Ishkigamizigedaa! Bad River Sugar Camps 1844

March 15, 2014

Indian Sugar Camp by Seth Eastman c.1850 (Minnesota Historical Society)

Since we’re into the middle of March 2014 and a couple of warm days have had people asking, “Is it too early to tap?” I thought it might be a good time to transcribe a document I’ve been hanging onto for a while.

170 years ago, that question would have been on everyone’s mind. The maple sugar season was perhaps the most joyous time of the year. The starving times of February and early March were on the way out, and food would be readily available again. Friends and relatives, separated during the winter hunts, might join back together in sugar camp, play music around the fire as the sap boiled, and catch up on the winter’s news.

Probably the only person around here who probably didn’t like the sugar season was the Rev. Sherman Hall. Hall, who ran the La Pointe mission and school, aimed to convert Madeline Island’s Native and non-Native inhabitants to Protestantism. To him, Christianity and “civilization” went hand and hand with hard labor and settling down in one place to farm the land. When, at this time of the year, all his students abandoned the Island with everyone else, for sugar camps at Bad River and elsewhere on the mainland and other islands, he saw it as an impediment to their progress as civilized Christians.

Rev. Leonard Wheeler, who joined Hall in 1841, shared many of his ethnocentric attitudes toward Ojibwe culture. However, over the next two decades Wheeler would show himself much more willing than Hall and other A.B.C.F.M. missionaries to meet Ojibwe people on their own cultural turf. It was Wheeler who ultimately relocated from La Pointe to Bad River, where most of the La Pointe Band now stayed, partly to avoid the missionaries, where he ultimately befriended some of the staunchest traditionalists among the Ojibwe leadership. And while he never came close to accepting the validity of Ojibwe religion and culture, he would go on to become a critical ally of the La Pointe Band during the Sandy Lake Tragedy and other attempted land grabs and broken Government promises of the 1850s and ’60s.

In 1844, however, Wheeler was still living on the island and still relatively new to the area. Coming from New England, he knew the process and language of making sugar–it’s remarkable how little the sugar-bush vocabulary has changed in the last 170 years–but he would see some unfamiliar practices as he followed the people of La Pointe to camp in Bad River. Although there is some condescending language in his written account, not all of his comparisons are unfavorable to his Ojibwe neighbors.

Of course, I may have a blind spot for Wheeler. Regular readers might not be surprised that I can identify with his scattered thoughts, run-on sentences, and irregular punctuation. Maybe for that reason, I thought this was a document that deserved to see the light of day. Enjoy:

Bad River Monday March 25, 1844

We are now comfortably quartered at the sugar camps, Myself, wife, son and Indian Boy. Here we have been just three weeks today.

I came myself the middle of the week previous and commenced building a log cabin to live in with the aid of two men , we succeeded in putting up a few logs and the week following our house was completed built of logs 12 by 18 feet long and 4 feet high in the walls, covered with cedar birch bark of most miserable quality so cracked as to let in the wind and rain in all parts of the roof. We lived in a lodge the first week till Saturday when we moved into our new house. Here we have, with the exception of a few very cold days, been quite comfortable. We brought some boards with us to make a floor–a part of this is covered with a piece of carpeting–we have a small cooking stove with which we have succeeded in warming our room very well. Our house we partitioned off putting the best of the bark over the best part we live in, the other part we use as a sort of storeroom and woodhouse.

We have had meetings during on the Sabbath and those who have been accustomed to meet with us have generally been present. We have had a public meeting in the foreroom at Roberts sugar bush lodge immediately after which my wife has had a meeting with the women or a sabbath school at our house. Thus far our people have seemed to keep up their interest in Religion.

They have thus far generally remembered the Sabbath and in this respect set a good example to their neighbors, who both (pagan) Indians and Catholics generally work upon the Sabbath as upon other days. If our being here can be the means of preventing these from declension in respect to religion and from falling into temptation, (especially) in respect to the Sabbath, an important end will be gained.

The sugar making season is a great temptation to them to break the sabbath. It is quite a test upon their faith to see their sap buckets running over with sap and they yet be restrained from gathering it out of respect to the sabbath, especially should their neighbors work in the same day. Yet they generally abstain from Labor on the Sabbath. In so doing however they are not often obliged to make much sacrifice. By gathering all the sap Saturday night, their sap buckets do not ordinarily make them fill in one day, and when the sap is gathered monday morning.

They do not in this respect suffer much loss. In other respects, they are called to make no more sacrifice by observing the sabbath than the people of N.E. do during the season of haying. We are now living more strictly in the Indian country among an Indian community than ever before. We are almost the only persons among a population of some 5 or 600 people who speak the English language. We have therefore a better opportunity to observe Indian manners and customs than heretofore, as well as to make proficiency in speaking the language.

Process of making sugar and skillful use of birch bark.

The process of making sugar from the (maple) sap is in general as that practiced elsewhere where this kind of sugar is make, and yet in some respects the modus operandi is very different. The sugar making season is the most an important event to the Indians every year. Every year about the middle of March the Indians, French and halfbreeds all leave the Islands for the sugar camps. As they move off in bodies from the La Pointe, sometimes in companies of 8, 10, 12 or 20 families, they make a very singular appearance.

Upon some pleasant morning about sunrise you will see these, by families, first perhaps a Frenchman with his horse team carrying his apuckuais for his lodge–provisions kettles, etc., and perhaps in addition some one or two of the [squaw?] helpers of his family. The next will be a dog train with two or three dogs with a similar load driven by some Indians. The next would be a similar train drawn by a man with a squaw pushing behind carrying a little child on her back and two or three little children trudging behind on foot. The next load in order might be a squaw drawn by dogs or a man upon a sled at each end. This forms about the variety that will be witnessed in the modes of conveyance. To see such a ([raucous?] company) [motley process?] moving off, and then listen to the Frenchmen whipping his horse, which from his hard fare is but poorly able to carry himself, and to hear the yelping of the dogs, the (crying of) the children, and the jabbering in french and Indian. And if you never saw the like before you have before you the loud and singular spectacle of the Indians going to the sugar bush.

“Frame of Lodge Used For Storage and Boiling Sap;” undated (Densmore Collection: Smithsonian)

One night they are obliged to camp out before they reach the place of making sugar. This however is counted no hardship the Indian carries his house with him. When they have made one days march it might when they come to a place where they wish to camp, all hands set to work to make to make a lodge. Some shovel away the snow another cut a few poles. Another cuts up some wood to make a fire. Another gets some pine, cedar or hemlock (boughs) to spread upon the ground for floor and carpet. By the time the snow is shoveled away the poles are ready, which the women set around in a circular form at the bottom–crossed at the top. These are covered with a few apuckuais, and while one or two are covering the putting up the house another is making a fire, & perhaps is spreading down the boughs. The blankets, provisions, etc. are then brought in the course of 20 or ½ an hour from the time they stop, the whole company are seated in their lodge around a comfortable fire, and if they are French men you will see them with their pipes in their mouths. After supper, when they have anything to eat, each one wraps himself in a blanket and is soon snoring asleep. The next day they are again under way and when they arrive at the sugar camp they live in their a lodge again till they have some time to build a more substantial (building) lodge for making sugar. A sugar camp is a large high lodge or a sort of a frame of poles covered with flagg and Birch apuckuais open at the top. In the center is a long fire with two rows of kettles suspended on wooden forks for boiling sap. As Robert (our hired man) sugar makes (the best kind of) sugar and does business upon rather a large scale in quite a systematic manner. I will describe his camp as a mode of procedure, as an illustration of the manner in which the best kind of sugar is made. His camp is some 25 or 30 feet square, made of a sort of frame of poles with a high roof open at the (top) the whole length coming down with in about (4 feet) of the ground. This frame is covered around the sides at the bottom with Flag apukuais. The outside and roof is covered with birch (bark) apukuais. Upon each side next to the wall are laid some raised poles, the whole length of the (lodge) wall. Upon these poles are laid some pine & cedar boughs. Upon these two platforms are places all the household furniture, bedding, etc. Here also they sleep at night. In the middle of the lodge is a long fire where he has two rows of kettles 16 in number for boiling sap. He has also a large trough, one end of it coming into the lodge holding several Barrels, as a sort of reservoir for sap, beside several barrels reserved for the same purpose. The sap when it is gathered is put into this trough and barrels, which are kept covered up to prevent the exposure of the sap to the wind and light and heat, as the sap when exposed sours very quick. For the same reason also when the sap and well the kettles are kept boiling night and day, as the sap kept in the best way will undergo some changes if it be not immediately boild. The sap after it is boild down to about the consistency of molases it is strained into a barrel through a wollen blanket. After standing 3 or 4 days to give it an opportunity to settle, some day, when the sap does not run very well, is then set aside for sugaring off. When two or 3 kettles are hung over the fire a small fire built directly under the bottom. A few quarts of molasses are then put into the kettles. When this is boiled enough to make sugar one kettle is taken off by Robert, by the side of which he sets down and begins to stir it with a small paddle stick. After stirring it a few moments it begins to grow all white, swells up with a peculiar tenacious kind of foam. Then it begins to grain and soon becomes hard like [?] Indian pudding. Then by a peculiar moulding for some time with a wooden large wooden spoon it becomes white as the nicest brown sugar and very clean, in this state, while it is yet warm, it is packed down into large birch bark mukoks made of holding from 50 to a hundred lbs.

Makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Ojibwe People’s Dictionary) Photo: Densmore Collection; Smithsonian

Makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Ojibwe People’s Dictionary) Photo: Densmore Collection; SmithsonianCertainly no sugar can be more cleaner than that made here, though it is not all the sugar that is made as nice. The Indians do not stop for all this long process of making sugar. Some of (their) sorup does not pass through anything in the shape of a strainer–much less is it left to stand and settle after straining, but is boiled down immediately into sugar, sticks, soot, dirt and all. Sometimes they strain their sorup through the meshes of their snow shoe, which is but little better than it would be to strain it through a ladder. Their sugar of course has rather a darker hue. The season for making sugar is the most industrious season in the whole year. If the season be favorable, every man wom and child is set to work. And the departments of labor are so various that every able bodied person can find something to do.

The British missionary John Williams describes the coconut on page 493 of his A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands (1837). (Wikimedia Commons)

The British missionary John Williams describes the coconut on page 493 of his A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands (1837). (Wikimedia Commons)In the business of making sugar also we have a striking illustration of the skillful and varied use the Indians make of birch bark. A few years since I was forcibly struck, in reading Williams missionary enterprises of the South Seas, with some annals of his in regard to the use of the cocoanut tree illustrated of the goodness and wisdom of God in so wonderfully providing for their condition and wants (of men). His remarks as near as I can recollect are in substance as follows. The cocoanut tree furnishes the native with timber to make his house, canoe, his fire and in short for most of the purposes for which they want wood. The fruit furnishes his most substantial article of food, and what is still more remarkable as illustrating that principle of compensation by which the Lord in his good providence suplies the want of one blessing by the bestowment of another to take its place. On the low islands their are no springs of water to supply the place of this. The native has but to climb the cocoanut tree growing near his door and pluckes the fruit where in each shall he find from ¼ a pint to a kind of a most agreeable drink to slake his thirst. His tree bearing fruit every month in year, fresh springs of water are supplied the growing upon the trees before his own door. Although the birch bark does not supply the same wants throughout to the Indian, yet they supply wants as numerous and in some respects nearly as important to their mode of living as does the cocoanut to the Inhabitants of the South Sea Islands.

Biskitenaagan: a sap bucket of folded birch bark (Ojibwe People’s Dictionary) Photo: Waugh Collection; Smithsonian

Biskitenaagan: a sap bucket of folded birch bark (Ojibwe People’s Dictionary) Photo: Waugh Collection; SmithsonianIt is with the bark he covers his house. With this bark he makes his canoe. What could the Indian do without his wigwam and his canoe? The first use (of the bark) we notice in the sugar making business what is called the piscatanagun, or vessel for catching sap in. The Indian is not to the expence or trouble of making troughs or procuring buckets to catch the sap at the trees. A piece of birch bark some 14 inches wide and 18 or 20 inches wide in the shape of a pane of glass by a peculiar fold at each end kept in place by a stitch of bark string makes a vessel for catching sap called a piskitenagun. These are light, cheap, easily made and with careful usage will last several years. When I first saw these vessels, it struck me as being the most skillful use of the bark I had seen. It contrasted so beautifully with the clumsy trough or the more expensive bucket I had seen used in N.E. This bark is not only used to catch the sap in but also to carry it in to the sugar camps, a substitute for pails, though lighter and much more convenient for this purpose than a pail.

In making a sap bucket bark of a more substantial kind is used than for the piskatanaguns. They made large at the bottom small at the top, to prevent the sap from spilling out by the motion of carrying. They are sewed up with bark the seams gummed and a hoop about the top to keep them in shape and a lid. But we are not yet done with the bark at the sugar bush. In boiling sap in the evening thin strips are rolled tight together, which is a good substitute for a candle. Every once in a little while the matron of the lodge may be seen with her little torch in hand walking around the fire taking a survey of her kettles. Lastly when the sugar is made it is finally deposited in large firmly wrought mukuks, which are made of bark. This however is not the end of bark. It is used for a variety of other purposes. Besides being a substitute in many cases for plates, [bearers & etc.?], it is upon birch bark that the most important events in history are recorded–National records–songs, & etc. are written in hieroglific characters (upon this article) and carefully preserved by many of the Indians.

And finally the most surprising use of bark of which I have heard or could conceive of, is before the acquaintance of the Indians with the whites, the bark was used as a substitute for kettles in cooking, not exactly for bake kettles but for (kettles for) boiling fish, potatoes, & etc. This fact we have from undoubted authority. Some of the Indians now living have used it for this purpose themselves, and many of them say their fathers tell them it was used by their ancestors before iron kettles were obtained from the whites. One kettle of bark however would not answer but for a single use.

Transcription note: Spelling and grammatical errors have been maintained except where ambiguous in the original text. Original struck out text has been maintained, when legible, and inserted text is shown in parentheses. Brackets indicate illegible or ambiguous text and are not part of the original nor are the bolded words and phrases, which were added to draw attention to the sidebars.

The original document is held by the Wisconsin Historical Society in the Wheeler Family Papers at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center in Ashland.

Reconstructing the “Martell” Delegation through Newspapers

November 2, 2013

Symbolic Petition of the Chippewa Chiefs: This pictographic petition was brought to Washington D.C. by a delegation of Ojibwe chiefs and their interpreter J.B. Martell. This one, representing the band of Chief Oshkaabewis, is the most famous, but their were several others copied from birch bark by Seth Eastman and published in the works of Henry Schoolcraft. For more, follow this link.

Henry Schoolcraft. William W. Warren. George Copway. These names are familiar to any scholar of mid-19th-century Ojibwe history. They are three of the most referenced historians of the era, and their works provide a great deal of historical material that is not available in any other written sources. Copway was Ojibwe, Warren was a mix-blood Ojibwe, and Schoolcraft was married to the granddaughter of the great Chequamegon chief Waabojiig, so each is seen, to some extent, as providing an insider’s point of view. This could lead one to conclude that when all three agree on something, it must be accurate. However, there is a danger in over-relying on these early historians in that we forget that they were often active participants in the history they recorded.

This point was made clear to me once again as I tried to sort out my lingering questions about the 1848-49 “Martell” Delegation to Washington. If you are a regular reader, you may remember that this delegation was the subject of the first post on this website. You may also remember from this post, that the group did not have money to get to Washington and had to reach out to the people they encountered along the way.

The goal of the Martell Delegation was to get the United States to cede back title to the lands surrounding the major Lake Superior Ojibwe villages. The Ojibwe had given this land up in the Treaty of 1842 with the guarantee that they could remain on it. However, by 1848 there were rumors of removal of all the bands east of the Mississippi to unceded land in Minnesota. That removal was eventually attempted, in 1850-51, in what is now called the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

The Martell Delegation remains a little-known part of the removal story, although the pictographs remain popular. Those petitions are remembered because they were published in Henry Schoolcrafts’ Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States (1851) along with the most accessible primary account of the delegation:

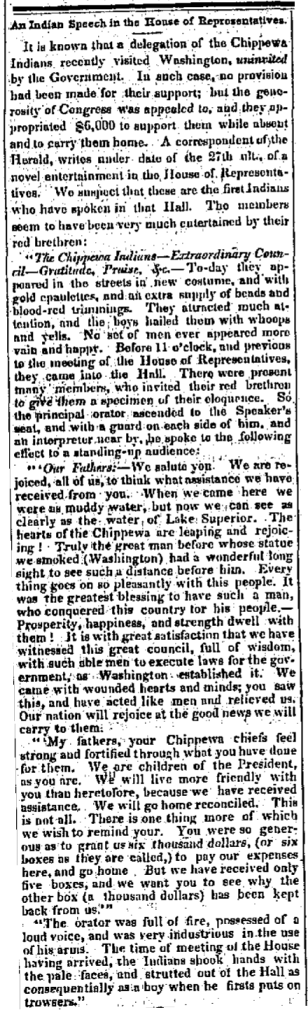

In the month of January, 1849, a delegation of eleven Chippewas, from Lake Superior, presented themselves at Washington, who, amid other matters not well digested in their minds, asked the government for a retrocession of some portion of the lands which the nation had formerly ceded to the United States, at a treaty concluded at Lapointe, in Lake Superior, in 1842. They were headed by Oshcabawiss, a chief from a part of the forest-country, called by them Monomonecau, on the head-waters of the River Wisconsin. Some minor chiefs accompanied them, together with a Sioux and two boisbrules, or half-breeds, from the Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The principal of the latter was a person called Martell, who appeared to be the master-spirit and prime mover of the visit, and of the motions of the entire party. His motives in originating and conducting the party, were questioned in letters and verbal representations from persons on the frontiers. He was freely pronounced an adventurer, and a person who had other objects to fulfil, of higher interest to himself than the advancement of the civilization and industry of the Indians. Yet these were the ostensible objects put forward, though it was known that he had exhibited the Indians in various parts of the Union for gain, and had set out with the purpose of carrying them, for the same object, to England. However this may be, much interest in, and sympathy for them, was excited. Officially, indeed, their object was blocked up. The party were not accredited by their local agent. They brought no letter from the acting Superintendent of Indian Affairs on that frontier. The journey had not been authorized in any manner by the department. It was, in fine, wholly voluntary, and the expenses of it had been defrayed, as already indicated, chiefly from contributions made by citizens on the way, and from the avails of their exhibitions in the towns through which they passed; in which, arrayed in their national costume, they exhibited their peculiar dances, and native implements of war and music. What was wanting, in addition to these sources, had been supplied by borrowing from individuals.

Martell, who acted as their conductor and interpreter, brought private letters from several persons to members of Congress and others, which procured respect. After a visit, protracted through seven or eight weeks, an act was passed by Congress to defray the expenses of the party, including the repayment of the sums borrowed of citizens, and sufficient to carry them back, with every requisite comfort, to their homes in the north-west. While in Washington, the presence of the party at private houses, at levees, and places of public resort, and at the halls of Congress, attracted much interest; and this was not a little heightened by their aptness in the native ceremonies, dancing, and their orderly conduct and easy manners, united to the attraction of their neat and well-preserved costume, which helped forward the object of their mission.

The visit, although it has been stated, from respectable sources, to have had its origin wholly in private motives, in the carrying out of which the natives were made to play the part of mere subordinates, was concluded in a manner which reflects the highest credit on the liberal feelings and sentiments of Congress. The plan of retrocession of territory, on which some of the natives expressed a wish to settle and adopt the modes of civilized life, appeared to want the sanction of the several states in which the lands asked for lie. No action upon it could therefore be well had, until the legislatures of these states could be consulted (pg. 414-416, pictographic plates follow).

I have always had trouble with Schoolcraft’s interpretation of these events. It wasn’t that I had evidence to contradict his argument, but rather that I had a hard time believing that all these chiefs would make so weighty a decision as to go to Washington simply because their interpreter was trying to get rich. The petitions asked for a permanent homeland in the traditional villages east of the Mississippi. This was the major political goal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe leadership at that time and would remain so in all the years leading up to 1854. Furthermore, chiefs continued to ask for, or go “uninvited” on, diplomatic missions to the president in the years that followed.

I explored some of this in the post about the pictograph, but a number of lingering questions remained:

What route did this group take to Washington?

Who was Major John Baptiste Martell?

Did he manipulate the chiefs into working for him, or was he working for them?

Was the Naaganab who went with this group the well-known Fond du Lac chief or the warrior from Lake Chetek with the same name?

Did any chiefs from the La Pointe band go?

Why was Martell criticized so much? Did he steal the money?

What became of Martell after the expedition?

How did the “Martell Expedition” of 1848-49 impact the Ojibwe removal of 1850-51?

Lacking access to the really good archives on this subject, I decided to focus on newspapers, and since this expedition received so much attention and publicity, this was a good choice. Enjoy:

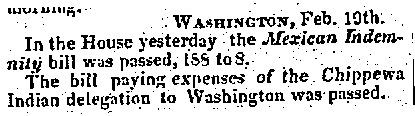

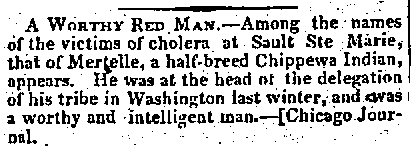

Indiana Palladium. Vevay, IN. Dec. 2, 1848

Capt. Seth Eastman of the U.S. Army took note of the delegation as it traveled down the Mississippi from Fort Snelling to St. Louis. Eastman, a famous painter of American Indians, copied the birch bark petitions for publication in the works of his collaborator Henry Schoolcraft. At least one St. Louis paper also noticed these unique pictographic documents.

Lafayette Courier. Lafayette, IN. Dec. 8, 1848.

Lafayette Courier. Lafayette, IN. Dec. 8, 1848.

The delegation made its way up the Ohio River to Cincinnati, where Gezhiiyaash’s illness led to a chance encounter with some Ohio Freemasons. I won’t repeat it here, but I covered this unusual story in this post from August.

At Cincinnati, they left the river and headed toward Columbus. Just east of that city, on the way to Pittsburgh, one of the Ojibwe men offered some sound advice to the women of Hartford, Ohio, but he received only ridicule in return.

Madison Weekly Courier. Madison, IN. Jan. 24, 1849

It’s unclear how quickly reports of the delegation came back to the Lake Superior country. William Warren’s letter to his cousin George, written in March after the delegation had already left Washington, still spoke of St. Louis:

William W. Warren (Wikimedia Images)

“…About Martells Chiefs. They were according to last accounts dancing the pipe dance at St. Louis. They have been making monkeys of themselves to fill the pockets of some cute Yankee who has got hold of them. Black bird returned from Cleveland where he caught scarlet fever and clap. He has behaved uncommon well since his return…” (Schenck, pg. 49)

From this letter, we learn that Blackbird, the La Pointe chief, was originally part of the group. In evaluating Warren’s critical tone, we must remember that he was working closely with the very government officials who withheld their permission. Of the La Pointe chiefs, Blackbird was probably the least accepting of American colonial power. However, we see in the obituary of Naaganab, Blackbird’s rival at the 1855 annuity payment, that the Fond du Lac chief was also there.

New York World. New York. July 22, 1894

Before finding this obituary, I had thought that the Naaganab who signed the petition was more likely the headman from Lake Chetek. Instead, this information suggests it was the more famous Fond du Lac chief. This matters because in 1848, Naaganab was considered the speaker for his cousin Zhingob, the leading chief at Fond du Lac. Blackbird, according to his son James, was the pipe carrier for Buffalo. While these chiefs had their differences with each other, it seems likely that they were representing their bands in an official capacity. This means that the support for this delegation was not only from “minor chiefs” as Schoolcraft described them, or “Martells Chiefs” as Warren did, from Lac du Flambeau and Michigan. I would argue that the presence of Blackbird and Naaganab suggests widespread support from the Lake Superior bands. I would guess that there was much discussion of the merits of a Washington delegation by Buffalo and others during the summer of 1848, and that the trip being a hasty money-making scheme by Martell seems much less likely.

Madison Daily Banner. Madison, IN. Jan. 3, 1849.

From Pittsburgh, the delegation made it to Philadelphia, and finally Washington. They attracted a lot of attention in the nation’s capital. Some of their adventures and trials: Oshkaabewis and his wife Pammawaygeonenoqua losing an infant child, the group hunting rabbits along the Potomac, and the chiefs taking over Congress, are included this post from March, so they aren’t repeated here.

Adams Sentinel. Gettysburg, PA. Feb. 5, 1849.

According to Ronald Satz, the delegation was received by both Congress and President Polk with “kindly feelings” and the expectation of “good treatment in the future” if they “behaved themselves (Satz 51).” Their petition was added to the Congressional Record, but the reservations were not granted at the time. However, Congress did take up the issue of paying for the debts accrued by the Ojibwe along the way.

George Copway (Wikimedia Commons)

Kah-Ge-Ga-Gah-Bowh (George Copway), a Mississauga Ojibwe and Methodist missionary, was the person “belonging to one of the Canada Bands of Chippewas,” who wrote the anti-Martell letter to Indian Commissioner William Medill. This is most likely the letter Schoolcraft referred to in 1851. In addition to being upset about the drinking, Copway was against reservations in Wisconsin. He wanted the government to create a huge pan-Indian colony at the headwaters of the Missouri River.

William Medill (Wikimedia Commons)

Iowa State Gazette. Burlington, IA. April 4, 1849

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Feb. 28, 1849.

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Feb. 28, 1849.

With $6000 (or did they only get $5000?), a substantial sum for the antebellum Federal Government, the group prepared to head back west with the ability to pay back their creditors.

It appears the chiefs returned to their villages by going back though the Great Lakes to Green Bay and then overland.

The Chippewa Delegation, who have been on a visit to see their “great fathers” in Washington, passed through this place on Saturday last, on their way to their homes near Lake Superior. From the accounts of the newspapers, they have been lionized during their whole journey, and particularly in Washington, where many presents were made them, among the most substantial of which was six boxed of silver ($6,000) to pay their expenses. They were loaded with presents, and we noticed one with a modern style trunk strapped to his back. They all looked well and in good spirits (qtd. in Paap, pg. 205).

Green Bay Gazette. April 4, 1849

So, it hardly seems that the Ojibwe chiefs returned to their villages feeling ripped off by their interpreter. Martell himself returned to the Soo, and found a community about to be ravaged by a epidemic of cholera.

Weekly Wisconsin. Milwaukee. Sep. 5, 1849.

Martell appears in the 1850 census on the record of those deceased in the past year. Whether he was a major in the Mexican War, whether he was in the United States or Canadian military, or whether it was even a real title, remains a mystery. His death record lists his birthplace as Minnesota, which probably connects him to the Martells of Red Lake and Red River, but little else is known about his early years. And while we can’t say for certain whether he led the group purely out of self-interest, or whether he genuinely supported the cause, John Baptiste Martell must be remembered as a key figure in the struggle for a permanent Ojibwe homeland in Wisconsin and Michigan. He didn’t live to see his fortieth birthday, but he made the 1848-49 Washington delegation possible.

So how do we sort all this out?

To refresh, my unanswered questions from the other posts about this delegation were:

1) What route did this group take to Washington?

2) Who was Major John Baptiste Martell?

3) Did he manipulate the chiefs into working for him, or was he working for them?

4) Was the Naaganab who went with this group the well-known Fond du Lac chief or the warrior from Lake Chetek with the same name?

5) Did any chiefs from the La Pointe band go?

6) Why was Martell criticized so much? Did he steal the money?

7) What became of Martell after the expedition?

8) How did the “Martell Expedition” of 1848-49 impact the Ojibwe removal of 1850-51?

We’ll start with the easiest and work our way to the hardest. We know that the primary route to Washington was down the Brule, St. Croix, and Mississippi to St. Louis, and from there up the Ohio. The return trip appears to have been via the Great Lakes.

We still don’t know how Martell became a major, but we do know what became of him after the diplomatic mission. He didn’t survive to see the end of 1849.

The Fond du Lac chief Naaganab, and the La Pointe chief Blackbird, were part of the group. This indicates that a wide swath of the Lake Superior Ojibwe leadership supported the delegation, and casts serious doubt on the notion that it was a few minor chiefs in Michigan manipulated by Martell.

Until further evidence surfaces, there is no reason to support Schoolcraft’s accusations toward Martell. Even though these allegations are seemingly validated by Warren and Copway, we need to remember how these three men fit into the story. Schoolcraft had moved to Washington D.C. by this point and was no longer Ojibwe agent, but he obviously supported the power of the Indian agents and favored the assimilation of his mother-in-law’s people. Copway and Warren also worked closely with the Government, and both supported removal as a way to separate the Ojibwe from the destructive influences of the encroaching white population. These views were completely opposed to what the chiefs were asking for: permanent reservations at the traditional villages. Because of this, we need to consider that Schoolcraft, Warren, and Copway would be negatively biased toward this group and its interpreter.

Finally there’s the question Howard Paap raises in Red Cliff, Wisconsin. How did this delegation impact the political developments of the early 1850s? In one sense the chiefs were clearly pleased with the results of the trip. They made many friends in Congress, in the media, and in several American cities. They came home smiling with gifts and money to spread to their people. However, they didn’t obtain their primary goal: reservations east of the Mississippi, and for this reason, the following statement in Schoolcraft’s account stands out:

The plan of retrocession of territory, on which some of the natives expressed a wish to settle and adopt the modes of civilized life, appeared to want the sanction of the several states in which the lands asked for lie. No action upon it could therefore be well had, until the legislatures of these states could be consulted.

“Kindly feelings” from President Polk didn’t mean much when Zachary Taylor and a new Whig administration were on the way in. Meanwhile, Congress and the media were so wrapped up in the national debate over slavery that they forgot all about the concerns of the Ojibwes of Lake Superior. This allowed a handful of Indian Department officials, corrupt traders, and a crooked, incompetent Minnesota Territorial governor named Alexander Ramsey to force a removal in 1850 that resulted in the deaths of 400 Ojibwe people in the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

It is hard to know how the chiefs felt about their 1848-49 diplomatic mission after Sandy Lake. Certainly their must have been a strong sense that they were betrayed and abandoned by a Government that had indicated it would support them, but the idea of bypassing the agents and territorial officials and going directly to the seat of government remained strong. Another, much more famous, “uninvited” delegation brought Buffalo and Oshogay to Washington in 1852, and ultimately the Federal Government did step in to grant the Ojibwe the reservations. Almost all of the chiefs who made the journey, or were shown in the pictographs, signed the Treaty of 1854 that made them.

Sources:

McClurken, James M., and Charles E. Cleland. Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights / James M. McClurken, Compiler ; with Charles E. Cleland … [et Al.]. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State UP, 2000. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Seth Eastman. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Collected and Prepared under the Direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per Act of Congress of March 3rd, 1847. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo, 1851. Print.

CAUTION: This translation was made using Google Translate by someone who neither speaks nor reads German. It should not be considered accurate by scholarly standards.

Americans love travelogues. From de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, to Twain’s Roughing It, to Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley, a few pages of a well-written travelogue by a random interloper can often help a reader picture a distant society more clearly than volumes of documents produced by actual members of the community. And while travel writers often misinterpret what they see, their works remain popular long into the future. When you think about it, this isn’t surprising. The genre is built on helping unfamiliar readers interpret a place that is different, whether by space or time, from the one they inhabit. The travel writer explains everything in a nice summary and doesn’t assume the reader knows the subject.

You can imagine, then, my excitement when I accidentally stumbled upon a largely-unknown and untranslated travelogue from 1852 that devotes several pages to to the greater Chequamegon region.

I was playing around on Google Books looking for variants of Chief Buffalo’s name from sources in the 1850s. Those of you who read regularly know that the 1850s were a decade of massive change in this area, and the subject of many of my posts. I was surprised to see one of the results come back in German. The passage clearly included the words Old Buffalo, Pezhickee, La Pointe, and Chippewa, but otherwise, nothing. I don’t speak any German, and I couldn’t decipher all the letters of the old German font.

Karl (Carl) Ritter von Scherzer (1821-1903) (Wikimedia Images)

The book was Reisen in Nordamerika in den Jahren 1852 und 1853 (Travels in North America in the years 1852 and 1853) by the Austrian travel writers Dr. Moritz Wagner and Dr. Carl Scherzer. These two men traveled throughout the world in the mid 19th-century and became well-known figures in Europe as writers, government officials, and scientists. In America, however, Reisen in Nordamerika never caught on. It rests in a handful of libraries, but as far as I can find, it has never been translated into English.

Chapter 21, From Ontonagon to the Mouth of the Bois-brule River, was the chapter I was most interested in. Over the course of a couple of weeks, I plugged paragraphs into Google Translate, about 50 pages worth.

Here is the result (with the caveat that it was e-translated, and I don’t actually know German). Normally I clog up my posts with analysis, but I prefer to let this one stand on its own. Enjoy:

XXI

From Ontonagon to the mouth of the Bois-brule River–Canoe ride to Magdalen Island–Porcupine Mountains–Camping in the open air–A dangerous canoe landing at night–A hospitable Jewish family–The island of La Pointe–The American Fur Company–The voyageurs or courriers de bois–Old Buffalo, the 90 year-old Chippewa chief–A schoolhouse and an examination–The Austrian Franciscan monk–Sunday mass and reflections on the Catholic missions–Continuing the journey by sail–Nous sommes degrades–A canoeman and apostle of temperance–Fond du lac–Sauvons-nous!

On September 15th, we were under a cloudless sky with the thermometer showing 37°F. In a birch canoe, we set out for Magdalene Island (La Pointe). Our intention was to drive up the great Lake Superior to its western end, then up the St. Louis and Savannah Rivers, to Sandy Lake on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. Our crew consisted of a young Frenchman of noble birth and education and a captain of the U.S. Navy. Four French Canadians were the leaders of the canoes. Their trustworthy, cheerful, sprightly, and fearless natures carried us so bravely against the thundering waves, that they probably could have even rowed us across the river Styx.

Upon embarkation, an argument broke out between passengers and crew over the issue of overloading the boat. It was only conditioned to hold our many pieces of baggage and the provisions to be acquired along the way. However, our mercenary pilot produced several bags and packages, for which he could be well paid, by carrying them Madeline Island as freight.

Shortly after our exit, the weather hit us and a strong north wind obliged us to pull to shore and make Irish camp, after we had only covered four English miles to the Attacas (Cranberry) Rive,r one of the numerous mountain streams that pour into Lake Superior. We brought enough food from Ontonagon to provide for us for approximately 14 days of travel. The settlers of La Pointe, which is the last point on the lake where whites live, provided for themselves only scanty provisions. A heavy bag of ship’s biscuit was at the end of one canoe, and a second sack contained tea, sugar, flour, and some rice. A small basket contained our cooking and dining utensils.

The captain believed that all these supplies would be unecessary because the bush and fishing would provide us with the richest delicacies. But already in the next lunch hour, when we caught sight of no wild fowl, he said that we must prepare the rice. It was delicious with sugar. Dry wood was collected and a merry flickering fire prepared. An iron kettle hung from birch branches crossed akimbo, and the water soon boiled and evaporated. The sea air was fresh, and the sun shone brightly. The noise of the oncoming waves sounded like martial music to the unfinished ear, so we longed for the peaceful quiet lake. The shore was flat and sandy, but the main attraction of the scenery was in the gigantic forest trees and the richness of their leafy ornaments.

At a quarter to 3 o’clock, we left the bivouac as there was no more wind, and by 3 o’clock, with our camp still visible, the water became weaker and weaker and soon showed tree and cloud upon its smooth surface. We passed the Porcupine Mountains, a mountain range made of trapp geological formation. We observed that some years ago, a large number of inexperienced speculators sunk shafts and made a great number of investments in anticipation of a rich copper discovery. Now everything is destroyed and deserted and only the green arbor vitae remain on the steep trap rocks.

Our night was pretty and serene, so we went uninterrupted until 1 o’clock in the morning. Our experienced boatmen did not trust the deceptive smoothness of the lake, however, and they uttered repeated fears that storms would interrupt our trip. It happens quite often that people who travel in late autumn for pleasure or necessity from Ontonagon to Magdalene Island, 70 miles away, are by sea storms prevented from travelling that geographically-small route for as many as 6 or 8 days.

Used to the life of the Indians in the primeval forests, for whom even in places of civilization prefer the green carpet under the open sky to the soft rug and closed room, the elements could not dampen the emotion of the paddlers of the canoe or force out the pleasure of the chase.* But for Europeans, all sense of romantic adventure is gone when in such a forest for days without protection from the heavy rain and without shelter from the cold eeriness for his shivering limbs.

(*We were accompanied on our trip throughout the lakes of western Canada by half-Indians who had paternal European blood in their veins. Yet so often, a situation would allow us to spend a night inside rather than outdoors, but they always asked us to choose to Irish camp outside with the Indians, who lived at the various places. Although one spoke excellent English, and they were both drawn more to the great American race, they thought, felt, and spoke—Indian!)

It is amazing the carelessness with which the camp is set near the sparks of the crackling fire. An overwhelming calm is needed to prevent frequent accidents, or even loss of human life, from falling on the brands. As we were getting ready to continue our journey early in the morning, we found the front part of our tent riddled with a myriad of flickering sparks.

16 September (50° Fahrenheit)*) Black River, seven miles past Presque Isle. Gradually the shore area becomes rolling hills around Black River Mountain, which is about 100 feet in height. Frequently, immense masses of rock protrude along the banks and make a sudden landing impossible. This difficulty to reach shore, which can stretch for several miles long, is why a competent captain will only risk a daring canoe crossing on a fairly calm lake.

(*We checked the thermometer regularly every morning at 7 o’clock, and when travel conditions allowed it, at noon and evening.)

At Little Girl’s Point, a name linked to a romantic legend, we prepared lunch from the unfinished bread from the day before. We had rice, tea, and the remains of the bread we brought from a bakery in Ontonagon from our first days.

In the afternoon, we met at a distance a canoe with two Indians and a traveler going in an easterly direction. We got close enough to ask some short questions in telegraph style. We asked, “Where do you go? How is the water in the St. Louis and Savannah River?”

We were answered in the same brevity that they were from Crow Wing going to Ontonagon, and that the rivers were almost dried from a month-long lack of rain.

The last information was of utmost importance to us for it changed, all of a sudden, the fibers of our entire itinerary. With the state of the rivers, we would have to do most of the 300-mile long route on foot which neither the advanced season of the year, nor the sandy steppes invited. If we had been able to extend our trip, we could have visited Itasca Lake, the cradle of the Mississippi, where only a few historically-impressive researchers and travelers have passed near: Pike, Cass, Schoolcraft, Nicollet, and to our knowledge, no Austrian.

However, this was impossible considering our lack of necessary academic preparation and in consideration of the economy of our travel plan. We do not like the error, we would almost say vice, of so many travelers who rush in hasty discontent, supported by modern transport, through wonderful parts of creation without gaining any knowledge of the land’s physical history and the fate of its inhabitants.*

(*We were told here recently of such a German tourist who traveled through Mexico in only a fortnight– i.e. 6 days from Veracruz to the capital and 6 days back with only two days in the capital!)

While driving, the boatmen sang alternately. They were, for the most part, frivolous love songs and not of the least philological or ethnographic interest.

After 2 o’clock, we passed the rocks of the Montreal River. They run for about six miles with a long drag reaching up to an altitude of 100 feet. There are layers of shale and red sandstone, all of which run east to west. By weathering, they have obtained such a dyed-painting appearance, that you can see in their marbled colors something resembling a washed-out image.

The Montreal* is a major tributary of Lake Superior. About 300 steps up from where it empties into the lake, it forms a very pretty waterfall surrounded by an impressive pool. Rugged cliffs form the 80’ falls over a vertical sandstone layer and form a lovely valley. The width of the Montreal is 10’, and it also forms the border between the states of Michigan and Wisconsin.

(*Indian: Ka-wa’-si-gi-nong sepi, the white flowing falls.)

We stayed in this cute little bay for over an hour as our frail canoes had begun to take on a questionable amount of water as the result of some wicked stone wounds.

Up from Montreal River heading towards La Pointe, the earlier red sandstone formation starts again, and the rich shaded hills and rugged cliffs disappear suddenly. Around 6 o’clock, we rested for half an hour at the mouth of the Bad River of Lake Superior. We quickly prepared our evening snack as the possibility of reaching Magdalene Island that same night was still in contention.

Across from us, on the western shore of Bad River*, we saw Indians by a warm fire. One of the boatmen suspected they’d come back from catching fish, and he called in a loud voice across the river asking if they wanted to come over and sell us some. We took their response, and soon shy Indian women (squaws) appeared. Lacking a male, they dreaded to get involved in trading with Whites, and did not like the return we offered.

(*On Bad River, a Methodist Mission was founded in 1841. It consists of the missionary, his wife, and a female teacher. Their sphere of influence is limited to dispensing divine teaching only to those wandering tribes of Chippewa Indians that come here every year during the season of fishing, to divest the birch tree of its bark, and to build it into a shelter).

A part of our nightly trip was spent fantastically in blissful contemplation of the wonders above us and next to us. Night sent the cool fragrance of the forest to our lonely rocking boat, and the sky was studded with stars that sparkled through the green branches of the woods. Soon, luminous insects appeared on the tops of the trees in equally brilliant bouquets.

At 11 o’clock at night, we saw a magnificent aurora borealis, which left such a bright scent upon the dark blue sky. However, the theater soon changed scene, and a fierce south wind moved in incredibly fast. What had just been a quietly slumbering lake, as if inhabited by underwater ghosts, struck the alarm and suddenly tumultuous waves approached the boat. With the faster waves wanting to forestall the slower, a raging tumult arose resembling the dirt thrown up by great wagon wheels.

We were directly in the middle of that powerful watery surface, about one and one half miles from the mainland and from the nearest south bank of the island. It would have been of no advantage to reverse course as it required no more time to reach the island as to go back. At the outbreak of this dangerous storm, our boatmen were still determined to reach La Pointe.

But when several times the beating waves began to fill our boat from all sides with water, the situation became much more serious. As if to increase our misery, at almost the same moment a darkness concealed the sky and gloomy clouds veiled the stars and northern lights, and with them went our cheerful countenance.

Now singing, our boatmen spoke with anxious gestures and an unintelligible patois to our fellow traveler. The captain said jokingly, that they took counsel to see who should be thrown in the water first should the danger increase. We replied in a like manner that it was never our desire to be first and that we felt the captain should keep that honor. Fortunately, all our concern soon ended as we landed at La Pointe (Chegoimegon).

To be continued…

CAUTION: This translation was made using Google Translate by someone who neither speaks nor reads German. It should not be considered accurate by scholarly standards.

Oshogay

August 12, 2013

At the most recent count, Chief Buffalo is mentioned in over two-thirds of the posts here on Chequamegon History. That’s the most of anyone listed so far in the People Index. While there are more Buffalo posts on the way, I also want to draw attention to some of the lesser known leaders of the La Pointe Band. So, look for upcoming posts about Dagwagaane (Tagwagane), Mizay, Blackbird, Waabojiig, Andeg-wiiyas, and others. I want to start, however, with Oshogay, the young speaker who traveled to Washington with Buffalo in 1852 only to die the next year before the treaty he was seeking could be negotiated.

I debated whether to do this post, since I don’t know a lot about Oshogay. I don’t know for sure what his name means, so I don’t know how to spell or pronounce it correctly (in the sources you see Oshogay, O-sho-ga, Osh-a-ga, Oshaga, Ozhoge, etc.). In fact, I don’t even know how many people he is. There were at least four men with that name among the Lake Superior Ojibwe between 1800 and 1860, so much like with the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search, the key to getting Oshogay’s history right is dependent on separating his story from those who share his name.

In the end, I felt that challenge was worth a post in its own right, so here it is.

Getting Started

According to his gravestone, Oshogay was 51 when he died at La Pointe in 1853. That would put his birth around 1802. However, the Ojibwe did not track their birthdays in those days, so that should not be considered absolutely precise. He was considered a young man of the La Pointe Band at the time of his death. In my mind, the easiest way to sort out the information is going to be to lay it out chronologically. Here it goes:

1) Henry Schoolcraft, United States Indian Agent at Sault Ste. Marie, recorded the following on July 19, 1828:

Oshogay (the Osprey), solicited provisions to return home. This young man had been sent down to deliver a speech from his father, Kabamappa, of the river St. Croix, in which he regretted his inability to come in person. The father had first attracted my notice at the treaty of Prairie du Chien, and afterwards received a small medal, by my recommendation, from the Commissioners at Fond du Lac. He appeared to consider himself under obligations to renew the assurance of his friendship, and this, with the hope of receiving some presents, appeared to constitute the object of his son’s mission, who conducted himself with more modesty and timidity before me than prudence afterwards; for, by extending his visit to Drummond Island, where both he and his father were unknown, he got nothing, and forfeited the right to claim anything for himself on his return here.

I sent, however, in his charge, a present of goods of small amount, to be delivered to his father, who has not countenanced his foreign visit.

Oshogay is a “young man.” A birth year of 1802 would make him 26. He is part of Gaa-bimabi’s (Kabamappa’s) village in the upper St. Croix country.

2) In June of 1834, Edmund Ely and W. T. Boutwell, two missionaries, traveled from Fond du Lac (today’s Fond du Lac Reservation near Cloquet) down the St. Croix to Yellow Lake (near today’s Webster, WI) to meet with other missionaries. As they left Gaa-bimabi’s (Kabamappa’s) village near the head of the St. Croix and reached the Namekagon River on June 28th, they were looking for someone to guide them the rest of the way. An old Ojibwe man, who Boutwell had met before at La Pointe, and his son offered to help. The man fed the missionaries fish and hunted for them while they camped a full day at the mouth of the Namekagon since the 29th was a Sunday and they refused to travel on the Sabbath. On Monday the 30th, the reembarked, and Ely recorded in his journal:

The man, whose name is “Ozhoge,” and his son embarked with us about 1/2 past 9 °clk a.m. The old man in the bow and myself steering. We run the rapids safely. At half past one P. M. arrived at the mouth of Yellow River…

Ozhoge is an “old man” in 1834, so he couldn’t have been born in 1802. He is staying on the Namekagon River in the upper St. Croix country between Gaa-bimabi and the Yellow Lake Band. He had recently spent time at La Pointe.

3) Ely’s stay on the St. Croix that summer was brief. He was stationed at Fond du Lac until he eventually wore out his welcome there. In the 1840s, he would be stationed at Pokegama, lower on the St. Croix. During these years, he makes multiple references to a man named Ozhogens (a diminutive of Ozhoge). Ozhogens is always found above Yellow River on the upper St. Croix.

Ozhogens has a name that may imply someone older (possibly a father or other relative) lives nearby with the name Ozhoge. He seems to live in the upper St. Croix country. A birth year of 1802 would put him in his forties, which is plausible.

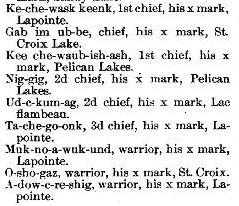

Ke-che-wask keenk (Gichi-weshki) is Chief Buffalo. Gab-im-ub-be (Gaa-bimabi) was the chief Schoolcraft identified as the father of Oshogay. Ja-che-go-onk was a son of Chief Buffalo.

4) On August 2, 1847, the United States and the Mississippi and Lake Superior Ojibwe concluded a treaty at Fond du Lac. The US Government wanted Ojibwe land along the nation’s border with the Dakota Sioux, so it could remove the Ho-Chunk people from Wisconsin to Minnesota.

Among the signatures, we find O-sho-gaz, a warrior from St. Croix. This would seem to be the Ozhogens we meet in Ely.

Here O-sho-gaz is clearly identified as being from St. Croix. His identification as a warrior would probably indicate that he is a relatively young man. The fact that his signature is squeezed in the middle of the names of members of the La Pointe Band may or may not be significant. The signatures on the 1847 Treaty are not officially grouped by band, but they tend to cluster as such.

5) In 1848 and 1849 George P. Warren operated the fur post at Chippewa Falls and kept a log that has been transcribed and digitized by the University of Wisconsin Eau Claire. He makes several transactions with a man named Oshogay, and at one point seems to have him employed in his business. His age isn’t indicated, but the amount of furs he brings in suggests that he is the head of a small band or large family. There were multiple Ojibwe villages on the Chippewa River at that time, including at Rice Lake and Lake Shatac (Chetek). The United States Government treated with them as satellite villages of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band.

Based on where he lives, this Oshogay might not be the same person as the one described above.

6) In December 1850, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in the case Oshoga vs. The State of Wisconsin, that there were a number of irregularities in the trial that convicted “Oshoga, an Indian of the Chippewa Nation” of murder. The court reversed the decision of the St. Croix County circuit court. I’ve found surprisingly little about this case, though that part of Wisconsin was growing very violent in the 1840s as white lumbermen and liquor salesmen were flooding the country.

Pg 56 of Containing cases decided from the December term, 1850, until the organization of the separate Supreme Court in 1853: Volume 3 of Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Wisconsin: With Tables of the Cases and Principal Matters, and the Rules of the Several Courts in Force Since 1838, Wisconsin. Supreme Court Authors: Wisconsin. Supreme Court, Silas Uriah Pinney (Google Books).

The man killed, Alexander Livingston, was a liquor dealer himself.

Alexander Livingston, a man who in youth had had excellent advantages, became himself a dealer in whisky, at the mouth of Wolf creek, in a drunken melee in his own store was shot and killed by Robido, a half-breed. Robido was arrested but managed to escape justice.

~From Fifty Years in the Northwest by W.H.C Folsom

Several pages later, Folsom writes:

At the mouth of Wolf creek, in the extreme northwestern section of this town, J. R. Brown had a trading house in the ’30s, and Louis Roberts in the ’40s. At this place Alex. Livingston, another trader, was killed by Indians in 1849. Livingston had built him a comfortable home, which he made a stopping place for the weary traveler, whom he fed on wild rice, maple sugar, venison, bear meat, muskrats, wild fowl and flour bread, all decently prepared by his Indian wife. Mr. Livingston was killed by an Indian in 1849.

Folsom makes no mention of Oshoga, and I haven’t found anything else on what happened to him or Robido (Robideaux?).

It’s hard to say if this Oshoga is the Ozhogen’s of Ely’s journals or the Oshogay of Warren’s. Wolf Creek is on the St. Croix, but it’s not far from the Chippewa River country either, and the Oshogay of Warren seems to have covered a lot of ground in the fur trade. Warren’s journal, linked in #4, contains a similar story of a killing and “frontier justice” leading to lynch mobs against the Ojibwe. To escape the violence and overcrowding, many Ojibwe from that part of the country started to relocate to Fond du Lac, Lac Courte Oreilles, or La Pointe/Bad River. La Pointe is also where we find the next mention of Oshogay.

7) From 1851 to 1853, a new voice emerged loudly from the La Pointe Band in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. It was that of Buffalo’s speaker Oshogay (or O-sho-ga), and he spoke out strongly against Indian Agent John Watrous’ handling of the Sandy Lake payments (see this post) and against Watrous’ continued demands for removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. There are a number of documents with Oshogay’s name on them, and I won’t mention all of them, but I recommend Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren and Howard Paap’s Red Cliff, Wisconsin as two places to get started.

Chief Buffalo was known as a great speaker, but he was nearing the end of his life, and it was the younger chief who was speaking on behalf of the band more and more. Oshogay represented Buffalo in St. Paul, co-wrote a number of letters with him, and most famously, did most of the talking when the two chiefs went to Washington D.C. in the spring of 1852 (at least according to Benjamin Armstrong’s memoir). A number of secondary sources suggest that Oshogay was Buffalo’s son or son-in-law, but I’ve yet to see these claims backed up with an original document. However, all the documents that identify by band, say this Oshogay was from La Pointe.

The Wisconsin Historical Society has digitized four petitions drafted in the fall of 1851 and winter of 1852. The petitions are from several chiefs, mostly of the La Pointe and Lac Courte Oreilles/Chippewa River bands, calling for the removal of John Watrous as Indian Agent. The content of the petitions deserves its own post, so for now we’ll only look at the signatures.

November 6, 1851 Letter from 30 chiefs and headmen to Luke Lea, Commissioner of Indian Affairs: Multiple villages are represented here, roughly grouped by band. Kijiueshki (Buffalo), Jejigwaig (Buffalo’s son), Kishhitauag (“Cut Ear” also associated with the Ontonagon Band), Misai (“Lawyerfish”), Oshkinaue (“Youth”), Aitauigizhik (“Each Side of the Sky”), Medueguon, and Makudeuakuat (“Black Cloud”) are all known members of the La Pointe Band. Before the 1850s, Kabemabe (Gaa-bimabi) and Ozhoge were associated with the villages of the Upper St. Croix.

November 8, 1851, Letter from the Chiefs and Headmen of Chippeway River, Lac Coutereille, Puk-wa-none, Long Lake, and Lac Shatac to Alexander Ramsey, Superintendent of Indian Affairs: This letter was written from Sandy Lake two days after the one above it was written from La Pointe. O-sho-gay the warrior from Lac Shatac (Lake Chetek) can’t be the same person as Ozhoge the chief unless he had some kind of airplane or helicopter back in 1851.

Undated (Jan. 1852?) petition to “Our Great Father”: This Oshoga is clearly the one from Lake Chetek (Chippewa River).

Undated (Jan. 1852?) petition: These men are all associated with the La Pointe Band. Osho-gay is their Speaker.

In the early 1850s, we clearly have two different men named Oshogay involved in the politics of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. One is a young warrior from the Chippewa River country, and the other is a rising leader among the La Pointe Band.

Washington Delegation July 22, 1852 This engraving of the 1852 delegation led by Buffalo and Oshogay appeared in Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians. Look for an upcoming post dedicated to this image.

8) In the winter of 1853-1854, a smallpox epidemic ripped through La Pointe and claimed the lives of a number of its residents including that of Oshogay. It had appeared that Buffalo was grooming him to take over leadership of the La Pointe Band, but his tragic death left a leadership vacuum after the establishment of reservations and the death of Buffalo in 1855.

Oshogay’s death is marked in a number of sources including the gravestone at the top of this post. The following account comes from Richard E. Morse, an observer of the 1855 annuity payments at La Pointe:

The Chippewas, during the past few years, have suffered extensively, and many of them died, with the small pox. Chief O-SHO-GA died of this disease in 1854. The Agent caused a suitable tomb-stone to be erected at his grave, in La Pointe. He was a young chief, of rare promise and merit; he also stood high in the affections of his people.

Later, Morse records a speech by Ja-be-ge-zhick or “Hole in the Sky,” a young Ojibwe man from the Bad River Mission who had converted to Christianity and dressed in “American style.” Jabegezhick speaks out strongly to the American officials against the assembled chiefs:

…I am glad you have seen us, and have seen the folly of our chiefs; it may give you a general idea of their transactions. By the papers you have made out for the chiefs to sign, you can judge of their ability to do business for us. We had but one man among us, capable of doing business for the Chippewa nation; that man was O-SHO-GA, now dead and our nation now mourns. (O-SHO-GA was a young chief of great merit and much promise; he died of small-pox, February 1854). Since his death, we have lost all our faith in the balance of our chiefs…

This O-sho-ga is the young chief, associated with the La Pointe Band, who went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852.

9) In 1878, “Old Oshaga” received three dollars for a lynx bounty in Chippewa County.

Report of the Wisconsin Office of the Secretary of State, 1878; pg. 94 (Google Books)

It seems quite possible that Old Oshaga is the young man that worked with George Warren in the 1840s and the warrior from Lake Chetek who signed the petitions against Agent Watrous in the 1850s.

10) In 1880, a delegation of Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, and Lac du Flambeau chiefs visited Washington D.C. I will get into their purpose in a future post, but for now, I will mention that the chiefs were older men who would have been around in the 1840s and ’50s. One of them is named Oshogay. The challenge is figuring out which one.

Ojibwe Delegation c. 1880 by Charles M. Bell. [Identifying information from the Smithsonian] Studio portrait of Anishinaabe Delegation posed in front of a backdrop. Sitting, left to right: Edawigijig; Kis-ki-ta-wag; Wadwaiasoug (on floor); Akewainzee (center); Oshawashkogijig; Nijogijig; Oshoga. Back row (order unknown); Wasigwanabi; Ogimagijig; and four unidentified men (possibly Frank Briggs, top center, and Benjamin Green Armstrong, top right). The men wear European-style suit jackets and pants; one man wears a peace medal, some wear beaded sashes or bags or hold pipes and other props.(Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian).

- Upper row reading from the left.

- 1. Vincent Conyer- Interpreter 1,2,4,5 ?, includes Wasigwanabi and Ogimagijig

- 2. Vincent Roy Jr.

- 3. Dr. I. L. Mahan, Indian Agent Frank Briggs

- 4. No Name Given

- 5. Geo P. Warren (Born at LaPointe- civil war vet.

- 6. Thad Thayer Benjamin Armstrong

- Lower row

- 1. Messenger Edawigijig

- 2. Na-ga-nab (head chief of all Chippewas) Kis-ki-ta-wag

- 3. Moses White, father of Jim White Waswaisoug

- 4. No Name Given Akewainzee

- 5. Osho’gay- head speaker Oshawashkogijig or Oshoga

- 6. Bay’-qua-as’ (head chief of La Corrd Oreilles, 7 ft. tall) Nijogijig or Oshawashkogijig

- 7. No name given Oshoga or Nijogijig

The Smithsonian lists Oshoga last, so that would mean he is the man sitting in the chair at the far right. However, it doesn’t specify who the man seated on the right on the floor is, so it’s also possible that he’s their Oshoga. If the latter is true, that’s also who the unknown writer of the library caption identified as Osho’gay. Whoever he is in the picture, it seems very possible that this is the same man as “Old Oshaga” from number 9.

11) There is one more document I’d like to include, although it doesn’t mention any of the people we’ve discussed so far, it may be of interest to someone reading this post. It mentions a man named Oshogay who was born before 1860 (albeit not long before).

For decades after 1854, many of the Lake Superior Ojibwe continued to live off of the reservations created in the Treaty of La Pointe. This was especially true in the St. Croix region where no reservation was created at all. In the 1910s, the Government set out to document where various Ojibwe families were living and what tribal rights they had. This process led to the creation of the St. Croix and Mole Lake reservations. In 1915, we find 64-year-old Oshogay and his family living in Randall, Wisconsin which may suggest a connection to the St. Croix Oshogays. As with number 6 above, this creates some ambiguity because he is listed as enrolled at Lac Courte Oreilles, which implies a connection to the Chippewa River Oshogay. For now, I leave this investigation up to someone else, but I’ll leave it here for interest.

United States. Congress. House. Committee on Indian Affairs. Indian Appropriation Bill: Supplemental Hearings Before a Subcommittee. 1919 (Google Books).

This is not any of the Oshogays discussed so far, but it could be a relative of any or all of them.

In the final analysis

These eleven documents mention at least four men named Oshogay living in northern Wisconsin between 1800 and 1860. Edmund Ely met an old man named Oshogay in 1834. He is one. A 64-year old man, a child in the 1850s, was listed on the roster of “St. Croix Indians.” He is another. I believe the warrior from Lake Chetek who traded with George Warren in the 1840s could be one of the chiefs who went to Washington in 1880. He may also be the one who was falsely accused of killing Alexander Livingston. Of these three men, none are the Oshogay who went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852.

That leaves us with the last mystery. Is Ozhogens, the young son of the St. Croix chief Gaa-bimabi, the orator from La Pointe who played such a prominent role in the politics of the early 1850s? I don’t have a smoking gun, but I feel the circumstantial evidence strongly suggests he is. If that’s the case, it explains why those who’ve looked for his early history in the La Pointe Band have come up empty.

However, important questions remain unanswered. What was his connection to Buffalo? If he was from St. Croix, how was he able to gain such a prominent role in the La Pointe Band, and why did he relocate to La Pointe anyway? I have my suspicions for each of these questions, but no solid evidence. If you do, please let me know, and we’ll continue to shed light on this underappreciated Ojibwe leader.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892. Print.

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Folsom, William H. C., and E. E. Edwards. Fifty Years in the Northwest. St. Paul: Pioneer, 1888. Print.

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 12 August 2013. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1995. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Redix, Erik M. “The Murder of Joe White: Ojibwe Leadership and Colonialism in Wisconsin.” Diss. University of Minnesota, 2012. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. The Voice of the Crane Echoes Afar: The Sociopolitical Organization of the Lake Superior Ojibwa, 1640-1855. New York: Garland Pub., 1997. Print.

———–William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers: With Brief Notices of Passing Events, Facts, and Opinions, A.D. 1812 to A.D. 1842. Philadelphia, [Pa.: Lippincott, Grambo and, 1851. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Who doesn’t love a good mystery?

In my continuing goal to actually add original archival research to this site, rather than always mooching off the labors of others, I present to you another document from the Wheeler Family Papers. Last week, I popped over to the Wisconsin Historical Society collections at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center in Ashland, and brought back some great stuff. Unlike the somber Sandy Lake letters I published July 11th, this first new document is a mysterious (and often hilarious) journal from 1843 and 1844.

It was in the Wheeler papers, but it was neither written by nor for one of the Wheelers. There is no name on it to indicate an author, and despite a year of entries, very little to indicate his occupation (unless he was a weatherman). He starts in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, bound for Fond du Lac, Minnesota–though neither was a state yet. Our guy reaches Lake Superior at a time of great change. The Ojibwe have just ceded the land in the Treaty of 1842, commercial traffic is beginning to start on Lake Superior, and the old fur-trade economy is dying out.

Our guy doesn’t seem to be a native of this area. He’s not married. He doesn’t seem to be strongly connected to the fur trade. If he works for the government, he isn’t very powerful. He is definitely not a missionary. He doesn’t seem to be a land speculator or anything like that.

Who is he, and why did he come here? I have some hunches, but nothing solid. Read it and let me know what you think.

1843

Aug. 24th 1843. left Taycheedah for Milwaukie on my route to Lake Superior, drove to Cases[?] in Fond du Lac

25th Drove to Cases on Milwaukie road, commenced rowing before we arrived, and we put up for the night.

26th Started in the rain, drove to Vinydans[?], rain all the time. wet my carpet bag and clothes—we put out 12 O’clock m. took clothes out of my traveling bag and dried them.

27th sunday Left early in the morning. arrived at Milwaukie at 12 O clock M. stayed at the Fountain house, had good fun.

Arch Rock, Mackinac Island (Jeffness upload to Wikimedia Commons CC)

28th Purchased provisions and other articles of outfit and embarked aboard the Steamboat Chesapeake for Mackinac 9 O’clock P. M. had a pleasant time.

30th Arrived at Mackinac 6 O’clock A.M. put up at Mr. Wescott’s had excellent fare and good company, charges reasonable. four Thousand Indian men encamped on the Island for Payment—very warm weather—Slept with windows raised, and uncomfortably warm. There are a few white families, but the mass of the people are a motley crowd “from snowy white to sooty[?],” I visited the curiosities, the old fort Holmes, the sugar loaf rock the arched rock—heard some good stories well told by Mr. Wescott and a gentleman from Philadelphia.

Sept 4th Left Mackinac on board the Steamer Gen. Scott 8 O’clock A. M. arrived at Sault St, Marie same night 6 O’clock—very pleasant weather. gardens look well. Put up at Johnsons. had good fare fish eggs fowls and garden vegetables.

7th Embarked on board the Brig John Jacob Astor for La Pointe. Sailed fifty miles. at midnight the wind shifted suddenly into the N.W. and blew a hurricane and we were obliged to run back into the St. Marie’s river, and lay there at Pine Point until Sunday.

10th when we best[?] out of the river, and proceeding on

1843

Sept 11th Monday heading against hard wind all day—

makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Photo: Smithsonian Institution; Definition: Ojibwe People’s Dictionary).

makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Photo: Smithsonian Institution; Definition: Ojibwe People’s Dictionary).12th Warm cloudless brilliant morning, a perfect calm—10 O’clock fair wind, and with every sail our vessel plows the deep, with majesty.

13th cloudy—fair wind, we arrive at La Pointe 9 O’clock P.M. when a cannon fired from on board the vessel announced our arrival.