CAUTION: This translation was made using Google Translate by someone who neither speaks nor reads German. It should not be considered accurate by scholarly standards.

Americans love travelogues. From de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, to Twain’s Roughing It, to Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley, a few pages of a well-written travelogue by a random interloper can often help a reader picture a distant society more clearly than volumes of documents produced by actual members of the community. And while travel writers often misinterpret what they see, their works remain popular long into the future. When you think about it, this isn’t surprising. The genre is built on helping unfamiliar readers interpret a place that is different, whether by space or time, from the one they inhabit. The travel writer explains everything in a nice summary and doesn’t assume the reader knows the subject.

You can imagine, then, my excitement when I accidentally stumbled upon a largely-unknown and untranslated travelogue from 1852 that devotes several pages to to the greater Chequamegon region.

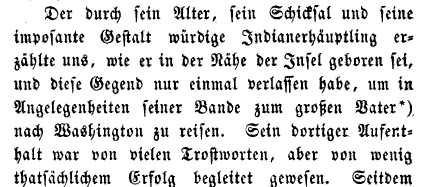

I was playing around on Google Books looking for variants of Chief Buffalo’s name from sources in the 1850s. Those of you who read regularly know that the 1850s were a decade of massive change in this area, and the subject of many of my posts. I was surprised to see one of the results come back in German. The passage clearly included the words Old Buffalo, Pezhickee, La Pointe, and Chippewa, but otherwise, nothing. I don’t speak any German, and I couldn’t decipher all the letters of the old German font.

Karl (Carl) Ritter von Scherzer (1821-1903) (Wikimedia Images)

The book was Reisen in Nordamerika in den Jahren 1852 und 1853 (Travels in North America in the years 1852 and 1853) by the Austrian travel writers Dr. Moritz Wagner and Dr. Carl Scherzer. These two men traveled throughout the world in the mid 19th-century and became well-known figures in Europe as writers, government officials, and scientists. In America, however, Reisen in Nordamerika never caught on. It rests in a handful of libraries, but as far as I can find, it has never been translated into English.

Chapter 21, From Ontonagon to the Mouth of the Bois-brule River, was the chapter I was most interested in. Over the course of a couple of weeks, I plugged paragraphs into Google Translate, about 50 pages worth.

Here is the result (with the caveat that it was e-translated, and I don’t actually know German). Normally I clog up my posts with analysis, but I prefer to let this one stand on its own. Enjoy:

XXI

From Ontonagon to the mouth of the Bois-brule River–Canoe ride to Magdalen Island–Porcupine Mountains–Camping in the open air–A dangerous canoe landing at night–A hospitable Jewish family–The island of La Pointe–The American Fur Company–The voyageurs or courriers de bois–Old Buffalo, the 90 year-old Chippewa chief–A schoolhouse and an examination–The Austrian Franciscan monk–Sunday mass and reflections on the Catholic missions–Continuing the journey by sail–Nous sommes degrades–A canoeman and apostle of temperance–Fond du lac–Sauvons-nous!

On September 15th, we were under a cloudless sky with the thermometer showing 37°F. In a birch canoe, we set out for Magdalene Island (La Pointe). Our intention was to drive up the great Lake Superior to its western end, then up the St. Louis and Savannah Rivers, to Sandy Lake on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. Our crew consisted of a young Frenchman of noble birth and education and a captain of the U.S. Navy. Four French Canadians were the leaders of the canoes. Their trustworthy, cheerful, sprightly, and fearless natures carried us so bravely against the thundering waves, that they probably could have even rowed us across the river Styx.

Upon embarkation, an argument broke out between passengers and crew over the issue of overloading the boat. It was only conditioned to hold our many pieces of baggage and the provisions to be acquired along the way. However, our mercenary pilot produced several bags and packages, for which he could be well paid, by carrying them Madeline Island as freight.

Shortly after our exit, the weather hit us and a strong north wind obliged us to pull to shore and make Irish camp, after we had only covered four English miles to the Attacas (Cranberry) Rive,r one of the numerous mountain streams that pour into Lake Superior. We brought enough food from Ontonagon to provide for us for approximately 14 days of travel. The settlers of La Pointe, which is the last point on the lake where whites live, provided for themselves only scanty provisions. A heavy bag of ship’s biscuit was at the end of one canoe, and a second sack contained tea, sugar, flour, and some rice. A small basket contained our cooking and dining utensils.

The captain believed that all these supplies would be unecessary because the bush and fishing would provide us with the richest delicacies. But already in the next lunch hour, when we caught sight of no wild fowl, he said that we must prepare the rice. It was delicious with sugar. Dry wood was collected and a merry flickering fire prepared. An iron kettle hung from birch branches crossed akimbo, and the water soon boiled and evaporated. The sea air was fresh, and the sun shone brightly. The noise of the oncoming waves sounded like martial music to the unfinished ear, so we longed for the peaceful quiet lake. The shore was flat and sandy, but the main attraction of the scenery was in the gigantic forest trees and the richness of their leafy ornaments.

At a quarter to 3 o’clock, we left the bivouac as there was no more wind, and by 3 o’clock, with our camp still visible, the water became weaker and weaker and soon showed tree and cloud upon its smooth surface. We passed the Porcupine Mountains, a mountain range made of trapp geological formation. We observed that some years ago, a large number of inexperienced speculators sunk shafts and made a great number of investments in anticipation of a rich copper discovery. Now everything is destroyed and deserted and only the green arbor vitae remain on the steep trap rocks.

Our night was pretty and serene, so we went uninterrupted until 1 o’clock in the morning. Our experienced boatmen did not trust the deceptive smoothness of the lake, however, and they uttered repeated fears that storms would interrupt our trip. It happens quite often that people who travel in late autumn for pleasure or necessity from Ontonagon to Magdalene Island, 70 miles away, are by sea storms prevented from travelling that geographically-small route for as many as 6 or 8 days.

Used to the life of the Indians in the primeval forests, for whom even in places of civilization prefer the green carpet under the open sky to the soft rug and closed room, the elements could not dampen the emotion of the paddlers of the canoe or force out the pleasure of the chase.* But for Europeans, all sense of romantic adventure is gone when in such a forest for days without protection from the heavy rain and without shelter from the cold eeriness for his shivering limbs.

(*We were accompanied on our trip throughout the lakes of western Canada by half-Indians who had paternal European blood in their veins. Yet so often, a situation would allow us to spend a night inside rather than outdoors, but they always asked us to choose to Irish camp outside with the Indians, who lived at the various places. Although one spoke excellent English, and they were both drawn more to the great American race, they thought, felt, and spoke—Indian!)

It is amazing the carelessness with which the camp is set near the sparks of the crackling fire. An overwhelming calm is needed to prevent frequent accidents, or even loss of human life, from falling on the brands. As we were getting ready to continue our journey early in the morning, we found the front part of our tent riddled with a myriad of flickering sparks.

16 September (50° Fahrenheit)*) Black River, seven miles past Presque Isle. Gradually the shore area becomes rolling hills around Black River Mountain, which is about 100 feet in height. Frequently, immense masses of rock protrude along the banks and make a sudden landing impossible. This difficulty to reach shore, which can stretch for several miles long, is why a competent captain will only risk a daring canoe crossing on a fairly calm lake.

(*We checked the thermometer regularly every morning at 7 o’clock, and when travel conditions allowed it, at noon and evening.)

At Little Girl’s Point, a name linked to a romantic legend, we prepared lunch from the unfinished bread from the day before. We had rice, tea, and the remains of the bread we brought from a bakery in Ontonagon from our first days.

In the afternoon, we met at a distance a canoe with two Indians and a traveler going in an easterly direction. We got close enough to ask some short questions in telegraph style. We asked, “Where do you go? How is the water in the St. Louis and Savannah River?”

We were answered in the same brevity that they were from Crow Wing going to Ontonagon, and that the rivers were almost dried from a month-long lack of rain.

The last information was of utmost importance to us for it changed, all of a sudden, the fibers of our entire itinerary. With the state of the rivers, we would have to do most of the 300-mile long route on foot which neither the advanced season of the year, nor the sandy steppes invited. If we had been able to extend our trip, we could have visited Itasca Lake, the cradle of the Mississippi, where only a few historically-impressive researchers and travelers have passed near: Pike, Cass, Schoolcraft, Nicollet, and to our knowledge, no Austrian.

However, this was impossible considering our lack of necessary academic preparation and in consideration of the economy of our travel plan. We do not like the error, we would almost say vice, of so many travelers who rush in hasty discontent, supported by modern transport, through wonderful parts of creation without gaining any knowledge of the land’s physical history and the fate of its inhabitants.*

(*We were told here recently of such a German tourist who traveled through Mexico in only a fortnight– i.e. 6 days from Veracruz to the capital and 6 days back with only two days in the capital!)

While driving, the boatmen sang alternately. They were, for the most part, frivolous love songs and not of the least philological or ethnographic interest.

After 2 o’clock, we passed the rocks of the Montreal River. They run for about six miles with a long drag reaching up to an altitude of 100 feet. There are layers of shale and red sandstone, all of which run east to west. By weathering, they have obtained such a dyed-painting appearance, that you can see in their marbled colors something resembling a washed-out image.

The Montreal* is a major tributary of Lake Superior. About 300 steps up from where it empties into the lake, it forms a very pretty waterfall surrounded by an impressive pool. Rugged cliffs form the 80’ falls over a vertical sandstone layer and form a lovely valley. The width of the Montreal is 10’, and it also forms the border between the states of Michigan and Wisconsin.

(*Indian: Ka-wa’-si-gi-nong sepi, the white flowing falls.)

We stayed in this cute little bay for over an hour as our frail canoes had begun to take on a questionable amount of water as the result of some wicked stone wounds.

Up from Montreal River heading towards La Pointe, the earlier red sandstone formation starts again, and the rich shaded hills and rugged cliffs disappear suddenly. Around 6 o’clock, we rested for half an hour at the mouth of the Bad River of Lake Superior. We quickly prepared our evening snack as the possibility of reaching Magdalene Island that same night was still in contention.

Across from us, on the western shore of Bad River*, we saw Indians by a warm fire. One of the boatmen suspected they’d come back from catching fish, and he called in a loud voice across the river asking if they wanted to come over and sell us some. We took their response, and soon shy Indian women (squaws) appeared. Lacking a male, they dreaded to get involved in trading with Whites, and did not like the return we offered.

(*On Bad River, a Methodist Mission was founded in 1841. It consists of the missionary, his wife, and a female teacher. Their sphere of influence is limited to dispensing divine teaching only to those wandering tribes of Chippewa Indians that come here every year during the season of fishing, to divest the birch tree of its bark, and to build it into a shelter).

A part of our nightly trip was spent fantastically in blissful contemplation of the wonders above us and next to us. Night sent the cool fragrance of the forest to our lonely rocking boat, and the sky was studded with stars that sparkled through the green branches of the woods. Soon, luminous insects appeared on the tops of the trees in equally brilliant bouquets.

At 11 o’clock at night, we saw a magnificent aurora borealis, which left such a bright scent upon the dark blue sky. However, the theater soon changed scene, and a fierce south wind moved in incredibly fast. What had just been a quietly slumbering lake, as if inhabited by underwater ghosts, struck the alarm and suddenly tumultuous waves approached the boat. With the faster waves wanting to forestall the slower, a raging tumult arose resembling the dirt thrown up by great wagon wheels.

We were directly in the middle of that powerful watery surface, about one and one half miles from the mainland and from the nearest south bank of the island. It would have been of no advantage to reverse course as it required no more time to reach the island as to go back. At the outbreak of this dangerous storm, our boatmen were still determined to reach La Pointe.

But when several times the beating waves began to fill our boat from all sides with water, the situation became much more serious. As if to increase our misery, at almost the same moment a darkness concealed the sky and gloomy clouds veiled the stars and northern lights, and with them went our cheerful countenance.

Now singing, our boatmen spoke with anxious gestures and an unintelligible patois to our fellow traveler. The captain said jokingly, that they took counsel to see who should be thrown in the water first should the danger increase. We replied in a like manner that it was never our desire to be first and that we felt the captain should keep that honor. Fortunately, all our concern soon ended as we landed at La Pointe (Chegoimegon).

To be continued…

CAUTION: This translation was made using Google Translate by someone who neither speaks nor reads German. It should not be considered accurate by scholarly standards.

Oshogay

August 12, 2013

At the most recent count, Chief Buffalo is mentioned in over two-thirds of the posts here on Chequamegon History. That’s the most of anyone listed so far in the People Index. While there are more Buffalo posts on the way, I also want to draw attention to some of the lesser known leaders of the La Pointe Band. So, look for upcoming posts about Dagwagaane (Tagwagane), Mizay, Blackbird, Waabojiig, Andeg-wiiyas, and others. I want to start, however, with Oshogay, the young speaker who traveled to Washington with Buffalo in 1852 only to die the next year before the treaty he was seeking could be negotiated.

I debated whether to do this post, since I don’t know a lot about Oshogay. I don’t know for sure what his name means, so I don’t know how to spell or pronounce it correctly (in the sources you see Oshogay, O-sho-ga, Osh-a-ga, Oshaga, Ozhoge, etc.). In fact, I don’t even know how many people he is. There were at least four men with that name among the Lake Superior Ojibwe between 1800 and 1860, so much like with the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search, the key to getting Oshogay’s history right is dependent on separating his story from those who share his name.

In the end, I felt that challenge was worth a post in its own right, so here it is.

Getting Started

According to his gravestone, Oshogay was 51 when he died at La Pointe in 1853. That would put his birth around 1802. However, the Ojibwe did not track their birthdays in those days, so that should not be considered absolutely precise. He was considered a young man of the La Pointe Band at the time of his death. In my mind, the easiest way to sort out the information is going to be to lay it out chronologically. Here it goes:

1) Henry Schoolcraft, United States Indian Agent at Sault Ste. Marie, recorded the following on July 19, 1828:

Oshogay (the Osprey), solicited provisions to return home. This young man had been sent down to deliver a speech from his father, Kabamappa, of the river St. Croix, in which he regretted his inability to come in person. The father had first attracted my notice at the treaty of Prairie du Chien, and afterwards received a small medal, by my recommendation, from the Commissioners at Fond du Lac. He appeared to consider himself under obligations to renew the assurance of his friendship, and this, with the hope of receiving some presents, appeared to constitute the object of his son’s mission, who conducted himself with more modesty and timidity before me than prudence afterwards; for, by extending his visit to Drummond Island, where both he and his father were unknown, he got nothing, and forfeited the right to claim anything for himself on his return here.

I sent, however, in his charge, a present of goods of small amount, to be delivered to his father, who has not countenanced his foreign visit.

Oshogay is a “young man.” A birth year of 1802 would make him 26. He is part of Gaa-bimabi’s (Kabamappa’s) village in the upper St. Croix country.

2) In June of 1834, Edmund Ely and W. T. Boutwell, two missionaries, traveled from Fond du Lac (today’s Fond du Lac Reservation near Cloquet) down the St. Croix to Yellow Lake (near today’s Webster, WI) to meet with other missionaries. As they left Gaa-bimabi’s (Kabamappa’s) village near the head of the St. Croix and reached the Namekagon River on June 28th, they were looking for someone to guide them the rest of the way. An old Ojibwe man, who Boutwell had met before at La Pointe, and his son offered to help. The man fed the missionaries fish and hunted for them while they camped a full day at the mouth of the Namekagon since the 29th was a Sunday and they refused to travel on the Sabbath. On Monday the 30th, the reembarked, and Ely recorded in his journal:

The man, whose name is “Ozhoge,” and his son embarked with us about 1/2 past 9 °clk a.m. The old man in the bow and myself steering. We run the rapids safely. At half past one P. M. arrived at the mouth of Yellow River…

Ozhoge is an “old man” in 1834, so he couldn’t have been born in 1802. He is staying on the Namekagon River in the upper St. Croix country between Gaa-bimabi and the Yellow Lake Band. He had recently spent time at La Pointe.

3) Ely’s stay on the St. Croix that summer was brief. He was stationed at Fond du Lac until he eventually wore out his welcome there. In the 1840s, he would be stationed at Pokegama, lower on the St. Croix. During these years, he makes multiple references to a man named Ozhogens (a diminutive of Ozhoge). Ozhogens is always found above Yellow River on the upper St. Croix.

Ozhogens has a name that may imply someone older (possibly a father or other relative) lives nearby with the name Ozhoge. He seems to live in the upper St. Croix country. A birth year of 1802 would put him in his forties, which is plausible.

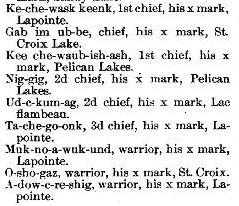

Ke-che-wask keenk (Gichi-weshki) is Chief Buffalo. Gab-im-ub-be (Gaa-bimabi) was the chief Schoolcraft identified as the father of Oshogay. Ja-che-go-onk was a son of Chief Buffalo.

4) On August 2, 1847, the United States and the Mississippi and Lake Superior Ojibwe concluded a treaty at Fond du Lac. The US Government wanted Ojibwe land along the nation’s border with the Dakota Sioux, so it could remove the Ho-Chunk people from Wisconsin to Minnesota.

Among the signatures, we find O-sho-gaz, a warrior from St. Croix. This would seem to be the Ozhogens we meet in Ely.

Here O-sho-gaz is clearly identified as being from St. Croix. His identification as a warrior would probably indicate that he is a relatively young man. The fact that his signature is squeezed in the middle of the names of members of the La Pointe Band may or may not be significant. The signatures on the 1847 Treaty are not officially grouped by band, but they tend to cluster as such.

5) In 1848 and 1849 George P. Warren operated the fur post at Chippewa Falls and kept a log that has been transcribed and digitized by the University of Wisconsin Eau Claire. He makes several transactions with a man named Oshogay, and at one point seems to have him employed in his business. His age isn’t indicated, but the amount of furs he brings in suggests that he is the head of a small band or large family. There were multiple Ojibwe villages on the Chippewa River at that time, including at Rice Lake and Lake Shatac (Chetek). The United States Government treated with them as satellite villages of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band.

Based on where he lives, this Oshogay might not be the same person as the one described above.

6) In December 1850, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in the case Oshoga vs. The State of Wisconsin, that there were a number of irregularities in the trial that convicted “Oshoga, an Indian of the Chippewa Nation” of murder. The court reversed the decision of the St. Croix County circuit court. I’ve found surprisingly little about this case, though that part of Wisconsin was growing very violent in the 1840s as white lumbermen and liquor salesmen were flooding the country.

Pg 56 of Containing cases decided from the December term, 1850, until the organization of the separate Supreme Court in 1853: Volume 3 of Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Wisconsin: With Tables of the Cases and Principal Matters, and the Rules of the Several Courts in Force Since 1838, Wisconsin. Supreme Court Authors: Wisconsin. Supreme Court, Silas Uriah Pinney (Google Books).

The man killed, Alexander Livingston, was a liquor dealer himself.

Alexander Livingston, a man who in youth had had excellent advantages, became himself a dealer in whisky, at the mouth of Wolf creek, in a drunken melee in his own store was shot and killed by Robido, a half-breed. Robido was arrested but managed to escape justice.

~From Fifty Years in the Northwest by W.H.C Folsom

Several pages later, Folsom writes:

At the mouth of Wolf creek, in the extreme northwestern section of this town, J. R. Brown had a trading house in the ’30s, and Louis Roberts in the ’40s. At this place Alex. Livingston, another trader, was killed by Indians in 1849. Livingston had built him a comfortable home, which he made a stopping place for the weary traveler, whom he fed on wild rice, maple sugar, venison, bear meat, muskrats, wild fowl and flour bread, all decently prepared by his Indian wife. Mr. Livingston was killed by an Indian in 1849.

Folsom makes no mention of Oshoga, and I haven’t found anything else on what happened to him or Robido (Robideaux?).

It’s hard to say if this Oshoga is the Ozhogen’s of Ely’s journals or the Oshogay of Warren’s. Wolf Creek is on the St. Croix, but it’s not far from the Chippewa River country either, and the Oshogay of Warren seems to have covered a lot of ground in the fur trade. Warren’s journal, linked in #4, contains a similar story of a killing and “frontier justice” leading to lynch mobs against the Ojibwe. To escape the violence and overcrowding, many Ojibwe from that part of the country started to relocate to Fond du Lac, Lac Courte Oreilles, or La Pointe/Bad River. La Pointe is also where we find the next mention of Oshogay.

7) From 1851 to 1853, a new voice emerged loudly from the La Pointe Band in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. It was that of Buffalo’s speaker Oshogay (or O-sho-ga), and he spoke out strongly against Indian Agent John Watrous’ handling of the Sandy Lake payments (see this post) and against Watrous’ continued demands for removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. There are a number of documents with Oshogay’s name on them, and I won’t mention all of them, but I recommend Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren and Howard Paap’s Red Cliff, Wisconsin as two places to get started.

Chief Buffalo was known as a great speaker, but he was nearing the end of his life, and it was the younger chief who was speaking on behalf of the band more and more. Oshogay represented Buffalo in St. Paul, co-wrote a number of letters with him, and most famously, did most of the talking when the two chiefs went to Washington D.C. in the spring of 1852 (at least according to Benjamin Armstrong’s memoir). A number of secondary sources suggest that Oshogay was Buffalo’s son or son-in-law, but I’ve yet to see these claims backed up with an original document. However, all the documents that identify by band, say this Oshogay was from La Pointe.

The Wisconsin Historical Society has digitized four petitions drafted in the fall of 1851 and winter of 1852. The petitions are from several chiefs, mostly of the La Pointe and Lac Courte Oreilles/Chippewa River bands, calling for the removal of John Watrous as Indian Agent. The content of the petitions deserves its own post, so for now we’ll only look at the signatures.

November 6, 1851 Letter from 30 chiefs and headmen to Luke Lea, Commissioner of Indian Affairs: Multiple villages are represented here, roughly grouped by band. Kijiueshki (Buffalo), Jejigwaig (Buffalo’s son), Kishhitauag (“Cut Ear” also associated with the Ontonagon Band), Misai (“Lawyerfish”), Oshkinaue (“Youth”), Aitauigizhik (“Each Side of the Sky”), Medueguon, and Makudeuakuat (“Black Cloud”) are all known members of the La Pointe Band. Before the 1850s, Kabemabe (Gaa-bimabi) and Ozhoge were associated with the villages of the Upper St. Croix.

November 8, 1851, Letter from the Chiefs and Headmen of Chippeway River, Lac Coutereille, Puk-wa-none, Long Lake, and Lac Shatac to Alexander Ramsey, Superintendent of Indian Affairs: This letter was written from Sandy Lake two days after the one above it was written from La Pointe. O-sho-gay the warrior from Lac Shatac (Lake Chetek) can’t be the same person as Ozhoge the chief unless he had some kind of airplane or helicopter back in 1851.

Undated (Jan. 1852?) petition to “Our Great Father”: This Oshoga is clearly the one from Lake Chetek (Chippewa River).

Undated (Jan. 1852?) petition: These men are all associated with the La Pointe Band. Osho-gay is their Speaker.

In the early 1850s, we clearly have two different men named Oshogay involved in the politics of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. One is a young warrior from the Chippewa River country, and the other is a rising leader among the La Pointe Band.

Washington Delegation July 22, 1852 This engraving of the 1852 delegation led by Buffalo and Oshogay appeared in Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians. Look for an upcoming post dedicated to this image.

8) In the winter of 1853-1854, a smallpox epidemic ripped through La Pointe and claimed the lives of a number of its residents including that of Oshogay. It had appeared that Buffalo was grooming him to take over leadership of the La Pointe Band, but his tragic death left a leadership vacuum after the establishment of reservations and the death of Buffalo in 1855.

Oshogay’s death is marked in a number of sources including the gravestone at the top of this post. The following account comes from Richard E. Morse, an observer of the 1855 annuity payments at La Pointe:

The Chippewas, during the past few years, have suffered extensively, and many of them died, with the small pox. Chief O-SHO-GA died of this disease in 1854. The Agent caused a suitable tomb-stone to be erected at his grave, in La Pointe. He was a young chief, of rare promise and merit; he also stood high in the affections of his people.

Later, Morse records a speech by Ja-be-ge-zhick or “Hole in the Sky,” a young Ojibwe man from the Bad River Mission who had converted to Christianity and dressed in “American style.” Jabegezhick speaks out strongly to the American officials against the assembled chiefs:

…I am glad you have seen us, and have seen the folly of our chiefs; it may give you a general idea of their transactions. By the papers you have made out for the chiefs to sign, you can judge of their ability to do business for us. We had but one man among us, capable of doing business for the Chippewa nation; that man was O-SHO-GA, now dead and our nation now mourns. (O-SHO-GA was a young chief of great merit and much promise; he died of small-pox, February 1854). Since his death, we have lost all our faith in the balance of our chiefs…

This O-sho-ga is the young chief, associated with the La Pointe Band, who went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852.

9) In 1878, “Old Oshaga” received three dollars for a lynx bounty in Chippewa County.

Report of the Wisconsin Office of the Secretary of State, 1878; pg. 94 (Google Books)

It seems quite possible that Old Oshaga is the young man that worked with George Warren in the 1840s and the warrior from Lake Chetek who signed the petitions against Agent Watrous in the 1850s.

10) In 1880, a delegation of Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, and Lac du Flambeau chiefs visited Washington D.C. I will get into their purpose in a future post, but for now, I will mention that the chiefs were older men who would have been around in the 1840s and ’50s. One of them is named Oshogay. The challenge is figuring out which one.

Ojibwe Delegation c. 1880 by Charles M. Bell. [Identifying information from the Smithsonian] Studio portrait of Anishinaabe Delegation posed in front of a backdrop. Sitting, left to right: Edawigijig; Kis-ki-ta-wag; Wadwaiasoug (on floor); Akewainzee (center); Oshawashkogijig; Nijogijig; Oshoga. Back row (order unknown); Wasigwanabi; Ogimagijig; and four unidentified men (possibly Frank Briggs, top center, and Benjamin Green Armstrong, top right). The men wear European-style suit jackets and pants; one man wears a peace medal, some wear beaded sashes or bags or hold pipes and other props.(Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian).

- Upper row reading from the left.

- 1. Vincent Conyer- Interpreter 1,2,4,5 ?, includes Wasigwanabi and Ogimagijig

- 2. Vincent Roy Jr.

- 3. Dr. I. L. Mahan, Indian Agent Frank Briggs

- 4. No Name Given

- 5. Geo P. Warren (Born at LaPointe- civil war vet.

- 6. Thad Thayer Benjamin Armstrong

- Lower row

- 1. Messenger Edawigijig

- 2. Na-ga-nab (head chief of all Chippewas) Kis-ki-ta-wag

- 3. Moses White, father of Jim White Waswaisoug

- 4. No Name Given Akewainzee

- 5. Osho’gay- head speaker Oshawashkogijig or Oshoga

- 6. Bay’-qua-as’ (head chief of La Corrd Oreilles, 7 ft. tall) Nijogijig or Oshawashkogijig

- 7. No name given Oshoga or Nijogijig

The Smithsonian lists Oshoga last, so that would mean he is the man sitting in the chair at the far right. However, it doesn’t specify who the man seated on the right on the floor is, so it’s also possible that he’s their Oshoga. If the latter is true, that’s also who the unknown writer of the library caption identified as Osho’gay. Whoever he is in the picture, it seems very possible that this is the same man as “Old Oshaga” from number 9.

11) There is one more document I’d like to include, although it doesn’t mention any of the people we’ve discussed so far, it may be of interest to someone reading this post. It mentions a man named Oshogay who was born before 1860 (albeit not long before).

For decades after 1854, many of the Lake Superior Ojibwe continued to live off of the reservations created in the Treaty of La Pointe. This was especially true in the St. Croix region where no reservation was created at all. In the 1910s, the Government set out to document where various Ojibwe families were living and what tribal rights they had. This process led to the creation of the St. Croix and Mole Lake reservations. In 1915, we find 64-year-old Oshogay and his family living in Randall, Wisconsin which may suggest a connection to the St. Croix Oshogays. As with number 6 above, this creates some ambiguity because he is listed as enrolled at Lac Courte Oreilles, which implies a connection to the Chippewa River Oshogay. For now, I leave this investigation up to someone else, but I’ll leave it here for interest.

United States. Congress. House. Committee on Indian Affairs. Indian Appropriation Bill: Supplemental Hearings Before a Subcommittee. 1919 (Google Books).

This is not any of the Oshogays discussed so far, but it could be a relative of any or all of them.

In the final analysis

These eleven documents mention at least four men named Oshogay living in northern Wisconsin between 1800 and 1860. Edmund Ely met an old man named Oshogay in 1834. He is one. A 64-year old man, a child in the 1850s, was listed on the roster of “St. Croix Indians.” He is another. I believe the warrior from Lake Chetek who traded with George Warren in the 1840s could be one of the chiefs who went to Washington in 1880. He may also be the one who was falsely accused of killing Alexander Livingston. Of these three men, none are the Oshogay who went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852.

That leaves us with the last mystery. Is Ozhogens, the young son of the St. Croix chief Gaa-bimabi, the orator from La Pointe who played such a prominent role in the politics of the early 1850s? I don’t have a smoking gun, but I feel the circumstantial evidence strongly suggests he is. If that’s the case, it explains why those who’ve looked for his early history in the La Pointe Band have come up empty.

However, important questions remain unanswered. What was his connection to Buffalo? If he was from St. Croix, how was he able to gain such a prominent role in the La Pointe Band, and why did he relocate to La Pointe anyway? I have my suspicions for each of these questions, but no solid evidence. If you do, please let me know, and we’ll continue to shed light on this underappreciated Ojibwe leader.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892. Print.

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Folsom, William H. C., and E. E. Edwards. Fifty Years in the Northwest. St. Paul: Pioneer, 1888. Print.

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 12 August 2013. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1995. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Redix, Erik M. “The Murder of Joe White: Ojibwe Leadership and Colonialism in Wisconsin.” Diss. University of Minnesota, 2012. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. The Voice of the Crane Echoes Afar: The Sociopolitical Organization of the Lake Superior Ojibwa, 1640-1855. New York: Garland Pub., 1997. Print.

———–William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers: With Brief Notices of Passing Events, Facts, and Opinions, A.D. 1812 to A.D. 1842. Philadelphia, [Pa.: Lippincott, Grambo and, 1851. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

This post is on of several that seeks to determine how many images exist of Great Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855. To learn why this is necessary, read this post introducing the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

Today’s post looks at two paintings from the 1820s of Ojibwe men named Bizhiki (Buffalo). The originals are lost forever, but the images still exist in the lithographs that follow.

Pee-che-kir: A Chippewa Chief Lithograph from McKenney and Hall’s History of the Indian Tribes of North America based on destroyed original by Charles Bird King; 1824. (Wikimedia Images)

Pe-shick-ee: A Celebrated Chippeway Chief from the Aboriginal Port-Folio by James Otto Lewis. The original painting was done by Lewis at Prairie du Chien or Fond du Lac of Lake Superior in 1825 or 1826 (Wisconsin Historical Society).

1824 Delegation to Washington

Chronologically, the first known image to show an Ojibwe chief named Buffalo appeared in the mid-1820s at time when the Ojibwe and the United States government were still getting to know each other. Prior to the 1820s, the Americans viewed the Ojibwe as a large and powerful nation. They had an uncomfortably close history with the British, who were till lurking over the border in Canada, but they otherwise inhabited a remote country unfit for white settlement. To the Ojibwe, the Americans were chimookomaan, “long knives,” in reference to the swords carried by the military officers who were the first Americans to come into their country. It was one of these long knives, Thomas McKenney, who set in motion the gathering of hundreds of paintings of Indians. Two of these showed men named Buffalo (Bizhiki).

Charles Bird King: Self portrait 1815 (Wikimedia Images)

McKenney was appointed the first Superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1824. Indian Affairs was under the Department of War at that time, and McKenneyʼs men in the West were mostly soldiers. He, like many in his day, believed that the Indian nations of North America were destined for extinction within a matter of decades. To preserve a record of these peoples, he commissioned over 100 portraits of various Indian delegates who came to Washington from all over the U.S. states and territories. Most of the painting work fell to Charles Bird King, a skilled Washington portrait artist. Beginning in 1822, King painted Indian portraits for two decades. He would paint famous men like Black Hawk, Red Jacket, Joseph Brandt, and Major Ridge, but Kingʼs primary goal was not to record the stories of important individuals so much as it was to capture the look of a vanishing race.

No-tin copied from 1824 Charles Bird King original by Henry Inman. Noodin (Wind) was a prominent chief from the St. Croix country. King’s painting of Buffalo from St. Croix was probably also copied by Inman, but its location is unknown (Wikimedia Images).

In July of 1824, William Clark, the famous companion of Meriwether Lewis, brought a delegation of Sauks, Foxes, and Ioways to Washington to negotiate land cessions. Lawrence Taliaferro, the Indian agent at Fort St. Anthony (now Minneapolis), brought representatives of the Sioux, Menominee, and Ojibwe to observe the treaty process. The St. Croix chiefs Buffalo and Noodin (Wind) represented the Ojibwe.

Charles Bird King painted portraits of most of the Indians listed here in the the 1824 Washington group by Niles’ Weekly Register, July 31, 1824. (Google Books)

The St. Croix chiefs were treated well: taken to shows, and to visit the sights of the eastern cities. However, there was a more sinister motivation behind the governmentʼs actions. McKenney made sure the chiefs saw the size and scope of the U.S. Military facilities in Washington, the unspoken message being that resistance to American expansion was impossible. This message seems to have resonated with Buffalo and Noodin of St. Croix as it is referred to repeatedly in the official record. McKenney pointed Buffalo out as a witness to American power at the Treaty of Fond du Lac (1826). Schoolcraft and Allen mention Buffalo’s trip in their own ill-fated journey up the St. Croix in 1832 (see it in this post), and Noodin talks about the soldiers he saw in Washington in the treaty deliberations in the 1837 Treaty of St. Peters.

While in Washington, Buffalo, Noodin, and most of the other Indians in the group sat with King for portraits in oil. Buffalo was shown wearing a white shirt and cloak, holding a pipe, with his face painted red. The paintings were hung in the offices of the Department of War, and the chiefs returned to their villages.

James Otto Lewis

The following summer, St. Croix Buffalo and Noodin joined chiefs from villages throughout the Ojibwe country, as well as from the Sioux, Sac and Fox, Menominee, Ho-Chunk, Ioway, Ottawa, and Potawatomi at Prairie du Chien. The Americans had called them there to sign a treaty to establish firm borders between their nations. The stated goal was to end the wars between the Sioux and Ojibwe, but it also provided the government an opportunity to assert its authority over the country and to set the stage for future land cessions.

McKenney did not attend the Treaty of Prairie du Chien leaving it to Clark and Lewis Cass to act as commissioners. A quick scan of the Ojibwe signatories shows “Pee-see- ker or buffalo, St. Croix Band,” toward the bottom. Looking up to the third signature, we see “Gitspee Waskee, or le boeuf of la pointe lake Superior,” so both the St. Croix and La Pointe Buffalos were present among the dozens of signatures. One of the government witnesses listed was an artist from Philadelphia named James Otto Lewis. Over the several days of negotiation, Lewis painted scenes of the treaty grounds as well as portraits of various chiefs. These were sent back to Washington, some were copied and improved by King or other artists, and they were added to the collection of the War Department.

The following year, 1826, McKenney himself traveled to Fond du Lac at the western end of Lake Superior to make a new treaty with the Ojibwe concerning mineral exploration on the south shore. Lewis accompanied him and continued to create images. At some point in these two years, a Lewis portrait of an Ojibwe chief named Pe-schick-ee (Bizhiki) appeared in McKenneyʼs growing War Department collection.

Lithographs

By 1830, McKenney had been dismissed from his position and turned his attention to publishing a portfolio of lithographs from the paintings in the War Department collection. Hoping to cash in his own paintings by beating McKenney to the lithograph market, Lewis released The Aboriginal Port Folio in May of 1835. It included 72 color plates, one of which was Pe-schick-ee: A Celebrated Chippeway Chief.

Pencil sketch of Pee-che-kir by Charles Bird King. King made these sketches after his original paintings to assist in making copies. (Herman J. Viola, The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King.)

Due to financial issues The History of the Indian Tribes of North America, by McKenney with James Hall, would not come out in full release until the mid 1840s. The three-volume work became a bestseller and included color plates of 120 Indians, 95 of which are accompanied by short biographies. Most of the lithographs were derived from works by King, but some were from Lewis and other artists. Kingʼs portrait of Pee-Che-Kir: A Chippewa Chief was included among them, unfortunately without a biography. However, we know its source as the painting of the St. Croix Buffalo in 1824. Noodin and several others from that delegation also made it into lithograph form. The original War Department paintings, including both Pee-Che-Kir and Pe-schick-ee were sent to the Smithsonian, where they were destroyed in a fire in 1858. Oil copies of some of the originals, including Henry Inmanʼs copy of Kingʼs portrait of Noodin, survive, but the lithographs remain the only known versions of the Buffalo portraits other than a pencil sketch of the head of Pee-Che-Kir done by King.

The man in the Lewis lithograph is difficult to identify. The only potential clue we get from the image itself is the title of “A Celebrated Chippeway Chief,” and information that it was painted at Prairie du Chien in 1825. To many, “celebrated” would indicate Buffalo from La Pointe, but in 1825, he was largely unknown to the Americans while the St. Croix Buffalo had been to Washington. In the 1820s, La Pointe Buffaloʼs stature was nowhere near what it would become. However, he was a noted speaker from a prominent family and his signature is featured prominently in the treaty. Any assumptions about which chief was more “celebrated” are difficult.

In dress and pose, the man painted by Lewis resembles the King portrait of St. Croix Buffalo. This has caused some to claim that the Lewis is simply the original version of the King. King did copy and improve several of Lewisʼ works, but the copies tended to preserve in some degree the grotesque, almost cartoonish, facial features that are characteristic of the self-taught Lewis (see this post for another Lewis portrait). The classically-trained King painted highly realistic faces, and side-by-side comparison of the lithographs shows very little facial resemblance between Kingʼs Pee-Che-Kir and Lewisʼ Pe-schick-ee.

Thomas L. McKenney painted in 1856 by Charles Loring Elliott (Wikimedia Images)

Of the 147 War Department Indian portraits cataloged by William J. Rhees of the Smithsonian prior to the fire, 26 are described as being painted by “King from Lewis,” all of which are from 1826 or after. Most of the rest are attributed solely to King. Almost all the members of the 1824 trip to Washington are represented in the catalog. “Pee-che-ker, Buffalo, Chief of the Chippeways.” does not have an artist listed, but Noodin and several of the others from the 1824 group are listed as King, and it is safe to assume Buffalo’s should be as well. The published lithograph of Pee-che-kir was attributed solely to King, and not “King from Lewis” as others are. This further suggests that the two Buffalo lithographs are separate portraits from separate sittings, and potentially of separate chiefs.

Even without all this evidence, we can be confident that the King is not a copy of the Lewis because the King portrait was painted in 1824, and the Lewis was painted no earlier than 1825. There is, however, some debate about when the Lewis was painted. From the historical record, we know that Lewis was present at both Prairie du Chien and Fond du Lac along with both the La Pointe Buffalo and the St. Croix Buffalo. When Pe- schick-ee was released, Lewis identified it as being painted at Prairie du Chien. However, the work has also been placed at Fond du Lac.

The modern identification of Pee-che-kir as a copy of Pe-schick-ee seems to have originated with the work of James D. Horan. In his 1972 book, The McKenney-Hall Portrait Gallery of American Indians, he reproduces all the images from History of the Indian Tribes, and adds his own analysis. On page 206, he describes the King portrait of Pee-che-kir with:

“Peechekir (or Peechekor, Buffalo) was “a solid, straight formed Indian,” Colonel McKenney recalled many years after the Fond du Lac treaty where he had met the chief. Apparently the Chippewa played a minor role at the council.

Original by James Otto Lewis, Fond du Lac council, 1826, later copied in Washington by Charles Bird King.”

Presumably, the original he refers to would be the Lewis portrait of Pe-schick-ee. However, Horanʼs statement that McKenney met St. Croix Buffalo at Fond du Lac is false. As we already know, the two men met in 1824 in Washington. It is puzzling how Horan did not know this considering he includes the following account on page 68:

The first Indian to step out of the closely packed lines of stone-faced red men made McKenney feel at home; it was a chief he had met a few years before in Washington. The Indian held up his hand in a sign of peace and called out:

“Washigton [sic]… Washington… McKenney shook hands with the chief and nodded to Lewis but the artist had already started to sketch.”

McKenneyʼs original account identifies this chief as none other than St. Croix Buffalo:

In half an hour after, another band came in who commenced, as did the others, by shaking hands, followed, of course, by smoking. In this second band I recognized Pee-che-kee, or rather he recognized me–a chief who had been at Washington, and whose likeness hangs in my office there. I noticed that his eye was upon me, and that he smiled, and was busily employed speaking to an Indian who sat beside him, and no doubt about me. His first word on coming up to speak to me was, “Washington”–pointing to the east. The substance of his address was, that he was glad to see me–he felt his heart jump when he first saw me–it made him think of Washington, of his great father, of the good living he had when he visited us–how kind we all were to him, and that he should never forget any of it.

From this, Horan should have known not only that the two men knew each other, but also that a portrait of the chief (Kingʼs) already was part of the War Department collection and therefore existed before the Lewis portrait. Horanʼs description of Lewis already beginning his sketch does not appear in McKenneyʼs account and seems to invented. This is not the only instance where Horan confuses facts or takes wide license with Ojibwe history. His statement quoted above that the Ojibwe “played a minor role” in the Treaty of Fond du Lac, when they were the only Indian nation present and greatly outnumbered the Americans, should disqualify Horan from being treated as any kind of authority on the topic. However, he is not the only one to place the Lewis portrait of Pe-schick-ee at Fond du Lac rather than Prairie du Chien.

Between, 1835 and 1838 Lewis released 80 lithographs, mostly of individual Indians, in a set of ten installments. He had intended to include an eleventh with biographies. However, a dispute with the publisher prevented the final installment from coming out immediately. His London edition, released in 1844 by another publisher, included a few short biographies but none for Pe-schick-ee. Most scholars assumed that he never released the promised eleventh installment. However, one copy of a self-published 1850 pamphlet donated by Lewisʼs grandson exists in the Free Library of Philadelphia. In it are the remaining biographies. Number 30 reads:

No. 30. Pe-shisk-Kee. A Chippewa warrior from Lake Huron, noted for his attachment to the British, with whom he always sided. At the treaty held at Fond du Lac, when the Council opened, he appeared with a British medal of George the III. on his breast, and carrying a British flag, which Gen. Cass, one of the Commissioners, promptly and indignantly placed under his feet, and pointing to the stars and stripes, floating above them, informed him that that was the only one permitted to wave there.

The Chief haughtily refused to participate in the business of the Council, until, by gifts, he became partly conciliated, when he joined in their deliberations. Painted at Fond du Lac, in 1826.

This new evidence further clouds the story. Initially, this description does not seem to fit what we know about either the La Pointe or the St. Croix Buffalo, as both were born near Lake Superior and lived in Wisconsin. Both men were also inclined to be friendly toward the American government. The St. Croix Buffalo had recently been to Washington, and the La Pointe Buffalo frequently spoke of his desire for good relations with the United States in later years. It is also troubling that Lewis contradicts his earlier identification of the location of the portrait at Prairie du Chien.

It is unlikely that Pe-schick-ee depicts a third chief given that no men named Buffalo other than the two mentioned signed the Treaty of Fond du Lac, and the far-eastern bands of Ojibwe from Lake Huron were not part of treaty councils with the Lake Superior bands. One can speculate that perhaps Lewis, writing 25 years after the original painting, mistook the story of Pe-schick-ee with that one of the many other chiefs he met in his travels, but there are some suggestions that it might, in fact, be La Pointe Buffalo.

The La Pointe Band traded with the British in the other side of Lake Superior for years after the War of 1812 supposedly confirmed Chequamegon as American territory. If you’ve read this post, you’ll know that Buffalo from La Pointe was a follower of Tenskwatawa, whose brother Tecumseh fought beside the British. On July 22, 1822, Schoolcraft writes:

At that place [Chequamegon] lived, in comparatively modern times, Wabojeeg and Andaigweos, and there still lives one of their descendants in Gitchee Waishkee, the Great First-born, or, as he is familiarly called, Pezhickee, or the Buffalo, a chief decorated with British insignia. His band is estimated at one hundred and eighteen souls, of whom thirty-four are adult males, forty-one females, and forty-three children.

It’s possible that it was La Pointe Buffalo with the British flag. Archival research into the Treaty of Fond du Lac could potentially clear this up. If I stumble across any, I’ll be sure to add it here. For now, we can’t say one way or the other which Buffalo is in the Lewis portrait.

The Verdict

Not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe: This is Chief Buffalo from St. Croix.

Inconclusive: This could be Buffalo from La Pointe or Buffalo from St. Croix.

Sources:

Horan, James David, and Thomas Loraine McKenney. The McKenney-Hall Portrait Gallery of American Indians. New York, NY: Bramhall House, 1986. Print.

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 21 June 2012. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Lewis, James O., The Aboriginal Port-Folio: A Collection of Portraits of the Most Celebrated Chiefs of the North American Indians. Philadelphia: J.O. Lewis, 1835-1838. Print.

———– Catalogue of the Indian Gallery,. New York: J.O. Lewis, 1850. Print.

Loew, Patty. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal.

Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2001. Print.

McKenney, Thomas Loraine. Sketches of a Tour to the Lakes of the Character and Customs of the Chippeway Indians, and of Incidents Connected with the Treaty of Fond Du Lac. Baltimore: F. Lucas, Jun’r., 1827. Print.

McKenney, Thomas Loraine, and James Hall. Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of Ninety-five of 120 Principal Chiefs from the Indian Tribes of North America. Washington: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1967. Print.

Moore, Robert J. Native Americans: A Portrait : The Art and Travels of Charles Bird King, George Catlin, and Karl Bodmer. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1997. Print.

Niles, Hezekiah, William O. Niles, Jeremiah Hughes, and George Beatty, eds. “Indians.” Niles’ Weekly Register [Baltimore] 31 July 1824, Miscellaneous sec.: 363. Print.

Rhees, William J. An Account of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington: T. McGill, 1859. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi,. [East Lansing]: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers: With Brief Notices of Passing Events, Facts, and Opinions, A.D. 1812 to A.D. 1842. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and, 1851. Print.

Viola, Herman J. The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1976. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Special thanks to Theresa Schenck of the University of Wisconsin and Charles Lippert for helping me work through this information, and to Michael Edmonds of the Wisconsin Historical Society, and Alice Cornell (formerly of the University of Cincinnati) for tracking down the single copy of the unpublished James Otto Lewis catalog.

Note: This is the final post of four about Lt. James Allen, his ten American soldiers and their experiences on the St. Croix and Brule rivers. They were sent from Sault Ste. Marie to accompany the 1832 expedition of Indian Agent Henry Schoolcraft to the source of the Mississippi River. Each of the posts gives some general information about the expedition and some pages from Allen’s journal.

On the night of August 1, 1831, the section of the Michigan Territory that would become the state of Wisconsin, was a scene of stark contrasts regarding the United States Army’s ability to force its will on Indian people. In the south, American forces had caught up and skirmished with the starving followers of Black Hawk near the mouth of the Bad Axe River in present-day Vernon County. The next morning, with the backing of the steamboat Warrior, the soldiers would slaughter dozens of men, women, and children as they tried to retreat across the Mississippi. The massacre at Bad Axe was the end of the Black Hawk War, the last major military resistance from the Indian nations of the Old Northwest.

Less than 300 miles upstream, Lieutenant James Allen had his bread stolen right out of his fire as he slept. Presumably, it was taken by Ojibwe youths from the Yellow River village on the St. Croix. Earlier that day, he had been unable to get convince any members of the Yellow River band to guide him up to the Brule River portage. The next morning, (the same day as the Battle of Bad Axe), Allen was able to buy a new bark canoe to take some load off his leaky fleet. However, the Ojibwe family that sold it to him was able to take advantage of supply and demand to get twice the amount of flour from the soldiers that they would’ve gotten from the local traders. Later that day, the well-known chief Gaa-bimabi (Kabamappa), from the upper St. Croix, brought him a desperately-needed map, so not all of his interactions with the Ojibwe that day were negative. However, each of these encounters showed clearly that the Ojibwe were neither cowed nor intimidated by the presence of American soldiers in their country.

In fact, Allen’s detachment must have been a miserable sight. They had fallen several days behind the voyageur-paddled canoes carrying Schoolcraft, the interpreter, and the doctor. Their canoes were leaking badly and they were running out of gum (pitch) to seal them up. Their feet were torn up from wading up the rapids, and one man was too injured to walk. They were running low on food, didn’t know how to find the Brule, and their morale was running dangerously low. If the War Department’s plan was for Allen to demonstrate American power to the Ojibwe, the plan had completely backfired.

The journey down the Brule was even more difficult for the soldiers than the trip up the St. Croix. I won’t repeat it all here because it’s in the posted pages of Allen’s journal in these four posts, but in the end, it was our old buddy Maangozid (see 4/14/13 post) and some other Fond du Lac Ojibwe who rescued the soldiers from their ordeal.

Allen’s journal entry after finally reaching Lake Superior is telling:

“[T]he management of bark canoes, of any size, in rapid rivers, is an art which it takes years to acquire; and, in this country, it is only possessed by Canadians [mix-blooded voyageurs] and Indians, whose habits of life have taught them but little else. The common soldiers of the army have no experience of this kind, and consequently, are not generally competent to transport themselves in this way; and whenever it is required to transport troops, by means of bark canoes, two Canadian voyageurs ought to be assigned to each canoe, one in the bow, and another in the stern; it will then be the safest and most expeditious method that can be adopted in this country.”

The 1830s were the years of Indian Removal throughout the United States, but at that time, the American government had no hope of conquering and subduing the Ojibwe militarily. When the Ojibwe did surrender their lands (in 1837 and 1842 for the Wisconsin parts), it was due to internal politics and economics rather than any serious threat of American invasion. Rather than proving the strength of the United States, Allen’s expedition revealed a serious weakness.

The Ojibwe weren’t overconfident or ignorant. The very word for Americans, chimookomaan (long knife), referred to soldiers. A handful of Ojibwe and mix-blooded warriors had fought the United States in the War of 1812 and earlier in the Ohio country. Bizhiki and Noodin, two chiefs whose territory Allen passed through on his ill-fated journey, had been to Washington in 1824 and saw the army firsthand. The next year, many more chiefs got to see the long knives in person at the Treaty of Prairie du Chien. Finally, the removal of their Ottawa and Potawatomi cousins and other nations to Indian Territory in the 1830s was a well-known topic of concern in Ojibwe villages. They knew the danger posed by American soldiers, but the reality of the Lake Superior Country in 1832 was that American power was very limited.

The journal picks up from part 3 with Allen and crew on the Brule River with their canoes in rapidly-deteriorating condition. They’ve made contact with the Fond du Lac villagers camped at the mouth, but there are still several obstacles to overcome.

Doc. 323, pg. 66

Allen’s journal is part of Phillip P. Mason’s edition of Schoolcraft’s Expedition to Lake Itasca: The Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi (1958). However, these Google Books pages come from the original publication as part of the United States Congress Serial Set.

James Allen (1806-1846)

Collections of the Iowa Historical Society

Allen and all of his men survived the ordeal of the 1832 expedition. He returned to La Pointe on August 11 and left the next day with Dr. Houghton. The two men returned to the Soo together, stopping at the great copper rock on the Ontonagon River along the way.

On September 13, 1832, he wrote Alexander Macomb, his commander at Fort Brady. The letter officially complained about Schoolcraft “unnecessarily and injuriously” leaving the soldiers behind at the mouth of the St. Croix. When the New York American published its review of Schoolcraft’s Narrative on July 19, 1834, it expressed “indignation and dismay” at the “un-Christianlike” behavior of the agent for abandoning the soldiers in the “enemy’s country.” The resulting controversy forced Schoolcraft to defend himself in the Detroit Journal and Michigan Advertiser where he pointed out Allen’s map’s importance to the Narrative. He also reminded the public that the Ojibwe and the United States were considered allies.

James Allen went on to serve in Chicago and at the Sac and Fox agency in Iowa Territory. After the Mexican War broke out in 1846, he traveled to Utah and organized a Mormon Battalion to fight on the American side. He died on his way back east on August 23, 1846. He was only forty years old. (John Lindquist has great website about the career of James Allen with much more information about his post-1832 life).

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Loew, Patty. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2001. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi,. [East Lansing]: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.

Note: This is the third of four posts about Lt. James Allen, his ten American soldiers and their experiences on the St. Croix and Brule rivers. They were sent from Sault Ste. Marie to accompany the 1832 expedition of Indian Agent Henry Schoolcraft to the source of the Mississippi River. Each of the posts will give some general information about the expedition and some pages from Allen’s journal.

Douglass Houghton (1809-1845) was the naturalist and physician for the expedition. While traveling with Schoolcraft’s lead group, he expressed frequent concern for Allen and the soldiers as they fell behind (painted by Alva Bradish, 1850; Wikimedia Commons).

Schoolcraft’s original book takes up the first quarter of the pages in the 1958 edition of Narrative of an Expedition, edited by Phillip P. Mason. The rest of the pages are six appendixes including the journals of Douglass Houghton the surgeon and geologist, W.T. Boutwell the missionary, and Allen. Of the four, Schoolcraft’s provides the blandest reading. His positive, official spin on everything offers little glimpse into his psyche. In contrast, Houghton gives us a unique account of smallpox vaccinations, botany, and geology. Boutwell gives us detailed descriptions of Ojibwe religious practices through his zealous missionary filter. His frequent complaints about mosquitoes, profane soldiers, Indian drumming, and voyageur gambling ruining his Sabbaths are very humorous to those who aren’t sympathetic to his mission.

Allen’s journal is fascinating. He was sent by the War Department to record information about the geography of the country and its people for military purposes. Officially the Ojibwe and the United States were friendly. Schoolcraft, being married into a prominent Ojibwe family at the Sault, promoted this idea. However, a sense of future military confrontation looms over the narrative. The Indian Removal Act was only two years old, and Black Hawk’s War broke out just as the expedition was starting out. In 1832, lasting peace between the Ojibwe and the United States was not automatically guaranteed.

The journal reads, at times, like a post-modern anti-colonial novel complete with Allen as the villainous narrator looking to get rich off Lake Superior copper and making war plans against Leech Lake. However, Allen’s writing style allows the reader in as Schoolcraft’s doesn’t, and he shows himself to be thoughtful and observant.

Allen’s primary objective was to protect Schoolcraft and show the Ojibwe that the United States could easily deliver soldiers to their remotest villages. This mission proved difficult from the beginning. Once they left Lake Superior and reached the Fond du Lac portages, it became evident that Allen’s soldiers had no canoe experience and could not keep up with Schoolcraft’s mix-blooded voyageurs. Schoolcraft never seems overly concerned about this, and much of Allen’s narrative is about his men painfully trying to catch up while the Ojibwe and mix-blooded guides laugh at their floundering techniques for getting through rapids.

Through all the hardship, though, Allen did complete the journey to Elk Lake (Itasca) and back down the Mississippi to Fort Snelling. His map of the trip was praised back east as a great contribution to world geography, and Schoolcraft used it to illustrate the published narrative. However, it was the final stretch through the St. Croix and Brule, after Schoolcraft had already declared the expedition a success, where things really got bad for the soldiers.

Continued from Part 2:

Section of Allen’s map showing the St. Croix to Brule portage. Note Gaa-bimabi’s (Keppameppa’s) village on Whitefish Lake near present-day Gordon, Wisconsin. (Reproduced by John Lindquist).

At this point, Allen and his men have fallen multiple days behind Schoolcraft. They have no knowledge of the country save a few rough maps and descriptions. Their canoes are falling apart, and they are physically beaten from their difficult journey up the St. Croix. In theory, the portage over the hill to the Brule should be an easy one given the fact they have little food and supplies left to carry. However, the men are demoralized and ready to quit. Little do they know, the darkest days of their journey are still to come.

Doc. 323, pg. 63

Allen’s journal is part of Phillip P. Mason’s edition of Schoolcraft’s Expedition to Lake Itasca: The Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi (1958). However, these Google Books pages come from the original publication as part of the United States Congress Serial Set.

Note: This is the first of four posts about Lt. James Allen, his ten American soldiers and their experiences on the St. Croix and Brule rivers. They were sent from Sault Ste. Marie to accompany the 1832 expedition of Indian Agent Henry Schoolcraft to the source of the Mississippi River. Each of the posts will give some general information about the expedition and some pages from Allen’s journal. The journal picks up July 26, 1832, after the expedition has already reached the source, proceeded downriver to Fort Snelling (Minneapolis) and was on its way back to Lake Superior.

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (1793-1864)

Although I’ve been aware of it for some time, and have used parts of it before, I only recently read Henry Schoolcraft’s, Narrative of an Expedition Through the Upper Mississippi to Itasca Lake: The Actual Source of this River from cover to cover. The book, first published in 1834, details Schoolcraft’s 1832 expedition through northern Wisconsin and Minnesota. As Indian agent at Sault Ste. Marie, he was officially sent by the Secretary of War, Lewis Cass, to investigate the ongoing warfare between the Ojibwe and Dakota Sioux. His personal goal, however, was to reach the source of the Mississippi River and be recognized as its discoverer.

Schoolcraft’s expedition included a doctor to administer smallpox vaccinations, an interpreter (Schoolcraft’s brother-in-law), and a protestant missionary. Having been west before, Schoolcraft knew what it would take to navigate the country. He hired several mix-blooded voyageurs who are hardly mentioned in the narrative, but who paddled the canoes, carried the portage loads, shot ducks, and did the other work along the way.

Ozhaawashkodewekwe (Susan Johnston) was the mother-in-law of Schoolcraft and the mother of expedition interpreter George Johnston. Born in the Chequamegon region, she is a towering figure in the history of Lake Superior during the late British and early American periods.

Attached the the expedition was Lt. James Allen and a detachment of ten soldiers, whose purpose was to demonstrate American power over the Ojibwe lands. The United States had claimed this land since the Treaty of Paris, but it was only after the War of 1812 that the British withdrew allowing American trading companies to move in. Still, by 1832 the American government had very little reach beyond its outposts at the Sault, Prairie du Chien, and Fort Snelling. The Ojibwe continued to trade with the British and war with the Dakota in opposition to their “Great Father” in Washington’s wishes.

This isn’t to say the Ojibwe were ignorant of the Americans and their military. By 1832, the Ojibwe were well aware of and concerned about the chimookomaanag (long knives) and what they were doing to other Indian nations to the south and east. However, the reality on the ground was that the Ojibwe were still in power in their lands.

Doc. 323, pg. 57

Allen’s journal is part of Phillip P. Mason’s edition of Schoolcraft’s Expedition to Lake Itasca: The Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi (1958). However, these Google Books pages come from the original publication as part of the United States Congress Serial Set.