An Incident of Chegoimegon

November 26, 2016

By Amorin Mello

This is a reproduction of “An Incident of Chegoimegon – 1760” from Report and Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: For the years 1877, 1878 and 1879. Volume VIII., pages 224-226.

—

AN INCIDENT OF CHEGOIMEGON – 1760.*

—

We have been permitted to extract the following from the journal of a gentleman who has seen a large portion of the country to the north and west of this place, and to whose industry our readers have been often indebted for information relating to the portion of country over which he has passed, and to transactions among the numerous tribes, within the limits of this territory, which tend to elucidate their characteristics, and lay open the workings of their untaught minds:

Detail of Isle de la Ronde from Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin; published in Charlevoix’s Histoire et Description Générale de Nouvelle France, Paris, 1744.

Monecauning (abbreviated for “Monegoinaic-cauning,” the Woodpecker Island, in Chippewa language) – which is sometimes called Montreal Island, Cadott’s Island, or Middle Island, and is one of “the Apostles” mentioned by Charlevoix. it is situated in Lake Superior, about ninety miles from Fond du Lac, at the extremity of La Pointe, or Point Chegoimegon.

On this island the French Government had a fort, long previous to its surrender to the English, in 1763. It was garrisoned by regular soldiers, and was the most northern post at which the French king had troops stationed. It was never re-occupied by the English, who removed everything valuable to the Sault de St. Marie, and demolished the works. It is said to have been strongly fortified, and the remains of the works may yet be seen.

In the autumn of 1760, all of the traders except one, who traded from this post, left it for their wintering grounds. He who remained had with him his wife, who was a lady from Montreal, his child – a small boy, and one servant. During the winter, the servant, probably for the purpose of plunder, killed the trader and his wife; and a few days after their death, murdered the child. He continued at the fort until the spring. When the traders came, they enquired for the gentleman and his family; and were told by the servant, that in the month of March, they left him to go to their sugar camp, beyond the bay, since which time he had neither seen nor heard them. The Indians, who were somewhat implicated by this statement, were not well satisfied with it, and determined to examine into its truth. They went out and searched for the family’s tracks; but found none, and their suspicions of the murderer increased. They remained perfectly silent on the subject; and when the snow had melted away, and the frost left the ground, they took sharp stakes and examined around the fort by sticking them into the ground, until they found three soft spots a short distance from each other, and digging down they discovered the bodies.

The servant was immediately seized and sent off in an Indian canoe, for Montreal, for trial. When passing the Longue Saut, in the river St. Lawrence, the Indians who had him in charge, were told of the advances of the English upon Montreal, and that they could not in safety proceed to that place. They at once became a war party, – their prisoner was released, and he joined and fought with them. Having no success, and becoming tired of the war, they sought their own land – taking the murderer with them as one of their war party.

They had nearly reached the Saut de St. Marie, when they held a dance. During the dance, as is usual, each one “struck the post,” and told, in his manner, of his exploits. The murderer, in his turn, danced up to the post, and boasted that he had killed the trader and his family – relating all the circumstances attending the murder. The chief heard him in silence, saving the usual grunt, responsive to the speaker. The evening passed away, and nothing farther occurred.

The next day the chief called his young men aside, and said to them: “Did you not hear this man’s speech last night? He now says that he did the murder with which we charged him. He ought not to have boasted of it. We boast of having killed our enemies – never our friends. Now he is going back to the place where committed the act, and where we live – perhaps he will again murder. He is a bad man – neither we nor our friends are safe. If you are of my mind, we will strike this man on the head.” They all declared themselves of his opinion, and determined that justice should be rendered him speedily and effectually.

They continued encamped, and made a feast, to which the murderer was invited to partake. They filled his dish with an extravagant quantity, and when he commenced his meal, the chief informed him, in a few words, of the decree in council, and that as soon as he had finished his meal, either by eating the whole his dish contained, or as much as he could, the execution was to take place. The murderer, now becoming sensible of his perilous situation, from the appearance of things around him, availed himself of the terms of the sentence he had just heard pronounced, and did ample justice to the viands. He continued, much to the discomfiture of the “phiz” of justice (personified by the chief, who all the while sat smoking through his nose), eating and drinking until he had sat as long as a modern alderman at a corporation dinner. But it was of no avail – when he ceased eating he ceased breathing.

The chief cut up the body of the murderer, and boiled it for another feast – but his young men would touch none of it – they said, “he was not worthy to be eaten – he was worse than a bad dog. We will not taste him, for if we do, we shall be worse than dogs ourselves.”

Mr. Morrison, who gave me the above relation, told me he had it from a very old Indian, who was present at the death of the murderer.

* – This paper was originally published in the Detroit Gazette, Aug. 30, 1822. Hon. C. C. Throwbridge of Detroit, a resident of that place for sixty years, states that Mr. Schoolcraft, without doubt, contributed this sketch to the Gazette; that Mr. Schoolcraft, at the time of its publication, was residing at the Saut St. Marie: and Mr. Morrison, who was one of Mr. Astor’s most trusted agents at “L’Anse Qui-wy-we-nong,” came down to Mackinaw every summer, and thus gave Mr. Schoolcraft the information.

L. C. D.

Comic Book

September 24, 2016

To whom it may concern,

One of the biggest complaints I get about Chequamegon History from friends and family is that the posts on the website are too densely-packed with historical information to be understandable to those who don’t have extensive background in the early history of this area. One comment, from my brother, went something like this:

You and Amorin need to write more clickbait stuff like “Top 10 Chequamegon Villains Compared to Game of Thrones Characters.” Otherwise only historians will read it.

While Cersei Lannister seems unlikely to appear on this site any time soon, my brother has a point. Not everyone who is interested in this history has hours of leisure time for diving into Warren, Schoolcraft, and old speeches and letters. While the introductory texts have gotten better in recent years (Patty Loew’s Indian Nations of Wisconsin and Howard Paap’s Red Cliff being notable examples), most of the mainstream secondary literature about this area’s history remains riddled with inaccuracies and misconceptions that offer little in the way of a bridge to the pre-1860 primary sources.

A couple years ago, the idea of a graphic novel came to me as a way to tackle this problem of access. Starting on Inkscape and finishing with pen and paper, I scratched out thirty pages of the first chapter of what could be a book about the American colonization of Chequamegon (c.1795-1855) and how it impacted the people who lived here. I quickly came to several realizations:

- A graphic novel on this topic can and should be done, but it needs to be awesome, not mediocre.

- It will not be able to get beyond mediocre unless people who actually do this kind of thing for a living take it over.

- Chequamegon History has enough material to easily make this thing exceed 200-300 pages.

- I don’t know if I’ve watched Little Big Man too many times or if the old stereotypes are too hard to shake, but transcribing old documents does not make one able to write cross-cultural 19th-century dialog. It’s hard. If most of the characters in this story are Ojibwe people, someone who can write a good joke, sexy pickup line, or solemn speech in realistic Ojibwe rhetorical style is desperately needed on this project. Otherwise it will just be the same old “Cowboys and Indians” crap, which is exactly what this shouldn’t be. The characters need to be real and multi-dimensional.

- There are many directions/perspectives this project could take that would be interesting. My brain always tends toward written documents and Euro/Western historical thinking, but a diverse group of people could make something like this a lot richer.

- My knowledge of of 18th and 19th-century clothing, material culture and manners is woefully limited.

- I never really did learn how to draw basic shadows, birds, and perspectives.

- Comic-Sans is a terrible font.

Anyways, the rough draft of Chapter One has been sitting on my shelf for over a year collecting dust. Finally, I have the courage to put it up here in all its imperfect glory:

Click to download the full 34-page pdf.

This does not mean this project is actually happening any time soon–at least not with my involvement. However, I am curious what people think. Does there need to be a Chequamegon History graphic novel? What should it cover? Who should do it?

~Leo

Martin Beaser

August 9, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

November 1888

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume IX, No.1, pages 24-27.

Martin Beaser.

Portrait of Martin Beaser on page 24.

On the fifth day of July 1854, Asaph Whittlesey and George Kilborn left La Pointe, in a row-boat, with the design of finding a “town site” on some available point near the “head of the bay.” At five o’clock P.M. of the same day they landed at the westerly limit of the present town site of Ashland. As Mr. Whittlesey stepped ashore, Mr. Kilborn exclaimed, “Here is the place for a big city!” and handing his companion an axe, he added, “I want you to have the honor of cutting the first tree in a way of a settlement upon the town site.” And the tree thus felled formed one of the foundation logs in the first building in the place. Such is the statement which has found its way into print as to the beginning of Ashland. But the same account adds: “Many new-comers arrived during the first few years after the settlement; among them Martin Beaser, who located permanently in Ashland in 1856, and was one of its founders.”1 How this was will soon be explained.

The father of the subject of this sketch, John Baptiste Beaser, was a native of Switzerland, educated as a priest, but never took orders. He came to America, reaching Philadelphia about the year 1812, where he married Margaret McLeod. They then moved to Buffalo, in one of the suburbs of which, called Williamsville, their son Martin was born, on the twenty-seventh of October, 1822. The boy received his early education in the common schools of the place, when, at the age of fourteen, he went on a whaling voyage, sailing from New Bedford, Massachusetts. His voyage lasted four years; his second voyage, three years; the last of which was made in the whaleship Rosseau, which is still afloat, the oldest of its class in America.

The young man went out as boat-steerer on his second voyage, returning as third mate. During his leisure time on shipboard and the interval between the two voyages, he spent in studying the science of navigation, which he successfully mastered. On his return from his fourth years’ cruise in the Pacific and Indian oceans, he was offered the position of second mate on a new ship then nearing completion and which would be ready to sail in about sixty days. He accepted the offer. They would notify him when the ship was ready, and he would in the meantime visit his mother, then a widow, residing in Buffalo. Accordingly, after an absence of seven years, he returned to his native city, spending the time in renewing old acquaintances and relating the varied experience of a whaler’s life. He had rare conversational powers, holding his listeners spell-bound at the recital of some thrilling adventure. A journal kept by him during his voyages and now in the possession of his family, abounds in hair-breadth escapes from savages on the shores of some of the South sea islands and the perils of whale-fishing, of which he had many narrow escapes. The time passed quickly, and he anxiously awaited the summons to join his ship. Leaving the city for a day the expected letter came, but was carefully concealed by his mother until after the ship had sailed, thus entirely changing the future of his life.

“… Martin, a sailor just from the whaling grounds of the Northwest Coast …”

Disappointed in his aspirations to command a ship in the near future, as he had reasons to hope from the rapid promotions he had already received – from a boy before the mast to mate of a ship in two voyages – and yielding to his mother’s wish not to leave home again, he engaged in sailing on Lake Erie from Buffalo to Detroit until 1847, when he went in the interest of a company in the latter city to Lake Superior for the purpose of exploring the copper ranges in the northern peninsula of Michigan. He coasted from Sault Ste. Marie to Ontonagon in a bateau. Remaining in the employ of the company about a year, he then engaged in a general forwarding and commission business for himself.

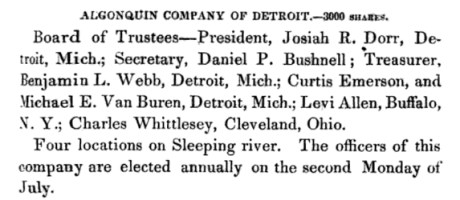

“Algonquin Company of Detroit.”

~ Reports of Wm. A. Burt and Bela Hubbard, by T. W. Bristol, 1846, page 97.

~ A History of the Northern Peninsula of Michigan and Its People: Volume 1, by Alvah Littlefield Sawyer, 1911, page 222.

Mr. Beaser was largely identified with the early mining interests of Ontonagon county, being instrumental in opening up and developing some of the best mines in that district.

In 1848 he was married in Cattaraugus county, New York, in the town of Perrysburgh, to Laura Antionette Bebee. The husband and wife the next spring went west, going to Ontonagon by way of Detroit. The trip from buffalo lasted from the first day of May to the sixth of June, they being detained at the “Soo” two weeks on account of the changing of the schooner Napoleon into a propeller, in which vessel, after a voyage of six days, they reached Ontonagon.

Here Mr. Beaser resided for seven years in the same business of forwarding and commission, furnishing frequently powder and candles to the miners by the ton. He was a portion of the this time associated with Thomas B. Hanna, formerly of Ohio. They then sold out their interest – Mr. Beaser going in company with Augustus Coburn and Edward Sayles to Superior, at the head of the lake, taking a small boat with them and Indian guides. Thus equipped they explored the region of Duluth, going up the Brule and St. Louis rivers. They then returned to La Pointe, going up Chaquamegon bay; and having their attention called to the site of what is now Ashland, on account of what seemed to be its favorable geographical position. As there had been some talk of the feasibility of connecting the Mississippi river and Lake Superior by a ship canal, it was suggested to them that this point would be a good one for its eastern terminus. Another circumstance which struck them was the contiguity of the Penokee iron range. This was in 1853. The company then returned to Ontonagon.

Closing up his business at the latter place, Mr. Beaser decided to return to the bay of Chaquamegon to look up and locate the town site on its southern shore. In the summer of 1854, on arriving there, he found Mr. Whittlesey and Mr. Kilborn on the ground. He then made arrangement with them by which he (Mr. Beaser) was to enter the land, which he did at Superior, where the land office was then located for that section. The contract between the three was, that Mr. Whittlesey and Mr. Kilborn were to receive each an eighth interest in the land, while the residue was to go to Mr. Beaser. The patent for the land was issued to Schuyler Goff, as county Judge of La Pointe county, Wisconsin, who was the trustee for the three men, under the law then governing the location of town sites.

La Pointe County Judge Schuyler Goff was issued this patent for 280.53 acres on June 23rd, 1862, on behalf of Martin Beaser, Asaph Whittlesey, and George Kilburn.

~ General Land Office Records

Mr. Beaser afterwards got his deed from the judge to his three-quarters’ interest in the site.

Beaser named Ashland in honor of the Henry Clay Estate in Kentucky.

~ National Park Service

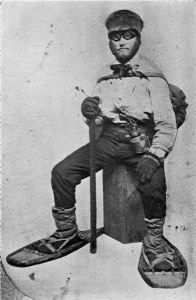

In January, 1854, Mr. Beaser having previously engaged a topographical engineer, G.L. Brunschweiler, the two, with a dog train and two Indians, made the journey from Ontonagon to the proposed town site, where Mr. Brunschweiler surveyed and platted2 a town on the land of the men before spoken of as parties in interest, to which town Mr. Beaser gave the name of Ashland. These three men, therefore, were the founders of Ashland, although afterwards various additions were made to it.

Mr. Beaser did not bring his family to Ashland until the eighth of September, 1856. He engaged in the mercantile business there until the war broke out, and was drowned in the bay while attempting to come from Bayfield to Ashland in an open boat, during a storm, on the fourth of November, 1866. He was buried on Madeline island at La Pointe. He was “closely identified with enterprises tending to open up the country; was wealthy and expended freely; was a man of fine discretion and good, common sense.” He was never discouraged as to Ashland’s future prosperity.

The children of Mr. Beaser, three in number, are all living: Margaret Elizabeth, wife of James A. Croser of Menominee, Michigan; Percy McLeod, now of Ashland; and Harry Hamlin, also of Ashland, residing with his mother, now Mrs. Wilson, an intelligent and very estimable lady.

1 See ‘History of Northern Wisconsin,’ p. 67.

2 The date of the platting of Ashland by Brunschweiler is taken from the original plat in the possession of the recorder of Ashland county, Wisconsin.

Samuel Stuart Vaughn

August 8, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

November 1888

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume IX, No. 1, pages 17-21.

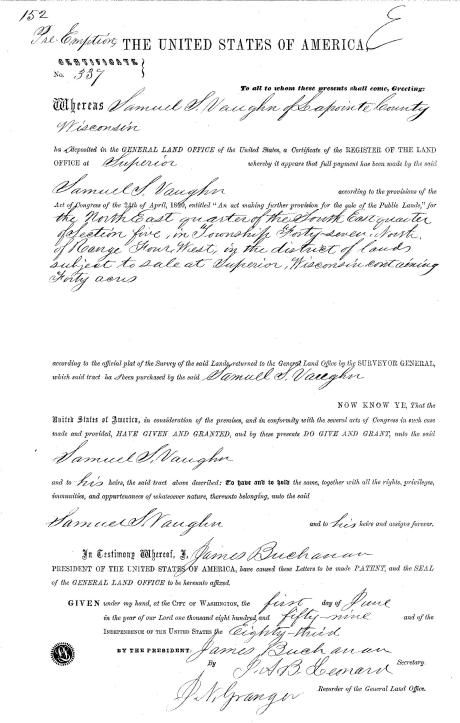

Samuel Stuart Vaughn.

Of the pioneers upon the southern shores of Lake Superior, none stand higher in the memory of those now living there than Samuel Stuart Vaughn. He was born at Berea, Cuyahoga county, Ohio, on the second of September, 1830. His parents were Ephraim Vaughn and Eunice Stewart Vaughn. Samuel was the youngest in a family of five children – two daughters and three sons. Although at a very early age possessed of a great desire for an education, he was, to a large extent, denied the advantages of schools, owing to the fact that his father was in straitened circumstances financially. It is related of the boy Samuel that he picked up chestnuts at one time, and took them into Cleveland, where he disposed of them to purchase a geography [book?] he wanted. Three months was the whole extent of his time passed in the common schools of his native place – surely a brief period, and one sorely regretted for its brevity by a boy who, even then, hungered and thirsted for knowledge.

~ FindAGrave.com

In 1849 the young man came to Eagle River, Michigan, where he engaged himself to his brother as clerk. He remained there until 1852, when the brothers removed to La Pointe, Wisconsin, reaching that place on the fourth of August. He now opened a store, and engaged in trading with the Indians and fishermen of the island and surrounding country. La Pointe was then the county seat of a county of the same name in Wisconsin, and a place of considerable importance, though its glory has since departed.

Vaughn advertisement from the August 22nd, 1857, issue of the Bayfield Mercury newspaper.

~ NewspaperArchive.com

Young Vaughn spoke the French and Chippewa languages fluently. This accomplishment was absolutely necessary, in the early days of this region of country to make a man successful as a trader. He was very fond of reading, particularly works of history, and through all his pioneer life his books were his loved companions. His taste was not for worthless books, but for those of an improving character; hence he received a large amount of benefit from his silent teachers.

In his relation with the Indians, which, owing to the nature of his business, were quite intimate, Mr. Vaughn commanded their fullest confidence. It is related that when at one time there were rumors of trouble between the white people and the Chippewas, and many of the settlers became frightened and feared they would be murdered by the natives, a delegation of chiefs came to him and said they wanted to have a talk. They said they had heard of the fears of the whites, but assured him there was nothing to be afraid of; the Indians would do no harm, “for,” said they, “we know that the soldiers of the white man are like the sands of the sea in numbers, and if we make any trouble they will come and overpower us.” Mr. Vaughn was abundantly satisfied of their sincerity as well as of their peaceful disposition, and he soon quieted the fears of the settlers.

“Being impressed,” says a writer who knew him well,

“with the future possibilities of this country and ambitious, to use a favorite expression of his own, to become ‘a man among men,’ he recognized the disadvantage under which he labored from the limited educational advantages he had enjoyed in his youth, and his first earnings were devoted to remedying his deficiency in this respect. Closing his business at La Pointe, he returned to his native state, where a year was spent in preparatory studies, which were pursued with a full realization of their importance to his future career. He spent several months in Cleveland acquiring a ‘business education.’ He became a systematic bookkeeper, careful in his transactions and persevering in his plans. Having devoted as much time to the special course of instruction marked out by him as his limited means would afford, he returned to La Pointe, at that time the only white settlement in all this region, where he remained until 1856.” 1

Mr. Vaughn, during the year just named, removed to Bayfield, the town site having been previously surveyed and platted. It was opposite La Pointe on the mainland, and is now the county-seat of Bayfield county, Wisconsin. There he erected the first stone building,2 built also a saw-mill, and engaged in the sale of general merchandise and in the manufacture of lumber. “In his characteristic manner,” says the writer just quoted,

“of doing with all his might whatever his hands found to do, he at once took a leading position in all matters of private and public interest which go to the building up of a prosperous community.”

Mr. Vaughn built what is known as Vaughn’s dock in Bayfield, and remained in that town until 1872. Meanwhile, he was married in Solon, Ohio, to Emeline Eliza Patrick. This event took place on the twenty-second of December, 1864. After spending a few months among friends in Ohio, he brought his wife west to share his frontier life. The wedding journey was made in February, 1865, the two going first to St. Paul; thence they journeyed to Bayfield by sleigh, “partly over logging roads, and partly over no road.” It was a novel experience to the bride, but one which she had no desire to shrink from. She was not the wife to be made unhappy by ordinary difficulties.

As early as the twenty-fifth of October, 1856, Mr. Vaughn had preëmpted one hundred and sixty acres of land, afterwards known as “Vaughn’s division of Ashland.” He was one of the leading spirits in the projection of the old St. Croix & Lake Superior railroad, and contributed liberally of his time and money in making the preliminary organizations and surveys. Being convinced, from the natural location of Ashland, that it would become in the future a place of importance, was the reason which induced him to preëmpt the land there, of which mention has just been made.

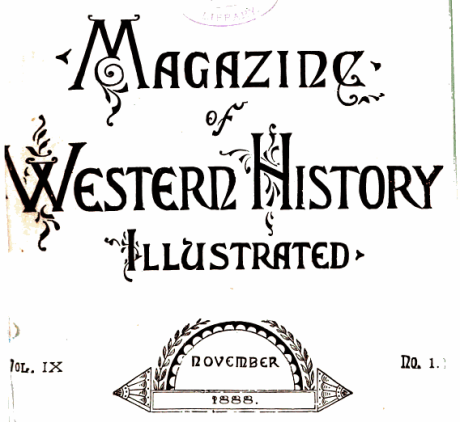

Vaughn was issued his patent to 40 acres in Ashland on June 1st, 1859. The other 120 acres of his preemption are not accounted for in these records.

~ General Land Office Records

As may be presumed, Mr. Vaughn omitted no opportunity of calling the attention of capitalists to the necessity of railroad facilities for northern Wisconsin. He became identified with the early enterprises organized for the purpose of building a trunk line from the southern and central portions of the state to Lake Superior, and was for many years a director in the old “Winnebago & Lake Superior” and “Portage & Lake Superior” Railroad companies, which, after many trials and tribulations, were consolidated, resulting in the building of the pioneer road – the Wisconsin Central.

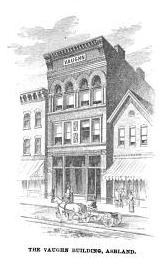

In 1871, upon the completion of the survey of the Wisconsin Central railroad, he proceeded to lay out his portion of the town of Ashland, and made arrangements for the transfer of his business thither from Bayfield. During the next year he made extensive improvements to his new home; these included the building of a residence, the erection of a store, also (in company with Mr. Charles Fisher) of a commercial dock. The Wisconsin Central railroad had begun work at the bay (Chaquamegon); and, at this time, many settlers were coming in. In the fall he moved into his new house, becoming, with his wife, a permanent resident of Ashland.

Mr. Vaughn and his partner just named received at their dock large quantities of merchandise by lake, and they took heavy contracts to furnish supplies to the railroad before mentioned. In the fall of 1872 they established branch stores at Silver creek and White river to furnish railroad men with supplies. They also had contracts to get out all the ties used by the railroad between Ashland and Penokee. In 1875 the firm was dissolved, and Mr. Vaughn continued in business until 1881, when he sold out, but continued to handle coal and other merchandise at his dock. In the winter previous he put in 10,000,000 feet of logs.

Mr. Vaughn represented the counties of Ashland, Barren, Bayfield, Burnett, Douglas and Polk in the thirty-fourth regular session of the Wisconsin legislature, being a member of the assembly for the year 1871. These counties, according to the Federal census of the year previous, contained a population of 6,365. His majority in the district over Issac I. Moore, Democrat, was 398. Mr. Vaughn was in politics a Republican. Previous to this time he had been postmaster for four years at Bayfield. He was several times called to the charge of town and county affairs as chairman of the board of supervisors, and in every station was faithful, as well as equal, to his trust; but he was never ambitious for political honors. He died at his home in Ashland of pneumonia, on the twenty-ninth day of January, 1886.

Mr. Vaughn was one of the most prominent men in northern Wisconsin, and one of the wealthiest citizens of Ashland at the time of his decease. He had accumulated a large amount of real estate in Ashland and Bayfield, and held heavy iron interests in the Gogebic district; but, at the same time, he was a man of charitable nature, being a member of several charitable orders and societies. He was a member of Ashland Lodge, I.O.O.F., and one of its foremost promoters and supporters. Mr. Vaughn was also a Mason, being a member of Wisconsin Consistory, Chippewa Commandery, K.T., Ashland Chapter, R.A.M., and Ancient Landmark Lodge, F. and A.M.

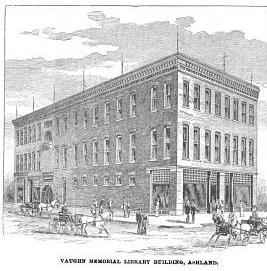

Although an unostentatious man, Mr. Vaughn was possessed of much public spirit, and the remark had been common in Ashland since his death, by those who knew him best, that the city had lost its best man. Certain it is that he was possessed of great enterprise, and was always ready with his means to help forward any scheme that he saw would benefit the community in which he lived. It had long been one of his settled determinations to appropriate part of his wealth to the establishment of a free library in Ashland. So it was that before his death the site had been chosen by him for the building, and a plan of the institution formulated in his mind, intending soon to make a reality of his day-dreams concerning this undertaking; but death cut short his plans.

It is needless to say to those who know to whom was confided the whole subject of the “Vaughn Library,” that it has not been allowed to die out. In his will Mr. Vaughn left hall his property to his wife, and she nobly came forward to make his known desires with regard to the institution a fixed fact. The corner-stone of the building for the library was laid, with imposing ceremonies, on the fourteenth of July, 1887, and a large number of books will soon be purchased to fill the shelves now nearly ready for them. It will be, in the broadest sense, a public library – free to all; and will surely become a lasting and proud monument to its generous founder, Samuel Stewart Vaughn. She who was left to carry out the noble schemes planned by the subject of this sketch, now the wife of the Rev. Angus Mackinnon, deserves particular mention in this connection. She is a lady of marked characteristics, all of which go to her praise. Soon after reaching her home in the west she taught some of the Bayfield Indians to read and write; and from that time to the present, has proved herself in many ways of sterling worth to northern Wisconsin.

“Years ago, when Ashland consisted of a few log houses and a half dozen stores – before there was even a rail through the woods that lead to civilization many miles away – this lady was a member of ‘Literary,’ organized by a half-dozen progressive young people; and in a paper which she then read on ‘The Future of Ashland,’ she predicted nearly everything about the growth of the place that has taken place during the past few years – the development of the iron mines, railroads, iron furnaces, water-works, paved streets, and, to a dot, the present limits of its thoroughfares. She is a representative Ashland lady.”

1 Samuel S. Fifield in the Ashland Press of February 6, 1886.

2 This was the second house in the place.

Another biographical sketch and this portrait of Samuel Stuart Vaughn are available on pages 80-81 of Commemorative Biographical Record of the Upper Lake Region by J.H. Beers & Co., 1905.

Historic Sites on Chequamegon Bay

July 25, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Historical Sites on Chequamegon Bay was originally published in Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: Volume XIII, by Reuben Gold Thwaites, 1895, pages 426-440.

HISTORIC SITES ON CHEQUAMEGON BAY.1

—

BY CHRYSOSTOM VERWYST, O.S.F.

Reverend Chrysostome Verwyst, circa 1918.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

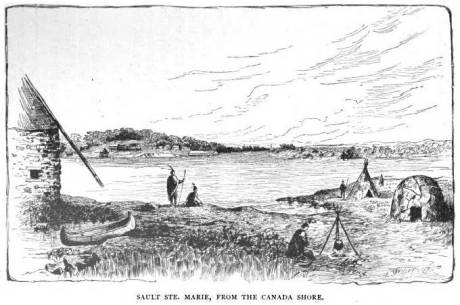

One of the earliest spots in the Northwest trodden by the feet of white men was the shore of Chequamegon Bay. Chequamegon is a corrupt form of Jagawamikong;2 or, as it was written by Father Allouez in the Jesuit Relation for 1667, Chagaouamigong. The Chippewas on Lake Superior have always applied this name exclusively to Chequamegon Point, the long point of land at the entrance of Ashland Bay. It is now commonly called by whites, Long Island; of late years, the prevailing northeast winds have caused Lake Superior to make a break through this long, narrow peninsula, at its junction with the mainland, or south shore, so that it is in reality an island. On the northwestern extremity of this attenuated strip of land, stands the government light-house, marking the entrance of the bay.

William Whipple Warren, circa 1851.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

W. W. Warren, in his History of the Ojibway Nation3, relates an Indian legend to explain the origin of this name. Menabosho, the great Algonkin demi-god, who made this earth anew after the deluge, was once hunting for the great beaver in Lake Superior, which was then but a large beaver-pond. In order to escape his powerful enemy, the great beaver took refuge in Ashland Bay. To capture him, Menabosho built a large dam extending from the south shore of Lake Superior across to Madelaine (or La Pointe) Island. In doing so, he took up the mud from the bottom of the bay and occasionally would throw a fist-full into the lake, each handful forming an island, – hence the origin of the Apostle Islands. Thus did the ancient Indians, the “Gété-anishinabeg,” explain the origin of Chequamegon Point and the islands in the vicinity. His dam completed, Menabosho started in pursuit of the patriarch of all the beavers ; he thinks he has him cornered. But, alas, poor Menabosho is doomed to disappointment. The beaver breaks through the soft dam and escapes into Lake Superior. Thence the word chagaouamig, or shagawamik (“soft beaver-dam”), – in the locative case, shagawamikong (“at the soft beaver-dam”).

Reverend Edward Jacker

~ FindAGrave.com

Rev. Edward Jacker, a well-known Indian scholar, now deceased, suggests the following explanation of Chequamegon: The point in question was probably first named Jagawamika (pr. shagawamika), meaning “there are long, far-extending breakers;” the participle of this verb is jaiagawamikag (“where there are long breakers”). But later, the legend of the beaver hunt being applied to the spot, the people imagined the word amik (a beaver) to be a constituent part of the compound, and changed the ending in accordance with the rules of their language, – dropping the final a in jagawamika, making it jagawamik, – and used the locative case, ong (jagawamikong), instead of the participial form, ag (jaiagawamikag).4

The Jesuit Relations apply the Indian name to both the bay and the projection of land between Ashland Bay and Lake Superior. our Indians, however, apply it exclusively to this point at the entrance of Ashland Bay. It was formerly nearly connected with Madelaine (La Pointe) Island, so that old Indians claim a man might in early days shoot with a bow across the intervening channel. At present, the opening is about two miles wide. The shores of Chequamegon Bay have from time immemorial been the dwelling-place of numerous Indian tribes. The fishery was excellent in the bay and along the adjacent islands. The bay was convenient to some of the best hunting grounds of Northern Wisconsin and Minnesota. The present writer was informed, a few years ago, that in Douglas county alone 2,500 deer had been killed during one short hunting season.5 How abundant must have been the chase in olden times, before the white had introduced to this wilderness his far-reaching fire-arms! Along the shores of our bay were established at an early day fur-trading posts, where adventurous Frenchmen carried on a lucrative trade with their red brethren of the forest, being protected by French garrisons quartered in the French fort on Madelaine Island.

From Rev. Henry Blatchford, an octogenarian, and John B. Denomie (Denominé), an intelligent half-breed Indian of Odanah, near Ashland, the writer has obtained considerable information as to the location of ancient and modern aboriginal villages on the shores of Chequamegon Bay. Following are the Chippewa names of the rivers and creeks emptying into the bay, where there used formerly to be Indian villages:

Charles Whittlesey documented several pictographs along the Bad River.

Mashki-Sibi (Swamp River, misnamed Bad River): Up this river are pictured rocks, now mostly covered with earth, on which in former times Indians engraved in the soft stone the images of their dreams, or the likenesses of their tutelary manitous. Along this river are many maple-groves, where from time immemorial they have made maple-sugar.

Makodassonagani-Sibi (Bear-trap River), which emptties into the Kakagon. The latter seems in olden times to have been the regular channel of Bad River, when the Bad emptied into Ashland Bay, instead of Lake Superior, as it now does. Near the mouth of the Kakagon are large wild-rice fields, where the Chippewas annually gather, as no doubt did their ancestors, great quantities of wild rice (Manomin). By the way, wild rice is very palatable, and the writer and his dusky spiritual children prefer it to the rice of commerce, although it does not look quite so nice.

Bishigokwe-Sibiwishen is a small creek, about six miles or so east of Ashland. Bishigokwe means a woman who has been abandoned by her husband. In olden times, a French trader resided at the mouth of this creek. He suddenly disappeared, – whether murdered or not, is not known. His wife continued to reside for many years at their old home, hence the name.

Nedobikag-Sibiwishen is the Indian name for Bay City Creek, within the limits of Ashland. Here Tagwagané, a celebrated Indian chief of the Crane totem, used occasionally to reside. Warren6 gives us a speech of his, at the treaty of La Pointe in 1842. This Tagwagané had a copper plate, an heirloom handed down in his family from generation to generation, on which were rude indentations and hieroglyphics denoting the number of generations of that family which had passed away since they first pitched their lodges at Shagawamikong and took possession of the adjacent country, including Madelaine Island. From this original mode of reckoning time, Warren concludes that the ancestors of said family first came to La Pointe circa A. D. 1490.

Detail of “Ici était une bourgade considerable” from Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin, 1744.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Metabikitigweiag-Sibiwishen is the creek between Ashland and Ashland Junction, which runs into Fish Creek a short distance west of Ashland. At the junction of these two creeks and along their banks, especially on the east bank of Fish Creek, was once a large and populous Indian village of Ottawas, who there raised Indian corn. It is pointed out on N. Bellin’s map (1744)7, with the remark, Ici était une bourgade considerable (“here was once a considerable village”). We shall hereafter have occasion to speak of this place. The soil along Fish Creek is rich, formed by the annual overflowage of its water, leaving behind a deposit of rich, sand loam. There a young growth of timber along the right bank between the bay and Ashland Junction, and the grass growing underneath the trees shows that it was once a cultivated clearing. It was from this place that the trail left the bay, leading to the Chippewa River country. Fish Creek is called by the Indians Wikwedo-Sibiwishen, which means “Bay Creek,” from wikwed, Chippewa for bay; hence the name Wikwedong, the name they gave to Ashland, meaning “at the bay.”

Whittlesey Creek (National Wildlife Refuge) was named after Asaph Whittlesey, brother of Charles Whittlesey. Photo of Asaph, circa 1860.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

According to Blatchford, there was formerly another considerable village at the mouth of Whittlesey’s Creek, called by the Indians Agami-Wikwedo-Sibiwishen, which signifies “a creek on the other side of the bay,” from agaming (on the other side of a river, or lake), wikwed (a bay), and sibiwishen (a creek). I think that Fathers Allouez and Marquette had their ordinary abode at or near this place, although Allouez seems also to have resided for some time at the Ottawa village up Fish Creek.

A short distance from Whittlesey’s Creek, at the western bend of the bay, where is now Shore’s Landing, there used to be a large Indian village and trading-post, kept by a Frenchman. Being at the head of the bay, it was the starting point of the Indian trail to the St. Croix country. Some years ago the writer dug up there, an Indian mound. The young growth of timber at the bend of the bay, and the absence of stumps, indicate that it had once been cleared. At the foot of the bluff or bank, is a beautiful spring of fresh water. As the St. Croix country was one of the principal hunting grounds of the Chippewas and Sioux, it is natural there should always be many living at the terminus of the trail, where it struck the bay.

From this place northward, there were Indian hamlets strung along the western shore of the bay. Father Allouez mentions visiting various hamlets two, three, or more (French) leagues away from his chapel. Marquette mentions five clearings, where Indian villages were located. At Wyman’s place, the writer some years ago dug up two Indian mounds, one of which was located on the very bank of the bay and was covered with a large number of boulders, taken from the bed of the bay. In this mound were found a piece of milled copper, some old-fashioned hand-made iron nails, the stem of a clay pipe, etc. The objects were no doubt relics of white men, although Indians had built the mound itself, which seemed like a fire-place shoveled under, and covered with large boulders to prevent it from being desecrated.

Boyd’s Creek is called in Chippewa, Namebinikanensi-Sibiwishen, meaning “Little Sucker Creek.” A man named Boyd once resided there, married to an Indian woman. He was shot in a quarrel with another man. One of his sons resides at Spider Lake, and another at Flambeau Farm, while two of his grand-daughters live at Lac du Flambeau.

Further north is Kitchi-Namebinikani-Sibiwishen, meaning “Large Sucker Creek,” but whites now call it Bonos Creek. These two creeks are not far apart, and once there was a village of Indians there. It was noted as a place for fishing at a certain season of the year, probably in spring, when suckers and other fish would go up these creeks to spawn.

At Vanderventer’s Creek, near Washburn, was the celebrated Gigito-Mikana, or “council-trail,” so called because here the Chippewas once held a celebrated council; hence the Indian name Gigito-Mikana-Sibiwishen, meaning “Council-trail Creek.” At the mouth of this creek, there was once a large Indian village.

There used also to be a considerable village between Pike’s Bay and Bayfield. It was probably there that the celebrated war chief, Waboujig, resided.

John Baptiste Denomie

~ Noble Lives of a Noble Race, A Series of Reproductions by the Pupils of Saint Mary’s, Odanah, Wisconsin, page 213-217.

There was once an Indian village where Bayfield now stands, also at Wikweiag (Buffalo Bay), at Passabikang, Red Cliff, and on Madelaine Island. The writer was informed by John B. Denomie, who was born on the island in 1834, that towards Chabomnicon Bay (meaning “Gooseberry Bay”) could long ago be seen small mounds or corn-hills, now overgrown with large trees, indications of early Indian agriculture. There must have been a village there in olden times. Another ancient village was located on the southwestern extremity of Madelaine Island, facing Chequamegon Point, where some of their graves may still be seen. It is also highly probable that there were Indian hamlets scattered along the shore between Bayfield and Red Cliff, the most northern mainland of Wisconsin. There is now a large, flourishing Indian settlement there, forming the Red Cliff Chippewa reservation. There is a combination church and school there at present, under the charge of the Franciscan Order. Many Indians also used to live on Chequamegon Point, during a great part of the year, as the fishing was good there, and blueberries were abundant in their season. No doubt from time immemorial Indians were wont to gather wild rice at the mouth of the Kakagon, and to make maple sugar up Bad River.

Illustration from The Story of Chequamegon Bay, Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: Volume XIII, 1895, page 419.

We thus see that the Jesuit Relations are correct when they speak of many large and small Indian villages (Fr. bourgades) along the shores of Chequamegon Bay. Father Allouez mentions two large Indian villages at the head of the bay – the one an Ottawa village, on Fish Creek; the other a Huron, probably between Shore’s Landing and Washburn. Besides, he mentions smaller hamlets visited by him on his sick-calls. Marquette says that the Indians lived there in five clearings, or villages. From all this we see that the bay was from most ancient times the seat of a large aboriginal population. Its geographical position towards the western end of the great lake, its rich fisheries and hunting grounds, all tended to make it the home of thousands of Indians. Hence it is much spoken of by Perrot, in his Mémoire, and by most writers on the Northwest of the last century. Chequamegon Bay, Ontonagon, Keweenaw Bay, and Sault Ste. Marie (Baweting) were the principal resorts of the Chippewa Indians and their allies, on the south shore of Lake Superior.

“Front view of the Radisson cabin, the first house built by a white man in Wisconsin. It was built between 1650 and 1660 on Chequamegon Bay, in the vicinity of Ashland. This drawing is not necessarily historically accurate.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The first white men on the shores of Chequamegon Bay were in all probability Groseilliers and Radisson. They built a fort on Houghton Point, and another at the head of the bay, somewhere between Whittlesey’s Creek and Shore’s Landing, as in some later paper I hope to show from Radisson’s narrative.8 As to the place where he shot the bustards, a creek which led him to a meadow9, I think this was Fish Creek, at the mouth of which is a large meadow, or swamp.10

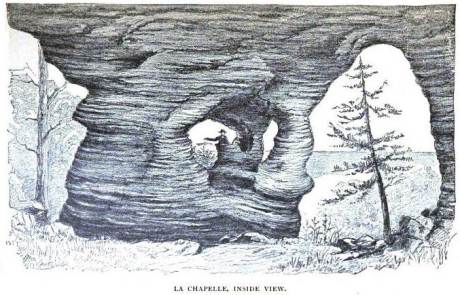

After spending six weeks in the Sioux country, our explorers retraced their steps to Chequamegon Bay, arriving there towards the end of winter. They built a fort on Houghton Point. The Ottawas had built another fort somewhere on Chequamegon Point. In travelling towards this Ottawa fort, on the half-rotten ice, Radisson gave out and was very sick for eight days; but by rubbing his legs with hot bear’s oil, and keeping them well bandaged, he finally recovered. After his convalescence, our explorers traveled northward, finally reaching James Bay.

The next white men to visit our bay were two Frenchmen, of whom W. W. Warren says:11

“One clear morning in the early part of winter, soon after the islands which are clustered in this portion of Lake Superior, and known as the Apostles, had been locked in ice, a party of young men of the Ojibways started out from their village in the Bay of Shag-a-waum-ik-ong [Chequamegon], to go, as was customary, and spear fish through holes in the ice, between the island of La Pointe and the main shore, this being considered as the best ground for this mode of fishing. While engaged in this sport, they discovered a smoke arising from a point of the adjacent island, toward its eastern extremity.

“The island of La Pointe was then totally unfrequented, from superstitious fears which had but a short time previous led to its total evacuation by the tribe, and it was considered an act of the greatest hardihood for any one to set foot on its shores. The young men returned home at evening and reported the smoke which they had seen arising from the island, and various were the conjectures of the old people respecting the persons who would dare to build a fire on the spirit-haunted isle. They must be strangers, and the young men were directed, should they again see the smoke, to go and find out who made it.

“Early the next morning, again proceeding to their fishing-ground, the young men once more noticed the smoke arising from the eastern end of the unfrequented island, and, again led on by curiosity, they ran thither and found a small log cabin, in which they discovered two white men in the last stages of starvation. The young Ojibways, filled with compassion, carefully conveyed them to their village, where being nourished with great kindness, their lives were preserved.

“These two white men had started from Quebec during the summer with a supply of goods, to go and find the Ojibways who every year had brought rich packs of beaver to the sea-coast, notwithstanding that their road was barred by numerous parties of the watchful and jealous Iroquois. Coasting slowly up the southern shores of the Great Lake late in the fall, they had been driven by the ice on to the unfrequented island, and not discovering the vicinity of the Indian village, they had been for some time enduring the pangs of hunger. At the time they were found by the young Indians, they had been reduced to the extremity of roasting and eating their woolen cloth and blankets as the last means of sustaining life.

“Having come provided with goods they remained in the village during the winter, exchanging their commodities for beaver skins. They ensuing spring a large number of the Ojibways accompanied them on their return home.

“From close inquiry, and judging from events which are said to have occurred about this period of time, I am disposed to believe that this first visit by the whites took place about two hundred years ago [Warren wrote in 1852]. It is, at any rate, certain that it happened a few years prior to the visit of the ‘Black-gowns’ [Jesuits] mentioned in Bancroft’s History, and it is one hundred and eighty-four years since this well-authenticated occurrence.”

So far Warren; he is, however, mistaken as to the date of the first black-gown’s visit, which was not 1668 but 1665.

Portrayal of Claude Allouez

~ National Park Service

The next visitors to Chequamegon Bay were Père Claude Allouez and his six companions in 1665. We come now to a most interesting chapter in the history of our bay, the first formal preaching of the Christian religion on its shores. For a full account of Father Allouez’s labors here, the reader is referred to the writer’s Missionary Labors of Fathers Marquette, Allouez, and Ménard in the Lake Superior Region. Here will be given merely a succinct account of their work on the shores of the bay. To the writer it has always been a soul-inspiring thought that he is allowed to tread in the footsteps of those saintly men, who walked, over two hundred years ago, the same ground on which he now travels; and to labor among the same race for which they, in starvation and hardship, suffered so much.

In the Jesuit Relation for 1667, Father Allouez thus begins the account of his five years’ labors on the shores of our bay:

“On the eight of August of the year 1665, I embarked at Three Rivers with six Frenchmen, in company with more than four hundred Indians of different tribes, who were returning to their country, having concluded the little traffic for which they had come.”

Marquis Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy

~ Wikipedia.org

His voyage into the Northwest was one of the great hardships and privations. The Indians willingly took along his French lay companions, but him they disliked. Although M. Tracy, the governor of Quebec, had made Father Allouez his ambassador to the Upper Algonquins, thus to facilitate his reception in their country, nevertheless they opposed him accompanying them, and threatened to abandon him on some desolate island. No doubt the medicine-men were the principal instigators of this opposition. He was usually obliged to paddle like the rest, often till late in the night, and that frequently without anything to eat all day.

“On a certain morning,” he says, “a deer was found, dead since four or five days. It was a lucky acquisition for poor famished beings. I was offered some, and although the bad smell hindered some from eating it, hunger made me take my share. But I had in consequence an offensive odor in my mouth until the next day. In addition to all these miseries we met with, at the rapids I used to carry packs as large as possible for my strength; but I often succumbed, and this gave our Indians occasion to laugh at me. They used to make fun of me, saying a child ought to be called to carry me and my baggage.”

August 24, they arrived at Lake Huron, where they made a short stay; then coasting along the shores of that lake, they arrived at Sault Ste. Marie towards the beginning of September. September 2, they entered Lake Superior, which the Father named Lake Tracy in acknowledgement of the obligations which the people of those upper countries owed to the governor. Speaking of his voyage on Lake Superior, Father Allouez remarks:

“Having entered Lake Tracy, we were engaged the whole month of September in coasting along the south shore. I had the consolation of saying holy mass, as I now found myself alone with our Frenchmen, which I had not been able to do since my departure from Three Rivers. * * * We afterwards passed the bay, called by the aged, venerable Father Ménard, Sait Theresa [Keweenaw] Bay.”

Speaking of his arrival at Chequamegon Bay, he says:

“After having traveled a hundred and eighty leagues on the south shore of Lake Tracy, during which our Saviour often deigned to try our patience by storms, hunger, daily and nightly fatigues, we finally, on the first day of October, 1665, arrived at Chagaouamigong, for which place we had sighed so long. It is a beautiful bay, at the head of which is situated the large village of the Indians, who there cultivate fields of Indian corn and do not lead a nomadic life. There are at this place men bearing arms, who number about eight hundred; but these are gathered together from seven different tribes, and live in peacable community. This great number of people induced us to prefer this place to all others for our ordinary abode, in order to attend more conveniently to the instruction of these heathens, to put up a chapel there and commence the functions of Christianity.”

Further on, speaking of the site of his mission and its chapel, he remarks:

“The section of the lake shore, where we have settled down, is between two large villages, and is, as it were, the center of all the tribes of these countries, because the fishing here is very good, which is the principal source of support of these people.”

To locate still more precisely the exact site of his chapel, he remarks, speaking of the three Ottawa clans (Outaouacs, Kiskakoumacs, and Outaoua-Sinagonc):

“I join these tribes [that is, speaks of them as one tribe] because they had one and the same language, which is the Algonquin, and compose one of the same village, which is opposite that of the Tionnontatcheronons [Hurons of the Petun tribe] between which villages we reside.”

But where was that Ottawa village? A casual remark of Allouez, when speaking of the copper mines of Lake Superior, will help us locate it.

“It is true,” says he, “on the mainland, at the place where the Outaouacs raise Indian corn, about half a league from the edge of the water, the women have sometimes found pieces of copper scattered here and there, weighing ten, twenty or thirty pounds. It is when digging into the sand to conceal their corn that they make these discoveries.”

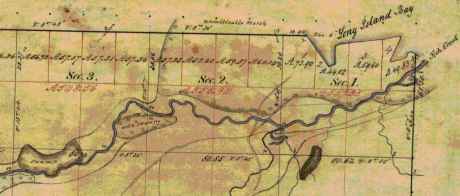

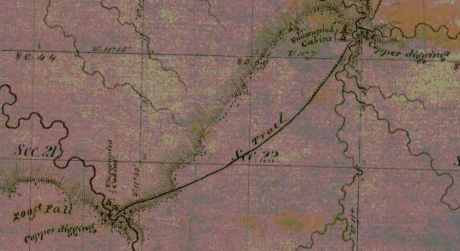

Detail of Fish Creek from Township 47 North Range 5 West.

~ Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records

Allouez evidently means Fish Creek. About a mile or so from the shore of the bay, going up this creek, can be seen traces of an ancient clearing on the left-hand side, where Metabikitigweiag Creeek empties into Fish Creek, about half-way between Ashland and Ashland Junction. The writer examined the locality about ten years ago. This then is the place where the Ottawas raised Indian corn and had their village. In Charlevoix’s History of New France, the same place is marked as the site of an ancient large village. The Ottawa village on Fish Creek appears to have been the larger of the two at the head of Chequamegon Bay, and it was there Allouez resided for a time, until he was obliged to return to his ordinary dwelling place, “three-fourths of a league distant.” This shows that the ordinary abode of Father Allouez and Marquette, the site of their chapel, was somewhere near Whittlesey’s Creek or Shore’s Landing. The Huron village was most probably along the western shore of the bay, between Shore’s Landing and Washburn.

Detail of Ashland next to an ancient large village (unmarked) in Township 47 North Range 4 West.

~ Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records

Father Allouez did not confine his apostolic labors to the two large village at the head of the bay. He traveled all over the neighborhood, visiting the various shore hamlets, and he also spent a month at the western extremity of Lake Superior – probably at Fond du Lac – where he met with some Chippewas and Sioux. In 1667 he crossed the lake, most probably from Sand Island, in a frail birch canoe, and visited some Nipissirinien Christians at Lake Nepigon (Allimibigong). The same year he went to Quebec with an Indian flotilla, and arrived there on the 3d of August, 1667. After only two days’ rest he returned with the same flotilla to his far distant mission on Chequamegon Bay, taking along Father Louis Nicholas. Allouez contained his missionary labors here until 1669, when he left to found St. Francis Xavier mission at the head of Green Bay. His successor at Chequamegon Bay was Father James Marquette, discoverer and explorer of the Mississippi. Marquette arrived here September 13, 1669, and labored until the spring of 1671, when he was obliged to leave on account of the war which had broken out the year before, between the Algonquin Indians at Chequamegon Bay and their western neighbors, the Sioux.

1 – See ante, p. 419 for map of the bay. – ED.

2 – In writing Indian names, I follow Baraga’s system of orthography, giving the French quality to both consonants and vowels.

3 – Minn. Hist. Colls., v. – ED.

4 – See ante, p. 399, note. – ED.

5 – See Carr’s interesting and exhaustive article, “The Food of Certain American Indians,” in Amer. Antiq. Proc., x., pp. 155 et seq. – ED.

6 – Minn. Hist. Colls., v. – ED.

7 – In Charlevoix’s Nouvelle France. – ED.

8 – See Radisson’s Journal, in Wis. Hist. Colls., xi. Radisson and Groseilliers reached Chequamegon Bay late in the autumn of 1661. – ED.

9 – Ibid., p. 73: “I went to the wood some 3 or 4 miles. I find a small brooke, where I walked by ye sid awhile, wch brought me into meddowes. There was a poole, where weare a good store of bustards.” – ED.

10 – Ex-Lieut. Gov. Sam. S. Fifield, of Ashland, writes me as follows:

“After re-reading Radisson’s voyage to Bay Chewamegon, I am satisfied that it would by his description be impossible to locate the exact spot of his camp. The stream in which he found the “pools,” and where he shot fowl, is no doubt Fish Creek, emptying into the bay at its western extremity. Radisson’s fort must have been near the head of the bay, on the west shore, probably at or near Boyd’s Creek, as there is an outcropping of rock in that vicinity, and the banks are somewhat higher than at the head of the bay, where the bottom lands are low and swampy, forming excellent “duck ground” even to this day. Fish Creek has three outlets into the bay, – one on the east shore or near the east side, one central, and one near the western shore; for full two miles up the stream, it is a vast swamp, through which the stream flows in deep, sluggish lagoons. Here, in the early days of American settlement, large brook trout were plenty; and even in my day many fine specimens have been taken from these “pools.” Originally, there was along these bottoms a heavy elm forest, mixed with cedar and black ash, but it has now mostly disappeared. An old “second growth,” along the east side, near Prentice Park, was evidently once the site of an Indian settlement, probably of the 18th century.

“I am of the opinion that the location of Allouez’s mission was at the mouth of Vanderventer’s Creek, on the west shore of the bay, near the present village of Washburn. It was undoubtedly once the site of a large Indian village, as was the western part of the present city of Ashland. When I came to this locality, nearly a quarter of a century ago, “second growth” spots could be seen in several places, where it was evident that the Indians had once had clearings for their homes. The march of civilization has obliterated these landmarks of the fur-trading days, when the old French voyageurs made the forest-clad shores of our beautiful bay echo with their boat songs, and when resting from their labors sparked the dusky maidens in their wigwams.”

Rev. E. P. Wheeler, of Ashland, a native of Madelaine Island, and an authority on the region, writes me:

“I think Radisson’s fort was at the mouth of Boyd’s Creek, – at least that place seems for the present to fulfill the conditions of his account. it is about three or four miles from here to Fish Creek valley, which leads, when followed down stream, to marshes ‘meadows, and a pool.’ No other stream seems to have the combination as described. Boyd’s Creek is about four miles from the route he probably took, which would be by way of the plateau back from the first level, near the lake. Radisson evidently followed Fish Creek down towards the lake, before reaching the marshes. This condition is met by the formation of the creek, as it is some distance from the plateau through which Fish Creek flows to its marshy expanse. Only one thing makes me hesitate about coming to a final decision, – that is, the question of the age of the lowlands and formations around Whittlesey Creek. I am going to go over the ground with an expert geologist, and will report later. Thus far, there seems to be no reason to doubt that Fish Creek is the one upon which Radisson hunted.” – ED.

11 – Minn. Hist. Colls., v., pp. 121, 122, gives the date as 1652. – ED.

!["In 1845 [Warren Lewis] was appointed Register of the United States Land Office at Dubuque. In 1853 he was appointed by President Pierce Surveyor-General for Iowa, Wisconsin and Minnesota and at the expiration of his term was reappointed by President Buchanan." ~ The Iowa Legislature](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/warner-lewis.jpg?w=196&h=300)

![Leonard Hemenway Wheeler ~ Unnamed Wisconsin by [????]](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/leonard-hemenway-wheeler-from-unnamed-wisconsin.jpg?w=237&h=300)