1842 Treaty Speeches at La Pointe in the News

May 15, 2024

Collected by Amorin Mello & edited by Leo Filipczak

Robert Stuart was a top official in Astor’s American Fur Company in the upper Great Lakes region. Apparently, it was not a conflict of interest for him to also be U.S. Commissioner for a treaty in which the Fur Company would be a major beneficiary.

A gentleman who has recently returned from a visit to the Lake Superior Indian country, has furnished us with the particulars of a Treaty lately negotiated at La Pointe, during his sojourn at that place, by ROBERT STUART, Esq., Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the district of Michigan, on the part of the United States, and by the Chiefs and Braves of the Chippeway Indian nation on their own behalf and their people. From 3 to 4000 Indians were present, and the scene presented an imposing appearance. The object of the Government was the purchase of the Chippeway country for its valuable minerals, and to adopt a policy which is practised by Great Britain, i.e. of keeping intercourse with these powerful neighbors from year to year by paying them annuities and cultivating their friendship. It is a peculiar trait in the Indian character of being very punctual in regard to the fulfillment of any contract into which they enter, and much dissatisfaction has arisen among the different tribes toward our Government, in consequence of not complying strictly to the obligations on their part to the Indians, in the time of making the payments, for they are not generally paid until after the time stipulated in the treaty, and which has too often proven to be the means of losing their confidence and friendship.

On the 30th of September last, Mr. Stuart opened the Council, standing himself and some of his friends under an awning prepared for the occasion, and the vast assembly of the warlike Chippeways occupying seats which were arranged for their accommodation. A keg of Tobacco was rolled out and opened as a present to the Indians, and was distributed among them; when Mr. Stuart addressed them as follows:-

The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was a metaphor for infinite abundance in 1842. In less than 75 years, the species would be extinct. What that means for Stuart’s metaphor is hard to say (Biodiversity Heritage Library).

The chiefs who had been to Washington were the St. Croix chiefs Noodin (pictured below) and Bizhiki. They were brought to the capital as part of a multi-tribal delegation in 1824, which among other things, toured American military facilities.I am very glad to meet and shake hands with so many of my old friends in good health; last winter I visited your Great Father in Washington, and talked with him about you. He knows you are poor and have but little for your women and children, and that your lands are poor. He pities your condition, and has sent me here to see what can be done for you; some of your Bands get money, goods, and provisions by former Treaty, others get none because the Great Council at Washington did not think your lands worth purchasing. By the treaty you made with Gov. Cass, several years ago, you gave to your lands all the minerals; so the minerals belong no longer to you, and the white men are asking him permission to take the minerals from the land. But your Great Father wishes to pay you something for your lands and minerals before he will allow it. He knows you are needy and can be made comfortable with goods, provisions, and tobacco, some Farmers, Carpenters to aid in building your houses, and Blacksmiths to mend your guns, traps, &c., and something for schools to learn your children to read and write, and not grow up in ignorance. I hear you have been unpleased about your Farmers and Blacksmiths. If there is anything wrong I wish you would tell me, and I will write all your complaints to your Great Father, who is ever watchful over your welfare. I fear you do not esteem your teachers who come among you, and the schools which are among you, as you ought. Some of you seem to think you can learn as formerly, but do you not see that the Great Spirit is changing things all around you. Once the whole land was owned by you and other Indian Nations. Now the white men have almost the whole country, and they are as numerous as the Pigeons in the spring. You who have been in Washington know this; but the poor Indians are dying off with the use of whiskey, while others are sent off across the Mississippi to make room for the white men. Not because the Great Spirit loves the white men more than the Indians, but because the white men are wise and send their children to school and attend to instructions, so as to know more than you do. They become wise and rich while you are poor and ignorant, but if you send your children to school they may become wise like the white men; they will also learn to worship the Great Spirit like the whites, and enjoy the prosperity they enjoy. I hope, and he, that you will open your ears and hearts to receive this advice, and you will soon get great light. But said he, I am afraid of you, I see but few of you go to listen to the Missionaries, who are now preaching here every night; they are anxious that you should hear the word of the Great Spirit and learn to be happy and wise, and to have peace among yourselves.

The 1837 Treaty of St. Peters was mostly negotiated by Maajigaabaw or “La Trappe” of Leech Lake and other chiefs from outside the territory ceded by that treaty. The chiefs from the ceded lands were given relatively few opportunities to speak. This created animosity between the Lake Superior and Mississippi Bands.Your Great Father is very sorry to learn that there are divisions among his red children. You cannot be happy in this way. Your Great Father hopes you will live in peace together, and not do wrong to your white neighbors, so that no reports will be made against you, or pay demanded for damages done by you. These things when they occur displease him very much, and I myself am ashamed of such things when I hear them. Your Great Father is determined to put a stop to them, and he looks that the Chiefs and Braves will help him, so that all the wicked may be brought to justice; then you can hold up your heads, and your Great Father will be proud of you. Can I tell him that he can depend upon his Chippeway children acting in this way.

One other thing, your Great Father is grieved that you drink whiskey, for it makes you sick, poor, and miserable, and takes away your senses. He is determined to punish those men who bring whiskey among you, and of this I will talk more at another time.

Stuart would become irritated after the treaty when the Ojibwe argued they did not cede Isle Royale in 1842. This lead to further negotiations and an addendum in 1844. The Grand Portage Band, who lived closest to Isle Royale, was not party to the 1842 negotiations.When I was in New York about three moons ago I found 800 blankets which were due you last year, which by some mismanagement you did not get. Your Great Father was very angry about it, and wished me to bring them to you, and they will be given you at the payment. He is determined to see that you shall have justice done you, and to dismiss all improper agents. He despises all who would do you wrong. Now I propose to buy your lands from Fond du Lac, at the head of Lake Superior, down Lake Superior to Chocolate River near Grand Island, including all the Islands in the limits of the United States, in the Lake, making the boundary on Lake Superior about 250 miles in extent, and extending back into the country on Lake Superior about 100 miles. Mr. Stuart showed the Chiefs the boundary on the map, and said you must not suppose that your Great Father is very anxious to buy your lands, the principal object is the minerals, as the white people will not want to make homes upon them. Until the lands are wanted you will be permitted to live upon them as you now do. They may be wanted hereafter, and in this event your Great Father does not wish to leave you without a home. I propose that the Fond du Lac lands and the Sandy Lake tract (which embrace a tract 150 miles long by 100 miles deep) be left you for a home for all the bands, as only a small part of the Fond du Lac lands are to be included in the present purchase. Think well on the subject and counsel among yourselves, but allow no black birds to disturb you, your Great Father is now willing and can do you great good if you will, but if not you must take the consequences. To-morrow at the fire of the gun you can come to the Council ground and tell me whether the proposal I make in the name of your Great Father is agreeable to you; if so I will do what I can for you, you have known me to be your friend for many years. I would not do you wrong if I could, but desire to assist you if you allow me to do so. If you now refuse it will be long before you have another offer.

October 1st. At the sound of the Cannon the Council met, and when all were ready for business, Shingoop, the head Chief of the Fond du Lac band, with his 2d and 3d Chiefs, came forward and shook hands with the Commissioner and others associated with him, then spoke as follows:

Zhingob (Balsam), also known as Nindibens, signed the 1837, 1842, and 1854 treaties as chief or head chief of Fond du Lac. The Zhingob on earlier treaties is his father. See Ely, ed. Schenck, The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. ElyMy friend, we now know the purpose you came for and we don’t want to displease you. I am very glad there are so many Indians here to hear me. I wish to speak of the lands you want to buy of me. I don’t wish to displease the Traders. I don’t wish to displease the half-breeds; so I don’t wish to say at once, right off. I want to know what our Great Father will give us for them, then I will think and tell you what I think. You must not tell a lie, but tell us what our Great Father will give us for our lands. I want to ask you again, my Father. I want to see the writing, and who it is that gave our Great Father permission to take our minerals. I am well satisfied of what you said about Blacksmiths, Carpenters, Schools, Teachers, &c., as to what you said about whiskey, I cannot speak now. I do not know what the other Chiefs will say about it. I want to see the treaty and the name of the Chiefs who signed. The Chief answered that the Indians had been deceived, that they did not so understand it when they signed it.

Mr. Stuart replied that this was all talk for nothing, that the Government had a right to the minerals under former treaty, yet their Great Father wishes now to pay for the minerals and purchase their lands.

The Chief said he was satisfied. All shook hands again and the Chief retired.

The next Chief who came forward was the “Great Buffalo” Chief of the La Pointe band. Had heavy epaulettes on his shoulders and a hat trimmed with tinsel, with a heavy string of bear claws about his neck, and said:-

“Big Buffalo (Chippewa),” 1832-33 by Henry Inman, after J.O. Lewis (Smithsonian).

My father, I don’t speak for myself only, but for my Chiefs. What you said here yesterday when you called us your children, is what I speak about. I shall not say what the other Chief has said, that you have heard already.

He then made some remarks about the Missionaries who were laboring in their country and thought as yet, little had been done. About the Carpenters, he said, that he could not tell how it would work, as he had not tried it yet.

We have not decided yet about the Farmers, but we are pleased at your proposal about Blacksmiths. Can it be supposed that we can complete our deliberations in one night. We will think on the subject and decide as soon as we can.

The great Antonaugen Chief came next, observing the usual ceremony of shaking hands, and surrounded by his inferior Chiefs, said:-

The great Ontonagon Chief is almost certainly Okandikan (Buoy), depicted here in a reproduction of an 1848 pictograph carried to Washington and reproduced by Seth Eastman. Okandikan is depicted as his totem symbol, the eagle (largest, with wing extended in the center of the image).

My father and all the people listen and I call upon my Great Father in Heaven to bear witness to the rectitude of my intentions. It is now five years since we have listened to the Missionaries, yet I feel that we are but children as to our abilities. I will speak about the lands of our band, and wish to say what is just and honorable in relation to the subject. You said we are your children. We feel that we are still, most of us, in darkness, not able fully to comprehend all things on account of our ignorance. What you said about our becoming enlightened I am much pleased; you have thrown light on the subject into my mind, and I have found much delight and pleasure thereby. We now understand your proposition from our Great Father the President, and will now wait to hear what our Great Father will give us for our lands, then we will answer. This is for the Antannogens and Ance bands.

Mr. Stuart now said, that he came to treat with the whole Chippeway Nation and look upon them all as one Nation, and said

I am much pleased with those who have spoken; they are very fine orators; the only difficulty is, they do not seem to know whether they will sell their lands. If they have not made up their minds, we will put off the Council.

Lac du Flambeau Chief, “the Great Crow,” came forward with the strict Indian formalities but had but little to say, as he did not come expecting to have any part in the treaty, but wished to receive his payment and go home.

The 2d Chief of this band wished to speak. He was painted red with black spots on each cheek to set off his beauty, his forehead was painted blue, and when he came to speak, he said:-

What the last Chief has said is all I have to say. We will wait to hear what your proposals are and will answer at a proper time.

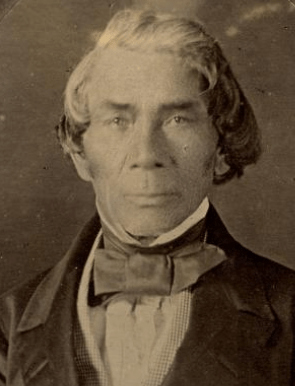

Next came forward “Noden,” or the “Great Wind,” Chief of the Mill Lac band, and said:-

Noodin (Wind) is mentioned here as representing the Mille Lacs Band, though his village was usually on Snake River of the St. Croix.

I have talked with my Great Father in Washington. It was a pity that I did not speak at the St. Peters treaty. My father, you said you had come to do justice. We do not wish to do injustice to our relations, the half-breeds, who are also our friends. I have a family and am in a hurry to get home, if my canoes get destroyed I shall have to go on foot. My father, I am hurry, I came for my payment. We have left our wives and children and they are impatient to have us return. We come a great distance and wish to do our business as soon as we can. I hope you will be as upright as our former agent. I am sorry not to see him seated with you. I fear it will not go as well as it would. I am hurry.

Mr Stuart now said that he considered them all one nation, and he wished to know whether they wished to sell their lands; until they gave this answer he could do nothing, and as it regards any thing further he could say nothing, and said they might now go away until Monday, at the firing of the Cannon they might come and tell him whether they would sell their country to their Great Father.

We intend giving the remainder of the proceedings of the treaty in our next.

Green Bay Republican:

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 1842, Page 2.

(Treaty with the Chippeways Concluded.)

Monday morning three guns were fired as a signal to open the Treaty. When all things were in readiness, Mr. Stuart said:

I am glad you have now had time for reflection, and I hope you are now ready like a band of brothers to answer the question which I have proposed. I want to see the Nation of one heart and of one mind.

Shingoop, Chief of the Fond du Lac band, came forward with full Indian ceremony, supported on each side by the inferior Chiefs. He addressed the Chippeway nation first, which was not fully interpreted; then he turned to the Commissioner and said:

in this Treaty which we are about to make, it is in my heart to say that I want our friends the traders, who have us in charge provided for. We want to provide also for our friends the half-breeds – we wish to state these preliminaries. Now we will talk of what you will give us for our country. There is a kind of justice to be done towards the traders and half-breeds. If you will do justice to us, we are ready to-morrow to sign the treaty and give up our lands. The 2d Chief of the band remarked, that he considered it the understanding that the half-breeds and traders were to be provided for.

The Great Buffalo, of La Pointe band, and his associate Chiefs came next, and the Buffalo said:

My Father, I want you to listen to what I say. You have heard what one Chief has said. I wish to say I am hurry on account of keeping so many men and women here away from their homes in this late season of the year, so I will say my answer is in the affirmative of your request; this is the mind of my Chiefs and braves and young men. I believe you are a correct man and have a heart to do justice, as you are sent here by our Great Father, the President. Father, our traders are so related to us that we cannot pass a winter without them. I want justice to be done them. I want you and our Great Father to assist us in doing them justice, likewise our half-breed children – the children of our daughters we wish provided for. It seems to me I can see your heart, and you are inclined to do so. We now come to the point for ourselves. We wish to know what you will give us for our country. Tell us, then we will advise with our friends. A part of the Antaunogens band are with me, the other part are turned Christians and gone with the Methodist band, (meaning the Ance band at Kewawanon) these are agreed in what I say.

The Bird, Chief of the Ance band, called Penasha, came forward in the usual form and said:

My Father, now listen to what I have to say. I agree with those who have spoken as far as our lands are concerned. What they say about our traders and half-breeds, I say the same. I speak for my band, they make use of my tongue to say what they would say and to express their minds. My Father, we listen to what you will offer for our country, then we will say what we have to say. We are ready to sell our country if your proposals are agreeable. All shook hands – equal dignity was maintained on each side – there was no inclination of the head or removing the hat – the Chiefs took their seats.

The White Crow next appeared to speak to the Great Father, and said:-

White Crow is apparently unaware that in the eyes of the United States, his lands, (Lac du Flambeau) were already sold five years earlier at St. Peters. Clearly, the notion of buying and selling land was not understood by him in the same way it was understood by Stuart.

Listen to what I say. I speak to the Great Father, to the Chiefs, Traders, and Half-breeds. You told us there was no deceit in what you say. You may think I am troublesome, but the way the treaty was made at St. Peters, we think was wrong. We want nothing of the kind again. We think you are a just man. You have listened to those Chiefs who live on Lake Superior. What I say is for another portion of country. It appears you are not anxious to buy the lands where I live, but you prefer the mineral country. I speak for the half-breeds, that they may be provided for: they have eaten out of the same dish with us: they are the children of our sisters and daughters. You may think there is something wrong in what I say. As to the traders, I am not the same mind with some. The old traders many years ago, charged us high and ought to pay us back, instead of bringing us in debt. I do not wish to provide for them; but of late years they have had looses and I wish those late debts to be paid. We do not consider that we sell our lands by saying we will sell them, so we consent to sell if your proposals are agreeable. We will listen and hear what they are.

Several others of the Chiefs spoke well on the subject, but the substance of all is contained in the above.

Hole-in-the-day, who is at once an orator and warrior, came forward; he had an Arkansas tooth pick in his hand which would weigh one or two pounds, and is evidently the greatest and most intelligent man in the nation, as fine a form of body, head and face, as perhaps could be found in any country.

Father, said he, I arise to speak. I have listened with pleasure to your proposal. I have come to tie the knot. I have come to finish this part of the treaty, and consent to sell our country if the offers of the President please us. Then addressing the Chiefs of the several bands he said, the knot is now tied, and so far the treaty is complete, not to be changed.

Zhaagobe (“Little” Six) signed as first chief from Snake River, and he is almost certainly the “Big Six” mentioned here. Several Ojibwe and Dakota chiefs from that region used that name (sometimes rendered in Dakota as Shakopee).

Big Six now addressed the whole Nation in a stream of eloquence which called down thunders of applause; he stands next to Hole-in-the-day in consequence and influence in the nation. His motions were graceful, his enunciation rather rapid for a fine speaker. He evidently possesses a good mind, though in person and form he is quite inferior to Hole-in-the-day. His speech was not interpreted, but was said to be in favor of selling the Chippeway country if the offer of the Government should meet their expectations, and that he took a most enlightened view of the happiness which the nation would enjoy if they would live in peace together and attend to good counsel.

Mr. Stuart now said,

I am very happy that the Chippewa nation are all of one mind. It is my great desire that they should continue to for it is the only way for them to be happy and wise. I was afraid our “White Crow” was going to fly away, but am happy to see him come back to the flock, so that you are all now like one man. Nothing can give me greater pleasure than to do all for you I can, as far as my instructions from your Great Father will allow me. I am sorry you had any cause to complain of the treaty at St. Peters. I don’t believe the Commissioner intended to do you wrong, but perhaps he did not know your wants and circumstances so as to suit. But in making this treaty we will try to reconcile all differences and make all right. I will now proceed to offer you all I can give you for your country at once. You must not expect me to alter it, I think you will be pleased with the offer. If some small things do not suit you, you can pass them over. The proposal I now make is better than the Government has given any other nation of Indians for their lands, when their situations are considered. Almost double the amount paid to the Mackinaw Indians for their good lands. I offer more than I at first intended as I find there are so many of you, and because I see you are so friendly to our Government, and on account of your kind feelings for the traders and half-breeds, and because you wish to comply with the wishes of your Great Father, and because I wish to unite you all together. At first I thought of making your annuities for only twenty years but I will make them twenty-five years. For twenty-five years I will offer you the following and some items for one year only.

$12,500 in specie each year for 25 years, $312,500

10,500 in goods ” ” ” ” ” 262,500

2,000 in provisions and tobacco, do. 50,000$625,000

This amount will be connected with the annuity paid to a part of the bands on the St. Peters treaty, and the whole amount of both treaties will be equally distributed to all the bands so as to make but one payment of the whole, so that you will be but one nation, like one happy family, and I hope there will be no bad heart to wish it otherwise. This is in a manner what you are to get for your lands, but your Great Father and the great Council at Washington are still willing to do more for you as I will now name, which you will consider as a kind of present to you, viz:

2 Blacksmiths, 25 years, $2000, $50,000

2 Farmers, ” ” 1200, 30,000

2 Carpenters, ” ” 1200, 30,000

For Schools, ” ” 2000, 50,000

For Plows, Glass, Nails, &c. for one year only, 5000

For Credits for one year only, 75,000

For Half-breeds ” ” ” 15,000$255,000

Total $880,000

With regards to the claims. I will not allow any claim previous to 1822; none which I deem unjust or improper. I will endeavor to do you justice, and if the $75,000 is not all required to pay your honest debts, the balance shall be paid to you; and if but a part of your debts are paid your Great Father requires a receipt in full, and I hope you will not get any more credits hereafter. I hope you have wisdom enough to see that this is a good offer. The white people do not want to settle on the lands now and perhaps never will, so you will enjoy your lands and annuities at the same time. My proposal is now before you.

The Fond du Lac Chief said, we will come to-morrow and give our answer.

October 4th, Mr. Stuart opened the Council.

Clement Hudon Beaulieu, was about thirty at this time and working his way up through the ranks of the American Fur Company at the beginning of what would be a long and lucrative career as an Ojibwe trader. His influence would have been very useful to Stuart as he was a close relative of Chief Gichi-Waabizheshi. He may have also been related to the Lac du Flambeau chiefs–though probably not a grandson of White Crow as some online sources suggest.

We have now met said he, under a clear sun, and I hope all darkness will be driven away. i hope there is not a half-breed whose heart is bad enough to prevent the treaty, no half-breed would prevent he treaty unless he is either bad at heart or a fool. But some people are so greedy that they are never satisfied. I am happy to see that there is one half-breed (meaning Mr. Clermont Bolio) who has heart enough to advise what is good; it is because he has a good heart, and is willing to work for his living and not sponge it out of the Indians.

We now heard the yells and war whoops of about one hundred warriors, ornamented and painted in a most fantastic manner, jumping and dancing, attended with the wild music usual in war excursions. They came on to the Council ground and arrested for a time the proceedings. These braves were opposed to the treaty, and had now come fully determined to stop the treaty and prevent the Chiefs from signing it. They were armed with spears, knives, bows and arrows, and had a feather flag flying over ten feet long. When they were brought to silence, Mr. Stuart addressed them appropriately and they soon became quiet, so that the business of the treaty proceeded. Several Chiefs spoke by way of protecting themselves from injustice, and then all set down and listened to the treaty, and Mr. Stuart said he hoped they would understand it so as to have no complaints to make afterwards.

The provisions of the treaty are the same as made in the proposals as to the amount and the manner of payment. The Indians are to live on the lands until they are wanted by the Government. They reserve a tract called the Fond du Lac and Sandy Lake country, and the lands purchased are those already named in the proposals. The payment on this treaty and that of the St. Peters treaty are to be united, and equal payments made to all the bands and families included in both treaties. This was done to unite the nation together. All will receive payments alike. The treaty was to be binding when signed by the President and the great Council at Washington. All the Chiefs signed the treaty, the name of Hole-in-the-day standing at the head of the list, and it is said to be the greatest price paid for Indian lands by the United States, their situation considered, though the minerals are said to be very valuable.

The Commissioner is said to have conducted the treaty in a very just, impartial and honorable manner, and the Indians expressed the kindest feelings towards him, and the greatest respect for all associated with him in negotiating the treaty and the best feelings towards their Agent now about leaving the country, and for the Agents of the American Fur Company and for the traders. The most of them expressed the warmest kind of feelings toward the Missionaries, who had come to their country to instruct them out of the word of the Great Spirit. The weather was very pleasant, and the scene presented was very interesting.

Lac du Flambeau Reservation: 1842 Boundaries

October 23, 2021

“We do not feel disposed to go away into a strange & unknown country, we desire to remain where our ancestors lay & where their remains are to be seen.“

By Leo

Poking through old archives, sometimes you find the best things where you wouldn’t expect to. The National Archives have been slowly digitizing its Bureau of Indian Affairs microfilms, and for several months, I have been slogging through the thousands of images from the La Pointe Agency. For a change of pace, a few days ago, I checked out the documents on the Sault Ste. Marie Agency films and got my hands on a good one.

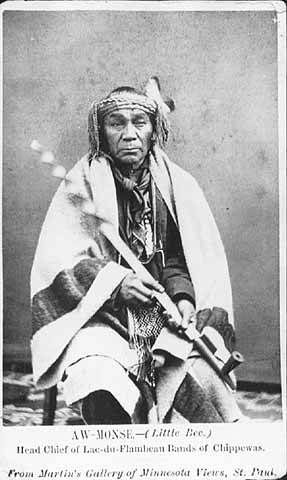

In September of 1847, Aamoons (Little Bee) and some headmen of what had been White Crow’s (Waabishkaagaagi) Lac du Flambeau were facing a serious dilemma. They were on their way home from the annuity payment at La Pointe where the main topic of conversation would certainly have been controversy surrounding the recent treaty at Fond du Lac. Several chiefs refused to sign, and the American Fur Company’ Northern Outfit opposed it due to a controversial provision that would have established a second Ojibwe sub agency on the Mississippi River. They saw this provision as a scheme by Missisippi traders to effect the removal west of all bands east of the Mississippi. Aamoons, himself, did not initially sign the document, but his mark can be found on the back of an envelope sent from La Pointe to Washington.

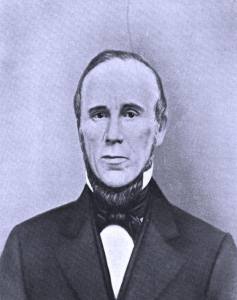

Our old friend George Johnston was returning to his Sault Ste. Marie home from the annuity payments when the Lac du Flambeau men summoned him to the Turtle Portage, near today’s Mercer, Wisconsin. They presented him a map and made speeches suggesting removal would be in direct violation of promises made at the Treaty of La Pointe (1842).

Johnston did not have a position with the American Government at this time, and his trading interests in western Lake Superior were modest. However, he was well known in the country. His grandfather, Waabojiig (White Fisher), was a legendary war chief at Chequamegon, and his parents formed a powerful fur trade couple at the turn of the 19th century. In the 1820s, George served as the first Indian Office sub-agent at La Pointe under his brother-in-law Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. During this time, he developed connections with Ojibwe leaders throughout the Lake Superior country, many of whom he was related to by blood or marriage.

By 1847, Schoolcraft had remarried and left for Washington after the death of his first wife (George’s sister Jane). However, the two men continued to correspond and supply direct intelligence to each other regarding Ojibwe politics. Local Indian Agents attempted to control all communication moving to and from Washington, so in Johnston they likely saw a chance to subvert this system and press their case directly.

The document that emerged from this 174 year old meeting is notable for a few reasons. It further bolsters the argument that the Ojibwe did not view their land cessions in the 1837 and 1842 treaties as requiring them to leave their villages in the east. That point that has been argued for years, but here we have a document where the chiefs speak of specific promises. It also reinforces the notion that the various political factions among the Lake Superior chiefs were coalescing around a policy of promoting reservations as an alternative to removal. This seems obvious now, but reservations were a novel concept in the 1840s, and certainly the United States ceding land back to Indian nations east of the Mississippi would have been unheard of. Knowing this was part of the discussion in 1847 makes the Sandy Lake Tragedy, three years later, all the more tragic. The chiefs had the solution all along, and had the Government just listened to the Ojibwe, hundreds of lives would have been spared.

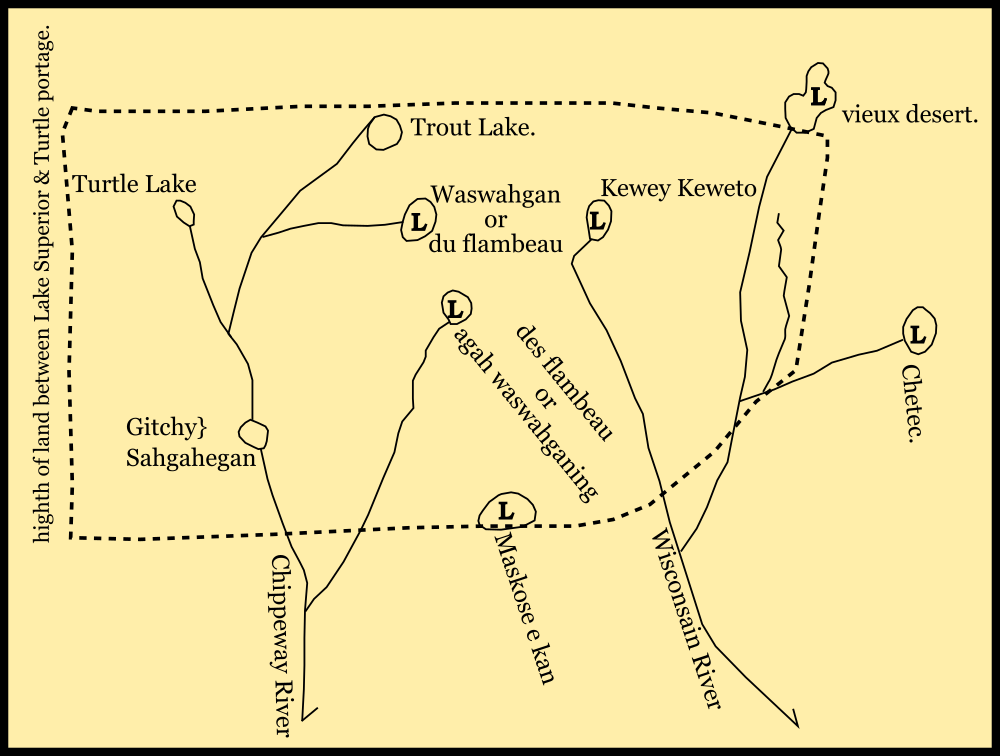

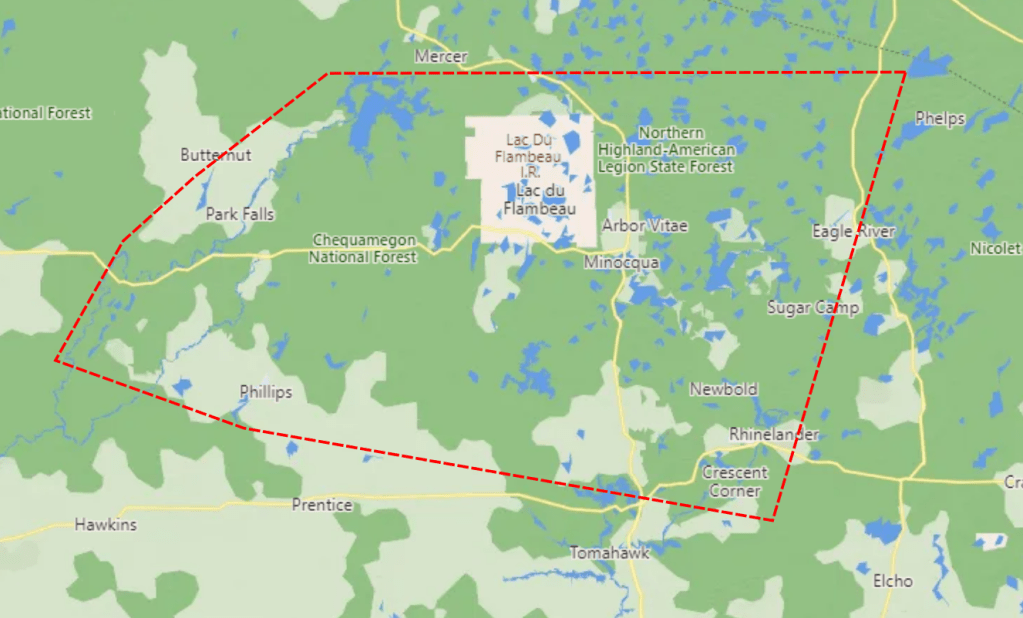

Finally, the document, especially the map, should be of interest to the modern Lac du Flambeau Band as it appears its reservation should be much larger, encompassing the historical villages at Turtle Portage and Trout Lake as well as Aamoons’ village at Lac du Flambeau proper. The borders also seem to approach, but not include the villages at Vieux Desert and Pelican Lake, which will be interesting to the modern Sokaogon and Lac Vieux Desert Bands.

Saut Ste. Marie

Augt 28th 1848.

Dear sir,

On reaching the turtle portage during the past fall; I was addressed by the Indians inhabiting, the Lac du Flambeau country and they presented me with a map of that region, also a petition addressed to you which I will herein insert, they were under an impression that you could do much in their behalf. The object of delineating a map is to show to the department, the tract of country they reserved for themselves, at the treaty of 1842, concluded by Robert Stuart at Lapointe during that period, and which now appears to be included in that treaty, without any reserve to the Indians of that region, and who expressly stated through me that they were willing to sell their mineral lands, but would retain the tract of country delineated on the map; This forms an important grievance in that region. I designed to have forwarded to you during the past winter their map & petition, but having mislaid it, I did not find it till this day, in an accidental manner, and I now feel that I am bound in duty to forward it to you.

The petition of the Chiefs Ahmonce, Padwaywayashe, Oshkanzhenemais & Say Jeanemay.

My Father (addressing Mr. Schoolcraft.)

Padwaywayashe rose and said, It is not I that will now speak on this occasion, it is these three old men before you, they are related to our ancestors, that man (pointing to Say Jeanemay will be their spokesman,

Sayjeanemay rose and said,

My Father, (addressing himself to Mr. Schoolcraft.)

Padwaywayahshe who has just now ceased speaking is the son of the late Kakabishin an ancient Chief who was lost many years ago in lower Wisconsain, and the white people have not as yet found him, and his Father was one of the first who received the Americans when they landed on the Island of Mackinac. Kishkeman and Kahkahbeshine are the two first chiefs that shook hands with the Americans, The Indian agent then told them that he had arrived and had come to be a friend to them, they who were living in the high mountains, and he saw that they were poor and he was come to rekindle their fire, and the American Indian Agent then gave Kish Keman a large flag and a large silver medal, and said to him, you will never meet with a bad day, the sky will always be bright before you.

My Father.

Our old chief the white crow died last dall, he went to the treaty held at St. Peters, and reached that point when the treaty was almost concluded, and he heard very little of it, and it was not him who sold our lands, it was an Indian living beyond the pillager band of Indians. We feel much grieved at heart, we are now living without a head, and had we reached St. Peters in time, the person who sold our lands would not have been permitted to do so, we should have made provision for ourselves and for our children, We do not now see the bright sky you spoke of to us, we see the return of the bad day I was in the habit of seeing before you came to renew my fire, and now it is again almost extinguished.

My Father;

We feel very much grieved; had my chief been present I should not have parted with my lands, and we find that the commissioner who treated with us, (meaning Mr. R. Stuart) has taken advantage of our ignorance, and bought our lands at his own price, and we did not sell the tract delineated on our map.

My Father;

We do not feel disposed to go away into a strange & unknown country, we desire to remain where our ancestors lay & where their remains are to be seen. We now shake hands with you hope that you will answer us soon.

Turtle portage 11th Sep; 1847.

In presence of}

Geo. Johnston.

Ahmonce his X mark

Padwaywayahshe his X mark

Oshkanzhenemay his X mark

Sayjeaneamy his X mark

To,

Henry R. Schoolcraft Esq.

Washington

N.B. All the country lying within the dotted lines embraces the country, the Chief Monsobodoe & others reserved at the Lapointe treaty and which now is embraced in the Treaty articles, and could not be misunderstood by Mr. Stuart and as I have already remarked forms an important grievance. All of which is respectfully submitted by

Respectfully

Your obt Servant

Geo. Johnston.

Henry R. Schoolcraft Esq.

Washington.

Respectfully referred from my files to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs

H.R.S

14th Feb 1849

Ahmonce (Aamoons), is found in many documents from the 1850s and 60s as the successor chief to the band once guided by his father Waabishkaagaagi (White Crow), uncle Moozobodo (Moose Muzzle), and grandfather Giishkiman (Sharpened Stone). The latter two are spelled Monsobodoe and Kishkeman in this document. Gaakaabishiinh (Kahkabeshine) “Screech Owl,” is probably the “old La Chouette” recorded in Malhiot’s Lac du Flambeau journal in the winter of 1804-05.

“The Americans when they landed on the Island of Mackinac” refers to the surrender of the British garrison at the end of the War of 1812, which is often referenced as the start of American assertions of sovereignty over the Ojibwe country. Despite Sayjeanemay’s lofty friendship rhetoric, it should be noted that many Ojibwe warriors fought with the British against the United States and political relations with the British crown and Ojibwe bands on the American side would continue for the next forty years.

The speaker who dominated the 1837 negotiations, and earned the scorn of the Lake Superior Bands, was Maajigaabaw or “La Trappe.” He, Flat Mouth, and Hole-in-the-Day, chiefs of the Mississippi and Pillager Bands in what is now Minnesota, were more inclined to sell the Wisconsin and Chippewa River basins than the bands who called that land home. This created a major rift between the Lake Superior and Mississippi Ojibwe.

Pa-dua-wa-aush (Padwaywayahshe) is listed under Aamoons’ band in the 1850 annuity roll. Say Jeanemay appears to be an English phonetic rendering of the Ojibwe pronunciation of the French name St. Germaine. A man named “St. Germaine” with no first name given appears in the same roll in Aamoons’ band. The St. Germaines were a mix-blood family with a long history in the Flambeau Country, but this man appears to be too old to be a child of Leon St. Germaine and Margaret Cadotte. From the text it appears this St. Germaine’s family affiliated with Ojibwe culture, in contrast to the Johnstons, another mix-blood family, who affiliated much more strongly with their father’s Anglo-Irish elite background. So far, I have not been able to find another mention of Oshkanzhenemay.

Moozobodo was not present at the Treaty of La Pointe (1842) as he died in 1831. Johnston may be confusing him with his brother Waabishkaagaagi

The timing of Schoolcraft’s submission of this document to the Indian Department is curious. In February 1849, a delegation of chiefs, mostly from villages near Lac du Flambeau was in Washington D.C. to petition President Polk for reservations. Schoolcraft worked to undermine this delegation. Had he instead promoted the cause of reservations over removal, one wonders if he could have intervened to prevent the Sandy Lake debacle.

Map of Lac du Flambeau Reservation as understood by Ojibwe at Treaty of La Pointe 1842. Apparently drawn from memory 11 September 1847 by Lac du Flambeau chiefs, copied and presumably labelled by George Johnston. Microfilm slide made available online by National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/164363909 Image 340.

Alleged reservation boundaries agreed to in 1842 roughly superimposed over modern map. The Treaty of La Pointe (1854) called for three townships for the Lac du Flambeau Band–the white square on this map showing the modern reservation. Had the 1842 boundaries held, the reservation would have been much larger and included several popular resort communities.

Wheeler Papers: Bad River’s Missing Creek

October 3, 2018

By Amorin Mello

This is one of several posts on Chequamegon History featuring the original U.S. General Land Office surveys of the La Pointe (Bad River) Indian Reservation. An earlier post, An Old Indian Settler, features a contentious memoir from Joseph Stoddard contemplating his experiences as a young man working on the U.S. General Land Office’s crew surveying the original boundaries of the Reservation. In his memoir from 1937, Stoddard asserted the following testimony:

Bad River Headman

Joseph Stoddard

“As a Christian, I dislike to say that the field representatives of the United States were grafters and crooks, but the stories related about unfulfilled treaties, stipulations entirely ignored, and many other things that the Indians have just cause to complain about, seem to bear out my impressions in this respect.”

In the winter of 1854 a general survey was made of the Bad River Indian Reservation.

[…]

It did not take very long to run the original boundary line of the reservation. There was a crew of surveyors working on the west side, within the limits of the present city of Ashland, and we were on the east side. The point of beginning was at a creek called by the Indians Ke-che-se-be-we-she (large creek), which is located east of Grave Yard Creek. The figure of a human being was carved on a large cedar tree, which was allowed to stand as one of the corner posts of the original boundary lines of the Bad River Reservation.

After the boundary line was established, the head surveyor hastened to Washington, stating that they needed the minutes describing the boundary for insertion in the treaty of 1854.

We kept on working. We next took up the township lines, then the section lines, and lastly the quarter lines. It took several years to complete the survey. As I grew older in age and experience, I learned to read a little, and when I ready the printed treaty, I learned to my surprise and chagrin that the description given in that treaty was different from the minutes submitted as the original survey. The Indians today contend that the treaty description of the boundary is not in accord with the description of the boundary lines established by our crew, and this has always been a bone of contention between the Bad River Band and the government of the United States.

The mouth of Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek a.k.a. the townsite location of Ironton is featured in our Barber Papers and Penokee Survey Incidents. Today this location is known as the mouth of Oronto Creek at Saxon Harbor in Iron County, Wisconsin. The townsite of Ironton was formed at Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek by a group of land speculators in the years immediately following the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe. Some of these speculators include the Barber Brothers, who were U.S. Deputy Surveyors surveying the Reservation on behalf of the U.S. General Land Office. It appears that this was a conflict of interest and violation of federal trust responsibility to the La Pointe Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

This post attempts to correlate historical evidence to Stoddard’s memoir about the mouth of Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek being a boundary corner of the Bad River Indian Reservation. The following is a reproduction of a petition draft from Reverend Leondard Wheeler’s papers, who often kept copies of important documents that he was involved with. Wheeler is a reliable source of evidence as he established a mission at Odanah in the 1840s and was intimately familiar with the Treaty and how the Reservation was to be surveyed accordingly.

Wheeler drafted this petition six years after the Treaty occurred; this petition was drafted more than seventy-five years earlier than when Stoddard’s memoir of the same important matter was recorded. The length of time between Wheeler’s petition draft and Stoddard’s memoir demonstrates how long this was (and continued to be) a matter of great contemplation and consternation for the Tribe. Without further ado, we present Wheeler’s draft petition below:

A petition draft selected from the

Wheeler Family Papers:

Folder 16 of Box 3; Treaty of 1854, 1854-1861.

To Hon. C W Thompson

Genl Supt of Indian affair, St Paul, Min-

and Hon L E Webb,

Indian Agent for the Chippewas of Lake Superior

March 30th, 1855 map from the U.S. General Land Office of lands to be withheld from sale for the La Pointe (Bad River) Reservation from the National Archives Microfilm Publications; Microcopy No. 27; Roll 16; Volume 16. The northeast corner of the Reservation along Lake Superior is accurately located at the mouth of Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek (not labeled) on this map.

The undersigned persons connected with the Odanah Mission, upon the Bad River Reservation, and also a portion of those Chiefs who were present and signed the Treaty of Sept 30th, AD 1854, would most respectfully call your attention to a few Statements affecting the interests of the Indians within the limits of the Lake Superior Agency, with a view to soliciting from you such action as will speedily see one to the several Indian Bands named, all of the benefits guaranteed to them by treaty stipulation.

Under the Treaty concluded at La Pointe Sept 30th, 1854 the United States set apart a tract of Land as a Reservation “for the La Pointe Band and such other Indians as may see fit to settle with them” bounded as follows.

a.k.a.

Ke-che-se-be-we-she

“Ke-che” (Gichi) refers to big, or large.

“se-be” (ziibi) refers to a river.

“we-she” (wishe) refers to rivulets.

Source: Gidakiiminaan Atlas by the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission

“Beginning on the South shore of Lake Superior a few miles west of Montreal River at the mouth of a creek called by the Indians Ke-she-se-be-we-she, running thence South &c.”

Detail of the Bad River Reservation from GLIFWC’s Gidakiiminaan Atlas. This map clearly shows that the northeast boundary of Bad River Reservation is not located at the true location of Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek in accordance with the 1854 Treaty. Red highlights added for emphasis of discrepancies.

Your petioners would represent that at the time of the wording of this particular portion of the Treaty, the commissioner on the part of the United States inquired the number of miles between the mouth of the Montreal River and the mouth of the creek referred to, in reply to which, the Indians said “they had no knowledge of distance by miles” and therefore the commissioner assumed the language of “a few miles west of Montreal River” as discriptive of the creek in mind. This however, upon actual examination of the ground, does to the Band the greatest injustice, as the mouth of the creek to which the Indians referred at the time is even less than one mile west of the mouth of the Montreal.*

*This creek at the time was refered to as having “Deep water inside the Bar” sufficient for Boats which is definitive of the creek still claimed as the starting point, and is not descriptive of the most westerly creek.

But White men, whose interests are adverse to those of the Indians now demand that the Reservation boundary commence at an insignificant and at times scarcely visible creek some considerable distance west of the one referred to in the Treaty, which would lessen the aggregate of the Reservation from 3 to 4000 acres.

Your petioners, have for years, desired and solicited a settlement of the matter, both for the good of the Indians and of the Whites, but from lack of interest the administrations in power have paid no attention to our appeals, as is also true of other matters to which we now call your attention.

1861 resurvey of Township 47 North of Range 1 West by Elisha S. Norris for the General Land Office relocating Bad River Reservation’s northeast boundary. Ke-che-se-be-we-she Creek was relocated to what is now Graveyard Creek instead of its true location at the Barber Brother’s Ironton townsite location. Red highlights added for emphasis of discrepancies.

As many heads of families now wish to select (within the portion of Town 47 North of Range 1 West belonging to the Reservation the 80 acre tract assigned to them) we desire that the Eastern Boundary of the Reservation be immediately established so that the subdivisions may be made and and land selected.

Your petioners would further [represent?] that under the 3d Section of the 2nd article of the Treaty referred to the Lac De Flabeau, and Lac Court Orelles Bands are entitled to Reservations each equal to 3 Townships, (See article 3d of Treaty. These Reservations have never been run out, none have any subdivisions been made.) which also were to be subdivided into 80 acre Tracts.

Article 4th promises to furnish each of the Reservations with a Blacksmith and assistant with the usual amount of Stock, where as the Lac De Flambeau Band have never yet had a Blacksmith, though they have repeatedly asked for one.

Wisconsin State Representative

and co-founder of Ashland

Asaph Whittlesey

As the matters have referred to one of vital importance to these several Bands of Indians, we earnestly hope that you will give your influence towards securing to them, all of the benefits named in the Treaty and as the subject named will demand labor entirely outside of the ordinary duties of an Indian Agent, and as it will be important for some one to visit the Reservations Inland, so as to be able to report intelligently upon the actual State of Things, we respectfully suggest that Mr Asaph Whittlesey be specially commissioned (provided you approve of the plan and you regard him as a suitable person to act) to attend to the taking of the necessary depositions and to present these claims, with the necessary maps and Statistics, before the Commissioner of Indian Affairs at Washington, the expense of which must of necessity, be met by the Indian Department.

Mr Whittlesey was present at the making of the Treaty to which we refer, and is well acquainted with the wants of the Indians and with what they of right can claim, and in him we have full confidence.

In addition to the points herein named should you favor this commission, we would ask him to attend to other matters affecting the Indians, upon which we will be glad to confer with you at a proper time.

The undersigned L H Wheeler and Henry Blatchford have no hesitency in saying that the representations here made are full in accordance with their understanding of the Treaty, at the time it was drawn up, they being then present and the latter being one of the Interpreters at the time employed by the General Government.

Most Respectfully Yours

Dated Odanah Wis July 1861

Names of those connected with the Odanah Mission

[None identified on this draft petition]

Names of Chiefs who were signers to the Treaty of Sept 30th 1854

[None identified on this draft petition]

Although this draft was not signed by Wheeler or Blatchford, or by the tribal leadership that they appear to be assisting, Chequamegon History believes it is possible that a signed original copy of this petition may still be found somewhere in national archives if it still exists.

Among The Otchipwees: III

July 20, 2016

By Amorin Mello

… continued from Among The Otchipwees: II

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 4 February 1885

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 335-342.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

III.

The Northern tribes have nothing deserving the name of historical records. Their hieroglyphics or pictorial writings on trees, bark, rocks and sheltered banks of clay relate to personal or transient events. Such representations by symbols are very numerous but do not attain to a system.

Their history prior to their contact with the white man has been transmitted verbally from generation to generation with more accuracy than a civilized people would do. Story-telling constitutes their literature. In their lodges they are anything but a silent people. When their villages are approached unawares, the noise of voices is much the same as in the camps of parties on pic-nic excursions. As a voyageur the pure blood is seldom a success, and one of the objections to him is a disposition to set around the camp-fire and relate his tales of war or of the hunt, late into the night. This he does with great spirit, “suiting the action to the word” with a varied intonation and with excellent powers of description. Such tales have come down orally from old to young many generations, but are more mystical than historical. The faculty is cultivated in the wigwam during long winter nights, where the same story is repeated by the patriarchs to impress it on the memory of the coming generation. With the wild man memory is sharp, and therefore tradition has in some cases a semblance to history. In substance, however, their stories lack dates, the subjects are frivolous or merely romantic, and the narrator is generally given to embellishment. He sees spirits everywhere, the reality of which is accepted by the child, who listens with wonder to a well-told tale, in which he not only believes, but is preparing to be a professional story-teller himself.

Indian picture-writings and inscriptions, in their hieroglyphics, are seen everywhere on trees, rocks and pieces of bark, blankets and flat pieces of wood. Above Odanah, on Bad River, is a vertical bank of clay, shielded from storms by a dense group of evergreens. On this smooth surface are the records of many generations, over and across each other, regardless of the rights of previous parties. Like most of their writings, they relate to trifling events of the present, such as the route which is being traveled; the game killed; or the results of a fight. To each message the totem or dodem of the writer is attached, by which he is at once recognized. But there are records of some consequence, though not strictly historical.

Charles Whittlesey also reproduced Okandikan’s autobiography in Western Reserve Historical Society Tract 41.

Before a young man can be considered a warrior, he must undergo an ordeal of exposure and starvation. He retires to a mountain, a swamp, or a rock, and there remains day and night without food, fire or blankets, as long as his constitution is able to endure the exposure. Three or four days is not unusual, but a strong Indian, destined to be a great warrior, should fast at least a week. One of the figures on this clay bank is a tree with nine branches and a hand pointing upward. This represents the vision of an Indian known to one of my voyagers, which he saw during his seclusion. He had fasted nine days, which naturally gave him an insight of the future, and constituted his motto, or chart of life. In tract No. 41 (1877), of the Western Reserve Historical Society, I have represented some of the effigies in this group; and also the personal history of Kundickan, a Chippewa, whom I saw in 1845, at Ontonagon. This record was made by himself with a knife, on a flat piece of wood, and is in the form of an autobiography. In hundreds of places in the United States such inscriptions are seen, of the meaning of which very little is known. Schoolcraft reproduced several of them from widely separated localities, such as the Dighton Boulder, Rhode Island; a rock on Kelley’s Island, Lake Erie, and from pieces of birch bark, conveying messages or memoranda to aid an orator in his speeches.

~ New Sources of Indian History, 1850-1891: The Ghost Dance and the Prairie Sioux, A Miscellany by Stanley Vestal, 2015, page 269.

The “Indian rock” in the Susquehanna River, near Columbia, Pennsylvania; the God Rock, on the Allegheny, near Brady’s Bend; inscriptions on the Ohio River Rocks, near Wellsville, Ohio, and near the mouth of the Guyandotte, have a common style, but the particular characters are not the same. Three miles west of Barnsville, in Belmont County, Ohio, is a remarkable group of sculptured figures, principally of human feet of various dimensions and uncouth proportions. Sitting Bull gave a history of his exploits on sheets of paper, which he explained to Dr. Kimball, a surgeon in the army, published in fascimile in Harper’s Weekly, July 1876. Such hieroglyphics have been found on rocky faces in Arizona, and on boulders in Georgia.

Pointe De Froid is the northwestern extremity of La Pointe on Madeline Island. Map detail from 1852 PLSS survey.

~ Report of a geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota: and incidentally of a portion of Nebraska Territory, by David Dale Owen, 1852, page 420.

~ Geology of Wisconsin: Paleontology by R. P. Whitfield, 1880, page 58.

While pandemonium was let loose at La Pointe towards the close of the payment we made a bivouac on the beach, between the dock and the mission house. The voyageurs were all at the great finale which constitutes the paradise of a Chippewa. One of my local assistants was playing the part of a detective on the watch for whisky dealers. We had seen one of them on the head waters of Brunscilus River, who came through the woods up the Chippewa River. Beyond the village of La Pointe, on a sandy promontory called Pointe au Froid, abbreviated to Pointe au Fret or Cold Point, were about twenty-five lodges, and probably one hundred and fifty Indians excited by liquor. For this, diluted with more than half water, they paid a dollar for each pint, and the measure was none too large – neither pressed down nor running over. Their savage yells rose on the quiet moon-lit atmosphere like a thousand demons. A very little weak whisky is sufficient to work wonders in the stomach of a backwoods Indian, to whom it is a comparative stranger. About midnight the detective perceived our traveler from the Chippewa River quietly approaching the dock, to which he tied his canoe and went among the lodges. To the stern there were several kegs of fire-water attached, but weighted down below the surface of the water. It required but a few minutes to haul them in and stave the heads of all of them. Before morning there appeared to be more than a thousand savage throats giving full play to their powerful lungs. Two of them were staggering along the beach toward where I lay, with one man by my side. he said we had better be quiet, which, undoubtedly, was good advice. They were nearly naked, locked arm in arm, their long hair spread out in every direction, and as they swayed to and fro between the water line and the bushes, no imagination could paint a more complete representation of the demon. There was a yell to every step – apparently a bacchanalian song. They were within two yards before they saw us, and by one leap cleared everything, as though they were as much surprised as we were. The song, or howl, did not cease. It was kept up until they turned away from the beach into the mission road, and went on howling over the hill toward the old fort. It required three days for half-breed and full-blood alike to recover from the general debauch sufficiently to resume the oar and pack. As we were about to return to the Penoka Mountains, a Chippewa buck, with a new calico shirt and a clean blanket, wished to know if the Chemokoman would take him to the south shore. He would work a paddle or an oar. Before reaching the head of the Chegoimegon Bay there was a storm of rain. He pulled off his shirt, folded it and sat down upon it, to keep it dry. The falling rain on his bare back he did not notice.

Portrait of Stephen Bonga

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

We had made the grand portage of nine miles from the foot of the cataract of the St. Louis, above Fond du Lac, and encamped on the river where the trail came to it below the knife portage. In the evening Stephen Bungo, a brother of Charles Bungo, the half-breed negro and Chippewa, came into our tent. He said he had a message from Naugaunup, second chief of the Fond du Lac band, whose home as at Ash-ke-bwau-ka, on the river above. His chief wished to know by what authority we came through the country without consulting him. After much diplomatic parley Stephen was given some pequashigon and went to his bivouac.

Joseph Granville Norwood

~ Wikipedia.org

Portrait of Naagaanab

~ Minnesota Historical Society

The next morning he intimated that we must call at Naugaunup’s lodge on the way up, where probably permission might be had, by paying a reasonable sum, to proceed. We found him in a neat wigwam with two wives, on a pleasant rise of the river bluff, clear of timber, where there had been a village of the same name. His countenance was a pleasant one, very closely resembling that of Governor Corwin, of Ohio, but his features were smaller and also his stature. Dr. Norwood informed him that we had orders from the Great Father to go up the St. Louis to its source, thence to the waters running the other way to the Canada line. Nothing but force would prevent us from doing this, and if he was displeased he should make a complaint to the Indian agent at La Pointe, and he would forward it to Washington. We heard no more of the invasion of his territory, and he proceeded to do what very few Chippewas will do, offered to show us valuable minerals. In the stream was a pinnacle of black sale, about sixty feet high. Naugaunup soon appeared from behind it, near the top, in a position that appeared to be inaccessible, a very picturesque object pointing triumphantly to some veins of white quartz, which are very common in metamorphic slate.

Those who have heard him, say that he was a fine orator, having influence over his band, a respectable Indian, and a good negotiator. If he imagined there was value in those seams of quartz it is quite remarkable and contrary to universal practice among Chippewas that he should show them to white men. They claim that all minerals belong to the tribe. An Indian who received a price for showing them, and did not give every one his share, would be in danger of his life. They had also a superstitious dread of some great evil if they disclosed anything of the kind. Some times they promise to do so, but when they arrive at the spot, with some verdant white man, expecting to become suddenly rich, the Great Spirit or the Bad Manitou has carried it away. I have known more than one such instance, where persons have been sustained by hopeful expectation after many days of weary travel into the depths of the forest. The editor of the Ontonagon Miner gives one of the instances in his experience:

“Many years ago when Iron River was one of the fur stations, of John Jacob Astor and the American Fur Company, the Indians were known to have silver in its native state in considerable quantities.”

Men are now living who have seen them with chunks of the size of a man’s fist, but no one ever succeeded in inducing them to tell or show where the hidden treasure lay. A mortal dread clung to them, that if they showed white men a deposit of mineral the Great Manitou would punish them with death.

Several years since a half-breed brought in very fine specimens of vein rock, carrying considerable quantities of native silver. His report was that his wife had found it on the South Range, where they were trapping. To test his story he was sent back for more. In a few days he returned bringing with him quite a chunk from which was obtained eleven and one-half ounces of native silver. He returned home, went among the Flambeaux Indians and was killed. His wife refused to listen to any proposals or temptation from friend or foe to show the location of this vein, clinging with religious tenacity to the superstitious fears of her tribe.

When the British had a fort on St. Joseph’s Island in the St. Mary’s River, in the War of 1812, an Indian brought in a rich piece of copper pyrites. The usual mode of getting on good terms with him, by means of whisky, failed to get from him the location of the mineral. Goods were offered him; first a bundle, then a pile, afterwards a canoe-load, and finally enough to load a Mackinaw boat. No promise to disclose the place, no description or hint could be extorted. It was probably a specimen from the veins on the Bruce or Wellington mining property, only about twenty miles distant on the Canadian shore.

Detail of John Beargrease the Younger from stereograph “Lake Superior winter mail line” by B. F. Childs, circa 1870s-1880s.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

Crossing over the portage from the St. Louis River to Vermillion River, one of the voyageurs heard the report of a distant shot. They had expected to meet Bear’s Grease, with his large family, and fired a gun as a signal to them. The ashes of their fire were still warm. After much shouting and firing, it was evident that we should have no Indian society at that time. That evening, around an ample camp fire, we heard the history of the old patriarch. His former wives had borne him twenty-four children; more boys than girls. Our half-breed guide had often been importuned to take one of the girls. The old father recommended her as a good worker, and if she did not work he must whip her. Even a moderate beating always brought her to a sense of her duties. All he expected was a blanket and a gun as an offset. He would give a great feast on the occasion of the nuptials. Over the summit to Vermillion, through Vermillion Lake, passing down the outlet among many cataracts to the Crane Lake portage, there were encamped a few families, most of them too drunk to stand alone. There were two traders, from the Canada side, with plenty of rum. We wanted a guide through the intricacies of Rainy Lake. A very good-looking savage presented himself with a very unsteady gait, his countenance expressing the maudlin good nature of Tam O’Shanter as he mounted Meg. Withal, he appeared to be honest. “Yes, I know that way, but, you see, I’m drunk; can’t you wait till to-morrow.” A young squaw who apparently had not imbibed fire-water, had succeeded in acquiring a pewter ring. Her dress was a blanket of rabbit skins, made of strips woven like a rag carpet. It was bound around her waist with a girdle of deer’s hide, answering the purpose of stroud and blanket. No city belle could exhibit a ring of diamonds more conspicuously and with more self-satisfaction than this young squaw did her ring of pewter.

As we were all silently sitting in the canoes, dripping with rain, a sudden halloo announced the approach of living men. It was no other than Wau-nun-nee, the chief of the Grand Fourche bands, who was hunting for ducks among the rice. More delicious morsels never gladdened the palate than these plump, fat, rice-fed ducks. Old Wau-nun-nee is a gentleman among Indian chiefs. His band had never consented to sell their land, and consequently had no annuities. He even refused to receive a present from the Government as one of the head men of the tribe, preferring to remain wholly independent. We soon came to his village on Ash-ab-ash-kaw Lake. No band of Indians in our travels appeared as comfortable or behaved as well as this. Their country is well supplied with rice and tolerably good hunting ground. The American fur dealers (I mean the licensed ones) do not sell liquor to the Indians, and use their influence to aid Government in keeping it from them. Wau-nun-nee’s baliwick was seldom disturbed by drunken brawls. His Indians had more pleasant countenances than any we had seen, with less of the wild and haggard look than the annuity Indians. It was seldom they left their grounds, for they seldom suffered from hunger. They were comfortably clothed, made no importunities for kokoosh or pequashigon, and in gratifying their savage curiosity about our equipments they were respectful and pleasant. In his lodge the chief had teacups and saucers, with tea and sugar for his white guests, which he pressed us to enjoy. But we had no time for ceremonials, and had tea and sugar of our own. Our men recognized numerous acquaintances among the women, and as we encamped near a second village at Round Lake they came to make a draft on our provision chest. We here laid in a supply of wild rice in exchange for flour. Among this band we saw bows and arrows used to kill game. They have so little trade with the whites, and are so remote from the depots of Indian goods, that powder and lead are scarce, and guns also. For ducks and geese the bow and arrow is about as effectual as powder and shot. In truth, the community of which Wau-nun-nee was the patriarch came nearer to the pictures of Indians which poets are fond of drawing than any we saw. The squaws were more neatly clad, and their hair more often combed and braided and tied with a piece of ribbon or red flannel, with which their pappooses delighted to sport. There were among them fewer of those distinguished smoke-dried, sore-eyed creatures who present themselves at other villages.

By my estimate the channel, as we followed it to the head of the Round Lake branch, is two hundred and two mile in length, and the rise of the stream one hundred and eight feet. The portage to a stream leading into the Mississippi is one mile.

At Round Lake we engaged two young Indians to help over the portage in Jack’s place. Both of them were decided dandies, and one, who did not overtake us till late the next morning, gave an excuse that he had spent the night in courting an Indian damsel. This business is managed with them a little differently than with us. They deal largely in charms, which the medicine men furnish. This fellow had some pieces of mica, which he pulverized, and was managing to cause his inamorata to swallow. If this was effected his cause was sure to succeed. He had also some ochery, iron ore and an herb to mix with the mica. Another charm, and one very effectual, is composed of a hair from the damsel’s head placed between two wooden images. Our Lothario had prepared himself externally so as to produce a most killing effect. His hair was adorned with broad yellow ribbons, and also soaked in grease. On his cheeks were some broad jet black stripes that pointed, on both sides, toward his mouth; in his ears and nose, some beads four inches long. For a pouch and medicine bag he had the skin of a swan suspended from his girdle by the neck. His blanket was clean, and his leggings wrought with great care, so that he exhibited a most striking collection of colors.

At Round Lake we overtook the Cass Lake band on their return from the rice lakes. This meeting produced a great clatter of tongues between our men and the squaws, who came waddling down a slippery bank where they were encamped. There was a marked difference between these people and those at Ash-ab-ash-kaw. They were more ragged, more greasy, and more intrusive.

CHARLES WHITTLSEY.

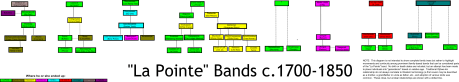

La Pointe Bands Part 1

April 19, 2015

By Leo Filipczak

On March 8th, I posted a map of Ojibwe people mentioned in the trade journals of Perrault, Curot, Nelson, and Malhoit as a starting point to an exploration of this area at the dawn of the 19th Century. Later the map was updated to include the journal of John Sayer.

In these journals, a number of themes emerge, some of which challenge conventional wisdom about the history of the La Pointe Band. For one, there is very little mention of a La Pointe Band at all. The traders discuss La Pointe as the location of Michel Cadotte’s trading depot, and as a central location on the lakeshore, but there is no mention of a large Ojibwe village there. In fact, the journals suggest that the St. Croix and Chippewa River basins as the place where the bulk of the Lake Superior Ojibwe could be found at this time.

In the post, I repeated an argument that the term “Band” in these journals is less identifiable with a particular geographical location than it is with a particular chief or extended family. Therefore, it makes more sense to speak of “Giishkiman’s Band,” than of the “Lac du Flambeau Band,” because Giishkiman (Sharpened Stone) was not the only chief who had a village near Lac du Flambeau and Giishkiman’s Band appears at various locations in the Chippewa and St. Croix country in that era.

In later treaties and United State’s Government relations, the Ojibwe came to be described more often by village names (La Pointe, St. Croix, Fond du Lac, Lac du Flambeau, Lac Courte Oreilles, Ontonagon, etc.), even though these oversimplified traditional political divisions. However, these more recent designations are the divisions that exist today and drive historical scholarship.

So what does this mean for the La Pointe Band, the political antecedent of the modern-day Bad River and Red Cliff Bands? This is a complicated question, but I’ve come across some little-known documents that may shed new light on the meaning and chronology of the “La Pointe Band.” In a series of posts, I will work through these documents.

This series is not meant to be an exhaustive look at the Ojibwe at Chequamegon. The goal here is much narrower, and if it can be condensed into one line of inquiry, it is this:

Fourteen men signed the Treaty of 1854 as chiefs and headmen of the La Pointe Band:

Ke-che-waish-ke, or the Buffalo, 1st chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Chay-che-que-oh, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

A-daw-we-ge-zhick, or Each Side of the sky, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

O-ske-naw-way, or the Youth, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Maw-caw-day-pe-nay-se, or the Black Bird, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Naw-waw-naw-quot, headman, his x mark. [L. S.]

Ke-wain-zeence, headman, his x mark. [L. S.]

Waw-baw-ne-me-ke, or the White Thunder, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Pay-baw-me-say, or the Soarer, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Naw-waw-ge-waw-nose, or the Little Current, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Maw-caw-day-waw-quot, or the Black Cloud, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Me-she-naw-way, or the Disciple, 2d chief, his x mark. [L. S.]

Key-me-waw-naw-um, headman, his x mark. [L. S.]

She-gog headman, his x mark. [L. S.]

If we consider a “band” as a unit of kinship rather than a unit of physical geography, how many bands do those fourteen names represent? For each of those bands (representing core families at Red Cliff and Bad River), what is the specific relationship to the Ojibwe villages at Chequamegon in the centuries before the treaty?

The Fitch-Wheeler Letter

Chequamegon History spends a disproportionately large amount of time on Ojibwe annuity payments. These payments, which spanned from the late 1830s to the mid-1870s were large gatherings, which produced colorful stories (dozens from the 1855 payment alone), but also highlighted the tragedy of colonialism. This is particularly true of the attempted removal of the payments to Sandy Lake in 1850-1851. Other than the Sandy Lake years, the payments took place at La Pointe until 1855 and afterward at Odanah.

The 1857 payment does not necessarily stand out from the others the way the 1855 one does, but for the purposes of our investigation in this post, one part of it does. In July of that year, the new Indian Agent at Detroit, A.W. Fitch, wrote to Odanah missionary Leonard Wheeler for aid in the payment:

Office Michn Indn Agency

Detroit July 8th 1857

Sir,

I have fixed upon Friday August 21st for the distribution of annuities to the Chippewa Indians of Lake Supr. at Bad River for the present year. A schedule of the Bands which are to be paid there is appended.

I will thank you to apprise the LaPointe Indians of the time of payment, so that they should may be there on the day. It is not necessary that they should be there before the day and I prefer that they should not.

And as there was, according to my information a partial failure in the notification of the Lake De Flambeau and Lake Court Oreille Indians last year, I take the liberty to entrust their notification this year to you and would recommend that you dispatch two trusty Messengers at once, to their settlements to notify them to be at Bad River by the 21st of August and to urge them forward with all due diligence.

It is not necessary for any of these Indians to come but the Chiefs, their headmen and one representative for each family. The women and children need not come. Two Bands of these Indians, that is Negicks & Megeesee’s you will notice are to be notified by the same Messengers to be at L’Anse on the 7th of September that they may receive their pay there instead of Bad River.

I presume that Messengers can be obtained at your place for a Dollar a day each & perhaps less and found and you will please be particular about giving them their instructions and be sure that they understand them. Perhaps you had better write them down, as it is all important that there should be no misunderstanding nor failure in the matter and furthermore you will charge the Messenger to return to Bad River immediately, so that you may know from them, what they have done.

It is my purpose to land the Goods at the mo. of Bad River somewhere about the 1st of Aug. (about which I will write you again or some one at your place) and proceed at once to my Grand Portage and Fond Du Lac payments & then return to Bad River.

Schedule of the Bands of Chipps. of Lake Supr. to be notified of the payment at Bad River, Wisn to be made Friday August 21st for the year 1854.

____________________________

La Pointe Bands.

__________

Maw kaw-day pe nay se [Blackbird]

Chay, che, qui, oh, [Little Buffalo/Plover]

Maw kaw-day waw quot [Black Cloud]

Waw be ne me ke [White Thunder]

Me she naw way [Disciple]

Aw, naw, quot [Cloud]

Naw waw ge won. [Little Current]

Key me waw naw um [Canoes in the Rain] {This Chief lives some distance away}

A, daw, we ge zhick [Each Side of the Sky]

Vincent Roy Sen. {head ½ Breeds.}

Lakes De Flambeau & Court Oreille Bands.

__________

Keynishteno [Cree]

Awmose [Little Bee]

Oskawbaywis [Messenger]

Keynozhance [Little Pike]

Iyawbanse [Little Buck]

Oshawwawskogezhick [Blue Sky]

Keychepenayse [Big Bird]

Naynayonggaybe [Dressing Bird]

Awkeywainze [Old Man]

Keychewawbeshayshe [Big Marten]

Aishquaygonaybe–[End Wing Feather]