Judge Bell Incidents: King No More

October 16, 2025

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

This post is the second of a series featuring newspaper items about La Pointe’s infamous Judge John William Bell. Today we explore obituaries of Judge Bell that described his life at La Pointe. Future posts of this series will feature articles about the late Judge Bell written by his son-in-law George Francis Thomas née Gilbert Fayette Thomas a.k.a G.F.T.

… continued from King of the Apostle Islands.

King of the Apostle Islands No More

ASHLAND, Wis., Dec. 31. – Judge Bell, known far and wide as “King of the Apostle Islands,” died yesterday. For nearly half a century he governed what was practically a little monarchy in the wilderness. He was 83 years old, and was the oldest living settler on the historic spot where Marquette founded his mission, two hundred years ago.

KING OF THE ISLANDS.

Judge Bell,

“King of the Apostle Islands,”

Has Given Up His Crown.

The Oldest Living Pioneer

of the Historic Spot

Dies in Apparent Poverty,

Special to the Globe.

ASHLAND, Wis., – “The king of the Apostle islands” is dead. He passed away at an early hour this morning at La Pointe, on Madeline, the largest of the group, where he has lived for forty-four years, the oldest living pioneer of the historic spot where Pere Marquette founded his little Indian mission 200 years ago. Judge Bell was a character in the early history of the Lake Superior region, known far and wide as the “king” of the country known as La Pointe, which was organized in 1846 by Judge Bell. The area of the country was as large as many states of the Union, its borders including nearly all of Wisconsin north of the Chippewa river, the Apostle islands and to an almost

ENDLESS DISTANCE WEST.

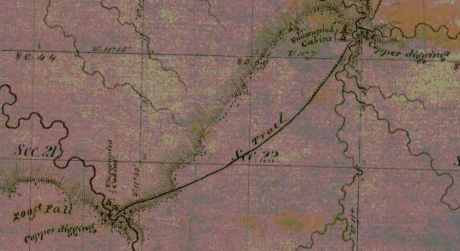

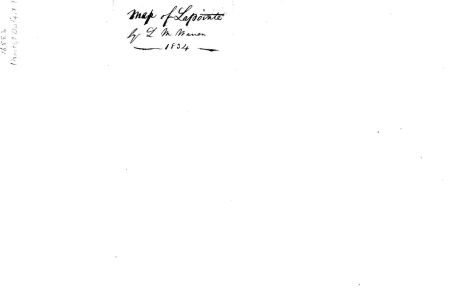

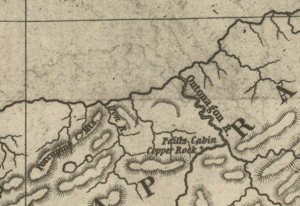

Wisconsin Historical Society’s copy of Lyman Warren’s 1834 “Map of La Pointe” from the American Fur Company Papers at New York Historical Society.

The population of whites consisted only of a small handful of French voyagers, traders and trappers, most of whom rendezvous at La Pointe. The country was hardly known by the state, and Bell’s county was practically a young monarchy. He bossed everything and everybody, but in such a way that every Indian and every white was his friend and follower. Judge Bell came here in 1832, from Canada, in the employ of the American Fur company, which at that time was a power here. He had rarely left the island, except in years gone by to make occasional pilgrimages through the settlements. During his eventful life he held every office in the county, and for many years, served as county judge. He was a man of great native ability, possessed of a courage that controlled the rough element which surrounded him in the early days when there was no law except his will. He was honest, fearless,

A NATURAL-BORN RULER

of men, and through his efforts the poor and needy were cared for, and in no instance did he fail to befriend them. For this reason among those who survive him, and who lived in the good old pioneer days, all were his firm friends. His power departed only when the advance guard of civilization reached the great inland sea, through the medium of the iron horse, and opened a new era in the history of the new Wisconsin. For many years he has been old and feeble and has suffered for the comforts of life, having become a charge upon the town. He squandered thousands for the people and died poor but not friendless. He was eighty-three years of age.

ANOTHER PIONEER GONE

DEATH OF “SQUIRE” BELL, “THE KING OF LAPOINTE.”

Sketch of the Life of the Oldest Settler in the Lake Superior Region.

He comes to La Pointe With John Jacob Astor for the American Fur Co.

Judge John W. Bell died Friday morning at seven o’clock at his home at La Pointe, on Madeline Island, aged eighty-four years.

1847 PLSS survey map detailing the mouth of Iron River at what is now Silver City, Michigan along the east entrance to the Porcupine Mountains.

John W. Bell was born in New York City on May 3, 1803, and was consequently eighty-four years and seven months old. He learnt the trade of a cooper, and in this capacity in the year 1835, he came to the Lake superior country for the United States Fur company. He first settled at the mouth of Iron river, in Michigan, about twenty miles west of Ontonagon. Here, at that time, was one of the principal trading and fishing posts of the American Fur company, La Pointe being its headquarters. Remaining at Iron river for a few years, he came to La Pointe about 1840, where he continued to reside till the time of his death.

1845 United States map by John Dower, with the northernmost area of Wisconsin Territory that became La Pointe County.

At the time he came upon this lake its shores were an unbroken wilderness. At the Sault was a United States fort, but from the foot of Lake Superior to the Pacific ocean, no white settlement existed. The American and Northwest Fur companies were lords of this vast empire, and their trading posts and a few mission stations connected with them, held control. A small detachment of United States soldiers formed the distant outposts of Ft. Snelling. The state of Wisconsin had not been organized. No municipal government existed upon this lake. It was many years before Wisconsin was organized.

1845 United States map by J. Calvin Smith, with the original 1845 boundaries of La Pointe County added in red outline.

“beginning at the mouth of Muddy Island river [on the Mississippi River], thence running in a direct line to Yellow Lake, and from thence to Lake Courterille, so to intersect the eastern boundary line at that place, of the county of St Croix, thence to the nearest point on the west fork of Montreal river, thence down said river to Lake Superior.”

Finally the county of La Pointe was formed, embracing all Wisconsin bordering upon the lake and extending to town forty north. “Squire Bell,” as he was always called, became one of the county as well as town officers of the town and county of La Pointe, and for more than thirty years continued to hold office, being at different times chairman of supervisors, register of deeds, justice of the peace, clerk of the circuit court and county judge. This last office he held for many years.

He was a man of genial nature and robust frame. About four years ago, while in Ashland he fell and fractured his thigh, and was never able to walk again. His sufferings from this accident were great and his pleasant face was never seen again in Ashland. He enjoyed the esteem and friendship of his neighbors, so far as is known without exception. He was clear headed and of commanding appearance. His influence among the Indians and the French who for many years were the only inhabitants in the country was very great, and continued to the last. For years his dictum was the last resort for the settlement of the quarrels in this primitive community, and it seems to have been just and satisfactory. He was often called “The King of La Pointe,” and for years no one disputed his supremacy.

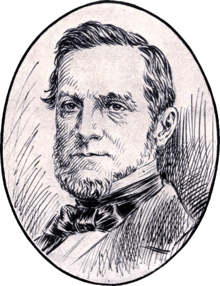

Edwin Ellis, M.D.

Dr. Edwin Ellis, of this city, said in speaking of the dead old pioneer:

“Thus one by one the early settlers are passing away, and ere long an entirely new generation will occupy the old haunts. He will rest upon the beautiful isle overlooking Chequamegon bay, where the landscape has been familiar to him for more than a generation. We a little longer linger on the shores of time, waiting the summons to cross the river. While we consign the body of an old friend to the earth we will in all heartfelt sorrow say: ‘Requiescat in Pace.'”

The Lake Superior Monarch

Judge Bell, the ‘king of the Apostle islands,’ who died the other day on Madeline Island at the age of eighty-three, was a conspicuous character in the early history of the Lake Superior region. He was the “king” of the county known as La Pointe, which was organized in 1846 by himself. The county was as large as many states of the Union, its borders including nearly all of Wisconsin north of the Chippewa river, the Apostle islands, and to an almost endless distance west. The white population consisted of a handful of French voyagers, traders and trappers, most of whom made their rendezvous at La Pointe. The country was hardly known by the state, and Bell’s realm was practically a little monarchy. He “bossed” everything and everybody, but in such a way that every Indian and every white was his friend and follower. Judge Bell rarely left the island except to make occasional pilgrimages through the settlements. During his eventful life he held every office in the county, and of late years had served as county judge. He was a man of great native ability, and was possessed of a courage that controlled the rough element that surrounded him in the early days when there was no law except his will. He was an honest, fearless, natural-born ruler of men. Through his efforts the poor and needy were cared for. His power departed only when the advanced guard of civilization reached the great inland sea. For many years he had been feeble, and of late had become a charge upon the town. He spent thousands upon the people.

To be continued in Fooled the Austrian Brothers…

1839 Petitions against Payments at La Pointe

October 10, 2025

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Previously we featured 1837 Petitions from La Pointe to the President about $100,000 Payments to Chippewa Mixed-Bloods from the 1837 Treaty of Saint Peters, and 1838 more Petitions from La Pointe to the President about relocating the Payments from St. Croix River to Lake Superior. Those earlier Petitions were from Chief Buffalo and dozens of Mixed-Bloods from the Lake Superior Chippewa Bands, setting precedence for La Pointe to host the 1842 Treaty and 1854 Treaty in later decades.

Today’s post features 1839 Petitions against Payments at La Pointe. These petitioners appear to be looking to get a competitive edge against the American Fur Company monopoly at La Pointe, by moving the payments south across the Great Divide into the Mississippi River Basin.

For more information about the $100,000 Payments at La Pointe in 1839, we strongly recommend Theresa M. Schenck’s excellent book All Our Relations: Chippewa Mixed-Bloods and the Treaty of 1837.

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs:

La Pointe Agency 1831-1839

National Archives Identifier: 164009310

April 9, 1839

from Joseph Rolette at Prairie du Chien

to the Superintendent of Indian Affairs

Received April 27, 1839

Prairie du Chiene 9th April 1839

T.H. Crawford Esq’r

Commissioner of Ind’n affairs

Washington

You must excuse the liberty I take in addressing you once more – presuming you are not well acquainted yet with this Country, I am requested by the Chippewaw half Breeds that remain in this Country, that it is with regret they have heard that the payment allowed to them in the treaty of the 29th July 1837 is to be made on Lake Superior. They have to State, that it will be impossible for them to reach that place as the American Fur Co. are the only Co. who have vessels on Lake Superior & Notwithstanding they could procure on Passage Gratis on the Lake.

This distance between Sault Ste Mary, and the Mississippi is great and expensive. They also represent that the half Breeds born on Lake Superior are not entitled to any Share of the money allowed.

Whereas if the Payment was made at the Falls of St. Croix, there would be Competition amongst traders, whereas in Lake Superior they can be done none. They humbly beseech that you will have Mercy on them and not allow them to be deprived by intrigue of the Sum due them. So Justly to go in other hands but the real owners.

Respectfully

your most obd’t Serv’t

Joseph Rolette

on behalf of the Chippewaw

Half Breeds of

Prairie du Chiens

June 21, 1839

from the Indian Agent at Saint Peters

via the Governor of Wisconsin Territory

to the Superintendent of Indian Affairs

Received July 16, 1839

Answered July 24, 1839

Superintendency of Indn Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point June 20, 1839

Sir,

Henry Dodge

Governor of Wisconsin Territory

I have the honor to transmit, enclosed herewith, three letters from Major Taliaferro, Indian Agent at St Peters, dated 10th, 16th, & 17th inst, with two Indian talks of 3rd & 14th, for the information of the Department.

Very respectfully

Yours obedt sevt

Henry Dodge

Supt Ind Agy

T Hartley Crawford Esq

Com. of Indian Affairs

North Western Agency St Peters

Upper Mississippi June 10th 1839

Governor,

Lawrence Taliaferro

Indian Agent at Fort Snelling

I deem it to be most adviseable that the enclosed paper, addressed to the Agent, and Commanding Officer on this Station from the Chippewa Chief “Hole in the Day” should be forwarded to you, the Indians addressing us being within your Excellency’s Superintendency. It may be well to add that a similar document proceeding from the Chippewa Chiefs of St Croix was on the 4th inst forwarded for the information of the Office of Indian Affairs at Washington.

The consolidation of the two Chippewa Sub Agencies and located at Lapointe, it is feared may lead to rather unpleasant results. I know the Chippewas well, and may have as much influence with those of the Mississippi particularly as most men, yet were I to say “you are not to have an agent in your Country, and you must go to Lapointe in all time to come for your Annuity, and treaty Stipulations.” I should not expect to hold their confidence for one day.

With high respect Sir

Your mo obt Serv

Law Taliaferro

Indian Agent

at S. Peters

His Excellency

Governor Henry Dodge

Suprt of Indi Affairs

at Mineral Point

For Wisconsin

North Western Agency S. Peters

Upper Mississippi June 16th, 1839

Governor

I have been earnestly selected by a number of the respectable half breed Chippewas resident, and others of the Mississippi, interested in the $100,000 set apart in the treaty of July 29, 1837 of S. Peters, to ask for such information as to their final disposal of this Sum, as may be in your possession.

The claimants referred to have learned through the medium of an unofficial letter from the Hon Lucius Lyon to H. H. Sibley Esqr. of this Post, that the funds in question as well as the Debts of the Chippewas to the traders was to be distributed by him as the Commissioner of the United States at Lapointe on Lake Superior, and for this purpose should reach that place on or about the 10th of July. The individuals Seeking this information are those who were were so greatly instrumental in bungling your labours at the treaty aforesaid to a successful issue in opposition to the combinations formed to defeat the objects of the government.

There remains 56,000$ in specie at this post being the one half of the sum appropriated or applicable to the objects in contemplation, and upon which the authorities here have had as yet no official instructions to transfer some special information would relieve the minds of a miserably poor class of people and who fear the entire loss of their just claims.

With high respect, Sir

your mo obt Sevt

Law Taliaferro

Indn Agent

at S. Peters

His Excellency

Gov Henry Dodge

Suprt of Ind. Affairs

for Wisconsin

North Western Agency S. Peters

Upper Mississippi June 17th 1839

Governor

On the 20th of May past I dispatched Peter Quin Express to the Chippewas of the Upper Mississippi with a letter from Maj D. P. Bushnell agent for this tribe at Lapointe notifying the Indians, and half breeds that they would be paid at Lapointe hereafter, and at an earlier period than the last year. I informed you of the result of his mission on the 10th inst. enclosing at the same time the written sentiments of the principle Chief for his people. I now forward by Express a second communication from the Same Source received late last night. I would make a plain copy, but have not time. So the original is Sent.

In four days there will be a large body of Chippwas here, and they cannot be Stopped. There are now also 880 Sioux from remote Sections of the Country at this Post and of course we may calculate on some difficulty between these old enemies. Your presence is deemed essential, or such instructions as may soothe the Angry feelings of the Chippewas, on account of the direction given to their annuity, & treaty Stipulations.

With high respect Sir

Your mo ob Sevt

Law Taliaferro

Indn Agent

at S Peters

His Excellency

Governor Henry Dodge

Suprt of Indi Affairs

Mineral Point

(NB) The Chippewas are to be understood as to the point of payment indicated to be the St.Croix, and not the S.Peters, as deemed by the written Talks. It never could be admited in the present state of the Tribes to pay the Chippewas at this Post, but they might with safety to all parties be paid at or above the Falls of S.Croix, by an agent who they ought to have or some special person assigned to this duty.

Elk River, June 3rd 1839

Maj Toliver. Maj Plimpton.

My respects to you both, and my hand: I am to let you know that I intend to pay you a visit, with my chiefs as braves, the principle of my warriors are verry anxious to pay you a visit.

The above mentioned men are verry anxious to see Gov. Dodge with whom we made the treaty, that we may have a talk with him. It was with him commissioner of the United-States we made the treaty, and we are verry much disappointed to hear the newes, we hear this day (IE that we must go to Lake Sup. for our pay) which we have this day decided we will not do; that we had rather die first: it is on this account we wish to pay you a visit, and have a talk with Gov. Dodge. You sir, Maj Toliver know verry well our situation, and that the distance is so great for us to go to Lake Sup. for to get our pay &c. or even a gun repaired; that it is inconsistent for such a thing to be required of us; even if we did literally place the matter in the hands of Government. We are all living yet that was present at the treaty when we ceded the land to the Unitedstates, and remember well what was our understanding in the agreement.

We now wish Maj Toliver; to mention to your children that it is a fals report that we had any intention to have more difficulty with the Sioux, as our Missionaries can attest as far as they understand us. We will be at the Fort in seventeen days to pay you a friendly visit as soon as we received the news; we sent expressed to our brethren to meet us at the mouth of Rum Riv. and accompany us to the Fort.

It is my desire that Maj Plimpton would keep fast hold of the money appropriated for my children the half breeds, in this section, and not let it go to Lake Sup. as they are like ourselves and it would cost them a great deal to go there for it.

Pah-ko-ne-ge-zeck or Hole in the Day

Maj Toliver

Maj Plimpton

Elk River June 14 1839

Maj L. Toliphero,

My hand, It is twelve dayes since we have the newes and are all qouiet yet. My father I shall not forget what was promiced us below, I think of what you promiced us when you were buing our lands.

My father this is the thing that you & we me to take care of when you bougt our lands & I remember all that you said to me. My father I am the cheif of all the Indians that sold there land and this is the time when all of your children are coming down to receive their payment where you promiced to pay us.

My father I am the cheif and hold the paper containing the promices that you made us. The Gov. D. promised us that in one year from the date of the treaty that we should receive our first payment and so continue anually.

My father; I have done for manny years what the white men have told me and have done well, and now I must look before we are to know what I have to do.

When I buy anything I pay immediately the Great Spirit knows this Now when we get below we are expecting all that you promiced us Ministers and Black Smiths and cattle.

I say my father that we want our payment at St Peters where you promiced us. I said that I wanted the half breeds to be payed there with us. I told you that when the half breeds were payed that there was some French that should have something ((ie) of the half breed money) because they had lived with us for many years and allways gave us some thing to eat when we went to their houses.

My father all of your children are displeased because you are to pay us in another place and not at St Peters it is to hard and far for us to be payed at Lapointe.

My father I did not know that the payment was to be made at Lapointe until we heard by Mr Quin.

My father it is so far to Lapointe that we should lose all of our children before we could get their and if we should brake our Gun we may throw it in the water for we cannot go there to get it mended, and if we have a [illegible] holding a coppy of the Treaty in his hand

Black Smith we want him here and not at Lapoint.

My father I want that you should tell me who it was told you that we all wanted our payment at Lapoint. All of the Cheifs are alive that hear what you said to us below. You Mr Toliphero hear me ask Gov Do’ for an Agen and to have him located here and he promiced that it should be so. I want that the Agent should be here because our enemies come here sometimes and if he was here perhaps they would not come. My father we are all of us very sorry that we did not ask you to come and be our Agent. I don’t know who made all of the nois about our being payed at Lapoint. I don’t look above where we should all starve for our payment but below where the Treaty was made.

My father give my compliments to all of the officers at the Fort.

Hole in The Day X

Maj L Toliphereo

Judge Bell Incidents: King of the Apostle Islands

January 30, 2025

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

This post is the first of a series featuring The Ashland News items about La Pointe’s infamous Judge John William Bell, written mainly by his son-in-law George Francis Thomas née Gilbert Fayette Thomas a.k.a G.F.T.

Wednesday, September 30, 1885, page 2.

Wednesday, September 30, 1885, page 2.

ON HISTORICAL GROUND.

James Chapman

~ Madeline Island Museum

Judge Joseph McCloud

~ Madeline Island Museum

Saturday last, says The Bayfield Press, the editor had the pleasure of visiting Judge John W. Bell at his home at La Pointe, accompanied by Major Wing, James Chapman and Judge Joseph McCloud. The judge, now in his 81st year, still retains much of that indomitable energy that made him for many years a veritable king of the Apostle Islands. Owing, however, to a fractured limb and an irritating ulcer on his foot he is mostly confined to his chair. His recollection of the early history of this country is vivid, while his fund of anecdotes of his early associates is apparently inexhaustible and renders a visit to this remarkable pioneer at once full of pleasure and instruction. The part played by Judge Bell in the early history of this country is one well worthy of preservation and in the hands of competent parties could be made not the least among the many historical sketches of the pioneers of the great northwest. The judge’s present home is a large, roomy house, located in the center of a handsome meadow whose sloping banks are kissed by the waters of the lake he loves so well. Here, surrounded by children and grand-children, cut off from the noise and bustle of the outside world, his sands of life are peacefully passing away.

Leaving La Pointe our little party next visited the site of the Apostle Islands Improvement company’s new summer resort and found it all the most vivid fancy could have painted. Here, also, we met Peter Robedeaux, the oldest surviving voyager of the Hudson Bay Fur Co. Mr. Robedeaux is now in his 89th year, and is as spry as any man not yet turned fifty. He was born near Montreal in 1796, and when only fourteen years of age entered the employ of the Hudson Bay Fur Co., and visited the then far distant waters of the Columbia river, in Washington Territory. He remained in the employ of this company for twenty-five years and then entered the employ of the American Fur company, with headquarters at La Pointe. For fifty years this man has resided on Madeline Island, and the streams tributary to the great lake not visited by him can be numbered by the fingers on one’s hand. His life until the past few years has been one crowded with exciting incidents, many of which would furnish ample material for the ground-work of a novel after the Leather Stocking series style.

Wednesday, June 30, 1886, page 2.

Wednesday, June 30, 1886, page 2.

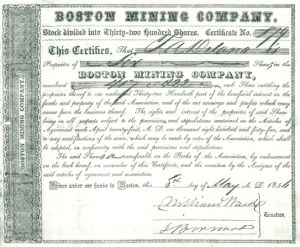

GOLDEN WEDDING.

About thirty of the old settlers of Ashland and Bayfield went over to La Pointe on Saturday to celebrate the golden wedding anniversary of Judge John W. Bell and wife, who were married in the old church at La Pointe June 26th, 1836, fifty years ago. The party took baskets containing their lunch with them, the old couple having no knowledge of the intended visit. After congratulations had been extended the table was spread, and during the meal many reminiscences of olden times were called up.

Judge Bell is in his eighty-third year, and is becoming quite feeble. Mrs. Bell is perhaps ten or twelve years younger. Judge Bell came to La Pointe in 1834, and has lived there constantly ever since. La Pointe used to be the county seat of Ashland county, and prior to the year 1872 Judge Bell performed the duties of every office of the county. In fact he was virtually king of the island.

The visitors took with them some small golden tokens of regard for the aged couple, the coins left with them aggregating between $75 and $100.

Wednesday, July 20, 1887, page 6.

Wednesday, July 20, 1887, page 6.

REMINISCENCES OF OLD LA POINTE

(Written for The Ashland News)

Visitors to this quiet and delapidated old town on Madeline Island, Lake Superior, about whom early history and traditions so much has been published, are usually surprised when told that less than forty years have passed since there flourished at this point a city of about 2,500 people. Now not more than thirty families live upon the entire island. Thirty-five years ago neither Bayfield, Ashland nor Washburn was thought of, and La Pointe was the metropolis of Northern Wisconsin.

Since interesting himself in the island the writer has often been asked: Why, if there were so many inhabitants there as late as forty years ago, are there so few now? In reply a great number of reasons present themselves, chief among which are natural circumstances, but in the writer’s mind the imperfect land titles clouding old La Pointe for the last thirty years have tended materially to hastening its downfall.

Captain John Daniel Angus

~ Madeline Island Museum

Of the historic data of La Pointe, of which the writer has almost an unlimited supply, much that seems romance is actual fact, and the witnesses of occurrences running back over fifty years are still here upon the island and can be depended upon for the truthfulness of their reminiscences. There are no less than five very old men yet living here who have made their homes upon the island for over fifty years. Judge John W. Bell, or “Squire,” as he is familiarly called, has lived here since the year 1835, coming from the “Soo,” on the brig, John Jacob Astor, in company with another old pioneer of the place known as Capt. John Angus. Mr. Bell contracted with the American Fur Co., and Capt. Angus sailed the “Big Sea” over. Mr. Bell is now eighty three years of age, and is crippled from the effects of a fall received while attending court in Ashland, in Jan. 1884. He is a man of iron constitution and might have lived – and may yet for all we know – to become a centenarian. The hardships of pioneer life endured by the old Judge would have killed an ordinary man long ago. He is a cripple and an invalid, but he has never missed a meal of victuals nor does he show any sign of weakening of his wonderful mind. He delights to relate reminiscences of early days, and will talk for hours to those who prove congenial. Once in his career, Mr. Bell had in his employ the famous “Wilson, the Hermit,” whose romantic history is one of the interesting features sought after by tourists when they visit the islands.

~ History of Northern Wisconsin, by the Western Historical Co., 1881.

Once Mr. Bell started an opposition fur company having for his field of operations that portion of Northern Wisconsin and Michigan now included within the limits of the great Gogebic and Penokee iron ranges, and had in his employ several hundred trappers and carriers. Later Mr. Bell became a prominent explorer, joining numerous parties in the search for gold, silver and copper; iron being considered too inferior a metal for the attention of the popular mind in those days.

Almost with his advent on the island Mr. Bell became a leader in the local political field, during his residence of fifty-two years holding almost continually some one of the various offices within the gift the people. He was also employed at various times by the United States government in connection with Indian affairs, he having a great influence with the natives.

Ramsay Crooks

~ Madeline Island Museum

The American Fur Co., with Ramsay Crooks at its head gave life and sustenance to La Pointe a half century ago, and for several years later, but when a private association composed of Borup, Oakes and others purchased the rights and effects of the American Fur Co., trade at La Pointe began to fall away. The halcyon days were over. The wild animals were getting scarce, and the great west was inducing people to stray. The new fur company eventually moved to St. Paul, where even now their descendants can be found.

Julius Austrian

~ Madeline Island Museum

Prior to the final extinction of the fur trade at La Pointe and in the early days of steamboating on the great lakes, the members of the well-known firm of Leopold & Austrian settled here, and soon gathered about them a number of their relatives, forming quite a Jewish colony. They all became more or less interested in real estate, Julius and Joseph Austrian entering from the government at $1.25 per acre all the lands upon which the village was situated, some 500 acres.

The original patent issued by the government, of which a copy exists in the office of the register of deeds in Ashland, is a literary curiosity, as are also many other title papers issued in early days. Indeed if any one will examine the records and make a correct abstract or title history of old La Pointe, the writer will make such person a present of one of the finest corner lots on the island. Such a thing can not be done simply from the records. A large portion of the original deeds for village lots were simply worthless, but the people in those days never examined into the details, taking every man to be honest, hence errors and wrongs were not found out.

Now the lots are not worth the taxes and interest against them, and the original purchaser will never care whether his title was good or otherwise. The county of Ashland bought almost the whole town site for taxes many years ago and has had an expensive load to carry until the writer at last purchased the tax titles of the village, which includes many of the old buildings. The writer has now shouldered the load, and proposes to preserve the old relics that tourists may continue to visit the island and see a town of “Ye olden times.”

Originally the intention was to form a syndicate to purchase the old town. An association of prominent citizens of Ashland and Bayfield, at one time came very near securing it, and the writer still has hopes of such an association some day controlling the historical spot. The scheme, however, has met with considerable opposition from a few who desire no changes to be made in the administration of affairs on the island. The principal opponent is Julius Austrian, of St. Paul, who still owns one-sixth part of La Pointe, and is expecting to get back another portion of lots, which have been sold for taxes and deeded by the county ever since 1874. He would like no doubt, to make Ashland county stand the taxes on the score of illegality. As a mark of affection for the place, he has lately removed the old warehouse which has stood so many years a prominent landmark in La Pointe’s most beautiful harbor. Tourists from every part of the world who have visited the old town will join in regretting the loss and despise the action.

G. F. T.

To be continued in King No More…

1842 Treaty Speeches at La Pointe in the News

May 15, 2024

Collected by Amorin Mello & edited by Leo Filipczak

Robert Stuart was a top official in Astor’s American Fur Company in the upper Great Lakes region. Apparently, it was not a conflict of interest for him to also be U.S. Commissioner for a treaty in which the Fur Company would be a major beneficiary.

A gentleman who has recently returned from a visit to the Lake Superior Indian country, has furnished us with the particulars of a Treaty lately negotiated at La Pointe, during his sojourn at that place, by ROBERT STUART, Esq., Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the district of Michigan, on the part of the United States, and by the Chiefs and Braves of the Chippeway Indian nation on their own behalf and their people. From 3 to 4000 Indians were present, and the scene presented an imposing appearance. The object of the Government was the purchase of the Chippeway country for its valuable minerals, and to adopt a policy which is practised by Great Britain, i.e. of keeping intercourse with these powerful neighbors from year to year by paying them annuities and cultivating their friendship. It is a peculiar trait in the Indian character of being very punctual in regard to the fulfillment of any contract into which they enter, and much dissatisfaction has arisen among the different tribes toward our Government, in consequence of not complying strictly to the obligations on their part to the Indians, in the time of making the payments, for they are not generally paid until after the time stipulated in the treaty, and which has too often proven to be the means of losing their confidence and friendship.

On the 30th of September last, Mr. Stuart opened the Council, standing himself and some of his friends under an awning prepared for the occasion, and the vast assembly of the warlike Chippeways occupying seats which were arranged for their accommodation. A keg of Tobacco was rolled out and opened as a present to the Indians, and was distributed among them; when Mr. Stuart addressed them as follows:-

The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was a metaphor for infinite abundance in 1842. In less than 75 years, the species would be extinct. What that means for Stuart’s metaphor is hard to say (Biodiversity Heritage Library).

The chiefs who had been to Washington were the St. Croix chiefs Noodin (pictured below) and Bizhiki. They were brought to the capital as part of a multi-tribal delegation in 1824, which among other things, toured American military facilities.I am very glad to meet and shake hands with so many of my old friends in good health; last winter I visited your Great Father in Washington, and talked with him about you. He knows you are poor and have but little for your women and children, and that your lands are poor. He pities your condition, and has sent me here to see what can be done for you; some of your Bands get money, goods, and provisions by former Treaty, others get none because the Great Council at Washington did not think your lands worth purchasing. By the treaty you made with Gov. Cass, several years ago, you gave to your lands all the minerals; so the minerals belong no longer to you, and the white men are asking him permission to take the minerals from the land. But your Great Father wishes to pay you something for your lands and minerals before he will allow it. He knows you are needy and can be made comfortable with goods, provisions, and tobacco, some Farmers, Carpenters to aid in building your houses, and Blacksmiths to mend your guns, traps, &c., and something for schools to learn your children to read and write, and not grow up in ignorance. I hear you have been unpleased about your Farmers and Blacksmiths. If there is anything wrong I wish you would tell me, and I will write all your complaints to your Great Father, who is ever watchful over your welfare. I fear you do not esteem your teachers who come among you, and the schools which are among you, as you ought. Some of you seem to think you can learn as formerly, but do you not see that the Great Spirit is changing things all around you. Once the whole land was owned by you and other Indian Nations. Now the white men have almost the whole country, and they are as numerous as the Pigeons in the spring. You who have been in Washington know this; but the poor Indians are dying off with the use of whiskey, while others are sent off across the Mississippi to make room for the white men. Not because the Great Spirit loves the white men more than the Indians, but because the white men are wise and send their children to school and attend to instructions, so as to know more than you do. They become wise and rich while you are poor and ignorant, but if you send your children to school they may become wise like the white men; they will also learn to worship the Great Spirit like the whites, and enjoy the prosperity they enjoy. I hope, and he, that you will open your ears and hearts to receive this advice, and you will soon get great light. But said he, I am afraid of you, I see but few of you go to listen to the Missionaries, who are now preaching here every night; they are anxious that you should hear the word of the Great Spirit and learn to be happy and wise, and to have peace among yourselves.

The 1837 Treaty of St. Peters was mostly negotiated by Maajigaabaw or “La Trappe” of Leech Lake and other chiefs from outside the territory ceded by that treaty. The chiefs from the ceded lands were given relatively few opportunities to speak. This created animosity between the Lake Superior and Mississippi Bands.Your Great Father is very sorry to learn that there are divisions among his red children. You cannot be happy in this way. Your Great Father hopes you will live in peace together, and not do wrong to your white neighbors, so that no reports will be made against you, or pay demanded for damages done by you. These things when they occur displease him very much, and I myself am ashamed of such things when I hear them. Your Great Father is determined to put a stop to them, and he looks that the Chiefs and Braves will help him, so that all the wicked may be brought to justice; then you can hold up your heads, and your Great Father will be proud of you. Can I tell him that he can depend upon his Chippeway children acting in this way.

One other thing, your Great Father is grieved that you drink whiskey, for it makes you sick, poor, and miserable, and takes away your senses. He is determined to punish those men who bring whiskey among you, and of this I will talk more at another time.

Stuart would become irritated after the treaty when the Ojibwe argued they did not cede Isle Royale in 1842. This lead to further negotiations and an addendum in 1844. The Grand Portage Band, who lived closest to Isle Royale, was not party to the 1842 negotiations.When I was in New York about three moons ago I found 800 blankets which were due you last year, which by some mismanagement you did not get. Your Great Father was very angry about it, and wished me to bring them to you, and they will be given you at the payment. He is determined to see that you shall have justice done you, and to dismiss all improper agents. He despises all who would do you wrong. Now I propose to buy your lands from Fond du Lac, at the head of Lake Superior, down Lake Superior to Chocolate River near Grand Island, including all the Islands in the limits of the United States, in the Lake, making the boundary on Lake Superior about 250 miles in extent, and extending back into the country on Lake Superior about 100 miles. Mr. Stuart showed the Chiefs the boundary on the map, and said you must not suppose that your Great Father is very anxious to buy your lands, the principal object is the minerals, as the white people will not want to make homes upon them. Until the lands are wanted you will be permitted to live upon them as you now do. They may be wanted hereafter, and in this event your Great Father does not wish to leave you without a home. I propose that the Fond du Lac lands and the Sandy Lake tract (which embrace a tract 150 miles long by 100 miles deep) be left you for a home for all the bands, as only a small part of the Fond du Lac lands are to be included in the present purchase. Think well on the subject and counsel among yourselves, but allow no black birds to disturb you, your Great Father is now willing and can do you great good if you will, but if not you must take the consequences. To-morrow at the fire of the gun you can come to the Council ground and tell me whether the proposal I make in the name of your Great Father is agreeable to you; if so I will do what I can for you, you have known me to be your friend for many years. I would not do you wrong if I could, but desire to assist you if you allow me to do so. If you now refuse it will be long before you have another offer.

October 1st. At the sound of the Cannon the Council met, and when all were ready for business, Shingoop, the head Chief of the Fond du Lac band, with his 2d and 3d Chiefs, came forward and shook hands with the Commissioner and others associated with him, then spoke as follows:

Zhingob (Balsam), also known as Nindibens, signed the 1837, 1842, and 1854 treaties as chief or head chief of Fond du Lac. The Zhingob on earlier treaties is his father. See Ely, ed. Schenck, The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. ElyMy friend, we now know the purpose you came for and we don’t want to displease you. I am very glad there are so many Indians here to hear me. I wish to speak of the lands you want to buy of me. I don’t wish to displease the Traders. I don’t wish to displease the half-breeds; so I don’t wish to say at once, right off. I want to know what our Great Father will give us for them, then I will think and tell you what I think. You must not tell a lie, but tell us what our Great Father will give us for our lands. I want to ask you again, my Father. I want to see the writing, and who it is that gave our Great Father permission to take our minerals. I am well satisfied of what you said about Blacksmiths, Carpenters, Schools, Teachers, &c., as to what you said about whiskey, I cannot speak now. I do not know what the other Chiefs will say about it. I want to see the treaty and the name of the Chiefs who signed. The Chief answered that the Indians had been deceived, that they did not so understand it when they signed it.

Mr. Stuart replied that this was all talk for nothing, that the Government had a right to the minerals under former treaty, yet their Great Father wishes now to pay for the minerals and purchase their lands.

The Chief said he was satisfied. All shook hands again and the Chief retired.

The next Chief who came forward was the “Great Buffalo” Chief of the La Pointe band. Had heavy epaulettes on his shoulders and a hat trimmed with tinsel, with a heavy string of bear claws about his neck, and said:-

“Big Buffalo (Chippewa),” 1832-33 by Henry Inman, after J.O. Lewis (Smithsonian).

My father, I don’t speak for myself only, but for my Chiefs. What you said here yesterday when you called us your children, is what I speak about. I shall not say what the other Chief has said, that you have heard already.

He then made some remarks about the Missionaries who were laboring in their country and thought as yet, little had been done. About the Carpenters, he said, that he could not tell how it would work, as he had not tried it yet.

We have not decided yet about the Farmers, but we are pleased at your proposal about Blacksmiths. Can it be supposed that we can complete our deliberations in one night. We will think on the subject and decide as soon as we can.

The great Antonaugen Chief came next, observing the usual ceremony of shaking hands, and surrounded by his inferior Chiefs, said:-

The great Ontonagon Chief is almost certainly Okandikan (Buoy), depicted here in a reproduction of an 1848 pictograph carried to Washington and reproduced by Seth Eastman. Okandikan is depicted as his totem symbol, the eagle (largest, with wing extended in the center of the image).

My father and all the people listen and I call upon my Great Father in Heaven to bear witness to the rectitude of my intentions. It is now five years since we have listened to the Missionaries, yet I feel that we are but children as to our abilities. I will speak about the lands of our band, and wish to say what is just and honorable in relation to the subject. You said we are your children. We feel that we are still, most of us, in darkness, not able fully to comprehend all things on account of our ignorance. What you said about our becoming enlightened I am much pleased; you have thrown light on the subject into my mind, and I have found much delight and pleasure thereby. We now understand your proposition from our Great Father the President, and will now wait to hear what our Great Father will give us for our lands, then we will answer. This is for the Antannogens and Ance bands.

Mr. Stuart now said, that he came to treat with the whole Chippeway Nation and look upon them all as one Nation, and said

I am much pleased with those who have spoken; they are very fine orators; the only difficulty is, they do not seem to know whether they will sell their lands. If they have not made up their minds, we will put off the Council.

Lac du Flambeau Chief, “the Great Crow,” came forward with the strict Indian formalities but had but little to say, as he did not come expecting to have any part in the treaty, but wished to receive his payment and go home.

The 2d Chief of this band wished to speak. He was painted red with black spots on each cheek to set off his beauty, his forehead was painted blue, and when he came to speak, he said:-

What the last Chief has said is all I have to say. We will wait to hear what your proposals are and will answer at a proper time.

Next came forward “Noden,” or the “Great Wind,” Chief of the Mill Lac band, and said:-

Noodin (Wind) is mentioned here as representing the Mille Lacs Band, though his village was usually on Snake River of the St. Croix.

I have talked with my Great Father in Washington. It was a pity that I did not speak at the St. Peters treaty. My father, you said you had come to do justice. We do not wish to do injustice to our relations, the half-breeds, who are also our friends. I have a family and am in a hurry to get home, if my canoes get destroyed I shall have to go on foot. My father, I am hurry, I came for my payment. We have left our wives and children and they are impatient to have us return. We come a great distance and wish to do our business as soon as we can. I hope you will be as upright as our former agent. I am sorry not to see him seated with you. I fear it will not go as well as it would. I am hurry.

Mr Stuart now said that he considered them all one nation, and he wished to know whether they wished to sell their lands; until they gave this answer he could do nothing, and as it regards any thing further he could say nothing, and said they might now go away until Monday, at the firing of the Cannon they might come and tell him whether they would sell their country to their Great Father.

We intend giving the remainder of the proceedings of the treaty in our next.

Green Bay Republican:

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 1842, Page 2.

(Treaty with the Chippeways Concluded.)

Monday morning three guns were fired as a signal to open the Treaty. When all things were in readiness, Mr. Stuart said:

I am glad you have now had time for reflection, and I hope you are now ready like a band of brothers to answer the question which I have proposed. I want to see the Nation of one heart and of one mind.

Shingoop, Chief of the Fond du Lac band, came forward with full Indian ceremony, supported on each side by the inferior Chiefs. He addressed the Chippeway nation first, which was not fully interpreted; then he turned to the Commissioner and said:

in this Treaty which we are about to make, it is in my heart to say that I want our friends the traders, who have us in charge provided for. We want to provide also for our friends the half-breeds – we wish to state these preliminaries. Now we will talk of what you will give us for our country. There is a kind of justice to be done towards the traders and half-breeds. If you will do justice to us, we are ready to-morrow to sign the treaty and give up our lands. The 2d Chief of the band remarked, that he considered it the understanding that the half-breeds and traders were to be provided for.

The Great Buffalo, of La Pointe band, and his associate Chiefs came next, and the Buffalo said:

My Father, I want you to listen to what I say. You have heard what one Chief has said. I wish to say I am hurry on account of keeping so many men and women here away from their homes in this late season of the year, so I will say my answer is in the affirmative of your request; this is the mind of my Chiefs and braves and young men. I believe you are a correct man and have a heart to do justice, as you are sent here by our Great Father, the President. Father, our traders are so related to us that we cannot pass a winter without them. I want justice to be done them. I want you and our Great Father to assist us in doing them justice, likewise our half-breed children – the children of our daughters we wish provided for. It seems to me I can see your heart, and you are inclined to do so. We now come to the point for ourselves. We wish to know what you will give us for our country. Tell us, then we will advise with our friends. A part of the Antaunogens band are with me, the other part are turned Christians and gone with the Methodist band, (meaning the Ance band at Kewawanon) these are agreed in what I say.

The Bird, Chief of the Ance band, called Penasha, came forward in the usual form and said:

My Father, now listen to what I have to say. I agree with those who have spoken as far as our lands are concerned. What they say about our traders and half-breeds, I say the same. I speak for my band, they make use of my tongue to say what they would say and to express their minds. My Father, we listen to what you will offer for our country, then we will say what we have to say. We are ready to sell our country if your proposals are agreeable. All shook hands – equal dignity was maintained on each side – there was no inclination of the head or removing the hat – the Chiefs took their seats.

The White Crow next appeared to speak to the Great Father, and said:-

White Crow is apparently unaware that in the eyes of the United States, his lands, (Lac du Flambeau) were already sold five years earlier at St. Peters. Clearly, the notion of buying and selling land was not understood by him in the same way it was understood by Stuart.

Listen to what I say. I speak to the Great Father, to the Chiefs, Traders, and Half-breeds. You told us there was no deceit in what you say. You may think I am troublesome, but the way the treaty was made at St. Peters, we think was wrong. We want nothing of the kind again. We think you are a just man. You have listened to those Chiefs who live on Lake Superior. What I say is for another portion of country. It appears you are not anxious to buy the lands where I live, but you prefer the mineral country. I speak for the half-breeds, that they may be provided for: they have eaten out of the same dish with us: they are the children of our sisters and daughters. You may think there is something wrong in what I say. As to the traders, I am not the same mind with some. The old traders many years ago, charged us high and ought to pay us back, instead of bringing us in debt. I do not wish to provide for them; but of late years they have had looses and I wish those late debts to be paid. We do not consider that we sell our lands by saying we will sell them, so we consent to sell if your proposals are agreeable. We will listen and hear what they are.

Several others of the Chiefs spoke well on the subject, but the substance of all is contained in the above.

Hole-in-the-day, who is at once an orator and warrior, came forward; he had an Arkansas tooth pick in his hand which would weigh one or two pounds, and is evidently the greatest and most intelligent man in the nation, as fine a form of body, head and face, as perhaps could be found in any country.

Father, said he, I arise to speak. I have listened with pleasure to your proposal. I have come to tie the knot. I have come to finish this part of the treaty, and consent to sell our country if the offers of the President please us. Then addressing the Chiefs of the several bands he said, the knot is now tied, and so far the treaty is complete, not to be changed.

Zhaagobe (“Little” Six) signed as first chief from Snake River, and he is almost certainly the “Big Six” mentioned here. Several Ojibwe and Dakota chiefs from that region used that name (sometimes rendered in Dakota as Shakopee).

Big Six now addressed the whole Nation in a stream of eloquence which called down thunders of applause; he stands next to Hole-in-the-day in consequence and influence in the nation. His motions were graceful, his enunciation rather rapid for a fine speaker. He evidently possesses a good mind, though in person and form he is quite inferior to Hole-in-the-day. His speech was not interpreted, but was said to be in favor of selling the Chippeway country if the offer of the Government should meet their expectations, and that he took a most enlightened view of the happiness which the nation would enjoy if they would live in peace together and attend to good counsel.

Mr. Stuart now said,

I am very happy that the Chippewa nation are all of one mind. It is my great desire that they should continue to for it is the only way for them to be happy and wise. I was afraid our “White Crow” was going to fly away, but am happy to see him come back to the flock, so that you are all now like one man. Nothing can give me greater pleasure than to do all for you I can, as far as my instructions from your Great Father will allow me. I am sorry you had any cause to complain of the treaty at St. Peters. I don’t believe the Commissioner intended to do you wrong, but perhaps he did not know your wants and circumstances so as to suit. But in making this treaty we will try to reconcile all differences and make all right. I will now proceed to offer you all I can give you for your country at once. You must not expect me to alter it, I think you will be pleased with the offer. If some small things do not suit you, you can pass them over. The proposal I now make is better than the Government has given any other nation of Indians for their lands, when their situations are considered. Almost double the amount paid to the Mackinaw Indians for their good lands. I offer more than I at first intended as I find there are so many of you, and because I see you are so friendly to our Government, and on account of your kind feelings for the traders and half-breeds, and because you wish to comply with the wishes of your Great Father, and because I wish to unite you all together. At first I thought of making your annuities for only twenty years but I will make them twenty-five years. For twenty-five years I will offer you the following and some items for one year only.

$12,500 in specie each year for 25 years, $312,500

10,500 in goods ” ” ” ” ” 262,500

2,000 in provisions and tobacco, do. 50,000$625,000

This amount will be connected with the annuity paid to a part of the bands on the St. Peters treaty, and the whole amount of both treaties will be equally distributed to all the bands so as to make but one payment of the whole, so that you will be but one nation, like one happy family, and I hope there will be no bad heart to wish it otherwise. This is in a manner what you are to get for your lands, but your Great Father and the great Council at Washington are still willing to do more for you as I will now name, which you will consider as a kind of present to you, viz:

2 Blacksmiths, 25 years, $2000, $50,000

2 Farmers, ” ” 1200, 30,000

2 Carpenters, ” ” 1200, 30,000

For Schools, ” ” 2000, 50,000

For Plows, Glass, Nails, &c. for one year only, 5000

For Credits for one year only, 75,000

For Half-breeds ” ” ” 15,000$255,000

Total $880,000

With regards to the claims. I will not allow any claim previous to 1822; none which I deem unjust or improper. I will endeavor to do you justice, and if the $75,000 is not all required to pay your honest debts, the balance shall be paid to you; and if but a part of your debts are paid your Great Father requires a receipt in full, and I hope you will not get any more credits hereafter. I hope you have wisdom enough to see that this is a good offer. The white people do not want to settle on the lands now and perhaps never will, so you will enjoy your lands and annuities at the same time. My proposal is now before you.

The Fond du Lac Chief said, we will come to-morrow and give our answer.

October 4th, Mr. Stuart opened the Council.

Clement Hudon Beaulieu, was about thirty at this time and working his way up through the ranks of the American Fur Company at the beginning of what would be a long and lucrative career as an Ojibwe trader. His influence would have been very useful to Stuart as he was a close relative of Chief Gichi-Waabizheshi. He may have also been related to the Lac du Flambeau chiefs–though probably not a grandson of White Crow as some online sources suggest.

We have now met said he, under a clear sun, and I hope all darkness will be driven away. i hope there is not a half-breed whose heart is bad enough to prevent the treaty, no half-breed would prevent he treaty unless he is either bad at heart or a fool. But some people are so greedy that they are never satisfied. I am happy to see that there is one half-breed (meaning Mr. Clermont Bolio) who has heart enough to advise what is good; it is because he has a good heart, and is willing to work for his living and not sponge it out of the Indians.

We now heard the yells and war whoops of about one hundred warriors, ornamented and painted in a most fantastic manner, jumping and dancing, attended with the wild music usual in war excursions. They came on to the Council ground and arrested for a time the proceedings. These braves were opposed to the treaty, and had now come fully determined to stop the treaty and prevent the Chiefs from signing it. They were armed with spears, knives, bows and arrows, and had a feather flag flying over ten feet long. When they were brought to silence, Mr. Stuart addressed them appropriately and they soon became quiet, so that the business of the treaty proceeded. Several Chiefs spoke by way of protecting themselves from injustice, and then all set down and listened to the treaty, and Mr. Stuart said he hoped they would understand it so as to have no complaints to make afterwards.

The provisions of the treaty are the same as made in the proposals as to the amount and the manner of payment. The Indians are to live on the lands until they are wanted by the Government. They reserve a tract called the Fond du Lac and Sandy Lake country, and the lands purchased are those already named in the proposals. The payment on this treaty and that of the St. Peters treaty are to be united, and equal payments made to all the bands and families included in both treaties. This was done to unite the nation together. All will receive payments alike. The treaty was to be binding when signed by the President and the great Council at Washington. All the Chiefs signed the treaty, the name of Hole-in-the-day standing at the head of the list, and it is said to be the greatest price paid for Indian lands by the United States, their situation considered, though the minerals are said to be very valuable.

The Commissioner is said to have conducted the treaty in a very just, impartial and honorable manner, and the Indians expressed the kindest feelings towards him, and the greatest respect for all associated with him in negotiating the treaty and the best feelings towards their Agent now about leaving the country, and for the Agents of the American Fur Company and for the traders. The most of them expressed the warmest kind of feelings toward the Missionaries, who had come to their country to instruct them out of the word of the Great Spirit. The weather was very pleasant, and the scene presented was very interesting.

American Fur Company: 1834 Reinvention of La Pointe

October 4, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

The below image from the Wisconsin Historical Society is a storymap showing La Pointe in 1834 as abstract squiggles on an oversized Madeline Island surrounded by random other Apostle Islands, Bayfield Peninsula, Houghton Point, Chequamegon Bay, Long Island, Bad River, Saxon Harbor, and Montreal River.

“Map of La Pointe”

“L M Warren”

“~ 1834 ~”

Wisconsin Historical Society

citing an original map at the New York Historical Society

My original (ongoing) goal for publishing this post is to find an image of the original 1834 map by Lyman Marcus Warren at the New York Historical Society to explore what all of his squiggles at La Pointe represented in 1834. Instead of immediately achieving my original goal, this post has become the first of a series exploring letters in the American Fur Company Papers by/to/about Warren at La Pointe.

New York Historical Society

American Fur Company Papers: 1831-1849

America’s First Business Monopoly

#16,582

Map of Lapointe

by L M Warren

~ 1834 ~

New York Historical Society

scanned as Gale Document Number GALE|SC5110110218

#36

Lapointe Lake Superior

September 20th ’34

Ramsey Crooks Esqr

Dear Sir

Starting in 1816, the American Fur Company (AFC) operated a trading post by the “Old Fort” of La Pointe near older trading posts built by the French in 1693 and the British in 1793.

In 1834, John Jacob Astor sold his legendary AFC to Ramsay Crooks and other trading partners, who in turn decided to relocate the AFC’s base of operations at Mackinac Island to Madeline Island, where our cartographer Lyman Marcus Warren was employed as the AFC’s trader at La Pointe.

Instead of improving any of the older trading posts on Madeline Island, Warren decided to move La Pointe to the “New Fort” of 1834 to build new infrastructure for growing business demands.

GLO PLSS 1852 survey detail of the “Am Fur Co Old Works” near Old Fort.

on My Way In as Mr Warren was was detained So Long at Mackinac I did not Wait for him at this Place as time was of So Much Consequence to me to Get my People Into the County that I Proceeded Immediately to Fond Du Lac with the Intention with the Intention of Returning to this Place When I Had Sent the Outfit off but When I Got There I Had News from the Interior Which Required me to Go In and Settle the Business there; the [appearance?] In the Interior for [????] is tolerable. Good Provision there is [none?] Whatever I [have?] Seen the [Country?] [So?] Destitute. The Indians at [Fort?] [?????] Disposed to give me Some trouble when they found they have to Get no Debts and buy their amunition and tobacco and not Get it For Nothing as usual but at Length quieted down [?????] and have all gone off to their Haunts as usual.

I Received your Instructions contained in your Circular and will be very Particular In Following them. The outfits were all off when I Received them but the men’s acts and the Invoices of the Goods Had all been Settled according to your Wishes and Every Care Will be taken not to allow the men to get In Debt the Clerks Have Strict orders on the Subject and it is made known to them that they will be Held for any of the Debts the men may Incur.

I Enclose to you the Bonds Signed and all the Funds we Received from Mr Johnston Excepting those Which Had been given to the Clerks and I could not Get them Back In time to Send them on at Present.

Mr Warren And myself Have Committed on What is to be done at this Place and I am certain all that Can be done Will be done by him. I leave here tomorrow For the Interior of Fond Du Lac Where I must be as Soon as possible.

I have written to Mr Schoolcraft as he Inquested me. Mr Brewster’s men would not Give up their [??????] and [???] [????] is [??] [?????] [????] [????] [to?] [???????] [?????] [to?] [persuade?] [more?] People for Keeping [his?] [property?] [Back?] [and] [then?] [???] by some [???] ought to be sent out of the Country [??] they are [under?] [the?] [???] [?] and [Have?] [no?] [Right?] to be [????] [????] they are trouble [????] [???] [their?] [tongues?].

GLO PLSS 1852 survey detail of the AFC’s new “La Point” (New Fort) and the ABCFM’s “Mission” (Middleport).

The Site Selected Here For the Buildings by Mr Warren is the Best there is the Harbour is good and I believe the work will go on well.

as For the Fishing we Will make Every Inquiry on the Subject and I Have no Doubt on My Mind of Fairly present that it will be more valuable than the Fur trade.

In the Month of January I will Write you Every particular How our affairs stand from St Peters. Bailly Still Continues to Give our Indians Credits and they Bring Liquor from that Place which they Say they Get from Him.

Please let Me know as Early as possible with Regard to the Price of Furs as it will Help me In the trade. the Clerks all appear anxious to do their Duty this year as the wind is now Falling and I am In Haste I Will Write you Every particular of our Business In January.

Wishing that God may Long Prosper you and your family.

In health and happiness.

I remain most truly,

and respectfully

yours $$

William A. Aitken

#42

Lake Superior

LaPointe Oct 16 1834

Ramsey Crooks Esqr

Agent American Fur Co

Honoured Sir

Your letter dated Mackinac Sept [??] reached me by Mr Chapman’s boat today.-

I will endeavour to answer it in such a manner as will give you my full and unreserved opinion on the different subjects mentioned in it.

I feel sorry to see friend Holiday health so poor, and am glad that you have provided him a comfortable place at the Sault. As you remark it is a fortunate circumstance that we have no opposition this year or we would certainly have made a poor resistance. I can see no way on which matters would be better arranged under existing circumstances than the way in which you have arranged it. If Chaboillez, and George will act in unison and according to your instructions, they will do well, but I am somewhat affeared, that this will not be the case, as I think George might perhaps from jealously refuse to obey Chaboillez or give him the proper help. Our building business prevents me from going there myself. I suppose you have now received my letter of last Sept, in which I mentioned that I had kept the Doctor here. I shall send him in a few days to see how matters comes on at the Ance. The Davenports are wanted at present in FDLac should it be necessary to make any alteration. I shall leave the Doctor at the Ance.

Undated photograph of the ABCFM Presbyterian Mission Church at it’s original 1830s location along the shoreline of Sandy Bay.

~ Madeline Island Museum

In addition to the AFC’s new La Pointe, Warren was also committed to the establishment of a mission for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) as a condition of his 1827 Deed for Old La Pointe from his Chippewa wife’s parents; Madeline & Michel Cadotte.

Starting in 1830, the ABCFM built a Mission at La Pointe’s Middleport (second French fort of 1718), where they were soon joined by a new Catholic Mission in 1835.

Madeline Island was still unceded territory until the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe. The AFC and ABCFM had obtained tribal permissions to build here via Warren’s deed, while the Catholics were apparently grandfathered in through French bloodlines from earlier centuries.

I think we will want about 2 Coopers but as you suggest I if they may be got cheaper than the [????] [????]. The Goods Mr Hall has got is for his own use that is to say to pay his men [??]. The [??] [??????] [has?] to pay for a piece of land they bot from an Indian woman at Leech Lake. As far as my information goes the Missionaries have never yet interfered with our trade. Mr Hall’s intention is to have his establishment as much disconnected with regular business as he possibly can and he gets his supplies from us.

[We?] [have?] received the boxes [Angus?] [??] [???]. [You?] mention also a box, but I have not yet received it. Possible it is at the Ance.

The report about Dubay has no doubt been exaggerated. When with me at the Ance he mentioned to me that Mr Aitkin told him he had better tell the Indians not to kill their beaver entirely off and thereby ruin their country. The idea struck me as a good one and as far as I recollect I told him, it would perhaps be good to tell them so. I have not yet heard from any one, that he has tried to prevent the Indians from paying their old Debts and I should not be astonished to fend the whole is one of those falsehoods which Indians are want to use to free themselves from paying old Debts. I consider Dubay a pretty active man, but the last years extravagancies have made it necessary to have an eye upon him to prevent him from squandering.

My health had been somewhat impaired by my voyage from the Sault to this place. Instead of going to Lac Du Flambeau myself as I intended I sent the Doctor. He has just now returned and tells me that Dubay gets along pretty well, though there were some small difficulties which toke place, but which the Dr settled. The prospect are very discouraging, particularly on a/c of provisions. We have plenty opposition and all of them with liquor in great abundance. It is provoking to see ourselves restricted by the laws from taking in liquor while our opponents deal in it as largely as ever. The traders names are as far as could be ascertained Francois Charette and [Chapy?]. The liquor was at Lac du Flambeau while the Doctor was there. I have furnished Dubay with means to procure provisions, as there is actually not 1 Sack of Corn or Rice to be got.

The same is the case on Lac Courtoreilie and Folleavoigne no provisions and a Mr Demarais on the Chippeway River gives liquor to the Indians.

You want my ideas upon the fishing business. If reliance can be put in Mr Aitkin’s assertions we will at least want the quantity of Net thread mentioned in our order. Besides this we will want for our fishing business 200 Barrels Flour, [??] Barrels Pork, 10 Kegs Butter, 1000 Bushels Corn, [??] Barrels Lard, 10 or 11 Barrels Tallow.

Besides this we want over and above the years supply an extra supply for our summer Establishments. say about 80 Barrels Flour, 30 Barrels Pork, 1500 # Butter, 400 Bushels Corn, 5 Barrels Lard, 5 Barrels Tallow. This will is partly to sell. be sold.

Mr Roussain will be as good as any if not better in my opinion for our business than Holiday. Ambrose Davenport might take the charge of the Ance but Roussain will be more able on account of his knowledge in fishing. I would recommend to take him as a partner. say take Holidays share if he could not be got for less.

I have not done much yet toward building. The greatest part of my men have been in the exterior to assist our people to get in. But they have now all arrived. We have got about 4 acres of land cleared, a wintering house put up and a considerable quantity of boards sawed. Mr Aitkin did not supply me with two Carpenters as he promised at Mackinac. I will try to get along as well as I can without them. I engaged Jos Dufault and Mr Aitkin brot me one of Abbott’s men, who he engaged. But I will still be under the necessity of hiring Mr Campbell of the mission to make our windows sashes and to superintend The framing of the buildings. Mr Aitkins have done us considerable damage by not fulfilling his promise in this respect. I told you in Mackinac that Mr Aitkin was far from being exact in business. Your letter to him I will forward by the first opportunity. I think it will have a good effect and you do right in being thus plain in stating your views. His contract deserves censure, and I will hope that your plain dealing with him will not be lost upon him. Shall I beg you to be as faithfull to me by giving me the earliest information whenever you might disapprove of any transaction of mine.

Photograph of La Pointe from Mission Hill circa 1902.

~ Wisconsin Historical Collections, Volume XVI, page 80.

I have received a supply of provisions from Mr Chapmann which will enable me to get through this season. The [?] [of?] [???] [next?], the time you have set for the arrival of the Schooner, will be sufficient, early for our business. The Glass and other materials for finishing of the buildings would be required to be sent up in the first trip but if [we?] [are?] [??] better to have them earlier. If these articles could be sent to the Sault early in the Spring a boat load might be formed of [Some?] and Provisions and sent to the Ance. From there men could be spared at that season of the year to bring the load to this place. In that way there would be no heavy expense incurred and I would be able to have the buildings in greater forwardness.

If the plan should meet your approbation please let me know by the winter express. While Mr Aitkin was here we planned out our buildings. The House will be 86 feet by 26 feet in the clear, the two stores will be put up agreeable to your Draft. We do not consider them to large.

I am afraid I shall not be able to build a wharf in season, but shall do my best to accomplish all that can be done with the means I have.

Undated photograph of Captain John Daniel Angus’ boat at the ABCFM mission dock.

~ Madeline Island Museum

I would wish to call your attention towards a few of the articles in our trade. I do not know how you have been accustomed to buy the Powder whether by the Keg or pound. If a keg is estimated at 50#, there is a great deception for some of our kegs do not contain more than 37 or 40 #s.

Our Guns are very bad particularly the barrels. They splint in the inside after been fired once or twice.

Our Holland twine is better this year than it has been for Years. One dz makes about 20 fathoms, more than last year. But it would be better if it was bleached. The NW Company and old Mr Ermantinger’s Net Thread was always bleached. It nits better and does not twist up when put into the water. Our maitre [??] [???] are some years five strand. Those are too large we have to untwist them and take 2 strands out. Our maitre this year are three strand they are rather coarse but will answer. They are not durable nor will they last as long as the nets of course they have to be [renewed?]. The best maitres are those we make of Sturgeon twine. We [?????] the twine and twist it a little. They last twice as long as our imported maitres. The great object to be gained is to have the maitres as small as possible if they be strong enough. Three coarse strands of twisted together is bulky and soon nits.

Our coarse Shoes are not worth bringing into the country. Strong sewed shoes would cost a little more but they would last longer. The [Booties?] and fine Shoes are not much better.

Our Teakettles used to have round bottoms. This year they are flat. They Indians always prefer the round bottom.

In regard to the observations you have made concerning the Doctor’s deviating from the instructions I gave him on leaving Mackinac, I must in justice to him say that I am now fully convinced in my own mind that he misunderstood me entirely, merely by an expression of mine which was intended by me in regard to his voyage from Mackinac to the Sault but by him was mistaken for the route through Lake Superior. The circumstances has hurt his feelings much and as he at all times does his best for the Interest of the Outfit I ought to have mentioned in my last letter, but it did not strike my mind at that time.

Detail from Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques Nicolas Bellin in 1744.

When Mr Aitkin was here he mentioned to me some information he had obtained from somebody in Fond du Lac who had been in the NW Co service relating to a remarkable good white fish fishery on the “Milleau” or “Millons” Islands (do not know exactly the proper name). They lay right opposite to Point Quiwinau. a vessel which passes between the island and the point can see both. Among Mr Chapmann’s crew here there is an old man who tells me that he knew the place well, he says the island is large, say 50 or 60 miles. The Indian used to make their hunts there on account of the great quantity of Beaver and Reindeer. It is he says where the NWest Co used to make their fishing for Fort William. There is an excellent harbour for the vessel it is there where the largest white fish are caught in Lake Superior. Furthermore the old man says the island is nearer the American shore than the English. Some information might be obtained from Capt. McCargo. If it proves that we can occupy the grounds I have the most sanguine hopes that we shall succeed in the fisheries upon a large scale.

I hope you will gather all the information you can on the subject. Particular where the line runs. If it belongs to the Americans we must make a permanent post on the Island next year under the charge of an active person to conduct the fisheries upon a large scale.

Jh Chevallier one of the men I got in Mackinac is a useless man, he has always been sick since he left Sault. Mr Aitkin advised me to send him back in Chapman’s Boat. I have therefore send him out to the care of Mr Franchere.