When we die, we will lay our bones at La Pointe.

March 20, 2024

By Leo

From individual historical documents, it can be hard to sequence or make sense of the efforts of the United States to remove the Lake Superior Ojibwe from ceded territories of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan in the years 1850 and 1851. Most of us correctly understand that the Sandy Lake Tragedy was caused an alliance of government and trading interests. Through greed, deception, racism, and callous disregard for human life, government officials bungled the treaty payment at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi River in the fall and winter of 1850-51, leading to hundreds of deaths. We also know that in the spring of 1852, Chief Buffalo and a delegation of La Pointe Ojibwe chiefs travelled to Washington D.C. to oppose the removal. It is what happened before and between those events, in the summers of 1850 and 1851, where things get muddled.

Confusion arises because the individual documents can contradict our narrative. A particular trader, who we might want to think is one of the villains, might express an anti-removal view. A government agent, who we might wish to assign malicious intent, instead shows merely incompetence. We find a quote or letter that seems to explain the plans and sentiments leading to the disaster at Sandy Lake, but then we find the quote is dated after the deaths had already occurred.

Therefore, we are fortunate to have the following letter, written in November of 1851, which concisely summarizes the events up to that point. We are even more fortunate that the letter is written by chiefs, themselves. It is from the Office of Indian Affairs archives, but I found a copy in the Theresa Schenck papers. It is not unknown to Lake Superior scholarship, but to my knowledge it has not been reproduced in full.

The context is that Chief Buffalo, most (but not all) of the La Pointe chiefs, and some of their allies from Ontonagon, L’Anse, Upper St. Croix Lake, Chippewa River and St. Croix River, have returned to La Pointe. They have abandoned the pay ground at Fond du Lac in November 1851, and returned to La Pointe. This came after getting confirmation that the Indian Agent, John S. Watrous, has been telling a series of lies in order to force a second Sandy Lake removal–just one year removed from the tragedy. This letter attempts to get official sanction for a delegation of La Pointe chiefs to visit Washington. The official sanction never came, but the chiefs went anyway, and the rest is history.

La Pointe, Lake Superior, Nov. 6./51

To the Hon Luke Lea

Commissioner of Indian Affairs Washington D.C.

Our Father,

We send you our salutations and wish you to listen to our words. We the Chiefs and head men of the Chippeway Tribe of Indians feel ourselves aggrieved and wronged by the conduct of the U.S. Agent John S. Watrous and his advisors now among us. He has used great deception towards us, in carrying out the wishes of our Great Father, in respect to our removal. We have ever been ready to listen to the words of our Great Father whenever he has spoken to us, and to accede to his wishes. But this time, in the matter of our removal, we are in the dark. We are not satisfied that it is the President that requires us to remove. We have asked to see the order, and the name of the President affixed to it, but it has not been shewn us. We think the order comes only from the Agent and those who advise with him, and are interested in having us remove.

Kicheueshki. Chief. X his mark

Gejiguaio X “

Kishkitauʋg X “

Misai X “

Aitauigizhik X “

Kabimabi X “

Oshoge, Chief X “

Oshkinaue, Chief X “

Medueguon X “

Makudeua-kuʋt X “

Na-nʋ-ʋ-e-be, Chief X “

Ka-ka-ge X “

Kui ui sens X “

Ma-dag ʋmi, Chief X “

Ua-bi-shins X “

E-na-nʋ-kuʋk X “

Ai-a-bens, Chief X “

Kue-kue-Kʋb X “

Sa-gun-a-shins X “

Ji-bi-ne-she, Chief X “

Ke-ui-mi-i-ue X “

Okʋndikʋn, Chief X “

Ang ua sʋg X “

Asinise, Chief X “

Kebeuasadʋn X “

Metakusige X “

Kuiuisensish, Chief X “

Atuia X “

Gete-kitigani[inini? manuscript torn]

L. H. Wheeler

We the undersigned, certify, on honor, that the above document was shown to us by the Buffalo, Chief of the Lapointe band of Chippeway Indians and that we believe, without implying and opinion respecting the subjects of complaint contained in it, that it was dictated by, and contains the sentiments of those whose signatures are affixed to it.

S. Hall

C. Pulsifer

H. Blatchford

When I started Chequamegon History in 2013, the WordPress engine made it easy to integrate their features with some light HTML coding. In recent years, they have made this nearly impossible. At some point, we’ll have to decide whether to get better at coding or overhaul our signature “blue rectangle” design format. For now, though, I can’t get links or images into the blue rectangles like I used to, so I will have to list them out here:

Joseph Austrian’s description of the same

Boutwell’s acknowledgement of the suspension of the removal order, and his intent to proceed anyway

Chequamegon History has looked into the “Great Father” fur trade theater language of ritual kinship before in our look at Blackbird’s speech at the 1855 Payment. You may have noticed Makadebines (Blackbird) didn’t sign this letter. He was working on a different plant to resist removal. Look for a related post soon.

If you’re really interested in why the president was Gichi-noos (Great Father), read these books:

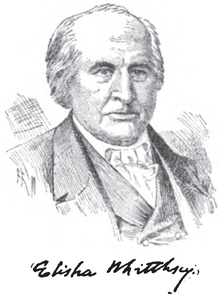

Watrous, and many of the Americans who came to the Lake Superior country at this time, were from northeastern Ohio. Watrous was able to obtain and keep his position as agent because his family was connected to Elisha Whittlesey.

In the summer and fall of 1851, Watrous was determined to get soldiers to help him force the removal. However, by that point, Washington was leaning toward letting the Lake Bands stay in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Last spring, during one of the several debt showdowns in Congress, I wrote on how similar antics in Washington contributed to the disaster of 1850. My earliest and best understanding of the 1850-1852 timeline, and the players involved, comes from this book:

We know that Kishkitauʋg (Cut Ear), and Oshoge (Heron) went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852. Benjamin Armstrong’s account is the most famous, but the delegation’s other interpreter, Vincent Roy Jr., also left his memories, which differ slightly in the details.

One of my first posts on the blog involved some Sandy Lake material in the Wheeler Family Papers, written by Sherman Hall. Since then, having seen many more of their letters, I would change some of the initial conclusions. However, I still see Hall as having committing a great sin of omission for not opposing the removal earlier. Even with the disclaimer, however, I have to give him credit for signing his name to the letter this post is about. Although they shared the common goal of destroying Ojibwe culture and religion and replacing it with American evangelical Protestantism, he A.B.C.F.M. mission community was made up of men and women with very different personalities. Their internal disputes were bizarre and fascinating.

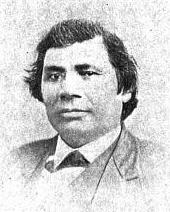

Oshogay

August 12, 2013

At the most recent count, Chief Buffalo is mentioned in over two-thirds of the posts here on Chequamegon History. That’s the most of anyone listed so far in the People Index. While there are more Buffalo posts on the way, I also want to draw attention to some of the lesser known leaders of the La Pointe Band. So, look for upcoming posts about Dagwagaane (Tagwagane), Mizay, Blackbird, Waabojiig, Andeg-wiiyas, and others. I want to start, however, with Oshogay, the young speaker who traveled to Washington with Buffalo in 1852 only to die the next year before the treaty he was seeking could be negotiated.

I debated whether to do this post, since I don’t know a lot about Oshogay. I don’t know for sure what his name means, so I don’t know how to spell or pronounce it correctly (in the sources you see Oshogay, O-sho-ga, Osh-a-ga, Oshaga, Ozhoge, etc.). In fact, I don’t even know how many people he is. There were at least four men with that name among the Lake Superior Ojibwe between 1800 and 1860, so much like with the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search, the key to getting Oshogay’s history right is dependent on separating his story from those who share his name.

In the end, I felt that challenge was worth a post in its own right, so here it is.

Getting Started

According to his gravestone, Oshogay was 51 when he died at La Pointe in 1853. That would put his birth around 1802. However, the Ojibwe did not track their birthdays in those days, so that should not be considered absolutely precise. He was considered a young man of the La Pointe Band at the time of his death. In my mind, the easiest way to sort out the information is going to be to lay it out chronologically. Here it goes:

1) Henry Schoolcraft, United States Indian Agent at Sault Ste. Marie, recorded the following on July 19, 1828:

Oshogay (the Osprey), solicited provisions to return home. This young man had been sent down to deliver a speech from his father, Kabamappa, of the river St. Croix, in which he regretted his inability to come in person. The father had first attracted my notice at the treaty of Prairie du Chien, and afterwards received a small medal, by my recommendation, from the Commissioners at Fond du Lac. He appeared to consider himself under obligations to renew the assurance of his friendship, and this, with the hope of receiving some presents, appeared to constitute the object of his son’s mission, who conducted himself with more modesty and timidity before me than prudence afterwards; for, by extending his visit to Drummond Island, where both he and his father were unknown, he got nothing, and forfeited the right to claim anything for himself on his return here.

I sent, however, in his charge, a present of goods of small amount, to be delivered to his father, who has not countenanced his foreign visit.

Oshogay is a “young man.” A birth year of 1802 would make him 26. He is part of Gaa-bimabi’s (Kabamappa’s) village in the upper St. Croix country.

2) In June of 1834, Edmund Ely and W. T. Boutwell, two missionaries, traveled from Fond du Lac (today’s Fond du Lac Reservation near Cloquet) down the St. Croix to Yellow Lake (near today’s Webster, WI) to meet with other missionaries. As they left Gaa-bimabi’s (Kabamappa’s) village near the head of the St. Croix and reached the Namekagon River on June 28th, they were looking for someone to guide them the rest of the way. An old Ojibwe man, who Boutwell had met before at La Pointe, and his son offered to help. The man fed the missionaries fish and hunted for them while they camped a full day at the mouth of the Namekagon since the 29th was a Sunday and they refused to travel on the Sabbath. On Monday the 30th, the reembarked, and Ely recorded in his journal:

The man, whose name is “Ozhoge,” and his son embarked with us about 1/2 past 9 °clk a.m. The old man in the bow and myself steering. We run the rapids safely. At half past one P. M. arrived at the mouth of Yellow River…

Ozhoge is an “old man” in 1834, so he couldn’t have been born in 1802. He is staying on the Namekagon River in the upper St. Croix country between Gaa-bimabi and the Yellow Lake Band. He had recently spent time at La Pointe.

3) Ely’s stay on the St. Croix that summer was brief. He was stationed at Fond du Lac until he eventually wore out his welcome there. In the 1840s, he would be stationed at Pokegama, lower on the St. Croix. During these years, he makes multiple references to a man named Ozhogens (a diminutive of Ozhoge). Ozhogens is always found above Yellow River on the upper St. Croix.

Ozhogens has a name that may imply someone older (possibly a father or other relative) lives nearby with the name Ozhoge. He seems to live in the upper St. Croix country. A birth year of 1802 would put him in his forties, which is plausible.

Ke-che-wask keenk (Gichi-weshki) is Chief Buffalo. Gab-im-ub-be (Gaa-bimabi) was the chief Schoolcraft identified as the father of Oshogay. Ja-che-go-onk was a son of Chief Buffalo.

4) On August 2, 1847, the United States and the Mississippi and Lake Superior Ojibwe concluded a treaty at Fond du Lac. The US Government wanted Ojibwe land along the nation’s border with the Dakota Sioux, so it could remove the Ho-Chunk people from Wisconsin to Minnesota.

Among the signatures, we find O-sho-gaz, a warrior from St. Croix. This would seem to be the Ozhogens we meet in Ely.

Here O-sho-gaz is clearly identified as being from St. Croix. His identification as a warrior would probably indicate that he is a relatively young man. The fact that his signature is squeezed in the middle of the names of members of the La Pointe Band may or may not be significant. The signatures on the 1847 Treaty are not officially grouped by band, but they tend to cluster as such.

5) In 1848 and 1849 George P. Warren operated the fur post at Chippewa Falls and kept a log that has been transcribed and digitized by the University of Wisconsin Eau Claire. He makes several transactions with a man named Oshogay, and at one point seems to have him employed in his business. His age isn’t indicated, but the amount of furs he brings in suggests that he is the head of a small band or large family. There were multiple Ojibwe villages on the Chippewa River at that time, including at Rice Lake and Lake Shatac (Chetek). The United States Government treated with them as satellite villages of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band.

Based on where he lives, this Oshogay might not be the same person as the one described above.

6) In December 1850, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in the case Oshoga vs. The State of Wisconsin, that there were a number of irregularities in the trial that convicted “Oshoga, an Indian of the Chippewa Nation” of murder. The court reversed the decision of the St. Croix County circuit court. I’ve found surprisingly little about this case, though that part of Wisconsin was growing very violent in the 1840s as white lumbermen and liquor salesmen were flooding the country.

Pg 56 of Containing cases decided from the December term, 1850, until the organization of the separate Supreme Court in 1853: Volume 3 of Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Wisconsin: With Tables of the Cases and Principal Matters, and the Rules of the Several Courts in Force Since 1838, Wisconsin. Supreme Court Authors: Wisconsin. Supreme Court, Silas Uriah Pinney (Google Books).

The man killed, Alexander Livingston, was a liquor dealer himself.

Alexander Livingston, a man who in youth had had excellent advantages, became himself a dealer in whisky, at the mouth of Wolf creek, in a drunken melee in his own store was shot and killed by Robido, a half-breed. Robido was arrested but managed to escape justice.

~From Fifty Years in the Northwest by W.H.C Folsom

Several pages later, Folsom writes:

At the mouth of Wolf creek, in the extreme northwestern section of this town, J. R. Brown had a trading house in the ’30s, and Louis Roberts in the ’40s. At this place Alex. Livingston, another trader, was killed by Indians in 1849. Livingston had built him a comfortable home, which he made a stopping place for the weary traveler, whom he fed on wild rice, maple sugar, venison, bear meat, muskrats, wild fowl and flour bread, all decently prepared by his Indian wife. Mr. Livingston was killed by an Indian in 1849.

Folsom makes no mention of Oshoga, and I haven’t found anything else on what happened to him or Robido (Robideaux?).

It’s hard to say if this Oshoga is the Ozhogen’s of Ely’s journals or the Oshogay of Warren’s. Wolf Creek is on the St. Croix, but it’s not far from the Chippewa River country either, and the Oshogay of Warren seems to have covered a lot of ground in the fur trade. Warren’s journal, linked in #4, contains a similar story of a killing and “frontier justice” leading to lynch mobs against the Ojibwe. To escape the violence and overcrowding, many Ojibwe from that part of the country started to relocate to Fond du Lac, Lac Courte Oreilles, or La Pointe/Bad River. La Pointe is also where we find the next mention of Oshogay.

7) From 1851 to 1853, a new voice emerged loudly from the La Pointe Band in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. It was that of Buffalo’s speaker Oshogay (or O-sho-ga), and he spoke out strongly against Indian Agent John Watrous’ handling of the Sandy Lake payments (see this post) and against Watrous’ continued demands for removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. There are a number of documents with Oshogay’s name on them, and I won’t mention all of them, but I recommend Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren and Howard Paap’s Red Cliff, Wisconsin as two places to get started.

Chief Buffalo was known as a great speaker, but he was nearing the end of his life, and it was the younger chief who was speaking on behalf of the band more and more. Oshogay represented Buffalo in St. Paul, co-wrote a number of letters with him, and most famously, did most of the talking when the two chiefs went to Washington D.C. in the spring of 1852 (at least according to Benjamin Armstrong’s memoir). A number of secondary sources suggest that Oshogay was Buffalo’s son or son-in-law, but I’ve yet to see these claims backed up with an original document. However, all the documents that identify by band, say this Oshogay was from La Pointe.

The Wisconsin Historical Society has digitized four petitions drafted in the fall of 1851 and winter of 1852. The petitions are from several chiefs, mostly of the La Pointe and Lac Courte Oreilles/Chippewa River bands, calling for the removal of John Watrous as Indian Agent. The content of the petitions deserves its own post, so for now we’ll only look at the signatures.

November 6, 1851 Letter from 30 chiefs and headmen to Luke Lea, Commissioner of Indian Affairs: Multiple villages are represented here, roughly grouped by band. Kijiueshki (Buffalo), Jejigwaig (Buffalo’s son), Kishhitauag (“Cut Ear” also associated with the Ontonagon Band), Misai (“Lawyerfish”), Oshkinaue (“Youth”), Aitauigizhik (“Each Side of the Sky”), Medueguon, and Makudeuakuat (“Black Cloud”) are all known members of the La Pointe Band. Before the 1850s, Kabemabe (Gaa-bimabi) and Ozhoge were associated with the villages of the Upper St. Croix.

November 8, 1851, Letter from the Chiefs and Headmen of Chippeway River, Lac Coutereille, Puk-wa-none, Long Lake, and Lac Shatac to Alexander Ramsey, Superintendent of Indian Affairs: This letter was written from Sandy Lake two days after the one above it was written from La Pointe. O-sho-gay the warrior from Lac Shatac (Lake Chetek) can’t be the same person as Ozhoge the chief unless he had some kind of airplane or helicopter back in 1851.

Undated (Jan. 1852?) petition to “Our Great Father”: This Oshoga is clearly the one from Lake Chetek (Chippewa River).

Undated (Jan. 1852?) petition: These men are all associated with the La Pointe Band. Osho-gay is their Speaker.

In the early 1850s, we clearly have two different men named Oshogay involved in the politics of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. One is a young warrior from the Chippewa River country, and the other is a rising leader among the La Pointe Band.

Washington Delegation July 22, 1852 This engraving of the 1852 delegation led by Buffalo and Oshogay appeared in Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians. Look for an upcoming post dedicated to this image.

8) In the winter of 1853-1854, a smallpox epidemic ripped through La Pointe and claimed the lives of a number of its residents including that of Oshogay. It had appeared that Buffalo was grooming him to take over leadership of the La Pointe Band, but his tragic death left a leadership vacuum after the establishment of reservations and the death of Buffalo in 1855.

Oshogay’s death is marked in a number of sources including the gravestone at the top of this post. The following account comes from Richard E. Morse, an observer of the 1855 annuity payments at La Pointe:

The Chippewas, during the past few years, have suffered extensively, and many of them died, with the small pox. Chief O-SHO-GA died of this disease in 1854. The Agent caused a suitable tomb-stone to be erected at his grave, in La Pointe. He was a young chief, of rare promise and merit; he also stood high in the affections of his people.

Later, Morse records a speech by Ja-be-ge-zhick or “Hole in the Sky,” a young Ojibwe man from the Bad River Mission who had converted to Christianity and dressed in “American style.” Jabegezhick speaks out strongly to the American officials against the assembled chiefs:

…I am glad you have seen us, and have seen the folly of our chiefs; it may give you a general idea of their transactions. By the papers you have made out for the chiefs to sign, you can judge of their ability to do business for us. We had but one man among us, capable of doing business for the Chippewa nation; that man was O-SHO-GA, now dead and our nation now mourns. (O-SHO-GA was a young chief of great merit and much promise; he died of small-pox, February 1854). Since his death, we have lost all our faith in the balance of our chiefs…

This O-sho-ga is the young chief, associated with the La Pointe Band, who went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852.

9) In 1878, “Old Oshaga” received three dollars for a lynx bounty in Chippewa County.

Report of the Wisconsin Office of the Secretary of State, 1878; pg. 94 (Google Books)

It seems quite possible that Old Oshaga is the young man that worked with George Warren in the 1840s and the warrior from Lake Chetek who signed the petitions against Agent Watrous in the 1850s.

10) In 1880, a delegation of Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, and Lac du Flambeau chiefs visited Washington D.C. I will get into their purpose in a future post, but for now, I will mention that the chiefs were older men who would have been around in the 1840s and ’50s. One of them is named Oshogay. The challenge is figuring out which one.

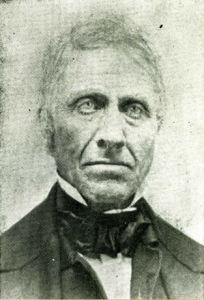

Ojibwe Delegation c. 1880 by Charles M. Bell. [Identifying information from the Smithsonian] Studio portrait of Anishinaabe Delegation posed in front of a backdrop. Sitting, left to right: Edawigijig; Kis-ki-ta-wag; Wadwaiasoug (on floor); Akewainzee (center); Oshawashkogijig; Nijogijig; Oshoga. Back row (order unknown); Wasigwanabi; Ogimagijig; and four unidentified men (possibly Frank Briggs, top center, and Benjamin Green Armstrong, top right). The men wear European-style suit jackets and pants; one man wears a peace medal, some wear beaded sashes or bags or hold pipes and other props.(Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian).

- Upper row reading from the left.

- 1. Vincent Conyer- Interpreter 1,2,4,5 ?, includes Wasigwanabi and Ogimagijig

- 2. Vincent Roy Jr.

- 3. Dr. I. L. Mahan, Indian Agent Frank Briggs

- 4. No Name Given

- 5. Geo P. Warren (Born at LaPointe- civil war vet.

- 6. Thad Thayer Benjamin Armstrong

- Lower row

- 1. Messenger Edawigijig

- 2. Na-ga-nab (head chief of all Chippewas) Kis-ki-ta-wag

- 3. Moses White, father of Jim White Waswaisoug

- 4. No Name Given Akewainzee

- 5. Osho’gay- head speaker Oshawashkogijig or Oshoga

- 6. Bay’-qua-as’ (head chief of La Corrd Oreilles, 7 ft. tall) Nijogijig or Oshawashkogijig

- 7. No name given Oshoga or Nijogijig

The Smithsonian lists Oshoga last, so that would mean he is the man sitting in the chair at the far right. However, it doesn’t specify who the man seated on the right on the floor is, so it’s also possible that he’s their Oshoga. If the latter is true, that’s also who the unknown writer of the library caption identified as Osho’gay. Whoever he is in the picture, it seems very possible that this is the same man as “Old Oshaga” from number 9.

11) There is one more document I’d like to include, although it doesn’t mention any of the people we’ve discussed so far, it may be of interest to someone reading this post. It mentions a man named Oshogay who was born before 1860 (albeit not long before).

For decades after 1854, many of the Lake Superior Ojibwe continued to live off of the reservations created in the Treaty of La Pointe. This was especially true in the St. Croix region where no reservation was created at all. In the 1910s, the Government set out to document where various Ojibwe families were living and what tribal rights they had. This process led to the creation of the St. Croix and Mole Lake reservations. In 1915, we find 64-year-old Oshogay and his family living in Randall, Wisconsin which may suggest a connection to the St. Croix Oshogays. As with number 6 above, this creates some ambiguity because he is listed as enrolled at Lac Courte Oreilles, which implies a connection to the Chippewa River Oshogay. For now, I leave this investigation up to someone else, but I’ll leave it here for interest.

United States. Congress. House. Committee on Indian Affairs. Indian Appropriation Bill: Supplemental Hearings Before a Subcommittee. 1919 (Google Books).

This is not any of the Oshogays discussed so far, but it could be a relative of any or all of them.

In the final analysis

These eleven documents mention at least four men named Oshogay living in northern Wisconsin between 1800 and 1860. Edmund Ely met an old man named Oshogay in 1834. He is one. A 64-year old man, a child in the 1850s, was listed on the roster of “St. Croix Indians.” He is another. I believe the warrior from Lake Chetek who traded with George Warren in the 1840s could be one of the chiefs who went to Washington in 1880. He may also be the one who was falsely accused of killing Alexander Livingston. Of these three men, none are the Oshogay who went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852.

That leaves us with the last mystery. Is Ozhogens, the young son of the St. Croix chief Gaa-bimabi, the orator from La Pointe who played such a prominent role in the politics of the early 1850s? I don’t have a smoking gun, but I feel the circumstantial evidence strongly suggests he is. If that’s the case, it explains why those who’ve looked for his early history in the La Pointe Band have come up empty.

However, important questions remain unanswered. What was his connection to Buffalo? If he was from St. Croix, how was he able to gain such a prominent role in the La Pointe Band, and why did he relocate to La Pointe anyway? I have my suspicions for each of these questions, but no solid evidence. If you do, please let me know, and we’ll continue to shed light on this underappreciated Ojibwe leader.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892. Print.

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Folsom, William H. C., and E. E. Edwards. Fifty Years in the Northwest. St. Paul: Pioneer, 1888. Print.

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 12 August 2013. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1995. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Redix, Erik M. “The Murder of Joe White: Ojibwe Leadership and Colonialism in Wisconsin.” Diss. University of Minnesota, 2012. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. The Voice of the Crane Echoes Afar: The Sociopolitical Organization of the Lake Superior Ojibwa, 1640-1855. New York: Garland Pub., 1997. Print.

———–William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers: With Brief Notices of Passing Events, Facts, and Opinions, A.D. 1812 to A.D. 1842. Philadelphia, [Pa.: Lippincott, Grambo and, 1851. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.