1838 Arrests at La Pointe

April 4, 2024

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

The legendary Gichi-miishen (Michel Cadotte, Sr.) passed away days before the 1837 Treaty of St Peters was signed. One year later his son Michel Cadotte, Jr. and son-in-law Lyman M. Warren were both publicly arrested at the 1838 Annuity Payments in La Pointe, clouding their families’ 1827 Deed for Old La Pointe and 1834 Reinvention of La Pointe.

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs:

La Pointe Agency 1831-1839

National Archives Identifier: 164009310

April 6, 1836

from La Pointe Indian Sub-agency

via Fort Snelling

to Commissioner of Indian Affairs

Received May 21, 1838

Answered May 22, 1838

Lapointe

April 6, 1838

C. A. Harris Esq’r

Com’r In Affs

Sir

I take the liberty of addressing you to ask whether in your opinion there is a probability that my salary can be increased by an act of Congress, or otherwise. I make this enquiry because I feel desirous of keeping this office, and unless the salary can be increased I shall be compelled to resign; the great distance of this place from any market and the expenses of transporting property hither, together [with] the prohibition of entering into trade rendering it at present altogether insufficient. A speedy answer is respectfully solicited.

I am sir with great

Respect your most obdt servant

D. P. Bushnell

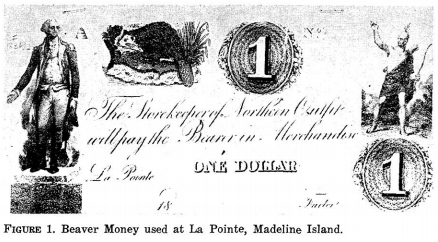

American Fur Company public notice in newspapers nationwide about Lyman M. Warren being removed from La Pointe.

October 27, 1838

from Governor of Wisconsin Territory

to Commissioner of Indian Affairs

received November 19, 1838

Superintendency of Indian Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point Oct. 27 1838.

Hon C. A. Harris

Com. of Ind. Affs.

Sir:

I have the honor to transmit the report of E. F. Ely, Esq. Sup’t of a school at Fond du Lac, Lake Superior, forwarded by Mr D. P. Bushnell, Sub agent at La Pointe, which had not been received at the time the other reports were transmitted.

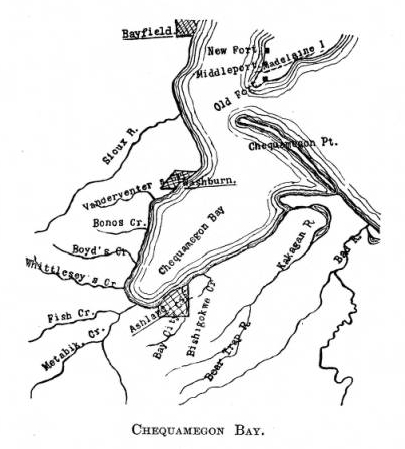

Mr. Bushnell also informs me under date of the 18th Sept. that he has caused Lyman M. Warren, an American citizen, and Michel Cadotte, a half-breed, to be removed from the Indian Country, and has furnished the Dist. Attorney at Green Bay with the necessary evidence and requested him to commence suits against them, for violations of the 12th, 13th & 15th Sections of the act of June 30, 1834. Mr Warren is now here, and suits have been instituted upon the representations of the sub-agent. Further information will be furnished to you as soon as received.

Very respectfully

Your obed’t serv’t

Henry Dodge

Supt Ind. Affs

November 23, 1838

from Lyman M. Warren of La Pointe

via Governor of Wisconsin Territory

to Commissioner of Indian Affairs

Received December 15, 1838

Answered December 22, 1838

Superintendency of Indian Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point Nov 23, 1838.

T. Hartley Crawford Esq’r

Com. of Indian Affairs

Washington

Sir:

Copy of 1834 “Map of La Pointe” by Lyman M. Warren.

I have the honor to transmit enclosed herewith, a communication from Lyman M. Warren, recently of La Pointe, Lake Superior, who, upon charges of a violation of the 12th, 13th & 15th Sections of the “Act to regulate trade and intercourse with the Indian tribes &c,” was removed from the Indian Country. Mr Warren has been long in the service of the American Fur Company at that post, and extensively engaged in Indian trade; and, from the hurried manner in which he was taken from the country, much of his business remains unsettled. He now asks from the Department, for the reasons given in his letter, that he be permitted to return to La Pointe next Spring for the purpose only of settling his business; an indulgence which I think may be safely granted. Mr Warren was the bearer of the information to the Dist. Attorney of the United States at this place, upon which suits were instituted against him, which fact, with that of his previous good standing and the respectability of his connection in this Territory, warrants me in the opinion that no detriment can arise to the Government from a compliance with his request. I have also consulted with the Sub-agent at that station, Mr. Bushnell, who admits the propriety of permitting him to return to the country, for the purposes expressed in his letter, if the agent be not absent. In case the Department should feel disposed to accede to his request, it would be well to instruct the District Attorney not to take any advantage of his absence at the Spring term of the Court, at which he is recognized to answer.

Very respectfully

Your obed’t Servant

Henry Dodge

Supt. Ind. Affs.

Prairie du Chein 7th Nov. 1838

To His Excellency

Henry Doge

Governor of Wisconsin

And Superintendent of

Indian affairs

Sir

Since Michel Cadotte and myself have arrived at this place and been served with process in the various suits brought against us in the name of the United States and given bail for our appearance at the May Term of the Crawford District Court in the Cases where bail was required, I have thought proper to address your Excellency in relation to the course that has been taken against me, and to request through your Excellency, some indulgence from the Department in the management of the Cases from the peculiar circumstances of my situation.

Your Excellency is aware that I was arrested at Lapointe on Lake Superior among the Chippewa Indians by a Military force, without legal process, and brought from thence by the way of the Sault Ste Marys, Mackinac and Green Bay to Fort Winebago from which place I came voluntarily and brought to the complaint against me to your Excellency that after giving bail in one Case at Mineral Point I came to this place whither the Deputy Marshall was sent to execute other process on me and Michel Cadotte. I was arrested and brought away from Lapointe at a time when private business of the greatest importance required my presence there, and my arrest and removal and consequent losses have almost ruined me. On my way I was robbed of upwards of One Thousand Dollars in Cash which is one of the consequences to me of the proceedings that have been commenced against me. I believe that your Excellency is fully aware that if I had been disposed to disregard the laws and authorities of the Country and to set them at defiance the force which was sent for me was not sufficient to bring me away. In fact the Indians in the vicinity were disposed to resists and to prevent my removal, and would have done so if I had not used my influence to restrain them. I mention this as an evidence of my disposition to submit to the laws and authorities of the Government, rather than to oppose or violate either.

I have been a Trader in extensive business among the Chippeways on Lake Superior for upwards of twenty one years, an can appeal with confidence to all intelligent Gentlemen who have been acquainted with my course of conduct throughout that period for testimony that I have always conformed my conduct to the laws of Congress, and the regulations of the Department, when known and understood. I have never knowingly violated either, and if I have ever in any case gone contrary to either, it has been when the law or regulation had not been made known at my remote and far distant station.

No one could expect that so far removed as I have been from settlements and civilization with so little intercourse with either, I could be so well and promptly made acquainted with the legislation and regulations of the Government as those who enjoyed the advantage of a residence within the more immediate sphere of its action and opperations. In the present Case I feel perfectly conscious, that I am free from all blame, and believe that it will be found upon investigation, that the proceedings against me originated in malice.

It is expected I believe that the Half breeds of the Chippeways on Lake Superior will be paid their share of the money donated to them by Treaty, some time early next Spring. It is of great importance to me and to others that I should be present at that payment. I have of my own a large family of children who are interested in the expected payment. Besides I am guardian of an estate which will require my personal presence at that place, in order that it may be settled.

Cadotte is also interested in the payment on his own account, and that of his children. It will be impossible for us to go up in the Spring and return to the Spring terms of the Court at Mineral Point and this place. I would therefore request it as a favor of the Department, if sufficient reason does not appear for dismissing the prosecutions altogether, that I may be permitted with Cadotte to attend at La Pointe in the next Spring season at the contemplated payment, or when ever the same may be made, and that no steps may be taken in the prosecution of the suits against us in our absence, and that the Attorney for the Territory may be directed not to take any default against us in any of the Cases either for want of bail, or plea, or other necessary propositions for our defense, while we may be absent on such business.

I hope that your Excellency will perceive the great importance to me of obtaining this indulgence, and sufficient reason to induce the kind interposition of your Excellency’s good offices to have it granted to me.

With great respect

I am your

Excellency’s Obedient Servant

L. M. Warren

W.718.

December 15, 1838

from Solicitor of the Treasury

to Commissioner of Indian Affairs

Received December 17, 1838

Answered December 22, 1838

and returned papers

from US Attorney Moses McCure Strong

dated November 25, 1838

Office of the Solicitor

of the Treasury

December 15, 1838

T. H. Crawford Esqr.

Comm’r of Indian Affairs.

Sir,

Moses McCure Strong

~ 1878 Historical Atlas of Wisconsin

I have the honor to inclose to you herewith a letter received by this morning’s mail from Messr Strong, United States Attorney for the Territory of Wisconsin, with a copy of one addressed to him by D. P. Burchnell, Indian Sub-agent at Mineral Point, Wisconsin, in relation to sundry suits commenced by him, to recover the penalty incurred for the violation of the 12, 13, & 15 sections of the act of Congress of of 30 June 1834 intitled “an act to regulate trade and intercourse with indian tribes, and to procure peace on the frontiers.”; which suits he states were commenced at the request of Mr. Burchnell.

To enable me to reply to the District Attorney’s letter I shall be obliged by your informing me at your earliest convenience, whether you wish any particular [directions?] given to him on the subject. Please return the District Attorney’s letter with its inclosure.

very respectfully Yours

H. D. Gilpin

Solicitor of the Treasury

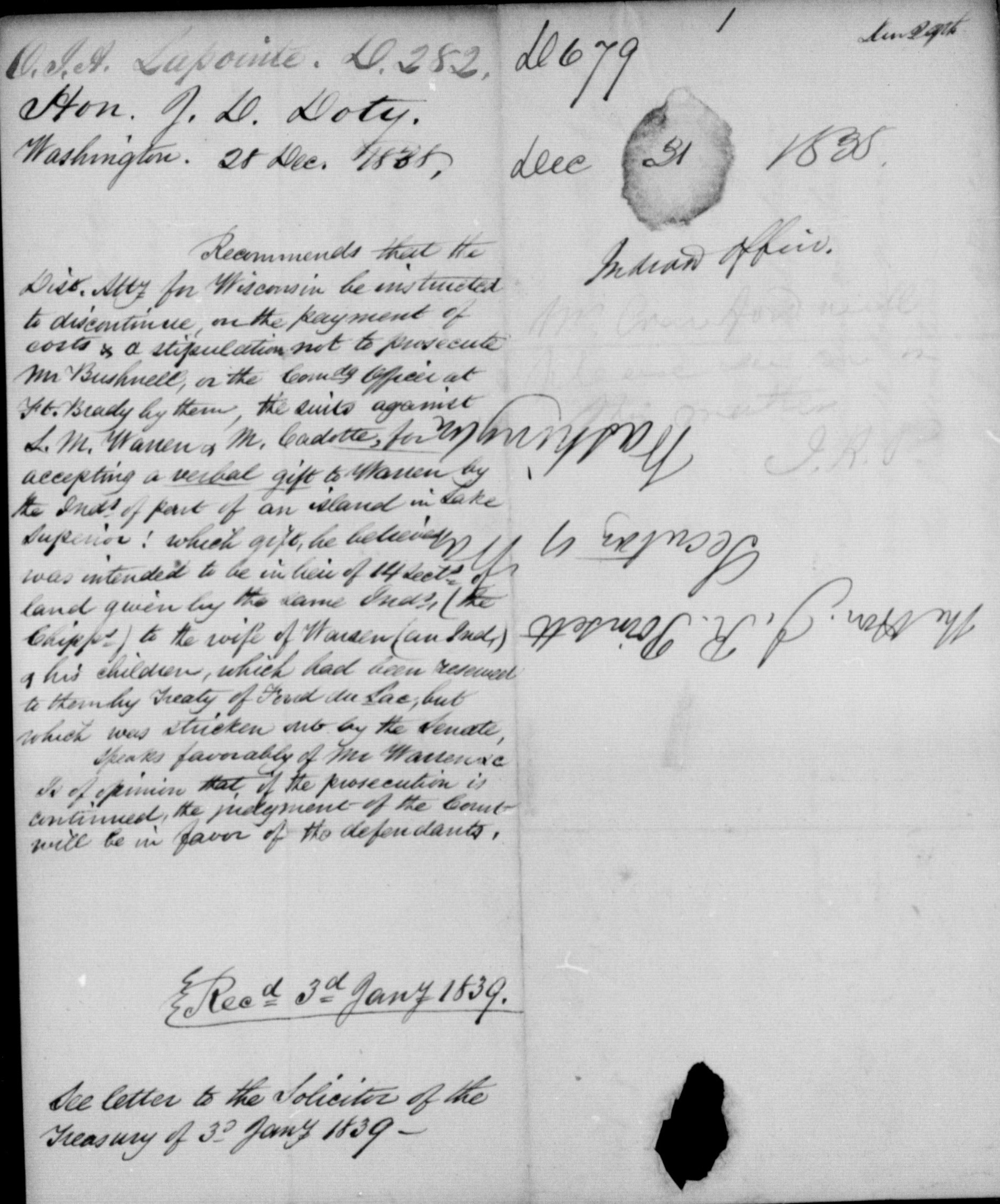

December 28, 1838

from James Duane Doty

to Commissioner of Indian Affairs

forwarded to Secretary of War December 31, 1838

Received January 3, 1839

See letter to Solicitor of the Treasury dated January 3, 1838.

Washington

Dec. 28 1838.

The Hon. J. R. Poinsett

Secy of War

Sir,

1827 Deed for Old La Pointe from Madeline and Michel Cadotte, Sr. to Lyman M. Warren for 2,000 acres of unceded tribal land on Madeline Island to be held in trust for the Cadotte/Warren grandchildren and future generations.

A prosecution was commenced last fall by the Indian Department against Lyman M. Warren, a licensed Trader at Lapointe, Lake Superior and a half Indian by the name of Michel Cadotte, for accepting of a verbal gift to Warren by the Indians of a part of an Island in Lake Superior. This gift I believe was intended to be in lieu of 14 sections of land given by the same Indians to the wife of Warren (an Indian woman, and his children, which had been reserved to them in the Treaty of Fond du Lac, but which was I am informed, stricken out, with other reservations of land, by the Senate.

It appears that Warren was ignorant of the act of Congress on this subject, and that so soon as he was informed, he desisted. Some months afterwards, and without anything new having secured, the sub-agent (then 300 miles from Lapointe) obtained a military force to be sent from Fort Brady to arrest Warren and his interpreter Cadotte. They made no resistance but voluntarily came with the soldiers to the Sault Ste Marie, and thence to Mineral Point 600 miles further.

Mr. Warren has been a Trader in that Country for the last 20 years, and I have personally known him there since the year 1820. During this long period he has been much respected as an upright Trader, submissive to the laws, and at all times disposed to extend the power of this government over the Northern Indians, who it is well known have been most inclined to visit and listen to the British authorities. I do not think there is another Indian Trader in the North West who has a greater influence with those Tribes than Mr. Warren.

The sub-agent, Mr. Bushnell, was a stranger in that country, but recently appointed, and, I cannot but think, has caused Mr. Warren to be arrested without a due examination of the facts of the case, or without giving a proper consideration to the effect it will be likely to have with the Indians of that country.

If Mr. Warren is compelled to defend this suit, whether it results in his favour or not, it must ruin him and his family, and I think the government will lose more than it will gain by continuing the prosecution.

From my knowledge of the parties, the facts of the case and the condition of the country I would respectfully recommend that the District Attorney be directed to discontinue the prosecutions against Warren & Cadotte upon the payment of costs and a stipulation not to prosecute Bushnell and the Commanding Officer at Fort Brady. I have no hesitation in expressing to you the opinion, that if the prosecution is continued the judgement of the Court will be in favour of the defendants.

With much respect I am Sir your obdt svt

J. D. Doty

1837 Petitions from La Pointe to the President

January 29, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs:

La Pointe Agency 1831-1839

National Archives Identifier: 164009310

O. I. A. La Pointe J171.

Hon Geo. W. Jones

Ho. of Reps. Jany 9, 1838

Transmits petition dated 31st Augt 1837, from Michel Cadotte & 25 other Chip. Half Breeds, praying that the amt to be paid them, under the late Chip. treaty, be distributed at La Pointe, and submitting the names of D. P. Bushnell, Lyman M. Warren, for the appt of Comsr to make the distribution.

Transmits it, that it may receive such attention as will secure the objects of the petitioners, says as the treaty has not been satisfied it may be necessary to bring the subject of the petition before the Comsr Ind Affrs of the Senate.

Recd 10 Jany 1838

file

[?] File.

House of Representatives Jany 9th 1838

Sir

I hasten to transmit the inclosed petition, with the hope, that the subject alluded to, may receive such attention, as to secure the object of the petitioners. As the Chippewa Treaty has not yet been ratified it may be necessary to bring the subject of the petition before the Committee of Indian Affairs of the Senate.

I am very respectfully

Your obt svt

Geo W. Jones

C. A. Harris Esqr

Comssr of Indian Affairs

War Department

To the President of the United States of America

The humble petition of the undersigned Chippewa Half-Breeds citizens of the United Sates, respectfully Shareth:

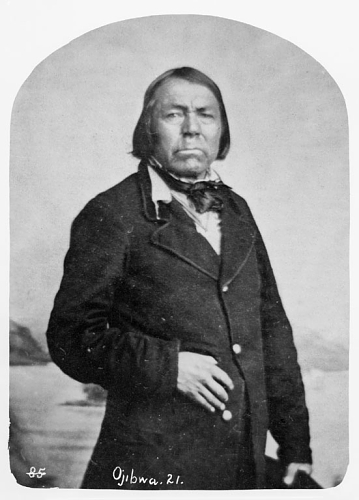

Bizhiki (Buffalo), Dagwagaane (Two Lodges Meet), and Jechiikwii’o (Snipe, aka Little Buffalo) signed the 1837 Treaty of St Peters for the La Pointe Band.

That, your petitioners having lately heard that a Treaty had been concluded between the Government of the United Sates and the Chippewa Indians at St Peters, for the cession of certain lands belonging to that tribe:

ARTICLE 3.

“The sum of one hundred thousand dollars shall be paid by the United States, to the half-

breeds of the Chippewa nation, under the direction of the President. It is the wish of the

Indians that their two sub-agents Daniel P. Bushnell, and Miles M. Vineyard, superintend

the distribution of this money among their half-breed relations.”

That, the said Chippewa Indians X, having a just regard to the interest and welfare of their Half Breed brethren, did there and then stipulate; that, a certain sum of money should be paid once for all unto the said Half-Breeds, to satisfy all claim they might have on the lands so ceded to the United States.

That, your petitioners are ignorant of the time and place where such payment is to be made.

That the great majority of the Half-Breeds entitled to a distribution of said sum of money, are either residing at La Pointe on Lake Superior, or being for the most part earning their livelihood from the Traders, are consequently congregated during the summer months at the aforesaid place.

Your petitioners humbly solicit their father the President, to take their case into consideration, and not subject them to a long and costly journey in ordering the payments to be made at any inconvenient distance, but on the contrary they trust that in his wisdom he will see the justice of their demand in requiring he will be pleased to order the same to be distributed at Lapointe agreeable to their request.

Your petitioners would also intimate that, although they are fully aware that the Executive will make a judicious choice in the appointment of the Commissioners who will be selected to carry into effect the Provisions of said Treaty, yet, they would humbly submit to the President, that they have full confidence in the integrity of D. P. Bushnell Esqr. resident Indian Agent for the United States at this place and Lyman M Warren Esquire, Merchant.

Your petitioners entertain the flattering hope, that, their petition will not be made in vain, and as in duty bound will ever pray.

La Pointe, Lake Superior,

Territory of Wisconsin 31st August 1837

Michel Cadotte

Michel Bosquet X his mark

Seraphim Lacombe X his mark

Joseph Cadotte X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Chs W Borup for wife & Children

A Morrison for wife & children

Pierre Cotte

Henry Cotte X his mark

Frances Roussan X his mark

James Ermatinger for wife & family

Lyman M Warren for wife & family

Joseph Dufault X his mark

Paul Rivet X his mark for wife & family

Charles Chaboullez wife & family

George D. Cameron

Alixis Corbin

Louis Corbin

Jean Bste Denomme X his mark and family

Ambrose Deragon X his mark and family

Robert Morran X his mark ” “

Jean Bst Couvillon X his mark ” “

Alix Neveu X his mark ” “

Frances Roy X his mark ” “

Alixis Brisbant X his mark ” “

Signed in presence of G. Pauchene

John Livingston

O.I.A. La Pointe W424.

Governor of Wisconsin

Mineral Pt. Feby 19, 1838

Transmits the talk of “Buffalo,” a Chip. Chief, delivered at the La Pointe SubAgt, Dec. 9, 1837, asking that the am. due the half-breeds under the late Treaty, be divided fairly among them, & paid them there, as they will not go to St Peters for it, &c.

Says Buffalo has great influence with his tribe, & is friendly to the whites; his sentiments accord with most of those of the half-breeds & Inds in that part of the country.

File

Recd 13 March 1838

[?] File.

Superintendency of Indian Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point, Feby 19, 1838

Sir,

I have the honor to inclose the talk of “Buffalo,” a principal chief of the Chippewa Indians in the vicinity of La Pointe, delivered on the 9th Dec’r last before Mr Bushnell, sub-agent of the Chippewas at that place. Mr. Bushnell remarks that the speech is given with as strict an adherence to the letter as the language will admit, and has no doubt the sentiments expressed by this Chief accord with those of most of the half-breeds and Indians in that place of the Country. The “Buffalo” is a man of great influence among his tribe, and very friendly to the whites.

Very respectfully,

Your obed’t sevt.

Henry Dodge

Supt Ind Affs

Hon C. A. Harris

Com. of Ind. Affairs

Subagency

Lapointe Dec 10 1837

Speech of the Buffalo principal Chief at Lapointe

Father I told you yesterday I would have something to say to you today. What I say to you now I want you to write down, and send it to the Great American Chief that we saw at St Peters last summer, (Gov. Dodge). Yesterday, I called all the Indians together, and have brought them here to hear what I say; I speak the words of all.

ARTICLE 1.

“The said Chippewa nation cede to the United States all that tract of country included

within the following boundaries:

[…]

thence to and along the dividing ridge between the waters of Lake Superior and those of the Mississippi

[…]“

Father it was not my voice, that sold the country last summer. The land was not mine; it belonged to the Indians beyond the mountains. When our Great Father told us at St Peters that it was only the country beyond the mountains that he wanted I was glad. I have nothing to say about the Treaty, good, or bad, because the country was not mine; but when it comes my time I shall know how to act. If the Americans want my land, I shall know what to say. I did not like to stand in the road of the Indians at St Peters. I listened to our Great Father’s words, & said them in my heart. I have not forgotten them. The Indians acted like children; they tried to cheat each other and got cheated themselves. When it comes my time to sell my land, I do not think I shall give it up as they did.

What I say about the payment I do not say on my own account; for myself I do not care; I have always been poor, & don’t want silver now. But I speak for the poor half breeds.

There are a great many of them; more than would fill your house; some of them are very poor They cannot go to St Peters for their money. Our Great Father told us at St Peters, that you would divide the money, among the half breeds. You must not mind those that are far off, but divide it fairly, and give the poor women and children a good share.

Father the Indians all say they will not go to St Peters for their money. Let them divide it in this parts if they choose, but one must have ones here. You must not think you see all your children here; there are so many of them, that when the money and goods are divided, there will not be more than half a Dollar and a breech cloth for each one. At Red Cedar Lake the English Trader (W. Aitken) told the Indians they would not have more than a breech cloth; this set them to thinking. They immediately held a council & their Indian that had the paper (The Treaty) said he would not keep it, and would send it back.

It will not be my place to come in among the first when the money is paid. If the Indians that own the land call me in I shall come in with pleasure.

ARTICLE 4.

“The sum of seventy thousand dollars shall be applied to the payment, by the United States, of certain claims against the Indians; of which amount twenty eight thousand dollars shall, at their request, be paid to William A. Aitkin, twenty five thousand to Lyman M. Warren, and the balance applied to the liquidation of other just demands against them—which they acknowledge to be the case with regard to that presented by Hercules L. Dousman, for the sum of five thousand dollars; and they request that it be paid.“

We are afraid of one Trader. When at St Peters I saw that they worked out only for themselves. They have deceived us often. Our Great Father told us he would pay our old debts. I thought they should be struck off, but we have to pay them. When I heard our debts would be paid, it done my heart good. I was glad; but when I got back here my joy was gone. When our money comes here, I hope our Traders will keep away, and let us arrange our own business, with the officers that the President sends here.

Father I speak for my people, not for myself. I am an old man. My fire is almost out – there is but little smoke. When I set in my wigwam & smoke my pipe, I think of what has past and what is to come, and it makes my heart shake. When business comes before us we will try and act like chiefs. If any thing is to be done, it had better be done straight. The Indians are not like white people; they act very often like children. We have always been good friends to the whites, and we want to remain so. We do not [even?] go to war with our enemies, the Sioux; I tell my young men to keep quiet.

Father I heard the words of our Great Father (Gov. Dodge) last summer, and was pleased; I have not forgotten what he said. I have his words up in my heart. I want you to tell him to keep good courage for us, we want him to do all he can for us. What I have said you have written down; I [?] you to hand him a copy; we don’t know your ways. If I [?] said any thing [?] dont send it. If you think of any thing I ought to say send it. I have always listened to the white men.

O.I.A. Lapointe, B.458

D. P. Bushnell

Lapointe, March 8, 1838

At the request of some of the petitioners, encloses a petition dated 7 March 1838, addressed to the Prest, signed by 167 Chip. half breeds, praying that the amt stipulated by the late Chip. Treaty to be paid to the half breeds, to satisfy all claims they ma have on the lands ceded by this Treaty, may be distributed at Lapointe.

Hopes their request will be complied with; & thinks their annuity should likewise be paid at Lapointe.

File

Recd 2nd May, 1838

Subagency

Lapointe Mch 6 1838

Sir

I have the honor herewith to enclose a petition addressed to the President of the United States, handed to me with a request by several of the petitioners that I would forward it. The justice of the demand of these poor people is so obvious to any one acquainted with their circumstances, that I cannot omit this occasion to second it, and to express a sincere hope that it will be complied with. Indeed, if the convenience and wishes of the Indians are consulted, and as the sum they receive for their country is so small, these should, I conciev, be principle considerations, their annuity will likewise as paid here; for it is a point more convenient of access for the different bands, that almost any other in their own country, and one moreover, where they have interests been in the habit of assembling in the summer months.

I am sir, with great respect,

your most obt servant,

D. P. Bushnell

O. I. A.

C. A. Harris Esqr.

Comr Ind. Affs

To the President of the United States of America

The humble petition of the undersigned Chippewa Half-Breeds citizens of the United States respectfully shareth

That your petitioners having lately heard, that a Treaty has been concluded between the Government of the United States and the Chippewa Indians at St Peters for the cession of certain lands belonging to that tribe;

That the said Chippewa Indians having a just regard to the interest and wellfare of their Half-Breed brethern, did there and then stipulate, that a certain sum of money should be paid once for all unto the said Half-Breeds, to satisfy all claims, they might have on the lands so ceded to the United States;

That your petitioners are ignorant of the time and place, where such payment is to be made; and

That the great majority of the Half-Breeds entitled to a portion of said sum of money are either residing at Lapointe on Lake Superior, or being for the most part earning their livelihood from the Traders, are consequently congregated during the summer months at the aforesaid place;

Your petitioners therefore humbly solicit their Father the President to take their case into consideration, and not subject them to a long and costly journey on ordering the payment to be made at any convenient distance, but on the contrary, they wish, that in his wisdom he will see the justice of this petition and that he will be pleased to order the same to be distributed at Lapointe agreeably to their request.

Your petitioners entertain the flattering hope, that their petition will not be made in vain and as in duly bound will ever pray.

Half Breeds of Folleavoine Lapointe Lac Court Oreilles and Lac du Flambeau

Georg Warren

Edward Warren

William Warren

Truman A Warren

Mary Warren

Michel Cadott

Joseph Cadotte

Joseph Dufault

Frances Piquette X his mark

Michel Bousquet X his mark

Baptiste Bousquet X his mark

Jos Piquette X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Cadotte X his mark

Seraphim Lacombre X his mark

Angelique Larose X her mark

Benjamin Cadotte X his mark

J Bte Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Danis X his mark

Henry Brisette X his mark

Charles Brisette X his mark

Jehudah Ermatinger

William Ermatinger

Charlotte Ermatinger

Larence Ermatinger

Theodore Borup

Sophia Borup

Elisabeth Borup

Jean Bte Duchene X his mark

Agathe Cadotte X her mark

Mary Cadotte X her mark

Charles Cadotte X his mark

Louis Nolin _ his mark

Frances Baillerge X his mark

Joseph Marchand X his mark

Louis Dubay X his mark

Alexis Corbin X his mark

Augustus Goslin X his mark

George Cameron X his mark

Sophia Dufault X her mark

Augt Cadotte No 2 X his mark

Jos Mace _ his mark

Frances Lamoureau X his mark

Charles Morrison

Charlotte L. Morrison

Mary A Morrison

Margerike Morrison

Jane Morrison

Julie Dufault X her mark

Michel Dufault X his mark

Jean Bte Denomme X his mark

Michel Deragon X his mark

Mary Neveu X her mark

Alexis Neveu X his mark

Michel Neveu X his mark

Josette St Jean X her mark

Baptist St Jean X his mark

Mary Lepessier X her mark

Edward Lepessier X his mark

William Dingley X his mark

Sarah Dingley X her mark

John Hotley X his mark

Jeannette Hotley X her mark

Seraphim Lacombre Jun X his mark

Angelique Lacombre X her mark

Felicia Brisette X her mark

Frances Houle X his mark

Jean Bte Brunelle X his mark

Jos Gauthier X his mark

Edward Connor X his mark

Henry Blanchford X his mark

Louis Corbin X his mark

Augustin Cadotte X his mark

Frances Gauthier X his mark

Jean Bte Gauthier X his mark

Alexis Carpentier X his mark

Jean Bte Houle X his mark

Frances Lamieux X his mark

Baptiste Lemieux X his mark

Pierre Lamieux X his mark

Michel Morringer X his mark

Frances Dejaddon X his mark

John Morrison X his mark

Eustache Roussain X his mark

Benjn Morin X his mark

Adolphe Nolin X his mark

Half-Breeds of Fond du Lac

John Aitken

Roger Aitken

Matilda Aitken

Harriet Aitken

Nancy Scott

Robert Fairbanks

George Fairbanks

Jean B Landrie

Joseph Larose

Paul Bellanges X his mark

Jack Belcour X his mark

Jean Belcour X his mark

Paul Beauvier X his mark

Frances Belleaire

Michel Comptois X his mark

Joseph Charette X his mark

Chl Charette X his mark

Jos Roussain X his mark

Pierre Roy X his mark

Joseph Roy X his mark

Vincent Roy X his mark

Jack Bonga X his mark

Jos Morrison X his mark

Henry Cotte X his mark

Charles Chaboillez

Roderic Chaboillez

Louison Rivet X his mark

Louis Dufault X his mark

Louison Dufault X his mark

Baptiste Dufault X his mark

Joseph Dufault X his mark

Chs Chaloux X his mark

Jos Chaloux X his mark

Augt Bellanger X his mark

Bapt Bellanger X his mark

Joseph Bellanger X his mark

Ignace Robidoux X his mark

Charles Robidoux X his mark

Mary Robidoux X her mark

Simon Janvier X his mark

Frances Janvier X his mark

Baptiste Janvier X his mark

Frances Roussain X his mark

Therese Rouleau X his mark

Joseph Lavierire X his mark

Susan Lapointe X her mark

Mary Lapointe X her mark

Louis Gordon X his mark

Antoine Gordon X his mark

Jean Bte Goslin X his mark

Nancy Goslin X her mark

Michel Petit X his mark

Jack Petit X his mark

Mary Petit X her mark

Josette Cournoyer X her mark

Angelique Cournoyer X her mark

Susan Cournoyer X her mark

Jean Bte Roy X his mark

Frances Roy X his mark

Baptist Roy X his mark

Therese Roy X her mark

Mary Lavierge X her mark

Toussaint Piquette X his mark

Josette Piquette X her mark

Susan Montreille X her mark

Josiah Bissel X his mark

John Cotte X his mark

Isabelle Cotte X her mark

Angelique Brebant X her mark

Mary Brebant X her mark

Margareth Bell X her mark

Julie Brebant X her mark

Josette Lefebre X her mark

Sophia Roussain X her mark

Joseph Roussain X his mark

Angelique Roussain X her mark

Joseph Bellair X his mark

Catharine McDonald X her mark

Nancy McDonald X her mark

Mary Macdonald X her mark

Louise Landrie X his mark

In presence of

Chs W Borup

A Morrison

A. D. Newton

Lapointe 7th March 1838

1827 Deed for Old La Pointe

December 27, 2022

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Chief Buffalo and other principal men for the La Pointe Bands of Lake Superior Chippewa began signing treaties with the United States at the 1825 Treaty of Prairie Du Chien; followed by the 1826 Treaty of Fond Du Lac, which reserved Tribal Trust Lands for Chippewa Mixed Bloods along the St. Mary’s River between Lake Superior and Lake Huron:

ARTICLE 4.

The Indian Trade & Intercourse Act of 1790 was the United States of America’s first law regulating tribal land interests:

SEC. 4. And be it enacted and declared, That no sale of lands made by any Indians, or any nation or tribe of Indians the United States, shall be valid to any person or persons, or to any state, whether having the right of pre-emption to such lands or not, unless the same shall be made and duly executed at some public treaty, held under the authority of the United States.

It being deemed important that the half-breeds, scattered through this extensive country, should be stimulated to exertion and improvement by the possession of permanent property and fixed residences, the Chippewa tribe, in consideration of the affection they bear to these persons, and of the interest which they feel in their welfare, grant to each of the persons described in the schedule hereunto annexed, being half-breeds and Chippewas by descent, and it being understood that the schedule includes all of this description who are attached to the Government of the United States, six hundred and forty acres of land, to be located, under the direction of the President of the United States, upon the islands and shore of the St. Mary’s river, wherever good land enough for this purpose can be found; and as soon as such locations are made, the jurisdiction and soil thereof are hereby ceded. It is the intention of the parties, that, where circumstances will permit, the grants be surveyed in the ancient French manner, bounding not less than six arpens, nor more than ten, upon the river, and running back for quantity; and that where this cannot be done, such grants be surveyed in any manner the President may direct. The locations for Oshauguscodaywayqua and her descendents shall be adjoining the lower part of the military reservation, and upon the head of Sugar Island. The persons to whom grants are made shall not have the privilege of conveying the same, without the permission of the President.

The aforementioned Schedule annexed to the 1826 Treaty of Fond du Lac included (among other Chippewa Mixed Blood families at La Pointe) the families of Madeline & Michel Cadotte, Sr. and their American son-in-laws, the brothers Truman A. Warren and Lyman M. Warren:

-

To Michael Cadotte, senior, son of Equawaice, one section.

-

To Equaysay way, wife of Michael Cadotte, senior, and to each of her children living within the United States, one section.

-

To each of the children of Charlotte Warren, widow of the late Truman A. Warren, one section.

-

To Ossinahjeeunoqua, wife of Michael Cadotte, Jr. and each of her children, one section.

-

To each of the children of Ugwudaushee, by the late Truman A. Warren, one section.

-

To William Warren, son of Lyman M. Warren, and Mary Cadotte, one section.

Detail of Michilimackinac County circa 1818 from Michigan as a territory 1805-1837 by C.A. Burkhart, 1926.

~ UW-Milwaukee Libraries

Now, if it seems odd for a Treaty in Minnesota (Fond du Lac) to give families in Wisconsin (La Pointe) lots of land in Michigan (Sault Ste Marie), just remember that these places were relatively ‘close’ to each other in the sociopolitical fabric of Michigan Territory back in 1827. All three places were in Michilimackinac County (seated at Michilimackinac) until 1826, when they were carved off together as part of the newly formed Chippewa County (seated at Sault Ste Marie). Lake Superior remained Unceded Territory until later decades when land cessions were negotiated in the 1836, 1837, 1842, and 1854 Treaties.

Ultimately, the United States removed the aforementioned Schedule from the 1826 Treaty before ratification in 1827.

Several months later, at Michilimackinac, Madeline & Michel Cadotte, Sr. recorded the following Deed to reserve 2,000 acres surrounding the old French Forts of La Pointe to benefit future generations of their family.

Register of Deeds

Michilimackinac County

Book A of Deeds, Pages 221-224

Michel Cadotte and

Magdalen Cadotte

to

Lyman M. Warren

~Deed.

Received for Record

July 26th 1827 at two Six O’Clock A.M.

J.P. King

Reg’r Probate

Bizhiki (Buffalo), Gimiwan (Rain), Kaubuzoway, Wyauweenind, and Bikwaakodowaanzige (Ball of Dye) signed the 1826 Treaty of Fond Du Lac as the Chief and principal men of La Pointe.

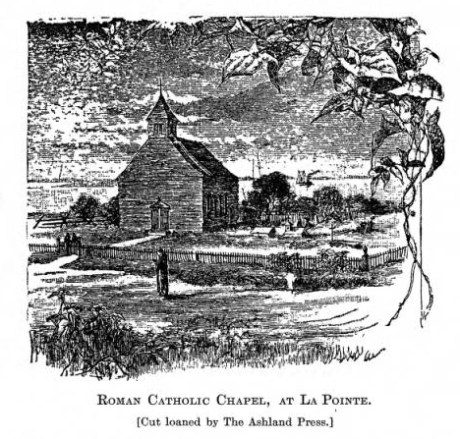

“Copy of 1834 map of La Pointe by Lyman M. Warren“ at Wisconsin Historical Society. Original map (not shown here) is in the American Fur Company papers of the New York Historical Society.

Whereas the Chief and principal men of the Chippeway Tribe of indians, residing on and in the parts adjacent to the island called Magdalen in the western part of Lake Superior, heretofore released and confirmed by Deed unto Magdalen Cadotte a Chippeway of the said tribe, and to her brothers and sisters as tenants in common, thereon, all that part of the said Island called Magdalen, lying south and west of a line commencing on the eastern shore of said Island in the outlet of Great Wing river, and running directly thence westerly to the centre of Sandy bay on the western side of said Island;

and whereas the said brothers and sisters of said Magdalen Cadotte being tenants in common of the said premises, thereafterwards, heretofore, released, conveyed and confirmed unto their sister, the said Magdalen Cadotte all their respective rights title, interest and claim in and to said premises,

and whereas the said Magdalen Cadotte is desirous of securing a portion of said premises to her five grand children viz; George Warren, Edward Warren and Nancy Warren children of her daughter Charlotte Warren, by Truman A. Warren late a trader at said island, deceased, and William Warren and Truman A. Warren children of her daughter Mary Warren by Lyman M. Warren now a trader at said Island;

and whereas the said Magdalen Cadotte is desirous to promote the establishment of a mission on said Island, by and under the direction, patronage and government of the American board of commissioners for foreign missions, according to the plan, wages, and principles and purposes of the said Board.

William Whipple Warren was one of the beneficiary grandchildren named in this Deed.

Now therefore, Know all men by these presents that we Michael Cadotte and Magdalen Cadotte, wife of the said Michael, of said Magdalen Island, in Lake Superior, for and in consideration of one dollar to us in hand paid by Lyman M. Warren, the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged, and for and in consideration of the natural love and affection we bear to our Grandchildren, the said George, Edward, Nancy, William W., and Truman A. Warren, children of our said daughters Charlotte and Mary;

and the further consideration of our great desire to promote the establishment of a mission as aforesaid, under and by the direction, government and patronage of Board aforesaid, have granted, bargained, sold, released, conveyed and confirmed, and by these presents do grant, bargain, sell, release, convey and confirm unto the said Lyman M. Warren his heirs and assigns, out of the aforerecited premises and as part and parcel thereof a certain tract of land on Magdalen Island in Lake Superior, bounded as follows,

Detail of Ojibwemowin placenames on GLIFWC’s webmap.

that is to say, beginning at the most southeasterly corner of the house built and now occupied by said Lyman M. Warren, on the south shore of said Island between this tract and the land of the grantor, thence on the east by a line drawn northerly until it shall intersect at right angles a line drawn westerly from the mouth of Great Wing River to the Centre of Sandy Bay, thence on the north by the last mentioned line westward to a Point in said line, from which a line drawn southward and at right angles therewith would fall on the site of the old fort, so called on the southerly side of said Island; thence on the west by a line drawn from said point and parallel to the eastern boundary of said tract, to the Site of the old fort, so called, thence by the course of the Shore of old Fort Bay to the portage; thence by a line drawn eastwardly to the place of beginning, containing by estimation two thousand acres, be the same more or less, with the appurtenances, hereditaments, and privileges thereto belonging.

To have and to hold the said granted premises to him the said Lyman M. Warren his heirs and assigns: In Trust, Nevertheless, and upon this express condition, that whensoever the said American Board of Commissioners for foreign missions shall establish a mission on said premises, upon the plan, usages, principles and purposes as aforesaid, the said Lyman M. Warren shall forthwith convey unto the american board of commissioners for foreign missions, not less than one quarter nor more than one half of said tract herein conveyed to him, and to be divided by a line drawn from a point in the southern shore of said Island, northerly and parallel with the east line of said tract, and until it intersects the north line thereof.

And as to the residue of the said Estate, the said Lyman M. Warren shall divided the same equally with and amongst the said five children, as tenants in common, and not as joint tenants; and the grantors hereby authorize the said Lyman M. Warren with full powers to fulfil said trust herein created, hereby ratifying and confirming the deed and deeds of said premises he may make for the purpose ~~~

In witness whereof we have hereunto set our respective hands, this twenty fifth day of july A.D. one thousand eight hundred and twenty seven, of Independence the fifty first.

(Signed) Michel Cadotte {Seal}

Magdalen Cadotte X her mark {Seal}

Signed, Sealed and delivered

in presence of us }

Daniel Dingley

Samuel Ashman

Wm. M. Ferry

(on the third page and ninth line from the top the word eastwardly was interlined and from that word the three following lines and part of the fourth to the words “to the place” were erased before the signing & witnessing of this instrument.)

~~~~~~

Territory of Michigan }

County of Michilimackinac }

Be it known that on the twenty sixth day of July A.D. 1827, personally came before me, the subscriber, one of the Justices of the Peace for the County of Michilimackinac, Michel Cadotte and Magdalen Cadotte, wife of the said Michel Cadotte, and the said Magdalen being examined separate and apart from her said husband, each severally acknowledged the foregoing instrument to be their voluntary act and deed for the uses and purposes therein expressed.

(Signed) J. P. King

Just. peace

Cxd

fees Paid $2.25

An Incident of Chegoimegon

November 26, 2016

By Amorin Mello

This is a reproduction of “An Incident of Chegoimegon – 1760” from Report and Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: For the years 1877, 1878 and 1879. Volume VIII., pages 224-226.

—

AN INCIDENT OF CHEGOIMEGON – 1760.*

—

We have been permitted to extract the following from the journal of a gentleman who has seen a large portion of the country to the north and west of this place, and to whose industry our readers have been often indebted for information relating to the portion of country over which he has passed, and to transactions among the numerous tribes, within the limits of this territory, which tend to elucidate their characteristics, and lay open the workings of their untaught minds:

Detail of Isle de la Ronde from Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin; published in Charlevoix’s Histoire et Description Générale de Nouvelle France, Paris, 1744.

Monecauning (abbreviated for “Monegoinaic-cauning,” the Woodpecker Island, in Chippewa language) – which is sometimes called Montreal Island, Cadott’s Island, or Middle Island, and is one of “the Apostles” mentioned by Charlevoix. it is situated in Lake Superior, about ninety miles from Fond du Lac, at the extremity of La Pointe, or Point Chegoimegon.

On this island the French Government had a fort, long previous to its surrender to the English, in 1763. It was garrisoned by regular soldiers, and was the most northern post at which the French king had troops stationed. It was never re-occupied by the English, who removed everything valuable to the Sault de St. Marie, and demolished the works. It is said to have been strongly fortified, and the remains of the works may yet be seen.

In the autumn of 1760, all of the traders except one, who traded from this post, left it for their wintering grounds. He who remained had with him his wife, who was a lady from Montreal, his child – a small boy, and one servant. During the winter, the servant, probably for the purpose of plunder, killed the trader and his wife; and a few days after their death, murdered the child. He continued at the fort until the spring. When the traders came, they enquired for the gentleman and his family; and were told by the servant, that in the month of March, they left him to go to their sugar camp, beyond the bay, since which time he had neither seen nor heard them. The Indians, who were somewhat implicated by this statement, were not well satisfied with it, and determined to examine into its truth. They went out and searched for the family’s tracks; but found none, and their suspicions of the murderer increased. They remained perfectly silent on the subject; and when the snow had melted away, and the frost left the ground, they took sharp stakes and examined around the fort by sticking them into the ground, until they found three soft spots a short distance from each other, and digging down they discovered the bodies.

The servant was immediately seized and sent off in an Indian canoe, for Montreal, for trial. When passing the Longue Saut, in the river St. Lawrence, the Indians who had him in charge, were told of the advances of the English upon Montreal, and that they could not in safety proceed to that place. They at once became a war party, – their prisoner was released, and he joined and fought with them. Having no success, and becoming tired of the war, they sought their own land – taking the murderer with them as one of their war party.

They had nearly reached the Saut de St. Marie, when they held a dance. During the dance, as is usual, each one “struck the post,” and told, in his manner, of his exploits. The murderer, in his turn, danced up to the post, and boasted that he had killed the trader and his family – relating all the circumstances attending the murder. The chief heard him in silence, saving the usual grunt, responsive to the speaker. The evening passed away, and nothing farther occurred.

The next day the chief called his young men aside, and said to them: “Did you not hear this man’s speech last night? He now says that he did the murder with which we charged him. He ought not to have boasted of it. We boast of having killed our enemies – never our friends. Now he is going back to the place where committed the act, and where we live – perhaps he will again murder. He is a bad man – neither we nor our friends are safe. If you are of my mind, we will strike this man on the head.” They all declared themselves of his opinion, and determined that justice should be rendered him speedily and effectually.

They continued encamped, and made a feast, to which the murderer was invited to partake. They filled his dish with an extravagant quantity, and when he commenced his meal, the chief informed him, in a few words, of the decree in council, and that as soon as he had finished his meal, either by eating the whole his dish contained, or as much as he could, the execution was to take place. The murderer, now becoming sensible of his perilous situation, from the appearance of things around him, availed himself of the terms of the sentence he had just heard pronounced, and did ample justice to the viands. He continued, much to the discomfiture of the “phiz” of justice (personified by the chief, who all the while sat smoking through his nose), eating and drinking until he had sat as long as a modern alderman at a corporation dinner. But it was of no avail – when he ceased eating he ceased breathing.

The chief cut up the body of the murderer, and boiled it for another feast – but his young men would touch none of it – they said, “he was not worthy to be eaten – he was worse than a bad dog. We will not taste him, for if we do, we shall be worse than dogs ourselves.”

Mr. Morrison, who gave me the above relation, told me he had it from a very old Indian, who was present at the death of the murderer.

* – This paper was originally published in the Detroit Gazette, Aug. 30, 1822. Hon. C. C. Throwbridge of Detroit, a resident of that place for sixty years, states that Mr. Schoolcraft, without doubt, contributed this sketch to the Gazette; that Mr. Schoolcraft, at the time of its publication, was residing at the Saut St. Marie: and Mr. Morrison, who was one of Mr. Astor’s most trusted agents at “L’Anse Qui-wy-we-nong,” came down to Mackinaw every summer, and thus gave Mr. Schoolcraft the information.

L. C. D.

Perrault, Curot, Nelson, and Malhoit

March 8, 2014

I’ve been getting lazy, lately, writing all my posts about the 1850s and later. It’s easy to find sources about that because they are everywhere, and many are being digitized in an archival format. It takes more work to write a relevant post about the earlier eras of Chequamegon History. The sources are sparse, scattered, and the ones that are digitized or published have largely been picked over and examined by other researchers. However, that’s no excuse. Those earlier periods are certainly as interesting as the mid-19th Century. I needed to just jump in and do a project of some sort.

I’m someone who needs to know the names and personalities involved to truly wrap my head around a history. I’ve never been comfortable making inferences and generalizations unless I have a good grasp of the specific. This doesn’t become easy in the Lake Superior country until after the Cass Expedition in 1820.

But what about a generation earlier?

The dawn of the 19th-century was a dynamic time for our region. The fur trade was booming under the British North West Company. The Ojibwe were expanding in all directions, especially to west, and many of familiar French surnames that are so common in the area arrived with Canadian and Ojibwe mix-blooded voyageurs. Admittedly, the pages of the written record around 1800 are filled with violence and alcohol, but that shouldn’t make one lose track of the big picture. Right or wrong, sustainable or not, this was a time of prosperity for many. I say this from having read numerous later nostalgic accounts from old chiefs and voyageurs about this golden age.

We can meet some of the bigger characters of this era in the pages of William W. Warren and Henry Schoolcraft. In them, men like Mamaangazide (Mamongazida “Big Feet”) and Michel Cadotte of La Pointe, Beyazhig (Pay-a-jick “Lone Man) of St. Croix, and Giishkiman (Keeshkemun “Sharpened Stone”) of Lac du Flambeau become titans, covered with glory in trade, war, and influence. However, there are issues with these accounts. These two authors, and their informants, are prone toward glorifying their own family members. Considering that Schoolcraft’s (his mother-in law, Ozhaawashkodewike) and Warren’s (Flat Mouth, Buffalo, Madeline and Michel Cadotte Jr., Jean Baptiste Corbin, etc.) informants were alive and well into adulthood by 1800, we need to keep things in perspective.

The nature of Ojibwe leadership wasn’t different enough in that earlier era to allow for a leader with any more coercive power than that of the chiefs in 1850s. Mamaangazide and his son Waabojiig may have racked up great stories and prestige in hunting and war, but their stature didn’t get them rich, didn’t get them out of performing the same seasonal labors as the other men in the band, and didn’t guarantee any sort of power for their descendants. In the pages of contemporary sources, the titans of Warren and Schoolcraft are men.

Finally, it should be stated that 1800 is comparatively recent. Reading the journals and narratives of the Old North West Company can make one feel completely separate from the American colonization of the Chequamegon Region in the 1840s and ’50s. However, they were written at a time when the Americans had already claimed this area for over a decade. In fact, the long knife Zebulon Pike reached Leech Lake only a year after Francois Malhoit traded at Lac du Flambeau.

The Project

I decided that if I wanted to get serious about learning about this era, I had to know who the individuals were. The most accessible place to start would be four published fur-trade journals and narratives: those of Jean Baptiste Perrault (1790s), George Nelson (1802-1804), Michel Curot (1803-1804), and Francois Malhoit (1804-1805).

The reason these journals overlap in time is that these years were the fiercest for competition between the North West Company and the upstart XY Company of Sir Alexander MacKenzie. Both the NWC traders (such as Perrault and Malhoit) and the XY traders (Nelson and Curot) were expected to keep meticulous records during these years.

I’d looked at some of these journals before and found them to be fairly dry and lacking in big-picture narrative history. They mostly just chronicle the daily transactions of the fur posts. However, they do frequently mention individual Ojibwe people by name, something that can be lacking in other primary records. My hope was that these names could be connected to bands and villages and then be cross-referenced with Warren and Schoolcraft to fill in some of the bigger story. As the project took shape, it took the form of a map with lots of names on it. I recorded every Ojibwe person by name and located them in the locations where they met the traders, unless they are mentioned specifically as being from a particular village other than where they were trading.

I started with Perrault’s Narrative and tried to record all the names the traders and voyageurs mentioned as well. As they were mobile and much less identified with particular villages, I decided this wasn’t worth it. However, because this is Chequamegon History, I thought I should at least record those “Frenchmen” (in quotes because they were British subjects, some were English speakers, and some were mix-bloods who spoke Ojibwe as a first language) who left their names in our part of the world. So, you’ll see Cadotte, Charette, Corbin, Roy, Dufault (DeFoe), Gauthier (Gokee), Belanger, Godin (Gordon), Connor, Bazinet (Basina), Soulierre, and other familiar names where they were encountered in the journals. I haven’t tried to establish a complete genealogy for either, but I believe Perrault (Pero) and Malhoit (Mayotte) also have names that are still with us.

For each of the names on the map, I recorded the narrative or journal they appeared in:

JBP= Jean Baptiste Perrault

GN= George Nelson

MC= Michel Curot

FM= Francois Malhoit

Red Lake-Pembina area: By this time, the Ojibwe had started to spread far beyond the Lake Superior forests and into the western prairies. Perrault speaks of the Pillagers (Leech Lake Band) being absent from their villages because they had gone to hunt buffalo in the west. Vincent Roy Sr. and his sons later settled at La Pointe, but their family maintained connections in the Canadian borderlands. Jean Baptiste Cadotte Jr. was the brother of Michel Cadotte (Gichi-Mishen), the famous La Pointe trader.

Leech Lake and Sandy Lake area: The names that jump out at me here are La Brechet or Gaa-dawaabide (Broken Tooth), the great Loon-clan chief from Sandy Lake (son of Bayaaswaa mentioned in this post) and Loon’s Foot (Maangozid). The Maangozid we know as the old speaker and medicine man from Fond du Lac (read this post) was the son of Gaa-dawaabide. He would have been a teenager or young man at the time Perrault passed through Sandy Lake.

Fond du Lac and St. Croix: Augustin Belanger and Francois Godin had descendants that settled at La Pointe and Red Cliff. Jean Baptiste Roy was the father of Vincent Roy Sr. I don’t know anything about Big Marten and Little Marten of Fond du Lac or Little Wolf of the St. Croix portage, but William Warren writes extensively about the importance of the Marten Clan and Wolf Clan in those respective bands. Bayezhig (Pay-a-jick) is a celebrated warrior in Warren and Giishkiman (Kishkemun) is credited by Warren with founding the Lac du Flambeau village. Buffalo of the St. Croix lived into the 1840s. I wrote about his trip to Washington in this post.

Lac Courte Oreilles and Chippewa River: Many of the men mentioned at LCO by Perrault are found in Warren. Little (Petit) Michel Cadotte was a cousin of the La Pointe trader, Big (Gichi/La Grande) Michel Cadotte. The “Red Devil” appears in Schoolcraft’s account of 1831. The old, respected Lac du Flambeau chief Giishkiman appears in several villages in these journals. As the father of Keenestinoquay and father-in-law of Simon Charette, a fur-trade power couple, he traded with Curot and Nelson who worked with Charette in the XY Company.

La Pointe: Unfortunately, none of the traders spent much time at La Pointe, but they all mention Michel Cadotte as being there. The family of Gros Pied (Mamaangizide, “Big Feet”) the father of Waabojiig, opened up his lodge to Perrault when the trader was waylaid by weather. According to Schoolcraft and Warren, the old war chief had fought for the French on the Plains of Abraham in 1759.

Lac du Flambeau: Malhoit records many of the same names in Lac du Flambeau that Nelson met on the Chippewa River. Simon Charette claimed much of the trade in this area. Mozobodo and “Magpie” (White Crow), were his brothers-in-law. Since I’ve written so much about chiefs named Buffalo, I should point out that there’s an outside chance Le Taureau (presumably another Bizhiki) could be the famous Chief Buffalo of La Pointe.

L’Anse, Ontonagon, and Lac Vieux Desert: More Cadottes and Roys, but otherwise I don’t know much about these men.

At Mackinac and the Soo, Perrault encountered a number of names that either came from “The West,” or would find their way there in later years. “Cadotte” is probably Jean Baptiste Sr., the father of “Great” Michel Cadotte of La Pointe.

Malhoit meets Jean Baptiste Corbin at Kaministiquia. Corbin worked for Michel Cadotte and traded at Lac Courte Oreilles for decades. He was likely picking up supplies for a return to Wisconsin. Kaministiquia was the new headquarters of the North West Company which could no longer base itself south of the American line at Grand Portage.

Initial Conclusions

There are many stories that can be told from the people listed in these maps. They will have to wait for future posts, because this one only has space to introduce the project. However, there are two important concepts that need to be mentioned. Neither are new, but both are critical to understanding these maps:

1) There is a great potential for misidentifying people.

Any reading of the fur-trade accounts and attempts to connect names across sources needs to consider the following:

- English names are coming to us from Ojibwe through French. Names are mistranslated or shortened.

- Ojibwe names are rendered in French orthography, and are not always transliterated correctly.

- Many Ojibwe people had more than one name, had nicknames, or were referenced by their father’s names or clan names rather than their individual names.

- Traders often nicknamed Ojibwe people with French phrases that did not relate to their Ojibwe names.

- Both Ojibwe and French names were repeated through the generations. One should not assume a name is always unique to a particular individual.

So, if you see a name you recognize, be careful to verify it’s reall the person you’re thinking of. Likewise, if you don’t see a name you’d expect to, don’t assume it isn’t there.

2) When talking about Ojibwe bands, kinship is more important than physical location.

In the later 1800s, we are used to talking about distinct entities called the “St. Croix Band” or “Lac du Flambeau Band.” This is a function of the treaties and reservations. In 1800, those categories are largely meaningless. A band is group made up of a few interconnected families identified in the sources by the names of their chiefs: La Grand Razeur’s village, Kishkimun’s Band, etc. People and bands move across large areas and have kinship ties that may bind them more closely to a band hundreds of miles away than to the one in the next lake over.

I mapped here by physical geography related to trading posts, so the names tend to group up. However, don’t assume two people are necessarily connected because they’re in the same spot on the map.

On a related note, proximity between villages should always be measured in river miles rather than actual miles.

Going Forward

I have some projects that could spin out of these maps, but for now, I’m going to set them aside. Please let me know if you see anything here that you think is worth further investigation.

Sources:

Curot, Michel. A Wisconsin Fur Trader’s Journal, 1803-1804. Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites. Wisconsin Historical Collections, vol. XX: 396-472, 1911.

Malhoit, Francois V. “A Wisconsin Fur Trader’s Journal, 1804-05.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Reuben Gold Thwaites. Vol. 19. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1910. 163-225. Print.

Nelson, George, Laura L. Peers, and Theresa M. Schenck. My First Years in the Fur Trade: The Journals of 1802-1804. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 2002. Print.

Perrault, Jean Baptiste. Narrative of The Travels And Adventures Of A Merchant Voyager In The Savage Territories Of Northern America Leaving Montreal The 28th of May 1783 (to 1820) ed. and Introduction by, John Sharpless Fox. Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections. vol. 37. Lansing: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, Crawford Co., 1900.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Information Respecting The History,Condition And Prospects OF The Indian Tribes Of The United States. Illustrated by Capt. S. Eastman. Published by the Authority of Congress. Part III. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Company, 1953.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi. East Lansing: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Fun With Maps

June 28, 2013

I’m someone who loves a good historical map, so one of my favorite websites is memory.loc.gov, the digital collections of the Library of Congress. You can spend hours zooming in on neat vintage maps. This post has snippets from eleven of them, stretching from 1674 to 1843. They are full of cool old inaccuracies, but they also highlight important historical trends and eras in our history. This should not be considered an exhaustive survey of the best maps out there, nor is it representative of all the LOC maps. Really, it’s just 11 semi-random maps with my observations on what I found interesting. Click on any map to go to the Library of Congress site where you can browse more of it. Enjoy:

French 1674

Nouvelle decouverte de plusieurs nations dans la Nouvelle France en l’année 1673 et 1674 by Louis Joliet. Joliet famously traveled from the Great Lakes down the Mississippi with the Jesuit Jacques Marquette in 1673.

- Cool trees.

- Baye des Puans: The French called the Ho-Chunk Puans, “Stinky People.” That was a translation of the Ojibwe word Wiinibiigoo (Winnebago), which means “stinky water people.” Green Bay is “green” in summer because of the stinky green algae that covers it. It’s not surprising that the Ho-Chunk no longer wish to be called the Winnebago or Puans.

- 8tagami: The French used 8 in Indian words for the English sound “W.” 8tagami (Odagami) is the Ojibwe/Odawa/Potawatomi word for the Meskwaki (Fox) People.

- Nations du Nord: To the French, the country between Lake Superior and Hudson Bay was the home of “an infinity of nations,” (check out this book by that title) small bands speaking dialects of Ojibwe, Cree, and Assiniboine Sioux.

- The Keweenaw is pretty small, but Lake Superior has generally the right shape.

French 1688

Carte de l’Amerique Septentrionnale by Jean Baptiste Louis Franquelin: Franquelin created dozens of maps as the royal cartographer and hydrographer of New France.

- Lake Superior is remarkably accurate for this time period.

- Nations sous le nom d’Outouacs: “Nations under the name of Ottawas”–the French had a tendency to lump all Anishinaabe peoples in the west (Ojibwe, Ottawa, Potawatomi, etc.) under the name Outouais or Outouacs.

- River names, some are the same and some have changed. Bois Brule (Brule River) in French is “burnt wood” a translation of the Ojibwe wiisakode. I see ouatsicoto inside the name of the Brule on this map (Neouatsicoton), but I’m not 100% sure that’s wiisakode. Piouabic (biwaabik is Ojibwe word for Iron) for the Iron River is still around. Mosquesisipi (Mashkiziibi) or Swampy River is the Ojibwe for the Bad River.

- Madeline Island is Ile. St. Michel, showing that it was known at “Michael’s Island” a century before Michel Cadotte established his fur post.

- Ance Chagoüamigon: Point Chequamegon

French 1703

Carte de la riviere Longue : et de quelques autres, qui se dechargent dans le grand fleuve de Missisipi [sic] … by Louis Armand the Baron de Lahontan. Baron Lahontan was a military officer of New France who explored the Mississippi and Missouri River valleys.

- Lake Superior looks quite strange.

- “Sauteurs” and Jesuits at Sault Ste. Marie: the French called the Anishinaabe people at Sault Ste. Marie (mostly Crane Clan) the Sauteurs or Saulteaux, meaning “people of the falls.” This term came to encompass most of the people who would now be called Ojibwe.

- Fort Dulhut: This is not Duluth, Minnesota, but rather Kaministiquia (modern-day Thunder Bay). It is named for the same person–Daniel Greysolon, the Sieur du Lhut (Duluth).

- Riviere Du Tombeau: “The River of Tombs” at the west end of the Lake is the St. Croix River, which does not actually flow into Lake Superior but connects it to the Mississippi over a short portage from the Brule River.

- Chagouamigon (Chequamegon) is placed much too far to the east.

- The Fox River is gigantic flowing due east rather than north into Green Bay. We see the “Savage friends of the French:” Outagamis (Meskwaki/Fox), Malumins (Menominee), and Kikapous (Kickapoo).

French 1742

Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques N. Bellin 1742. Bellin was a famous European mapmaker who compiled various maps together. The top map is a detail from the Carte de Lacs. The bottom one is from a slightly later map.

- Of the maps shown so far, this has the best depiction of Chequamegon, but Lake Superior as a whole is much less accurate than on Franquelin’s map from fifty years earlier.

- The mysterious “Isle Phillipeaux,” a second large island southeast of Isle Royale shows prominently on this map. Isle Phillipeaux is one of those cartographic oddities that pops up on maps for decades after it first appears even though it doesn’t exist.

- Cool river names not shown on Franquelin’s map: Atokas (Cranberry River) and Fond Plat “Flat-bottom” (Sand River)

- The region west of today’s Herbster, Wisconsin is lablled “Papoishika.” I did an extensive post about an area called Ka-puk-wi-e-kah in that same location.

- Ici etoit une Bourgade Considerable: “Here there was a large village.” This in reference to when Chequamegon was a center for the Huron, Ottawa (Odawa) and other refugee nations of the Iroquois Wars in the mid-1600s.

- “La Petite Fille”: Little Girl’s Point.

- Chequamegon Bay is Baye St. Charles

- Catagane: Kakagon, Maxisipi: Mashkizibi

- The islands are “The 12 Apostles.”

British 1778

A new map of North America, from the latest discoveries 1778. Engrav’d for Carver’s Travels. In 1766 Jonathan Carver became one of the first Englishmen to pass through this region. His narrative is a key source for the time period directly following the conquest of New France, when the British claimed dominion over the Great Lakes.

- Lake Superior still has two giant islands in the middle of it.

- The Chipeway (Ojibwe), Ottaway (Odawa), and Ottagamie (Meskwaki/Fox) seem to have neatly delineated nations. The reality was much more complex. By 1778, the Ojibwe had moved inland from Lake Superior and were firmly in control of areas like Lac du Flambeau and Lac Courte Oreilles, which had formerly been contested by the Meskwaki.

Dutch 1805

Charte von den Vereinigten Staaten von Nord-America nebst Louisiana by F.L. Gussefeld: Published in Europe.

- The Dutch never had a claim to this region. In fact, this is a copy of a German map. However, it was too cool-looking to pass up.

- Over 100 years after Franquelin’s fairly-accurate outline of Lake Superior, much of Europe was still looking at this junk.

- “Ober See” and Tschippeweer” are funny to me.

- Isle Phillipeau is hanging on strong into the nineteenth century.

American 1805

A map of Lewis and Clark’s track across the western portion of North America, from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean : by order of the executive of the United States in 1804, 5 & 6 / copied by Samuel Lewis from the original drawing of Wm. Clark. This map was compiled from the manuscript maps of Lewis and Clark.

- The Chequamegon Region supposedly became American territory with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. The reality on the ground, however, was that the Ojibwe held sovereignty over their lands. The fur companies operating in the area were British-Canadian, and they employed mostly French-Ojibwe mix-bloods in the industry.

- This is a lovely-looking map, but it shows just how little the Americans knew about this area. Ironically, British Canada is very well-detailed, as is the route of Lewis and Clark and parts of the Mississippi that had just been visited by the American, Lt. Zebulon Pike.

- “Point Cheganega” is a crude islandless depiction of what we would call Point Detour.

- The Montreal River is huge and sprawling, but the Brule, Bad, and Ontonagon Rivers do not exist.

- To this map’s credit, there is only one Isle Royale. Goodbye Isle Phillipeaux. It was fun knowing you.

- It is striking how the American’s had access to decent maps of the British-Canadian areas of Lake Superior, but not of what was supposedly their own territory.

English 1811

A new map of North America from the latest authorities By John Cary of London. This map was published just before the outbreak of war between Britain and the United States.

- These maps are starting to look modern. The rivers are getting more accurate and the shape of Lake Superior is much better–though the shoreline isn’t done very well.

- Burntwood=Brule, Donagan=Ontonagon

- The big red line across Lake Superior is the US-British border. This map shows Isle Royale in Canada. The line stops at Rainy Lake because the fate of the parts of Minnesota and North Dakota in the Hudson Bay Watershed (claimed by the Hudson Bay Company) was not yet settled.

- “About this place a settlement of the North West Company”: This is Michel Cadotte’s trading post at La Pointe on Madeline Island. Cadotte was the son of a French trader and an Anishinaabe woman, and he traded for the British North West Company.

- It is striking that a London-made map created for mass consumption would so blatantly show a British company operating on the American side of the line. This was one of the issues that sparked the War of 1812. The Indian nations of the Great Lakes weren’t party to the Treaty of Paris and certainly did not recognize American sovereignty over their lands. They maintained the right to have British traders. America didn’t see it that way.

American 1820

Map of the United States of America : with the contiguous British and Spanish possessions / compiled from the latest & best authorities by John Melish

- Lake Superior shape and shoreline are looking much better.

- Bad River is “Red River.” I’ve never seen that as an alternate name for the Bad. I’m wondering if it’s a typo from a misreading of “bad”

- Copper mines are shown on the Donagon (Ontonagon) River. Serious copper mining in that region was still over a decade away. This probably references the ancient Indian copper-mining culture of Lake Superior or the handful of exploratory attempts by the French and British.

- The Brule-St. Croix portage is marked “Carrying Place.”

- No mention of Chequamegon or any of the Apostle Islands–just Sand Point.

- Isle Phillipeaux lives! All the way into the 1820s! But, it’s starting to settle into being what it probably was all along–the end of the Keweenaw mistakenly viewed from Isle Royale as an island rather than a peninsula.

American 1839

From the Map of Michigan and part of Wisconsin Territory, part of the American Atlas produced under the direction of U.S. Postmaster General David H. Burr.

- Three years before the Ojibwe cede the Lake Superior shoreline of Wisconsin, we see how rapidly American knowledge of this area is growing in the 1830s.

- The shoreline is looking much better, but the islands are odd. Stockton (Presque Isle) and Outer Island have merged into a huge dinosaur foot while Madeline Island has lost its north end.

- Weird river names: Flagg River is Spencer’s, Siskiwit River is Heron, and Sand River is Santeaux. Fish Creek is the gigantic Talking Fish River, and “Raspberry” appears to be labeling the Sioux River rather than the farther-north Raspberry River.

- Points: Bark Point is Birch Bark, Detour is Detour, and Houghton is Cold Point. Chequamegon Point is Chegoimegon Point, but the bay is just “The Bay.”

- The “Factory” at Madeline Island and the other on Long Island refers to a fur post. This usage is common in Canada: Moose Factory, York Factory, etc. At this time period, the only Factory would have been on Madeline.

- The Indian Village is shown at Odanah six years before Protestant missionaries supposedly founded Odanah. A commonly-heard misconception is that the La Pointe Band split into Island and Bad River factions in the 1840s. In reality, the Ojibwe didn’t have fixed villages. They moved throughout the region based on the seasonal availability of food. The traders were on the island, and it provided access to good fishing, but the gardens, wild rice, and other food sources were more abundant near the Kakagon sloughs. Yes, those Ojibwe married into the trading families clustered more often on the Island, and those who got sick of the missionaries stayed more often at Bad River (at least until the missionaries followed them there), but there was no hard and fast split of the La Pointe Band until long after Bad River and Red Cliff were established as separate reservations.

American 1843

Hydrographical basin of the upper Mississippi River from astronomical and barometrical observations, surveys, and information by Joseph Nicollet. Nicollet is considered the first to accurately map the basin of the Upper Mississippi. His Chequamegon Region is pretty good also.

- You may notice this map decorating the sides of the Chequamegon History website.

- This post mentions this map and the usage of Apakwa for the Bark River.

- As with the 1839 map, this map’s Raspberry River appears to be the Sioux rather than the Miskomin (Raspberry) River.

- Madeline Island has a little tail, but the Islands have their familiar shapes.

- Shagwamigon, another variant spelling

- Mashkeg River: in Ojibwe the Bad River is Mashkizibi (Swamp River). Mashkiig is the Ojibwe word for swamp. In the boreal forests of North America, this word had migrated into English as muskeg. It’s interesting how Nicollet labels the forks, with the White River fork being the most prominent.