Edwin Ellis Incidents: Number VI

April 13, 2022

By Amorin Mello

Originally published in the August 11th, 1877, issue of The Ashland Press. Transcribed with permission from Ashland Narratives by K. Wallin and published in 2013 by Straddle Creek Co.

… continued from Number V.

EARLY RECOLLECTIONS OF ASHLAND

“OF WHICH I WAS A PART.”

Number VI

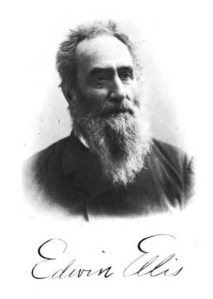

Edwin Ellis, M.D.

photograph from Magazine of Western History: Volume IX, No.1, page 20.

My Dear Press: – The history of the first attempt at dock building was told in a former chapter, and also the sudden disappearance of the dock one night in April, 1855.

The early settlers did not, upon their first arrival here, have any fair appreciation of the difficulties in the way of constructing docks, which should be able to resist the several forces to which they would be exposed, and which would certainly tend to their overthrow. They had not had, as this generation has, the advantage of years of observation of the force of ice as affected by winds, as floating in great fields and driven by wind and tide, nor of the great force arising from expansion. We now understand better what is the strength of these destructive forces. Some of us watched them with intense and eager anxiety for years; for no commercial town could be here built up without docks.

It may not be uninteresting to consider in a few words, the varying modes in which the heavy accumulation of ice, during our long winters, is got rid of in the spring, and navigation opened.

Some seasons the water in the bay seems to stand at the same level, not moving by winds or tides for many days in succession. The ice melts away under the rays of the sun and by the warmth of the south wind. It is a slow but gentle process. Any dock is safe in such a season. At other times there are sudden and great changes in the elevation of the surface of the ice or water, either from the force of wind on the open water in the outside lake, or from barometric pressure, or both combined, a great influx of water is driven under the ice into the bay. At that juncture the ice having been melted away near the shore all around the bay, the whole mass is lifted up several inches and held us on the top of a great wave. But the reflux of the water must soon occur – when this great field of ice moves down upon a heavy grade. Its speed will often be accelerated by a strong southwest wind. The force thus generated is well-nigh irresistible unless there be such a conformation of the shore as shall save the dock from its full effect, and such, fortunately, is the case with our shore.

Another force, also operating with great power and effect upon the first docks built here and from which they suffered severely, was the expansive power of ice, resulting from changes of temperature. The water in early winter freezes with level surface and is fast to both shores. But as the cold becomes more intense and the ice thickens, it also sensibly expands, and crowds with great power upon the shore. It is easy to perceive that docks fully exposed to this force would need to be very firmly bolted together, and covered with heavy loads, or they must be pushed over. Our docks were thus in the more exposed cribs, broken, and afterwards easily carried away by floating ice and waves. Our first docks having been carried away; though somewhat alarmed, we did not at once give up.

Martin Beaser

portrait from Magazine of Western History: Volume IX, No.1, page 24.

In December 1855, two docks were commenced, one called the Bay City Dock, near the sash factory – and the other at the foot of Main Street in Beaser’s Division of Ashland, in front of the present residence of James A. Wilson. This last was built by Mr. Beaser. His plan was to build cribs with flattened timber, fitted closely together so as to hold the clay with which they were filled as ballast, instead of rock, for rock could only be obtained at great cost. We had no steam tugs then, with which to tow scows, as at present. The cribs were carried out some five or six hundred feet and filled with clay. Stringers connected the cribs, over which poles were laid as a roadway.

The Bay City Dock was also built out into deep water with an L running east. The cribs near the shore were filled with rocks, but for want of time the outer cribs and the L were not filled before the spring break up. The cribs were, however, constructed with stringers and covered, and some two hundred cords of cord wood were piled upon the dock to prevent the moving of the cribs.

The ice in the bay had not moved, but was melted away and broken up for a few hundred feet from the shore. There was a great influx of water from the Lake, raising the whole body of the ice. In a short time there was a greater reflux of the water, and the vast field of ice was seen to be in motion. All eyes were watching the docks, nor was it needed to watch long. Mr. Beaser’s was the first to give way. The cribs did not seem to offer any resistance to the moving mass. The most of them were carried away in less time than it takes to describe it. Only a few cribs near the shore escaped.

Nor was the attack on Bay City Dock long delayed; steadily onward came the mass. And the outer portion was soon in ruins, and the great pile of wood was floating upon the water. The cribs forming the approach for about three hundred feet, being filled with rock were not carried away. Thus in one hour were swept away the labors of many months, and several thousand dollars. The sight was discouraging to men who had come here to make their homes, and whose all was involved in the ruins. The elements seemed in league against us. The next day the steamer Superior arrived and effected a landing upon the broken timbers of our dock. Capt. Jones was in command of her, who, together with his boat were soon to go down in death beneath the waters of the Great Lake.

1860 photograph of the steamer Lady Elgin from the Chicago History Museum and digitized by Ship-Wrecks.net

During the summer and fall of 1856 the Bay City Dock was repaired and extended further into the bay, and the cribs filled with rocks, and the steamer Lady Elgin made several landings alongside. But during the winter of 1856 and ’57 the expansive power of the ice, showing against the cribs pushed off the timbers at the water line of several of the outer cribs, which, at the opening of navigation in 1857, were carried away, leaving only sunken cribs. The dock was never rebuilt, as the financial storm of 1857 began already to lower upon us. The sunken cribs still remain, as has been proved by the exploration of Capts. Patrick and Davidson, in command of the tugs Eva Wadsworth and Agate.

The experience of the “new Ashland” have demonstrated that pile docks can be built so as successfully to resist all the opposing forces to which they are exposed. The result of all our experience seems to show that the best dock which can be built is the pile dock filled in between piles with logs or slabs, or what would be better to drive piles close together, capping them and filling in with rocks which will, beyond doubt, be done so soon as our Penoka iron mountains shall be worked. The time when, must depend upon an improved demand for iron.

To be continued in Number VII…

After Missing Treasure

April 10, 2019

By Amorin Mello

The New York Times

June 15, 1897

AFTER MISSING TREASURE

—

James Arthur Looking for $35,000 Buried in Wisconsin at the Outbreak of the War.

—

GOLD HIDDEN IN THE GROUND

—

Net Assets of a Wisconsin Bank Closed When Arthur Enlisted in the Army – Put Away by His Partner, Ell Pingers.

—

SUPERIOR, Wis., June 14. – James Arthur, a veteran of the civil war, now a resident of Buffalo, N. Y., arrived in Superior a few days ago to make inquiries concerning a transaction dating back nearly forty years, and to complete arrangements for starting on a mission in quest of a treasure supposed to be sunk in the bowels of the earth at a point not far from the town of La Pointe, in Ashland County, Wis.

La Pointe Beaver Dollar

Northern Outfit, American Fur Company

~ Wisconsin Academy of Science, Arts, & Letters, Volume 54, page 159.

According to Mr. Arthur’s story, a bag containing $35,000 in gold was buried in the ground by Ell Pingers in 1861, and has never been discovered, though several expeditions have gone in search of it. It is a strange story, but it is not fiction, unless several old timers with records for veracity have combined to deceive the world, and unless State records lie and other documents fail to prove genuine. The money was certainly placed in a hole in the ground by Ell Pingers in the year 1861, and it probably was never taken away, for the man who did the planting was killed during the war, and no other person knew where the hiding place was. A paper has come to light recently which furnishes a clue to the location of the treasure, and Mr. Arthur expects to be richer by $35,000 within a fortnight.

Superior Chronicle – November 4, 1856

“INDIAN PAYMENT. – Mr. Jos. Gurnoe, last week, distributed among the Chippewa Indians of this vicinity their annuities. An unlimited number of silver half dollars are now in circulation, and all are enjoying the benefits of Uncle Sam’s liberality.”

In the year 1856, when wildcat money flooded the State of Wisconsin, and when the country was on the verge of a financial and political crisis, James Arthur and Ell Pingers, two young men who had been supplied by their respective fathers with a good start in life, immigrated from New York to La Pointe and established a bank, which not only issued notes of its own, but made a specialty of discounting the issue of other banks throughout the State. They pulled through the panic of 1857, and the bank was counted among those that redeemed its currency at face value. When war became imminent between the North and South the young men decided to close out their banking business and return to the East to engage in something more lucrative. In 1861, however, before the bank closed, James Arthur made a trip to Milwaukee, and there became fired with a desire to serve his country as a soldier. He sent a letter to Pingers at La Pointe asking him to close out the business as soon as possible and leave for the East with all the funds. He also gave Pinger the number of his regiment and full directions as to where letters should be sent. Then he marched to the front with a Wisconsin regiment.

Facsimile of a $50 coin found at La Pointe.

~ Joel Allen Barber Papers, Summer of 1858

Six months after joining the army Arthur received his first and only communication from Pingers. It was a short note, dated from Milwaukee three months prior, and had been forwarded from post to post until it finally reached him at St. Louis. This note is now in the possession of Mr. Arthur, and was shown by him on his arrival here several days ago. It reads as follows:

“Milwaukee, June 8, ’61 – 4 P.M.

“Friend Jim: Got your letter all right. Have closed up bank and sold everything for cash. I realized in all $37,000, and take $2,000 of that with me, but not caring to take a large sum through such a wild country I buried it in a safe place and will advise later concerning exact spot. I am off for bloody war myself. Yours,

“ELL PINGERS.”

Julius Austrian operated a bank at La Pointe circa 1855.

In 1863 Arthur went on a furlough to visit his mother and sisters in New York City, and while there learned that Pingers had been killed at the battle of Richmond, Ky., on Aug. 30, 1862. The papers and numerous personal effects of the dead soldier had been shipped to his mother from Milwaukee previous to his enlistment in the army, but a thorough search failed to disclose any information concerning the location of the hidden treasure. So the furloughed soldier returned to the scenes of war without hope of ever being able to recover the snug little fortune stored away somewhere in Wisconsin soil.

The war over Mr. Arthur returned to New York, and in 1866 he made a trip to La Pointe in company with two friends for the purpose of hunting up the hidden gold. The mission was a fruitless one, but it had the effect of exciting the La Pointe community, and for years after that the natives dug holes in all directions from the old bank, but as far as known the treasure was never unearthed.

In 1867 Arthur’s mother died, leaving him a small fortune, and the following year he married the sister of the dead soldier, Ell Pingers. Through this marriage all the personal effects of Pingers came into Arthur’s possession, and he made many searches through the papers for a clue to the whereabouts of the missing $35,000, but without result. Ten years after his marriage he made another trip to the scene of his old banking operations, and five years after that he sent a trustworthy employee to look for the hidden gold, but no gold was to be found, and finally all hope of ever recovering the treasure was abandoned.

Hermit Island is believed by some to contain several other long-lost treasures:

– 1861 Wilson the Hermit

– 1760’s British Military Payroll

– Stereotypical Pirate Stories

Did Pingers bury their treasure here as well?

About three weeks ago, while turning the pages of an old book which had once been the property of Ell Pingers, a small piece of note paper was found by Mrs. Arthur which contained a memorandum written by the dead soldier and which gave the missing information for which search had been made for years. This note, Mr. Arthur claims, will no doubt lead to the discovery of the treasure in time, but the references it makes to roads, trees, and other landmarks have long since been removed by the hand of progress or obliterated by time, and the undertaking will therefore be attended by more or less of the difficulties before experienced. The old gentleman is confident that, with the information obtained from old acquaintances here and the assistance expected from old residenters at La Pointe, he will be able to unearth the long-buried treasure. He declares his intention of donating one-half of the $35,000 to the veteran soldiers of the Union Army and turning the remainder over to his wife to do as she pleases with.