Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Introduction

May 26, 2013

Click the question mark under the picture to see if it shows Chief Buffalo.

?

?

Buffalo, the 19th-century chief of the La Pointe Ojibwe, is arguably the most locally-famous person in history of the Chequamegon region. He is best known for his 1852 trip to Washington D.C., undertaken when he was thought to be over ninety years old. Buffalo looms large in the written records of the time, and makes many appearances on this website.

He is especially important to the people of Red Cliff. He is the founding father of their small community at the northern tip of Wisconsin in the sense that in the Treaty of 1854, he negotiated for Red Cliff (then called the Buffalo Estate or the Buffalo Bay Reservation) as a separate entity from the main La Pointe Band reservation at Bad River. Buffalo is a direct ancestor to several of the main families of Red Cliff, and many tribal members will proudly tell of how they connect back to him. Finally, Buffaloʼs fight to keep the Ojibwe in Wisconsin, in the face of a government that wanted to move them west, has served as an inspiration to those who try to maintain their cultural traditions and treaty rights. It is unfortunate, then, that through honest mistakes and scholarly carelessness, there is a lot of inaccurate information out there about him.

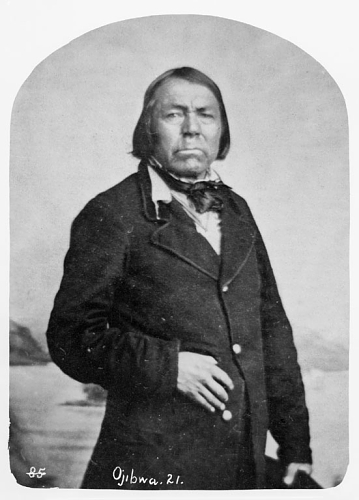

During the early twentieth century, the people of Red Cliff maintained oral traditions about about his life while the written records were largely being forgotten by mainstream historians. However, the 1960s and ʻ70s brought a renewed interest in American Indian history and the written records came back to light. With them came no fewer than seven purported images of Buffalo, some of them vouched for by such prestigious institutions as the State Historical Society of Wisconsin and the U.S. Capitol. These images, ranged from well-known lithographs produced during Buffaloʼs lifetime, to a photograph taken five years after he died, to a symbolic representation of a clan animal originally drawn on birch bark. These images continue to appear connected to Buffalo in both scholarly and mainstream works. However, there is no proof that any of them show the La Pointe chief, and there is clear evidence that several of them do not show him.

The problem this has created is not merely one of mistaken identity in pictures. To reconcile incorrect pictures with ill-fitting facts, multiple authors have attempted to create back stories where none exist, placing Buffalo where he wasnʼt, in order for the pictures to make sense. This spiral of compounding misinformation has begun to obscure the legacy of this important man, and therefore, this study attempts to sort it out.

Bizhikiwag

The confusion over the images stems from the fact that there was more than one Ojibwe leader in the mid-nineteenth century named Bizhiki (Buffalo). Because Ojibwe names are descriptive, and often come from dreams, visions, or life experiences, one can be lead to believe that each name was wholly unique. However, this is not the case. Names were frequently repeated within families or even outside of families. Waabojiig (White Fisher) and Bugone-Giizhig (Hole in the Day) are prominent examples of names from Buffaloʼs lifetime that were given to unrelated men from different villages and clans. Buffalo himself carried two names, neither of which was particularly unique. Whites usually referred to him as Buffalo, Great Buffalo, or LaBoeuf, translations of his name Bizhiki. In Ojibwe, he is just as often recorded by the name Gichi-Weshkii. Weshkii, literally “new one,” was a name often given to firstborn sons in Ojibwe families. Gichi is a prefix meaning “big” or “great,” both of which could be used to describe Buffalo.

Nichols and Nyholm translate Bizhiki (Besheke, Peezhickee, Bezhike, etc.) as both “cow” and “buffalo.” Originally it meant “buffalo” in Ojibwe. As cattle became more common in Ojibwe country, the term expanded to include both animals to the point where the primary meaning of the word today is “cow” in some dialects. These dialects will use Mashkodebizhiki (Prairie Cow) to mean buffalo. However, this term is a more recent addition to the language and was not used by individuals named Buffalo in the mid- nineteenth century. (National Park Service photo)

One glance at the 1837 Treaty of St. Peters shows three Buffalos. Pe-zhe-kins (Bizhikiins) or “Young Buffalo” signed as a warrior from Leech Lake. “Pe-zhe-ke, or the Buffalo” was the first chief to sign from the St. Croix region. Finally, the familiar Buffalo is listed as the first name under those from La Pointe on Lake Superior. It is these two other Buffalos, from St. Croix and Leech Lake, whose faces grace several of the images supposedly showing Buffalo of La Pointe. All three of these men were chiefs, all three were Ojibwe, and all three represented their people in Washington D.C. Because they share a name, their histories have unfortunately been mashed together.

Who were these three men?

Treaty of St. Peters (1837) For more on Dagwagaane (Ta-qua-ga-na), check out the People Index.

The familiar Buffalo was born at La Pointe in the middle of the 18th century. He was a member of the Loon Clan, which had become a chiefly clan under the leadership of his grandfather Andeg-wiiyas (Crowʼs Meat). Although he was already elderly by the time the Lake Superior Ojibwe entered into their treaty relationship with the United States, his skills as an orator were such that by the Treaty of 1854, one year before his death, Buffalo was the most influential leader not only of La Pointe, but of the whole Lake Superior country.

Treaty of St. Peters (1837) For more on Gaa-bimabi (Ka-be-ma-be), check out the People Index.

William Warren, describes the St. Croix Buffalo as a member of the Bear Clan who originally came to the St. Croix from Sault Ste. Marie after committing a murder. He goes on to declare that this Buffaloʼs chieftainship came only as a reward from traders who appreciated his trapping skills. Warren does admit, however, that Buffaloʼs influence grew and surpassed that of the hereditary St. Croix leaders.

Treaty of St. Peters (1837) For more on Flat Mouth, check out the People Index.

The “Young Buffalo,” of the Pillager or Leech Lake Ojibwe of northern Minnesota was a war chief who also belonged to the Bear Clan and was considerably younger than the other two Buffalos (the La Pointe and St. Croix chiefs were about the same age). As Biizhikiins grew into his later adulthood, he was known simply as Bizhiki (Buffalo). His mark on history came largely after the La Pointe Buffaloʼs death, during the politics surrounding the various Ojibwe treaties in Minnesota and in the events surrounding the US-Dakota War of 1862.

The Picture Search

In the coming months, I will devote several posts to analyzing the reported images of Chief Buffalo that I am aware of. The first post on this site can be considered the first in the series. Keep checking back for more.

Sources:

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 21 June 2012. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1995. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers: With Brief Notices of Passing Events, Facts, and Opinions, A.D. 1812 to A.D. 1842. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and, 1851. Print.

Treuer, Anton. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul, MN: Borealis, 2010. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

No Princess Zone: Hanging Cloud, the Ogichidaakwe

May 12, 2013

This image of Aazhawigiizhigokwe (Hanging Cloud) was created 35 years after the battle depicted by Marr and Richards Engraving of Milwaukee for use in Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).

Here is an interesting story I’ve run across a few times. Don’t consider this exhaustive research on the subject, but it’s something I thought was worth putting on here.

In late 1854 and 1855, the talk of northern Wisconsin was a young woman from from the Chippewa River around Rice Lake. Her name was Ah-shaw-way-gee-she-go-qua, which Morse (below) translates as “Hanging Cloud.” Her father was Nenaa’angebi (Beautifying Bird) a chief who the treaties record as part of the Lac Courte Oreilles band. His band’s territory, however, was further down the Chippewa from Lac Courte Oreilles, dangerously close to the territories of the Dakota Sioux. The Ojibwe and Dakota of that region had a long history of intermarriage, but the fallout from the Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1825) led to increased incidents of violence. This, along with increased population pressures combined with hunting territory lost to white settlement, led to an intensification of warfare between the two nations in the mid-18th century.

As you’ll see below, Hanging Cloud gained her fame in battle. She was an ogichidaakwe (warrior). Unfortunately, many sources refer to her as the “Chippewa Princess.” She was not a princess. Her father was not a king. She did not sit in a palace waited on hand and foot. Her marriageability was not her only contribution to her people. Leave the princesses in Europe. Hanging Cloud was an ogichidaakwe. She literally fought and killed to protect her people.

Americans have had a bizarre obsession with the idea of Indian princesses since Pocahontas. Engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe (1616) Wikimedia Images

Americans have had a bizarre obsession with the idea of Indian princesses since Pocahontas. Engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe (1616) Wikimedia ImagesIn An Infinity of Nations, Michael Witgen devotes a chapter to America’s ongoing obsession with the concept of the “Indian Princess.” He traces the phenomenon from Pocahontas down to 21st-century white Americans claiming descent from mythical Cherokee princesses. He has some interesting thoughts about the idea being used to justify the European conquest and dispossession of Native peoples. I’m going to try to stick to history here and not get bogged down in theory, but am going to declare northern Wisconsin a “NO PRINCESS ZONE.”

Ozhaawashkodewekwe, Madeline Cadotte, and Hanging Cloud were remarkable women who played a pivotal role in history. They are not princesses, and to describe them as such does not add to their credit. It detracts from it.

Anyway, rant over, the first account of Hanging Cloud reproduced here comes from Dr. Richard E. Morse of Detroit. He observed the 1855 annuity payment at La Pointe. This was the first payment following the Treaty of 1854, and it was overseen directly by Indian Affairs Commissioner George Manypenny. Morse records speeches of many of the most prominent Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs at the time, records the death of Chief Buffalo in September of that year, and otherwise offers his observations. These were published in 1857 as The Chippewas of Lake Superior in the third volume of the State Historical Society’s Wisconsin Historical Collections. This is most of pages 349 to 354:

“The “Princess”–AH-SHAW-WAY-GEE-SHE-GO-QUA–The Hanging Cloud.

The Chippewa Princess was very conspicuous at the payment. She attracted much notice; her history and character were subjects of general observation and comment, after the bands, to which she was, arrived at La Pointe, more so than any other female who attended the payment.

She was a chivalrous warrior, of tried courage and valor; the only female who was allowed to participate in the dancing circles, war ceremonies, or to march in rank and file, to wear the plumes of the braves. Her feats of fame were not long in being known after she arrived; most persons felt curious to look upon the renowned youthful maiden.

Nenaa’angebi as depicted on the cover of Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).

Nenaa’angebi as depicted on the cover of Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).She is the daughter of Chief NA-NAW-ONG-GA-BE, whose speech, with comments upon himself and bands, we have already given. Of him, who is the gifted orator, the able chieftain, this maiden is the boast of her father, the pride of her tribe. She is about the usual height of females, slim and spare-built, between eighteen and twenty years of age. These people do not keep records, nor dates of their marriages, nor of the birth of their children.

This female is unmarried. No warrior nor brave need presume to win her heart or to gain her hand in marriage, who cannot prove credentials to superior courage and deeds of daring upon the war-path, as well as endurance in the chase. On foot she was conceded the fleetest of her race. Her complexion is rather dark, prominent nose, inclining to the Roman order, eyes rather large and very black, hair the color of coal and glossy, a countenance upon which smiles seemed strangers, an expression that indicated the ne plus ultra of craft and cunning, a face from which, sure enough, a portentous cloud seemed to be ever hanging–ominous of her name. We doubt not, that to plunge the dagger into the heart of an execrable Sioux, would be more grateful to her wish, more pleasing to her heart, than the taste of precious manna to her tongue…

…Inside the circle were the musicians and persons of distinction, not least of whom was our heroine, who sat upon a blanket spread upon the ground. She was plainly, though richly dressed in blue broad-cloth shawl and leggings. She wore the short skirt, a la Bloomer, and be it known that the females of all Indians we have seen, invariably wear the Bloomer skirt and pants. Their good sense, in this particular, at least, cannot, we think, be too highly commended. Two plumes, warrior feathers, were in her hair; these bore devices, stripes of various colored ribbon pasted on, as all braves have, to indicate the number of the enemy killed, and of scalps taken by the wearer. Her countenance betokened self-possession, and as she sat her fingers played furtively with the haft of a good sized knife.

The coterie leaving a large kettle hanging upon the cross-sticks over a fire, in which to cook a fat dog for a feast at the close of the ceremony, soon set off, in single file procession, to visit the camp of the respective chiefs, who remained at their lodges to receive these guests. In the march, our heroine was the third, two leading braves before her. No timid air and bearing were apparent upon the person of this wild-wood nymph; her step was proud and majestic, as that of a Forest Queen should be.

The party visited the various chiefs, each of whom, or his proxy, appeared and gave a harangue, the tenor of which, we learned, was to minister to their war spirit, to herald the glory of their tribe, and to exhort the practice of charity and good will to their poor. At the close of each speech, some donation to the beggar’s fun, blankets, provisions, &c., was made from the lodge of each visited chief. Some of the latter danced and sung around the ring, brandishing the war-club in the air and over his head. Chief “LOON’S FOOT,” whose lodge was near the Indian Agents residence, (the latter chief is the brother of Mrs. Judge ASHMAN at the Soo,) made a lengthy talk and gave freely…

…An evening’s interview, through an interpreter, with the chief, father of the Princess, disclosed that a small party of Sioux, at a time not far back, stole near unto the lodge of the the chief, who was lying upon his back inside, and fired a rifle at him; the ball grazed his nose near his eyes, the scar remaining to be seen–when the girl seizing the loaded rifle of her father, and with a few young braces near by, pursued the enemy; two were killed, the heroine shot one, and bore his scalp back to the lodge of NA-NAW-ONG-GA-BE, her father.

At this interview, we learned of a custom among the Chippewas, savoring of superstition, and which they say has ever been observed in their tribe. All the youths of either sex, before they can be considered men and women, are required to undergo a season of rigid fasting. If any fail to endure for four days without food or drink, they cannot be respected in the tribe, but if they can continue to fast through ten days it is sufficient, and all in any case required. They have then perfected their high position in life.

This Princess fasted ten days without a particle of food or drink; on the tenth day, feeble and nervous from fasting, she had a remarkable vision which she revealed to her friends. She dreamed that at a time not far distant, she accompanied a war party to the Sioux country, and the party would kill one of the enemy, and would bring home his scalp. The war party, as she had dreamed, was duly organized for the start.

Against the strongest remonstrance of her mother, father, and other friends, who protested against it, the young girl insisted upon going with the party; her highest ambition, her whole destiny, her life seemed to be at stake, to go and verify the prophecy of her dream. She did go with the war party. They were absent about ten or twelve days, the had crossed the Mississippi, and been into the Sioux territory. There had been no blood of the enemy to allay their thirst or to palliate their vengeance. They had taken no scalp to herald their triumphant return to their home. The party reached the great river homeward, were recrossing, when lo! they spied a single Sioux, in his bark canoe near by, whom they shot, and hastened exultingly to bear his scalp to their friends at the lodges from which they started. Thus was the prophecy of the prophetess realized to the letter, and herself, in the esteem of all the neighboring bands, elevated to the highest honor in all their ceremonies. They even hold her in superstitious reverence. She alone, of the females, is permitted in all festivities, to associate, mingle and to counsel with the bravest of the braves of her tribe…”

Benjamin Armstrong

Benjamin ArmstrongBenjamin Armstrong’s memoir Early Life Among the Indians also includes an account of the warrior daughter of Nenaa’angebi. In contrast to Morse, the outside observer, Armstrong was married to Buffalo’s niece and was the old chief’s personal interpreter. He lived in this area for over fifty years and knew just about everyone. His memoir, published over 35 years after Hanging Cloud got her fame, contains details an outsider wouldn’t have any way of knowing.

Unfortunately, the details don’t line up very well. Most conspicuously, Armstrong says that Nenaa’angebi was killed in the attack that brought his daughter fame. If that’s true, then I don’t know how Morse was able to record the Rice Lake chief’s speeches the following summer. It’s possible these were separate incidents, but it is more likely that Armstrong’s memories were scrambled. He warns us as much in his introduction. Some historians refuse to use Armstrong at all because of discrepancies like this and because it contains a good deal of fiction. I have a hard time throwing out Armstrong completely because he really does have the insider’s knowledge that is lacking in so many primary sources about this area. I don’t look at him as a liar or fraud, but rather as a typical northwoodsman who knows how to run a line of B.S. when he needs to liven up a story. Take what you will of it, these are pages 199-202 of Early Life Among the Indians.

“While writing about chiefs and their character it may not be amiss to give the reader a short story of a chief‟s daughter in battle, where she proved as good a warrior as many of the sterner sex.

In the ’50’s there lived in the vicinity of Rice Lake, Wis. a band of Indians numbering about 200. They were headed by a chief named Na-nong-ga-bee. This chief, with about seventy of his people came to La Point to attend the treaty of 1854. After the treaty was concluded he started home with his people, the route being through heavy forests and the trail one which was little used. When they had reached a spot a few miles south of the Namekagon River and near a place called Beck-qua-ah-wong they were surprised by a band of Sioux who were on the warpath and then in ambush, where a few Chippewas were killed, including the old chief and his oldest son, the trail being a narrow one only one could pass at a time, true Indian file. This made their line quite long as they were not trying to keep bunched, not expecting or having any thought of being attacked by their life long enemy.

The chief, his son and daughter were in the lead and the old man and his son were the first to fall, as the Sioux had of course picked them out for slaughter and they were killed before they dropped their packs or were ready for war. The old chief had just brought the gun to his face to shoot when a ball struck him square in the forehead. As he fell, his daughter fell beside him and feigned death. At the firing Na-nong-ga-bee’s Band swung out of the trail to strike the flanks of the Sioux and get behind them to cut off their retreat, should they press forward or make a retreat, but that was not the Sioux intention. There was not a great number of them and their tactic was to surprise the band, get as many scalps as they could and get out of the way, knowing that it would be but the work of a few moments, when they would be encircled by the Chippewas. The girl lay motionless until she perceived that the Sioux would not come down on them en-masse, when she raised her father‟s loaded gun and killed a warrior who was running to get her father‟s scalp, thus knowing she had killed the slayer of her father, as no Indian would come for a scalp he had not earned himself. The Sioux were now on the retreat and their flank and rear were being threatened, the girl picked up her father‟s ammunition pouch, loaded the rifle, and started in pursuit. Stopping at the body of her dead Sioux she lifted the scalp and tucked it under her belt. She continued the chase with the men of her band, and it was two days before they returned to the women and children, whom they had left on the trail, and when the brave little heroine returned she had added two scalps to the one she started with.

She is now living, or was, but a few years ago, near Rice Lake, Wis., the wife of Edward Dingley, who served in the war of rebellion from the time of the first draft of soldiers to the end of the war. She became his wife in 1857, and lived with him until he went into the service, and at this time had one child, a boy. A short time after he went to the war news came that all the party that had left Bayfield at the time he did as substitutes had been killed in battle, and a year or so after, his wife, hearing nothing from him, and believing him dead, married again. At the end of the war Dingley came back and I saw him at Bayfield and told him everyone had supposed him dead and that his wife had married another man. He was very sorry to hear this news and said he would go and see her, and if she preferred the second man she could stay with him, but that he should take the boy. A few years ago I had occasion to stop over night with them. And had a long talk over the two marriages. She told me the circumstances that had let her to the second marriage. She thought Dingley dead, and her father and brother being dead, she had no one to look after her support, or otherwise she would not have done so. She related the related the pursuit of the Sioux at the time of her father‟s death with much tribal pride, and the satisfaction she felt at revenging herself upon the murder of her father and kinsmen. She gave me the particulars of getting the last two scalps that she secured in the eventful chase. The first she raised only a short distance from her place of starting; a warrior she espied skulking behind a tree presumably watching for some one other of her friends that was approaching. The other she did not get until the second day out when she discovered a Sioux crossing a river. She said: “The good luck that had followed me since I raised my father‟s rifle did not now desert me,” for her shot had proved a good one and she soon had his dripping scalp at her belt although she had to wade the river after it.”

At this point, this is all I have to offer on the story of Hanging Cloud the ogichidaakwe. I’ll be sure to update if I stumble across anything else, but for now, we’ll have to be content with these two contradictory stories.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892. Print.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.

Chief Buffalo, Flat Mouth, and Tecumseh

April 28, 2013

The Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa painted by Charles Bird King c.1820 (Wikimedia Commons)

The Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa painted by Charles Bird King c.1820 (Wikimedia Commons)In contrast with other Great Lakes nations, the Lake Superior Ojibwe are often portrayed as not having had a role in the Seven Years War, Pontiac’s War, Tecumseh’s War, or the War of 1812. The Chequamegon Ojibwe are often characterized as being uniformly friendly toward whites, peacefully transitioning from the French and British to the American era. The Ojibwe leaders Buffalo of La Pointe and Flat Mouth of Leech Lake are seen as men who led their people into negotiations rather than battle with the United States.

No one tried harder to promote the idea of Ojibwe-American friendship than William W. Warren (1825-1853), the Madeline Island-born mix-blooded historian who wrote History of the Ojibway People. Warren details Ojibwe involvement in all of these late-18th and early 20th-century imperial conflicts, but then repeatedly dismisses it as solely the work of more easterly Ojibwe bands or a few rogue warriors. The reality was much more complicated.

It is true, the Lake Superior Ojibwe never entered into these wars as a single body, but the Lake Superior Ojibwe rarely did anything as a single body. Different bands, chiefs, and families pursued different policies. What is clear from digging deeper into the sources, however, is that the anti-American resistance ideologies of men like the Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa (The Prophet) had more followers around here than Warren would have you believe. The passage below, from none other than Warren himself, shows that these followers included Buffalo and Flat Mouth.

History of the Ojibway People is available free online, but I’m not going to link to it. I want you to check out or buy the second edition, edited and annotated by Theresa Schenck and published by the Minnesota Historical Society in 2009. It is not the edition I first read this story in, but this post does owe a great debt to Dr. Schenck’s footnotes. Also, if you get the book, you will find the added bonus of a second account of these same events from Julia Warren Spears, William’s sister (Appendix C). The passage that is reproduced here can be read on pages 227-231.

“… no event of any importance occured on the Chippeway and Wisconsin Rivers till the year 1808, when, under the influence of the excitement which the Shaw-nee prophet, brother of Tecumseh, succeeded in raising, even to the remotest village of the Ojibways, the men of the Lac Coutereille village, pillaged the trading house of Michel Cadotte at Lac Coutereilles, while under charge of a clerk named John Baptiste Corbin. From the lips of Mons. Corbin, who is still living at Lac Coutereille, at the advanced age of seventy-six years, and who has now been fifty-six years in the Ojibway country, I have obtained a reliable account of this transaction…”

“…In the year 1808, during the summer while John B. Corbin had charge of the Lac Coutereille post, messengers, whose faces were painted black, and whose actions appeared strange, arrived at the different principal villages of the Ojibways. In solemn councils they performed certain ceremonies, and told that the Great Spirit had at last condescended to hold communion with the red race, through the medium of a Shawano prophet, and that they had been sent to impart the glad tidings.

The Shawano sent them word that the Great Spirit was about to take pity on his red children, whom he had long forsaken for their wickedness. He bade them to return to the primitive usages and customs of their ancestors, to leave off the use of everything which the evil white race had introduced among them. Even the fire-steel must be discarded, and fire made as in ages past, by the friction of two sticks. And this fire, once lighted in their principal villages, must always be kept sacred and burning. He bade them to discard the use of fire-water—to give up lying and stealing and warring with one another. He even struck at some of the roots of the Me-da-we religion, which he asserted had become permeated with many evil medicines, and had lost almost altogether its original uses and purity. He bade the medicine men to throw away their evil and poisonous medicines, and to forget the songs and ceremonies attached thereto, and he introduced new medicines and songs in their place. He prophesied that the day was nigh, when, if the red race listened to and obeyed his words, the Great Spirit would deliver them from their dependence on the whites, and prevent their being finally down-trodden and exterminated by them. The prophet invited the Ojibways to come and meet him at Detroit, where in person, he would explain to them the revelations of the “Great Master of Life.” He even claimed the power of causing the dead to arise, and come again to life.

It is astonishing how quickly this new belief obtained possession in the minds of the Ojibways. It spread like wild-fire throughout their entire country, and even reached the remotest northern hunters who had allied themselves with the Crees and Assiniboines. The strongest possible proof which can be adduced of their entire belief, is in their obeying the mandate to throw away their medicine bags, which the Indian holds most sacred and inviolate. It is said that the shores of Sha-ga-waum-ik-ong were strewed with the remains of medicine bags, which had been committed to the deep. At this place, the Ojibways collected in great numbers. Night and day, the ceremonies of the new religion were performed, till it was at last determined to go in a body to Detroit, to visit the prophet. One hundred and fifty canoes are said to have actually started from Pt. Shag-a-waum-ik-ong for this purpose, and so strong was their belief, that a dead child was brought from Lac Coutereille to be taken to the prophet for resuscitation.

This large party arrived on their foolish journey, as far as the Pictured Rocks, on Lake Superior, when, meeting with Michel Cadotte, who had been to Sault Ste. Marie for his annual outfit of goods, his influence, together with information of the real motives of the prophet in sending for them, succeeded in turning them back.

The few Ojibways who had gone to visit the prophet from the more eastern villages of the tribe, had returned home disappointed, and brought back exaggerated accounts of the suffering through hunger, which the proselytes of the prophet who had gathered at his call, were enduring, and also giving the lie to many of the attributes which he had assumed. It is said that at Detroit he would sometimes leave the camp of the Indians, and be gone, no one knew whither, for three and four days at a time. On his return he would assert that he had been to the spirit land and communed with the master of life. It was, however, soon discovered that he only went and hid himself in a hollow oak which stood behind the hill on which the most beautiful portion of Detroit City is now built. These stories became current among the Ojibways, and each succeeding year developing more fully the fraud and warlike purpose of the Shawano, the excitement gradually died away among the Ojibways, and the medicine men and chiefs who had become such ardent believers, hung their heads in shame whenever the Shawano was mentioned.

Two men of “strong minds and unusual intelligence,” Buffalo of La Pointe (top) and Eshkibagikoonzhe or “Flat Mouth” of Leech Lake. (Wisconsin Historical Society) (Minnesota Historical Society)

Two men of “strong minds and unusual intelligence,” Buffalo of La Pointe (top) and Eshkibagikoonzhe or “Flat Mouth” of Leech Lake. (Wisconsin Historical Society) (Minnesota Historical Society)At this day it is almost impossible to procure any information on this subject from the old men who are still living, who were once believers and preached their religion, so anxious are they to conceal the fact of their once having been so egregiously duped. The venerable chiefs Buffalo, of La Pointe, and Esh-ke-bug-e-coshe, of Leech Lake, who have been men of strong minds and unusual intelligence, were not only firm believers of the prophet, but undertook to preach his doctrines.

One essential good resulted to the Ojibways through the Shawano excitement–they threw away their poisonous roots and medicines, and poisoning, which was formerly practiced by their worst class of medicine men, has since become entirely unknown.

So much has been written respecting the prophet and the new beliefs which he endeavored to inculcate amongst his red brethren, that we will no longer dwell on the merits or demerits of his pretended mission. It is now evident that he and his brother Tecumseh had in view, and worked to effect, a general alliance of the red race, against the whites, and their final extermination from the ‘Great Island which the great spirit had given as an inheritance to his red children.’”

From 1805 to 1811, the Shawnee Prophet Tenskwatawa and his brother Tecumseh spread a religious and political message from the Canadas in the north, to the Gulf of Mexico in the south, to the prairies of the west. They called for all Indians to abandon white ways, unite as one people, and create a British-protected Indian country between the Ohio and the Great Lakes. While he seldom convinced entire nations (including the Shawnee) to join him, Tecumseh gained followers from all over.

This picture of Tecumseh in British uniform was painted decades after his death by Benson John Lossing (Wikimedia Commons)

This picture of Tecumseh in British uniform was painted decades after his death by Benson John Lossing (Wikimedia Commons)His coalition came apart, however, at the Battle of Tippecanoe on November 7, 1811. Tecumseh was away recruiting more followers when American forces under William Henry Harrison defeated Tenskwatawa. Accounts suggest it was a closely-fought battle with the Americans suffering the most casualties. However, in the end Harrison prevailed due to his superior numbers.

With Tenskwatawa discredited, Tecumseh ended up raising a new coalition to fight alongside the British against the Americans in the War of 1812. He was killed in the Battle of the Thames, October 5, 1813, when the British forces under General Henry Procter abandoned their Indian allies on the battlefield.

After the War of 1812, British traders pulled out of their posts in American territory. However, the Ojibwe of Lake Superior continued to trade across the line in Canada. In 1822, the American agent Henry Schoolcraft’s gave his first description of Buffalo, a man he would come to know well over the next thirty-five years. He described “a chief decorated with British insignia.” Ten years later, Flat Mouth was telling Schoolcraft he had no right or ability to stop the Ojibwe from allying with the British. These chiefs were not men who were unwavering friends of the United States for their whole lives.

Buffalo and Flat Mouth lived to be very old men, and lived to see the Ojibwe cede their lands in treaties, suffer the tragic 1850-51 removal to Sandy Lake, and see the beginnings of a paternalist American regime on the newly-created reservations. Their Shawnee contemporary, Tecumseh, did not live that long.

Tecumseh’s life and death are documented in the second episode of the 2009 television miniseries American Experience: We Shall Remain. The episode, Tecumseh’s Vision, is very good throughout. The most interesting part comes at the very end when several of the expert interviewees comment on the meaning of Tecumseh’s death:

“I think Tecumseh is, in a sense, saved by his death. He’s saved for immortality through death on the battlefield.”

Stephen Warren, Augustana College

“One of the great things in icons is to bow out at the right time, and one of the things Tecumseh does is he never lets you down. He was there, articulating his position — uncompromisingly pro-Native American position. He never signs the treaties. He never reneges on those basic as principles of the sacrosanct aboriginal holding of this territory. He bows out at the peak of this great movement he is leading. He’s there, right at the end, whatever the odds are, fighting for it into the dying moments.”

John Sugden, author Tecumseh: A Life

“For some people, they may call him a troublemaker. And I think that’s because, in the end, he lost. Had he won, he’d have been, you know, a hero. But I think, to a degree, he still has to be recognized as a hero, for what he attempted to do. If he had a little more help, maybe he would have got a little farther down the line. If the British would have backed him up, like they were supposed to have, maybe the United States is only half as big as it is today.”

Sherman Tiger, Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

Stephen Warren and John Sugden indicate that he is a hero because of the way he died. Sherman Tiger seems to say that Tecumseh’s death, in part, is what kept him from being a hero, and that if he had more men, maybe his “vision” of a united Indian nation would have come true.

In 1811, the Ojibwe of Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi had hundreds of warriors experienced in battle with the Dakota Sioux. They were heirs to a military tradition that defeated the Iroquois and the Meskwaki (Fox). A handful of Ojibwe did fight beside Tecumseh, and according to John Baptiste Corbine through Warren, many more could have. It’s possible they could have tipped the balance and caused Tippecanoe or Thames to end differently. It is also possible that Buffalo, Flat Mouth, and other future Ojibwe leaders could have died on the battlefield.

Tecumseh died young and uncompromised. Buffalo and Flat Mouth faced many tough decisions and lived long enough to see their people lose their independence and most of their land. However, they were there to lead their people through the hard times of the removal period. Tecumseh wasn’t.

Ultimately, it’s hard to say which is more heroic? What do you think?

Sources:

Schenck, Theresa M., William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi,. [East Lansing]: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers: With Brief Notices of Passing Events, Facts, and Opinions, A.D. 1812 to A.D. 1842. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and, 1851. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1991. Print.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.

Maangozid’s Family Tree

April 14, 2013

(Amos Butler, Wikimedia Commons) I couldn’t find a picture of Maangozid on the internet, but loon is his clan, and “loon foot” is the translation of his name. The Northeast Minnesota Historical Center in Duluth has a photograph of Maangozid in the Edmund Ely papers. It is reproduced on page 142 of The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849 (2012) ed. Theresa Schenck.

In the various diaries, letters, official accounts, travelogues, and histories of this area from the first half of the nineteenth century, there are certain individuals that repeatedly find their way into the story. These include people like the Ojibwe chiefs Buffalo of La Pointe, Flat Mouth of Leech Lake, and the father and son Hole in the Day, whose influence reached beyond their home villages. Fur traders, like Lyman Warren and William Aitken, had jobs that required them to be all over the place, and their role as the gateway into the area for the American authors of many of these works ensure their appearance in them. However, there is one figure whose uncanny ability to show up over and over in the narrative seems completely disproportionate to his actual power or influence. That person is Maangozid (Loon’s Foot) of Fond du Lac.

Naagaanab, a contemporary of Maangozid (Undated, Newberry Library Chicago)

In fairness to Maangozid, he was recognized as a skilled speaker and a leader in the Midewiwin religion. His father was a famous chief at Sandy Lake, but his brothers inherited that role. He married into the family of Zhingob (Shingoop, “Balsam”) a chief at Fond du Lac, and served as his speaker. Zhingob was part of the Marten clan, which had produced many of Fond du Lac’s chiefs over the years (many of whom were called Zhingob or Zhingobiins). Maangozid, a member of the Loon clan born in Sandy Lake, was seen as something of an outsider. After Zhingob’s death in 1835, Maangozid continued to speak for the Fond du Lac band, and many whites assumed he was the chief. However, it was younger men of the Marten clan, Nindibens (who went by his father’s name Zhingob) and Naagaanab, who the people recognized as the leaders of the band.

Certainly some of Maangozid’s ubiquity comes from his role as the outward voice of the Fond du Lac band, but there seems to be more to it than that. He just seems to be one of those people who through cleverness, ambition, and personal charisma, had a knack for always being where the action was. In the bestselling book, The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell talks all about these types of remarkable people, and identifies Paul Revere as the person who filled this role in 1770s Massachusetts. He knew everyone, accumulated information, and had powers of persuasion. We all know people like this. Even in the writings of uptight government officials and missionaries, Maangozid comes across as friendly, hilarious, and most of all, everywhere.

Recently, I read The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849 (U. of Nebraska Press; 2012), edited by Theresa Schenck. There is a great string of journal entries spanning from the Fall of 1836 to the summer of 1837. Maangozid, feeling unappreciated by the other members of the band after losing out to Nindibens in his bid for leadership after the death of Zhingob, declares he’s decided to become a Christian. Over the winter, Maangozid visits Ely regularly, assuring the stern and zealous missionary that he has turned his back on the Midewiwin. The two men have multiple fascinating conversations about Ojibwe and Christian theology, and Ely rejoices in the coming conversion. Despite assurances from other Ojibwe that Maangozid has not abandoned the Midewiwin, and cold treatment from Maangozid’s wife, Ely continues to believe he has a convert. Several times, the missionary finds him participating in the Midewiwin, but Maangozid always assures Ely that he is really a Christian.

J.G. Kohl (Wikimedia Commons)

It’s hard not to laugh as Ely goes through these intense internal crises over Maangozid’s salvation when its clear the spurned chief has other motives for learning about the faith. In the end, Maangozid tells Ely that he realizes the people still love him, and he resumes his position as Mide leader. This is just one example of Maangozid’s personality coming through the pages.

If you’re scanning through some historical writings, and you see his name, stop and read because it’s bound to be something good. If you find a time machine that can drop us off in 1850, go ahead and talk to Chief Buffalo, Madeline Cadotte, Hole in the Day, or William Warren. The first person I’d want to meet would be Maangozid. Chances are, he’d already be there waiting.

Anyway, I promised a family tree and here it is. These pages come from Kitchi-Gami: wanderings round Lake Superior (1860) by Johann Georg Kohl. Kohl was a German adventure writer who met Maangozid at La Pointe in 1855.

When Kitchi-Gami was translated from German into English, the original French in the book was left intact. Being an uncultured hillbilly of an American, I know very little French. Here are my efforts at translating using my limited knowledge of Ojibwe, French-Spanish cognates, and Google Translate. I make no guarantees about the accuracy of these translations. Please comment and correct them if you can.

1) This one is easy. This is Gaadawaabide, Maangozid’s father, a famous Sandy Lake chief well known to history. Google says “the one with pierced teeth.” The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary translates it as “he had a gap in his teeth.” Most 19th-century sources call him Broken Tooth, La Breche, or Katawabida (or variants thereof).

2) Also easy–this is the younger Bayaaswaa, the boy whose father traded his life for his when he was kidnapped by the Meskwaki (Fox) (see post from March 30, 2013). Bayaaswaa grew to be a famous chief at Sandy Lake who was instrumental in the 18th-century Ojibwe expansion into Minnesota. Google says “the man who makes dry.” The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary lists bayaaswaad as a word for the animate transitive verb “dry.”

3) Presumably, this mighty hunter was the man Warren called Bi-aus-wah (Bayaaswaa) the Father in History of the Ojibways. That isn’t his name here, but it was very common for Anishinaabe people to have more than one name. It says “Great Skin” right on there. Google has the French at “the man who carries a large skin.” Michiiwayaan is “big animal skin” according to the OPD.

4) Google says “because he had very red skin” for the French. I don’t know how to translate the Ojibwe or how to write it in the modern double-vowel system.

5) Weshki is a form of oshki (new, young, fresh). This is a common name for firstborn sons of prominent leaders. Weshki was the name of Waabojiig’s (White Fisher) son, and Chief Buffalo was often called in Ojibwe Gichi-weshki, which Schoolcraft translated as “The Great Firstborn.”

6) “The Southern Sky” in both languages. Zhaawano-giizhig is the modern spelling. For an fascinating story of another Anishinaabe man, named Zhaawano-giizhigo-gaawbaw (“he stands in the southern sky”), also known as Jack Fiddler, read Killing the Shamen by Thomas Fiddler and James R. Stevens. Jack Fiddler (d.1907), was a great Oji-Cree (Severn Ojibway) chief from the headwaters of the Severn River in northern Ontario. His band was one of the last truly uncolonized Indian nations in North America. He commited suicide in RCMP custody after he was arrested for killing a member of his band who had gone windigo.

7) Google says, “the timber sprout.” Mitig is tree or stick. Something along the lines of sprouting from earth makes sense with “akosh,” but my Ojibwe isn’t good enough to combine them correctly in the modern spelling. Let me know if you can.

8) Google just says, “man red head.” Red Head is clearly the Ojibwe meaning also–miskondibe (OPD).

9) “The Sky is Afraid of the Man”–I can’t figure out how to write this in the modern Ojibwe, but this has to be one of the coolest names anyone has ever had.

**UPDATE** 5/14/13

Thank you Charles Lippert for sending me the following clarifications:

“Kadawibida Gaa-dawaabide Cracked Tooth

Bajasswa Bayaaswaa Dry-one

Matchiwaijan Mechiwayaan Great Hide

Wajki Weshki Youth

Schawanagijik Zhaawano-giizhig Southern Skies

Mitiguakosh Mitigwaakoonzh Wooden beak

Miskwandibagan Miskwandibegan Red Skull

Gijigossekot Giizhig-gosigwad The Sky Fears

“I am cluless on Wajawadajkoa. At first I though it might be a throat word (..gondashkwe) but this name does not contain a “gon”. Human skin usually have the suffix ..azhe, which might be reflected here as aja with a 3rd person prefix w.”

Kohl’s Kitchi-Gami is a very nice, accessible introduction to the culture of this area in the 1850s. It’s a little light on the names, dates, and events of the narrative political history that I like so much, but it goes into detail on things like houses, games, clothing, etc.

There is a lot to infer or analyze from these three pages. What do you think? Leave a comment, and look out for an upcoming post about Tagwagane, a La Pointe chief who challenges the belief that “the Loon totem [is] the eldest and noblest in the land.”

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings round Lake Superior. London: Chapman and Hall, 1860. Print.

Miller, Cary. Ogimaag: Anishinaabeg Leadership, 1760-1845. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2010. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Kah-puk-wi-e-kah: Cornucopia, Herbster, or Port Wing?

March 30, 2013

Official railroad map of Wisconsin, 1900 / prepared under the direction of Graham L. Rice, Railroad Commissioner. (Library of Congress) Check out Steamboat Island in the upper right. According to the old timers, that’s the one that washed away.

Not long ago, a long-running mystery was solved for me. Unfortunately, the outcome wasn’t what I was hoping for, but I got to learn a new Ojibwe word and a new English word, so I’ll call it a victory. Plus, there will be a few people–maybe even a dozen who will be interested in what I found out.

Go Big Red!

First a little background for those who haven’t spent much time in Cornucopia, Herbster, or Port Wing. The three tiny communities on the south shore have a completely friendly but horribly bitter animosity toward one another. Sure they go to school together, marry each other, and drive their firetrucks in each others’ parades, but every Cornucopian knows that a Fish Fry is superior to a Smelt Fry, and far superior to a Fish Boil. In the same way, every Cornucopian remembers that time the little league team beat PW. Yeah, that’s right. It was in the tournament too!

If you haven’t figured it out yet, my sympathies lie with Cornucopia, and most of the animosity goes to Port Wing (after all, the Herbster kids played on our team). That’s why I’m upset with the outcome of this story even though I solved a mystery that had been nagging me.

“A bay on the lake shore situated forty miles west of La Pointe…”

This all began several years ago when I read William W. Warren’s History of the Ojibway People for the first time. Warren, a mix-blood from La Pointe, grew up speaking Ojibwe on the island. His American father sent him to the East to learn to read and write English, and he used his bilingualism to make a living as an interpreter when he returned to Lake Superior. His mother was a daughter of Michel and Madeline Cadotte, and he was related to several prominent people throughout Ojibwe country. His History is really a collection of oral histories obtained in interviews with chiefs and elders in the late 1840s and early 1850s. He died in 1853 at age 28, and his manuscript sat unpublished for several decades. Luckily for us, it eventually was, and for all its faults, it remains the most important book about the history of this area.

As I read Warren that first time, one story in particular jumped out at me:

Warren, William W. History of the Ojibway Nation. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1885. Print. Pg. 127 Available on Google Books.

Pg. 129 Warren uses the sensational racist language of the day in his description of warfare between the Fox and his Ojibwe relatives. Like most people, I cringe at lines like “hellish whoops” or “barbarous tortures which a savage could invent.” For a deeper look at Warren the man, his biases, and motivations, I strongly recommend William W. Warren: the life, letters, and times of an Ojibwe leader by Theresa Schenck (University of Nebraska Press, 2007)

I recognized the story right away:

Cornucopia, Wisconsin postcard image by Allan Born. In the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society (WHI Image ID: 84185)

This marker, put up in 1955, is at the beach in Cornucopia. To see it, go east on the little path by the artesian well.

It’s clear Warren is the source for the information since it quotes him directly. However, there is a key difference. The original does not use the word “Siskiwit” (a word derived from the Ojibwe for the “Fat” subspecies of Lake Trout abundant around Siskiwit Bay) in any way. It calls the bay Kah-puk-wi-e-kah and says it’s forty miles west of La Pointe. This made me suspect that perhaps this tragedy took place at one of the bays west of Cornucopia. Forty miles seemed like it would get you a lot further west of La Pointe than Siskiwit Bay, but then I figured it might be by canoe hugging the shoreline around Point Detour. This would be considerably longer than the 15-20 miles as the crow flies, so I was somewhat satisfied on that point.

Still, Kah-puk-wi-e-kah is not Siskiwit, so I wasn’t certain the issue was resolved. My Ojibwe skills are limited, so I asked a few people what the word means. All I could get was that the “Kah” part was likely “Gaa,” a prefix that indicates past tense. Otherwise, Warren’s irregular spelling and dropped endings made it hard to decipher.

Then, in 2007, GLIFWC released the amazing Gidakiiminaan (Our Earth): An Anishinaabe Atlas of the 1836, 1837, and 1842 Treaty Ceded Territories. This atlas gives Ojibwe names and translations for thousands of locations. On page 8, they have the south shore. Siskiwit Bay is immediately ruled out as Kah-puk-wi-e-kah, and so is Cranberry River (a direct translation of the Ojibwe Mashkiigiminikaaniwi-ziibi. However, two other suspects emerge. Bark Bay (the large bay between Cornucopia and Herbster) is shown as Apakwaani-wiikwedong, and the mouth of the Flagg River (Port Wing) is Gaa-apakwaanikaaning.

On the surface, the Port Wing spelling was closer to Warren’s, but with “Gaa” being a droppable prefix, it wasn’t a big difference. The atlas uses the root word apakwe to translate both as “the place for getting roofing-bark,” Apakwe in this sense referring to rolls of birch bark covering a wigwam. For me it was a no-brainer. Bark Bay is the biggest, most defined bay in the area. Port Wing’s harbor is really more of a swamp on relatively straight shoreline. Plus, Bark Bay has the word “bark” right in it. Bark River goes into Bark Bay which is protected by Bark Point. Bark, bark, bark–roofing bark–Kapukwiekah–done.

Cornucopia had lost its one historical event, but it wasn’t so bad. Even though Bark Bay is closer to Herbster, it’s really between the two communities. I was even ready to suggest taking the word “Siskiwit” off the sign and giving it to Herbster. I mean, at least it wasn’t Port Wing, right?

Over the next few years, it seemed my Bark Bay suspicions were confirmed. I encountered Joseph Nicollet’s 1843 map of the region:

Then in 2009, Theresa Schenck of the University of Wisconsin-Madison released an annotated second edition of Warren’s History. Dr. Schenck is a Blackfeet tribal member but is also part Ojibwe from Lac Courte Oreilles. She is, without doubt, the most knowledgeable and thorough researcher currently working with written records of Ojibwe history. In her edition of Warren, the story begins on page 83, and she clearly has Kah-puk-wi-e-kah footnoted as Bark Bay–mystery solved!

But maybe not. Just this past year, Dr. Schenck edited and annotated the first published version of The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849. Ely was a young Protestant missionary working for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) in the Ojibwe communities of Sandy Lake, Fond du Lac, and Pokegama on the St. Croix. He worked under Rev. Sherman Hall of La Pointe, and made several trips to the island from Fond du Lac and the Brule River. He mentions the places along the way by what they were called in the 1830s and 40s. At one point he gets lost in the woods northwest of La Pointe, but he finds his way to the Siscoueka sibi (Siskiwit River). Elsewhere are references to the Sand, Cranberry, Iron, and “Bruley” Rivers, sometimes by their Ojibwe names and sometimes translated.

On almost all of these trips, he mentions passing or stopping at Gaapukuaieka, and to Ely and all those around him, Gaapukuaieka means the mouth of the Flagg River (Port Wing).

There is no doubt after reading Ely. Gaapukuaieka is a well-known seasonal camp for the Fond du Lac and La Pointe bands and a landmark and stopover on the route between those two important Ojibwe villages. Bark Bay is ruled out, as it is referred to repeatedly as Wiigwaas Point/Bay, referring to birch bark more generally. The word apakwe comes up in this book not in reference to bark, but as the word for rushes or cattails that are woven into mats. Ely even offers “flagg” as the English equivalent for this material. A quick dictionary search confirmed this meaning. Gaapukuaieka is Port Wing, and the name of the Flagg River refers to the abundance of cattails and rushes.

My guess is that the good citizens of Cornucopia asked the State Historical Society to put up a historical marker in 1955. Since no one could think of any history that happened in Cornucopia, they just pulled something from Warren assuming no one would ever check up on it. Now Cornucopia not just faces losing its only historical event, it faces the double-indignity of losing it to Port Wing.

William Whipple Warren (1825-1853) wrote down the story of Bayaaswaa from the oral history of the chief’s descendents.

So what really happened here?

Because the oral histories in Warren’s book largely lack dates, they can be hard to place in time. However, there are a few clues for when this tragedy may have happened. First, we need a little background on the conflict between the “Fox” and Ojibwe.

The Fox are the Meskwaki, a nation the Ojibwe called the Odagaamiig or “people on the other shore.” Since the 19th-century, they have been known along with the Sauk as the “Sac and Fox.” Today, they have reservations in Iowa, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Warfare between the Chequamegon Ojibwe and the Meskwaki broke out in the second half of the 17th-century. At that time, the main Meskwaki village was on the Fox River near Green Bay. However, the Meskwaki frequently made their way up the Wisconsin River to the Ontonagon and other parts of what is now north-central Wisconsin. This territory included areas like Lac du Flambeau, Mole Lake, and Lac Vieux Desert. The Ojibwe on the Lake Superior shore also wanted to hunt these lands, and war broke out. The Dakota Sioux were also involved in this struggle for northern Wisconsin, but there isn’t room for them in this post.

In theory, the Meskwaki and Ojibwe were both part of a huge coalition of nations ruled by New France, and joined in trade and military cooperation against the Five Nations or Iroquois Confederacy. In reality, the French at distant Quebec had no control over large western nations like the Ojibwe and Meskwaki regardless of what European maps said about a French empire in the Great Lakes. The Ojibwe and Meskwaki pursued their own politics and their own interests. In fact, it was the French who ended up being pulled into the Ojibwe war.

What history calls the “Fox Wars” (roughly 1712-1716 and 1728-1733) were a series of battles between the Meskwaki (and occasionally their Mascouten, Kickapoo, and Sauk relatives) against everyone else in the French alliance. For the Ojibwe of Chequamegon, this fight started several decades earlier, but history dates the beginning at the point when everyone else got involved.

By the end of it, the Meskwaki were decimated and had to withdraw from northern Wisconsin and seek shelter with the Sauk. The only thing that kept them from being totally eradicated was the unwillingness of their Indian enemies to continue the fighting (the French, on the other hand, wanted a complete genocide). The Fox Wars left northern Wisconsin open for Ojibwe expansion–though the Dakota would have something to say about that.

So, where does this story of father and son fit? Warren, as told by the descendents of the two men, describes this incident as the pivotal event in the mid-18th century Ojibwe expansion outward from Lake Superior. He claims the war party that avenged the old chief took possession of the former Meskwaki villages, and also established Fond du Lac as a foothold toward the Dakota lands.

According to Warren, the child took his father’s name Bi-aus-wah (Bayaaswaa) and settled at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi. From Sandy Lake, the Ojibwe systematically took control of all the major Dakota villages in what is now northern Minnesota. This younger Bayaaswaa was widely regarded as a great and just leader who tried to promote peace and “rules of engagement” to stop the sort of kidnapping and torture that he faced as a child. Bayaaswaa’s leadership brought prestige to his Loon Clan, and future La Pointe leaders like Andeg-wiiyaas (Crow’s Meat) and Bizhiki (Buffalo), were Loons.

So, how much of this is true, and how much are we relying on Warren for this story? It’s hard to say. The younger Bayaaswaa definitely appears in both oral and written sources as an influential Sandy Lake chief. His son Gaa-dawaabide (aka. Breche or Broken Tooth) became a well-known chief in his own right. Both men are reported to have lived long lives. Broken Tooth’s son, Maangozid (Loon’s Foot) of Fond du Lac, was one of several grandsons of Bayaaswaa alive in Warren’s time and there’s a good chance he was one of Warren’s informants.

Caw-taa-waa-be-ta, Or The Snagle’d Tooth by James Otto Lewis, 1825 (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: WHi-26732) “Broken Tooth” was the son of Bayaaswaa the younger and the grandson of the chief who gave his life. Lewis was self-taught, and all of his portraits have the same grotesque or cartoonish look that this one does.

Within a few years of Warren’s work, Maangozid described his family history to the German travel writer Johann Kohl. This family history is worth its own post, so I won’t get into too much detail here, but it’s important to mention that Maangozid knew and remembered his grandfather. Broken Tooth, Maangozid’s father and Younger Bayaaswaa’s son, is thought to have been born in the 1750s. This all means that it is totally possible that the entire 130-year gap between Warren and the Fox Wars is spanned by the lifetimes of just these three men. This also makes it totally plausible that the younger Bayaaswaa was born in the 1710s or 20s and would have been a child during the Fox Wars.

My guess is that the attack at Gaapukuaieka and the death of the elder Bayaaswaa occurred during the second Fox War, and that the progress of the avenging war party into the disputed territories coincides with the decimation of the Meskwaki as described by the French records. While I don’t think the entire Ojibwe expansion of the 1700s can be attributed to this event, Ojibwe people in the 1850s, over a century later still regarded it as a highly-significant symbolic moment in their history.

So what’s to be done?

[I was going to do some more Port Wing jokes here, but writing about war, torture, and genocide changes the tone of a post very quickly.]

I would like to see the people of Cornucopia and Port Wing get together with the Sandy Lake, Fond du Lac, and Red Cliff bands and possibly the Meskwaki Nation, to put a memorial in its proper place. It should be more than a wooden marker. It needs to recognize not only the historical significance, but also the fact that many people died on that day and in the larger war. This is a story that should be known in our area, and known accurately.

If Cornucopia still needs a history, we can put up a marker for the time we beat Port Wing in the tournament.

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Gidakiiminaan = Our Earth. Odanah, WI: Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, 2007. Print.

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings round Lake Superior. London: Chapman and Hall, 1860. Print.

Loew, Patty. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal.

Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2001. Print.

Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1995. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. The Voice of the Crane Echoes Afar: The Sociopolitical Organization of the Lake Superior Ojibwa, 1640-1855. New York: Garland Pub., 1997. Print.

———— William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1853. Print.

Warren, William W., and Edward D. Neill. History of the Ojibway Nation. Minneapolis: Ross & Haines, 1957. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1991. Print.

“Wisconsin Historical Images.” Wisconsin Historical Society, n.d. Web. 30 Mar. 2013.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.

…a donation of twenty-four sections of land covering the graves of our fathers, our sugar orchards, and our rice lakes and rivers…

March 29, 2013

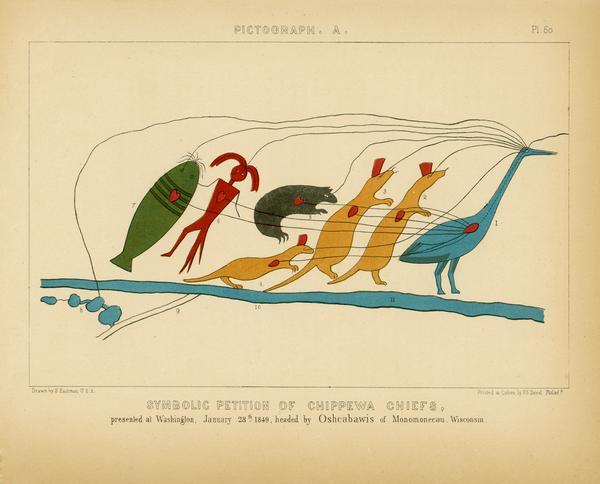

Symbolic Petition of Chippewa Chiefs: Original birch bark petition of Oshkaabewis copied by Seth Eastman and printed in “Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States” by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (1851). Digitized by University of Wisconsin Libraries Wisconsin Electronic Reader project (1998).

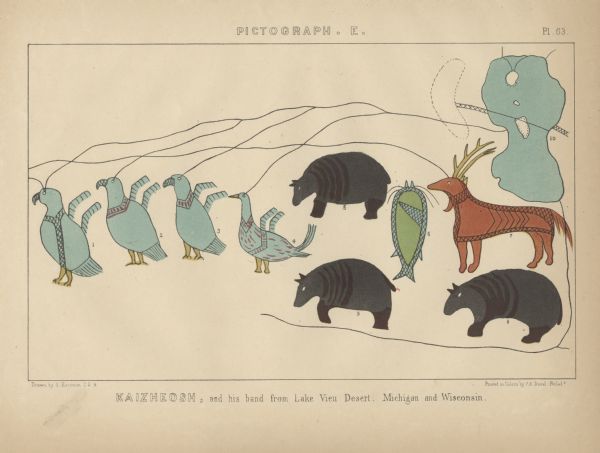

For the first post on Chequamegon History, I thought I’d share my research into an image that has been circulating around the area for several years now. The image shows seven Ojibwe chiefs by their doodemag (clan symbols), connected by heart and mind to Lake Superior and to some smaller lakes. The clans shown are the Crane, Marten, Bear, Merman, and Bullhead.

All the interpretations I’ve heard agree that this image is a copy of a birch bark pictograph, and that it represents a unity among the several chiefs and their clans against Government efforts to remove the Lake Superior bands to Minnesota.

While there is this agreement on the why question of this petition’s creation, the who and when have been a source of confusion. Much of this confusion stems from efforts to connect this image to the famous La Pointe chief, Buffalo (Bizhiki/Gichi-weshkii).

In 2007, the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) released the short documentary Mikwendaagoziwag: They Are Remembered. While otherwise a very good overview of the Lake Superior Ojibwe in this era, it incorrectly uses this image to describe Buffalo going to Washington D.C. in 1849. Buffalo is famous for a trip to Washington in 1852, but he was not part of the 1849 group.

At the time the GLIFWC film was released, the Wisconsin Historical Society website referred to this pictograph as, “Chief Buffaloʼs Petition to the President,” and identified the crane as Buffalo. Citing oral history from Lac Courte Oreilles, the Society dated the petition after the botched 1850-51 removal to Sandy Lake, Minnesota that resulted in hundreds of Ojibwe deaths from disease and starvation due to negligence, greed, and institutional racism on the part of government officials. The Historical Society has since revised its description to re-date the pictograph at 1848-49, but it still incorrectly lists Buffalo, a member of the Loon Clan, as being depicted by the crane. The Sandy Lake Tragedy, has deservedly gained coverage by historians in recent years, but the pictographic petition came earlier and was not part of it.

If the Historical Society had contacted Chief Buffaloʼs descendants in Red Cliff, they would have known that Buffalo was from the Loon Clan. The relationship between the Loons and the Cranes, as far as which clan can claim the hereditary chieftainship of the La Pointe Band, is very interesting and covered extensively in Warrenʼs History of the Ojibwe People. It would make a good subject for a future post.

After looking into the history of this image, I can confidently say that Buffalo is not one of the chiefs represented. It was created before Sandy Lake and Buffalo’s journey, but it is related to those events. Here is the story:

In late 1848, a group of Ojibwe chiefs went to Washington. They wanted to meet directly with President James K. Polk to ask for a permanent reservations in Wisconsin and Michigan. At that time the Ojibwe did not hold title to any part of the newly-created state of Wisconsin or Upper Michigan, having ceded these lands in the treaties in 1837 and 1842. In signing the treaties, they had received guarantees that they could stay in their traditional villages and hunt, fish, and gather throughout the ceded territory. However, by 1848, rumors were flying of removal of all Ojibwe to unceded lands on the Mississippi River in Minnesota Territory. These chiefs were trying to stop that from happening.

John Baptist Martell, a mix-blood, acted as their guide and interpreter. The government officials and Indian agents in the west were the ones actively promoting removal, so they did not grant permission (or travel money) for the trip. The chiefs had to pay their way as they went by putting themselves on display and dancing as they went from town to town.

Martell was accused by government officials of acting out of self interest, but the written petition presented to congress asked for, “a donation of twenty-four sections of land covering the graves of our fathers, our sugar orchards, and our rice lakes and rivers, at seven different places now occupied by us at villages…” The chiefs claimed to be acting on behalf of the chiefs of all the Lake Superior bands, and there is reason to believe them given that their request is precisely what Chief Buffalo and other leaders continued to ask for up until the Treaty of 1854.

This written petition accompanied the pictographic petitions. It clearly states the goal of the the chiefs was to secure permanent reservations around the traditional villages east of the Mississippi.

The visiting Ojibwes made a big impression on the nationʼs capital and positive accounts of the chiefs, their families, and their interpreter appeared in the magazines of the day. Congress granted them $6000 for their expenses, which according to their critics was a scheme by Martell. However, it is likely they were vilified by government officials for working outside the colonial structure and for trying to stop the removal rather than for any ill-intentions of the part of their interpreter. A full scholarly study of the 1848-49 trip remains to be done, however.

Amid articles on the end of the slave trade, the California Gold Rush, and the benefits of the “passing away of the Celt” during the Great Irish Famine, two articles appeared in Littell’s Living Age magazine about the 1849 delegation. The first is tragic, and the second is comical.

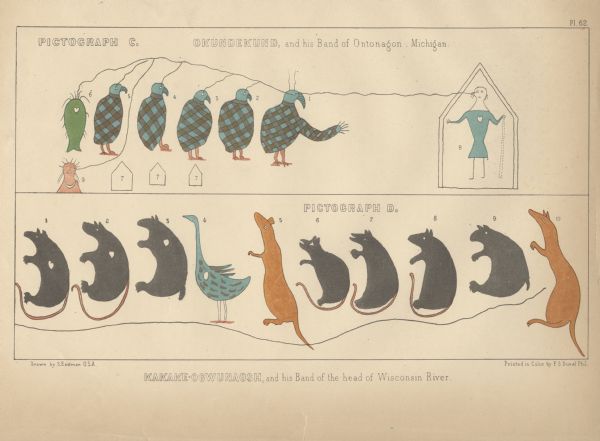

Along with written letters and petitions supporting the Ojibwe cause, the chiefs carried not only the one, but several birchbark pictographs. The pictographs show the clan animals of several chiefs and leading men from several small villages from the mouth of the Ontonagon River to Lac Vieux Desert in Upper Michigan and smaller satellite communities in Wisconsin. After seeing these petitions, the artist Seth Eastman copied them on paper and gave them to Henry Schoolcraft who printed and explained them alongside his criticism of the trip. They appear in his 1851 Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States.

Kenisteno, and his Band of Trout Lake, Wisconsin

Okundekund, and his Band of Ontonagon, Michigan (Upper) Kakake-ogwunaosh, and his Band of the head of Wisconsin River (Lower)

According to Schoolcraft, the crane in the most famous pictograph is Oshkaabewis, a Crane-clan chief from Lac Vieux Desert, and the leader of the 1848-49 expedition. In the Treaty of 1854, he is listed as a first chief from Lac du Flambeau in nearby Wisconsin. It makes sense that someone named Oshkaabewis would lead a delegation since the word oshkaabewis is used to describe someone who carries messages and pipes for a civil chief.

Kaizheosh [Gezhiiyaash], and his band from Lake Vieu Desert, Michigan and Wisconsin (University of Nebraska Libraries)

Long Story Short…

This is not Chief Buffalo or anyone from the La Pointe Band, and it was created before the Sandy Lake Tragedy. However it is totally appropriate to use the image in connection with those topics because it was all part of the efforts of the Lake Superior Ojibwe to resist removal in the late 1840s and early 1850s. However, when you do, please remember to credit the Lac Vieux Desert/Ontonagon chiefs who created these remarkable documents.