Le Boeuf et Le Pain: Alexis Cadotte’s letter to Chief Buffalo and Manabozho, January 11, 1840

April 30, 2024

By Leo

This was supposed to be a short post highlighting an interesting document with some light analysis of the relationship between the Ojibwe chiefs at La Pointe and the ones on the British-Canadian side of Sault Ste. Marie. It’s grown into an unwieldy musing on the challenges of doing what we do here at Chequamegon History. If you are only interested in the document, here it is:

(Copy)

Sault St. Maries 11 Janvier 1840

A Msr. le Beuf chef au tête à la pointe}

Cher grand-père,

Nous avons Recu votre par le darnier voyage des Barque de la Société. Ala nous avons apris la mort de votre fils qui nous a cose Boucup de chagrain, nous avons aussi bien compri le reste de votre, nous somme satisfait de n avoir vien neuf à la tréte de la pointe plus que vous ave vien neuf vous même nous somme de plus contents de vous pour L année prochaine arrive ici à votre endroit tachez de va espere promilles que vous nous fait que nous ayon la satisfaction an vous voyent de vous a tete cas il nous manque des Beuf ici, nous isperon que vous vous l espère Sanger il bon que vous venite a venire aucure une au Sault est Boucoup change de peu que la vie du Le Pain ne pas ici peu etre quil vous quelque chose pas cette ocation espre baucoup de vous voir l’etee prochienne, nous avons rien de particulier a vous mas que si non que faire. Baucoup a vous contée car il y a de grande nouvelles qui regarde toute votre nation et la nôtre tachez de nous faire réponse à notre lettre par le même.

2 Toute notre famille sont ans asse santé et Madame Birron qui est malade depui un mois et demi, un autre de ce petit garcon malade de pui cinq jour. Mon cher grand père nous finisson au vous Souhaitons toute sorte de Bonne prospérité croyez moi pour la vis votre tautre et efficionne fils

Signed Alexi Cadotte

Mon nomele Mainabauzo,

Je vous fais le meme Discours a vous dece que je vien de dire ici au Bouf. Il faut absolument que vous vene nous voir ici particulièrement votre patron qui moi meme et mon fils il y a un an l’été Darnier je vous espère au aspeill à la pointe nous avant neuf après ent la réponce du contenu de notre di proure si vous vere nous rejoindre nous iron ansemble à l ile Manito Wanegue au présent Anglois Car les Mitif se toi en Britanique resoive à présent comme les Sauvage vous dire à votre Jandre La pluve blanche que nous avon pas compri la lettre mon chère on ete je fini au vous enbrassan toute croyez moi pour la vie votre neveux.

signed Alexis Cadotte

Toute la famille vous fon des complément. Complement tous nous parans particulièrement

signed Cadotte

If you only want the translation, keep scrolling. If you want the story, read on.

Several years ago, I received a copy of this letter from Theresa Schenck, author and editor of several of the most important recent books on Ojibwe history. She knew that I was interested in the life of Chief Buffalo of La Pointe and described it as a charming letter written to Buffalo by one of his Cadotte relatives at Sault Ste. Marie. Dr. Schenck made a special point of telling me there were jokes inside.

My immediate reaction was what many of you might be thinking, “But I don’t speak French!” Her response was very matter-of-fact, “Well you need to know French if you’re going to study Lake Superior history. Learn French.”

During the pandemic, I finally got to it, and according to Duolingo, I now have the equivalent of three years of high-school French even though I can’t speak it at all. I can read enough to decipher Alexis Cadotte’s handwriting, though, and get the words into Google Translate. That’s where we hit a second problem.

The French that Cadotte uses in 1840 is not the same French that Duolingo and Google Translate use in 2023. Ojibwe was almost certainly the mother tongue of Alexis, who was born at Lac Courte Oreilles around 1799, but later he would have picked up French, and later still English. However, the French spoken by Cadotte and his contemporaries was commonly called patois or Metis/Michif (Alexis spells it “Mitif”), and was a mixture of French, Ojibwe, and Cree. This letter shows that Cadotte had some formal education, but even formal Quebec French deviates significantly from modern standard French. This is all to say that the letter is filled with non-standard spellings and vocabulary.

Lacking confidence in my translation, I shared the letter with Patricia McGrath, a distant relative of Alexis’ and Canadian Chequamegon History reader, and with the help of her her cousin Stéphane, we combined to produce this:

(Copy)

Sault St. Maries 11 January 1840

To Mr. Le Boeuf, Head chief at La Pointe}

Dear grandfather,

We received your communication at the last arrival of the Company Boat. It was then that we learned of the death of your son, which left us in grief. We also understood the rest of your message. You are more satisfied to have us come again to the head of “La Pointe” than for you to come here yourself. We are more than happy to see you next year, when we arrive at your place, but we hold out hope for the promise you made to give us the satisfaction of seeing you here in person. We are missing some Beef here. We hope you agree. My blood, it would be good that you should come here soon. There are many changes at the Sault. One is that Le Pain does not live here anymore. Perhaps there is something wrong with the timing. We hope to see you next summer. We have nothing new in particular to say to you. Much has been said to you because there is great news, which concerns your entire nation and ours. Try to respond to our letter in the same way.

2 Our whole family is in good health but for Madame Birron, who has been ill for a month and a half, along with one of her little boys who has been sick for five days. My dear grandfather, we end by wishing you all kinds of good prosperity. Believe me, for life, your affectionate other son

Signed Alexi Cadotte

My namesake Mainabauzo,

I am making the same speech to you as I have just said here to Le Boeuf. You absolutely have to come see us here, especially your chief, who was with me and my son a year ago last summer. I hope you will welcome us to La Pointe. Please respond to the content of our report if you wish to join us, go together to Manito Wanegue Island and receive the presents of the English, because the Mitif, if you are in British territory, now receive them as the Indians do. You tell your son-in-law White Plover that we didn’t understand his letter. My dear one, we have finished greeting you all. Believe me, for life, your nephew.

signed Alexis Cadotte

The whole family sends salutations, especially the parents.

signed Cadotte

Food puns? Long, circular statements that seem to only say “come visit your relatives.” What the heck is going on here? Another letter, written by Alexis Cadotte on the same day, sheds some light.

Sault Ste Marie, January 11 1840

Cadotte clarifies here that Le Pain is yet another food pun–this time on Le Pin, or the Pine. Zhingwaakoons (Pine) was a powerful Ojibwe chief on the British side of the Sault. The Lagardes and their in-laws, the LeSages were Metis trading families in the region.

Cadotte clarifies here that Le Pain is yet another food pun–this time on Le Pin, or the Pine. Zhingwaakoons (Pine) was a powerful Ojibwe chief on the British side of the Sault. The Lagardes and their in-laws, the LeSages were Metis trading families in the region.Eustache Legarde

My dear friend,

I write you this to wish you good health & to send my compliments to all our friends. I make known to you the result of the counsel we held yesterday with the Bread.* The answer is now received. The English Government has accepted all the applications of the Indians in favor of the half breeds, so the half breeds will begin to receive presents of the Government next summer. Furthermore the Government promises to supply the Indians with all things necessary to cultivate the soil. Besides all this the Government promises to build houses for the Half breeds, and to let them have a Forge. The Bread (Pine) is looking for a convenient place to build a half breed village. I recommend that you tell this news to all who are concerned in this matter. I am very sorry to inform you that your youngest nephew died some days ago. The rest of Sages family appear to be well. I close wishing you all kind of prosperity.

Believe me your friend

Alexis Cadotte

*Pine

From this letter, it becomes clear who “The Bread” is. It also shows that Cadotte’s motivation for writing Buffalo and Manabozho goes beyond simply missing his relatives. He wants the La Pointe chiefs to maintain their relationship with the British government and potentially relocate to Canada permanently.

By 1840, the Lake Superior Ojibwe were beginning to feel the heat of American colonization. The influx of white settlers (aside from in the lumber camps on the Chippewa and St. Croix) had yet to begin in earnest, but missionaries had settled in Ojibwe villages, and their presence was far from universally welcomed. The fur trade was in steep decline, and the monopolistic American Fur Company was well into its transition into a business model based on debts, land cessions, and annuity payments (what Witgen calls the political economy of plunder). The Treaty of St. Peters (1837) further divided Ojibwe society, creating deep resentments between the Lake Superior Bands and the Mississippi and Leech Lake Bands. Resentments also grew between the “full bloods” who were able to draw annuities from treaties, and the “mix-bloods,” who did not receive annuities but were able to use American citizenship and connections to the fur company for continued economic gain post-fur trade. Finally, the specter of removal hung over any Indian nation that had ceded its lands. The Lake Superior Ojibwe were well aware of the fates of the Meskwaki-Sauk, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Ho-Chunk and other nations to their south.

Keeping up relations with the British offered benefits beyond just the material goods described by Cadotte. It forced the American government to remain on friendly terms with the Ojibwe to prove that they were a more benevolent people than the British. In negotiations, the Ojibwe leadership often reminded the U.S. of the generosity of the “British Father.” Canadian territory also offered a potential refuge in the event of forced removal. The Jay Treaty (1796) had drawn a line through Lake Superior on European maps, but in 1840, there was still Ojibwe territory on both sides of the lake, and the people of La Pointe had many relatives on both sides of the Soo.

Zhingwaakoons was a fierce advocate of Ojibwe self-determination, and Cadotte’s letter shows that Little Pine (a.k.a. The Bread) was beginning to implement his scheme to concentrate as many Ojibwe people as possible at Garden River. If he could add the Lake Superior bands on the American side to his number, it would strengthen his position with the British-Canadian authorities. The British were open to the idea, as the Ojibwe provided a military buffer against American aggression in the event of another war between the United States and the United Kingdom. The more Ojibwe on the border in Canada, the stronger the buffer.

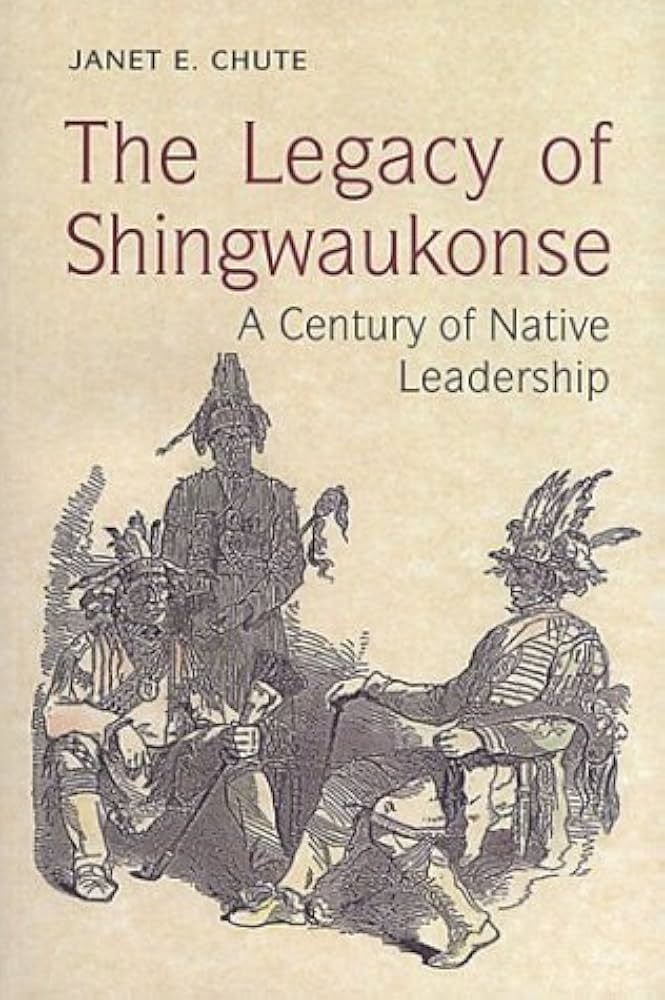

If you are interested in these topics, I strongly recommend this book:

I had already been writing Chequamegon History for a few years before I discovered The Legacy of Shingwaukonse: A Century of Native Leadership by Janet E. Chute through multiple fascinating references in Paap’s Red Cliff, Wisconsin. It was a nice wakeup call. It’s easy to get into the rut of only looking at records from the U.S. Government, the fur companies, and the missionary societies. There are other sources out there, of which the material coming from the British side of the Sault is a one example.

One of the puzzling things about the Alexis Cadotte letter is that it’s written in French. The common mother tongue of Cadotte, Buffalo, and Manabozho would have been Ojibwe. Granted, 1840 was a little early for Father Baraga’s Ojibwe writing system to have caught on, and Cadotte wouldn’t have known Sherman Hall’s system. In the following decades, letters in the Ojibwe language would become slightly more common, but at that early point, Cadotte may have still regarded Ojibwe as strictly a spoken language. It’s also possible that French offered a little more secrecy than English. Potential translators on Madeline Island would be other Metis (or Canadien heads of Metis families), whose goals would align more with Cadotte’s than with the United States Government’s. However, this is speculation.

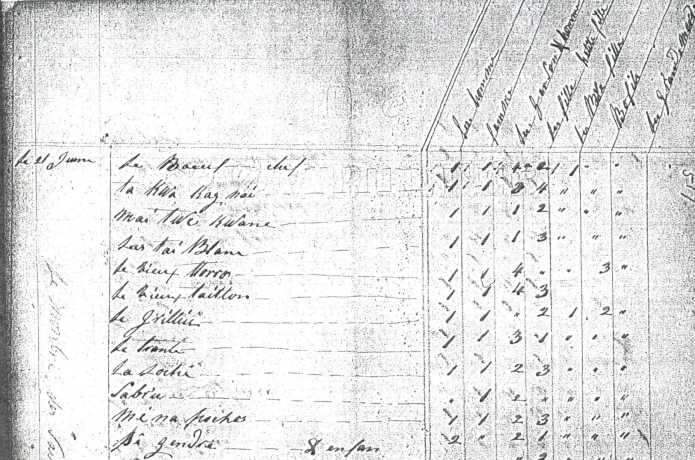

Chief Buffalo is probably referenced more than any other individual on Chequamegon History, but we haven’t had a lot to say about Manabozho. The truth is, we don’t have a lot of sources about him. From another French document, from another Cadotte, we know that he was living at La Pointe in 1831:

This 1831 census of La Pointe was taken by Big Michel Cadotte (first cousin of Alexis’ father, Little Michel Cadotte), and we see Le Boeuf listed as chief of the band. Me-na-poch-o is the eleventh household listed, and “se gendre,” an unidentified son-in-law and grandson are directly beneath him. 1 man (des hommes) 1 wife (des femmes) 2 sons (des hommes & garsons) and 3 daughters or granddaughters (des filles et petite filles) were living in Manabozho’s household.

We also see his name among the two La Pointe chiefs who signed the Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1825).

“Gitshee X Waiskee or Le Bouf of La pointe Lake superior” “Nainaboozho X of La pointe Lake Superior” Manabozho is named after the famous trickster and rabbit manitou who William Warren called “the universal uncle of the An-ish-in-aub-ag.” The initial consonant in the name of this powerful being could be an “M,” “N,” or “W” depending on grammatical context and regional dialect. Spellings in La Pointe documents from this era use all three.

And from the testimony from the 1839 payments at La Pointe, to mix-bloods and traders under the third and fourth articles of the Treaty of St. Peters (1837), we can see that Manabozho and Buffalo had a history of working with Alexis’ family. This testimony was given in favor of Alexis’ brother Louis’ claim against the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe:

Heirs of Michel Cadotte a British Subject

To amount of private property destroyed at the post occupied by Mr. Louis Corbin in the year 1809 or 1810, the claimant being then absent from said post but had left there his private property and that of his deceased father, Estimated at Eight hundred Dollars– $800.00

Louis Cadotte

His X mark

La Pointe 30th August 1838

G Franchere } witnesses

Eustache Roussain

N.B. The papers and books were all destroyed

L x C

We the undersigned Pé-jé-ké, chief of the Chippewa Tribe of Indians, residing at La Pointe and Mé-na-bou-jou, also of La pointe but formerly residing at Lac Court Oreil, do hereby certify that, to our knowledge, to the best of our recollection, about the year 1809 or 1810 the above claimant and his father had who was an Indian trader at said Lac Court Oreil, had their property destroyed by a band of Chippewa Indians, whilst said claimant was absent as well as his late father who had gone to Michilimackinac to get his usual years supply of Goods for the prosecution of his trade, which we firmly believe that the amount of Eight hundred Dollars as specified in the above account, is just and reasonable, and ought to be allowed. In witness whereof we have signed these presents the same having been read over and interpreted to us by Eustache Roussain. La Pointe this 30th day of August 1838.

Pé-jé-ké his X mark The Buffalo

Mé-na-bou-jo his X mark

This claim is for property destroyed by followers of the Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa on the Cadotte outfit post of Jean Baptiste Corbine at Lac Courte Oreille. Tenskwatawa, the brother of Tecumseh, had many followers in this region. Chequamegon History covered this incident, and Chief Buffalo’s role, back in 2013.

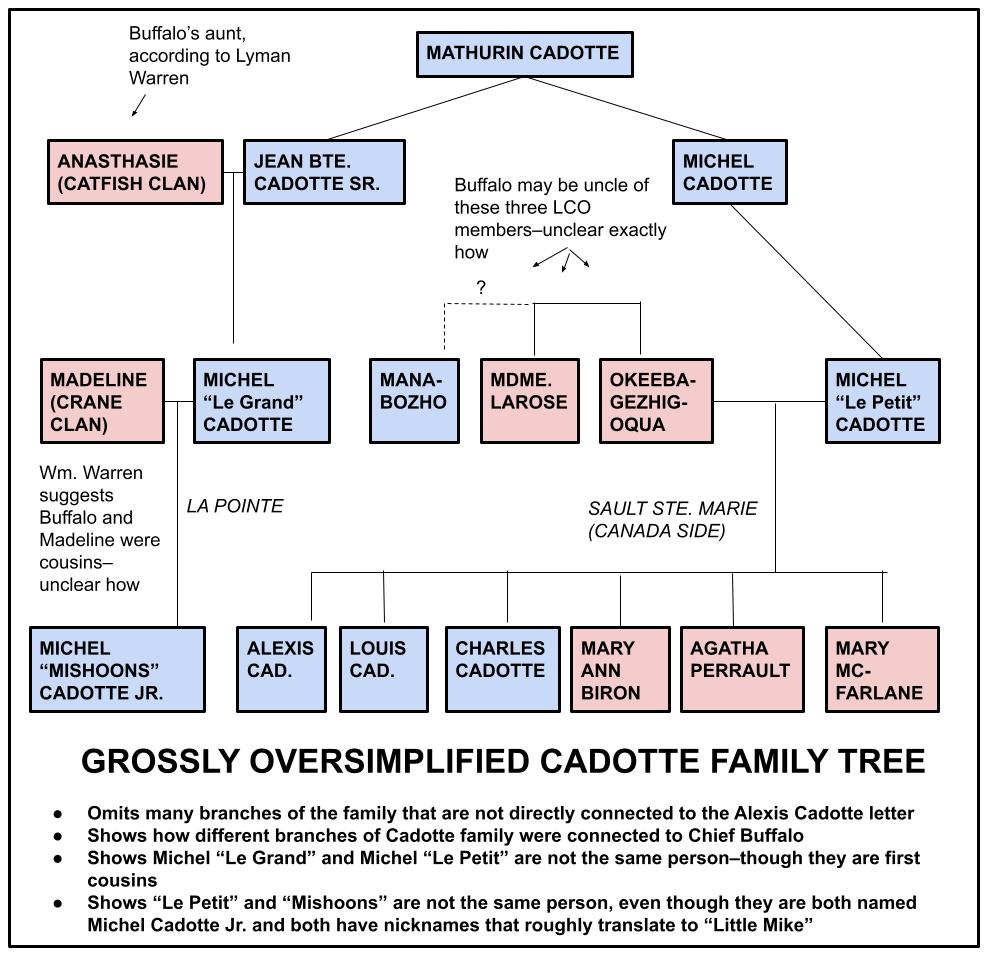

In the general mix blood claims, published in Theresa Schenck’s All Our Relations: Chippewa Mixed Bloods and the Treaty of 1837 (Amik Press; 2009), we learn more the exact relationship of Manabozho and Buffalo to the Cadottes. The former is their uncle, and the latter is their great uncle. Whether that makes the two men closely related to each other isn’t clear. The claims don’t say if they are blood relatives or in-laws of the Cadotte’s mother, Okeebagezhigoqua. However, if Manabozho was born into the band of Buffalo’s grandfather, Andegwiiyaas, and was living at Lac Courte Oreilles at the dawn of the 19th century, this would be consistent with a pattern of the “La Pointe Bands” of that era who were associated with La Pointe but living and hunting inland.

I should note that in Alexis Cadotte’s letter, he refers to Buffalo as grandpere rather than grand oncle. Don’t get too hung up on this. I am no expert on traditional Ojibwe conceptions of kinship other than to say they can be very different from European kinship systems and that it would not be at all unusual for a grandnephew to address his granduncle with the honorific title of grandfather.

From Francois, Joseph, and Charles LaRose claim

“Their Uncles are now residing at the Point, one of them is a respectable full blood Chippewa named Na-naw-bo-zho. The chief at La Pointe called Buffalo is their grand uncle. Their mother is a sister to the Cadottes. (Schenck, pg. 86)

From claims of Alexis, Louis, and Charles Cadotte, Mary Ann Biron, Agathe Perrault, and Mary McFarlane

“[Their] father was Michael Cadotte, a French trader in the ceded country, where he married a woman of the Ojibwa nation from Lake Coute Oreille named O-kee-ba-ge-zhi-go-qua.” (Schenck pg. 41)

“Five of the Earliest Indian Inhabitants of St. Mary’s Falls, 1855: 1) Louis Cadotte, John Boushe, Obogan, O’Shawan, [Louis] Gurnoe If this caption is to be trusted, andcaptions aren’t always to be trusted, there is a man named Louis Cadotte in this photo who would be about the right age to be Alexis’s brother. I read the numbers to indicate that he’s the man in the upper right. Others have interpreted this photo differently.

Sometimes different people have the same name. Very few of us can be expected to be fluent in English, Ojibwe, and regional dialects and creoles of 18th-century Quebec French (that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try!). It’s not only language. Subtle differences of religious and cultural understanding can skew the way a source is interpreted. Sources can be hard to come by, contradictory, misinterpreted by other researchers, or in unexpected places. Sometimes you stumble upon a previously unknown source that throws a monkey wrench into all your previous conclusions.

All this means that if you’re going to do this research, expect that you are going to have to humble yourself, admit mistakes, and admit when you might be pretty sure of something but not absolutely certain. My next few posts will explore these concepts further.

As always, thanks for reading,

Leo

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

P.S. Speaking of monkey wrenches…

Facts, Volumes 2-3. Facts Publishing Company. Boston, 1883. Pg. 66-68.

At Chequamegon History, we try to use reliable narrators. We try to use sources from before 1860. First-hand information is preferable to second or third-hand information, and we do not engage in much speculation or evaluation when it comes to questions of spirituality. This is especially true of traditional Ojibwe spirituality, of which we know very little.

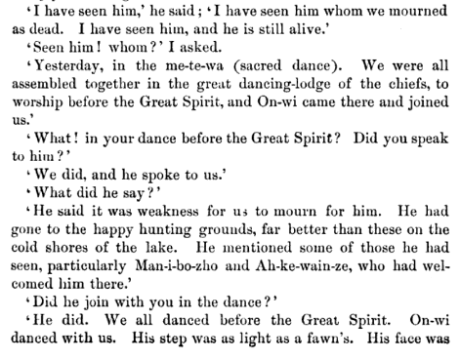

Therefore, I strongly considered leaving out this excerpt from FACTS Prove the Truth of Science, and we do not know by any other means any Truth; we, therefore, give the so-called Facts of our Contributors to prove the Intellectual Part of Man to be Immortal. From what I can tell, this bizarre 1883 publication is dedicated to stories of “Spiritualism,” the popular late 19th-century pseudoscience (think the earliest Ouija boards, Rasputin, etc.). If you haven’t already guessed from the the length of the title, FACTS… appears to have been pretty fringe even for its own time. Take it for what it is.

Florantha (above) and Granville Sproat were more than just teachers with funny names. They wrote about 1840s La Pointe. The sex scandal that led to their departure sent a ripple through the Protestant mission community. (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Granville Sproat, however, was a real person–a schoolteacher in the Protestant mission at La Pointe. His wife, Florantha, is quoted near the top of this post, referencing the death of Chief Buffalo’s sons. The Sproats’ impact on this area’s history is pretty minimal, though they did produce a fair amount of writing in the late 1830s and early ’40s. Perhaps the most interesting part of their Chequamegon story is their abrupt departure from the Island after Granville became embroiled in what I believe is Madeline Island’s earliest recorded gay sex scandal. Since I can’t end on that cliff hanger, and it might be several years before I get to that particular story, you can learn more from Bob Mackreth’s thorough and informative treatment of Florantha’s life on youtube.

This post has really gone off the rails. Thanks for sticking with it, and as always, thanks for reading. ~LF

Special thanks to Theresa, Patricia, and Stephane for making this post possible.

Blackbird’s Speech at the 1855 Payment

January 20, 2014

“We sold our land for our graves–that we might have a home, where the bones of our fathers are buried. We were not willing to sell the ashes of our relatives which are so dear to us. This was the reason why we sold our lands. It was not to pay debts over and over again, but to benefit the living, those of us who yet remain upon earth, our young men & women & children.”

~Makade-binesi (Blackbird)

Scene at Indian Payment–Odanah, Wis. This image is from a later payment than the one described below (Whitney & Zimmerman c.1870)

Most of us have heard Chief Joseph’s “Fight No More Forever” speech and Chief Seattle’s largely-fictional plea for the environment, but very few will know that a outstanding example of Native American oratory took place right here in the Chequamegon Region in the summer of 1855.

It was exactly eleven months after the Lake Superior Ojibwe bands gave up the Arrowhead region of Minnesota, in their final treaty with the United States, in exchange for permanent reservations. Already, the American government was trying to back out of a key provision of the agreement. It concerned a clause in Article Four of the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe that reads:

The United States will also pay the further sum of ninety thousand dollars, as the chiefs in open council may direct, to enable them to meet their present just engagements.

The inclusion of clauses to pay off trade debts was nothing new in Ojibwe treaties. In 1837, $70,000 went to pay off debts, and in 1842 another $75,000 went to the traders. Personal debts would often be paid out of annuity funds by the government directly to the creditors and certain Ojibwe families would never see their money. However, from the beginning there were accusations that these debts were inflated or illegitimate, and that it was the traders rather than the Ojibwe themselves, who profited from the sale of the lands. Therefore, in 1854, when $90,000 in claims were inserted in the treaty, the chiefs demanded that they be the ones to address the claims of the creditors.

However, less than a year later, at the first post-1854 payment, the government was pressured to back off of the language in the treaty. George Manypenny, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, came to La Pointe to oversee the payment where he was asked by Indian Agent Henry Gilbert to let the Agency oversee the disbursement of the $90,000. Most white inhabitants, and many of the white tourists in town to view the spectacle that was the 1855 payment, supported the agent’s plan, as did most of the mix-blooded Ojibwe (most of whom were employed in the trading business in one way or another) and a substantial minority of the full-bloods.

However, the clear majority of the Lake Superior chiefs insisted they keep the right to handle their own debt claims. As we saw in this post, the Odanah-based missionary Leonard Wheeler also felt the Government needed to honor its treaties to the letter. This larger faction of Ojibwe rallied around one chief. He was from the La Pointe Band and was entrusted to speak for Ojibwe with one voice. From this description, you might assume it was Chief Buffalo. However, Buffalo, in the final days of his life, found himself in the minority on this issue. The speaker for the majority was the Bad River chief Blackbird, and he may have delivered one of the greatest speeches ever given in the Chequamegon Bay region.

Unfortunately, the Ojibwe version of the speech has not survived, and it’s English version, originally translated by Paul Bealieu, exists in pieces recorded by multiple observers. None of these accounts captures all the nuances of the speech, so it is necessary to read all of them and then analyze the different passages to see its true brilliance.

The first reference to Blackbird’s speech I remember seeing appeared in the eyewitness account of Dr. Richard F. Morse of Detroit who visited La Pointe that summer specifically to see the payment. His article, The Chippewas of Lake Superior appeared in the third volume of the Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. As you’ll read, it doesn’t speak very highly of Blackbird or the speech, celebrating instead the oratory of Naaganab, the Fond du Lac chief who was part of the minority faction and something of a celebrity among the visiting whites in 1855:

From Morse’s clear bias against Ojibwe culture, I thought there may have been more to this story, but my suspicions weren’t confirmed until I transcribed another account of the payment for Chequamegon History. An Indian Payment written by another eyewitness, Crocket McElroy, paints a different picture of Blackbird and quotes part of his speech:

Paul H. Beaulieu translated the speeches at the 1855 annuity payment (Minnesota Historical Society Collections).

In August 1855 about three thousand Chippewa Indians gathered at the village of Lapointe, on Lapointe Island, Lake Superior, for an Indian Payment and also to hold a council with the commissioner of Indian affairs, who at that time was George W. Monypenny of Ohio. The Indians selected for their orator a chief named Blackbird, and the choice was a good one, as Blackbird held his own well in a long discussion with the commissioner. Blackbird was not one of the haughty style of Indians, but modest in his bearing, with a good command of language and a clear head. In his speeches he showed much ingenuity and ably pleaded the cause of his people. He spoke in Chippewa stopping frequently to give the interpreter time to translate what he said into English. In beginning his address he spoke substantially as follows:

“My great white father, we are pleased to meet you and have a talk with you We are friends and we want to remain friends. We expect to do what you want us to do, and we hope that you will deal kindly with us. We wish to remind you that we are the source from which you have derived all your riches. Our furs, our timber, our lands, everything that we have goes to you; even the gold out of which that chain was forged (pointing to a heavy watch chain that the commissioner carried) came from us, and now we hope that you will not use that chain to bind us.”

These conflicting accounts of the largely-unremembered Bad River chief’s speech made me curious, and after I found the Blackbird-Wheeler-Manypenny letters written after the payment, I knew I needed to learn more about the speech. Luckily, digging further into the Wheeler Papers uncovered the following. To my knowledge, this is the first time it has been transcribed or published in any form.

[Italics, line breaks, and quotation marks added by transcriber to clearly differentiate when Wheeler is quoting a speaker. Blackbird’s words are in blue.]

O-da-nah Jan 18, 1856.

L. H. Wheeler to Richard M. Smith

Dear Sir,

The following is the substance of my notes taken at the Indian council at La Pointe a copy of which you requested. Council held in front of Mr. Austrian’s store house Aug 30. 1855.

Short speech first from Kenistino of Lac du Flambeau.

My father, I have a little to say to you & to the Indians. There is no difference between myself and the other chiefs in regard to the subject upon which we wish to speak. Our chiefs and young men & old men & even the women & children are all of the same mind. Blackbird our chief will speak for us & express our sentiments.

The Commissioner, Col Manypenny replied as follows.

My children I suppose you have come to reply to what I said to you day before yesterday. Is this what you have come for?

“Ah;” or yes, was the reply.

I am happy to see you, but would suggest whether you had not better come tomorrow. It is now late in the day and is unpleasant & you have a great deal to say and will not have time to finish, but if you will come tomorrow we shall have time to hear all you have to say. Don’t you think this will be the best way?

“Ah!” yes was the response.

Think well about what you want to say and come prepared to speak freely & fully about all you wish to say. I would like not only to hear the chiefs and old men speak, but the young men talk, and even the women, if they wish to come, let them come and listen too. I want the women to understand all that is said and done. I understand that some of the Indians were drunk last night with the fire-water. I hope we shall hear nothing more of it. If any body gives you liquor let me know it and I will deal with him as he deserves. I hope we shall have a good time tomorrow and be able to explain all about your affairs.

Aug 31. Commissioner opened the council by saying that he wanted all to keep order.

Let the whites and others sit down on the ground and we will have a pleasant time. If you have anything to say I hope you will speak to the point.

Black Bird. To the Indians.

My brother chiefs, head men & young men & children. I have listened well to all the men & women & others who have spoken in our councils and shall now tell it to my father. I shall have but one mouth to speak your will.

Nose [noose (no-say) “my father”]. My father. We present you our salutations in your heart. We salute you in the name of our great father the President, whose representative you are. We want the Great Spirit now to bless us. The Day is clear, and we hope our thoughts will be clear too. My intention is to tell you what the owner of life has done for us. He has provided for the life of us all. When the Lord made us he provided for us here upon earth he invested it (ie, he made provision for our wants) in the running streams, in the woods & lakes which abound with fish and in the wild animals. We regard you as if men like a spirit, perhaps it is because of your education, because you are so much wiser than we, but if we can trace our tradition right the Great Spirit has not made the white man to cheat us. There is a difference of opinion as it regards different colors among, as to which shall have the preeminence, but the Great Spirit made us to be happy before you discovered us.

I will now tell you about how it was with us before our payments, and before we sold any land. Our furs that we took we sold to our traders. We were then paid 4 martin skins for a dollar. 4 bears skins also & 4 beaver skins for $1.00 too. Can you wonder that we are poor? I say this to show you what our condition was before we had any payments. I[t] was by our treaties that we learned the use of money. I see you White men that sit here how you are dressed. I see your watch chains & seals and your rich clothing. Now I will tell you how it is with our traders. When they first came among us they were very poor, but by & by they became very fat & rich, and wear rich clothing and had their watches & gold chains such as I see you wear. But they got their things out of us. They were made rich at our expense. My father, you told us to bring our women here too. Here they are, and now behold them in their poverty, and pity their condition (at this juncture in the speech several old women stood dressed in their worn out blankets and tattered garments as if designed to appeal to his humanity[)].

My father, I am now coming to the point. We are here to protect our own interests. Our land which we got from our forefathers is ours & we must get what we can for it. Our traders step between us & our father to controll our interests, and we have been imposed upon. Mr. Gilbert was the one I shook hands with last year when he was sent here to treat for our lands. He was the one who was sent to uphold us in our poverty. We are thankful to see you both here to attend to our interests, and that we are permitted to express to you our wants. Last year you came here to treat for our lands we are now speaking about. We sold them because we were poor. We thank our father for bringing clothing to pay for them. We sold our land for our graves–that we might have a home, where the bones of our fathers are buried. We were not willing to sell the ashes of our relatives which are so dear to us. This was the reason why we sold our lands. It was not to pay debts over and over again, but to benefit the living, those of us who yet remain upon earth, our young men & women & children.

You said you wanted to see them. They have been sent for and are now here. Behold them in their poverty & see how poor they look.

They are poor because so much of our money is taken to pay old debts. We want the 90,000 dollars to be paid as we direct. We know that it is just and right that it should be so. We want to have the money paid in our own hands, and we will see that our just debts are paid. We want the 90,000 to feed our poor women, and after paying our just debts we want the remainder to buy what we want. This is the will of all present. The chiefs, & young men & old men & the women & children.

Let what I have now said, my father, enter your head & heart; and let it enter the head of our great father the President, that it may be as we have now said. We own no more land. We must hereafter provide for ourselves. We want to profit by all the provisions of the treaty we have now made. We want the whole annuity paid to us as stipulated in the treaty. I am now done. After you have spoken, perhaps there are others who would like to speak.

This is the first time my father that I have appeared dressed in a coat & pants & I must confess I feel a little awkward.

The Commissioner replied as follows

We have all heard & noted down what you have said. If any others wish to speak they had better speak first and I will reply to all at once.

The Grand Portage Indian [Adikoons] then spoke as follows.

My father, I have a few words to say, and I wish to speak what I think. We have long coveted the privilege of seeing our Great Father. Why not now embrace the opportunity to speak freely while he is here? This man will speak my mind. He is old enough to speak and is a man endowed with good sense. He will speak our minds without reserve.

When we look around us, we think of our God who is the maker of us all. You have come here with the laws of that God we have talked about, and you profess to be a Christian and acknowledge the authority of God. The word of God ought to be obeyed not only by the Indians, but by all. When we see you, we think you must respect that word of God, who gives life to all. Your advice is like the law of God. Those who listen to his law are like God–firm as a rock, (not fickle and vacilating). When the word of the Great Spirit ends. When there is an end to life, we are all pleased with the advice you have given us, and intend to act in accord with it. If we are one here, and keep the word of the Great Spirit we shall be one here after. In what Blackbird said he expressed the mind of a majority of the chiefs now present. We wish the stipulations of the treaty to be carried out to the very letter.

I wish to say our word about our reserves. Will these reserves made for each of our bands, be our homes forever?

When we took credits of our trader last winter, and took no furs to pay him, and wish to get hold of this 90,000 dollars, that we may pay him off of that. This is all we came here for. We want the money in our own hands & we will pay our own traders. We do not think it is right to pay what we do not owe. I always know how I stand my acct. and we can pay our own debts. From what I have now said I do not want you to think that we want the money to cheat our creditors, but to do justice to them I owe. I have my trader & know how much I owe him, & if the money is paid into the hands of the Indians we can pay our own debts.

Naganub.

We have 90,000 dollars set apart to pay our traders, for my part I think it is just that the money should go for this object. We all know that the traders help us. We could not well do without them.

Buffalo.

We who live here are ready to pay our just debts. Some have used expressions as though these debts were not just. I have lived here many years and been very poor. There are some here who have been pleased to assist me in my poverty. They have had pity on me. Those we justly owe I don’t think ought to be defrauded. The trader feeds our women & children. We cannot live one winter without him. This is all I have to say.

[Wheeler does not identify a new speaker here, but marks a a star (right). Kohl (below) attributes the line about the “came out of the water” to Blackbird, but the line about the copper diggings contradicts Blackbird’s earlier statement, in Kohl, about not knowing their value. This, and Wheeler’s marking of Blackbird as the one who spoke after this speech would indicate this is Buffalo still talking].

[Wheeler does not identify a new speaker here, but marks a a star (right). Kohl (below) attributes the line about the “came out of the water” to Blackbird, but the line about the copper diggings contradicts Blackbird’s earlier statement, in Kohl, about not knowing their value. This, and Wheeler’s marking of Blackbird as the one who spoke after this speech would indicate this is Buffalo still talking].

Our rights ought to be protected. When commissioners have come here to treat for our lands, we have always listened well to their words. Not because we did not know ourselves the worth of our lands. We have noticed the ancient copper diggings, and know their worth. We have never refused to listen to the words of our Great Father. He it is true has had the power but we have made him rich. The traders have always wanted pay for what we do not remember to have bought. At Crow [W]ing River when our lands were ceded there, then there was a large sum demanded to pay old debts. We have always paid our traders we have acted fair on our part. At St. Peters also there was a large amount of old debts to be paid–many of them came from places unknown–for what I know they came out of the water. We think many of them came out of the same bag, and are many of them paid over & over again at every treaty.

Black Bird.

I get up no[w] to finish what you have put into my heart. The night would be heavy on my breast should I retain any of the words of them with whom I have councilled & for whom I speak. I speak no[w] of farmers, carpenters, & other employees of Govt. Where is the money gone to for them? We have not had these laborers for several years that has been appropriated. Where is the money that has been set apart to pay them? You will not probably see your Red Children again in after years to council with them. So we protest by the present opportunity to speak to you of our wants & grievances. We regard you as standing in the place of our great father at Washington, and your judgement must be correct. This is all I have to say about our arrearages, we have not two tongues.

As exciting as it was to have the full speech, as I transcribed some of the passages, some of them seemed very familiar. Sure enough, on page 53 of Johann Georg Kohl’s Kitchi-Gami: Life Among the Lake Superior Ojibway, there is another whole version. Kitchi-Gami is one of the standards of Ojibwe cultural history, and I use it for reference fairly often, but it had been so long since I had read the book cover to cover that I forgot that Kohl had been another witness that August day in 1855:

When one considers that Paul Beaulieu, the man giving the official English translation was probably speaking in his third language, after Ojibwe and Metis-French, and that Kohl was a native German speaker who understood English but may have been relying on his own mix-blood translator, it is remarkable how similar these two accounts are. This makes the parts where they differ all the more fascinating. Undoubtedly there are key parts of this speech that we could only understand if we had the original Ojibwe version and a full understanding of the complicated artistry of Ojibwe rhetoric with all its symbolism and metaphor. Even so, there are enough outstanding passages here for me to call it a great speech.

“My father…great Father…We regard you as if men like a spirit, perhaps it is because of your education, because you are so much wiser than we…”

The ritual language of kinship and humility in traditional Ojibwe rhetoric can be off-putting to those who haven’t read many Ojibwe speeches, and can be mistaken as by-product of American arrogance and paternalism toward Native people. However, the language of “My Father” predates the Americans, going all the way back to New France, and does not necessarily indicate any sort weakness or submission on the part of the speaker. Richard White, Michael Witgen, and Howard Paap, much smarter men than I, have dedicated pages to what Paap calls “fur-trade theater,” so I won’t spend too much time on it other than to say that 1855 was indeed a low point in Ojibwe power, but Blackbird is only acting the ritual part of the submissive child here in a long-running play. He is not grovelling.

On the contrary, I think Blackbird is playing Manypenny here a little bit. George Manypenny’s rise to the head of Indian Affairs coincided with the end of American removal policy and the ushering in of the reservation era. In the short term, this was to the political advantage of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. In Manypenny the Ojibwe got a “Father” who would allow them to stay in their homelands, but they also got a zealous believer in the superiority of white culture who wanted to exterminate Indian cultures as quickly as possible.

In a future post about the 1855 treaty negotiations with the Minnesota Ojibwe we will see how Commissioner Manypenny viewed the Ojibwe, including masterful politicians like Flat Mouth and Hole in the Day, as having the intelligence of children. Blackbird shows himself a a savvy politician here by playing into these prejudices as a way to get the Commissioner off his guard. Other parts of the speech lead me to doubt that Blackbird sincerely believed that the Americans were “so much wiser” than he was.

My intention is to tell you what the owner of life has done for us. He has provided for the life of us all. When the Lord made us he provided for us here upon earth he invested it (ie, he made provision for our wants) in the running streams, in the woods & lakes which abound with fish and in the wild animals… There is a Great Spirit from whom all good things here on earth come. He has given them to mankind–to the white as to the red man; for He sees no distinction of colour…but if we can trace our tradition right the Great Spirit has not made the white man to cheat us. There is a difference of opinion as it regards different colors among, as to which shall have the preeminence, but the Great Spirit made us to be happy before you discovered us…

This part varies slightly between Wheeler and Kohl, but in both it is very eloquent and similar in style to many Ojibwe speeches of the time. One item that piqued my interest was the line about the “difference of opinion.” Many Americans at the time understood the expansion of the United States and the dispossession of Native peoples in religious terms. It was Manifest Destiny. The Ojibwe also sought answers for their hardships in prophecy. On pages 117 and 118 of History of the Ojibwe People, William Warren relates the following:

Warren, writing in the late 1840s and early 1850s, contrasts this tradition with the popularity of the prophecies of Tenskwatawa, brother of Tecumseh, in Ojibwe country forty years earlier. Tenskwatawa taught that Indians would inherit North America and drive whites from the continent. Blackbird seems to be suggesting that in 1855 this question of prophecy was not settled among the Lake Superior Ojibwe. Presumably there would have been fertile ground for a charismatic millenarian Native spiritual leader along the lines of Neolin, Tenskwatawa, or Wovoka to gain adherents among the Lake Superior Ojibwe at that time.

Johann Georg Kohl recorded Blackbird’s speech in his well known account of Lake Superior in the Summer of 1855, Kitchi-Gami: Life Among the Lake Superior Ojibway.

Our furs, our timber, our lands, everything that we have goes to you; even the gold out of which that chain was forged…Now I will tell you how it is with our traders. When they first came among us they were very poor, but by & by they became very fat & rich, and wear rich clothing and had their watches & gold chains such as I see you wear. But they got their things out of us. They were made rich at our expense…and now we hope that you will not use that chain to bind us…

The gold chain appears in each of McElroy, Wheeler, and Kohl’s accounts. It acts as a symbol on multiple levels. To Blackbird, the gold represents the immense wealth produced during the fur trade on the backs of Indian trappers. By 1855, with the fur trade on its last legs, some of the traders are very wealthy while the Ojibwe are much poorer than they were when the trade started. The gold also stands in for the value of the ceded territory itself, specifically the lakeshore lands (ceded in 1842), which thirteen years later were producing immense riches from that other shiny metal, copper. Finally, in McElroy’s account, we also see the chain acting as the familiar symbol of bondage.

…We sold our land for our graves–that we might have a home, where the bones of our fathers are buried…Our debts we will pay. But our land we will keep. As we have already given away so much, we will, at least, keep that land you have left us, and which is reserved for us. Answer us, if thou canst, this question. Assure us, if thou canst, that this piece of land reserved for us, will really always be left to us…

This passage of Blackbird’s speech, and a similar statement by the “Grand Portage Indian” (identified by Morse as Adikoons or Little Caribou), indicate that perhaps, the actual disbursement of the $90,000 was a secondary to the need to hold Agent Gilbert and the Government to their word. It was very important to the Ojibwe that words of the Treaty of 1854 be rock-solid, not for a need to pay off debts or to get annuity payments, but because the Government absolutely needed to keep its promise to grant reservations around the ancestral villages. The memory of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, less than five years earlier, cast a long shadow over this decade. Paap argues in Red Cliff, Wisconsin that the singular goal of the treaty, from the Ojibwe perspective, was to end the removal talk forever, a goal that had seemingly been accomplished. To hear the Government trying to weasel out of a provision of the 1854 Treaty must have been very frightening to those who heard Robert Stuart’s promises in 1842. This time, the chiefs had to make sure a promise of a permanent homeland for their people wouldn’t turn out to be another lie.

This is the first time my father that I have appeared dressed in a coat & pants & I must confess I feel a little awkward.

You can argue that a great speech can’t end with the line, “I must confess I feel a little awkward.” However, I will argue that this might be the best line of all. It is another example of the political brilliance of Blackbird. The Bad River chief knew who his allies were, knew who his opponents were, and knew how to take advantage of the Commissioner’s prejudices. Clothing played a role in all of this.

George Manypenny despised Indian cultures. In fact, the whole council had almost derailed a few days before the speeches when the Commissioner refused to smoke the pipe presented to him by the chiefs in open ceremony. He remedied this insult somewhat by smoking it later while indoors, but he let it be known that he had no use for Ojibwe songs, dances, rituals or clothing. This put Blackbird, an unapologetic traditionalist and practitioner of the midewiwin at a distinct disadvantage, when compared with chiefs like Naaganab who were known to wear European clothes and profess to be Christians.

Although he had the majority of the people behind him, Blackbird had very little negotiating power. He had to persuade Manypenny that he was in the right. He had no chance unless he could appear to the Commissioner that he was trying to become “civilized” and was therefore worthy enough to be listened to. However, by wearing European clothes, he ran the risk of alienating the majority of the people in the crowd who preferred traditional ways and dress. Furthermore, the chiefs most likely to oppose him, Naaganab and Jayjigwyong (Little Buffalo) had been dressing like whites (I would argue also largely for political reasons) for years and were much more likely to come across as “civilized” in the Commissioner’s eyes.

How did the chief solve these dilemmas? In the same way he turned Manypenny’s request to see the Ojibwe women to his advantage, he used the clothing to demonstrate that he had gone out of his way to work with the Commissioner’s wishes, while still solidifying the backing of the traditional Ojibwe majority and putting his opponents on the defensive all with one well-timed joke. Although this joke seems to have gone over Wheeler’s head, and likely Manypenny’s as well, Kohl’s mention of the “applauding laughter of the entire assembly,” shows it reached its target audience. So, contrary to first appearances, the crack about the awkward pants is anything but an awkward ending to this speech.

Conclusion

In the 1840s and early 1850s, Blackbird rarely appears in the historical record. Here and there he is mentioned as a second chief to Chief Buffalo or as leading the village at Bad River. Many mentions of him by English-speaking authors are negative. He is referred to as a rascal, scoundrel, or worse, and I’ve yet to find any mention of his father or other family members as being prominent chiefs.

However, in the late 1850s and early 1860s, he was clearly the most important speaker for not just the La Pointe Band, but for the other Lake Superior Bands as well. This was a mystery to me. I temporarily hypothesized his rise was due to the fact that Chequamegon was seen as the center of the nation and that when Buffalo died, Blackbird succeeded to the position by default. However, this view doesn’t really fit what I understood as Ojibwe leadership.

This speech puts that interpretation to rest. Blackbird earned his position by merit and by the will of the people.

He did not, however, win on the question of the $90,000. A Chequamegon History reader recently sent me a document showing it was eventually paid to the creditors directly by the Agent. However, if my argument is correct, the more important issue was that the Government keep its word that the reservations would belong to the Ojibwe forever. The land question wasn’t settled overnight, and it required many leaders over the last 160 years to hold the United States to its word. But today, Blackbird’s descendants still live beside the swamps of Mashkiziibii at least partially because of the determination of their great ogimaa.

Sources:

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings round Lake Superior. London: Chapman and Hall, 1860. Print.

McClurken, James M., and Charles E. Cleland. Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights / James M. McClurken, Compiler ; with Charles E. Cleland … [et Al.]. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State UP, 2000. Print.

McElroy, Crocket. “An Indian Payment.” Americana v.5. American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. The Voice of the Crane Echoes Afar: The Sociopolitical Organization of the Lake Superior Ojibwa, 1640-1855. New York: Garland Pub.,1997. Print.

—————— William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1991. Print.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.

This post is on of several that seeks to determine how many images exist of Great Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855. To learn why this is necessary, read this post introducing the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

Today’s post looks at two paintings from the 1820s of Ojibwe men named Bizhiki (Buffalo). The originals are lost forever, but the images still exist in the lithographs that follow.

Pee-che-kir: A Chippewa Chief Lithograph from McKenney and Hall’s History of the Indian Tribes of North America based on destroyed original by Charles Bird King; 1824. (Wikimedia Images)

Pe-shick-ee: A Celebrated Chippeway Chief from the Aboriginal Port-Folio by James Otto Lewis. The original painting was done by Lewis at Prairie du Chien or Fond du Lac of Lake Superior in 1825 or 1826 (Wisconsin Historical Society).

1824 Delegation to Washington

Chronologically, the first known image to show an Ojibwe chief named Buffalo appeared in the mid-1820s at time when the Ojibwe and the United States government were still getting to know each other. Prior to the 1820s, the Americans viewed the Ojibwe as a large and powerful nation. They had an uncomfortably close history with the British, who were till lurking over the border in Canada, but they otherwise inhabited a remote country unfit for white settlement. To the Ojibwe, the Americans were chimookomaan, “long knives,” in reference to the swords carried by the military officers who were the first Americans to come into their country. It was one of these long knives, Thomas McKenney, who set in motion the gathering of hundreds of paintings of Indians. Two of these showed men named Buffalo (Bizhiki).

Charles Bird King: Self portrait 1815 (Wikimedia Images)

McKenney was appointed the first Superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1824. Indian Affairs was under the Department of War at that time, and McKenneyʼs men in the West were mostly soldiers. He, like many in his day, believed that the Indian nations of North America were destined for extinction within a matter of decades. To preserve a record of these peoples, he commissioned over 100 portraits of various Indian delegates who came to Washington from all over the U.S. states and territories. Most of the painting work fell to Charles Bird King, a skilled Washington portrait artist. Beginning in 1822, King painted Indian portraits for two decades. He would paint famous men like Black Hawk, Red Jacket, Joseph Brandt, and Major Ridge, but Kingʼs primary goal was not to record the stories of important individuals so much as it was to capture the look of a vanishing race.

No-tin copied from 1824 Charles Bird King original by Henry Inman. Noodin (Wind) was a prominent chief from the St. Croix country. King’s painting of Buffalo from St. Croix was probably also copied by Inman, but its location is unknown (Wikimedia Images).

In July of 1824, William Clark, the famous companion of Meriwether Lewis, brought a delegation of Sauks, Foxes, and Ioways to Washington to negotiate land cessions. Lawrence Taliaferro, the Indian agent at Fort St. Anthony (now Minneapolis), brought representatives of the Sioux, Menominee, and Ojibwe to observe the treaty process. The St. Croix chiefs Buffalo and Noodin (Wind) represented the Ojibwe.

Charles Bird King painted portraits of most of the Indians listed here in the the 1824 Washington group by Niles’ Weekly Register, July 31, 1824. (Google Books)

The St. Croix chiefs were treated well: taken to shows, and to visit the sights of the eastern cities. However, there was a more sinister motivation behind the governmentʼs actions. McKenney made sure the chiefs saw the size and scope of the U.S. Military facilities in Washington, the unspoken message being that resistance to American expansion was impossible. This message seems to have resonated with Buffalo and Noodin of St. Croix as it is referred to repeatedly in the official record. McKenney pointed Buffalo out as a witness to American power at the Treaty of Fond du Lac (1826). Schoolcraft and Allen mention Buffalo’s trip in their own ill-fated journey up the St. Croix in 1832 (see it in this post), and Noodin talks about the soldiers he saw in Washington in the treaty deliberations in the 1837 Treaty of St. Peters.

While in Washington, Buffalo, Noodin, and most of the other Indians in the group sat with King for portraits in oil. Buffalo was shown wearing a white shirt and cloak, holding a pipe, with his face painted red. The paintings were hung in the offices of the Department of War, and the chiefs returned to their villages.

James Otto Lewis

The following summer, St. Croix Buffalo and Noodin joined chiefs from villages throughout the Ojibwe country, as well as from the Sioux, Sac and Fox, Menominee, Ho-Chunk, Ioway, Ottawa, and Potawatomi at Prairie du Chien. The Americans had called them there to sign a treaty to establish firm borders between their nations. The stated goal was to end the wars between the Sioux and Ojibwe, but it also provided the government an opportunity to assert its authority over the country and to set the stage for future land cessions.

McKenney did not attend the Treaty of Prairie du Chien leaving it to Clark and Lewis Cass to act as commissioners. A quick scan of the Ojibwe signatories shows “Pee-see- ker or buffalo, St. Croix Band,” toward the bottom. Looking up to the third signature, we see “Gitspee Waskee, or le boeuf of la pointe lake Superior,” so both the St. Croix and La Pointe Buffalos were present among the dozens of signatures. One of the government witnesses listed was an artist from Philadelphia named James Otto Lewis. Over the several days of negotiation, Lewis painted scenes of the treaty grounds as well as portraits of various chiefs. These were sent back to Washington, some were copied and improved by King or other artists, and they were added to the collection of the War Department.

The following year, 1826, McKenney himself traveled to Fond du Lac at the western end of Lake Superior to make a new treaty with the Ojibwe concerning mineral exploration on the south shore. Lewis accompanied him and continued to create images. At some point in these two years, a Lewis portrait of an Ojibwe chief named Pe-schick-ee (Bizhiki) appeared in McKenneyʼs growing War Department collection.

Lithographs

By 1830, McKenney had been dismissed from his position and turned his attention to publishing a portfolio of lithographs from the paintings in the War Department collection. Hoping to cash in his own paintings by beating McKenney to the lithograph market, Lewis released The Aboriginal Port Folio in May of 1835. It included 72 color plates, one of which was Pe-schick-ee: A Celebrated Chippeway Chief.

Pencil sketch of Pee-che-kir by Charles Bird King. King made these sketches after his original paintings to assist in making copies. (Herman J. Viola, The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King.)

Due to financial issues The History of the Indian Tribes of North America, by McKenney with James Hall, would not come out in full release until the mid 1840s. The three-volume work became a bestseller and included color plates of 120 Indians, 95 of which are accompanied by short biographies. Most of the lithographs were derived from works by King, but some were from Lewis and other artists. Kingʼs portrait of Pee-Che-Kir: A Chippewa Chief was included among them, unfortunately without a biography. However, we know its source as the painting of the St. Croix Buffalo in 1824. Noodin and several others from that delegation also made it into lithograph form. The original War Department paintings, including both Pee-Che-Kir and Pe-schick-ee were sent to the Smithsonian, where they were destroyed in a fire in 1858. Oil copies of some of the originals, including Henry Inmanʼs copy of Kingʼs portrait of Noodin, survive, but the lithographs remain the only known versions of the Buffalo portraits other than a pencil sketch of the head of Pee-Che-Kir done by King.

The man in the Lewis lithograph is difficult to identify. The only potential clue we get from the image itself is the title of “A Celebrated Chippeway Chief,” and information that it was painted at Prairie du Chien in 1825. To many, “celebrated” would indicate Buffalo from La Pointe, but in 1825, he was largely unknown to the Americans while the St. Croix Buffalo had been to Washington. In the 1820s, La Pointe Buffaloʼs stature was nowhere near what it would become. However, he was a noted speaker from a prominent family and his signature is featured prominently in the treaty. Any assumptions about which chief was more “celebrated” are difficult.

In dress and pose, the man painted by Lewis resembles the King portrait of St. Croix Buffalo. This has caused some to claim that the Lewis is simply the original version of the King. King did copy and improve several of Lewisʼ works, but the copies tended to preserve in some degree the grotesque, almost cartoonish, facial features that are characteristic of the self-taught Lewis (see this post for another Lewis portrait). The classically-trained King painted highly realistic faces, and side-by-side comparison of the lithographs shows very little facial resemblance between Kingʼs Pee-Che-Kir and Lewisʼ Pe-schick-ee.

Thomas L. McKenney painted in 1856 by Charles Loring Elliott (Wikimedia Images)

Of the 147 War Department Indian portraits cataloged by William J. Rhees of the Smithsonian prior to the fire, 26 are described as being painted by “King from Lewis,” all of which are from 1826 or after. Most of the rest are attributed solely to King. Almost all the members of the 1824 trip to Washington are represented in the catalog. “Pee-che-ker, Buffalo, Chief of the Chippeways.” does not have an artist listed, but Noodin and several of the others from the 1824 group are listed as King, and it is safe to assume Buffalo’s should be as well. The published lithograph of Pee-che-kir was attributed solely to King, and not “King from Lewis” as others are. This further suggests that the two Buffalo lithographs are separate portraits from separate sittings, and potentially of separate chiefs.

Even without all this evidence, we can be confident that the King is not a copy of the Lewis because the King portrait was painted in 1824, and the Lewis was painted no earlier than 1825. There is, however, some debate about when the Lewis was painted. From the historical record, we know that Lewis was present at both Prairie du Chien and Fond du Lac along with both the La Pointe Buffalo and the St. Croix Buffalo. When Pe- schick-ee was released, Lewis identified it as being painted at Prairie du Chien. However, the work has also been placed at Fond du Lac.

The modern identification of Pee-che-kir as a copy of Pe-schick-ee seems to have originated with the work of James D. Horan. In his 1972 book, The McKenney-Hall Portrait Gallery of American Indians, he reproduces all the images from History of the Indian Tribes, and adds his own analysis. On page 206, he describes the King portrait of Pee-che-kir with:

“Peechekir (or Peechekor, Buffalo) was “a solid, straight formed Indian,” Colonel McKenney recalled many years after the Fond du Lac treaty where he had met the chief. Apparently the Chippewa played a minor role at the council.

Original by James Otto Lewis, Fond du Lac council, 1826, later copied in Washington by Charles Bird King.”

Presumably, the original he refers to would be the Lewis portrait of Pe-schick-ee. However, Horanʼs statement that McKenney met St. Croix Buffalo at Fond du Lac is false. As we already know, the two men met in 1824 in Washington. It is puzzling how Horan did not know this considering he includes the following account on page 68:

The first Indian to step out of the closely packed lines of stone-faced red men made McKenney feel at home; it was a chief he had met a few years before in Washington. The Indian held up his hand in a sign of peace and called out:

“Washigton [sic]… Washington… McKenney shook hands with the chief and nodded to Lewis but the artist had already started to sketch.”

McKenneyʼs original account identifies this chief as none other than St. Croix Buffalo:

In half an hour after, another band came in who commenced, as did the others, by shaking hands, followed, of course, by smoking. In this second band I recognized Pee-che-kee, or rather he recognized me–a chief who had been at Washington, and whose likeness hangs in my office there. I noticed that his eye was upon me, and that he smiled, and was busily employed speaking to an Indian who sat beside him, and no doubt about me. His first word on coming up to speak to me was, “Washington”–pointing to the east. The substance of his address was, that he was glad to see me–he felt his heart jump when he first saw me–it made him think of Washington, of his great father, of the good living he had when he visited us–how kind we all were to him, and that he should never forget any of it.

From this, Horan should have known not only that the two men knew each other, but also that a portrait of the chief (Kingʼs) already was part of the War Department collection and therefore existed before the Lewis portrait. Horanʼs description of Lewis already beginning his sketch does not appear in McKenneyʼs account and seems to invented. This is not the only instance where Horan confuses facts or takes wide license with Ojibwe history. His statement quoted above that the Ojibwe “played a minor role” in the Treaty of Fond du Lac, when they were the only Indian nation present and greatly outnumbered the Americans, should disqualify Horan from being treated as any kind of authority on the topic. However, he is not the only one to place the Lewis portrait of Pe-schick-ee at Fond du Lac rather than Prairie du Chien.

Between, 1835 and 1838 Lewis released 80 lithographs, mostly of individual Indians, in a set of ten installments. He had intended to include an eleventh with biographies. However, a dispute with the publisher prevented the final installment from coming out immediately. His London edition, released in 1844 by another publisher, included a few short biographies but none for Pe-schick-ee. Most scholars assumed that he never released the promised eleventh installment. However, one copy of a self-published 1850 pamphlet donated by Lewisʼs grandson exists in the Free Library of Philadelphia. In it are the remaining biographies. Number 30 reads:

No. 30. Pe-shisk-Kee. A Chippewa warrior from Lake Huron, noted for his attachment to the British, with whom he always sided. At the treaty held at Fond du Lac, when the Council opened, he appeared with a British medal of George the III. on his breast, and carrying a British flag, which Gen. Cass, one of the Commissioners, promptly and indignantly placed under his feet, and pointing to the stars and stripes, floating above them, informed him that that was the only one permitted to wave there.

The Chief haughtily refused to participate in the business of the Council, until, by gifts, he became partly conciliated, when he joined in their deliberations. Painted at Fond du Lac, in 1826.

This new evidence further clouds the story. Initially, this description does not seem to fit what we know about either the La Pointe or the St. Croix Buffalo, as both were born near Lake Superior and lived in Wisconsin. Both men were also inclined to be friendly toward the American government. The St. Croix Buffalo had recently been to Washington, and the La Pointe Buffalo frequently spoke of his desire for good relations with the United States in later years. It is also troubling that Lewis contradicts his earlier identification of the location of the portrait at Prairie du Chien.

It is unlikely that Pe-schick-ee depicts a third chief given that no men named Buffalo other than the two mentioned signed the Treaty of Fond du Lac, and the far-eastern bands of Ojibwe from Lake Huron were not part of treaty councils with the Lake Superior bands. One can speculate that perhaps Lewis, writing 25 years after the original painting, mistook the story of Pe-schick-ee with that one of the many other chiefs he met in his travels, but there are some suggestions that it might, in fact, be La Pointe Buffalo.

The La Pointe Band traded with the British in the other side of Lake Superior for years after the War of 1812 supposedly confirmed Chequamegon as American territory. If you’ve read this post, you’ll know that Buffalo from La Pointe was a follower of Tenskwatawa, whose brother Tecumseh fought beside the British. On July 22, 1822, Schoolcraft writes:

At that place [Chequamegon] lived, in comparatively modern times, Wabojeeg and Andaigweos, and there still lives one of their descendants in Gitchee Waishkee, the Great First-born, or, as he is familiarly called, Pezhickee, or the Buffalo, a chief decorated with British insignia. His band is estimated at one hundred and eighteen souls, of whom thirty-four are adult males, forty-one females, and forty-three children.

It’s possible that it was La Pointe Buffalo with the British flag. Archival research into the Treaty of Fond du Lac could potentially clear this up. If I stumble across any, I’ll be sure to add it here. For now, we can’t say one way or the other which Buffalo is in the Lewis portrait.

The Verdict

Not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe: This is Chief Buffalo from St. Croix.

Inconclusive: This could be Buffalo from La Pointe or Buffalo from St. Croix.

Sources:

Horan, James David, and Thomas Loraine McKenney. The McKenney-Hall Portrait Gallery of American Indians. New York, NY: Bramhall House, 1986. Print.

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 21 June 2012. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Lewis, James O., The Aboriginal Port-Folio: A Collection of Portraits of the Most Celebrated Chiefs of the North American Indians. Philadelphia: J.O. Lewis, 1835-1838. Print.

———– Catalogue of the Indian Gallery,. New York: J.O. Lewis, 1850. Print.

Loew, Patty. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal.

Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2001. Print.

McKenney, Thomas Loraine. Sketches of a Tour to the Lakes of the Character and Customs of the Chippeway Indians, and of Incidents Connected with the Treaty of Fond Du Lac. Baltimore: F. Lucas, Jun’r., 1827. Print.

McKenney, Thomas Loraine, and James Hall. Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of Ninety-five of 120 Principal Chiefs from the Indian Tribes of North America. Washington: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1967. Print.

Moore, Robert J. Native Americans: A Portrait : The Art and Travels of Charles Bird King, George Catlin, and Karl Bodmer. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1997. Print.

Niles, Hezekiah, William O. Niles, Jeremiah Hughes, and George Beatty, eds. “Indians.” Niles’ Weekly Register [Baltimore] 31 July 1824, Miscellaneous sec.: 363. Print.

Rhees, William J. An Account of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington: T. McGill, 1859. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi,. [East Lansing]: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers: With Brief Notices of Passing Events, Facts, and Opinions, A.D. 1812 to A.D. 1842. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and, 1851. Print.

Viola, Herman J. The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1976. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Special thanks to Theresa Schenck of the University of Wisconsin and Charles Lippert for helping me work through this information, and to Michael Edmonds of the Wisconsin Historical Society, and Alice Cornell (formerly of the University of Cincinnati) for tracking down the single copy of the unpublished James Otto Lewis catalog.

Chief Buffalo, Flat Mouth, and Tecumseh

April 28, 2013

The Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa painted by Charles Bird King c.1820 (Wikimedia Commons)

The Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa painted by Charles Bird King c.1820 (Wikimedia Commons)In contrast with other Great Lakes nations, the Lake Superior Ojibwe are often portrayed as not having had a role in the Seven Years War, Pontiac’s War, Tecumseh’s War, or the War of 1812. The Chequamegon Ojibwe are often characterized as being uniformly friendly toward whites, peacefully transitioning from the French and British to the American era. The Ojibwe leaders Buffalo of La Pointe and Flat Mouth of Leech Lake are seen as men who led their people into negotiations rather than battle with the United States.

No one tried harder to promote the idea of Ojibwe-American friendship than William W. Warren (1825-1853), the Madeline Island-born mix-blooded historian who wrote History of the Ojibway People. Warren details Ojibwe involvement in all of these late-18th and early 20th-century imperial conflicts, but then repeatedly dismisses it as solely the work of more easterly Ojibwe bands or a few rogue warriors. The reality was much more complicated.

It is true, the Lake Superior Ojibwe never entered into these wars as a single body, but the Lake Superior Ojibwe rarely did anything as a single body. Different bands, chiefs, and families pursued different policies. What is clear from digging deeper into the sources, however, is that the anti-American resistance ideologies of men like the Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa (The Prophet) had more followers around here than Warren would have you believe. The passage below, from none other than Warren himself, shows that these followers included Buffalo and Flat Mouth.

History of the Ojibway People is available free online, but I’m not going to link to it. I want you to check out or buy the second edition, edited and annotated by Theresa Schenck and published by the Minnesota Historical Society in 2009. It is not the edition I first read this story in, but this post does owe a great debt to Dr. Schenck’s footnotes. Also, if you get the book, you will find the added bonus of a second account of these same events from Julia Warren Spears, William’s sister (Appendix C). The passage that is reproduced here can be read on pages 227-231.

“… no event of any importance occured on the Chippeway and Wisconsin Rivers till the year 1808, when, under the influence of the excitement which the Shaw-nee prophet, brother of Tecumseh, succeeded in raising, even to the remotest village of the Ojibways, the men of the Lac Coutereille village, pillaged the trading house of Michel Cadotte at Lac Coutereilles, while under charge of a clerk named John Baptiste Corbin. From the lips of Mons. Corbin, who is still living at Lac Coutereille, at the advanced age of seventy-six years, and who has now been fifty-six years in the Ojibway country, I have obtained a reliable account of this transaction…”

“…In the year 1808, during the summer while John B. Corbin had charge of the Lac Coutereille post, messengers, whose faces were painted black, and whose actions appeared strange, arrived at the different principal villages of the Ojibways. In solemn councils they performed certain ceremonies, and told that the Great Spirit had at last condescended to hold communion with the red race, through the medium of a Shawano prophet, and that they had been sent to impart the glad tidings.