Edwin Ellis Incidents: Number IV

August 31, 2018

By Amorin Mello

Originally published in the July 14th, 1877, issue of The Ashland Press. Transcribed with permission from Ashland Narratives by K. Wallin and published in 2013 by Straddle Creek Co.

… continued from Number III.

EARLY RECOLLECTIONS OF ASHLAND.

“OF WHICH I WAS A PART.”

Number IV

My Dear Press: – In March 1855, Conrad and Adam Goeltz – then young men, came to Ashland. They were natives of Wittenberg, and Conrad had served six years in the Cavalry of that Kingdom; but liking freedom, he bade adieu to the King, his master, and came to the “Land of the Free.” They both cleared land near the town site, which they afterwards pre-empted, and bought from the U.S. Government. For several years both of them lived in Michigan, but upon the revival of Ashland they came back to their early home. Katy Goeltz, Conrad’s Daughter, was the first white child born in this town, in the fall of 1855. Henry Dretler, Mrs. Conrad Goeltz’s father, came early and bought a quarter section of land. He died here in 1858 and was buried near the present residence of Mr. Durfee.

In June 1855, Dr. Myron Tompkins (brother-in-law of Mr. Whittlsey) came to the bay in search of health. He had been driven from Illinois by ague and rheumatism. The climate cured the ague, and accidentally falling off from a raft in the bay – the severe shock cured the rheumatism. Being thus cured by our climate and water, he has ever since lived on the lake. He is a well-educated physician. At present he is the physician of the Silver Islet Mining Company, on the North Shore of the Lake.

I recall others who came in 1855; Andrew Scobie, now of Ontonagon, Thomas Danielson, Charles Day, (now farming on Fish Creek,) Joseph Webb, Bernard Hoppenjohn, Duncan Sinclair, Lawrence Farley, and Austin Corser. Farley died many years ago, but his widow, after years of absence, has again returned to Ashland. Austin Corser in the summer of 1855 began a farm on the east side of Fish Creek, about half a mile above the mouth. Remaining only two or three years, he went to Ontonagon and afterwards to Iron River – in a wild lonely glen – where in after years from 1873 to 1876. He sold his homestead on which the Scranton Mining Company was formed for a snug little fortune, on which he settled down on a farm near Waukegan, Illinois.

John Beck, also coming in the early days of Ashland. He pre-empted and lived upon the spot now laid out and occupied as our cemetery. His wife was the first adult person who died in this town. The remains of the house in which she died may be seen near the Ashland Lumber Company’s store. He was for many years an active explorer for minerals, was the originator of the Montreal River Copper Mining Company. Subsequently he discovered silver lodes on the North Shore, in Canada. He is now engaged in gold mining in California.

Albert C. Stuntz was also one of our early settlers. He is a brother of Geo. R. Stuntz, to whom reference has already been made. He was here engaged in practicing surveying and ran many hundred miles of township and section lines in this and neighboring counties. The townships embracing our Penoka Iron Range were subdivided by him in 1856 and ’57. He once represented this district in the Legislature. His old home is in ruins on the east bank of Bay City creek. Mrs. Stuntz, who endured much hardship and privation died here in 1862. Mr. S. at present lives at Monroe, in this State.

Geo. E. Stuntz. nephew of A.C. and great grandson of the old Hessian Soldier mentioned in a former chapter, also came to Ashland early. In connection with his uncle and on his own account he did a great deal in the subdivision of the lands on the South Shore of the Lake. Soon after the outbreak of our civil war he enlisted in defense of the Union – was severely wounded and died, as it is supposed, in consequence of his wounds.

~ Sarah Adah Ashe – Part IV – San Bernardino by Marta Tilley Belanger

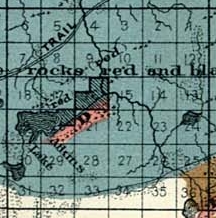

Welton’s mill and Sibley’s farm were both located along the trail south from Ashland to the Penokee Mountains on the 1860 Geological Map of the Penokie Range by Charles Whittlesey.

~ Geology of Wisconsin. Survey of 1873-1879.

Volume III., 1880, Plate XX, page 214.

J. T. Welton and T.P. Sibley, though never living in Ashland, were yet closely identified with its early history. Mr. Welton came about 1850 to Bad River, where he was Government Farmer among the Indians. He was an ingenious mechanic, and could build a water mill. He was on the lookout for a mill site, and finally in 1854 discovered the falls on White River, six miles south of Ashland. It was an unfailing supply of water, with abundant head and fall, and the river was not subject to great rises. As a mill site it has few rivals. His resolution was quickly formed. The rising town on the bay would afford a ready market for all the lumber he could make. The mill should be built. He corresponded with his brother-in-law, Mr. Sibley, and he was eager to come and make his fortune in this new country; and in Nov. 1855, Mr. Sibley and his wife and one little daughter, about a year old, landed upon our shores. During the summer of 1855 Mr. Welton had built a log house at White River. It still stands, though in ruins. Thither late in Nov. 1855, the two families removed. The sisters were refined, cultivated and Christian ladies from the Western Reserve, in Ohio – a spot itself favored by counting among its early settlers some of the best families of New England, and which had been the new center in the west, whence have validated those influences which have tended to improve and elevate the moral and religious condition of the millions of this new empire. They were of Puritan stock. An unbroken wilderness was around them and their nearest neighbors were at Ashland, six miles away. No time was lost. The work of opening up a farm and building a mill was at once begun. They had little money and the labor must be done with their own hands. The casting for the mill must be brought a thousand miles – from Detroit. Nearly a year of toil had passed, when in October, 1856, a few days before the election of James Buchanan to the Presidency – all the able bodied men were invited to go the mill raising at White River. We went and the frame was up, but it was not until 1857 that they could set the mill running. They were greatly impeded for want of capital in cutting logs and floating down the logs to the mill and sawing a few thousand feet of lumber. But before anything could be realized from it they must either haul it over bad roads to Ashland (6 miles) or raft it down many miles to the Lake. But the river was full of jams and “flood wood” – enough to discourage puny men.

The panic of 1857 and resulting hard times put an end to all building at Ashland, and so their hopes of selling their lumber near home were blasted and after struggling vainly for some time longer, Mr. Welton was finally compelled to abandon his home, which he had labored so hard to establish. He found friends and employment in the copper mines of Michigan, and after somewhat improving his fortunes finally settled in south western Iowa, where he now resides.

In some subsequent chapter I will, with your leave, recur to Mrs. Sibley and the circumstances connected with her death.

To be continued in Number V…

Penokee Survey Incidents: Number V

March 4, 2015

By Amorin Mello

The Survey of the Penoka Range and Incidents Connected with its Early History.

—

Number V.

~ History of Milwaukee, pg. 358

Friend Fifield:- The reader will no doubt remember that my last left us all anxiously awaiting the completion of the township surveys, which, up to this time, we had hoped would have been accomplished as soon, at least, as we were ready on our part, to “prove up.” But still the work lagged, and instead of being through and home in three months, as at first anticipated, it was now plainly seen that such was not to be the case. Three months had already elapsed since the work was commenced, yet the goal was apparently as far distant as over, and as we could not discharge our men, it was finally decided to explore the country south and west of the Range for the purpose of ascertaining, as far as possible, its adaption for a railroad from Milwaukee to the Range, as well as from the Range to Ashland, the latter of which must, of necessity, be built to move the iron. And in order that it might be properly done, Mr. Albert W. Whitcomb, a civil engineer of considerable experience, was sent up from Milwaukee, to superintend the work, who, after making one trip to the Range returned to Ashland and commenced his work by running what was afterwards known as the “Transit Line,” on account of its being run with that instrument. This line followed principally what was known as the Coburn Trail, which was the only one in use at that time by the company; crossing White River at Welton‘s mill, the Marengo at Sibley‘s, (now Martin Rhiem‘s.) and the outlet of Dr. Brunschweiler‘s old copper location, and thence to Ashland “Pond.” When it became evident that no good route could be found from that point to the Range on account of the heavy grades to be overcome, the work by transit was abandoned, and the balance was run by compass and chain only, simply to ascertain the exact distance in miles. This work, which should under ordinary circumstances, have been completed in ten days, occupied over a month, besides involving a large expenditure of money which might as well have been sunk in the ocean, as far as the Company was concerned, as no benefit whatever resulted from it except to the men employed in the work.

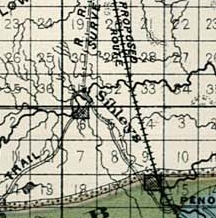

Palmer’s townsite claim located near Penokee Gap on Bad River with the “Coburn Trail” to Ashland. (Detail from Stuntz’s survey during May of 1858)

Subsequent, however, to the close of the survey upon the Transit Line, and the return of Mr. Whitcomb to Milwaukee, several extensive explorations were made to the south and west of the Range, by Gen. Cutler and myself, accompanied by Wheelock, Chas. Stevens, French Joe, (Joe Le Roy, with Big Joe as packer, and a Halfbreed called Little Alic as cook.) in one case nearly to the head waters of the Chippewa. These explorations, which were made with compass and chain, were by far the pleasantest part of my labors that summer, relieving us, as they did, not only of the monotony of camp life while awaiting the completion of the survey, but they also added largely to our knowledge of the topography, as well as the resources of the country south of the Range, then an unbroken wilderness, filled with beaver ponds, many of which were seen, but which is today, thanks to the energy and business tact of the gentlemen in charge of the Wisconsin Central railroad, beginning, metaphorically speaking, to bloom like the rose, and is destined, at no distant period, to take rank as one of the most wealthy and prosperous portions of our fair state. All honor to them for the same.

In this way our time was spent until September, when all homes of Stuntz being able to complete his work that season, unless some special providence should intervene, were abaonded, and preparations for spending the winter upon the Range were at once commenced. Gen Cutler immediately left for Milwaukee after additional supplies, first placing me in charge of the work. A pack train consisting of Stuntz’s pony, (old Jack) and Bascom‘s mare, were at once put upon the trail, in charge of Geo. Miller, a wild, harum-scarum Canuck from Canada West, who quickly stocked the Range with supplies.

But in order that the survey might yet be completed, if possible, additional men were put on, among whom was Wilhelm Goetzenburg, a Mechlinberger, at that time domiciled at Bay City and August Eckee, an old Courier de Bois, including all of our spare men, leaving me to keep camp at Penoka, which I did from about the middle of September to the 12th of October, during which time I saw no one except those who came in from the different claims at stated intervals, for supplies.

I see in your number of December 1, a reference by Hon. Asaph Whittlesey, to my sketch of Sibley and Lazarus, in which he not only confirms my statement, but goes one better in assigning him the belt as the champion liar, also which belt he (Sibley) was subsequently, however, compelled to surrender to John Beck. In consequence of Mr. Whittlesey’s statement I will relate one of Sibley’s yarns, told in the presence of Gen. Cutler, myself, Wheelock and a young man from St. Paul, by the name of Fargo, while eating dinner at his house on the Marengo, in August, 1857, which not only illustrates his powers as a yarn spinner, but the wonderful acoustic properties of his ears as well; being seated at the table, Sibley at once asked a blessing upon the food, for he could pray as well as lie, after which the question was asked by some one, how far it was possible to hear the human voice, upon which Sibley stated that he had not only heard the shouts of the people, but the words of the speaker also, distinctly, that were made at a political barbeque held in Ohio, in the fall of 1844, one hundred miles distant from where he was. Mr. Fargo, although no slouch of a liar himself, was so affected by this statement as to nearly faint, and finally made the remark that if that was not a lie, it came very near it; them lugs of Sibley’s were lugs as was lugs. Can John Beck beat that?

Harvey “Harry” Fargo was a cabinet maker, George R. Stuntz’s neighbor on the Minnesota Point in Duluth, an early mail carrier, and was in the 1853 census of Superior as “Arfargo.” ~ Duluth and St. Louis County, Minnesota; Their Story and People: An Authentic Narrative of the Past, with Particular Attention to the Modern Era in the Commercial, Industrial, Educational, Civic and Social Development, Volume 1, edited by Walter Van Brunt, 1921.

I wish to state at this time, also, a little incident in connection with Eckee, mentioned above, related to me by himself, which was this: That in the fall of 1846, he, in company with three others, in the employ of the Sigourney Lumber Co., of Quebec, ascended the river of the name three hundred miles in an open boat, for the purpose of cutting timber during the winter, and that when within three miles of their journey’s end, their boat was upset in a rapid, they barely escaping with their lives, but with the loss of the boat and all its contents, axes, fishing tackle and supplies. His companions, horrified at their situation, started immediately on their return, following the sinuosities of the river. He however, chose to remain, which he did until spring, never seeing a human face for six entire months. There were four oxen and two horses at the camp the care of which he claimed, kept him from going insane. It is needless to state that his companions were never heard from again. Although this incident has no immediate connection with my history, yet it serves to illustrate the hardships to which the class of men he belonged to are often called to suffer. He could never speak of that winter and its horrors, without tears.

But to return to the Range. Although I can truthfully say that the whole time spent upon the Range was to me one of unalloyed pleasure, yet that engaged during the latter part of September and up to the 20th of October, exceeded all the rest. The forest has, at all times, a charm for me, and the autumnal months doubly so; It is then and then only that its full glories can be seen; and in no country or section of country that it has ever been my privilege to visit, is the handiwork of Dame Nature’s gelid pencil, so grandly displayed as upon Lake Superior, and more particularly is this so, in and around the Range. No doubt the good people of Ashland think the scenery at the Gap very fine, and so it is. Yet that at the west end is far more so. Here the range terminates in a bold escarpment some 300 feet above the surrounding country, giving to an observer an unobstructed view east, west and south, for forty miles.

Indian trails to the “Rockland” townsite claim overlooking English Lake and the west end of the Penoka Range. Julius Austrian later claimed the “Rockland” site for his daughter’s estate.(Detail from Stuntz’s survey from May of 1858)

This was my favorite resort in those beautiful autumn mornings, where, seated upon the edge of the bluff, I would feast my eyes for hours upon that matchless panorama. Neither could I ever divest myself of the feeling that, while there, I was alone with God. I have seen, in the course of my life, many landscape paintings that were very beautiful, but never one that could at all compare with the views I enjoyed in the months of October 1857, from the west end of the Penoka Range. J.S.B.

Penokee Survey Incidents: Number II

February 12, 2015

By Amorin Mello

The Survey of the Penoka Range and Incidents Connected with its Early History

—

Number II.

Friend Fifield:– Notwithstanding the work upon the Range was delayed very much on account of the unwoodsman like conduct of the Milwaukee boys, referred to in my first communication, yet it did not cease,- the company having a few white men, previous employed, as well as a large number who were “to the Mannor born” that did not show the “white feather” on account of the mosquitos, gnats, gad flies and other vermin with which the woods were filled,– most of whom remained with us to the end.

Prominent among these last named was Joseph Houle, or “Big Joe” as he was usually called,– a giant halfbreed, (now dead), who was invaluable as a woodsman and packer. Some idea of Joe’s immense strength and power of endurance may be formed from the fact that he carried upon one occasion the entire contents, (200 lbs.) of a barrel of pork from Ironton to the Range without seeming to think it much of a feat. Among the party along on this trip was a young man taking his first lesson in woodcraft, whose animal spirits cropped out to such a degree that the leader caused to be placed upon his back a bushel of dried apples (33 lbs.), simply to keep him from climbing the trees, but before he reached the Range, his load, light as it was, proved too much for him, when Joe, in charity, relieved him of it, adding it to his own pack – making it 233 lbs. This was, without doubt the largest pack ever carried to the Range by any one man. There was an Indian, however, in the employ of the company, as a packer, (“Old Batteese“), who left Sidebotham‘s claim one morning at 7 A.M., went to Ironton and was back again to camp at 7 P.M. with 126 lbs. of pork, having traveled forty-two miles in ten hours. This was in July ’57, and was what I considered the biggest day’s work ever done for the company. The usual load, however, for a packer, was from sixty to eighty pounds.

Ironton townsite claim at Saxon Harbor with trails to Odanah and the Penoka Iron Range. (Detail from Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records)

The halfbreeds were sulky and mutinous at times, giving us some trouble, until Gen. Cutler, who was a strict disciplinarian, gave them a lesson that they did not soon forget and which occurred at follows:

The General and myself left Ironton just before the removal of our supplies to Ashland, with four of these boys, with provisions for the Range, to be delivered at Lockwood’s Station. But upon reaching Sidebotham’s, two of them refused to proceed any further, threw down their packs, and started on their return to Ironton. The General’s blood was up in a moment, and directing me to remain with the others until he returned, at once started after them. Reaching Ironton at 11 A.M., about an hour after their arrival, they were quite surprised at seeing him, but said nothing. The General at once directed Duncan Sinclair, who had charge of the supplies at that time, to make up two packs of one hundred pounds each, with ropes in place of the usual leathern strap, which was quickly done, the “rebels” looking sullenly on all the while. When all was ready he drew his revolver and ordered them to pick them up and start. They did not wait for a second order, but took them and started, he followed immediately behind. Nor did he let them lay them down again until they reached Lockwood’s at sunset, a distance of twenty-six miles. – That evening they were the most completely used up men I ever saw on the Range, and from that time forward were as submissive and obedient as could be desired. After that we never had any trouble. It was a lesson they never forgot.

Among the whites referred to in this article, was James Stephenson, a young man from Virginia, who came up with Stuntz as a surveyor. He was of light build, wiry and muscular – full of fun – very excitable and nervous, – but a good man for the woods. He had some knowledge of the compass, but not sufficient education to make a good surveyor. “Jim” got lost once and was out three days before he came into camp, which he did just as the party was starting out to find him. “Jim” would not have made a good rope walker. He was no Blondin. On the ground he was all right, but let him attempt to cross a stream of water, be it ever so small, upon a log, no matter if the log was six feet in diameter, and he would fall in sure. He fell in twice while lost and came near perishing with wet and cold in consequence of it. He left the company in the fall of ’57.

But the best man we had on the range that summer, as a surveyor, (except Albert Stuntz, and I very much doubt if he could beat him), was George E. Stuntz, a nephew of Albert’s, known among the boys as “Lazarus.” He was tall and slim, with a long thin face, blue eyes, long dark brown hair, stooped slightly when walking; walked with a swinging motion, spoke slow and loud – was fond of the woods, prided himself on his skill with the compass, and was, I think, the laziest man at that time in the county, except “Sibly,” who could discount him fifty and then beat him. But notwithstanding all this Albert could not have completed his survey that season without him. His lines never required any corrections. George was a singer – or thought he was, which is all the same. The recollections of some of his attempts in this line almost brings tears to my eyes from laughter, even now. Nearly every night in camp, the boys, after getting into a position where they could laugh without his seeing them, would coax him to sing. His favorite piece was a song called “The Frozen Limb.” What it meant I have no idea, and do not think he had. One verse of this only can I recall to mind, which ran as follows:

“One cold, frosty evening as Mary was sleeping –

Alone in her chamber, all snugly in bed. – She woke with a noise that did sorely affright her.

‘Who’s that at my window?’ she fearfully said.”

You can easily imagine how this would sound when sung through the nose in the hard shell style – each syllable ending with a jerk, something like this:

“Who’s-that-at-my-win-dow-she-fear-ful-ly-said-ud.”

George had a suit of clothes for the woods made of bed ticking, cap and all complete – all but the cap in one piece. The cap was after the “Dunce” pattern, ie, it ran to a point. The stripes instead of running up and down as they should have done, ran diagonally around him, giving him the appearance of a walking barber’s pole. He was a nice looking boy – he was.

Shortly after donning this beautiful suit, while crossing the Range, he suddenly found himself face to face with a full grown bear. It was no doubt a surprise to both parties,– it certainly was to the bear. For he took one square look and left for distant lands at a speed which, if kept up, would have carried him to Mexico in two days. “Not any of that in mine” was probably what was passing through his massive brain, but he made no sign. The boys who were surveying some fifteen miles south of the Range claimed to have met him that day, still on the jump. J.S.B.