Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Coda

June 1, 2024

My last post ended up containing several musings on the nature of primary-source research and how to acknowledge mistakes and deal with uncertainty in the historical record. This was in anticipation of having to write this post. It’s a post I’ve been putting off for years.

Amorin forced the issue with his important work on the speeches at the 1842 Treaty negotiations. While working on it, he sent me a message that read something like, “Hey, the article quotes Chief Buffalo and describes him in a blue military coat with epaulets. Is the world ready for that picture that Smithsonian guy sent us years ago?”

This was the image in question:

Henry Inman, Big Buffalo (Chippewa), 1832-1833, oil on canvas, frame: 39 in. × 34 in. × 2 1/4 in. (99.1 × 86.4 × 5.7 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Gerald and Kathleen Peters, 2019.12.2

We first learned of this image from a Chequamegon History comment by Patrick Jackson of the Smithsonian asking what we knew about the image and whether or not it was Chief Buffalo from La Pointe.

We had never seen it before.

This was our correspondence with Mr. Jackson at the time:

July 17, 2019

Hello, my name is Patrick, and I am an intern at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I’m working on researching a recent acquisition: a painting which came to us identified as a Henry Inman portrait of “Big Buffalo Ke-Che-Wais-Ke, The Great Renewer (1759-1855) (Chippewa).” We have run into some confusion about the identification of the portrait, as it came to us identified as stated above, yet at Harvard Peabody Museum, who was previously the owner of the portrait, it was listed as an unidentified sitter. Seeing as you’ve written a few posts about the identification of images of the three different Chief Buffalos, I thought you might be able to give some insight into perhaps who is or isn’t in the portrait we have. Thank you for your time.

July 17, 2019

Hello,

I would be happy to comment. Can you send a photo to this email?

I am pretty sure Inman painted a copy of Charles Bird King’s portrait of Pee-che-kir.

Doe it resemble that portrait? Pee-che-kir (Bizhiki) means Buffalo in Ojibwe (Chippewa). From my research, I am fairly certain that King’s portrait is not of Kechewaiske, but of another chief named Buffalo who lived in the same era.

Leon Filipczak

July 17, 2019

Dear Leon,

I have attached our portrait—it’s not the best scan, but hopefully there’s enough detail for you to work with. I’ve compared it with the Peechikir in McKenney & Hall, as well as to the Chief Buffalo painted ambrotype and the James Otto Lewis portrait of Pe-schick-ee. The ambrotype has a close resemblance, as does the Peecheckir, though if that is what Charles Bird King painted I have doubts that Inman would make such drastic changes in clothing and pose.

The identification as Big Buffalo/Ke-Che-Wais-Ke/The Great Renewer, as far as I understand, refers to the La Pointe Bizhiki/Buffalo rather than the St. Croix or Leech Lake Buffalos, though of course that is a questionable identification considering Kechewaiske did not (I think) visit Washington until after Inman’s death in January of 1846. McKenney, however, did visit the Ojibwe/Chippewa for the negotiations for the Treaty of Fond du Lac in 1825/1826, and could feasibly have met multiple Chief Buffalos. Perhaps a local artist there would be responsible for the original? Another possibility is, since the identification was not made at the Peabody, who had the portrait since the 1880s, is that it has been misidentified entirely and is unrelated to any of the Ojibwe/Chippewa chiefs. Though this, to me, would seem unlikely considering the strong resemblance of the figure in our portrait to the Peechikir portrait and Chief Buffalo ambrotype.

Thank you again for the help.

Sincerely,

Patrick

July 22, 2019

Hello Patrick,

This is a head-scratcher. Your analysis is largely what I would come up with. My first thought when I saw it was, “Who identified it as someone named Buffalo? When? and using what evidence?” Whoever associated the image with the text “Ke-Che-Wais-Ke, The Great Renewer (1759-1855)” did so decades after the painting could be assumed to be created. However, if the tag “Big Buffalo” can be attached to this image in the era it was created, then we may be onto something. This is what I know:

1) During his time as Superintendent of Indian Affairs (late 1820s), Thomas McKenney amassed a large collection of portraits of Indian chiefs for what he called the “Indian Gallery” in the War Department. He sought the portraits out wherever and whenever he could. When chiefs would come to Washington, he would have Charles Bird King do the work, but he also received portraits from the interior via artists like James Otto Lewis.

2) In 1824, Bizhiki (Buffalo) from the St. Croix River (not Great Buffalo from La Pointe), visited Washington and was painted by King. This painting is presumed to have been destroyed in the Smithsonian fire that took out most of the Indian Gallery.

3) In 1825 at Prairie du Chien and in 1826 at Fond du Lac (where McKenney was present) James Otto Lewis painted several Ojibwe chiefs, and these paintings also ended up in the Indian Gallery. Both chief Buffalos were present at these treaties.

4) A team of artists copied each others’ work from these originals. King, for example remade several of Lewis’ portraits to make the faces less grotesque. Inman copied several Indian Gallery portraits (mostly King’s) to be sent to other institutions. These are the ones that survived the Smithsonian fire.

5) In the late 1830s, 10+ years after most of the portraits were painted, Lewis and McKenney sold competing lithograph collections to the American public. McKenney’s images were taken from the Indian Gallery. Lewis’ were from his works (some of which were in the Indian Gallery, often redone by King). While the images were printed with descriptions, the accuracy of the descriptions leaves something to be desired. A chief named Bizhiki appears in both Lewis and McKenney-Hall. In both, the chiefs are dressed in white and faced looking left, but their faces look nothing alike. One is very “Lewis-grotesque.” and the other is not at all. There are Lewis-based lithographs in both competing works, and they are usually easy to spot.

6) Not every image from the Indian Gallery made it into the published lithographic collections. Brian Finstad, a historian of the upper-St. Croix country, has shown me an image of Gaa-bimabi (Kappamappa, Gobamobi), a close friend/relative of the La Pointe Chief Buffalo, and upstream neighbor of the St. Croix Buffalo. This image is held by Harvard and strongly resembles the one you sent me in style. I suspect it is an Inman, based on a Lewis (possibly with a burned-up King copy somewhere in between).

7) “Big Buffalo” would seemingly indicate Buffalo from La Pointe. The word gichi is frequently translated as both “great” and “big” (i.e. big in size or big in power). Buffalo from La Pointe was both. However, the man in the painting you sent is considerably skinnier and younger-looking than I would expect him to appear c.1826.

My sense is that unless accompanying documentation can be found, there is no way to 100% ID these pictures. I am also starting to worry that McKenney and the Indian Gallery artists, themselves began to confuse the two chief Buffalos, and that the three originals (two showing St. Croix Buffalo, and one La Pointe Buffalo) burned. Therefore, what we are left with are copies that at best we are unable to positively identify, and at worst are actually composites of elements of portraits of two different men. The fact that King’s head study of Pee-chi-kir is out there makes me wonder if he put the face from his original (1824 portrait of St. Croix Buffalo?) onto the clothing from Lewis’ portrait of Pe-shick-ee when it was prepared for the lithograph publication.

A few weeks later, Patrick sent a follow-up message that he had tracked down a second version and confirmed that Inman’s portrait was indeed a copy of a Charles Bird King portrait, based on a James Otto Lewis original. It included some critical details.

Portrait of Big Buffalo, A Chippewa, 1827 Charles Bird King (1785-1862), signed, dated and inscribed ‘Odeg Buffalo/Copy by C King from a drawing/by Lewis/Washington 1826’ (on the reverse) oil on panel 17 1⁄2 X 13 3⁄4 in. (44.5 x 34.9 cm.) Last sold by Christie’s Auction House for $478,800 on 26 May 2022

The date of 1826 makes it very likely that Lewis’ original was painted at the Treaty of Fond du Lac. Chief Buffalo of La Pointe would have been in his 60s, which appears consistent with the image of Big Buffalo. Big Buffalo also does not appear as thin in King’s intermediate version as he does in Inman’s copy, lessening the concerns that the image does not match written descriptions of the chief.

Another clue is that it appears Lewis used the word Odeg to disambiguate Big Buffalo from the two other chiefs named Buffalo present at Fond du Lac in 1826. This may be the Ojibwe word Andeg (“crow”). Although I have not seen any other source that calls the La Pointe chief Andeg, it was a significant name in his family. He had multiple close relatives with Andeg in their names, which may have all stemmed from the name of Buffalo’s grandfather Andeg-wiiyaas (Crow’s Meat). As hereditary chief of the Andeg-wiiyaas band, it’s not unreasonable to think the name would stay associated with Buffalo and be used to distinguish him from the other Buffalos. However, this is speculative.

So, there we were. After the whole convoluted Chief Buffalo Picture Search, did we finally have an image we could say without a doubt was Chief Buffalo of La Pointe? No. However, we did have one we could say was “likely” or even “probably” him. I considered posting at the time, but a few things held me back.

In the earliest years of Chequamegon History, 2013 and 2014, many of the posts involved speculation about images and me trying to nitpick or disprove obvious research mistakes of others. Back then, I didn’t think anyone was reading and that the site would only appeal to academic types. Later on, however, I realized that a lot of the traffic to the site came from people looking for images, who weren’t necessarily reading all the caveats and disclaimers. This meant we were potentially contributing to the issue of false information on the internet rather than helping clear it up. So by 2019, I had switched my focus to archiving documents through the Chequamegon History Source Archive, or writing more overtly subjective and political posts.

So, the Smithsonian image of Big Buffalo went on the back burner, waiting to see if more information would materialize to confirm the identity of the man one way or the other. None did, and then in 2020 something happened that gave the whole world a collective amnesia that made those years hard to remember. When Amorin asked about using the image for his 1842 post, my first thought was “Yeah, you should, but we should probably give it its own post too.” My second thought was, “Holy crap! It’s been five years!”

Anyway, here is Chequamegon History’s statement on the identity of the man in Henry Inman’s 1832-33 portrait of Big Buffalo (Chippewa).

Likely Chief Buffalo of La Pointe: We are not 100% certain, but we are more certain than we have been about any other image featured in the Chief Buffalo Picture Search. This is a copy of a copy of a missing original by James Otto Lewis. Lewis was a self-taught artist who struggled with realistic facial features. Charles Bird King and Henry Inman, who made the first and second copies, respectively, had more talent for realism. However, they did not travel to Lake Superior themselves and were working from Lewis’ original. Therefore, the appearance of Big Buffalo may accurately show his clothing, but is probably less accurate in showing his actual physical appearance.

And while we’re on the subject of correcting misinformation related to images, I need to set the record straight on another one and offer my apologies to a certain Benjamin Green Armstrong. I promise, it relates indirectly to the “Big Buffalo” painting.

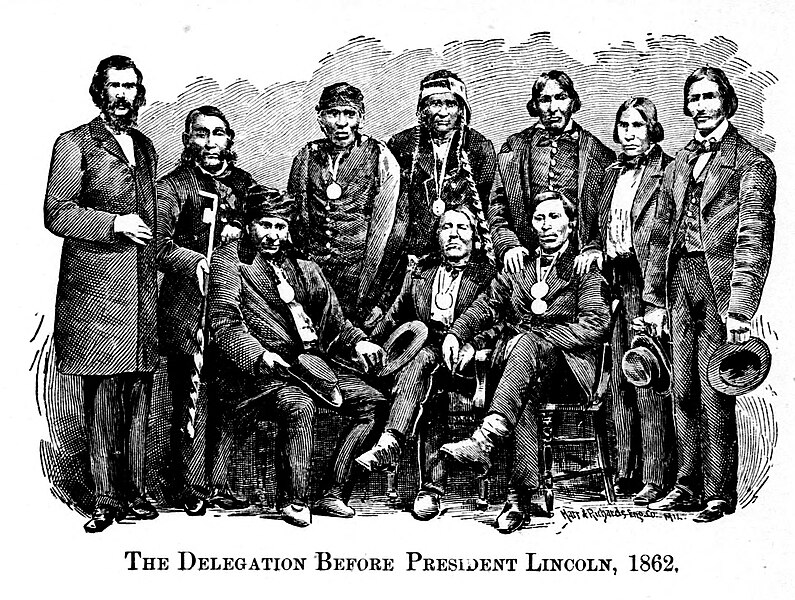

An engraving of the image in question appears in Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians.

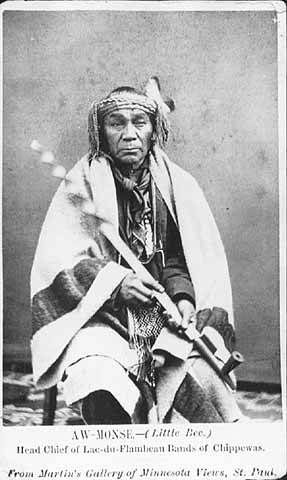

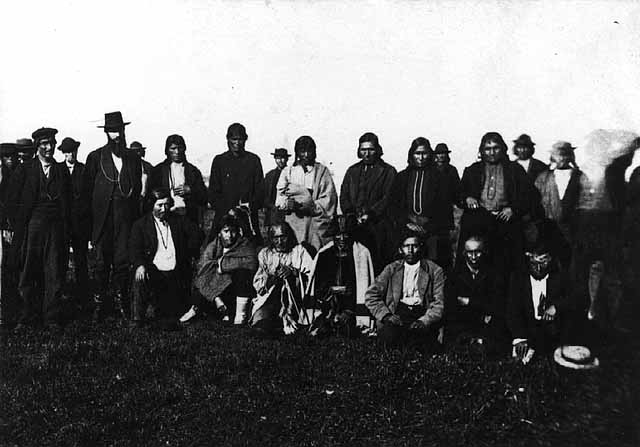

Ah-moose (Little Bee) from Lac Flambeau Reservation, Kish-ke-taw-ug (Cut Ear) from Bad River Reservation, Ba-quas (He Sews) from Lac Courte O’Rielles Reservation, Ah-do-ga-zik (Last Day) from Bad River Reservation, O-be-quot (Firm) from Fond du Lac Reservation, Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation, Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell) from La Pointe Reservation, Na-gon-ab (He Sits Ahead) from Fond du Lac Reservation, and O-ma-shin-a-way (Messenger) from Bad River Reservation.

In this post, we contested these identifications on the grounds that Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Little Buffalo) from La Pointe Reservation died in 1860 and therefore could not have been part of the delegation to President Lincoln. In the comments on that post, readers from Michigan suggested that we had several other identities wrong, and that this was actually a group of chiefs from the Keweenaw region. We commented that we felt most of Armstrong’s identifications were correct, but that the picture was probably taken in 1856 in St. Paul.

Since then, a document has appeared that confirms Armstrong was right all along.

[Antoine Buffalo, Naagaanab, and six other chiefs to W.P. Dole, 6 March 1863

National Archives M234-393 slide 14

Transcribed by L. Filipczak 12 April 2024]

To Our Father,

Hon W P. Dole

Commissioner of Indian Affairs–

We the undersigned chiefs of the chippewas of Lake Superior, now present in Washington, do respectfully request that you will pay into the hands of our Agent L. E. Webb, the sum of Fifteen Hundred Dollars from any moneys found due us under the head of “Arrearages in Annuity” the said money to be expended in the purchase of useful articles to be taken by us to our people at home.

Antoine Buffalo His X Mark | A daw we ge zhig His X Mark

Naw gaw nab His X Mark | Obe quad His X Mark

Me zhe na way His X Mark | Aw ke wen zee His X Mark

Kish ke ta wag His X Mark | Aw monse His X Mark

I certify that I Interpreted the above to the chiefs and that the same was fully understood by them

Joseph Gurnoe

U.S. Interpreter

Witnessed the above Signed } BG Armstrong

Washington DC }

March 6th 1863 }

There were eight Lake Superior chiefs, an interpreter, and a witness in Washington that spring, for a total of ten people. There are ten people in the photograph. Chequamegon History is confident that this document confirms they are the exact ten identified by Benjamin Armstrong.

The Lac Courte Oreilles chief Ba-quas is the same person as Akiwenzii. It was not unusual for an Ojibwe chief to have more than one name. Chief Buffalo, Gaa-bimaabi, Zhingob the Younger, and Hole-in-the-Day the Younger are among the many examples.

The name “Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation” seems to be absent from the letter, but he is there too. Let’s look at the signature of the interpreter, Joseph Gurnoe.

Gurnoe’s beautiful looping handwriting will be familiar to anyone who has studied the famous 1864 bilingual petition. We see this same handwriting in an 1879 census of Red Cliff. In this document, Gurnoe records his own Ojibwe name as Shingwākons, The young Pine tree.

So the man standing on the far right is Gurnoe. This can be confirmed by looking at other known photos of him.

Finally, it confirms that the chief seated on the bottom left is not Jechiikwii’o (Little Buffalo), but rather his son Antoine, who inherited the chieftainship of the Buffalo Band after the death of his father two years earlier. Known to history as Chief Antoine Buffalo, in his lifetime he was often called Antoine Tchetchigwaio (or variants thereof), using his father’s name as a surname rather than his grandfather’s.

So, now we need to address the elephant in the room that unites the Henry Inman portrait of Big Buffalo with the photograph of the 1862-63 Delegation to Washington:

Wisconsin Historical Society

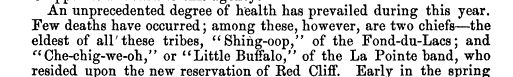

This is the “ambrotype” referenced by Patrick Jackson above. It’s the image most associated with Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. It’s also one for which we have the least amount of background information. We have not been able to determine who the original photographer/painter was or when the image was created.

The resemblance to the portrait of “Big Buffalo” is undeniable.

However, if it is connected to the 1862-63 image of Chief Antoine Buffalo, it would support Hamilton Nelson Ross’s assertions on the Wisconsin Historical Society copy.

Clearly, multiple generations of the Buffalo family wore military jackets.

Inconclusive: uncertainty is no fun, but at this point Chequamegon History cannot determine which Chief Buffalo is in the ambrotype. However, the new evidence points more toward the grandfather (Great Buffalo) and grandson (Antoine) than it does to the son (Little Buffalo).

We will keep looking.

Error Correction: Photo Mystery Still Unsolved

April 27, 2014

This post is outdated. We’ll leave it up, but for the latest research, see Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Coda

According to Benjamin Armstrong, the men in this photo are (back row L to R) Armstrong, Aamoons, Giishkitawag, Ba-quas (identified from other photos as Akiwenzii), Edawi-giizhig, O-be-quot, Zhingwaakoons, (front row L to R) Jechiikwii’o, Naaganab, and Omizhinawe in an 1862 delegation to President Lincoln. However, Jechiikwii’o (Jayjigwyong) died in 1860.

In the Photos, Photos, Photos post of February 10th, I announced a breakthrough in the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search. It concerned this well-known image of “Chief Buffalo.”

(Wisconsin Historical Society)

The image, long identified with Gichi-weshkii, also called Bizhiki or Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855, has also been linked to the great chief’s son and grandson. In the February post, I used Benjamin Armstrong’s description of the following photo to conclude that the man seated on the left in this group photograph was in fact the man in the portrait. That man was identified as Jechiikwii’o, the oldest son of Chief Buffalo (a chief in his own right who was often referred to as Young Buffalo).

Another error in the February post is the claim that this photo was modified for and engraving in Armstrong’s book, Early Life Among the Indians. In fact, the engraving is derived from a very similar photo seen at the top of this post (Minnesota Historical Society).

(Marr & Richards Co. for Armstrong)

The problem with this conclusion is that it would have been impossible for Jechiikwii’o to visit Lincoln in the White House. The sixteenth president was elected shortly after the following report came from the Red Cliff Agency:

Drew, C.K. Report on the Chippewas of Lake Superior. Red Cliff Agency. 29 Oct. 1860. Pg. 51 of Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Bureau of Indian Affairs. 1860. (Digitized by Google Books).

This was a careless oversight on my part, considering this snippet originally appeared on Chequamegon History back in November. Jechiikwii’o is still a likely suspect for the man in the photo, but this discrepancy must be settled before we can declare the mystery solved.

The question comes down to where Armstrong made the mistake. Is the man someone other than Jechiikwii’o, or is the photo somewhere other than the Lincoln White House?

If it isn’t Jechiikwii’o, the most likely candidate would be his son, Antoine Buffalo. If you remember this post, Hamilton Ross did identify the single portrait as a grandson of Chief Buffalo. Jechiikwii’o, a Catholic, gave his sons Catholic names: Antoine, Jean-Baptiste, Henry. Ultimately, however, they and their descendants would carry their grandfather’s name as a surname: Antoine Buffalo, John Buffalo, Henry Besheke, etc., so one would expect Armstrong (who was married into the family) to identify Antoine as such, and not by his father’s name.

However, I was recently sent a roster of La Pointe residents involved in stopping the whiskey trade during the 1855 annuity payment. Among the names we see:

…Antoine Ga Ge Go Yoc

John Ga Ge Go Yoc…[Read the first two Gs softly and consider that “Jayjigwyong” was Leonard Wheeler’s spelling of Jechiikwii’o]

So, Antoine and John did carry their father’s name for a time.

Regardless, though, the age and stature of the man in the group photograph, Armstrong’s accuracy in remembering the other chiefs, and the fact that Armstrong was married into the Buffalo family still suggest it’s Jechiikwii’o in the picture.

Fortunately, there are enough manuscript archives out there related to the 1862 delegation that in time I am confident someone can find the names of all the chiefs who met with Lincoln. This should render any further speculation irrelevant and will hopefully settle the question once and for all.

Until then, though, we have to reflect again on why Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians is simultaneously the most accurate and least accurate source on the history of this area. It must be remembered that Armstrong himself admitted his memory was fuzzy when he dictated the work in his final years. Still, the level of accuracy in the small details is unsurpassed and confirms his authenticity even as the large details can be way off the mark.

Thank you to Charles Lippert for providing the long awaited translation and transliteration of Jechiikwii’o into the modern Ojibwe alphabet. Amorin Mello kindly shared the 1855 La Pointe documents, transcribed and submitted to the Michigan Family History website by Patricia Hamp, and Travis Armstrong’s ChiefBuffalo.com remains an outstanding bank of primary sources on the Buffalo and Armstrong families.

Photos, Photos, Photos

February 10, 2014

The queue of Chequamegon History posts that need to be written grows much faster than my ability to write them. Lately, I’ve been backed up with mysteries surrounding a number of photographs. Many of these photos are from after 1860, so they are technically outside the scope of this website (though they involve people who were important in the pre-1860 era too.

Photograph posts are some of the hardest to write, so I decided to just run through all of them together with minimal commentary other than that needed to resolve the unanswered questions. I will link all the photos back to their sources where their full descriptions can be found. Here it goes, stream-of-consciousness style:

Ojibwa Delegation by C.M. Bell. Washington D.C. 1880 (NMAI Collections)

This whole topic started with a photo of a delegation of Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs that sits on the windowsill of the Bayfield Public Library. Even though it is clearly after 1860, some of the names in the caption: Oshogay, George Warren, and Vincent Roy Jr. caught my attention. These men, looking past their prime, were all involved in the politics of the 1850s that I had been studying, so I wanted to find out more about the picture.

As I mentioned in the Oshogay post, this photo is also part of the digital collections of the Smithsonian, but the people are identified by different names. According to the Smithsonian, the picture was taken in Washington in 1880 by the photographer C.M. Bell.

I found a second version of this photo as well. If it wasn’t for one of the chiefs in front, you’d think it was the same picture:

While my heart wanted to believe the person, probably in the early 20th century, who labelled the Bayfield photograph, my head told me the photographer probably wouldn’t have known anything about the people of Lake Superior, and therefore could only have gotten the chiefs’ names directly from them. Plus, Bell took individual photos:

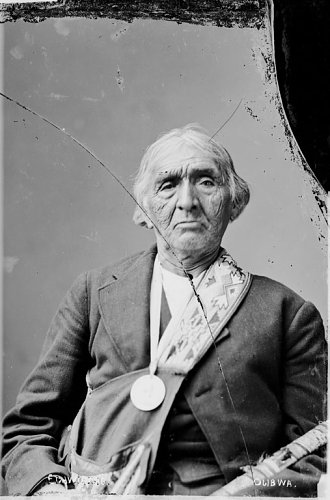

Edawigijig (Edawi-giizhig “Both Sides of the Sky”), Bad River chief and signer of the Treaty of 1854 (C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections)

Niizhogiizhig: “Second Day,” (C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections)

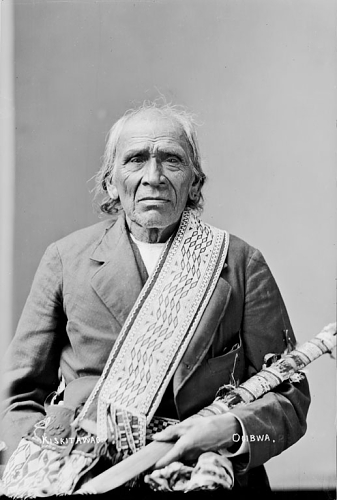

Kiskitawag (Giishkitawag: “Cut Ear”) signed multiple treaties as a warrior of the Ontonagon Band but afterwards was associated with the Bad River Band (C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections).

By cross-referencing the individual photos with the names listed with the group photo, you can identify nine of the thirteen men. They are chiefs from Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, and Lac du Flambeau.

According to this, the man identified by the library caption as Vincent Roy Jr., was in fact Ogimaagiizhig (Sky Chief). He does have a resemblance to Roy, so I’ll forgive whoever it was, even if it means having to go back and correct my Vincent Roy post:

According to this, the man identified by the library caption as Vincent Roy Jr., was in fact Ogimaagiizhig (Sky Chief). He does have a resemblance to Roy, so I’ll forgive whoever it was, even if it means having to go back and correct my Vincent Roy post:

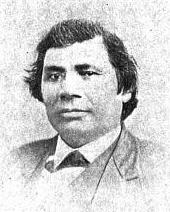

Vincent Roy Jr. From C. Verwyst’s Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, First Bishop of Marquette, Mich: To which are Added Short Sketches of the Lives and Labors of Other Indian Missionaries of the Northwest (Digitized by Google Books)

Top: Frank Roy, Vincent Roy, E. Roussin, Old Frank D.o., Bottom: Peter Roy, Jos. Gourneau (Gurnoe), D. Geo. Morrison. The photo is labelled Chippewa Treaty in Washington 1845 by the St. Louis Hist. Lib and Douglas County Museum, but if it is in fact in Washington, it was probably the Bois Forte Treaty of 1866, where these men acted as conductors and interpreters (Digitized by Mary E. Carlson for The Sawmill Community at Roy’s Point).

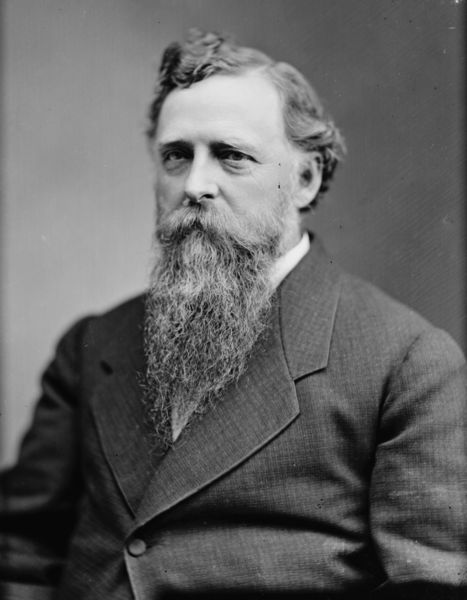

So now that we know who went on the 1880 trip, it begs the question of why they went. The records I’ve found haven’t been overly clear, but it appears that it involved a bill in the senate for “severalty” of the Ojibwe reservations in Wisconsin. A precursor to the 1888 Allotment Act of Senator Henry Dawes, this legislation was proposed by Senator Thaddeus C. Pound of Wisconsin. It would divide the reservations into parcels for individual families and sell the remaining lands to the government, thereby greatly reducing the size of the reservations and opening the lands up for logging.

Pound spent a lot of time on Indian issues and while he isn’t as well known as Dawes or as Richard Henry Pratt the founder of the Carlisle Indian School, he probably should be. Pound was a friend of Pratt’s and an early advocate of boarding schools as a way to destroy Native cultures as a way to uplift Native peoples.

I’m sure that Pound’s legislation was all written solely with the welfare of the Ojibwe in mind, and it had nothing to do with the fact that he was a wealthy lumber baron from Chippewa Falls who was advocating damming the Chippewa River (and flooding Lac Courte Oreilles decades before it actually happened). All sarcasm aside, if any American Indian Studies students need a thesis topic, or if any L.C.O. band members need a new dartboard cover, I highly recommend targeting Senator Pound.

Like many self-proclaimed “Friends of the Indian” in the 1880s, Senator Thaddeus C. Pound of Wisconsin thought the government should be friendly to Indians by taking away more of their land and culture. That he stood to make a boatload of money out of it was just a bonus (Brady & Handy: Wikimedia Commons).

While we know Pound’s motivations, it doesn’t explain why the chiefs came to Washington. According to the Indian Agent at Bayfield they were brought in to support the legislation. We also know they toured Carlisle and visited the Ojibwe students there. There are a number of potential explanations, but without having the chiefs’ side of the story, I hesitate to speculate. However, it does explain the photograph.

Now, let’s look at what a couple of these men looked like two decades earlier:

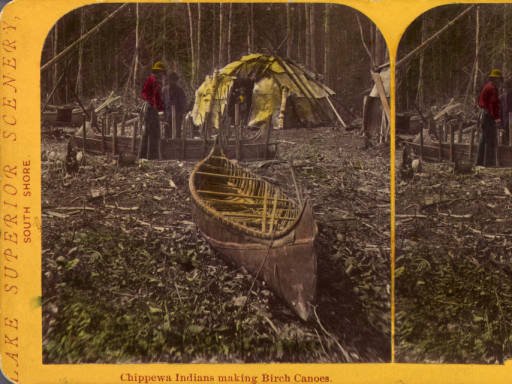

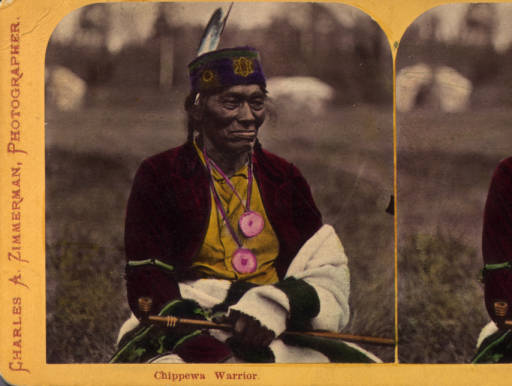

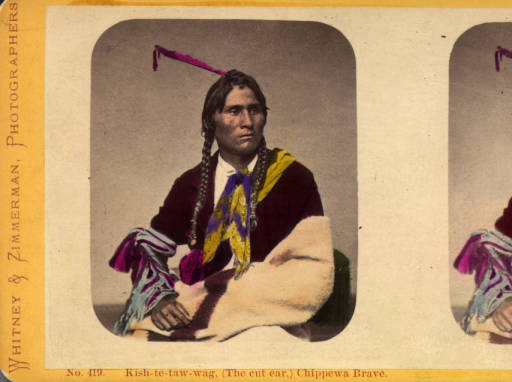

This stereocard of Giishkitawag was produced in the early 1870s, but the original photo was probably taken in the early 1860s (Denver Public Library).

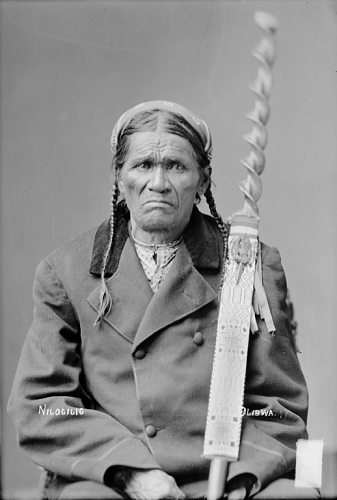

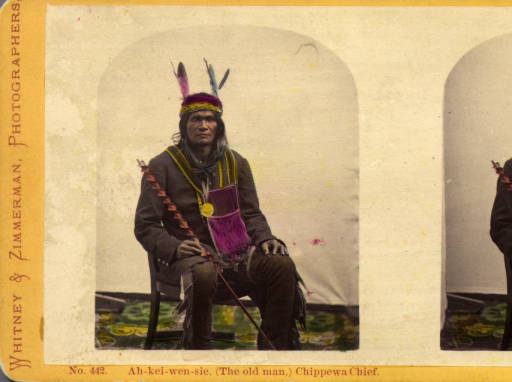

By the mid 1850s, Akiwenzii (Old Man) was the most prominent chief of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band. This stereocard was made by Whitney and Zimmerman c.1870 from an original possibly by James E. Martin in the late 1850s or early 1860s (Denver Public Library).

Giishkitawag and Akiwenzii are seem to have aged quite a bit between the early 1860s, when these photos were taken, and 1880 but they are still easily recognized. The earlier photos were taken in St. Paul by the photographers Joel E. Whitney and James E. Martin. Their galleries, especially after Whitney partnered with Charles Zimmerman, produced hundreds of these images on cards and stereoviews for an American public anxious to see real images of Indian leaders.

Giishkitawag and Akiwenzii were not the only Lake Superior chiefs to end up on these souvenirs. Aamoons (Little Bee), of Lac du Flambeau appears to have been a popular subject:

Aamoons (Little Bee) was a prominent chief from Lac du Flambeau (Denver Public Library).

As the images were reproduced throughout the 1870s, it appears the studios stopped caring who the photos were actually depicting:

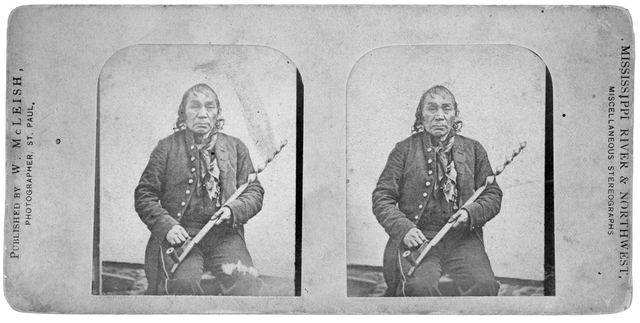

One wonders what the greater insult to Aamoons was: reducing him to being simply “Chippewa Brave” as Whitney and Zimmerman did here, or completely misidentifying him as Na-gun-ub (Naaganab) as a later stereo reproduction as W. M. McLeish does here:

Chief identified as Na-gun-ub (Minnesota Historical Society)

Aamoons and Naaganab don’t even look alike…

Naaganab (Minnesota Historical Society)

…but the Lac du Flambeau and Fond du Lac chiefs were probably photographed in St. Paul around the time they were both part of a delegation to President Lincoln in 1862.

Chippewa Delegation 1862 by Matthew Brady? (Minnesota Historical Society)

Naaganab (seated middle) and Aamoons (back row, second from left) are pretty easy to spot, and if you look closely, you’ll see Giishkitawag, Akiwenzii, and a younger Edawi-giizhig (4th, 5th, and 6th from left, back row) were there too. I can’t find individual photos of the other chiefs, but there is a place we can find their names.

Benjamin Armstrong, who interpreted for the delegation, included a version of the image in his memoir Early Life Among the Indians. He identifies the men who went with him as:

Ah-moose (Little Bee) from Lac Flambeau Reservation, Kish-ke-taw-ug (Cut Ear) from Bad River Reservation, Ba-quas (He Sews) from Lac Courte O’Rielles Reservation, Ah-do-ga-zik (Last Day) from Bad River Reservation, O-be-quot (Firm) from Fond du Lac Reservation, Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation, Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell) from La Pointe Reservation, Na-gon-ab (He Sits Ahead) from Fond du Lac Reservation, and O-ma-shin-a-way (Messenger) from Bad River Reservation.

It appears that Armstrong listed the men according to their order in the photograph. He identifies Akiwenzii as “Ba-quas (He Sews),” which until I find otherwise, I’m going to assume the chief had two names (a common occurrence) since the village is the same. Aamoons, Giishkitawag, Edawi-giizhig and Naaganab are all in the photograph in the places corresponding to the order in Armstrong’s list. That means we can identify the other men in the photo.

I don’t know anything about O-be-quot from Fond du Lac (who appears to have been moved in the engraving) or S[h]ing-guak-onse from Red Cliff (who is cut out of the photo entirely) other than the fact that the latter shares a name with a famous 19th-century Sault Ste. Marie chief. Travis Armstrong’s outstanding website, chiefbuffalo.com, has more information on these chiefs and the mission of the delegation.

Seated to the right of Naaganab, in front of Edawi-giizhig is Omizhinawe, the brother of and speaker for Blackbird of Bad River. Finally, the broad-shouldered chief on the bottom left is “Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell)” from Red Cliff. This is Jajigwyong, the son of Chief Buffalo, who signed the treaties as a chief in his own right. Jayjigwyong, sometimes called Little Chief Buffalo, was known for being an early convert to Catholicism and for encouraging his followers to dress in European style. Indeed, we see him and the rest of the chiefs dressed in buttoned coats and bow-ties and wearing their Lincoln medals.

Wait a minute… button coats?… bow-ties?… medals?…. a chief identified as Buffalo…That reminds me of…

This image is generally identified as Chief Buffalo (Wikimedia Commons)

Anyway, with that mystery solved, we can move on to the next one. It concerns a photograph that is well-known to any student of Chequamegon-area history in the mid 19th century (or any Chequamegon History reader who looks at the banners on the side of this page).Noooooo!!!!!!! I’ve been trying to identify the person in The above “Chief Buffalo” photo for years, and the answer was in Armstrong all along! Now I need to revise this post among others. I had already begun to suspect it was Jayjigwyong rather than his father, but my evidence was circumstantial. This leaves me without a doubt. This picture of the younger Chief Buffalo, not his more-famous father.

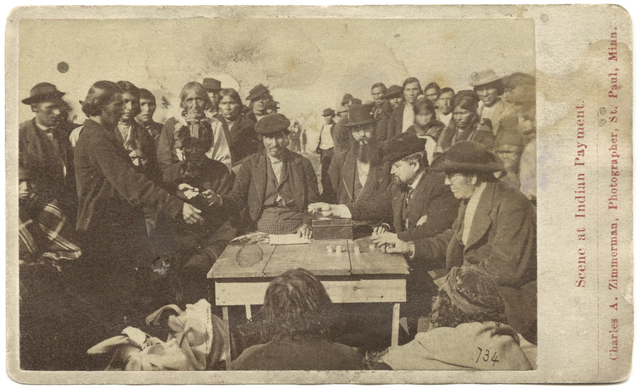

The photo showing an annuity payment, must have been widely distributed in its day, because it has made it’s way into various formats in archives and historical societies around the world. It has also been reproduced in several secondary works including Ronald Satz’ Chippewa Treaty Rights, Patty Loew’s Indian Nations of Wisconsin, Hamilton Ross’ La Pointe: Village Outpost on Madeline Island, and in numerous other pamphlets, videos, and displays in the Chequamegon Region. However, few seem to agree on the basic facts:

When was it taken?

Where was it taken?

Who was the photographer?

Who are the people in the photograph?

We’ll start with a cropped version that seems to be the most popular in reproductions:

According to Hamilton Ross and the Wisconsin Historical Society: “Annuity Payment at La Pointe: Indians receiving payment. Seated on the right is John W. Bell. Others are, left to right, Asaph Whittlesey, Agent Henry C. Gilbert, and William S. Warren (son of Truman Warren).” 1870. Photographer Charles Zimmerman (more info).

In the next one, we see a wider version of the image turned into a souvenir card much like the ones of the chiefs further up the post:

According to the Minnesota Historical Society “Scene at Indian payment, Wisconsin; man in black hat, lower right, is identified as Richard Bardon, Superior, Wisconsin, then acting Indian school teacher and farmer” c.1871 by Charles Zimmerman (more info).

In this version, we can see more foreground and the backs of the two men sitting in front.

According to the Library of Congress: “Cherokee payments(?). Several men seated around table counting coins; large group of Native Americans stand in background.” Published 1870-1900 (more info).

The image also exists in engraved forms, both slightly modified…

According to Benjamin Armstrong: “Annuity papment [sic] at La Pointe 1852” (From Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians)

…and greatly-modified.

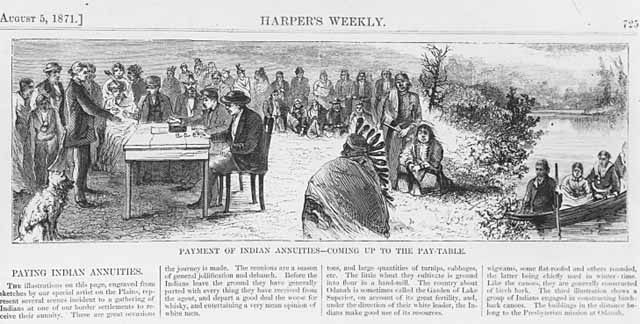

Harper’s Weekly August 5, 1871: “Payment of Indian Annuities–Coming up to the Pay Table.” (more info)

It should also be mentioned that another image exists that was clearly taken on the same day. We see many of the same faces in the crowd:

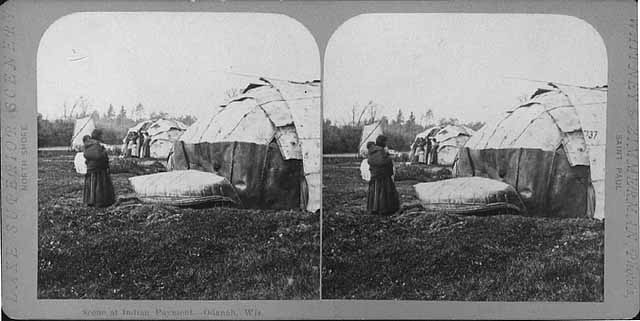

Scene at Indian payment, probably at Odanah, Wisconsin. c.1865 by Charles Zimmerman (more info)

We have a lot of conflicting information here. If we exclude the Library of Congress Cherokee reference, we can be pretty sure that this is an annuity payment at La Pointe or Odanah, which means it was to the Lake Superior Ojibwe. However, we have dates ranging from as early as 1852 up to 1900. These payments took place, interrupted from 1850-1852 by the Sandy Lake Removal, from 1837 to 1874.

Although he would have attended a number of these payments, Benjamin Armstrong’s date of 1852, is too early. A number of secondary sources have connected this photo to dates in the early 1850s, but outside of Armstrong, there is no evidence to support it.

Charles Zimmerman, who is credited as the photographer when someone is credited, became active in St. Paul in the late 1860s, which would point to the 1870-71 dates as more likely. However, if you scroll up the page and look at Giishkitaawag, Akiwenzii, and Aamoons again, you’ll see that these photos, (taken in the early 1860s) are credited to “Whitney & Zimmerman,” even though they predate Zimmerman’s career.

What happened was that Zimmerman partnered with Joel Whitney around 1870, eventually taking over the business, and inherited all Whitney’s negatives (and apparently those of James Martin as well). There must have been an increase in demand for images of Indian peoples in the 1870s, because Zimmerman re-released many of the earlier Whitney images.

So, we’re left with a question. Did Zimmerman take the photograph of the annuity payment around 1870, or did he simply reproduce a Whitney negative from a decade earlier?

I had a hard time finding any primary information that would point to an answer. However, the Summer 1990 edition of the Minnesota History magazine includes an article by Bonnie G. Wilson called Working the Light: Nineteenth Century Professional Photographers in Minnesota. In this article, we find the following:

“…Zimmerman was not a stay-at-home artist. He took some of his era’s finest landscape photos of Minnesota, specializing in stereographs of the Twin Cities area, but also traveling to Odanah, Wisconsin for an Indian annuity payment…”

In the footnotes, Wilson writes:

“The MHS has ten views in the Odanah series, which were used as a basis for engravings in Harper’s Weekly, Aug. 5, 1871. See also Winona Republican, Oct. 12, 1869 p.3;”

Not having access to the Winona Republican, I tried to see how many of the “Odanah series” I could track down. Zimmerman must have sold a lot of stereocards, because this task was surprisingly easy. Not all are labelled as being in Odanah, but the backgrounds are similar enough to suggest they were all taken in the same place. Click on them to view enlarged versions at various digital archives.

Scene at Indian Payment, Odanah Wisconsin (Minnesota Historical Society)

Chippewa Wedding (British Museum)

Domestic Life–Chippewa Indians (British Museum)

Chippewa Wedding (British Museum)

Finally…

So, if Zimmerman took the “Odanah series” in 1869, and the pay table image is part of it, then this is a picture of the 1869 payment. To be absolutely certain, we should try to identify the men in the image.

This task is easier than ever because the New York Public Library has uploaded a high-resolution scan of the Whitney & Zimmerman stereocard version to Wikimedia Commons. For the first time, we can really get a close look at the men and women in this photo.

They say a picture tells a thousand words. I’m thinking I could write ten-thousand and still not say as much as the faces in this picture.

To try to date the photo, I decided to concentrate the six most conspicuous men in the photo:

1) The chief in the fur cap whose face in the shadows.

2) The gray-haired man standing behind him.

3) The man sitting behind the table who is handing over a payment.

4) The man with the long beard, cigar, and top hat.

5) The man with the goatee looking down at the money sitting to the left of the top-hat guy (to the right in our view)

6) The man with glasses sitting at the table nearest the photographer

According to Hamilton Ross, #3 is Asaph Whittlesey, #4 is Agent Henry Gilbert, #5 is William S. Warren (son of Truman), and #6 is John W. Bell. While all four of those men could have been found at annuity payments as various points between 1850 and 1870, this appears to be a total guess by Ross. Three of the four men appear to be of at least partial Native descent and only one (Warren) of those identified by Ross was Ojibwe. Chronologically, it doesn’t add up either. Those four wouldn’t have been at the same table at the same time. Additionally, we can cross-reference two of them with other photos.

Asaph Whittlesey was an interesting looking dude, but he’s not in the Zimmerman photo (Wisconsin Historical Society).

Henry C. Gilbert was the Indian Agent during the Treaty of 1854 and oversaw the 1855 annuity payment, but he was dead by the time the “Zimmerman” photo was taken (Branch County Photographs)

Whittlesey and Gilbert are not in the photograph.

The man who I label as #5 is identified by Ross as William S. Warren. This seems like a reasonable guess, though considering the others, I don’t know that it’s based on any evidence. Warren, who shares a first name with his famous uncle William Whipple Warren, worked as a missionary in this area.

The man I label #6 is called John W. Bell by Ross and Richard Bardon by the Minnesota Historical Society. I highly doubt either of these. I haven’t found photos of either to confirm, but the Ireland-born Bardon and the Montreal-born Bell were both white men. Mr. 6 appears to be Native. I did briefly consider Bell as a suspect for #4, though.

Neither Ross nor the Minnesota Historical Society speculated on #1 or #2.

At this point, I cannot positively identify Mssrs. 1, 2, 3, 5, or 6. I have suspicions about each, but I am not skilled at matching faces, so these are wild guesses at this point:

#1 is too covered in shadows for a clear identification. However, the fact that he is wearing the traditional fur headwrap of an Ojibwe civil chief, along with a warrior’s feather, indicates that he is one of the traditional chiefs, probably from Bad River but possibly from Lac Courte Oreilles or Lac du Flambeau. I can’t see his face well enough to say whether or not he’s in one of the delegation photos from the top of the post.

#2 could be Edawi-giizhig (see above), but I can’t be certain.

#3 is also tricky. When I started to examine this photo, one of the faces I was looking for was that of Joseph Gurnoe of Red Cliff. You can see him in a picture toward the top of the post with the Roy brothers. Gurnoe was very active with the Indian Agency in Bayfield as a clerk, interpreter, and in other positions. Comparing the two photos I can’t say whether or not that’s him. Leave a comment if you think you know.

#5 could be a number of different people.

#6 I don’t have a solid guess on either. His apparent age, and the fact that the Minnesota Historical Society’s guess was a government farmer and schoolteacher, makes me wonder about Henry Blatchford. Blatchford took over the Odanah Mission and farm from Leonard Wheeler in the 1860s. This was after spending decades as Rev. Sherman Hall’s interpreter, and as a teacher and missionary in La Pointe and Odanah area. When this photo was taken, Blatchford had nearly four decades of experience as an interpreter for the Government. I don’t have any proof that it’s him, but he is someone who is easy to imagine having a place at the pay table.

Finally, I’ll backtrack to #4, whose clearly identifiable gray-streaked beard allows us to firmly date the photo. The man is Col. John H. Knight, who came to Bayfield as Indian Agent in 1869.

Col. John H. Knight (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Knight oversaw a couple of annuity payments, but considering the other evidence, I’m confident that the popular image that decorates the sides of the Chequamegon History site was indeed taken at Odanah by Charles Zimmerman at the 1869 annuity payment.

Do you agree? Do you disagree? Have you spotted anything in any of these photos that begs for more investigation? Leave a comment.

As for myself, it’s a relief to finally get all these photo mysteries out of my post backlog. The 1870 date on the Zimmerman photo reminds me that I’m spending too much time in the later 19th century. After all, the subtitle of this website says it’s history before 1860. I think it might be time to go back for a while to the days of the old North West Company or maybe even to Pontiac. Stay tuned, and thanks for reading,