Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Coda

June 1, 2024

My last post ended up containing several musings on the nature of primary-source research and how to acknowledge mistakes and deal with uncertainty in the historical record. This was in anticipation of having to write this post. It’s a post I’ve been putting off for years.

Amorin forced the issue with his important work on the speeches at the 1842 Treaty negotiations. While working on it, he sent me a message that read something like, “Hey, the article quotes Chief Buffalo and describes him in a blue military coat with epaulets. Is the world ready for that picture that Smithsonian guy sent us years ago?”

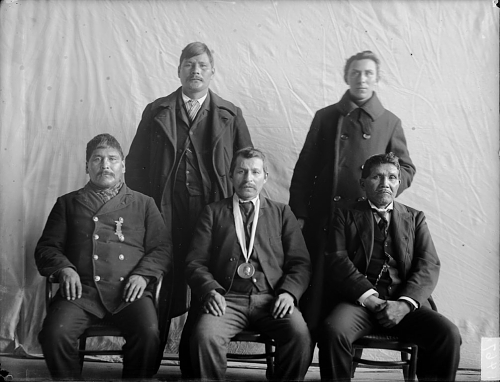

This was the image in question:

Henry Inman, Big Buffalo (Chippewa), 1832-1833, oil on canvas, frame: 39 in. × 34 in. × 2 1/4 in. (99.1 × 86.4 × 5.7 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Gerald and Kathleen Peters, 2019.12.2

We first learned of this image from a Chequamegon History comment by Patrick Jackson of the Smithsonian asking what we knew about the image and whether or not it was Chief Buffalo from La Pointe.

We had never seen it before.

This was our correspondence with Mr. Jackson at the time:

July 17, 2019

Hello, my name is Patrick, and I am an intern at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I’m working on researching a recent acquisition: a painting which came to us identified as a Henry Inman portrait of “Big Buffalo Ke-Che-Wais-Ke, The Great Renewer (1759-1855) (Chippewa).” We have run into some confusion about the identification of the portrait, as it came to us identified as stated above, yet at Harvard Peabody Museum, who was previously the owner of the portrait, it was listed as an unidentified sitter. Seeing as you’ve written a few posts about the identification of images of the three different Chief Buffalos, I thought you might be able to give some insight into perhaps who is or isn’t in the portrait we have. Thank you for your time.

July 17, 2019

Hello,

I would be happy to comment. Can you send a photo to this email?

I am pretty sure Inman painted a copy of Charles Bird King’s portrait of Pee-che-kir.

Doe it resemble that portrait? Pee-che-kir (Bizhiki) means Buffalo in Ojibwe (Chippewa). From my research, I am fairly certain that King’s portrait is not of Kechewaiske, but of another chief named Buffalo who lived in the same era.

Leon Filipczak

July 17, 2019

Dear Leon,

I have attached our portrait—it’s not the best scan, but hopefully there’s enough detail for you to work with. I’ve compared it with the Peechikir in McKenney & Hall, as well as to the Chief Buffalo painted ambrotype and the James Otto Lewis portrait of Pe-schick-ee. The ambrotype has a close resemblance, as does the Peecheckir, though if that is what Charles Bird King painted I have doubts that Inman would make such drastic changes in clothing and pose.

The identification as Big Buffalo/Ke-Che-Wais-Ke/The Great Renewer, as far as I understand, refers to the La Pointe Bizhiki/Buffalo rather than the St. Croix or Leech Lake Buffalos, though of course that is a questionable identification considering Kechewaiske did not (I think) visit Washington until after Inman’s death in January of 1846. McKenney, however, did visit the Ojibwe/Chippewa for the negotiations for the Treaty of Fond du Lac in 1825/1826, and could feasibly have met multiple Chief Buffalos. Perhaps a local artist there would be responsible for the original? Another possibility is, since the identification was not made at the Peabody, who had the portrait since the 1880s, is that it has been misidentified entirely and is unrelated to any of the Ojibwe/Chippewa chiefs. Though this, to me, would seem unlikely considering the strong resemblance of the figure in our portrait to the Peechikir portrait and Chief Buffalo ambrotype.

Thank you again for the help.

Sincerely,

Patrick

July 22, 2019

Hello Patrick,

This is a head-scratcher. Your analysis is largely what I would come up with. My first thought when I saw it was, “Who identified it as someone named Buffalo? When? and using what evidence?” Whoever associated the image with the text “Ke-Che-Wais-Ke, The Great Renewer (1759-1855)” did so decades after the painting could be assumed to be created. However, if the tag “Big Buffalo” can be attached to this image in the era it was created, then we may be onto something. This is what I know:

1) During his time as Superintendent of Indian Affairs (late 1820s), Thomas McKenney amassed a large collection of portraits of Indian chiefs for what he called the “Indian Gallery” in the War Department. He sought the portraits out wherever and whenever he could. When chiefs would come to Washington, he would have Charles Bird King do the work, but he also received portraits from the interior via artists like James Otto Lewis.

2) In 1824, Bizhiki (Buffalo) from the St. Croix River (not Great Buffalo from La Pointe), visited Washington and was painted by King. This painting is presumed to have been destroyed in the Smithsonian fire that took out most of the Indian Gallery.

3) In 1825 at Prairie du Chien and in 1826 at Fond du Lac (where McKenney was present) James Otto Lewis painted several Ojibwe chiefs, and these paintings also ended up in the Indian Gallery. Both chief Buffalos were present at these treaties.

4) A team of artists copied each others’ work from these originals. King, for example remade several of Lewis’ portraits to make the faces less grotesque. Inman copied several Indian Gallery portraits (mostly King’s) to be sent to other institutions. These are the ones that survived the Smithsonian fire.

5) In the late 1830s, 10+ years after most of the portraits were painted, Lewis and McKenney sold competing lithograph collections to the American public. McKenney’s images were taken from the Indian Gallery. Lewis’ were from his works (some of which were in the Indian Gallery, often redone by King). While the images were printed with descriptions, the accuracy of the descriptions leaves something to be desired. A chief named Bizhiki appears in both Lewis and McKenney-Hall. In both, the chiefs are dressed in white and faced looking left, but their faces look nothing alike. One is very “Lewis-grotesque.” and the other is not at all. There are Lewis-based lithographs in both competing works, and they are usually easy to spot.

6) Not every image from the Indian Gallery made it into the published lithographic collections. Brian Finstad, a historian of the upper-St. Croix country, has shown me an image of Gaa-bimabi (Kappamappa, Gobamobi), a close friend/relative of the La Pointe Chief Buffalo, and upstream neighbor of the St. Croix Buffalo. This image is held by Harvard and strongly resembles the one you sent me in style. I suspect it is an Inman, based on a Lewis (possibly with a burned-up King copy somewhere in between).

7) “Big Buffalo” would seemingly indicate Buffalo from La Pointe. The word gichi is frequently translated as both “great” and “big” (i.e. big in size or big in power). Buffalo from La Pointe was both. However, the man in the painting you sent is considerably skinnier and younger-looking than I would expect him to appear c.1826.

My sense is that unless accompanying documentation can be found, there is no way to 100% ID these pictures. I am also starting to worry that McKenney and the Indian Gallery artists, themselves began to confuse the two chief Buffalos, and that the three originals (two showing St. Croix Buffalo, and one La Pointe Buffalo) burned. Therefore, what we are left with are copies that at best we are unable to positively identify, and at worst are actually composites of elements of portraits of two different men. The fact that King’s head study of Pee-chi-kir is out there makes me wonder if he put the face from his original (1824 portrait of St. Croix Buffalo?) onto the clothing from Lewis’ portrait of Pe-shick-ee when it was prepared for the lithograph publication.

A few weeks later, Patrick sent a follow-up message that he had tracked down a second version and confirmed that Inman’s portrait was indeed a copy of a Charles Bird King portrait, based on a James Otto Lewis original. It included some critical details.

Portrait of Big Buffalo, A Chippewa, 1827 Charles Bird King (1785-1862), signed, dated and inscribed ‘Odeg Buffalo/Copy by C King from a drawing/by Lewis/Washington 1826’ (on the reverse) oil on panel 17 1⁄2 X 13 3⁄4 in. (44.5 x 34.9 cm.) Last sold by Christie’s Auction House for $478,800 on 26 May 2022

The date of 1826 makes it very likely that Lewis’ original was painted at the Treaty of Fond du Lac. Chief Buffalo of La Pointe would have been in his 60s, which appears consistent with the image of Big Buffalo. Big Buffalo also does not appear as thin in King’s intermediate version as he does in Inman’s copy, lessening the concerns that the image does not match written descriptions of the chief.

Another clue is that it appears Lewis used the word Odeg to disambiguate Big Buffalo from the two other chiefs named Buffalo present at Fond du Lac in 1826. This may be the Ojibwe word Andeg (“crow”). Although I have not seen any other source that calls the La Pointe chief Andeg, it was a significant name in his family. He had multiple close relatives with Andeg in their names, which may have all stemmed from the name of Buffalo’s grandfather Andeg-wiiyaas (Crow’s Meat). As hereditary chief of the Andeg-wiiyaas band, it’s not unreasonable to think the name would stay associated with Buffalo and be used to distinguish him from the other Buffalos. However, this is speculative.

So, there we were. After the whole convoluted Chief Buffalo Picture Search, did we finally have an image we could say without a doubt was Chief Buffalo of La Pointe? No. However, we did have one we could say was “likely” or even “probably” him. I considered posting at the time, but a few things held me back.

In the earliest years of Chequamegon History, 2013 and 2014, many of the posts involved speculation about images and me trying to nitpick or disprove obvious research mistakes of others. Back then, I didn’t think anyone was reading and that the site would only appeal to academic types. Later on, however, I realized that a lot of the traffic to the site came from people looking for images, who weren’t necessarily reading all the caveats and disclaimers. This meant we were potentially contributing to the issue of false information on the internet rather than helping clear it up. So by 2019, I had switched my focus to archiving documents through the Chequamegon History Source Archive, or writing more overtly subjective and political posts.

So, the Smithsonian image of Big Buffalo went on the back burner, waiting to see if more information would materialize to confirm the identity of the man one way or the other. None did, and then in 2020 something happened that gave the whole world a collective amnesia that made those years hard to remember. When Amorin asked about using the image for his 1842 post, my first thought was “Yeah, you should, but we should probably give it its own post too.” My second thought was, “Holy crap! It’s been five years!”

Anyway, here is Chequamegon History’s statement on the identity of the man in Henry Inman’s 1832-33 portrait of Big Buffalo (Chippewa).

Likely Chief Buffalo of La Pointe: We are not 100% certain, but we are more certain than we have been about any other image featured in the Chief Buffalo Picture Search. This is a copy of a copy of a missing original by James Otto Lewis. Lewis was a self-taught artist who struggled with realistic facial features. Charles Bird King and Henry Inman, who made the first and second copies, respectively, had more talent for realism. However, they did not travel to Lake Superior themselves and were working from Lewis’ original. Therefore, the appearance of Big Buffalo may accurately show his clothing, but is probably less accurate in showing his actual physical appearance.

And while we’re on the subject of correcting misinformation related to images, I need to set the record straight on another one and offer my apologies to a certain Benjamin Green Armstrong. I promise, it relates indirectly to the “Big Buffalo” painting.

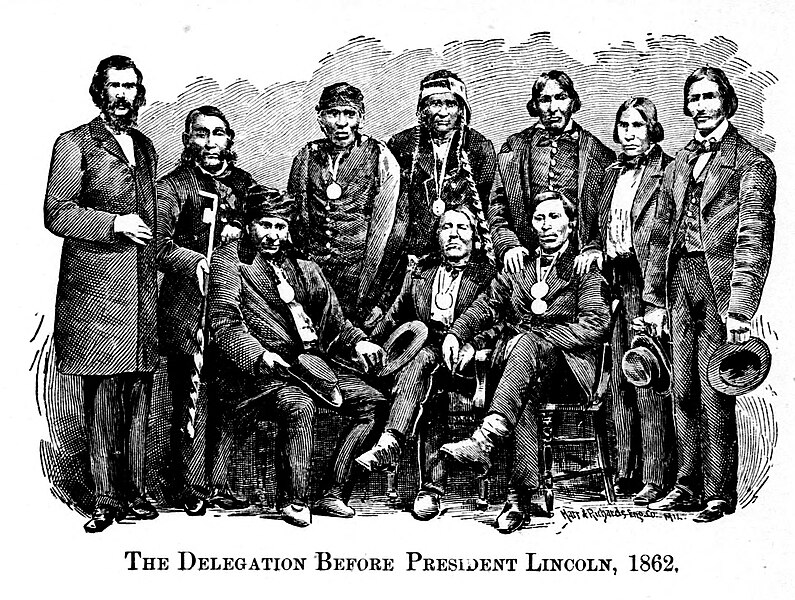

An engraving of the image in question appears in Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians.

Ah-moose (Little Bee) from Lac Flambeau Reservation, Kish-ke-taw-ug (Cut Ear) from Bad River Reservation, Ba-quas (He Sews) from Lac Courte O’Rielles Reservation, Ah-do-ga-zik (Last Day) from Bad River Reservation, O-be-quot (Firm) from Fond du Lac Reservation, Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation, Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell) from La Pointe Reservation, Na-gon-ab (He Sits Ahead) from Fond du Lac Reservation, and O-ma-shin-a-way (Messenger) from Bad River Reservation.

In this post, we contested these identifications on the grounds that Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Little Buffalo) from La Pointe Reservation died in 1860 and therefore could not have been part of the delegation to President Lincoln. In the comments on that post, readers from Michigan suggested that we had several other identities wrong, and that this was actually a group of chiefs from the Keweenaw region. We commented that we felt most of Armstrong’s identifications were correct, but that the picture was probably taken in 1856 in St. Paul.

Since then, a document has appeared that confirms Armstrong was right all along.

[Antoine Buffalo, Naagaanab, and six other chiefs to W.P. Dole, 6 March 1863

National Archives M234-393 slide 14

Transcribed by L. Filipczak 12 April 2024]

To Our Father,

Hon W P. Dole

Commissioner of Indian Affairs–

We the undersigned chiefs of the chippewas of Lake Superior, now present in Washington, do respectfully request that you will pay into the hands of our Agent L. E. Webb, the sum of Fifteen Hundred Dollars from any moneys found due us under the head of “Arrearages in Annuity” the said money to be expended in the purchase of useful articles to be taken by us to our people at home.

Antoine Buffalo His X Mark | A daw we ge zhig His X Mark

Naw gaw nab His X Mark | Obe quad His X Mark

Me zhe na way His X Mark | Aw ke wen zee His X Mark

Kish ke ta wag His X Mark | Aw monse His X Mark

I certify that I Interpreted the above to the chiefs and that the same was fully understood by them

Joseph Gurnoe

U.S. Interpreter

Witnessed the above Signed } BG Armstrong

Washington DC }

March 6th 1863 }

There were eight Lake Superior chiefs, an interpreter, and a witness in Washington that spring, for a total of ten people. There are ten people in the photograph. Chequamegon History is confident that this document confirms they are the exact ten identified by Benjamin Armstrong.

The Lac Courte Oreilles chief Ba-quas is the same person as Akiwenzii. It was not unusual for an Ojibwe chief to have more than one name. Chief Buffalo, Gaa-bimaabi, Zhingob the Younger, and Hole-in-the-Day the Younger are among the many examples.

The name “Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation” seems to be absent from the letter, but he is there too. Let’s look at the signature of the interpreter, Joseph Gurnoe.

Gurnoe’s beautiful looping handwriting will be familiar to anyone who has studied the famous 1864 bilingual petition. We see this same handwriting in an 1879 census of Red Cliff. In this document, Gurnoe records his own Ojibwe name as Shingwākons, The young Pine tree.

So the man standing on the far right is Gurnoe. This can be confirmed by looking at other known photos of him.

Finally, it confirms that the chief seated on the bottom left is not Jechiikwii’o (Little Buffalo), but rather his son Antoine, who inherited the chieftainship of the Buffalo Band after the death of his father two years earlier. Known to history as Chief Antoine Buffalo, in his lifetime he was often called Antoine Tchetchigwaio (or variants thereof), using his father’s name as a surname rather than his grandfather’s.

So, now we need to address the elephant in the room that unites the Henry Inman portrait of Big Buffalo with the photograph of the 1862-63 Delegation to Washington:

Wisconsin Historical Society

This is the “ambrotype” referenced by Patrick Jackson above. It’s the image most associated with Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. It’s also one for which we have the least amount of background information. We have not been able to determine who the original photographer/painter was or when the image was created.

The resemblance to the portrait of “Big Buffalo” is undeniable.

However, if it is connected to the 1862-63 image of Chief Antoine Buffalo, it would support Hamilton Nelson Ross’s assertions on the Wisconsin Historical Society copy.

Clearly, multiple generations of the Buffalo family wore military jackets.

Inconclusive: uncertainty is no fun, but at this point Chequamegon History cannot determine which Chief Buffalo is in the ambrotype. However, the new evidence points more toward the grandfather (Great Buffalo) and grandson (Antoine) than it does to the son (Little Buffalo).

We will keep looking.

Error Correction: Photo Mystery Still Unsolved

April 27, 2014

This post is outdated. We’ll leave it up, but for the latest research, see Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Coda

According to Benjamin Armstrong, the men in this photo are (back row L to R) Armstrong, Aamoons, Giishkitawag, Ba-quas (identified from other photos as Akiwenzii), Edawi-giizhig, O-be-quot, Zhingwaakoons, (front row L to R) Jechiikwii’o, Naaganab, and Omizhinawe in an 1862 delegation to President Lincoln. However, Jechiikwii’o (Jayjigwyong) died in 1860.

In the Photos, Photos, Photos post of February 10th, I announced a breakthrough in the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search. It concerned this well-known image of “Chief Buffalo.”

(Wisconsin Historical Society)

The image, long identified with Gichi-weshkii, also called Bizhiki or Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855, has also been linked to the great chief’s son and grandson. In the February post, I used Benjamin Armstrong’s description of the following photo to conclude that the man seated on the left in this group photograph was in fact the man in the portrait. That man was identified as Jechiikwii’o, the oldest son of Chief Buffalo (a chief in his own right who was often referred to as Young Buffalo).

Another error in the February post is the claim that this photo was modified for and engraving in Armstrong’s book, Early Life Among the Indians. In fact, the engraving is derived from a very similar photo seen at the top of this post (Minnesota Historical Society).

(Marr & Richards Co. for Armstrong)

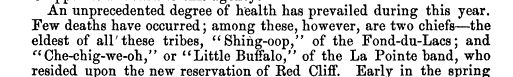

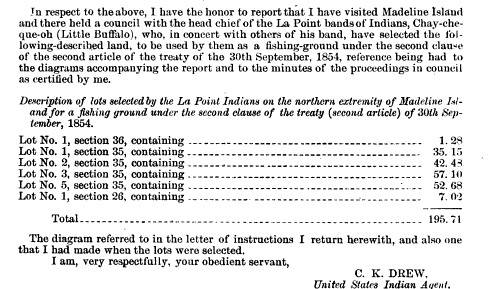

The problem with this conclusion is that it would have been impossible for Jechiikwii’o to visit Lincoln in the White House. The sixteenth president was elected shortly after the following report came from the Red Cliff Agency:

Drew, C.K. Report on the Chippewas of Lake Superior. Red Cliff Agency. 29 Oct. 1860. Pg. 51 of Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Bureau of Indian Affairs. 1860. (Digitized by Google Books).

This was a careless oversight on my part, considering this snippet originally appeared on Chequamegon History back in November. Jechiikwii’o is still a likely suspect for the man in the photo, but this discrepancy must be settled before we can declare the mystery solved.

The question comes down to where Armstrong made the mistake. Is the man someone other than Jechiikwii’o, or is the photo somewhere other than the Lincoln White House?

If it isn’t Jechiikwii’o, the most likely candidate would be his son, Antoine Buffalo. If you remember this post, Hamilton Ross did identify the single portrait as a grandson of Chief Buffalo. Jechiikwii’o, a Catholic, gave his sons Catholic names: Antoine, Jean-Baptiste, Henry. Ultimately, however, they and their descendants would carry their grandfather’s name as a surname: Antoine Buffalo, John Buffalo, Henry Besheke, etc., so one would expect Armstrong (who was married into the family) to identify Antoine as such, and not by his father’s name.

However, I was recently sent a roster of La Pointe residents involved in stopping the whiskey trade during the 1855 annuity payment. Among the names we see:

…Antoine Ga Ge Go Yoc

John Ga Ge Go Yoc…[Read the first two Gs softly and consider that “Jayjigwyong” was Leonard Wheeler’s spelling of Jechiikwii’o]

So, Antoine and John did carry their father’s name for a time.

Regardless, though, the age and stature of the man in the group photograph, Armstrong’s accuracy in remembering the other chiefs, and the fact that Armstrong was married into the Buffalo family still suggest it’s Jechiikwii’o in the picture.

Fortunately, there are enough manuscript archives out there related to the 1862 delegation that in time I am confident someone can find the names of all the chiefs who met with Lincoln. This should render any further speculation irrelevant and will hopefully settle the question once and for all.

Until then, though, we have to reflect again on why Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians is simultaneously the most accurate and least accurate source on the history of this area. It must be remembered that Armstrong himself admitted his memory was fuzzy when he dictated the work in his final years. Still, the level of accuracy in the small details is unsurpassed and confirms his authenticity even as the large details can be way off the mark.

Thank you to Charles Lippert for providing the long awaited translation and transliteration of Jechiikwii’o into the modern Ojibwe alphabet. Amorin Mello kindly shared the 1855 La Pointe documents, transcribed and submitted to the Michigan Family History website by Patricia Hamp, and Travis Armstrong’s ChiefBuffalo.com remains an outstanding bank of primary sources on the Buffalo and Armstrong families.

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Conclusion

December 7, 2013

This post concludes the Chief Buffalo Picture Search, a series of posts attempting to determine which images of Chief Buffalo are of the La Pointe Ojibwe leader who died in 1855, and which are of other chiefs named Buffalo. To read from the beginning, click here to read Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Introduction.

This is Chief Buffalo from St. Croix, not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe.

This is Chief Buffalo from St. Croix, not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe.

This lithograph from McKenney and Hall’s History of the Indian Tribes, was derived from an original oil painting (now destroyed) painted in 1824 by Charles Bird King.Buffalo from St. Croix was in Washington in 1824. Buffalo from La Pointe was not. Read:

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The King and Lewis Lithographs

This could be Chief Buffalo from La Pointe. It could also be Chief Buffalo from St. Croix

This lithograph from James Otto Lewis’ The Aboriginal Port-Folio is based on a painting done by Lewis at the Treaty of Prairie du Chien in 1825 or at the Treaty of Fond du Lac in 1826 (Lewis is inconsistent in his own identification). The La Pointe and St. Croix chiefs were at both treaties. Read:

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The King and Lewis Lithographs

This is not Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. This is the clan marker of Oshkaabewis, a contemporary chief from the headwaters of the Wisconsin River.

The primary sources clearly indicate that this birch bark petition was carried by Oshkaabewis to Washington in 1849 as part of a delegation of Lake Superior Ojibwe protesting Government removal plans. Read:

One of these men could be Chief Buffalo of La Pointe.

This engraving from Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians appears to depict the 1852 Washington Delegation led by Buffalo. However, the men aren’t identified individually, and the original photograph hasn’t surfaced. Read:

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Armstrong Engraving

This is not Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. This is Buffalo the war chief from Leech Lake.

This is not Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. This is Buffalo the war chief from Leech Lake.

Buffalo and Flatmouth, two Pillager (Leech Lake) leaders had their faces carved in marble in Washington in 1855. Buffalo was later copied in bronze, and both busts remain in the United States capitol. The chiefs were part of a Minnesota Ojibwe delegation making a treaty for reservations in Minnesota. Buffalo of Leech Lake was later photographed in St. Paul. Read:

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Capitol Busts

This could be Chief Buffalo of La Pointe.

This could be Chief Buffalo of La Pointe.

Very little is known about the origin of this image. It is most likely Chief Buffalo’s son Jayjigwyong, who was sometimes called “The Little Buffalo.” Read:

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Island Museum Painting

As it currently stands, out of the seven images investigated in this study, four are definitely not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe, and the other three require further investigation. The lithograph of Pee-che-kir from McKenney and Hallʼs History of the Indian Tribes, based on the original painting by Charles Bird King, is Buffalo from St. Croix. The marble and bronze busts in Washington D.C., as well as the carte-d-visite from Whitneyʼs in St. Paul, show Bizhiki the war chief from Leech Lake. The pictograph of the crane, once identified with Buffalo, is actually the Crane-clan chief Oshkaabewis. There is not enough information yet to make a determination on the lithograph of Pe-schick-ee from James Otto Lewisʻ Aboriginal Port Folio, on the image of the 1852 delegation in Armstrongʼs Early Life Among the Indians, or on the photo and painting of the man in the military coat.

In the end, the confusion about all of these images can be attributed to authors with motivations other than recording an accurate history of these men, authors who were not familiar enough with this time period to realize that there was more than one Buffalo. Charles Bird King and Francis Vincenti created some beautiful work in the national capital, but their ultimate goal was to make a record of the look of a supposedly vanishing people. The Pillager Bizhiki was chosen to sit for the sculpture not for who he was, but for what he looked like. The St. Croix Buffalo was chosen because he happened to be in Washington when King was painting. Over a century later, scholars like Horan and Holzhueter being more concerned with the art itself than the people depicted, furthered the confusion. Unfortunately, these mistakes had consequences for the study of history.

While this new information, especially in regard to the busts in Washington, may be discouraging to the people of Red Cliff and other descendants of Buffalo from La Pointe, there is also cause for excitement. The study of these images opens up new lines of inquiry into the last three decades of the chief’s life, a pivotal time in Ojibwe history. Inaccuracies about his life can be corrected, and people will stop having to come up with stories to connect Buffalo to images that were never him to begin with.

My hope is that this investigation will encourage people to learn more about all three Chief Buffalos, all of whom represented their people in Washington, as well as the other Ojibwe leaders from this time period. It is this hopeful story, as well as the possibility of further investigation into the three remaining images, that should lead Chief Buffaloʼs descendants to feel optimism rather than disappointment.

For now, this concludes the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search. I will update in the future, however, if new evidence surface. Thanks for reading, and feel free to add your thoughts in the comments.

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Island Museum Painting

November 9, 2013

This post is one of several that seek to determine how many images exist of Great Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855. To learn why this is necessary, please read this post introducing the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

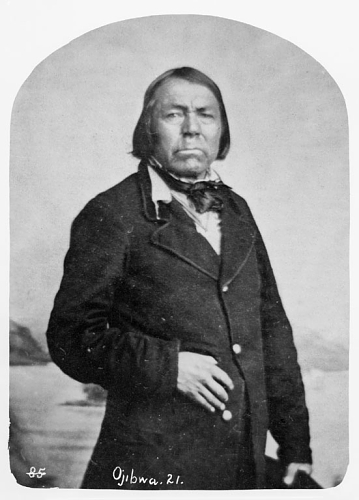

(Wisconsin Historical Society, Image ID: 3957)

If any image has been as closely tied to Chief Buffalo from La Pointe as the the bust of the Leech Lake Buffalo in Washington, it is an image of a kindly but powerful-looking man in a U.S. Army jacket with a medal around his neck. This image appears on the cover of the 1999 edition of Walleye Warriors, by treaty-rights activist Walter Bresette and Rick Whaley. It is identified as Buffalo in both Ronald Satzʼs Chippewa Treaty Rights, and Patty Loewʼs Indian Nations of Wisconsin. It occupies a prominent position in the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society and hangs in the Madeline Island Museum, but in spite of the enduring popularity of this image, very little is known about it.

As I have not been able to thoroughly examine the originals or find any information whatsoever about their creation, chain of custody, or even when they entered the Historical Society’s collections, this post will be the most speculative of the Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

There are two versions of this image. One appears to be an early type of photograph. The Wisconsin Historical Society describes it as “over-painted enlargement, possibly from a double-portrait (possibly an ambrotype).” I’ve been told by staff that the painting that hangs in the museum is a copy of this earlier version.

A photograph of the original image is in the Societyʼs archives as part of the Hamilton Nelson Ross collection. On the back of the photo, “Chief Buffalo, Grandson of Great Chief Buffalo” is handwritten, presumably by Ross. This description would seem to indicate that the image shows one of Chief Buffaloʼs grandsons. However, we need to be careful trusting Ross as a source of information about Buffalo’s family.

Ross, a resident of Madeline Island, gathered volumes of information on his home community in preparation for his book La Pointe Village Outpost on Madeline Island (1960). Although the book is exhaustively researched and highly detailed about the white and mix-blooded populations of the Island, it contains precious little information about individual Indians. The image of Buffalo is not in the book. In fact, the only mention of the chief comes in a footnote about his grave on page 177:

O-Shaka was also known as O-Shoga and Little Buffalo, and he was the son of Chief Great Buffalo. The latter’s Ojibway name was Bezhike, but he was also known as Kechewaishkeenh–the latter with a variety of spellings. Bezhike’s tombstone, in the Indian cemetery, has had the name broken off…

Oshogay was not Buffalo’s son (though he may have been a son-in-law), and he was not the man known as “Little Buffalo,” but until his untimely death in 1853, he seemed destined to take over leadership of Buffalo’s “Red Cliff” faction of the La Pointe Band. The one who did ultimately step into that role, however, was Buffalo’s son Jayjigwyong (Che-chi-gway-on):

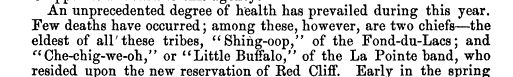

Drew, C.K. Report of the Chippewa Agency of Lake Superior. 26 Oct. 1858. Printed in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. 1858 (Digitized by Google Books)

We will return to Jayjigwyong later in the post, but for now, let’s examine the image itself.

The man in the picture wears an early 19th-century army jacket and a medal. This is consistent with the practices of Chief Buffalo’s day. The custom of handing out flags, jackets, and medals goes back at least to the 1700s with the French. The practice continued under the British and Americans as a way of recognizing certain individuals as chiefs and asserting imperial claims. For the chiefs, the items were symbolic of agreements and alliances. Large councils, treaty signings, and diplomatic missions were all occasions where they were given out. Buffalo had received medals and jackets from the British, and between 1820 and 1855, he took part in the negotiations of at least five treaties, many council meetings and annuity payments, visited Washington, and frequently went back and forth to the agency at Sault Ste. Marie. The United States Government favored Buffalo over the more forcefully-independent chiefs on the Ojibwe-Dakota frontier in Minnesota. Considering all this, it is likely that Buffalo received many jackets, flags, and medals from the Americans over the course of his long interaction with them. An excerpt from a letter by teacher Granville Sproat, who lived in the Lake Superior region in the 1830s reads:

Ke-che Be-zhe-kee, or Big Buffalo, as he was called by the Americans, was then chief of that band of Ogibway Indians who dwell on the south-west shores of Lake Superior, and were best known as the Lake Indians. He was wise and sagacious in council, a great orator, and was much reverenced by the Indians for his supposed intercourse with the Man-i-toes, or spirits, from whom they believed he derived much of his eloquence and wisdom in governing the affairs of the tribe.

“In the summer of 1836, his only son, a young man of rare promise, suddenly sickened and died. The old chief was almost inconsolable for his loss, and, as a token of his affection for his son, had him dressed and laid in the grave in the same military coat, together with the sword and epaulettes, which he had received a few months before as a present from the great father [president] at Washington. He also had placed beside him his favorite dog, to be his companion on his journey to the land of souls (qtd. in Peebles 107).

It is strange that Sproat says Buffalo had only one son given that his wife Florantha Sproat references another son in her description of this same funeral, but sorting out Buffalo’s descendants has never been an easy task. There are references to many sons, daughters, and wives over the course of his very long life.

Another description from the Treaty of 1842 reads:

On October 1 Buffalo appeared, wearing epaulettes on his shoulders, a hat trimmed with tinsel, and a string of bear claws about his neck (Dietrich qtd. in Paap 177-78).

From these accounts we know that Buffalo had these kinds of coats, but dozens of other Ojibwe chiefs would have had similar ones, so the identification cannot be made based on the existence of the coat alone. Consider Naaganab at the 1855 annuity payment:

Na-gon-ub is head chief of the Fond du Lac bands; about the age of forty, short and close built, inclines to ape the dandy in dress, is very polite, neat and tidy in his attire. At first, he appeared in his native blanket, leggings, &c. He soon drew from the Agent a suit of rich blue broadcloth, fine vest, and neat blue cap,–his tiny feet in elegant finely-wrought moccasins. Mr. L., husband of Grace G., with whom he was a special favorite, presented him with a pair of white kid gloves, which graced his hands on all occasions. Some two or three years since, he visited Washington, a delegate from his tribe. Upon this journey, some one presented him with a pair of large and gaudy epaulettes, said to be worth sixty dollars. These adorned his shoulders daily; his hair was cut shorter than their custom. He quite inclined to be with, and to mingle in the society, of the officers, and of white men. These relied on him more, perhaps, than any other chief, for assistance among the Chippewas… (Morse pg. 346)

Portrait of Naw-Gaw-Nab (The Foremost Sitter) n.d by J.E. Whitney of St. Paul (Smithsonian)

In many ways, this description of Naaganab fits the image better than any description of Buffalo I’ve seen. The man is dressed in European fashion, has short hair, and large epaulets. We also know that Naaganab had presidential medals, since he continued to display them until his death in the 1890s. The image isn’t dated, but if it truly is an ambrotype, as described by the State Historical Society, that is a technique of photography used mostly in the late 1850s and 1860s. When Buffalo died in 1855, he was reported to be in his nineties. Naaganab would have been in his forties or fifties at that time. To me, the man in the image appears middle-aged rather than elderly.

So is Naaganab the man in the picture? I don’t think so. For one, there are multiple photographs of the Fond du Lac chief out there. The clothing and hairstyle largely match, but the face is different. The other thing to consider is that this image, to my knowledge, has never been identified with Naaganab. Everything I’ve ever seen associates it with the name Buffalo.

However, there is a La Pointe chief who was a political ally of Naaganab, also dressed in white fashion, could have easily owned a medal and fancy army jacket, would have been middle-aged in the 1850s, and bore the English name of “Buffalo.” It was Jayjigwyong, the son of Chief Buffalo.

Alfred Brunson recorded the following in 1843:

(pg. 158) From elsewhere in the account, we know that the “fifty” year-old is Chief Buffalo. This is odd, as most sources had Buffalo in his eighties at that time.

(pg. 191)

Unlike his famous father, Jayjigwyong, often recorded as “Little Buffalo,” is hardly remembered, but he is a significant figure in the history of our region. He was a signatory of the treaties of 1837, 1847, and 1854. He led the faction of the La Pointe Band that felt that rapid assimilation represented the best chance for the Ojibwe to survive and keep their lands. In addition to wearing white clothing and living in houses, Jayjigwyong was Catholic and associated more with the mix-blooded population of the Island than with the majority of the La Pointe band who sought to maintain their traditions at Bad River.

According to James Blackbird, whose father Makadebineshiinh (Black Bird) led the Bad River faction, it was Jayjigwyong who chose where the Red Cliff reservation was to be. James Blackbird, about eleven or twelve at the time of the Treaty of 1854, would have known both the elder and younger Buffalo.

Statement of James Blackbird in the Matters of the Allotments on the Bad River Reservation, Wis. Odanah, 23 Sep. 1909. Published in Condition of Indian affairs in Wisconsin: hearings before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, [61st congress, 2d session], on Senate resolution, Issue 263. United States Congress. 1910. Pg. 202.

The younger Blackbird, offered more information about the younger Buffalo in another publication.

Even though it is from 1915, there are a number of items in this account that if accurate are very relevant to pre-1860 history. For this post, I’ll stick to the two that involve Jayjigwyong. This is the only source I’ve ever seen that refers to Chief Buffalo marrying a white woman captured on a raid. This lends further credence to the argument explored by Dietrich and Paap that Chief Buffalo fought in the Ohio Valley wars of the 1790s. It also begs the question of whether being perceived as a “half-breed” had an impact on Jayjigwyong’s decisions as an adult.

James Blackbird (seated) with interpreter John Medeguan in Washington, 1899. (Photo by Gil DeLancy, Smitsonian Collections)

The other interesting part of the statement is that James Blackbird says his father was pipe carrier for Jayjigwyong. This would be surprising as Blackbird was the most influential La Pointe chief after the death of Buffalo. However, this idea of Jayjigwyong, inheriting the symbolic “head chief” title from his father can also be seen in the following document from 1857:

Published in Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior. Office of Indian Affairs. 1882. pg. 299. (Digitized by Google Books)

Today the fishing ground at the tip of Madeline Island is now considered part of the Bad River Reservation, but it was the Red Cliff chief who picked it out. This shows how the political division of the La Pointe Band into two distinct entities took several years to take shape, and was not an abrupt split at the Treaty of 1854.

Jayjigwyong continued to be regarded as a chief until his death in 1860:

Drew, C.K. Report on the Chippewas of Lake Superior. Red Cliff Agency. 29 Oct. 1860. Pg. 51 of Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Bureau of Indian Affairs. 1860. (Digitized by Google Books). Zhingob (Shing-oop) was Naaganab’s cousin and the hereditary chief at Fond du Lac. Also known as Nindibens, he figures prominently in Edmund F. Ely’s journals of the mid-1830s.

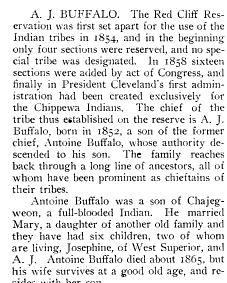

Future generations of the Buffalo family continued to be looked at as hereditary chiefs in Red Cliff, and sources can be found calling these grandsons and great-grandsons “Chief Buffalo.”

J.H. Beers and Co. Commemorative Biographical Record of the Upper Lake Region. 1905. Pg. 379. (Digitized by Google Books).

Antoine brings us full circle. If we remember, Hamiton Ross wrote that the image of the chief in the army jacket was Chief Buffalo’s grandson. And while we don’t know where Ross got his information, and he made mistakes about Buffalo’s family elsewhere, we have to consider that Antoine Buffalo was an adult by 1852 and he could have inherited his father’s, or grandfather’s, medal and coat.

The Verdict

Although we’ve uncovered several lines of inquiry for this image, all the evidence is circumstantial. Until we know more about the creation and chain of custody, it’s impossible to rule Chief Buffalo in or out. My gut tells me it’s Buffalo’s son, Jajigwyong, but it could be his grandson, Naaganab, or and entirely different chief. We don’t know.

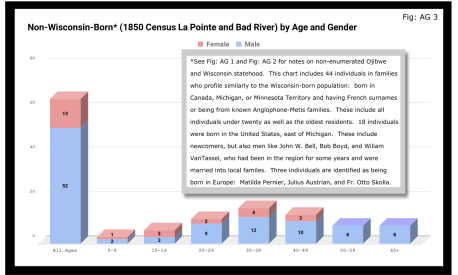

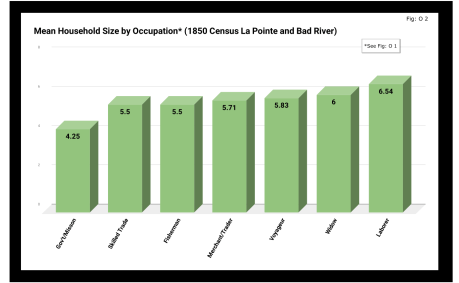

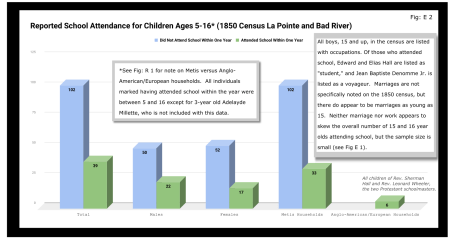

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his