Photos, Photos, Photos

February 10, 2014

The queue of Chequamegon History posts that need to be written grows much faster than my ability to write them. Lately, I’ve been backed up with mysteries surrounding a number of photographs. Many of these photos are from after 1860, so they are technically outside the scope of this website (though they involve people who were important in the pre-1860 era too.

Photograph posts are some of the hardest to write, so I decided to just run through all of them together with minimal commentary other than that needed to resolve the unanswered questions. I will link all the photos back to their sources where their full descriptions can be found. Here it goes, stream-of-consciousness style:

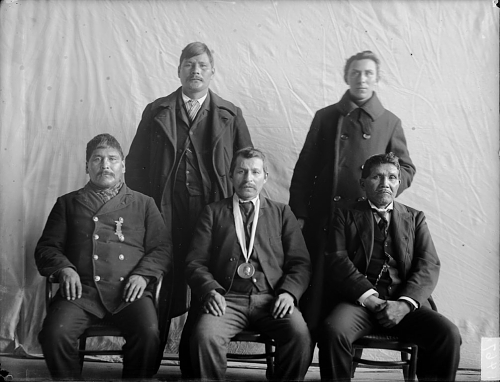

Ojibwa Delegation by C.M. Bell. Washington D.C. 1880 (NMAI Collections)

This whole topic started with a photo of a delegation of Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs that sits on the windowsill of the Bayfield Public Library. Even though it is clearly after 1860, some of the names in the caption: Oshogay, George Warren, and Vincent Roy Jr. caught my attention. These men, looking past their prime, were all involved in the politics of the 1850s that I had been studying, so I wanted to find out more about the picture.

As I mentioned in the Oshogay post, this photo is also part of the digital collections of the Smithsonian, but the people are identified by different names. According to the Smithsonian, the picture was taken in Washington in 1880 by the photographer C.M. Bell.

I found a second version of this photo as well. If it wasn’t for one of the chiefs in front, you’d think it was the same picture:

While my heart wanted to believe the person, probably in the early 20th century, who labelled the Bayfield photograph, my head told me the photographer probably wouldn’t have known anything about the people of Lake Superior, and therefore could only have gotten the chiefs’ names directly from them. Plus, Bell took individual photos:

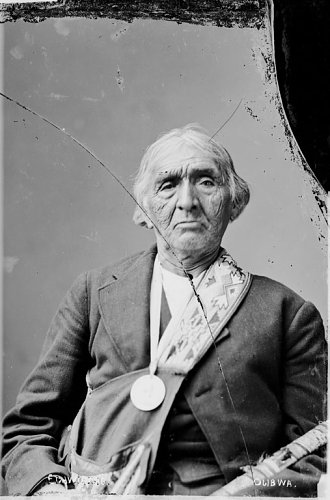

Edawigijig (Edawi-giizhig “Both Sides of the Sky”), Bad River chief and signer of the Treaty of 1854 (C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections)

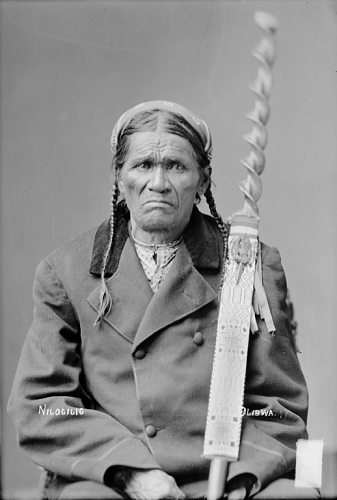

Niizhogiizhig: “Second Day,” (C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections)

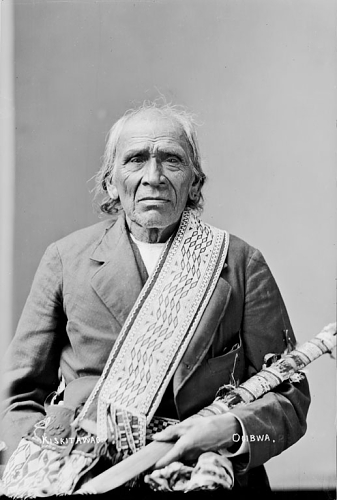

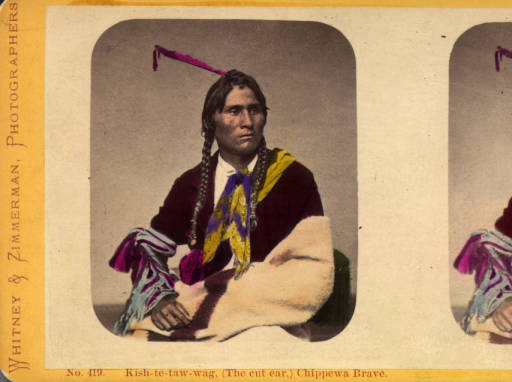

Kiskitawag (Giishkitawag: “Cut Ear”) signed multiple treaties as a warrior of the Ontonagon Band but afterwards was associated with the Bad River Band (C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections).

By cross-referencing the individual photos with the names listed with the group photo, you can identify nine of the thirteen men. They are chiefs from Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, and Lac du Flambeau.

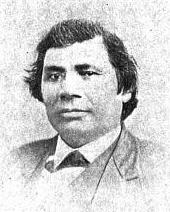

According to this, the man identified by the library caption as Vincent Roy Jr., was in fact Ogimaagiizhig (Sky Chief). He does have a resemblance to Roy, so I’ll forgive whoever it was, even if it means having to go back and correct my Vincent Roy post:

According to this, the man identified by the library caption as Vincent Roy Jr., was in fact Ogimaagiizhig (Sky Chief). He does have a resemblance to Roy, so I’ll forgive whoever it was, even if it means having to go back and correct my Vincent Roy post:

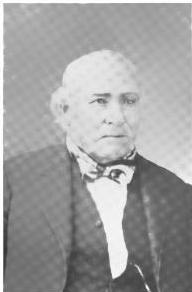

Vincent Roy Jr. From C. Verwyst’s Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, First Bishop of Marquette, Mich: To which are Added Short Sketches of the Lives and Labors of Other Indian Missionaries of the Northwest (Digitized by Google Books)

Top: Frank Roy, Vincent Roy, E. Roussin, Old Frank D.o., Bottom: Peter Roy, Jos. Gourneau (Gurnoe), D. Geo. Morrison. The photo is labelled Chippewa Treaty in Washington 1845 by the St. Louis Hist. Lib and Douglas County Museum, but if it is in fact in Washington, it was probably the Bois Forte Treaty of 1866, where these men acted as conductors and interpreters (Digitized by Mary E. Carlson for The Sawmill Community at Roy’s Point).

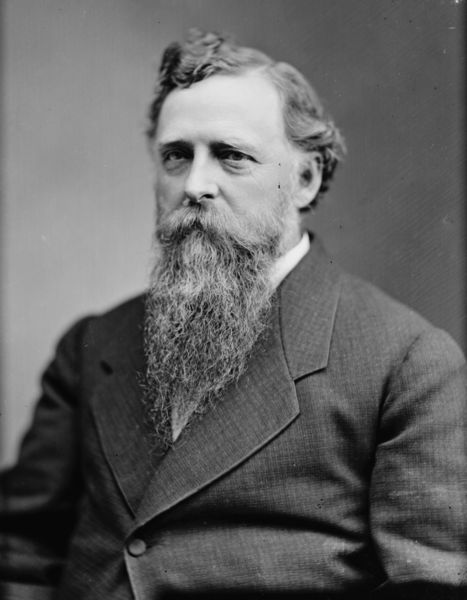

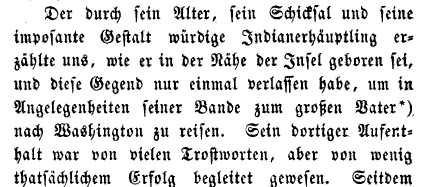

So now that we know who went on the 1880 trip, it begs the question of why they went. The records I’ve found haven’t been overly clear, but it appears that it involved a bill in the senate for “severalty” of the Ojibwe reservations in Wisconsin. A precursor to the 1888 Allotment Act of Senator Henry Dawes, this legislation was proposed by Senator Thaddeus C. Pound of Wisconsin. It would divide the reservations into parcels for individual families and sell the remaining lands to the government, thereby greatly reducing the size of the reservations and opening the lands up for logging.

Pound spent a lot of time on Indian issues and while he isn’t as well known as Dawes or as Richard Henry Pratt the founder of the Carlisle Indian School, he probably should be. Pound was a friend of Pratt’s and an early advocate of boarding schools as a way to destroy Native cultures as a way to uplift Native peoples.

I’m sure that Pound’s legislation was all written solely with the welfare of the Ojibwe in mind, and it had nothing to do with the fact that he was a wealthy lumber baron from Chippewa Falls who was advocating damming the Chippewa River (and flooding Lac Courte Oreilles decades before it actually happened). All sarcasm aside, if any American Indian Studies students need a thesis topic, or if any L.C.O. band members need a new dartboard cover, I highly recommend targeting Senator Pound.

Like many self-proclaimed “Friends of the Indian” in the 1880s, Senator Thaddeus C. Pound of Wisconsin thought the government should be friendly to Indians by taking away more of their land and culture. That he stood to make a boatload of money out of it was just a bonus (Brady & Handy: Wikimedia Commons).

While we know Pound’s motivations, it doesn’t explain why the chiefs came to Washington. According to the Indian Agent at Bayfield they were brought in to support the legislation. We also know they toured Carlisle and visited the Ojibwe students there. There are a number of potential explanations, but without having the chiefs’ side of the story, I hesitate to speculate. However, it does explain the photograph.

Now, let’s look at what a couple of these men looked like two decades earlier:

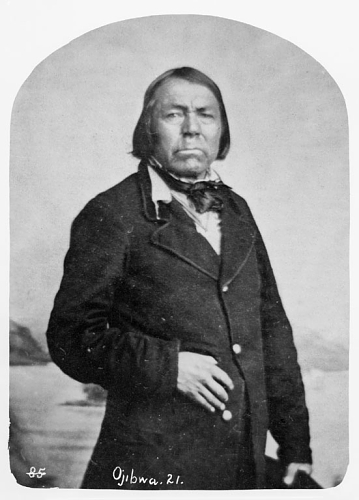

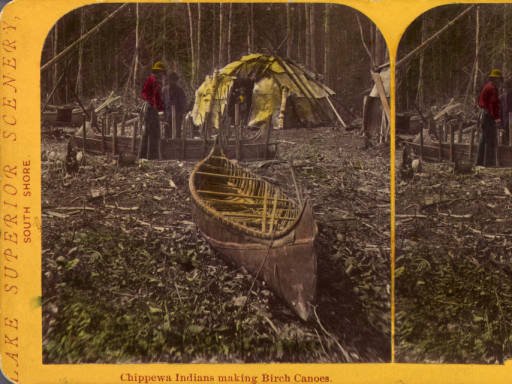

This stereocard of Giishkitawag was produced in the early 1870s, but the original photo was probably taken in the early 1860s (Denver Public Library).

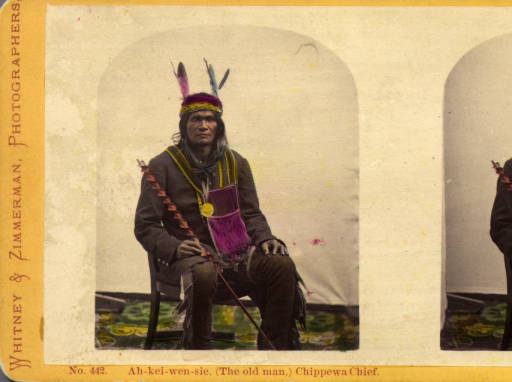

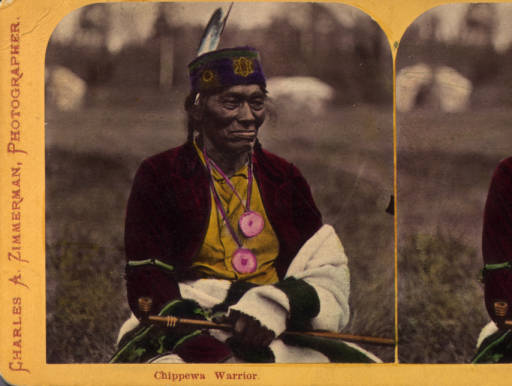

By the mid 1850s, Akiwenzii (Old Man) was the most prominent chief of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band. This stereocard was made by Whitney and Zimmerman c.1870 from an original possibly by James E. Martin in the late 1850s or early 1860s (Denver Public Library).

Giishkitawag and Akiwenzii are seem to have aged quite a bit between the early 1860s, when these photos were taken, and 1880 but they are still easily recognized. The earlier photos were taken in St. Paul by the photographers Joel E. Whitney and James E. Martin. Their galleries, especially after Whitney partnered with Charles Zimmerman, produced hundreds of these images on cards and stereoviews for an American public anxious to see real images of Indian leaders.

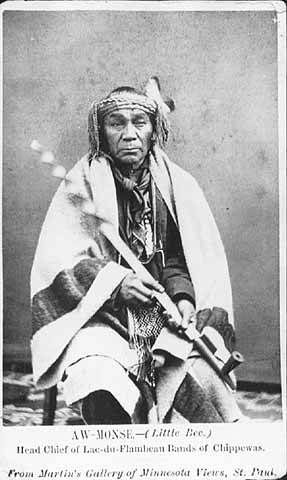

Giishkitawag and Akiwenzii were not the only Lake Superior chiefs to end up on these souvenirs. Aamoons (Little Bee), of Lac du Flambeau appears to have been a popular subject:

Aamoons (Little Bee) was a prominent chief from Lac du Flambeau (Denver Public Library).

As the images were reproduced throughout the 1870s, it appears the studios stopped caring who the photos were actually depicting:

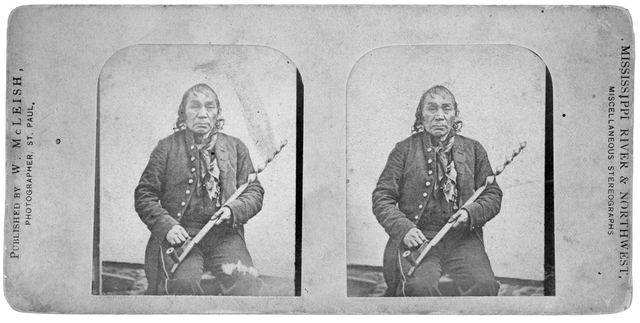

One wonders what the greater insult to Aamoons was: reducing him to being simply “Chippewa Brave” as Whitney and Zimmerman did here, or completely misidentifying him as Na-gun-ub (Naaganab) as a later stereo reproduction as W. M. McLeish does here:

Chief identified as Na-gun-ub (Minnesota Historical Society)

Aamoons and Naaganab don’t even look alike…

Naaganab (Minnesota Historical Society)

…but the Lac du Flambeau and Fond du Lac chiefs were probably photographed in St. Paul around the time they were both part of a delegation to President Lincoln in 1862.

Chippewa Delegation 1862 by Matthew Brady? (Minnesota Historical Society)

Naaganab (seated middle) and Aamoons (back row, second from left) are pretty easy to spot, and if you look closely, you’ll see Giishkitawag, Akiwenzii, and a younger Edawi-giizhig (4th, 5th, and 6th from left, back row) were there too. I can’t find individual photos of the other chiefs, but there is a place we can find their names.

Benjamin Armstrong, who interpreted for the delegation, included a version of the image in his memoir Early Life Among the Indians. He identifies the men who went with him as:

Ah-moose (Little Bee) from Lac Flambeau Reservation, Kish-ke-taw-ug (Cut Ear) from Bad River Reservation, Ba-quas (He Sews) from Lac Courte O’Rielles Reservation, Ah-do-ga-zik (Last Day) from Bad River Reservation, O-be-quot (Firm) from Fond du Lac Reservation, Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation, Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell) from La Pointe Reservation, Na-gon-ab (He Sits Ahead) from Fond du Lac Reservation, and O-ma-shin-a-way (Messenger) from Bad River Reservation.

It appears that Armstrong listed the men according to their order in the photograph. He identifies Akiwenzii as “Ba-quas (He Sews),” which until I find otherwise, I’m going to assume the chief had two names (a common occurrence) since the village is the same. Aamoons, Giishkitawag, Edawi-giizhig and Naaganab are all in the photograph in the places corresponding to the order in Armstrong’s list. That means we can identify the other men in the photo.

I don’t know anything about O-be-quot from Fond du Lac (who appears to have been moved in the engraving) or S[h]ing-guak-onse from Red Cliff (who is cut out of the photo entirely) other than the fact that the latter shares a name with a famous 19th-century Sault Ste. Marie chief. Travis Armstrong’s outstanding website, chiefbuffalo.com, has more information on these chiefs and the mission of the delegation.

Seated to the right of Naaganab, in front of Edawi-giizhig is Omizhinawe, the brother of and speaker for Blackbird of Bad River. Finally, the broad-shouldered chief on the bottom left is “Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell)” from Red Cliff. This is Jajigwyong, the son of Chief Buffalo, who signed the treaties as a chief in his own right. Jayjigwyong, sometimes called Little Chief Buffalo, was known for being an early convert to Catholicism and for encouraging his followers to dress in European style. Indeed, we see him and the rest of the chiefs dressed in buttoned coats and bow-ties and wearing their Lincoln medals.

Wait a minute… button coats?… bow-ties?… medals?…. a chief identified as Buffalo…That reminds me of…

This image is generally identified as Chief Buffalo (Wikimedia Commons)

Anyway, with that mystery solved, we can move on to the next one. It concerns a photograph that is well-known to any student of Chequamegon-area history in the mid 19th century (or any Chequamegon History reader who looks at the banners on the side of this page).Noooooo!!!!!!! I’ve been trying to identify the person in The above “Chief Buffalo” photo for years, and the answer was in Armstrong all along! Now I need to revise this post among others. I had already begun to suspect it was Jayjigwyong rather than his father, but my evidence was circumstantial. This leaves me without a doubt. This picture of the younger Chief Buffalo, not his more-famous father.

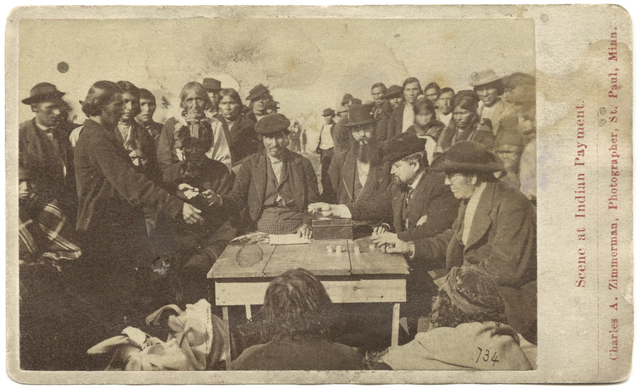

The photo showing an annuity payment, must have been widely distributed in its day, because it has made it’s way into various formats in archives and historical societies around the world. It has also been reproduced in several secondary works including Ronald Satz’ Chippewa Treaty Rights, Patty Loew’s Indian Nations of Wisconsin, Hamilton Ross’ La Pointe: Village Outpost on Madeline Island, and in numerous other pamphlets, videos, and displays in the Chequamegon Region. However, few seem to agree on the basic facts:

When was it taken?

Where was it taken?

Who was the photographer?

Who are the people in the photograph?

We’ll start with a cropped version that seems to be the most popular in reproductions:

According to Hamilton Ross and the Wisconsin Historical Society: “Annuity Payment at La Pointe: Indians receiving payment. Seated on the right is John W. Bell. Others are, left to right, Asaph Whittlesey, Agent Henry C. Gilbert, and William S. Warren (son of Truman Warren).” 1870. Photographer Charles Zimmerman (more info).

In the next one, we see a wider version of the image turned into a souvenir card much like the ones of the chiefs further up the post:

According to the Minnesota Historical Society “Scene at Indian payment, Wisconsin; man in black hat, lower right, is identified as Richard Bardon, Superior, Wisconsin, then acting Indian school teacher and farmer” c.1871 by Charles Zimmerman (more info).

In this version, we can see more foreground and the backs of the two men sitting in front.

According to the Library of Congress: “Cherokee payments(?). Several men seated around table counting coins; large group of Native Americans stand in background.” Published 1870-1900 (more info).

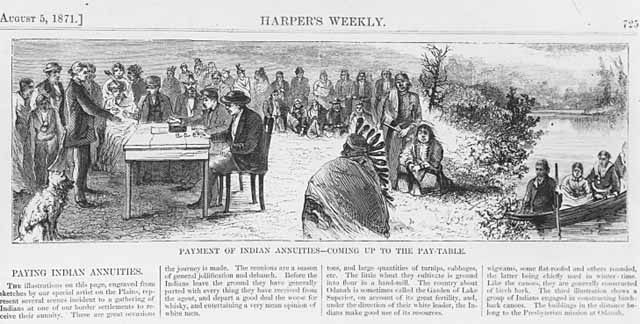

The image also exists in engraved forms, both slightly modified…

According to Benjamin Armstrong: “Annuity papment [sic] at La Pointe 1852” (From Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians)

…and greatly-modified.

Harper’s Weekly August 5, 1871: “Payment of Indian Annuities–Coming up to the Pay Table.” (more info)

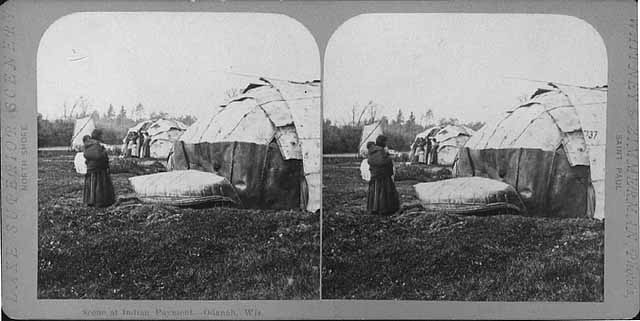

It should also be mentioned that another image exists that was clearly taken on the same day. We see many of the same faces in the crowd:

Scene at Indian payment, probably at Odanah, Wisconsin. c.1865 by Charles Zimmerman (more info)

We have a lot of conflicting information here. If we exclude the Library of Congress Cherokee reference, we can be pretty sure that this is an annuity payment at La Pointe or Odanah, which means it was to the Lake Superior Ojibwe. However, we have dates ranging from as early as 1852 up to 1900. These payments took place, interrupted from 1850-1852 by the Sandy Lake Removal, from 1837 to 1874.

Although he would have attended a number of these payments, Benjamin Armstrong’s date of 1852, is too early. A number of secondary sources have connected this photo to dates in the early 1850s, but outside of Armstrong, there is no evidence to support it.

Charles Zimmerman, who is credited as the photographer when someone is credited, became active in St. Paul in the late 1860s, which would point to the 1870-71 dates as more likely. However, if you scroll up the page and look at Giishkitaawag, Akiwenzii, and Aamoons again, you’ll see that these photos, (taken in the early 1860s) are credited to “Whitney & Zimmerman,” even though they predate Zimmerman’s career.

What happened was that Zimmerman partnered with Joel Whitney around 1870, eventually taking over the business, and inherited all Whitney’s negatives (and apparently those of James Martin as well). There must have been an increase in demand for images of Indian peoples in the 1870s, because Zimmerman re-released many of the earlier Whitney images.

So, we’re left with a question. Did Zimmerman take the photograph of the annuity payment around 1870, or did he simply reproduce a Whitney negative from a decade earlier?

I had a hard time finding any primary information that would point to an answer. However, the Summer 1990 edition of the Minnesota History magazine includes an article by Bonnie G. Wilson called Working the Light: Nineteenth Century Professional Photographers in Minnesota. In this article, we find the following:

“…Zimmerman was not a stay-at-home artist. He took some of his era’s finest landscape photos of Minnesota, specializing in stereographs of the Twin Cities area, but also traveling to Odanah, Wisconsin for an Indian annuity payment…”

In the footnotes, Wilson writes:

“The MHS has ten views in the Odanah series, which were used as a basis for engravings in Harper’s Weekly, Aug. 5, 1871. See also Winona Republican, Oct. 12, 1869 p.3;”

Not having access to the Winona Republican, I tried to see how many of the “Odanah series” I could track down. Zimmerman must have sold a lot of stereocards, because this task was surprisingly easy. Not all are labelled as being in Odanah, but the backgrounds are similar enough to suggest they were all taken in the same place. Click on them to view enlarged versions at various digital archives.

Scene at Indian Payment, Odanah Wisconsin (Minnesota Historical Society)

Chippewa Wedding (British Museum)

Domestic Life–Chippewa Indians (British Museum)

Chippewa Wedding (British Museum)

Finally…

So, if Zimmerman took the “Odanah series” in 1869, and the pay table image is part of it, then this is a picture of the 1869 payment. To be absolutely certain, we should try to identify the men in the image.

This task is easier than ever because the New York Public Library has uploaded a high-resolution scan of the Whitney & Zimmerman stereocard version to Wikimedia Commons. For the first time, we can really get a close look at the men and women in this photo.

They say a picture tells a thousand words. I’m thinking I could write ten-thousand and still not say as much as the faces in this picture.

To try to date the photo, I decided to concentrate the six most conspicuous men in the photo:

1) The chief in the fur cap whose face in the shadows.

2) The gray-haired man standing behind him.

3) The man sitting behind the table who is handing over a payment.

4) The man with the long beard, cigar, and top hat.

5) The man with the goatee looking down at the money sitting to the left of the top-hat guy (to the right in our view)

6) The man with glasses sitting at the table nearest the photographer

According to Hamilton Ross, #3 is Asaph Whittlesey, #4 is Agent Henry Gilbert, #5 is William S. Warren (son of Truman), and #6 is John W. Bell. While all four of those men could have been found at annuity payments as various points between 1850 and 1870, this appears to be a total guess by Ross. Three of the four men appear to be of at least partial Native descent and only one (Warren) of those identified by Ross was Ojibwe. Chronologically, it doesn’t add up either. Those four wouldn’t have been at the same table at the same time. Additionally, we can cross-reference two of them with other photos.

Asaph Whittlesey was an interesting looking dude, but he’s not in the Zimmerman photo (Wisconsin Historical Society).

Henry C. Gilbert was the Indian Agent during the Treaty of 1854 and oversaw the 1855 annuity payment, but he was dead by the time the “Zimmerman” photo was taken (Branch County Photographs)

Whittlesey and Gilbert are not in the photograph.

The man who I label as #5 is identified by Ross as William S. Warren. This seems like a reasonable guess, though considering the others, I don’t know that it’s based on any evidence. Warren, who shares a first name with his famous uncle William Whipple Warren, worked as a missionary in this area.

The man I label #6 is called John W. Bell by Ross and Richard Bardon by the Minnesota Historical Society. I highly doubt either of these. I haven’t found photos of either to confirm, but the Ireland-born Bardon and the Montreal-born Bell were both white men. Mr. 6 appears to be Native. I did briefly consider Bell as a suspect for #4, though.

Neither Ross nor the Minnesota Historical Society speculated on #1 or #2.

At this point, I cannot positively identify Mssrs. 1, 2, 3, 5, or 6. I have suspicions about each, but I am not skilled at matching faces, so these are wild guesses at this point:

#1 is too covered in shadows for a clear identification. However, the fact that he is wearing the traditional fur headwrap of an Ojibwe civil chief, along with a warrior’s feather, indicates that he is one of the traditional chiefs, probably from Bad River but possibly from Lac Courte Oreilles or Lac du Flambeau. I can’t see his face well enough to say whether or not he’s in one of the delegation photos from the top of the post.

#2 could be Edawi-giizhig (see above), but I can’t be certain.

#3 is also tricky. When I started to examine this photo, one of the faces I was looking for was that of Joseph Gurnoe of Red Cliff. You can see him in a picture toward the top of the post with the Roy brothers. Gurnoe was very active with the Indian Agency in Bayfield as a clerk, interpreter, and in other positions. Comparing the two photos I can’t say whether or not that’s him. Leave a comment if you think you know.

#5 could be a number of different people.

#6 I don’t have a solid guess on either. His apparent age, and the fact that the Minnesota Historical Society’s guess was a government farmer and schoolteacher, makes me wonder about Henry Blatchford. Blatchford took over the Odanah Mission and farm from Leonard Wheeler in the 1860s. This was after spending decades as Rev. Sherman Hall’s interpreter, and as a teacher and missionary in La Pointe and Odanah area. When this photo was taken, Blatchford had nearly four decades of experience as an interpreter for the Government. I don’t have any proof that it’s him, but he is someone who is easy to imagine having a place at the pay table.

Finally, I’ll backtrack to #4, whose clearly identifiable gray-streaked beard allows us to firmly date the photo. The man is Col. John H. Knight, who came to Bayfield as Indian Agent in 1869.

Col. John H. Knight (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Knight oversaw a couple of annuity payments, but considering the other evidence, I’m confident that the popular image that decorates the sides of the Chequamegon History site was indeed taken at Odanah by Charles Zimmerman at the 1869 annuity payment.

Do you agree? Do you disagree? Have you spotted anything in any of these photos that begs for more investigation? Leave a comment.

As for myself, it’s a relief to finally get all these photo mysteries out of my post backlog. The 1870 date on the Zimmerman photo reminds me that I’m spending too much time in the later 19th century. After all, the subtitle of this website says it’s history before 1860. I think it might be time to go back for a while to the days of the old North West Company or maybe even to Pontiac. Stay tuned, and thanks for reading,

Blackbird’s Speech at the 1855 Payment

January 20, 2014

“We sold our land for our graves–that we might have a home, where the bones of our fathers are buried. We were not willing to sell the ashes of our relatives which are so dear to us. This was the reason why we sold our lands. It was not to pay debts over and over again, but to benefit the living, those of us who yet remain upon earth, our young men & women & children.”

~Makade-binesi (Blackbird)

Scene at Indian Payment–Odanah, Wis. This image is from a later payment than the one described below (Whitney & Zimmerman c.1870)

Most of us have heard Chief Joseph’s “Fight No More Forever” speech and Chief Seattle’s largely-fictional plea for the environment, but very few will know that a outstanding example of Native American oratory took place right here in the Chequamegon Region in the summer of 1855.

It was exactly eleven months after the Lake Superior Ojibwe bands gave up the Arrowhead region of Minnesota, in their final treaty with the United States, in exchange for permanent reservations. Already, the American government was trying to back out of a key provision of the agreement. It concerned a clause in Article Four of the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe that reads:

The United States will also pay the further sum of ninety thousand dollars, as the chiefs in open council may direct, to enable them to meet their present just engagements.

The inclusion of clauses to pay off trade debts was nothing new in Ojibwe treaties. In 1837, $70,000 went to pay off debts, and in 1842 another $75,000 went to the traders. Personal debts would often be paid out of annuity funds by the government directly to the creditors and certain Ojibwe families would never see their money. However, from the beginning there were accusations that these debts were inflated or illegitimate, and that it was the traders rather than the Ojibwe themselves, who profited from the sale of the lands. Therefore, in 1854, when $90,000 in claims were inserted in the treaty, the chiefs demanded that they be the ones to address the claims of the creditors.

However, less than a year later, at the first post-1854 payment, the government was pressured to back off of the language in the treaty. George Manypenny, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, came to La Pointe to oversee the payment where he was asked by Indian Agent Henry Gilbert to let the Agency oversee the disbursement of the $90,000. Most white inhabitants, and many of the white tourists in town to view the spectacle that was the 1855 payment, supported the agent’s plan, as did most of the mix-blooded Ojibwe (most of whom were employed in the trading business in one way or another) and a substantial minority of the full-bloods.

However, the clear majority of the Lake Superior chiefs insisted they keep the right to handle their own debt claims. As we saw in this post, the Odanah-based missionary Leonard Wheeler also felt the Government needed to honor its treaties to the letter. This larger faction of Ojibwe rallied around one chief. He was from the La Pointe Band and was entrusted to speak for Ojibwe with one voice. From this description, you might assume it was Chief Buffalo. However, Buffalo, in the final days of his life, found himself in the minority on this issue. The speaker for the majority was the Bad River chief Blackbird, and he may have delivered one of the greatest speeches ever given in the Chequamegon Bay region.

Unfortunately, the Ojibwe version of the speech has not survived, and it’s English version, originally translated by Paul Bealieu, exists in pieces recorded by multiple observers. None of these accounts captures all the nuances of the speech, so it is necessary to read all of them and then analyze the different passages to see its true brilliance.

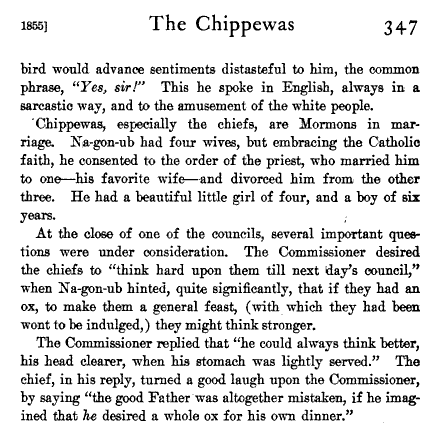

The first reference to Blackbird’s speech I remember seeing appeared in the eyewitness account of Dr. Richard F. Morse of Detroit who visited La Pointe that summer specifically to see the payment. His article, The Chippewas of Lake Superior appeared in the third volume of the Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. As you’ll read, it doesn’t speak very highly of Blackbird or the speech, celebrating instead the oratory of Naaganab, the Fond du Lac chief who was part of the minority faction and something of a celebrity among the visiting whites in 1855:

From Morse’s clear bias against Ojibwe culture, I thought there may have been more to this story, but my suspicions weren’t confirmed until I transcribed another account of the payment for Chequamegon History. An Indian Payment written by another eyewitness, Crocket McElroy, paints a different picture of Blackbird and quotes part of his speech:

Paul H. Beaulieu translated the speeches at the 1855 annuity payment (Minnesota Historical Society Collections).

In August 1855 about three thousand Chippewa Indians gathered at the village of Lapointe, on Lapointe Island, Lake Superior, for an Indian Payment and also to hold a council with the commissioner of Indian affairs, who at that time was George W. Monypenny of Ohio. The Indians selected for their orator a chief named Blackbird, and the choice was a good one, as Blackbird held his own well in a long discussion with the commissioner. Blackbird was not one of the haughty style of Indians, but modest in his bearing, with a good command of language and a clear head. In his speeches he showed much ingenuity and ably pleaded the cause of his people. He spoke in Chippewa stopping frequently to give the interpreter time to translate what he said into English. In beginning his address he spoke substantially as follows:

“My great white father, we are pleased to meet you and have a talk with you We are friends and we want to remain friends. We expect to do what you want us to do, and we hope that you will deal kindly with us. We wish to remind you that we are the source from which you have derived all your riches. Our furs, our timber, our lands, everything that we have goes to you; even the gold out of which that chain was forged (pointing to a heavy watch chain that the commissioner carried) came from us, and now we hope that you will not use that chain to bind us.”

These conflicting accounts of the largely-unremembered Bad River chief’s speech made me curious, and after I found the Blackbird-Wheeler-Manypenny letters written after the payment, I knew I needed to learn more about the speech. Luckily, digging further into the Wheeler Papers uncovered the following. To my knowledge, this is the first time it has been transcribed or published in any form.

[Italics, line breaks, and quotation marks added by transcriber to clearly differentiate when Wheeler is quoting a speaker. Blackbird’s words are in blue.]

O-da-nah Jan 18, 1856.

L. H. Wheeler to Richard M. Smith

Dear Sir,

The following is the substance of my notes taken at the Indian council at La Pointe a copy of which you requested. Council held in front of Mr. Austrian’s store house Aug 30. 1855.

Short speech first from Kenistino of Lac du Flambeau.

My father, I have a little to say to you & to the Indians. There is no difference between myself and the other chiefs in regard to the subject upon which we wish to speak. Our chiefs and young men & old men & even the women & children are all of the same mind. Blackbird our chief will speak for us & express our sentiments.

The Commissioner, Col Manypenny replied as follows.

My children I suppose you have come to reply to what I said to you day before yesterday. Is this what you have come for?

“Ah;” or yes, was the reply.

I am happy to see you, but would suggest whether you had not better come tomorrow. It is now late in the day and is unpleasant & you have a great deal to say and will not have time to finish, but if you will come tomorrow we shall have time to hear all you have to say. Don’t you think this will be the best way?

“Ah!” yes was the response.

Think well about what you want to say and come prepared to speak freely & fully about all you wish to say. I would like not only to hear the chiefs and old men speak, but the young men talk, and even the women, if they wish to come, let them come and listen too. I want the women to understand all that is said and done. I understand that some of the Indians were drunk last night with the fire-water. I hope we shall hear nothing more of it. If any body gives you liquor let me know it and I will deal with him as he deserves. I hope we shall have a good time tomorrow and be able to explain all about your affairs.

Aug 31. Commissioner opened the council by saying that he wanted all to keep order.

Let the whites and others sit down on the ground and we will have a pleasant time. If you have anything to say I hope you will speak to the point.

Black Bird. To the Indians.

My brother chiefs, head men & young men & children. I have listened well to all the men & women & others who have spoken in our councils and shall now tell it to my father. I shall have but one mouth to speak your will.

Nose [noose (no-say) “my father”]. My father. We present you our salutations in your heart. We salute you in the name of our great father the President, whose representative you are. We want the Great Spirit now to bless us. The Day is clear, and we hope our thoughts will be clear too. My intention is to tell you what the owner of life has done for us. He has provided for the life of us all. When the Lord made us he provided for us here upon earth he invested it (ie, he made provision for our wants) in the running streams, in the woods & lakes which abound with fish and in the wild animals. We regard you as if men like a spirit, perhaps it is because of your education, because you are so much wiser than we, but if we can trace our tradition right the Great Spirit has not made the white man to cheat us. There is a difference of opinion as it regards different colors among, as to which shall have the preeminence, but the Great Spirit made us to be happy before you discovered us.

I will now tell you about how it was with us before our payments, and before we sold any land. Our furs that we took we sold to our traders. We were then paid 4 martin skins for a dollar. 4 bears skins also & 4 beaver skins for $1.00 too. Can you wonder that we are poor? I say this to show you what our condition was before we had any payments. I[t] was by our treaties that we learned the use of money. I see you White men that sit here how you are dressed. I see your watch chains & seals and your rich clothing. Now I will tell you how it is with our traders. When they first came among us they were very poor, but by & by they became very fat & rich, and wear rich clothing and had their watches & gold chains such as I see you wear. But they got their things out of us. They were made rich at our expense. My father, you told us to bring our women here too. Here they are, and now behold them in their poverty, and pity their condition (at this juncture in the speech several old women stood dressed in their worn out blankets and tattered garments as if designed to appeal to his humanity[)].

My father, I am now coming to the point. We are here to protect our own interests. Our land which we got from our forefathers is ours & we must get what we can for it. Our traders step between us & our father to controll our interests, and we have been imposed upon. Mr. Gilbert was the one I shook hands with last year when he was sent here to treat for our lands. He was the one who was sent to uphold us in our poverty. We are thankful to see you both here to attend to our interests, and that we are permitted to express to you our wants. Last year you came here to treat for our lands we are now speaking about. We sold them because we were poor. We thank our father for bringing clothing to pay for them. We sold our land for our graves–that we might have a home, where the bones of our fathers are buried. We were not willing to sell the ashes of our relatives which are so dear to us. This was the reason why we sold our lands. It was not to pay debts over and over again, but to benefit the living, those of us who yet remain upon earth, our young men & women & children.

You said you wanted to see them. They have been sent for and are now here. Behold them in their poverty & see how poor they look.

They are poor because so much of our money is taken to pay old debts. We want the 90,000 dollars to be paid as we direct. We know that it is just and right that it should be so. We want to have the money paid in our own hands, and we will see that our just debts are paid. We want the 90,000 to feed our poor women, and after paying our just debts we want the remainder to buy what we want. This is the will of all present. The chiefs, & young men & old men & the women & children.

Let what I have now said, my father, enter your head & heart; and let it enter the head of our great father the President, that it may be as we have now said. We own no more land. We must hereafter provide for ourselves. We want to profit by all the provisions of the treaty we have now made. We want the whole annuity paid to us as stipulated in the treaty. I am now done. After you have spoken, perhaps there are others who would like to speak.

This is the first time my father that I have appeared dressed in a coat & pants & I must confess I feel a little awkward.

The Commissioner replied as follows

We have all heard & noted down what you have said. If any others wish to speak they had better speak first and I will reply to all at once.

The Grand Portage Indian [Adikoons] then spoke as follows.

My father, I have a few words to say, and I wish to speak what I think. We have long coveted the privilege of seeing our Great Father. Why not now embrace the opportunity to speak freely while he is here? This man will speak my mind. He is old enough to speak and is a man endowed with good sense. He will speak our minds without reserve.

When we look around us, we think of our God who is the maker of us all. You have come here with the laws of that God we have talked about, and you profess to be a Christian and acknowledge the authority of God. The word of God ought to be obeyed not only by the Indians, but by all. When we see you, we think you must respect that word of God, who gives life to all. Your advice is like the law of God. Those who listen to his law are like God–firm as a rock, (not fickle and vacilating). When the word of the Great Spirit ends. When there is an end to life, we are all pleased with the advice you have given us, and intend to act in accord with it. If we are one here, and keep the word of the Great Spirit we shall be one here after. In what Blackbird said he expressed the mind of a majority of the chiefs now present. We wish the stipulations of the treaty to be carried out to the very letter.

I wish to say our word about our reserves. Will these reserves made for each of our bands, be our homes forever?

When we took credits of our trader last winter, and took no furs to pay him, and wish to get hold of this 90,000 dollars, that we may pay him off of that. This is all we came here for. We want the money in our own hands & we will pay our own traders. We do not think it is right to pay what we do not owe. I always know how I stand my acct. and we can pay our own debts. From what I have now said I do not want you to think that we want the money to cheat our creditors, but to do justice to them I owe. I have my trader & know how much I owe him, & if the money is paid into the hands of the Indians we can pay our own debts.

Naganub.

We have 90,000 dollars set apart to pay our traders, for my part I think it is just that the money should go for this object. We all know that the traders help us. We could not well do without them.

Buffalo.

We who live here are ready to pay our just debts. Some have used expressions as though these debts were not just. I have lived here many years and been very poor. There are some here who have been pleased to assist me in my poverty. They have had pity on me. Those we justly owe I don’t think ought to be defrauded. The trader feeds our women & children. We cannot live one winter without him. This is all I have to say.

[Wheeler does not identify a new speaker here, but marks a a star (right). Kohl (below) attributes the line about the “came out of the water” to Blackbird, but the line about the copper diggings contradicts Blackbird’s earlier statement, in Kohl, about not knowing their value. This, and Wheeler’s marking of Blackbird as the one who spoke after this speech would indicate this is Buffalo still talking].

[Wheeler does not identify a new speaker here, but marks a a star (right). Kohl (below) attributes the line about the “came out of the water” to Blackbird, but the line about the copper diggings contradicts Blackbird’s earlier statement, in Kohl, about not knowing their value. This, and Wheeler’s marking of Blackbird as the one who spoke after this speech would indicate this is Buffalo still talking].

Our rights ought to be protected. When commissioners have come here to treat for our lands, we have always listened well to their words. Not because we did not know ourselves the worth of our lands. We have noticed the ancient copper diggings, and know their worth. We have never refused to listen to the words of our Great Father. He it is true has had the power but we have made him rich. The traders have always wanted pay for what we do not remember to have bought. At Crow [W]ing River when our lands were ceded there, then there was a large sum demanded to pay old debts. We have always paid our traders we have acted fair on our part. At St. Peters also there was a large amount of old debts to be paid–many of them came from places unknown–for what I know they came out of the water. We think many of them came out of the same bag, and are many of them paid over & over again at every treaty.

Black Bird.

I get up no[w] to finish what you have put into my heart. The night would be heavy on my breast should I retain any of the words of them with whom I have councilled & for whom I speak. I speak no[w] of farmers, carpenters, & other employees of Govt. Where is the money gone to for them? We have not had these laborers for several years that has been appropriated. Where is the money that has been set apart to pay them? You will not probably see your Red Children again in after years to council with them. So we protest by the present opportunity to speak to you of our wants & grievances. We regard you as standing in the place of our great father at Washington, and your judgement must be correct. This is all I have to say about our arrearages, we have not two tongues.

As exciting as it was to have the full speech, as I transcribed some of the passages, some of them seemed very familiar. Sure enough, on page 53 of Johann Georg Kohl’s Kitchi-Gami: Life Among the Lake Superior Ojibway, there is another whole version. Kitchi-Gami is one of the standards of Ojibwe cultural history, and I use it for reference fairly often, but it had been so long since I had read the book cover to cover that I forgot that Kohl had been another witness that August day in 1855:

When one considers that Paul Beaulieu, the man giving the official English translation was probably speaking in his third language, after Ojibwe and Metis-French, and that Kohl was a native German speaker who understood English but may have been relying on his own mix-blood translator, it is remarkable how similar these two accounts are. This makes the parts where they differ all the more fascinating. Undoubtedly there are key parts of this speech that we could only understand if we had the original Ojibwe version and a full understanding of the complicated artistry of Ojibwe rhetoric with all its symbolism and metaphor. Even so, there are enough outstanding passages here for me to call it a great speech.

“My father…great Father…We regard you as if men like a spirit, perhaps it is because of your education, because you are so much wiser than we…”

The ritual language of kinship and humility in traditional Ojibwe rhetoric can be off-putting to those who haven’t read many Ojibwe speeches, and can be mistaken as by-product of American arrogance and paternalism toward Native people. However, the language of “My Father” predates the Americans, going all the way back to New France, and does not necessarily indicate any sort weakness or submission on the part of the speaker. Richard White, Michael Witgen, and Howard Paap, much smarter men than I, have dedicated pages to what Paap calls “fur-trade theater,” so I won’t spend too much time on it other than to say that 1855 was indeed a low point in Ojibwe power, but Blackbird is only acting the ritual part of the submissive child here in a long-running play. He is not grovelling.

On the contrary, I think Blackbird is playing Manypenny here a little bit. George Manypenny’s rise to the head of Indian Affairs coincided with the end of American removal policy and the ushering in of the reservation era. In the short term, this was to the political advantage of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. In Manypenny the Ojibwe got a “Father” who would allow them to stay in their homelands, but they also got a zealous believer in the superiority of white culture who wanted to exterminate Indian cultures as quickly as possible.

In a future post about the 1855 treaty negotiations with the Minnesota Ojibwe we will see how Commissioner Manypenny viewed the Ojibwe, including masterful politicians like Flat Mouth and Hole in the Day, as having the intelligence of children. Blackbird shows himself a a savvy politician here by playing into these prejudices as a way to get the Commissioner off his guard. Other parts of the speech lead me to doubt that Blackbird sincerely believed that the Americans were “so much wiser” than he was.

My intention is to tell you what the owner of life has done for us. He has provided for the life of us all. When the Lord made us he provided for us here upon earth he invested it (ie, he made provision for our wants) in the running streams, in the woods & lakes which abound with fish and in the wild animals… There is a Great Spirit from whom all good things here on earth come. He has given them to mankind–to the white as to the red man; for He sees no distinction of colour…but if we can trace our tradition right the Great Spirit has not made the white man to cheat us. There is a difference of opinion as it regards different colors among, as to which shall have the preeminence, but the Great Spirit made us to be happy before you discovered us…

This part varies slightly between Wheeler and Kohl, but in both it is very eloquent and similar in style to many Ojibwe speeches of the time. One item that piqued my interest was the line about the “difference of opinion.” Many Americans at the time understood the expansion of the United States and the dispossession of Native peoples in religious terms. It was Manifest Destiny. The Ojibwe also sought answers for their hardships in prophecy. On pages 117 and 118 of History of the Ojibwe People, William Warren relates the following:

Warren, writing in the late 1840s and early 1850s, contrasts this tradition with the popularity of the prophecies of Tenskwatawa, brother of Tecumseh, in Ojibwe country forty years earlier. Tenskwatawa taught that Indians would inherit North America and drive whites from the continent. Blackbird seems to be suggesting that in 1855 this question of prophecy was not settled among the Lake Superior Ojibwe. Presumably there would have been fertile ground for a charismatic millenarian Native spiritual leader along the lines of Neolin, Tenskwatawa, or Wovoka to gain adherents among the Lake Superior Ojibwe at that time.

Johann Georg Kohl recorded Blackbird’s speech in his well known account of Lake Superior in the Summer of 1855, Kitchi-Gami: Life Among the Lake Superior Ojibway.

Our furs, our timber, our lands, everything that we have goes to you; even the gold out of which that chain was forged…Now I will tell you how it is with our traders. When they first came among us they were very poor, but by & by they became very fat & rich, and wear rich clothing and had their watches & gold chains such as I see you wear. But they got their things out of us. They were made rich at our expense…and now we hope that you will not use that chain to bind us…

The gold chain appears in each of McElroy, Wheeler, and Kohl’s accounts. It acts as a symbol on multiple levels. To Blackbird, the gold represents the immense wealth produced during the fur trade on the backs of Indian trappers. By 1855, with the fur trade on its last legs, some of the traders are very wealthy while the Ojibwe are much poorer than they were when the trade started. The gold also stands in for the value of the ceded territory itself, specifically the lakeshore lands (ceded in 1842), which thirteen years later were producing immense riches from that other shiny metal, copper. Finally, in McElroy’s account, we also see the chain acting as the familiar symbol of bondage.

…We sold our land for our graves–that we might have a home, where the bones of our fathers are buried…Our debts we will pay. But our land we will keep. As we have already given away so much, we will, at least, keep that land you have left us, and which is reserved for us. Answer us, if thou canst, this question. Assure us, if thou canst, that this piece of land reserved for us, will really always be left to us…

This passage of Blackbird’s speech, and a similar statement by the “Grand Portage Indian” (identified by Morse as Adikoons or Little Caribou), indicate that perhaps, the actual disbursement of the $90,000 was a secondary to the need to hold Agent Gilbert and the Government to their word. It was very important to the Ojibwe that words of the Treaty of 1854 be rock-solid, not for a need to pay off debts or to get annuity payments, but because the Government absolutely needed to keep its promise to grant reservations around the ancestral villages. The memory of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, less than five years earlier, cast a long shadow over this decade. Paap argues in Red Cliff, Wisconsin that the singular goal of the treaty, from the Ojibwe perspective, was to end the removal talk forever, a goal that had seemingly been accomplished. To hear the Government trying to weasel out of a provision of the 1854 Treaty must have been very frightening to those who heard Robert Stuart’s promises in 1842. This time, the chiefs had to make sure a promise of a permanent homeland for their people wouldn’t turn out to be another lie.

This is the first time my father that I have appeared dressed in a coat & pants & I must confess I feel a little awkward.

You can argue that a great speech can’t end with the line, “I must confess I feel a little awkward.” However, I will argue that this might be the best line of all. It is another example of the political brilliance of Blackbird. The Bad River chief knew who his allies were, knew who his opponents were, and knew how to take advantage of the Commissioner’s prejudices. Clothing played a role in all of this.

George Manypenny despised Indian cultures. In fact, the whole council had almost derailed a few days before the speeches when the Commissioner refused to smoke the pipe presented to him by the chiefs in open ceremony. He remedied this insult somewhat by smoking it later while indoors, but he let it be known that he had no use for Ojibwe songs, dances, rituals or clothing. This put Blackbird, an unapologetic traditionalist and practitioner of the midewiwin at a distinct disadvantage, when compared with chiefs like Naaganab who were known to wear European clothes and profess to be Christians.

Although he had the majority of the people behind him, Blackbird had very little negotiating power. He had to persuade Manypenny that he was in the right. He had no chance unless he could appear to the Commissioner that he was trying to become “civilized” and was therefore worthy enough to be listened to. However, by wearing European clothes, he ran the risk of alienating the majority of the people in the crowd who preferred traditional ways and dress. Furthermore, the chiefs most likely to oppose him, Naaganab and Jayjigwyong (Little Buffalo) had been dressing like whites (I would argue also largely for political reasons) for years and were much more likely to come across as “civilized” in the Commissioner’s eyes.

How did the chief solve these dilemmas? In the same way he turned Manypenny’s request to see the Ojibwe women to his advantage, he used the clothing to demonstrate that he had gone out of his way to work with the Commissioner’s wishes, while still solidifying the backing of the traditional Ojibwe majority and putting his opponents on the defensive all with one well-timed joke. Although this joke seems to have gone over Wheeler’s head, and likely Manypenny’s as well, Kohl’s mention of the “applauding laughter of the entire assembly,” shows it reached its target audience. So, contrary to first appearances, the crack about the awkward pants is anything but an awkward ending to this speech.

Conclusion

In the 1840s and early 1850s, Blackbird rarely appears in the historical record. Here and there he is mentioned as a second chief to Chief Buffalo or as leading the village at Bad River. Many mentions of him by English-speaking authors are negative. He is referred to as a rascal, scoundrel, or worse, and I’ve yet to find any mention of his father or other family members as being prominent chiefs.

However, in the late 1850s and early 1860s, he was clearly the most important speaker for not just the La Pointe Band, but for the other Lake Superior Bands as well. This was a mystery to me. I temporarily hypothesized his rise was due to the fact that Chequamegon was seen as the center of the nation and that when Buffalo died, Blackbird succeeded to the position by default. However, this view doesn’t really fit what I understood as Ojibwe leadership.

This speech puts that interpretation to rest. Blackbird earned his position by merit and by the will of the people.

He did not, however, win on the question of the $90,000. A Chequamegon History reader recently sent me a document showing it was eventually paid to the creditors directly by the Agent. However, if my argument is correct, the more important issue was that the Government keep its word that the reservations would belong to the Ojibwe forever. The land question wasn’t settled overnight, and it required many leaders over the last 160 years to hold the United States to its word. But today, Blackbird’s descendants still live beside the swamps of Mashkiziibii at least partially because of the determination of their great ogimaa.

Sources:

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings round Lake Superior. London: Chapman and Hall, 1860. Print.

McClurken, James M., and Charles E. Cleland. Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights / James M. McClurken, Compiler ; with Charles E. Cleland … [et Al.]. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State UP, 2000. Print.

McElroy, Crocket. “An Indian Payment.” Americana v.5. American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. The Voice of the Crane Echoes Afar: The Sociopolitical Organization of the Lake Superior Ojibwa, 1640-1855. New York: Garland Pub.,1997. Print.

—————— William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1991. Print.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.

Happy Chequamegon New Year, 1844!

December 31, 2013

To mark the new year 2014, today we’ll go back 170 years and look at New Year’s 1844. . I haven’t researched this specific topic, but a study could certainly be done on celebrations of the first of January in the Lake Superior country before 1850. My impressions are that New Years was one of the most joyously-celebrated holidays of the era. In the journals and records, it stands out as an occasion with plenty of food, drink, kissing, and visiting. I would be interested to know the origins of the New Year customs described below. Obviously, the observation of January 1st comes from the Christian rather than the Ojibwe calendar, but these celebrations seem well established by 1844, and are somewhat alien to the two Anglo-American authors. These are customs that certainly date back to the British fur-trade era, probably stretch back to the French era, and pull in practices that are much older than either.

Although, the celebration of the New Year on January 1st didn’t originate with the Ojibwe, in this part of the the world, it integrated several elements of Ojibwe and French-Ojibwe mix-blood culture. This is what our two American authors, Rev. Leonard Wheeler at La Pointe, and the unidentified carpenter at Fond du Lac, cannot seem to figure out.

Wheeler, having been at La Pointe for a few years, is prepared with gifts and knows to honor the chiefs and elders, but he still hasn’t wrapped his head around the concept that the Ojibwe at his house are engaged in a tribal tradition of “feasting” door to door, rather than begging (as his Protestant ethic of “individual initiative” demands).

The carpenter, who we met in this post, wants to participate in all the festivities but he freezes at a key moment and doesn’t know what to do when a group of pretty girls shows up at his door. Let’s hope that by New Year 1845, he made good on his promise that “they’ll never slip through my fingers in that way again.”

La Pointe, January 1, 1844:

Missionary Journal Jan 1, 1844. L. H. Wheeler

Jan 1. 1844. To day the Indians called as usual for their presents. By keeping our doors locked we were able to have a quiet house till after the customary duties & labors of the morning were through, when our house was soon thronged with visitors very happy to see us, and especially when they received their two cakes apiece as a reward for their congratulations. Nearly all our ladies received a kiss and some of them were, in this respect highly favored. At 9 o’clock the bell was rung to give notice that we were ready to receive the Chief and his suit. When Buffalow and Blackbird with the elderly men entered, followed by the principle men of influence in the Band–and these were succeeded by the young men. The Indians seated in chairs and on the floor had a short smoke, after which they took their presents and departed. Then came the Sabbath and day school scholars, who received in addition to their cakes, some little books, work bags and other present from their teachers when they sang fun little hymns and departed. Our next company at about 11, consisted of our Christian Indians. Embracing 6 families. They received their presents of flour, pork, corn potatoes, and turnips and went away very much pleased. At dinner we were favored with the company of Mrs La Pointe, Francis & Mary [St. Amo?]. At Supper, we had Miss Gates–and all her scholars and some of Mrs Spooners larger Scholars. At 8 o’clock we had a full meeting of the Indians at the school room after which our tea party returned again to our house, and spent the evening in singing, visiting and in other ways highly gratifying to their juvenile feelings, and adapted to make a good impression upon their minds. We had the privilege of giving away all our cakes and of receiving nearly all the the expressions of gratitude we expect during the year, except where similar favors are again bestowed.

The same night at Fond du Lac of Lake Superior:

Jan 1st 1844 Warm and misty—more like April fool than New years day

1844

Jan 1st On this day I must record the honor of being visited by some half dozen pretty squaws expecting a New Years present and a kiss, not being aware of the etiquette of the place, we were rather taken by surprise, in not having presents prepared—however a few articles were mustered, an I must here acknowledge that although, out presents were not very valuable, we were entitled to the reward of a kiss, which I was ungallant enough not to claim, but they’ll never slip through my fingers in that way again.

Happy New Year!

(Both of these journals are from the Wheeler Family Papers, held by the Wisconsin Historical Society at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center in Ashland.)

The Enemy of my Enemy: The 1855 Blackbird-Wheeler Alliance

November 29, 2013

Identified by the Minnesota Historical Society as “Scene at Indian payment, probably at Odanah, Wisconsin. c. 1865.” by Charles Zimmerman. Judging by the faces in the crowd, this is almost certainly the same payment as the more-famous image that decorates the margins of the Chequamegon History site (Zimmerman MNHS Collections)

A staunch defender of Ojibwe sovereignty, and a zealous missionary dedicating his life’s work to the absolute destruction of the traditional Ojibwe way of life, may not seem like natural political allies, but as Shakespeare once wrote, “Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows.”

In October of 1855, two men who lived near Odanah, were miserable and looking for help. One was Rev. Leonard Wheeler who had founded the Protestant mission at Bad River ten years earlier. The other was Blackbird, chief of the “Bad River” faction of the La Pointe Ojibwe, that had largely deserted La Pointe in the 1830s and ’40s to get away from the men like Wheeler who pestered them relentlessly to abandon both their religion and their culture.

Their troubles came in the aftermath of the visit to La Pointe by George Manypenny, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to oversee the 1855 annuity payments. Many readers may be familiar with these events, if they’ve read Richard Morse’s account, Chief Buffalo’s obituary (Buffalo died that September while Manypenny was still on the island), or the eyewitness account by Crockett McElroy that I posted last month. Taking these sources together, some common themes emerge about the state of this area in 1855:

- After 200 years, the Ojibwe-European relationship based on give and take, where the Ojibwe negotiated from a position of power and sovereignty, was gone. American government and society had reached the point where it could by impose its will on the native peoples of Lake Superior. Most of the land was gone and with it the resource base that maintained the traditional lifestyle, Chief Buffalo was dead, and future chiefs would struggle to lead under the paternalistic thumb of the Indian Department.

- With the creation of the reservations, the Catholic and Protestant missionaries saw an opportunity, after decades of failures, to make Ojibwe hunters into Christian farmers.

- The Ojibwe leadership was divided on the question of how to best survive as a people and keep their remaining lands. Some chiefs favored rapid assimilation into American culture while a larger number sought to maintain traditional ways as best as possible.

- The mix-blooded Ojibwe, who for centuries had maintained a unique identity that was neither Native nor European, were now being classified as Indians and losing status in the white-supremacist American culture of the times. And while the mix-bloods maintained certain privileges denied to their full-blooded relatives, their traditional voyageur economy was gone and they saw treaty payments as one of their only opportunities to make money.

- As with the Treaties of 1837 and 1842, and the tragic events surrounding the attempted removals of 1850 and 1851, there was a great deal of corruption and fraud associated with the 1855 payments.

This created a volatile situation with Blackbird and Wheeler in the middle. Before, we go further, though, let’s review a little background on these men.

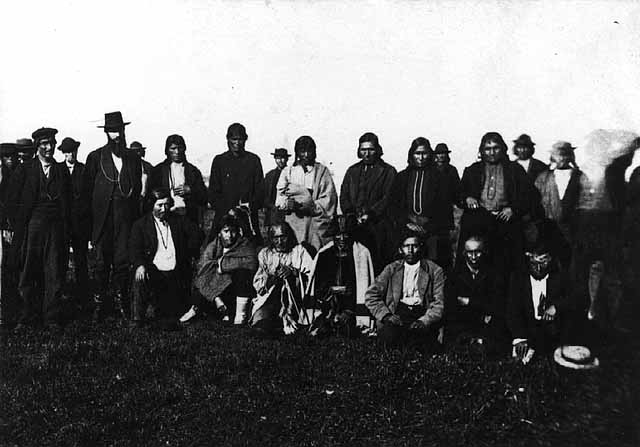

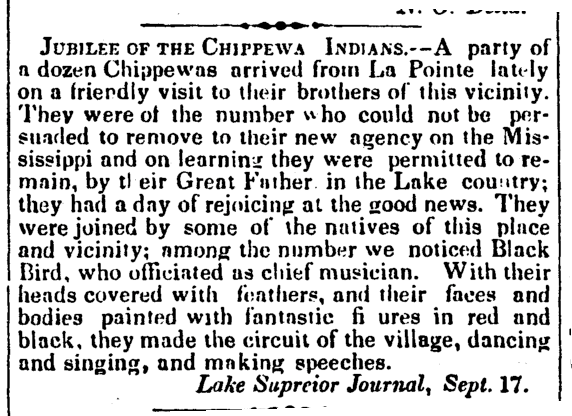

This 1851 reprint from Lake Superior Journal of Sault Ste. Marie shows how strongly Blackbird resisted the Sandy Lake removal efforts and how he was a cultural leader as well as a political leader. (New Albany Daily Ledger, October 9, 1851. Pg. 2).

Who was Blackbird?

Makadebineshii, Chief Blackbird, is an elusive presence in both the primary and secondary historical record. In the 1840s, he emerges as the practical leader of the largest faction of the La Pointe Band, but outside of Bad River, where the main tribal offices bear his name, he is not a well-known figure in the history of the Chequamegon area at all.

Unlike, Chief Buffalo, Blackbird did not sign many treaties, did not frequently correspond with government officials, and is not remembered favorably by whites. In fact, his portrayal in the primary sources is often negative. So then, why did the majority of the Ojibwe back Blackbird at the 1855 payment? The answer is probably the same reason why many whites disliked him. He was an unwavering defender of Ojibwe sovereignty, he adhered to his traditional culture, and he refused to cooperate with the United States Government when he felt the land and treaty rights of his people were being violated.

One needs to be careful drawing too sharp a contrast between Blackbird and Buffalo, however. The two men worked together at times, and Blackbird’s son James, later identified his father as Buffalo’s pipe carrier. Their central goals were the same, and both labored hard on behalf of their people, but Buffalo was much more willing to work with the Government. For instance, Buffalo’s response in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, when the fate of Ojibwe removal was undecided, was to go to the president for help. Blackbird, meanwhile, was part of the group of Ojibwe chiefs who hoped to escape the Americans by joining Chief Zhingwaakoons at Garden River on the Canadian side of Sault Ste. Marie.

Still, I hesitate to simply portray Blackbird and Buffalo as rivals. If for no other reason, I still haven’t figured out what their exact relationship was. I have not been able to find any reference to Blackbird’s father, his clan, or really anything about him prior to the 1840s. For a while, I was working under the hypothesis that he was the son of Dagwagaane (Tugwaganay/Goguagani), the old Crane Clan chief (brother of Madeline Cadotte), who usually camped by Bad River, and was often identified as Buffalo’s second chief.

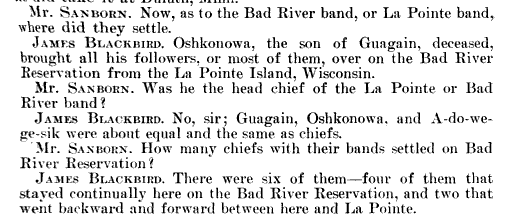

However, that seems unlikely given this testimony from James Blackbird that identifies Oshkinawe, a contemporary of the elder Blackbird, as the heir of Guagain (Dagwagaane):

Statement of James Blackbird: Condition of Indian affairs in Wisconsin: hearings before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, [61st congress, 2d session], on Senate resolution, Issue 263. pg 203. (Digitized by Google Books).

It seems Commissioner Manypenny left La Pointe before the issue was entirely settled, because a month later, we find a draft letter from Blackbird to the Commissioner transcribed in Wheeler’s hand:

Mushkesebe River Oct. 1855

Blackbird. Principal chief of the Mushkisibi-river Indians to Hon. G. Manepenny Com. of Indian Affairs Washington City.

Father; Although I have seen you face to face, & had the privilege to talking freely with you, we did not do all that is to be attended to about our affairs. We have not forgotten the words you spoke to us, we still keep them in our minds. We remember you told us not to listen to all the foolish stories that was flying about–that we should listen to what was good, and mind nothing about anything else. While we listened to your advice we kept one ear open and the other shut, & [We?] kept retained all you spoke said in our ears, and. Your words are still ringing in our ears. The night that you left the sound of the paddles in boat that carried you away from us was had hardly gone ceased before the minds of some of the chiefs was were tuned by the traders from the advice you gave, but we did not listen to them. Ja-jig-wy-ong, (Buffalo’s son) son says that he & Naganub asked Mr. Gilbert if they could go to Washington to see about the affairs of the Indians. Now father, we are sure you opened your heart freely to us, and did not keep back anything from us that is for our good. We are sure you had a heart to feel for us & sympathise with us in our trials, and we think that if there is any important business to be attended to you would not have kept it secret & hid it from us, we should have knew it. If I am needed to go to Washington, to represent the interests of our people, I am ready to go. The ground that we took against about our old debts, I am ready to stand shall stand to the last. We are now in Mr. Wheelers house where you told us to go, if we had any thing to say, as Mr. W was our friend & would give us good advice. We have done so. All the chiefs & people for whom I spoke, when you were here, are of the same mind. They all requested before they left that I should go to Washington & be sure & hold on to Mr. Wheeler as one to go with me, because he has always been our steadfast friend and has al helped us in our troubles. There is another thing, my father, which makes us feel heavy hearted. This is about our reservation. Although you gave us definite instructions about it, there are some who are trying to shake our reserve all to pieces. A trader is already here against our will & without any authority from Govt, has put him up a store house & is trading with our people. In open council also at La Pointe when speaking for our people, I said we wanted Mr. W to be our teacher, but now another is come which whom we don’t want, and is putting up a house. We supposed when you spoke to us about a teacher being permitted to live among us, you had reference to the one we now have, one is enough, we do not wish to have any more, especially of the kind of him who has just come. We forbid him to build here & showed him the paper you gave us, but he said that paper permitted him rather than forbid him to come. If the chiefs & young men did not remember what you told them to keep quiet there would already be have been war here. There is always trouble when there two religions come together. Now we are weak and can do nothing and we want you to help us extend your arms to help us. Your arms can extend even to us. We want you to pity & help us in our trouble. Now we wish to know if we are wanted, or are permitted, three or four of us to come to which Washington & see to our interests, and whether our debts will be paid. We would like to have you write us immediately & let us know what your will is, when you will have us come, if at all. One thing further. We do not want any account to be allowed that was not presented to us for us to pass our opin us to pass judgement on, we hear that some such accounts have been smuggled in without our knowledge or consent.

The letter is unsigned, lacks a specific date, and has numerous corrections, which indicate it was a draft of the actual letter sent to Manypenny. This draft is found in the Wheeler Family Papers in the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center. As interesting as it is, Blackbird’s letter raises more questions than answers. Why is the chief so anxious to go to Washington? What are the other chiefs doing? What are these accounts being smuggled in? Who are the people trying to shake the reservation to pieces and what are they doing? Perhaps most interestingly, why does Blackbird, a practitioner of traditional religion, think he will get help from a missionary?

For the answer to that last question, let’s take a look at the situation of Leonard H. Wheeler. When Wheeler, and his wife, Harriet came here in 1841, the La Pointe mission of Sherman Hall was already a decade old. In a previous post, we looked at Hall’s attitudes toward the Ojibwe and how they didn’t earn him many converts. This may have been part of the reason why it was Wheeler, rather than Hall, who in 1845 spread the mission to Odanah where the majority of the La Pointe Band were staying by their gardens and rice beds and not returning to Madeline Island as often as in the past.

When compared with his fellow A.B.C.F.M. missionaries, Sherman Hall, Edmund Ely, and William T. Boutwell, Wheeler comes across as a much more sympathetic figure. He was as unbending in his religion as the other missionaries, and as committed to the destruction of Ojibwe culture, but in the sources, he seems much more willing than Hall, Ely, or Boutwell to relate to Ojibwe people as fellow human beings. He proved this when he stood up to the Government during the Sandy Lake Tragedy (while Hall was trying to avoid having to help feed starving people at La Pointe). This willingness to help the Ojibwe through political difficulties is mentioned in the 1895 book In Unnamed Wisconsin by John N. Davidson, based on the recollections of Harriet Wheeler:

From In Unnamed Wisconsin pg. 170 (Digitized by Google Books).

So, was Wheeler helping Blackbird simply because it was the right thing to do? We would have to conclude yes, if we ended it here. However, Blackbird’s letter to Manypenny was not alone. Wheeler also wrote his own to the Commissioner. Its draft is also in the Wheeler Family Papers, and it betrays some ulterior motives on the part of the Odanah-based missionary:

example not to meddle with other peoples business.

Mushkisibi River Oct. 1855

L.H. Wheeler to Hon. G.W. Manypenny

Dear Sir. In regard to what Blackbird says about going to Washington, his first plan was to borrow money here defray his expenses there, & have me start on. Several of the chiefs spoke to me before soon after you left. I told them about it if it was the general desire. In regard to Black birds Black Bird and several of the chiefs, soon after you left, spoke to me about going to Washington. I told them to let me know what important ends were to be affected by going, & how general was the desire was that I should accompany such a delegation of chiefs. The Indians say it is the wish of the Grand Portage, La Pointe, Ontonagun, L’anse, & Lake du Flambeaux Bands that wish me to go. They say the trader is going to take some of their favorite chiefs there to figure for the 90,000 dollars & they wish to go to head them off and save some of it if possible. A nocturnal council was held soon after you left in the old mission building, by some of the traders with some of the Indians, & an effort was made to get them Indians to sign a paper requesting that Mr. H.M. Rice be paid $5000 for goods sold out of the 90,000 that be the Inland Indians be paid at Chippeway River & that the said H.M. Rice be appointed agent. The Lake du Flambeau Indians would not come into the [meeting?] & divulged the secret to Blackbird. They wish to be present at [Shington?] to head off [sail?] in that direction. I told Blackbird I thought it doubtful whether I could go with him, was for borrowing money & starting immediately down the Lake this fall, but I advised him to write you first & see what you thought about the desirability of his going, & know whether his expenses would be born. Most of the claimants would be dread to see him there, & of course would not encourage his going. I am not at all certain certain that I will be [considered?] for me to go with Blackbird, but if the Dept. think it desirable, I will take it into favorable consideration. Mr. Smith said he should try to be there & thought I had better go if I could. The fact is there is so much fraud and corruption connected with this whole matter that I dread to have anything to do with it. There is hardly a spot in the whole mess upon which you can put your finger without coming in contact with the deadly virus. In regard to the Priest’s coming here, The trader the Indians refer to is Antoine [Gordon?], a half breed. He has erected a small store house here & has brought goods here & acknowledges that he has sold them and defies the Employees. Mssrs. Van Tassel & Stoddard to help [themselves?] if they can. He is a liquer-seller & a gambler. He is now putting up a house of worship, by contract for the Catholic Priest. About what the Indians said about his coming here is true. In order to ascertain the exact truth I went to the Priest myself, with Mr. Stoddard, Govt [S?] man Carpenter. His position is that the Govt have no right to interfere in matters of religion. He says he has a right to come here & put up a church if there are any of his faith here, and they permit him to build on his any of their claims. He says also that Mr. Godfrey got permission of Mr. Gilbert to come here. I replied to him that the Commissioner told me that it was not the custom of the Gov. to encourage but one denomination of Christians in a place. Still not knowing exactly the position of Govt upon the subject, I would like to ask the following questions.

1. When one Missionary Society has already commenced labors a station among a settlement of Indians, and a majority of the Indians people desire to have him for their religious teacher, have missionaries of another denomination a right to come in and commence a missionary establishment in the same settlement?

Have they a right to do it against the will of a majority of the people?

Have they a right to do it in any case without the permission of the Govt?

Has any Indian a right, by sold purchase, lease or otherwise a right to allow a missionary to build on or occupy a part of his claim? Or has the same missionary a right to arrange with several missionaries Indians for to occupy by purchase or otherwise a part of their claims severally? I ask these questions, not simply with reference to the Priest, but with regard to our own rights & privileges in case we wish to commence another station at any other point on the reserve. The coming of the Catholic Priest here is a [mere stroke of policy, concocted?] in secret by such men as Mssrs. Godfrey & Noble to destroy or cripple the protestant mission. The worst men in the country are in favor of the measure. The plan is under the wing of the priest. The plan is to get in here a French half breed influence & then open the door for the worst class of men to come in and com get an influence. Some of the Indians are put up to believe that the paper you gave Blackbird is a forgery put up by the mission & Govt employ as to oppress their mission control the Indians. One of the claimants, for whom Mr. Noble acts as attorney, told me that the same Mr. Noble told him that the plan of the attorneys was to take the business of the old debts entirely out of your hands, and as for me, I was a fiery devil they when they much[?] tell their report was made out, & here what is to become of me remains to be seen. Probably I am to be hung. If so, I hope I shall be summoned to Washington for [which purpose?] that I may be held up in [t???] to all missionaries & they be [warned?] by my […]

The dramatic ending to this letter certainly reveals the intensity of the situation here in the fall of 1855. It also reveals the intensity of Wheeler’s hatred for the Roman Catholic faith, and by extension, the influence of the Catholic mix-blood portion of the La Pointe Band. This makes it difficult to view the Protestant missionary as any kind of impartial advocate for justice. Whatever was going on, he was right in the middle of it.

So, what did happen here?