Chief Buffalo’s Death and Conversion: A new perspective

April 18, 2014

By Leo Filipczak

Chief Buffalo died at La Pointe on September 7, 1855 amid the festivities and controversy surrounding that year’s annuity payment. Just before his death, he converted to the Catholic faith, and thus was buried inside the fence of the Catholic cemetery rather than outside with the Ojibwe people who kept traditional religious practices.

His death was noted by multiple written sources at the time, but none seemed to really dive into the motives and symbolism behind his conversion. This invited speculation from later scholars, and I’ve heard and proposed a number of hypotheses about why Buffalo became Catholic.

Now, a newly uncovered document, from a familiar source, reveals new information. And while it may diminish the symbolic impact of Buffalo’s conversion, it gives further insight into an important man whose legend sometimes overshadows his life.

Buffalo’s Obituary

The most well-known account of Buffalo’s death is from an obituary that appeared in newspapers across the country. It was also recorded in the essay, The Chippewas of Lake Superior, by Dr. Richard F. Morse, who was an eyewitness to the 1855 payment.

While it’s not entirely clear if it was Morse himself who wrote the obituary, he seems to be a likely candidate. Much like the rest of Chippewas of Lake Superior, the obituary is riddled with the inaccuracies and betrays an unfamiliarity with La Pointe society:

From Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Volume 3 (Digitized by Google Books)

It isn’t hard to understand how this obituary could invite several interpretations, especially when combined with other sources of the era and the biases of 20th and 21st-century investigators (myself included) who are always looking for a symbolic or political explanation.

Here, we will evaluate these interpretations.

Was Buffalo sending a message to the Ojibwe about the future?

The obituary states, “No tongue like Buffalo’s could control and direct the different bands.” An easy interpretation might suggest that he was trying to send a message that assimilation to white culture was the way of the future, and that all the Ojibwe should follow his lead. We do see suggestions in the writings of Henry Schoolcraft and William Warren that might support this conclusion.

The problem with this interpretation is that no Ojibwe leader, not even Buffalo, had that level of influence. Even if he wanted to, which would have been completely contrary to Ojibwe tolerance of religious pluralism, he could not have pulled a Henry VIII and converted his whole nation.

In fact, by 1855, Buffalo’s influence was at an all-time low. Recent scholarship has countered the image crafted by Benjamin Armstrong and others, of a chief whose trip to Washington and leadership through the Treaty of 1854 made him more powerful in his final years. Consider this 1852 depiction in Wagner and Scherzer’s Reisen in Nordamerika:

…Here we have the hereditary Chippewa chief, whose generations (totem) are carved in the ancient birch bark,** giving us profuse thanks for just a modest silver coin and a piece of dry cloth. What time can bring to a ruler!

So, did Buffalo decide in the last days of his life that Christianity was superior to traditional ways?

The reason why the obituary and other contemporary sources don’t go into the reasons for Buffalo’s conversion was because they hold the implicit assumption that Christianity is the one true religion. Few 19th-century American readers would be asking why someone would convert. It was a given. 160 years later, we don’t make this assumption anymore, but it should be explored whether or not this was purely a religious decision on Buffalo’s part.

I have a difficult time believing this. Buffalo had nearly 100 years to convert to Christianity if he’d wanted to. The traditional Ojibwe, in general, were extremely resistant to conversion, and there are several sources depicting Buffalo as a leader in the Midewiwin. This continuation of the above quote from Wagner and Scherzer shows Buffalo’s relationship to those who felt the Ojibwe needed Christianity.

Strangely, we later learned that the majestic Old Buffalo was violently opposed for years to the education and spiritual progress of the Indians. Probably, it’s because he suspected a better instructed generation would no longer obey. Presently, he tacitly accepts the existence of the school and even visits sometimes, where like ourselves, he has the opportunity to see the gains made in this school with its stubborn, fastidious look of an old German high council.

Accounts like this suggest a political rather than a spiritual motive.

So, did Buffalo’s convert for political rather than spiritual reasons?

Some have tied Buffalo’s conversion to a split in the La Pointe Band after the Treaty of 1854, and it’s important to remember all the heated factional divisions that rose up during the 1855 payment. Until recently, my personal interpretation would have been that Buffalo’s conversion represented a final break with Blackbird and the other Bad River chiefs. Perhaps Buffalo felt alienated from most of the traditional Ojibwe after he found himself in the minority over the issue of debt payments. His final speech was short, and reveals disappointment and exasperation on the part of the aged leader.

By the time of his death, most of his remaining followers, including the mix-blooded Ojibwe of La Pointe, and several of his children were Catholic, while most Ojibwe remained traditional. Perhaps there was additional jealousy over clauses in the treaty that gave Buffalo a separate reservation at Red Cliff and an additional plot of land. We see hints of this division in the obituary when an unidentified Ojibwe man blames the government for Buffalo’s death. This all could be seen as a separation forming between a Catholic Red Cliff and a traditional Bad River.

This interpretation would be perfect if it wasn’t grossly oversimplified. The division didn’t just happen in 1854. The La Pointe Band had always really been several bands. Those, like Buffalo’s, that were most connected to the mix-bloods and traders stayed on the Island more, and the others stayed at Bad River more. Still, there were Catholics at Bad River, and traditional Ojibwe on the Island. This dynamic and Buffalo’s place in it, were well-established. He did not have to convert to be with the “Catholic” faction. He had been in it for years.

Some have questioned whether Buffalo really converted at all. From a political point of view, one could say his conversion was really a show for Commissioner Manypenny to counter Blackbird’s pants (read this post if you don’t know what I’m talking about). I see that as overly cynical and out of character for Buffalo. I also don’t think he was ignorant of what conversion meant. He understood the gravity of what he was deciding, and being a ninety-year-old chief, I don’t think he would have felt pressured to please anyone.

So if it wasn’t symbolic, political, or religious zeal, why did Buffalo convert?

The Kohl article

As he documented the 1855 payment, Richard Morse’s ethnocentric values prevented any meaningful understanding of Ojibwe culture. However, there was another white outsider present at La Pointe that summer who did attempt to understand Ojibwe people as fellow human beings. He had come all the way from Germany.

The name of Johann Georg Kohl will be familiar to many readers who know his work Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings Around Lake Superior (1860). Kohl’s desire to truly know and respect the people giving him information left us with what I consider the best anthropological writing ever done on this part of the world.

My biggest complaint with Kohl is that he typically doesn’t identify people by name. Maangozid, Gezhiiyaash, and Zhingwaakoons show up in his work, but he somehow manages to record Blackbird’s speech without naming the Bad River chief. In over 100 pages about life at La Pointe in 1855, Buffalo isn’t mentioned at all.

So, I was pretty excited to find an untranslated 1859 article from Kohl on Google Books in a German-language weekly. The journal, Das Ausland, is a collection of writings that a would describe as ethnographic with a missionary bent.

I was even more excited as I put it through Google Translate and realized it discussed Buffalo’s final summer and conversion. It has to go out to the English-speaking world.

So without further ado, here is the first seven paragraphs of Remarks on the Conversion of the Canadian Indians and some Stories of Conversion by Johann Kohl. I apologize for any errors arising from the electronic translation. I don’t speak German and I can only hope that someone who does will see this and translate the entire article.

J. G. Kohl (Wikimedia Images)

Das Ausland.

Eine Wochenschrift

fur

Kunde des geistigen und sittlichen Lebens der Völker

[The Foreign Lands: A weekly for scholars of the moral and intellectual lives of foreign nations]

Nr. 2 8 January 1859

Remarks on the Conversion of the Canadian Indians and some Stories of Conversion

By J.G. Kohl

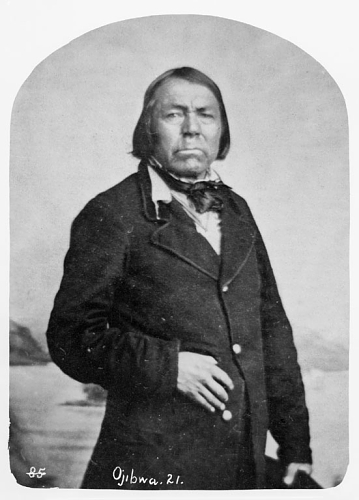

A few years ago, when I was on “La Pointe,” one of the so-called “Apostle Islands” in the western corner of the great Lake Superior, there still lived the old chief of the local Indians, the Chippeway or Ojibbeway people, named “Buffalo,” a man “of nearly a hundred years.” He himself was still a pagan, but many of his children, grandchildren and closest relatives, were already Christians.

I was told that even the aged old Buffalo himself “ébranlé [was shaking]”, and they told me his state of mind was fluctuating. “He thinks highly of the Christian religion,” they told me, “It’s not right to him that he and his family be of a different faith. He is afraid that he will be separated in death. He knows he will not be near them, and that not only his body should be brought to another cemetery, but also he believes his spirit shall go into another paradise away from his children.”

But Buffalo was the main representative of his people, the living embodiment, so to speak, of the old traditions and stories of his tribe, which once ranged over not only the whole group of the Apostle Islands, but also far and wide across the hunting grounds of the mainland of northern Wisconsin. His ancestors and his family, “the Totem of the Loons” (from the diver)* make claim to be the most distinguished chiefly family of the Ojibbeways. Indeed, they believe that from them and their village a far-reaching dominion once reached across all the tribes of the Ojibbeway Nation. In a word, a kind of monarchy existed with them at the center.

(*The Loon, or Diver, is a well-known large North American bird).

Old Buffalo, or Le Boeuf, as the French call him, or Pishiki, his Indian name, was like the last reflection of the long-vanished glory. He was stuck too deep in the old superstition. He was too intertwined with the Medä Order, the Wabanos, and the Jossakids, or priesthood, of his people. A conversion to Christianity would have destroyed his influence in a still mostly-pagan tribe. It would have been the equivalent of voluntarily stepping down from the throne he previously had. Therefore, in spite of his “doubting” state of mind, he could not decide to accept the act of baptism.

One evening, I visited old Buffalo in his bark lodge, and found in him grayed and stooped by the years, but nevertheless still quite a sprightly old man. Who knows what kind of fate he had as an old Indian chief on Lake Superior, passing his whole life near the Sioux, trading with the North West Company, with the British and later with the Americans. With the Wabanos and Jossakids (priests and sorcerers) he conjured for his people, and communed with the sky, but here people would call him an “old sinner.”

But still, due to his advanced age I harbored a certain amount of respect for him myself. He took me in, so kindly, and never forgot even afterwards, promising to remember my visit, as if it had been an honor for him. He told me much of the old glory of his tribe, of the origin of his people, and of his religion from the East. I gave him tobacco, and he, much more generously,gave me a beautiful fife. I later learned from the newspapers that my old host, being ill, and soon after my departure from the island, he departed from this earth. I was seized by a genuine sorrow and grieved for him. Those papers, however, reported a certain cause for consolation, in that Buffalo had said on his deathbed, he desired to be buried in a Christian way. He had therefore received Christianity and the Lord’s Supper, shortly before his death, from the Catholic missionaries, both with the last rites of the Church, and with a church funeral and burial in the Catholic cemetery, where in addition to those already resting, his family would be buried.

The story and the end of the old Buffalo are not unique. Rather, it was something rather common for the ancient pagan to proceed only on his death-bed to Christianity, and it starts not with the elderly adults on their deathbeds, but with their Indian families beginning with their young children. The parents are then won over by the children. For the children, while they are young and largely without religion, the betrayal of the old gods and laws is not so great. Therefore, the parents give allow it more easily. You yourself are probably already convinced that there is something fairly good behind Christianity, and that their children “could do quite well.” They desire for their children to attain the blessing of the great Christian God and therefore often lead them to the missionaries, although they themselves may not decide to give up their own ingrained heathen beliefs. The Christians, therefore, also prefer to first contact the youth, and know well that if they have this first, the parents will follow sooner or later because they will not long endure the idea that they are separated from their children in the faith. Because they believe that baptism is “good medicine” for the children, they bring them very often to the missionaries when they are sick…

Das Ausland: Wochenschrift für Länder- u. Völkerkunde, Volumes 31-32. Only about a quarter of the article is translated above. The remaining pages largely consist of Kohl’s observations on the successes and failures of missionary efforts based on real anecdotes.

Conclusion

According to Johann Kohl, who knew Buffalo, the chief’s conversion wasn’t based on politics or any kind of belief that Ojibwe culture and religion was inferior. Buffalo converted because he wanted to be united with his family in death. This may make the conversion less significant from a historical perspective, but it helps us understand the man himself. For that reason, this is the most important document yet about the end of the great chief’s long life.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892. Print.

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings round Lake Superior. London: Chapman and Hall, 1860. Print.

Loew, Patty. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2001. Print.

McElroy, Crocket. “An Indian Payment.” Americana v.5. American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Seth Eastman. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Collected and Prepared under the Direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per Act of Congress of March 3rd, 1847. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo, 1851. Print.

Wagner, Moritz, and Karl Von Scherzer. Reisen in Nordamerika in Den Jahren 1852 Und 1853. Leipzig: Arnold, 1854. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Perrault, Curot, Nelson, and Malhoit

March 8, 2014

I’ve been getting lazy, lately, writing all my posts about the 1850s and later. It’s easy to find sources about that because they are everywhere, and many are being digitized in an archival format. It takes more work to write a relevant post about the earlier eras of Chequamegon History. The sources are sparse, scattered, and the ones that are digitized or published have largely been picked over and examined by other researchers. However, that’s no excuse. Those earlier periods are certainly as interesting as the mid-19th Century. I needed to just jump in and do a project of some sort.

I’m someone who needs to know the names and personalities involved to truly wrap my head around a history. I’ve never been comfortable making inferences and generalizations unless I have a good grasp of the specific. This doesn’t become easy in the Lake Superior country until after the Cass Expedition in 1820.

But what about a generation earlier?

The dawn of the 19th-century was a dynamic time for our region. The fur trade was booming under the British North West Company. The Ojibwe were expanding in all directions, especially to west, and many of familiar French surnames that are so common in the area arrived with Canadian and Ojibwe mix-blooded voyageurs. Admittedly, the pages of the written record around 1800 are filled with violence and alcohol, but that shouldn’t make one lose track of the big picture. Right or wrong, sustainable or not, this was a time of prosperity for many. I say this from having read numerous later nostalgic accounts from old chiefs and voyageurs about this golden age.

We can meet some of the bigger characters of this era in the pages of William W. Warren and Henry Schoolcraft. In them, men like Mamaangazide (Mamongazida “Big Feet”) and Michel Cadotte of La Pointe, Beyazhig (Pay-a-jick “Lone Man) of St. Croix, and Giishkiman (Keeshkemun “Sharpened Stone”) of Lac du Flambeau become titans, covered with glory in trade, war, and influence. However, there are issues with these accounts. These two authors, and their informants, are prone toward glorifying their own family members. Considering that Schoolcraft’s (his mother-in law, Ozhaawashkodewike) and Warren’s (Flat Mouth, Buffalo, Madeline and Michel Cadotte Jr., Jean Baptiste Corbin, etc.) informants were alive and well into adulthood by 1800, we need to keep things in perspective.

The nature of Ojibwe leadership wasn’t different enough in that earlier era to allow for a leader with any more coercive power than that of the chiefs in 1850s. Mamaangazide and his son Waabojiig may have racked up great stories and prestige in hunting and war, but their stature didn’t get them rich, didn’t get them out of performing the same seasonal labors as the other men in the band, and didn’t guarantee any sort of power for their descendants. In the pages of contemporary sources, the titans of Warren and Schoolcraft are men.

Finally, it should be stated that 1800 is comparatively recent. Reading the journals and narratives of the Old North West Company can make one feel completely separate from the American colonization of the Chequamegon Region in the 1840s and ’50s. However, they were written at a time when the Americans had already claimed this area for over a decade. In fact, the long knife Zebulon Pike reached Leech Lake only a year after Francois Malhoit traded at Lac du Flambeau.

The Project

I decided that if I wanted to get serious about learning about this era, I had to know who the individuals were. The most accessible place to start would be four published fur-trade journals and narratives: those of Jean Baptiste Perrault (1790s), George Nelson (1802-1804), Michel Curot (1803-1804), and Francois Malhoit (1804-1805).

The reason these journals overlap in time is that these years were the fiercest for competition between the North West Company and the upstart XY Company of Sir Alexander MacKenzie. Both the NWC traders (such as Perrault and Malhoit) and the XY traders (Nelson and Curot) were expected to keep meticulous records during these years.

I’d looked at some of these journals before and found them to be fairly dry and lacking in big-picture narrative history. They mostly just chronicle the daily transactions of the fur posts. However, they do frequently mention individual Ojibwe people by name, something that can be lacking in other primary records. My hope was that these names could be connected to bands and villages and then be cross-referenced with Warren and Schoolcraft to fill in some of the bigger story. As the project took shape, it took the form of a map with lots of names on it. I recorded every Ojibwe person by name and located them in the locations where they met the traders, unless they are mentioned specifically as being from a particular village other than where they were trading.

I started with Perrault’s Narrative and tried to record all the names the traders and voyageurs mentioned as well. As they were mobile and much less identified with particular villages, I decided this wasn’t worth it. However, because this is Chequamegon History, I thought I should at least record those “Frenchmen” (in quotes because they were British subjects, some were English speakers, and some were mix-bloods who spoke Ojibwe as a first language) who left their names in our part of the world. So, you’ll see Cadotte, Charette, Corbin, Roy, Dufault (DeFoe), Gauthier (Gokee), Belanger, Godin (Gordon), Connor, Bazinet (Basina), Soulierre, and other familiar names where they were encountered in the journals. I haven’t tried to establish a complete genealogy for either, but I believe Perrault (Pero) and Malhoit (Mayotte) also have names that are still with us.

For each of the names on the map, I recorded the narrative or journal they appeared in:

JBP= Jean Baptiste Perrault

GN= George Nelson

MC= Michel Curot

FM= Francois Malhoit

Red Lake-Pembina area: By this time, the Ojibwe had started to spread far beyond the Lake Superior forests and into the western prairies. Perrault speaks of the Pillagers (Leech Lake Band) being absent from their villages because they had gone to hunt buffalo in the west. Vincent Roy Sr. and his sons later settled at La Pointe, but their family maintained connections in the Canadian borderlands. Jean Baptiste Cadotte Jr. was the brother of Michel Cadotte (Gichi-Mishen), the famous La Pointe trader.

Leech Lake and Sandy Lake area: The names that jump out at me here are La Brechet or Gaa-dawaabide (Broken Tooth), the great Loon-clan chief from Sandy Lake (son of Bayaaswaa mentioned in this post) and Loon’s Foot (Maangozid). The Maangozid we know as the old speaker and medicine man from Fond du Lac (read this post) was the son of Gaa-dawaabide. He would have been a teenager or young man at the time Perrault passed through Sandy Lake.

Fond du Lac and St. Croix: Augustin Belanger and Francois Godin had descendants that settled at La Pointe and Red Cliff. Jean Baptiste Roy was the father of Vincent Roy Sr. I don’t know anything about Big Marten and Little Marten of Fond du Lac or Little Wolf of the St. Croix portage, but William Warren writes extensively about the importance of the Marten Clan and Wolf Clan in those respective bands. Bayezhig (Pay-a-jick) is a celebrated warrior in Warren and Giishkiman (Kishkemun) is credited by Warren with founding the Lac du Flambeau village. Buffalo of the St. Croix lived into the 1840s. I wrote about his trip to Washington in this post.

Lac Courte Oreilles and Chippewa River: Many of the men mentioned at LCO by Perrault are found in Warren. Little (Petit) Michel Cadotte was a cousin of the La Pointe trader, Big (Gichi/La Grande) Michel Cadotte. The “Red Devil” appears in Schoolcraft’s account of 1831. The old, respected Lac du Flambeau chief Giishkiman appears in several villages in these journals. As the father of Keenestinoquay and father-in-law of Simon Charette, a fur-trade power couple, he traded with Curot and Nelson who worked with Charette in the XY Company.

La Pointe: Unfortunately, none of the traders spent much time at La Pointe, but they all mention Michel Cadotte as being there. The family of Gros Pied (Mamaangizide, “Big Feet”) the father of Waabojiig, opened up his lodge to Perrault when the trader was waylaid by weather. According to Schoolcraft and Warren, the old war chief had fought for the French on the Plains of Abraham in 1759.

Lac du Flambeau: Malhoit records many of the same names in Lac du Flambeau that Nelson met on the Chippewa River. Simon Charette claimed much of the trade in this area. Mozobodo and “Magpie” (White Crow), were his brothers-in-law. Since I’ve written so much about chiefs named Buffalo, I should point out that there’s an outside chance Le Taureau (presumably another Bizhiki) could be the famous Chief Buffalo of La Pointe.

L’Anse, Ontonagon, and Lac Vieux Desert: More Cadottes and Roys, but otherwise I don’t know much about these men.

At Mackinac and the Soo, Perrault encountered a number of names that either came from “The West,” or would find their way there in later years. “Cadotte” is probably Jean Baptiste Sr., the father of “Great” Michel Cadotte of La Pointe.

Malhoit meets Jean Baptiste Corbin at Kaministiquia. Corbin worked for Michel Cadotte and traded at Lac Courte Oreilles for decades. He was likely picking up supplies for a return to Wisconsin. Kaministiquia was the new headquarters of the North West Company which could no longer base itself south of the American line at Grand Portage.

Initial Conclusions

There are many stories that can be told from the people listed in these maps. They will have to wait for future posts, because this one only has space to introduce the project. However, there are two important concepts that need to be mentioned. Neither are new, but both are critical to understanding these maps:

1) There is a great potential for misidentifying people.

Any reading of the fur-trade accounts and attempts to connect names across sources needs to consider the following:

- English names are coming to us from Ojibwe through French. Names are mistranslated or shortened.

- Ojibwe names are rendered in French orthography, and are not always transliterated correctly.

- Many Ojibwe people had more than one name, had nicknames, or were referenced by their father’s names or clan names rather than their individual names.

- Traders often nicknamed Ojibwe people with French phrases that did not relate to their Ojibwe names.

- Both Ojibwe and French names were repeated through the generations. One should not assume a name is always unique to a particular individual.

So, if you see a name you recognize, be careful to verify it’s reall the person you’re thinking of. Likewise, if you don’t see a name you’d expect to, don’t assume it isn’t there.

2) When talking about Ojibwe bands, kinship is more important than physical location.

In the later 1800s, we are used to talking about distinct entities called the “St. Croix Band” or “Lac du Flambeau Band.” This is a function of the treaties and reservations. In 1800, those categories are largely meaningless. A band is group made up of a few interconnected families identified in the sources by the names of their chiefs: La Grand Razeur’s village, Kishkimun’s Band, etc. People and bands move across large areas and have kinship ties that may bind them more closely to a band hundreds of miles away than to the one in the next lake over.

I mapped here by physical geography related to trading posts, so the names tend to group up. However, don’t assume two people are necessarily connected because they’re in the same spot on the map.

On a related note, proximity between villages should always be measured in river miles rather than actual miles.

Going Forward

I have some projects that could spin out of these maps, but for now, I’m going to set them aside. Please let me know if you see anything here that you think is worth further investigation.

Sources:

Curot, Michel. A Wisconsin Fur Trader’s Journal, 1803-1804. Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites. Wisconsin Historical Collections, vol. XX: 396-472, 1911.

Malhoit, Francois V. “A Wisconsin Fur Trader’s Journal, 1804-05.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Reuben Gold Thwaites. Vol. 19. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1910. 163-225. Print.

Nelson, George, Laura L. Peers, and Theresa M. Schenck. My First Years in the Fur Trade: The Journals of 1802-1804. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 2002. Print.

Perrault, Jean Baptiste. Narrative of The Travels And Adventures Of A Merchant Voyager In The Savage Territories Of Northern America Leaving Montreal The 28th of May 1783 (to 1820) ed. and Introduction by, John Sharpless Fox. Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections. vol. 37. Lansing: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, Crawford Co., 1900.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Information Respecting The History,Condition And Prospects OF The Indian Tribes Of The United States. Illustrated by Capt. S. Eastman. Published by the Authority of Congress. Part III. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Company, 1953.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi. East Lansing: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Note: This is the final post of four about Lt. James Allen, his ten American soldiers and their experiences on the St. Croix and Brule rivers. They were sent from Sault Ste. Marie to accompany the 1832 expedition of Indian Agent Henry Schoolcraft to the source of the Mississippi River. Each of the posts gives some general information about the expedition and some pages from Allen’s journal.

On the night of August 1, 1831, the section of the Michigan Territory that would become the state of Wisconsin, was a scene of stark contrasts regarding the United States Army’s ability to force its will on Indian people. In the south, American forces had caught up and skirmished with the starving followers of Black Hawk near the mouth of the Bad Axe River in present-day Vernon County. The next morning, with the backing of the steamboat Warrior, the soldiers would slaughter dozens of men, women, and children as they tried to retreat across the Mississippi. The massacre at Bad Axe was the end of the Black Hawk War, the last major military resistance from the Indian nations of the Old Northwest.

Less than 300 miles upstream, Lieutenant James Allen had his bread stolen right out of his fire as he slept. Presumably, it was taken by Ojibwe youths from the Yellow River village on the St. Croix. Earlier that day, he had been unable to get convince any members of the Yellow River band to guide him up to the Brule River portage. The next morning, (the same day as the Battle of Bad Axe), Allen was able to buy a new bark canoe to take some load off his leaky fleet. However, the Ojibwe family that sold it to him was able to take advantage of supply and demand to get twice the amount of flour from the soldiers that they would’ve gotten from the local traders. Later that day, the well-known chief Gaa-bimabi (Kabamappa), from the upper St. Croix, brought him a desperately-needed map, so not all of his interactions with the Ojibwe that day were negative. However, each of these encounters showed clearly that the Ojibwe were neither cowed nor intimidated by the presence of American soldiers in their country.

In fact, Allen’s detachment must have been a miserable sight. They had fallen several days behind the voyageur-paddled canoes carrying Schoolcraft, the interpreter, and the doctor. Their canoes were leaking badly and they were running out of gum (pitch) to seal them up. Their feet were torn up from wading up the rapids, and one man was too injured to walk. They were running low on food, didn’t know how to find the Brule, and their morale was running dangerously low. If the War Department’s plan was for Allen to demonstrate American power to the Ojibwe, the plan had completely backfired.

The journey down the Brule was even more difficult for the soldiers than the trip up the St. Croix. I won’t repeat it all here because it’s in the posted pages of Allen’s journal in these four posts, but in the end, it was our old buddy Maangozid (see 4/14/13 post) and some other Fond du Lac Ojibwe who rescued the soldiers from their ordeal.

Allen’s journal entry after finally reaching Lake Superior is telling:

“[T]he management of bark canoes, of any size, in rapid rivers, is an art which it takes years to acquire; and, in this country, it is only possessed by Canadians [mix-blooded voyageurs] and Indians, whose habits of life have taught them but little else. The common soldiers of the army have no experience of this kind, and consequently, are not generally competent to transport themselves in this way; and whenever it is required to transport troops, by means of bark canoes, two Canadian voyageurs ought to be assigned to each canoe, one in the bow, and another in the stern; it will then be the safest and most expeditious method that can be adopted in this country.”

The 1830s were the years of Indian Removal throughout the United States, but at that time, the American government had no hope of conquering and subduing the Ojibwe militarily. When the Ojibwe did surrender their lands (in 1837 and 1842 for the Wisconsin parts), it was due to internal politics and economics rather than any serious threat of American invasion. Rather than proving the strength of the United States, Allen’s expedition revealed a serious weakness.

The Ojibwe weren’t overconfident or ignorant. The very word for Americans, chimookomaan (long knife), referred to soldiers. A handful of Ojibwe and mix-blooded warriors had fought the United States in the War of 1812 and earlier in the Ohio country. Bizhiki and Noodin, two chiefs whose territory Allen passed through on his ill-fated journey, had been to Washington in 1824 and saw the army firsthand. The next year, many more chiefs got to see the long knives in person at the Treaty of Prairie du Chien. Finally, the removal of their Ottawa and Potawatomi cousins and other nations to Indian Territory in the 1830s was a well-known topic of concern in Ojibwe villages. They knew the danger posed by American soldiers, but the reality of the Lake Superior Country in 1832 was that American power was very limited.

The journal picks up from part 3 with Allen and crew on the Brule River with their canoes in rapidly-deteriorating condition. They’ve made contact with the Fond du Lac villagers camped at the mouth, but there are still several obstacles to overcome.

Doc. 323, pg. 66

Allen’s journal is part of Phillip P. Mason’s edition of Schoolcraft’s Expedition to Lake Itasca: The Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi (1958). However, these Google Books pages come from the original publication as part of the United States Congress Serial Set.

James Allen (1806-1846)

Collections of the Iowa Historical Society

Allen and all of his men survived the ordeal of the 1832 expedition. He returned to La Pointe on August 11 and left the next day with Dr. Houghton. The two men returned to the Soo together, stopping at the great copper rock on the Ontonagon River along the way.

On September 13, 1832, he wrote Alexander Macomb, his commander at Fort Brady. The letter officially complained about Schoolcraft “unnecessarily and injuriously” leaving the soldiers behind at the mouth of the St. Croix. When the New York American published its review of Schoolcraft’s Narrative on July 19, 1834, it expressed “indignation and dismay” at the “un-Christianlike” behavior of the agent for abandoning the soldiers in the “enemy’s country.” The resulting controversy forced Schoolcraft to defend himself in the Detroit Journal and Michigan Advertiser where he pointed out Allen’s map’s importance to the Narrative. He also reminded the public that the Ojibwe and the United States were considered allies.

James Allen went on to serve in Chicago and at the Sac and Fox agency in Iowa Territory. After the Mexican War broke out in 1846, he traveled to Utah and organized a Mormon Battalion to fight on the American side. He died on his way back east on August 23, 1846. He was only forty years old. (John Lindquist has great website about the career of James Allen with much more information about his post-1832 life).

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Loew, Patty. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2001. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi,. [East Lansing]: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.

No Princess Zone: Hanging Cloud, the Ogichidaakwe

May 12, 2013

This image of Aazhawigiizhigokwe (Hanging Cloud) was created 35 years after the battle depicted by Marr and Richards Engraving of Milwaukee for use in Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).

Here is an interesting story I’ve run across a few times. Don’t consider this exhaustive research on the subject, but it’s something I thought was worth putting on here.

In late 1854 and 1855, the talk of northern Wisconsin was a young woman from from the Chippewa River around Rice Lake. Her name was Ah-shaw-way-gee-she-go-qua, which Morse (below) translates as “Hanging Cloud.” Her father was Nenaa’angebi (Beautifying Bird) a chief who the treaties record as part of the Lac Courte Oreilles band. His band’s territory, however, was further down the Chippewa from Lac Courte Oreilles, dangerously close to the territories of the Dakota Sioux. The Ojibwe and Dakota of that region had a long history of intermarriage, but the fallout from the Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1825) led to increased incidents of violence. This, along with increased population pressures combined with hunting territory lost to white settlement, led to an intensification of warfare between the two nations in the mid-18th century.

As you’ll see below, Hanging Cloud gained her fame in battle. She was an ogichidaakwe (warrior). Unfortunately, many sources refer to her as the “Chippewa Princess.” She was not a princess. Her father was not a king. She did not sit in a palace waited on hand and foot. Her marriageability was not her only contribution to her people. Leave the princesses in Europe. Hanging Cloud was an ogichidaakwe. She literally fought and killed to protect her people.

Americans have had a bizarre obsession with the idea of Indian princesses since Pocahontas. Engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe (1616) Wikimedia Images

Americans have had a bizarre obsession with the idea of Indian princesses since Pocahontas. Engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe (1616) Wikimedia ImagesIn An Infinity of Nations, Michael Witgen devotes a chapter to America’s ongoing obsession with the concept of the “Indian Princess.” He traces the phenomenon from Pocahontas down to 21st-century white Americans claiming descent from mythical Cherokee princesses. He has some interesting thoughts about the idea being used to justify the European conquest and dispossession of Native peoples. I’m going to try to stick to history here and not get bogged down in theory, but am going to declare northern Wisconsin a “NO PRINCESS ZONE.”

Ozhaawashkodewekwe, Madeline Cadotte, and Hanging Cloud were remarkable women who played a pivotal role in history. They are not princesses, and to describe them as such does not add to their credit. It detracts from it.

Anyway, rant over, the first account of Hanging Cloud reproduced here comes from Dr. Richard E. Morse of Detroit. He observed the 1855 annuity payment at La Pointe. This was the first payment following the Treaty of 1854, and it was overseen directly by Indian Affairs Commissioner George Manypenny. Morse records speeches of many of the most prominent Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs at the time, records the death of Chief Buffalo in September of that year, and otherwise offers his observations. These were published in 1857 as The Chippewas of Lake Superior in the third volume of the State Historical Society’s Wisconsin Historical Collections. This is most of pages 349 to 354:

“The “Princess”–AH-SHAW-WAY-GEE-SHE-GO-QUA–The Hanging Cloud.

The Chippewa Princess was very conspicuous at the payment. She attracted much notice; her history and character were subjects of general observation and comment, after the bands, to which she was, arrived at La Pointe, more so than any other female who attended the payment.

She was a chivalrous warrior, of tried courage and valor; the only female who was allowed to participate in the dancing circles, war ceremonies, or to march in rank and file, to wear the plumes of the braves. Her feats of fame were not long in being known after she arrived; most persons felt curious to look upon the renowned youthful maiden.

Nenaa’angebi as depicted on the cover of Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).

Nenaa’angebi as depicted on the cover of Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).She is the daughter of Chief NA-NAW-ONG-GA-BE, whose speech, with comments upon himself and bands, we have already given. Of him, who is the gifted orator, the able chieftain, this maiden is the boast of her father, the pride of her tribe. She is about the usual height of females, slim and spare-built, between eighteen and twenty years of age. These people do not keep records, nor dates of their marriages, nor of the birth of their children.

This female is unmarried. No warrior nor brave need presume to win her heart or to gain her hand in marriage, who cannot prove credentials to superior courage and deeds of daring upon the war-path, as well as endurance in the chase. On foot she was conceded the fleetest of her race. Her complexion is rather dark, prominent nose, inclining to the Roman order, eyes rather large and very black, hair the color of coal and glossy, a countenance upon which smiles seemed strangers, an expression that indicated the ne plus ultra of craft and cunning, a face from which, sure enough, a portentous cloud seemed to be ever hanging–ominous of her name. We doubt not, that to plunge the dagger into the heart of an execrable Sioux, would be more grateful to her wish, more pleasing to her heart, than the taste of precious manna to her tongue…

…Inside the circle were the musicians and persons of distinction, not least of whom was our heroine, who sat upon a blanket spread upon the ground. She was plainly, though richly dressed in blue broad-cloth shawl and leggings. She wore the short skirt, a la Bloomer, and be it known that the females of all Indians we have seen, invariably wear the Bloomer skirt and pants. Their good sense, in this particular, at least, cannot, we think, be too highly commended. Two plumes, warrior feathers, were in her hair; these bore devices, stripes of various colored ribbon pasted on, as all braves have, to indicate the number of the enemy killed, and of scalps taken by the wearer. Her countenance betokened self-possession, and as she sat her fingers played furtively with the haft of a good sized knife.

The coterie leaving a large kettle hanging upon the cross-sticks over a fire, in which to cook a fat dog for a feast at the close of the ceremony, soon set off, in single file procession, to visit the camp of the respective chiefs, who remained at their lodges to receive these guests. In the march, our heroine was the third, two leading braves before her. No timid air and bearing were apparent upon the person of this wild-wood nymph; her step was proud and majestic, as that of a Forest Queen should be.

The party visited the various chiefs, each of whom, or his proxy, appeared and gave a harangue, the tenor of which, we learned, was to minister to their war spirit, to herald the glory of their tribe, and to exhort the practice of charity and good will to their poor. At the close of each speech, some donation to the beggar’s fun, blankets, provisions, &c., was made from the lodge of each visited chief. Some of the latter danced and sung around the ring, brandishing the war-club in the air and over his head. Chief “LOON’S FOOT,” whose lodge was near the Indian Agents residence, (the latter chief is the brother of Mrs. Judge ASHMAN at the Soo,) made a lengthy talk and gave freely…

…An evening’s interview, through an interpreter, with the chief, father of the Princess, disclosed that a small party of Sioux, at a time not far back, stole near unto the lodge of the the chief, who was lying upon his back inside, and fired a rifle at him; the ball grazed his nose near his eyes, the scar remaining to be seen–when the girl seizing the loaded rifle of her father, and with a few young braces near by, pursued the enemy; two were killed, the heroine shot one, and bore his scalp back to the lodge of NA-NAW-ONG-GA-BE, her father.

At this interview, we learned of a custom among the Chippewas, savoring of superstition, and which they say has ever been observed in their tribe. All the youths of either sex, before they can be considered men and women, are required to undergo a season of rigid fasting. If any fail to endure for four days without food or drink, they cannot be respected in the tribe, but if they can continue to fast through ten days it is sufficient, and all in any case required. They have then perfected their high position in life.

This Princess fasted ten days without a particle of food or drink; on the tenth day, feeble and nervous from fasting, she had a remarkable vision which she revealed to her friends. She dreamed that at a time not far distant, she accompanied a war party to the Sioux country, and the party would kill one of the enemy, and would bring home his scalp. The war party, as she had dreamed, was duly organized for the start.

Against the strongest remonstrance of her mother, father, and other friends, who protested against it, the young girl insisted upon going with the party; her highest ambition, her whole destiny, her life seemed to be at stake, to go and verify the prophecy of her dream. She did go with the war party. They were absent about ten or twelve days, the had crossed the Mississippi, and been into the Sioux territory. There had been no blood of the enemy to allay their thirst or to palliate their vengeance. They had taken no scalp to herald their triumphant return to their home. The party reached the great river homeward, were recrossing, when lo! they spied a single Sioux, in his bark canoe near by, whom they shot, and hastened exultingly to bear his scalp to their friends at the lodges from which they started. Thus was the prophecy of the prophetess realized to the letter, and herself, in the esteem of all the neighboring bands, elevated to the highest honor in all their ceremonies. They even hold her in superstitious reverence. She alone, of the females, is permitted in all festivities, to associate, mingle and to counsel with the bravest of the braves of her tribe…”

Benjamin Armstrong

Benjamin ArmstrongBenjamin Armstrong’s memoir Early Life Among the Indians also includes an account of the warrior daughter of Nenaa’angebi. In contrast to Morse, the outside observer, Armstrong was married to Buffalo’s niece and was the old chief’s personal interpreter. He lived in this area for over fifty years and knew just about everyone. His memoir, published over 35 years after Hanging Cloud got her fame, contains details an outsider wouldn’t have any way of knowing.

Unfortunately, the details don’t line up very well. Most conspicuously, Armstrong says that Nenaa’angebi was killed in the attack that brought his daughter fame. If that’s true, then I don’t know how Morse was able to record the Rice Lake chief’s speeches the following summer. It’s possible these were separate incidents, but it is more likely that Armstrong’s memories were scrambled. He warns us as much in his introduction. Some historians refuse to use Armstrong at all because of discrepancies like this and because it contains a good deal of fiction. I have a hard time throwing out Armstrong completely because he really does have the insider’s knowledge that is lacking in so many primary sources about this area. I don’t look at him as a liar or fraud, but rather as a typical northwoodsman who knows how to run a line of B.S. when he needs to liven up a story. Take what you will of it, these are pages 199-202 of Early Life Among the Indians.

“While writing about chiefs and their character it may not be amiss to give the reader a short story of a chief‟s daughter in battle, where she proved as good a warrior as many of the sterner sex.

In the ’50’s there lived in the vicinity of Rice Lake, Wis. a band of Indians numbering about 200. They were headed by a chief named Na-nong-ga-bee. This chief, with about seventy of his people came to La Point to attend the treaty of 1854. After the treaty was concluded he started home with his people, the route being through heavy forests and the trail one which was little used. When they had reached a spot a few miles south of the Namekagon River and near a place called Beck-qua-ah-wong they were surprised by a band of Sioux who were on the warpath and then in ambush, where a few Chippewas were killed, including the old chief and his oldest son, the trail being a narrow one only one could pass at a time, true Indian file. This made their line quite long as they were not trying to keep bunched, not expecting or having any thought of being attacked by their life long enemy.

The chief, his son and daughter were in the lead and the old man and his son were the first to fall, as the Sioux had of course picked them out for slaughter and they were killed before they dropped their packs or were ready for war. The old chief had just brought the gun to his face to shoot when a ball struck him square in the forehead. As he fell, his daughter fell beside him and feigned death. At the firing Na-nong-ga-bee’s Band swung out of the trail to strike the flanks of the Sioux and get behind them to cut off their retreat, should they press forward or make a retreat, but that was not the Sioux intention. There was not a great number of them and their tactic was to surprise the band, get as many scalps as they could and get out of the way, knowing that it would be but the work of a few moments, when they would be encircled by the Chippewas. The girl lay motionless until she perceived that the Sioux would not come down on them en-masse, when she raised her father‟s loaded gun and killed a warrior who was running to get her father‟s scalp, thus knowing she had killed the slayer of her father, as no Indian would come for a scalp he had not earned himself. The Sioux were now on the retreat and their flank and rear were being threatened, the girl picked up her father‟s ammunition pouch, loaded the rifle, and started in pursuit. Stopping at the body of her dead Sioux she lifted the scalp and tucked it under her belt. She continued the chase with the men of her band, and it was two days before they returned to the women and children, whom they had left on the trail, and when the brave little heroine returned she had added two scalps to the one she started with.

She is now living, or was, but a few years ago, near Rice Lake, Wis., the wife of Edward Dingley, who served in the war of rebellion from the time of the first draft of soldiers to the end of the war. She became his wife in 1857, and lived with him until he went into the service, and at this time had one child, a boy. A short time after he went to the war news came that all the party that had left Bayfield at the time he did as substitutes had been killed in battle, and a year or so after, his wife, hearing nothing from him, and believing him dead, married again. At the end of the war Dingley came back and I saw him at Bayfield and told him everyone had supposed him dead and that his wife had married another man. He was very sorry to hear this news and said he would go and see her, and if she preferred the second man she could stay with him, but that he should take the boy. A few years ago I had occasion to stop over night with them. And had a long talk over the two marriages. She told me the circumstances that had let her to the second marriage. She thought Dingley dead, and her father and brother being dead, she had no one to look after her support, or otherwise she would not have done so. She related the related the pursuit of the Sioux at the time of her father‟s death with much tribal pride, and the satisfaction she felt at revenging herself upon the murder of her father and kinsmen. She gave me the particulars of getting the last two scalps that she secured in the eventful chase. The first she raised only a short distance from her place of starting; a warrior she espied skulking behind a tree presumably watching for some one other of her friends that was approaching. The other she did not get until the second day out when she discovered a Sioux crossing a river. She said: “The good luck that had followed me since I raised my father‟s rifle did not now desert me,” for her shot had proved a good one and she soon had his dripping scalp at her belt although she had to wade the river after it.”

At this point, this is all I have to offer on the story of Hanging Cloud the ogichidaakwe. I’ll be sure to update if I stumble across anything else, but for now, we’ll have to be content with these two contradictory stories.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892. Print.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.

Maangozid’s Family Tree

April 14, 2013

(Amos Butler, Wikimedia Commons) I couldn’t find a picture of Maangozid on the internet, but loon is his clan, and “loon foot” is the translation of his name. The Northeast Minnesota Historical Center in Duluth has a photograph of Maangozid in the Edmund Ely papers. It is reproduced on page 142 of The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849 (2012) ed. Theresa Schenck.

In the various diaries, letters, official accounts, travelogues, and histories of this area from the first half of the nineteenth century, there are certain individuals that repeatedly find their way into the story. These include people like the Ojibwe chiefs Buffalo of La Pointe, Flat Mouth of Leech Lake, and the father and son Hole in the Day, whose influence reached beyond their home villages. Fur traders, like Lyman Warren and William Aitken, had jobs that required them to be all over the place, and their role as the gateway into the area for the American authors of many of these works ensure their appearance in them. However, there is one figure whose uncanny ability to show up over and over in the narrative seems completely disproportionate to his actual power or influence. That person is Maangozid (Loon’s Foot) of Fond du Lac.

Naagaanab, a contemporary of Maangozid (Undated, Newberry Library Chicago)

In fairness to Maangozid, he was recognized as a skilled speaker and a leader in the Midewiwin religion. His father was a famous chief at Sandy Lake, but his brothers inherited that role. He married into the family of Zhingob (Shingoop, “Balsam”) a chief at Fond du Lac, and served as his speaker. Zhingob was part of the Marten clan, which had produced many of Fond du Lac’s chiefs over the years (many of whom were called Zhingob or Zhingobiins). Maangozid, a member of the Loon clan born in Sandy Lake, was seen as something of an outsider. After Zhingob’s death in 1835, Maangozid continued to speak for the Fond du Lac band, and many whites assumed he was the chief. However, it was younger men of the Marten clan, Nindibens (who went by his father’s name Zhingob) and Naagaanab, who the people recognized as the leaders of the band.

Certainly some of Maangozid’s ubiquity comes from his role as the outward voice of the Fond du Lac band, but there seems to be more to it than that. He just seems to be one of those people who through cleverness, ambition, and personal charisma, had a knack for always being where the action was. In the bestselling book, The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell talks all about these types of remarkable people, and identifies Paul Revere as the person who filled this role in 1770s Massachusetts. He knew everyone, accumulated information, and had powers of persuasion. We all know people like this. Even in the writings of uptight government officials and missionaries, Maangozid comes across as friendly, hilarious, and most of all, everywhere.

Recently, I read The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849 (U. of Nebraska Press; 2012), edited by Theresa Schenck. There is a great string of journal entries spanning from the Fall of 1836 to the summer of 1837. Maangozid, feeling unappreciated by the other members of the band after losing out to Nindibens in his bid for leadership after the death of Zhingob, declares he’s decided to become a Christian. Over the winter, Maangozid visits Ely regularly, assuring the stern and zealous missionary that he has turned his back on the Midewiwin. The two men have multiple fascinating conversations about Ojibwe and Christian theology, and Ely rejoices in the coming conversion. Despite assurances from other Ojibwe that Maangozid has not abandoned the Midewiwin, and cold treatment from Maangozid’s wife, Ely continues to believe he has a convert. Several times, the missionary finds him participating in the Midewiwin, but Maangozid always assures Ely that he is really a Christian.

J.G. Kohl (Wikimedia Commons)

It’s hard not to laugh as Ely goes through these intense internal crises over Maangozid’s salvation when its clear the spurned chief has other motives for learning about the faith. In the end, Maangozid tells Ely that he realizes the people still love him, and he resumes his position as Mide leader. This is just one example of Maangozid’s personality coming through the pages.

If you’re scanning through some historical writings, and you see his name, stop and read because it’s bound to be something good. If you find a time machine that can drop us off in 1850, go ahead and talk to Chief Buffalo, Madeline Cadotte, Hole in the Day, or William Warren. The first person I’d want to meet would be Maangozid. Chances are, he’d already be there waiting.

Anyway, I promised a family tree and here it is. These pages come from Kitchi-Gami: wanderings round Lake Superior (1860) by Johann Georg Kohl. Kohl was a German adventure writer who met Maangozid at La Pointe in 1855.

When Kitchi-Gami was translated from German into English, the original French in the book was left intact. Being an uncultured hillbilly of an American, I know very little French. Here are my efforts at translating using my limited knowledge of Ojibwe, French-Spanish cognates, and Google Translate. I make no guarantees about the accuracy of these translations. Please comment and correct them if you can.

1) This one is easy. This is Gaadawaabide, Maangozid’s father, a famous Sandy Lake chief well known to history. Google says “the one with pierced teeth.” The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary translates it as “he had a gap in his teeth.” Most 19th-century sources call him Broken Tooth, La Breche, or Katawabida (or variants thereof).

2) Also easy–this is the younger Bayaaswaa, the boy whose father traded his life for his when he was kidnapped by the Meskwaki (Fox) (see post from March 30, 2013). Bayaaswaa grew to be a famous chief at Sandy Lake who was instrumental in the 18th-century Ojibwe expansion into Minnesota. Google says “the man who makes dry.” The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary lists bayaaswaad as a word for the animate transitive verb “dry.”

3) Presumably, this mighty hunter was the man Warren called Bi-aus-wah (Bayaaswaa) the Father in History of the Ojibways. That isn’t his name here, but it was very common for Anishinaabe people to have more than one name. It says “Great Skin” right on there. Google has the French at “the man who carries a large skin.” Michiiwayaan is “big animal skin” according to the OPD.

4) Google says “because he had very red skin” for the French. I don’t know how to translate the Ojibwe or how to write it in the modern double-vowel system.

5) Weshki is a form of oshki (new, young, fresh). This is a common name for firstborn sons of prominent leaders. Weshki was the name of Waabojiig’s (White Fisher) son, and Chief Buffalo was often called in Ojibwe Gichi-weshki, which Schoolcraft translated as “The Great Firstborn.”

6) “The Southern Sky” in both languages. Zhaawano-giizhig is the modern spelling. For an fascinating story of another Anishinaabe man, named Zhaawano-giizhigo-gaawbaw (“he stands in the southern sky”), also known as Jack Fiddler, read Killing the Shamen by Thomas Fiddler and James R. Stevens. Jack Fiddler (d.1907), was a great Oji-Cree (Severn Ojibway) chief from the headwaters of the Severn River in northern Ontario. His band was one of the last truly uncolonized Indian nations in North America. He commited suicide in RCMP custody after he was arrested for killing a member of his band who had gone windigo.

7) Google says, “the timber sprout.” Mitig is tree or stick. Something along the lines of sprouting from earth makes sense with “akosh,” but my Ojibwe isn’t good enough to combine them correctly in the modern spelling. Let me know if you can.

8) Google just says, “man red head.” Red Head is clearly the Ojibwe meaning also–miskondibe (OPD).

9) “The Sky is Afraid of the Man”–I can’t figure out how to write this in the modern Ojibwe, but this has to be one of the coolest names anyone has ever had.

**UPDATE** 5/14/13

Thank you Charles Lippert for sending me the following clarifications:

“Kadawibida Gaa-dawaabide Cracked Tooth

Bajasswa Bayaaswaa Dry-one

Matchiwaijan Mechiwayaan Great Hide

Wajki Weshki Youth

Schawanagijik Zhaawano-giizhig Southern Skies

Mitiguakosh Mitigwaakoonzh Wooden beak

Miskwandibagan Miskwandibegan Red Skull

Gijigossekot Giizhig-gosigwad The Sky Fears

“I am cluless on Wajawadajkoa. At first I though it might be a throat word (..gondashkwe) but this name does not contain a “gon”. Human skin usually have the suffix ..azhe, which might be reflected here as aja with a 3rd person prefix w.”

Kohl’s Kitchi-Gami is a very nice, accessible introduction to the culture of this area in the 1850s. It’s a little light on the names, dates, and events of the narrative political history that I like so much, but it goes into detail on things like houses, games, clothing, etc.

There is a lot to infer or analyze from these three pages. What do you think? Leave a comment, and look out for an upcoming post about Tagwagane, a La Pointe chief who challenges the belief that “the Loon totem [is] the eldest and noblest in the land.”

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings round Lake Superior. London: Chapman and Hall, 1860. Print.

Miller, Cary. Ogimaag: Anishinaabeg Leadership, 1760-1845. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2010. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Kah-puk-wi-e-kah: Cornucopia, Herbster, or Port Wing?

March 30, 2013

Official railroad map of Wisconsin, 1900 / prepared under the direction of Graham L. Rice, Railroad Commissioner. (Library of Congress) Check out Steamboat Island in the upper right. According to the old timers, that’s the one that washed away.

Not long ago, a long-running mystery was solved for me. Unfortunately, the outcome wasn’t what I was hoping for, but I got to learn a new Ojibwe word and a new English word, so I’ll call it a victory. Plus, there will be a few people–maybe even a dozen who will be interested in what I found out.

Go Big Red!

First a little background for those who haven’t spent much time in Cornucopia, Herbster, or Port Wing. The three tiny communities on the south shore have a completely friendly but horribly bitter animosity toward one another. Sure they go to school together, marry each other, and drive their firetrucks in each others’ parades, but every Cornucopian knows that a Fish Fry is superior to a Smelt Fry, and far superior to a Fish Boil. In the same way, every Cornucopian remembers that time the little league team beat PW. Yeah, that’s right. It was in the tournament too!

If you haven’t figured it out yet, my sympathies lie with Cornucopia, and most of the animosity goes to Port Wing (after all, the Herbster kids played on our team). That’s why I’m upset with the outcome of this story even though I solved a mystery that had been nagging me.

“A bay on the lake shore situated forty miles west of La Pointe…”

This all began several years ago when I read William W. Warren’s History of the Ojibway People for the first time. Warren, a mix-blood from La Pointe, grew up speaking Ojibwe on the island. His American father sent him to the East to learn to read and write English, and he used his bilingualism to make a living as an interpreter when he returned to Lake Superior. His mother was a daughter of Michel and Madeline Cadotte, and he was related to several prominent people throughout Ojibwe country. His History is really a collection of oral histories obtained in interviews with chiefs and elders in the late 1840s and early 1850s. He died in 1853 at age 28, and his manuscript sat unpublished for several decades. Luckily for us, it eventually was, and for all its faults, it remains the most important book about the history of this area.

As I read Warren that first time, one story in particular jumped out at me:

Warren, William W. History of the Ojibway Nation. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1885. Print. Pg. 127 Available on Google Books.

Pg. 129 Warren uses the sensational racist language of the day in his description of warfare between the Fox and his Ojibwe relatives. Like most people, I cringe at lines like “hellish whoops” or “barbarous tortures which a savage could invent.” For a deeper look at Warren the man, his biases, and motivations, I strongly recommend William W. Warren: the life, letters, and times of an Ojibwe leader by Theresa Schenck (University of Nebraska Press, 2007)

I recognized the story right away:

Cornucopia, Wisconsin postcard image by Allan Born. In the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society (WHI Image ID: 84185)

This marker, put up in 1955, is at the beach in Cornucopia. To see it, go east on the little path by the artesian well.

It’s clear Warren is the source for the information since it quotes him directly. However, there is a key difference. The original does not use the word “Siskiwit” (a word derived from the Ojibwe for the “Fat” subspecies of Lake Trout abundant around Siskiwit Bay) in any way. It calls the bay Kah-puk-wi-e-kah and says it’s forty miles west of La Pointe. This made me suspect that perhaps this tragedy took place at one of the bays west of Cornucopia. Forty miles seemed like it would get you a lot further west of La Pointe than Siskiwit Bay, but then I figured it might be by canoe hugging the shoreline around Point Detour. This would be considerably longer than the 15-20 miles as the crow flies, so I was somewhat satisfied on that point.

Still, Kah-puk-wi-e-kah is not Siskiwit, so I wasn’t certain the issue was resolved. My Ojibwe skills are limited, so I asked a few people what the word means. All I could get was that the “Kah” part was likely “Gaa,” a prefix that indicates past tense. Otherwise, Warren’s irregular spelling and dropped endings made it hard to decipher.

Then, in 2007, GLIFWC released the amazing Gidakiiminaan (Our Earth): An Anishinaabe Atlas of the 1836, 1837, and 1842 Treaty Ceded Territories. This atlas gives Ojibwe names and translations for thousands of locations. On page 8, they have the south shore. Siskiwit Bay is immediately ruled out as Kah-puk-wi-e-kah, and so is Cranberry River (a direct translation of the Ojibwe Mashkiigiminikaaniwi-ziibi. However, two other suspects emerge. Bark Bay (the large bay between Cornucopia and Herbster) is shown as Apakwaani-wiikwedong, and the mouth of the Flagg River (Port Wing) is Gaa-apakwaanikaaning.

On the surface, the Port Wing spelling was closer to Warren’s, but with “Gaa” being a droppable prefix, it wasn’t a big difference. The atlas uses the root word apakwe to translate both as “the place for getting roofing-bark,” Apakwe in this sense referring to rolls of birch bark covering a wigwam. For me it was a no-brainer. Bark Bay is the biggest, most defined bay in the area. Port Wing’s harbor is really more of a swamp on relatively straight shoreline. Plus, Bark Bay has the word “bark” right in it. Bark River goes into Bark Bay which is protected by Bark Point. Bark, bark, bark–roofing bark–Kapukwiekah–done.

Cornucopia had lost its one historical event, but it wasn’t so bad. Even though Bark Bay is closer to Herbster, it’s really between the two communities. I was even ready to suggest taking the word “Siskiwit” off the sign and giving it to Herbster. I mean, at least it wasn’t Port Wing, right?

Over the next few years, it seemed my Bark Bay suspicions were confirmed. I encountered Joseph Nicollet’s 1843 map of the region:

Then in 2009, Theresa Schenck of the University of Wisconsin-Madison released an annotated second edition of Warren’s History. Dr. Schenck is a Blackfeet tribal member but is also part Ojibwe from Lac Courte Oreilles. She is, without doubt, the most knowledgeable and thorough researcher currently working with written records of Ojibwe history. In her edition of Warren, the story begins on page 83, and she clearly has Kah-puk-wi-e-kah footnoted as Bark Bay–mystery solved!

But maybe not. Just this past year, Dr. Schenck edited and annotated the first published version of The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849. Ely was a young Protestant missionary working for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) in the Ojibwe communities of Sandy Lake, Fond du Lac, and Pokegama on the St. Croix. He worked under Rev. Sherman Hall of La Pointe, and made several trips to the island from Fond du Lac and the Brule River. He mentions the places along the way by what they were called in the 1830s and 40s. At one point he gets lost in the woods northwest of La Pointe, but he finds his way to the Siscoueka sibi (Siskiwit River). Elsewhere are references to the Sand, Cranberry, Iron, and “Bruley” Rivers, sometimes by their Ojibwe names and sometimes translated.

On almost all of these trips, he mentions passing or stopping at Gaapukuaieka, and to Ely and all those around him, Gaapukuaieka means the mouth of the Flagg River (Port Wing).

There is no doubt after reading Ely. Gaapukuaieka is a well-known seasonal camp for the Fond du Lac and La Pointe bands and a landmark and stopover on the route between those two important Ojibwe villages. Bark Bay is ruled out, as it is referred to repeatedly as Wiigwaas Point/Bay, referring to birch bark more generally. The word apakwe comes up in this book not in reference to bark, but as the word for rushes or cattails that are woven into mats. Ely even offers “flagg” as the English equivalent for this material. A quick dictionary search confirmed this meaning. Gaapukuaieka is Port Wing, and the name of the Flagg River refers to the abundance of cattails and rushes.

My guess is that the good citizens of Cornucopia asked the State Historical Society to put up a historical marker in 1955. Since no one could think of any history that happened in Cornucopia, they just pulled something from Warren assuming no one would ever check up on it. Now Cornucopia not just faces losing its only historical event, it faces the double-indignity of losing it to Port Wing.

William Whipple Warren (1825-1853) wrote down the story of Bayaaswaa from the oral history of the chief’s descendents.

So what really happened here?

Because the oral histories in Warren’s book largely lack dates, they can be hard to place in time. However, there are a few clues for when this tragedy may have happened. First, we need a little background on the conflict between the “Fox” and Ojibwe.

The Fox are the Meskwaki, a nation the Ojibwe called the Odagaamiig or “people on the other shore.” Since the 19th-century, they have been known along with the Sauk as the “Sac and Fox.” Today, they have reservations in Iowa, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Warfare between the Chequamegon Ojibwe and the Meskwaki broke out in the second half of the 17th-century. At that time, the main Meskwaki village was on the Fox River near Green Bay. However, the Meskwaki frequently made their way up the Wisconsin River to the Ontonagon and other parts of what is now north-central Wisconsin. This territory included areas like Lac du Flambeau, Mole Lake, and Lac Vieux Desert. The Ojibwe on the Lake Superior shore also wanted to hunt these lands, and war broke out. The Dakota Sioux were also involved in this struggle for northern Wisconsin, but there isn’t room for them in this post.

In theory, the Meskwaki and Ojibwe were both part of a huge coalition of nations ruled by New France, and joined in trade and military cooperation against the Five Nations or Iroquois Confederacy. In reality, the French at distant Quebec had no control over large western nations like the Ojibwe and Meskwaki regardless of what European maps said about a French empire in the Great Lakes. The Ojibwe and Meskwaki pursued their own politics and their own interests. In fact, it was the French who ended up being pulled into the Ojibwe war.

What history calls the “Fox Wars” (roughly 1712-1716 and 1728-1733) were a series of battles between the Meskwaki (and occasionally their Mascouten, Kickapoo, and Sauk relatives) against everyone else in the French alliance. For the Ojibwe of Chequamegon, this fight started several decades earlier, but history dates the beginning at the point when everyone else got involved.

By the end of it, the Meskwaki were decimated and had to withdraw from northern Wisconsin and seek shelter with the Sauk. The only thing that kept them from being totally eradicated was the unwillingness of their Indian enemies to continue the fighting (the French, on the other hand, wanted a complete genocide). The Fox Wars left northern Wisconsin open for Ojibwe expansion–though the Dakota would have something to say about that.

So, where does this story of father and son fit? Warren, as told by the descendents of the two men, describes this incident as the pivotal event in the mid-18th century Ojibwe expansion outward from Lake Superior. He claims the war party that avenged the old chief took possession of the former Meskwaki villages, and also established Fond du Lac as a foothold toward the Dakota lands.

According to Warren, the child took his father’s name Bi-aus-wah (Bayaaswaa) and settled at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi. From Sandy Lake, the Ojibwe systematically took control of all the major Dakota villages in what is now northern Minnesota. This younger Bayaaswaa was widely regarded as a great and just leader who tried to promote peace and “rules of engagement” to stop the sort of kidnapping and torture that he faced as a child. Bayaaswaa’s leadership brought prestige to his Loon Clan, and future La Pointe leaders like Andeg-wiiyaas (Crow’s Meat) and Bizhiki (Buffalo), were Loons.

So, how much of this is true, and how much are we relying on Warren for this story? It’s hard to say. The younger Bayaaswaa definitely appears in both oral and written sources as an influential Sandy Lake chief. His son Gaa-dawaabide (aka. Breche or Broken Tooth) became a well-known chief in his own right. Both men are reported to have lived long lives. Broken Tooth’s son, Maangozid (Loon’s Foot) of Fond du Lac, was one of several grandsons of Bayaaswaa alive in Warren’s time and there’s a good chance he was one of Warren’s informants.

Caw-taa-waa-be-ta, Or The Snagle’d Tooth by James Otto Lewis, 1825 (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: WHi-26732) “Broken Tooth” was the son of Bayaaswaa the younger and the grandson of the chief who gave his life. Lewis was self-taught, and all of his portraits have the same grotesque or cartoonish look that this one does.