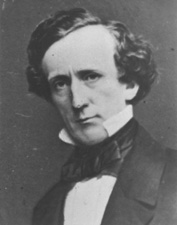

Colonel Charles Whittlesey

May 27, 2016

By Amorin Mello

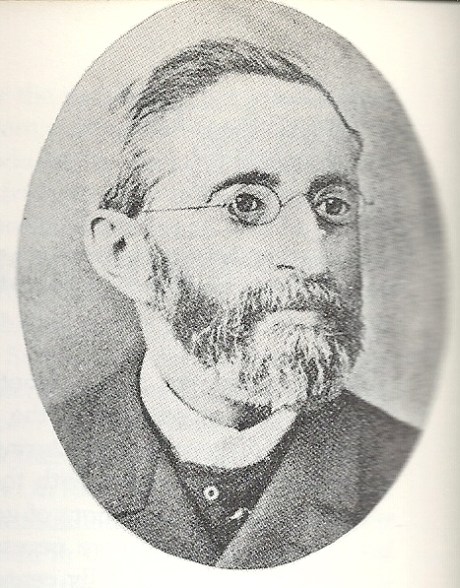

C.C. Baldwin was a friend, colleague, and biographer of Charles Whittlesey.

~ Memorial of Charles Candee Baldwin, LL. D.: Late President of the Western Reserve Historical Society, 1896, page iii.

This is a reproduction of Colonel Charles Whittlesey’s biography from the Magazine of Western History, Volume V, pages 534-548, as published by his successor Charles Candee Baldwin from the Western Reserve Historical Society. This biography provides extensive and intimate details about the life and profession of Whittlesey not available in other accounts about this legendary man.

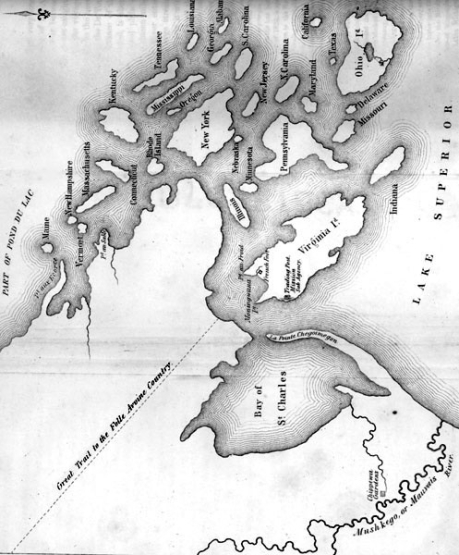

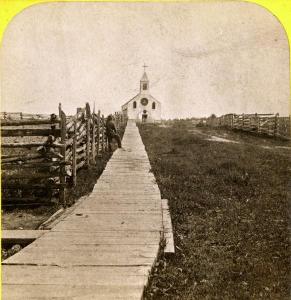

Whittlesey came to Lake Superior in 1845 while working for the Algonquin Mining Company along the Keweenaw Peninsula’s copper region. His first trip to Chequamegon Bay appears to have been in 1849 while doing do a geological survey of the Penokee Mountains for David Dale Owen. Whittlesey played a dramatic role in American settlement of the Chequamegon Bay region. Whittlesey convinced his brother, Asaph Whittlesey Jr., to move from the Western Reserve in 1854 establish what became the City of Ashland at the head of Chequamegon Bay as a future port town for extracting and shipping minerals from the Penokee Mountains. Whittlesey’s influence can still be witnessed to this day through local landmarks named in his honor:

Whittlesey published more than two hundred books, pamphlets, and articles. For additional research resources, the extensive Charles Whittlesey Papers are available through the Western Reserve Historical Society in two series:

Magazine of Western History, Volume V, pages 534-548.

COLONEL CHARLES WHITTLESEY.

Map of the Connecticut Western Reserve in Ohio by William Sumner, September 1826.

~ Cleveland Public Library

![Asaph Whittlesey [Sr], Late of Tallmadge, Summit Co., Ohio by Vesta Hart Whittlesey and Susan Everett Whittlesey, né Fitch, 1872.](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/asaph-whittlesey-vesta-hart.jpg?w=186&h=300)

[Father] Asaph Whittlesey [Sr], Late of Tallmadge, Summit Co., Ohio by [mother] Vesta Hart Whittlesey [posthumously] and [stepmother] Susan Everett Whittlesey, né Fitch, 1872.

~ Archive.org

War was then in the west, and his neighbors feared they might be the victims of the scalping knife. But the danger was different. In passing the Narrows, between Pittsburgh and Beaver, the wagon ran off a bank and turned completely over on the wife and children. They were rescued and revived, but the accident permanently impaired the health of Mr. Whittlesey.

Mr. Whittlesey was in Tallmadge, justice of the peace from soon after his arrival till near the close of his life, and postmaster from 1814, when the office was first established, to his death. He was again severely injured, but a strong constitution and unflinching will enabled him to accomplish much. He had a store, buying goods in Pittsburgh and bringing them in wagons to Tallmadge; and an ashery; and in 1818 he commenced the manufacture of iron on the Little Cuyahoga, below Middlebury.

The times were hard, tariff reduced, and in 1828 he returned to his farm prematurely old. He died in 1842. Says General Bierce,

“His intellect was naturally of a high order, his religious convictions were strong and never yielded to policy or expediency. He was plain in speech, sometimes abrupt. Those who respected him were more numerous than those who loved him. But for his friends, no one had a stronger attachment. His dislikes were not very well concealed or easily removed. In short, he was a man of strong mind, strong feelings, strong prejudices, strong affections and strong attachments, yet the whole was tempered with a strong sense of justice and strong religious feelings.”

[Uncle] Elisha Whittlesey

~ Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

Portrait of Reverend David Bacon from ConnecticutHistory.org:

“David Bacon (1771 – August 27, 1817) was an American missionary in Michigan Territory. He was born in Woodstock, Connecticut. He worked primarily with the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes, although they were not particularly receptive to his Christian teachings. He founded the town of Tallmadge, Ohio, which later became the center of the Congregationalist faith in Ohio.”

~ Wikipedia.org

Tallmadge was settled in 1808 as a religious colony of New England Congregationalists, by a colony led by Rev. David Bacon, a missionary to the Indians. This affected the society in which the boy lived, and exercised much influence on the morality of the town and the future of its children, one of whom was the Rev. Leonard Bacon. Rev. Timlow’s History of Southington says, “Mr. Whittlesey moved to Tallmadge, having become interested in settling a portion of Portage county with Christian families.” And that he was a man “of surpassing excellence of character.”

If it should seem that I have dwelt upon the parents of Colonel Whittlesey, it is because his own character and career were strongly affected by their characters and history. Charles, the son, combined the traits of the two. He commenced school at four years old in Southington; the next year he attended the log school house at Tallmadge until 1819, when the frame academy was finished and he attended it in winter, working on the farm in summer until he was nineteen.

The boy, too, saw early life on foot, horseback and with ox-teams. He found the Indians still on the Reserve, and in person witnessed the change from savage life and new settlements, to a state of three millions of people, and a large city around him. One of Colonel Whittlesey’s happiest speeches is a sketch of log cabin times in Tallmadge, delivered at the semi-centennial there in 1857.

~ Annual Report on the Geological Survey of the State of Ohio: 1837 by Ohio Geologist William Williams Mather, 1838, page 22.

In 1827 the youngster became a cadet at West Point. Here he displayed industry, and in some unusual incidents there, coolness and courage. He graduated in 1831, and became brevet second lieutenant in the Fifth United States infantry, and in November started to join his regiment at Mackinaw. He did duty through the winter with the garrison at Fort Gratiot. In the spring he was assigned at Green Bay to the company of Captain Martin Scott, so famous as a shot. At the close of the Black Hawk War he resigned from the army. Though recognizing the claim of the country to the services of the graduates of West Point, he tendered his services to the government during the Seminole Mexican war. By a varied experience his life thereafter was given to wide and general uses. He at first opened a law office in Cleveland, Ohio, and was fully occupied in his profession, and as part owner and co-editor of the Whig and Herald until the year 1837. He was that year appointed assistant geologist of the state of Ohio. Through very uneconomical economy, the survey was discontinued at the end of two years, when the work was partly done and no final reports had been made. Of course most of the work and its results were lost. Great and permanent good indeed resulted to the material wealth of the state, in disclosing the rich coal and iron deposit of southeastern Ohio, thus laying the foundation for the vast manufacturing industries which have made that portion of the state populous and prosperous. The other gentlemen associated with him were Professor William Mather as principal; Dr. Kirtland was entrusted with natural history. Others were Dr. S. P. Hildreth, Dr. Caleb Briggs, Jr., Professor John Locke and Dr. J. W. Foster. It was an able corps, and the final results would have been very valuable and accurate. In 1884, Colonel Whittlesey was sole survivor and said in this Magazine:

“Fifty years since, geology had barely obtained a standing among the sciences even in Europe. In Ohio it was scarcely recognized. The state at that time was more of a wilderness than a cultivated country, and the survey was in progress little more than two years. It was unexpectedly brought to a close without a final report. No provision was made for the preservation of papers, field notes and maps.”

Report of Progress in 1869, by J. S. Newberry, Chief Geologist, by the Geological Survey of Ohio, 1870.

Professor Newbury, in a brief resume of the work of the first survey (report of 1869), says the benefits derived “conclusively demonstrate that the geological survey was a producer and not a consumer, that it added far more than it took from the public treasury and deserved special encouragement and support as a wealth producing agency in our darkest financial hour.” The publication of the first board, “did much,” says Professor Newberry, “to arrest useless expenditure of money in the search for coal outside of the coal fields and in other mining enterprises equally fallacious, by which, through ignorance of the teachings of geology, parties were constantly led to squander their means.” “It is scarcely less important to let our people know what we have not, than what we have, among our mineral resources.”

“Descriptions of Ancient Works in Ohio. By Charles Whittlesey, of the late Geological Corps of Ohio.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume III., Article 7, 1852.

The topographical and mathematical parts of the survey were committed to Colonel Whittlesey. He made partial reports, to be found in the ‘State Documents’ of 1838 and 1839, but his knowledge acquired in the survey was of vastly greater service in many subsequent writings, and, as a foundation for learning, made useful in many business enterprises of Ohio. He had, during this survey, examined and surveyed many ancient works in the state, and, at its close, Mr. Joseph Sullivant, a wealthy gentleman interested in archaeology, residing in Columbus, proposed that, he bearing the actual expense, Whittlesey should continue the survey of the works of the Mound Builders, with a view to joint publication. During the years 1839 and 1840, and under the arrangement, he made examination of nearly all the remaining works then discovered, but nothing was done toward their publication. Many of his plans and notes were used by Messrs. Squier & Davis, in 1845 and 1846, in their great work, which was the first volume of the Smithsonian Contributions, and in that work these gentlemen said:

“Among the most zealous investigators in the field of American antiquarian research is Charles Whittlesey, esq., of Cleveland, formerly topographical engineer of Ohio. His surveys and observations, carried on for many years and over a wide field, have been both numerous and accurate, and are among the most valuable in all respects of any hitherto made. Although Mr. Whittlesey, in conjunction with Joseph Sullivant, esq., of Columbus, originally contemplated a joint work, in which the results of his investigations should be embodied, he has, nevertheless, with a liberality which will be not less appreciated by the public than by the authors, contributed to this memoir about twenty plans of ancient works, which, with the accompanying explanations and general observations, will be found embodied in the following pages.

“It is to be hoped the public may be put in possession of the entire results of Mr. Whittlesey’s labor, which could not fail of adding greatly to our stock of knowledge on this interesting subject.”

“Marietta Works, Ohio. Charles Whittlesey, Surveyor 1837.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume I., Plate XXVI.

It will be seen that Mr. Whittlesey was now fairly started, interested and intelligent, in the several fields which he was to make his own. And his very numerous writings may be fairly divided into geology, archaeology, history, religion, with an occasional study of topographical geology. A part of Colonel Whittlesey’s surveys were published in 1850, as one of the Smithsonian contributions; portions of the plans and minutes were unfortunately lost. Fortunately the finest and largest works surveyed by him were published. Among those in the work of Squier & Davis, were the wonderful extensive works at Newark, and those at Marietta. No one again could see those works extending over areas of twelve and fifteen miles, as he did. Farmers cannot raise crops without plows, and the geography of the works at Newark must still be learned from the work of Colonel Whittlesey.

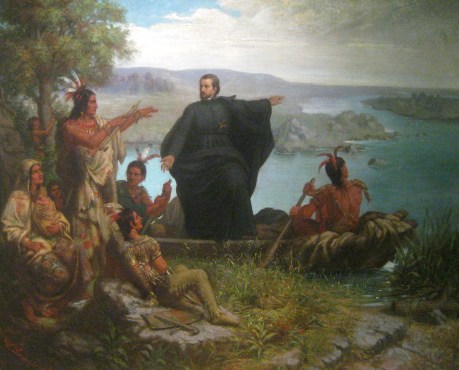

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume XIII., Article IV., page 2 of “Ancient Mining on the Shores of Lake Superior” by Charles Whittlesey.

He made an agricultural survey of Hamilton county in 1844. That year the copper mines of Michigan began to excite enthusiasm. The next year a company was organized in Detroit, of which Colonel Whittlesey was the geologist. In August they launched their boat above the rapids of the Sault St. Marie and coasted along the shore to where is now Marquette. Iron ore was beneath notice, and in truth was no then transportable, and they pulled away for Copper Harbor, and then to the region between Portage lake and Ontonagon, where the Algonquin and Douglas Houghton mines were opened. The party narrowly escaped drowning the night they landed. Dr. Houghton was drowned the same night not far from them. A very interesting and life-like account of their adventures was published by Colonel Whittlesey in the National Magazine of New York City, entitled “Two Months in the Copper Regions.” From 1847 to 1851 inclusive, he was employed by the United States in the survey of the country around Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi, in reference to mines and minerals. After that he spent much time in exploring and surveying the mineral district of the Lake Superior basin. The wild life of the woods with a guide and voyageurs threading the streams had great attractions for him and he spent in all fifteen seasons upon Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi, becoming thoroughly familiar with the topography and geological character of that part of the country.

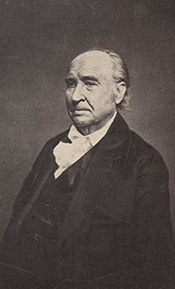

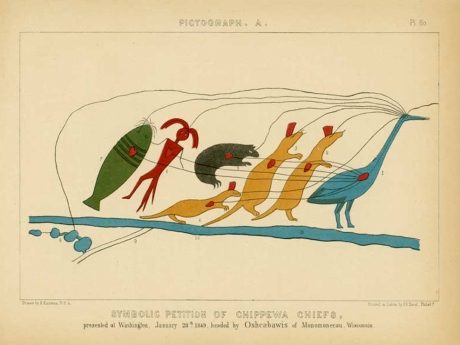

“Pictograph C. Okundekund [Okandikan] and his Band of Ontonagon – Michigan,” as reproduced from birch bark by Seth Eastman, and published as Plate 62 in Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, Volume I., by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, 1851. This was one of several pictograph petitions from the 1849 Martell delegation:

“By this scroll, the chief Kun-de-kund of the Eagle totem of the river Ontonagon, of Lake Superior, and certain individuals of his band, are represented as uniting in the object of their visit of Oshcabewis. He is depicted by the figure of an eagle, Number 1. The two small lines ascending from the head of the bird denote authority or power generally. The human arm extended from the breast of the bird, with the open hand, are symbolic of friendship. By the light lines connecting the eye of each person with the chief, and that of the chief with the President, (Number 8,) unity of views or purpose, the same as in pictography Number 1, is symbolized. Number 2, 3, 4, and 5, are warriors of his own totem and kindred. Their names, in their order, are On-gwai-sug, Was-sa-ge-zhig, or The Sky that lightens, Kwe-we-ziash-ish, or the Bad-boy, and Gitch-ee-man-tau-gum-ee, or the great sounding water. Number 6. Na-boab-ains, or Little Soup, is a warrior of his band of the Catfish totem. Figure Number 7, repeated, represents dwelling-houses, and this device is employed to deonte that the persons, beneath whose symbolic totem it is respectively drawn, are inclined to live in houses and become civilized, in other words, to abandon the chase. Number 8 depicts the President of the United States standing in his official residence at Washington. The open hand extended is employed as a symbol of friendship, corresponding exactly, in this respect, with the same feature in Number 1. The chief whose name is withheld at the left hand of the inferior figures of the scroll, is represented by the rays on his head, (Figure 9,) as, apparently, possessing a higher power than Number 1, but is still concurring, by the eye-line, with Kundekund in the purport of pictograph Number 1.”

“Studio portrait of geologist Charles Whittlesey dressed for a field trip.” Circa 1858.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

His detailed examination extended along the copper range from the extreme east of Point Keweenaw to Ontonagon, through the Porcupine mountain to the Montreal river, and thence to Long lake in Wisconsin, a distance of two hundred miles. In 1849, 1850 and 1858 he explored the valley of the Menominee river from its mouth to the Brule. He was the first geologist to explore the South range. The Wisconsin Geological Survey (Vol. 3 pp. 490 and 679) says this range was first observed by him, and that he many years ago drew attention to its promise of merchantable ores which are now extensively developed from the Wauceda to the Commonwealth mines, and for several miles beyond. He examined the north shore from Fond du Lac east, one hundred miles, the copper range of Minnesota and on the St. Louis river to the bounds of our country. His report was published by the state in 1865, and was stated by Professor Winchill to be the most valuable made.

All his geological work was thorough, and the development of the mineral resources which he examined, and upon which he reported, gave the best proofs of his scientific ability and judgment.

“Outline Map Showing the Position of the Ancient Mine Pits of Point Keweenaw, Michigan by Charles Whittlesey.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume XIII., Article IV., frontpiece of “Ancient Mining on the Shores of Lake Superior” by Charles Whittlesey, 1863.

With the important results from his labors in Ohio in mind, the state of Wisconsin secured his services upon the geological survey of that state, carried on in 1858, 1859 and 1860, and terminated only by the war. The Wisconsin survey was resumed by other parties, and the third volume of the Report for Northern Wisconsin, page 58, says:

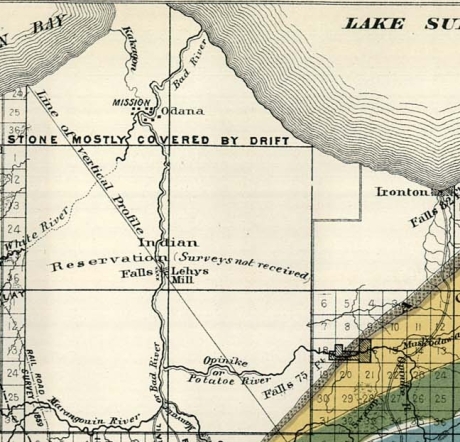

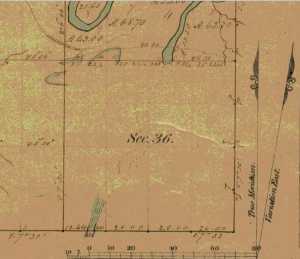

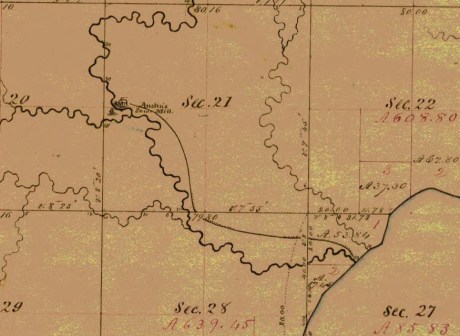

The Contract of James Hall with Charles Whittlesey is available from the Journal of the Assembly of Wisconsin, Volume I, pages 178-179, 1862. Whittlesey was to perform “a careful geological survey of the country lying between the Montreal river on the east, and the westerly branches of [the] Bad River on west”. This contract was unfulfilled due to the outbreak of the American Civil War. Whittlesey independently published his survey of the Penokee Mountains in 1865 without Hall. Some of Whittlesey”s pamphlets have been republished here on Chequamegon History in the Western Reserve category of posts.“The only geological examinations of this region, however, previous to those on which the report is based, and deserving the name, were those of Colonel Charles Whittlesey of Cleveland, Ohio. This gentleman was connected with Dr. D. D. Owen’s United States geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota, and in this connection examined the Bad River country, in 1848. The results are given in Dr. Owen’s final report, published in Washington, in 1852. In 1860 (August to October) Colonel Whittlesey engaged in another geological exploration in Ashland, Bayfield and Douglass counties, as part of the geological survey of Wisconsin, then organized under James Hall. His report, presented to Professor Hall in the ensuing year, was never published, on account of the stoppage of the survey. A suite of specimens, collected by Colonel Whittlesey during these explorations, is at present preserved in the cabinet of the state university at Madison, and it bears testimony to the laborious manner in which that gentleman prosecuted the work. Although the report was never published, he has issued a number of pamphlet publications, giving the main results obtained by him. A list of them, with full extracts from some of them, will be found in an appendix to the report. In the same appendix I have reproduced a geological map of this region, prepared by Colonel Whittlesey in 1860.”

“Geological Map of the Penokie Range.” by Charles Whittlesey, Dec. 1860.

~ Geology of Wisconsin. Survey of 1873-1879. Volume III., 1880, Plate XX, page 214.

~ Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, since its establishment in 1802 by George W. Cullum, page 496.

“The Baltimore Plot was an alleged conspiracy in late February 1861 to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln en route to his inauguration. Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, played a key role by managing Lincoln’s security throughout the journey. Though scholars debate whether or not the threat was real, clearly Lincoln and his advisors believed that there was a threat and took actions to ensure his safe passage through Baltimore, Maryland.”

~ Wikipedia.org

Such was Colonel Whittlesey’s employment when the first signs of the civil war appeared. He abandoned it at once. He became a member of one of the military companies that tendered its services to President-elect Lincoln, when he was first threatened, in February, 1861. He became quickly convinced that war was inevitable, and urged the state authorities that Ohio be put at once in preparation for it; and it was partly through his influence that Ohio was so very ready for the fray, in which, at first, the general government relied on the states. Two days after the proclamation of April 15, 1861, he joined the governor’s staff as assistant quartermaster-general. He served in the field in West Virginia with the three months’ men, as state military engineer; with the Ohio troops, under General McClellan, Cox and Hill. At Seary Run, on the Kanawha, July 17, 1861, he distinguished himself by intrepidity and coolness during a severe engagement, in which his horse was shot under him. At the expiration of the three months’ service, he was appointed colonel of the Twentieth regiment, Ohio volunteers, and detailed by General Mitchell as chief engineer of the department of Ohio, where he planned and constructed the defenses of Cincinnati.

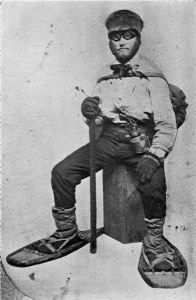

“[Brother] Asaph Whittlesey [Jr.] dressed for his journey from Ashland to Madison, Wisconsin, to take up his seat in the state legislature. Whittlesey is attired for the long trek in winter gear including goggles, a walking staff, and snowshoes.” Circa 1860.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

“SIR: Will you allow me to suggest the consideration of a great movement by land and water, up the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers.

“First, Would it not allow of water transportation half way to Nashville?

“Second, Would it not necessitate the evacuation of Columbus, by threatening their railway communications?

“Third, Would it not necessitate the retreat of General Buckner, by threatening his railway lines?

“Fourth, Is it not the most feasible route into Tennessee?”

This plan was adopted, and Colonel Whittlesey’s regiment took part in its execution.

In April, 1862, on the second day of the battle of Shiloh, Colonel Whittlesey commanded the Third brigade of General Wallace’s division — the Twentieth, Fifty-sixth, Seventy-sixth and Seventy-eighth Ohio regiments. “It was against the line of that brigade that General Beauregard attempted to throw the whole weight of his force for a last desperate charge; but he was driven back by the terrible fire, that his men were unable to face.” As to his conduct, Senator Sherman said in the United States senate.1

The official report of General Wallace leaves little to be said. The division commander says, “The firing was grand and terrible. Before us was the Crescent regiment of New Orleans; shelling us on our right was the Washington artillery of Manassas renown, whose last charge was made in front of Colonel Whittlesey’s command.”

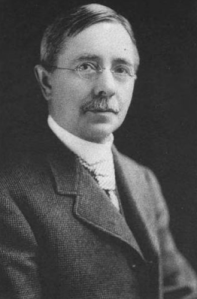

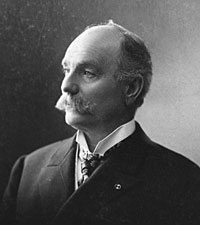

“This is an engraved portrait of Charles Whittlesey, a prominent soldier, attorney, scholar, newspaper editor, and geologist during the nineteenth century. He participated in a geological survey of Ohio conducted in the late 1830s, during which he discovered numerous Native American earthworks. In 1867, Whittlesey helped establish the Western Reserve Historical Society, and he served as the organization’s president until his death in 1886. Whittlesey also wrote approximately two hundred books and articles, mostly on geology and Ohio’s early history.”

~ Ohio History Central

General Force, then lieutenant-colonel under Colonel Whittlesey, fully describes the battle,2 and quotes General Wallace. “The nation is indebted to our brigade for the important services rendered, with the small loss it sustained and the manner in which Colonel Whittlesey handled it.”

Colonel Whittlesey was fortunate in escaping with his life, for General Force says, it was ascertained that the rebels had been deliberately firing at him, sometimes waiting to get a line shot.

Colonel Whittlesey had for some time been in bad health, and contemplating resignation, but deferring it for a decisive battle. Regarding this battle as virtually closing the campaign in the southwest, and believing the Rebellion to be near its end, he now sent it in.

General Grant endorsed his application, “We cannot afford to lose so good an officer.”

“Few officers,” it is said, “retired from the army with a cleaner or more satisfactory record, or with greater regret on the part of their associates.” The Twentieth was an early volunteer regiment. The men were citizens of intelligence and character. They reached high discipline without severity, and without that ill-feeling that often existed between men and their officers. There was no emergency in which they could not be relied upon. “Between them and their commander existed a strong mutual regard, which, on their part, was happily expressed by a letter signed by all the non-commissioned officers.”

“CAMP SHILOH, NEAR PITTSBURGH LANDING, TENNESSEE, April 21, 1862.

“COL. CHAS. WHITTLESEY:

“Sir — We deeply regret that you have resigned the command of the Twentieth Ohio. The considerate care evinced for the soldiers in camp, and, above all, the courage, coolness and prudence displayed on the battle-field, have inspired officers and men with the highest esteem for, and most unbounded confidence in our commander.

“From what we have seen at Fort Donelson, and at the bloody field near Pittsburgh, on Monday, the seventh, all felt ready to follow you unfalteringly into any contest and into any post of danger.

“While giving expression to our unfeigned sorrow at your departure from us, and assurance of our high regard and esteem for you, and unwavering confidence as our leader, we would follow you with the earnest hope that your future days may be spent in uninterrupted peace and quiet, enjoying the happy reflections and richly earned rewards of well-spent service in the cause of our blessed country in its dark hour of need.”

Said Mr. W. H. Searles, who served under him, at the memorial meeting of the Engineers Club of Cleveland: “In the war he was genial and charitable, but had that conscientious devotion to duty characteristic of a West Point soldier.”

Since Colonel Whittlesey’s decease the following letter was received:

“CINCINNATI, November 10, 1886.

“DEAR MRS. WHITTLESEY: — Your noble husband has got release from the pains and ills that made life a burden. His active life was a lesson to us how to live. His latter years showed us how to endure. To all of us in the Twentieth Ohio regiment he seemed a father. I do not know any other colonel that was so revered by his regiment. Since the war he has constantly surprised me with his incessant literary and scientific activity. Always his character was an example and an incitement. Very truly yours,

“M. F. Force.”

Colonel Whittlesey now turned his attention at once again to explorations in the Lake Superior and upper Mississippi basins, and “new additions to the mineral wealth of the country were the result of his surveys and researches.” His geological papers commencing again in 1863, show his industry and ability.

It happened during his life many times, and will happen again and again, that his labors as an original investigator have borne and will bear fruit long afterwards, and, as the world looks at fruition, of much greater value to others than to himself.

~ Report of a geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota: and incidentally of a portion of Nebraska Territory, by David Dale Owen, 1852, page 420.

He prognosticated as early as 1848, while on Dr. Owen’s survey, that the vast prairies of the northwest would in time be the great wheat region. These views were set forth in a letter requested by Captain Mullen of the Topographical Engineers, who had made a survey for the Northern Pacific railroad, and was read by him in a lecture before the New York Geographical society in the winter of 1863-4.

He examined the prairies between the head of the St. Louis river and Rainy Lake, between the Grand fork of Rainy Lake river and the Mississippi, and between the waters of Cass Lake and those of Red Lake. All were found so level that canals might be made across the summits more easily than several summits already cut in this country.

In 1879 the project attracted attention, and Mr. Seymour, the chief engineer and surveyor of New York, became zealous for it, and in his letters of 1880, to the Chambers of Commerce of Duluth and Buffalo, acknowledged the value of the information supplied by Colonel Whittlesey.

Says the Detroit Illustrated News:

“A large part of the distance from the navigable waters of Lake Superior to those of Red river, about three hundred and eight miles, is river channel easily utilized by levels and drains or navigable lakes. The lift is about one thousand feet to the Cass Lake summit. At Red river this canal will connect with the Manitoba system of navigation through Lake Winnipeg and the valleys of the Saskatchewan. Its probable cost is given at less than four millions of dollars, which is below the cost of a railway making the same connections. And it is estimated that a bushel of wheat may be carried from Red river to New York by water for seventeen cents, or about one-third of the cost of transportation by rail.”

We approach that part of the life of Colonel Whittlesey which was so valuable to our society. The society was proposed in 1866.3 Colonel Whittlesey’s own account of its foundation is: “The society originally comprised about twenty persons, organized in May, 1867, upon the suggestion of C. C. Baldwin, its present secretary. The real work fell upon Colonel Whittlesey, Mr. Goodman and Mr. Baldwin, Mr. Goodman devoting nearly all of his time until 1872 (the date of his death).” The statement is a very modest one on the part of Colonel Whittlesey. All looked to him to lead the movement, and none other could have approached his efficiency or ability as president of the society.

The society seemed as much to him as a child is to a parent, and his affection for it has been as great. By his learning, constant devotion without compensation from that time to his death, his value as inspiring confidence in the public, his wide acquaintance through the state, he has accomplished a wonderful result, and this society and its collections may well be regarded as his monument.

Mr. J. P. Holloway, in his memorial notice before the Civil Engineer’s club, of which Colonel Whittlesey was an honorary member, feelingly and justly said:

“Colonel Whittlesey will be best and longest remembered in Cleveland and on the Reserve, for his untiring interest and labors in seeking to rescue from oblivion the pioneer history of this portion of the state, and which culminated in the establishment of the present Western Reserve Historical society, of which for many years he was the presiding officer. It will be remembered by many here, how for years there was little else of the Western Reserve Historical society, except its active, hard working president. But as time moved on, and one by one the pioneers were passing away, there began to be felt an increasing interest in preserving not only the relics of a by-gone generation, but also the records of their trials and struggles, until now we can point with a feeling of pride to the collections of a society which owes its existence and success to a master spirit so recently called away.”

The colonel was remarkably successful in collecting the library, in which he interested with excellent pecuniary purpose the late Mr. Case. He commenced the collection of a permanent fund which is now over ten thousand dollars. It had reached that amount when its increase was at once stopped by the panic of 1873, and while it was growing most rapidly. The permanent rooms, the large and very valuable museum, are all due in greatest measure to the colonel’s intelligent influence and devotion.

I well remember the interest with which he received the plan; the instant devotion to it, the zeal with which at once and before the society was started, he began the preparation of his valuable book, The Early History of Cleveland, published during the year.

Colonel Whittlesey was author of — I had almost said most, and I may with no dissent say— the most valuable publications of the society. His own very wide reputation as an archaeologist and historian also redounded to its credit. But his most valuable work was not the most showy, and consisted in the constant and indefatigable zeal he had from 1867 to 1886, in its prosperity. These were twenty years when the welfare of the society was at all times his business and never off his mind. During the last few years Colonel Whittlesey has been confined to his home by rheumatism and other disorders, the seeds of which were contracted years before in his exposed life on Lake Superior, and he has not been at the rooms for years. He proposed some years since to resign, but the whole society would have felt that the fitness of things was over had the resignation been accepted. Many citizens of Cleveland recall that if Colonel Whittlesey could no longer travel about the city he could write. And it was fortunate that he could. He took great pleasure in reading and writing, and spent much of his time in his work, which continued when he was in a condition in which most men would have surrendered to suffering.

Colonel Whittlesey did not yet regard his labors as finished. During the last few years of his life religion, and the attitude and relation of science to it, engaged much of his thought, and he not unfrequently contributed an editorial or other article to some newspaper on the subject. Lately these had taken more systematic shape, and as late as the latter part of September, and within thirty days of his death, he closed a series of articles which were published in the Evangelical Messenger on “Theism and Atheism in Science.” These able articles were more systematic and complete than his previous writings on the subject, and we learn from the Messenger that they will be published in book form. The paper says:

Colonel Charles Whittlesey of this city, known to our readers as the author of an able series of articles on “Theism and Atheism in Science” just concluded, has fallen asleep in Jesus. One who knew the venerable man and loved him for his genuine worth said to us that “his last work on earth was the preparation of these articles . . . which to him was a labor of love and done for Christ’s sake.”

!["The Old Whittlesey Homestead, Euclid Avenue [Cleveland, Ohio]." ~ Historical Collections of Ohio in Two Volumes, by Henry Howe, 1907, page 521.](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/whittlesey-home-cleveland.jpg?w=300&h=207)

“The Old Whittlesey Homestead, Euclid Avenue.” [Cleveland, Ohio]

~ Historical Collections of Ohio in Two Volumes by Henry Howe, 1907, page 521.

Colonel Whittlesey was married October 4, 1858, to Mrs. Mary E. (Lyon) Morgan4 of Oswego, New York, who survives him; they had no children.

!["Char. Whittlesey - Cleveland Ohio, Oct. 30, 1895[?] - Geologist of Ohio." ~ Wisconsin Historical Society](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/charles-whittlesey-geologist.jpg?w=179&h=300)

Charles Whittlesey died on October 18th, 1886, and was never Ohio’s State Geologist.

“Char. Whittlesey – Cleveland Ohio, Oct. 30, 1895[?] – Geologist of Ohio.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Much of his work does not therefore appear in that complete and systematic shape which would make it best known to the general public. But by scholars in his lines of study in Europe and America, he was well known and very highly respected. “His contributions to literature,” said the New York Herald,5 “have attracted wide attention among the scientific men of Europe and America.”

Whittlesey Culture:

A.D. 1000 to 1600

“‘Whittlesey Culture’ is an archaeological designation referring to a Late Prehistoric (more appropriately: Late Pre-Contact) North American indigenous group that occupied portions of northeastern Ohio. This culture isdistinguished from other so-called Late Prehistoric societies mainly by distinctive kinds of pottery. Many Whittlesey communities were located on plateaus overlooking stream valleys or the shores of Lake Erie. The villages often were surrounded with a pallisade or a ditch, suggesting a need for defense.

“The Whittlesey culture is named for Charles Whittlesey, a 19th century geologist and archaeologist who was a founder of the Western Reserve Historical Society.”

As an American archaeologist, Colonel Whittlesey was very learned and thorough. He had in Ohio the advantage of surveying its wonderful works at an early date. He had, too, that cool poise and self-possession that prevented his enthusiasm from coloring his judgment. He completely avoided errors into which a large share of archaeologists fall. The scanty information as to the past and its romantic interest, lead to easy but dangerous theories, and even suffers the practice of many impositions. He was of late years of great service in exposing frauds, and thereby helped the science to a healthy tone. It may be well enough to say that in one of his tracts he exposed, on what was apparently the best evidence, the supposed falsity of the Cincinnati tablet so called. Its authenticity was defended by Mr. Robert Clarke of Cincinnati, successfully and convincingly, to Colonel Whittlesey himself. I was with the colonel when he first heard of the successful defense and with a mutual friend who thought he might be chagrined, but he was so much more interested in the truth for its own sake, than in his relations to it, that he appeared much pleased with the result.

Whittlesey Culture artifacts: “South Park Village points (above) and pottery fragment (below)”

~ Cuyahoga Valley National Park

Among American writers, Mr. Short speaks of his investigations as of “greater value, due to the eminence of the antiquarian who writes them.” Hon. John D. Baldwin says, “in this Ancient America speaks of Colonel Whittlesey as one of the best authorities.” The learned Frenchman, Marquis de Nadaillac and writers generally upon such subjects quote his information and conclusions with that high and safe confidence in his learning and sound views which is the best tribute to Colonel Whittlesey, and at the same time a great help to the authors. And no one could write with any fullness on the archaeology of America without using liberally the work of Colonel Whittlesey, as will appear in any book on the subject. He was an extensive, original investigator, always observing, thoughtful and safe, and in some branches, as in Ancient Mining at Lake Superior, his work has been the substantial basis of present learning. It is noticeable that the most eminent gentlemen have best appreciated his safe and varied learning. Colonel Whittlesey was early in the geological field. Fifty years ago little was known of paleontology, and Colonel Whittlesey cared little for it, perhaps too little; but in economic geology, in his knowledge of Ohio, its surface, its strata, its iron, its coal and its limestone in his knowledge of the copper and iron of the northwest, he excelled indeed. From that date to his death he studied intelligently these sections. As Professor Lapham said he was studying Wisconsin, so did Colonel Whittlesey give himself to Ohio, its mines and its miners, its manufactures, dealings in coal and iron, its history, archaeology, its religion and its morals. Nearly all his articles contributed to magazines were to western magazines, and anyone who undertook a literary enterprise in the state of Ohio that promised value was sure to have his aid.6

In geology his services were great. The New York Herald, already cited, speaks of his help toward opening coal mines in Ohio and adds,“he was largely instrumental in discovering and causing the development of the great iron and copper regions of Lake Superior.” Twenty-six years ago he discovered a now famous range of iron ore.

“ On the Mound Builders and on the geological character and phenomena of the region of the lakes and the northwest he was quoted extensively as an authority in most of the standard geological and anthropological works of America and Europe,” truthfully says the ‘Biographical Cyclopedia.

Colonel Whittlesey was as zealous in helping to preserve new and original material for history as for science. In 1869 he pushed with energy the investigation, examination and measures which resulted in the purchase by the State of Ohio of the St. Clair papers so admirably, fully and ably edited by Mr. William Henry Smith, and in 1882 published in two large and handsome volumes by Messrs. Robert Clarke and Co. of Cincinnati.

Colonel Whittlesey was very prominent in the project which ended in the publication of the Margry papers in Paris. Their value may be gathered from the writing of Mr. Parkman (La Salle) and The Narrative and Critical History of America, Volume IV., where on page 242 is an account of their publication.7 In 1870 and 1871 an effort to enlist congress failed. The Boston fire defeated the efforts of Mr. Parkman to have them published in that city. Colonel Whittlesey originated the plan eventually adopted, by which congress voted ten thousand dollars as a subscription for five hundred copies, and, as says our history: “at last by Mr. Parkman’s assiduous labors in the east, and by those of Colonel Whittlesey, Mr. O. H. Marshall and others in the west,” the bill was passed.

The late President Garfield, an active member of our society, took a lively interest in the matter, and instigated by Colonel Whittlesey used his strong influence in its favor. Mr. Margry has felt and expressed a very warm feeling for Colonel Whittlesey for his interest and efforts, and since the colonel’s death, and in ignorance of it, has written him a characteristic letter to announce to the colonel, first of any in America, the completion of the work. A copy of the letter follows :

“PARIS, November 4, 1886.

“VERY DEAR AND HONORED SIR: It is to-day in France, St. Charles’ day, the holiday I wished when I had friends so called. I thought it suitable to send you to-day the good news to continue celebrating as of old. You will now be the first in America to whom I write it. I have just given the check to be drawn, for the last leaves of the work, of which your portrait may show a volume under your arm.8 Therefore there is no more but stitching to be done to send the book on its way.

“In telling you this I will not forget to tell you that I well remembered the part you took in that, publication as new, as glorious for the origin of your state, and for which you can congratulate yourself, in thanking you I have but one regret, that Mr. Marshall can not have the same pleasure. I hope that your health as well as that of Madame Whittlesey is satisfactory. I would be happy to hear so. For me if I am in good health it is only by the intervention of providence. However, I have lost much strength, though I do not show it. We must try to seem well.

“Receive, dear and honored sir, and for Madame, the assurance of my profound respect and attachment.

“PIERRE MARGRY.”

Colonel Whittlesey views of the lives of others were affected by his own. Devoted to extending human learning, with little thought of self interest, he was perhaps a little too impatient with others, whose lives had other ends deemed by them more practical. Yet after all, the colonel’s life was a real one, and his pursuits the best as being nearer to nature and far removed from the adventitious circumstances of what is ordinarily called polite life.

He impressed his associates as being full of learning, not from books, but nevertheless of all around — the roads the fields, the waters, the sky, men animals or plants. Charming it was to be with him in excursions; that was really life and elevated the mind and heart.

He was a profoundly religious man, never ostentatiously so, but to him religion and science were twin and inseparable companions. They were in his life and thought, and he wished to and did live to express in print his sense that the God of science was the God of religion, and that the Maker had not lost power over the thing made.

He rounded and finished his character as he finished his life, by joint and hearty affection and service to the two joint instruments of God’s revelation, for so he regarded them. Rev. Dr. Hayden testifies: “He had no patience with materialism, but in his mature strength of mind had harmonized the facts of science with the truths of religion.”

Charles Whittlesey

~ Magazine of Western History, Volume V, page 536.

Colonel Whittlesey’s life was plain, regular and simple. During the last few years he suffered much from catarrhal headache, rheumatism and kindred other troubles, and it was difficult for him to get around even with crutches. This was attributed to the exposure he had suffered for the fifteen years he had been exposed in the Lake Superior region, and his long life and preservation of a clear mind was no doubt due to his simple habits. With considerable bodily suffering, his mind was on the alert, and he seemed to have after all considerable happiness, and, to quote Dr Hayden, he could say with Byrd, “thy mind to me a kingdom is.”

Colonel Whittlesey was an original member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, an old and valued member of the American Antiquarian society, an honorary member of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical society, with headquarters at Columbus. He was trustee of the former State Archaeological society (making the archaeological exhibition at the Centennial), and although each of these is necessarily to some extent a rival of his pet society, he took a warm interest in the welfare of each.

He was a member of the Society of Americanites of France, and his judgment, learning and communications were much esteemed by the French members of that society. Of how many other societies he was an honorary or other member I can not tell.

C. C. Baldwin.

1 – Speech of May 9, 1862.

2 – Cincinnati Commercial, April 9, 1862.

3 – The society was organized under the auspices of the Cleveland Library Association (now Case Library). The plan occurred to the writer while vice-president of that association. At the annual meeting in 1867, the necessary changes were made in the constitution, and Colonel Whittlesey was elected to the Case Library board for the purpose of heading the historical committee and movement. The result appears in a scarce pamphlet issued in 1867 by the library association, containing, among other things, an account of the formation of the society and an address by Colonel Whittlesey, which is an interesting sketch of the successive literary and library societies of Cleveland, of which the first was in 1811.

4 – Mary E. Lyon was a daughter of James Lyon of Oswego, and sister of John E. Lyon, now of Oswego but years ago a prominent citizen of Cleveland. She m. first Colonel Theophilus Morgan,6 Theophilus,5 Theophilus,4 Theophilus,3 John,2 James Morgan.1 Colonel Morgan was an honored citizen of Oswego. Colonel Morgan and his wife Mary, had a son James Sherman, a very promising young man, killed in 1864 in a desperate cavalry charge in which he was lieutenant, in Sherman’s march to the sea. Mrs. Whittlesey survives in Cleveland.

5 – October, 19, 1886.

6 – The Hesperian, American Pioneer, the Western Literary Journal and Review of Cincinnati, the Democratic Review and Ohio Cultivator of Columbus, and later the Magazine of Western History at Cleveland, all received his hearty support.

7 – These papers were also described in an extract from a congressional speech of the late President Garfield. The extract is in Tract No. 20 of the Historical society.

8 – Alluding to a photograph of Colonel Whittlesey

then with a book under his arm.

Land Office Frauds

March 25, 2016

By Amorin Mello

New York Times

December 9, 1858

—~~~0~~~—

Land Office Frauds.

—~~~0~~~—

AGRICULTURAL CAPABILITIES HEREABOUT – LOCAL AMUSEMENTS AND EXCITEMENTS – SETTLEMENTS OF SUPERIOR CITY – A CONTROVERSY, AND SECRETARY M’CLELLAND’S ADJUDICATION OF IT – SECRETARY THOMPSON’S REVERSAL OF THAT JUDGEMENT – ITS CONSEQUENCES – LAND-STEALING RAMPANT – INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE ENTRY OF SUPERIOR CITY – THE LAND OFFICE REPEALS THE LAW OF THE LAND – A CASE FOR INVESTIGATION.

Correspondence of the New-York Times.

SUPERIOR CITY, Wis., Thursday, Nov. 25.

I am booked here for another winter, but fortunately with no fear of starvation this time. We have been most successful the last Summer in our Agricultural labors. The clay soils about here has proved marvelously fruitful, and where we expected little or nothing it has turned out huge potatoes that almost dissolve under the steaming process, and open as white as the inside of a cocoa-nut ; mammoth turnips, as good as turnips can be ; cabbages of enormous size ; and cauliflowers, that queen of vegetables, weighing as much as a child a year old. There is no reason to fear for the future of this country, now that we can show such vegetable products, and talk of our gardens as well as of our mines, forests, furs, and fisheries.

We are not without our excitements here, too ; though we have no model artists, or theatrical exhibitions, to treat our friends with. But our little city is now in a state of commotion produced by causes which often agitate frontier life, and sometimes reach the great center with their echo or reverberation. The Land Office is the great point of interest to frontier men, and the land law is the only jurisprudence save Lynch law, in which we are particularly interested. And as we have no means of reaching the great Federal legislature, through our Local Presses, we are always glad of an opportunity to be heard through the Atlantic organs, which are heard all over the country, and strike a note which the wind takes up and carries not only to San Francisco, but up here to the mouth of the St. Louis River, the hereafter great local point of Pacific and Atlantic intercommunication.

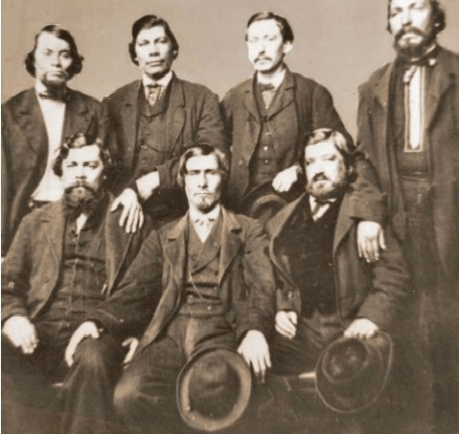

The Eye of the Northwest, pg. 8: James Stinson; Benjamin Thompson; W. W. Corcoran; U. S. Senator Robert J Walker; George W Cass; and Horace S Walbridge.

Five or six years ago a few American pioneers – stalwart backwoodsmen, undertook to select a town site out here, and did select one in good faith, and with clubs and muskets in had fought off from their premises a gang of Indians who were claiming to preëmpt it as “American citizens.” The Indians, however, were backup up by a Canadian white man by the name of STINSON, and some of the great speculators who were engaged in another town enterprise alongside here, and this “Indian war” was protracted in the local and general Land Offices some two or three years, when Mr. M’CLELLAND, then Secretary of the Interior, made a final adjudication of all the legal questions involved in the controversy, and sent it back to the Land Office to ascertain and apply the facts to the law as settled, on great deliberation by himself and Mr. CUSHING.

More Proprietors of Superior from The Eye of the North-west

, pg. 9: [names are illegible]

Meanwhile the original settlers and occupants maintained their adverse possession against the Indians and all the world, and expended a good deal of money in erecting buildings and a pier, and in cutting out streets and in laying out their town, and in carrying on their litigation, which was by no means inexpensive. M’CLELLAND’s determination of the law in their favor encouraged them to go on and incur additional expenses ; and they parted with diverse interests in the town site, some by assignment to persons who advanced money, and some by sale on quit-claim to persons who covenanted to make improvements. They made application to the proper office to enter the site, and nobody objected but the Indians – and the Indians were nowhere. So things stood when the case went back to the General Land Office, and to Mr. Secretary THOMPSON. The worthy Secretary, for some cause altogether unaccountable, adopted the extraordinary (and under the decision of the Supreme Court illegal) course of reversing the final judgement of his predecessor in this very case, (an exercise of power entirely unheard of in a case of mere private right,) and of rejecting the claim of the original occupants and settlers, though it was not contested by somebody who had a better right.

You may well imagine that this decision excited no little astonishment here. All the land stealers looked upon Superior City as vacant ground. They thought the men who selected and settled the town site were outlawed, and had no interests. Some supposed that the Land Office would put the ground up at auction. A chap by the name of SWEETZER came on here fresh from the General Land Office, and undertook to lay Sioux scrip on the whole site. Another – one JOHN GRANT – made application to preëmpt a portion of the site – and, what is the most remarkable feature about this business, GRANT was permitted to enter it as a preëmptor, though it was notoriously a selected town site, and in the adverse possession of town claimants half a year before GRANT ever saw it. This outrage created a great excitement for a small place. The Register, Mr. DANIEL SHAW, excuses himself by saying that he was almost expressly ordered by HENDRICKS to issue the certificate to GRANT, but this we do not believe in these parts. SHAW is clever, and covers his tracks, but nobody here supposes that the Commissioner ever countenanced such a gross violation of a public statute, without a motive. And what motive could the Commissioner have?

But, besides these movements, one of the Indians – ROY by name, who was defeated as one of the claimants by preëmeption – is now seeking to locate his Chippewa scrip on the town-site, and it is supposed that the same influences which urged him as an American citizen will support his claim as an Indian. A white man by the name of KINGSBURY, encouraged by the disregard of law exhibited by the local office, has made a claim on another part of the town-site. This purports to have originated in the fourth year of a litigation between the town claimants and the illegal preëmptors, and is supposed to be stimulated and encouraged by the Register.Subsequently to his original rejection of the town-site claim, Mr. Secretary THOMPSON issued instructions to permit the entry, and the County Judge made application on the 18th instant, under the law of the United States, May 23, 1844. On this being known, some of the persons heretofore claiming under the original settlers and occupants (who had selected the town and paid all the expenses of the settlement) came together and formed an organization as a city, under a recent law of Wisconsin, the object of which they declare to be secure to themselves a title from the United States to the lots they specially occupy, and to sell the balance to defray their expenses in entering and alloting the land! The men whose rights vested under the absolute decision of Secretary MCCLELLAND, and who did all that they could do to enter the land, and paid the money for it more than two years ago, – the men whose “respective INTERESTS” the statute of 1844 recognizes and was designed to protect, – these men are all ruled off the course, and the men claiming under them have conspired to divide the land and its proceeds among themselves.

Of course these iniquitous and illegal proceedings are all within the reach of the Courts – but they are the legitimate consequence of Mr. JACOB THOMPSON’s repeal of so much of the Preëmption Law of 1841 as excludes from preëmption those portions of the public lands that have been “selected as the site of a city or town.” Mr. THOMPSON has overruled all his predecessors, all the Attorney-General, all the local offices, all the lexicographers, and the English language generally, by deciding solemnly that “selection” does not mean “selection,” but means something else – or more particularly nothing at all. Because, says he, if adverse “selection” excluded a preëmptor, then a preëmptor might be excluded by a false allegation of selection. Was there ever such an argal since Dogberry’s time? The Secretary has discovered an equally efficient “dispensing power” with that of King JAMES of blessed memory, and one which his brethren in the Cabinet may use very efficiently, if Congress does not look into the subject and fix some limits to it. For now, not only the Secretary, but the Commissioner, and the Register and Receiver, all think that they are at liberty to treat the repeal by the Secretary as an effective nullification of the law of the land.

If Congress would amuse their leisure a little by looking at these land office operations on the verge of civilization, they would strike a placer of corruption. Let them open the books and call for the documents, and see what Dr. T. RUSH SPENSER, late Register of the Willow River District, says of his predecessor and successor, Mr. JOHN O. HENNING, and then ascertain by what influences HENNING has been reappointed, and SPENSER transferred to Superior. Let them find out what Receiver DEAN said of Register SHAW, and what Register SHAW said of Receiver DEAN, and why DEAN was dismissed and why SHAW was retained. It will be rare fun for somebody. The country ought to know something about the Land Offices, and such an investigation as this would enlighten the country very materially. I hope it will be made, and that the country will learn how it is that more land has been entered in this district by Indians, foreigners, and minors than by qualified preëmptors, and all for the benefit of a few favored speculators.

The Woman In Stone

March 15, 2016

By Amorin Mello & Leo Filipczak

Photograph of the Wheeler and Wood Families from the Wheeler Family Papers at the Wisconsin Historical Society. The woman dressed in white is Harriet Martha Wheeler, according to the book about her mother, Woman in the Wilderness: Letters of Harriet Wood Wheeler, Missonary Wife, 1832-1892, by Nancy Bunge, 2010.

![Leonard Hemenway Wheeler ~ Unnamed Wisconsin by [????]](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/leonard-hemenway-wheeler-from-unnamed-wisconsin.jpg?w=237&h=300)

Leonard Hemenway Wheeler: husband of Harriet Wood Wheeler, and father of author Harriet Martha Wheeler.

~ Unnamed Wisconsin, by John Nelson Davidson, 1895.

Harriet Wood Wheeler: wife of Leonard Wheeler, and mother of author Harriet Martha Wheeler.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

This is a reproduction of the final chapter from Harriet Martha Wheeler’s 1903 book, The Woman in Stone: A Novel. If you want to read the entire novel without spoiling the final chapter featured here, you can download it here as a PDF file: The Woman in Stone: A Novel. Special thanks to Paul DeMain at Indian Country Today Media Network for making the digitization of this novel possible for the public to read with convenience.

“Hattie” was named after her mother, Harriet Wood Wheeler; the wife of Reverend Leonard Hemenway Wheeler. Hattie was born in 1858 at Odanah, shortly after the events portrayed in her novel. Hattie’s experiences and writings about the Lake Superior Chippewa are summarized in an academic article by Nancy Bunge, published in The American Transcendental Quarterly , Vol. 16, No. 1 , March 2002: Straddling Cultures: Harriet Wheeler’s and William W. Warren’s Renditions of Ojibwe History

William Whipple Warren (c. 1851)

~ Wikimedia.org

“Mary Warren English, White Earth, Minnesota”

~ University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library, NEMHC Collections

Harriet Wheeler and William W. Warren not only both lived on Ojibwe reservations in northern Wisconsin during the nineteenth century, but their families had strong bonds between them. William Warren’s sister, Mary Warren English, writes that her brother returned to La Pointe, Wisconsin, from school on the same boat Harriet’s parents took to begin their mission work. The Wheelers liked him and appreciated his help: “He won a warm and life-long friendship–with these most estimable people–by his genial and happy disposition–and ever ready and kindly assistance–during their long and tedious voyage” (Warren Papers). When Mary Warren English’s parents died, she moved in with the Wheelers, and, long after she and Harriet no longer shared the same household, she began letters to Harriet with the salutation, “Dear Sister.” But William Warren’s History of the Ojibwe People (1885) and Harriet Wheeler’s novel The Woman in Stone (1903) reveal that this shared background could not overcome the cultural differences between them. Even though Wheeler and Warren often describe the same events and people, their accounts have different implications. Wheeler, the daughter of Congregational missionaries from New England, portrays the inevitable and necessary decline of the Ojibwe, as emissaries of Christianity help civilization progress; Warren, who had French and Ojibwe ancestors, as well as Yankee roots, identifies growing Anglo-Saxon influence on the Ojibwe as a cause of moral decay.

Hattie’s book appears to provide some valuable insights about certain events in Chequamegon history, yet it is clearly erroneous about other such events. According to the University of Wisconsin – Madison, Harriet’s novel is “based on discovery of petrified body of Indian woman in northern Wisconsin.” This statement seems to acknowledge this peculiar event as being somewhat factual. However, Hattie’s novel is clearly a work of fiction; it appears that some of her references were to actual events. At this point in time, this mystery of the forest may never be thoroughly confirmed or debunked.

An incomplete theater screenplay, with the title “Woman in Stone,” was also written by Hattie. It appears to be based on her novel, can be found at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center Archives, in the Wheeler Family Papers: Northland Mss 14; Box 10; Folder 19. However, only several pages of this screenplay copy still exist in the archive there. A complete copy of Hattie’s screenplay may still exist somewhere else yet.

The Woman in Stone: A Novel by Harriet Martha Wheeler, 1903.

[Due to the inconsistencies found in Hattie’s novel, we have omitted most of this novel for this reproduction. We shall skip to the final chapter of Hattie’s novel, to the rediscovery of long lost “Wa-be-goon-a-quace,” the Little Flower Girl. If you want to read the entire novel first, before spoiling this final chapter, you can download it here: The Woman in Stone: A Novel, by Harriet Wheeler, 1903. Special thanks to Paul DeMain at Indian Country Today Media Network for making the digitization of this novel possible for the public to read with convenience.]

(Pages 164-168)

CHAPTER XX.

THE DISCOVERY OF THE WOMAN IN STONE

A hundred years swept over the island Madelaine, bringing change and decay in their train. But, nature renews the waste of time with a prodigal hand and robed the island in verdant loveliness.

Madelaine still towers the queen of the Apostle group, with rocky dells and pine clad shores and odorous forests, through which murmur the breezes from the great lake, and over all hover centuries of history, romance, and legendary lore.

Jean Michel Cadotte was Madelaine’s father-in-law, not husband. Madelaine Cadotte’s Ojibwe name was Ikwezewe, and she was still alive at La Pointe, in her ’90s, during Hattie‘s childhood in Odanah. It’s kind of disturbing how little of this Hattie got right considering Mary Warren (Madeline’s granddaughter) was basically Hattie’s stepsister.

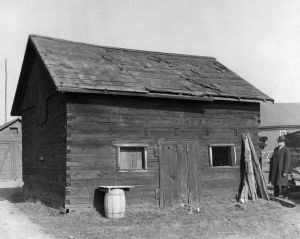

Evolution toward the spiritual is the destiny of humanity and in this trend of progress the Red Men are vanishing before the onward march of the Pale Face. In the place of the blazing Sacred Fire stands the Protestant Mission. The settlers’ cabin supplants the wigwam. No longer are heard the voyageur’s song and the rippling canoes. This is the age of steam, and far and near echoes the shrill whistle. Overgrown mounds mark the sites of the forts of La Ronde and Cadotte. In the spacious log cabin of Jean and Madelaine Cadotte lives their grandson, John Cadotte.

“Dirt trail passing log shack that was probably the home of Michael and Madeline Cadotte, La Pointe,” circa 1897.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

A practical man is John. He tills his garden, strings his fish-net in the bay, and acts as guide, philosopher and friend for all the tourists who visit the island.

Hildreth Huntington and his father may have been fictionalized, or they may be actual people from the Huntington clan:

by the Huntington Family Association, 1915.

On a June morning of the year 1857, John sat beneath a sheltering pine mending his fish-net. he smoked a cob-pipe, which he occasionally laid by to whistle a voyageur’s song. A shrill whistle sounded and a tug steamed around the bend to the wharf. John laid aside his fish-net and pipe and strolled to the beach. Two gentlemen, clad in tourist’s costume, stepped from the tug and approached John.

“Can you direct us to Mr. John Cadotte?” said the elder man.

“I am your man,” responded John.

Augustus Hamilton Barber had copper and land claims around the Montreal and Tyler Forks Rivers before his death in 1856. It is possible that this father and son pair in Hattie’s novel actually represent Joel Allen Barber and his father, Giles Addison Barber. They were following up on their belated Augustus’ unresolved business in this area during June of 1857. This theory about the Barber family is explored in more details with “Legend of the Montreal River,” by George Francis Thomas.

“My name is Huntington. This young man is my son, Hildreth. We came from New York, and are anxious to explore the region about Tyler’s fork where copper has been discovered. We were directed to you as a guide on whom we might depend. Can we secure your services, sir?” asked the stranger.

“It is also proper to state in addition to what has been already mentioned, that at, or about this time [1857], a road was opened by Mr. Herbert’s order, from the Hay Marsh, six miles out from Ironton, to which point one had been previously opened, to the Range [on the Tyler Forks River], which it struck about midway between Sidebotham’s and Lockwood’s Stations, over which, I suppose, the 50,000 tons as previously mentioned, was to find its way to Ironton, (in a horn).“

~ Penokee Survey Incidents: IV

“I am always open to engagement,” responded John.

“Very well, we will start at once, if agreeable to you.”

“I will run up to the house and pack my traps,” said John.

The stranger strolled along the beach until John’s return. Then all aboard the tug and steamed away towards Ashland. John entertained the strangers with stories and legends of those romantic and adventurous days which were fading into history.

“The company not being satisfied with Mr. Herbert as agent, he was removed and Gen. Cutler appointed in his place, who quickly selected Ashland as headquarters, to which place all the personal property, consisting of merchandise principally, was removed during the summer by myself upon Gen. C.’s order – and Ironton abandoned to its fate.”

~ Penokee Survey Incidents: I

The party left the tug at Ashland and engaged a logger’s team to carry them to Tyler’s Forks, twenty miles away. A rough road had been cut through the forest where once ran an Indian trail. Over this road the horses slowly made their way. Night lowered before they had reached their destination and they pitched their tents in the forest. John kindled a camp-fire and prepared supper. The others gathered wood and arranged bough beds in the tent. They were wearied with the long and tedious journey and early sought this rude couch.

John’s strident tones summoned them to a sunrise breakfast. They broke camp and resumed their journey, arriving at the Forks at noon.

The tourists sat down on the banks of the river and viewed the beautiful falls before them.

“This is the most picturesque spot I have seen, Hildreth. It surpasses Niagara, to my mind,” said Mr. Huntington.

The preface to this novel is a photograph of Brownstone Falls, where the Tyler Forks River empties into the Bad River at Copper Falls State Park. George Francis Thomas’ “A Mystery of the Forest” was originally published as “Legend of the Montreal River“ (and republished here). It suggests that the legend takes place at the Gorge on the Tyler Forks River, where it crosses the Iron Range; not where it terminates on Bad River along the Copper Range.

They gazed about them in wondering admiration. The forest primeval towered above them. Beyond, the falls rolled over their rocky bed. The ceaseless murmur of the rapids sounded below them and over all floated the odors of the pines and balsam firs.

“This description will, I think, give your readers a very good understanding of the condition as well as the true inwardness of the affairs of the Wisconsin & Lake Superior Mining and Smelting Co., in the month of June, 1857.”

[…]

“Rome was not built in a day, but most of these cabins were. I built four myself near the Gorge [on Tyler Forks River], in a day, with the assistance of two halfbreeds, but was not able to find them a week afterwards. This is not only a mystery but a conundrum. I thinksome traveling showman must have stolen them; but although they werenon est we could swear that we had built them, and did.“

~ Penokee Survey Incidents: IV

After dinner the party began their explorations under John’s leadership. Two days were spent in examining the banks of Bad River. On the third morning they came to the gorge. Here, the river narrowed to a few feet and cut its way through high banks of rock. The party examined the rocks on both sides. John climbed to the pool behind the gorge and examined the rocks lying beneath the shallow water. He rested his hand on what seemed to be a water-soaked log and was surprised to find the log a solid block of stone. He examined it carefully. The stone resembled a human form.

“Mr. Huntington, come down here,” he called.

“Have you struck a claim, John?” asked Mr. Huntington.

“Not exactly. Look at this rock. What do you call it, sir?”

Mr. Huntington, his son and the teamster climbed down to the pool and examined the rock.

“A petrification of some sort,” exclaimed Mr. Huntington. “Let us lift it from the water.”

The men struggled some time before they succeeded in raising the solid mass. They rested it against the rocky bank.

Wabigance: Little Flower Girl

Hattie identified this character as “Wa-be-goon-a-quace.” In the Ojibwemowin language, Wabigance is a small flower. Wabigon or Wabegoon is a flower. Wabegoonakwe is a flower that is female.

“A petrified Indian girl,” exclaimed Mr. Huntington.

The men bent low over the strange figure, examining it carefully.

“Look at her moccasins, father,” exclaimed Hildreth, “and her long hair. Here is a rosary and cross about her neck. Evidently she was a good Catholic.”

“Holy Mother,” exclaimed John, “it is the Little Flower Girl.”“And who was she?” asked Mr. Huntington.

“She was my grandmother Madelaine’s cousin. I have heard my grandmother tell about her many times when I was a boy. The Little Flower Girl lost her mind when her pale-faced lover died in battle. She was always hunting for him in the island woods. One evening she disappeared in her canoe and never returned.”

“How came she by this cross?”

“The Holy Father Marquette gave it to her grandmother, Ogonã. The Little Flower Girl wore it always. She thought it protected her from evil and would lead her to her lover, Claude.”

And so it has. The cross has led the Little Flower Girl up yonder where she has found her Claude and life immortal.

“A touching romance, worthy to be embalmed in stone,” said Hildreth.

“Barnum’s Museum Fire, New York City, 1868 Incredible view of the frozen ruins of Barnum’s ‘American Museum’ just after the March, 1868 fire. 3-1/4×6-3/4″ yellow-mount view published by E & HT Anthony; #5971 in their series of ‘Anthony’s Stereoscopic Views.’ Huge ice formations where the water sprays hit the building; burned out windows and doors.”

~ CraigCamera.com

“Yes, and worthy of a better resting place,” responded Mr. Huntington. “We must take the Little Flower Girl with us, Hildreth. Her life belongs to the public. Our great city will be better for this monument of her romantic, tragic, sorrowing life.”

Over the forest road, where her moccasined feet had strayed one hundred years before, they bore the Little Flower Girl. And the eyes of the Holy Father shone on her as she crossed the silvery water where her “Ave Maria” echoed long ago. Back to the island Madelaine they carried her, and on, down the great lakes, the Little Flower Girl followed in the wake of her lover, Claude. To the great city of New York they bore her. In one of that great city’s museum rests the Woman in Stone.

The Removal Order of 1849

March 12, 2016

By Amorin Mello

United States. Works Progress Administration:

Chippewa Indian Historical Project Records 1936-1942

(Northland Micro 5; Micro 532)

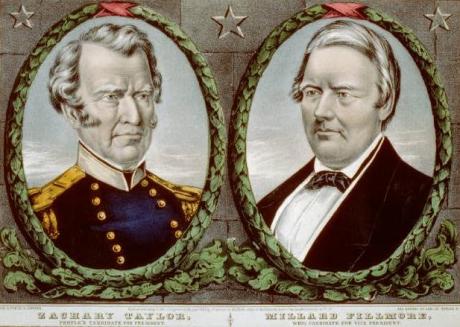

12th President Zachary Taylor gave the 1849 Removal Order while he was still in office. During 1852, Chief Buffalo and his delegation met 13th President Millard Fillmore in Washington, D.C., to petition against this Removal Order.

~ 1848 presidential campaign poster from the Library of Congress

Reel 1; Envelop 1; Item 14.

The Removal Order of 1849

By Jerome Arbuckle

After the war of 1812 the westward advance of the people of the United States of was renewed with vigor. These pioneers were imbued with the idea that the possessions of the Indian tribes, with whom they came in contact, were for their convenience and theirs for the taking. Any attempt on the part of the aboriginal owners to defend their ancestral homes were a signal for a declaration of war, or a punitive expedition, which invariably resulted in the defeat of the Indians.

“Peace Treaties,” incorporating terms and stipulations suitable particularly to the white man’s government, were then negotiated, whereby the Indians ceded their lands, and the remnants of the dispossessed tribe moved westward. The tribes to the south of the Great Lakes, along the Ohio Valley, were the greatest sufferers from this system of acquisition.

Another system used with equal, if less sanguinary success, was the “treaty system.” Treaties of this type were actually little more than receipt signed by the Indian, which acknowledged the cessions of huge tracts of land. The language of the treaties, in some instances, is so plainly a scheme for the dispossession and removal of the Indians that it is doubtful if the signers for the Indians understood the true import of the document. Possibly, and according to the statements handed down from the Indians of earlier days to the present, Indians who signed the treaties were duped and were the victims of treachery and collusion.

By the terms of the Treaties of 1837 and 1842, the Indians ceded to the Government all their territory lying east of the Mississippi embracing the St. Croix district and eastward to the Chocolate River. The Indians, however, were ignorant of the fact that they had ceded these lands. According to the terms, as understood by them, they were permitted to remain within these treaty boundaries and continue to enjoy the privileges of hunting, fishing, ricing and the making of maple sugar, provided they did not molest their white neighbors; but they clearly understood that the Government was to have the right to use the timber and minerals on these lands.

Entitled “Chief Buffalo’s Petition to the President“ by the Wisconsin Historical Society, the story behind this now famous symbolic petition is actually unrelated to Chief Buffalo from La Pointe, and was created before the Sandy Lake Tragedy. It is a common error to mis-attribute this to Chief Buffalo’s trip to Washington D.C., which occurred after that Tragedy. See Chequamegon History’s original post for more information.

Detail of Benjamin Armstrong from a photograph by Matthew Brady (Minnesota Historical Society). See our Armstrong Engravings post for more information.

Their eyes were opened when the Removal Order of 1849 came like a bolt from the blue. This order cancelled the Indians’ right to hunt and fish in the territory ceded, and gave notification for their removal westward. According to Verwyst, the Franciscan Missionary, many left by reason of this order, and sought a refuge among the westernmost of their tribe who dwelt in Minnesota.

Many of the full bloods, who naturally had a deep attachment for their home soil, refused to budge. The chiefs who signed the treaty were included in this action. They then concluded that they were duped by the Treaty Commissioners and were given a faulty interpretation of the treaty passages. Although the Chippewa realized the futility of armed resistance, those who chose to remain unanimously decided to fight it out. A few white men who were true friends of the Indians, among these was Ben Armstrong, the adopted son of the Head Chief, Buffalo, and he cautioned the Indians against any show of hostility.