Judge Bell Incidents: King of the Apostle Islands

January 30, 2025

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

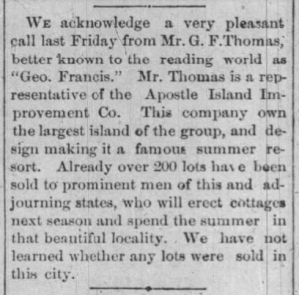

This post is the first of a series featuring The Ashland News items about La Pointe’s infamous Judge John William Bell, written mainly by his son-in-law George Francis Thomas née Gilbert Fayette Thomas a.k.a G.F.T.

Wednesday, September 30, 1885, page 2.

Wednesday, September 30, 1885, page 2.

ON HISTORICAL GROUND.

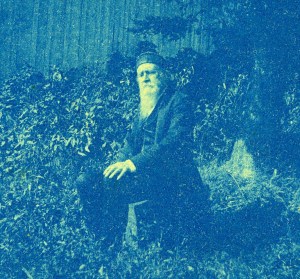

James Chapman

~ Madeline Island Museum

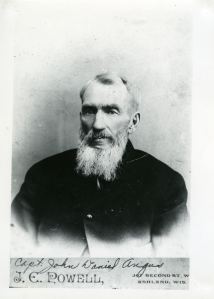

Judge Joseph McCloud

~ Madeline Island Museum

Saturday last, says The Bayfield Press, the editor had the pleasure of visiting Judge John W. Bell at his home at La Pointe, accompanied by Major Wing, James Chapman and Judge Joseph McCloud. The judge, now in his 81st year, still retains much of that indomitable energy that made him for many years a veritable king of the Apostle Islands. Owing, however, to a fractured limb and an irritating ulcer on his foot he is mostly confined to his chair. His recollection of the early history of this country is vivid, while his fund of anecdotes of his early associates is apparently inexhaustible and renders a visit to this remarkable pioneer at once full of pleasure and instruction. The part played by Judge Bell in the early history of this country is one well worthy of preservation and in the hands of competent parties could be made not the least among the many historical sketches of the pioneers of the great northwest. The judge’s present home is a large, roomy house, located in the center of a handsome meadow whose sloping banks are kissed by the waters of the lake he loves so well. Here, surrounded by children and grand-children, cut off from the noise and bustle of the outside world, his sands of life are peacefully passing away.

Leaving La Pointe our little party next visited the site of the Apostle Islands Improvement company’s new summer resort and found it all the most vivid fancy could have painted. Here, also, we met Peter Robedeaux, the oldest surviving voyager of the Hudson Bay Fur Co. Mr. Robedeaux is now in his 89th year, and is as spry as any man not yet turned fifty. He was born near Montreal in 1796, and when only fourteen years of age entered the employ of the Hudson Bay Fur Co., and visited the then far distant waters of the Columbia river, in Washington Territory. He remained in the employ of this company for twenty-five years and then entered the employ of the American Fur company, with headquarters at La Pointe. For fifty years this man has resided on Madeline Island, and the streams tributary to the great lake not visited by him can be numbered by the fingers on one’s hand. His life until the past few years has been one crowded with exciting incidents, many of which would furnish ample material for the ground-work of a novel after the Leather Stocking series style.

Wednesday, June 30, 1886, page 2.

Wednesday, June 30, 1886, page 2.

GOLDEN WEDDING.

About thirty of the old settlers of Ashland and Bayfield went over to La Pointe on Saturday to celebrate the golden wedding anniversary of Judge John W. Bell and wife, who were married in the old church at La Pointe June 26th, 1836, fifty years ago. The party took baskets containing their lunch with them, the old couple having no knowledge of the intended visit. After congratulations had been extended the table was spread, and during the meal many reminiscences of olden times were called up.

Judge Bell is in his eighty-third year, and is becoming quite feeble. Mrs. Bell is perhaps ten or twelve years younger. Judge Bell came to La Pointe in 1834, and has lived there constantly ever since. La Pointe used to be the county seat of Ashland county, and prior to the year 1872 Judge Bell performed the duties of every office of the county. In fact he was virtually king of the island.

The visitors took with them some small golden tokens of regard for the aged couple, the coins left with them aggregating between $75 and $100.

Wednesday, July 20, 1887, page 6.

Wednesday, July 20, 1887, page 6.

REMINISCENCES OF OLD LA POINTE

(Written for The Ashland News)

Visitors to this quiet and delapidated old town on Madeline Island, Lake Superior, about whom early history and traditions so much has been published, are usually surprised when told that less than forty years have passed since there flourished at this point a city of about 2,500 people. Now not more than thirty families live upon the entire island. Thirty-five years ago neither Bayfield, Ashland nor Washburn was thought of, and La Pointe was the metropolis of Northern Wisconsin.

Since interesting himself in the island the writer has often been asked: Why, if there were so many inhabitants there as late as forty years ago, are there so few now? In reply a great number of reasons present themselves, chief among which are natural circumstances, but in the writer’s mind the imperfect land titles clouding old La Pointe for the last thirty years have tended materially to hastening its downfall.

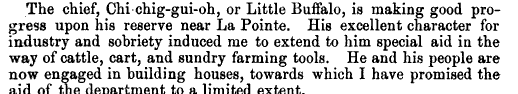

Captain John Daniel Angus

~ Madeline Island Museum

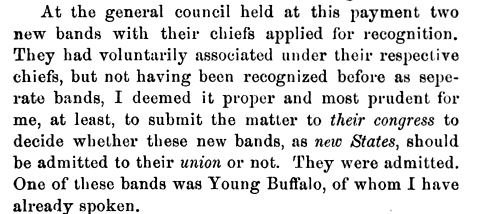

Of the historic data of La Pointe, of which the writer has almost an unlimited supply, much that seems romance is actual fact, and the witnesses of occurrences running back over fifty years are still here upon the island and can be depended upon for the truthfulness of their reminiscences. There are no less than five very old men yet living here who have made their homes upon the island for over fifty years. Judge John W. Bell, or “Squire,” as he is familiarly called, has lived here since the year 1835, coming from the “Soo,” on the brig, John Jacob Astor, in company with another old pioneer of the place known as Capt. John Angus. Mr. Bell contracted with the American Fur Co., and Capt. Angus sailed the “Big Sea” over. Mr. Bell is now eighty three years of age, and is crippled from the effects of a fall received while attending court in Ashland, in Jan. 1884. He is a man of iron constitution and might have lived – and may yet for all we know – to become a centenarian. The hardships of pioneer life endured by the old Judge would have killed an ordinary man long ago. He is a cripple and an invalid, but he has never missed a meal of victuals nor does he show any sign of weakening of his wonderful mind. He delights to relate reminiscences of early days, and will talk for hours to those who prove congenial. Once in his career, Mr. Bell had in his employ the famous “Wilson, the Hermit,” whose romantic history is one of the interesting features sought after by tourists when they visit the islands.

~ History of Northern Wisconsin, by the Western Historical Co., 1881.

Once Mr. Bell started an opposition fur company having for his field of operations that portion of Northern Wisconsin and Michigan now included within the limits of the great Gogebic and Penokee iron ranges, and had in his employ several hundred trappers and carriers. Later Mr. Bell became a prominent explorer, joining numerous parties in the search for gold, silver and copper; iron being considered too inferior a metal for the attention of the popular mind in those days.

Almost with his advent on the island Mr. Bell became a leader in the local political field, during his residence of fifty-two years holding almost continually some one of the various offices within the gift the people. He was also employed at various times by the United States government in connection with Indian affairs, he having a great influence with the natives.

Ramsay Crooks

~ Madeline Island Museum

The American Fur Co., with Ramsay Crooks at its head gave life and sustenance to La Pointe a half century ago, and for several years later, but when a private association composed of Borup, Oakes and others purchased the rights and effects of the American Fur Co., trade at La Pointe began to fall away. The halcyon days were over. The wild animals were getting scarce, and the great west was inducing people to stray. The new fur company eventually moved to St. Paul, where even now their descendants can be found.

Julius Austrian

~ Madeline Island Museum

Prior to the final extinction of the fur trade at La Pointe and in the early days of steamboating on the great lakes, the members of the well-known firm of Leopold & Austrian settled here, and soon gathered about them a number of their relatives, forming quite a Jewish colony. They all became more or less interested in real estate, Julius and Joseph Austrian entering from the government at $1.25 per acre all the lands upon which the village was situated, some 500 acres.

The original patent issued by the government, of which a copy exists in the office of the register of deeds in Ashland, is a literary curiosity, as are also many other title papers issued in early days. Indeed if any one will examine the records and make a correct abstract or title history of old La Pointe, the writer will make such person a present of one of the finest corner lots on the island. Such a thing can not be done simply from the records. A large portion of the original deeds for village lots were simply worthless, but the people in those days never examined into the details, taking every man to be honest, hence errors and wrongs were not found out.

Now the lots are not worth the taxes and interest against them, and the original purchaser will never care whether his title was good or otherwise. The county of Ashland bought almost the whole town site for taxes many years ago and has had an expensive load to carry until the writer at last purchased the tax titles of the village, which includes many of the old buildings. The writer has now shouldered the load, and proposes to preserve the old relics that tourists may continue to visit the island and see a town of “Ye olden times.”

Originally the intention was to form a syndicate to purchase the old town. An association of prominent citizens of Ashland and Bayfield, at one time came very near securing it, and the writer still has hopes of such an association some day controlling the historical spot. The scheme, however, has met with considerable opposition from a few who desire no changes to be made in the administration of affairs on the island. The principal opponent is Julius Austrian, of St. Paul, who still owns one-sixth part of La Pointe, and is expecting to get back another portion of lots, which have been sold for taxes and deeded by the county ever since 1874. He would like no doubt, to make Ashland county stand the taxes on the score of illegality. As a mark of affection for the place, he has lately removed the old warehouse which has stood so many years a prominent landmark in La Pointe’s most beautiful harbor. Tourists from every part of the world who have visited the old town will join in regretting the loss and despise the action.

G. F. T.

To be continued in King No More…

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Island Museum Painting

November 9, 2013

This post is one of several that seek to determine how many images exist of Great Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855. To learn why this is necessary, please read this post introducing the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

(Wisconsin Historical Society, Image ID: 3957)

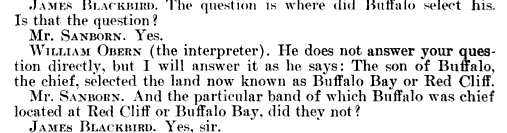

If any image has been as closely tied to Chief Buffalo from La Pointe as the the bust of the Leech Lake Buffalo in Washington, it is an image of a kindly but powerful-looking man in a U.S. Army jacket with a medal around his neck. This image appears on the cover of the 1999 edition of Walleye Warriors, by treaty-rights activist Walter Bresette and Rick Whaley. It is identified as Buffalo in both Ronald Satzʼs Chippewa Treaty Rights, and Patty Loewʼs Indian Nations of Wisconsin. It occupies a prominent position in the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society and hangs in the Madeline Island Museum, but in spite of the enduring popularity of this image, very little is known about it.

As I have not been able to thoroughly examine the originals or find any information whatsoever about their creation, chain of custody, or even when they entered the Historical Society’s collections, this post will be the most speculative of the Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

There are two versions of this image. One appears to be an early type of photograph. The Wisconsin Historical Society describes it as “over-painted enlargement, possibly from a double-portrait (possibly an ambrotype).” I’ve been told by staff that the painting that hangs in the museum is a copy of this earlier version.

A photograph of the original image is in the Societyʼs archives as part of the Hamilton Nelson Ross collection. On the back of the photo, “Chief Buffalo, Grandson of Great Chief Buffalo” is handwritten, presumably by Ross. This description would seem to indicate that the image shows one of Chief Buffaloʼs grandsons. However, we need to be careful trusting Ross as a source of information about Buffalo’s family.

Ross, a resident of Madeline Island, gathered volumes of information on his home community in preparation for his book La Pointe Village Outpost on Madeline Island (1960). Although the book is exhaustively researched and highly detailed about the white and mix-blooded populations of the Island, it contains precious little information about individual Indians. The image of Buffalo is not in the book. In fact, the only mention of the chief comes in a footnote about his grave on page 177:

O-Shaka was also known as O-Shoga and Little Buffalo, and he was the son of Chief Great Buffalo. The latter’s Ojibway name was Bezhike, but he was also known as Kechewaishkeenh–the latter with a variety of spellings. Bezhike’s tombstone, in the Indian cemetery, has had the name broken off…

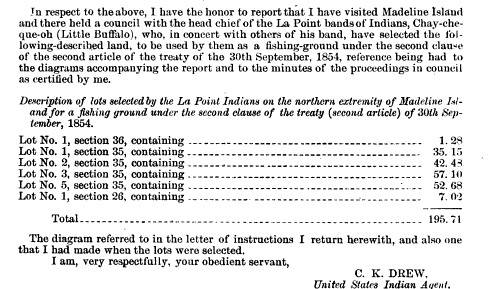

Oshogay was not Buffalo’s son (though he may have been a son-in-law), and he was not the man known as “Little Buffalo,” but until his untimely death in 1853, he seemed destined to take over leadership of Buffalo’s “Red Cliff” faction of the La Pointe Band. The one who did ultimately step into that role, however, was Buffalo’s son Jayjigwyong (Che-chi-gway-on):

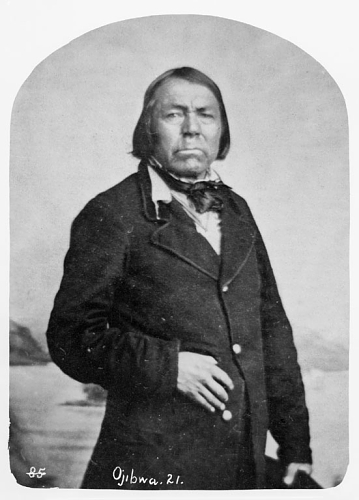

Drew, C.K. Report of the Chippewa Agency of Lake Superior. 26 Oct. 1858. Printed in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. 1858 (Digitized by Google Books)

We will return to Jayjigwyong later in the post, but for now, let’s examine the image itself.

The man in the picture wears an early 19th-century army jacket and a medal. This is consistent with the practices of Chief Buffalo’s day. The custom of handing out flags, jackets, and medals goes back at least to the 1700s with the French. The practice continued under the British and Americans as a way of recognizing certain individuals as chiefs and asserting imperial claims. For the chiefs, the items were symbolic of agreements and alliances. Large councils, treaty signings, and diplomatic missions were all occasions where they were given out. Buffalo had received medals and jackets from the British, and between 1820 and 1855, he took part in the negotiations of at least five treaties, many council meetings and annuity payments, visited Washington, and frequently went back and forth to the agency at Sault Ste. Marie. The United States Government favored Buffalo over the more forcefully-independent chiefs on the Ojibwe-Dakota frontier in Minnesota. Considering all this, it is likely that Buffalo received many jackets, flags, and medals from the Americans over the course of his long interaction with them. An excerpt from a letter by teacher Granville Sproat, who lived in the Lake Superior region in the 1830s reads:

Ke-che Be-zhe-kee, or Big Buffalo, as he was called by the Americans, was then chief of that band of Ogibway Indians who dwell on the south-west shores of Lake Superior, and were best known as the Lake Indians. He was wise and sagacious in council, a great orator, and was much reverenced by the Indians for his supposed intercourse with the Man-i-toes, or spirits, from whom they believed he derived much of his eloquence and wisdom in governing the affairs of the tribe.

“In the summer of 1836, his only son, a young man of rare promise, suddenly sickened and died. The old chief was almost inconsolable for his loss, and, as a token of his affection for his son, had him dressed and laid in the grave in the same military coat, together with the sword and epaulettes, which he had received a few months before as a present from the great father [president] at Washington. He also had placed beside him his favorite dog, to be his companion on his journey to the land of souls (qtd. in Peebles 107).

It is strange that Sproat says Buffalo had only one son given that his wife Florantha Sproat references another son in her description of this same funeral, but sorting out Buffalo’s descendants has never been an easy task. There are references to many sons, daughters, and wives over the course of his very long life.

Another description from the Treaty of 1842 reads:

On October 1 Buffalo appeared, wearing epaulettes on his shoulders, a hat trimmed with tinsel, and a string of bear claws about his neck (Dietrich qtd. in Paap 177-78).

From these accounts we know that Buffalo had these kinds of coats, but dozens of other Ojibwe chiefs would have had similar ones, so the identification cannot be made based on the existence of the coat alone. Consider Naaganab at the 1855 annuity payment:

Na-gon-ub is head chief of the Fond du Lac bands; about the age of forty, short and close built, inclines to ape the dandy in dress, is very polite, neat and tidy in his attire. At first, he appeared in his native blanket, leggings, &c. He soon drew from the Agent a suit of rich blue broadcloth, fine vest, and neat blue cap,–his tiny feet in elegant finely-wrought moccasins. Mr. L., husband of Grace G., with whom he was a special favorite, presented him with a pair of white kid gloves, which graced his hands on all occasions. Some two or three years since, he visited Washington, a delegate from his tribe. Upon this journey, some one presented him with a pair of large and gaudy epaulettes, said to be worth sixty dollars. These adorned his shoulders daily; his hair was cut shorter than their custom. He quite inclined to be with, and to mingle in the society, of the officers, and of white men. These relied on him more, perhaps, than any other chief, for assistance among the Chippewas… (Morse pg. 346)

Portrait of Naw-Gaw-Nab (The Foremost Sitter) n.d by J.E. Whitney of St. Paul (Smithsonian)

In many ways, this description of Naaganab fits the image better than any description of Buffalo I’ve seen. The man is dressed in European fashion, has short hair, and large epaulets. We also know that Naaganab had presidential medals, since he continued to display them until his death in the 1890s. The image isn’t dated, but if it truly is an ambrotype, as described by the State Historical Society, that is a technique of photography used mostly in the late 1850s and 1860s. When Buffalo died in 1855, he was reported to be in his nineties. Naaganab would have been in his forties or fifties at that time. To me, the man in the image appears middle-aged rather than elderly.

So is Naaganab the man in the picture? I don’t think so. For one, there are multiple photographs of the Fond du Lac chief out there. The clothing and hairstyle largely match, but the face is different. The other thing to consider is that this image, to my knowledge, has never been identified with Naaganab. Everything I’ve ever seen associates it with the name Buffalo.

However, there is a La Pointe chief who was a political ally of Naaganab, also dressed in white fashion, could have easily owned a medal and fancy army jacket, would have been middle-aged in the 1850s, and bore the English name of “Buffalo.” It was Jayjigwyong, the son of Chief Buffalo.

Alfred Brunson recorded the following in 1843:

(pg. 158) From elsewhere in the account, we know that the “fifty” year-old is Chief Buffalo. This is odd, as most sources had Buffalo in his eighties at that time.

(pg. 191)

Unlike his famous father, Jayjigwyong, often recorded as “Little Buffalo,” is hardly remembered, but he is a significant figure in the history of our region. He was a signatory of the treaties of 1837, 1847, and 1854. He led the faction of the La Pointe Band that felt that rapid assimilation represented the best chance for the Ojibwe to survive and keep their lands. In addition to wearing white clothing and living in houses, Jayjigwyong was Catholic and associated more with the mix-blooded population of the Island than with the majority of the La Pointe band who sought to maintain their traditions at Bad River.

According to James Blackbird, whose father Makadebineshiinh (Black Bird) led the Bad River faction, it was Jayjigwyong who chose where the Red Cliff reservation was to be. James Blackbird, about eleven or twelve at the time of the Treaty of 1854, would have known both the elder and younger Buffalo.

Statement of James Blackbird in the Matters of the Allotments on the Bad River Reservation, Wis. Odanah, 23 Sep. 1909. Published in Condition of Indian affairs in Wisconsin: hearings before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, [61st congress, 2d session], on Senate resolution, Issue 263. United States Congress. 1910. Pg. 202.

The younger Blackbird, offered more information about the younger Buffalo in another publication.

Even though it is from 1915, there are a number of items in this account that if accurate are very relevant to pre-1860 history. For this post, I’ll stick to the two that involve Jayjigwyong. This is the only source I’ve ever seen that refers to Chief Buffalo marrying a white woman captured on a raid. This lends further credence to the argument explored by Dietrich and Paap that Chief Buffalo fought in the Ohio Valley wars of the 1790s. It also begs the question of whether being perceived as a “half-breed” had an impact on Jayjigwyong’s decisions as an adult.

James Blackbird (seated) with interpreter John Medeguan in Washington, 1899. (Photo by Gil DeLancy, Smitsonian Collections)

The other interesting part of the statement is that James Blackbird says his father was pipe carrier for Jayjigwyong. This would be surprising as Blackbird was the most influential La Pointe chief after the death of Buffalo. However, this idea of Jayjigwyong, inheriting the symbolic “head chief” title from his father can also be seen in the following document from 1857:

Published in Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior. Office of Indian Affairs. 1882. pg. 299. (Digitized by Google Books)

Today the fishing ground at the tip of Madeline Island is now considered part of the Bad River Reservation, but it was the Red Cliff chief who picked it out. This shows how the political division of the La Pointe Band into two distinct entities took several years to take shape, and was not an abrupt split at the Treaty of 1854.

Jayjigwyong continued to be regarded as a chief until his death in 1860:

Drew, C.K. Report on the Chippewas of Lake Superior. Red Cliff Agency. 29 Oct. 1860. Pg. 51 of Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Bureau of Indian Affairs. 1860. (Digitized by Google Books). Zhingob (Shing-oop) was Naaganab’s cousin and the hereditary chief at Fond du Lac. Also known as Nindibens, he figures prominently in Edmund F. Ely’s journals of the mid-1830s.

Future generations of the Buffalo family continued to be looked at as hereditary chiefs in Red Cliff, and sources can be found calling these grandsons and great-grandsons “Chief Buffalo.”

J.H. Beers and Co. Commemorative Biographical Record of the Upper Lake Region. 1905. Pg. 379. (Digitized by Google Books).

Antoine brings us full circle. If we remember, Hamiton Ross wrote that the image of the chief in the army jacket was Chief Buffalo’s grandson. And while we don’t know where Ross got his information, and he made mistakes about Buffalo’s family elsewhere, we have to consider that Antoine Buffalo was an adult by 1852 and he could have inherited his father’s, or grandfather’s, medal and coat.

The Verdict

Although we’ve uncovered several lines of inquiry for this image, all the evidence is circumstantial. Until we know more about the creation and chain of custody, it’s impossible to rule Chief Buffalo in or out. My gut tells me it’s Buffalo’s son, Jajigwyong, but it could be his grandson, Naaganab, or and entirely different chief. We don’t know.