Diplomacy in the Time of Cholera: why there was no Ojibwe delegation to President Taylor in the winter of 1849-50

December 15, 2024

By Leo

At Chequamegon History, we deal mostly in the micro. By limiting our scope to a particular time and place, we are all about the narrow picture. Don’t come here for big universal ideas. The more specific and obscure a story, the more likely it is to appear on this website.

Madeline Island and the Chequamegon region are perfect for the specific and obscure. In the 1840s, most Americans would have thought of La Pointe as remote frontier wilderness, beyond the reach of worldwide events. Most of us still look at our history this way.

We are wrong. No man is an island, and Madeline Island–though literally an island–was no island.

This week, I was reminded of this fact while doing research for a project that has nothing to do with Chequamegon History. While scrolling through the death records of the Greek-Catholic church of my ancestral village in Poland, I noticed something strange. The causes of deaths are usually a mishmash of medieval sounding ailments, all written in Latin, or if the priest isn’t feeling creative or curious, the death is just listed as ordinaria.

In the summer of 1849, however, there was a noticeable uptick in death rate. It seemed my 19th-century cousins, from age 7 to 70, were all dying of the same thing:

Cause of death in right column. Akta stanu cywilnego Parafii Greckokatolickiej w Olchowcach (1840-1879). Księga zgonów dla miejscowości Olchowce. https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/en/jednostka/-/jednostka/22431255

Cholera is a word people my age first learned on our Apple IIs back in elementary school:

At Herbster School in 1990, we pronounced it “Cho-lee-ra.” It was weird the first time someone said “Caller-uh.” You can play online at https://www.visitoregon.com/the-oregon-trail-game-online/

It is no coincidence. If you note the date of leaving Matt’s General Store in Independence Missouri, Oregon Trail takes place in 1848.

Diseases thrive in times of war, upheaval, famine, and migration, and 1848 and 1849 certainly had plenty of all of those. A third year of potato blight and oppressive British policies plunged the Irish poor deeper into squalor and starvation. The millions who were able to, left Ireland. Meanwhile, the British conquest of the Punjab and the “Springtime of Nations” democratic revolutions across central Europe meant army and refugee camps (notorious vectors of disease) popped up across the Eurasian continent.

North America had seen war as well. The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (1848) ended the Mexican-American War and delivered half of Mexico over to Manifest Destiny. The discovery of gold in California, part of this cession, brought thousands of Chinese workers to the West Coast, while millions of Irish and Germans arrived on the East Coast. Some of those would also find their way west along the aforementioned Oregon Trail.

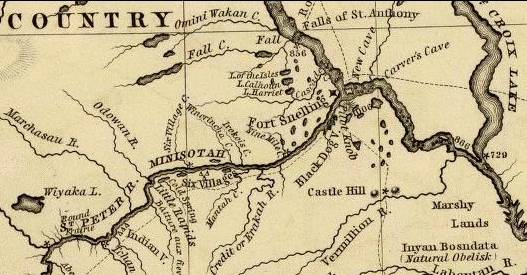

Closer to home, these German immigrants meant statehood for Wisconsin and the shifting of Wisconsin’s Indian administration west to Minnesota Territory. Eyeing profits, Minnesota and Mississippi River interests were increasingly calling for the removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe bands from Wisconsin and Michigan. This caused great alarm and uncertainty at La Pointe.

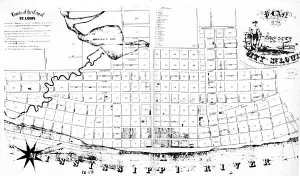

All of these seemingly disparate events of 1848 and 1849 are, in fact, related. One of the most obvious manifestations was that displaced people from all these places impacted by war, poverty, and displacement carried cholera. The disease arrived in the United States multiple times, but the worst outbreak came up Mississippi from New Orleans in the summer of 1849. It ravaged St. Louis, then the Great Lakes, and reached Sault Ste, Marie and Lake Superior by August.

Longtime Chequamegon History readers will know my obsession with the Ojibwe delegation that left La Pointe in October 1848 and visited Washington D.C. in February 1849. It is a fascinating story of a group of chiefs who brought petitions (some pictographic) laying out their arguments against removal to President James K. Polk and Congress. The chiefs were well-received, but ultimately the substance of their petitions was not acted upon. They arrived after the 1848 elections. Polk and the members of Congress were lame ducks. General Zachary Taylor had been elected president, though he wasn’t inaugurated until the day after the delegation left Washington.

If you’ve read through our DOCUMENTS RELATED TO THE OJIBWE DELEGATION AND PETITIONS TO PRESIDENT POLK AND CONGRESS 1848-1849, you’ll know that both Polk and the Ojibwe delegation’s translator and alleged ringleader, the colorful Jean-Baptiste Martell of Sault Ste. Marie, died of cholera that summer.

So, in this post, we’re going to evaluate three new documents, just added to the collection, and look at how the cholera epidemic partially led to the disastrous removal of 1850, commonly known as the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

The first document is from just after the delegation’s arrival in Washington. It describes the meeting with Polk in great detail, lays out the Ojibwe grievances, and importantly, records Polk’s reaction. I have not been able to find the name of the correspondent, but this article is easily the best-reported of all the many, many newspaper accounts of the 1848-49 delegation–most of which use patronizing racist language and focus on the more trivial, “fish out of water” element of Lake Superior chiefs in the capital city.

New York Daily Tribune, 6 February 1849, Page 1

The Indians of the North-West–Their Wrongs–Chiefs in Washington

Correspondence of The Tribune

WASHINGTON, 3d Feb 1849.

Yesterday (Friday) the Chiefs representing the Chippewa Tribe of Indians located on the borders of Lake Superior and drawing their pay at La Pointe, representing 16 bands, which comprise about 9,000 Indians, after remaining here for the last ten days, were presented to the President.– The Secretary of War and Commissioner of Indian Affairs were also present. One of the Chiefs who appeared to be the eldest, first addressed the President, for a period of twenty minutes. The address was interpreted by John B. Martell, a half-breed, who was born and has always continued among them. He appears a shrewd, sensible man, and interprets with much fluency. This Chief was followed by two others in addresses occupying the same length of time. They all addressed the President as “Our Great Father,” and spoke with much energy, dignity and fluency, preserving throughout a respectful manner and evincing an earnest sincerity of purpose, that bespoke their mission to be one of no ordinary character. They represented their grievances under which their tribes were laboring: the trials and privations they had undergone to reach here, and the separation from their families, with much emotion and in truly touching and eloquent terms.

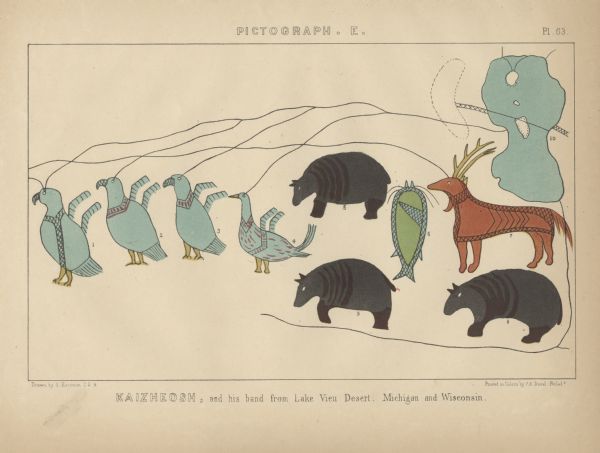

The oldest chief was Gezhiiyaash (his pictographic petition above) or “Swift Sailor” from Lac Vieux Desert. The two other chiefs were likely Oshkaabewis “Messenger” from Wisconsin River, and Naagaanab “Foremost Sitter” from Fond du Lac.

They represented that their annuities under their Treaty of La Pointe, made about the year 1843, were payable in the month of July in each year and not later, because by that time the planting season would be over; beside, it would be the best time and the least dangerous to pass the Great Lake and return to their homes in time to gather wild rice, on which they mainly depended during the hard winters. The first payment was made later than the time agreed upon. The agent, upon being notified, promised to comply with the terms of the Treaty, but every year since the payments have been made later, and that of last year did not take place until about the middle of October, in consequence of which they have been subjected to much suffering.– They assemble at the place for payment designated in the treaty. It is then the traders take advantage of them–being three hundred miles from home, without money, and without provisions; and when their money is received it must all be paid for their subsistence during the long delay they have been subjected to; and sickness frequently breaks out among them from being obliged to use salt provisions, which they are not accustomed to. By leaving their homes at any other time than in the month of July they neglect their harvesting–rice and potato crops, and if they neglect those they must starve to death; therefore it would be better for them to lose their annuities altogether. And without their blankets, procured at the Pointe, they are liable to freeze to death when passing the stormy lake; and the tradespeople influence the Agent to send for them a month before the payment is made, and when they arrive the Agent accepts orders from them for provisions which they are obliged to purchase at a great price–one dollar for 15 lbs of flour, and in proportion for other articles. They have assembled frequently in regard to these things, and can only conclude that their complaints have never reached their “Great Father,” and they have now come to see him in person, and take him by the hand.

In regard to the Half-Breeds at La Pointe, who draw pay with them, they say: That in the Treaty concluded between Governor Dodge and the Chippewas at St. Peters, provision was made for the half-breeds to draw their share all in one payment, and it was paid them accordingly, $258.50 each, which was a mere gift on the part of the tribe; a payment which they had no right to, but was given them as a present. Induced by some subsequent representations by the half-breeds, they were taken into their pay list, and the consequence has been that almost all the half breeds, as well as the French who are married to Indian women, are in the employ of, or dependent upon one of the principal trading houses, (Dr. Bourop’s) at La Pointe, with whom their goods and provisions are stored; and that they are thus enabled to select and appropriate to themselves the choice portion of all the goods designed for them–in many cases not leaving them a blanket to start with upon their journey of two or three hundred miles distant to their homes. After many other details, to which we will make reference in future articles, they urged that owing to the faithlessness of the half-breeds to them, and to the Government, that they be stricken from the pay list.

One half the goods furnished are of no use to them. The articles they most need are guns, kettles, blankets and a greater supply of provisions, &c.

They are under heavy expense, and no money to pay their board. They have undertaken this long journey for the benefit of their whole people, and at their earnest solicitations. They have been absent from their families nearly one year. It has cost them $1,400 to get here. Half of that sum has been raised from exhibitions. The other half has been borrowed from kind people on the route they have traveled. They wish to repay the money advanced them and to procure money to return home with. They want clothes and things to take to their families, and ask an appropriation of $6,000 on their annuity money.

They have before made a communication to the President, to be laid before the present Congress, for the acquisition of lands and the naturalization of their bands–propositions which they urged with great force.

All the Chiefs represented to the President that their interpreter, Mr. Martel, was living in very comfortable circumstances at home, and was induced to accompany them by the urgent solicitations of all their people who confided in his integrity and looked upon him as their friend.

The paternalistic ritual kinship (“Great Father”) language used here by James K. Polk, can be off-putting to the modern reader. However, it had a long tradition in Ojibwe “fur trade theater” rhetoric. Gezhiiyaash was no meek schoolboy, as evidenced by his words in this document (White House)

Their supplicating–though forcible, intelligent, and pathetic appeal, to be permitted to live upon the spot of their nativity, where the morning and noon of their days had been past, and the night time of their existence has reached them, was, too, and irresistible appeal to the justice, generosity and magnanimity of that boasted “civilization” that pleads mercy to the conquered, and was calculated to leave an impress upon every honest heart who claims to be a “freeman.”

The President, in answer to the several addresses, requested the interpreter to state to them that their Great Father was happy to have met with them; and as they had made allusion to written documents which they placed in his hands, as containing an expression of their views and wishes, he would carefully read them and communicate his answer to the Secretary of War and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, assuring them of kindly feelings on the part of the Government, and terminating with some expressions very like a schoolmaster’s enjoinder upon his scholars that if they behaved themselves they might expect good treatment in future.

The fact that they met Polk was not new information, but we hadn’t been previously aware of just how long the meeting went. It is important to note the president’s use of “kindly feelings” and “behaved themselves.” Those phrases would come up frequently in subsequent years.

One could argue that Polk was a lame duck, and would be dead of cholera within a few months, so his words didn’t mean much. One could argue the problem was that the Ojibwe didn’t understand that in the American political system–that the incoming Whig administration might not feel bound by the words and “kindly feelings” of the outgoing Democratic administration.

However, the next document shows that the chiefs did feel the need to cover their bases and stuck around Washington long enough meet the next president. To us, at least, this was new information:

National Era v. III. No. 14, pg. 56 April 5, 1849

For the National Era

THE CHIPPEWA CHIEFS AND GENERAL TAYLOR

On the third day after the arrival of General Taylor at Washington, the Indian chiefs requested me to seek an interview for them, as they were about to leave for their homes, on Lake Superior, and greatly desired to see the new President before their departure.

It was accordingly arranged by the General to see them the next morning at 9 o’clock, before the usual reception hour.

Fitted out in their very best, with many items of finery which their taste for the imposing had added to their wardrobe, the delegation and their interpreter accompanied me to the reception room, and were cordially taken by the hand by the plain but benevolent-looking old General. One of the chiefs arose, and addressed the President elect nearly as follows:

“Father! We are glad to see you, and we are pleased to see you so well after your long journey.

“Father! We are the representatives of about twenty thousand of your red children, and are just about leaving for our homes, far off on Lake Superior, and we are very much gratified, that, before our departure, we have the opportunity of shaking hands with you.

“Father! You have conquered your country’s enemies in war; may you subdue the enemies of your Administration while you are President of the United States and govern this great country, like the great father, Washington, before you, with wisdom and in peace.

“Father! This our visit through the country and to the cities of your white children, and the wonderful things that we have seen, impress us with awe, and cause us to think that the white man is the favored of the Great Spirit.

“Father! In the midst of the great blessings with which you and your white children are favored of the Great Spirit, we ask of you, while you are in power, not to forget your less fortunate red children. They are now few, and scattered, and poor. You can help them.

“Father! Although a successful warrior, we have heard of your humanity! And now that we see you face to face, we are satisfied that you have a heart to feel for your poor red children.

“Father Farewell”

The tall, manly-looking chief having finished and shaken hands, General Taylor asked him to be seated, and, rising himself, replied nearly as follows”

“My Red Children: I am very happy to have this interview with you. What you have said I have listened to with interest. It is the more appreciated by me, as I am no stranger to your people. I resided for a length of time on your borders, and have been witness to your privations, and am acquainted with many of your wants.

“Peace must be established and maintained between yourselves and the neighboring tribes of the red men, and you need in the next place the means of subsistence.

“My Red Children: I thank you for your kind wishes for me personally, and as President of the United States.

“While I am in office, I shall use my influence to keep you at peace with the Sioux, between whom and the Chippewas there has always been a most deadly hostility, fatal to the prosperity of both nations. I shall also recommend that you be provided with the means of raising corn and the other necessaries of life.

“My Red Children: I hope that you have met with success in your present visit, and that you may return to your homes without an accident by the way; and I bid you say to your red brethren that I cordially wish them health and prosperity. Farewell.”

This interesting interview closed with a general shaking of hands and during the addresses, it is creditable to the parties to say, that the feelings were reached. Tears glistened in the eyes of the Indians and General Taylor evinced sufficient emotion, during the address of the chief, to show that he possesses a heart that may be touched. The old veteran was heard to remark, as the delegation left the room, “What fine looking men they are!”

Major Martell, the half-breed interpreter, acquitted himself handsomely throughout. The Indians came away declaring that “General Taylor talked very good.”

The General’s family and suite, evidently not prepared for the visit; were not dressed to receive company at so early an hour; nevertheless, they soon came in, en dishabille, and looked on with interest.

P.

One of the lingering questions I’ve had about the 1848-49 Delegation has been whether or not the Ojibwe leadership viewed it as a success. This document shows that the answer was unequivocally yes. It also shows why the chiefs felt so blindsided and disbelieving in the spring of 1850 when the government agents at La Pointe told them that Taylor had ordered them to remove. They didn’t have to go back to 1842 for the Government’s promises. They had heard them only a year earlier from both the president and the president-elect!

It also explains why during and after the removal, the chiefs number-one priority was sending another delegation. One would eventually go in 1852, led by Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. This would help secure the reservations sought by the first delegation, but that was only after two failed removal attempts and hundreds of deaths.

If the cholera epidemic had not come, Chief Buffalo and other prominent chiefs, would have likely gone back to Taylor in the winter of 1849-50. They may have been able to secure new treaty negotiations, reservations on the ceded territory, or at the very least have been more prepared for the upcoming removal:

George Johnston to Henry Schoolcraft, 5 October 1849, MS Papers of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft: General Correspondence, 1806-1864, BOX 51.

Saut Ste Maries

Oct 5th 1849

My Dear sir,

Your favor of Sep. 14th, I have just now received and will lose no time in answering. Since I wrote to you on the subject of an intended delegation of Chippewa Chiefs desiring to visit the seat of Govt., I visited Lapointe and remained there during the payment, and I had an opportunity of seeing & talking with the chiefs. They held a council with their agent Dr. Livermore and expressed their desire to visit Washington this season, and they laid the matter before him with open frankness, and Dr. Livermore answered them in the same strain, advising them at the same time, to relinquish their intended visit this year, as it would be dangerous for them, to travel in the midst of sickness which was so prevalent & so widely spread in the land, and that if they should still feel desirous to go on the following year that he would then permit them to do so, and that he would have no objections, this appearing so reasonable to the chiefs, that they assented to it.

I will write to the chiefs and express to them the subject of your letter, and direct them to address Mr. Babcock at Detroit.

You will herein find enclosed copy of Mr. Ballander’s letter to me, a gentleman of the Hon. Hudson’s Bay Co. & Chief factor at Fort Garry in the Red river region, it is very kind & his sympathy, devotes a feeling heart.– Mr. Mitchell of Green Bay to whom I have written in the early part of this summer, to make enquiries relative to certain reports of Tanner’s existence among the sioux, he has not as yet returned an answer to may communication and I feel the neglect with some degree of asperity which I cannot control.

Very Truly yours

Geo. Johnston

Henry R. Schoolcraft Esq.

Washington

It is hard to say how differently history may have turned out if a second delegation had been able to go with George Johnston. There is a good chance it would have been a lot more successful. Johnston was much more of an insider than Martell–who had had a lot of difficulty convincing the American authorities of his credentials. One of those who stood in Martell’s way was Henry Schoolcraft. Schoolcraft, was regarded by the American establishment as the foremost authority on Ojibwe affairs and was Johnston’s brother-in-law.

It may not have worked. The inertia of United States Indian Policy was still with removal. Any attempt to reverse Manifest Destiny and convince the government to cede land back to Indian nations east of the Mississippi was going to be an uphill battle. The Minnesota trade interests were strong.

Also, Schoolcraft was a Democrat, so he would have had less influence with the Whig Taylor–though agreements on Western issues sometimes crossed party lines. However, one can imagine George Johnston sitting around a table in Washington with his “Uncle” Buffalo, his brother-in-law Schoolcraft, and the U.S. President, working out the contours of a new treaty avoiding the removal entirely. Because of the cholera, however, we’ll never know.

For more on how the fallout from the Mexican War impacted Ojibwe removal, see Slavery, Debt Default, and the Sandy Lake Tragedy

For more on the 1848-49 Delegation, see: this post, this post, and this post

American Fur Company: 1834 Reinvention of La Pointe

October 4, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

The below image from the Wisconsin Historical Society is a storymap showing La Pointe in 1834 as abstract squiggles on an oversized Madeline Island surrounded by random other Apostle Islands, Bayfield Peninsula, Houghton Point, Chequamegon Bay, Long Island, Bad River, Saxon Harbor, and Montreal River.

“Map of La Pointe”

“L M Warren”

“~ 1834 ~”

Wisconsin Historical Society

citing an original map at the New York Historical Society

My original (ongoing) goal for publishing this post is to find an image of the original 1834 map by Lyman Marcus Warren at the New York Historical Society to explore what all of his squiggles at La Pointe represented in 1834. Instead of immediately achieving my original goal, this post has become the first of a series exploring letters in the American Fur Company Papers by/to/about Warren at La Pointe.

New York Historical Society

American Fur Company Papers: 1831-1849

America’s First Business Monopoly

#16,582

Map of Lapointe

by L M Warren

~ 1834 ~

New York Historical Society

scanned as Gale Document Number GALE|SC5110110218

#36

Lapointe Lake Superior

September 20th ’34

Ramsey Crooks Esqr

Dear Sir

Starting in 1816, the American Fur Company (AFC) operated a trading post by the “Old Fort” of La Pointe near older trading posts built by the French in 1693 and the British in 1793.

In 1834, John Jacob Astor sold his legendary AFC to Ramsay Crooks and other trading partners, who in turn decided to relocate the AFC’s base of operations at Mackinac Island to Madeline Island, where our cartographer Lyman Marcus Warren was employed as the AFC’s trader at La Pointe.

Instead of improving any of the older trading posts on Madeline Island, Warren decided to move La Pointe to the “New Fort” of 1834 to build new infrastructure for growing business demands.

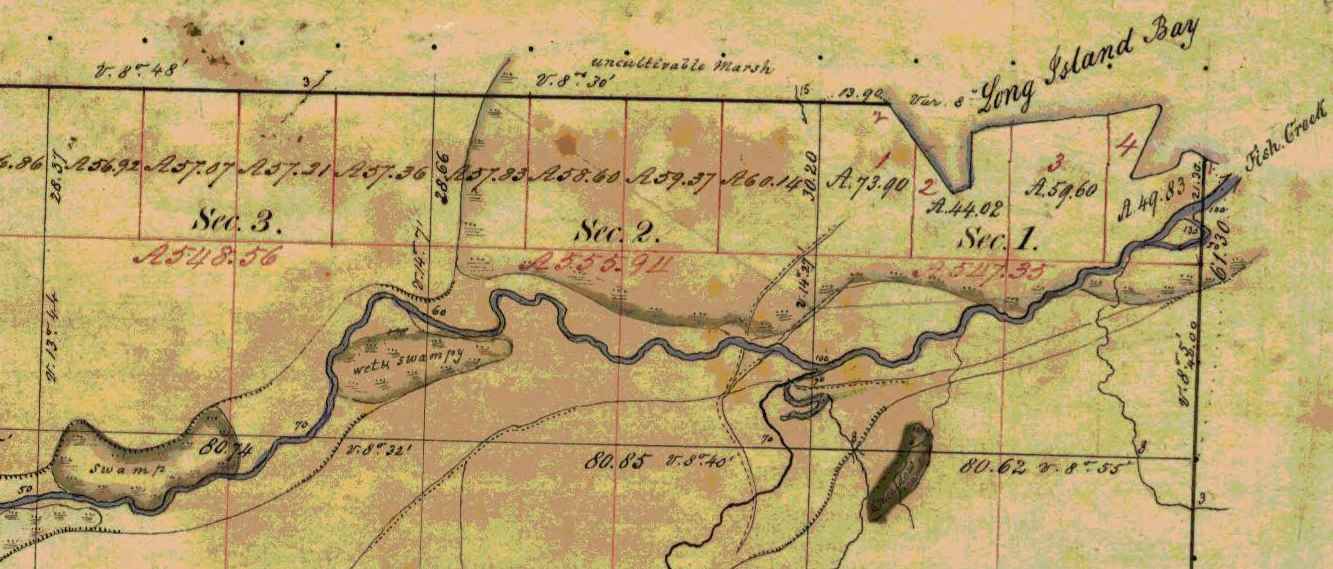

GLO PLSS 1852 survey detail of the “Am Fur Co Old Works” near Old Fort.

on My Way In as Mr Warren was was detained So Long at Mackinac I did not Wait for him at this Place as time was of So Much Consequence to me to Get my People Into the County that I Proceeded Immediately to Fond Du Lac with the Intention with the Intention of Returning to this Place When I Had Sent the Outfit off but When I Got There I Had News from the Interior Which Required me to Go In and Settle the Business there; the [appearance?] In the Interior for [????] is tolerable. Good Provision there is [none?] Whatever I [have?] Seen the [Country?] [So?] Destitute. The Indians at [Fort?] [?????] Disposed to give me Some trouble when they found they have to Get no Debts and buy their amunition and tobacco and not Get it For Nothing as usual but at Length quieted down [?????] and have all gone off to their Haunts as usual.

I Received your Instructions contained in your Circular and will be very Particular In Following them. The outfits were all off when I Received them but the men’s acts and the Invoices of the Goods Had all been Settled according to your Wishes and Every Care Will be taken not to allow the men to get In Debt the Clerks Have Strict orders on the Subject and it is made known to them that they will be Held for any of the Debts the men may Incur.

I Enclose to you the Bonds Signed and all the Funds we Received from Mr Johnston Excepting those Which Had been given to the Clerks and I could not Get them Back In time to Send them on at Present.

Mr Warren And myself Have Committed on What is to be done at this Place and I am certain all that Can be done Will be done by him. I leave here tomorrow For the Interior of Fond Du Lac Where I must be as Soon as possible.

I have written to Mr Schoolcraft as he Inquested me. Mr Brewster’s men would not Give up their [??????] and [???] [????] is [??] [?????] [????] [????] [to?] [???????] [?????] [to?] [persuade?] [more?] People for Keeping [his?] [property?] [Back?] [and] [then?] [???] by some [???] ought to be sent out of the Country [??] they are [under?] [the?] [???] [?] and [Have?] [no?] [Right?] to be [????] [????] they are trouble [????] [???] [their?] [tongues?].

GLO PLSS 1852 survey detail of the AFC’s new “La Point” (New Fort) and the ABCFM’s “Mission” (Middleport).

The Site Selected Here For the Buildings by Mr Warren is the Best there is the Harbour is good and I believe the work will go on well.

as For the Fishing we Will make Every Inquiry on the Subject and I Have no Doubt on My Mind of Fairly present that it will be more valuable than the Fur trade.

In the Month of January I will Write you Every particular How our affairs stand from St Peters. Bailly Still Continues to Give our Indians Credits and they Bring Liquor from that Place which they Say they Get from Him.

Please let Me know as Early as possible with Regard to the Price of Furs as it will Help me In the trade. the Clerks all appear anxious to do their Duty this year as the wind is now Falling and I am In Haste I Will Write you Every particular of our Business In January.

Wishing that God may Long Prosper you and your family.

In health and happiness.

I remain most truly,

and respectfully

yours $$

William A. Aitken

#42

Lake Superior

LaPointe Oct 16 1834

Ramsey Crooks Esqr

Agent American Fur Co

Honoured Sir

Your letter dated Mackinac Sept [??] reached me by Mr Chapman’s boat today.-

I will endeavour to answer it in such a manner as will give you my full and unreserved opinion on the different subjects mentioned in it.

I feel sorry to see friend Holiday health so poor, and am glad that you have provided him a comfortable place at the Sault. As you remark it is a fortunate circumstance that we have no opposition this year or we would certainly have made a poor resistance. I can see no way on which matters would be better arranged under existing circumstances than the way in which you have arranged it. If Chaboillez, and George will act in unison and according to your instructions, they will do well, but I am somewhat affeared, that this will not be the case, as I think George might perhaps from jealously refuse to obey Chaboillez or give him the proper help. Our building business prevents me from going there myself. I suppose you have now received my letter of last Sept, in which I mentioned that I had kept the Doctor here. I shall send him in a few days to see how matters comes on at the Ance. The Davenports are wanted at present in FDLac should it be necessary to make any alteration. I shall leave the Doctor at the Ance.

Undated photograph of the ABCFM Presbyterian Mission Church at it’s original 1830s location along the shoreline of Sandy Bay.

~ Madeline Island Museum

In addition to the AFC’s new La Pointe, Warren was also committed to the establishment of a mission for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) as a condition of his 1827 Deed for Old La Pointe from his Chippewa wife’s parents; Madeline & Michel Cadotte.

Starting in 1830, the ABCFM built a Mission at La Pointe’s Middleport (second French fort of 1718), where they were soon joined by a new Catholic Mission in 1835.

Madeline Island was still unceded territory until the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe. The AFC and ABCFM had obtained tribal permissions to build here via Warren’s deed, while the Catholics were apparently grandfathered in through French bloodlines from earlier centuries.

I think we will want about 2 Coopers but as you suggest I if they may be got cheaper than the [????] [????]. The Goods Mr Hall has got is for his own use that is to say to pay his men [??]. The [??] [??????] [has?] to pay for a piece of land they bot from an Indian woman at Leech Lake. As far as my information goes the Missionaries have never yet interfered with our trade. Mr Hall’s intention is to have his establishment as much disconnected with regular business as he possibly can and he gets his supplies from us.

[We?] [have?] received the boxes [Angus?] [??] [???]. [You?] mention also a box, but I have not yet received it. Possible it is at the Ance.

The report about Dubay has no doubt been exaggerated. When with me at the Ance he mentioned to me that Mr Aitkin told him he had better tell the Indians not to kill their beaver entirely off and thereby ruin their country. The idea struck me as a good one and as far as I recollect I told him, it would perhaps be good to tell them so. I have not yet heard from any one, that he has tried to prevent the Indians from paying their old Debts and I should not be astonished to fend the whole is one of those falsehoods which Indians are want to use to free themselves from paying old Debts. I consider Dubay a pretty active man, but the last years extravagancies have made it necessary to have an eye upon him to prevent him from squandering.

My health had been somewhat impaired by my voyage from the Sault to this place. Instead of going to Lac Du Flambeau myself as I intended I sent the Doctor. He has just now returned and tells me that Dubay gets along pretty well, though there were some small difficulties which toke place, but which the Dr settled. The prospect are very discouraging, particularly on a/c of provisions. We have plenty opposition and all of them with liquor in great abundance. It is provoking to see ourselves restricted by the laws from taking in liquor while our opponents deal in it as largely as ever. The traders names are as far as could be ascertained Francois Charette and [Chapy?]. The liquor was at Lac du Flambeau while the Doctor was there. I have furnished Dubay with means to procure provisions, as there is actually not 1 Sack of Corn or Rice to be got.

The same is the case on Lac Courtoreilie and Folleavoigne no provisions and a Mr Demarais on the Chippeway River gives liquor to the Indians.

You want my ideas upon the fishing business. If reliance can be put in Mr Aitkin’s assertions we will at least want the quantity of Net thread mentioned in our order. Besides this we will want for our fishing business 200 Barrels Flour, [??] Barrels Pork, 10 Kegs Butter, 1000 Bushels Corn, [??] Barrels Lard, 10 or 11 Barrels Tallow.

Besides this we want over and above the years supply an extra supply for our summer Establishments. say about 80 Barrels Flour, 30 Barrels Pork, 1500 # Butter, 400 Bushels Corn, 5 Barrels Lard, 5 Barrels Tallow. This will is partly to sell. be sold.

Mr Roussain will be as good as any if not better in my opinion for our business than Holiday. Ambrose Davenport might take the charge of the Ance but Roussain will be more able on account of his knowledge in fishing. I would recommend to take him as a partner. say take Holidays share if he could not be got for less.

I have not done much yet toward building. The greatest part of my men have been in the exterior to assist our people to get in. But they have now all arrived. We have got about 4 acres of land cleared, a wintering house put up and a considerable quantity of boards sawed. Mr Aitkin did not supply me with two Carpenters as he promised at Mackinac. I will try to get along as well as I can without them. I engaged Jos Dufault and Mr Aitkin brot me one of Abbott’s men, who he engaged. But I will still be under the necessity of hiring Mr Campbell of the mission to make our windows sashes and to superintend The framing of the buildings. Mr Aitkins have done us considerable damage by not fulfilling his promise in this respect. I told you in Mackinac that Mr Aitkin was far from being exact in business. Your letter to him I will forward by the first opportunity. I think it will have a good effect and you do right in being thus plain in stating your views. His contract deserves censure, and I will hope that your plain dealing with him will not be lost upon him. Shall I beg you to be as faithfull to me by giving me the earliest information whenever you might disapprove of any transaction of mine.

Photograph of La Pointe from Mission Hill circa 1902.

~ Wisconsin Historical Collections, Volume XVI, page 80.

I have received a supply of provisions from Mr Chapmann which will enable me to get through this season. The [?] [of?] [???] [next?], the time you have set for the arrival of the Schooner, will be sufficient, early for our business. The Glass and other materials for finishing of the buildings would be required to be sent up in the first trip but if [we?] [are?] [??] better to have them earlier. If these articles could be sent to the Sault early in the Spring a boat load might be formed of [Some?] and Provisions and sent to the Ance. From there men could be spared at that season of the year to bring the load to this place. In that way there would be no heavy expense incurred and I would be able to have the buildings in greater forwardness.

If the plan should meet your approbation please let me know by the winter express. While Mr Aitkin was here we planned out our buildings. The House will be 86 feet by 26 feet in the clear, the two stores will be put up agreeable to your Draft. We do not consider them to large.

I am afraid I shall not be able to build a wharf in season, but shall do my best to accomplish all that can be done with the means I have.

Undated photograph of Captain John Daniel Angus’ boat at the ABCFM mission dock.

~ Madeline Island Museum

I would wish to call your attention towards a few of the articles in our trade. I do not know how you have been accustomed to buy the Powder whether by the Keg or pound. If a keg is estimated at 50#, there is a great deception for some of our kegs do not contain more than 37 or 40 #s.

Our Guns are very bad particularly the barrels. They splint in the inside after been fired once or twice.

Our Holland twine is better this year than it has been for Years. One dz makes about 20 fathoms, more than last year. But it would be better if it was bleached. The NW Company and old Mr Ermantinger’s Net Thread was always bleached. It nits better and does not twist up when put into the water. Our maitre [??] [???] are some years five strand. Those are too large we have to untwist them and take 2 strands out. Our maitre this year are three strand they are rather coarse but will answer. They are not durable nor will they last as long as the nets of course they have to be [renewed?]. The best maitres are those we make of Sturgeon twine. We [?????] the twine and twist it a little. They last twice as long as our imported maitres. The great object to be gained is to have the maitres as small as possible if they be strong enough. Three coarse strands of twisted together is bulky and soon nits.

Our coarse Shoes are not worth bringing into the country. Strong sewed shoes would cost a little more but they would last longer. The [Booties?] and fine Shoes are not much better.

Our Teakettles used to have round bottoms. This year they are flat. They Indians always prefer the round bottom.

In regard to the observations you have made concerning the Doctor’s deviating from the instructions I gave him on leaving Mackinac, I must in justice to him say that I am now fully convinced in my own mind that he misunderstood me entirely, merely by an expression of mine which was intended by me in regard to his voyage from Mackinac to the Sault but by him was mistaken for the route through Lake Superior. The circumstances has hurt his feelings much and as he at all times does his best for the Interest of the Outfit I ought to have mentioned in my last letter, but it did not strike my mind at that time.

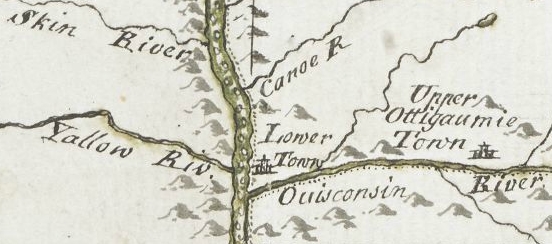

Detail from Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques Nicolas Bellin in 1744.

When Mr Aitkin was here he mentioned to me some information he had obtained from somebody in Fond du Lac who had been in the NW Co service relating to a remarkable good white fish fishery on the “Milleau” or “Millons” Islands (do not know exactly the proper name). They lay right opposite to Point Quiwinau. a vessel which passes between the island and the point can see both. Among Mr Chapmann’s crew here there is an old man who tells me that he knew the place well, he says the island is large, say 50 or 60 miles. The Indian used to make their hunts there on account of the great quantity of Beaver and Reindeer. It is he says where the NWest Co used to make their fishing for Fort William. There is an excellent harbour for the vessel it is there where the largest white fish are caught in Lake Superior. Furthermore the old man says the island is nearer the American shore than the English. Some information might be obtained from Capt. McCargo. If it proves that we can occupy the grounds I have the most sanguine hopes that we shall succeed in the fisheries upon a large scale.

I hope you will gather all the information you can on the subject. Particular where the line runs. If it belongs to the Americans we must make a permanent post on the Island next year under the charge of an active person to conduct the fisheries upon a large scale.

Jh Chevallier one of the men I got in Mackinac is a useless man, he has always been sick since he left Sault. Mr Aitkin advised me to send him back in Chapman’s Boat. I have therefore send him out to the care of Mr Franchere.

By the Winter Express I will to give you all the informations that I may be able to give. I will close by wishing you great health and prosperity. Please present my Respects to Mr Clapp.

I remain Dear Sir.

Very Respectfully Yours

Most Obedient Servant

Lyman M. Warren

To be Continued in 1835…

Lac du Flambeau Reservation: 1842 Boundaries

October 23, 2021

“We do not feel disposed to go away into a strange & unknown country, we desire to remain where our ancestors lay & where their remains are to be seen.“

By Leo

Poking through old archives, sometimes you find the best things where you wouldn’t expect to. The National Archives have been slowly digitizing its Bureau of Indian Affairs microfilms, and for several months, I have been slogging through the thousands of images from the La Pointe Agency. For a change of pace, a few days ago, I checked out the documents on the Sault Ste. Marie Agency films and got my hands on a good one.

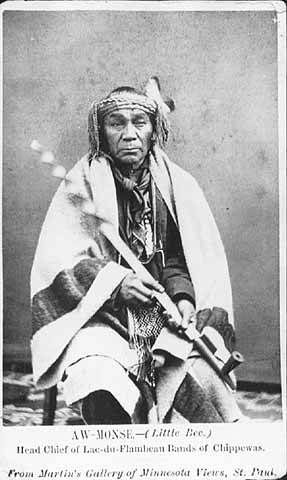

In September of 1847, Aamoons (Little Bee) and some headmen of what had been White Crow’s (Waabishkaagaagi) Lac du Flambeau were facing a serious dilemma. They were on their way home from the annuity payment at La Pointe where the main topic of conversation would certainly have been controversy surrounding the recent treaty at Fond du Lac. Several chiefs refused to sign, and the American Fur Company’ Northern Outfit opposed it due to a controversial provision that would have established a second Ojibwe sub agency on the Mississippi River. They saw this provision as a scheme by Missisippi traders to effect the removal west of all bands east of the Mississippi. Aamoons, himself, did not initially sign the document, but his mark can be found on the back of an envelope sent from La Pointe to Washington.

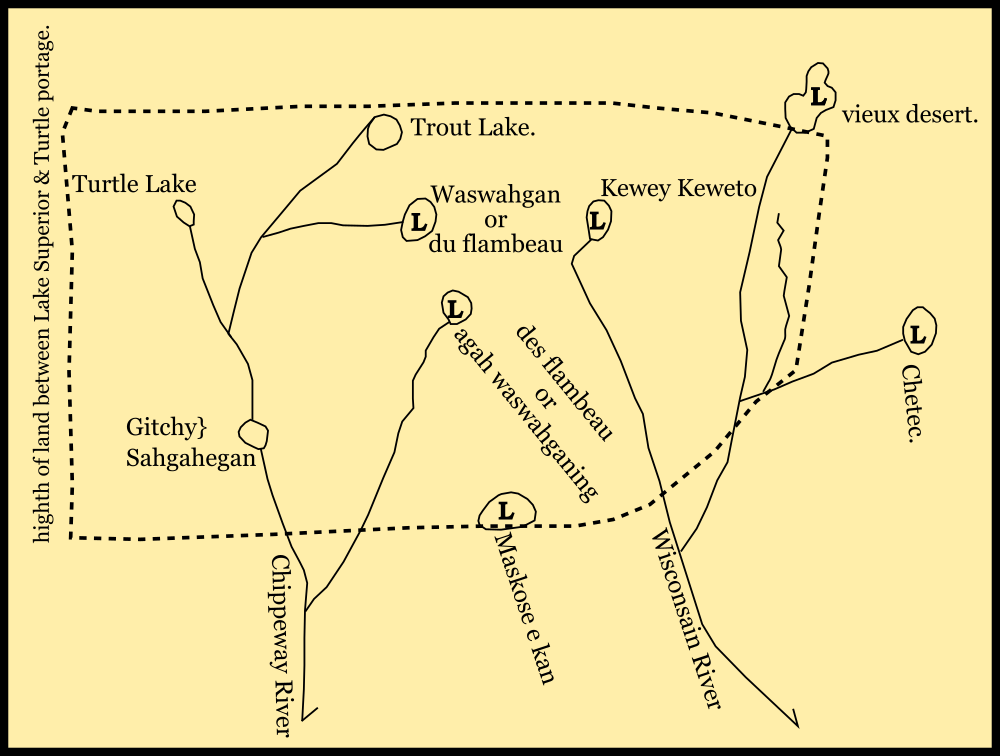

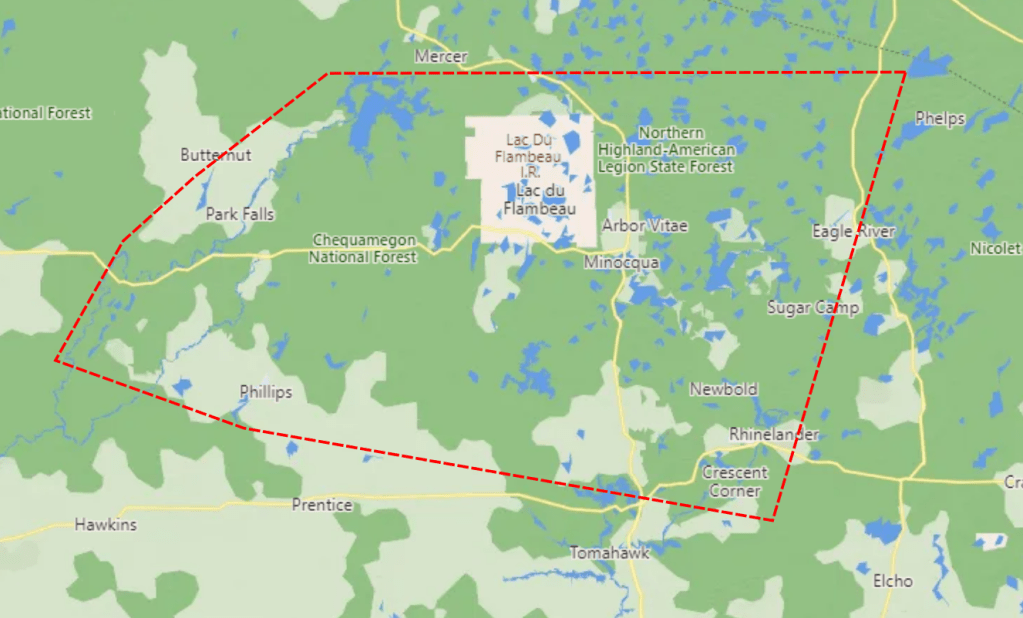

Our old friend George Johnston was returning to his Sault Ste. Marie home from the annuity payments when the Lac du Flambeau men summoned him to the Turtle Portage, near today’s Mercer, Wisconsin. They presented him a map and made speeches suggesting removal would be in direct violation of promises made at the Treaty of La Pointe (1842).

Johnston did not have a position with the American Government at this time, and his trading interests in western Lake Superior were modest. However, he was well known in the country. His grandfather, Waabojiig (White Fisher), was a legendary war chief at Chequamegon, and his parents formed a powerful fur trade couple at the turn of the 19th century. In the 1820s, George served as the first Indian Office sub-agent at La Pointe under his brother-in-law Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. During this time, he developed connections with Ojibwe leaders throughout the Lake Superior country, many of whom he was related to by blood or marriage.

By 1847, Schoolcraft had remarried and left for Washington after the death of his first wife (George’s sister Jane). However, the two men continued to correspond and supply direct intelligence to each other regarding Ojibwe politics. Local Indian Agents attempted to control all communication moving to and from Washington, so in Johnston they likely saw a chance to subvert this system and press their case directly.

The document that emerged from this 174 year old meeting is notable for a few reasons. It further bolsters the argument that the Ojibwe did not view their land cessions in the 1837 and 1842 treaties as requiring them to leave their villages in the east. That point that has been argued for years, but here we have a document where the chiefs speak of specific promises. It also reinforces the notion that the various political factions among the Lake Superior chiefs were coalescing around a policy of promoting reservations as an alternative to removal. This seems obvious now, but reservations were a novel concept in the 1840s, and certainly the United States ceding land back to Indian nations east of the Mississippi would have been unheard of. Knowing this was part of the discussion in 1847 makes the Sandy Lake Tragedy, three years later, all the more tragic. The chiefs had the solution all along, and had the Government just listened to the Ojibwe, hundreds of lives would have been spared.

Finally, the document, especially the map, should be of interest to the modern Lac du Flambeau Band as it appears its reservation should be much larger, encompassing the historical villages at Turtle Portage and Trout Lake as well as Aamoons’ village at Lac du Flambeau proper. The borders also seem to approach, but not include the villages at Vieux Desert and Pelican Lake, which will be interesting to the modern Sokaogon and Lac Vieux Desert Bands.

Saut Ste. Marie

Augt 28th 1848.

Dear sir,

On reaching the turtle portage during the past fall; I was addressed by the Indians inhabiting, the Lac du Flambeau country and they presented me with a map of that region, also a petition addressed to you which I will herein insert, they were under an impression that you could do much in their behalf. The object of delineating a map is to show to the department, the tract of country they reserved for themselves, at the treaty of 1842, concluded by Robert Stuart at Lapointe during that period, and which now appears to be included in that treaty, without any reserve to the Indians of that region, and who expressly stated through me that they were willing to sell their mineral lands, but would retain the tract of country delineated on the map; This forms an important grievance in that region. I designed to have forwarded to you during the past winter their map & petition, but having mislaid it, I did not find it till this day, in an accidental manner, and I now feel that I am bound in duty to forward it to you.

The petition of the Chiefs Ahmonce, Padwaywayashe, Oshkanzhenemais & Say Jeanemay.

My Father (addressing Mr. Schoolcraft.)

Padwaywayashe rose and said, It is not I that will now speak on this occasion, it is these three old men before you, they are related to our ancestors, that man (pointing to Say Jeanemay will be their spokesman,

Sayjeanemay rose and said,

My Father, (addressing himself to Mr. Schoolcraft.)

Padwaywayahshe who has just now ceased speaking is the son of the late Kakabishin an ancient Chief who was lost many years ago in lower Wisconsain, and the white people have not as yet found him, and his Father was one of the first who received the Americans when they landed on the Island of Mackinac. Kishkeman and Kahkahbeshine are the two first chiefs that shook hands with the Americans, The Indian agent then told them that he had arrived and had come to be a friend to them, they who were living in the high mountains, and he saw that they were poor and he was come to rekindle their fire, and the American Indian Agent then gave Kish Keman a large flag and a large silver medal, and said to him, you will never meet with a bad day, the sky will always be bright before you.

My Father.

Our old chief the white crow died last dall, he went to the treaty held at St. Peters, and reached that point when the treaty was almost concluded, and he heard very little of it, and it was not him who sold our lands, it was an Indian living beyond the pillager band of Indians. We feel much grieved at heart, we are now living without a head, and had we reached St. Peters in time, the person who sold our lands would not have been permitted to do so, we should have made provision for ourselves and for our children, We do not now see the bright sky you spoke of to us, we see the return of the bad day I was in the habit of seeing before you came to renew my fire, and now it is again almost extinguished.

My Father;

We feel very much grieved; had my chief been present I should not have parted with my lands, and we find that the commissioner who treated with us, (meaning Mr. R. Stuart) has taken advantage of our ignorance, and bought our lands at his own price, and we did not sell the tract delineated on our map.

My Father;

We do not feel disposed to go away into a strange & unknown country, we desire to remain where our ancestors lay & where their remains are to be seen. We now shake hands with you hope that you will answer us soon.

Turtle portage 11th Sep; 1847.

In presence of}

Geo. Johnston.

Ahmonce his X mark

Padwaywayahshe his X mark

Oshkanzhenemay his X mark

Sayjeaneamy his X mark

To,

Henry R. Schoolcraft Esq.

Washington

N.B. All the country lying within the dotted lines embraces the country, the Chief Monsobodoe & others reserved at the Lapointe treaty and which now is embraced in the Treaty articles, and could not be misunderstood by Mr. Stuart and as I have already remarked forms an important grievance. All of which is respectfully submitted by

Respectfully

Your obt Servant

Geo. Johnston.

Henry R. Schoolcraft Esq.

Washington.

Respectfully referred from my files to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs

H.R.S

14th Feb 1849

Ahmonce (Aamoons), is found in many documents from the 1850s and 60s as the successor chief to the band once guided by his father Waabishkaagaagi (White Crow), uncle Moozobodo (Moose Muzzle), and grandfather Giishkiman (Sharpened Stone). The latter two are spelled Monsobodoe and Kishkeman in this document. Gaakaabishiinh (Kahkabeshine) “Screech Owl,” is probably the “old La Chouette” recorded in Malhiot’s Lac du Flambeau journal in the winter of 1804-05.

“The Americans when they landed on the Island of Mackinac” refers to the surrender of the British garrison at the end of the War of 1812, which is often referenced as the start of American assertions of sovereignty over the Ojibwe country. Despite Sayjeanemay’s lofty friendship rhetoric, it should be noted that many Ojibwe warriors fought with the British against the United States and political relations with the British crown and Ojibwe bands on the American side would continue for the next forty years.

The speaker who dominated the 1837 negotiations, and earned the scorn of the Lake Superior Bands, was Maajigaabaw or “La Trappe.” He, Flat Mouth, and Hole-in-the-Day, chiefs of the Mississippi and Pillager Bands in what is now Minnesota, were more inclined to sell the Wisconsin and Chippewa River basins than the bands who called that land home. This created a major rift between the Lake Superior and Mississippi Ojibwe.

Pa-dua-wa-aush (Padwaywayahshe) is listed under Aamoons’ band in the 1850 annuity roll. Say Jeanemay appears to be an English phonetic rendering of the Ojibwe pronunciation of the French name St. Germaine. A man named “St. Germaine” with no first name given appears in the same roll in Aamoons’ band. The St. Germaines were a mix-blood family with a long history in the Flambeau Country, but this man appears to be too old to be a child of Leon St. Germaine and Margaret Cadotte. From the text it appears this St. Germaine’s family affiliated with Ojibwe culture, in contrast to the Johnstons, another mix-blood family, who affiliated much more strongly with their father’s Anglo-Irish elite background. So far, I have not been able to find another mention of Oshkanzhenemay.

Moozobodo was not present at the Treaty of La Pointe (1842) as he died in 1831. Johnston may be confusing him with his brother Waabishkaagaagi

The timing of Schoolcraft’s submission of this document to the Indian Department is curious. In February 1849, a delegation of chiefs, mostly from villages near Lac du Flambeau was in Washington D.C. to petition President Polk for reservations. Schoolcraft worked to undermine this delegation. Had he instead promoted the cause of reservations over removal, one wonders if he could have intervened to prevent the Sandy Lake debacle.

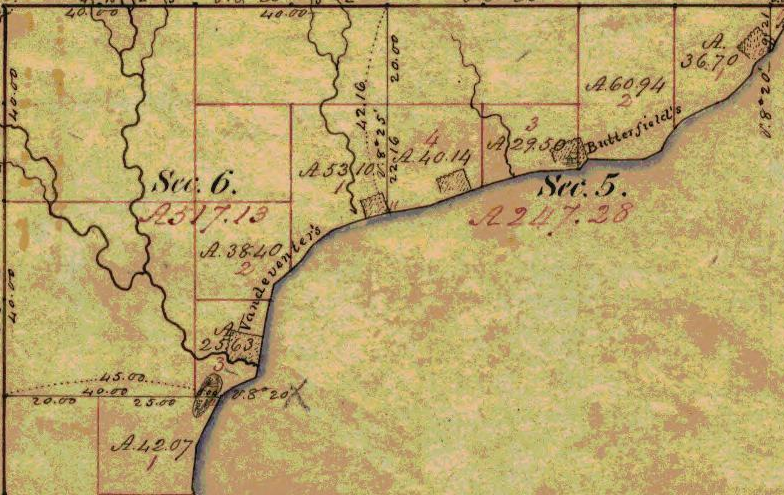

Map of Lac du Flambeau Reservation as understood by Ojibwe at Treaty of La Pointe 1842. Apparently drawn from memory 11 September 1847 by Lac du Flambeau chiefs, copied and presumably labelled by George Johnston. Microfilm slide made available online by National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/164363909 Image 340.

Alleged reservation boundaries agreed to in 1842 roughly superimposed over modern map. The Treaty of La Pointe (1854) called for three townships for the Lac du Flambeau Band–the white square on this map showing the modern reservation. Had the 1842 boundaries held, the reservation would have been much larger and included several popular resort communities.

An Incident of Chegoimegon

November 26, 2016

By Amorin Mello

This is a reproduction of “An Incident of Chegoimegon – 1760” from Report and Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: For the years 1877, 1878 and 1879. Volume VIII., pages 224-226.

—

AN INCIDENT OF CHEGOIMEGON – 1760.*

—

We have been permitted to extract the following from the journal of a gentleman who has seen a large portion of the country to the north and west of this place, and to whose industry our readers have been often indebted for information relating to the portion of country over which he has passed, and to transactions among the numerous tribes, within the limits of this territory, which tend to elucidate their characteristics, and lay open the workings of their untaught minds:

Detail of Isle de la Ronde from Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin; published in Charlevoix’s Histoire et Description Générale de Nouvelle France, Paris, 1744.

Monecauning (abbreviated for “Monegoinaic-cauning,” the Woodpecker Island, in Chippewa language) – which is sometimes called Montreal Island, Cadott’s Island, or Middle Island, and is one of “the Apostles” mentioned by Charlevoix. it is situated in Lake Superior, about ninety miles from Fond du Lac, at the extremity of La Pointe, or Point Chegoimegon.

On this island the French Government had a fort, long previous to its surrender to the English, in 1763. It was garrisoned by regular soldiers, and was the most northern post at which the French king had troops stationed. It was never re-occupied by the English, who removed everything valuable to the Sault de St. Marie, and demolished the works. It is said to have been strongly fortified, and the remains of the works may yet be seen.

In the autumn of 1760, all of the traders except one, who traded from this post, left it for their wintering grounds. He who remained had with him his wife, who was a lady from Montreal, his child – a small boy, and one servant. During the winter, the servant, probably for the purpose of plunder, killed the trader and his wife; and a few days after their death, murdered the child. He continued at the fort until the spring. When the traders came, they enquired for the gentleman and his family; and were told by the servant, that in the month of March, they left him to go to their sugar camp, beyond the bay, since which time he had neither seen nor heard them. The Indians, who were somewhat implicated by this statement, were not well satisfied with it, and determined to examine into its truth. They went out and searched for the family’s tracks; but found none, and their suspicions of the murderer increased. They remained perfectly silent on the subject; and when the snow had melted away, and the frost left the ground, they took sharp stakes and examined around the fort by sticking them into the ground, until they found three soft spots a short distance from each other, and digging down they discovered the bodies.

The servant was immediately seized and sent off in an Indian canoe, for Montreal, for trial. When passing the Longue Saut, in the river St. Lawrence, the Indians who had him in charge, were told of the advances of the English upon Montreal, and that they could not in safety proceed to that place. They at once became a war party, – their prisoner was released, and he joined and fought with them. Having no success, and becoming tired of the war, they sought their own land – taking the murderer with them as one of their war party.

They had nearly reached the Saut de St. Marie, when they held a dance. During the dance, as is usual, each one “struck the post,” and told, in his manner, of his exploits. The murderer, in his turn, danced up to the post, and boasted that he had killed the trader and his family – relating all the circumstances attending the murder. The chief heard him in silence, saving the usual grunt, responsive to the speaker. The evening passed away, and nothing farther occurred.

The next day the chief called his young men aside, and said to them: “Did you not hear this man’s speech last night? He now says that he did the murder with which we charged him. He ought not to have boasted of it. We boast of having killed our enemies – never our friends. Now he is going back to the place where committed the act, and where we live – perhaps he will again murder. He is a bad man – neither we nor our friends are safe. If you are of my mind, we will strike this man on the head.” They all declared themselves of his opinion, and determined that justice should be rendered him speedily and effectually.

They continued encamped, and made a feast, to which the murderer was invited to partake. They filled his dish with an extravagant quantity, and when he commenced his meal, the chief informed him, in a few words, of the decree in council, and that as soon as he had finished his meal, either by eating the whole his dish contained, or as much as he could, the execution was to take place. The murderer, now becoming sensible of his perilous situation, from the appearance of things around him, availed himself of the terms of the sentence he had just heard pronounced, and did ample justice to the viands. He continued, much to the discomfiture of the “phiz” of justice (personified by the chief, who all the while sat smoking through his nose), eating and drinking until he had sat as long as a modern alderman at a corporation dinner. But it was of no avail – when he ceased eating he ceased breathing.

The chief cut up the body of the murderer, and boiled it for another feast – but his young men would touch none of it – they said, “he was not worthy to be eaten – he was worse than a bad dog. We will not taste him, for if we do, we shall be worse than dogs ourselves.”

Mr. Morrison, who gave me the above relation, told me he had it from a very old Indian, who was present at the death of the murderer.

* – This paper was originally published in the Detroit Gazette, Aug. 30, 1822. Hon. C. C. Throwbridge of Detroit, a resident of that place for sixty years, states that Mr. Schoolcraft, without doubt, contributed this sketch to the Gazette; that Mr. Schoolcraft, at the time of its publication, was residing at the Saut St. Marie: and Mr. Morrison, who was one of Mr. Astor’s most trusted agents at “L’Anse Qui-wy-we-nong,” came down to Mackinaw every summer, and thus gave Mr. Schoolcraft the information.

L. C. D.

Among The Otchipwees: III

July 20, 2016

By Amorin Mello

… continued from Among The Otchipwees: II

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 4 February 1885

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 335-342.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

III.

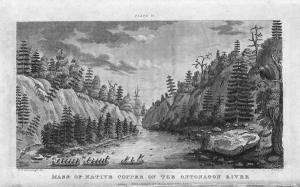

The Northern tribes have nothing deserving the name of historical records. Their hieroglyphics or pictorial writings on trees, bark, rocks and sheltered banks of clay relate to personal or transient events. Such representations by symbols are very numerous but do not attain to a system.

Their history prior to their contact with the white man has been transmitted verbally from generation to generation with more accuracy than a civilized people would do. Story-telling constitutes their literature. In their lodges they are anything but a silent people. When their villages are approached unawares, the noise of voices is much the same as in the camps of parties on pic-nic excursions. As a voyageur the pure blood is seldom a success, and one of the objections to him is a disposition to set around the camp-fire and relate his tales of war or of the hunt, late into the night. This he does with great spirit, “suiting the action to the word” with a varied intonation and with excellent powers of description. Such tales have come down orally from old to young many generations, but are more mystical than historical. The faculty is cultivated in the wigwam during long winter nights, where the same story is repeated by the patriarchs to impress it on the memory of the coming generation. With the wild man memory is sharp, and therefore tradition has in some cases a semblance to history. In substance, however, their stories lack dates, the subjects are frivolous or merely romantic, and the narrator is generally given to embellishment. He sees spirits everywhere, the reality of which is accepted by the child, who listens with wonder to a well-told tale, in which he not only believes, but is preparing to be a professional story-teller himself.

Indian picture-writings and inscriptions, in their hieroglyphics, are seen everywhere on trees, rocks and pieces of bark, blankets and flat pieces of wood. Above Odanah, on Bad River, is a vertical bank of clay, shielded from storms by a dense group of evergreens. On this smooth surface are the records of many generations, over and across each other, regardless of the rights of previous parties. Like most of their writings, they relate to trifling events of the present, such as the route which is being traveled; the game killed; or the results of a fight. To each message the totem or dodem of the writer is attached, by which he is at once recognized. But there are records of some consequence, though not strictly historical.

Charles Whittlesey also reproduced Okandikan’s autobiography in Western Reserve Historical Society Tract 41.

Before a young man can be considered a warrior, he must undergo an ordeal of exposure and starvation. He retires to a mountain, a swamp, or a rock, and there remains day and night without food, fire or blankets, as long as his constitution is able to endure the exposure. Three or four days is not unusual, but a strong Indian, destined to be a great warrior, should fast at least a week. One of the figures on this clay bank is a tree with nine branches and a hand pointing upward. This represents the vision of an Indian known to one of my voyagers, which he saw during his seclusion. He had fasted nine days, which naturally gave him an insight of the future, and constituted his motto, or chart of life. In tract No. 41 (1877), of the Western Reserve Historical Society, I have represented some of the effigies in this group; and also the personal history of Kundickan, a Chippewa, whom I saw in 1845, at Ontonagon. This record was made by himself with a knife, on a flat piece of wood, and is in the form of an autobiography. In hundreds of places in the United States such inscriptions are seen, of the meaning of which very little is known. Schoolcraft reproduced several of them from widely separated localities, such as the Dighton Boulder, Rhode Island; a rock on Kelley’s Island, Lake Erie, and from pieces of birch bark, conveying messages or memoranda to aid an orator in his speeches.

~ New Sources of Indian History, 1850-1891: The Ghost Dance and the Prairie Sioux, A Miscellany by Stanley Vestal, 2015, page 269.

The “Indian rock” in the Susquehanna River, near Columbia, Pennsylvania; the God Rock, on the Allegheny, near Brady’s Bend; inscriptions on the Ohio River Rocks, near Wellsville, Ohio, and near the mouth of the Guyandotte, have a common style, but the particular characters are not the same. Three miles west of Barnsville, in Belmont County, Ohio, is a remarkable group of sculptured figures, principally of human feet of various dimensions and uncouth proportions. Sitting Bull gave a history of his exploits on sheets of paper, which he explained to Dr. Kimball, a surgeon in the army, published in fascimile in Harper’s Weekly, July 1876. Such hieroglyphics have been found on rocky faces in Arizona, and on boulders in Georgia.

Pointe De Froid is the northwestern extremity of La Pointe on Madeline Island. Map detail from 1852 PLSS survey.

~ Report of a geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota: and incidentally of a portion of Nebraska Territory, by David Dale Owen, 1852, page 420.

~ Geology of Wisconsin: Paleontology by R. P. Whitfield, 1880, page 58.

While pandemonium was let loose at La Pointe towards the close of the payment we made a bivouac on the beach, between the dock and the mission house. The voyageurs were all at the great finale which constitutes the paradise of a Chippewa. One of my local assistants was playing the part of a detective on the watch for whisky dealers. We had seen one of them on the head waters of Brunscilus River, who came through the woods up the Chippewa River. Beyond the village of La Pointe, on a sandy promontory called Pointe au Froid, abbreviated to Pointe au Fret or Cold Point, were about twenty-five lodges, and probably one hundred and fifty Indians excited by liquor. For this, diluted with more than half water, they paid a dollar for each pint, and the measure was none too large – neither pressed down nor running over. Their savage yells rose on the quiet moon-lit atmosphere like a thousand demons. A very little weak whisky is sufficient to work wonders in the stomach of a backwoods Indian, to whom it is a comparative stranger. About midnight the detective perceived our traveler from the Chippewa River quietly approaching the dock, to which he tied his canoe and went among the lodges. To the stern there were several kegs of fire-water attached, but weighted down below the surface of the water. It required but a few minutes to haul them in and stave the heads of all of them. Before morning there appeared to be more than a thousand savage throats giving full play to their powerful lungs. Two of them were staggering along the beach toward where I lay, with one man by my side. he said we had better be quiet, which, undoubtedly, was good advice. They were nearly naked, locked arm in arm, their long hair spread out in every direction, and as they swayed to and fro between the water line and the bushes, no imagination could paint a more complete representation of the demon. There was a yell to every step – apparently a bacchanalian song. They were within two yards before they saw us, and by one leap cleared everything, as though they were as much surprised as we were. The song, or howl, did not cease. It was kept up until they turned away from the beach into the mission road, and went on howling over the hill toward the old fort. It required three days for half-breed and full-blood alike to recover from the general debauch sufficiently to resume the oar and pack. As we were about to return to the Penoka Mountains, a Chippewa buck, with a new calico shirt and a clean blanket, wished to know if the Chemokoman would take him to the south shore. He would work a paddle or an oar. Before reaching the head of the Chegoimegon Bay there was a storm of rain. He pulled off his shirt, folded it and sat down upon it, to keep it dry. The falling rain on his bare back he did not notice.

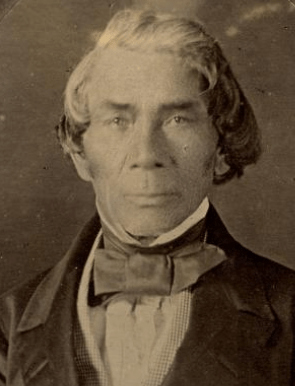

Portrait of Stephen Bonga

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

We had made the grand portage of nine miles from the foot of the cataract of the St. Louis, above Fond du Lac, and encamped on the river where the trail came to it below the knife portage. In the evening Stephen Bungo, a brother of Charles Bungo, the half-breed negro and Chippewa, came into our tent. He said he had a message from Naugaunup, second chief of the Fond du Lac band, whose home as at Ash-ke-bwau-ka, on the river above. His chief wished to know by what authority we came through the country without consulting him. After much diplomatic parley Stephen was given some pequashigon and went to his bivouac.

Joseph Granville Norwood

~ Wikipedia.org

Portrait of Naagaanab

~ Minnesota Historical Society

The next morning he intimated that we must call at Naugaunup’s lodge on the way up, where probably permission might be had, by paying a reasonable sum, to proceed. We found him in a neat wigwam with two wives, on a pleasant rise of the river bluff, clear of timber, where there had been a village of the same name. His countenance was a pleasant one, very closely resembling that of Governor Corwin, of Ohio, but his features were smaller and also his stature. Dr. Norwood informed him that we had orders from the Great Father to go up the St. Louis to its source, thence to the waters running the other way to the Canada line. Nothing but force would prevent us from doing this, and if he was displeased he should make a complaint to the Indian agent at La Pointe, and he would forward it to Washington. We heard no more of the invasion of his territory, and he proceeded to do what very few Chippewas will do, offered to show us valuable minerals. In the stream was a pinnacle of black sale, about sixty feet high. Naugaunup soon appeared from behind it, near the top, in a position that appeared to be inaccessible, a very picturesque object pointing triumphantly to some veins of white quartz, which are very common in metamorphic slate.

Those who have heard him, say that he was a fine orator, having influence over his band, a respectable Indian, and a good negotiator. If he imagined there was value in those seams of quartz it is quite remarkable and contrary to universal practice among Chippewas that he should show them to white men. They claim that all minerals belong to the tribe. An Indian who received a price for showing them, and did not give every one his share, would be in danger of his life. They had also a superstitious dread of some great evil if they disclosed anything of the kind. Some times they promise to do so, but when they arrive at the spot, with some verdant white man, expecting to become suddenly rich, the Great Spirit or the Bad Manitou has carried it away. I have known more than one such instance, where persons have been sustained by hopeful expectation after many days of weary travel into the depths of the forest. The editor of the Ontonagon Miner gives one of the instances in his experience:

“Many years ago when Iron River was one of the fur stations, of John Jacob Astor and the American Fur Company, the Indians were known to have silver in its native state in considerable quantities.”

Men are now living who have seen them with chunks of the size of a man’s fist, but no one ever succeeded in inducing them to tell or show where the hidden treasure lay. A mortal dread clung to them, that if they showed white men a deposit of mineral the Great Manitou would punish them with death.

Several years since a half-breed brought in very fine specimens of vein rock, carrying considerable quantities of native silver. His report was that his wife had found it on the South Range, where they were trapping. To test his story he was sent back for more. In a few days he returned bringing with him quite a chunk from which was obtained eleven and one-half ounces of native silver. He returned home, went among the Flambeaux Indians and was killed. His wife refused to listen to any proposals or temptation from friend or foe to show the location of this vein, clinging with religious tenacity to the superstitious fears of her tribe.

When the British had a fort on St. Joseph’s Island in the St. Mary’s River, in the War of 1812, an Indian brought in a rich piece of copper pyrites. The usual mode of getting on good terms with him, by means of whisky, failed to get from him the location of the mineral. Goods were offered him; first a bundle, then a pile, afterwards a canoe-load, and finally enough to load a Mackinaw boat. No promise to disclose the place, no description or hint could be extorted. It was probably a specimen from the veins on the Bruce or Wellington mining property, only about twenty miles distant on the Canadian shore.

Detail of John Beargrease the Younger from stereograph “Lake Superior winter mail line” by B. F. Childs, circa 1870s-1880s.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

Crossing over the portage from the St. Louis River to Vermillion River, one of the voyageurs heard the report of a distant shot. They had expected to meet Bear’s Grease, with his large family, and fired a gun as a signal to them. The ashes of their fire were still warm. After much shouting and firing, it was evident that we should have no Indian society at that time. That evening, around an ample camp fire, we heard the history of the old patriarch. His former wives had borne him twenty-four children; more boys than girls. Our half-breed guide had often been importuned to take one of the girls. The old father recommended her as a good worker, and if she did not work he must whip her. Even a moderate beating always brought her to a sense of her duties. All he expected was a blanket and a gun as an offset. He would give a great feast on the occasion of the nuptials. Over the summit to Vermillion, through Vermillion Lake, passing down the outlet among many cataracts to the Crane Lake portage, there were encamped a few families, most of them too drunk to stand alone. There were two traders, from the Canada side, with plenty of rum. We wanted a guide through the intricacies of Rainy Lake. A very good-looking savage presented himself with a very unsteady gait, his countenance expressing the maudlin good nature of Tam O’Shanter as he mounted Meg. Withal, he appeared to be honest. “Yes, I know that way, but, you see, I’m drunk; can’t you wait till to-morrow.” A young squaw who apparently had not imbibed fire-water, had succeeded in acquiring a pewter ring. Her dress was a blanket of rabbit skins, made of strips woven like a rag carpet. It was bound around her waist with a girdle of deer’s hide, answering the purpose of stroud and blanket. No city belle could exhibit a ring of diamonds more conspicuously and with more self-satisfaction than this young squaw did her ring of pewter.

As we were all silently sitting in the canoes, dripping with rain, a sudden halloo announced the approach of living men. It was no other than Wau-nun-nee, the chief of the Grand Fourche bands, who was hunting for ducks among the rice. More delicious morsels never gladdened the palate than these plump, fat, rice-fed ducks. Old Wau-nun-nee is a gentleman among Indian chiefs. His band had never consented to sell their land, and consequently had no annuities. He even refused to receive a present from the Government as one of the head men of the tribe, preferring to remain wholly independent. We soon came to his village on Ash-ab-ash-kaw Lake. No band of Indians in our travels appeared as comfortable or behaved as well as this. Their country is well supplied with rice and tolerably good hunting ground. The American fur dealers (I mean the licensed ones) do not sell liquor to the Indians, and use their influence to aid Government in keeping it from them. Wau-nun-nee’s baliwick was seldom disturbed by drunken brawls. His Indians had more pleasant countenances than any we had seen, with less of the wild and haggard look than the annuity Indians. It was seldom they left their grounds, for they seldom suffered from hunger. They were comfortably clothed, made no importunities for kokoosh or pequashigon, and in gratifying their savage curiosity about our equipments they were respectful and pleasant. In his lodge the chief had teacups and saucers, with tea and sugar for his white guests, which he pressed us to enjoy. But we had no time for ceremonials, and had tea and sugar of our own. Our men recognized numerous acquaintances among the women, and as we encamped near a second village at Round Lake they came to make a draft on our provision chest. We here laid in a supply of wild rice in exchange for flour. Among this band we saw bows and arrows used to kill game. They have so little trade with the whites, and are so remote from the depots of Indian goods, that powder and lead are scarce, and guns also. For ducks and geese the bow and arrow is about as effectual as powder and shot. In truth, the community of which Wau-nun-nee was the patriarch came nearer to the pictures of Indians which poets are fond of drawing than any we saw. The squaws were more neatly clad, and their hair more often combed and braided and tied with a piece of ribbon or red flannel, with which their pappooses delighted to sport. There were among them fewer of those distinguished smoke-dried, sore-eyed creatures who present themselves at other villages.

By my estimate the channel, as we followed it to the head of the Round Lake branch, is two hundred and two mile in length, and the rise of the stream one hundred and eight feet. The portage to a stream leading into the Mississippi is one mile.

At Round Lake we engaged two young Indians to help over the portage in Jack’s place. Both of them were decided dandies, and one, who did not overtake us till late the next morning, gave an excuse that he had spent the night in courting an Indian damsel. This business is managed with them a little differently than with us. They deal largely in charms, which the medicine men furnish. This fellow had some pieces of mica, which he pulverized, and was managing to cause his inamorata to swallow. If this was effected his cause was sure to succeed. He had also some ochery, iron ore and an herb to mix with the mica. Another charm, and one very effectual, is composed of a hair from the damsel’s head placed between two wooden images. Our Lothario had prepared himself externally so as to produce a most killing effect. His hair was adorned with broad yellow ribbons, and also soaked in grease. On his cheeks were some broad jet black stripes that pointed, on both sides, toward his mouth; in his ears and nose, some beads four inches long. For a pouch and medicine bag he had the skin of a swan suspended from his girdle by the neck. His blanket was clean, and his leggings wrought with great care, so that he exhibited a most striking collection of colors.

At Round Lake we overtook the Cass Lake band on their return from the rice lakes. This meeting produced a great clatter of tongues between our men and the squaws, who came waddling down a slippery bank where they were encamped. There was a marked difference between these people and those at Ash-ab-ash-kaw. They were more ragged, more greasy, and more intrusive.

CHARLES WHITTLSEY.

By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from Copper Harbor Redux.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 29, 1845.

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE.

—

[From our regular correspondent.]

ST. LOUIS, Mo. Aug. 19, 1845.