1838 more Petitions from La Pointe to the President

April 16, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs:

La Pointe Agency 1831-1839

National Archives Identifier: 164009310

O.I.A. Lapointe W.692.

Governor of Wisconsin

Mineral Pt. 15 Oct. 1838.

Encloses two communications

from D. P. Bushnell; one,

to speech of Jean B. DuBay, a half

breed Chippewa, delivered Aug. 15, ’38,

on behalf of the half breeds then assembled,

protesting against the decision

of the U.S. Court on the subject of the

murder of Alfred Aitkin by an Ind,

& again demanding the murderer;

with Mr Bushnell’s reply: the other,

dated 14 Aug. 1838, being a Report

in reference to the intermeddling of

any foreign Gov’t or its officers, with

the Ind’s within the limits of the U.S.

[Sentence in light text too faint to read]

12 April 1839.

Rec’d 17 Nov 1838.

See letter of 7 June 39 to Hon Lucius Lyon

Ans’d 12 April, 1839

W Ward

Superintendency of Indian Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point Oct 15, 1838.

Sir:

I have the honor to enclose herewith two communications from D. P. Bushnell Esq, Subagent of the Chippewas at La Pointe; the first, being the Speech of Jean B. DuBay, a half breed Chippewa, on behalf of the half-breeds assembled at La Pointe, on the 15th august last, in relation to the decision of the U.S. Court on the subject of the murder of Alfred Aitkin by an Indian; the last, in reference to the intermeddling of any foreign government, or the officers thereof, with the Indians within the limits of the United States.

Very respectfully

Your obed’t serv’t.

Henry Dodge

Sup’t Ind. Affs.

Hon. C. A. Harris

Com of Ind. Affairs.

D. P. Bushnell Aug. 14, 1838

W692

Subagency

La Pointe Aug 14th 1838

Sir

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your communication dated 7 ultimo enclosing an extract from a Resolution of the House of the Representatives of the 19th of March, 1838. No case of intermeddling by any foreign government on the officers, or subject thereof with the Indians under my charge or any others, directly , or indirectly, has come to my knowledge. It is believed that the English government has been in the Habit of distributing presents at a point on Lake Huron below Drummonds Island to the Chippewa for a series of years.

The Indians from this region, until recently, visited that place for their share of the annual distribution. But the Treaty made last summer between them and the United States, and the small distribution of presents that has been made within the Last Year, under the direction of our government, have had the effect to permit any of them from visiting, the English Territory this year. These Indians have generally manifested a desire to live upon terms of friendship with the American people. All of the Chiefs from the region of Lake Superior have expressed a desire to visit the seat of Gov’t where none of them have yet been. There is no doubt, but such a visit with the distribution of a few presents among them would be productive: of much good, and render their attachment to our Gov’t still stronger.

Very Resp’y

yr ms ob sev’t

D. P. Bushnell.

I. O. A.

To

His Excellency Henry Dodge

Ter, Wisconsin Sup’t Ind Affs

Half breed Speech

Speech of Jean B. DuBay,

a half breed Chippewa, on behalf of the half breeds assembled in a numerous body at the United States Sub Indian Agency office at La Pointe, on the 15th day of August 1838.

Father. We have come to you for the purpose of speaking on the subject of the murder that was committed two years ago by an Indian on one of our Brothers. I allude to Alfred Aitken. We have always considered ourselves Subject to the Laws of the United States and have consequently relied upon their protection. But it appears by the decision of the United Sates court in this case. “That it was an Indian Killed an Indian, on Indian ground, and died not therefore come under its jurisdiction,” that we have hitherto laboured under a delusion, and that a resort to the laws can avail nothing. We come therefore to you, at the agent of the Government here, to tell you that we have councilled with the Indians and, have declared to them and we have solemnly pledged ourselves in your presence, to each other, that we will enforce in the Indian Country, the Indian Law, Blood for Blood.

We pay taxes, and in the Indian Country are held amenable to the Laws, but appeal to them in vain for protection. Sir we will protect ourselves. We take the case into our own hands. Blood shall be shed! We will have justice and who can be answerable for the consequences? Our brother was a gentlemanly young man. He was educated at a Seminary in Louville in the State of New York. He was dear to us. We remember him as the companion of our childhood. The voice of his Blood now cries to us from the ground for vengence! But the stain left by his you shall be washed out by one of a deeper dye!

For injuries committed upon the persons or property of whites, although within the Indian Country we are still willing to be held responsible to the Laws of the United States, notwithstanding the decision of a United States Court that we are Indians. And for like injuries committed upon us by whites we will appeal to the same tribunal.

Sir our attachments to the American Government and people was great. But they have cast us off. The Half breeds muster strong on the northwestern frontier & we Know no distinction of tribes. In one thing at least we are all united. We might muster into the service of the United States in case of a war and officered by Americans would compose in frontier warfare a formidable corps. We can fight the Indian or white man, in his own manner, & would pledge ourselves to Keep peace among the different Indian tribes.

Sir we will do nothing rashly. We once more ask from your hands the murder of Mr. Aitken. We wish you to represent our case to the President and we promise to remain quiet for one year, giving ample time for his decision to be made Known. Let the Government extend its protection to us and we will be found its staunchest friends. If it persists in abandoning us the most painful consequences may ensue.

Sir we will listen to your reply, and shall be Happy to avail ourselves of your advice.

Reply of the Subagent.

My friends, I have lived several years on the frontier & have Known many half breeds. They have to my Knowledge paid taxes, & held offices under State, Territorial, and United States authorities, been treated in every respect by the Laws as American Citizens; and I have hitherto supposed they were entitled to the protection of the Laws. The decision of the court is this case, if court is a virtual acknowledgement of your title to the Indians as land, in common with the Indians & I see no other way for you to obtain satisfaction then to enforce the Indian Law. Indeed your own safety requires it. in the meantime I think the course you have adopted, in awaiting the results of this appeal is very proper, and cannot injure your cause although made in vain. At your request I will forward the words of your speaker, through the proper channel to the authorities at Washington. In the event of your being compelled to resort to the Indian mode of obtaining satisfaction it is to be hoped you will not wage an indiscriminate warfare. If you punish the guilty only, the Indians can have no cause for complaint, neither do I think they will complain. Any communication that may be made to me on this subject I will make Known to you in due time.

O.I.A. Lapointe. D.333.

Hon. Ja’s D. Doty.

New York. 25 March, 1839

Encloses Petition, dated

20 Dec. last, of Michel Nevou & 111

others, Chippewa Half Breeds, to the

President, complaining of the delay

in the payment of the sum granted

them, by Treaty of 29 July, 1837,

protesting against its payments on the

St Croix river, & praying that it be

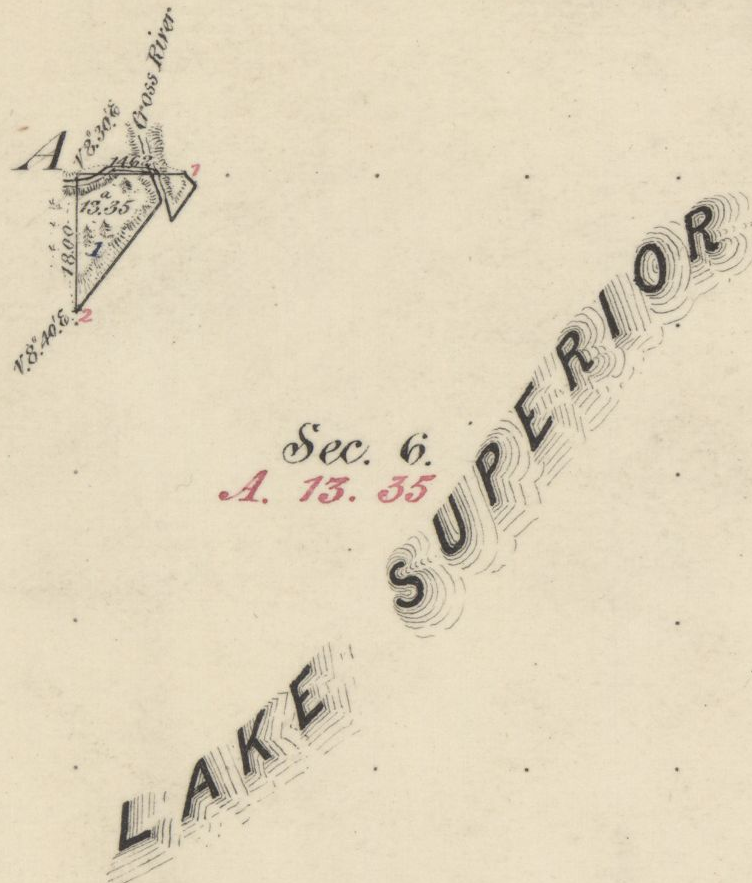

paid at La Pointe on Lake Superior.

Recommends that the payment

be made at this latter place,

for reasons stated.

Rec’d 28 March, 1839.

Ans 29 Mch 1839.

(see over)

Mr Ward

D.100 3 Mch 28

Mch 38, 1839.

Indian Office.

The within may be

an [?] [?] [?] –

[guest?]. in fact will be

in accordance with [?]

[lat?] opinions and not of

the department.

W. Ward

New York

March 25, 1839

The Hon.

J.R. Pointsett

Secy of War

Sir,

I have the honour to submit to you a petition from the Half-breeds of the Chippewa Nation, which has just been received.

It must be obvious to you Sir, that the place from which the Indian Trade is prosecuted in the Country of that Nation is the proper place to collect the Half Breeds to receive their allowance under the Treaty. A very large number being employed by the Traders, if they are required to go to any other spot than La Pointe, they must lose their employment for the season. Three fourths of them visit La Pointe annually, in the course of the Trade. Very few either live or are employed on the St. Croix.

As an act of justice, and of humanity, to them I respectfully recommend that the payment be made to them under the Treaty at La Pointe.

I remain Sir, with very great respect

Your obedient Servant.

J D Doty

[D333-39.LA POINTE]

Hon.

J. D. Doty

March 29, 1839

Recorded in N 26

Page 192

[WD?] OIA

Mch 29, 1839

Sir

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 25th with the Petition of the Chippewa half breeds.

It is only necessary for me to observe his reply that it had been previously determined that the appropriation for them should be distributed at Lapointe, & the instructions with be given accordingly.

Very rcy

Hon.

J.D. Doty

New York

D100

D.333.

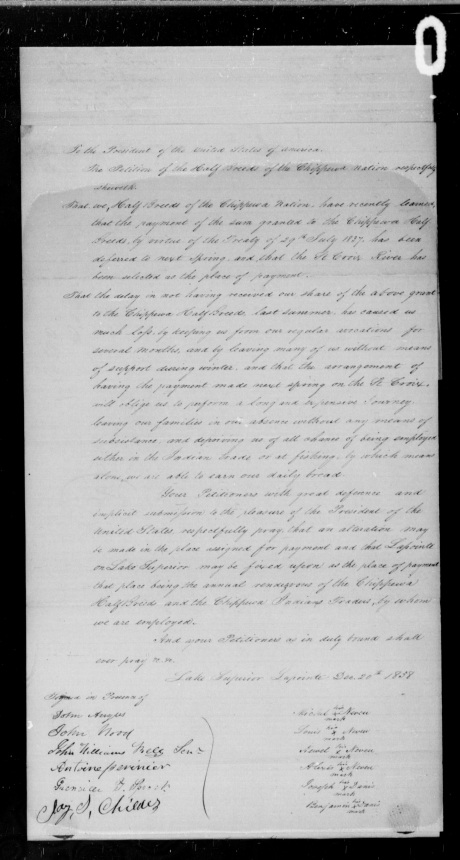

To the President of the United States of America

The Petition of the Half Breeds of the Chippewa nation respectfully shareth.

That we, Half Breeds of the Chippewa Nation, have recently learned, that the payment of the sum granted to the Chippewa Half Breeds, by virtue of the Treaty of 29th July 1837, has been deferred to next Spring, and, that the St Croix River has been selected as the place of payment.

That the delay in not having received our share of the above grant to the Chippewa Half Breeds, last summer, has caused us much loss, by keeping us from our regular vocations for several months, and by leaving many of us without means of support during winter, and that the arrangement of having the payment made next spring on the St Croix, will oblige us to perform a long and expensive Journey, leaving our families in our absence without any means of subsistance, and depriving us of all chance of being employed either in the Indian Trade or at fishing, by which means alone, we are able to earn our daily bread.

Your Petitioners with great deference and implicit submission to the pleasure of the President of the United States, respectfully pray, that an alteration may be made in the place assigned for payment and that Lapointe on Lake Superior may be fixed upon as the place of payment that place being the annual rendezvous of the Chippewa Half Breeds and the Chippewa Indians Traders, by whom we are employed.

And your Petitioners as in duty bound shall ever pray &c. &c.

Lake Superior Lapointe Dec. 20th 1838

Michel Neveu X his mark

Louis Neveu X his mark

Newel Neveu X his mark

Alexis Neveu X his mark

Joseph Danis X his mark

Benjamin Danis X his mark

Jean Bts Landrie Sen’r X his mark

Jean Bts Landrie Jun’r X his mark

Joseph Landrie X his mark

Jean Bts Trotercheau X his mark

George Trotercheau X his mark

Jean Bts Lagarde X his mark

Jean Bts Herbert X his mark

Antoine Benoit X his mark

Joseph Bellaire Sen’r X his mark

Joseph Bellaire Jun’r X his mark

Francois Bellaire X his mark

Vincent Roy X his mark

Jean Bts Roy X his mark

Francois Roy X his mark

Vincent Roy Jun’r X his mark

Joseph Roy X his mark

Simon Sayer X his mark

Joseph Morrison Sen’r X his mark

Joseph Morrison Jun’r X his mark

Geo. H Oakes

William Davenporte X his mark

Robert Davenporte X his mark

Joseph Charette X his mark

Chas Charette X his mark

George Bonga X his mark

Peter Bonga X his mark

Francois Roussain X his mark

Jean Bts Roussain X his mark

Joseph Montreal Maci X his mark

Joseph Montreal Larose X his mark

Paul Beauvier X his mark

Michel Comptories X his mark

Paul Bellanger X his mark

Joseph Roy Sen’r X his mark

John Aitkins X his mark

Alexander Aitkins X his mark

Alexis Bazinet X his mark

Jean Bts Bazinet X his mark

Joseph Bazinet X his mark

Michel Brisette X his mark

Augustin Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Gauthier X his mark

Isaac Ermatinger X his mark

Alexander Chaboillez X his mark

Michel Bousquet X his mark

Louis Bousquet X his mark

Antoine Cournoyer X his mark

Francois Bellanger X his mark

John William Bell, Jun’r

Jean Bts Robidoux X his mark

Robert Morin X his mark

Michel Petit Jun X his mark

Joseph Petit X his mark

Michel Petit Sen’r X his mark

Pierre Forcier X his mark

Jean Bte Rouleaux X his mark

Antoine Cournoyer X his mark

Louis Francois X his mark

Francois Lamoureaux X his mark

Francois Piquette X his mark

Benjamin Rivet X his mark

Robert Fairbanks X his mark

Benjamin Fairbanks X his mark

Antoine Maci X his mark

Joseph Maci X his mark

Edward Maci X his mark

Alexander Maci X his mark

Joseph Montreal Jun. X his mark

Peter Crebassa X his mark

Ambrose Davenporte X his mark

George Fairbanks X his mark

Francois Lemieux X his mark

Pierre Lemieux X his mark

Jean Bte Lemieux X his mark

Baptist St. Jean X his mark

Francis St Jean X his mark

Francis Decoteau X his mark

Jean Bte Brisette X his mark

Henry Brisette X his mark

Charles Brisette X his mark

Jehudah Ermatinger X his mark

Elijah Eramtinger X his mark

Jean Bte Cadotte X his mark

Charles Morrison X his mark

Louis Cournoyer X his mark

Jack Hotley X his mark

John Hotley X his mark

Gabriel Lavierge X his mark

Alexis Brebant X his mark

Eunsice Childes

Etienne St Martin X his mark

Eduard St Arnaud X his mark

Paul Rivet X his mark

Louisan Rivet X his mark

John Fairbanks X his mark

William Fairbanks X his mark

Theodor Borup

James P Scott

Bazil Danis X his mark

Alexander Danis X his mark

Joseph Danis X his mark

Souverain Danis X his mark

Frances Dechonauet

Joseph La Pointe X

Joseph Dafault X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Signed in Presnce of

John Angus

John Wood

John William Bell Sen’r

Antoine Perinier

Grenville T. Sproat

Jay P. Childes

C. La Rose

Chs W. Borup

James P. Scott

Henry Blatchford

1837 Petitions from La Pointe to the President

January 29, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs:

La Pointe Agency 1831-1839

National Archives Identifier: 164009310

O. I. A. La Pointe J171.

Hon Geo. W. Jones

Ho. of Reps. Jany 9, 1838

Transmits petition dated 31st Augt 1837, from Michel Cadotte & 25 other Chip. Half Breeds, praying that the amt to be paid them, under the late Chip. treaty, be distributed at La Pointe, and submitting the names of D. P. Bushnell, Lyman M. Warren, for the appt of Comsr to make the distribution.

Transmits it, that it may receive such attention as will secure the objects of the petitioners, says as the treaty has not been satisfied it may be necessary to bring the subject of the petition before the Comsr Ind Affrs of the Senate.

Recd 10 Jany 1838

file

[?] File.

House of Representatives Jany 9th 1838

Sir

I hasten to transmit the inclosed petition, with the hope, that the subject alluded to, may receive such attention, as to secure the object of the petitioners. As the Chippewa Treaty has not yet been ratified it may be necessary to bring the subject of the petition before the Committee of Indian Affairs of the Senate.

I am very respectfully

Your obt svt

Geo W. Jones

C. A. Harris Esqr

Comssr of Indian Affairs

War Department

To the President of the United States of America

The humble petition of the undersigned Chippewa Half-Breeds citizens of the United Sates, respectfully Shareth:

Bizhiki (Buffalo), Dagwagaane (Two Lodges Meet), and Jechiikwii’o (Snipe, aka Little Buffalo) signed the 1837 Treaty of St Peters for the La Pointe Band.

That, your petitioners having lately heard that a Treaty had been concluded between the Government of the United Sates and the Chippewa Indians at St Peters, for the cession of certain lands belonging to that tribe:

ARTICLE 3.

“The sum of one hundred thousand dollars shall be paid by the United States, to the half-

breeds of the Chippewa nation, under the direction of the President. It is the wish of the

Indians that their two sub-agents Daniel P. Bushnell, and Miles M. Vineyard, superintend

the distribution of this money among their half-breed relations.”

That, the said Chippewa Indians X, having a just regard to the interest and welfare of their Half Breed brethren, did there and then stipulate; that, a certain sum of money should be paid once for all unto the said Half-Breeds, to satisfy all claim they might have on the lands so ceded to the United States.

That, your petitioners are ignorant of the time and place where such payment is to be made.

That the great majority of the Half-Breeds entitled to a distribution of said sum of money, are either residing at La Pointe on Lake Superior, or being for the most part earning their livelihood from the Traders, are consequently congregated during the summer months at the aforesaid place.

Your petitioners humbly solicit their father the President, to take their case into consideration, and not subject them to a long and costly journey in ordering the payments to be made at any inconvenient distance, but on the contrary they trust that in his wisdom he will see the justice of their demand in requiring he will be pleased to order the same to be distributed at Lapointe agreeable to their request.

Your petitioners would also intimate that, although they are fully aware that the Executive will make a judicious choice in the appointment of the Commissioners who will be selected to carry into effect the Provisions of said Treaty, yet, they would humbly submit to the President, that they have full confidence in the integrity of D. P. Bushnell Esqr. resident Indian Agent for the United States at this place and Lyman M Warren Esquire, Merchant.

Your petitioners entertain the flattering hope, that, their petition will not be made in vain, and as in duty bound will ever pray.

La Pointe, Lake Superior,

Territory of Wisconsin 31st August 1837

Michel Cadotte

Michel Bosquet X his mark

Seraphim Lacombe X his mark

Joseph Cadotte X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Chs W Borup for wife & Children

A Morrison for wife & children

Pierre Cotte

Henry Cotte X his mark

Frances Roussan X his mark

James Ermatinger for wife & family

Lyman M Warren for wife & family

Joseph Dufault X his mark

Paul Rivet X his mark for wife & family

Charles Chaboullez wife & family

George D. Cameron

Alixis Corbin

Louis Corbin

Jean Bste Denomme X his mark and family

Ambrose Deragon X his mark and family

Robert Morran X his mark ” “

Jean Bst Couvillon X his mark ” “

Alix Neveu X his mark ” “

Frances Roy X his mark ” “

Alixis Brisbant X his mark ” “

Signed in presence of G. Pauchene

John Livingston

O.I.A. La Pointe W424.

Governor of Wisconsin

Mineral Pt. Feby 19, 1838

Transmits the talk of “Buffalo,” a Chip. Chief, delivered at the La Pointe SubAgt, Dec. 9, 1837, asking that the am. due the half-breeds under the late Treaty, be divided fairly among them, & paid them there, as they will not go to St Peters for it, &c.

Says Buffalo has great influence with his tribe, & is friendly to the whites; his sentiments accord with most of those of the half-breeds & Inds in that part of the country.

File

Recd 13 March 1838

[?] File.

Superintendency of Indian Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point, Feby 19, 1838

Sir,

I have the honor to inclose the talk of “Buffalo,” a principal chief of the Chippewa Indians in the vicinity of La Pointe, delivered on the 9th Dec’r last before Mr Bushnell, sub-agent of the Chippewas at that place. Mr. Bushnell remarks that the speech is given with as strict an adherence to the letter as the language will admit, and has no doubt the sentiments expressed by this Chief accord with those of most of the half-breeds and Indians in that place of the Country. The “Buffalo” is a man of great influence among his tribe, and very friendly to the whites.

Very respectfully,

Your obed’t sevt.

Henry Dodge

Supt Ind Affs

Hon C. A. Harris

Com. of Ind. Affairs

Subagency

Lapointe Dec 10 1837

Speech of the Buffalo principal Chief at Lapointe

Father I told you yesterday I would have something to say to you today. What I say to you now I want you to write down, and send it to the Great American Chief that we saw at St Peters last summer, (Gov. Dodge). Yesterday, I called all the Indians together, and have brought them here to hear what I say; I speak the words of all.

ARTICLE 1.

“The said Chippewa nation cede to the United States all that tract of country included

within the following boundaries:

[…]

thence to and along the dividing ridge between the waters of Lake Superior and those of the Mississippi

[…]“

Father it was not my voice, that sold the country last summer. The land was not mine; it belonged to the Indians beyond the mountains. When our Great Father told us at St Peters that it was only the country beyond the mountains that he wanted I was glad. I have nothing to say about the Treaty, good, or bad, because the country was not mine; but when it comes my time I shall know how to act. If the Americans want my land, I shall know what to say. I did not like to stand in the road of the Indians at St Peters. I listened to our Great Father’s words, & said them in my heart. I have not forgotten them. The Indians acted like children; they tried to cheat each other and got cheated themselves. When it comes my time to sell my land, I do not think I shall give it up as they did.

What I say about the payment I do not say on my own account; for myself I do not care; I have always been poor, & don’t want silver now. But I speak for the poor half breeds.

There are a great many of them; more than would fill your house; some of them are very poor They cannot go to St Peters for their money. Our Great Father told us at St Peters, that you would divide the money, among the half breeds. You must not mind those that are far off, but divide it fairly, and give the poor women and children a good share.

Father the Indians all say they will not go to St Peters for their money. Let them divide it in this parts if they choose, but one must have ones here. You must not think you see all your children here; there are so many of them, that when the money and goods are divided, there will not be more than half a Dollar and a breech cloth for each one. At Red Cedar Lake the English Trader (W. Aitken) told the Indians they would not have more than a breech cloth; this set them to thinking. They immediately held a council & their Indian that had the paper (The Treaty) said he would not keep it, and would send it back.

It will not be my place to come in among the first when the money is paid. If the Indians that own the land call me in I shall come in with pleasure.

ARTICLE 4.

“The sum of seventy thousand dollars shall be applied to the payment, by the United States, of certain claims against the Indians; of which amount twenty eight thousand dollars shall, at their request, be paid to William A. Aitkin, twenty five thousand to Lyman M. Warren, and the balance applied to the liquidation of other just demands against them—which they acknowledge to be the case with regard to that presented by Hercules L. Dousman, for the sum of five thousand dollars; and they request that it be paid.“

We are afraid of one Trader. When at St Peters I saw that they worked out only for themselves. They have deceived us often. Our Great Father told us he would pay our old debts. I thought they should be struck off, but we have to pay them. When I heard our debts would be paid, it done my heart good. I was glad; but when I got back here my joy was gone. When our money comes here, I hope our Traders will keep away, and let us arrange our own business, with the officers that the President sends here.

Father I speak for my people, not for myself. I am an old man. My fire is almost out – there is but little smoke. When I set in my wigwam & smoke my pipe, I think of what has past and what is to come, and it makes my heart shake. When business comes before us we will try and act like chiefs. If any thing is to be done, it had better be done straight. The Indians are not like white people; they act very often like children. We have always been good friends to the whites, and we want to remain so. We do not [even?] go to war with our enemies, the Sioux; I tell my young men to keep quiet.

Father I heard the words of our Great Father (Gov. Dodge) last summer, and was pleased; I have not forgotten what he said. I have his words up in my heart. I want you to tell him to keep good courage for us, we want him to do all he can for us. What I have said you have written down; I [?] you to hand him a copy; we don’t know your ways. If I [?] said any thing [?] dont send it. If you think of any thing I ought to say send it. I have always listened to the white men.

O.I.A. Lapointe, B.458

D. P. Bushnell

Lapointe, March 8, 1838

At the request of some of the petitioners, encloses a petition dated 7 March 1838, addressed to the Prest, signed by 167 Chip. half breeds, praying that the amt stipulated by the late Chip. Treaty to be paid to the half breeds, to satisfy all claims they ma have on the lands ceded by this Treaty, may be distributed at Lapointe.

Hopes their request will be complied with; & thinks their annuity should likewise be paid at Lapointe.

File

Recd 2nd May, 1838

Subagency

Lapointe Mch 6 1838

Sir

I have the honor herewith to enclose a petition addressed to the President of the United States, handed to me with a request by several of the petitioners that I would forward it. The justice of the demand of these poor people is so obvious to any one acquainted with their circumstances, that I cannot omit this occasion to second it, and to express a sincere hope that it will be complied with. Indeed, if the convenience and wishes of the Indians are consulted, and as the sum they receive for their country is so small, these should, I conciev, be principle considerations, their annuity will likewise as paid here; for it is a point more convenient of access for the different bands, that almost any other in their own country, and one moreover, where they have interests been in the habit of assembling in the summer months.

I am sir, with great respect,

your most obt servant,

D. P. Bushnell

O. I. A.

C. A. Harris Esqr.

Comr Ind. Affs

To the President of the United States of America

The humble petition of the undersigned Chippewa Half-Breeds citizens of the United States respectfully shareth

That your petitioners having lately heard, that a Treaty has been concluded between the Government of the United States and the Chippewa Indians at St Peters for the cession of certain lands belonging to that tribe;

That the said Chippewa Indians having a just regard to the interest and wellfare of their Half-Breed brethern, did there and then stipulate, that a certain sum of money should be paid once for all unto the said Half-Breeds, to satisfy all claims, they might have on the lands so ceded to the United States;

That your petitioners are ignorant of the time and place, where such payment is to be made; and

That the great majority of the Half-Breeds entitled to a portion of said sum of money are either residing at Lapointe on Lake Superior, or being for the most part earning their livelihood from the Traders, are consequently congregated during the summer months at the aforesaid place;

Your petitioners therefore humbly solicit their Father the President to take their case into consideration, and not subject them to a long and costly journey on ordering the payment to be made at any convenient distance, but on the contrary, they wish, that in his wisdom he will see the justice of this petition and that he will be pleased to order the same to be distributed at Lapointe agreeably to their request.

Your petitioners entertain the flattering hope, that their petition will not be made in vain and as in duly bound will ever pray.

Half Breeds of Folleavoine Lapointe Lac Court Oreilles and Lac du Flambeau

Georg Warren

Edward Warren

William Warren

Truman A Warren

Mary Warren

Michel Cadott

Joseph Cadotte

Joseph Dufault

Frances Piquette X his mark

Michel Bousquet X his mark

Baptiste Bousquet X his mark

Jos Piquette X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Cadotte X his mark

Seraphim Lacombre X his mark

Angelique Larose X her mark

Benjamin Cadotte X his mark

J Bte Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Danis X his mark

Henry Brisette X his mark

Charles Brisette X his mark

Jehudah Ermatinger

William Ermatinger

Charlotte Ermatinger

Larence Ermatinger

Theodore Borup

Sophia Borup

Elisabeth Borup

Jean Bte Duchene X his mark

Agathe Cadotte X her mark

Mary Cadotte X her mark

Charles Cadotte X his mark

Louis Nolin _ his mark

Frances Baillerge X his mark

Joseph Marchand X his mark

Louis Dubay X his mark

Alexis Corbin X his mark

Augustus Goslin X his mark

George Cameron X his mark

Sophia Dufault X her mark

Augt Cadotte No 2 X his mark

Jos Mace _ his mark

Frances Lamoureau X his mark

Charles Morrison

Charlotte L. Morrison

Mary A Morrison

Margerike Morrison

Jane Morrison

Julie Dufault X her mark

Michel Dufault X his mark

Jean Bte Denomme X his mark

Michel Deragon X his mark

Mary Neveu X her mark

Alexis Neveu X his mark

Michel Neveu X his mark

Josette St Jean X her mark

Baptist St Jean X his mark

Mary Lepessier X her mark

Edward Lepessier X his mark

William Dingley X his mark

Sarah Dingley X her mark

John Hotley X his mark

Jeannette Hotley X her mark

Seraphim Lacombre Jun X his mark

Angelique Lacombre X her mark

Felicia Brisette X her mark

Frances Houle X his mark

Jean Bte Brunelle X his mark

Jos Gauthier X his mark

Edward Connor X his mark

Henry Blanchford X his mark

Louis Corbin X his mark

Augustin Cadotte X his mark

Frances Gauthier X his mark

Jean Bte Gauthier X his mark

Alexis Carpentier X his mark

Jean Bte Houle X his mark

Frances Lamieux X his mark

Baptiste Lemieux X his mark

Pierre Lamieux X his mark

Michel Morringer X his mark

Frances Dejaddon X his mark

John Morrison X his mark

Eustache Roussain X his mark

Benjn Morin X his mark

Adolphe Nolin X his mark

Half-Breeds of Fond du Lac

John Aitken

Roger Aitken

Matilda Aitken

Harriet Aitken

Nancy Scott

Robert Fairbanks

George Fairbanks

Jean B Landrie

Joseph Larose

Paul Bellanges X his mark

Jack Belcour X his mark

Jean Belcour X his mark

Paul Beauvier X his mark

Frances Belleaire

Michel Comptois X his mark

Joseph Charette X his mark

Chl Charette X his mark

Jos Roussain X his mark

Pierre Roy X his mark

Joseph Roy X his mark

Vincent Roy X his mark

Jack Bonga X his mark

Jos Morrison X his mark

Henry Cotte X his mark

Charles Chaboillez

Roderic Chaboillez

Louison Rivet X his mark

Louis Dufault X his mark

Louison Dufault X his mark

Baptiste Dufault X his mark

Joseph Dufault X his mark

Chs Chaloux X his mark

Jos Chaloux X his mark

Augt Bellanger X his mark

Bapt Bellanger X his mark

Joseph Bellanger X his mark

Ignace Robidoux X his mark

Charles Robidoux X his mark

Mary Robidoux X her mark

Simon Janvier X his mark

Frances Janvier X his mark

Baptiste Janvier X his mark

Frances Roussain X his mark

Therese Rouleau X his mark

Joseph Lavierire X his mark

Susan Lapointe X her mark

Mary Lapointe X her mark

Louis Gordon X his mark

Antoine Gordon X his mark

Jean Bte Goslin X his mark

Nancy Goslin X her mark

Michel Petit X his mark

Jack Petit X his mark

Mary Petit X her mark

Josette Cournoyer X her mark

Angelique Cournoyer X her mark

Susan Cournoyer X her mark

Jean Bte Roy X his mark

Frances Roy X his mark

Baptist Roy X his mark

Therese Roy X her mark

Mary Lavierge X her mark

Toussaint Piquette X his mark

Josette Piquette X her mark

Susan Montreille X her mark

Josiah Bissel X his mark

John Cotte X his mark

Isabelle Cotte X her mark

Angelique Brebant X her mark

Mary Brebant X her mark

Margareth Bell X her mark

Julie Brebant X her mark

Josette Lefebre X her mark

Sophia Roussain X her mark

Joseph Roussain X his mark

Angelique Roussain X her mark

Joseph Bellair X his mark

Catharine McDonald X her mark

Nancy McDonald X her mark

Mary Macdonald X her mark

Louise Landrie X his mark

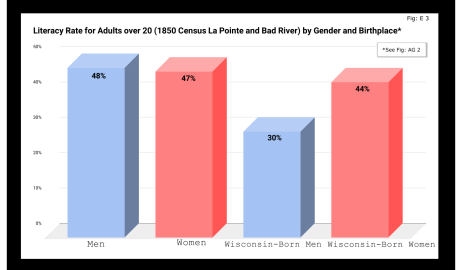

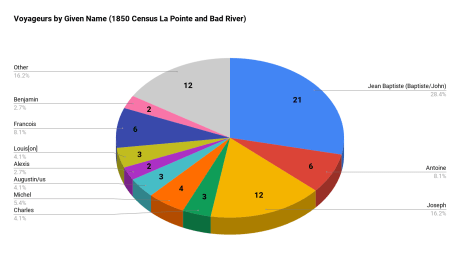

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his