Diplomacy in the Time of Cholera: why there was no Ojibwe delegation to President Taylor in the winter of 1849-50

December 15, 2024

By Leo

At Chequamegon History, we deal mostly in the micro. By limiting our scope to a particular time and place, we are all about the narrow picture. Don’t come here for big universal ideas. The more specific and obscure a story, the more likely it is to appear on this website.

Madeline Island and the Chequamegon region are perfect for the specific and obscure. In the 1840s, most Americans would have thought of La Pointe as remote frontier wilderness, beyond the reach of worldwide events. Most of us still look at our history this way.

We are wrong. No man is an island, and Madeline Island–though literally an island–was no island.

This week, I was reminded of this fact while doing research for a project that has nothing to do with Chequamegon History. While scrolling through the death records of the Greek-Catholic church of my ancestral village in Poland, I noticed something strange. The causes of deaths are usually a mishmash of medieval sounding ailments, all written in Latin, or if the priest isn’t feeling creative or curious, the death is just listed as ordinaria.

In the summer of 1849, however, there was a noticeable uptick in death rate. It seemed my 19th-century cousins, from age 7 to 70, were all dying of the same thing:

Cause of death in right column. Akta stanu cywilnego Parafii Greckokatolickiej w Olchowcach (1840-1879). Księga zgonów dla miejscowości Olchowce. https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/en/jednostka/-/jednostka/22431255

Cholera is a word people my age first learned on our Apple IIs back in elementary school:

At Herbster School in 1990, we pronounced it “Cho-lee-ra.” It was weird the first time someone said “Caller-uh.” You can play online at https://www.visitoregon.com/the-oregon-trail-game-online/

It is no coincidence. If you note the date of leaving Matt’s General Store in Independence Missouri, Oregon Trail takes place in 1848.

Diseases thrive in times of war, upheaval, famine, and migration, and 1848 and 1849 certainly had plenty of all of those. A third year of potato blight and oppressive British policies plunged the Irish poor deeper into squalor and starvation. The millions who were able to, left Ireland. Meanwhile, the British conquest of the Punjab and the “Springtime of Nations” democratic revolutions across central Europe meant army and refugee camps (notorious vectors of disease) popped up across the Eurasian continent.

North America had seen war as well. The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (1848) ended the Mexican-American War and delivered half of Mexico over to Manifest Destiny. The discovery of gold in California, part of this cession, brought thousands of Chinese workers to the West Coast, while millions of Irish and Germans arrived on the East Coast. Some of those would also find their way west along the aforementioned Oregon Trail.

Closer to home, these German immigrants meant statehood for Wisconsin and the shifting of Wisconsin’s Indian administration west to Minnesota Territory. Eyeing profits, Minnesota and Mississippi River interests were increasingly calling for the removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe bands from Wisconsin and Michigan. This caused great alarm and uncertainty at La Pointe.

All of these seemingly disparate events of 1848 and 1849 are, in fact, related. One of the most obvious manifestations was that displaced people from all these places impacted by war, poverty, and displacement carried cholera. The disease arrived in the United States multiple times, but the worst outbreak came up Mississippi from New Orleans in the summer of 1849. It ravaged St. Louis, then the Great Lakes, and reached Sault Ste, Marie and Lake Superior by August.

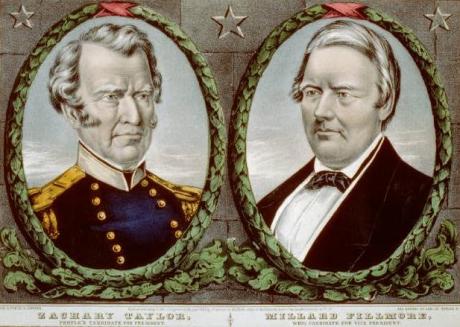

Longtime Chequamegon History readers will know my obsession with the Ojibwe delegation that left La Pointe in October 1848 and visited Washington D.C. in February 1849. It is a fascinating story of a group of chiefs who brought petitions (some pictographic) laying out their arguments against removal to President James K. Polk and Congress. The chiefs were well-received, but ultimately the substance of their petitions was not acted upon. They arrived after the 1848 elections. Polk and the members of Congress were lame ducks. General Zachary Taylor had been elected president, though he wasn’t inaugurated until the day after the delegation left Washington.

If you’ve read through our DOCUMENTS RELATED TO THE OJIBWE DELEGATION AND PETITIONS TO PRESIDENT POLK AND CONGRESS 1848-1849, you’ll know that both Polk and the Ojibwe delegation’s translator and alleged ringleader, the colorful Jean-Baptiste Martell of Sault Ste. Marie, died of cholera that summer.

So, in this post, we’re going to evaluate three new documents, just added to the collection, and look at how the cholera epidemic partially led to the disastrous removal of 1850, commonly known as the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

The first document is from just after the delegation’s arrival in Washington. It describes the meeting with Polk in great detail, lays out the Ojibwe grievances, and importantly, records Polk’s reaction. I have not been able to find the name of the correspondent, but this article is easily the best-reported of all the many, many newspaper accounts of the 1848-49 delegation–most of which use patronizing racist language and focus on the more trivial, “fish out of water” element of Lake Superior chiefs in the capital city.

New York Daily Tribune, 6 February 1849, Page 1

The Indians of the North-West–Their Wrongs–Chiefs in Washington

Correspondence of The Tribune

WASHINGTON, 3d Feb 1849.

Yesterday (Friday) the Chiefs representing the Chippewa Tribe of Indians located on the borders of Lake Superior and drawing their pay at La Pointe, representing 16 bands, which comprise about 9,000 Indians, after remaining here for the last ten days, were presented to the President.– The Secretary of War and Commissioner of Indian Affairs were also present. One of the Chiefs who appeared to be the eldest, first addressed the President, for a period of twenty minutes. The address was interpreted by John B. Martell, a half-breed, who was born and has always continued among them. He appears a shrewd, sensible man, and interprets with much fluency. This Chief was followed by two others in addresses occupying the same length of time. They all addressed the President as “Our Great Father,” and spoke with much energy, dignity and fluency, preserving throughout a respectful manner and evincing an earnest sincerity of purpose, that bespoke their mission to be one of no ordinary character. They represented their grievances under which their tribes were laboring: the trials and privations they had undergone to reach here, and the separation from their families, with much emotion and in truly touching and eloquent terms.

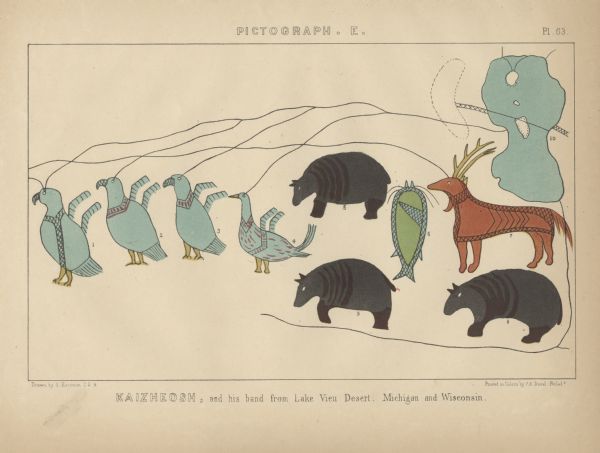

The oldest chief was Gezhiiyaash (his pictographic petition above) or “Swift Sailor” from Lac Vieux Desert. The two other chiefs were likely Oshkaabewis “Messenger” from Wisconsin River, and Naagaanab “Foremost Sitter” from Fond du Lac.

They represented that their annuities under their Treaty of La Pointe, made about the year 1843, were payable in the month of July in each year and not later, because by that time the planting season would be over; beside, it would be the best time and the least dangerous to pass the Great Lake and return to their homes in time to gather wild rice, on which they mainly depended during the hard winters. The first payment was made later than the time agreed upon. The agent, upon being notified, promised to comply with the terms of the Treaty, but every year since the payments have been made later, and that of last year did not take place until about the middle of October, in consequence of which they have been subjected to much suffering.– They assemble at the place for payment designated in the treaty. It is then the traders take advantage of them–being three hundred miles from home, without money, and without provisions; and when their money is received it must all be paid for their subsistence during the long delay they have been subjected to; and sickness frequently breaks out among them from being obliged to use salt provisions, which they are not accustomed to. By leaving their homes at any other time than in the month of July they neglect their harvesting–rice and potato crops, and if they neglect those they must starve to death; therefore it would be better for them to lose their annuities altogether. And without their blankets, procured at the Pointe, they are liable to freeze to death when passing the stormy lake; and the tradespeople influence the Agent to send for them a month before the payment is made, and when they arrive the Agent accepts orders from them for provisions which they are obliged to purchase at a great price–one dollar for 15 lbs of flour, and in proportion for other articles. They have assembled frequently in regard to these things, and can only conclude that their complaints have never reached their “Great Father,” and they have now come to see him in person, and take him by the hand.

In regard to the Half-Breeds at La Pointe, who draw pay with them, they say: That in the Treaty concluded between Governor Dodge and the Chippewas at St. Peters, provision was made for the half-breeds to draw their share all in one payment, and it was paid them accordingly, $258.50 each, which was a mere gift on the part of the tribe; a payment which they had no right to, but was given them as a present. Induced by some subsequent representations by the half-breeds, they were taken into their pay list, and the consequence has been that almost all the half breeds, as well as the French who are married to Indian women, are in the employ of, or dependent upon one of the principal trading houses, (Dr. Bourop’s) at La Pointe, with whom their goods and provisions are stored; and that they are thus enabled to select and appropriate to themselves the choice portion of all the goods designed for them–in many cases not leaving them a blanket to start with upon their journey of two or three hundred miles distant to their homes. After many other details, to which we will make reference in future articles, they urged that owing to the faithlessness of the half-breeds to them, and to the Government, that they be stricken from the pay list.

One half the goods furnished are of no use to them. The articles they most need are guns, kettles, blankets and a greater supply of provisions, &c.

They are under heavy expense, and no money to pay their board. They have undertaken this long journey for the benefit of their whole people, and at their earnest solicitations. They have been absent from their families nearly one year. It has cost them $1,400 to get here. Half of that sum has been raised from exhibitions. The other half has been borrowed from kind people on the route they have traveled. They wish to repay the money advanced them and to procure money to return home with. They want clothes and things to take to their families, and ask an appropriation of $6,000 on their annuity money.

They have before made a communication to the President, to be laid before the present Congress, for the acquisition of lands and the naturalization of their bands–propositions which they urged with great force.

All the Chiefs represented to the President that their interpreter, Mr. Martel, was living in very comfortable circumstances at home, and was induced to accompany them by the urgent solicitations of all their people who confided in his integrity and looked upon him as their friend.

The paternalistic ritual kinship (“Great Father”) language used here by James K. Polk, can be off-putting to the modern reader. However, it had a long tradition in Ojibwe “fur trade theater” rhetoric. Gezhiiyaash was no meek schoolboy, as evidenced by his words in this document (White House)

Their supplicating–though forcible, intelligent, and pathetic appeal, to be permitted to live upon the spot of their nativity, where the morning and noon of their days had been past, and the night time of their existence has reached them, was, too, and irresistible appeal to the justice, generosity and magnanimity of that boasted “civilization” that pleads mercy to the conquered, and was calculated to leave an impress upon every honest heart who claims to be a “freeman.”

The President, in answer to the several addresses, requested the interpreter to state to them that their Great Father was happy to have met with them; and as they had made allusion to written documents which they placed in his hands, as containing an expression of their views and wishes, he would carefully read them and communicate his answer to the Secretary of War and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, assuring them of kindly feelings on the part of the Government, and terminating with some expressions very like a schoolmaster’s enjoinder upon his scholars that if they behaved themselves they might expect good treatment in future.

The fact that they met Polk was not new information, but we hadn’t been previously aware of just how long the meeting went. It is important to note the president’s use of “kindly feelings” and “behaved themselves.” Those phrases would come up frequently in subsequent years.

One could argue that Polk was a lame duck, and would be dead of cholera within a few months, so his words didn’t mean much. One could argue the problem was that the Ojibwe didn’t understand that in the American political system–that the incoming Whig administration might not feel bound by the words and “kindly feelings” of the outgoing Democratic administration.

However, the next document shows that the chiefs did feel the need to cover their bases and stuck around Washington long enough meet the next president. To us, at least, this was new information:

National Era v. III. No. 14, pg. 56 April 5, 1849

For the National Era

THE CHIPPEWA CHIEFS AND GENERAL TAYLOR

On the third day after the arrival of General Taylor at Washington, the Indian chiefs requested me to seek an interview for them, as they were about to leave for their homes, on Lake Superior, and greatly desired to see the new President before their departure.

It was accordingly arranged by the General to see them the next morning at 9 o’clock, before the usual reception hour.

Fitted out in their very best, with many items of finery which their taste for the imposing had added to their wardrobe, the delegation and their interpreter accompanied me to the reception room, and were cordially taken by the hand by the plain but benevolent-looking old General. One of the chiefs arose, and addressed the President elect nearly as follows:

“Father! We are glad to see you, and we are pleased to see you so well after your long journey.

“Father! We are the representatives of about twenty thousand of your red children, and are just about leaving for our homes, far off on Lake Superior, and we are very much gratified, that, before our departure, we have the opportunity of shaking hands with you.

“Father! You have conquered your country’s enemies in war; may you subdue the enemies of your Administration while you are President of the United States and govern this great country, like the great father, Washington, before you, with wisdom and in peace.

“Father! This our visit through the country and to the cities of your white children, and the wonderful things that we have seen, impress us with awe, and cause us to think that the white man is the favored of the Great Spirit.

“Father! In the midst of the great blessings with which you and your white children are favored of the Great Spirit, we ask of you, while you are in power, not to forget your less fortunate red children. They are now few, and scattered, and poor. You can help them.

“Father! Although a successful warrior, we have heard of your humanity! And now that we see you face to face, we are satisfied that you have a heart to feel for your poor red children.

“Father Farewell”

The tall, manly-looking chief having finished and shaken hands, General Taylor asked him to be seated, and, rising himself, replied nearly as follows”

“My Red Children: I am very happy to have this interview with you. What you have said I have listened to with interest. It is the more appreciated by me, as I am no stranger to your people. I resided for a length of time on your borders, and have been witness to your privations, and am acquainted with many of your wants.

“Peace must be established and maintained between yourselves and the neighboring tribes of the red men, and you need in the next place the means of subsistence.

“My Red Children: I thank you for your kind wishes for me personally, and as President of the United States.

“While I am in office, I shall use my influence to keep you at peace with the Sioux, between whom and the Chippewas there has always been a most deadly hostility, fatal to the prosperity of both nations. I shall also recommend that you be provided with the means of raising corn and the other necessaries of life.

“My Red Children: I hope that you have met with success in your present visit, and that you may return to your homes without an accident by the way; and I bid you say to your red brethren that I cordially wish them health and prosperity. Farewell.”

This interesting interview closed with a general shaking of hands and during the addresses, it is creditable to the parties to say, that the feelings were reached. Tears glistened in the eyes of the Indians and General Taylor evinced sufficient emotion, during the address of the chief, to show that he possesses a heart that may be touched. The old veteran was heard to remark, as the delegation left the room, “What fine looking men they are!”

Major Martell, the half-breed interpreter, acquitted himself handsomely throughout. The Indians came away declaring that “General Taylor talked very good.”

The General’s family and suite, evidently not prepared for the visit; were not dressed to receive company at so early an hour; nevertheless, they soon came in, en dishabille, and looked on with interest.

P.

One of the lingering questions I’ve had about the 1848-49 Delegation has been whether or not the Ojibwe leadership viewed it as a success. This document shows that the answer was unequivocally yes. It also shows why the chiefs felt so blindsided and disbelieving in the spring of 1850 when the government agents at La Pointe told them that Taylor had ordered them to remove. They didn’t have to go back to 1842 for the Government’s promises. They had heard them only a year earlier from both the president and the president-elect!

It also explains why during and after the removal, the chiefs number-one priority was sending another delegation. One would eventually go in 1852, led by Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. This would help secure the reservations sought by the first delegation, but that was only after two failed removal attempts and hundreds of deaths.

If the cholera epidemic had not come, Chief Buffalo and other prominent chiefs, would have likely gone back to Taylor in the winter of 1849-50. They may have been able to secure new treaty negotiations, reservations on the ceded territory, or at the very least have been more prepared for the upcoming removal:

George Johnston to Henry Schoolcraft, 5 October 1849, MS Papers of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft: General Correspondence, 1806-1864, BOX 51.

Saut Ste Maries

Oct 5th 1849

My Dear sir,

Your favor of Sep. 14th, I have just now received and will lose no time in answering. Since I wrote to you on the subject of an intended delegation of Chippewa Chiefs desiring to visit the seat of Govt., I visited Lapointe and remained there during the payment, and I had an opportunity of seeing & talking with the chiefs. They held a council with their agent Dr. Livermore and expressed their desire to visit Washington this season, and they laid the matter before him with open frankness, and Dr. Livermore answered them in the same strain, advising them at the same time, to relinquish their intended visit this year, as it would be dangerous for them, to travel in the midst of sickness which was so prevalent & so widely spread in the land, and that if they should still feel desirous to go on the following year that he would then permit them to do so, and that he would have no objections, this appearing so reasonable to the chiefs, that they assented to it.

I will write to the chiefs and express to them the subject of your letter, and direct them to address Mr. Babcock at Detroit.

You will herein find enclosed copy of Mr. Ballander’s letter to me, a gentleman of the Hon. Hudson’s Bay Co. & Chief factor at Fort Garry in the Red river region, it is very kind & his sympathy, devotes a feeling heart.– Mr. Mitchell of Green Bay to whom I have written in the early part of this summer, to make enquiries relative to certain reports of Tanner’s existence among the sioux, he has not as yet returned an answer to may communication and I feel the neglect with some degree of asperity which I cannot control.

Very Truly yours

Geo. Johnston

Henry R. Schoolcraft Esq.

Washington

It is hard to say how differently history may have turned out if a second delegation had been able to go with George Johnston. There is a good chance it would have been a lot more successful. Johnston was much more of an insider than Martell–who had had a lot of difficulty convincing the American authorities of his credentials. One of those who stood in Martell’s way was Henry Schoolcraft. Schoolcraft, was regarded by the American establishment as the foremost authority on Ojibwe affairs and was Johnston’s brother-in-law.

It may not have worked. The inertia of United States Indian Policy was still with removal. Any attempt to reverse Manifest Destiny and convince the government to cede land back to Indian nations east of the Mississippi was going to be an uphill battle. The Minnesota trade interests were strong.

Also, Schoolcraft was a Democrat, so he would have had less influence with the Whig Taylor–though agreements on Western issues sometimes crossed party lines. However, one can imagine George Johnston sitting around a table in Washington with his “Uncle” Buffalo, his brother-in-law Schoolcraft, and the U.S. President, working out the contours of a new treaty avoiding the removal entirely. Because of the cholera, however, we’ll never know.

For more on how the fallout from the Mexican War impacted Ojibwe removal, see Slavery, Debt Default, and the Sandy Lake Tragedy

For more on the 1848-49 Delegation, see: this post, this post, and this post

The Removal Order of 1849

March 12, 2016

By Amorin Mello

United States. Works Progress Administration:

Chippewa Indian Historical Project Records 1936-1942

(Northland Micro 5; Micro 532)

12th President Zachary Taylor gave the 1849 Removal Order while he was still in office. During 1852, Chief Buffalo and his delegation met 13th President Millard Fillmore in Washington, D.C., to petition against this Removal Order.

~ 1848 presidential campaign poster from the Library of Congress

Reel 1; Envelop 1; Item 14.

The Removal Order of 1849

By Jerome Arbuckle

After the war of 1812 the westward advance of the people of the United States of was renewed with vigor. These pioneers were imbued with the idea that the possessions of the Indian tribes, with whom they came in contact, were for their convenience and theirs for the taking. Any attempt on the part of the aboriginal owners to defend their ancestral homes were a signal for a declaration of war, or a punitive expedition, which invariably resulted in the defeat of the Indians.

“Peace Treaties,” incorporating terms and stipulations suitable particularly to the white man’s government, were then negotiated, whereby the Indians ceded their lands, and the remnants of the dispossessed tribe moved westward. The tribes to the south of the Great Lakes, along the Ohio Valley, were the greatest sufferers from this system of acquisition.

Another system used with equal, if less sanguinary success, was the “treaty system.” Treaties of this type were actually little more than receipt signed by the Indian, which acknowledged the cessions of huge tracts of land. The language of the treaties, in some instances, is so plainly a scheme for the dispossession and removal of the Indians that it is doubtful if the signers for the Indians understood the true import of the document. Possibly, and according to the statements handed down from the Indians of earlier days to the present, Indians who signed the treaties were duped and were the victims of treachery and collusion.

By the terms of the Treaties of 1837 and 1842, the Indians ceded to the Government all their territory lying east of the Mississippi embracing the St. Croix district and eastward to the Chocolate River. The Indians, however, were ignorant of the fact that they had ceded these lands. According to the terms, as understood by them, they were permitted to remain within these treaty boundaries and continue to enjoy the privileges of hunting, fishing, ricing and the making of maple sugar, provided they did not molest their white neighbors; but they clearly understood that the Government was to have the right to use the timber and minerals on these lands.

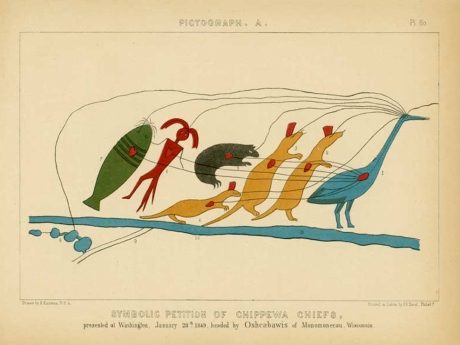

Entitled “Chief Buffalo’s Petition to the President“ by the Wisconsin Historical Society, the story behind this now famous symbolic petition is actually unrelated to Chief Buffalo from La Pointe, and was created before the Sandy Lake Tragedy. It is a common error to mis-attribute this to Chief Buffalo’s trip to Washington D.C., which occurred after that Tragedy. See Chequamegon History’s original post for more information.

Detail of Benjamin Armstrong from a photograph by Matthew Brady (Minnesota Historical Society). See our Armstrong Engravings post for more information.

Their eyes were opened when the Removal Order of 1849 came like a bolt from the blue. This order cancelled the Indians’ right to hunt and fish in the territory ceded, and gave notification for their removal westward. According to Verwyst, the Franciscan Missionary, many left by reason of this order, and sought a refuge among the westernmost of their tribe who dwelt in Minnesota.

Many of the full bloods, who naturally had a deep attachment for their home soil, refused to budge. The chiefs who signed the treaty were included in this action. They then concluded that they were duped by the Treaty Commissioners and were given a faulty interpretation of the treaty passages. Although the Chippewa realized the futility of armed resistance, those who chose to remain unanimously decided to fight it out. A few white men who were true friends of the Indians, among these was Ben Armstrong, the adopted son of the Head Chief, Buffalo, and he cautioned the Indians against any show of hostility.

At a council, Armstrong prevailed upon the chiefs to make a trip to Washington. Accordingly, preparations for the trip were made, a canoe of special make being constructed for the journey. After cautioning the tribesmen to remain calm, pending their return, they set out for Washington in April, 1852. The party was composed of Buffalo, the head Chief, and several sub-chiefs, one of whom was Oshoga, who later became a noted man among the Chippewa. Armstrong was the interpreter and director of the party. The delegation left La Pointe and proceeded by way of the Great Lakes as far as Buffalo, N. Y., and then by rail to Washington. They stopped at the white settlements along the route and their leader, Mr. Armstrong, circulated a petition among the white people. This petition, which was to be presented to the President, urged that the Chippewa be permitted to remain in their own country and the Removal Order reconsidered. Many signatures were obtained, some of the signers being acquaintances of the President, whose signatures he later recognized.

Despite repeated attempts of arbitrary agents, who were employed by the government to administer Indian affairs, and who endeavored to return them back or discourage the trip, they resolutely persisted. The party arrived at Buffalo, New York, practically penniless. By disposing of some Indian trinkets, and by putting the chief on exhibition, they managed to acquire enough money to defray their expenses until they finally arrived at Washington.

Here it seemed their troubles were to begin. They were refused an audience with those persons who might have been able to assist them. Through the kind assistance of Senator Briggs of New York, they eventually managed to arrange for an interview with President Fillmore.

United States Representative George Briggs was helpful in getting an audience with President Millard Fillmore.

~ Library of Congress

At the appointed time they assembled for the interview and after smoking the peace pipe offered by Chief Buffalo, the “Great White Father” listened to their story of conditions in the Northwest. Their petition was presented and read and the meeting adjourned. President Fillmore, deeply impressed by his visitors, directed that their expenses should be paid by the Government and that they should have the freedom of the city for a week.

![Vincent Roy, Jr., portrait from "Short biographical sketch of Vincent Roy, [Jr.,]" in Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, by Chrysostom Verwyst, 1900, pages 472-476.](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/vincent-roy-jr.jpg?w=219&h=300)

Vincent Roy, Jr., was also on this famous trip to Washington, D.C. For more information, see this excerpt from Vincent Roy Jr’s biography.

Their mission was accomplished and all were happy. They had achieved what they sought. An uprising of their people had been averted in which thousands of human lives might have been cruelly slaughtered; so with light hearts they prepared for their homeward trip. Their fare was paid and they returned by rail by way of St. Paul, Minnesota, which was as near as they could get by rail to their homes. From St. Paul they traveled overland, a distance of over two hundred miles, overland. Along the route they frequently met with bands of Chippewa, whom they delighted with the information of the successes of their trip. These groups they instructed to repair to Madeline Island for the treaty at the time stipulated.

Upon their arrival at their own homes, the successes of the delegation was hailed with joy. Runners were dispatched to notify the entire Chippewa nation. As a consequence, many who had left their homes in compliance with the Removal Order now returned.

When the time for the treaty drew near, the Chippewa began to arrive at the Island from all directions. Finally, after careful deliberations, the treaty of 1854 was concluded. This treaty provided for several reservations within the ceded territory. These were Ontonagon and L’Anse, in the present state of Michigan, Lac du Flambeau, Bad River or La Pointe, Red Cliff, and Lac Courte Oreille, in Wisconsin, and Fond du Lac and Grand Portage in Minnesota.

It was at this time that the Chippewa mutually agreed to separate into two divisions, making the Mississippi the dividing line between the Mississippi Chippewa and the Lake Superior Chippewa, and allowing each division the right to deal separately with the Government.

Reconstructing the “Martell” Delegation through Newspapers

November 2, 2013

Symbolic Petition of the Chippewa Chiefs: This pictographic petition was brought to Washington D.C. by a delegation of Ojibwe chiefs and their interpreter J.B. Martell. This one, representing the band of Chief Oshkaabewis, is the most famous, but their were several others copied from birch bark by Seth Eastman and published in the works of Henry Schoolcraft. For more, follow this link.

Henry Schoolcraft. William W. Warren. George Copway. These names are familiar to any scholar of mid-19th-century Ojibwe history. They are three of the most referenced historians of the era, and their works provide a great deal of historical material that is not available in any other written sources. Copway was Ojibwe, Warren was a mix-blood Ojibwe, and Schoolcraft was married to the granddaughter of the great Chequamegon chief Waabojiig, so each is seen, to some extent, as providing an insider’s point of view. This could lead one to conclude that when all three agree on something, it must be accurate. However, there is a danger in over-relying on these early historians in that we forget that they were often active participants in the history they recorded.

This point was made clear to me once again as I tried to sort out my lingering questions about the 1848-49 “Martell” Delegation to Washington. If you are a regular reader, you may remember that this delegation was the subject of the first post on this website. You may also remember from this post, that the group did not have money to get to Washington and had to reach out to the people they encountered along the way.

The goal of the Martell Delegation was to get the United States to cede back title to the lands surrounding the major Lake Superior Ojibwe villages. The Ojibwe had given this land up in the Treaty of 1842 with the guarantee that they could remain on it. However, by 1848 there were rumors of removal of all the bands east of the Mississippi to unceded land in Minnesota. That removal was eventually attempted, in 1850-51, in what is now called the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

The Martell Delegation remains a little-known part of the removal story, although the pictographs remain popular. Those petitions are remembered because they were published in Henry Schoolcrafts’ Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States (1851) along with the most accessible primary account of the delegation:

In the month of January, 1849, a delegation of eleven Chippewas, from Lake Superior, presented themselves at Washington, who, amid other matters not well digested in their minds, asked the government for a retrocession of some portion of the lands which the nation had formerly ceded to the United States, at a treaty concluded at Lapointe, in Lake Superior, in 1842. They were headed by Oshcabawiss, a chief from a part of the forest-country, called by them Monomonecau, on the head-waters of the River Wisconsin. Some minor chiefs accompanied them, together with a Sioux and two boisbrules, or half-breeds, from the Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The principal of the latter was a person called Martell, who appeared to be the master-spirit and prime mover of the visit, and of the motions of the entire party. His motives in originating and conducting the party, were questioned in letters and verbal representations from persons on the frontiers. He was freely pronounced an adventurer, and a person who had other objects to fulfil, of higher interest to himself than the advancement of the civilization and industry of the Indians. Yet these were the ostensible objects put forward, though it was known that he had exhibited the Indians in various parts of the Union for gain, and had set out with the purpose of carrying them, for the same object, to England. However this may be, much interest in, and sympathy for them, was excited. Officially, indeed, their object was blocked up. The party were not accredited by their local agent. They brought no letter from the acting Superintendent of Indian Affairs on that frontier. The journey had not been authorized in any manner by the department. It was, in fine, wholly voluntary, and the expenses of it had been defrayed, as already indicated, chiefly from contributions made by citizens on the way, and from the avails of their exhibitions in the towns through which they passed; in which, arrayed in their national costume, they exhibited their peculiar dances, and native implements of war and music. What was wanting, in addition to these sources, had been supplied by borrowing from individuals.

Martell, who acted as their conductor and interpreter, brought private letters from several persons to members of Congress and others, which procured respect. After a visit, protracted through seven or eight weeks, an act was passed by Congress to defray the expenses of the party, including the repayment of the sums borrowed of citizens, and sufficient to carry them back, with every requisite comfort, to their homes in the north-west. While in Washington, the presence of the party at private houses, at levees, and places of public resort, and at the halls of Congress, attracted much interest; and this was not a little heightened by their aptness in the native ceremonies, dancing, and their orderly conduct and easy manners, united to the attraction of their neat and well-preserved costume, which helped forward the object of their mission.

The visit, although it has been stated, from respectable sources, to have had its origin wholly in private motives, in the carrying out of which the natives were made to play the part of mere subordinates, was concluded in a manner which reflects the highest credit on the liberal feelings and sentiments of Congress. The plan of retrocession of territory, on which some of the natives expressed a wish to settle and adopt the modes of civilized life, appeared to want the sanction of the several states in which the lands asked for lie. No action upon it could therefore be well had, until the legislatures of these states could be consulted (pg. 414-416, pictographic plates follow).

I have always had trouble with Schoolcraft’s interpretation of these events. It wasn’t that I had evidence to contradict his argument, but rather that I had a hard time believing that all these chiefs would make so weighty a decision as to go to Washington simply because their interpreter was trying to get rich. The petitions asked for a permanent homeland in the traditional villages east of the Mississippi. This was the major political goal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe leadership at that time and would remain so in all the years leading up to 1854. Furthermore, chiefs continued to ask for, or go “uninvited” on, diplomatic missions to the president in the years that followed.

I explored some of this in the post about the pictograph, but a number of lingering questions remained:

What route did this group take to Washington?

Who was Major John Baptiste Martell?

Did he manipulate the chiefs into working for him, or was he working for them?

Was the Naaganab who went with this group the well-known Fond du Lac chief or the warrior from Lake Chetek with the same name?

Did any chiefs from the La Pointe band go?

Why was Martell criticized so much? Did he steal the money?

What became of Martell after the expedition?

How did the “Martell Expedition” of 1848-49 impact the Ojibwe removal of 1850-51?

Lacking access to the really good archives on this subject, I decided to focus on newspapers, and since this expedition received so much attention and publicity, this was a good choice. Enjoy:

Indiana Palladium. Vevay, IN. Dec. 2, 1848

Capt. Seth Eastman of the U.S. Army took note of the delegation as it traveled down the Mississippi from Fort Snelling to St. Louis. Eastman, a famous painter of American Indians, copied the birch bark petitions for publication in the works of his collaborator Henry Schoolcraft. At least one St. Louis paper also noticed these unique pictographic documents.

Lafayette Courier. Lafayette, IN. Dec. 8, 1848.

Lafayette Courier. Lafayette, IN. Dec. 8, 1848.

The delegation made its way up the Ohio River to Cincinnati, where Gezhiiyaash’s illness led to a chance encounter with some Ohio Freemasons. I won’t repeat it here, but I covered this unusual story in this post from August.

At Cincinnati, they left the river and headed toward Columbus. Just east of that city, on the way to Pittsburgh, one of the Ojibwe men offered some sound advice to the women of Hartford, Ohio, but he received only ridicule in return.

Madison Weekly Courier. Madison, IN. Jan. 24, 1849

It’s unclear how quickly reports of the delegation came back to the Lake Superior country. William Warren’s letter to his cousin George, written in March after the delegation had already left Washington, still spoke of St. Louis:

William W. Warren (Wikimedia Images)

“…About Martells Chiefs. They were according to last accounts dancing the pipe dance at St. Louis. They have been making monkeys of themselves to fill the pockets of some cute Yankee who has got hold of them. Black bird returned from Cleveland where he caught scarlet fever and clap. He has behaved uncommon well since his return…” (Schenck, pg. 49)

From this letter, we learn that Blackbird, the La Pointe chief, was originally part of the group. In evaluating Warren’s critical tone, we must remember that he was working closely with the very government officials who withheld their permission. Of the La Pointe chiefs, Blackbird was probably the least accepting of American colonial power. However, we see in the obituary of Naaganab, Blackbird’s rival at the 1855 annuity payment, that the Fond du Lac chief was also there.

New York World. New York. July 22, 1894

Before finding this obituary, I had thought that the Naaganab who signed the petition was more likely the headman from Lake Chetek. Instead, this information suggests it was the more famous Fond du Lac chief. This matters because in 1848, Naaganab was considered the speaker for his cousin Zhingob, the leading chief at Fond du Lac. Blackbird, according to his son James, was the pipe carrier for Buffalo. While these chiefs had their differences with each other, it seems likely that they were representing their bands in an official capacity. This means that the support for this delegation was not only from “minor chiefs” as Schoolcraft described them, or “Martells Chiefs” as Warren did, from Lac du Flambeau and Michigan. I would argue that the presence of Blackbird and Naaganab suggests widespread support from the Lake Superior bands. I would guess that there was much discussion of the merits of a Washington delegation by Buffalo and others during the summer of 1848, and that the trip being a hasty money-making scheme by Martell seems much less likely.

Madison Daily Banner. Madison, IN. Jan. 3, 1849.

From Pittsburgh, the delegation made it to Philadelphia, and finally Washington. They attracted a lot of attention in the nation’s capital. Some of their adventures and trials: Oshkaabewis and his wife Pammawaygeonenoqua losing an infant child, the group hunting rabbits along the Potomac, and the chiefs taking over Congress, are included this post from March, so they aren’t repeated here.

Adams Sentinel. Gettysburg, PA. Feb. 5, 1849.

According to Ronald Satz, the delegation was received by both Congress and President Polk with “kindly feelings” and the expectation of “good treatment in the future” if they “behaved themselves (Satz 51).” Their petition was added to the Congressional Record, but the reservations were not granted at the time. However, Congress did take up the issue of paying for the debts accrued by the Ojibwe along the way.

George Copway (Wikimedia Commons)

Kah-Ge-Ga-Gah-Bowh (George Copway), a Mississauga Ojibwe and Methodist missionary, was the person “belonging to one of the Canada Bands of Chippewas,” who wrote the anti-Martell letter to Indian Commissioner William Medill. This is most likely the letter Schoolcraft referred to in 1851. In addition to being upset about the drinking, Copway was against reservations in Wisconsin. He wanted the government to create a huge pan-Indian colony at the headwaters of the Missouri River.

William Medill (Wikimedia Commons)

Iowa State Gazette. Burlington, IA. April 4, 1849

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Feb. 28, 1849.

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Feb. 28, 1849.

With $6000 (or did they only get $5000?), a substantial sum for the antebellum Federal Government, the group prepared to head back west with the ability to pay back their creditors.

It appears the chiefs returned to their villages by going back though the Great Lakes to Green Bay and then overland.

The Chippewa Delegation, who have been on a visit to see their “great fathers” in Washington, passed through this place on Saturday last, on their way to their homes near Lake Superior. From the accounts of the newspapers, they have been lionized during their whole journey, and particularly in Washington, where many presents were made them, among the most substantial of which was six boxed of silver ($6,000) to pay their expenses. They were loaded with presents, and we noticed one with a modern style trunk strapped to his back. They all looked well and in good spirits (qtd. in Paap, pg. 205).

Green Bay Gazette. April 4, 1849

So, it hardly seems that the Ojibwe chiefs returned to their villages feeling ripped off by their interpreter. Martell himself returned to the Soo, and found a community about to be ravaged by a epidemic of cholera.

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Sep. 5, 1849.

Martell appears in the 1850 census on the record of those deceased in the past year. Whether he was a major in the Mexican War, whether he was in the United States or Canadian military, or whether it was even a real title, remains a mystery. His death record lists his birthplace as Minnesota, which probably connects him to the Martells of Red Lake and Red River, but little else is known about his early years. And while we can’t say for certain whether he led the group purely out of self-interest, or whether he genuinely supported the cause, John Baptiste Martell must be remembered as a key figure in the struggle for a permanent Ojibwe homeland in Wisconsin and Michigan. He didn’t live to see his fortieth birthday, but he made the 1848-49 Washington delegation possible.

So how do we sort all this out?

To refresh, my unanswered questions from the other posts about this delegation were:

1) What route did this group take to Washington?

2) Who was Major John Baptiste Martell?

3) Did he manipulate the chiefs into working for him, or was he working for them?

4) Was the Naaganab who went with this group the well-known Fond du Lac chief or the warrior from Lake Chetek with the same name?

5) Did any chiefs from the La Pointe band go?

6) Why was Martell criticized so much? Did he steal the money?

7) What became of Martell after the expedition?

8) How did the “Martell Expedition” of 1848-49 impact the Ojibwe removal of 1850-51?

We’ll start with the easiest and work our way to the hardest. We know that the primary route to Washington was down the Brule, St. Croix, and Mississippi to St. Louis, and from there up the Ohio. The return trip appears to have been via the Great Lakes.

We still don’t know how Martell became a major, but we do know what became of him after the diplomatic mission. He didn’t survive to see the end of 1849.

The Fond du Lac chief Naaganab, and the La Pointe chief Blackbird, were part of the group. This indicates that a wide swath of the Lake Superior Ojibwe leadership supported the delegation, and casts serious doubt on the notion that it was a few minor chiefs in Michigan manipulated by Martell.

Until further evidence surfaces, there is no reason to support Schoolcraft’s accusations toward Martell. Even though these allegations are seemingly validated by Warren and Copway, we need to remember how these three men fit into the story. Schoolcraft had moved to Washington D.C. by this point and was no longer Ojibwe agent, but he obviously supported the power of the Indian agents and favored the assimilation of his mother-in-law’s people. Copway and Warren also worked closely with the Government, and both supported removal as a way to separate the Ojibwe from the destructive influences of the encroaching white population. These views were completely opposed to what the chiefs were asking for: permanent reservations at the traditional villages. Because of this, we need to consider that Schoolcraft, Warren, and Copway would be negatively biased toward this group and its interpreter.

Finally there’s the question Howard Paap raises in Red Cliff, Wisconsin. How did this delegation impact the political developments of the early 1850s? In one sense the chiefs were clearly pleased with the results of the trip. They made many friends in Congress, in the media, and in several American cities. They came home smiling with gifts and money to spread to their people. However, they didn’t obtain their primary goal: reservations east of the Mississippi, and for this reason, the following statement in Schoolcraft’s account stands out:

The plan of retrocession of territory, on which some of the natives expressed a wish to settle and adopt the modes of civilized life, appeared to want the sanction of the several states in which the lands asked for lie. No action upon it could therefore be well had, until the legislatures of these states could be consulted.

“Kindly feelings” from President Polk didn’t mean much when Zachary Taylor and a new Whig administration were on the way in. Meanwhile, Congress and the media were so wrapped up in the national debate over slavery that they forgot all about the concerns of the Ojibwes of Lake Superior. This allowed a handful of Indian Department officials, corrupt traders, and a crooked, incompetent Minnesota Territorial governor named Alexander Ramsey to force a removal in 1850 that resulted in the deaths of 400 Ojibwe people in the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

It is hard to know how the chiefs felt about their 1848-49 diplomatic mission after Sandy Lake. Certainly their must have been a strong sense that they were betrayed and abandoned by a Government that had indicated it would support them, but the idea of bypassing the agents and territorial officials and going directly to the seat of government remained strong. Another, much more famous, “uninvited” delegation brought Buffalo and Oshogay to Washington in 1852, and ultimately the Federal Government did step in to grant the Ojibwe the reservations. Almost all of the chiefs who made the journey, or were shown in the pictographs, signed the Treaty of 1854 that made them.

Sources:

McClurken, James M., and Charles E. Cleland. Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights / James M. McClurken, Compiler ; with Charles E. Cleland … [et Al.]. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State UP, 2000. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Seth Eastman. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Collected and Prepared under the Direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per Act of Congress of March 3rd, 1847. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo, 1851. Print.