In other circumstances, I could do more towards supporting myself and do more good probably.

I have felt much concerned for the people of Lapointe and Bad River on account of the small pox. May the Lord stay this calamity from spreading among you. Write us every mail and tell us all. It is now posted here today that the Old Chief [Kibishkinzhugon?] is dead. I hardly credit the report, though I should suppose he might be one of the first victims of the disease.

I can write no more now. We are all very well now. Give my love to all your family and all others.

Tell Robert how the matters stands about the land. It stands him in how to be on good terms with the Jew just now.

Yours truly,

S. Hall

The snow is nearly all off the ground and the weather for two or three weeks has been as mild as April.

Crow Wing M.H. Apr. 1 1854

Dear Br. & Sr. Wheeler.

I have received a letter from you since I wrote to you & am therfore in your debt in that matter. I have also read your letters to Br. & Sr. Welton I suppose you have received my letter of the 13th of Feb. if so, you have some idea of our situation & I need say no more of that now; & will only say that we are all well as usual & have been during the winter. Mrs. P_ is considerably troubled with her old spinal difficulty. She has got over her labors here last summer * fall. Harriet is not well I fear never will be, because the necessary means are not likely to be used, she has more or less pain in her back & side all the time, but she works on as usual & appears just as she did at LaPointe, if she could be freed from work so as to do no more than she could without injury & pursue uninterruptedly & proper medical course I think she might regain pretty good health. (Do not, any of you, send back these remarks it would not be pleasing to her or the family.) We have said what we think it best to say) –

Br. Hall is pretty well but by no means the vigorous man he once was. He has a slight – hacking cough which I suppose neither he nor his family have hardly noticed, but Mrs. P_ says she does not like the sound of it. His side troubles him some especially when he is a good deal confined at writing. Mr. & Mrs. W_ are in usual health. Henry’s family have gone to the bush. They are all quite well. He stays here to assist br. H_ in the revision & keeps one or two of his children with him. They are now in Hebrews, with the Revision. Henry I suppose still intends to return to Lapointe in the spring. –

Now, you ask, in br. Welton’s letter, “are you all going to break up there in the spring.” Not that I know of. It would seem to me like running away rather prematurely. When the question is settled, that we can do nothing here, then I am willing to leave, & it may be so decided, but it is not yet. We have not had a whisper from Govt. yet. Wherefore I cannot say.

It looks now as if we must stay this season if no longer. Dr. Borup writes to br. Hall to keep up good courage, that all will come out right by & by, that he is getting into favor with Gov. Gorman & will do all he can to help us. (Br. Hall’s custom is worth something you know).

Henry C. Gilbert

~ Branch County Photographs

By advise of the Agent, we got out (last month) tamarack rails enough to fence the school farm (which was broke last summer) of some 80 acres & it will be put up immediately. Our great father turned out the money to pay for the job. These things look some like our staying awhile I tell br H_ I think we had better go as far as we can, without incurring expense to the Board (except for our support) & thus show our readiness to do what we can. if we should quit here I do not know what will be done with us. Br Hall would expect to have the service of the Board I suppose. Should they wish us to return to Bad River we should not say nay. We were much pleased with what we have heard of your last fall’s payment & I am as much gratified with the report of Mr. H. C. Gilbert which I have read in the Annual Report of the Com. of Indian Affairs. He recommends that the Lake Superior Indians be included in his Agency, that they be allowed to remain where they are & their farmers, blacksmith & carpenter be restored to them. If they come under his influence you may expect to be aided in your efforts, not thwarted , by his influence. I rejoice with you in your brightening prospects, in your increased school (day & Sabbath) & the increased inclination to industry in those around you. May the lord add his blessing, not only upon the Indians but upon your own souls & your children, then will your prosperity be permanent & real. Do not despise the day of small things, nor overlook especially neglect your own children in any respect. Suffer them not to form idle habits, teach them to be self reliant, to help themselves & especially you, they can as well do it as not & better too, according to their ability & strength, not beyond it, to fear God & keep his commandments & to be kind to one another (Pardon me these words, I every day see the necessity of what I have said.) We sympathize with you in your situation being alone as you are, but remember you have one friend always near who waits to [commence?] with you, tell Him & all with you from Abby clear down to Freddy.

Affectionately yours

C. Pulsifer

Write when you can.

Crow wing Min. Ter.

April 3d 1854

Brother Wheeler

George E. Nettleton and his brother William Nettleton were pioneers, merchants, and land speculators at what is now Duluth and Superior.

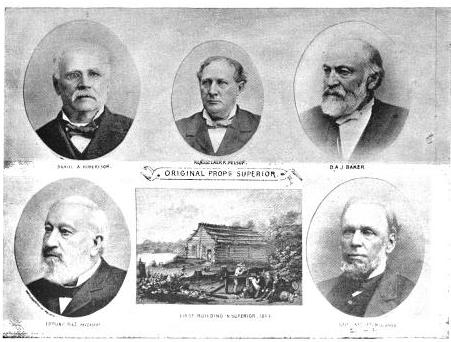

~ Image from The Eye of the North-west: First Annual Report of the Statition of Superior, Wisconsin by Frank Abial Flower, 1890, page 75.

Since I wrote you a few days ago, I have received a letter from Mr. G. E. Nettleton, in which he says, that when he was at Lapointe in December last, he was very much hurried and did not make a full settlement with Antoine. He says further, that he showed him my account, and told him I had settled with him, and that he would see the matter right with Antoine. A. replied that all was right. I presume therefore all will be made satisfactory when Mr. N. comes up in the Spring, and that you will have need to make yourself no further trouble about this matter.

I have also received a short note from Mr. Treat in which he says,

“I have not replied to your letters, because I have been daily expecting something decisive from Washington. When I was there, I had the promise of immediate action; but I have not heard a word from them”.

“I go to Washington this Feb, once more. I shall endeavor to close up the whole business before I return. I intend to wait till I get a decision. I shall propose to the Department to give up the school, if they will indemnify us. If I can get only a part of what we lose, I shall probably quit the concern”.

Thus our business with the Government stood on March the 9th, I have lost all confidence in the Indian Department of our Government under this administration, to say nothing of the rest of it. If the way they have treated us is an index to their general management, I do not think they stand very high for moral honesty. The prospects for the Indians throughout all our territories look dark in the extreme. The measures of the Government in relation to them are not such as will benefit and save many of them. They are opening the floodgates of vice and destruction upon them in every quarter. The most solemn guarantees that they shall be let alone in the possession of domains expressly granted them mean nothing.

Our prospects here look dark. For some time past I have been rather anticipating that we should soon get loose and be able to go on. But all is thrown into the dark again. What I am to do in future to support my family, I do not know. If we are ordered to quit here and turn over the property, it would turn [illegible] out of doors.

Mr. Austrian expects us back to Lapointe in the Spring & Mr. Nettleton proposes to us to go to Fond du Lac, (at the Entry). He says there will be a large settlement then next season. A company is chartered to build a railroad through from the Southern boundary of this territory to that place. It is probable that Company [illegible] will make a grant of land for that purpose. If so, it will probably be done in a few years. That will open the lake region effectually. I feel the need of relaxation and rest before I do anything to get established anywhere.

We are still working away at the Testament, it is hard work, and we make lately but slow progress. There is a prospect that the Bible Society will publish it but it is not fully decided. I wish I could be so situated that I could finish the grammar.

But I suppose I am repeating what I have said more than once before. We are generally in good health and spirits. We hope to hear from by next mail.

Yours truly

S. Hall

What do you think about the settlements above Lapointe and above the head of the Lake?

Detroit July 10th 1854

Rev. Dr. Bro.

At your request and in fulfilment of my promise made at LaPointe last fall so after so long a time I write: And besides “to do good & to communicate” as saith the Apostle “forget not, for with such sacrifices God is well pleased.”

We did not close up our Indian payments of last year until the middle of the following January, the labors, exposures and excitements of which proved too much for me and I went home to New York sick & nearly used up about the last of February & continued so for two months. I returned here about a week ago & am now preparing for the fall pay’ts.

The Com’sr. has sent in the usual amounts of Goods for the LaPointe Indians to Mr. Gilbert & I presume means to require him to make the payment at La P. that he did last fall, although we have received nothing from the Dep’t. on the subject.

“George Washington Manypenny (1808-1892) was the Director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs of the United States from 1853 to 1857.”

~ Wikipedia.org

In regard to the Treaty with the Chipp’s of La Sup’r & the Miss’i, the subject is still before Congress and if one is made this fall it has been more than intimated that Com’r Manypenny will make it himself, either at LaP’ or at F. Dodge or perhaps at some place farther west. Of course I do not speak from authority or any of the points mentioned above, for all is rumour & inference beyond the mere arrival here of the Goods to Mr G’s care.

From various sources I learn that you have passed a severe winter and that much sickness has been among the Indians and that many of them have been taken away by the Small Pox.

This is sad and painful intelligence enough and I can but pray God to bless & overrule all to the goods of his creasures and especially to the Missionaries & their families.

Notwithstanding I have not written before be assured that I have often [???] of and prayed for you and yours and while in [Penn.?] you made your case my own so far as to represent it to several of our Christian brethren and the friends of missions there and who being actuated by the benevolent principles of the Gospel, have sent you some substanted relief and they promise to do more.

The Elements of the political world both here and over the waters seem to be in fearful & [?????] commotion and what will come of it all none but the high & holy one can know. The anti Slavery Excitement with us at the North and the Slavery excitement at the South is augmenting fact and we I doubt not will soon be called upon to choose between Slavery & freedom.

If I do not greatly misjudge the blessed cause of our holy religion is or seems to be on the wane. I trust I am mistaken, but the Spirit of averice, pride, sensuality & which every where prevails makes me think otherwise. The blessed Christ will reign [recenth-den?] and his kingdom will yet over all prevail; and so may it be.

Let us present to him daily the homage of a devout & grateful heart for his tender mercies [tousward?] and see to it that by his grace we endure unto the end that we may be saved.

My best regards to Mrs. W. to Miss Spooner to each of the dear children and to all the friends & natives to each of whom I desire to be remembered as opportunity occurs.

The good Lord willing I may see you again this fall. If I do not, nor never see you again in this world, I trust I shall see and meet you in that world of pure delight where saints immortal reign.

May God bless you & yours always & ever

I am your brother

In faith Hope & Charity

Rich. M. Smith

Rev Leonard H. Wheeler

LaPointe

Lake Superior

Miss. House Boston

Augt’ 31, 1854

Rev. L. H. Wheeler,

Lake Superior

Dear Brother

Yours of July 31 I laid before the Com’sr at our last meeting. They have formally authorized the transfer of Mr & Mrs Pulsifer to the Lake, & also that of Henry Blatchford.

Robert Stuart was formerly an American Fur Company agent and Acting Superintendent on Mackinac Island during the first Treaty at La Pointe in 1842.

~ Wikipedia.org

In regard to the “claims” their feeling is that if the Govt’ will give land to your station, they have nothing to say as to the quantity. But if they are to pay the usual govt’ price, the question requires a little caution. We are clear that we may authorize you to enter & [???] take up so much land as shall be necessary for the convenience of the [mission?] families; but we do not see how we can buy land for the Indians. Will you have the [fondness?] to [????] [????] on these points. How much land do you propose to take up in all? How much is necessary for the convenience of the mission families?

Perhaps you & others propose to take up the lands with private funds. With that we have nothing to do, so long as you, Mr P. & H. do not become land speculators; of which, I presume, there is no danger.

As to the La Pointe property, Mr Stuart wrote you some since, as you know already I doubt not, and replied adversely to making any bargain with Austrian. I took up the opinion of the Com’sr after receiving your letter of July 31, & they think it the wise course. I hope Mr Stewart will get this matter in some shape in due time.

I will write to him in reference to the Bad River land, asking him to see it once if the gov’ will do any thing.

Affectionate regards to Mrs W. & Miss Spooner & all.

Fraternally Yours

S. B. Treat

P.S. Your report of July 31 came safely to hand, as you will & have seen from the Herald.

Leonard Wheeler Obituary

May 31, 2014

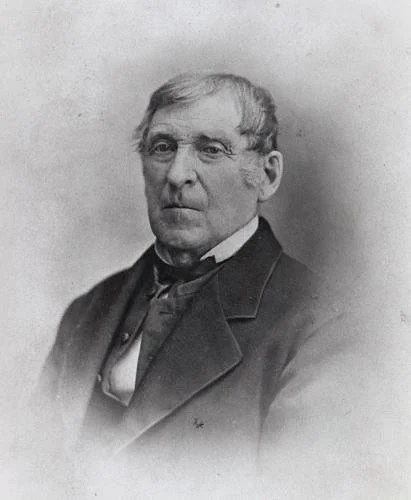

Rev. Leonard Hemenway Wheeler 1811-1872 (Photo: In Unnamed Wisconsin)

Bob Nelson recently contacted me with a treasure he transcribed from an 1872 copy of the Bayfield Press. For those who don’t know, Mr. Nelson is one of the top amateur historians in the Chequamegon area. He is on the board of the Bayfield Heritage Association, chairman of the Apostle Islands Historic Preservation Conservancy, and has extensively researched the history of Bayfield and the surrounding area.

The document itself is the obituary of Leonard Wheeler, the Congregational-Presbyterian minister who came to La Pointe as a missionary in 1841. Over the next quarter-century, spent mostly at Odanah where he founded the Protestant Mission, he found himself in the middle of the rapid social and political changes occurring in this area.

Generally, my impression of the missionaries has always tended to be negative. While we should always judge historical figures in the context of the times they lived in, to me there is something inherently arrogant and wrong with going among an unfamiliar culture and telling people their most-sacred beliefs are wrong. The Protestant missionaries, especially, who tended to demand conversion to white-American values along with conversion to Christianity, generally come off as especially hateful and racist in their writings on the Ojibwe and mix-blooded families of this area.

Leonard Wheeler, however, is one of my historical heroes. It’s true that he was like his colleagues Sherman Hall, William T. Boutwell, and Edmund Ely, in believing that practitioners of the Midewiwin and Catholicism were doomed to a fiery hell. He also believed in the superiority of white culture and education. However, in his writings, these beliefs don’t seem to diminish his acceptance of his Ojibwe neighbors as fellow human beings. This is something that isn’t always clear in the writings of the other missionaries.

Furthermore, Wheeler is someone who more than once stood up for justice and against corruption even when it brought him powerful enemies and endangered his health and safety. For this, he earned the friendship of some of the staunchest traditionalists among the Bad River leadership. He relocated to Beloit by the end of his life, but I am sure that Wheeler’s death in 1872 brought great sadness to many of the older residents of the Chequamegon Bay region and would have been seen as a significant event.

Therefore, I am very thankful to Bob Nelson for the opportunity to present this important document:

Reverend Leonard H. Wheeler

Missionary to the Ojibway

From the Beloit Free Press

Entered in the Bayfield Press

March 23, 1872

The recent death of Reverend Leonard H. Wheeler, for twenty-five years missionary to the Ojibway Indians on Lake Superior and for the last five and one half years a resident of Beloit, Wisconsin and known to many through his church and business relations, seems to call for some notice of his life and character through your paper.

Mr. Wheeler was born at Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, April 13, 1811. His mother dying during his infancy, he was left in charge of an aunt who with his father soon afterward removed to Bridgeport, Vermont, where the father still lives. At the age 17 he went first from home to reside with an uncle at Middlebury, Vermont. Here he was converted into the church in advance of both his father and uncle. His conversion was of so marked a character and was the occasion of such an awakening and putting forth of his mental and spiritual facilities that he and his friends soon began to think of the ministry as an appropriate calling. With this in view he entered Middlebury College in 1832, and soon found a home in the family of a Christian lady with whom he continued to reside until his graduation. For the kindly and elevating influences of that home and for the love that followed him afterwards, as if he had been a son, he was ever grateful. After his graduation he taught for a year or two before entering the theological seminary at Andover.

During his theological course the marked traits of character were developed which seem to have determined his future course. One was a deep sympathy with the wronged and oppressed; the other was conscious carefulness in settling his convictions and an un-calculating and unswerving firmness (under a gentle and quiet manner) in following such ripened convictions. These made him a staunch but a fanatical advocate of the enslaved, long before anti-slavery sentiments became popular. And thus was he moved to offer his services as a missionary to the Indians – relinquishing for that purpose his original plan to go on a mission to Ceylon. The turning point of his decision seems to have been the fact that for the service abroad men could readily be found, while few or none offer themselves to the more self-denying and unromantic business of civilizing and Christianizing the wild men within our own borders.

Harriet Wood Wheeler much later in life (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Reverend Wheeler found in Ms. Harriet Woods, of Lowell, Massachusetts, the spirit kindred with his own in these self-denying purposes and labors of love. There married on April 26, 1841, and June of that year they set out, and in August arrived at La Pointe – a fur trading post on Madeline Island in Lake Superior. They spent four years in learning the Ojibway language, in preaching and teaching, and in caring for the temporal and spiritual welfare of the Indians and half-breeds at that station. Their fur trading friends held out many inducements to remain at La Pointe but having become fully satisfied that the civilizing of the Indians required their removal to someplace where they might obtain lands and homes of their own; the Wheelers secured their removal to Odanah on the Bad River. Here the humble and slowly rewarded labors of the island were renewed with increased energy and hopefulness, and continued without serious interruption for seven years. Then, the white man’s greed, which has often dictated the policy of the government toward the Indians, and oftener defeated its wise and liberal intentions, clamored for their second removal to the Red Lake region, in Minnesota, and by forged petitions and misrepresentation, an order to this effect was obtained.

Mr. Wheeler’s spirit was stirred within him by these iniquitous proceedings, and he set himself calmly but resolutely to work to defeat the measure, even after it had been so far consummated. To make sure of his ground he explored the Red Lake region during the heat of midsummer. Becoming fully satisfied with the temptations to intemperance and other evil thereof, bonding would prove the room of this people. He made such strong and truthful representations of this matter (not without hazards to himself and his family) that the order was at last revoked. But the agitation and delays thus occasioned proved well nigh the ruin of the mission. For two years Mr. Wheeler without help from government, stood between his people and absolute starvation; and had at last the satisfaction of knowing that his course was fully approved. The year 1858 found the mission and Odanah almost prostrate again by unusual labors. Mrs. Wheeler was compelled by order of her physician to return to her eastern home for indispensable rest. Mr. Wheeler, worn by superintending the erection of buildings in addition to his preaching four times on the Sabbath and in other necessary cares and labors, also undertook a journey to the east to bring back his family and partly as a measure of relief to himself.

He started in March on snowshoes and traveled nearly 200 miles in that way. On his way he fell in with the band of Indians whose lands were about to be sold in violation of solemn treaties. He undertook their case and did not abandon it, yet visited Washington and obtained justice in their behalf. He reached Lowell, Massachusetts on his return from Washington, worn in body and mind, and with the severe cold firmly settled on his lungs. Trusting to an iron constitution to right it, he kept on preaching and visiting among his eastern friends. He then set out to return to his beloved people and his eastern home, trusting to find in a quiet journey by water the rest which had now become imperative. But he was not thus to be relieved. Soon after reaching home he was taken with violent hemorrhage and was ever after this a broken man.

Once again he asked to be relieved and a stronger man be sent in his place. But this was not done, and he continued to struggle on doing what he could until the fall of 1866, when the boarding school – which had been his right hand – was denied further support from the government. Mr. Wheeler’s strength not being equal to the task of obtaining for its support from other quarters, he retired from the mission, and he, with his family became residents of Beloit, and for these five years and more he has bravely battled with disease, and, for a sick man, has led a happy and withal useful life.

“ECLIPSE BELOIT:” Originally invented for the Odanah mission, Rev. Wheeler’s patent on the Eclipse Windmill brought wealth to his descendants (Wikimedia Images).

Mr. Wheeler had by nature something of that capacity for being self-reliant and patient, continuous thoughts which marks the inventor. Thrown upon his own resources for as much, and in need of a mill for grinding, he devised, while in his mission, a windmill for that purpose with improvements of his own. Unable to speak or preach as he was when he came among us, and incapacitated for continuous manual laborers, he busied himself with making drawings and a model of his previous invention. He obtained a patent, and with the aid of friends here began the manufacture of windmills. Thus has the sick man proved one of our most useful citizens, and established a business which we hope will do credit to his ingenuity and energy and be a source of substantial advantage to his family in the place.

Debilitated by the heat of last summer he took a journey to the east in September for his health, and to visit their aged parents. His health was for a time improved, but soon after his return hemorrhages began to appear, and after a long and trying sickness, borne with great cheerfulness and Christian resignation, he went to his rest on the Sabbath, February 25, 1872. During the delirium of his disease, and in his clear hours, his thoughts were much occupied with his former missionary cares and labors. Doing well to that people was evidently his ruling passion. It was a great joy in his last sickness to get news from there, to know that the boarding school had been revived and then some whom he had long worn upon his heart had become converts to Christ.

Thus has passed away one whose death will be severely limited by the people for whom he gave his life and whom he longed once more to visit. It will add not a little to the pleasure and richness of life’s recollections that we have known so true a fair and good a man. While we cherish his memory and follow his family with affectionate sympathy for his sake in their own, let us not overlook the simple faith, the utter integrity and soundness of soul which one for him such unbounded confidence from us and from all who knew him, and gave to his character so much gentleness blended with so much dignity and strength. He was an Israelite, indeed in who was no guile, a Nathaniel, given of God, prepared in a crystalline medium through which the light from heaven freely passed to gladden and to bless.

For more on Rev. Leonard Wheeler on this site, check out the People Index, or the Wheeler Papers category.

Leonard Wheeler’s original correspondence, journals, legal documents and manuscripts can be found in the Wheeler Family Papers at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center.

The book In Unnamed Wisconsin (1895) contains several incidents from Wheeler’s time at La Pointe and Odanah from the original writings of his widow, Harriet Wood Wheeler.

Finally, the article White Boy Grew Up Among the Chippewas from the Milwaukee Journal in 1931 is a nice companion to this obituary. The article, about Wheeler’s son William, sheds unique insight on what it was like to grow up as the child of a missionary. This article exists transcribed on the internet because of the efforts of Timm Severud, the outstanding amateur historian of the Barron County area. This is just one of many great stories uncovered by Mr. Severud, who passed away in 2010 at age 55.

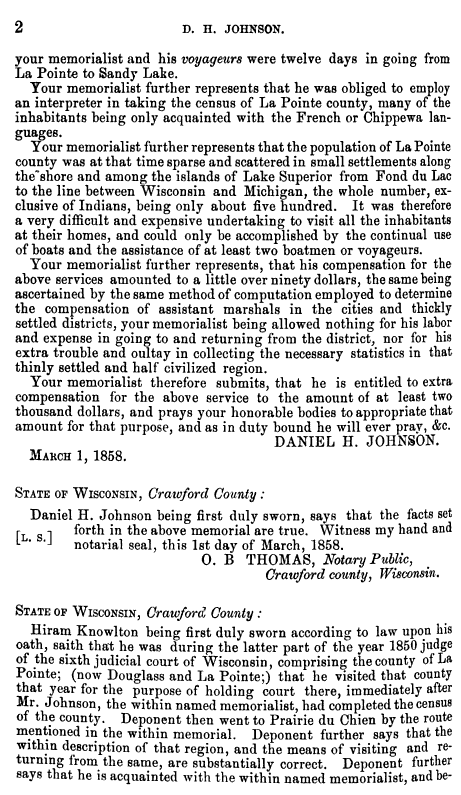

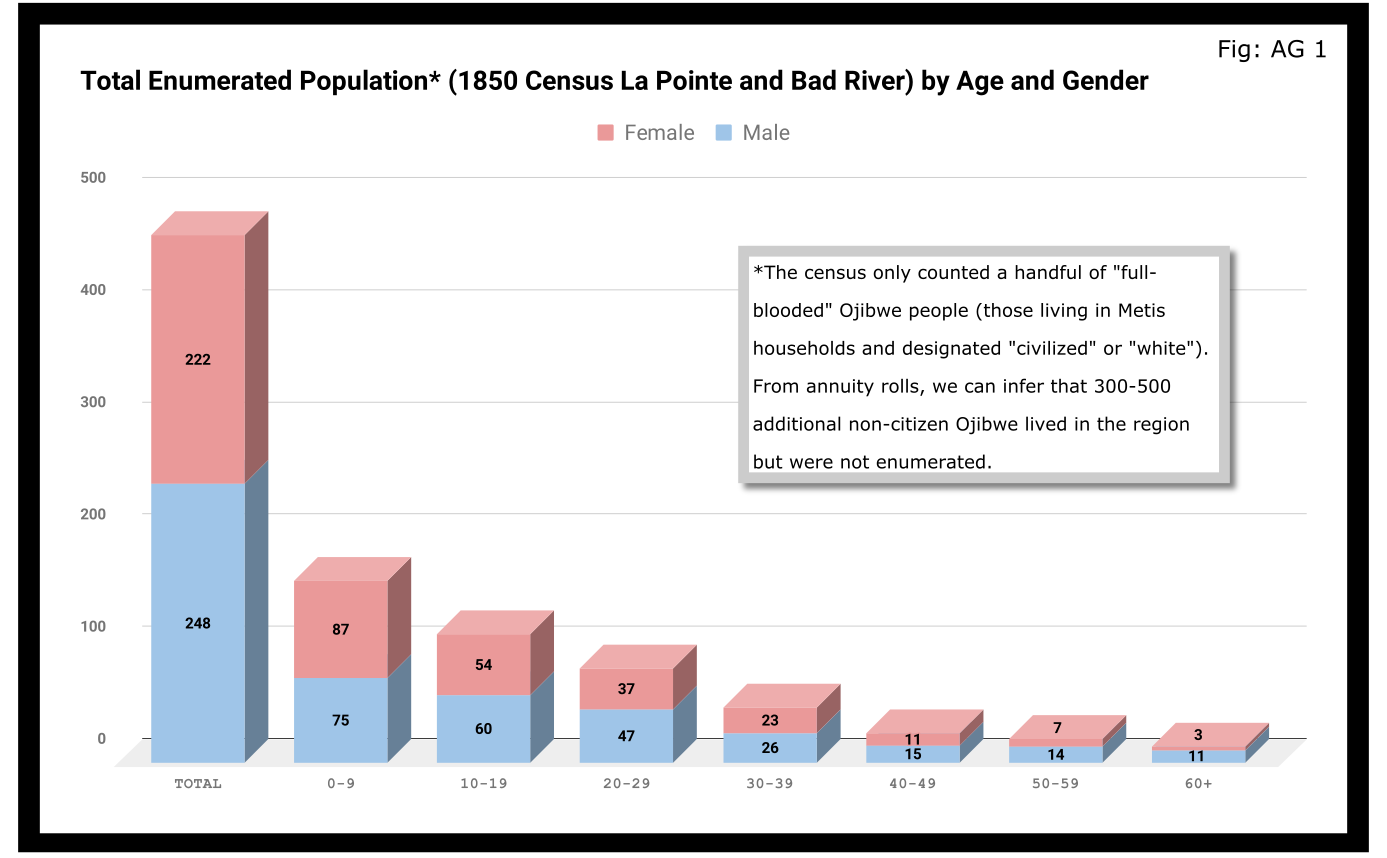

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his

![Group of people, including a number of Ojibwe at Minnesota Point, Duluth, Minnesota [featuring William Howenstein] ~ University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/howenstein-minnesota-point.jpg?w=300)