Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Island Museum Painting

November 9, 2013

This post is one of several that seek to determine how many images exist of Great Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855. To learn why this is necessary, please read this post introducing the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

(Wisconsin Historical Society, Image ID: 3957)

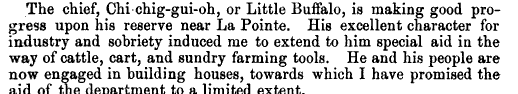

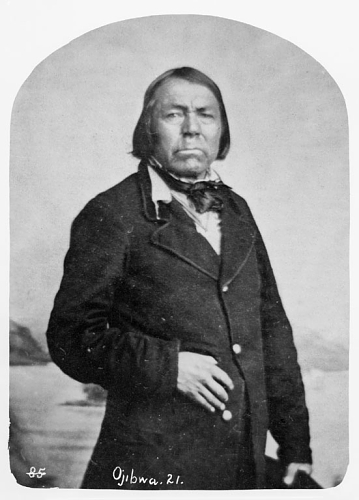

If any image has been as closely tied to Chief Buffalo from La Pointe as the the bust of the Leech Lake Buffalo in Washington, it is an image of a kindly but powerful-looking man in a U.S. Army jacket with a medal around his neck. This image appears on the cover of the 1999 edition of Walleye Warriors, by treaty-rights activist Walter Bresette and Rick Whaley. It is identified as Buffalo in both Ronald Satzʼs Chippewa Treaty Rights, and Patty Loewʼs Indian Nations of Wisconsin. It occupies a prominent position in the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society and hangs in the Madeline Island Museum, but in spite of the enduring popularity of this image, very little is known about it.

As I have not been able to thoroughly examine the originals or find any information whatsoever about their creation, chain of custody, or even when they entered the Historical Society’s collections, this post will be the most speculative of the Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

There are two versions of this image. One appears to be an early type of photograph. The Wisconsin Historical Society describes it as “over-painted enlargement, possibly from a double-portrait (possibly an ambrotype).” I’ve been told by staff that the painting that hangs in the museum is a copy of this earlier version.

A photograph of the original image is in the Societyʼs archives as part of the Hamilton Nelson Ross collection. On the back of the photo, “Chief Buffalo, Grandson of Great Chief Buffalo” is handwritten, presumably by Ross. This description would seem to indicate that the image shows one of Chief Buffaloʼs grandsons. However, we need to be careful trusting Ross as a source of information about Buffalo’s family.

Ross, a resident of Madeline Island, gathered volumes of information on his home community in preparation for his book La Pointe Village Outpost on Madeline Island (1960). Although the book is exhaustively researched and highly detailed about the white and mix-blooded populations of the Island, it contains precious little information about individual Indians. The image of Buffalo is not in the book. In fact, the only mention of the chief comes in a footnote about his grave on page 177:

O-Shaka was also known as O-Shoga and Little Buffalo, and he was the son of Chief Great Buffalo. The latter’s Ojibway name was Bezhike, but he was also known as Kechewaishkeenh–the latter with a variety of spellings. Bezhike’s tombstone, in the Indian cemetery, has had the name broken off…

Oshogay was not Buffalo’s son (though he may have been a son-in-law), and he was not the man known as “Little Buffalo,” but until his untimely death in 1853, he seemed destined to take over leadership of Buffalo’s “Red Cliff” faction of the La Pointe Band. The one who did ultimately step into that role, however, was Buffalo’s son Jayjigwyong (Che-chi-gway-on):

Drew, C.K. Report of the Chippewa Agency of Lake Superior. 26 Oct. 1858. Printed in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. 1858 (Digitized by Google Books)

We will return to Jayjigwyong later in the post, but for now, let’s examine the image itself.

The man in the picture wears an early 19th-century army jacket and a medal. This is consistent with the practices of Chief Buffalo’s day. The custom of handing out flags, jackets, and medals goes back at least to the 1700s with the French. The practice continued under the British and Americans as a way of recognizing certain individuals as chiefs and asserting imperial claims. For the chiefs, the items were symbolic of agreements and alliances. Large councils, treaty signings, and diplomatic missions were all occasions where they were given out. Buffalo had received medals and jackets from the British, and between 1820 and 1855, he took part in the negotiations of at least five treaties, many council meetings and annuity payments, visited Washington, and frequently went back and forth to the agency at Sault Ste. Marie. The United States Government favored Buffalo over the more forcefully-independent chiefs on the Ojibwe-Dakota frontier in Minnesota. Considering all this, it is likely that Buffalo received many jackets, flags, and medals from the Americans over the course of his long interaction with them. An excerpt from a letter by teacher Granville Sproat, who lived in the Lake Superior region in the 1830s reads:

Ke-che Be-zhe-kee, or Big Buffalo, as he was called by the Americans, was then chief of that band of Ogibway Indians who dwell on the south-west shores of Lake Superior, and were best known as the Lake Indians. He was wise and sagacious in council, a great orator, and was much reverenced by the Indians for his supposed intercourse with the Man-i-toes, or spirits, from whom they believed he derived much of his eloquence and wisdom in governing the affairs of the tribe.

“In the summer of 1836, his only son, a young man of rare promise, suddenly sickened and died. The old chief was almost inconsolable for his loss, and, as a token of his affection for his son, had him dressed and laid in the grave in the same military coat, together with the sword and epaulettes, which he had received a few months before as a present from the great father [president] at Washington. He also had placed beside him his favorite dog, to be his companion on his journey to the land of souls (qtd. in Peebles 107).

It is strange that Sproat says Buffalo had only one son given that his wife Florantha Sproat references another son in her description of this same funeral, but sorting out Buffalo’s descendants has never been an easy task. There are references to many sons, daughters, and wives over the course of his very long life.

Another description from the Treaty of 1842 reads:

On October 1 Buffalo appeared, wearing epaulettes on his shoulders, a hat trimmed with tinsel, and a string of bear claws about his neck (Dietrich qtd. in Paap 177-78).

From these accounts we know that Buffalo had these kinds of coats, but dozens of other Ojibwe chiefs would have had similar ones, so the identification cannot be made based on the existence of the coat alone. Consider Naaganab at the 1855 annuity payment:

Na-gon-ub is head chief of the Fond du Lac bands; about the age of forty, short and close built, inclines to ape the dandy in dress, is very polite, neat and tidy in his attire. At first, he appeared in his native blanket, leggings, &c. He soon drew from the Agent a suit of rich blue broadcloth, fine vest, and neat blue cap,–his tiny feet in elegant finely-wrought moccasins. Mr. L., husband of Grace G., with whom he was a special favorite, presented him with a pair of white kid gloves, which graced his hands on all occasions. Some two or three years since, he visited Washington, a delegate from his tribe. Upon this journey, some one presented him with a pair of large and gaudy epaulettes, said to be worth sixty dollars. These adorned his shoulders daily; his hair was cut shorter than their custom. He quite inclined to be with, and to mingle in the society, of the officers, and of white men. These relied on him more, perhaps, than any other chief, for assistance among the Chippewas… (Morse pg. 346)

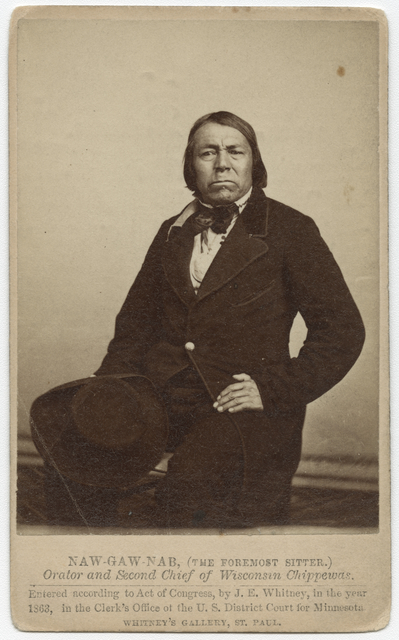

Portrait of Naw-Gaw-Nab (The Foremost Sitter) n.d by J.E. Whitney of St. Paul (Smithsonian)

In many ways, this description of Naaganab fits the image better than any description of Buffalo I’ve seen. The man is dressed in European fashion, has short hair, and large epaulets. We also know that Naaganab had presidential medals, since he continued to display them until his death in the 1890s. The image isn’t dated, but if it truly is an ambrotype, as described by the State Historical Society, that is a technique of photography used mostly in the late 1850s and 1860s. When Buffalo died in 1855, he was reported to be in his nineties. Naaganab would have been in his forties or fifties at that time. To me, the man in the image appears middle-aged rather than elderly.

So is Naaganab the man in the picture? I don’t think so. For one, there are multiple photographs of the Fond du Lac chief out there. The clothing and hairstyle largely match, but the face is different. The other thing to consider is that this image, to my knowledge, has never been identified with Naaganab. Everything I’ve ever seen associates it with the name Buffalo.

However, there is a La Pointe chief who was a political ally of Naaganab, also dressed in white fashion, could have easily owned a medal and fancy army jacket, would have been middle-aged in the 1850s, and bore the English name of “Buffalo.” It was Jayjigwyong, the son of Chief Buffalo.

Alfred Brunson recorded the following in 1843:

(pg. 158) From elsewhere in the account, we know that the “fifty” year-old is Chief Buffalo. This is odd, as most sources had Buffalo in his eighties at that time.

(pg. 191)

Unlike his famous father, Jayjigwyong, often recorded as “Little Buffalo,” is hardly remembered, but he is a significant figure in the history of our region. He was a signatory of the treaties of 1837, 1847, and 1854. He led the faction of the La Pointe Band that felt that rapid assimilation represented the best chance for the Ojibwe to survive and keep their lands. In addition to wearing white clothing and living in houses, Jayjigwyong was Catholic and associated more with the mix-blooded population of the Island than with the majority of the La Pointe band who sought to maintain their traditions at Bad River.

According to James Blackbird, whose father Makadebineshiinh (Black Bird) led the Bad River faction, it was Jayjigwyong who chose where the Red Cliff reservation was to be. James Blackbird, about eleven or twelve at the time of the Treaty of 1854, would have known both the elder and younger Buffalo.

Statement of James Blackbird in the Matters of the Allotments on the Bad River Reservation, Wis. Odanah, 23 Sep. 1909. Published in Condition of Indian affairs in Wisconsin: hearings before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, [61st congress, 2d session], on Senate resolution, Issue 263. United States Congress. 1910. Pg. 202.

The younger Blackbird, offered more information about the younger Buffalo in another publication.

Even though it is from 1915, there are a number of items in this account that if accurate are very relevant to pre-1860 history. For this post, I’ll stick to the two that involve Jayjigwyong. This is the only source I’ve ever seen that refers to Chief Buffalo marrying a white woman captured on a raid. This lends further credence to the argument explored by Dietrich and Paap that Chief Buffalo fought in the Ohio Valley wars of the 1790s. It also begs the question of whether being perceived as a “half-breed” had an impact on Jayjigwyong’s decisions as an adult.

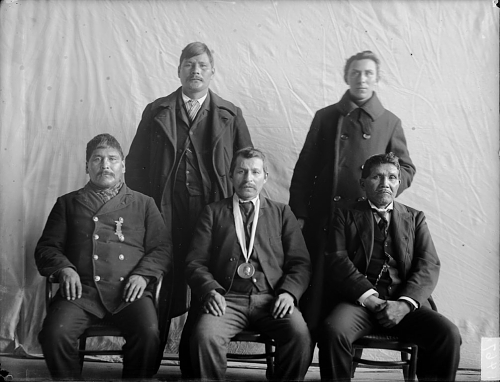

James Blackbird (seated) with interpreter John Medeguan in Washington, 1899. (Photo by Gil DeLancy, Smitsonian Collections)

The other interesting part of the statement is that James Blackbird says his father was pipe carrier for Jayjigwyong. This would be surprising as Blackbird was the most influential La Pointe chief after the death of Buffalo. However, this idea of Jayjigwyong, inheriting the symbolic “head chief” title from his father can also be seen in the following document from 1857:

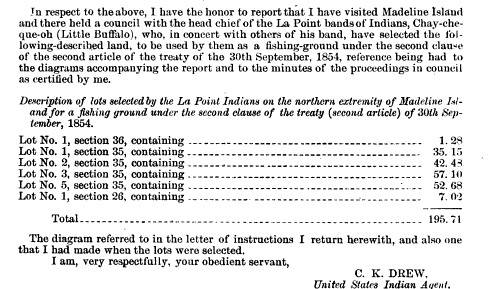

Published in Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior. Office of Indian Affairs. 1882. pg. 299. (Digitized by Google Books)

Today the fishing ground at the tip of Madeline Island is now considered part of the Bad River Reservation, but it was the Red Cliff chief who picked it out. This shows how the political division of the La Pointe Band into two distinct entities took several years to take shape, and was not an abrupt split at the Treaty of 1854.

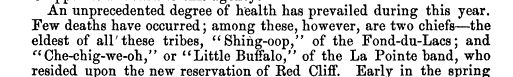

Jayjigwyong continued to be regarded as a chief until his death in 1860:

Drew, C.K. Report on the Chippewas of Lake Superior. Red Cliff Agency. 29 Oct. 1860. Pg. 51 of Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Bureau of Indian Affairs. 1860. (Digitized by Google Books). Zhingob (Shing-oop) was Naaganab’s cousin and the hereditary chief at Fond du Lac. Also known as Nindibens, he figures prominently in Edmund F. Ely’s journals of the mid-1830s.

Future generations of the Buffalo family continued to be looked at as hereditary chiefs in Red Cliff, and sources can be found calling these grandsons and great-grandsons “Chief Buffalo.”

J.H. Beers and Co. Commemorative Biographical Record of the Upper Lake Region. 1905. Pg. 379. (Digitized by Google Books).

Antoine brings us full circle. If we remember, Hamiton Ross wrote that the image of the chief in the army jacket was Chief Buffalo’s grandson. And while we don’t know where Ross got his information, and he made mistakes about Buffalo’s family elsewhere, we have to consider that Antoine Buffalo was an adult by 1852 and he could have inherited his father’s, or grandfather’s, medal and coat.

The Verdict

Although we’ve uncovered several lines of inquiry for this image, all the evidence is circumstantial. Until we know more about the creation and chain of custody, it’s impossible to rule Chief Buffalo in or out. My gut tells me it’s Buffalo’s son, Jajigwyong, but it could be his grandson, Naaganab, or and entirely different chief. We don’t know.

Sources:

Brunson, Alfred. A Western Pioneer, Or, Incidents of the Life and times of Rev. Alfred Brunson Embracing a Period of over Seventy Years. Cinncinnati: Hitchchock and Walden, 1872. Print.

Commemorative Biographical Record of the Upper Lake Region. Chicago: J. H. Beers &, 1905. Print.

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 21 June 2012. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Loew, Patty. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2001. Print.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Peebles, J. M. Immortality, and Our Employments Hereafter. With What a Hundred Spirits, Good and Evil, Say of Their Dwelling Places. Boston: Colby and Rich, 1880. Print.

Ross, Hamilton Nelson. La Pointe, Village Outpost. St. Paul: North Central Pub., 1960. Print

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. The Voice of the Crane Echoes Afar: The Sociopolitical Organization of the Lake Superior Ojibwa, 1640-1855. New York: Garland Pub.,1997. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Whaley, Rick, and Walter Bresette. Walleye Warriors: The Chippewa Treaty Rights Story. Warner, NH: Tongues of Green Fire, Writers Pub. Cooperative, 1999. Print.

Reconstructing the “Martell” Delegation through Newspapers

November 2, 2013

Symbolic Petition of the Chippewa Chiefs: This pictographic petition was brought to Washington D.C. by a delegation of Ojibwe chiefs and their interpreter J.B. Martell. This one, representing the band of Chief Oshkaabewis, is the most famous, but their were several others copied from birch bark by Seth Eastman and published in the works of Henry Schoolcraft. For more, follow this link.

Henry Schoolcraft. William W. Warren. George Copway. These names are familiar to any scholar of mid-19th-century Ojibwe history. They are three of the most referenced historians of the era, and their works provide a great deal of historical material that is not available in any other written sources. Copway was Ojibwe, Warren was a mix-blood Ojibwe, and Schoolcraft was married to the granddaughter of the great Chequamegon chief Waabojiig, so each is seen, to some extent, as providing an insider’s point of view. This could lead one to conclude that when all three agree on something, it must be accurate. However, there is a danger in over-relying on these early historians in that we forget that they were often active participants in the history they recorded.

This point was made clear to me once again as I tried to sort out my lingering questions about the 1848-49 “Martell” Delegation to Washington. If you are a regular reader, you may remember that this delegation was the subject of the first post on this website. You may also remember from this post, that the group did not have money to get to Washington and had to reach out to the people they encountered along the way.

The goal of the Martell Delegation was to get the United States to cede back title to the lands surrounding the major Lake Superior Ojibwe villages. The Ojibwe had given this land up in the Treaty of 1842 with the guarantee that they could remain on it. However, by 1848 there were rumors of removal of all the bands east of the Mississippi to unceded land in Minnesota. That removal was eventually attempted, in 1850-51, in what is now called the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

The Martell Delegation remains a little-known part of the removal story, although the pictographs remain popular. Those petitions are remembered because they were published in Henry Schoolcrafts’ Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States (1851) along with the most accessible primary account of the delegation:

In the month of January, 1849, a delegation of eleven Chippewas, from Lake Superior, presented themselves at Washington, who, amid other matters not well digested in their minds, asked the government for a retrocession of some portion of the lands which the nation had formerly ceded to the United States, at a treaty concluded at Lapointe, in Lake Superior, in 1842. They were headed by Oshcabawiss, a chief from a part of the forest-country, called by them Monomonecau, on the head-waters of the River Wisconsin. Some minor chiefs accompanied them, together with a Sioux and two boisbrules, or half-breeds, from the Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The principal of the latter was a person called Martell, who appeared to be the master-spirit and prime mover of the visit, and of the motions of the entire party. His motives in originating and conducting the party, were questioned in letters and verbal representations from persons on the frontiers. He was freely pronounced an adventurer, and a person who had other objects to fulfil, of higher interest to himself than the advancement of the civilization and industry of the Indians. Yet these were the ostensible objects put forward, though it was known that he had exhibited the Indians in various parts of the Union for gain, and had set out with the purpose of carrying them, for the same object, to England. However this may be, much interest in, and sympathy for them, was excited. Officially, indeed, their object was blocked up. The party were not accredited by their local agent. They brought no letter from the acting Superintendent of Indian Affairs on that frontier. The journey had not been authorized in any manner by the department. It was, in fine, wholly voluntary, and the expenses of it had been defrayed, as already indicated, chiefly from contributions made by citizens on the way, and from the avails of their exhibitions in the towns through which they passed; in which, arrayed in their national costume, they exhibited their peculiar dances, and native implements of war and music. What was wanting, in addition to these sources, had been supplied by borrowing from individuals.

Martell, who acted as their conductor and interpreter, brought private letters from several persons to members of Congress and others, which procured respect. After a visit, protracted through seven or eight weeks, an act was passed by Congress to defray the expenses of the party, including the repayment of the sums borrowed of citizens, and sufficient to carry them back, with every requisite comfort, to their homes in the north-west. While in Washington, the presence of the party at private houses, at levees, and places of public resort, and at the halls of Congress, attracted much interest; and this was not a little heightened by their aptness in the native ceremonies, dancing, and their orderly conduct and easy manners, united to the attraction of their neat and well-preserved costume, which helped forward the object of their mission.

The visit, although it has been stated, from respectable sources, to have had its origin wholly in private motives, in the carrying out of which the natives were made to play the part of mere subordinates, was concluded in a manner which reflects the highest credit on the liberal feelings and sentiments of Congress. The plan of retrocession of territory, on which some of the natives expressed a wish to settle and adopt the modes of civilized life, appeared to want the sanction of the several states in which the lands asked for lie. No action upon it could therefore be well had, until the legislatures of these states could be consulted (pg. 414-416, pictographic plates follow).

I have always had trouble with Schoolcraft’s interpretation of these events. It wasn’t that I had evidence to contradict his argument, but rather that I had a hard time believing that all these chiefs would make so weighty a decision as to go to Washington simply because their interpreter was trying to get rich. The petitions asked for a permanent homeland in the traditional villages east of the Mississippi. This was the major political goal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe leadership at that time and would remain so in all the years leading up to 1854. Furthermore, chiefs continued to ask for, or go “uninvited” on, diplomatic missions to the president in the years that followed.

I explored some of this in the post about the pictograph, but a number of lingering questions remained:

What route did this group take to Washington?

Who was Major John Baptiste Martell?

Did he manipulate the chiefs into working for him, or was he working for them?

Was the Naaganab who went with this group the well-known Fond du Lac chief or the warrior from Lake Chetek with the same name?

Did any chiefs from the La Pointe band go?

Why was Martell criticized so much? Did he steal the money?

What became of Martell after the expedition?

How did the “Martell Expedition” of 1848-49 impact the Ojibwe removal of 1850-51?

Lacking access to the really good archives on this subject, I decided to focus on newspapers, and since this expedition received so much attention and publicity, this was a good choice. Enjoy:

Indiana Palladium. Vevay, IN. Dec. 2, 1848

Capt. Seth Eastman of the U.S. Army took note of the delegation as it traveled down the Mississippi from Fort Snelling to St. Louis. Eastman, a famous painter of American Indians, copied the birch bark petitions for publication in the works of his collaborator Henry Schoolcraft. At least one St. Louis paper also noticed these unique pictographic documents.

Lafayette Courier. Lafayette, IN. Dec. 8, 1848.

Lafayette Courier. Lafayette, IN. Dec. 8, 1848.

The delegation made its way up the Ohio River to Cincinnati, where Gezhiiyaash’s illness led to a chance encounter with some Ohio Freemasons. I won’t repeat it here, but I covered this unusual story in this post from August.

At Cincinnati, they left the river and headed toward Columbus. Just east of that city, on the way to Pittsburgh, one of the Ojibwe men offered some sound advice to the women of Hartford, Ohio, but he received only ridicule in return.

Madison Weekly Courier. Madison, IN. Jan. 24, 1849

It’s unclear how quickly reports of the delegation came back to the Lake Superior country. William Warren’s letter to his cousin George, written in March after the delegation had already left Washington, still spoke of St. Louis:

William W. Warren (Wikimedia Images)

“…About Martells Chiefs. They were according to last accounts dancing the pipe dance at St. Louis. They have been making monkeys of themselves to fill the pockets of some cute Yankee who has got hold of them. Black bird returned from Cleveland where he caught scarlet fever and clap. He has behaved uncommon well since his return…” (Schenck, pg. 49)

From this letter, we learn that Blackbird, the La Pointe chief, was originally part of the group. In evaluating Warren’s critical tone, we must remember that he was working closely with the very government officials who withheld their permission. Of the La Pointe chiefs, Blackbird was probably the least accepting of American colonial power. However, we see in the obituary of Naaganab, Blackbird’s rival at the 1855 annuity payment, that the Fond du Lac chief was also there.

New York World. New York. July 22, 1894

Before finding this obituary, I had thought that the Naaganab who signed the petition was more likely the headman from Lake Chetek. Instead, this information suggests it was the more famous Fond du Lac chief. This matters because in 1848, Naaganab was considered the speaker for his cousin Zhingob, the leading chief at Fond du Lac. Blackbird, according to his son James, was the pipe carrier for Buffalo. While these chiefs had their differences with each other, it seems likely that they were representing their bands in an official capacity. This means that the support for this delegation was not only from “minor chiefs” as Schoolcraft described them, or “Martells Chiefs” as Warren did, from Lac du Flambeau and Michigan. I would argue that the presence of Blackbird and Naaganab suggests widespread support from the Lake Superior bands. I would guess that there was much discussion of the merits of a Washington delegation by Buffalo and others during the summer of 1848, and that the trip being a hasty money-making scheme by Martell seems much less likely.

Madison Daily Banner. Madison, IN. Jan. 3, 1849.

From Pittsburgh, the delegation made it to Philadelphia, and finally Washington. They attracted a lot of attention in the nation’s capital. Some of their adventures and trials: Oshkaabewis and his wife Pammawaygeonenoqua losing an infant child, the group hunting rabbits along the Potomac, and the chiefs taking over Congress, are included this post from March, so they aren’t repeated here.

Adams Sentinel. Gettysburg, PA. Feb. 5, 1849.

According to Ronald Satz, the delegation was received by both Congress and President Polk with “kindly feelings” and the expectation of “good treatment in the future” if they “behaved themselves (Satz 51).” Their petition was added to the Congressional Record, but the reservations were not granted at the time. However, Congress did take up the issue of paying for the debts accrued by the Ojibwe along the way.

George Copway (Wikimedia Commons)

Kah-Ge-Ga-Gah-Bowh (George Copway), a Mississauga Ojibwe and Methodist missionary, was the person “belonging to one of the Canada Bands of Chippewas,” who wrote the anti-Martell letter to Indian Commissioner William Medill. This is most likely the letter Schoolcraft referred to in 1851. In addition to being upset about the drinking, Copway was against reservations in Wisconsin. He wanted the government to create a huge pan-Indian colony at the headwaters of the Missouri River.

William Medill (Wikimedia Commons)

Iowa State Gazette. Burlington, IA. April 4, 1849

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Feb. 28, 1849.

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Feb. 28, 1849.

With $6000 (or did they only get $5000?), a substantial sum for the antebellum Federal Government, the group prepared to head back west with the ability to pay back their creditors.

It appears the chiefs returned to their villages by going back though the Great Lakes to Green Bay and then overland.

The Chippewa Delegation, who have been on a visit to see their “great fathers” in Washington, passed through this place on Saturday last, on their way to their homes near Lake Superior. From the accounts of the newspapers, they have been lionized during their whole journey, and particularly in Washington, where many presents were made them, among the most substantial of which was six boxed of silver ($6,000) to pay their expenses. They were loaded with presents, and we noticed one with a modern style trunk strapped to his back. They all looked well and in good spirits (qtd. in Paap, pg. 205).

Green Bay Gazette. April 4, 1849

So, it hardly seems that the Ojibwe chiefs returned to their villages feeling ripped off by their interpreter. Martell himself returned to the Soo, and found a community about to be ravaged by a epidemic of cholera.

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Sep. 5, 1849.

Martell appears in the 1850 census on the record of those deceased in the past year. Whether he was a major in the Mexican War, whether he was in the United States or Canadian military, or whether it was even a real title, remains a mystery. His death record lists his birthplace as Minnesota, which probably connects him to the Martells of Red Lake and Red River, but little else is known about his early years. And while we can’t say for certain whether he led the group purely out of self-interest, or whether he genuinely supported the cause, John Baptiste Martell must be remembered as a key figure in the struggle for a permanent Ojibwe homeland in Wisconsin and Michigan. He didn’t live to see his fortieth birthday, but he made the 1848-49 Washington delegation possible.

So how do we sort all this out?

To refresh, my unanswered questions from the other posts about this delegation were:

1) What route did this group take to Washington?

2) Who was Major John Baptiste Martell?

3) Did he manipulate the chiefs into working for him, or was he working for them?

4) Was the Naaganab who went with this group the well-known Fond du Lac chief or the warrior from Lake Chetek with the same name?

5) Did any chiefs from the La Pointe band go?

6) Why was Martell criticized so much? Did he steal the money?

7) What became of Martell after the expedition?

8) How did the “Martell Expedition” of 1848-49 impact the Ojibwe removal of 1850-51?

We’ll start with the easiest and work our way to the hardest. We know that the primary route to Washington was down the Brule, St. Croix, and Mississippi to St. Louis, and from there up the Ohio. The return trip appears to have been via the Great Lakes.

We still don’t know how Martell became a major, but we do know what became of him after the diplomatic mission. He didn’t survive to see the end of 1849.

The Fond du Lac chief Naaganab, and the La Pointe chief Blackbird, were part of the group. This indicates that a wide swath of the Lake Superior Ojibwe leadership supported the delegation, and casts serious doubt on the notion that it was a few minor chiefs in Michigan manipulated by Martell.

Until further evidence surfaces, there is no reason to support Schoolcraft’s accusations toward Martell. Even though these allegations are seemingly validated by Warren and Copway, we need to remember how these three men fit into the story. Schoolcraft had moved to Washington D.C. by this point and was no longer Ojibwe agent, but he obviously supported the power of the Indian agents and favored the assimilation of his mother-in-law’s people. Copway and Warren also worked closely with the Government, and both supported removal as a way to separate the Ojibwe from the destructive influences of the encroaching white population. These views were completely opposed to what the chiefs were asking for: permanent reservations at the traditional villages. Because of this, we need to consider that Schoolcraft, Warren, and Copway would be negatively biased toward this group and its interpreter.

Finally there’s the question Howard Paap raises in Red Cliff, Wisconsin. How did this delegation impact the political developments of the early 1850s? In one sense the chiefs were clearly pleased with the results of the trip. They made many friends in Congress, in the media, and in several American cities. They came home smiling with gifts and money to spread to their people. However, they didn’t obtain their primary goal: reservations east of the Mississippi, and for this reason, the following statement in Schoolcraft’s account stands out:

The plan of retrocession of territory, on which some of the natives expressed a wish to settle and adopt the modes of civilized life, appeared to want the sanction of the several states in which the lands asked for lie. No action upon it could therefore be well had, until the legislatures of these states could be consulted.

“Kindly feelings” from President Polk didn’t mean much when Zachary Taylor and a new Whig administration were on the way in. Meanwhile, Congress and the media were so wrapped up in the national debate over slavery that they forgot all about the concerns of the Ojibwes of Lake Superior. This allowed a handful of Indian Department officials, corrupt traders, and a crooked, incompetent Minnesota Territorial governor named Alexander Ramsey to force a removal in 1850 that resulted in the deaths of 400 Ojibwe people in the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

It is hard to know how the chiefs felt about their 1848-49 diplomatic mission after Sandy Lake. Certainly their must have been a strong sense that they were betrayed and abandoned by a Government that had indicated it would support them, but the idea of bypassing the agents and territorial officials and going directly to the seat of government remained strong. Another, much more famous, “uninvited” delegation brought Buffalo and Oshogay to Washington in 1852, and ultimately the Federal Government did step in to grant the Ojibwe the reservations. Almost all of the chiefs who made the journey, or were shown in the pictographs, signed the Treaty of 1854 that made them.

Sources:

McClurken, James M., and Charles E. Cleland. Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights / James M. McClurken, Compiler ; with Charles E. Cleland … [et Al.]. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State UP, 2000. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Seth Eastman. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Collected and Prepared under the Direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per Act of Congress of March 3rd, 1847. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo, 1851. Print.

The banner at the top of this website reads “Primary history of the Chequamegon Region before 1860. In the About page, I explain that 1860 is really an arbitrary round number, and what I’m really focusing on is this area before it became dominated by an English-speaking American society. This is not an easy date to pinpoint, though I think most would argue it happened between 1842 and 1855. While the Treaty of La Pointe in 1854 is an easy marker of separation between the two eras, I would argue that the annuity payments that took place on the island the next summer, can also be seen as a watershed moment in history.

Crocket McElroy from a short biography in the Cyclopedia of Michigan: historical and biographical, comprising a synopsis of general history of the state, and biographical sketches of men who have, in their various spheres, contributed toward its development. Ed. John Bersey. Western Engraving and Publishing; 1890 (Digitized by Google Books)

The 1855 payment, in many ways, illustrates the change in the relationship between the United States and the Ojibwe people that would characterize the rest of the 19th century and early 20th century. The threats of Ojibwe removal or military conflict between the two nations largely ended with the treaty and the establishment of reservations. However, in their place was a paternalistic and domineering government that felt a responsibility to “civilize the Indian.” No one at this time embodied this idea more than George Manypenny, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and it was Manypenny, himself, who presided over the 1855 payment.

The days were over when master politicians like Buffalo and Flat Mouth could try to negotiate with the Americans as equals while playing them off of the British in Canada at the same time. In fact, Buffalo died during the 1855 payment, and the new generation of chiefs were men who had spent their youth in a time of Ojibwe power, but who would grow old in an era where government Indian Agents would rule the reservations like petty dictators. The men of this generation, Jayjigwyong (“Little Buffalo”) of Red Cliff, Blackbird of Bad River, and Naaganab of Fond du Lac, were the ones who were prominent during the summer of 1855.

Until this point, our knowledge of the 1855 payment cams largely from the essay The Chippewas of Lake Superior by a witness named Richard Morse. Dr. Morse’s writing includes a number of speeches by the Ojibwe leadership and a number of smaller accounts of items that piqued his interest, including the story of Hanging Cloud the female warrior, and the deaths of Buffalo and Oshogay. However, when reading Morse, one gets the sense that he or she is not getting stray observations of an uninformed visitor rather than a complete story.

It was for this reason that I got excited today when I stumbled across a second memoir of the 1855 payment. It comes from Volume 5 of Americana, a turn-of-the-century historical journal. Crocket McElroy, the author, is writing around fifty years after he witnessed the 1855 payment as a young clerk in Bayfield.

We still do not have a full picture of the 1855 payment, since we will never have full written accounts from Blackbird, Naaganab, and the rest of the Ojibwe leadership, but McElroy’s essay does provide an interesting contrast to Morse’s. The two men saw many of the same events but interpreted them very differently. And while McElroy’s racist beliefs skew his observations and make his writing hard to stomach, in some ways his observations are as informative as Morse’s even though his work is considerably shorter:

From Americana v.5 American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

AN INDIAN PAYMENT

By Crocket McElroy

In August 1855 about three thousand Chippewa Indians gathered at the village of Lapointe, on Lapointe Island, Lake Superior, for an Indian Payment and also to hold a council with the commissioner of Indian affairs, who at that time was George W. Monypenny of Ohio. The Indians selected for their orator a chief named Blackbird, and the choice was a good one, as Blackbird held his own well in a long discussion with the commissioner. Blackbird was not one of the haughty style of Indians, but modest in his bearing, with a good command of language and a clear head. In his speeches he showed much ingenuity and ably pleaded the cause of his people. He spoke in Chippewa stopping frequently to give the interpreter time to translate what he said into English. In beginning his address he spoke substantially as follows:

“My great white father, we are pleased to meet you and have a talk with you We are friends and we want to remain friends. We expect to do what you want us to do, and we hope that you will deal kindly with us. We wish to remind you that we are the source from which you have derived all your riches. Our furs, our timber, our lands, everything that we have goes to you; even the gold out of which that chain was forged (pointing to a heavy watch chain that the commissioner carried) came from us, and now we hope that you will not use that chain to bind us.”

Buffalo’s death in 1855 marked the end of an era. Jayjigwyong (Young Buffalo) was no young man when he took over from his father. The connection between Buffalo and Buffalo, New York also appears in Morse on page 368, although he says the names are not connected. If Buffalo did indeed live in the Niagara region, it may lend credence to the hypothesis explored in Paap’s Red Cliff Wisconsin, that Buffalo fought the Americans in the Indian Wars of the 1790s and signed the Treaty of Greenville (Photo: Wikimedia Images).

The commissioner was an amiable man and got along pleasantly with his savage friends, besides managing the council skilfully.

Among the prominent chiefs attending the payment was Buffalo, then called “Old Buffalo,” as he had a son called “Young Buffalo” who was also an old man. Old Buffalo was said to be over one hundred years old. He died during the council and the writer witnessed the funeral. He was buried in the Indian grave yard near the Indian church in Lapointe village. The body was laid on a stretcher formed of two poles laid lengthwise and several poles laid crosswise. The stretcher was carried on the shoulders of four Indians. Following the corpse was a long procession of Indians in irregular order. It was claimed for Buffalo, that he maintained a camp many years before at the mouth of Buffalo Creek on the Niagara River, and that the creek and the present large and flourishing city of Buffalo were named after him.

Naaganab’s (above) comments about Wheeler being ungenerous with food echoed a common Ojibwe complaint about the ABCFM missionaries. Wheeler’s Protestant Ethic of upward mobility and self-reliance made little sense in a tribal society where those who had extra were expected to share. Read The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, edited by Theresa Schenck, for Naaganab’s experience with another missionary two decades earlier. Read this post if you don’t understand why the Ojibwe resented the missionaries over the issue of food (Photo from Newberry Library Collections, Chicago).

Another prominent chief attending the conference was Ne-gon-up, head chief of the Fond du lac Indians. Negonup’s camp was on the south side of the St Louis River in Wisconsin, about where the city of Superior now stands. Negonup was a shrewd, practical Indian and had considerable influence. The writer saw him going to the Indian church one Sunday, there was a squaw on each side of him and one behind, they were said to be his wives. A good and zealous Methodist minister named Wheeler desired to talk to Negonup and his tribe about the Great Spirit. Negonup it is said expressed himself in regard to Mr. Wheeler in this manner:

“Mr. Wheeler comes to us and says he wants to do us good. He looks like a good man and we think he is and we believe his intentions are good, but he does not bring us any proof. Now if Mr. Wheeler will bring to me a good supply of barrels of flour and barrels of pork, for distribution among my people, then I shall be convinced that he is a good man.”

The sessions of the council began on August 30th and were held in the open air on a grass common. On the second day the special police acting under directions from the Indian agent H. Gilbert, seized two barrels of whisky that was being secretly sold to the half-breeds and Indians. The proceedings of the council were suspended and the two barrels of whisky were rolled into the center of the common. Mr. Gilbert then took a hatchet, chopped a hole into each barrel and poured the whiskey out on the ground. A few half-breeds and Indians in the outer edge of the crowd dropped on their knees and sucked some of the whisky out of the grass.

In accordance with the stipulations of a treaty, the government was distributing among the Indians a large quantity of blankets, cotton cloth, calico, and other kinds of cloth to be used for clothing or bedding. Also provisions, farming implements, cooking utensils, and other articles supposed to be useful to the Indians The Indians were entitled to a certain value per head in goods and also in cash. The cash payment was I think two dollars and fifty cents per head. The goods were distributed first to the heads of families. After the goods were disposed of the money was paid in gold and silver.

Notwithstanding the care exercised by the Indian agent to prevent the sale of liquor to Indians they were still able to find it, and occasionally some would be found drunk. One who was acting badly was arrested and confined in a log lockup, and while there created a great disturbance. He pounded his head against the logs and yelled so loud and continuously as to excite the other Indians and some of them became very angry. It was feared they would make trouble and a rumor spread through the village that the Indians would rise that night, break into the jail, release the prisoner and then murder all the white people on the island. As the Indians outnumbered the whites ten to one the excitement became painfully intense and a meeting of whites and half breeds was called to take action. A company of volunteers was organized to assist the Indian agent in searching for and destroying liquors. A systematic and thorough search was made of nearly every building in the village, from attic to cellar. A good deal of liquor was found and promptly destroyed. After two days of this kind of work the danger of murders being committed by drunken Indians was supposed to be past and quiet was restored. Either the laws of the United States give the Indian agent in such cases arbitrary power, or the agent assumed it at any rate it was courageously exercised.

Rev. Leonard Wheeler’s mission was Congregational-Presbyterian, not Methodist as McElroy states. The Fond du Lac Indians were familiar with both Protestant sects, but the “civilized” Fond du Lac chiefs Zhingob (Nindibens) and Naaganab, much like Jayjigwyong in Red Cliff, aligned with the Catholics. This represented a major threat to Wheeler and his virulently anti-Catholic colleagues who envisioned a fully-assimilated Protestant future for the Ojibwe (Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society).

A good many of the Indians were warriors, who were frequently, in fact, almost constantly at war with the Sioux. They were pure savages, totally uncivilized, and the faces of some of them had an expression as utterly destitute of human kindness as I have ever seen in wild beasts. A small portion of them were partially civilized and a very few could talk a little English. Nearly all the Indians came to the island in their own canoes bringing along the entire family.

The agent completed his work in about twenty-five days.

There is hardly anything that a savage Indian has less use for than money and when it comes into his hands he hastens to spend it. It goes quickly into the hands of traders, half-breeds and the partially civilized Indians.

A few days previous to the opening of the council, the Indians gave a war dance which was attended by a large crowd of Indians and whites. A ring about twenty feet in diameter was formed by male Indians and squaws sitting cross legged around it, a number of whom had small unmusical drums. The ceremony commenced with the Indians in the circle singing: “Hi yi yi, i e, i o.” This was the whole song and it was repeated over and over with tiresome monotony, and the drums were beaten to keep time with the singing. After the singing had been going on for some minutes a warrior bounced into the ring and began to talk. Instantly the singing stopped. The orator showed great agitation, no doubt for the purpose of convincing his hearers that he was a brave warrior. He hopped and jumped about the ring, swung his arms violently and pointed toward his enemies in the west. He was apparently telling how badly the Sioux had been beaten in the last fight, or how they would be whipped in the next one, and perhaps also how many scalps he had taken. So soon as the talking stopped the singing would begin again and after a little more of the ridiculous music, another warrior would bounce into the ring and begin his speech.

For this occasion some of the Indians were painted with different colored paints, made out of clay and other coarse materials daubed on without much regard to order or taste. A good many males were entirely naked except that they wore breech clouts. One Indian had one leg painted black and the other red, and his face was daubed with various colored paints, so that except in the form of his body, he looked like anything but a human being. When a few speeches had been made the war dance ended.

During the council a begging party of Indians went the rounds of the camps to solicit donations for a squaw widow with four children, whose husband had been killed by the Sioux. At every tent something was given and the articles were carried along by the party. One of the presents was a dead dog, a rope was tied to the dog’s legs and an Indian put the rope over his head and let the dog hang on his back. The widow marched in the procession she was a large strong woman with long hair in a single braid hanging down her back. To the end of the braid was tied two scalps which dangled about one foot below. It was said she had killed two Sioux in revenge for their killing her husband and had taken their scalps.

Among the notable persons in attendance at the council, was a lady distinguished as a writer of fiction under the pen name of Grace Greenwood. She had been recently married to a Mr. Lippincott and was accompanied by her husband. Mrs. Lippincott. did not look like a healthy woman, but she lived to be forty-nine years older and to be highly respected and honored before she died in the year 1904.

Hopefully this document will contribute to the understanding of our area in the earliest years after the Treaty of 1854. Look for an upcoming post with a letter from Blackbird himself on issues surrounding the payment.

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

McElroy, Crocket. “An Indian Payment.” Americana v.5. American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Western Publishing and Engraving. Cyclopedia of Michigan: historical and biographical, comprising a synopsis of general history of the state, and biographical sketches of men who have, in their various spheres, contributed toward its development. John Bersey Ed. Western Publishing and Engraving Co., 1890.

Maangozid’s Family Tree

April 14, 2013

(Amos Butler, Wikimedia Commons) I couldn’t find a picture of Maangozid on the internet, but loon is his clan, and “loon foot” is the translation of his name. The Northeast Minnesota Historical Center in Duluth has a photograph of Maangozid in the Edmund Ely papers. It is reproduced on page 142 of The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849 (2012) ed. Theresa Schenck.

In the various diaries, letters, official accounts, travelogues, and histories of this area from the first half of the nineteenth century, there are certain individuals that repeatedly find their way into the story. These include people like the Ojibwe chiefs Buffalo of La Pointe, Flat Mouth of Leech Lake, and the father and son Hole in the Day, whose influence reached beyond their home villages. Fur traders, like Lyman Warren and William Aitken, had jobs that required them to be all over the place, and their role as the gateway into the area for the American authors of many of these works ensure their appearance in them. However, there is one figure whose uncanny ability to show up over and over in the narrative seems completely disproportionate to his actual power or influence. That person is Maangozid (Loon’s Foot) of Fond du Lac.

Naagaanab, a contemporary of Maangozid (Undated, Newberry Library Chicago)

In fairness to Maangozid, he was recognized as a skilled speaker and a leader in the Midewiwin religion. His father was a famous chief at Sandy Lake, but his brothers inherited that role. He married into the family of Zhingob (Shingoop, “Balsam”) a chief at Fond du Lac, and served as his speaker. Zhingob was part of the Marten clan, which had produced many of Fond du Lac’s chiefs over the years (many of whom were called Zhingob or Zhingobiins). Maangozid, a member of the Loon clan born in Sandy Lake, was seen as something of an outsider. After Zhingob’s death in 1835, Maangozid continued to speak for the Fond du Lac band, and many whites assumed he was the chief. However, it was younger men of the Marten clan, Nindibens (who went by his father’s name Zhingob) and Naagaanab, who the people recognized as the leaders of the band.

Certainly some of Maangozid’s ubiquity comes from his role as the outward voice of the Fond du Lac band, but there seems to be more to it than that. He just seems to be one of those people who through cleverness, ambition, and personal charisma, had a knack for always being where the action was. In the bestselling book, The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell talks all about these types of remarkable people, and identifies Paul Revere as the person who filled this role in 1770s Massachusetts. He knew everyone, accumulated information, and had powers of persuasion. We all know people like this. Even in the writings of uptight government officials and missionaries, Maangozid comes across as friendly, hilarious, and most of all, everywhere.

Recently, I read The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849 (U. of Nebraska Press; 2012), edited by Theresa Schenck. There is a great string of journal entries spanning from the Fall of 1836 to the summer of 1837. Maangozid, feeling unappreciated by the other members of the band after losing out to Nindibens in his bid for leadership after the death of Zhingob, declares he’s decided to become a Christian. Over the winter, Maangozid visits Ely regularly, assuring the stern and zealous missionary that he has turned his back on the Midewiwin. The two men have multiple fascinating conversations about Ojibwe and Christian theology, and Ely rejoices in the coming conversion. Despite assurances from other Ojibwe that Maangozid has not abandoned the Midewiwin, and cold treatment from Maangozid’s wife, Ely continues to believe he has a convert. Several times, the missionary finds him participating in the Midewiwin, but Maangozid always assures Ely that he is really a Christian.

J.G. Kohl (Wikimedia Commons)

It’s hard not to laugh as Ely goes through these intense internal crises over Maangozid’s salvation when its clear the spurned chief has other motives for learning about the faith. In the end, Maangozid tells Ely that he realizes the people still love him, and he resumes his position as Mide leader. This is just one example of Maangozid’s personality coming through the pages.

If you’re scanning through some historical writings, and you see his name, stop and read because it’s bound to be something good. If you find a time machine that can drop us off in 1850, go ahead and talk to Chief Buffalo, Madeline Cadotte, Hole in the Day, or William Warren. The first person I’d want to meet would be Maangozid. Chances are, he’d already be there waiting.

Anyway, I promised a family tree and here it is. These pages come from Kitchi-Gami: wanderings round Lake Superior (1860) by Johann Georg Kohl. Kohl was a German adventure writer who met Maangozid at La Pointe in 1855.

When Kitchi-Gami was translated from German into English, the original French in the book was left intact. Being an uncultured hillbilly of an American, I know very little French. Here are my efforts at translating using my limited knowledge of Ojibwe, French-Spanish cognates, and Google Translate. I make no guarantees about the accuracy of these translations. Please comment and correct them if you can.

1) This one is easy. This is Gaadawaabide, Maangozid’s father, a famous Sandy Lake chief well known to history. Google says “the one with pierced teeth.” The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary translates it as “he had a gap in his teeth.” Most 19th-century sources call him Broken Tooth, La Breche, or Katawabida (or variants thereof).

2) Also easy–this is the younger Bayaaswaa, the boy whose father traded his life for his when he was kidnapped by the Meskwaki (Fox) (see post from March 30, 2013). Bayaaswaa grew to be a famous chief at Sandy Lake who was instrumental in the 18th-century Ojibwe expansion into Minnesota. Google says “the man who makes dry.” The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary lists bayaaswaad as a word for the animate transitive verb “dry.”

3) Presumably, this mighty hunter was the man Warren called Bi-aus-wah (Bayaaswaa) the Father in History of the Ojibways. That isn’t his name here, but it was very common for Anishinaabe people to have more than one name. It says “Great Skin” right on there. Google has the French at “the man who carries a large skin.” Michiiwayaan is “big animal skin” according to the OPD.

4) Google says “because he had very red skin” for the French. I don’t know how to translate the Ojibwe or how to write it in the modern double-vowel system.

5) Weshki is a form of oshki (new, young, fresh). This is a common name for firstborn sons of prominent leaders. Weshki was the name of Waabojiig’s (White Fisher) son, and Chief Buffalo was often called in Ojibwe Gichi-weshki, which Schoolcraft translated as “The Great Firstborn.”

6) “The Southern Sky” in both languages. Zhaawano-giizhig is the modern spelling. For an fascinating story of another Anishinaabe man, named Zhaawano-giizhigo-gaawbaw (“he stands in the southern sky”), also known as Jack Fiddler, read Killing the Shamen by Thomas Fiddler and James R. Stevens. Jack Fiddler (d.1907), was a great Oji-Cree (Severn Ojibway) chief from the headwaters of the Severn River in northern Ontario. His band was one of the last truly uncolonized Indian nations in North America. He commited suicide in RCMP custody after he was arrested for killing a member of his band who had gone windigo.

7) Google says, “the timber sprout.” Mitig is tree or stick. Something along the lines of sprouting from earth makes sense with “akosh,” but my Ojibwe isn’t good enough to combine them correctly in the modern spelling. Let me know if you can.

8) Google just says, “man red head.” Red Head is clearly the Ojibwe meaning also–miskondibe (OPD).

9) “The Sky is Afraid of the Man”–I can’t figure out how to write this in the modern Ojibwe, but this has to be one of the coolest names anyone has ever had.

**UPDATE** 5/14/13

Thank you Charles Lippert for sending me the following clarifications:

“Kadawibida Gaa-dawaabide Cracked Tooth

Bajasswa Bayaaswaa Dry-one

Matchiwaijan Mechiwayaan Great Hide

Wajki Weshki Youth

Schawanagijik Zhaawano-giizhig Southern Skies

Mitiguakosh Mitigwaakoonzh Wooden beak

Miskwandibagan Miskwandibegan Red Skull

Gijigossekot Giizhig-gosigwad The Sky Fears

“I am cluless on Wajawadajkoa. At first I though it might be a throat word (..gondashkwe) but this name does not contain a “gon”. Human skin usually have the suffix ..azhe, which might be reflected here as aja with a 3rd person prefix w.”

Kohl’s Kitchi-Gami is a very nice, accessible introduction to the culture of this area in the 1850s. It’s a little light on the names, dates, and events of the narrative political history that I like so much, but it goes into detail on things like houses, games, clothing, etc.

There is a lot to infer or analyze from these three pages. What do you think? Leave a comment, and look out for an upcoming post about Tagwagane, a La Pointe chief who challenges the belief that “the Loon totem [is] the eldest and noblest in the land.”