1842 Treaty Speeches at La Pointe in the News

May 15, 2024

Collected by Amorin Mello & edited by Leo Filipczak

Robert Stuart was a top official in Astor’s American Fur Company in the upper Great Lakes region. Apparently, it was not a conflict of interest for him to also be U.S. Commissioner for a treaty in which the Fur Company would be a major beneficiary.

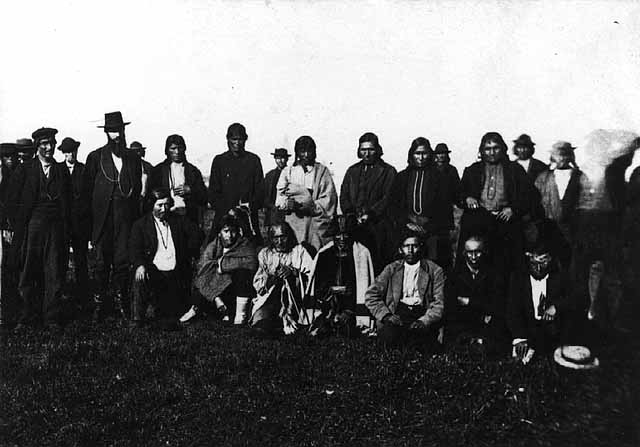

A gentleman who has recently returned from a visit to the Lake Superior Indian country, has furnished us with the particulars of a Treaty lately negotiated at La Pointe, during his sojourn at that place, by ROBERT STUART, Esq., Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the district of Michigan, on the part of the United States, and by the Chiefs and Braves of the Chippeway Indian nation on their own behalf and their people. From 3 to 4000 Indians were present, and the scene presented an imposing appearance. The object of the Government was the purchase of the Chippeway country for its valuable minerals, and to adopt a policy which is practised by Great Britain, i.e. of keeping intercourse with these powerful neighbors from year to year by paying them annuities and cultivating their friendship. It is a peculiar trait in the Indian character of being very punctual in regard to the fulfillment of any contract into which they enter, and much dissatisfaction has arisen among the different tribes toward our Government, in consequence of not complying strictly to the obligations on their part to the Indians, in the time of making the payments, for they are not generally paid until after the time stipulated in the treaty, and which has too often proven to be the means of losing their confidence and friendship.

On the 30th of September last, Mr. Stuart opened the Council, standing himself and some of his friends under an awning prepared for the occasion, and the vast assembly of the warlike Chippeways occupying seats which were arranged for their accommodation. A keg of Tobacco was rolled out and opened as a present to the Indians, and was distributed among them; when Mr. Stuart addressed them as follows:-

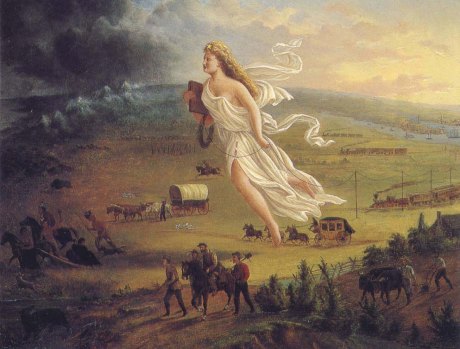

The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was a metaphor for infinite abundance in 1842. In less than 75 years, the species would be extinct. What that means for Stuart’s metaphor is hard to say (Biodiversity Heritage Library).

The chiefs who had been to Washington were the St. Croix chiefs Noodin (pictured below) and Bizhiki. They were brought to the capital as part of a multi-tribal delegation in 1824, which among other things, toured American military facilities.I am very glad to meet and shake hands with so many of my old friends in good health; last winter I visited your Great Father in Washington, and talked with him about you. He knows you are poor and have but little for your women and children, and that your lands are poor. He pities your condition, and has sent me here to see what can be done for you; some of your Bands get money, goods, and provisions by former Treaty, others get none because the Great Council at Washington did not think your lands worth purchasing. By the treaty you made with Gov. Cass, several years ago, you gave to your lands all the minerals; so the minerals belong no longer to you, and the white men are asking him permission to take the minerals from the land. But your Great Father wishes to pay you something for your lands and minerals before he will allow it. He knows you are needy and can be made comfortable with goods, provisions, and tobacco, some Farmers, Carpenters to aid in building your houses, and Blacksmiths to mend your guns, traps, &c., and something for schools to learn your children to read and write, and not grow up in ignorance. I hear you have been unpleased about your Farmers and Blacksmiths. If there is anything wrong I wish you would tell me, and I will write all your complaints to your Great Father, who is ever watchful over your welfare. I fear you do not esteem your teachers who come among you, and the schools which are among you, as you ought. Some of you seem to think you can learn as formerly, but do you not see that the Great Spirit is changing things all around you. Once the whole land was owned by you and other Indian Nations. Now the white men have almost the whole country, and they are as numerous as the Pigeons in the spring. You who have been in Washington know this; but the poor Indians are dying off with the use of whiskey, while others are sent off across the Mississippi to make room for the white men. Not because the Great Spirit loves the white men more than the Indians, but because the white men are wise and send their children to school and attend to instructions, so as to know more than you do. They become wise and rich while you are poor and ignorant, but if you send your children to school they may become wise like the white men; they will also learn to worship the Great Spirit like the whites, and enjoy the prosperity they enjoy. I hope, and he, that you will open your ears and hearts to receive this advice, and you will soon get great light. But said he, I am afraid of you, I see but few of you go to listen to the Missionaries, who are now preaching here every night; they are anxious that you should hear the word of the Great Spirit and learn to be happy and wise, and to have peace among yourselves.

The 1837 Treaty of St. Peters was mostly negotiated by Maajigaabaw or “La Trappe” of Leech Lake and other chiefs from outside the territory ceded by that treaty. The chiefs from the ceded lands were given relatively few opportunities to speak. This created animosity between the Lake Superior and Mississippi Bands.Your Great Father is very sorry to learn that there are divisions among his red children. You cannot be happy in this way. Your Great Father hopes you will live in peace together, and not do wrong to your white neighbors, so that no reports will be made against you, or pay demanded for damages done by you. These things when they occur displease him very much, and I myself am ashamed of such things when I hear them. Your Great Father is determined to put a stop to them, and he looks that the Chiefs and Braves will help him, so that all the wicked may be brought to justice; then you can hold up your heads, and your Great Father will be proud of you. Can I tell him that he can depend upon his Chippeway children acting in this way.

One other thing, your Great Father is grieved that you drink whiskey, for it makes you sick, poor, and miserable, and takes away your senses. He is determined to punish those men who bring whiskey among you, and of this I will talk more at another time.

Stuart would become irritated after the treaty when the Ojibwe argued they did not cede Isle Royale in 1842. This lead to further negotiations and an addendum in 1844. The Grand Portage Band, who lived closest to Isle Royale, was not party to the 1842 negotiations.When I was in New York about three moons ago I found 800 blankets which were due you last year, which by some mismanagement you did not get. Your Great Father was very angry about it, and wished me to bring them to you, and they will be given you at the payment. He is determined to see that you shall have justice done you, and to dismiss all improper agents. He despises all who would do you wrong. Now I propose to buy your lands from Fond du Lac, at the head of Lake Superior, down Lake Superior to Chocolate River near Grand Island, including all the Islands in the limits of the United States, in the Lake, making the boundary on Lake Superior about 250 miles in extent, and extending back into the country on Lake Superior about 100 miles. Mr. Stuart showed the Chiefs the boundary on the map, and said you must not suppose that your Great Father is very anxious to buy your lands, the principal object is the minerals, as the white people will not want to make homes upon them. Until the lands are wanted you will be permitted to live upon them as you now do. They may be wanted hereafter, and in this event your Great Father does not wish to leave you without a home. I propose that the Fond du Lac lands and the Sandy Lake tract (which embrace a tract 150 miles long by 100 miles deep) be left you for a home for all the bands, as only a small part of the Fond du Lac lands are to be included in the present purchase. Think well on the subject and counsel among yourselves, but allow no black birds to disturb you, your Great Father is now willing and can do you great good if you will, but if not you must take the consequences. To-morrow at the fire of the gun you can come to the Council ground and tell me whether the proposal I make in the name of your Great Father is agreeable to you; if so I will do what I can for you, you have known me to be your friend for many years. I would not do you wrong if I could, but desire to assist you if you allow me to do so. If you now refuse it will be long before you have another offer.

October 1st. At the sound of the Cannon the Council met, and when all were ready for business, Shingoop, the head Chief of the Fond du Lac band, with his 2d and 3d Chiefs, came forward and shook hands with the Commissioner and others associated with him, then spoke as follows:

Zhingob (Balsam), also known as Nindibens, signed the 1837, 1842, and 1854 treaties as chief or head chief of Fond du Lac. The Zhingob on earlier treaties is his father. See Ely, ed. Schenck, The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. ElyMy friend, we now know the purpose you came for and we don’t want to displease you. I am very glad there are so many Indians here to hear me. I wish to speak of the lands you want to buy of me. I don’t wish to displease the Traders. I don’t wish to displease the half-breeds; so I don’t wish to say at once, right off. I want to know what our Great Father will give us for them, then I will think and tell you what I think. You must not tell a lie, but tell us what our Great Father will give us for our lands. I want to ask you again, my Father. I want to see the writing, and who it is that gave our Great Father permission to take our minerals. I am well satisfied of what you said about Blacksmiths, Carpenters, Schools, Teachers, &c., as to what you said about whiskey, I cannot speak now. I do not know what the other Chiefs will say about it. I want to see the treaty and the name of the Chiefs who signed. The Chief answered that the Indians had been deceived, that they did not so understand it when they signed it.

Mr. Stuart replied that this was all talk for nothing, that the Government had a right to the minerals under former treaty, yet their Great Father wishes now to pay for the minerals and purchase their lands.

The Chief said he was satisfied. All shook hands again and the Chief retired.

The next Chief who came forward was the “Great Buffalo” Chief of the La Pointe band. Had heavy epaulettes on his shoulders and a hat trimmed with tinsel, with a heavy string of bear claws about his neck, and said:-

“Big Buffalo (Chippewa),” 1832-33 by Henry Inman, after J.O. Lewis (Smithsonian).

My father, I don’t speak for myself only, but for my Chiefs. What you said here yesterday when you called us your children, is what I speak about. I shall not say what the other Chief has said, that you have heard already.

He then made some remarks about the Missionaries who were laboring in their country and thought as yet, little had been done. About the Carpenters, he said, that he could not tell how it would work, as he had not tried it yet.

We have not decided yet about the Farmers, but we are pleased at your proposal about Blacksmiths. Can it be supposed that we can complete our deliberations in one night. We will think on the subject and decide as soon as we can.

The great Antonaugen Chief came next, observing the usual ceremony of shaking hands, and surrounded by his inferior Chiefs, said:-

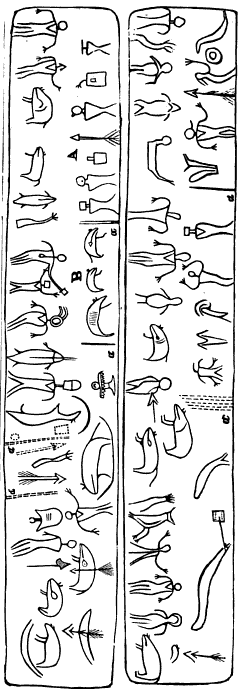

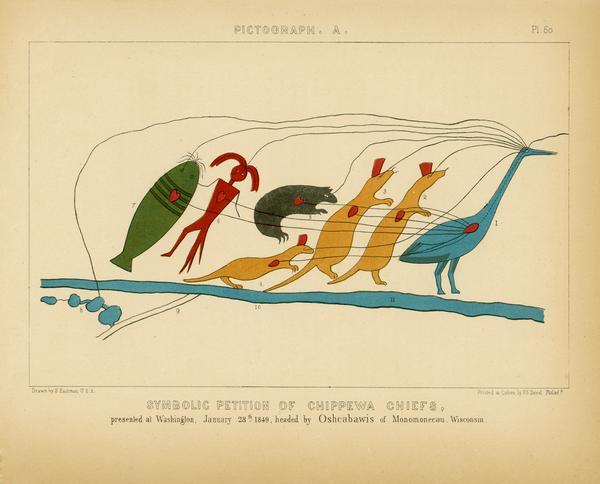

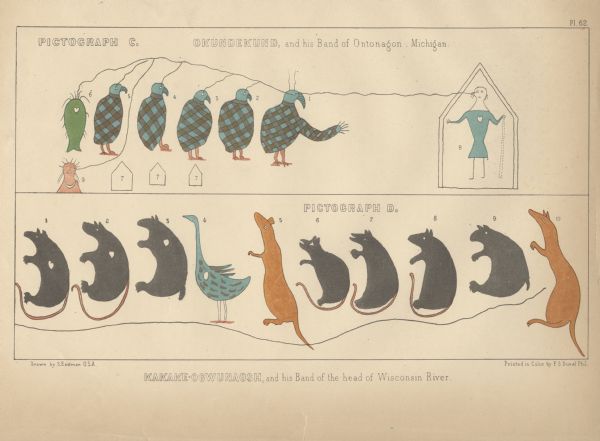

The great Ontonagon Chief is almost certainly Okandikan (Buoy), depicted here in a reproduction of an 1848 pictograph carried to Washington and reproduced by Seth Eastman. Okandikan is depicted as his totem symbol, the eagle (largest, with wing extended in the center of the image).

My father and all the people listen and I call upon my Great Father in Heaven to bear witness to the rectitude of my intentions. It is now five years since we have listened to the Missionaries, yet I feel that we are but children as to our abilities. I will speak about the lands of our band, and wish to say what is just and honorable in relation to the subject. You said we are your children. We feel that we are still, most of us, in darkness, not able fully to comprehend all things on account of our ignorance. What you said about our becoming enlightened I am much pleased; you have thrown light on the subject into my mind, and I have found much delight and pleasure thereby. We now understand your proposition from our Great Father the President, and will now wait to hear what our Great Father will give us for our lands, then we will answer. This is for the Antannogens and Ance bands.

Mr. Stuart now said, that he came to treat with the whole Chippeway Nation and look upon them all as one Nation, and said

I am much pleased with those who have spoken; they are very fine orators; the only difficulty is, they do not seem to know whether they will sell their lands. If they have not made up their minds, we will put off the Council.

Lac du Flambeau Chief, “the Great Crow,” came forward with the strict Indian formalities but had but little to say, as he did not come expecting to have any part in the treaty, but wished to receive his payment and go home.

The 2d Chief of this band wished to speak. He was painted red with black spots on each cheek to set off his beauty, his forehead was painted blue, and when he came to speak, he said:-

What the last Chief has said is all I have to say. We will wait to hear what your proposals are and will answer at a proper time.

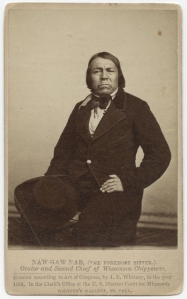

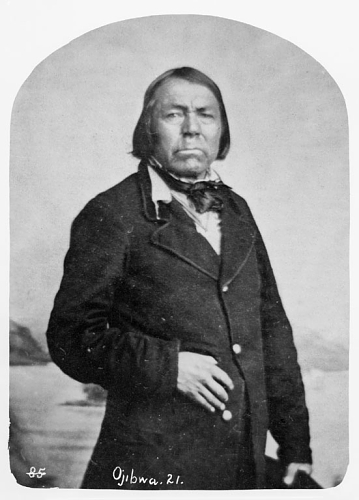

Next came forward “Noden,” or the “Great Wind,” Chief of the Mill Lac band, and said:-

Noodin (Wind) is mentioned here as representing the Mille Lacs Band, though his village was usually on Snake River of the St. Croix.

I have talked with my Great Father in Washington. It was a pity that I did not speak at the St. Peters treaty. My father, you said you had come to do justice. We do not wish to do injustice to our relations, the half-breeds, who are also our friends. I have a family and am in a hurry to get home, if my canoes get destroyed I shall have to go on foot. My father, I am hurry, I came for my payment. We have left our wives and children and they are impatient to have us return. We come a great distance and wish to do our business as soon as we can. I hope you will be as upright as our former agent. I am sorry not to see him seated with you. I fear it will not go as well as it would. I am hurry.

Mr Stuart now said that he considered them all one nation, and he wished to know whether they wished to sell their lands; until they gave this answer he could do nothing, and as it regards any thing further he could say nothing, and said they might now go away until Monday, at the firing of the Cannon they might come and tell him whether they would sell their country to their Great Father.

We intend giving the remainder of the proceedings of the treaty in our next.

Green Bay Republican:

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 1842, Page 2.

(Treaty with the Chippeways Concluded.)

Monday morning three guns were fired as a signal to open the Treaty. When all things were in readiness, Mr. Stuart said:

I am glad you have now had time for reflection, and I hope you are now ready like a band of brothers to answer the question which I have proposed. I want to see the Nation of one heart and of one mind.

Shingoop, Chief of the Fond du Lac band, came forward with full Indian ceremony, supported on each side by the inferior Chiefs. He addressed the Chippeway nation first, which was not fully interpreted; then he turned to the Commissioner and said:

in this Treaty which we are about to make, it is in my heart to say that I want our friends the traders, who have us in charge provided for. We want to provide also for our friends the half-breeds – we wish to state these preliminaries. Now we will talk of what you will give us for our country. There is a kind of justice to be done towards the traders and half-breeds. If you will do justice to us, we are ready to-morrow to sign the treaty and give up our lands. The 2d Chief of the band remarked, that he considered it the understanding that the half-breeds and traders were to be provided for.

The Great Buffalo, of La Pointe band, and his associate Chiefs came next, and the Buffalo said:

My Father, I want you to listen to what I say. You have heard what one Chief has said. I wish to say I am hurry on account of keeping so many men and women here away from their homes in this late season of the year, so I will say my answer is in the affirmative of your request; this is the mind of my Chiefs and braves and young men. I believe you are a correct man and have a heart to do justice, as you are sent here by our Great Father, the President. Father, our traders are so related to us that we cannot pass a winter without them. I want justice to be done them. I want you and our Great Father to assist us in doing them justice, likewise our half-breed children – the children of our daughters we wish provided for. It seems to me I can see your heart, and you are inclined to do so. We now come to the point for ourselves. We wish to know what you will give us for our country. Tell us, then we will advise with our friends. A part of the Antaunogens band are with me, the other part are turned Christians and gone with the Methodist band, (meaning the Ance band at Kewawanon) these are agreed in what I say.

The Bird, Chief of the Ance band, called Penasha, came forward in the usual form and said:

My Father, now listen to what I have to say. I agree with those who have spoken as far as our lands are concerned. What they say about our traders and half-breeds, I say the same. I speak for my band, they make use of my tongue to say what they would say and to express their minds. My Father, we listen to what you will offer for our country, then we will say what we have to say. We are ready to sell our country if your proposals are agreeable. All shook hands – equal dignity was maintained on each side – there was no inclination of the head or removing the hat – the Chiefs took their seats.

The White Crow next appeared to speak to the Great Father, and said:-

White Crow is apparently unaware that in the eyes of the United States, his lands, (Lac du Flambeau) were already sold five years earlier at St. Peters. Clearly, the notion of buying and selling land was not understood by him in the same way it was understood by Stuart.

Listen to what I say. I speak to the Great Father, to the Chiefs, Traders, and Half-breeds. You told us there was no deceit in what you say. You may think I am troublesome, but the way the treaty was made at St. Peters, we think was wrong. We want nothing of the kind again. We think you are a just man. You have listened to those Chiefs who live on Lake Superior. What I say is for another portion of country. It appears you are not anxious to buy the lands where I live, but you prefer the mineral country. I speak for the half-breeds, that they may be provided for: they have eaten out of the same dish with us: they are the children of our sisters and daughters. You may think there is something wrong in what I say. As to the traders, I am not the same mind with some. The old traders many years ago, charged us high and ought to pay us back, instead of bringing us in debt. I do not wish to provide for them; but of late years they have had looses and I wish those late debts to be paid. We do not consider that we sell our lands by saying we will sell them, so we consent to sell if your proposals are agreeable. We will listen and hear what they are.

Several others of the Chiefs spoke well on the subject, but the substance of all is contained in the above.

Hole-in-the-day, who is at once an orator and warrior, came forward; he had an Arkansas tooth pick in his hand which would weigh one or two pounds, and is evidently the greatest and most intelligent man in the nation, as fine a form of body, head and face, as perhaps could be found in any country.

Father, said he, I arise to speak. I have listened with pleasure to your proposal. I have come to tie the knot. I have come to finish this part of the treaty, and consent to sell our country if the offers of the President please us. Then addressing the Chiefs of the several bands he said, the knot is now tied, and so far the treaty is complete, not to be changed.

Zhaagobe (“Little” Six) signed as first chief from Snake River, and he is almost certainly the “Big Six” mentioned here. Several Ojibwe and Dakota chiefs from that region used that name (sometimes rendered in Dakota as Shakopee).

Big Six now addressed the whole Nation in a stream of eloquence which called down thunders of applause; he stands next to Hole-in-the-day in consequence and influence in the nation. His motions were graceful, his enunciation rather rapid for a fine speaker. He evidently possesses a good mind, though in person and form he is quite inferior to Hole-in-the-day. His speech was not interpreted, but was said to be in favor of selling the Chippeway country if the offer of the Government should meet their expectations, and that he took a most enlightened view of the happiness which the nation would enjoy if they would live in peace together and attend to good counsel.

Mr. Stuart now said,

I am very happy that the Chippewa nation are all of one mind. It is my great desire that they should continue to for it is the only way for them to be happy and wise. I was afraid our “White Crow” was going to fly away, but am happy to see him come back to the flock, so that you are all now like one man. Nothing can give me greater pleasure than to do all for you I can, as far as my instructions from your Great Father will allow me. I am sorry you had any cause to complain of the treaty at St. Peters. I don’t believe the Commissioner intended to do you wrong, but perhaps he did not know your wants and circumstances so as to suit. But in making this treaty we will try to reconcile all differences and make all right. I will now proceed to offer you all I can give you for your country at once. You must not expect me to alter it, I think you will be pleased with the offer. If some small things do not suit you, you can pass them over. The proposal I now make is better than the Government has given any other nation of Indians for their lands, when their situations are considered. Almost double the amount paid to the Mackinaw Indians for their good lands. I offer more than I at first intended as I find there are so many of you, and because I see you are so friendly to our Government, and on account of your kind feelings for the traders and half-breeds, and because you wish to comply with the wishes of your Great Father, and because I wish to unite you all together. At first I thought of making your annuities for only twenty years but I will make them twenty-five years. For twenty-five years I will offer you the following and some items for one year only.

$12,500 in specie each year for 25 years, $312,500

10,500 in goods ” ” ” ” ” 262,500

2,000 in provisions and tobacco, do. 50,000$625,000

This amount will be connected with the annuity paid to a part of the bands on the St. Peters treaty, and the whole amount of both treaties will be equally distributed to all the bands so as to make but one payment of the whole, so that you will be but one nation, like one happy family, and I hope there will be no bad heart to wish it otherwise. This is in a manner what you are to get for your lands, but your Great Father and the great Council at Washington are still willing to do more for you as I will now name, which you will consider as a kind of present to you, viz:

2 Blacksmiths, 25 years, $2000, $50,000

2 Farmers, ” ” 1200, 30,000

2 Carpenters, ” ” 1200, 30,000

For Schools, ” ” 2000, 50,000

For Plows, Glass, Nails, &c. for one year only, 5000

For Credits for one year only, 75,000

For Half-breeds ” ” ” 15,000$255,000

Total $880,000

With regards to the claims. I will not allow any claim previous to 1822; none which I deem unjust or improper. I will endeavor to do you justice, and if the $75,000 is not all required to pay your honest debts, the balance shall be paid to you; and if but a part of your debts are paid your Great Father requires a receipt in full, and I hope you will not get any more credits hereafter. I hope you have wisdom enough to see that this is a good offer. The white people do not want to settle on the lands now and perhaps never will, so you will enjoy your lands and annuities at the same time. My proposal is now before you.

The Fond du Lac Chief said, we will come to-morrow and give our answer.

October 4th, Mr. Stuart opened the Council.

Clement Hudon Beaulieu, was about thirty at this time and working his way up through the ranks of the American Fur Company at the beginning of what would be a long and lucrative career as an Ojibwe trader. His influence would have been very useful to Stuart as he was a close relative of Chief Gichi-Waabizheshi. He may have also been related to the Lac du Flambeau chiefs–though probably not a grandson of White Crow as some online sources suggest.

We have now met said he, under a clear sun, and I hope all darkness will be driven away. i hope there is not a half-breed whose heart is bad enough to prevent the treaty, no half-breed would prevent he treaty unless he is either bad at heart or a fool. But some people are so greedy that they are never satisfied. I am happy to see that there is one half-breed (meaning Mr. Clermont Bolio) who has heart enough to advise what is good; it is because he has a good heart, and is willing to work for his living and not sponge it out of the Indians.

We now heard the yells and war whoops of about one hundred warriors, ornamented and painted in a most fantastic manner, jumping and dancing, attended with the wild music usual in war excursions. They came on to the Council ground and arrested for a time the proceedings. These braves were opposed to the treaty, and had now come fully determined to stop the treaty and prevent the Chiefs from signing it. They were armed with spears, knives, bows and arrows, and had a feather flag flying over ten feet long. When they were brought to silence, Mr. Stuart addressed them appropriately and they soon became quiet, so that the business of the treaty proceeded. Several Chiefs spoke by way of protecting themselves from injustice, and then all set down and listened to the treaty, and Mr. Stuart said he hoped they would understand it so as to have no complaints to make afterwards.

The provisions of the treaty are the same as made in the proposals as to the amount and the manner of payment. The Indians are to live on the lands until they are wanted by the Government. They reserve a tract called the Fond du Lac and Sandy Lake country, and the lands purchased are those already named in the proposals. The payment on this treaty and that of the St. Peters treaty are to be united, and equal payments made to all the bands and families included in both treaties. This was done to unite the nation together. All will receive payments alike. The treaty was to be binding when signed by the President and the great Council at Washington. All the Chiefs signed the treaty, the name of Hole-in-the-day standing at the head of the list, and it is said to be the greatest price paid for Indian lands by the United States, their situation considered, though the minerals are said to be very valuable.

The Commissioner is said to have conducted the treaty in a very just, impartial and honorable manner, and the Indians expressed the kindest feelings towards him, and the greatest respect for all associated with him in negotiating the treaty and the best feelings towards their Agent now about leaving the country, and for the Agents of the American Fur Company and for the traders. The most of them expressed the warmest kind of feelings toward the Missionaries, who had come to their country to instruct them out of the word of the Great Spirit. The weather was very pleasant, and the scene presented was very interesting.

Among The Otchipwees: III

July 20, 2016

By Amorin Mello

… continued from Among The Otchipwees: II

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 4 February 1885

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 335-342.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

III.

The Northern tribes have nothing deserving the name of historical records. Their hieroglyphics or pictorial writings on trees, bark, rocks and sheltered banks of clay relate to personal or transient events. Such representations by symbols are very numerous but do not attain to a system.

Their history prior to their contact with the white man has been transmitted verbally from generation to generation with more accuracy than a civilized people would do. Story-telling constitutes their literature. In their lodges they are anything but a silent people. When their villages are approached unawares, the noise of voices is much the same as in the camps of parties on pic-nic excursions. As a voyageur the pure blood is seldom a success, and one of the objections to him is a disposition to set around the camp-fire and relate his tales of war or of the hunt, late into the night. This he does with great spirit, “suiting the action to the word” with a varied intonation and with excellent powers of description. Such tales have come down orally from old to young many generations, but are more mystical than historical. The faculty is cultivated in the wigwam during long winter nights, where the same story is repeated by the patriarchs to impress it on the memory of the coming generation. With the wild man memory is sharp, and therefore tradition has in some cases a semblance to history. In substance, however, their stories lack dates, the subjects are frivolous or merely romantic, and the narrator is generally given to embellishment. He sees spirits everywhere, the reality of which is accepted by the child, who listens with wonder to a well-told tale, in which he not only believes, but is preparing to be a professional story-teller himself.

Indian picture-writings and inscriptions, in their hieroglyphics, are seen everywhere on trees, rocks and pieces of bark, blankets and flat pieces of wood. Above Odanah, on Bad River, is a vertical bank of clay, shielded from storms by a dense group of evergreens. On this smooth surface are the records of many generations, over and across each other, regardless of the rights of previous parties. Like most of their writings, they relate to trifling events of the present, such as the route which is being traveled; the game killed; or the results of a fight. To each message the totem or dodem of the writer is attached, by which he is at once recognized. But there are records of some consequence, though not strictly historical.

Charles Whittlesey also reproduced Okandikan’s autobiography in Western Reserve Historical Society Tract 41.

Before a young man can be considered a warrior, he must undergo an ordeal of exposure and starvation. He retires to a mountain, a swamp, or a rock, and there remains day and night without food, fire or blankets, as long as his constitution is able to endure the exposure. Three or four days is not unusual, but a strong Indian, destined to be a great warrior, should fast at least a week. One of the figures on this clay bank is a tree with nine branches and a hand pointing upward. This represents the vision of an Indian known to one of my voyagers, which he saw during his seclusion. He had fasted nine days, which naturally gave him an insight of the future, and constituted his motto, or chart of life. In tract No. 41 (1877), of the Western Reserve Historical Society, I have represented some of the effigies in this group; and also the personal history of Kundickan, a Chippewa, whom I saw in 1845, at Ontonagon. This record was made by himself with a knife, on a flat piece of wood, and is in the form of an autobiography. In hundreds of places in the United States such inscriptions are seen, of the meaning of which very little is known. Schoolcraft reproduced several of them from widely separated localities, such as the Dighton Boulder, Rhode Island; a rock on Kelley’s Island, Lake Erie, and from pieces of birch bark, conveying messages or memoranda to aid an orator in his speeches.

~ New Sources of Indian History, 1850-1891: The Ghost Dance and the Prairie Sioux, A Miscellany by Stanley Vestal, 2015, page 269.

The “Indian rock” in the Susquehanna River, near Columbia, Pennsylvania; the God Rock, on the Allegheny, near Brady’s Bend; inscriptions on the Ohio River Rocks, near Wellsville, Ohio, and near the mouth of the Guyandotte, have a common style, but the particular characters are not the same. Three miles west of Barnsville, in Belmont County, Ohio, is a remarkable group of sculptured figures, principally of human feet of various dimensions and uncouth proportions. Sitting Bull gave a history of his exploits on sheets of paper, which he explained to Dr. Kimball, a surgeon in the army, published in fascimile in Harper’s Weekly, July 1876. Such hieroglyphics have been found on rocky faces in Arizona, and on boulders in Georgia.

Pointe De Froid is the northwestern extremity of La Pointe on Madeline Island. Map detail from 1852 PLSS survey.

~ Report of a geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota: and incidentally of a portion of Nebraska Territory, by David Dale Owen, 1852, page 420.

~ Geology of Wisconsin: Paleontology by R. P. Whitfield, 1880, page 58.

While pandemonium was let loose at La Pointe towards the close of the payment we made a bivouac on the beach, between the dock and the mission house. The voyageurs were all at the great finale which constitutes the paradise of a Chippewa. One of my local assistants was playing the part of a detective on the watch for whisky dealers. We had seen one of them on the head waters of Brunscilus River, who came through the woods up the Chippewa River. Beyond the village of La Pointe, on a sandy promontory called Pointe au Froid, abbreviated to Pointe au Fret or Cold Point, were about twenty-five lodges, and probably one hundred and fifty Indians excited by liquor. For this, diluted with more than half water, they paid a dollar for each pint, and the measure was none too large – neither pressed down nor running over. Their savage yells rose on the quiet moon-lit atmosphere like a thousand demons. A very little weak whisky is sufficient to work wonders in the stomach of a backwoods Indian, to whom it is a comparative stranger. About midnight the detective perceived our traveler from the Chippewa River quietly approaching the dock, to which he tied his canoe and went among the lodges. To the stern there were several kegs of fire-water attached, but weighted down below the surface of the water. It required but a few minutes to haul them in and stave the heads of all of them. Before morning there appeared to be more than a thousand savage throats giving full play to their powerful lungs. Two of them were staggering along the beach toward where I lay, with one man by my side. he said we had better be quiet, which, undoubtedly, was good advice. They were nearly naked, locked arm in arm, their long hair spread out in every direction, and as they swayed to and fro between the water line and the bushes, no imagination could paint a more complete representation of the demon. There was a yell to every step – apparently a bacchanalian song. They were within two yards before they saw us, and by one leap cleared everything, as though they were as much surprised as we were. The song, or howl, did not cease. It was kept up until they turned away from the beach into the mission road, and went on howling over the hill toward the old fort. It required three days for half-breed and full-blood alike to recover from the general debauch sufficiently to resume the oar and pack. As we were about to return to the Penoka Mountains, a Chippewa buck, with a new calico shirt and a clean blanket, wished to know if the Chemokoman would take him to the south shore. He would work a paddle or an oar. Before reaching the head of the Chegoimegon Bay there was a storm of rain. He pulled off his shirt, folded it and sat down upon it, to keep it dry. The falling rain on his bare back he did not notice.

Portrait of Stephen Bonga

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

We had made the grand portage of nine miles from the foot of the cataract of the St. Louis, above Fond du Lac, and encamped on the river where the trail came to it below the knife portage. In the evening Stephen Bungo, a brother of Charles Bungo, the half-breed negro and Chippewa, came into our tent. He said he had a message from Naugaunup, second chief of the Fond du Lac band, whose home as at Ash-ke-bwau-ka, on the river above. His chief wished to know by what authority we came through the country without consulting him. After much diplomatic parley Stephen was given some pequashigon and went to his bivouac.

Joseph Granville Norwood

~ Wikipedia.org

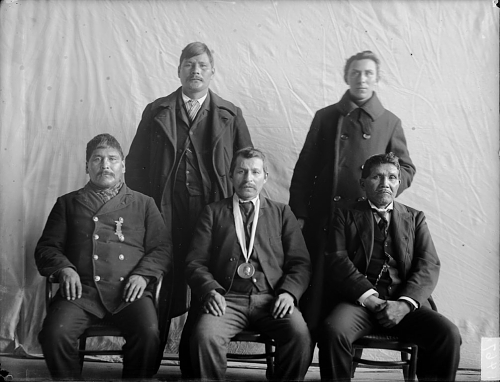

Portrait of Naagaanab

~ Minnesota Historical Society

The next morning he intimated that we must call at Naugaunup’s lodge on the way up, where probably permission might be had, by paying a reasonable sum, to proceed. We found him in a neat wigwam with two wives, on a pleasant rise of the river bluff, clear of timber, where there had been a village of the same name. His countenance was a pleasant one, very closely resembling that of Governor Corwin, of Ohio, but his features were smaller and also his stature. Dr. Norwood informed him that we had orders from the Great Father to go up the St. Louis to its source, thence to the waters running the other way to the Canada line. Nothing but force would prevent us from doing this, and if he was displeased he should make a complaint to the Indian agent at La Pointe, and he would forward it to Washington. We heard no more of the invasion of his territory, and he proceeded to do what very few Chippewas will do, offered to show us valuable minerals. In the stream was a pinnacle of black sale, about sixty feet high. Naugaunup soon appeared from behind it, near the top, in a position that appeared to be inaccessible, a very picturesque object pointing triumphantly to some veins of white quartz, which are very common in metamorphic slate.

Those who have heard him, say that he was a fine orator, having influence over his band, a respectable Indian, and a good negotiator. If he imagined there was value in those seams of quartz it is quite remarkable and contrary to universal practice among Chippewas that he should show them to white men. They claim that all minerals belong to the tribe. An Indian who received a price for showing them, and did not give every one his share, would be in danger of his life. They had also a superstitious dread of some great evil if they disclosed anything of the kind. Some times they promise to do so, but when they arrive at the spot, with some verdant white man, expecting to become suddenly rich, the Great Spirit or the Bad Manitou has carried it away. I have known more than one such instance, where persons have been sustained by hopeful expectation after many days of weary travel into the depths of the forest. The editor of the Ontonagon Miner gives one of the instances in his experience:

“Many years ago when Iron River was one of the fur stations, of John Jacob Astor and the American Fur Company, the Indians were known to have silver in its native state in considerable quantities.”

Men are now living who have seen them with chunks of the size of a man’s fist, but no one ever succeeded in inducing them to tell or show where the hidden treasure lay. A mortal dread clung to them, that if they showed white men a deposit of mineral the Great Manitou would punish them with death.

Several years since a half-breed brought in very fine specimens of vein rock, carrying considerable quantities of native silver. His report was that his wife had found it on the South Range, where they were trapping. To test his story he was sent back for more. In a few days he returned bringing with him quite a chunk from which was obtained eleven and one-half ounces of native silver. He returned home, went among the Flambeaux Indians and was killed. His wife refused to listen to any proposals or temptation from friend or foe to show the location of this vein, clinging with religious tenacity to the superstitious fears of her tribe.

When the British had a fort on St. Joseph’s Island in the St. Mary’s River, in the War of 1812, an Indian brought in a rich piece of copper pyrites. The usual mode of getting on good terms with him, by means of whisky, failed to get from him the location of the mineral. Goods were offered him; first a bundle, then a pile, afterwards a canoe-load, and finally enough to load a Mackinaw boat. No promise to disclose the place, no description or hint could be extorted. It was probably a specimen from the veins on the Bruce or Wellington mining property, only about twenty miles distant on the Canadian shore.

Detail of John Beargrease the Younger from stereograph “Lake Superior winter mail line” by B. F. Childs, circa 1870s-1880s.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

Crossing over the portage from the St. Louis River to Vermillion River, one of the voyageurs heard the report of a distant shot. They had expected to meet Bear’s Grease, with his large family, and fired a gun as a signal to them. The ashes of their fire were still warm. After much shouting and firing, it was evident that we should have no Indian society at that time. That evening, around an ample camp fire, we heard the history of the old patriarch. His former wives had borne him twenty-four children; more boys than girls. Our half-breed guide had often been importuned to take one of the girls. The old father recommended her as a good worker, and if she did not work he must whip her. Even a moderate beating always brought her to a sense of her duties. All he expected was a blanket and a gun as an offset. He would give a great feast on the occasion of the nuptials. Over the summit to Vermillion, through Vermillion Lake, passing down the outlet among many cataracts to the Crane Lake portage, there were encamped a few families, most of them too drunk to stand alone. There were two traders, from the Canada side, with plenty of rum. We wanted a guide through the intricacies of Rainy Lake. A very good-looking savage presented himself with a very unsteady gait, his countenance expressing the maudlin good nature of Tam O’Shanter as he mounted Meg. Withal, he appeared to be honest. “Yes, I know that way, but, you see, I’m drunk; can’t you wait till to-morrow.” A young squaw who apparently had not imbibed fire-water, had succeeded in acquiring a pewter ring. Her dress was a blanket of rabbit skins, made of strips woven like a rag carpet. It was bound around her waist with a girdle of deer’s hide, answering the purpose of stroud and blanket. No city belle could exhibit a ring of diamonds more conspicuously and with more self-satisfaction than this young squaw did her ring of pewter.

As we were all silently sitting in the canoes, dripping with rain, a sudden halloo announced the approach of living men. It was no other than Wau-nun-nee, the chief of the Grand Fourche bands, who was hunting for ducks among the rice. More delicious morsels never gladdened the palate than these plump, fat, rice-fed ducks. Old Wau-nun-nee is a gentleman among Indian chiefs. His band had never consented to sell their land, and consequently had no annuities. He even refused to receive a present from the Government as one of the head men of the tribe, preferring to remain wholly independent. We soon came to his village on Ash-ab-ash-kaw Lake. No band of Indians in our travels appeared as comfortable or behaved as well as this. Their country is well supplied with rice and tolerably good hunting ground. The American fur dealers (I mean the licensed ones) do not sell liquor to the Indians, and use their influence to aid Government in keeping it from them. Wau-nun-nee’s baliwick was seldom disturbed by drunken brawls. His Indians had more pleasant countenances than any we had seen, with less of the wild and haggard look than the annuity Indians. It was seldom they left their grounds, for they seldom suffered from hunger. They were comfortably clothed, made no importunities for kokoosh or pequashigon, and in gratifying their savage curiosity about our equipments they were respectful and pleasant. In his lodge the chief had teacups and saucers, with tea and sugar for his white guests, which he pressed us to enjoy. But we had no time for ceremonials, and had tea and sugar of our own. Our men recognized numerous acquaintances among the women, and as we encamped near a second village at Round Lake they came to make a draft on our provision chest. We here laid in a supply of wild rice in exchange for flour. Among this band we saw bows and arrows used to kill game. They have so little trade with the whites, and are so remote from the depots of Indian goods, that powder and lead are scarce, and guns also. For ducks and geese the bow and arrow is about as effectual as powder and shot. In truth, the community of which Wau-nun-nee was the patriarch came nearer to the pictures of Indians which poets are fond of drawing than any we saw. The squaws were more neatly clad, and their hair more often combed and braided and tied with a piece of ribbon or red flannel, with which their pappooses delighted to sport. There were among them fewer of those distinguished smoke-dried, sore-eyed creatures who present themselves at other villages.

By my estimate the channel, as we followed it to the head of the Round Lake branch, is two hundred and two mile in length, and the rise of the stream one hundred and eight feet. The portage to a stream leading into the Mississippi is one mile.

At Round Lake we engaged two young Indians to help over the portage in Jack’s place. Both of them were decided dandies, and one, who did not overtake us till late the next morning, gave an excuse that he had spent the night in courting an Indian damsel. This business is managed with them a little differently than with us. They deal largely in charms, which the medicine men furnish. This fellow had some pieces of mica, which he pulverized, and was managing to cause his inamorata to swallow. If this was effected his cause was sure to succeed. He had also some ochery, iron ore and an herb to mix with the mica. Another charm, and one very effectual, is composed of a hair from the damsel’s head placed between two wooden images. Our Lothario had prepared himself externally so as to produce a most killing effect. His hair was adorned with broad yellow ribbons, and also soaked in grease. On his cheeks were some broad jet black stripes that pointed, on both sides, toward his mouth; in his ears and nose, some beads four inches long. For a pouch and medicine bag he had the skin of a swan suspended from his girdle by the neck. His blanket was clean, and his leggings wrought with great care, so that he exhibited a most striking collection of colors.

At Round Lake we overtook the Cass Lake band on their return from the rice lakes. This meeting produced a great clatter of tongues between our men and the squaws, who came waddling down a slippery bank where they were encamped. There was a marked difference between these people and those at Ash-ab-ash-kaw. They were more ragged, more greasy, and more intrusive.

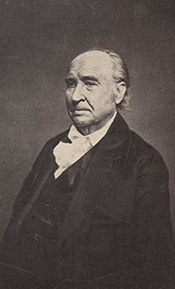

CHARLES WHITTLSEY.

Colonel Charles Whittlesey

May 27, 2016

By Amorin Mello

C.C. Baldwin was a friend, colleague, and biographer of Charles Whittlesey.

~ Memorial of Charles Candee Baldwin, LL. D.: Late President of the Western Reserve Historical Society, 1896, page iii.

This is a reproduction of Colonel Charles Whittlesey’s biography from the Magazine of Western History, Volume V, pages 534-548, as published by his successor Charles Candee Baldwin from the Western Reserve Historical Society. This biography provides extensive and intimate details about the life and profession of Whittlesey not available in other accounts about this legendary man.

Whittlesey came to Lake Superior in 1845 while working for the Algonquin Mining Company along the Keweenaw Peninsula’s copper region. His first trip to Chequamegon Bay appears to have been in 1849 while doing do a geological survey of the Penokee Mountains for David Dale Owen. Whittlesey played a dramatic role in American settlement of the Chequamegon Bay region. Whittlesey convinced his brother, Asaph Whittlesey Jr., to move from the Western Reserve in 1854 establish what became the City of Ashland at the head of Chequamegon Bay as a future port town for extracting and shipping minerals from the Penokee Mountains. Whittlesey’s influence can still be witnessed to this day through local landmarks named in his honor:

Whittlesey published more than two hundred books, pamphlets, and articles. For additional research resources, the extensive Charles Whittlesey Papers are available through the Western Reserve Historical Society in two series:

Magazine of Western History, Volume V, pages 534-548.

COLONEL CHARLES WHITTLESEY.

Map of the Connecticut Western Reserve in Ohio by William Sumner, September 1826.

~ Cleveland Public Library

![Asaph Whittlesey [Sr], Late of Tallmadge, Summit Co., Ohio by Vesta Hart Whittlesey and Susan Everett Whittlesey, né Fitch, 1872.](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/asaph-whittlesey-vesta-hart.jpg?w=186&h=300)

[Father] Asaph Whittlesey [Sr], Late of Tallmadge, Summit Co., Ohio by [mother] Vesta Hart Whittlesey [posthumously] and [stepmother] Susan Everett Whittlesey, né Fitch, 1872.

~ Archive.org

War was then in the west, and his neighbors feared they might be the victims of the scalping knife. But the danger was different. In passing the Narrows, between Pittsburgh and Beaver, the wagon ran off a bank and turned completely over on the wife and children. They were rescued and revived, but the accident permanently impaired the health of Mr. Whittlesey.

Mr. Whittlesey was in Tallmadge, justice of the peace from soon after his arrival till near the close of his life, and postmaster from 1814, when the office was first established, to his death. He was again severely injured, but a strong constitution and unflinching will enabled him to accomplish much. He had a store, buying goods in Pittsburgh and bringing them in wagons to Tallmadge; and an ashery; and in 1818 he commenced the manufacture of iron on the Little Cuyahoga, below Middlebury.

The times were hard, tariff reduced, and in 1828 he returned to his farm prematurely old. He died in 1842. Says General Bierce,

“His intellect was naturally of a high order, his religious convictions were strong and never yielded to policy or expediency. He was plain in speech, sometimes abrupt. Those who respected him were more numerous than those who loved him. But for his friends, no one had a stronger attachment. His dislikes were not very well concealed or easily removed. In short, he was a man of strong mind, strong feelings, strong prejudices, strong affections and strong attachments, yet the whole was tempered with a strong sense of justice and strong religious feelings.”

[Uncle] Elisha Whittlesey

~ Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

Portrait of Reverend David Bacon from ConnecticutHistory.org:

“David Bacon (1771 – August 27, 1817) was an American missionary in Michigan Territory. He was born in Woodstock, Connecticut. He worked primarily with the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes, although they were not particularly receptive to his Christian teachings. He founded the town of Tallmadge, Ohio, which later became the center of the Congregationalist faith in Ohio.”

~ Wikipedia.org

Tallmadge was settled in 1808 as a religious colony of New England Congregationalists, by a colony led by Rev. David Bacon, a missionary to the Indians. This affected the society in which the boy lived, and exercised much influence on the morality of the town and the future of its children, one of whom was the Rev. Leonard Bacon. Rev. Timlow’s History of Southington says, “Mr. Whittlesey moved to Tallmadge, having become interested in settling a portion of Portage county with Christian families.” And that he was a man “of surpassing excellence of character.”

If it should seem that I have dwelt upon the parents of Colonel Whittlesey, it is because his own character and career were strongly affected by their characters and history. Charles, the son, combined the traits of the two. He commenced school at four years old in Southington; the next year he attended the log school house at Tallmadge until 1819, when the frame academy was finished and he attended it in winter, working on the farm in summer until he was nineteen.

The boy, too, saw early life on foot, horseback and with ox-teams. He found the Indians still on the Reserve, and in person witnessed the change from savage life and new settlements, to a state of three millions of people, and a large city around him. One of Colonel Whittlesey’s happiest speeches is a sketch of log cabin times in Tallmadge, delivered at the semi-centennial there in 1857.

~ Annual Report on the Geological Survey of the State of Ohio: 1837 by Ohio Geologist William Williams Mather, 1838, page 22.

In 1827 the youngster became a cadet at West Point. Here he displayed industry, and in some unusual incidents there, coolness and courage. He graduated in 1831, and became brevet second lieutenant in the Fifth United States infantry, and in November started to join his regiment at Mackinaw. He did duty through the winter with the garrison at Fort Gratiot. In the spring he was assigned at Green Bay to the company of Captain Martin Scott, so famous as a shot. At the close of the Black Hawk War he resigned from the army. Though recognizing the claim of the country to the services of the graduates of West Point, he tendered his services to the government during the Seminole Mexican war. By a varied experience his life thereafter was given to wide and general uses. He at first opened a law office in Cleveland, Ohio, and was fully occupied in his profession, and as part owner and co-editor of the Whig and Herald until the year 1837. He was that year appointed assistant geologist of the state of Ohio. Through very uneconomical economy, the survey was discontinued at the end of two years, when the work was partly done and no final reports had been made. Of course most of the work and its results were lost. Great and permanent good indeed resulted to the material wealth of the state, in disclosing the rich coal and iron deposit of southeastern Ohio, thus laying the foundation for the vast manufacturing industries which have made that portion of the state populous and prosperous. The other gentlemen associated with him were Professor William Mather as principal; Dr. Kirtland was entrusted with natural history. Others were Dr. S. P. Hildreth, Dr. Caleb Briggs, Jr., Professor John Locke and Dr. J. W. Foster. It was an able corps, and the final results would have been very valuable and accurate. In 1884, Colonel Whittlesey was sole survivor and said in this Magazine:

“Fifty years since, geology had barely obtained a standing among the sciences even in Europe. In Ohio it was scarcely recognized. The state at that time was more of a wilderness than a cultivated country, and the survey was in progress little more than two years. It was unexpectedly brought to a close without a final report. No provision was made for the preservation of papers, field notes and maps.”

Report of Progress in 1869, by J. S. Newberry, Chief Geologist, by the Geological Survey of Ohio, 1870.

Professor Newbury, in a brief resume of the work of the first survey (report of 1869), says the benefits derived “conclusively demonstrate that the geological survey was a producer and not a consumer, that it added far more than it took from the public treasury and deserved special encouragement and support as a wealth producing agency in our darkest financial hour.” The publication of the first board, “did much,” says Professor Newberry, “to arrest useless expenditure of money in the search for coal outside of the coal fields and in other mining enterprises equally fallacious, by which, through ignorance of the teachings of geology, parties were constantly led to squander their means.” “It is scarcely less important to let our people know what we have not, than what we have, among our mineral resources.”

“Descriptions of Ancient Works in Ohio. By Charles Whittlesey, of the late Geological Corps of Ohio.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume III., Article 7, 1852.

The topographical and mathematical parts of the survey were committed to Colonel Whittlesey. He made partial reports, to be found in the ‘State Documents’ of 1838 and 1839, but his knowledge acquired in the survey was of vastly greater service in many subsequent writings, and, as a foundation for learning, made useful in many business enterprises of Ohio. He had, during this survey, examined and surveyed many ancient works in the state, and, at its close, Mr. Joseph Sullivant, a wealthy gentleman interested in archaeology, residing in Columbus, proposed that, he bearing the actual expense, Whittlesey should continue the survey of the works of the Mound Builders, with a view to joint publication. During the years 1839 and 1840, and under the arrangement, he made examination of nearly all the remaining works then discovered, but nothing was done toward their publication. Many of his plans and notes were used by Messrs. Squier & Davis, in 1845 and 1846, in their great work, which was the first volume of the Smithsonian Contributions, and in that work these gentlemen said:

“Among the most zealous investigators in the field of American antiquarian research is Charles Whittlesey, esq., of Cleveland, formerly topographical engineer of Ohio. His surveys and observations, carried on for many years and over a wide field, have been both numerous and accurate, and are among the most valuable in all respects of any hitherto made. Although Mr. Whittlesey, in conjunction with Joseph Sullivant, esq., of Columbus, originally contemplated a joint work, in which the results of his investigations should be embodied, he has, nevertheless, with a liberality which will be not less appreciated by the public than by the authors, contributed to this memoir about twenty plans of ancient works, which, with the accompanying explanations and general observations, will be found embodied in the following pages.

“It is to be hoped the public may be put in possession of the entire results of Mr. Whittlesey’s labor, which could not fail of adding greatly to our stock of knowledge on this interesting subject.”

“Marietta Works, Ohio. Charles Whittlesey, Surveyor 1837.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume I., Plate XXVI.

It will be seen that Mr. Whittlesey was now fairly started, interested and intelligent, in the several fields which he was to make his own. And his very numerous writings may be fairly divided into geology, archaeology, history, religion, with an occasional study of topographical geology. A part of Colonel Whittlesey’s surveys were published in 1850, as one of the Smithsonian contributions; portions of the plans and minutes were unfortunately lost. Fortunately the finest and largest works surveyed by him were published. Among those in the work of Squier & Davis, were the wonderful extensive works at Newark, and those at Marietta. No one again could see those works extending over areas of twelve and fifteen miles, as he did. Farmers cannot raise crops without plows, and the geography of the works at Newark must still be learned from the work of Colonel Whittlesey.

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume XIII., Article IV., page 2 of “Ancient Mining on the Shores of Lake Superior” by Charles Whittlesey.

He made an agricultural survey of Hamilton county in 1844. That year the copper mines of Michigan began to excite enthusiasm. The next year a company was organized in Detroit, of which Colonel Whittlesey was the geologist. In August they launched their boat above the rapids of the Sault St. Marie and coasted along the shore to where is now Marquette. Iron ore was beneath notice, and in truth was no then transportable, and they pulled away for Copper Harbor, and then to the region between Portage lake and Ontonagon, where the Algonquin and Douglas Houghton mines were opened. The party narrowly escaped drowning the night they landed. Dr. Houghton was drowned the same night not far from them. A very interesting and life-like account of their adventures was published by Colonel Whittlesey in the National Magazine of New York City, entitled “Two Months in the Copper Regions.” From 1847 to 1851 inclusive, he was employed by the United States in the survey of the country around Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi, in reference to mines and minerals. After that he spent much time in exploring and surveying the mineral district of the Lake Superior basin. The wild life of the woods with a guide and voyageurs threading the streams had great attractions for him and he spent in all fifteen seasons upon Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi, becoming thoroughly familiar with the topography and geological character of that part of the country.

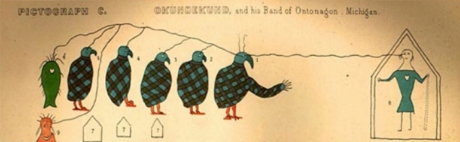

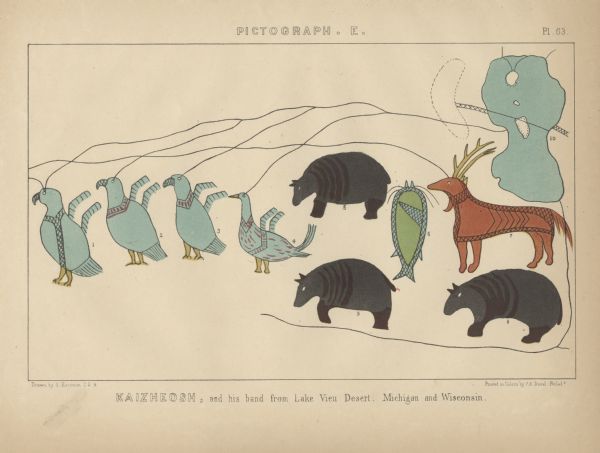

“Pictograph C. Okundekund [Okandikan] and his Band of Ontonagon – Michigan,” as reproduced from birch bark by Seth Eastman, and published as Plate 62 in Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, Volume I., by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, 1851. This was one of several pictograph petitions from the 1849 Martell delegation:

“By this scroll, the chief Kun-de-kund of the Eagle totem of the river Ontonagon, of Lake Superior, and certain individuals of his band, are represented as uniting in the object of their visit of Oshcabewis. He is depicted by the figure of an eagle, Number 1. The two small lines ascending from the head of the bird denote authority or power generally. The human arm extended from the breast of the bird, with the open hand, are symbolic of friendship. By the light lines connecting the eye of each person with the chief, and that of the chief with the President, (Number 8,) unity of views or purpose, the same as in pictography Number 1, is symbolized. Number 2, 3, 4, and 5, are warriors of his own totem and kindred. Their names, in their order, are On-gwai-sug, Was-sa-ge-zhig, or The Sky that lightens, Kwe-we-ziash-ish, or the Bad-boy, and Gitch-ee-man-tau-gum-ee, or the great sounding water. Number 6. Na-boab-ains, or Little Soup, is a warrior of his band of the Catfish totem. Figure Number 7, repeated, represents dwelling-houses, and this device is employed to deonte that the persons, beneath whose symbolic totem it is respectively drawn, are inclined to live in houses and become civilized, in other words, to abandon the chase. Number 8 depicts the President of the United States standing in his official residence at Washington. The open hand extended is employed as a symbol of friendship, corresponding exactly, in this respect, with the same feature in Number 1. The chief whose name is withheld at the left hand of the inferior figures of the scroll, is represented by the rays on his head, (Figure 9,) as, apparently, possessing a higher power than Number 1, but is still concurring, by the eye-line, with Kundekund in the purport of pictograph Number 1.”

“Studio portrait of geologist Charles Whittlesey dressed for a field trip.” Circa 1858.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

His detailed examination extended along the copper range from the extreme east of Point Keweenaw to Ontonagon, through the Porcupine mountain to the Montreal river, and thence to Long lake in Wisconsin, a distance of two hundred miles. In 1849, 1850 and 1858 he explored the valley of the Menominee river from its mouth to the Brule. He was the first geologist to explore the South range. The Wisconsin Geological Survey (Vol. 3 pp. 490 and 679) says this range was first observed by him, and that he many years ago drew attention to its promise of merchantable ores which are now extensively developed from the Wauceda to the Commonwealth mines, and for several miles beyond. He examined the north shore from Fond du Lac east, one hundred miles, the copper range of Minnesota and on the St. Louis river to the bounds of our country. His report was published by the state in 1865, and was stated by Professor Winchill to be the most valuable made.

All his geological work was thorough, and the development of the mineral resources which he examined, and upon which he reported, gave the best proofs of his scientific ability and judgment.

“Outline Map Showing the Position of the Ancient Mine Pits of Point Keweenaw, Michigan by Charles Whittlesey.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume XIII., Article IV., frontpiece of “Ancient Mining on the Shores of Lake Superior” by Charles Whittlesey, 1863.

With the important results from his labors in Ohio in mind, the state of Wisconsin secured his services upon the geological survey of that state, carried on in 1858, 1859 and 1860, and terminated only by the war. The Wisconsin survey was resumed by other parties, and the third volume of the Report for Northern Wisconsin, page 58, says:

The Contract of James Hall with Charles Whittlesey is available from the Journal of the Assembly of Wisconsin, Volume I, pages 178-179, 1862. Whittlesey was to perform “a careful geological survey of the country lying between the Montreal river on the east, and the westerly branches of [the] Bad River on west”. This contract was unfulfilled due to the outbreak of the American Civil War. Whittlesey independently published his survey of the Penokee Mountains in 1865 without Hall. Some of Whittlesey”s pamphlets have been republished here on Chequamegon History in the Western Reserve category of posts.“The only geological examinations of this region, however, previous to those on which the report is based, and deserving the name, were those of Colonel Charles Whittlesey of Cleveland, Ohio. This gentleman was connected with Dr. D. D. Owen’s United States geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota, and in this connection examined the Bad River country, in 1848. The results are given in Dr. Owen’s final report, published in Washington, in 1852. In 1860 (August to October) Colonel Whittlesey engaged in another geological exploration in Ashland, Bayfield and Douglass counties, as part of the geological survey of Wisconsin, then organized under James Hall. His report, presented to Professor Hall in the ensuing year, was never published, on account of the stoppage of the survey. A suite of specimens, collected by Colonel Whittlesey during these explorations, is at present preserved in the cabinet of the state university at Madison, and it bears testimony to the laborious manner in which that gentleman prosecuted the work. Although the report was never published, he has issued a number of pamphlet publications, giving the main results obtained by him. A list of them, with full extracts from some of them, will be found in an appendix to the report. In the same appendix I have reproduced a geological map of this region, prepared by Colonel Whittlesey in 1860.”

“Geological Map of the Penokie Range.” by Charles Whittlesey, Dec. 1860.

~ Geology of Wisconsin. Survey of 1873-1879. Volume III., 1880, Plate XX, page 214.

~ Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, since its establishment in 1802 by George W. Cullum, page 496.

“The Baltimore Plot was an alleged conspiracy in late February 1861 to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln en route to his inauguration. Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, played a key role by managing Lincoln’s security throughout the journey. Though scholars debate whether or not the threat was real, clearly Lincoln and his advisors believed that there was a threat and took actions to ensure his safe passage through Baltimore, Maryland.”

~ Wikipedia.org

Such was Colonel Whittlesey’s employment when the first signs of the civil war appeared. He abandoned it at once. He became a member of one of the military companies that tendered its services to President-elect Lincoln, when he was first threatened, in February, 1861. He became quickly convinced that war was inevitable, and urged the state authorities that Ohio be put at once in preparation for it; and it was partly through his influence that Ohio was so very ready for the fray, in which, at first, the general government relied on the states. Two days after the proclamation of April 15, 1861, he joined the governor’s staff as assistant quartermaster-general. He served in the field in West Virginia with the three months’ men, as state military engineer; with the Ohio troops, under General McClellan, Cox and Hill. At Seary Run, on the Kanawha, July 17, 1861, he distinguished himself by intrepidity and coolness during a severe engagement, in which his horse was shot under him. At the expiration of the three months’ service, he was appointed colonel of the Twentieth regiment, Ohio volunteers, and detailed by General Mitchell as chief engineer of the department of Ohio, where he planned and constructed the defenses of Cincinnati.

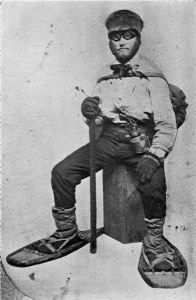

“[Brother] Asaph Whittlesey [Jr.] dressed for his journey from Ashland to Madison, Wisconsin, to take up his seat in the state legislature. Whittlesey is attired for the long trek in winter gear including goggles, a walking staff, and snowshoes.” Circa 1860.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

“SIR: Will you allow me to suggest the consideration of a great movement by land and water, up the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers.

“First, Would it not allow of water transportation half way to Nashville?

“Second, Would it not necessitate the evacuation of Columbus, by threatening their railway communications?

“Third, Would it not necessitate the retreat of General Buckner, by threatening his railway lines?

“Fourth, Is it not the most feasible route into Tennessee?”

This plan was adopted, and Colonel Whittlesey’s regiment took part in its execution.

In April, 1862, on the second day of the battle of Shiloh, Colonel Whittlesey commanded the Third brigade of General Wallace’s division — the Twentieth, Fifty-sixth, Seventy-sixth and Seventy-eighth Ohio regiments. “It was against the line of that brigade that General Beauregard attempted to throw the whole weight of his force for a last desperate charge; but he was driven back by the terrible fire, that his men were unable to face.” As to his conduct, Senator Sherman said in the United States senate.1

The official report of General Wallace leaves little to be said. The division commander says, “The firing was grand and terrible. Before us was the Crescent regiment of New Orleans; shelling us on our right was the Washington artillery of Manassas renown, whose last charge was made in front of Colonel Whittlesey’s command.”

“This is an engraved portrait of Charles Whittlesey, a prominent soldier, attorney, scholar, newspaper editor, and geologist during the nineteenth century. He participated in a geological survey of Ohio conducted in the late 1830s, during which he discovered numerous Native American earthworks. In 1867, Whittlesey helped establish the Western Reserve Historical Society, and he served as the organization’s president until his death in 1886. Whittlesey also wrote approximately two hundred books and articles, mostly on geology and Ohio’s early history.”

~ Ohio History Central

General Force, then lieutenant-colonel under Colonel Whittlesey, fully describes the battle,2 and quotes General Wallace. “The nation is indebted to our brigade for the important services rendered, with the small loss it sustained and the manner in which Colonel Whittlesey handled it.”

Colonel Whittlesey was fortunate in escaping with his life, for General Force says, it was ascertained that the rebels had been deliberately firing at him, sometimes waiting to get a line shot.

Colonel Whittlesey had for some time been in bad health, and contemplating resignation, but deferring it for a decisive battle. Regarding this battle as virtually closing the campaign in the southwest, and believing the Rebellion to be near its end, he now sent it in.

General Grant endorsed his application, “We cannot afford to lose so good an officer.”

“Few officers,” it is said, “retired from the army with a cleaner or more satisfactory record, or with greater regret on the part of their associates.” The Twentieth was an early volunteer regiment. The men were citizens of intelligence and character. They reached high discipline without severity, and without that ill-feeling that often existed between men and their officers. There was no emergency in which they could not be relied upon. “Between them and their commander existed a strong mutual regard, which, on their part, was happily expressed by a letter signed by all the non-commissioned officers.”

“CAMP SHILOH, NEAR PITTSBURGH LANDING, TENNESSEE, April 21, 1862.

“COL. CHAS. WHITTLESEY:

“Sir — We deeply regret that you have resigned the command of the Twentieth Ohio. The considerate care evinced for the soldiers in camp, and, above all, the courage, coolness and prudence displayed on the battle-field, have inspired officers and men with the highest esteem for, and most unbounded confidence in our commander.

“From what we have seen at Fort Donelson, and at the bloody field near Pittsburgh, on Monday, the seventh, all felt ready to follow you unfalteringly into any contest and into any post of danger.

“While giving expression to our unfeigned sorrow at your departure from us, and assurance of our high regard and esteem for you, and unwavering confidence as our leader, we would follow you with the earnest hope that your future days may be spent in uninterrupted peace and quiet, enjoying the happy reflections and richly earned rewards of well-spent service in the cause of our blessed country in its dark hour of need.”

Said Mr. W. H. Searles, who served under him, at the memorial meeting of the Engineers Club of Cleveland: “In the war he was genial and charitable, but had that conscientious devotion to duty characteristic of a West Point soldier.”

Since Colonel Whittlesey’s decease the following letter was received:

“CINCINNATI, November 10, 1886.

“DEAR MRS. WHITTLESEY: — Your noble husband has got release from the pains and ills that made life a burden. His active life was a lesson to us how to live. His latter years showed us how to endure. To all of us in the Twentieth Ohio regiment he seemed a father. I do not know any other colonel that was so revered by his regiment. Since the war he has constantly surprised me with his incessant literary and scientific activity. Always his character was an example and an incitement. Very truly yours,

“M. F. Force.”

Colonel Whittlesey now turned his attention at once again to explorations in the Lake Superior and upper Mississippi basins, and “new additions to the mineral wealth of the country were the result of his surveys and researches.” His geological papers commencing again in 1863, show his industry and ability.

It happened during his life many times, and will happen again and again, that his labors as an original investigator have borne and will bear fruit long afterwards, and, as the world looks at fruition, of much greater value to others than to himself.

~ Report of a geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota: and incidentally of a portion of Nebraska Territory, by David Dale Owen, 1852, page 420.

He prognosticated as early as 1848, while on Dr. Owen’s survey, that the vast prairies of the northwest would in time be the great wheat region. These views were set forth in a letter requested by Captain Mullen of the Topographical Engineers, who had made a survey for the Northern Pacific railroad, and was read by him in a lecture before the New York Geographical society in the winter of 1863-4.

He examined the prairies between the head of the St. Louis river and Rainy Lake, between the Grand fork of Rainy Lake river and the Mississippi, and between the waters of Cass Lake and those of Red Lake. All were found so level that canals might be made across the summits more easily than several summits already cut in this country.

In 1879 the project attracted attention, and Mr. Seymour, the chief engineer and surveyor of New York, became zealous for it, and in his letters of 1880, to the Chambers of Commerce of Duluth and Buffalo, acknowledged the value of the information supplied by Colonel Whittlesey.

Says the Detroit Illustrated News:

“A large part of the distance from the navigable waters of Lake Superior to those of Red river, about three hundred and eight miles, is river channel easily utilized by levels and drains or navigable lakes. The lift is about one thousand feet to the Cass Lake summit. At Red river this canal will connect with the Manitoba system of navigation through Lake Winnipeg and the valleys of the Saskatchewan. Its probable cost is given at less than four millions of dollars, which is below the cost of a railway making the same connections. And it is estimated that a bushel of wheat may be carried from Red river to New York by water for seventeen cents, or about one-third of the cost of transportation by rail.”

We approach that part of the life of Colonel Whittlesey which was so valuable to our society. The society was proposed in 1866.3 Colonel Whittlesey’s own account of its foundation is: “The society originally comprised about twenty persons, organized in May, 1867, upon the suggestion of C. C. Baldwin, its present secretary. The real work fell upon Colonel Whittlesey, Mr. Goodman and Mr. Baldwin, Mr. Goodman devoting nearly all of his time until 1872 (the date of his death).” The statement is a very modest one on the part of Colonel Whittlesey. All looked to him to lead the movement, and none other could have approached his efficiency or ability as president of the society.