Reconstructing the “Martell” Delegation through Newspapers

November 2, 2013

Symbolic Petition of the Chippewa Chiefs: This pictographic petition was brought to Washington D.C. by a delegation of Ojibwe chiefs and their interpreter J.B. Martell. This one, representing the band of Chief Oshkaabewis, is the most famous, but their were several others copied from birch bark by Seth Eastman and published in the works of Henry Schoolcraft. For more, follow this link.

Henry Schoolcraft. William W. Warren. George Copway. These names are familiar to any scholar of mid-19th-century Ojibwe history. They are three of the most referenced historians of the era, and their works provide a great deal of historical material that is not available in any other written sources. Copway was Ojibwe, Warren was a mix-blood Ojibwe, and Schoolcraft was married to the granddaughter of the great Chequamegon chief Waabojiig, so each is seen, to some extent, as providing an insider’s point of view. This could lead one to conclude that when all three agree on something, it must be accurate. However, there is a danger in over-relying on these early historians in that we forget that they were often active participants in the history they recorded.

This point was made clear to me once again as I tried to sort out my lingering questions about the 1848-49 “Martell” Delegation to Washington. If you are a regular reader, you may remember that this delegation was the subject of the first post on this website. You may also remember from this post, that the group did not have money to get to Washington and had to reach out to the people they encountered along the way.

The goal of the Martell Delegation was to get the United States to cede back title to the lands surrounding the major Lake Superior Ojibwe villages. The Ojibwe had given this land up in the Treaty of 1842 with the guarantee that they could remain on it. However, by 1848 there were rumors of removal of all the bands east of the Mississippi to unceded land in Minnesota. That removal was eventually attempted, in 1850-51, in what is now called the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

The Martell Delegation remains a little-known part of the removal story, although the pictographs remain popular. Those petitions are remembered because they were published in Henry Schoolcrafts’ Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States (1851) along with the most accessible primary account of the delegation:

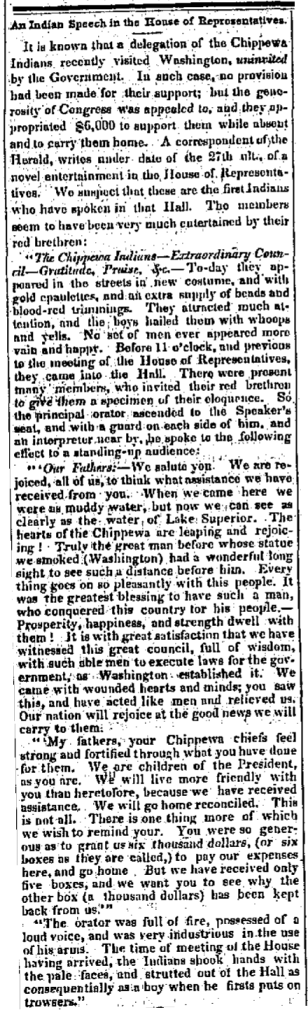

In the month of January, 1849, a delegation of eleven Chippewas, from Lake Superior, presented themselves at Washington, who, amid other matters not well digested in their minds, asked the government for a retrocession of some portion of the lands which the nation had formerly ceded to the United States, at a treaty concluded at Lapointe, in Lake Superior, in 1842. They were headed by Oshcabawiss, a chief from a part of the forest-country, called by them Monomonecau, on the head-waters of the River Wisconsin. Some minor chiefs accompanied them, together with a Sioux and two boisbrules, or half-breeds, from the Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The principal of the latter was a person called Martell, who appeared to be the master-spirit and prime mover of the visit, and of the motions of the entire party. His motives in originating and conducting the party, were questioned in letters and verbal representations from persons on the frontiers. He was freely pronounced an adventurer, and a person who had other objects to fulfil, of higher interest to himself than the advancement of the civilization and industry of the Indians. Yet these were the ostensible objects put forward, though it was known that he had exhibited the Indians in various parts of the Union for gain, and had set out with the purpose of carrying them, for the same object, to England. However this may be, much interest in, and sympathy for them, was excited. Officially, indeed, their object was blocked up. The party were not accredited by their local agent. They brought no letter from the acting Superintendent of Indian Affairs on that frontier. The journey had not been authorized in any manner by the department. It was, in fine, wholly voluntary, and the expenses of it had been defrayed, as already indicated, chiefly from contributions made by citizens on the way, and from the avails of their exhibitions in the towns through which they passed; in which, arrayed in their national costume, they exhibited their peculiar dances, and native implements of war and music. What was wanting, in addition to these sources, had been supplied by borrowing from individuals.

Martell, who acted as their conductor and interpreter, brought private letters from several persons to members of Congress and others, which procured respect. After a visit, protracted through seven or eight weeks, an act was passed by Congress to defray the expenses of the party, including the repayment of the sums borrowed of citizens, and sufficient to carry them back, with every requisite comfort, to their homes in the north-west. While in Washington, the presence of the party at private houses, at levees, and places of public resort, and at the halls of Congress, attracted much interest; and this was not a little heightened by their aptness in the native ceremonies, dancing, and their orderly conduct and easy manners, united to the attraction of their neat and well-preserved costume, which helped forward the object of their mission.

The visit, although it has been stated, from respectable sources, to have had its origin wholly in private motives, in the carrying out of which the natives were made to play the part of mere subordinates, was concluded in a manner which reflects the highest credit on the liberal feelings and sentiments of Congress. The plan of retrocession of territory, on which some of the natives expressed a wish to settle and adopt the modes of civilized life, appeared to want the sanction of the several states in which the lands asked for lie. No action upon it could therefore be well had, until the legislatures of these states could be consulted (pg. 414-416, pictographic plates follow).

I have always had trouble with Schoolcraft’s interpretation of these events. It wasn’t that I had evidence to contradict his argument, but rather that I had a hard time believing that all these chiefs would make so weighty a decision as to go to Washington simply because their interpreter was trying to get rich. The petitions asked for a permanent homeland in the traditional villages east of the Mississippi. This was the major political goal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe leadership at that time and would remain so in all the years leading up to 1854. Furthermore, chiefs continued to ask for, or go “uninvited” on, diplomatic missions to the president in the years that followed.

I explored some of this in the post about the pictograph, but a number of lingering questions remained:

What route did this group take to Washington?

Who was Major John Baptiste Martell?

Did he manipulate the chiefs into working for him, or was he working for them?

Was the Naaganab who went with this group the well-known Fond du Lac chief or the warrior from Lake Chetek with the same name?

Did any chiefs from the La Pointe band go?

Why was Martell criticized so much? Did he steal the money?

What became of Martell after the expedition?

How did the “Martell Expedition” of 1848-49 impact the Ojibwe removal of 1850-51?

Lacking access to the really good archives on this subject, I decided to focus on newspapers, and since this expedition received so much attention and publicity, this was a good choice. Enjoy:

Indiana Palladium. Vevay, IN. Dec. 2, 1848

Capt. Seth Eastman of the U.S. Army took note of the delegation as it traveled down the Mississippi from Fort Snelling to St. Louis. Eastman, a famous painter of American Indians, copied the birch bark petitions for publication in the works of his collaborator Henry Schoolcraft. At least one St. Louis paper also noticed these unique pictographic documents.

Lafayette Courier. Lafayette, IN. Dec. 8, 1848.

Lafayette Courier. Lafayette, IN. Dec. 8, 1848.

The delegation made its way up the Ohio River to Cincinnati, where Gezhiiyaash’s illness led to a chance encounter with some Ohio Freemasons. I won’t repeat it here, but I covered this unusual story in this post from August.

At Cincinnati, they left the river and headed toward Columbus. Just east of that city, on the way to Pittsburgh, one of the Ojibwe men offered some sound advice to the women of Hartford, Ohio, but he received only ridicule in return.

Madison Weekly Courier. Madison, IN. Jan. 24, 1849

It’s unclear how quickly reports of the delegation came back to the Lake Superior country. William Warren’s letter to his cousin George, written in March after the delegation had already left Washington, still spoke of St. Louis:

William W. Warren (Wikimedia Images)

“…About Martells Chiefs. They were according to last accounts dancing the pipe dance at St. Louis. They have been making monkeys of themselves to fill the pockets of some cute Yankee who has got hold of them. Black bird returned from Cleveland where he caught scarlet fever and clap. He has behaved uncommon well since his return…” (Schenck, pg. 49)

From this letter, we learn that Blackbird, the La Pointe chief, was originally part of the group. In evaluating Warren’s critical tone, we must remember that he was working closely with the very government officials who withheld their permission. Of the La Pointe chiefs, Blackbird was probably the least accepting of American colonial power. However, we see in the obituary of Naaganab, Blackbird’s rival at the 1855 annuity payment, that the Fond du Lac chief was also there.

New York World. New York. July 22, 1894

Before finding this obituary, I had thought that the Naaganab who signed the petition was more likely the headman from Lake Chetek. Instead, this information suggests it was the more famous Fond du Lac chief. This matters because in 1848, Naaganab was considered the speaker for his cousin Zhingob, the leading chief at Fond du Lac. Blackbird, according to his son James, was the pipe carrier for Buffalo. While these chiefs had their differences with each other, it seems likely that they were representing their bands in an official capacity. This means that the support for this delegation was not only from “minor chiefs” as Schoolcraft described them, or “Martells Chiefs” as Warren did, from Lac du Flambeau and Michigan. I would argue that the presence of Blackbird and Naaganab suggests widespread support from the Lake Superior bands. I would guess that there was much discussion of the merits of a Washington delegation by Buffalo and others during the summer of 1848, and that the trip being a hasty money-making scheme by Martell seems much less likely.

Madison Daily Banner. Madison, IN. Jan. 3, 1849.

From Pittsburgh, the delegation made it to Philadelphia, and finally Washington. They attracted a lot of attention in the nation’s capital. Some of their adventures and trials: Oshkaabewis and his wife Pammawaygeonenoqua losing an infant child, the group hunting rabbits along the Potomac, and the chiefs taking over Congress, are included this post from March, so they aren’t repeated here.

Adams Sentinel. Gettysburg, PA. Feb. 5, 1849.

According to Ronald Satz, the delegation was received by both Congress and President Polk with “kindly feelings” and the expectation of “good treatment in the future” if they “behaved themselves (Satz 51).” Their petition was added to the Congressional Record, but the reservations were not granted at the time. However, Congress did take up the issue of paying for the debts accrued by the Ojibwe along the way.

George Copway (Wikimedia Commons)

Kah-Ge-Ga-Gah-Bowh (George Copway), a Mississauga Ojibwe and Methodist missionary, was the person “belonging to one of the Canada Bands of Chippewas,” who wrote the anti-Martell letter to Indian Commissioner William Medill. This is most likely the letter Schoolcraft referred to in 1851. In addition to being upset about the drinking, Copway was against reservations in Wisconsin. He wanted the government to create a huge pan-Indian colony at the headwaters of the Missouri River.

William Medill (Wikimedia Commons)

Iowa State Gazette. Burlington, IA. April 4, 1849

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Feb. 28, 1849.

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Feb. 28, 1849.

With $6000 (or did they only get $5000?), a substantial sum for the antebellum Federal Government, the group prepared to head back west with the ability to pay back their creditors.

It appears the chiefs returned to their villages by going back though the Great Lakes to Green Bay and then overland.

The Chippewa Delegation, who have been on a visit to see their “great fathers” in Washington, passed through this place on Saturday last, on their way to their homes near Lake Superior. From the accounts of the newspapers, they have been lionized during their whole journey, and particularly in Washington, where many presents were made them, among the most substantial of which was six boxed of silver ($6,000) to pay their expenses. They were loaded with presents, and we noticed one with a modern style trunk strapped to his back. They all looked well and in good spirits (qtd. in Paap, pg. 205).

Green Bay Gazette. April 4, 1849

So, it hardly seems that the Ojibwe chiefs returned to their villages feeling ripped off by their interpreter. Martell himself returned to the Soo, and found a community about to be ravaged by a epidemic of cholera.

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Sep. 5, 1849.

Martell appears in the 1850 census on the record of those deceased in the past year. Whether he was a major in the Mexican War, whether he was in the United States or Canadian military, or whether it was even a real title, remains a mystery. His death record lists his birthplace as Minnesota, which probably connects him to the Martells of Red Lake and Red River, but little else is known about his early years. And while we can’t say for certain whether he led the group purely out of self-interest, or whether he genuinely supported the cause, John Baptiste Martell must be remembered as a key figure in the struggle for a permanent Ojibwe homeland in Wisconsin and Michigan. He didn’t live to see his fortieth birthday, but he made the 1848-49 Washington delegation possible.

So how do we sort all this out?

To refresh, my unanswered questions from the other posts about this delegation were:

1) What route did this group take to Washington?

2) Who was Major John Baptiste Martell?

3) Did he manipulate the chiefs into working for him, or was he working for them?

4) Was the Naaganab who went with this group the well-known Fond du Lac chief or the warrior from Lake Chetek with the same name?

5) Did any chiefs from the La Pointe band go?

6) Why was Martell criticized so much? Did he steal the money?

7) What became of Martell after the expedition?

8) How did the “Martell Expedition” of 1848-49 impact the Ojibwe removal of 1850-51?

We’ll start with the easiest and work our way to the hardest. We know that the primary route to Washington was down the Brule, St. Croix, and Mississippi to St. Louis, and from there up the Ohio. The return trip appears to have been via the Great Lakes.

We still don’t know how Martell became a major, but we do know what became of him after the diplomatic mission. He didn’t survive to see the end of 1849.

The Fond du Lac chief Naaganab, and the La Pointe chief Blackbird, were part of the group. This indicates that a wide swath of the Lake Superior Ojibwe leadership supported the delegation, and casts serious doubt on the notion that it was a few minor chiefs in Michigan manipulated by Martell.

Until further evidence surfaces, there is no reason to support Schoolcraft’s accusations toward Martell. Even though these allegations are seemingly validated by Warren and Copway, we need to remember how these three men fit into the story. Schoolcraft had moved to Washington D.C. by this point and was no longer Ojibwe agent, but he obviously supported the power of the Indian agents and favored the assimilation of his mother-in-law’s people. Copway and Warren also worked closely with the Government, and both supported removal as a way to separate the Ojibwe from the destructive influences of the encroaching white population. These views were completely opposed to what the chiefs were asking for: permanent reservations at the traditional villages. Because of this, we need to consider that Schoolcraft, Warren, and Copway would be negatively biased toward this group and its interpreter.

Finally there’s the question Howard Paap raises in Red Cliff, Wisconsin. How did this delegation impact the political developments of the early 1850s? In one sense the chiefs were clearly pleased with the results of the trip. They made many friends in Congress, in the media, and in several American cities. They came home smiling with gifts and money to spread to their people. However, they didn’t obtain their primary goal: reservations east of the Mississippi, and for this reason, the following statement in Schoolcraft’s account stands out:

The plan of retrocession of territory, on which some of the natives expressed a wish to settle and adopt the modes of civilized life, appeared to want the sanction of the several states in which the lands asked for lie. No action upon it could therefore be well had, until the legislatures of these states could be consulted.

“Kindly feelings” from President Polk didn’t mean much when Zachary Taylor and a new Whig administration were on the way in. Meanwhile, Congress and the media were so wrapped up in the national debate over slavery that they forgot all about the concerns of the Ojibwes of Lake Superior. This allowed a handful of Indian Department officials, corrupt traders, and a crooked, incompetent Minnesota Territorial governor named Alexander Ramsey to force a removal in 1850 that resulted in the deaths of 400 Ojibwe people in the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

It is hard to know how the chiefs felt about their 1848-49 diplomatic mission after Sandy Lake. Certainly their must have been a strong sense that they were betrayed and abandoned by a Government that had indicated it would support them, but the idea of bypassing the agents and territorial officials and going directly to the seat of government remained strong. Another, much more famous, “uninvited” delegation brought Buffalo and Oshogay to Washington in 1852, and ultimately the Federal Government did step in to grant the Ojibwe the reservations. Almost all of the chiefs who made the journey, or were shown in the pictographs, signed the Treaty of 1854 that made them.

Sources:

McClurken, James M., and Charles E. Cleland. Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights / James M. McClurken, Compiler ; with Charles E. Cleland … [et Al.]. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State UP, 2000. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Seth Eastman. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Collected and Prepared under the Direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per Act of Congress of March 3rd, 1847. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo, 1851. Print.

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Capitol Busts

July 17, 2013

This post is one of several that seek to determine how many images exist of Great Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855. To learn why this is necessary, please read this post introducing the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

Posts on Chequamegon History are generally of the obscure variety and are probably only interesting to a handful of people. I anticipate this one could cause some controversy as it concerns an object that holds a lot of importance to many people who live in our area. All I can say about that is that this post represents my research into original historical documents. I did not set out to prove anybody right or wrong, and I don’t think this has to be the last word on the subject. This post is simply my reasoned conclusions based on the evidence I’ve seen. Take from it what you will.

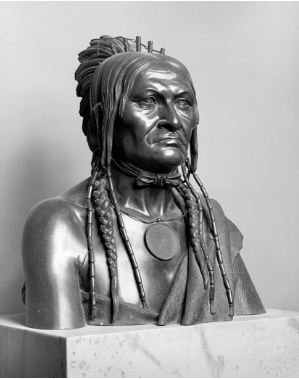

Be sheekee, or Buffalo by Francis Vincenti, Marble, Modeled 1855, Carved 1856 (United States Senate)

Be Sheekee: A Chippewa Warrior from the Sources of the Mississippi, bronze, by Joseph Lassalle after Francis Vincenti, House wing of the United States Capitol (U.S. Capitol Historical Society).

“A Chippewa Warrior from the Sources of the Mississippi”

There is no image that has been more widely identified with Chief Buffalo from La Pointe than the marble bust and bronze copy in the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington D.C. Red Cliff leaders make a point of visiting the statues on trips to the capital city, the tribe uses the image in advertising and educational materials, and literature from the United States Senate about the bust includes a short biography of the La Pointe chief.

I can trace the connection between the bust and the La Pointe chief to 1973, when John O. Holzhueter, editor of the Wisconsin Magazine of History wrote an article for the magazine titled Chief Buffalo and Other Wisconsin-Related Art in the National Capitol. From Holzhueterʼs notes we can tell that in 1973, the rediscovery of the story of the La Pointe Buffalo was just beginning at the Wisconsin Historical Society (the publisher of the magazine). Holzhueter deserves credit for helping to rekindle interest in the chief. However, he made a critical error.

In the article he briefly discusses Eshkibagikoonzhe (Flat Mouth), the chief of the Leech Lake or Pillager Ojibwe from northern Minnesota. Roughly the same age as Buffalo, Flat Mouth is as prominent a chief in the history of the upper Mississippi as Buffalo is for the Lake Superior bands. Had Holzhueter investigated further into the life of Flat Mouth, he may have discovered that at the time the bust was carved, the Pillagers had another leader who had risen to prominence, a war chief named Buffalo.

Holzhueter clearly was not aware that there was more than one Buffalo, and thus, he had to invent facts to make the history fit the art. According to the article (and a book published by Holzhueter the next year) the La Pointe Buffalo visited President Pierce in Washington in January of 1855. Buffalo did visit Washington in 1852 in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, but the old chief was nowhere near Washington in 1855. In fact, he was at home on the island in declining health having secured reservations for his people in Wisconsin the previous summer. He would die in September of 1855. The Buffalo who met with Pierce, of course, was the war chief from Leech Lake.

“He wore in his headdress 5 war-eagle feathers“

The Pillager Buffalo was in Washington for treaty negotiations that would transfer most of the remaining Ojibwe land in northern Minnesota to the United States and create reservations at the principal villages. The minutes of the February 1855 negotiations between the Minnesota chiefs and Indian Commissioner George Manypenny are filled with Ojibwe frustration at Manypennyʼs condescending tone. The chiefs, included the powerful young Hole-in-the-Day, the respected elder Flat Mouth, and Buffalo, who was growing in experience and age, though he was still considerably younger than Flat Mouth or the La Pointe Buffalo. The men were used to being called “red children” in communications with their “fathers” in the government, but Manypennyʼs paternalism brought it to a new low. Buffalo used his clothing to communicate to the commissioner that his message of assimilation to white ways was not something that all Ojibwes desired. Manypennyʼs words and Buffaloʼs responses as interpreted by the mix- blooded trader Paul Beaulieu follow:

The commissioner remarked to Buffalo, that if he was a young man he would insist upon his dispensing with his headdress of feathers, but that, as he was old, he would not disturb a custom which habit had endeared to him.

Buffalo repoled ithat the feathered plume among the Chippewas was a badge of honor. Those who were successful in fighting with or conquering their enemies were entitled to wear plumes as marks of distinction, and as the reward of meritorious actions.The commissioner asked him how old he was.

Buffalo said that was a question which he could not answer exactly. If he guessed right, however, he supposed he was about fifty. (He looked, and was doubtless, much

older).Commissioner. I would think, my firend, you were older than that. I would like to philosophise with you about that headdress, and desired to know if he had a farm, a house, stock, and other comforts about him.

Buffalo. I have none of those things which you have mentioned. I live like other members of the tribe.

Commissioner. How long have you been in the habit of painting—thirty years or more?

Buffalo. I can not tell the number of years. It may have been more or it may have been less. I have distinguished myself in war as well as in peace among my people and the whites, and am entitled to the distinction which the practice implies.

Commissioner. While you, my firend, have been spending your time and money in painting your face, how many of your white brothers have started without a dollar in the world and acquired all those things mentioned so necessary to your comfort and independent support. The paint, with the exception of what is now on my friend’s face, has disappeared, but the white persons to whom I alluded by way of contrast are surrounded by all the comforts of life, the legitimate fruits of their well-directed industry. This illustrates the difference between civilized and savage life, and the importance of our red brothers changing their habits and pursuits for those of the white.

Major General Montgomery C. Meigs was a Captain before the Civil War and was in charge of the Capitol restoration, As with Thomas McKenney in the 1820s, Meigs was hoping to capture the look of the “vanishing Indian.” He commissioned the busts of the Leech Lake chiefs during the 1855 Treaty negotiations. (Wikimedia Images)

While Manypenny clearly did not like the Ojibwe way of life or Buffaloʼs style of dress, it did catch the attention of the authorities in charge of building an extension on the U.S. Capitol. Captain Montgomery Meigs, the supervisor, had hired numerous artists and much like Thomas McKenney two decades earlier, was looking for examples of the indigenous cultures that were assumed to be vanishing. On February 17th, Meigs received word from Seth Eastman that the Ojibwe delegation was in town.

The Captain met Bizhiki and described him in his journal:

“He is a fine-looking Indian, with character strongly marked. He wore in his headdress 5 war-eagle feathers, the sign of that many enemies put to death by his hand, and sat up, an old murderer, as proud of his feathers as a Frenchman of his Cross of the Legion of Honor. He is a leading warrior rather than a chief, but he has a good head, one which would not lead one, if he were in the Senate, to think he was not fit to be the companion of the wise of the land.”

Buffalo was paid $5.00 and sat for three days with the skilled Italian sculptor Francis Vincenti. Meigs recorded:

“Vincenti is making a good likeness of a fine bust of Buffalo. I think I will have it put into marble and placed in a proper situation in the Capitol as a record of the Indian culture. 500 years hence it will be interesting.”

Vincenti first formed clay models of both Buffalo and Flat Mouth. The marbles would not be finished until the next year. A bronze replica of Buffalo was finished by Joseph Lassalle in 1859. The marble was put into the Senate wing of the Capitol, and the bronze was placed in the House wing.

Clues in the Marble

The sculptures themselves hold further clues that the man depicted is not the La Pointe Buffalo. Multiple records describe the La Pointe chief as a very large man. In his obituary, recorded the same year the statue was modeled, Morse writes:

Any one would recognize in the person of the Buffalo chief, a man of superiority. About the middle height, a face remarkably grave and dignified, indicating great thoughtfulness; neat in his native attire; short neck, very large head, and the most capacious chest of any human subject we ever saw.

At the time of his death, he was thought to have been over ninety years old. The man in the sculpture is lean and not ninety. In addition, there is another clue that got by Holzhueter even though he printed it in his article. There is a medallion around the neck of the bronze bust that reads, “Beeshekee, the BUFFALO; A Chippewa Warrior from the Sources of the Mississippi…” This description works for a war chief from Leech Lake, but makes no sense for a civil chief and orator from La Pointe.

Another Image of the Leech Lake Bizhiki

The Treaty of 1855 was signed on February 22, and the Leech Lake chiefs returned to Minnesota. By the outbreak of the Civil War, Flat Mouth had died leaving Buffalo as the most prominent Pillager chief. Indian-White relations in Minnesota grew violent in 1862 as the U.S.- Dakota War (also called the Sioux Uprising) broke out in the southern part of the state. The Gull Lake chief, Hole in the Day, who had claimed the title of head of the Ojibwes, was making noise about an Ojibwe uprising as well. When he tried to use the Pillagers in his plan, Buffalo voiced skepticism and Hole in the Dayʼs plans petered out. In 1863, Buffalo returned to Washington for a new treaty. Ironically, he was still very much alive in the midst of complicated politics in a city where his bust was on display as monument to the vanishing race.

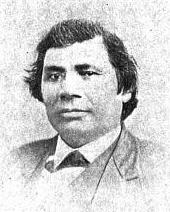

At some point during these years, the Pillager Buffalo had his photograph taken by Whitneyʼs Gallery in St. Paul. Although the La Pointe Buffalo was dead by this time, internet sites will occasional connect it with him even with an original caption that reads “Head Chief of the Leech Lake Chippewas.”

The Verdict

Although it wasn’t the outcome I was hoping for, my research leads me to definitively conclude that the busts in the U.S. Capitol are of Buffalo the Leech Lake war chief. It’s disappointing for our area to lose this Washington connection, but our loss it Leech Lake’s gain. Though less well-known than the La Pointe band’s chief, their chief Buffalo should also be remembered for his role in history.

Not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe: This is Chief Buffalo from Leech Lake.

Not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe: This is Chief Buffalo from Leech Lake.

Not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe: This is Chief Buffalo from Leech Lake.

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his