Chief Buffalo’s Death and Conversion: A new perspective

April 18, 2014

By Leo Filipczak

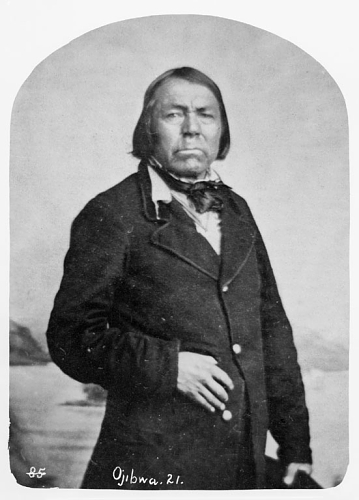

Chief Buffalo died at La Pointe on September 7, 1855 amid the festivities and controversy surrounding that year’s annuity payment. Just before his death, he converted to the Catholic faith, and thus was buried inside the fence of the Catholic cemetery rather than outside with the Ojibwe people who kept traditional religious practices.

His death was noted by multiple written sources at the time, but none seemed to really dive into the motives and symbolism behind his conversion. This invited speculation from later scholars, and I’ve heard and proposed a number of hypotheses about why Buffalo became Catholic.

Now, a newly uncovered document, from a familiar source, reveals new information. And while it may diminish the symbolic impact of Buffalo’s conversion, it gives further insight into an important man whose legend sometimes overshadows his life.

Buffalo’s Obituary

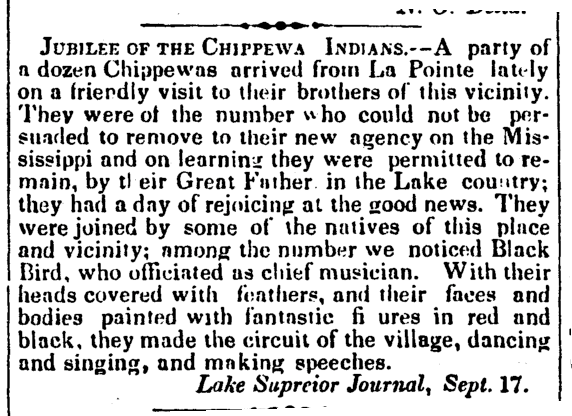

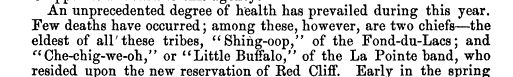

The most well-known account of Buffalo’s death is from an obituary that appeared in newspapers across the country. It was also recorded in the essay, The Chippewas of Lake Superior, by Dr. Richard F. Morse, who was an eyewitness to the 1855 payment.

While it’s not entirely clear if it was Morse himself who wrote the obituary, he seems to be a likely candidate. Much like the rest of Chippewas of Lake Superior, the obituary is riddled with the inaccuracies and betrays an unfamiliarity with La Pointe society:

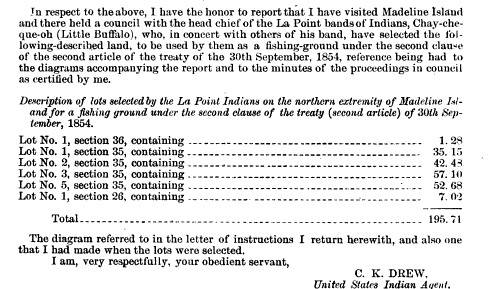

From Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Volume 3 (Digitized by Google Books)

It isn’t hard to understand how this obituary could invite several interpretations, especially when combined with other sources of the era and the biases of 20th and 21st-century investigators (myself included) who are always looking for a symbolic or political explanation.

Here, we will evaluate these interpretations.

Was Buffalo sending a message to the Ojibwe about the future?

The obituary states, “No tongue like Buffalo’s could control and direct the different bands.” An easy interpretation might suggest that he was trying to send a message that assimilation to white culture was the way of the future, and that all the Ojibwe should follow his lead. We do see suggestions in the writings of Henry Schoolcraft and William Warren that might support this conclusion.

The problem with this interpretation is that no Ojibwe leader, not even Buffalo, had that level of influence. Even if he wanted to, which would have been completely contrary to Ojibwe tolerance of religious pluralism, he could not have pulled a Henry VIII and converted his whole nation.

In fact, by 1855, Buffalo’s influence was at an all-time low. Recent scholarship has countered the image crafted by Benjamin Armstrong and others, of a chief whose trip to Washington and leadership through the Treaty of 1854 made him more powerful in his final years. Consider this 1852 depiction in Wagner and Scherzer’s Reisen in Nordamerika:

…Here we have the hereditary Chippewa chief, whose generations (totem) are carved in the ancient birch bark,** giving us profuse thanks for just a modest silver coin and a piece of dry cloth. What time can bring to a ruler!

So, did Buffalo decide in the last days of his life that Christianity was superior to traditional ways?

The reason why the obituary and other contemporary sources don’t go into the reasons for Buffalo’s conversion was because they hold the implicit assumption that Christianity is the one true religion. Few 19th-century American readers would be asking why someone would convert. It was a given. 160 years later, we don’t make this assumption anymore, but it should be explored whether or not this was purely a religious decision on Buffalo’s part.

I have a difficult time believing this. Buffalo had nearly 100 years to convert to Christianity if he’d wanted to. The traditional Ojibwe, in general, were extremely resistant to conversion, and there are several sources depicting Buffalo as a leader in the Midewiwin. This continuation of the above quote from Wagner and Scherzer shows Buffalo’s relationship to those who felt the Ojibwe needed Christianity.

Strangely, we later learned that the majestic Old Buffalo was violently opposed for years to the education and spiritual progress of the Indians. Probably, it’s because he suspected a better instructed generation would no longer obey. Presently, he tacitly accepts the existence of the school and even visits sometimes, where like ourselves, he has the opportunity to see the gains made in this school with its stubborn, fastidious look of an old German high council.

Accounts like this suggest a political rather than a spiritual motive.

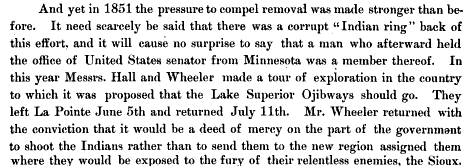

So, did Buffalo’s convert for political rather than spiritual reasons?

Some have tied Buffalo’s conversion to a split in the La Pointe Band after the Treaty of 1854, and it’s important to remember all the heated factional divisions that rose up during the 1855 payment. Until recently, my personal interpretation would have been that Buffalo’s conversion represented a final break with Blackbird and the other Bad River chiefs. Perhaps Buffalo felt alienated from most of the traditional Ojibwe after he found himself in the minority over the issue of debt payments. His final speech was short, and reveals disappointment and exasperation on the part of the aged leader.

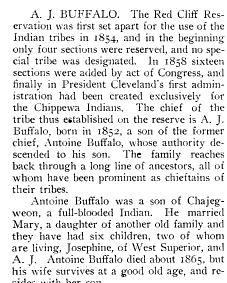

By the time of his death, most of his remaining followers, including the mix-blooded Ojibwe of La Pointe, and several of his children were Catholic, while most Ojibwe remained traditional. Perhaps there was additional jealousy over clauses in the treaty that gave Buffalo a separate reservation at Red Cliff and an additional plot of land. We see hints of this division in the obituary when an unidentified Ojibwe man blames the government for Buffalo’s death. This all could be seen as a separation forming between a Catholic Red Cliff and a traditional Bad River.

This interpretation would be perfect if it wasn’t grossly oversimplified. The division didn’t just happen in 1854. The La Pointe Band had always really been several bands. Those, like Buffalo’s, that were most connected to the mix-bloods and traders stayed on the Island more, and the others stayed at Bad River more. Still, there were Catholics at Bad River, and traditional Ojibwe on the Island. This dynamic and Buffalo’s place in it, were well-established. He did not have to convert to be with the “Catholic” faction. He had been in it for years.

Some have questioned whether Buffalo really converted at all. From a political point of view, one could say his conversion was really a show for Commissioner Manypenny to counter Blackbird’s pants (read this post if you don’t know what I’m talking about). I see that as overly cynical and out of character for Buffalo. I also don’t think he was ignorant of what conversion meant. He understood the gravity of what he was deciding, and being a ninety-year-old chief, I don’t think he would have felt pressured to please anyone.

So if it wasn’t symbolic, political, or religious zeal, why did Buffalo convert?

The Kohl article

As he documented the 1855 payment, Richard Morse’s ethnocentric values prevented any meaningful understanding of Ojibwe culture. However, there was another white outsider present at La Pointe that summer who did attempt to understand Ojibwe people as fellow human beings. He had come all the way from Germany.

The name of Johann Georg Kohl will be familiar to many readers who know his work Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings Around Lake Superior (1860). Kohl’s desire to truly know and respect the people giving him information left us with what I consider the best anthropological writing ever done on this part of the world.

My biggest complaint with Kohl is that he typically doesn’t identify people by name. Maangozid, Gezhiiyaash, and Zhingwaakoons show up in his work, but he somehow manages to record Blackbird’s speech without naming the Bad River chief. In over 100 pages about life at La Pointe in 1855, Buffalo isn’t mentioned at all.

So, I was pretty excited to find an untranslated 1859 article from Kohl on Google Books in a German-language weekly. The journal, Das Ausland, is a collection of writings that a would describe as ethnographic with a missionary bent.

I was even more excited as I put it through Google Translate and realized it discussed Buffalo’s final summer and conversion. It has to go out to the English-speaking world.

So without further ado, here is the first seven paragraphs of Remarks on the Conversion of the Canadian Indians and some Stories of Conversion by Johann Kohl. I apologize for any errors arising from the electronic translation. I don’t speak German and I can only hope that someone who does will see this and translate the entire article.

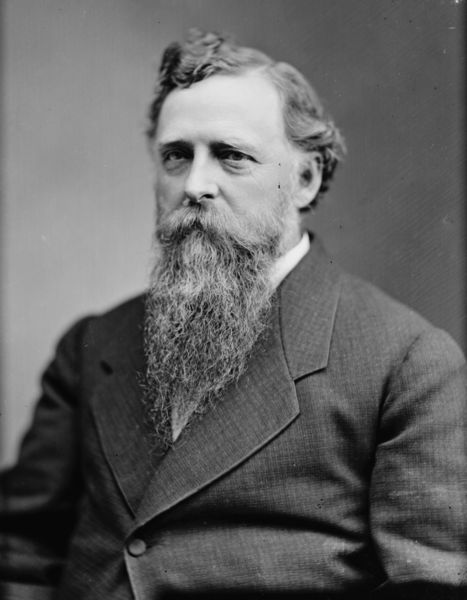

J. G. Kohl (Wikimedia Images)

Das Ausland.

Eine Wochenschrift

fur

Kunde des geistigen und sittlichen Lebens der Völker

[The Foreign Lands: A weekly for scholars of the moral and intellectual lives of foreign nations]

Nr. 2 8 January 1859

Remarks on the Conversion of the Canadian Indians and some Stories of Conversion

By J.G. Kohl

A few years ago, when I was on “La Pointe,” one of the so-called “Apostle Islands” in the western corner of the great Lake Superior, there still lived the old chief of the local Indians, the Chippeway or Ojibbeway people, named “Buffalo,” a man “of nearly a hundred years.” He himself was still a pagan, but many of his children, grandchildren and closest relatives, were already Christians.

I was told that even the aged old Buffalo himself “ébranlé [was shaking]”, and they told me his state of mind was fluctuating. “He thinks highly of the Christian religion,” they told me, “It’s not right to him that he and his family be of a different faith. He is afraid that he will be separated in death. He knows he will not be near them, and that not only his body should be brought to another cemetery, but also he believes his spirit shall go into another paradise away from his children.”

But Buffalo was the main representative of his people, the living embodiment, so to speak, of the old traditions and stories of his tribe, which once ranged over not only the whole group of the Apostle Islands, but also far and wide across the hunting grounds of the mainland of northern Wisconsin. His ancestors and his family, “the Totem of the Loons” (from the diver)* make claim to be the most distinguished chiefly family of the Ojibbeways. Indeed, they believe that from them and their village a far-reaching dominion once reached across all the tribes of the Ojibbeway Nation. In a word, a kind of monarchy existed with them at the center.

(*The Loon, or Diver, is a well-known large North American bird).

Old Buffalo, or Le Boeuf, as the French call him, or Pishiki, his Indian name, was like the last reflection of the long-vanished glory. He was stuck too deep in the old superstition. He was too intertwined with the Medä Order, the Wabanos, and the Jossakids, or priesthood, of his people. A conversion to Christianity would have destroyed his influence in a still mostly-pagan tribe. It would have been the equivalent of voluntarily stepping down from the throne he previously had. Therefore, in spite of his “doubting” state of mind, he could not decide to accept the act of baptism.

One evening, I visited old Buffalo in his bark lodge, and found in him grayed and stooped by the years, but nevertheless still quite a sprightly old man. Who knows what kind of fate he had as an old Indian chief on Lake Superior, passing his whole life near the Sioux, trading with the North West Company, with the British and later with the Americans. With the Wabanos and Jossakids (priests and sorcerers) he conjured for his people, and communed with the sky, but here people would call him an “old sinner.”

But still, due to his advanced age I harbored a certain amount of respect for him myself. He took me in, so kindly, and never forgot even afterwards, promising to remember my visit, as if it had been an honor for him. He told me much of the old glory of his tribe, of the origin of his people, and of his religion from the East. I gave him tobacco, and he, much more generously,gave me a beautiful fife. I later learned from the newspapers that my old host, being ill, and soon after my departure from the island, he departed from this earth. I was seized by a genuine sorrow and grieved for him. Those papers, however, reported a certain cause for consolation, in that Buffalo had said on his deathbed, he desired to be buried in a Christian way. He had therefore received Christianity and the Lord’s Supper, shortly before his death, from the Catholic missionaries, both with the last rites of the Church, and with a church funeral and burial in the Catholic cemetery, where in addition to those already resting, his family would be buried.

The story and the end of the old Buffalo are not unique. Rather, it was something rather common for the ancient pagan to proceed only on his death-bed to Christianity, and it starts not with the elderly adults on their deathbeds, but with their Indian families beginning with their young children. The parents are then won over by the children. For the children, while they are young and largely without religion, the betrayal of the old gods and laws is not so great. Therefore, the parents give allow it more easily. You yourself are probably already convinced that there is something fairly good behind Christianity, and that their children “could do quite well.” They desire for their children to attain the blessing of the great Christian God and therefore often lead them to the missionaries, although they themselves may not decide to give up their own ingrained heathen beliefs. The Christians, therefore, also prefer to first contact the youth, and know well that if they have this first, the parents will follow sooner or later because they will not long endure the idea that they are separated from their children in the faith. Because they believe that baptism is “good medicine” for the children, they bring them very often to the missionaries when they are sick…

Das Ausland: Wochenschrift für Länder- u. Völkerkunde, Volumes 31-32. Only about a quarter of the article is translated above. The remaining pages largely consist of Kohl’s observations on the successes and failures of missionary efforts based on real anecdotes.

Conclusion

According to Johann Kohl, who knew Buffalo, the chief’s conversion wasn’t based on politics or any kind of belief that Ojibwe culture and religion was inferior. Buffalo converted because he wanted to be united with his family in death. This may make the conversion less significant from a historical perspective, but it helps us understand the man himself. For that reason, this is the most important document yet about the end of the great chief’s long life.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892. Print.

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings round Lake Superior. London: Chapman and Hall, 1860. Print.

Loew, Patty. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2001. Print.

McElroy, Crocket. “An Indian Payment.” Americana v.5. American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Seth Eastman. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Collected and Prepared under the Direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per Act of Congress of March 3rd, 1847. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo, 1851. Print.

Wagner, Moritz, and Karl Von Scherzer. Reisen in Nordamerika in Den Jahren 1852 Und 1853. Leipzig: Arnold, 1854. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

By Leo Filipczak

Joseph Oesterreicher was only eighteen years old when he arrived at La Pointe in 1851. Less than a year earlier, he had left his native Germany for Mackinac, where he’d come to work for the firm of his older brother Julius and their in-laws, the Leopolds, another Bavarian Jewish family trading on Lake Superior.

In America, the Oesterreichers became the Austrians, but in his time at Mackinac, Joseph Austrian picked up very little English and even less of the Ojibwe and Metis-French that predominated at La Pointe. So, when Joseph made the move to his brother’s store at Madeline Island, it probably felt like he was immigrating all over again.

In the spring of 1851, he would have found at La Pointe, a society in flux. American settlement intensified as the fur trade economy made its last gasps. The island’s mix-blooded voyageurs found it harder and harder to make a living, and the Fur Company, and smaller traders like Julius Austrian, began to focus more on getting Ojibwe money from treaty annuity payments than they did from the actual trade in fur. This competition for Indian money had led to the deaths of hundreds of Ojibwe people in the Sandy Lake tragedy just a few months earlier.

The uncertainty surrounding Ojibwe removal would continue to hang heavily over the Island for both of Joseph’s years at La Pointe, as the Ojibwe leadership scrambled to process the horror of Sandy Lake and tried to secure a permanent homeland on the lakeshore.

The Austrians, however, found this an opportune time to be at the forefront of all the new business ventures in the Lake Superior country. They made money in merchandise, real estate, shipping, mining, lumber, government contracts, and every other way they could. This was not without controversy, and the name of Julius Austrian is frequently attached to documents showing the web of corruption and exploitation of Native people that characterized this era.

It’s difficult to say whether Joseph realized in 1851, while sweeping out his brother’s store or earning his unfortunate nickname, but he would become a very wealthy man. He lived into the 20th century and left a long and colorful memoir. I plan to transcribe and post all the stories from pages 26-66, which consists of Joseph’s time at La Pointe. Here is the first fourth [our original] installment:

Memoirs of Doodooshaboo

… continued from Mackinac 1850-1851.

Left for La Point: My First Trip on Lake Superior

1851

Julius Austrian

~ Madeline Island Museum

Mr. Julius Austrian was stationed at La Pointe, Madaline Island, one of the Apostle Group in Lake Superior, where he conducted an Indian Trading post, buying large quantities of fur and trading in fish on the premises previously occupied by the American Fur Co. whose stores, boats etc. the firm bought.

Julius Austrian, one of the partners had had charge of the store at La Point for five years past, he was at this time expected at Mackinaw and it had been arranged that I should accompany him back to La Pointe when he returned there, on the first boat of the season leaving the Sault Ste. Marie. I was to work in the store and to assist generally in all I was capable of at the wages of $10 a month. I gladly accepted the proposition being anxious for steady employment. Shortly after, brother Julius, his wife (a sister of H. Leopold) and I started on the side wheel steamer Columbia for Sault Ste. Marie, generally called “The Soo,” and waited there five days until the Napoleon, a small propellor on which we intended going to La Point, was ready to sail. During this time she was loading her cargo which had all to be transported from the Soo River to a point above the rapids across the Portage (a strip of land about ¾ of a mile connecting the two points) on a train road operated with horses. At this time there were only two propellers and three schooners on the entire Lake Superior, and those were hauled out below the rapids and moved up and over the portage and launched in Lake Superior. Another propeller Monticello, which was about half way across the Portage, was soon to be added to the Lake Superior fleet, which consisted of Independence & Napoleon and the Schooners Algonquin, Swallow, and Sloop Agate owned by my brother Julius. Quite different from the present day, where a very large number of steel ships on the chain of Lakes, some as much as 8000 tons capacity, navigate through the canal to Lake Superior from the lower lakes engaged in transporting copper, iron ore, pig iron, grain & flour from the various ports of Marquette, Houghton, Hancock, Duluth, and others. It was found necessary in later years to enlarge the locks of the canal to accomodate the larger sized vessels that had been constructed.

Building Sault Ste. Marie Canal. 1851.

Map of proposed Soo canal and locks 1852 (From The Honorable Peter White by Ralph D. Williams, 1910 pg. 121)

The ship canal at that time had not been constructed, but the digging of it had just been started. The construction of this canal employed hundreds of laborers, and it took years to complete this great piece of work, which had to be cut mostly through the solid rock. The State of Michigan appropriated thousands of sections of land for the purpose of building this canal, for the construction of which a company was incorporated under the name of Sault Ste. Marie Ship Canal & Land Co., who received the land in payment for building this canal, and which appropriation entitled the Co. to located in any unsold government land in the State of Michigan. The company availed itself of this privilege and selected large tracts of the best mineral and timber land in Houghton, Ontonagan & Kewanaw Counties, locating some of the land in the copper district, some of which proved afterwards of immense value, and on which were opened up some of the richest copper mines in the world, namely: Calumet, Hecla, and Quincy mines, and others. There were also very valuable timber lands covered by this grant.

The canal improved and enlarged as it now stands, is one of the greatest and most important artificial waterways in the world. A greater tonnage is transported through it annually that through the Suez or any other canal. In later years the canal was turned over by the State of Mich. to the General Government, which made it free of toll to all vessels and cargoes passing through it, even giving Canadian vessels the same privilege; whereas when operated by the State of Mich. toll was exacted from all vessels and cargoes using it.

The Napoleon, sailed by Capt. Ryder, had originally been a schooner, it had been turned into a propeller by putting in a small propeller engine. She had the great (?) speed of 8 miles an hour in calm weather, and had the reputation of beating any boat of the Lake in rolling in rough weather, and some even said she had rolled completely over turning right side up finally.

To return to my trip, after passing White Fish Point, the following day and getting into the open lake, we encountered a strong north wind raising considerable sea, causing our boat to toss and pitch, giving us our first experience of sea sickness on the trip. Beside the ordinary crew, we had aboard 25 horses for Ontonogan where we arrived the third day out. The Captain finding the depth of water was not sufficient to allow the boat to go inside the Ontonogan river and there being no dock outside, he attempted to land the horses by throwing them overboard, expecting them to swim ashore, to begin with, he had three thrown overboard and had himself with a few of his men lowered in the yawl boat to follow, he caught the halter of the foremost horse intending to guide him and the others ashore. The lake was exceedingly rough, and the poor horses became panic stricken and when near the shore turned back swimming toward the boat with hard work. The Captain finally succeeded in land those that had been thrown overboard, but finding it both hazardous to the horses and the men he concluded to give up the attempt to land the other horses in this way, and ordered the life boat hoisted up aboard. She had to be hoisted up the stern, in doing so a heavy wave struck and knocked it against the stern of the boat before she was clear of the water with such force as to endanger the lives of the Capt. and men in it, and some of the passengers were called on to assist in helping to hoist the life boat owing to its perilous position. Captain and the men were drenched to the skin, when they reached the deck. Capt. vented his rage in swearing at the hard luck and was so enraged that he did not change his wet clothing for some time afterward. The remaining horses were kept aboard to be delivered on the return trip, and the boat started for her point of destination La Point.

Arrived at La Point and Started in Employ of Brother Julius. 1851

Next morning we sighted land, which proved to be the outer island of the Apostle Group. Captain flew into the wheel room and found the wheelsman fast asleep. He grasped the wheel and steered the boat clear of the rocks, just in time to prevent the boat from striking. Captain lost no time in changing wheelsman. We arrived without further incidents at La Point the same afternoon. When she unloaded her cargo, work was at once begun transferring goods to the store, in which I assisted and thus began my regular business career. These goods were hauled to the store from the dock in a car, drawn by a horse, on wooden rails.

There were only about 6 white American inhabitants on the Island, about 50 Canadian Frenchmen who were married to squaws, and a number of full blooded Indians, among whom was chief Buffalo who was a descendant of chiefs & who was a good Indian and favorably regarded by the people.

Fr. Otto Skolla (self-portrait contained in History of the diocese of Sault Ste, Marie and Marquette (1906) by Antoine Ivan Rezek; pg.360; Digitized by Google Books)

The most conspicuous building in the place was an old Catholic Church which had been created more than 50 years before by some Austrian missionaries. This church contained some very fine and valuable paintings by old masters. The priest in charge there was Father Skolla, an Austrian, who himself was quite an artist, and spent his leisure hours in painting Holy pictures. The contributions to the church amounted to a mere pittance, and his consequent poverty allowed him the most meager and scant living. One Christmas he could not secure any candles to light up his church which made him feel very sad, my sister-in-law heard of this and sent me with a box of candles to him, which made him the happiest of mortals. When I handed them to him, his words were inadequate to express his gratitude and praise for my brother’s wife.

There was also a Methodist church of which a man by the name of Hall was the preacher. He had several sons and his family and my brother Julius and his wife were on friendly terms and often met.

The principle man of the place was Squire Bell, a very genial gentleman who held most of the offices of the town & county, such as Justice of the Peace & Supervisor. He also was married to a squaw. This was the fashion of that time, there being no other women there.

John W. Bell, “King of the Apostle Islands” as described by Benjamin Armstrong (Digitized by Google Books) .

John W. Bell, “King of the Apostle Islands” as described by Benjamin Armstrong (Digitized by Google Books) .There was a school in the place for the Indians and half breeds, there being no white children there at this time. I took lessons privately of the teacher of this school, his name was Pulsevor. I was anxious to perfect myself in English. I also picked up quite a bit of the Chippewa language and in very short time was able to understand enough to enable me to trade with the Indians.

My brother Julius was a very kind hearted man, of a very sympathetic and indulgent nature, and to his own detriment and loss he often trusted needy and hungry Indians for provisions and goods depending on their promise to return the following year with fur in payment for the goods. He was personally much liked and popular with the Indians, but his business with them was not a success as the fur often failed to materialize. The first morning after my arrival, my brother Julius handed me a milk pail and told me to go to the squaws next door, who having a cow, supplied the family with the article. He told me to ask for “Toto-Shapo” meaning in the Indian language, milk.

I repeated this to myself over and over again, and when I asked the squaw for “Toto Shapo” she and all the squaws screamed with delight and excitement to think that I had just arrived and could make myself understood in the Indian tongue. This fact was spread among the Indians generally and from that day on while I remained on the Island I was called “Toto Shapo.” One of the Indian characteristics is to name people and things by their first impression–for instance on seeing the first priest who work a black gown, they called him “Makada-Conyeh,” which means a black gown, and that is the only name retained in their language for priests. The first soldier who had a sword hanging by his side they called “Kitchie Mogaman” meaning “a big knife” in their language. The first steamboat they saw struck them as a house with fire escaping through the chimney, consequently they called it “Ushkutua wigwam” (Firehouse) which is also the only name in their language for steamboat. Whiskey they call “Ushkutua wawa” meaning “Fire Water.”

My brother Julius had the United States mail contract between La Point & St. Croix. The mail bag had to be taken by a man afoot between these two places via Bayfield a distance of about 125 miles, 2 miles of these being across the frozen lake from the Island to Bayfield.

Dangerous Crossing on the Ice.

An Indian named Kitchie (big) Inini (man) was hired to carry it. Once on the way on he started to cross on the ice but found it very unsafe and turned back. When my brother heard this, he made up his mind to see that the mail started on its way across the Lake no matter what the consequence. He took a rope about 25 ft. long tying one end around his body and the other about mine, and he and I each took a long light pole carrying it with two hands crosswise, which was to hold us up with in case we broke through the ice. Taking the mail bag on a small tobogan sled drawn by a dog, we started out with the Indian. When we had gone but a short way the ice was so bad that the Indian now thoroughly frightened turned back again, but my brother called me telling me not to pay any attention to him and we went straight on. This put him to shame and he finally followed us. We reached the other side in safety, but had found the crossing so dangerous, that we hesitated to return over it and thought best to wait until we could return by a small boat, but the time for this was so uncertain that after all we concluded to risk going back on the ice taking a shorter cut for the Island, and we were lucky to get back all right.

In the summer when the mail carrier returned from these trips, he would build a fire on the shore of the bay about 5 miles distant, as a signal to send a boat to bring him across to the Island. Once I remember my brother Julius not being at home when a signal was given. I with two young Indian boys (about 12 yrs. of age) started to cross over with the boat, when about two miles out a terrific thunder and hail storm sprang up suddenly. The hail stones were so large that it caused the boys to relax their hold on the oars and it was all I could do to keep them at the oars. I attempted to steer the boat back to the Island, and barely managed to reach there. The boat was over half full of water when we reached the shore. When I landed we were met by the boys’ mothers who were greatly incensed at my taking their boys on this perilous trip, nearly resulting in drowning them. They didn’t consider I had no idea of this terrible thunder storm which so suddenly came up and had I known it for my own safety would not dreamed of attempting the trip.

Nearly Capsize in a Small Boat.

Once I went out in a small sail boat with two Frenchmen to collect some barrels of fish near the Island at the fishing ground near La Point. We got two barrels of fish which they stood up on end, when a sudden gust of wind caused the boat to list to one side so that the barrels fell over on the side and nearly capsized the boat. By pulling the barrels up the boat was finally righted after being pretty well filled with water. I could not swim, and as a matter of self-preservation grabbed the Frenchman nearest me. He was furious, expressing his anger half in French and half in English, saying, “If I had drowned, I would have taken him with me.” which no doubt was true.

A Young Indian Locked up for Robbery

One day brother Julius went to the Indian payment. During his absence I with another employee, Henry Schmitz, were left in charge. A young Indian that night burglarized the store stealing some gold coins from the cash drawer. The same were offered to someone in the town next day who told me, which led to his detection. He admitted theft and was committed to jail by the Indian agent Mr. Watrous, which the Indians consider a great disgrace.

Some inquisitive boys peering through the window discovered that the young Indian had attempted to commit suicide and spread the alarm. His father was away at the time and his mother and friends were frenzied and their threats of vengeance were loud. The jailer was found but he had lost the key to the jail (the jail was in a log hut) the door of which was finally forced open with an axe, and the young culprit with his head bleeding was handed over to his people who revived him in their wigwam. The next day the money was returned and we and the authorities were glad to call it quits.

To be continued at La Pointe 1851-1852 (Part 2)…

Special thanks to Amorin Mello and Joseph Skulan for sharing this document and their important research on the Austrian brothers and their associates with me. It is to their credit that these stories see the light of day. The original handwritten memoir of Joseph Austrian is held by the Chicago History Museum.

Perrault, Curot, Nelson, and Malhoit

March 8, 2014

I’ve been getting lazy, lately, writing all my posts about the 1850s and later. It’s easy to find sources about that because they are everywhere, and many are being digitized in an archival format. It takes more work to write a relevant post about the earlier eras of Chequamegon History. The sources are sparse, scattered, and the ones that are digitized or published have largely been picked over and examined by other researchers. However, that’s no excuse. Those earlier periods are certainly as interesting as the mid-19th Century. I needed to just jump in and do a project of some sort.

I’m someone who needs to know the names and personalities involved to truly wrap my head around a history. I’ve never been comfortable making inferences and generalizations unless I have a good grasp of the specific. This doesn’t become easy in the Lake Superior country until after the Cass Expedition in 1820.

But what about a generation earlier?

The dawn of the 19th-century was a dynamic time for our region. The fur trade was booming under the British North West Company. The Ojibwe were expanding in all directions, especially to west, and many of familiar French surnames that are so common in the area arrived with Canadian and Ojibwe mix-blooded voyageurs. Admittedly, the pages of the written record around 1800 are filled with violence and alcohol, but that shouldn’t make one lose track of the big picture. Right or wrong, sustainable or not, this was a time of prosperity for many. I say this from having read numerous later nostalgic accounts from old chiefs and voyageurs about this golden age.

We can meet some of the bigger characters of this era in the pages of William W. Warren and Henry Schoolcraft. In them, men like Mamaangazide (Mamongazida “Big Feet”) and Michel Cadotte of La Pointe, Beyazhig (Pay-a-jick “Lone Man) of St. Croix, and Giishkiman (Keeshkemun “Sharpened Stone”) of Lac du Flambeau become titans, covered with glory in trade, war, and influence. However, there are issues with these accounts. These two authors, and their informants, are prone toward glorifying their own family members. Considering that Schoolcraft’s (his mother-in law, Ozhaawashkodewike) and Warren’s (Flat Mouth, Buffalo, Madeline and Michel Cadotte Jr., Jean Baptiste Corbin, etc.) informants were alive and well into adulthood by 1800, we need to keep things in perspective.

The nature of Ojibwe leadership wasn’t different enough in that earlier era to allow for a leader with any more coercive power than that of the chiefs in 1850s. Mamaangazide and his son Waabojiig may have racked up great stories and prestige in hunting and war, but their stature didn’t get them rich, didn’t get them out of performing the same seasonal labors as the other men in the band, and didn’t guarantee any sort of power for their descendants. In the pages of contemporary sources, the titans of Warren and Schoolcraft are men.

Finally, it should be stated that 1800 is comparatively recent. Reading the journals and narratives of the Old North West Company can make one feel completely separate from the American colonization of the Chequamegon Region in the 1840s and ’50s. However, they were written at a time when the Americans had already claimed this area for over a decade. In fact, the long knife Zebulon Pike reached Leech Lake only a year after Francois Malhoit traded at Lac du Flambeau.

The Project

I decided that if I wanted to get serious about learning about this era, I had to know who the individuals were. The most accessible place to start would be four published fur-trade journals and narratives: those of Jean Baptiste Perrault (1790s), George Nelson (1802-1804), Michel Curot (1803-1804), and Francois Malhoit (1804-1805).

The reason these journals overlap in time is that these years were the fiercest for competition between the North West Company and the upstart XY Company of Sir Alexander MacKenzie. Both the NWC traders (such as Perrault and Malhoit) and the XY traders (Nelson and Curot) were expected to keep meticulous records during these years.

I’d looked at some of these journals before and found them to be fairly dry and lacking in big-picture narrative history. They mostly just chronicle the daily transactions of the fur posts. However, they do frequently mention individual Ojibwe people by name, something that can be lacking in other primary records. My hope was that these names could be connected to bands and villages and then be cross-referenced with Warren and Schoolcraft to fill in some of the bigger story. As the project took shape, it took the form of a map with lots of names on it. I recorded every Ojibwe person by name and located them in the locations where they met the traders, unless they are mentioned specifically as being from a particular village other than where they were trading.

I started with Perrault’s Narrative and tried to record all the names the traders and voyageurs mentioned as well. As they were mobile and much less identified with particular villages, I decided this wasn’t worth it. However, because this is Chequamegon History, I thought I should at least record those “Frenchmen” (in quotes because they were British subjects, some were English speakers, and some were mix-bloods who spoke Ojibwe as a first language) who left their names in our part of the world. So, you’ll see Cadotte, Charette, Corbin, Roy, Dufault (DeFoe), Gauthier (Gokee), Belanger, Godin (Gordon), Connor, Bazinet (Basina), Soulierre, and other familiar names where they were encountered in the journals. I haven’t tried to establish a complete genealogy for either, but I believe Perrault (Pero) and Malhoit (Mayotte) also have names that are still with us.

For each of the names on the map, I recorded the narrative or journal they appeared in:

JBP= Jean Baptiste Perrault

GN= George Nelson

MC= Michel Curot

FM= Francois Malhoit

Red Lake-Pembina area: By this time, the Ojibwe had started to spread far beyond the Lake Superior forests and into the western prairies. Perrault speaks of the Pillagers (Leech Lake Band) being absent from their villages because they had gone to hunt buffalo in the west. Vincent Roy Sr. and his sons later settled at La Pointe, but their family maintained connections in the Canadian borderlands. Jean Baptiste Cadotte Jr. was the brother of Michel Cadotte (Gichi-Mishen), the famous La Pointe trader.

Leech Lake and Sandy Lake area: The names that jump out at me here are La Brechet or Gaa-dawaabide (Broken Tooth), the great Loon-clan chief from Sandy Lake (son of Bayaaswaa mentioned in this post) and Loon’s Foot (Maangozid). The Maangozid we know as the old speaker and medicine man from Fond du Lac (read this post) was the son of Gaa-dawaabide. He would have been a teenager or young man at the time Perrault passed through Sandy Lake.

Fond du Lac and St. Croix: Augustin Belanger and Francois Godin had descendants that settled at La Pointe and Red Cliff. Jean Baptiste Roy was the father of Vincent Roy Sr. I don’t know anything about Big Marten and Little Marten of Fond du Lac or Little Wolf of the St. Croix portage, but William Warren writes extensively about the importance of the Marten Clan and Wolf Clan in those respective bands. Bayezhig (Pay-a-jick) is a celebrated warrior in Warren and Giishkiman (Kishkemun) is credited by Warren with founding the Lac du Flambeau village. Buffalo of the St. Croix lived into the 1840s. I wrote about his trip to Washington in this post.

Lac Courte Oreilles and Chippewa River: Many of the men mentioned at LCO by Perrault are found in Warren. Little (Petit) Michel Cadotte was a cousin of the La Pointe trader, Big (Gichi/La Grande) Michel Cadotte. The “Red Devil” appears in Schoolcraft’s account of 1831. The old, respected Lac du Flambeau chief Giishkiman appears in several villages in these journals. As the father of Keenestinoquay and father-in-law of Simon Charette, a fur-trade power couple, he traded with Curot and Nelson who worked with Charette in the XY Company.

La Pointe: Unfortunately, none of the traders spent much time at La Pointe, but they all mention Michel Cadotte as being there. The family of Gros Pied (Mamaangizide, “Big Feet”) the father of Waabojiig, opened up his lodge to Perrault when the trader was waylaid by weather. According to Schoolcraft and Warren, the old war chief had fought for the French on the Plains of Abraham in 1759.

Lac du Flambeau: Malhoit records many of the same names in Lac du Flambeau that Nelson met on the Chippewa River. Simon Charette claimed much of the trade in this area. Mozobodo and “Magpie” (White Crow), were his brothers-in-law. Since I’ve written so much about chiefs named Buffalo, I should point out that there’s an outside chance Le Taureau (presumably another Bizhiki) could be the famous Chief Buffalo of La Pointe.

L’Anse, Ontonagon, and Lac Vieux Desert: More Cadottes and Roys, but otherwise I don’t know much about these men.

At Mackinac and the Soo, Perrault encountered a number of names that either came from “The West,” or would find their way there in later years. “Cadotte” is probably Jean Baptiste Sr., the father of “Great” Michel Cadotte of La Pointe.

Malhoit meets Jean Baptiste Corbin at Kaministiquia. Corbin worked for Michel Cadotte and traded at Lac Courte Oreilles for decades. He was likely picking up supplies for a return to Wisconsin. Kaministiquia was the new headquarters of the North West Company which could no longer base itself south of the American line at Grand Portage.

Initial Conclusions

There are many stories that can be told from the people listed in these maps. They will have to wait for future posts, because this one only has space to introduce the project. However, there are two important concepts that need to be mentioned. Neither are new, but both are critical to understanding these maps:

1) There is a great potential for misidentifying people.

Any reading of the fur-trade accounts and attempts to connect names across sources needs to consider the following:

- English names are coming to us from Ojibwe through French. Names are mistranslated or shortened.

- Ojibwe names are rendered in French orthography, and are not always transliterated correctly.

- Many Ojibwe people had more than one name, had nicknames, or were referenced by their father’s names or clan names rather than their individual names.

- Traders often nicknamed Ojibwe people with French phrases that did not relate to their Ojibwe names.

- Both Ojibwe and French names were repeated through the generations. One should not assume a name is always unique to a particular individual.

So, if you see a name you recognize, be careful to verify it’s reall the person you’re thinking of. Likewise, if you don’t see a name you’d expect to, don’t assume it isn’t there.

2) When talking about Ojibwe bands, kinship is more important than physical location.

In the later 1800s, we are used to talking about distinct entities called the “St. Croix Band” or “Lac du Flambeau Band.” This is a function of the treaties and reservations. In 1800, those categories are largely meaningless. A band is group made up of a few interconnected families identified in the sources by the names of their chiefs: La Grand Razeur’s village, Kishkimun’s Band, etc. People and bands move across large areas and have kinship ties that may bind them more closely to a band hundreds of miles away than to the one in the next lake over.

I mapped here by physical geography related to trading posts, so the names tend to group up. However, don’t assume two people are necessarily connected because they’re in the same spot on the map.

On a related note, proximity between villages should always be measured in river miles rather than actual miles.

Going Forward

I have some projects that could spin out of these maps, but for now, I’m going to set them aside. Please let me know if you see anything here that you think is worth further investigation.

Sources:

Curot, Michel. A Wisconsin Fur Trader’s Journal, 1803-1804. Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites. Wisconsin Historical Collections, vol. XX: 396-472, 1911.

Malhoit, Francois V. “A Wisconsin Fur Trader’s Journal, 1804-05.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Reuben Gold Thwaites. Vol. 19. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1910. 163-225. Print.

Nelson, George, Laura L. Peers, and Theresa M. Schenck. My First Years in the Fur Trade: The Journals of 1802-1804. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 2002. Print.

Perrault, Jean Baptiste. Narrative of The Travels And Adventures Of A Merchant Voyager In The Savage Territories Of Northern America Leaving Montreal The 28th of May 1783 (to 1820) ed. and Introduction by, John Sharpless Fox. Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections. vol. 37. Lansing: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, Crawford Co., 1900.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Information Respecting The History,Condition And Prospects OF The Indian Tribes Of The United States. Illustrated by Capt. S. Eastman. Published by the Authority of Congress. Part III. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Company, 1953.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi. East Lansing: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Photos, Photos, Photos

February 10, 2014

The queue of Chequamegon History posts that need to be written grows much faster than my ability to write them. Lately, I’ve been backed up with mysteries surrounding a number of photographs. Many of these photos are from after 1860, so they are technically outside the scope of this website (though they involve people who were important in the pre-1860 era too.

Photograph posts are some of the hardest to write, so I decided to just run through all of them together with minimal commentary other than that needed to resolve the unanswered questions. I will link all the photos back to their sources where their full descriptions can be found. Here it goes, stream-of-consciousness style:

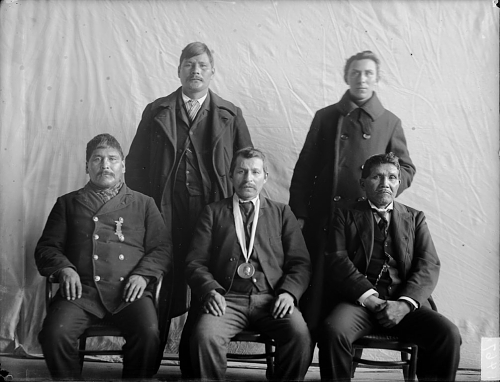

Ojibwa Delegation by C.M. Bell. Washington D.C. 1880 (NMAI Collections)

This whole topic started with a photo of a delegation of Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs that sits on the windowsill of the Bayfield Public Library. Even though it is clearly after 1860, some of the names in the caption: Oshogay, George Warren, and Vincent Roy Jr. caught my attention. These men, looking past their prime, were all involved in the politics of the 1850s that I had been studying, so I wanted to find out more about the picture.

As I mentioned in the Oshogay post, this photo is also part of the digital collections of the Smithsonian, but the people are identified by different names. According to the Smithsonian, the picture was taken in Washington in 1880 by the photographer C.M. Bell.

I found a second version of this photo as well. If it wasn’t for one of the chiefs in front, you’d think it was the same picture:

While my heart wanted to believe the person, probably in the early 20th century, who labelled the Bayfield photograph, my head told me the photographer probably wouldn’t have known anything about the people of Lake Superior, and therefore could only have gotten the chiefs’ names directly from them. Plus, Bell took individual photos:

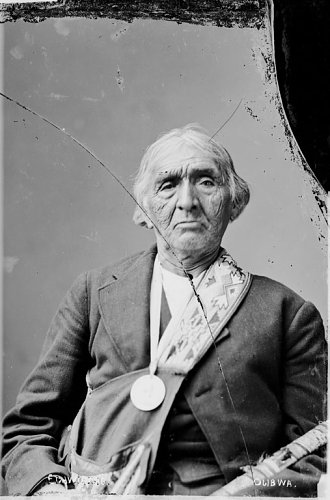

Edawigijig (Edawi-giizhig “Both Sides of the Sky”), Bad River chief and signer of the Treaty of 1854 (C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections)

Niizhogiizhig: “Second Day,” (C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections)

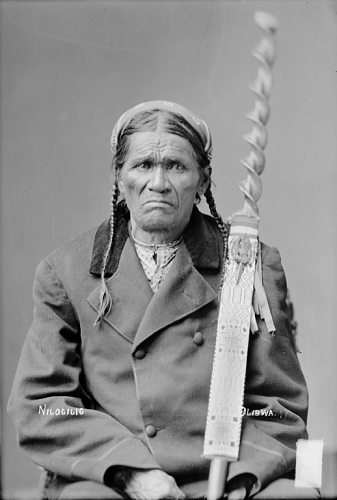

Kiskitawag (Giishkitawag: “Cut Ear”) signed multiple treaties as a warrior of the Ontonagon Band but afterwards was associated with the Bad River Band (C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections).

By cross-referencing the individual photos with the names listed with the group photo, you can identify nine of the thirteen men. They are chiefs from Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, and Lac du Flambeau.

According to this, the man identified by the library caption as Vincent Roy Jr., was in fact Ogimaagiizhig (Sky Chief). He does have a resemblance to Roy, so I’ll forgive whoever it was, even if it means having to go back and correct my Vincent Roy post:

According to this, the man identified by the library caption as Vincent Roy Jr., was in fact Ogimaagiizhig (Sky Chief). He does have a resemblance to Roy, so I’ll forgive whoever it was, even if it means having to go back and correct my Vincent Roy post:

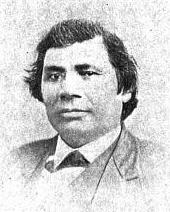

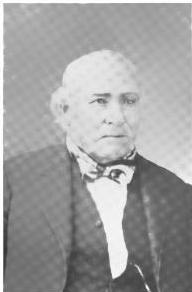

Vincent Roy Jr. From C. Verwyst’s Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, First Bishop of Marquette, Mich: To which are Added Short Sketches of the Lives and Labors of Other Indian Missionaries of the Northwest (Digitized by Google Books)

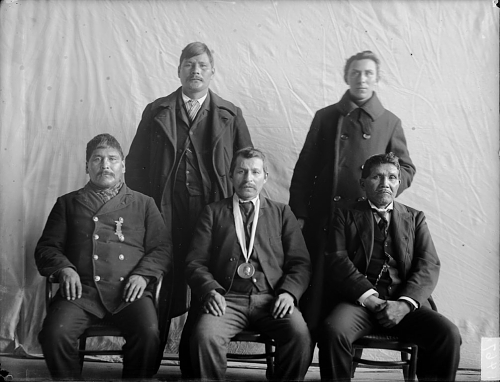

Top: Frank Roy, Vincent Roy, E. Roussin, Old Frank D.o., Bottom: Peter Roy, Jos. Gourneau (Gurnoe), D. Geo. Morrison. The photo is labelled Chippewa Treaty in Washington 1845 by the St. Louis Hist. Lib and Douglas County Museum, but if it is in fact in Washington, it was probably the Bois Forte Treaty of 1866, where these men acted as conductors and interpreters (Digitized by Mary E. Carlson for The Sawmill Community at Roy’s Point).

So now that we know who went on the 1880 trip, it begs the question of why they went. The records I’ve found haven’t been overly clear, but it appears that it involved a bill in the senate for “severalty” of the Ojibwe reservations in Wisconsin. A precursor to the 1888 Allotment Act of Senator Henry Dawes, this legislation was proposed by Senator Thaddeus C. Pound of Wisconsin. It would divide the reservations into parcels for individual families and sell the remaining lands to the government, thereby greatly reducing the size of the reservations and opening the lands up for logging.

Pound spent a lot of time on Indian issues and while he isn’t as well known as Dawes or as Richard Henry Pratt the founder of the Carlisle Indian School, he probably should be. Pound was a friend of Pratt’s and an early advocate of boarding schools as a way to destroy Native cultures as a way to uplift Native peoples.

I’m sure that Pound’s legislation was all written solely with the welfare of the Ojibwe in mind, and it had nothing to do with the fact that he was a wealthy lumber baron from Chippewa Falls who was advocating damming the Chippewa River (and flooding Lac Courte Oreilles decades before it actually happened). All sarcasm aside, if any American Indian Studies students need a thesis topic, or if any L.C.O. band members need a new dartboard cover, I highly recommend targeting Senator Pound.

Like many self-proclaimed “Friends of the Indian” in the 1880s, Senator Thaddeus C. Pound of Wisconsin thought the government should be friendly to Indians by taking away more of their land and culture. That he stood to make a boatload of money out of it was just a bonus (Brady & Handy: Wikimedia Commons).

While we know Pound’s motivations, it doesn’t explain why the chiefs came to Washington. According to the Indian Agent at Bayfield they were brought in to support the legislation. We also know they toured Carlisle and visited the Ojibwe students there. There are a number of potential explanations, but without having the chiefs’ side of the story, I hesitate to speculate. However, it does explain the photograph.

Now, let’s look at what a couple of these men looked like two decades earlier:

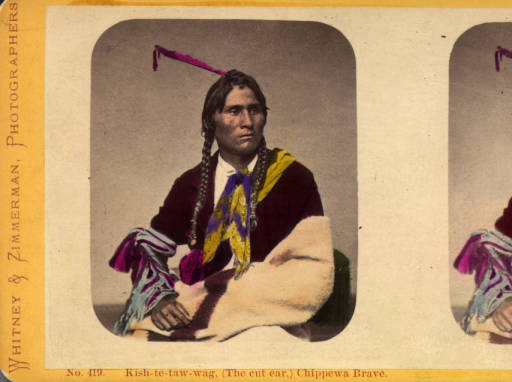

This stereocard of Giishkitawag was produced in the early 1870s, but the original photo was probably taken in the early 1860s (Denver Public Library).

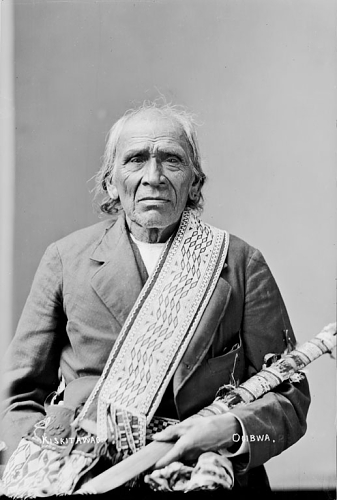

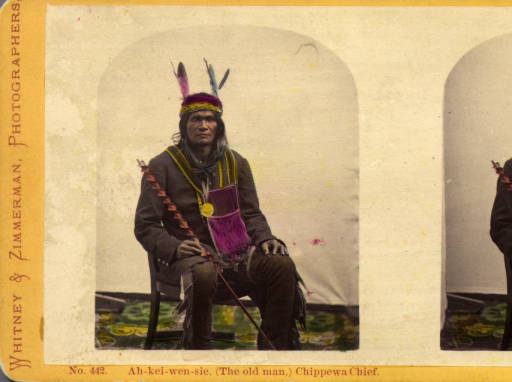

By the mid 1850s, Akiwenzii (Old Man) was the most prominent chief of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band. This stereocard was made by Whitney and Zimmerman c.1870 from an original possibly by James E. Martin in the late 1850s or early 1860s (Denver Public Library).

Giishkitawag and Akiwenzii are seem to have aged quite a bit between the early 1860s, when these photos were taken, and 1880 but they are still easily recognized. The earlier photos were taken in St. Paul by the photographers Joel E. Whitney and James E. Martin. Their galleries, especially after Whitney partnered with Charles Zimmerman, produced hundreds of these images on cards and stereoviews for an American public anxious to see real images of Indian leaders.

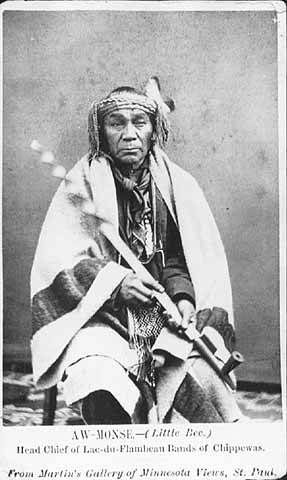

Giishkitawag and Akiwenzii were not the only Lake Superior chiefs to end up on these souvenirs. Aamoons (Little Bee), of Lac du Flambeau appears to have been a popular subject:

Aamoons (Little Bee) was a prominent chief from Lac du Flambeau (Denver Public Library).

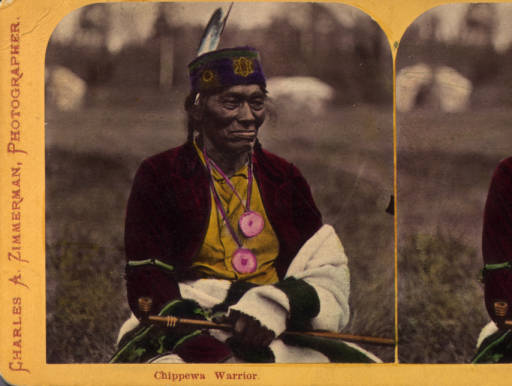

As the images were reproduced throughout the 1870s, it appears the studios stopped caring who the photos were actually depicting:

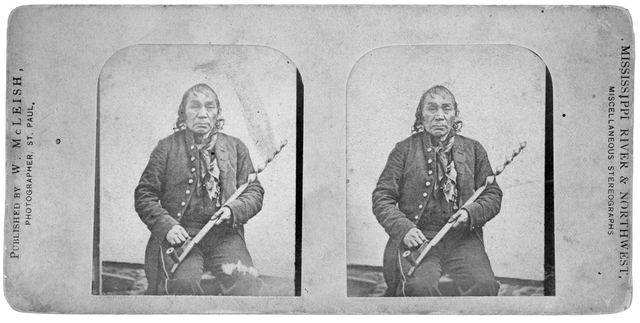

One wonders what the greater insult to Aamoons was: reducing him to being simply “Chippewa Brave” as Whitney and Zimmerman did here, or completely misidentifying him as Na-gun-ub (Naaganab) as a later stereo reproduction as W. M. McLeish does here:

Chief identified as Na-gun-ub (Minnesota Historical Society)

Aamoons and Naaganab don’t even look alike…

Naaganab (Minnesota Historical Society)

…but the Lac du Flambeau and Fond du Lac chiefs were probably photographed in St. Paul around the time they were both part of a delegation to President Lincoln in 1862.

Chippewa Delegation 1862 by Matthew Brady? (Minnesota Historical Society)

Naaganab (seated middle) and Aamoons (back row, second from left) are pretty easy to spot, and if you look closely, you’ll see Giishkitawag, Akiwenzii, and a younger Edawi-giizhig (4th, 5th, and 6th from left, back row) were there too. I can’t find individual photos of the other chiefs, but there is a place we can find their names.

Benjamin Armstrong, who interpreted for the delegation, included a version of the image in his memoir Early Life Among the Indians. He identifies the men who went with him as:

Ah-moose (Little Bee) from Lac Flambeau Reservation, Kish-ke-taw-ug (Cut Ear) from Bad River Reservation, Ba-quas (He Sews) from Lac Courte O’Rielles Reservation, Ah-do-ga-zik (Last Day) from Bad River Reservation, O-be-quot (Firm) from Fond du Lac Reservation, Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation, Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell) from La Pointe Reservation, Na-gon-ab (He Sits Ahead) from Fond du Lac Reservation, and O-ma-shin-a-way (Messenger) from Bad River Reservation.

It appears that Armstrong listed the men according to their order in the photograph. He identifies Akiwenzii as “Ba-quas (He Sews),” which until I find otherwise, I’m going to assume the chief had two names (a common occurrence) since the village is the same. Aamoons, Giishkitawag, Edawi-giizhig and Naaganab are all in the photograph in the places corresponding to the order in Armstrong’s list. That means we can identify the other men in the photo.

I don’t know anything about O-be-quot from Fond du Lac (who appears to have been moved in the engraving) or S[h]ing-guak-onse from Red Cliff (who is cut out of the photo entirely) other than the fact that the latter shares a name with a famous 19th-century Sault Ste. Marie chief. Travis Armstrong’s outstanding website, chiefbuffalo.com, has more information on these chiefs and the mission of the delegation.

Seated to the right of Naaganab, in front of Edawi-giizhig is Omizhinawe, the brother of and speaker for Blackbird of Bad River. Finally, the broad-shouldered chief on the bottom left is “Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell)” from Red Cliff. This is Jajigwyong, the son of Chief Buffalo, who signed the treaties as a chief in his own right. Jayjigwyong, sometimes called Little Chief Buffalo, was known for being an early convert to Catholicism and for encouraging his followers to dress in European style. Indeed, we see him and the rest of the chiefs dressed in buttoned coats and bow-ties and wearing their Lincoln medals.

Wait a minute… button coats?… bow-ties?… medals?…. a chief identified as Buffalo…That reminds me of…

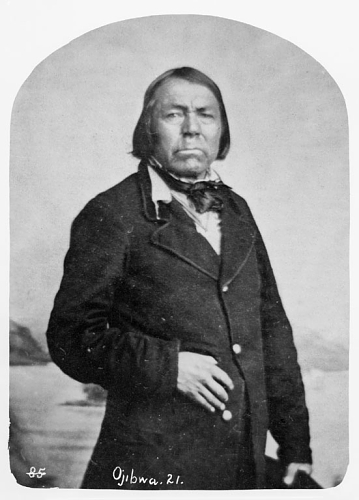

This image is generally identified as Chief Buffalo (Wikimedia Commons)

Anyway, with that mystery solved, we can move on to the next one. It concerns a photograph that is well-known to any student of Chequamegon-area history in the mid 19th century (or any Chequamegon History reader who looks at the banners on the side of this page).Noooooo!!!!!!! I’ve been trying to identify the person in The above “Chief Buffalo” photo for years, and the answer was in Armstrong all along! Now I need to revise this post among others. I had already begun to suspect it was Jayjigwyong rather than his father, but my evidence was circumstantial. This leaves me without a doubt. This picture of the younger Chief Buffalo, not his more-famous father.

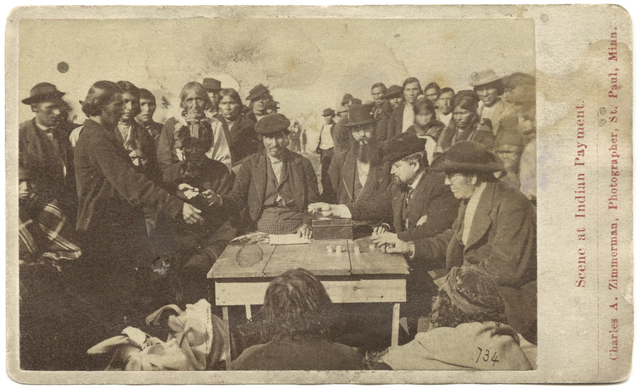

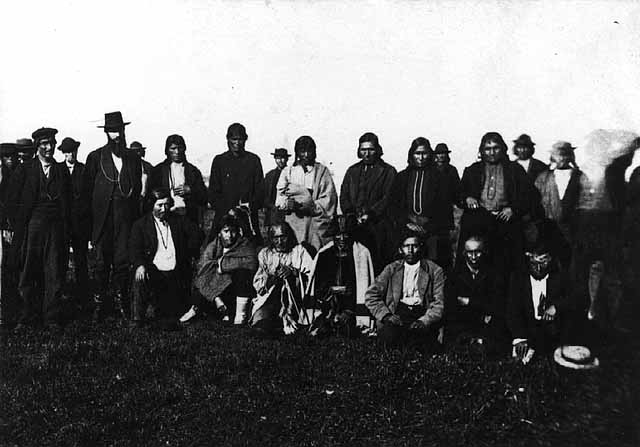

The photo showing an annuity payment, must have been widely distributed in its day, because it has made it’s way into various formats in archives and historical societies around the world. It has also been reproduced in several secondary works including Ronald Satz’ Chippewa Treaty Rights, Patty Loew’s Indian Nations of Wisconsin, Hamilton Ross’ La Pointe: Village Outpost on Madeline Island, and in numerous other pamphlets, videos, and displays in the Chequamegon Region. However, few seem to agree on the basic facts:

When was it taken?

Where was it taken?

Who was the photographer?

Who are the people in the photograph?

We’ll start with a cropped version that seems to be the most popular in reproductions:

According to Hamilton Ross and the Wisconsin Historical Society: “Annuity Payment at La Pointe: Indians receiving payment. Seated on the right is John W. Bell. Others are, left to right, Asaph Whittlesey, Agent Henry C. Gilbert, and William S. Warren (son of Truman Warren).” 1870. Photographer Charles Zimmerman (more info).

In the next one, we see a wider version of the image turned into a souvenir card much like the ones of the chiefs further up the post:

According to the Minnesota Historical Society “Scene at Indian payment, Wisconsin; man in black hat, lower right, is identified as Richard Bardon, Superior, Wisconsin, then acting Indian school teacher and farmer” c.1871 by Charles Zimmerman (more info).

In this version, we can see more foreground and the backs of the two men sitting in front.

According to the Library of Congress: “Cherokee payments(?). Several men seated around table counting coins; large group of Native Americans stand in background.” Published 1870-1900 (more info).

The image also exists in engraved forms, both slightly modified…

According to Benjamin Armstrong: “Annuity papment [sic] at La Pointe 1852” (From Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians)

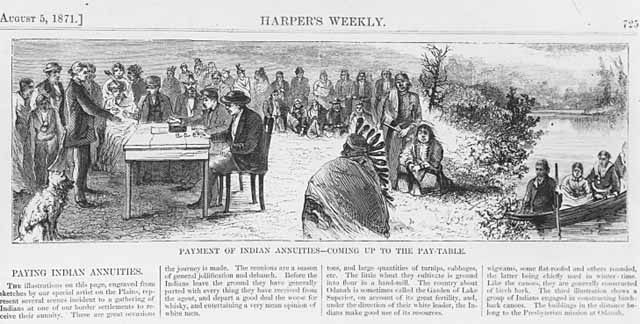

…and greatly-modified.

Harper’s Weekly August 5, 1871: “Payment of Indian Annuities–Coming up to the Pay Table.” (more info)

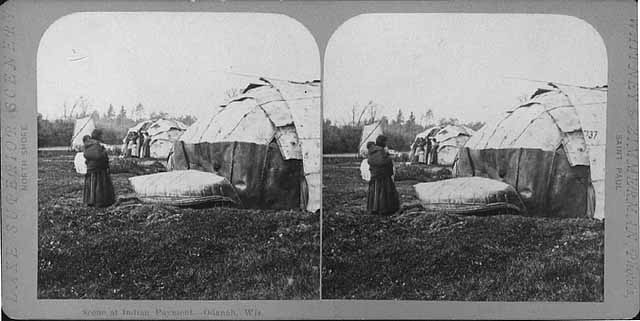

It should also be mentioned that another image exists that was clearly taken on the same day. We see many of the same faces in the crowd:

Scene at Indian payment, probably at Odanah, Wisconsin. c.1865 by Charles Zimmerman (more info)

We have a lot of conflicting information here. If we exclude the Library of Congress Cherokee reference, we can be pretty sure that this is an annuity payment at La Pointe or Odanah, which means it was to the Lake Superior Ojibwe. However, we have dates ranging from as early as 1852 up to 1900. These payments took place, interrupted from 1850-1852 by the Sandy Lake Removal, from 1837 to 1874.

Although he would have attended a number of these payments, Benjamin Armstrong’s date of 1852, is too early. A number of secondary sources have connected this photo to dates in the early 1850s, but outside of Armstrong, there is no evidence to support it.

Charles Zimmerman, who is credited as the photographer when someone is credited, became active in St. Paul in the late 1860s, which would point to the 1870-71 dates as more likely. However, if you scroll up the page and look at Giishkitaawag, Akiwenzii, and Aamoons again, you’ll see that these photos, (taken in the early 1860s) are credited to “Whitney & Zimmerman,” even though they predate Zimmerman’s career.

What happened was that Zimmerman partnered with Joel Whitney around 1870, eventually taking over the business, and inherited all Whitney’s negatives (and apparently those of James Martin as well). There must have been an increase in demand for images of Indian peoples in the 1870s, because Zimmerman re-released many of the earlier Whitney images.

So, we’re left with a question. Did Zimmerman take the photograph of the annuity payment around 1870, or did he simply reproduce a Whitney negative from a decade earlier?

I had a hard time finding any primary information that would point to an answer. However, the Summer 1990 edition of the Minnesota History magazine includes an article by Bonnie G. Wilson called Working the Light: Nineteenth Century Professional Photographers in Minnesota. In this article, we find the following:

“…Zimmerman was not a stay-at-home artist. He took some of his era’s finest landscape photos of Minnesota, specializing in stereographs of the Twin Cities area, but also traveling to Odanah, Wisconsin for an Indian annuity payment…”

In the footnotes, Wilson writes:

“The MHS has ten views in the Odanah series, which were used as a basis for engravings in Harper’s Weekly, Aug. 5, 1871. See also Winona Republican, Oct. 12, 1869 p.3;”

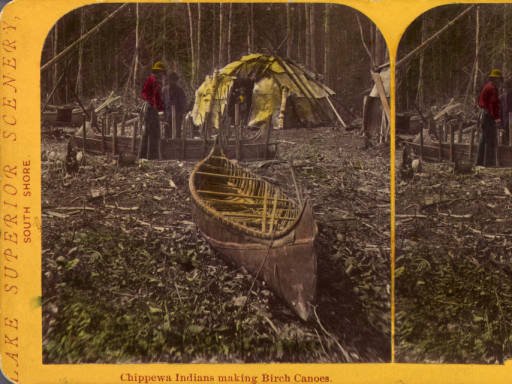

Not having access to the Winona Republican, I tried to see how many of the “Odanah series” I could track down. Zimmerman must have sold a lot of stereocards, because this task was surprisingly easy. Not all are labelled as being in Odanah, but the backgrounds are similar enough to suggest they were all taken in the same place. Click on them to view enlarged versions at various digital archives.

Scene at Indian Payment, Odanah Wisconsin (Minnesota Historical Society)

Chippewa Wedding (British Museum)

Domestic Life–Chippewa Indians (British Museum)

Chippewa Wedding (British Museum)

Finally…

So, if Zimmerman took the “Odanah series” in 1869, and the pay table image is part of it, then this is a picture of the 1869 payment. To be absolutely certain, we should try to identify the men in the image.

This task is easier than ever because the New York Public Library has uploaded a high-resolution scan of the Whitney & Zimmerman stereocard version to Wikimedia Commons. For the first time, we can really get a close look at the men and women in this photo.

They say a picture tells a thousand words. I’m thinking I could write ten-thousand and still not say as much as the faces in this picture.

To try to date the photo, I decided to concentrate the six most conspicuous men in the photo:

1) The chief in the fur cap whose face in the shadows.

2) The gray-haired man standing behind him.

3) The man sitting behind the table who is handing over a payment.

4) The man with the long beard, cigar, and top hat.

5) The man with the goatee looking down at the money sitting to the left of the top-hat guy (to the right in our view)

6) The man with glasses sitting at the table nearest the photographer

According to Hamilton Ross, #3 is Asaph Whittlesey, #4 is Agent Henry Gilbert, #5 is William S. Warren (son of Truman), and #6 is John W. Bell. While all four of those men could have been found at annuity payments as various points between 1850 and 1870, this appears to be a total guess by Ross. Three of the four men appear to be of at least partial Native descent and only one (Warren) of those identified by Ross was Ojibwe. Chronologically, it doesn’t add up either. Those four wouldn’t have been at the same table at the same time. Additionally, we can cross-reference two of them with other photos.

Asaph Whittlesey was an interesting looking dude, but he’s not in the Zimmerman photo (Wisconsin Historical Society).

Henry C. Gilbert was the Indian Agent during the Treaty of 1854 and oversaw the 1855 annuity payment, but he was dead by the time the “Zimmerman” photo was taken (Branch County Photographs)

Whittlesey and Gilbert are not in the photograph.

The man who I label as #5 is identified by Ross as William S. Warren. This seems like a reasonable guess, though considering the others, I don’t know that it’s based on any evidence. Warren, who shares a first name with his famous uncle William Whipple Warren, worked as a missionary in this area.

The man I label #6 is called John W. Bell by Ross and Richard Bardon by the Minnesota Historical Society. I highly doubt either of these. I haven’t found photos of either to confirm, but the Ireland-born Bardon and the Montreal-born Bell were both white men. Mr. 6 appears to be Native. I did briefly consider Bell as a suspect for #4, though.

Neither Ross nor the Minnesota Historical Society speculated on #1 or #2.

At this point, I cannot positively identify Mssrs. 1, 2, 3, 5, or 6. I have suspicions about each, but I am not skilled at matching faces, so these are wild guesses at this point:

#1 is too covered in shadows for a clear identification. However, the fact that he is wearing the traditional fur headwrap of an Ojibwe civil chief, along with a warrior’s feather, indicates that he is one of the traditional chiefs, probably from Bad River but possibly from Lac Courte Oreilles or Lac du Flambeau. I can’t see his face well enough to say whether or not he’s in one of the delegation photos from the top of the post.

#2 could be Edawi-giizhig (see above), but I can’t be certain.

#3 is also tricky. When I started to examine this photo, one of the faces I was looking for was that of Joseph Gurnoe of Red Cliff. You can see him in a picture toward the top of the post with the Roy brothers. Gurnoe was very active with the Indian Agency in Bayfield as a clerk, interpreter, and in other positions. Comparing the two photos I can’t say whether or not that’s him. Leave a comment if you think you know.

#5 could be a number of different people.

#6 I don’t have a solid guess on either. His apparent age, and the fact that the Minnesota Historical Society’s guess was a government farmer and schoolteacher, makes me wonder about Henry Blatchford. Blatchford took over the Odanah Mission and farm from Leonard Wheeler in the 1860s. This was after spending decades as Rev. Sherman Hall’s interpreter, and as a teacher and missionary in La Pointe and Odanah area. When this photo was taken, Blatchford had nearly four decades of experience as an interpreter for the Government. I don’t have any proof that it’s him, but he is someone who is easy to imagine having a place at the pay table.

Finally, I’ll backtrack to #4, whose clearly identifiable gray-streaked beard allows us to firmly date the photo. The man is Col. John H. Knight, who came to Bayfield as Indian Agent in 1869.

Col. John H. Knight (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Knight oversaw a couple of annuity payments, but considering the other evidence, I’m confident that the popular image that decorates the sides of the Chequamegon History site was indeed taken at Odanah by Charles Zimmerman at the 1869 annuity payment.

Do you agree? Do you disagree? Have you spotted anything in any of these photos that begs for more investigation? Leave a comment.

As for myself, it’s a relief to finally get all these photo mysteries out of my post backlog. The 1870 date on the Zimmerman photo reminds me that I’m spending too much time in the later 19th century. After all, the subtitle of this website says it’s history before 1860. I think it might be time to go back for a while to the days of the old North West Company or maybe even to Pontiac. Stay tuned, and thanks for reading,

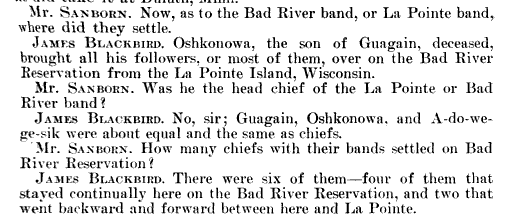

Blackbird’s Speech at the 1855 Payment

January 20, 2014

“We sold our land for our graves–that we might have a home, where the bones of our fathers are buried. We were not willing to sell the ashes of our relatives which are so dear to us. This was the reason why we sold our lands. It was not to pay debts over and over again, but to benefit the living, those of us who yet remain upon earth, our young men & women & children.”

~Makade-binesi (Blackbird)

Scene at Indian Payment–Odanah, Wis. This image is from a later payment than the one described below (Whitney & Zimmerman c.1870)

Most of us have heard Chief Joseph’s “Fight No More Forever” speech and Chief Seattle’s largely-fictional plea for the environment, but very few will know that a outstanding example of Native American oratory took place right here in the Chequamegon Region in the summer of 1855.

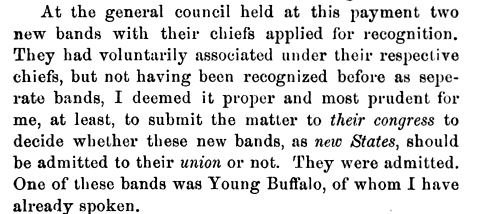

It was exactly eleven months after the Lake Superior Ojibwe bands gave up the Arrowhead region of Minnesota, in their final treaty with the United States, in exchange for permanent reservations. Already, the American government was trying to back out of a key provision of the agreement. It concerned a clause in Article Four of the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe that reads:

The United States will also pay the further sum of ninety thousand dollars, as the chiefs in open council may direct, to enable them to meet their present just engagements.

The inclusion of clauses to pay off trade debts was nothing new in Ojibwe treaties. In 1837, $70,000 went to pay off debts, and in 1842 another $75,000 went to the traders. Personal debts would often be paid out of annuity funds by the government directly to the creditors and certain Ojibwe families would never see their money. However, from the beginning there were accusations that these debts were inflated or illegitimate, and that it was the traders rather than the Ojibwe themselves, who profited from the sale of the lands. Therefore, in 1854, when $90,000 in claims were inserted in the treaty, the chiefs demanded that they be the ones to address the claims of the creditors.

However, less than a year later, at the first post-1854 payment, the government was pressured to back off of the language in the treaty. George Manypenny, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, came to La Pointe to oversee the payment where he was asked by Indian Agent Henry Gilbert to let the Agency oversee the disbursement of the $90,000. Most white inhabitants, and many of the white tourists in town to view the spectacle that was the 1855 payment, supported the agent’s plan, as did most of the mix-blooded Ojibwe (most of whom were employed in the trading business in one way or another) and a substantial minority of the full-bloods.

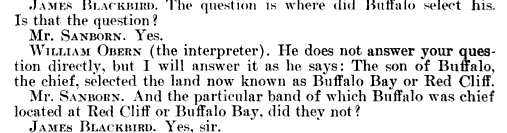

However, the clear majority of the Lake Superior chiefs insisted they keep the right to handle their own debt claims. As we saw in this post, the Odanah-based missionary Leonard Wheeler also felt the Government needed to honor its treaties to the letter. This larger faction of Ojibwe rallied around one chief. He was from the La Pointe Band and was entrusted to speak for Ojibwe with one voice. From this description, you might assume it was Chief Buffalo. However, Buffalo, in the final days of his life, found himself in the minority on this issue. The speaker for the majority was the Bad River chief Blackbird, and he may have delivered one of the greatest speeches ever given in the Chequamegon Bay region.

Unfortunately, the Ojibwe version of the speech has not survived, and it’s English version, originally translated by Paul Bealieu, exists in pieces recorded by multiple observers. None of these accounts captures all the nuances of the speech, so it is necessary to read all of them and then analyze the different passages to see its true brilliance.

The first reference to Blackbird’s speech I remember seeing appeared in the eyewitness account of Dr. Richard F. Morse of Detroit who visited La Pointe that summer specifically to see the payment. His article, The Chippewas of Lake Superior appeared in the third volume of the Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. As you’ll read, it doesn’t speak very highly of Blackbird or the speech, celebrating instead the oratory of Naaganab, the Fond du Lac chief who was part of the minority faction and something of a celebrity among the visiting whites in 1855:

From Morse’s clear bias against Ojibwe culture, I thought there may have been more to this story, but my suspicions weren’t confirmed until I transcribed another account of the payment for Chequamegon History. An Indian Payment written by another eyewitness, Crocket McElroy, paints a different picture of Blackbird and quotes part of his speech:

Paul H. Beaulieu translated the speeches at the 1855 annuity payment (Minnesota Historical Society Collections).

In August 1855 about three thousand Chippewa Indians gathered at the village of Lapointe, on Lapointe Island, Lake Superior, for an Indian Payment and also to hold a council with the commissioner of Indian affairs, who at that time was George W. Monypenny of Ohio. The Indians selected for their orator a chief named Blackbird, and the choice was a good one, as Blackbird held his own well in a long discussion with the commissioner. Blackbird was not one of the haughty style of Indians, but modest in his bearing, with a good command of language and a clear head. In his speeches he showed much ingenuity and ably pleaded the cause of his people. He spoke in Chippewa stopping frequently to give the interpreter time to translate what he said into English. In beginning his address he spoke substantially as follows:

“My great white father, we are pleased to meet you and have a talk with you We are friends and we want to remain friends. We expect to do what you want us to do, and we hope that you will deal kindly with us. We wish to remind you that we are the source from which you have derived all your riches. Our furs, our timber, our lands, everything that we have goes to you; even the gold out of which that chain was forged (pointing to a heavy watch chain that the commissioner carried) came from us, and now we hope that you will not use that chain to bind us.”

These conflicting accounts of the largely-unremembered Bad River chief’s speech made me curious, and after I found the Blackbird-Wheeler-Manypenny letters written after the payment, I knew I needed to learn more about the speech. Luckily, digging further into the Wheeler Papers uncovered the following. To my knowledge, this is the first time it has been transcribed or published in any form.

[Italics, line breaks, and quotation marks added by transcriber to clearly differentiate when Wheeler is quoting a speaker. Blackbird’s words are in blue.]

O-da-nah Jan 18, 1856.

L. H. Wheeler to Richard M. Smith

Dear Sir,

The following is the substance of my notes taken at the Indian council at La Pointe a copy of which you requested. Council held in front of Mr. Austrian’s store house Aug 30. 1855.

Short speech first from Kenistino of Lac du Flambeau.

My father, I have a little to say to you & to the Indians. There is no difference between myself and the other chiefs in regard to the subject upon which we wish to speak. Our chiefs and young men & old men & even the women & children are all of the same mind. Blackbird our chief will speak for us & express our sentiments.

The Commissioner, Col Manypenny replied as follows.

My children I suppose you have come to reply to what I said to you day before yesterday. Is this what you have come for?

“Ah;” or yes, was the reply.