1838 more Petitions from La Pointe to the President

April 16, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs:

La Pointe Agency 1831-1839

National Archives Identifier: 164009310

O.I.A. Lapointe W.692.

Governor of Wisconsin

Mineral Pt. 15 Oct. 1838.

Encloses two communications

from D. P. Bushnell; one,

to speech of Jean B. DuBay, a half

breed Chippewa, delivered Aug. 15, ’38,

on behalf of the half breeds then assembled,

protesting against the decision

of the U.S. Court on the subject of the

murder of Alfred Aitkin by an Ind,

& again demanding the murderer;

with Mr Bushnell’s reply: the other,

dated 14 Aug. 1838, being a Report

in reference to the intermeddling of

any foreign Gov’t or its officers, with

the Ind’s within the limits of the U.S.

[Sentence in light text too faint to read]

12 April 1839.

Rec’d 17 Nov 1838.

See letter of 7 June 39 to Hon Lucius Lyon

Ans’d 12 April, 1839

W Ward

Superintendency of Indian Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point Oct 15, 1838.

Sir:

I have the honor to enclose herewith two communications from D. P. Bushnell Esq, Subagent of the Chippewas at La Pointe; the first, being the Speech of Jean B. DuBay, a half breed Chippewa, on behalf of the half-breeds assembled at La Pointe, on the 15th august last, in relation to the decision of the U.S. Court on the subject of the murder of Alfred Aitkin by an Indian; the last, in reference to the intermeddling of any foreign government, or the officers thereof, with the Indians within the limits of the United States.

Very respectfully

Your obed’t serv’t.

Henry Dodge

Sup’t Ind. Affs.

Hon. C. A. Harris

Com of Ind. Affairs.

D. P. Bushnell Aug. 14, 1838

W692

Subagency

La Pointe Aug 14th 1838

Sir

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your communication dated 7 ultimo enclosing an extract from a Resolution of the House of the Representatives of the 19th of March, 1838. No case of intermeddling by any foreign government on the officers, or subject thereof with the Indians under my charge or any others, directly , or indirectly, has come to my knowledge. It is believed that the English government has been in the Habit of distributing presents at a point on Lake Huron below Drummonds Island to the Chippewa for a series of years.

The Indians from this region, until recently, visited that place for their share of the annual distribution. But the Treaty made last summer between them and the United States, and the small distribution of presents that has been made within the Last Year, under the direction of our government, have had the effect to permit any of them from visiting, the English Territory this year. These Indians have generally manifested a desire to live upon terms of friendship with the American people. All of the Chiefs from the region of Lake Superior have expressed a desire to visit the seat of Gov’t where none of them have yet been. There is no doubt, but such a visit with the distribution of a few presents among them would be productive: of much good, and render their attachment to our Gov’t still stronger.

Very Resp’y

yr ms ob sev’t

D. P. Bushnell.

I. O. A.

To

His Excellency Henry Dodge

Ter, Wisconsin Sup’t Ind Affs

Half breed Speech

Speech of Jean B. DuBay,

a half breed Chippewa, on behalf of the half breeds assembled in a numerous body at the United States Sub Indian Agency office at La Pointe, on the 15th day of August 1838.

Father. We have come to you for the purpose of speaking on the subject of the murder that was committed two years ago by an Indian on one of our Brothers. I allude to Alfred Aitken. We have always considered ourselves Subject to the Laws of the United States and have consequently relied upon their protection. But it appears by the decision of the United Sates court in this case. “That it was an Indian Killed an Indian, on Indian ground, and died not therefore come under its jurisdiction,” that we have hitherto laboured under a delusion, and that a resort to the laws can avail nothing. We come therefore to you, at the agent of the Government here, to tell you that we have councilled with the Indians and, have declared to them and we have solemnly pledged ourselves in your presence, to each other, that we will enforce in the Indian Country, the Indian Law, Blood for Blood.

We pay taxes, and in the Indian Country are held amenable to the Laws, but appeal to them in vain for protection. Sir we will protect ourselves. We take the case into our own hands. Blood shall be shed! We will have justice and who can be answerable for the consequences? Our brother was a gentlemanly young man. He was educated at a Seminary in Louville in the State of New York. He was dear to us. We remember him as the companion of our childhood. The voice of his Blood now cries to us from the ground for vengence! But the stain left by his you shall be washed out by one of a deeper dye!

For injuries committed upon the persons or property of whites, although within the Indian Country we are still willing to be held responsible to the Laws of the United States, notwithstanding the decision of a United States Court that we are Indians. And for like injuries committed upon us by whites we will appeal to the same tribunal.

Sir our attachments to the American Government and people was great. But they have cast us off. The Half breeds muster strong on the northwestern frontier & we Know no distinction of tribes. In one thing at least we are all united. We might muster into the service of the United States in case of a war and officered by Americans would compose in frontier warfare a formidable corps. We can fight the Indian or white man, in his own manner, & would pledge ourselves to Keep peace among the different Indian tribes.

Sir we will do nothing rashly. We once more ask from your hands the murder of Mr. Aitken. We wish you to represent our case to the President and we promise to remain quiet for one year, giving ample time for his decision to be made Known. Let the Government extend its protection to us and we will be found its staunchest friends. If it persists in abandoning us the most painful consequences may ensue.

Sir we will listen to your reply, and shall be Happy to avail ourselves of your advice.

Reply of the Subagent.

My friends, I have lived several years on the frontier & have Known many half breeds. They have to my Knowledge paid taxes, & held offices under State, Territorial, and United States authorities, been treated in every respect by the Laws as American Citizens; and I have hitherto supposed they were entitled to the protection of the Laws. The decision of the court is this case, if court is a virtual acknowledgement of your title to the Indians as land, in common with the Indians & I see no other way for you to obtain satisfaction then to enforce the Indian Law. Indeed your own safety requires it. in the meantime I think the course you have adopted, in awaiting the results of this appeal is very proper, and cannot injure your cause although made in vain. At your request I will forward the words of your speaker, through the proper channel to the authorities at Washington. In the event of your being compelled to resort to the Indian mode of obtaining satisfaction it is to be hoped you will not wage an indiscriminate warfare. If you punish the guilty only, the Indians can have no cause for complaint, neither do I think they will complain. Any communication that may be made to me on this subject I will make Known to you in due time.

O.I.A. Lapointe. D.333.

Hon. Ja’s D. Doty.

New York. 25 March, 1839

Encloses Petition, dated

20 Dec. last, of Michel Nevou & 111

others, Chippewa Half Breeds, to the

President, complaining of the delay

in the payment of the sum granted

them, by Treaty of 29 July, 1837,

protesting against its payments on the

St Croix river, & praying that it be

paid at La Pointe on Lake Superior.

Recommends that the payment

be made at this latter place,

for reasons stated.

Rec’d 28 March, 1839.

Ans 29 Mch 1839.

(see over)

Mr Ward

D.100 3 Mch 28

Mch 38, 1839.

Indian Office.

The within may be

an [?] [?] [?] –

[guest?]. in fact will be

in accordance with [?]

[lat?] opinions and not of

the department.

W. Ward

New York

March 25, 1839

The Hon.

J.R. Pointsett

Secy of War

Sir,

I have the honour to submit to you a petition from the Half-breeds of the Chippewa Nation, which has just been received.

It must be obvious to you Sir, that the place from which the Indian Trade is prosecuted in the Country of that Nation is the proper place to collect the Half Breeds to receive their allowance under the Treaty. A very large number being employed by the Traders, if they are required to go to any other spot than La Pointe, they must lose their employment for the season. Three fourths of them visit La Pointe annually, in the course of the Trade. Very few either live or are employed on the St. Croix.

As an act of justice, and of humanity, to them I respectfully recommend that the payment be made to them under the Treaty at La Pointe.

I remain Sir, with very great respect

Your obedient Servant.

J D Doty

[D333-39.LA POINTE]

Hon.

J. D. Doty

March 29, 1839

Recorded in N 26

Page 192

[WD?] OIA

Mch 29, 1839

Sir

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 25th with the Petition of the Chippewa half breeds.

It is only necessary for me to observe his reply that it had been previously determined that the appropriation for them should be distributed at Lapointe, & the instructions with be given accordingly.

Very rcy

Hon.

J.D. Doty

New York

D100

D.333.

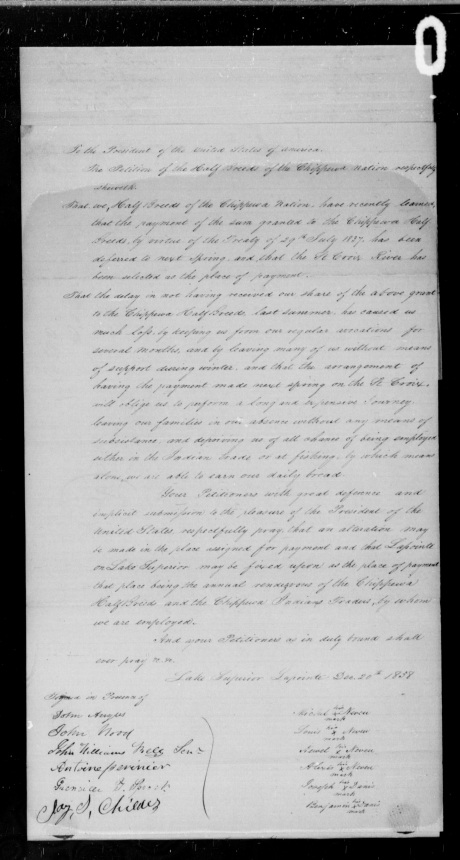

To the President of the United States of America

The Petition of the Half Breeds of the Chippewa nation respectfully shareth.

That we, Half Breeds of the Chippewa Nation, have recently learned, that the payment of the sum granted to the Chippewa Half Breeds, by virtue of the Treaty of 29th July 1837, has been deferred to next Spring, and, that the St Croix River has been selected as the place of payment.

That the delay in not having received our share of the above grant to the Chippewa Half Breeds, last summer, has caused us much loss, by keeping us from our regular vocations for several months, and by leaving many of us without means of support during winter, and that the arrangement of having the payment made next spring on the St Croix, will oblige us to perform a long and expensive Journey, leaving our families in our absence without any means of subsistance, and depriving us of all chance of being employed either in the Indian Trade or at fishing, by which means alone, we are able to earn our daily bread.

Your Petitioners with great deference and implicit submission to the pleasure of the President of the United States, respectfully pray, that an alteration may be made in the place assigned for payment and that Lapointe on Lake Superior may be fixed upon as the place of payment that place being the annual rendezvous of the Chippewa Half Breeds and the Chippewa Indians Traders, by whom we are employed.

And your Petitioners as in duty bound shall ever pray &c. &c.

Lake Superior Lapointe Dec. 20th 1838

Michel Neveu X his mark

Louis Neveu X his mark

Newel Neveu X his mark

Alexis Neveu X his mark

Joseph Danis X his mark

Benjamin Danis X his mark

Jean Bts Landrie Sen’r X his mark

Jean Bts Landrie Jun’r X his mark

Joseph Landrie X his mark

Jean Bts Trotercheau X his mark

George Trotercheau X his mark

Jean Bts Lagarde X his mark

Jean Bts Herbert X his mark

Antoine Benoit X his mark

Joseph Bellaire Sen’r X his mark

Joseph Bellaire Jun’r X his mark

Francois Bellaire X his mark

Vincent Roy X his mark

Jean Bts Roy X his mark

Francois Roy X his mark

Vincent Roy Jun’r X his mark

Joseph Roy X his mark

Simon Sayer X his mark

Joseph Morrison Sen’r X his mark

Joseph Morrison Jun’r X his mark

Geo. H Oakes

William Davenporte X his mark

Robert Davenporte X his mark

Joseph Charette X his mark

Chas Charette X his mark

George Bonga X his mark

Peter Bonga X his mark

Francois Roussain X his mark

Jean Bts Roussain X his mark

Joseph Montreal Maci X his mark

Joseph Montreal Larose X his mark

Paul Beauvier X his mark

Michel Comptories X his mark

Paul Bellanger X his mark

Joseph Roy Sen’r X his mark

John Aitkins X his mark

Alexander Aitkins X his mark

Alexis Bazinet X his mark

Jean Bts Bazinet X his mark

Joseph Bazinet X his mark

Michel Brisette X his mark

Augustin Cadotte X his mark

Joseph Gauthier X his mark

Isaac Ermatinger X his mark

Alexander Chaboillez X his mark

Michel Bousquet X his mark

Louis Bousquet X his mark

Antoine Cournoyer X his mark

Francois Bellanger X his mark

John William Bell, Jun’r

Jean Bts Robidoux X his mark

Robert Morin X his mark

Michel Petit Jun X his mark

Joseph Petit X his mark

Michel Petit Sen’r X his mark

Pierre Forcier X his mark

Jean Bte Rouleaux X his mark

Antoine Cournoyer X his mark

Louis Francois X his mark

Francois Lamoureaux X his mark

Francois Piquette X his mark

Benjamin Rivet X his mark

Robert Fairbanks X his mark

Benjamin Fairbanks X his mark

Antoine Maci X his mark

Joseph Maci X his mark

Edward Maci X his mark

Alexander Maci X his mark

Joseph Montreal Jun. X his mark

Peter Crebassa X his mark

Ambrose Davenporte X his mark

George Fairbanks X his mark

Francois Lemieux X his mark

Pierre Lemieux X his mark

Jean Bte Lemieux X his mark

Baptist St. Jean X his mark

Francis St Jean X his mark

Francis Decoteau X his mark

Jean Bte Brisette X his mark

Henry Brisette X his mark

Charles Brisette X his mark

Jehudah Ermatinger X his mark

Elijah Eramtinger X his mark

Jean Bte Cadotte X his mark

Charles Morrison X his mark

Louis Cournoyer X his mark

Jack Hotley X his mark

John Hotley X his mark

Gabriel Lavierge X his mark

Alexis Brebant X his mark

Eunsice Childes

Etienne St Martin X his mark

Eduard St Arnaud X his mark

Paul Rivet X his mark

Louisan Rivet X his mark

John Fairbanks X his mark

William Fairbanks X his mark

Theodor Borup

James P Scott

Bazil Danis X his mark

Alexander Danis X his mark

Joseph Danis X his mark

Souverain Danis X his mark

Frances Dechonauet

Joseph La Pointe X

Joseph Dafault X his mark

Antoine Cadotte X his mark

Signed in Presnce of

John Angus

John Wood

John William Bell Sen’r

Antoine Perinier

Grenville T. Sproat

Jay P. Childes

C. La Rose

Chs W. Borup

James P. Scott

Henry Blatchford

By Leo

The Austrian writer, adventurer, and academic, Karl Ritter von Scherzer traveled the United States along with Moritz Wagner in 1852 and 1853. Their original German-language publication of Reisen in Nordamerika is free online through Google Books (image: wikimedia commons).

Chapter 21 of Wagner and Scherzer’s Reisen in Nordamerika in den Jahren 1852 und 1853 appeared on Chequamegon History in three posts in 2013. Chapter 22 continues the story, as Carl Scherzer describes his trip up the full length of the Brule River in September 1852, riding in a birchbark canoe guided by two La Pointe voyageurs: Souverain Denis and Jean Baptiste Belanger.

Chapter 22 lacks the variety and historical significance of chapter 21 (Ontonagon to the Mouth of the Bois-Brule), but even in Google-based translation, it maintains much of Scherzer’s beautiful (often comical) prose, that should be appreciated by readers with a fondness for canoeing. It also includes the lyrics of an authentic voyageur song that does not appear to be published anywhere else on the web.

Themes in this chapter also continue ideas explored in other Chequamegon History posts. If you wish to read more about the absolute misery encountered by inexperienced canoeists on the Brule, be sure to read the account of Lt. James Allen who accompanied Henry Schoolcraft to Lake Itasca in 1832. If reading Chapter 22 makes you think that mid 19th-century European travel writers superficially appreciated Ojibwe culture more than American writers, but that their romanticism contained the seeds of dangerously-racist ideas, be sure to check out J. G. Kohl’s Remarks on the Conversion of the Canadian Indians, another Google-aided German translation first published in English right here on Chequamegon History.

Enjoy:

XXII

A Canoe Ride through the Wisconsin Wilderness

The Rivière du Bois Brülé or Burnt Wood River (Indian: Wisakoda) has a rocky riverbed and runs east-southeast. Its serpentine curves are navigable close to 100 miles, nearly from the source to the mouth by canoes. It has 240 rapids, varying in length, alternating with smooth surface for a length of eighty miles. Most of the rapids have a one-foot, but many an eight to ten-foot slope. Four of them are so dangerous, they require portage, that is, they must be bypassed, and the boat and baggage are carried past the most dangerous points on land.

The width of the river changes tremendously. At its mouth, it is probably ninety feet wide, then sometimes narrows down to a few feet, and then expands just as quickly to the dimension of a considerable waterway. Its total slope from its source to its mouth in Lake Superior is about 600 feet. We therefore had the doubly-difficult task of overcoming river and the slope.

We took our frugal lunch of bacon and tea on a small mound of sand. We looked back and saw, probably for the last time in our eyes, but lasting forever in our memories, Lake Superior.

It should be noted that such letters are not uncommon in this great primeval forest, where bald towering tree trunks are more reliable postmen than the whims of hunting Indians, ignorant of their duties. Suddenly, Baptiste cried out, “Une lettre! Une lettre!” Mounted on a high pole, a letter hung wrapped in birch bark. It was addressed to a “Surveyor in the wilds of Lake Superior”–truly, an extended address! The letter was accompanied by a slip of paper, also in English, in which the readers, insofar as it did not concern them, were requested to leave it undamaged in its eye-catching position.

In winter, when Lake Superior is often unnavigable for months, the postal connection with La Pointe is an arduous forest path taking nine days to reach St. Croix Falls. Since it sometimes happens that the frivolous mix-bloods, growing weary of their postal duties hang their letters on the next branch and happily return to their favorite activity: hunting the wild forest thickets. The pack sits on the tree until a more-conscientious wanderer happens upon it. Thus, it takes three months to travel a road that would be covered in as many days in civilized area with modern transportation.

Birches (betula papyracea), elms, poplars, ash trees (fraxinus sambucifolia), and oak trees make up the bulk of these primeval forests. However, spruce, pine (pinus resinosa), firs, (abies balsamea and alba), cedars and juniper trees appear in such a pleasant mixture that their dark green forms a magnificent base note for the deciduous wood, as it bleaches golden in the autumn.

Within a half hour, the clear light-green water, 6 feet deep at the entrance, dropped to half a foot. From this, one may get a sense of the lightness of our birch-barked vehicle. In spite of the people, travel utensils, and provisions, probably amounting to 800 pounds of load, it glided gently, without even brushing the shallow riverbed.

The further we went up the river, the more virgin and primeval the forest, and the wilder and wilder the little waterway became. At places, tree trunks had fallen across the river and completely blocked our way. We had to take up the handy carpenter’s ax to cut a passage through. Under such navigational conditions, the oars lay quietly against the walls of the canoe, and long, hand-hewn poles were our only means of locomotion.

A heavy rain left us short on time to look for a bivouac. We spent the night in the woods under old spruce trees. Their trunks were more than 120 feet in height. Every night, we tied the thermometer to a tree branch out of the wind, and then recorded our observations in the morning. That was the only time we were able to maintain a regular hour of observation.

Friday, September 24, 53°F. Yesterday’s heavy rain has stopped, and as far as you can tell from under our green jungle canopy, the sky is quite clear and cloudless.

We continued the journey at 8 o’clock. At points, wind-broken spruce and beech hung from both sides, their still-green jewelry forming arcs of triumph across the river.

The splendorous color of the forests is enhanced by the mighty brush of autumn. You can already notice the work of this brilliant painter on the foliage of the oaks and elms. Only the stiff firs and ancient spruces, seen against the sky, allow the autumn storms to rush past without changing their defiant green.

We had a short portage to make, and a part of the provisions and effects had to be carried over the rapids. Landed at 12 o’clock for lunch. Our canoe was already severely damaged by the low water level and numerous rocky cliffs, and it began to fill with water. Now, all our luggage had to be brought to the shore and the empty boat had to be turned over to wrap the leaky areas watertight again.

For the whole afternoon’s journey, the same wild character of nature prevailed. Trees on opposite banks bent in pyramids and wrapped around each other at the summit. Sturdy roots of ash, elms, oaks having lost their balance, hung like an arched bridge over the surface of the water. All around, the eye sees the rugged beauty of the forest. Little has changed in nature or navigation in the two hundred years since the first missionary in a birch canoe passed through this wilderness.

At points, the thicket clears, the land becomes flatter, the river broadens, small lush archipelagoes rise, and the scenery gains the prestige of a modern park. In such areas, the wild rice (Zizania aquatica) comes into view. Along with hunting and fishing, it constitutes a staple food of the Indians. A marsh plant, it usually grows only in lowlands (sloughs), which are 8 to 10 inches under water for most of the year.

The harvest happens in the autumn, in a simple and effortless way. The Indians drive their slender canoes through the reeds into the middle of the rice fields. They bend the ears from both sides over the boat, and then beat out the fruit with fists and sticks, where it falls to the floor of the canoe. Most of the time, they roast the rice (Oumalouminee) and enjoy it boiled in water. Sometimes, however, when this seems too much trouble for them, the humble forest-dwellers are content to chew the raw fruit like kinikinik or smoking tobacco as a noonday meal.

When we asked Souverain how far we still had to go to the next portage, he replied that it might still be a distance of two pipes (deux pipes), by which he meant to say that we would arrive after the time in which one is able to smoke two pipes.

The black rocky bottom of the river makes the water so dark, it becomes very difficult to distinguish the sharp slightly-covered, rocks from the water, and so our boat received more than one jolt and leak. At half past four, we had to make a second portage of half a mile in length. Both the boat and the baggage had to be carried through the forest. We camped at the other end of the trail at the edge of a northern beech forest. Evening, 7 o’clock 48° F.

Saturday, 25th of September, 40° F. Heavily clouded horizon, windless, rainy. Our matches got wet and prevented us from starting a fire. Finally, a flint was found in a tin, but the gathered wood was green and wet, and took a long time to burn. After 7 o’clock, we set out. Exclusively hardwood vegetation, now, namely ash, elm, silver poplar and birch, which would seem to indicate a milder climate.

The remnants of Indian night camps are noticed at many points in the forest: the charred fire, the fresh tree-branches placed in the ground where the kettle hung above the flame, the dry wooden skeletons that were once wigwams.

Several jumbles of tree branches had to be chopped in half this morning with the ax in order to make a passage for us. Only half an hour after our departure from bivouac, we arrived at the third portage. Under heavy rain, we carried the effects through the forest on a trail that only occasionally hinted at ancient, long-weathered tracks. This time, the canoe could be pulled over the rapids, but only through a heroic decision of the two leaders to wade alongside it in the frosty, cold river. At 8:30, this painstaking portage was over, and the journey across the less-dangerous rapids continued in the canoe.

In the afternoon, more coniferous trees appeared, especially on the right bank. The rapids often continued for miles, and Souverain, the admiral of our birch-barked frigate, to whom was entrusted our destiny, had more than a hard row to hoe. Twice, shying away from the effort of cutting, we boldly passed over mighty tree trunks fallen into the river. Several times, our barge slid so narrowly under tree trunks hanging over the water there was scarcely enough space left us, lying with our backs against the bottom, to squeeze under with our slender canoe.

Despite the reappearance of softwood vegetation, the area visibly takes on a different character as it gradually changes from the hilly landscape of Lake Superior to the flat prairie ground of the West. The trees in the forest become less dense, while willows, cypresses, larches, and Thuja occidentalis are more frequently seen. On the banks, young saplings proudly take the place of the noble-stemmed spruce.

Based on our experiences so far, we would not recommend that future travelers rely too much on hunting and fishing while traveling through these wilderness areas. The almost incessant rapids give the river a current far too strong for it to be a popular habitat for fish, and the game is usually scanty along the shore. In addition, the gun often suffers much from the water, which the powerful sweep of the poles and paddles sends over the side of the canoe. Due to this moisture, which is almost unavoidable in such a small space, even the best-measured shots often fail.

Once, it was inspiring to see the keen-eyed Souverain pick out a water snipe among the bushes. Not knowing its mortal danger, it promenaded itself carelessly in search of food. We approached quietly with the boat, drawing near to fell the victim with the shotgun, and Souverain shot his enemy-snipe-weapon. The shot failed. A second and third had the same fate. The charges had been dampened by prolonged rain.

(wikimedia) Wasserschnepfe is a generic German term for several species in the family Scolopacidae (snipes and sandpipers). Wilson’s Snipe (left) or the American Woodcock (right) are likely candidates for the suicidal Brule bird. Hypochondria was used as a synonym for depression in the 19th century–see the opening paragraph of Moby Dick for an example.

(wikimedia) Wasserschnepfe is a generic German term for several species in the family Scolopacidae (snipes and sandpipers). Wilson’s Snipe (left) or the American Woodcock (right) are likely candidates for the suicidal Brule bird. Hypochondria was used as a synonym for depression in the 19th century–see the opening paragraph of Moby Dick for an example.Quite remarkably, the poor animal had still not left its dangerous post, as if it were overpowered by melancholy, and would receive the mortal shot as a blessing. The fourth charge finally did its duty. The snipe staggered and fell dead in a nearby bush. She was haggard and skinny, and seemed to have truly suffered from hypochondria. In the evening, we shot a duck. General joy was had over their fatigue, and we lustily enjoyed a good evening meal.

In the final hours of the journey, the river assumes a regular, almost canal-like course, which for some miles continued in a straight line. The rapids become rarer, but the river is densely covered with rock, which hides itself under the smooth barren surface of the water. Surprised by nightfall, and in the deceitful twilight not daring to go further among the aforementioned jagged rocks, we bivouacked close to the shore in a flat, swampy area.

As a rule, since we were on the Bois-Brülé river, we drove for ten hours a day, from 7 o’clock in the morning until 5 o’clock in the evening, unless rain or canoe repairs prevented us. Every morning, before we left, we prepared our breakfast, and made a very short stop at lunchtime. We pitched our tent only at the resting hour of the evening, when possible on a hill in an area where the presence of numerous dry logs could suffice for preparing a comfortable night fire.

After the two voyageurs had cut down and brought in 12 to 18 pieces of spruce or birch trunks in the forest, they usually left it to us to keep the fire at proper heat. No sooner had our evening meal been consumed, which, like the selection at the court of an Irish emigrant’s table–one day bacon and tea, and the next day tea and bacon–the two voyageurs, fatigued by the hard work of the day, would fall asleep. Our traveling companion, wrapped in a thick buffalo robe, found no more attraction in this body-strengthening pleasure. So we were faced with a choice, stoke or freeze.

Every night, we would get up four or five times to set new tree trunks on the dying glow. And when the fire flared up again, we’d sit a while and watch the joyous flaming wave, and think of our friends across the ocean. And as this new flame intensified, new glowing thoughts and feelings rose in us again and again, for the fire possesses the same miraculous power as the sea or the blue sky. One can gaze into it for hours and yet cannot get enough of it. One laughs and cries, becomes sad then cheerful again. – The logs that we burned last night, certainly amounted to half a cord of wood!

Sunday, September 25, 5:30, snowfall. A good fire in front of our tent makes it easier for us to bear the cold and the bad weather. All night long, we heard the cries of many flocks of ducks moving cheerfully off to the west. In the forest, now, one hears only the lonely lamentations of a woodpecker, his flight inhibited and decrepit, he could not follow the young flyers and is left behind. The snowfall prevents the boat from popping up, and we are forced to wait for better weather in this swampy, frosty wilderness.

7 o’clock, 35° F. A shot was fired nearby. It was probably the hunting rifle of wandering Indians.

Around 9:30, a canoe came up with an Indian and his squaw (Indian woman). It was the postman of La Pointe who had picked up the letters in St Croix and was on the way home. As soon as he saw our camp, he stopped, got out, and he and his wife warmed themselves by our brightly-lit fire.

He was a poor, one-eyed devil. In his little boat he brought wild rice (folle avoine) tucked under animal skins, which he wished to exchange for resin to repair his damaged canoe. The shot we heard a few hours earlier fell from his shotgun, but the duck he aimed never did. The postman did not seem to be in a hurry. He talked to the voyageurs for more than an hour, then said good-bye and Boshu* to the fire’s warmth and to us.

[*Boshu, also bojoo or bojo, is undoubtedly a corruption of the French “Bon jour,” which is used by all Indian tribes on this side of the Mississippi for all kinds of greetings in the widest sense of the word. In general, the Chippewa language is teeming with English expressions, for which they have no name in their own language. The same is the case with the Indians of British Guiana, who have included many Spanish words in their language: cabarita, billy goat (Indian: cabaritü), sapatu, shoe (Indian zapato), aracabusca, firearm (Indian: arcabug). It deserves great attention at a time when we seem more inclined than ever to draw conclusions about the descent of peoples from certain similarities in languages. Comp. Dr. W. H. Brett, Dr. Thomas Jung, etc.]

11 o’clock in the morning. After the snow stopped, we quickly patched some areas on the boat, damaged by the sharp rocks. After a short snack of bacon and salt meat, we proceeded further up the river. We intended to continue, without further delay in a southwesterly direction, until dawn, hoping to escape this frighteningly-cold region.

The scenery and nature remained the same as yesterday. Hardwood, among which the American elm (ulmus americana) prevails. With its imposing height and rich crown of leaves, it is a major ornament of the American forests. With the shallow shores, rice marshes and trees hanging over the river under the weight of their leaves, our canoe laboriously sighs under its oppressive cargo. The rapids start again. The river is about 40 feet wide.

About 2:30, we passed through ten minutes of rapids, whose completion required the full effort of our two canotiers. In addition to the countless rocks, we passed through the lowest water levels, over uprooted trees that had fallen into the river. Our journey now resembled the pushing of a cart than it did the light gliding of a birch canoe. It was a fight with the water and nature. We were in danger of wounds to our heads and eyes, passing close under the wild bushy oaks and spruces that jutted into the water.

The landscape afforded variety of rich, picturesque views. Every bend, every new opening, showed the visitor a new image. At times, the river extended to the breadth of a lake, and cedars, cypresses, thujas, and all the green foliage of the swamp vegetation becomes visible. Where the rapids stop, the mirror-clear, calm water comes alive with trout and swimming birds. All at once, however, the picture will close, and the two shores form an incessantly-bright green alley, through which the smooth river stretches like a long white vein of silver.

By evening, our little boat was suffering greatly from the incoming cold. At sunset, we camped on the so-called Victory Grounds (pakui-aouon). It is a cleared piece of forest, about 40 feet above the river, that forms a kind of plateau, upon which bloody battles must have taken place in former centuries between the Sioux and Chippewas.

The cause of the hatred between these two tribes of Indians remains an object of research. However, one only needs to mention the name one tribe, to a person of the other in order to provoke his rage. Against this, even the hatred of the Czechs, who in the blessed year of Revolution wished to devour all of Germany, pales in comparison. For as often as the Sioux come into contact with Chippewa Indians, they will certainly commit a murder, because according to their legal concepts, it is their duty to scalp as many Chippewas as possible.

In the evening, when the tent is pitched, the night’s wood is felled and carried in from the forest, the fire is lighted and a small meal is prepared and consumed, the four of us would sit still for a while around the warming fire. We would listen to the voyageurs tell us about their experiences and destinies, and about the savagery of the whites and the gentleness of the Indians. Sometimes, they also sing songs that have strangely found their way from the home of the troubadours to these soundless primeval forests of the north*. Here we repeat one that Jean Baptiste sang out this evening with much emotion, as he lay carelessly, disregarding the flickers of the burning fire:

Chanson canadienne

(Canadien song)

Buvons tous le verre à la main,

Buvons du vin ensemble;

Quand on boit du vin sans dessein,

Le meilleur n’en vaut guère.

Pour moi je trouve le vin bon,

Quand j’en bois avec ma Lison.

(Let’s drink down the glasses, in our hands,

Let’s drink wine together;

When you drink wine without purpose,

Even the best is not worth it.

For me, I find the wine tastes good,

When I drink with my Lison.)

Depuis longtemps que je vous dis:

Belle Iris je vous aime,

Je vous aime si tendrement,

Soyez moi donc fidèle,

Car vous auriez en peu de temps,

Un amant qui vous aime.

(For a long time I have been telling you:

Beautiful Iris I love you,

I love you so dearly,

Be faithful to me,

For in a short time you will have,

A lover who loves you.)

Belle Iris, de tous vos amants

Faites une différence,

Je ne suis pas le plus charmant

Mais je suis le plus tendre.

Si j’étais seul auprès de vous,

Je passerais les moments les plus doux.

(Beautiful Iris, of all your lovers

Make a difference,

I am not the most charming

But I am the most tender.

If I were alone with you,

I would have the sweetest moments.)

Allons donc nous y promener,

Sous ces sombres feuillages,

Nous entendrons le rossignol chanter

Qui dit dans son langage,

Dans son joli chant d’oiseau,

Adieu amants volages.

(Let’s go for a walk,

Under the dark foliage,

We will hear the nightingale

Who sings in his language,

In his pretty bird song,

Farewell lovers.)

“Ah! rendez-moi mon coeur,

Maman me le demande.”

“”Il est à vous, si vous, pouvez le reprendre.

Il est confondu dans le mien,

Je ne saurais lequel est le tien.””

(“Ah! Give me back my heart,

Mother asks me.”

“It’s yours, if you can, take it back.

It is mixed up with mine,

I will not know which is yours.”)

[*It is a common observation that the painted native forest dwellers of America are not as eloquent as their much-simpler dressed German counterparts. Although we passed through the forests of Wisconsin, Missouri, and Ohio in all seasons, we never heard as beautiful and funny singing as in the German hall. It is as if nature wanted to compensate the German forest singer for his lack of splendor through the richer gift of song. Comp. Franz v. Neuwied and Agassiz, Lake superior etc., p. 68 u. 382, respectively.]

Monday, September 27th, 35°F. Sky is completely changed, haunting cold. The snow began to fall so thickly, we had to stop again, after a short time, to build an invigorating fire in a cedar forest amidst swamp and morass. But when the flame began to grow, its warmth reached the snowy branches of the cedar trees. The snow turned to water and fell upon us as heavy rain. We were all thoroughly soaked, and the fingers of the two canoe handlers were so frozen by the biting snow they could not paddle the ship. So we sought, as well as it was possible under such unfavorable weather conditions, to warm ourselves, and finally resumed our journey at noon under snow, rain, and a sharp north wind.

12 o’clock, 42°F. Soon after our embarkation, we had to make a small portage, and happily bypassed La Clef de Brülé, a number of rapids, which in their dangerous places are called by the voyageurs “The Key to the River”.

Cedarwood now grows almost exclusively on both banks, down to the river’s edge. They sometimes seem so harshly thrown over one another that the canoe can pass through only with difficulty.

“Cedar,” used generically on today’s Brule River could only mean the Whitecedar or Arbor Vitae Thuja occidentalis (top). Curiously, however, Scherzer specifically distinguishes Thuja from Juniperus virginiana or redcedar (bottom) and describes the latter as more common, even though J. virginiana is not found this far north.

“Cedar,” used generically on today’s Brule River could only mean the Whitecedar or Arbor Vitae Thuja occidentalis (top). Curiously, however, Scherzer specifically distinguishes Thuja from Juniperus virginiana or redcedar (bottom) and describes the latter as more common, even though J. virginiana is not found this far north.2:30 48°F. The snowflakes have changed to raindrops with the increasing temperature. Gradually, the rain stopped, and there was overcast, but rain-free weather. We now reached the Campement des Cedres, the only place up to the source of the river, where one still finds enough wood to prepare a night fire as all tree species except cedars (juniperus virginiana) are now becoming sparse along the shores. The discomfort of travel is now joined by a feeling of an unshakeable cold.

We therefore resolved to reach the navigable end of the Bois Brülé river that evening, and our captains endeavored to reach it before nightfall.

The rapids had now stopped, but another no-less uncomfortable and dangerous guest turned against us. The bushes of alders (alnus incana), willows, berberis, etc. grew on both banks. In their undisturbed growth, they had become so impenetrable that at the first sight of these thousands of closely intertwined branches, we often thought it impossible to break through with a canoe. The river was completely invisible in these thick, shady hangings, and hoe, pole, and fists had to be activated to fight all these natural hindrances.

Sometimes, we could only pass through horizontally, with our heads back to the bottom of the canoe. Closing our eyes to the relentless branches, we completely abandoned ourselves to the care of the brave Souverain. His face and hands scratched by the tiny branches, he undauntedly strove forward with unspeakable effort. Only a few times, when these forest barricades grew too overpowering, we heard a half-desperate, “mais c’est impossible!”

This wild overgrowth of the two banks, which gave our boat journey more of a character of first voyage of discovery than that of following a well-trodden path, can only be explained by the circumstance that the river is only seldom traveled up to its source. Earlier, when La Pointe was the Fur Company’s trading post, several hundred canoes loaded with commodities traveled this route every year, and from there they crossed to the various trading places of Upper Mississippi. But since Indians, forest animals and fur traders have moved westward, the cheerful waters of the Bois Brülé often trickle by, through entire seasons, without being cut by the keel of a boat, and the lush vegetation of its shores is free to reach across and embrace in wild passion.

Around 5 o’clock, we found the water of the river so low in several places that we decided to give some relief to the canoe by continuing the rest of the journey to the source of the river on foot. We walked back a mile and a half along a forest path, under the most unfavorable conditions. Our bodies wrapped from head to toe in India rubber, we sat with our travel companions against the moving forest, while the two voyageurs with canoe and effects followed the course of the river to meet us again at the grand portage.

Hardly could a hike offer more variety. Without the slightest indication of the path to be taken by the usual old footprints and tree cuts, we fought thorn bushes through deep snow, then passed through wild grain as tall as man, swiftly mowing it under our boots. In the hurry to disembark, we left our compass in the boat, so we could only guess what direction we should start navigating to find the so-called “Great Carrying Place.”

We wandered the wilderness, sweaty and fatigued, unable to move with any speed. The night was already falling, and as our innumerable “hallos,” went unanswered by our captain, we fell silent in the solitude of the forest, coming to terms with the idea of spending the night in these cold, fever-inducing swamps. All of the sudden, the voices of the voyageurs resounded like a hallelujah. We had to be very close to them, so we gained fresh courage against the complaints of pressing each step forcibly through dense undergrowth of thorny shrubs.

Drenched and chilled, we finally reached the Portage on a hill above some young cedars, and found the Voyageurs already occupied with the clearing and patching of the canoe. Unlike ourselves, our travel companion and the two Canadians had no rain-resistant rubber outfits, and were even more exposed to the cold, wet weather. For a time, the shivering appearance of our companion made us fear for his health.

In addition, we soon learned of a new misfortune. The snow cover and lack of wood in the vicinity prevented us from pitching our tent preparing a good fire as fast as our condition might desire. Besides, all our packs had gotten wet, and the provisions were in a poor state of edibility.

Our first concern, when we finally succeeded in pitching the tent and building a fire, was to dry our underwear and garments. All around us, hanging from tree branches and ropes were scattered cloths, spread out and drained of color. In our haste to remove the uncomfortable liquid from our needed garments through the warming power of the flame, we brought them into too-close contact with the wildly-flickering fire. Regrettably, they were soon covered in traces of scorch marks.

Nothing in our preceding traveling conditions had so deeply embittered us or made us as morose as these recent events. It is true that none of us complained, but each man stood in perfect silence before the burning logs, and regrettably stared at whatever soaked garment he was holding in his outstretched arms before the drying glow. Our medicines in vulgar condition, and our books, writings, documents, and physical instruments, all partially corrupted or totally broken, there was not a single piece of our effects which did not bear some lasting trace of damage.

The only consolation was that the snowstorm ended, and the overcast sky dissipated into a bright, starry, moonlit night, which made the prospect of a more favorable morning and forgetting the troubles of today, less and less difficult to fathom.

A short distance from the Portage is the inconspicuous source of the Bois-Brule River, in the marshes all around.* Only a single small stream pours into it during its long, winding course to Lake Superior. The Campement du Portage, where the travelers usually camp, is situated on a small hill, adorned with a serene cedar and spruce approach. While it may present a charming bivouac during a pleasant, warmer season. The eerie conditions under which we spent the night on the cold, damp ground could not possibly give us an idea of their summer loveliness.

[*The water of the Bois-brule River is about 12-14° Fahrenheit cooler than that of the La Croix River, for which may be explained by its forest-shaded banks being almost inaccessible to sunbeams, as well as its proximity to Lake Superior.]

In winter, when the river freezes along its entire length, it must be a marvelous sight: the wild rapids suddenly frozen by the harsh power of frost, and transformed into the strangest shapes and ice formations.

S.

CAUTION: This translation was made using Google Translate by someone who neither speaks nor reads German. It should not be considered accurate by scholarly standards.

Our last excerpt from Wagner and Scherzer’s Reisen in Nordamerika in den Jahren 1852 und 1853. The Austrian travelers chronicled their time at La Pointe in September 1852. In this one, we will read of their adventures in my favorite part of the world, the south shore of Lake Superior between La Pointe and the Brule River. 160 years later, residents of Red Cliff, Little Sand Bay, Cornucopia, Bark Point, Herbster, and Port Wing will still recognize many of the natural features described here, and more interesting anecdotes can add to the small amount of written historical documentation of this part of the world. Enjoy:

Red Sandstone: South Shore of Lake Superior: from David Dale Owen’s Report of a Geological Survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota (1852).

XXI

From Ontonagon to the mouth of the Bois-brule River–Canoe ride to Magdalen Island–Porcupine Mountains–Camping in the open air–A dangerous canoe landing at night–A hospitable Jewish family–The island of La Pointe–The American Fur Company–The voyageurs or courriers de bois–Old Buffalo, the 90 year-old Chippewa chief–A schoolhouse and an examination–The Austrian Franciscan monk–Sunday mass and reflections on the Catholic missions–Continuing the journey by sail–Nous sommes degrades–A canoeman and apostle of temperance–Fond du lac–Sauvons-nous!

Since the weather was favorable, we decided prospects were right for our trip to the mouth of the Burnt Wood (Bois-brulé) River. We made all the necessary travel arrangements that evening, and even bought supplies of bacon and salted beef for fourteen days of “wild life.” We were also compelled to buy a new birch canoe*, to allow the two Canadians who will conduct us on the waters of the Bois-brulé and La Croix Rivers, through the wilds of Wisconsin to Stillwater, to make the return journey by water instead of through the woods on foot, and we had not been able to arrange for borrowing a boat.

(*These canoes are the only vehicles used by the Indians to navigate the lake. They are either made of a framework of cedar wood and covered with birch bark, with the individual parts made watertight with pitch, or they can also be carved out of a single spruce trunk hollowed to where two or three can sit. The former are preferred for their greater ease and convenience, but the latter are more durable, safer, and less expensive. Our canoe was made of birch bark and measured 18′ in length and 4′ in width. We bought it for 15 dollars, and we were very pleased when we were able to get rid of it at the end of our trip for five dollars).

Monday, September 20th, 53° F. Overcast weather but the lake completely calm, we left accompanied by the pious blessings of the Island’s Franciscan monk.

This time our boat carried a light burden. The captain stayed back out of concern there would be too many hardships and inconveniences. It was very strange to see such an experienced traveler unwisely refuse to carry a proper thick rain coat. With thin boots, a light Carbonari, and a few underwear tied in a small bundle, he took leave of us to shiver in the elements. Addio Capitano!

Our traveling companions were now a young Frenchman and two Canadians, Souverain and Jean Baptiste. The latter two were entrusted with managing the canoe. Souverain, though his thin gray hair, his toothless mouth, and his wrinkled face betrayed the features of advanced age, he was undoubtedly the more able and accomplished of the two voyageurs. Baptiste, however, strong and tireless in his youth, was an excellent complement to the old man.

Indian Sugar Camp (1850) by Seth Eastman, as depicted in Schoolcraft’s Information Respecting the History, Conditions and Prospect of the Indian Tribes of the United States, 1847-1857 (Digitized by Wisconsin Historical Society; Image ID: 9829).

We passed the Apostle Islands, 12 in number, most of which, including “Spook Island” are planted almost exclusively with maple trees (Acer saccharinum), from which the Indians prepare sugar. Every year in March and April, they make deep transverse incisions, from which, like the dripping pitch extracted from pine trees, a fresh green juice flows. Every tree can be tapped 5-6 years, in such a way to be made controllable, before the tree is disabled and is only good for the fire. In La Pointe, about 10 Indian families produce 1000-1500 pounds of sugar every year. In Bad River, there are more than 20 Indian families, who collectively produce 20,000 pounds. A pound of maple sugar is obtained by the traders for one shilling (twelve and one half cents) delivered to the Indians in kind.

We passed several miles of 40-60 foot high red sandstone cliffs, which the lashing tide had formed into the most picturesque architectural forms, among which arch and pillar structures were most prevalent. Several were formed in such a way as to create columned caverns under which a canoe could easily pass. The under-washing of this gigantic mass of rock may explain the gradual extension of the south shore.

Favored by a northwest wind, we had already covered 21 miles in 6 hours, and arrived at Riviere au Sable. We could clearly make out the north shore 50 miles distant, and the mountain chain of the British Territories, whose highest point, according to Dr. Norwood of Cincinnati is 1650 feet.

As with lucky speculators in the trading cities, our canoeists wanted to exploit the favorable wind direction even more. They turned their only protection against the cold, blue and white blankets, into excellent sails. They tied together cloth on one side to secure the oar, while they used green pine branches on the other side to maintain tension against the wind. It always remains dangerous, however, to attach a sail to so volatile a vehicle as a canoe, for a single contrary wind shock can cause the canoe to lose balance and leave the drivers to pay for their daring with terrible flooding.

In the evening, just as we were about to pitch our camp at the bay of Siscawit River, we were surprised by a terrible rain that drenched the greater part of our effects and brought great danger to our physical instruments. We were, for a long time, without the benefit of a warm fire, but our perseverance gradually allowed our flickering light to defeat the dampness, and we had flame to cook our modest supper. One often camps at the mouths of these numerous small tributaries of Lake Superior. It has always been this way, and the reason is that during stormy seas on the open water, the bays that surround the mouths of these rivers protect you from the wind and waves.

The small canvas tent, lent to us by the hospitable postmaster in Ontonagon, served us beyond expectation as powerful protection from the cold and wetness. We soon found ourselves under the soaked canvas roof in comfort we hardly thought possible in such harsh camp conditions. We must admit, however, that our foresight in bringing suits made of India rubber to spread on the ground, spared us the rheumatic breaths of the damp earth beneath us.

Tuesday, September 21, 53°F. Persistent rain and completely clouded-over sky with little chance of favorable traveling weather. During the night, the rains became so heavy that they seeped in through the canvas in several areas. Our laundry bags were totally soaked, and there was no opportunity to dry them. When camping like this, one should always keep items requiring special protection in the rear of the tent, and all care should be made to not let them touch the stretched canvas, which once wet will keep everything damp for weeks.

This morning, we had to celebrate wind, that is, a violent northeast wind prevented us from proceeding any further. “Nos sommes dégradés,” the old captain sighed, and told us how he was once stranded by violent storms, and had nothing but a dry biscuit to eat for four days. We held a small war council without a general, but with merely reason to guide us, and decided that due to this delay, we should limit our meals so that we would only enjoy the salted meat every other day. Decreasing to half rations, was necessary, as we were on the treacherous Lake Superior, which as already noted, often makes travel impossible or highly dangerous for weeks on end. Once we reached its desired tributary, the mouth of the Bois-brulé River, we would have no more fear of such a wicked delay from wind and waves.

Around 6 o’clock in the evening, the waves took on a less dangerous character. We quickly pulled down our tent, packed our belongings, and hastily boarded our already-floating boat. In boarding a canoe, caution must always be used to avoid stepping harshly with the whole foot above certain cedar ribs. This can disturb the equilibrium which can have the consequence of losing your effects, or even your life.

After an hour, we had followed a fierce north wind to Pointe aux écorces looking for a refuge. We wandered along the shore until after dark, but the rugged rocky reefs made landing impossible. Finally, we found sandbars, and pitched our tents near a tamarack swamp. Those who travel without a tent can usually find shelter from the rigors of the weather by setting the canoe at the proper angle and finding room underneath it.

We camped in a group of pines as tall as the sky. At the foot of these ancient tree trunks, our fire burned like a flaming sacrifice of the ancients. As the two voyageurs fell fast asleep at the entrance of the tent, we continued to feed sticks into the fire so as to not lose its benevolent warmth. Our fire was basically built into the base of a great pine, which gave the whole scene a picturesque backdrop, until the whole thing fell during the night with a heavy crash. This brought us all to our feet, sober and alert. There was no danger, however, as we had put numerous cuts into the tree so that it would fall away from us in the event it gave way.

Wednesday, September 22, 64°F. Northwest wind. The cheerful light of the morning sun woke us weary sleepers early. The seas were pretty rough. Once we had the infamous Point aux écorces at our back, we heard the roar of the busy oncoming waves. The red sandstone remains the predominant formation. The green hills of a moderate height, almost 50′, are embraced by a wide belt of spruce, Scotch Pine, birch, and beech. The more we approach the western end of the lake, Fond du lac, the narrower the space between the southern and northern shores becomes.

At the Riviere aux Attacas, we landed for breakfast. This time, there was bacon, whitefish, tea, butter, and hardtack, all remnants of the past brought from La Pointe. The songs our guides sang to strengthen the heart were far more modest and ethical than the erotic verses of our previous voyageurs who brought us from Ontonagon to La Pointe. The brilliant sunshine gave way to a completely cloudy sky, and a terrible northwest wind blew us into the bay of Apacha River, and there we resignedly made our night camp even though the Bruly River, as the natives call it for short, was only 12 miles away.

In the evening, we unconsciously discovered Souverain’s severe, but honorable, strength of character. We had brought a bottle of franzbranntwein, more for health than to tickle the tongue, and we poured each of our leaders a glass of this invigorating stomach potion. The younger, Baptiste, opened his throat widely and readily, but Souverain steadfastly refused even though he had worked hard all day and had taken little food.

We were curious and asked him about the cause of this refusal. He told us how he was inclined too much toward the spirituous fluids, and that to combat this, as few years ago he joined a temperance society and pledged in writing to abstain for fifty long years from all liquors. Since then, he has had not a drop of wine. His total abstinence went so far that he was not even moved to enjoy a rice broth in which we had mixed a few drops of the franzbranntwein, to give our guides more power.

This incident reminded the Canadians of some humorous anecdotes from living memory. Souverain told of an elder mix-blood who joined him for a limited period of temperance, with the lovely intent of indulging all the more joyously after the “dry” time. Baptiste told of a fisherman in La Pointe, who, since the sale of alcohol is prohibited on the island under penalty of 200 dollars, would get intoxicated almost every day with a bottle of burning hot peppermint water. Since this liquid, when used at low doses, is an excellent and popular remedy for stomach ailments, it was not easy to restrict its sale. Therefore, to save the life of this islander, the magistrate issued a special edict that the sale of peppermint is only allowed in small vials for medicine.

7 o’clock in the evening, 53°F. A gorgeous aurora borealis creates wisps and horizontal streaks of rapidly-changing dreamlike light.

Thursday, September 23, 63°F. We left early, around half past 7 o’clock. The abundant ashes of our extinguished fire, the tree trunk where our kettle hung, and the thin supports, under which our tent assumed its triangular shape, were the only traces left behind as a memorial of our presence.

Although a fairly violent south wind blew, he came from the mainland, so the waves on the lake were fairly calm, unlike those of his antagonist the engulfing north wind who yesterday threw the water up on the shore. For breakfast, we had tea, fried bacon, and galette. The latter is a composite made of kneaded flour, water, and compressed yeast dough, that seems extremely difficult to digest. It is usually prepared every morning by a practiced hand, and is gladly enjoyed, even preferred, by the voyageur.

The shotgun of our traveling companions produced a duck that will provide us with an excellent lunch. It is striking how much the forests along the banks are already emptied by Indian rifles. Temporary flocks of ducks and geese, in their autumn migration to a more southerly area, were the only wild species we encountered on our long journey. Likewise, the fishing in this season is extremely sparse, and he who leaves during these journeys to hunt or fish alone, will soon labor hard and bitterly regret his mistake.

Fond du Lac Village, At St. Louis River from David Dale Owen’s Report of a Geological Survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota (1852).

From the Bois Brule River to Fond du Lac, it’s about 21 miles, but to the mission and settlement on the St. Louis River, it’s about 42 miles. We could easily see with the naked eye, the contours of those western hills that mark the limit of this huge navigable water. And so, before we sailed up the Bruly, we paused to behold the joyous satisfaction of reaching the end of this enormous water, now reflecting the sky, on which we had spent 23 busy, enjoyable, and instructive days.

At 11 o’clock in the morning, we finally reached the destination we had anxiously waited for, the Bois-brulé River. Its discharge into Lake Superior was unusually low, but its flow was still very powerful. For our canoemen, it was a matter of routine to skillfully avoid a fatal collision with the bare rocky ridges at the landing.

Our captain had now thrown aside the oars as the long boat poles served better to find the sandy gaps among the rocks. Souverain stood at the upper end of the canoe and directed. He watched with a sharp eye for the moment when the perfect wave would come to our aid and carry us to the landing, and with the signal cry of, “Sauvons-nous!” it came suddenly, and we were borne to shore. We were at the mouth of the Bois-brulé River.

The End, for now…

CAUTION: This translation was made using Google Translate by someone who neither speaks nor reads German. It should not be considered accurate by scholarly standards.

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his