Bayfield’s Beginnings

March 6, 2016

By Amorin Mello

This is a reproduction of Captain Robinson Darling Pike’s speech for the 50th anniversary celebrations of Bayfield, Wisconsin on March 24th, 1906. It was originally digitized and reproduced onto RootsWeb.com by John Griener, a great-grandson of Currie G. Bell. The Bayfield County Press was in the Bell family from the Fall of 1882 until July of 1927. Pike’s obituary was not included in this reproduction.

Portrait of Bayfield from History of Northern Wisconsin, by the Western Historical Company, 1881, page 80.

Capt. R. D. PIKE on

Bayfield’s Beginnings

Captain Robinson Derling Pike

~ A gift that spawns Great Lakes fisheries:The legacy of Bayfield pioneer R.D. Pike, by Julia Riley, Darren Miller and Karl Scheidegger for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, October 2011.

Robinson Darling PIKE, son of Judge Elisha and Elizabeth Kimmey PIKE, was a lumbering giant in early Bayfield history. Capt. R. D. Pike, as his name appeared weekly in the Press, was one of the most influential men in the county, associated not only with timber interests, but with the Bayfield Brownstone Company, the electric light company, the fish hatchery, etc. Just before his death on March 27, 1906, he wrote the following recollections of early Bayfield. The paper was read at the Bayfield 50th anniversary celebrations and was published in the March 30, 1906 issue of the Press along with Capt. PIKE’s obituary:

I regret very much not being able to be with you at the celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the town of Bayfield. As you may be aware, I have been ill for the past few weeks, but am pleased to state at this time I am on the gain and hope to be among you soon. If my health permitted I would take great pleasure in being present with you this evening.

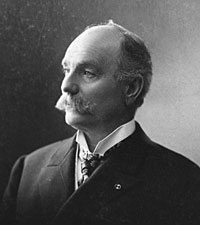

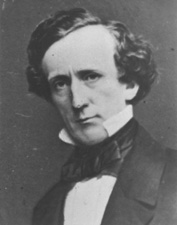

Senator Henry Mower Rice

~ United States Senate Historical Office

I remember very distinctly that the first stake was driven in the town of Bayfield by Major McABOY who was employed by the Bayfield Townsite Company to make a survey and plat same, (the original plat being recorded at our county seat.) This Bayfield Townsite Company was organized with Hon. Henry M. RICE of St. Paul at the head and some very enterprising men from Washington D.C. Major McABOY arrived here about the first of March and made his headquarters with Julius AUSTRIAN of LaPointe. Julius AUSTRIAN in those days being the Governor General of all that part of the country west of Ontonagon to Superior; Ashland and Duluth being too small to count The major spent probably two weeks at LaPointe going back and forth to Bayfield with a team of large bay horses owned by Julius AUSTRIAN, being the only team of horses in the country.

For more information about Julius Austrian, see other Austrian Papers.

I remember very well being in his office at LaPointe with father, (I being then a mere lad of seventeen,) and I recollect hearing them discuss with Mr. AUSTRIAN the question of running the streets in Bayfield north and south and avenues east and west, or whether they should run them diagonally due to the topography of the country, but he decided on the plan as the town is now laid out. Mr. AUSTRIAN and quite a little party from LaPointe came over here on the 24th of March, 1856, when they officially laid out the town, driving the first stake and deciding on the name Bayfield, named after Lieutenant Bayfield of the Royal Navy who was a particular friend of Senator RICE, and it was he who made the first chart for the guidance of boats on Lake Superior.

“Map of Bayfield situate in La Pointe County, Wisconsin” by Major William McAboy, 1856 for the Bayfield Land Company.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

For more information about Indian interpreter Frederick Prentice, see his appearances in the Barber Papers.

~ Portrait of Prentice from History of the Maumee Valley by Horace S Knapp, 1872, pages 560-562.

The summer of 1855 father was in poor health, filled up with malaria from the swamps of Toledo, and he was advised by Mr. Frederick PRENTICE, now of New York, and known by everybody here as “the brownstone man,” to come up here and spend the summer as it was a great health resort, so father arrived at LaPointe in June, 1855, on a little steamer that ran from the Soo to the head of the lakes, the canal at that time not being open, but it was opened a little later in the season.

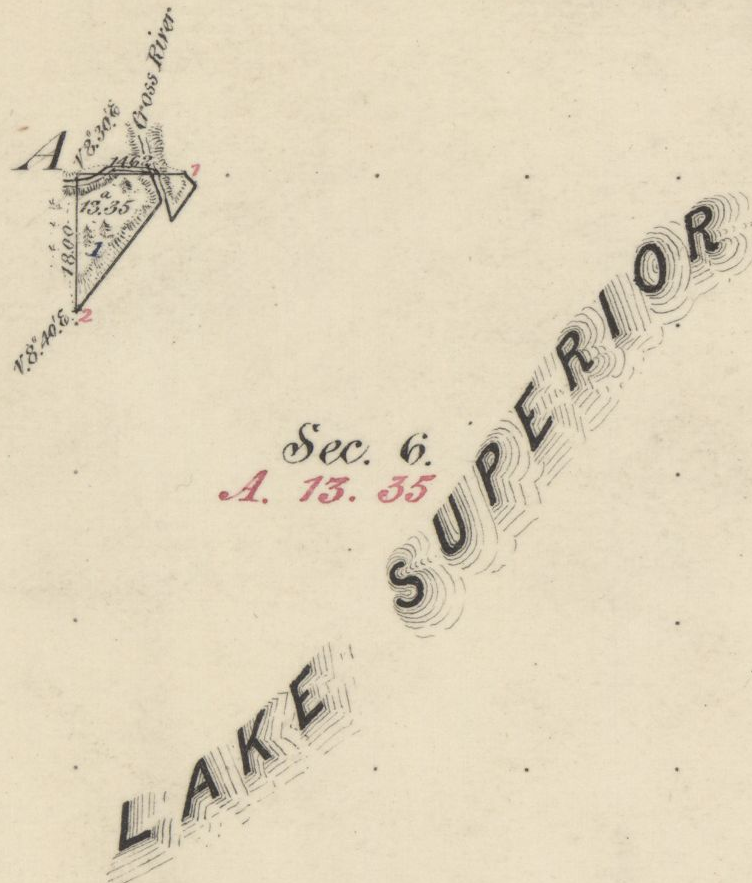

Detail of “Austrian’s Saw Mill” on Pike’s Creek, Chequamegon Bay, Lake Superior, circa 1852.

~ Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records

Upon arrival at LaPointe father entered into an agreement with Julius AUSTRIAN to come over to Pike’s creek and repair the little water mill that was built by the North American Fur Company, which at that time was owned by Julius AUSTRIAN. He made the necessary repairs on the little mill, caught plenty of brook trout and fell in love with the country on account of the good water and pure air and wrote home to us at Toledo glowing letters as to this section of the country. Finally he bought the mill and I think the price paid was $350 for the mill and forty acres of land, and that largely on time; however the mill was not a very extensive affair. Nearly everything was made of wood, except the saw and crank-pin, but it cut about two thousand feet of lumber in twelve hours. Some of the old shafting and pulleys can be seen in the debris at the old mill site now. Remember these were not iron shafts as we used wooden shafts and pulleys in those days. This class of the mill at the time beat whip-sawing, that being the usual way of sawing lumber.

Father left LaPointe some time in September 1855 for Toledo to move his family to Pike’s creek, which stream was named after we moved up here. Onion river and Sioux river were named before that time. On father’s arrival from Toledo from this country we immediately began to get ready to move. We had a large fine yoke of red oxen and logging trucks. He sold out our farm at Toledo, packed up our effects, and boarded a small steamer which took us to Detroit. Our family then consisted of father, mother, grandma PIKE, and my sister, now Mrs. BICKSLER, of Ashland. We stayed several days in Detroit to give father time to buy supplies for the winter; that is feed for the oxen and cow and groceries for the family to carry us through until Spring.

We then boarded the steamer Planet, which was a new boat operated by the Ward Line, considered the fastest on the lake. It was about two hundred fifty tons capacity. We came to Sault Ste. Marie, it being the Planet‘s first trip through the Soo, the canal as I remember was completed that fall. During this year the Lady Elgin was running from Chicago and the Planet and North Star running from Detroit, they being about the only boats which were classed better than sail boats of the one hundred and fifty tons.

Portrait of the Steamer North Star from American Steam Vessels, by Samuel Ward Stanton, page 40.

~ Wikimedia.org

We arrived at LaPointe the early part of October, 1855. On our way up we stopped at Marquette, Eagle Harbor, Eagle River, and Ontonagon. We left Ontonagon in the evening expecting to arrive at LaPointe early the next morning, but a fearful storm arose and the machinery of the Planet became disabled off Porcupine mountains and it looked for a while as though we were never going to weather the storm, but arrived at LaPointe the next day. There were some parties aboard for Superior who left LaPointe by sail.

We remained at LaPointe for a week or ten days on account of my mother’s health and then went to Pike’s bay with all our supplies, oxen and cow on what was known as the Uncle Robert MORRIN’s bateau. Uncle Robert and William MORRIN now of Bayfield, and if I remember rightly, each of the boys pulled an oar taking us across. We landed in Pike’s bay just before sundown, hitched up the oxen and drove to the old mill. Now, this was all in the fall of 1855.

Detail from William McAboy‘s 1856 Map of Bayfield.

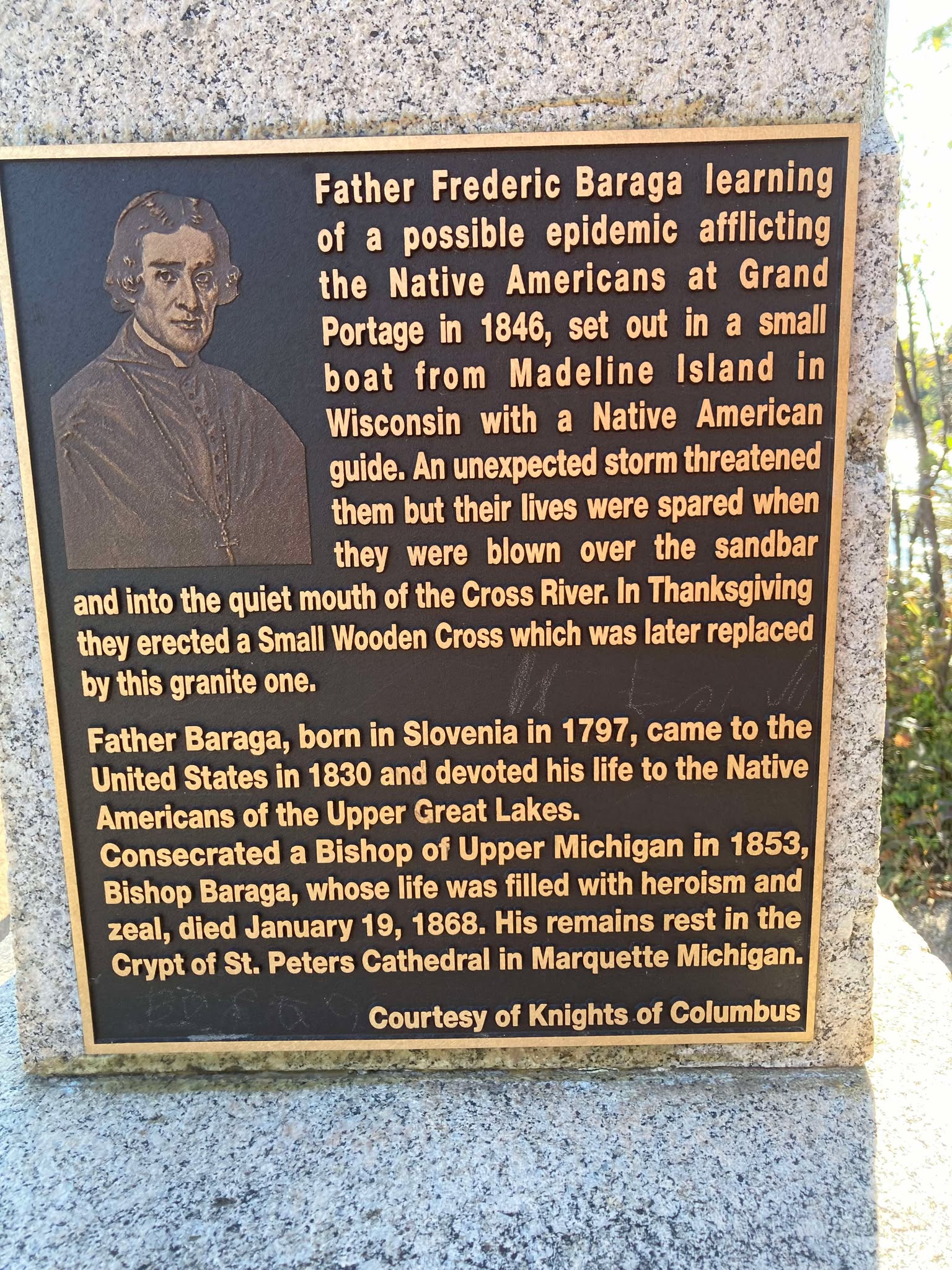

“HON. JOHN W. BELL, retired, Madeline Island, P.O. La Pointe, was born in New York City, May 3, 1805, where he remained till he was eight years of age. His parents then took him to Canada, where his father died. He had gotten his education from his father and served an apprenticeship at three trades – watchingmaking, shipbuilding, and coopering. He then moved to Ft. La Prairie, and started a cooper shop, where he remained till 1835, when he came to La Pointe, on the brig “Astor,” in the employ of the American Furn Company as cooper, for whom he worked six months, when he took the business into his own hands, and continued to make barrels as late as 1870. It was in 1846 or 1847 that Robert Stewart, then Commissioner, granted him a license, and he opened a trading post at Island River, and became interested in the mines. he explored and struck a lead in the Porcupine Range, on Onion River, which he sold to the Boston Company, and then came back to La Pointe. In 1854 he was at the treaty between the Chippewas of Lake Superior and the Mississippi River, and was appointed Enrolling Agent on their new reservation, on the St. Louis River, where he went, but soon came back, as the Indians were not willing to stay there. He was then appointed by the Indians to look up their arrearages, and while at this work visited the national capital. He was appointed to County Judge for La Pointe County, and helt till 1878. He was elected on the town board in 1880. Has been Register of Deeds a great many years. Has held most all the different county and town offices, and at one time held or did principally the business for the whole county. He has seen La Pointe in all of its glory dwindle down to a little fishing hamlet; is now Postmaster at his island home, where he occupies a house put up by the old fur company. He was married in 1837 to Miss Margaret Brebant, in the old Catholic Church, by Rev. Bishop Baraga. They had seven children – John(deceased), Harriette (now Mrs. La Pointe), Thomas (deceased), Alfred (now Town Clerk), Sarah F., Margaret (deceased), and Mary (now Mrs. Denome).”

~ History of Northern Wisconsin, by the Western Historical Company, 1881.

As I said before, the town was laid out on March 24th, 1856, and record made same at LaPointe by John W. BELL, who at that time was the “Witte” of all the country between Ontonagon and Superior; Julius AUSTRIAN being the “Czar” of those days and both God’s noblemen. [Note: This was a reference to Count Sergei Witte and Tsar Nicholas II, contemporaries of Capt. Pike. Witte was responsible for much industrial development of Tsarist Russia in the 1890’s.] The Territory now comprising the town of Bayfield was taken from LaPointe county. There were a number of very prominent men interested in laying out the townsite and naming our avenues and streets, such as Hon. H. M. RICE and men of means from Washington after whom some of our avenues were named.

Very soon after this they wished to build a large mill in order to furnish lumber necessary for building up the town. The Washington people decided upon a man by the name of CAHO, an old lumberman of Virginia, so he was employed to come up here and direct the building of the mill. A hotel was built directly across from the courthouse by the Mr. BICKSLER who afterwards married my sister. The saw mill was built about a block west of where my saw mill now stands. The mill had a capacity of five or six thousand feet per day and I think the machinery came from Alexandria, Virginia. Joe LaPOINTE was the only man recognized as being capable of running a mill from the fact that he could do his own filing and sawing. While they were constructing the mill they had a gang of men in the woods getting out hard wood for fuel, not thinking of using any of the sawdust, and they piled the sawdust out with the slabs as useless. Charley DAY, whom many of you will remember, who was the party who got out the hardwood as fuel for the mill.

Time has wrought many changes in our midst. As far as I know, I am the only white man living who was here at the time the town was laid out.

In conclusion I wish to say that at a banquet given in Bayfield some two or three years ago, I made the statement that when the last pine tree was cut from the peninsula on which Bayfield is located the prosperity of our town and vicinity will have just commenced. The pine has gone and now we are cutting the hemlock and hardwood which will last ten to fifteen years; and long before this is exhausted the cut over lands will be taken up and farms tilled, as is the history of other sections of the country.

“Elisha and R.D. Pike owned a private fish hatchery [at Julius Austrian’s former sawmill] in Bayfield County from the 1860s to 1895. The Wisconsin State Legislature mandated the construction of a fish hatchery in northern Wisconsin in 1895, so R.D. Pike donated 405 acres (1.64 km2) from his hatchery to serve as the state hatchery. The state built the main hatchery building in 1897 using brownstone from nearby Pike’s Quarry. The Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis and Omaha Railway built a siding to the hatchery, and a special railcar known as The Badger brought fish from the hatchery to Wisconsin waterbodies. In 1974, new buildings and wells were constructed to modernize the hatchery. The hatchery was renamed in honor of longtime Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources secretary Les Voigt in 2006, and the main building was named for R.D. Pike in 2011. The hatchery currently spawns five types of trout and salmon and also includes a visitor’s center and aquarium.”

~ Wikipedia.org

CAUTION: This translation was made using Google Translate by someone who neither speaks nor reads German. It should not be considered accurate by scholarly standards.

Americans love travelogues. From de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, to Twain’s Roughing It, to Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley, a few pages of a well-written travelogue by a random interloper can often help a reader picture a distant society more clearly than volumes of documents produced by actual members of the community. And while travel writers often misinterpret what they see, their works remain popular long into the future. When you think about it, this isn’t surprising. The genre is built on helping unfamiliar readers interpret a place that is different, whether by space or time, from the one they inhabit. The travel writer explains everything in a nice summary and doesn’t assume the reader knows the subject.

You can imagine, then, my excitement when I accidentally stumbled upon a largely-unknown and untranslated travelogue from 1852 that devotes several pages to to the greater Chequamegon region.

I was playing around on Google Books looking for variants of Chief Buffalo’s name from sources in the 1850s. Those of you who read regularly know that the 1850s were a decade of massive change in this area, and the subject of many of my posts. I was surprised to see one of the results come back in German. The passage clearly included the words Old Buffalo, Pezhickee, La Pointe, and Chippewa, but otherwise, nothing. I don’t speak any German, and I couldn’t decipher all the letters of the old German font.

Karl (Carl) Ritter von Scherzer (1821-1903) (Wikimedia Images)

The book was Reisen in Nordamerika in den Jahren 1852 und 1853 (Travels in North America in the years 1852 and 1853) by the Austrian travel writers Dr. Moritz Wagner and Dr. Carl Scherzer. These two men traveled throughout the world in the mid 19th-century and became well-known figures in Europe as writers, government officials, and scientists. In America, however, Reisen in Nordamerika never caught on. It rests in a handful of libraries, but as far as I can find, it has never been translated into English.

Chapter 21, From Ontonagon to the Mouth of the Bois-brule River, was the chapter I was most interested in. Over the course of a couple of weeks, I plugged paragraphs into Google Translate, about 50 pages worth.

Here is the result (with the caveat that it was e-translated, and I don’t actually know German). Normally I clog up my posts with analysis, but I prefer to let this one stand on its own. Enjoy:

XXI

From Ontonagon to the mouth of the Bois-brule River–Canoe ride to Magdalen Island–Porcupine Mountains–Camping in the open air–A dangerous canoe landing at night–A hospitable Jewish family–The island of La Pointe–The American Fur Company–The voyageurs or courriers de bois–Old Buffalo, the 90 year-old Chippewa chief–A schoolhouse and an examination–The Austrian Franciscan monk–Sunday mass and reflections on the Catholic missions–Continuing the journey by sail–Nous sommes degrades–A canoeman and apostle of temperance–Fond du lac–Sauvons-nous!

On September 15th, we were under a cloudless sky with the thermometer showing 37°F. In a birch canoe, we set out for Magdalene Island (La Pointe). Our intention was to drive up the great Lake Superior to its western end, then up the St. Louis and Savannah Rivers, to Sandy Lake on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. Our crew consisted of a young Frenchman of noble birth and education and a captain of the U.S. Navy. Four French Canadians were the leaders of the canoes. Their trustworthy, cheerful, sprightly, and fearless natures carried us so bravely against the thundering waves, that they probably could have even rowed us across the river Styx.

Upon embarkation, an argument broke out between passengers and crew over the issue of overloading the boat. It was only conditioned to hold our many pieces of baggage and the provisions to be acquired along the way. However, our mercenary pilot produced several bags and packages, for which he could be well paid, by carrying them Madeline Island as freight.

Shortly after our exit, the weather hit us and a strong north wind obliged us to pull to shore and make Irish camp, after we had only covered four English miles to the Attacas (Cranberry) Rive,r one of the numerous mountain streams that pour into Lake Superior. We brought enough food from Ontonagon to provide for us for approximately 14 days of travel. The settlers of La Pointe, which is the last point on the lake where whites live, provided for themselves only scanty provisions. A heavy bag of ship’s biscuit was at the end of one canoe, and a second sack contained tea, sugar, flour, and some rice. A small basket contained our cooking and dining utensils.

The captain believed that all these supplies would be unecessary because the bush and fishing would provide us with the richest delicacies. But already in the next lunch hour, when we caught sight of no wild fowl, he said that we must prepare the rice. It was delicious with sugar. Dry wood was collected and a merry flickering fire prepared. An iron kettle hung from birch branches crossed akimbo, and the water soon boiled and evaporated. The sea air was fresh, and the sun shone brightly. The noise of the oncoming waves sounded like martial music to the unfinished ear, so we longed for the peaceful quiet lake. The shore was flat and sandy, but the main attraction of the scenery was in the gigantic forest trees and the richness of their leafy ornaments.

At a quarter to 3 o’clock, we left the bivouac as there was no more wind, and by 3 o’clock, with our camp still visible, the water became weaker and weaker and soon showed tree and cloud upon its smooth surface. We passed the Porcupine Mountains, a mountain range made of trapp geological formation. We observed that some years ago, a large number of inexperienced speculators sunk shafts and made a great number of investments in anticipation of a rich copper discovery. Now everything is destroyed and deserted and only the green arbor vitae remain on the steep trap rocks.

Our night was pretty and serene, so we went uninterrupted until 1 o’clock in the morning. Our experienced boatmen did not trust the deceptive smoothness of the lake, however, and they uttered repeated fears that storms would interrupt our trip. It happens quite often that people who travel in late autumn for pleasure or necessity from Ontonagon to Magdalene Island, 70 miles away, are by sea storms prevented from travelling that geographically-small route for as many as 6 or 8 days.

Used to the life of the Indians in the primeval forests, for whom even in places of civilization prefer the green carpet under the open sky to the soft rug and closed room, the elements could not dampen the emotion of the paddlers of the canoe or force out the pleasure of the chase.* But for Europeans, all sense of romantic adventure is gone when in such a forest for days without protection from the heavy rain and without shelter from the cold eeriness for his shivering limbs.

(*We were accompanied on our trip throughout the lakes of western Canada by half-Indians who had paternal European blood in their veins. Yet so often, a situation would allow us to spend a night inside rather than outdoors, but they always asked us to choose to Irish camp outside with the Indians, who lived at the various places. Although one spoke excellent English, and they were both drawn more to the great American race, they thought, felt, and spoke—Indian!)

It is amazing the carelessness with which the camp is set near the sparks of the crackling fire. An overwhelming calm is needed to prevent frequent accidents, or even loss of human life, from falling on the brands. As we were getting ready to continue our journey early in the morning, we found the front part of our tent riddled with a myriad of flickering sparks.

16 September (50° Fahrenheit)*) Black River, seven miles past Presque Isle. Gradually the shore area becomes rolling hills around Black River Mountain, which is about 100 feet in height. Frequently, immense masses of rock protrude along the banks and make a sudden landing impossible. This difficulty to reach shore, which can stretch for several miles long, is why a competent captain will only risk a daring canoe crossing on a fairly calm lake.

(*We checked the thermometer regularly every morning at 7 o’clock, and when travel conditions allowed it, at noon and evening.)

At Little Girl’s Point, a name linked to a romantic legend, we prepared lunch from the unfinished bread from the day before. We had rice, tea, and the remains of the bread we brought from a bakery in Ontonagon from our first days.

In the afternoon, we met at a distance a canoe with two Indians and a traveler going in an easterly direction. We got close enough to ask some short questions in telegraph style. We asked, “Where do you go? How is the water in the St. Louis and Savannah River?”

We were answered in the same brevity that they were from Crow Wing going to Ontonagon, and that the rivers were almost dried from a month-long lack of rain.

The last information was of utmost importance to us for it changed, all of a sudden, the fibers of our entire itinerary. With the state of the rivers, we would have to do most of the 300-mile long route on foot which neither the advanced season of the year, nor the sandy steppes invited. If we had been able to extend our trip, we could have visited Itasca Lake, the cradle of the Mississippi, where only a few historically-impressive researchers and travelers have passed near: Pike, Cass, Schoolcraft, Nicollet, and to our knowledge, no Austrian.

However, this was impossible considering our lack of necessary academic preparation and in consideration of the economy of our travel plan. We do not like the error, we would almost say vice, of so many travelers who rush in hasty discontent, supported by modern transport, through wonderful parts of creation without gaining any knowledge of the land’s physical history and the fate of its inhabitants.*

(*We were told here recently of such a German tourist who traveled through Mexico in only a fortnight– i.e. 6 days from Veracruz to the capital and 6 days back with only two days in the capital!)

While driving, the boatmen sang alternately. They were, for the most part, frivolous love songs and not of the least philological or ethnographic interest.

After 2 o’clock, we passed the rocks of the Montreal River. They run for about six miles with a long drag reaching up to an altitude of 100 feet. There are layers of shale and red sandstone, all of which run east to west. By weathering, they have obtained such a dyed-painting appearance, that you can see in their marbled colors something resembling a washed-out image.

The Montreal* is a major tributary of Lake Superior. About 300 steps up from where it empties into the lake, it forms a very pretty waterfall surrounded by an impressive pool. Rugged cliffs form the 80’ falls over a vertical sandstone layer and form a lovely valley. The width of the Montreal is 10’, and it also forms the border between the states of Michigan and Wisconsin.

(*Indian: Ka-wa’-si-gi-nong sepi, the white flowing falls.)

We stayed in this cute little bay for over an hour as our frail canoes had begun to take on a questionable amount of water as the result of some wicked stone wounds.

Up from Montreal River heading towards La Pointe, the earlier red sandstone formation starts again, and the rich shaded hills and rugged cliffs disappear suddenly. Around 6 o’clock, we rested for half an hour at the mouth of the Bad River of Lake Superior. We quickly prepared our evening snack as the possibility of reaching Magdalene Island that same night was still in contention.

Across from us, on the western shore of Bad River*, we saw Indians by a warm fire. One of the boatmen suspected they’d come back from catching fish, and he called in a loud voice across the river asking if they wanted to come over and sell us some. We took their response, and soon shy Indian women (squaws) appeared. Lacking a male, they dreaded to get involved in trading with Whites, and did not like the return we offered.

(*On Bad River, a Methodist Mission was founded in 1841. It consists of the missionary, his wife, and a female teacher. Their sphere of influence is limited to dispensing divine teaching only to those wandering tribes of Chippewa Indians that come here every year during the season of fishing, to divest the birch tree of its bark, and to build it into a shelter).

A part of our nightly trip was spent fantastically in blissful contemplation of the wonders above us and next to us. Night sent the cool fragrance of the forest to our lonely rocking boat, and the sky was studded with stars that sparkled through the green branches of the woods. Soon, luminous insects appeared on the tops of the trees in equally brilliant bouquets.

At 11 o’clock at night, we saw a magnificent aurora borealis, which left such a bright scent upon the dark blue sky. However, the theater soon changed scene, and a fierce south wind moved in incredibly fast. What had just been a quietly slumbering lake, as if inhabited by underwater ghosts, struck the alarm and suddenly tumultuous waves approached the boat. With the faster waves wanting to forestall the slower, a raging tumult arose resembling the dirt thrown up by great wagon wheels.

We were directly in the middle of that powerful watery surface, about one and one half miles from the mainland and from the nearest south bank of the island. It would have been of no advantage to reverse course as it required no more time to reach the island as to go back. At the outbreak of this dangerous storm, our boatmen were still determined to reach La Pointe.

But when several times the beating waves began to fill our boat from all sides with water, the situation became much more serious. As if to increase our misery, at almost the same moment a darkness concealed the sky and gloomy clouds veiled the stars and northern lights, and with them went our cheerful countenance.

Now singing, our boatmen spoke with anxious gestures and an unintelligible patois to our fellow traveler. The captain said jokingly, that they took counsel to see who should be thrown in the water first should the danger increase. We replied in a like manner that it was never our desire to be first and that we felt the captain should keep that honor. Fortunately, all our concern soon ended as we landed at La Pointe (Chegoimegon).

To be continued…

CAUTION: This translation was made using Google Translate by someone who neither speaks nor reads German. It should not be considered accurate by scholarly standards.