Historic Sites on Chequamegon Bay

July 25, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Historical Sites on Chequamegon Bay was originally published in Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: Volume XIII, by Reuben Gold Thwaites, 1895, pages 426-440.

HISTORIC SITES ON CHEQUAMEGON BAY.1

—

BY CHRYSOSTOM VERWYST, O.S.F.

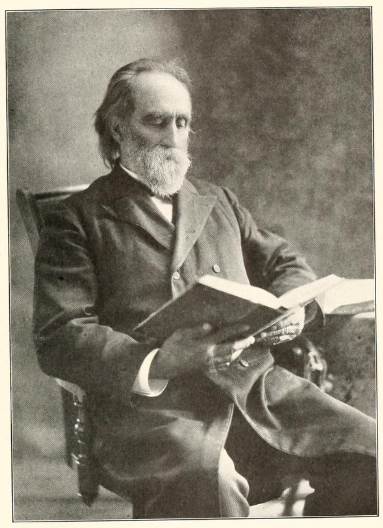

Reverend Chrysostome Verwyst, circa 1918.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

One of the earliest spots in the Northwest trodden by the feet of white men was the shore of Chequamegon Bay. Chequamegon is a corrupt form of Jagawamikong;2 or, as it was written by Father Allouez in the Jesuit Relation for 1667, Chagaouamigong. The Chippewas on Lake Superior have always applied this name exclusively to Chequamegon Point, the long point of land at the entrance of Ashland Bay. It is now commonly called by whites, Long Island; of late years, the prevailing northeast winds have caused Lake Superior to make a break through this long, narrow peninsula, at its junction with the mainland, or south shore, so that it is in reality an island. On the northwestern extremity of this attenuated strip of land, stands the government light-house, marking the entrance of the bay.

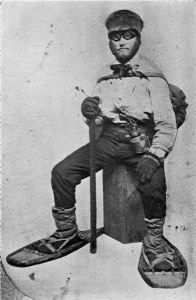

William Whipple Warren, circa 1851.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

W. W. Warren, in his History of the Ojibway Nation3, relates an Indian legend to explain the origin of this name. Menabosho, the great Algonkin demi-god, who made this earth anew after the deluge, was once hunting for the great beaver in Lake Superior, which was then but a large beaver-pond. In order to escape his powerful enemy, the great beaver took refuge in Ashland Bay. To capture him, Menabosho built a large dam extending from the south shore of Lake Superior across to Madelaine (or La Pointe) Island. In doing so, he took up the mud from the bottom of the bay and occasionally would throw a fist-full into the lake, each handful forming an island, – hence the origin of the Apostle Islands. Thus did the ancient Indians, the “Gété-anishinabeg,” explain the origin of Chequamegon Point and the islands in the vicinity. His dam completed, Menabosho started in pursuit of the patriarch of all the beavers ; he thinks he has him cornered. But, alas, poor Menabosho is doomed to disappointment. The beaver breaks through the soft dam and escapes into Lake Superior. Thence the word chagaouamig, or shagawamik (“soft beaver-dam”), – in the locative case, shagawamikong (“at the soft beaver-dam”).

Reverend Edward Jacker

~ FindAGrave.com

Rev. Edward Jacker, a well-known Indian scholar, now deceased, suggests the following explanation of Chequamegon: The point in question was probably first named Jagawamika (pr. shagawamika), meaning “there are long, far-extending breakers;” the participle of this verb is jaiagawamikag (“where there are long breakers”). But later, the legend of the beaver hunt being applied to the spot, the people imagined the word amik (a beaver) to be a constituent part of the compound, and changed the ending in accordance with the rules of their language, – dropping the final a in jagawamika, making it jagawamik, – and used the locative case, ong (jagawamikong), instead of the participial form, ag (jaiagawamikag).4

The Jesuit Relations apply the Indian name to both the bay and the projection of land between Ashland Bay and Lake Superior. our Indians, however, apply it exclusively to this point at the entrance of Ashland Bay. It was formerly nearly connected with Madelaine (La Pointe) Island, so that old Indians claim a man might in early days shoot with a bow across the intervening channel. At present, the opening is about two miles wide. The shores of Chequamegon Bay have from time immemorial been the dwelling-place of numerous Indian tribes. The fishery was excellent in the bay and along the adjacent islands. The bay was convenient to some of the best hunting grounds of Northern Wisconsin and Minnesota. The present writer was informed, a few years ago, that in Douglas county alone 2,500 deer had been killed during one short hunting season.5 How abundant must have been the chase in olden times, before the white had introduced to this wilderness his far-reaching fire-arms! Along the shores of our bay were established at an early day fur-trading posts, where adventurous Frenchmen carried on a lucrative trade with their red brethren of the forest, being protected by French garrisons quartered in the French fort on Madelaine Island.

From Rev. Henry Blatchford, an octogenarian, and John B. Denomie (Denominé), an intelligent half-breed Indian of Odanah, near Ashland, the writer has obtained considerable information as to the location of ancient and modern aboriginal villages on the shores of Chequamegon Bay. Following are the Chippewa names of the rivers and creeks emptying into the bay, where there used formerly to be Indian villages:

Charles Whittlesey documented several pictographs along the Bad River.

Mashki-Sibi (Swamp River, misnamed Bad River): Up this river are pictured rocks, now mostly covered with earth, on which in former times Indians engraved in the soft stone the images of their dreams, or the likenesses of their tutelary manitous. Along this river are many maple-groves, where from time immemorial they have made maple-sugar.

Makodassonagani-Sibi (Bear-trap River), which emptties into the Kakagon. The latter seems in olden times to have been the regular channel of Bad River, when the Bad emptied into Ashland Bay, instead of Lake Superior, as it now does. Near the mouth of the Kakagon are large wild-rice fields, where the Chippewas annually gather, as no doubt did their ancestors, great quantities of wild rice (Manomin). By the way, wild rice is very palatable, and the writer and his dusky spiritual children prefer it to the rice of commerce, although it does not look quite so nice.

Bishigokwe-Sibiwishen is a small creek, about six miles or so east of Ashland. Bishigokwe means a woman who has been abandoned by her husband. In olden times, a French trader resided at the mouth of this creek. He suddenly disappeared, – whether murdered or not, is not known. His wife continued to reside for many years at their old home, hence the name.

Nedobikag-Sibiwishen is the Indian name for Bay City Creek, within the limits of Ashland. Here Tagwagané, a celebrated Indian chief of the Crane totem, used occasionally to reside. Warren6 gives us a speech of his, at the treaty of La Pointe in 1842. This Tagwagané had a copper plate, an heirloom handed down in his family from generation to generation, on which were rude indentations and hieroglyphics denoting the number of generations of that family which had passed away since they first pitched their lodges at Shagawamikong and took possession of the adjacent country, including Madelaine Island. From this original mode of reckoning time, Warren concludes that the ancestors of said family first came to La Pointe circa A. D. 1490.

Detail of “Ici était une bourgade considerable” from Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin, 1744.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Metabikitigweiag-Sibiwishen is the creek between Ashland and Ashland Junction, which runs into Fish Creek a short distance west of Ashland. At the junction of these two creeks and along their banks, especially on the east bank of Fish Creek, was once a large and populous Indian village of Ottawas, who there raised Indian corn. It is pointed out on N. Bellin’s map (1744)7, with the remark, Ici était une bourgade considerable (“here was once a considerable village”). We shall hereafter have occasion to speak of this place. The soil along Fish Creek is rich, formed by the annual overflowage of its water, leaving behind a deposit of rich, sand loam. There a young growth of timber along the right bank between the bay and Ashland Junction, and the grass growing underneath the trees shows that it was once a cultivated clearing. It was from this place that the trail left the bay, leading to the Chippewa River country. Fish Creek is called by the Indians Wikwedo-Sibiwishen, which means “Bay Creek,” from wikwed, Chippewa for bay; hence the name Wikwedong, the name they gave to Ashland, meaning “at the bay.”

Whittlesey Creek (National Wildlife Refuge) was named after Asaph Whittlesey, brother of Charles Whittlesey. Photo of Asaph, circa 1860.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

According to Blatchford, there was formerly another considerable village at the mouth of Whittlesey’s Creek, called by the Indians Agami-Wikwedo-Sibiwishen, which signifies “a creek on the other side of the bay,” from agaming (on the other side of a river, or lake), wikwed (a bay), and sibiwishen (a creek). I think that Fathers Allouez and Marquette had their ordinary abode at or near this place, although Allouez seems also to have resided for some time at the Ottawa village up Fish Creek.

A short distance from Whittlesey’s Creek, at the western bend of the bay, where is now Shore’s Landing, there used to be a large Indian village and trading-post, kept by a Frenchman. Being at the head of the bay, it was the starting point of the Indian trail to the St. Croix country. Some years ago the writer dug up there, an Indian mound. The young growth of timber at the bend of the bay, and the absence of stumps, indicate that it had once been cleared. At the foot of the bluff or bank, is a beautiful spring of fresh water. As the St. Croix country was one of the principal hunting grounds of the Chippewas and Sioux, it is natural there should always be many living at the terminus of the trail, where it struck the bay.

From this place northward, there were Indian hamlets strung along the western shore of the bay. Father Allouez mentions visiting various hamlets two, three, or more (French) leagues away from his chapel. Marquette mentions five clearings, where Indian villages were located. At Wyman’s place, the writer some years ago dug up two Indian mounds, one of which was located on the very bank of the bay and was covered with a large number of boulders, taken from the bed of the bay. In this mound were found a piece of milled copper, some old-fashioned hand-made iron nails, the stem of a clay pipe, etc. The objects were no doubt relics of white men, although Indians had built the mound itself, which seemed like a fire-place shoveled under, and covered with large boulders to prevent it from being desecrated.

Boyd’s Creek is called in Chippewa, Namebinikanensi-Sibiwishen, meaning “Little Sucker Creek.” A man named Boyd once resided there, married to an Indian woman. He was shot in a quarrel with another man. One of his sons resides at Spider Lake, and another at Flambeau Farm, while two of his grand-daughters live at Lac du Flambeau.

Further north is Kitchi-Namebinikani-Sibiwishen, meaning “Large Sucker Creek,” but whites now call it Bonos Creek. These two creeks are not far apart, and once there was a village of Indians there. It was noted as a place for fishing at a certain season of the year, probably in spring, when suckers and other fish would go up these creeks to spawn.

At Vanderventer’s Creek, near Washburn, was the celebrated Gigito-Mikana, or “council-trail,” so called because here the Chippewas once held a celebrated council; hence the Indian name Gigito-Mikana-Sibiwishen, meaning “Council-trail Creek.” At the mouth of this creek, there was once a large Indian village.

There used also to be a considerable village between Pike’s Bay and Bayfield. It was probably there that the celebrated war chief, Waboujig, resided.

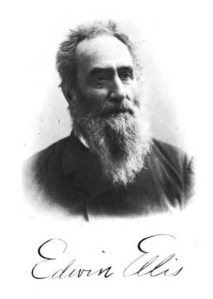

John Baptiste Denomie

~ Noble Lives of a Noble Race, A Series of Reproductions by the Pupils of Saint Mary’s, Odanah, Wisconsin, page 213-217.

There was once an Indian village where Bayfield now stands, also at Wikweiag (Buffalo Bay), at Passabikang, Red Cliff, and on Madelaine Island. The writer was informed by John B. Denomie, who was born on the island in 1834, that towards Chabomnicon Bay (meaning “Gooseberry Bay”) could long ago be seen small mounds or corn-hills, now overgrown with large trees, indications of early Indian agriculture. There must have been a village there in olden times. Another ancient village was located on the southwestern extremity of Madelaine Island, facing Chequamegon Point, where some of their graves may still be seen. It is also highly probable that there were Indian hamlets scattered along the shore between Bayfield and Red Cliff, the most northern mainland of Wisconsin. There is now a large, flourishing Indian settlement there, forming the Red Cliff Chippewa reservation. There is a combination church and school there at present, under the charge of the Franciscan Order. Many Indians also used to live on Chequamegon Point, during a great part of the year, as the fishing was good there, and blueberries were abundant in their season. No doubt from time immemorial Indians were wont to gather wild rice at the mouth of the Kakagon, and to make maple sugar up Bad River.

Illustration from The Story of Chequamegon Bay, Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: Volume XIII, 1895, page 419.

We thus see that the Jesuit Relations are correct when they speak of many large and small Indian villages (Fr. bourgades) along the shores of Chequamegon Bay. Father Allouez mentions two large Indian villages at the head of the bay – the one an Ottawa village, on Fish Creek; the other a Huron, probably between Shore’s Landing and Washburn. Besides, he mentions smaller hamlets visited by him on his sick-calls. Marquette says that the Indians lived there in five clearings, or villages. From all this we see that the bay was from most ancient times the seat of a large aboriginal population. Its geographical position towards the western end of the great lake, its rich fisheries and hunting grounds, all tended to make it the home of thousands of Indians. Hence it is much spoken of by Perrot, in his Mémoire, and by most writers on the Northwest of the last century. Chequamegon Bay, Ontonagon, Keweenaw Bay, and Sault Ste. Marie (Baweting) were the principal resorts of the Chippewa Indians and their allies, on the south shore of Lake Superior.

“Front view of the Radisson cabin, the first house built by a white man in Wisconsin. It was built between 1650 and 1660 on Chequamegon Bay, in the vicinity of Ashland. This drawing is not necessarily historically accurate.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The first white men on the shores of Chequamegon Bay were in all probability Groseilliers and Radisson. They built a fort on Houghton Point, and another at the head of the bay, somewhere between Whittlesey’s Creek and Shore’s Landing, as in some later paper I hope to show from Radisson’s narrative.8 As to the place where he shot the bustards, a creek which led him to a meadow9, I think this was Fish Creek, at the mouth of which is a large meadow, or swamp.10

After spending six weeks in the Sioux country, our explorers retraced their steps to Chequamegon Bay, arriving there towards the end of winter. They built a fort on Houghton Point. The Ottawas had built another fort somewhere on Chequamegon Point. In travelling towards this Ottawa fort, on the half-rotten ice, Radisson gave out and was very sick for eight days; but by rubbing his legs with hot bear’s oil, and keeping them well bandaged, he finally recovered. After his convalescence, our explorers traveled northward, finally reaching James Bay.

The next white men to visit our bay were two Frenchmen, of whom W. W. Warren says:11

“One clear morning in the early part of winter, soon after the islands which are clustered in this portion of Lake Superior, and known as the Apostles, had been locked in ice, a party of young men of the Ojibways started out from their village in the Bay of Shag-a-waum-ik-ong [Chequamegon], to go, as was customary, and spear fish through holes in the ice, between the island of La Pointe and the main shore, this being considered as the best ground for this mode of fishing. While engaged in this sport, they discovered a smoke arising from a point of the adjacent island, toward its eastern extremity.

“The island of La Pointe was then totally unfrequented, from superstitious fears which had but a short time previous led to its total evacuation by the tribe, and it was considered an act of the greatest hardihood for any one to set foot on its shores. The young men returned home at evening and reported the smoke which they had seen arising from the island, and various were the conjectures of the old people respecting the persons who would dare to build a fire on the spirit-haunted isle. They must be strangers, and the young men were directed, should they again see the smoke, to go and find out who made it.

“Early the next morning, again proceeding to their fishing-ground, the young men once more noticed the smoke arising from the eastern end of the unfrequented island, and, again led on by curiosity, they ran thither and found a small log cabin, in which they discovered two white men in the last stages of starvation. The young Ojibways, filled with compassion, carefully conveyed them to their village, where being nourished with great kindness, their lives were preserved.

“These two white men had started from Quebec during the summer with a supply of goods, to go and find the Ojibways who every year had brought rich packs of beaver to the sea-coast, notwithstanding that their road was barred by numerous parties of the watchful and jealous Iroquois. Coasting slowly up the southern shores of the Great Lake late in the fall, they had been driven by the ice on to the unfrequented island, and not discovering the vicinity of the Indian village, they had been for some time enduring the pangs of hunger. At the time they were found by the young Indians, they had been reduced to the extremity of roasting and eating their woolen cloth and blankets as the last means of sustaining life.

“Having come provided with goods they remained in the village during the winter, exchanging their commodities for beaver skins. They ensuing spring a large number of the Ojibways accompanied them on their return home.

“From close inquiry, and judging from events which are said to have occurred about this period of time, I am disposed to believe that this first visit by the whites took place about two hundred years ago [Warren wrote in 1852]. It is, at any rate, certain that it happened a few years prior to the visit of the ‘Black-gowns’ [Jesuits] mentioned in Bancroft’s History, and it is one hundred and eighty-four years since this well-authenticated occurrence.”

So far Warren; he is, however, mistaken as to the date of the first black-gown’s visit, which was not 1668 but 1665.

Portrayal of Claude Allouez

~ National Park Service

The next visitors to Chequamegon Bay were Père Claude Allouez and his six companions in 1665. We come now to a most interesting chapter in the history of our bay, the first formal preaching of the Christian religion on its shores. For a full account of Father Allouez’s labors here, the reader is referred to the writer’s Missionary Labors of Fathers Marquette, Allouez, and Ménard in the Lake Superior Region. Here will be given merely a succinct account of their work on the shores of the bay. To the writer it has always been a soul-inspiring thought that he is allowed to tread in the footsteps of those saintly men, who walked, over two hundred years ago, the same ground on which he now travels; and to labor among the same race for which they, in starvation and hardship, suffered so much.

In the Jesuit Relation for 1667, Father Allouez thus begins the account of his five years’ labors on the shores of our bay:

“On the eight of August of the year 1665, I embarked at Three Rivers with six Frenchmen, in company with more than four hundred Indians of different tribes, who were returning to their country, having concluded the little traffic for which they had come.”

Marquis Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy

~ Wikipedia.org

His voyage into the Northwest was one of the great hardships and privations. The Indians willingly took along his French lay companions, but him they disliked. Although M. Tracy, the governor of Quebec, had made Father Allouez his ambassador to the Upper Algonquins, thus to facilitate his reception in their country, nevertheless they opposed him accompanying them, and threatened to abandon him on some desolate island. No doubt the medicine-men were the principal instigators of this opposition. He was usually obliged to paddle like the rest, often till late in the night, and that frequently without anything to eat all day.

“On a certain morning,” he says, “a deer was found, dead since four or five days. It was a lucky acquisition for poor famished beings. I was offered some, and although the bad smell hindered some from eating it, hunger made me take my share. But I had in consequence an offensive odor in my mouth until the next day. In addition to all these miseries we met with, at the rapids I used to carry packs as large as possible for my strength; but I often succumbed, and this gave our Indians occasion to laugh at me. They used to make fun of me, saying a child ought to be called to carry me and my baggage.”

August 24, they arrived at Lake Huron, where they made a short stay; then coasting along the shores of that lake, they arrived at Sault Ste. Marie towards the beginning of September. September 2, they entered Lake Superior, which the Father named Lake Tracy in acknowledgement of the obligations which the people of those upper countries owed to the governor. Speaking of his voyage on Lake Superior, Father Allouez remarks:

“Having entered Lake Tracy, we were engaged the whole month of September in coasting along the south shore. I had the consolation of saying holy mass, as I now found myself alone with our Frenchmen, which I had not been able to do since my departure from Three Rivers. * * * We afterwards passed the bay, called by the aged, venerable Father Ménard, Sait Theresa [Keweenaw] Bay.”

Speaking of his arrival at Chequamegon Bay, he says:

“After having traveled a hundred and eighty leagues on the south shore of Lake Tracy, during which our Saviour often deigned to try our patience by storms, hunger, daily and nightly fatigues, we finally, on the first day of October, 1665, arrived at Chagaouamigong, for which place we had sighed so long. It is a beautiful bay, at the head of which is situated the large village of the Indians, who there cultivate fields of Indian corn and do not lead a nomadic life. There are at this place men bearing arms, who number about eight hundred; but these are gathered together from seven different tribes, and live in peacable community. This great number of people induced us to prefer this place to all others for our ordinary abode, in order to attend more conveniently to the instruction of these heathens, to put up a chapel there and commence the functions of Christianity.”

Further on, speaking of the site of his mission and its chapel, he remarks:

“The section of the lake shore, where we have settled down, is between two large villages, and is, as it were, the center of all the tribes of these countries, because the fishing here is very good, which is the principal source of support of these people.”

To locate still more precisely the exact site of his chapel, he remarks, speaking of the three Ottawa clans (Outaouacs, Kiskakoumacs, and Outaoua-Sinagonc):

“I join these tribes [that is, speaks of them as one tribe] because they had one and the same language, which is the Algonquin, and compose one of the same village, which is opposite that of the Tionnontatcheronons [Hurons of the Petun tribe] between which villages we reside.”

But where was that Ottawa village? A casual remark of Allouez, when speaking of the copper mines of Lake Superior, will help us locate it.

“It is true,” says he, “on the mainland, at the place where the Outaouacs raise Indian corn, about half a league from the edge of the water, the women have sometimes found pieces of copper scattered here and there, weighing ten, twenty or thirty pounds. It is when digging into the sand to conceal their corn that they make these discoveries.”

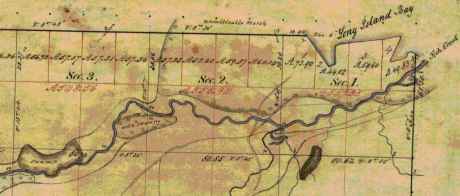

Detail of Fish Creek from Township 47 North Range 5 West.

~ Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records

Allouez evidently means Fish Creek. About a mile or so from the shore of the bay, going up this creek, can be seen traces of an ancient clearing on the left-hand side, where Metabikitigweiag Creeek empties into Fish Creek, about half-way between Ashland and Ashland Junction. The writer examined the locality about ten years ago. This then is the place where the Ottawas raised Indian corn and had their village. In Charlevoix’s History of New France, the same place is marked as the site of an ancient large village. The Ottawa village on Fish Creek appears to have been the larger of the two at the head of Chequamegon Bay, and it was there Allouez resided for a time, until he was obliged to return to his ordinary dwelling place, “three-fourths of a league distant.” This shows that the ordinary abode of Father Allouez and Marquette, the site of their chapel, was somewhere near Whittlesey’s Creek or Shore’s Landing. The Huron village was most probably along the western shore of the bay, between Shore’s Landing and Washburn.

Detail of Ashland next to an ancient large village (unmarked) in Township 47 North Range 4 West.

~ Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records

Father Allouez did not confine his apostolic labors to the two large village at the head of the bay. He traveled all over the neighborhood, visiting the various shore hamlets, and he also spent a month at the western extremity of Lake Superior – probably at Fond du Lac – where he met with some Chippewas and Sioux. In 1667 he crossed the lake, most probably from Sand Island, in a frail birch canoe, and visited some Nipissirinien Christians at Lake Nepigon (Allimibigong). The same year he went to Quebec with an Indian flotilla, and arrived there on the 3d of August, 1667. After only two days’ rest he returned with the same flotilla to his far distant mission on Chequamegon Bay, taking along Father Louis Nicholas. Allouez contained his missionary labors here until 1669, when he left to found St. Francis Xavier mission at the head of Green Bay. His successor at Chequamegon Bay was Father James Marquette, discoverer and explorer of the Mississippi. Marquette arrived here September 13, 1669, and labored until the spring of 1671, when he was obliged to leave on account of the war which had broken out the year before, between the Algonquin Indians at Chequamegon Bay and their western neighbors, the Sioux.

1 – See ante, p. 419 for map of the bay. – ED.

2 – In writing Indian names, I follow Baraga’s system of orthography, giving the French quality to both consonants and vowels.

3 – Minn. Hist. Colls., v. – ED.

4 – See ante, p. 399, note. – ED.

5 – See Carr’s interesting and exhaustive article, “The Food of Certain American Indians,” in Amer. Antiq. Proc., x., pp. 155 et seq. – ED.

6 – Minn. Hist. Colls., v. – ED.

7 – In Charlevoix’s Nouvelle France. – ED.

8 – See Radisson’s Journal, in Wis. Hist. Colls., xi. Radisson and Groseilliers reached Chequamegon Bay late in the autumn of 1661. – ED.

9 – Ibid., p. 73: “I went to the wood some 3 or 4 miles. I find a small brooke, where I walked by ye sid awhile, wch brought me into meddowes. There was a poole, where weare a good store of bustards.” – ED.

10 – Ex-Lieut. Gov. Sam. S. Fifield, of Ashland, writes me as follows:

“After re-reading Radisson’s voyage to Bay Chewamegon, I am satisfied that it would by his description be impossible to locate the exact spot of his camp. The stream in which he found the “pools,” and where he shot fowl, is no doubt Fish Creek, emptying into the bay at its western extremity. Radisson’s fort must have been near the head of the bay, on the west shore, probably at or near Boyd’s Creek, as there is an outcropping of rock in that vicinity, and the banks are somewhat higher than at the head of the bay, where the bottom lands are low and swampy, forming excellent “duck ground” even to this day. Fish Creek has three outlets into the bay, – one on the east shore or near the east side, one central, and one near the western shore; for full two miles up the stream, it is a vast swamp, through which the stream flows in deep, sluggish lagoons. Here, in the early days of American settlement, large brook trout were plenty; and even in my day many fine specimens have been taken from these “pools.” Originally, there was along these bottoms a heavy elm forest, mixed with cedar and black ash, but it has now mostly disappeared. An old “second growth,” along the east side, near Prentice Park, was evidently once the site of an Indian settlement, probably of the 18th century.

“I am of the opinion that the location of Allouez’s mission was at the mouth of Vanderventer’s Creek, on the west shore of the bay, near the present village of Washburn. It was undoubtedly once the site of a large Indian village, as was the western part of the present city of Ashland. When I came to this locality, nearly a quarter of a century ago, “second growth” spots could be seen in several places, where it was evident that the Indians had once had clearings for their homes. The march of civilization has obliterated these landmarks of the fur-trading days, when the old French voyageurs made the forest-clad shores of our beautiful bay echo with their boat songs, and when resting from their labors sparked the dusky maidens in their wigwams.”

Rev. E. P. Wheeler, of Ashland, a native of Madelaine Island, and an authority on the region, writes me:

“I think Radisson’s fort was at the mouth of Boyd’s Creek, – at least that place seems for the present to fulfill the conditions of his account. it is about three or four miles from here to Fish Creek valley, which leads, when followed down stream, to marshes ‘meadows, and a pool.’ No other stream seems to have the combination as described. Boyd’s Creek is about four miles from the route he probably took, which would be by way of the plateau back from the first level, near the lake. Radisson evidently followed Fish Creek down towards the lake, before reaching the marshes. This condition is met by the formation of the creek, as it is some distance from the plateau through which Fish Creek flows to its marshy expanse. Only one thing makes me hesitate about coming to a final decision, – that is, the question of the age of the lowlands and formations around Whittlesey Creek. I am going to go over the ground with an expert geologist, and will report later. Thus far, there seems to be no reason to doubt that Fish Creek is the one upon which Radisson hunted.” – ED.

11 – Minn. Hist. Colls., v., pp. 121, 122, gives the date as 1652. – ED.

Penokee Survey Incidents: Number V

March 4, 2015

By Amorin Mello

The Survey of the Penoka Range and Incidents Connected with its Early History.

—

Number V.

~ History of Milwaukee, pg. 358

Friend Fifield:- The reader will no doubt remember that my last left us all anxiously awaiting the completion of the township surveys, which, up to this time, we had hoped would have been accomplished as soon, at least, as we were ready on our part, to “prove up.” But still the work lagged, and instead of being through and home in three months, as at first anticipated, it was now plainly seen that such was not to be the case. Three months had already elapsed since the work was commenced, yet the goal was apparently as far distant as over, and as we could not discharge our men, it was finally decided to explore the country south and west of the Range for the purpose of ascertaining, as far as possible, its adaption for a railroad from Milwaukee to the Range, as well as from the Range to Ashland, the latter of which must, of necessity, be built to move the iron. And in order that it might be properly done, Mr. Albert W. Whitcomb, a civil engineer of considerable experience, was sent up from Milwaukee, to superintend the work, who, after making one trip to the Range returned to Ashland and commenced his work by running what was afterwards known as the “Transit Line,” on account of its being run with that instrument. This line followed principally what was known as the Coburn Trail, which was the only one in use at that time by the company; crossing White River at Welton‘s mill, the Marengo at Sibley‘s, (now Martin Rhiem‘s.) and the outlet of Dr. Brunschweiler‘s old copper location, and thence to Ashland “Pond.” When it became evident that no good route could be found from that point to the Range on account of the heavy grades to be overcome, the work by transit was abandoned, and the balance was run by compass and chain only, simply to ascertain the exact distance in miles. This work, which should under ordinary circumstances, have been completed in ten days, occupied over a month, besides involving a large expenditure of money which might as well have been sunk in the ocean, as far as the Company was concerned, as no benefit whatever resulted from it except to the men employed in the work.

Palmer’s townsite claim located near Penokee Gap on Bad River with the “Coburn Trail” to Ashland. (Detail from Stuntz’s survey during May of 1858)

Subsequent, however, to the close of the survey upon the Transit Line, and the return of Mr. Whitcomb to Milwaukee, several extensive explorations were made to the south and west of the Range, by Gen. Cutler and myself, accompanied by Wheelock, Chas. Stevens, French Joe, (Joe Le Roy, with Big Joe as packer, and a Halfbreed called Little Alic as cook.) in one case nearly to the head waters of the Chippewa. These explorations, which were made with compass and chain, were by far the pleasantest part of my labors that summer, relieving us, as they did, not only of the monotony of camp life while awaiting the completion of the survey, but they also added largely to our knowledge of the topography, as well as the resources of the country south of the Range, then an unbroken wilderness, filled with beaver ponds, many of which were seen, but which is today, thanks to the energy and business tact of the gentlemen in charge of the Wisconsin Central railroad, beginning, metaphorically speaking, to bloom like the rose, and is destined, at no distant period, to take rank as one of the most wealthy and prosperous portions of our fair state. All honor to them for the same.

In this way our time was spent until September, when all homes of Stuntz being able to complete his work that season, unless some special providence should intervene, were abaonded, and preparations for spending the winter upon the Range were at once commenced. Gen Cutler immediately left for Milwaukee after additional supplies, first placing me in charge of the work. A pack train consisting of Stuntz’s pony, (old Jack) and Bascom‘s mare, were at once put upon the trail, in charge of Geo. Miller, a wild, harum-scarum Canuck from Canada West, who quickly stocked the Range with supplies.

But in order that the survey might yet be completed, if possible, additional men were put on, among whom was Wilhelm Goetzenburg, a Mechlinberger, at that time domiciled at Bay City and August Eckee, an old Courier de Bois, including all of our spare men, leaving me to keep camp at Penoka, which I did from about the middle of September to the 12th of October, during which time I saw no one except those who came in from the different claims at stated intervals, for supplies.

I see in your number of December 1, a reference by Hon. Asaph Whittlesey, to my sketch of Sibley and Lazarus, in which he not only confirms my statement, but goes one better in assigning him the belt as the champion liar, also which belt he (Sibley) was subsequently, however, compelled to surrender to John Beck. In consequence of Mr. Whittlesey’s statement I will relate one of Sibley’s yarns, told in the presence of Gen. Cutler, myself, Wheelock and a young man from St. Paul, by the name of Fargo, while eating dinner at his house on the Marengo, in August, 1857, which not only illustrates his powers as a yarn spinner, but the wonderful acoustic properties of his ears as well; being seated at the table, Sibley at once asked a blessing upon the food, for he could pray as well as lie, after which the question was asked by some one, how far it was possible to hear the human voice, upon which Sibley stated that he had not only heard the shouts of the people, but the words of the speaker also, distinctly, that were made at a political barbeque held in Ohio, in the fall of 1844, one hundred miles distant from where he was. Mr. Fargo, although no slouch of a liar himself, was so affected by this statement as to nearly faint, and finally made the remark that if that was not a lie, it came very near it; them lugs of Sibley’s were lugs as was lugs. Can John Beck beat that?

Harvey “Harry” Fargo was a cabinet maker, George R. Stuntz’s neighbor on the Minnesota Point in Duluth, an early mail carrier, and was in the 1853 census of Superior as “Arfargo.” ~ Duluth and St. Louis County, Minnesota; Their Story and People: An Authentic Narrative of the Past, with Particular Attention to the Modern Era in the Commercial, Industrial, Educational, Civic and Social Development, Volume 1, edited by Walter Van Brunt, 1921.

I wish to state at this time, also, a little incident in connection with Eckee, mentioned above, related to me by himself, which was this: That in the fall of 1846, he, in company with three others, in the employ of the Sigourney Lumber Co., of Quebec, ascended the river of the name three hundred miles in an open boat, for the purpose of cutting timber during the winter, and that when within three miles of their journey’s end, their boat was upset in a rapid, they barely escaping with their lives, but with the loss of the boat and all its contents, axes, fishing tackle and supplies. His companions, horrified at their situation, started immediately on their return, following the sinuosities of the river. He however, chose to remain, which he did until spring, never seeing a human face for six entire months. There were four oxen and two horses at the camp the care of which he claimed, kept him from going insane. It is needless to state that his companions were never heard from again. Although this incident has no immediate connection with my history, yet it serves to illustrate the hardships to which the class of men he belonged to are often called to suffer. He could never speak of that winter and its horrors, without tears.

But to return to the Range. Although I can truthfully say that the whole time spent upon the Range was to me one of unalloyed pleasure, yet that engaged during the latter part of September and up to the 20th of October, exceeded all the rest. The forest has, at all times, a charm for me, and the autumnal months doubly so; It is then and then only that its full glories can be seen; and in no country or section of country that it has ever been my privilege to visit, is the handiwork of Dame Nature’s gelid pencil, so grandly displayed as upon Lake Superior, and more particularly is this so, in and around the Range. No doubt the good people of Ashland think the scenery at the Gap very fine, and so it is. Yet that at the west end is far more so. Here the range terminates in a bold escarpment some 300 feet above the surrounding country, giving to an observer an unobstructed view east, west and south, for forty miles.

Indian trails to the “Rockland” townsite claim overlooking English Lake and the west end of the Penoka Range. Julius Austrian later claimed the “Rockland” site for his daughter’s estate.(Detail from Stuntz’s survey from May of 1858)

This was my favorite resort in those beautiful autumn mornings, where, seated upon the edge of the bluff, I would feast my eyes for hours upon that matchless panorama. Neither could I ever divest myself of the feeling that, while there, I was alone with God. I have seen, in the course of my life, many landscape paintings that were very beautiful, but never one that could at all compare with the views I enjoyed in the months of October 1857, from the west end of the Penoka Range. J.S.B.

Penokee Survey Incidents: Number IV

February 22, 2015

By Amorin Mello

Increase Allen Lapham surveyed the Penokee Iron Range in September of 1858 for the Wisconsin & Lake Superior Mining and Smelting Company. Years later, Lapham’s experience was published as “Mountain of Iron Ore: The buried wealth of Northern Wisconsin“ in the Milwaukee Evening Wisconsin newspaper on February 21, 1887. (Image courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Geography Department)

~ 1978 Marsden Report for US Steel.

~ Railroad History, Issues 54-58, pg. 26

The Penoka Iron Range consists, as is well known, of a sharp ridge, some fifteen miles in length, by from one to one and one half in breadth, with a mean elevation of 700 feet above Lake Superior, from which is a distance about twenty-two miles, as the crow flies, its general trend being nearly east and west, it is densely covered with timber consisting of sugar maple, (of which nearly every tree is birdseye or curly) elm, red cedar, black, or yellow birch, some of which are of an enormous girth, among which are intermixed a few white pine and balsams, for it is traversed from north to south at three different points, by running streams, upon each of which the company had a station, the western being known in the vernacular of the company, as Palmer’s, (now Penoka); the center, as Lockwood’s, in honor of John Lockwood, who was at the time a prominent member of the Company, and upon its executive board; and the eastern, as Sidebotham’s, or “The Gorge.” These were the principal stations or centers, where supplies and men were always kept, and as which, as before stated, more or less work had been done the previous year. Penoka, as which the most work had been done, being considered by far the most valuable. This post was, at the time of my first visit, by charge of S.R. Marston, of whom mention was made in my last, and two young boys from Portsmouth, N.H., who had come west on exhibition, I should say, from the way they acted. They soon left, however, too many mosquitoes for them. “Lockwood’s,” as previously stated, was garrisoned by one man, whose name I have forgotten, and although a great amount of work had been done here as yet, it was nevertheless considered a very valuable claim, on account of the feasibility with which it could be reached by the rail Mr. Herbert had in contemplation to build from Ironton, and which would, in passing along the north side of the Range, come in close proximity to this station; besides, it had the additional advantages of a fine water power. At the east end were two half-breeds employed by the company, and George Chase, a young man from Derby, Vermont, a nephew of ex-Mayor Horace, and Dr. Enoch Chase, of Milwaukee, an employee of Stuntz, who, with James Stephenson, was awaiting the return of Gen. Cutler with reinforcements, in order to continue the survey. Chase subsequently made a claim which he was successful in securing – selling it finally to the Mr. Cogswell, of Milwaukee.

It is also proper to state in addition to what has been already mentioned, that at, or about this time, a road was opened by Mr. Herbert’s order, from the Hay Marsh, six miles out from Ironton, to which point one had been previously opened, to the Range, which it struck about midway between Sidebotham’s and Lockwood’s Stations, over which, I suppose, the 50,000 tons as previously mentioned, was to find its way to Ironton, (in a horn). For this work, however, the Company refused to pay, as they had not authorized it; neither had Mr. Herbert, at that time, any authority to contract for it, except at his own risk; his appointment as agent having already been revoked; although his accounts had not, as yet, been fully settled. This work, which was without doubt, intended to commit the company still further in favor of Ironton as an outlet for the iron, was done by Samuel Champner, a then resident of Ashland and who if living is probably that much out of pocket today. No use was ever made of this road by the Company, not one of their employees, to my knowledge, ever passing over it.

This description will, I think, give your readers a very good understanding of the condition as well as the true inwardness of the affairs of the Wisconsin & Lake Superior Mining and Smelting Co., in the month of June, 1857.

At length, after remaining on the Range nearly three weeks, awaiting, Micawber like, for something to turn up, a change came with the arrival of Gen. Cutler from Milwaukee with the expected reinforcements. Mr. Herbert at once left the Range, went to Milwaukee and settled up with the Company, after which, to use a scriptural expression, “he walked no more with us.”

“A special defense in contract law to allow a person to avoid having to respect a contract that she or he signed because of certain reasons such as a mistake as to the kind of contract.”

~ Duhaime.org

Wheelock, Smith, and McClellan were at once placed upon claims – McClellan in the interest of John Cummings, (whose name by an oversight was also omitted from the list of stockholders, given in my first paper), and Wheelock and Smith for the Company generally. Subsequently, A.S. Stacy, of Canada, was also employed to hold a claim. How well he performed this duty, will be seen further on. This done, the improvements necessary to be made in order to entitle us to the benefits of the preemption law were at once commenced. These improvements consisted of log cabins, principally, of which some twenty in all were erected upon the different claims. These cabins would have been a study for Michel Angelo, or Sir Christopher Wren. They had more angles than the Forty-seventh Problem of Euclid, with an average inclination of fifteen degrees to the Ecliptic. O, but they were “fearfully and wonderfully made,” were these cabins. Their construction embodied all the principle points of architecture in the Ancient as well as Modern–Milesian-Greek, mixed with the “hoop skirt” and Heathen Chimee. Probably ten dollars a month would have been considered a high rent for any of them. No such cabins as those were in exhibition at the Centennial, no sir. Rome was not built in a day, but most of these cabins were. I built four myself near the Gorge, in a day, with the assistance of two halfbreeds, but was not able to find them a week afterwards. This is not only a mystery but a conundrum. I think some traveling showman must have stolen them; but although they were non est we could swear that we had built them, and did.

Springdale townsite plan at Sidebotham’s station by The Gorge of Tyler’s Fork in close proximity to the Ironton Trail and Iron Range. (Detail of Stuntz’s survey during August of 1857.)

Three were accordingly platted — one at Penoka, one at Lockwood‘s and one at the Gorge. And in order that it might be done without interfering with the regular survey, Gen. Cutler decided to place S.R. Marston who, in addition to his other accomplishments, claimed to be a full-fledged surveyor, in charge of the work, assisted by Wheelock, Smith and myself. He commenced at the Gorge, run three lines and quit, fully satisfied that he had greatly overestimated his abilities. We were certainly satisfied that he had. A drunken man could have reeled it off in the dark and come nearer the corner than he did. He was a complete failure in every thing he undertook. He left in the fall after the failure of the Sioux Scrip plot. Where he went I never knew. George E. Stuntz was subsequently put upon the work, which he was not long in doing, after which he rejoined Albert on the main work. This main work, however, for the completion of which we were all so anxious, was very much delayed, the cause for which we did not at the time fully understand, but we did afterwards. J.S.B.

Penokee Survey Incidents: Number II

February 12, 2015

By Amorin Mello

The Survey of the Penoka Range and Incidents Connected with its Early History

—

Number II.

Friend Fifield:– Notwithstanding the work upon the Range was delayed very much on account of the unwoodsman like conduct of the Milwaukee boys, referred to in my first communication, yet it did not cease,- the company having a few white men, previous employed, as well as a large number who were “to the Mannor born” that did not show the “white feather” on account of the mosquitos, gnats, gad flies and other vermin with which the woods were filled,– most of whom remained with us to the end.

Prominent among these last named was Joseph Houle, or “Big Joe” as he was usually called,– a giant halfbreed, (now dead), who was invaluable as a woodsman and packer. Some idea of Joe’s immense strength and power of endurance may be formed from the fact that he carried upon one occasion the entire contents, (200 lbs.) of a barrel of pork from Ironton to the Range without seeming to think it much of a feat. Among the party along on this trip was a young man taking his first lesson in woodcraft, whose animal spirits cropped out to such a degree that the leader caused to be placed upon his back a bushel of dried apples (33 lbs.), simply to keep him from climbing the trees, but before he reached the Range, his load, light as it was, proved too much for him, when Joe, in charity, relieved him of it, adding it to his own pack – making it 233 lbs. This was, without doubt the largest pack ever carried to the Range by any one man. There was an Indian, however, in the employ of the company, as a packer, (“Old Batteese“), who left Sidebotham‘s claim one morning at 7 A.M., went to Ironton and was back again to camp at 7 P.M. with 126 lbs. of pork, having traveled forty-two miles in ten hours. This was in July ’57, and was what I considered the biggest day’s work ever done for the company. The usual load, however, for a packer, was from sixty to eighty pounds.

Ironton townsite claim at Saxon Harbor with trails to Odanah and the Penoka Iron Range. (Detail from Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records)

The halfbreeds were sulky and mutinous at times, giving us some trouble, until Gen. Cutler, who was a strict disciplinarian, gave them a lesson that they did not soon forget and which occurred at follows:

The General and myself left Ironton just before the removal of our supplies to Ashland, with four of these boys, with provisions for the Range, to be delivered at Lockwood’s Station. But upon reaching Sidebotham’s, two of them refused to proceed any further, threw down their packs, and started on their return to Ironton. The General’s blood was up in a moment, and directing me to remain with the others until he returned, at once started after them. Reaching Ironton at 11 A.M., about an hour after their arrival, they were quite surprised at seeing him, but said nothing. The General at once directed Duncan Sinclair, who had charge of the supplies at that time, to make up two packs of one hundred pounds each, with ropes in place of the usual leathern strap, which was quickly done, the “rebels” looking sullenly on all the while. When all was ready he drew his revolver and ordered them to pick them up and start. They did not wait for a second order, but took them and started, he followed immediately behind. Nor did he let them lay them down again until they reached Lockwood’s at sunset, a distance of twenty-six miles. – That evening they were the most completely used up men I ever saw on the Range, and from that time forward were as submissive and obedient as could be desired. After that we never had any trouble. It was a lesson they never forgot.

Among the whites referred to in this article, was James Stephenson, a young man from Virginia, who came up with Stuntz as a surveyor. He was of light build, wiry and muscular – full of fun – very excitable and nervous, – but a good man for the woods. He had some knowledge of the compass, but not sufficient education to make a good surveyor. “Jim” got lost once and was out three days before he came into camp, which he did just as the party was starting out to find him. “Jim” would not have made a good rope walker. He was no Blondin. On the ground he was all right, but let him attempt to cross a stream of water, be it ever so small, upon a log, no matter if the log was six feet in diameter, and he would fall in sure. He fell in twice while lost and came near perishing with wet and cold in consequence of it. He left the company in the fall of ’57.

But the best man we had on the range that summer, as a surveyor, (except Albert Stuntz, and I very much doubt if he could beat him), was George E. Stuntz, a nephew of Albert’s, known among the boys as “Lazarus.” He was tall and slim, with a long thin face, blue eyes, long dark brown hair, stooped slightly when walking; walked with a swinging motion, spoke slow and loud – was fond of the woods, prided himself on his skill with the compass, and was, I think, the laziest man at that time in the county, except “Sibly,” who could discount him fifty and then beat him. But notwithstanding all this Albert could not have completed his survey that season without him. His lines never required any corrections. George was a singer – or thought he was, which is all the same. The recollections of some of his attempts in this line almost brings tears to my eyes from laughter, even now. Nearly every night in camp, the boys, after getting into a position where they could laugh without his seeing them, would coax him to sing. His favorite piece was a song called “The Frozen Limb.” What it meant I have no idea, and do not think he had. One verse of this only can I recall to mind, which ran as follows:

“One cold, frosty evening as Mary was sleeping –

Alone in her chamber, all snugly in bed. – She woke with a noise that did sorely affright her.

‘Who’s that at my window?’ she fearfully said.”

You can easily imagine how this would sound when sung through the nose in the hard shell style – each syllable ending with a jerk, something like this:

“Who’s-that-at-my-win-dow-she-fear-ful-ly-said-ud.”

George had a suit of clothes for the woods made of bed ticking, cap and all complete – all but the cap in one piece. The cap was after the “Dunce” pattern, ie, it ran to a point. The stripes instead of running up and down as they should have done, ran diagonally around him, giving him the appearance of a walking barber’s pole. He was a nice looking boy – he was.

Shortly after donning this beautiful suit, while crossing the Range, he suddenly found himself face to face with a full grown bear. It was no doubt a surprise to both parties,– it certainly was to the bear. For he took one square look and left for distant lands at a speed which, if kept up, would have carried him to Mexico in two days. “Not any of that in mine” was probably what was passing through his massive brain, but he made no sign. The boys who were surveying some fifteen miles south of the Range claimed to have met him that day, still on the jump. J.S.B.

Penokee Survey Incidents: Number I

February 8, 2015

By Amorin Mello

The Ashland Weekly Press is now the Ashland Daily Press.

November 10, 1877

For the Ashland Press

The Survey of the Penoka Iron Range and Incidents Connected With Its Early History.

—

James Smith Buck (1812-92) “For 19 years, Buck was a building contractor, erecting many of the city’s earliest structures. He is best known for his writings on early Milwaukee history. From 1876 to 1886, he published a four-volume History of Milwaukee, filled with pioneer biographies and reminiscences.” (Forest Home Cemetery)

Friend Fifield:- Being one of the patrons and readers of your valuable paper, and having within the past year noticed several very interesting and well written articles entitled “Early Recollections of Ashland” in its columns, and more particularly one from a Milwaukee correspondent, in a recent number, in which my name, with others, was mentioned as having done some pioneer work in connection with your young city, I thought that a few lines in the way of a “Reminiscence” from me as to how and by whom the Penoka Range was first surveyed and located, might be interesting to some of your readers,- if you think so, please give this a place in your paper and oblige.

Truly Yours,

J.S. Buck.

I first visited Lake Superior in the month of May, 1857, in the interest of the Wisconsin and Lake Superior Mining and Smelting Co., a charter for the organization of which had been procured the previous winter.– This company was composed of the following gentlemen: Edwin Palmer, Gen. Lysander Cutler, Horatio Hill, Jas. F. Hill, Dr. J.P. Greves, John Lockwood, John L. Harris, John Sidebotham, Franklin J. Ripley and myself. Edwin Palmer, President, J. F. Hill, Secretary – with a capital of (I think) $60,000. Our first agent was Mr. Milliam Herbert, with headquarters at Ironton, where some five thousand dollars of the company’s money was invested in the erection of a block-house and a couple of cribs intended as a nucleus for a pier – and in other ways – all of which was subsequently abandoned and lost – the place having no natural advantages, or unnatural either, for that matter.– But so it is ever with the first and often with the second installments that such greenies as we were, invest in a new country; for so little did we know of the way work was done in that country that we actually supposed the whole thing would be completed in three months and the lands in our possession. But what we lacked in wisdom, we made up in pluck — neither did we “lay down the shubble and de hoe,” until the goal was reached and the Penoka Iron Range secured – costing us over two years time and $25,000 in money.

The company not being satisfied with Mr. Herbert as agent, he was removed and Gen. Cutler appointed in his place, who quickly selected Ashland as headquarters, to which place all the personal property, consisting of merchandise principally, was removed during the summer by myself upon Gen. C.’s order – and Ironton abandoned to its fate.

~ Captain Robinson Derling Pike (Bayfield 50th anniversary celebrations)

The company at this time having become not only aware of the magnitude of the work they had undertaken, but were also satisfied that Ashland was the most feasible point from which to reach the Range, as well as the place where the future Metropolis of the Lake Superior country must surely be — notwithstanding the “and to Bayfield“ clause in that wonderful charter of H.M. Rice.

The cost of getting provisions to the Range was enormous – it being for the first season all carried by packers – every pound transported from Ashland to the Range costing from five to eight cents as freight.

This was my first experience at surveying as well as Mr. Sidebotham’s, and although I took to it easily and enjoyed it, he never could. He was no woodsman; could not travel easily, while on the other hand I could outwalk any white man except S.S. Vaughn in the country. He was then in his prime and one of the most vigorous and muscular men I ever met; but I think he will tell you that in me he found his match.

By our contract with Albert Stuntz we were not only to pay him a bonus equal to what he received per mile from Government, but we were also to furnish men for the work and see him through. In accordance with this agreement some eighteen men and boys, to be used as axemen and chainmen, were brought up from Milwaukee who were as “green as gaugers” and as the sequel proved, about as honest. A nice looking lot they were, when landed upon the dock at La Pointe, out of which to make woodsmen. I think I see them now, shining boots,– plug hats, with plug ugly heads in them, (at least some of them had), the notorious Frank Gale, Mat. Ward and one or two other noted characters being of the number. Their pranks astonished the good people of La Pointe not a little, but they astonished Stuntz more. One half day in the woods satisfied them – they were afraid of getting lost. In less than two weeks they had nearly all deserted and the work had to be delayed until a new squad could be obtained from below.

But I must close. In my next I will give you an account of my life on the Range. J.S.B.

!["In 1845 [Warren Lewis] was appointed Register of the United States Land Office at Dubuque. In 1853 he was appointed by President Pierce Surveyor-General for Iowa, Wisconsin and Minnesota and at the expiration of his term was reappointed by President Buchanan." ~ The Iowa Legislature](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/warner-lewis.jpg?w=196&h=300)

![Leonard Hemenway Wheeler ~ Unnamed Wisconsin by [????]](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/leonard-hemenway-wheeler-from-unnamed-wisconsin.jpg?w=237&h=300)