Early Settlement of the Bad River Indian Reservation

March 9, 2016

By Amorin Mello

United States. Works Progress Administration:

Chippewa Indian Historical Project Records 1936-1942

(Northland Micro 5; Micro 532)

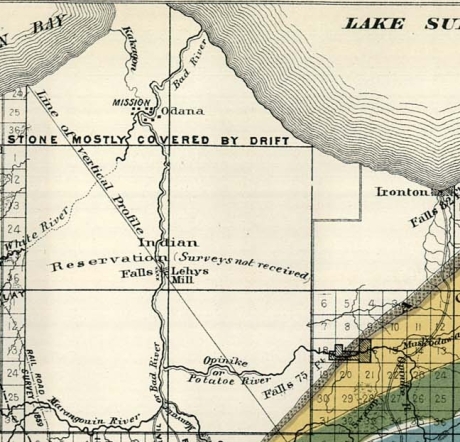

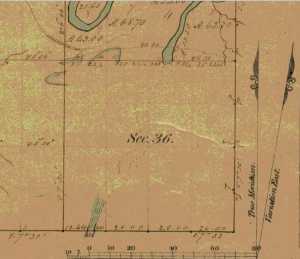

Details of early settlements on the La Pointe Reservation from Charles Whittlesey‘s 1860 Geological Map of the Penokie Range.

Reel 1; Envelope 1; Item 30.

EARLY SETTLEMENT OF THE BAD RIVER INDIAN RESERVATION

by James Scott

The Bad River Indian Reservation was set aside for the use of the Indians in the year 1854. The legal proceedings for this venture were ratified by Congress in 1855. (See Indian Treaty Laws, Chippewa Treaty, 1854, P. 646.)

Many years before the White Man ever came in contact with the Ojibway Indians of Lake Superior, our forefathers inhabited an island now known as Madeline Island, or La Pointe. They were the ancestors of our present Chippewa now located on the Bad River Reservation, and they came to this location by the way of Shau-boo-mi-ni-ka-ning (Gooseberry Landing Point), which is situated at the extreme South of Madeline Island. From there they traveled across to Chi-gee-wa-ne-kung (a long and shallow sandy point). This is the point where the Great Lakes Light House is now situated. The white people call it Chequamegon Point. From Chequamegon Point, the Indians came to this locality by way of the Ka-ka-gon and Bad rivers. The Indians called this location Kie-tig-ga-ning, (Agricultural Paradise). They had good reason for this title, since the ground was fertile, fish were abundant, game plentiful, and invariably there was a good crop of berries and small fruits. In fact, Kie-tig-ga-ning was their home in the warm months. They planted their gardens here.

The original site for the Bad River Village was located west of the present Chicago & North-western Railroad steel bridge crossing the Bad River just a few rods north of the White River.

The first Indian to make a permanent home here was Ba-bom-ni-go-ni-boy (Spreading Eagle). Having selected a suitable location, he built a large wigwam out of elm bark. After completing his home which was situated between what is now Walker’s store and the railroad bridge, he brought his family.

Not long after, more Indian families from Madeline Island, which was the original habitation of the Ojibwas of Lake Superior, moved to Bad River and settled here with Spreading Eagle. Each year more families came, built their wigwams and bark houses and lived along the banks of the Bad River, near where St. Mary’s School is now located. As the population grew, wigwams multiplied, until they extended from the Bad River to the Ka-ka-gon River, and along the south side of what was known as Blackbird’s field. The village grew so rapidly that wigwams and bark houses were built on both sides of the Bad River, and extended about one-half mile above the west side of the White River.

About this time, secret emissaries from the French and English governments came here as fur traders. The Indians surmised that these people might be representatives of some foreign government. They mingled with the Indians; they looked down upon them as an inferior race; consequently the Indians hated the English.

The French, on the other hand, were very friendly with the Indians. They treated them like brothers and even adopted their ways and customs and married the Indian women. They settle d here permanently, and began to build log cabins. It was undoubtedly from them that the Indians learned how to build the log house besides many other useful things. There are a few of these log-cabins still standing that were built by the early French and Indians settlers. But most of them have been remodeled many times, by covering them inside and out with pine lumber, and building additions to them.

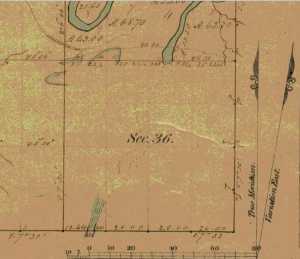

Detail of Nigikoon‘s sawmill and Bad River Falls omitted from Joel Allen Barber’s survey of “The Gardens”.

Several years before the final treaty was signed by the Chippewas of Lake Superior, a strange gentleman appeared in the Indian country: He was a white man and became very well acquainted with some of the Indians His name was Ervin Leihy, but the Indians called him Neg-gi-goons (a young otter). When he saw that the Indians were making their homes on each side of the Bad River, as far up as the Bad River Falls, he too decided to build a little home for himself on the bank at the foot of the Falls. He cleared a small piece of land, built his house and in time erected a saw mill which was run by water power. There he lived for many years cultivating the soil and manufacturing lumber. He was never bothered by any of the Indians because he never gave them any cause for unfriendliness. He associated mostly with the young men of the tribe, learned their language, and spoke it quite fluently. He was soon familiar with Indian ways and habits and adopted many of them.

On September 30, 1854, the final treaty between the Chippewa of Lake Superior and the United States was concluded, (ratified Jan. 10, 1855). The preliminaries required thirty days of deliberation.

Before the last conference, a gentleman by the name of Henry M. Rice, approached the chiefs and headmen of the La Pointe Band at night, and held a secret conference with them. He coached and advised them to be on the alert should a question arise concerning the selection of a reservation.

“I have been secretly approached,” he said, “by a certain band of Chippewa to assist them in securing the land where you have maintained your homes for years. It would be a shame if another band should cheat you out of this place where you have built your homes and lived so long. Any band, or member of such band, which is a part of the Lake Superior Chippewa who reside in the territory you are now ceding to the United States government, have equal rights to make a selection anywhere in the territory the United States is reserving for you.”

When the conference convened the next day, the question of selecting reservations was in order. Immediately after the announcement was made by the official interpreter, Chief Blackbird of the Bad River Band was on his feet shouting and pointing in different directions with a large flat ceremonial pipe which he held in his right hand, describing the boundary lines of his reservation. (See Article 2, paragraph 2, page 648, Chippewa Treaty of 1854).1

As soon as Chief Blackbird arose, Chief Moni-don-se (Small Bug) of the Lac du Flambeau Band, also arose at the same time, and tried hard to discourage Chief Blackbird. Chief Moni-don-se claimed that he was supposed to make the selection that Chief Blackbird was now making. Then both chiefs became angry and exchanged unpleasant words with one another. One of the Government officials intervened. Chief Moni-don-se claimed that his people had as much right to select this land as Chief Blackbird had. Moni-don-se was finally over-ruled, so he had to settle on the Lac du Flambeau Reservation. Chief Blackbird then thanked Mr. Henry M. Rice for his advice and assistance.

![Vincent Roy, Jr., portrait from "Short biographical sketch of Vincent Roy, [Jr.,]" in Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, by Chrysostom Verwyst, 1900, pages 472-476.](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/vincent-roy-jr.jpg?w=219&h=300)

Vincent Roy, Jr. was Henry Mower Rice’s interpreter during the 1854 Treaty with the Chippewas at La Pointe, according to The Sawmill Community at Roy’s Pointe, by Mary Carlson, 2009, page 21.

A few years after the reservations were set aside for the Chippewa people, the construction of more log houses was begun, even being used to bring the timber required for this purpose from the forest. Many new homes were built along the Bad River, the location of the houses extending as far as the Falls. The then existing homes were not lost from view in this movement, and houses needing repairs were given attention. A sub-agent was appointed and placed in charge of the Bad River Reservation, whose duty it was to assist the Indians in agricultural pursuits, as well as guide and advise them in matters concerning such pursuits. None was known as the Government Farmer.

The Indians always took the responsibility and care of his children quite seriously. He taught them early the rudiments of the hunt and the trapping of wild game. He instilled into them from infancy a love of the traditions and customs of their forefathers; he brought before their young minds the organization of the tribe and clans and their duties. He also taught them early in life to be grateful to the Great Spirit and appreciate his many gifts.

Sunday, 21 Apr. 1918

“ASHLAND, Wis., April 20. – Chief Adam Scott, of the Chippewa tribe of Indians is dead. He passed away at his home in Odanah after a short illness of pneumonia at the age of 76 and was buried today.

Chief Scott was one of the head chiefs of the Chippewas since the death of his father who was a head chief of the Chippewa tribe when they were uncivilized. His father was Ka-ta-wa-ba-bay Scott and he lived to see his tribe emerge from a savage state to civilization. His son has been one of the chief advisors of the tribe and has made many trips to Washington on tribal business. Chief Adam Scott leaves one son who becomes chief. Chief Scott was born on Madeline Island and has lived either at Madeline Island or on the Bad River reservation all his life.”

Gic-he-chi-gie-nig Cah-dub-wah-be-da Scott, my father, who died at the age of seventy-six years and ten months, (born June 12, 1840; died April 16, 1916, told me the following:

Kiskitawag (Giishkitawag: “Cut Ear”) signed multiple treaties as a warrior of the Ontonagon Band but afterwards was associated with the Bad River Band. Photograph circa 1880.

~ C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections

About four years after the signing of the Treaty of 1854, in the spring of 1858, Chief Keesh-ke-tow-wug (Cut Ear), one of the signers of the treaty, sent invitations through his runner, George Cedar Root (Ke-ka-geese, meaning young Raven) to tell all the people he could contact, to come to his home on a certain day. He had his wife and daughters prepare a great feast and opened up a large Mo-kuk (birch bark container for maple sugar) of maple sugar. About a hundred people ate at his feast that day.

Chief Keesh-ke-tow-wug ordered his runner to light his personal ceremonial pipe and pass it to each of his male guests. After the pipe ceremony he arose in a very dignified manner. He was a tall, lanky old gentleman, and when standing erect was over six feet tall. He said:

“My children, I want you to listen to me. The proposition I am about to present will benefit all of you, and I need your cooperation. I would like to have you donate your labor to clear land for a large community garden, where every family, or any one who wishes can plant. The place I would suggest is that swampy flat, near the cemetery. It will take time to drain it and dry out but I know it will make good garden plats.”

The people approved of the idea and gave him the assurance that they would cooperate with him to carry out his plans. The old chief was more than pleased. he designated a date on which to start.

When they started clearing the ground for this purpose, many things had to be done. The land was covered with willows and scrubby tamarack and water. Long ditches had to be dug to furnish adequate drainage into both rivers, the Ka-ka-gon and the Bad. It was not long before a tract of land of about eighty acres was prepared for the plow and under actual cultivation.

This community garden extended from Mrs. Armstrong’s dwelling on the U. S. Highway No. 2 to where the steel and concrete bridge now crosses the Bad River on the east; and north-west to Waish-ki Martin’s house. This old community clearing is now known as the “Blackbird Field.” The Indians used this ground for their gardens about twenty-five years.

Detail of Chief James Blackbird from an 1899 photo by De Lancey Gill.

~ Smithsonian Collections

In the years 1888 to 1890, Gic-caw-kie-yesh-sheese (Minor Surface Wind), son of the old chief Ma-ca-day-pe-nay-se (Blackbird), filed on this community clearing as his allotment. He was later known as Chief James Blackbird. The selection was approved by the Indian Department and a patent issued, covering the greater portion of the community garden, in the name of James Blackbird. (see Article 3, granting of allotments, in the Chippewa Treaty of 1854, page 649).1

Under the stipulations of the Treaty of 1854, the chiefs with the assistance of a field Indian Agent constituted an allotment committee, who made membership rolls and gave allotments to those who were recognized as members of the Bad River band. Tracts of eighty acres of land were allotted to each.

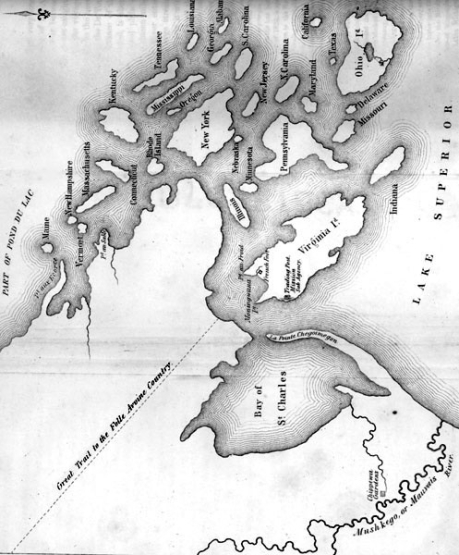

The Cass-Schoolcraft Expedition identified “Chippewa Gardens” at the location of Odanah. This map is several decades older than Kiskitawag‘s proposal to pursue agriculture at the same location.

~ Narrative journal of travels from Detroit northwest through the great chain of American lakes to the sources of the Mississippi River in the year 1820, by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, page 105.

First Sawmills on the Bad River Reservation

March 5, 2016

By Amorin Mello

United States. Works Progress Administration:

Chippewa Indian Historical Project Records 1936-1942

(Northland Micro 5; Micro 532)

Abstract

“Records of a WPA project to collect Chippewa Indian folklore sponsored by the Great Lakes Indian Agency and directed by Sister M. Macaria Murphy of St. Mary’s Indian School, Odanah, Wisconsin. Included are narrative and statistical reports, interview outlines, and operational records; and essays concerning Chippewa religious beliefs and rituals, food, liquor, transportation, trade, clothing, games and dances, and history. Also includes copies of materials from the John A. Bardon collection concerning the Superior, Wisconsin region, La Pointe baptismal records, the family tree of Qui-ka-ba-no-kwe, and artwork of Peter Whitebird.”

Reel 1; Envelope 8; Item 4.

FIRST SAWMILLS ON THE BAD RIVER RESERVATION

By Jerome Arbuckle

Detail of Ervin Leihy’s sawmill at Bad River Falls omitted by the General Land Office.

– Ervin Leihy, one of the first white settlers to come to the northern part of Wisconsin died at his home in this city last week. He was born in Oswego county, N. Y., October 12, 1822. His early life was passed on a farm and at 18 moved to Illinois. Later he bought a farm at Bad River, Ashland county, and in 1846 moved onto it. In 1870 he moved to Bayfield, built his present home and opened a general store which he conducted for a number of years. While living at Bad River he was a member of the town and county boards of Ashland county for a number of years and in 1871 and 1872 was a member of the town board of Bayfield. Besides these he held numerous other offices. He was a public-spirited man, had plenty of means and was always ready to assist in anything that would tend to advance the interests of the town in which he resided.”

~ Wisconsin Weekly Advocate, June 6, 1901.

The first sawmill on the Bad River Reservation was operated by a Mr. Leihy at the rapids of Bad River, which is approximately fifteen miles from the village of Odanah. The power was furnished by a paddle-wheel which was propelled by the force of the stream. The saw was of the old vertical style. With these rude methods, the sawing of six to ten logs into lumber was considered a good daily average. Mr. Leihy was known to the Indians as “Nig-gig-goons” or “Little Otter”. He married a woman of Indian blood, and he apparently enjoyed great favor among the Indians of this region.

The lumber was placed on rafts made of large cedar logs and guided down Bad River when the conditions for such a venture were favorable. A long oar or sculler was used in the stern to assist in propelling the raft and to act as a rudder.

From the mouth of Bad River the raft emerged into Lake Superior provided the wind conditions were favorable, then along the shore line to Chequamegon point and thence across to Madeline Island. The channel between the point and the island was considerably narrower at the time than it is at the present. The lumber thus landed was carried to other points on the Lake by sailboats.

Detail of Albert “Wabi-gog” McEwen‘s sawmill on the White River omitted by the General Land Office.

According to the oldest residents of Odanah, another sawmill was located some distance up the White River. This mill was operated by a man known to the Chippewa as “Wabi-gog” or “The White Porcupine.” This mill was operated practically the same as the Leihy mill. The lumber was also rafted down White River to the confluence with Bad River, thence to Lake Superior and to Madeline Island. During the winter the lumber from this mill was hauled on sleighs by oxen to what is now the city of Ashland.

Read about Benjamin Armstrong’s investigation of Wabi-gog‘s supposed murder in Poor McEwen.

“Wabi-gog” was in the habit of making trips on foot to St. Paul, where he purchased the necessaries for his project. He used a trail that intersected what was known as the “Military Road” which led to St. Paul.

On one of these trips he failed to arrive at his destination and no trace of him was ever found. It was surmised that he had been waylaid and murdered, as he usually carried a considerable sum of money on his person.

Detail of the La Pointe Indian Reservation from Charles Whittlesey‘s 1860 “Geological Map of the Penokie Range“ from Geology of Wisconsin, Volume III, plate XX-214: “Lehys Mill” is identified at the Falls on the “Mauvaise or Bad River”. The White River was partly surveyed upstream from the Mission at “Odana”, up to Albert “Wabi-gog” McEwen‘s sawmill, but did not identify it. Whittlesey may have had a copy of Joel Allen Barber’s missing 1856 survey of The Gardens at Odanah.

By Leo Filipczak

When we last checked in with Joseph Austrian, or Doodooshaaboo (milk) as he was known in these parts, we saw some interesting stories and insights about La Pointe in 1851. The later La Pointe stories, however, are where the really good stuff is.

Austrian’s brief stay on the island came at arguably one of the most important periods in our area’s history, spanning from a few months after the Sandy Lake Tragedy, until just after Chief Buffalo’s return from Washington D.C. Whether young Joseph realized it or not, he recorded some valuable history. In his memoir, we see information about white settlement and land speculation prior to the Treaty of 1854, as well as corroborating accounts of the La Pointe and Bayfield stories found in the works of Carl Scherzer and Benjamin Armstrong.

Most importantly, there is a dramatic scene of a showdown between the Lake Superior chiefs and Agent John Watrous, one of the architects of the Sandy Lake removal. In this, we are privileged to read the most direct and succinct condemnation of the government, I’ve ever seen from Chief Buffalo. It is a statement that probably deserves to be memorialized alongside Flat Mouth’s scathing letter to Governor Ramsey.

So, without further ado, here is the second and final installment of Joseph Austrian’s memoirs of La Pointe, and fifth of this series. Enjoy:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Memoirs of Doodooshaboo

… continued from La Pointe 1851-1852 (Part 1).

Scherzer, Noted Traveller Pays Us a Visit. 1851.

Carl Scherzer and his companion Moritz Wagner recorded their travels in Reisen in Nordamerkia in der Jahren 1852 und 1853. An e-translation of Chapter 21 appeared in English for the first time this fall on the Chequamegon History website. You can read it here, here, and here. The second installment records his time with Joseph Austrian. From Austrian’s account, it appears Wagner did not accompany Scherzer through the Lake Superior country. (Wikimedia Images)

During this summer a noted Austrian traveler Carl Scherzer arrived one Sept. night. He had been commissioned by the “Academy of Science” of Vienna (a Government Institution) to make a tour of America to familiarize himself with the country and gather information to write a book for the Academy. This interesting book which he wrote is called “Scherzer’s Reisen.” Mr. S. sent me a copy of this book which I have in my library. In this book, mention is made of me and my cordial reception of him and his travelling companion, an Attache of the French Legation of Washington who accompanied him on his trip. Scherzer was a highly educated gentleman, cultured and charming, tall and of imposing appearance. Scherzer arrived at La Pointe at midnight coming from Ontonagan 90 miles in a small row boat. To his dismay, he found that there was not a hotel in the place. The boatman told him that he thought that one Austrian might give him shelter for the night, so he came to the house and knocked at the door. Henry Schmitz, my fellow employee, who roomed with me opened the door and called out “Joe step auf freund von below sind da,” whereupon I cordially invited them to enter and made them as comfortable as possible. They remained with us about three days and profoundly appreciated our hospitality. Even making mention of it later on in his book. Once on going to a fishing boat for our supply of fish, Scherzer went with me and begged the privilege of carrying two of the large fine white fish, one suspended from each hand. He much enjoyed meeting the good Father Skolla, his country-mate, also an Austrian, and from him obtained more valuable and authentic information concerning that part of Lake Superior country that he could have otherwise gained. From La Point Scherzer planned to go to St. Paul. There were no railroads here at that time. There were but two roads leading to St. Paul. One was simply a footpath of several hundred miles through the woods. The other led via St. Croix [Brule?] & St. Croix river shortening the foot travel considerably. Scherzer chose the latter road. I fitted out for him, at his request, a birch bark canoe and utensils and all necessary for the trip and Scherzer and his companion started on their way to St. Paul.

He had engaged one “Balange” their voyageur who had brought them from Ontonoagan and a friend of his to take them through. They were well acquainted with the route which at times necessitated their carrying the canoes around through the woods across the portage, where the river was inaccessible through rapids, obstacles and otherwise. Scherzer arrived at St. Paul safely and wrote thanking me for my assistance and requesting me to send him a copy of the wording of a French rowing song (the oarsmen usually sang keeping time with their oars). I sent it to him and received a letter of thanks from New Orleans whence he had gone from St. Paul by steamer via the Mississippi River. This song is embodied in his book also.

A Steamer was a rare occurrence at La Point and when one did come, we often got up an Indian war dance or other Indian exhibit for the amusement of its passengers, and which they enjoyed greatly. In the fall of the year steamers were sometimes driven there by the storms prevailing on the lakes, as the harbor offered the best of shelter. We kept a good supply of cord wood on the dock which we sold to the steamers when they needed fuel.

Indians Decline to be Removed by Gov. I attend Grand Council. 1851.

During the first summer of my stay at La Point, the Indian Agent, Mr. Watrous was directed by the Secretary of the Indian Dept. at Washington to summon the chiefs of that part of the Chippewa tribe residing in the vicinity of Bad River, Bayfield, & Red River for a council. The Agent accordingly sent runners around to the chiefs of the different lodges some of which were quite remote, summoning them to meet him on a certain day at La Point. They came in obedience to the summons many bringing their squaws, papooses and their Indians of their lodges with them. Near the lake shore the put up their wigwams, which were made of birch bark leaving an opening over hung with a blanket which served as a doorway. It made an interesting Indian settlement. The meeting was held on the appointed day, in my brother’s store which was a long wooden structure. When the meeting opened the chiefs sat on the floor arranged along the left side of the room, with their blankets wrapped around them, and each one smoking a long stemmed pipe, which they make themselves, the sign of peace, many ornamented with paint and feathers. On the other side of the room was seated the Indian Agent with an interpreter who translated what either had said.

I naturally felt greatly interested in witnessing their proceedings. The President of the U. S. was known by the Indians as the Great Father and the Agent addressed them telling them what the Great Father wanted of them; namely that they remove from their reservations to interior points in order to make room for while settlers; pointing out to them that the proposed location was more suited for them, there being good fishing and hunting grounds. The government offered to pay them besides certain annuities, partly in money and partly in Indian goods–such as blankets, cotton, beads, provisions, etc. The proposition of the Government was met with murmurs of disapproval by the chiefs & Indians present, and Chief Buffalo made a most eloquent and impassioned speech saying,

“Go back to the ‘Great Father’ and tell him to keep the money and his goods. We do not want them but we wish to be left in peace. Tell him we will not move from the land that is our own, that we have always been peaceable and were always happy until the white man came among our people and sold ‘Matchie Mushkiki [majimashkiki (bad medicine)]’ (poison-whiskey) to them.“

(The real name of whiskey in Indian is “Ushkota wawa [ishkodewaaboo]” – fire water).

The Indians did remain and to this day are still occupying the same land. I was present at this meeting and it so impressed me, that although it took place over fifty years ago it is still vivid in my mind. Later on the Government encouraged the same Indians to engage in farming work on the reservation, and furnishing them with implements and seeds for that purpose, and in the course of a few years they had their own little farms on which they raised potatoes and other vegetables easily cultivated. Schools also were established by the Government. One of their large settlements today is on Bad River, and not far from Ashland Wis., known by the name of Odana.

Brother Marx Experience with Indians. 1851 .

Our blind brother Marx Austrian with brother Julius’ assistance at that time, preempted 160 acres of land near Bayfield from La Point, complying with preemption laws. He built a small log house living there with his wife. One night during their first winter in their new house, there was a knock at the door, and when opened they were confronted by a number of Indians, who were evidently under the influence of liquor and who swinging their tomahawks vigorously, making all sorts of threatening demands. An old Indian who knew Marx interceded and enabled him and his wife to escape without injury who thoroughly scared fled panic stricken in the dark about two miles at night, over the ice, on the Bay which was covered with a foot of snow to La Point for safety. The poor woman having the hazardous task of leading her blind husband over this long and difficult road, not to come back again and glad to escape with their lives and thus abandoning their right of preemption. This place was later on platted and is now known as the Bayfield Addition.

My Experience in Lumbering

Brother Julius had a small saw mill operated by water power about two miles back of Bayfield on Pike’s Creek, near which were Pine lands. In the winter I was sent with some woodsmen to look after the cutting and hauling of Pine logs for the mill. These logs were hauled by ox teams to the mill. In the spring I was again sent there to assist in the sawing of these logs into lumber. We lived in a little log hut near by. When the snow melted toward spring time, the creek was high and swollen. One day the force of the waters burst through the dam, carrying it away and the great volume of water rushing down cut a new channel in the bed of which had become a river, and undermining to foundation of our little log house causing it to topple over into it, also carrying away the logs, many of which floated down into Lake Superior and were lost.

Pg. 218-219 (Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892).

In the winter when logging was going on, once I was sent across from La Point with a heavy load of provisions and supplies for the men. This was loaded on a so called “Canadian flat sleigh.” The road on the way to the mill led down a very steep high hill which half way down had a sharp bend and at this curve stood a tree. After having started down the hill, the horse was not strong enough to hold back the load, which got the better of him, and pushed him swiftly down the hill with his hind legs dragging after him wedging him against and partly into the tree with his front legs up in the air. I could not move the heavily laden sleigh with the horse wedged in so tightly I found it impossible to extricate him, and had to go to the mill for assistance. The sled had to be unloaded before we could free the horse. See Armstrong’s book in which mention and illustration is given of this as “Austrian up the tree.” The book is in my library.

Ferrying Oxen Across the Bay in Row Boat.

My brother Julius had also a large tract of meadow land on Bad River, where he had a number of men employed in making hay, in order to gather this hay for stacking, a span of cattle and a wagon were needed to haul it. There being no other means of ferrying them across the bay, one of the large Mackinaw boats of about twenty-five feet keel by six feet beam had to be used to get these over to the other side across a distance of about three miles to the mainland from where they could be driven to the meadow. I was commissioned to attend to this assisted by four competent boatmen, we finally managed with coaxing and skill to get the two big oxen into the boat, standing them crosswise in it. We tied their horns to the opposite side of the boat. The width of the boat was not sufficient to allow them to stand in their natural position which made them restless. The first thing we knew one of the oxen raised his hind leg and stuck it out over the side of the boat into the water, his other leg soon followed and we had aboard an ox half in the boat, with the weight of his body resting on and threatening to capsize the boat. We quickly cut the rope which held his head and he fell backward overboard floundering in the water. Little did I think that we would see the ox alive again. Imagine my surprise on my return to the Island to find he had swam back to shore safe and sound. When the other ox saw his mate go overboard, he tried to follow and it required much coaxing and extra feeding to restrain him and finally landed him all right on the opposite shore.

Lost in the Woods

I returned to the Island and the next morning I started for the meadow fields in a birch bark canoe with a Mr. Lehigh who had a little saw mill about five miles up Bad River. We were obliged to sit in the bottom of the little boat in a most uncomfortable and cramped position, having been warned by the boatman in charge not to move as the least motion is apt to cause the frail craft to capsize. On arrival at the meadow I found the men busily at work. They were about to take dinner and I gladly consented to join them, and being hungry relished the spread of fried pork, crackers, and tea. My companion Mr. Lehigh was bound for his little saw mill up the river where he lived, and I having business to attend to there started with him on a foot trail through the woods. He loitered on the way picking wild raspberries, just ripe and tempting, but musquitos were thick and vicious and pestered us terribly. I not being accustomed suffered more than my companion. Asking him the distance we were still to go, and on his telling me three miles, I became impatient and went ahead alone to get away from the musquitos. After walking on some time I came to a potato field into which the trail led, but was concealed by the high vines. Crossing the field I struck a trail on the other side and took for granted it was the one leading to the mill. On and on I went when it struck me that I had gone further than the three miles, and it dawned on me that I must have taken the wrong path from the potato field and I concluded to turn back and try to reach the meadow. The sun had gone down, it grew dusk very soon amongst the tall pine and maple trees, in the dense forrest. It grew so dark that I could not see my trail and became entangled in the underbrush and roots of trees, tripping and falling many times. I had with me my double barrel shot gun, both barrels being loaded I shot these off to attract Lehigh’s attention. I listened breathlessly for some answer but there was no sign of a human soul and I became thoroughly frightened at the prospect of being lost in the woods but resolved to make the best of it. I stumbled around and found a log hut near by, which had been put up for temporary use by the Indians in sugar making time. I had neither matches nor ammunition, by feeling around, I discovered that what had been the doorway was closed up with birch bark. By climbing up I also discovered that the roof had been taken off the hut and I let myself down to see what might be inside. I found there three rolls of birch bark and a rude bench made of rough poles laid along on one side lengthwise about a foot along the floor, which served as seats for the Indians while boiling the maple sap. Being tired out I laid down on the rough bench and tried to rest, tying a handkerchief over my face, and with each hand up in the boot sleeves to protect myself from large and ravenous musquitos which tortured me nigh to desperation. Having no matches with me to kindle a fire or create a smoke I was entirely at their mercy. Presently I heard a noise on the outside as though of something stealthily climbing over the wall. The moon was then shining brightly, the sky was clear and on looking up I saw the outlines of a young bear sticking his head over the wall looking down on me. I sprang up and as I did so the bear jumped back and ran off. No doubt the odor of the sugar attracted him more than I did. Under these circumstances rest was out of the question. I climbed out of the hut and made another attempt to find the lost trail by moonlight, crawling on hands and feet in some places. In doing so, I placed my gun against a tree and had a hard time to find it again. I decided there was no use to trip further and climbed back in the hut to stay there till day-light, then with renewed effort after repeated disappointment I finally struck a trail, but at this point I was confused and at a loss to know which direction to take. I reached a steep hill that I did not remember having passed the day before. As a last resort I ran up this hill and hallowed & yelled. An answer came from the valley, from me working there. Following the sound I reached the meadow. My face was so swollen from the musquito bites that I was a sight to behold. After resting and partaking of some food, I again started out for Lehigh’s place one of the me volunteering to show me the way and I arrived there a couple of hours after, and found that it was only one mile from the potato field where I had lost the trail.

For many miles in all other directions in this dense forrest there was not a single habitation nor likelihood of meeting with a soul and here a short time ago a man had been lost and never heard from again. Hence I was lucky indeed to have found my way out of the woods. Lehigh cooly informed me that when I saw him that he heard the report of my gun, but had paid no heed to it thinking I would eventually turn up.

Lost on the Ice and Night

One time during the winter Brother Julius sent me with his trusted Frenchman Alexis, to look up certain Indians who owed him for goods and whom he thought would have considerable fur. This tramp meant about ten miles each way through the woods on an Indian trail the ground being covered with snow. Taking our faithful dog, who had been trained to hauling with the little toboggan sled, on which to bring back the fur which he hoped to get in payment for our debt. We started from La Point, and I met with good success gathering quite a little fur. On our return we reached the Bay shore late in the evening from where we had four or five miles to cross on the ice in order to reach the Island. We rested for about an hour at an Indian wigwam and partook of some tea (such as it was) that the Indian squaw made for us and then started on. Alexis, acting as pilot went ahead, followed by the dog & then by me. It was a clear cold night the moon shown brightly, but about half an hour afterwards snow clouds sprang up shutting out the moonlight, Still we pushed ahead. Soon however Alexis lost his bearings and was uncertain as to direction, but on we went for several hours without reaching the Island. Presently we encountered ice roughly broken and piled high by the force of a gale from the open lake, which indicated that we were too near the open water and that we had gone too far around the Island instead of the straight for La Point. We stumbled along, and after having been out about two hours on the ice, with continued walking we managed to reach the shore and with guidance of Alexis tramped along toward La Point reaching there two hours afterwards almost exhausted by the hardships we had endured.

Trip to Ontonagon in Row Boat for Winter Supplies. 1851

It was in 1851 when brother Julius expected the last boat of the season would touch at La Point which was usually the case and deliver all his supplies but the quantity was not sufficient to induce the Captain to run in there and consequently he skipped La Pointe, thus leaving us short of necessary provisions for the winter, hence it was necessary to procure the same as best we could. I was commissioned by my brother Julius to undertake the job which I did by manning a mackinaw boat with five voyageurs. The boat was loaded with as many barrels of fish as we could carry. We started for Ontonagon about the middle of November, intending to trade the fish for supplies required. It was cold, the ground frozen and covered with snow. The wind was fair. We hoisted our two sails and made good time reaching Montreal River late in the evening where we ran in and tied up for the night. We had no tent with us but found a deserted log house by the river in which we spent the night. There was a large open fire place, and my man cutting down a dry tree kindled a brisk wood fire in the fire place. I slipped into a rough bunk in the room wrapped myself in my blankets and tried to sleep, but in vain. The smoke from the fire was so dense it nearly suffocated me. My met lighting a few tallow candles amused themselves playing cards until late at night.

The next morning early, we set sail and again had fair wind, reaching Iron River about noon and Ontonagon that night, next day succeeded in exchanging my fish for provisions and the following day started on our return trip to La Point. We had mostly fair wind and reached there on the third day in good shape.

Another Trip to Ontonagon for Provisions. 1852.

The following year, in 1852, I agains made a similar trip for like reasons but did not have nearly as good luck as on the previous trip. It was fraught with some danger and combined with a great deal of hardship. The distance from La Point to Ontonagon is nearly 100 miles, all exposed to the storms of Lake Superior which in the Fall are generally very severe. On our first day out we encountered a severe snow storm, which compelled us to make a landing near the mouth of Bad River to save the boat, which was threatened to be dashed to pieces on the shore or carried out into the open lake. So she had to be beached and in order to do this her cargo of fish had all to be thrown overboard when we touched the beach, to lighten her and when this was done she was hauled up on the beach with a block and tackle and fastened to stump of a tree. The boatmen had to go almost waist deep in the water and roll the heavy barrels up on the beach. After completing the landing we sought shelter in the nearby woods from the raging storm, we were not equipped for camping, so we took the sail from the boat and stretched it over as far as it would reach for our own protection. As before the men cut down a dead tree kindled a fire, hanging over it our camp kettle, made tea, tried some pork and this together with some crackers with which we were supplied composed our supper. To get further away from the wind and snow we had gone further back into the woods to find some protection and there we rolled ourselves in our grey blankets and laid down keeping our faces under the protection of the sail as much as possible. Being very much exhausted, we fell asleep, in spite of unfavorable conditions. Toward morning when I awoke I tried to pull my blanket over me a little more but found I could not move it, and discovered that the snow had drifted over us to such an extent that we were fairly buried in it, nothing visible but part of our faces, our breath having kept that free for the time. After daybreak we again started a fire, and this made things worse as the heat melted the snow on the trees around and water dripped down on our blankets, getting them wet. We had to hang them near the fire to dry as we collected them later on. They fairly steamed and we were delayed a whole day in getting arrangements completed to start again on our trip. Toward morning the wind had subsided considerably, and the snow storm had abated somewhat and again we ventured on our trip. After going through the same routine of reloading as on our previous occasion. At 10 A.m. we started on our perilous voyage making good head way, the wind being favorable. We reached Iron River after midnight. We detected an Indian wigwam near by, thinking we might be able to get something to eat. We tied up and investigated. We peeped into the wigwam and found the same occupied with an Indian family. The Indian squaw and papooses all tight asleep. Not wishing to arouse them or to lose further time we moved on stopping early the next morning in a small bay on our route. Kindling a fire as previously described, preparing a meager breakfast , the best scant supplies would permit. These boatmen were accustomed to cooking (such as it was) as well as boating it being often a necessity, as they were accustomed to make long coasting trips in the pioneer days of the Lake Superior regions, which was sparsely settled and vessels were very scarce. Supplies and all merchandise had to be transported all the way from Detroit to Lake Superior on those small Mackinaw boats. After breakfast we set sail and continued our journey with fair wind enabling us to make good time, but it had grown bitterly cold and as we were but poorly protected for such severe weather. It cost us untold suffering.

We finally reached Ontonagon River after dark, and to our great consternation found that the river was frozen over about an inch thick with ice. This was not easy to break through with flimsy craft, but desperation gave strength to our men and they were equal to the situation. With their heavy oars they pounded and broke the ice managing finally to get inside of the river to the dock of the merchant with whom I expected to do my trading in the town of Ontonagon, which was the Lakeport for the Minnesota and other copper mines in that vicinity, at that time being just developed. On the following morning I attended to the selling of the load of fish, purchased our supplies and intending to start back for La Point the next morning.

Ordered to go to Eagle River. 1852.

In the meantime the propeller Napoleon arrived from there bringing for me a letter from brother Julius, instructing me if still in Ontonagon to take this steamer for Eagle River and to enter the employ of Mr. Henry Leopold, who had a small store there. His man had left suddenly and he was anxious for my services. I started for Eagle River just as I was and not until the following spring did I get my trunk. I began working for Mr. Leopold as bookkeeper and general clerk, and thus abruptly terminated my business career at La Point. My boatmen under direction of Mr. Henry Schmitz started without me on their return trip to La Point as planned when between Montreal River and Bad River, they encountered a terrific gale and snow storm. It was so severe that to remain outside meant to be lost, and as a last resort, they ran their boat through the breakers, trying to beach her. She was swamped with all the supplies, and tossed up on the beach and had to be abandoned for the time being. Later on another boat was sent on from La Point to get the damaged cargo. The Napoleon got abreast of Eagle River, this place being on the open shore of Lake Superior without any protection, it being too rough there for the boat to make a landing, therefore she went on to Eagle Harbor, about nine miles distant, where she could safely land. On arrival there I put up at Charley King boarding house for the night.

To be continued after La Pointe 1852-1854…

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Special thanks to Amorin Mello and Joseph Skulan for sharing this document and their important research on the Austrian brothers and their associates with me. It is to their credit that these stories see the light of day. This is the end of the La Pointe section, but the original handwritten memoir of Joseph Austrian is held by the Chicago History Museum and contains many interesting stories from the life of this brief resident of La Pointe.

Sandy Lake Letters: Sherman Hall to the Wheelers

July 11, 2013

“Chippewa Indians Fishing on the Ice” (Digitized by New York Public Library from Heroes and hunters of the West : comprising sketches and adventures of Boone, Kenton, Brady, Logan, Whetzel, Fleehart, Hughes, Johnston, etc. Philadelphia : H. C. Peck & Theo. Bliss, 1859.)

On June 9th, I transcribed and posted two letters related to the Sandy Lake Tragedy (the attempted removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe in the fall of 1850, which claimed as many as 400 innocent lives). The letters, digitized by the Wisconsin Historical Society, were from the Warren Family Papers. One was from missionary Leonard Wheeler to William Warren before the tragedy, and another was from Indian Agent John Watrous to Warren during a second removal attempt a year later.

That post sought to assess how much responsibility Warren and Watrous bear for the 400 deaths. It also touched on the role of the Protestant A.B.C.F.M. missionaries in the region. This post continues those thoughts. This time, we’re looking at two more letters and evaluating one of the missionaries himself.

Both of these letters are from the Wheeler Family Papers, held by the Wisconsin Historical Society at the Ashland Area Research Center. I went directly to the original documents for these, and while I’ve seen them referenced in published works, I believe this is the first time these particular letters have been transcribed or posted online.

The first is from Sherman Hall, the founder of the La Pointe Mission, to his colleague Leonard Wheeler, who operated the satellite mission at Odanah. Hall traveled to Sandy Lake for the annuity payments and sent this letter to Wheeler, who was visiting family back in Massachusetts, after returning to La Pointe.

Lapointe. Dec. 28th 1850

Brother Wheeler:

I wrote you while at Sandy Lake and promised to write again when I should reach Lapointe. That promise I now redeem. I started from Sandy Lake on the fourth inst. and reached home on the 16th having been absent from home just eight weeks. I was never more heartily glad to leave a place than I was Sandy Lake, nor more glad to reach home after an absence. Of course winter here has justly begun. The snow was some ten inches deep on the Savannah Portage. On reaching the East Savannah River we found the ice good and clear of snow and water. This continued to be the case most of the way to the Grand Portage at Fond du Lac. From Fond du Lac to Lapointe the traveling most of the way was hard, and it was not till the seventh day from F. du L. that I reached home. Besides bad traveling I had to carry a pack which I found, when I got home weighed 60 pounds. With this however I found it not difficult to keep up with most of my traveling companions who were much heavier loaded than I. This is my first experience of carrying a heavy pack on a long journey and I am fully satisfied with the experiment. I had no alternative however, bet either to throw away my blankets and clothes, or carry them. Every body was loaded with a heavy pack, and I could employ no one. I however got through well—did not get lame as many others did, nor do I feel any furious[?] by ill effects of my journey since my arrival.

I found the mission family well on my arrival. They had felt somewhat lonesome while so many were absent from this place. Things in the community here are generally in a quiet state at present. I apprehend that there will be considerable pinching for provisions before spring. It has been a very windy and stormy fall. The people have taken but little fish. Many nets have been lost. The traders have but a small quantity of provisions, and if they had the people have but little to buy with. The bay opposite to this island is now principally covered with ice so that the Indians are on the ice some to spear fish. The ice has once broken up since it first closed, and a heavy wind would break it up again, as it is yet very thin, and the weather mild. If the lake is frozen the Inds will probably get considerable fish; but if it should be open they must suffer.

Our Indian meetings are pretty well attended, and I feel that there is ground for encouragement. Simon I think is exerting a good influence. His Catholic friends have tried to draw him back to their church; but seems stable. His oldest brother, who has recently lost his wife, has expressed a wish to hear the word of God. I hope he will yet become a sincere listener.

Our English exercises are attended by a smaller number than formerly since many have left this place. I think however for our own good, as well as on account of others, we ought to keep them up. Mr. Van Tassel has returned to remain here till spring. I have heard nothing from Bad River for some time past. I had formed a design to go there this week, but have been prevented by the state of the ice. I intend going as soon as the ice gets a little stronger. I suppose there are very few Indians there. More are about the Lake.

I heard that Mr. Leihy has lost both his horses which will be a serious inconvenience to him in this mill enterprise I presume.

Mr. Pulsifer has received one letter from you, and by our last mail he heard through his correspondent at Lowell that you had arrived at that place.

I suppose you find some changes have taken place in the wide world during the times you have been shut up in the wilderness. Do you find calls enough to keep you busy? I have been expecting a letter from you. I want to hear what you have to say about the things you see, and how you like visiting, etc.

I have just had a letter from Mr. Ely, who says, “We are [snugly by quarters?] in St. Paul. My home is full of music—am employed as choir leader in Mr. [Mill’s?] (Prs.) church—sing two evenings a week at Stillwater, and the rest of my time is well filled with the private scholars & tuning Pianos, of which there are 7 or 8 at St. Paul.” Perhaps Br. Ely will find this a more lucrative business than cutting and hauling pine logs. I am glad he has found employment.

Our children all attend school except Harriet. Marydoes very well. Please give my regards to your friends at Lowell. I am writing to Mr. Treat by this opportunity. [Wish?] kind regards to Mrs. W. I remain

yours

S. Hall.

The Old Mission Church, La Pointe, Madeline Island. (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: 24827)

The Old Mission Church, La Pointe, Madeline Island. (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: 24827) Harriet Wheeler, pictured about forty years after receiving this letter. (Wisconsin Historical Society: Image ID 36771)

Harriet Wheeler, pictured about forty years after receiving this letter. (Wisconsin Historical Society: Image ID 36771)“…your note to Harriet” Harriet Hall was Sherman’s oldest daughter, about 19 years old at this time.

Many Ojibwe leaders, including Hole in the Day, blamed the rotten pork and moldy flour distributed at Sandy Lake for the disease that broke out. The speech in St. Paul is covered on pages 101-109 of Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader, my favorite book about this time period. (Photo from Whitney’s Gallery of St. Paul: Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID 27525)

Many Ojibwe leaders, including Hole in the Day, blamed the rotten pork and moldy flour distributed at Sandy Lake for the disease that broke out. The speech in St. Paul is covered on pages 101-109 of Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader, my favorite book about this time period. (Photo from Whitney’s Gallery of St. Paul: Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID 27525) Mary Warren (1835-1925), was a teenager at the time of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. She is pictured here over seventy years later. Mary, the sister of William Warren, had been living with the Wheelers but stayed with Hall during their trip east. (Photo found on University of Connecticut Radio website, scanned from Frances Densmore photos in the Smithsonian Bureau of Ethnology)

Mary Warren (1835-1925), was a teenager at the time of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. She is pictured here over seventy years later. Mary, the sister of William Warren, had been living with the Wheelers but stayed with Hall during their trip east. (Photo found on University of Connecticut Radio website, scanned from Frances Densmore photos in the Smithsonian Bureau of Ethnology)Lapointe, Feb. 24th 1851.

Mrs. Wheeler,

By our last mail I wrote to Mr Wheeler, and by this I will address a few lines to you. From your note to Harriet I suppose you are happy among your friends. I am glad you are so, and hope you will not only spend your winter pleasantly, but that you will find the present season of relaxation from the severe duties of your station here, the occasion of reconnecting[?] your health and spirits.

I do not feel that the time has yet come when the churches ought to close their efforts to save these Indians. I do not think they are entirely beyond the reach of hope. The prospect however looks dark. But I think the greatest cause of discouragement arises from their character, and not from their present political condition. Generally they do not want to improve their condition. They are satisfied with their ignorance and degradation. All they think of is to supply for their present wants without their own exertions, while they wish to live in idleness and sin. This is the cause of their keeping so much aloof from the influence of the missions. Their minds are dreadfully dark respecting the things of the future world. They seem to have no ideas of happiness superior to that derives from the gratification of the lowest animal appetites and passions. This is the reason why the truths of the gospel so little effect on them. These things present to my mind much stronger grounds of discouragement than their present political difficulties, though those at present are not inconsiderable.

But as stupid as is the conscience, and as dark as is the understanding and the heart, and as much as they are given up to [?]ality and sin, I believe there is a Power that can quicken them into life. My only hope is that He who has made them, and has power to save them, will come and add his blessing to the preaching of his own gospel, and make it to them the power and wisdom of God. Thousands of others as dead in trespasses and sins, have been saved. Why may not they be saved? Come back home and let us try still to do something for them. Tell Christians to remember them and pray for them, that the word of God among them may have free course and be glorified.

It is a time of great scarcity of food among the Indians. There is some one in our houses almost every hour of the day begging for food. Very few get more than a meal a day; many not half of one. I have been told by several individuals, that they have tried three or four days in succession to catch fish, and have been obliged to return to their starving families each night with nothing for them. I am frequently importuned to spare a little provisions till I am obliged to go away out of sight to get rid of their pleading. I have spared the last potatoes I dare let go. Corn we have none. We have but a small quantity of flour over what will be required to sustain our families till we can expect to obtain a new supply. For a long time I have not known fish so scarce as the present winter. That is almost the only dependence of this people. For a month to come there will be many hungry ones. Many of the French and half-breeds are but little better off than the Indians. All we can do is to divide a little morsel with the hungry ones who come to beg. We have not much to give to those who importune for something to carry to their families. But as long as they continue to waste their summers in idleness they must starve in the winter.

The young Hole-in-the-day has been down to St Paul and there made a public speech in which he attributes the sickness at the payment last fall to the bad provisions which were dealt out to the Indians, and imparts much blame to the officers of the government for the way in which they [were with?]. In time they had some flour dealt out to them which was much damaged. But I think there were other causes for the sickness which prevailed besides the bad provisions. I think however that in some [aspects?] the Indians were wronged. Treaty stipulations were not carried out. H is very confident that many of the Indians are not satisfied with the manner in which they have been dealt with, and recent events have not served to strengthen their attachment to the Government.

We had our communion yesterday. I think there is a [?]ably good state of feeling among the native church members at this time. Simon has been frequently sick this winter. But his trials appear to bring nearer to God. He appears to be growing in the knowledge of God and in piety.

You will probably recollect Mo-ko-kun-ens-ish, an Indian with a bunch[?] between his shoulders, married into the family of the Little-current. He is, by profession, a Catholic. About a week ago, he made me a visit, and said his priest had offended him, and he wished to join us. A short time since he lost a child, and when the priest came to bury it, he said he “scolded him” because he had not cleaned away the snow from the gate of the burying yard, and made a better path for him to come to the grave. He told a long story. I suspected his object was to get some provisions of me. I told him we should be happy to see him at our meetings, and told him where and when they would be held. He said he should attend only sometimes he might be obliged to fish to get something to eat, and be occasionally away. I said a few words to him on religious subjects, and he left without asking for anything. The next day he came with a small piece of cloth and asked me to give him provisions for it. I told I had not provisions to trade. He then enquired about meeting. I told him we were to hold one that evening in the school-house. He said he should attend. The evening came, the meeting was held—but he was not there. Nor have we seen him at any other meeting. Such are the methods the heathens & Catholics take to deceive us. We could make many converts with flour and pork, especially at this time.

Yours Truly,

S. Hall

[Written in margins]

All send love though I have not room to write it.

Mary goes to school and is doing very well.

These are the originals of the paragraph about Hole in the Day’s speech in St. Paul. I couldn’t quite decipher all of it. Let me know what you see (Wheeler Family Papers, Personal Correspondence 1851, Wisconsin Historical Society Ashland Area Research Center).

In the June 9th post, we tried to determine how much William Warren and John S. Watrous were at fault for the deaths resulting from the 1850 Sandy Lake removal attempt. In this post, we will do the same for Sherman Hall.

Before we begin, it’s worth reviewing the facts. By 1850, Hall had lived at La Pointe for twenty years. He knew the people who lived here, and he knew the promises the Ojibwe were given at the Treaty of 1842. He was certainly aware of the Ojibwe position on the removal.

Rev. Hall did not order the removal. Compared with the government and Fur Company officials, he was fairly powerless within the Lake Superior region. However, he had a power of a different sort. As the primary voice of the ABCFM in Ojibwe country, he had powerful friends in the eastern states. Many Americans perceived the missionaries as the only neutral voice in the area. Hall admits in the December 28th letter that the Ojibwe were wronged. He could have advocated for their cause in the summer of 1850 as the illegal removal was unfolding. Instead, he largely went along with government efforts.

To his credit, in other letters Hall did blame the government for the failure of the Sandy Lake payment. The best book I’ve encountered about this time period is William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader by Theresa Schenck (Nebraska UP, 2007). On page 94, Dr. Schenck quotes a letter from Hall to ABCFM Secretary S.B. Treat. It is dated December 30, and is probably the letter referred to in the letter to Leonard Wheeler above. Hall is honest about Ojibwe feelings on the removal and seems to empathize somewhat. On page 155, Schenck details how the La Pointe mission did eventually turn against government removal efforts later in 1851.

So, it probably seems that I am defending Sherman Hall. Why? Truthfully, it’s because I want to have some balance in this post because, quite frankly, these two letters are some of the most disgusting, horrifying documents I’ve ever read. I felt especially sick typing up the February 24th letter to Harriet Wheeler. For a man who claimed to be “saving” the Ojibwe to be so heartless in the midst of so much suffering is appalling.

Was the mission running low on food? Sure, but doesn’t true Christian charity demand sharing to the last?

Should Hall’s language be judged by the standards of the racist times he lived in? Absolutely, but to say the things he says about human beings, his neighbors of twenty years, is inexcusable in any time period.

Is it possible he was traumatized by his experience at Sandy Lake, and this was a way of dealing with his personal guilt? This is possible. He does seem to be speaking to himself in the letter as much as he is to the Wheelers.

There is a danger in judging too much from just two letters, but I think Hall needs to be held to the same standard as Warren and Watrous were in the June 9th post. He could have spoken out against the removal to begin with. He didn’t. He was an eyewitness to Sandy Lake. He knew what the Ojibwe had been promised, and he saw the consequences of the government breaking those promises. His letters to the Wheelers in Boston could have been used to help right those wrongs by uniting the missions behind the Ojibwe cause. Instead, he chose to blame the people who had been wronged to the point of 400 deaths. For these reasons, I think when we list the villains of Sandy Lake, the Reverend Sherman Hall needs to be among them.