Edwin Ellis Incidents: Number VII

April 9, 2023

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Originally published in the August 25th, 1877, issue of The Ashland Press. Transcribed with permission from Ashland Narratives by K. Wallin and published in 2013 by Straddle Creek Co.

… continued from Number VI.

Plat of Prentice’s Addition to Ashland:

“It is in this addition, that, the Chippewa River and the St. Croix Indian trails reach the Bay.”

My Dear Press: – Recollections of Ashland which should forget to mention Martin Roehm, would leave out a material part – in truth a connecting link in the “chain of events.” He came to the Bay in the summer of 1856 – a hearty industrious young man, not many years from the “Fader Land.” He pre-empted a quarter section of land near the town site – which he still owns. He was not long in discovering the worth and beauty of a comely young widow, who, like himself, had left the “Fader Land” to improve her worldly condition. – After a somewhat lengthy courtship, they were married by “Esquire Bell” in their own home. The ruins of the house may be seen in Prentice’s Addition on the flats between “town” and the mouth of Fish Creek. The bride herself cooked with her own hands the marriage feast, while the guests were gathering. The ceremony was concluded by a grand gallopade, the music being under the direction of that master of the Terpsichorean art, Conrad Goeltz, assisted by his brother Adam, himself a master of the art.

Martin and his worthy wife still live in Ashland, having witnessed and participated in its varied fortunes for more than twenty years. They may be said to form the connecting link between the Old and New Ashland; for when all others had been, by the force of circumstance, compelled to abandon their homes, they alone remained “monarchs of all they surveyed.” They were in possession of an improved estate in their beautiful valley of Marengo twelve miles from Ashland. This was their favorite winter retreat; while upon the shores of the bay their palaces exceeded in number the residences of the richest kings of the old world. For years they were sovereigns alone, in possession of territory rivaling in extent some of the Kingdoms of Europe.

Their herds of cattle increased year by year and in time patriarchal style, were driven from one part of the vast estate to another, as the necessities of forage might require.

And now, although the revival of Ashland has somewhat restricted the extent of Martin’s possessions, he still owns a valuable herd of cows, and finds a sure source of revenue in the milk supply of Ashland, to the mutual satisfaction of his patrons and himself. His experiments have shown that our soil and climate are adapted to cattle raising and dairy purposes.

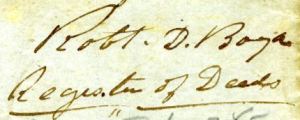

Robert D. Boyd, unknown to most of the present generation, came to Ashland in 1855. He was a native of the island of Mackinac – the son of an Indian Agent there stationed. His father was connected by marriage with a distinguished ex-President, to whom he owed his appointment. Rob’t D. as the report was, had, from the effects of a sudden outbreak of passion been guilty of a high crime, and to escape the penalty of the law, had fled to Lake Superior – then almost inaccessible – and safe from invasions of sheriffs and wicked men of that sort. At La Pointe he married a French mixed blood girl by the name of Cadotte, by whom he had several children. Except when under the influence of liquor, his conduct was good and his manner gentlemanly and polite. When partially intoxicated he was thought to be somewhat dangerous if not desperate.

Detail of settlement at Boyd Creek from Augustus Barber’s 1855 survey:

“There is a house in the NE quarter and another in the SE quarter of Section 25.”

He laid claim to a piece of land on the west side of the bay opposite to Ashland, of which a plat was made, to which he gave the name of “Menard,” in memory of the lamented French Jesuit Priest, who, according to tradition, labored for a while at an Indian village then located at this spot, – the point where the old St. Croix Indian trail reached the water of the Great Lake, and which in early years was a well beaten path – but now deserted. No traces of the village are now visible. The storms of nearly two hundred and fifty winters have obliterated all traces, of what from its position, must have been an important point among the Ojibwas of the northwest. According to the tradition, Father Menard left the bay for a missionary tour inland, from which he never returned and no trace of him was ever found.

La Pointe County Deeds Book A Page 577:

Plat of Mesnard

Surveyed, certified, and recorded in 1857 by Edward L. Baker, as power of attorney for Thomas H. Hogan of La Pointe:

“the SE¼ of the SW¼, the SW¼ of the SE¼, and Lot 3 in Section 24, and Lots 1 & 2 and the NE¼ of the NW¼ and west½ half of the NW¼ of Section 25, all in Township 48 North of Range 5 West of the 4th principal meridian of the State of Wisconsin“

Boyd erected a house in 1857 in the western part of Beaser’s Division which still stands, but unoccupied.

Wisconsin Representative Asaph Whittlesey also wrote about this tragedy.

In the latter part of 1857 he became unusually dispirited; his drunken sprees became frequent and long continued; and he was often under arrest for his disorderly and quarrelsome conduct. Finally in January 1858 he fell into a drunken debauch of several days duration. He was then living in the old log cabin on Main Street – Mr. Whittlesey’s first house – with one bachelor companion by the name of Cross. Having passed the night in drunken carousals, in the early morning – irritated by some real or imaginary insult from Cross – he approached the latter with a drawn butcher knife in his hand, holding it up in a threatening manner, as if about to strike. Cross drew a revolver and fired – two balls passed into the chest – one entering the heart. Boyd fell and in five minutes had breathed his last. This tragic event produced a profound sensation in our little community. A coroner’s inquest was held by Asaph Whittlesey, then a justice of the peace, – and although the evidence seemed to show that Cross might have retreated and saved himself without taking Boyd’s life, still Cross was judged by the jury to have acted in self-defense and was acquitted, Boyd’s known desperate character doubtless contributed to this result.

Boyd’s wife had died some years before, and several children were left orphans; and the writer will always carry in his mind the affecting scene as the little daughter three years old was held up in the arms of Mrs. Angus to take a last view of, and imprint a last kiss on the cold brow of her only natural protector. But God – who is ever the Father of the fatherless, – took care of the orphans, and they are now grown up to manhood and womanhood, and twenty years have effaced from most the memory of this sad event.

To be continued in Number VIII…

Ishkigamizigedaa! Bad River Sugar Camps 1844

March 15, 2014

Indian Sugar Camp by Seth Eastman c.1850 (Minnesota Historical Society)

Since we’re into the middle of March 2014 and a couple of warm days have had people asking, “Is it too early to tap?” I thought it might be a good time to transcribe a document I’ve been hanging onto for a while.

170 years ago, that question would have been on everyone’s mind. The maple sugar season was perhaps the most joyous time of the year. The starving times of February and early March were on the way out, and food would be readily available again. Friends and relatives, separated during the winter hunts, might join back together in sugar camp, play music around the fire as the sap boiled, and catch up on the winter’s news.

Probably the only person around here who probably didn’t like the sugar season was the Rev. Sherman Hall. Hall, who ran the La Pointe mission and school, aimed to convert Madeline Island’s Native and non-Native inhabitants to Protestantism. To him, Christianity and “civilization” went hand and hand with hard labor and settling down in one place to farm the land. When, at this time of the year, all his students abandoned the Island with everyone else, for sugar camps at Bad River and elsewhere on the mainland and other islands, he saw it as an impediment to their progress as civilized Christians.

Rev. Leonard Wheeler, who joined Hall in 1841, shared many of his ethnocentric attitudes toward Ojibwe culture. However, over the next two decades Wheeler would show himself much more willing than Hall and other A.B.C.F.M. missionaries to meet Ojibwe people on their own cultural turf. It was Wheeler who ultimately relocated from La Pointe to Bad River, where most of the La Pointe Band now stayed, partly to avoid the missionaries, where he ultimately befriended some of the staunchest traditionalists among the Ojibwe leadership. And while he never came close to accepting the validity of Ojibwe religion and culture, he would go on to become a critical ally of the La Pointe Band during the Sandy Lake Tragedy and other attempted land grabs and broken Government promises of the 1850s and ’60s.

In 1844, however, Wheeler was still living on the island and still relatively new to the area. Coming from New England, he knew the process and language of making sugar–it’s remarkable how little the sugar-bush vocabulary has changed in the last 170 years–but he would see some unfamiliar practices as he followed the people of La Pointe to camp in Bad River. Although there is some condescending language in his written account, not all of his comparisons are unfavorable to his Ojibwe neighbors.

Of course, I may have a blind spot for Wheeler. Regular readers might not be surprised that I can identify with his scattered thoughts, run-on sentences, and irregular punctuation. Maybe for that reason, I thought this was a document that deserved to see the light of day. Enjoy:

Bad River Monday March 25, 1844

We are now comfortably quartered at the sugar camps, Myself, wife, son and Indian Boy. Here we have been just three weeks today.

I came myself the middle of the week previous and commenced building a log cabin to live in with the aid of two men , we succeeded in putting up a few logs and the week following our house was completed built of logs 12 by 18 feet long and 4 feet high in the walls, covered with cedar birch bark of most miserable quality so cracked as to let in the wind and rain in all parts of the roof. We lived in a lodge the first week till Saturday when we moved into our new house. Here we have, with the exception of a few very cold days, been quite comfortable. We brought some boards with us to make a floor–a part of this is covered with a piece of carpeting–we have a small cooking stove with which we have succeeded in warming our room very well. Our house we partitioned off putting the best of the bark over the best part we live in, the other part we use as a sort of storeroom and woodhouse.

We have had meetings during on the Sabbath and those who have been accustomed to meet with us have generally been present. We have had a public meeting in the foreroom at Roberts sugar bush lodge immediately after which my wife has had a meeting with the women or a sabbath school at our house. Thus far our people have seemed to keep up their interest in Religion.

They have thus far generally remembered the Sabbath and in this respect set a good example to their neighbors, who both (pagan) Indians and Catholics generally work upon the Sabbath as upon other days. If our being here can be the means of preventing these from declension in respect to religion and from falling into temptation, (especially) in respect to the Sabbath, an important end will be gained.

The sugar making season is a great temptation to them to break the sabbath. It is quite a test upon their faith to see their sap buckets running over with sap and they yet be restrained from gathering it out of respect to the sabbath, especially should their neighbors work in the same day. Yet they generally abstain from Labor on the Sabbath. In so doing however they are not often obliged to make much sacrifice. By gathering all the sap Saturday night, their sap buckets do not ordinarily make them fill in one day, and when the sap is gathered monday morning.

They do not in this respect suffer much loss. In other respects, they are called to make no more sacrifice by observing the sabbath than the people of N.E. do during the season of haying. We are now living more strictly in the Indian country among an Indian community than ever before. We are almost the only persons among a population of some 5 or 600 people who speak the English language. We have therefore a better opportunity to observe Indian manners and customs than heretofore, as well as to make proficiency in speaking the language.

Process of making sugar and skillful use of birch bark.

The process of making sugar from the (maple) sap is in general as that practiced elsewhere where this kind of sugar is make, and yet in some respects the modus operandi is very different. The sugar making season is the most an important event to the Indians every year. Every year about the middle of March the Indians, French and halfbreeds all leave the Islands for the sugar camps. As they move off in bodies from the La Pointe, sometimes in companies of 8, 10, 12 or 20 families, they make a very singular appearance.

Upon some pleasant morning about sunrise you will see these, by families, first perhaps a Frenchman with his horse team carrying his apuckuais for his lodge–provisions kettles, etc., and perhaps in addition some one or two of the [squaw?] helpers of his family. The next will be a dog train with two or three dogs with a similar load driven by some Indians. The next would be a similar train drawn by a man with a squaw pushing behind carrying a little child on her back and two or three little children trudging behind on foot. The next load in order might be a squaw drawn by dogs or a man upon a sled at each end. This forms about the variety that will be witnessed in the modes of conveyance. To see such a ([raucous?] company) [motley process?] moving off, and then listen to the Frenchmen whipping his horse, which from his hard fare is but poorly able to carry himself, and to hear the yelping of the dogs, the (crying of) the children, and the jabbering in french and Indian. And if you never saw the like before you have before you the loud and singular spectacle of the Indians going to the sugar bush.

“Frame of Lodge Used For Storage and Boiling Sap;” undated (Densmore Collection: Smithsonian)

One night they are obliged to camp out before they reach the place of making sugar. This however is counted no hardship the Indian carries his house with him. When they have made one days march it might when they come to a place where they wish to camp, all hands set to work to make to make a lodge. Some shovel away the snow another cut a few poles. Another cuts up some wood to make a fire. Another gets some pine, cedar or hemlock (boughs) to spread upon the ground for floor and carpet. By the time the snow is shoveled away the poles are ready, which the women set around in a circular form at the bottom–crossed at the top. These are covered with a few apuckuais, and while one or two are covering the putting up the house another is making a fire, & perhaps is spreading down the boughs. The blankets, provisions, etc. are then brought in the course of 20 or ½ an hour from the time they stop, the whole company are seated in their lodge around a comfortable fire, and if they are French men you will see them with their pipes in their mouths. After supper, when they have anything to eat, each one wraps himself in a blanket and is soon snoring asleep. The next day they are again under way and when they arrive at the sugar camp they live in their a lodge again till they have some time to build a more substantial (building) lodge for making sugar. A sugar camp is a large high lodge or a sort of a frame of poles covered with flagg and Birch apuckuais open at the top. In the center is a long fire with two rows of kettles suspended on wooden forks for boiling sap. As Robert (our hired man) sugar makes (the best kind of) sugar and does business upon rather a large scale in quite a systematic manner. I will describe his camp as a mode of procedure, as an illustration of the manner in which the best kind of sugar is made. His camp is some 25 or 30 feet square, made of a sort of frame of poles with a high roof open at the (top) the whole length coming down with in about (4 feet) of the ground. This frame is covered around the sides at the bottom with Flag apukuais. The outside and roof is covered with birch (bark) apukuais. Upon each side next to the wall are laid some raised poles, the whole length of the (lodge) wall. Upon these poles are laid some pine & cedar boughs. Upon these two platforms are places all the household furniture, bedding, etc. Here also they sleep at night. In the middle of the lodge is a long fire where he has two rows of kettles 16 in number for boiling sap. He has also a large trough, one end of it coming into the lodge holding several Barrels, as a sort of reservoir for sap, beside several barrels reserved for the same purpose. The sap when it is gathered is put into this trough and barrels, which are kept covered up to prevent the exposure of the sap to the wind and light and heat, as the sap when exposed sours very quick. For the same reason also when the sap and well the kettles are kept boiling night and day, as the sap kept in the best way will undergo some changes if it be not immediately boild. The sap after it is boild down to about the consistency of molases it is strained into a barrel through a wollen blanket. After standing 3 or 4 days to give it an opportunity to settle, some day, when the sap does not run very well, is then set aside for sugaring off. When two or 3 kettles are hung over the fire a small fire built directly under the bottom. A few quarts of molasses are then put into the kettles. When this is boiled enough to make sugar one kettle is taken off by Robert, by the side of which he sets down and begins to stir it with a small paddle stick. After stirring it a few moments it begins to grow all white, swells up with a peculiar tenacious kind of foam. Then it begins to grain and soon becomes hard like [?] Indian pudding. Then by a peculiar moulding for some time with a wooden large wooden spoon it becomes white as the nicest brown sugar and very clean, in this state, while it is yet warm, it is packed down into large birch bark mukoks made of holding from 50 to a hundred lbs.

Makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Ojibwe People’s Dictionary) Photo: Densmore Collection; Smithsonian

Makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Ojibwe People’s Dictionary) Photo: Densmore Collection; SmithsonianCertainly no sugar can be more cleaner than that made here, though it is not all the sugar that is made as nice. The Indians do not stop for all this long process of making sugar. Some of (their) sorup does not pass through anything in the shape of a strainer–much less is it left to stand and settle after straining, but is boiled down immediately into sugar, sticks, soot, dirt and all. Sometimes they strain their sorup through the meshes of their snow shoe, which is but little better than it would be to strain it through a ladder. Their sugar of course has rather a darker hue. The season for making sugar is the most industrious season in the whole year. If the season be favorable, every man wom and child is set to work. And the departments of labor are so various that every able bodied person can find something to do.

The British missionary John Williams describes the coconut on page 493 of his A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands (1837). (Wikimedia Commons)

The British missionary John Williams describes the coconut on page 493 of his A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands (1837). (Wikimedia Commons)In the business of making sugar also we have a striking illustration of the skillful and varied use the Indians make of birch bark. A few years since I was forcibly struck, in reading Williams missionary enterprises of the South Seas, with some annals of his in regard to the use of the cocoanut tree illustrated of the goodness and wisdom of God in so wonderfully providing for their condition and wants (of men). His remarks as near as I can recollect are in substance as follows. The cocoanut tree furnishes the native with timber to make his house, canoe, his fire and in short for most of the purposes for which they want wood. The fruit furnishes his most substantial article of food, and what is still more remarkable as illustrating that principle of compensation by which the Lord in his good providence suplies the want of one blessing by the bestowment of another to take its place. On the low islands their are no springs of water to supply the place of this. The native has but to climb the cocoanut tree growing near his door and pluckes the fruit where in each shall he find from ¼ a pint to a kind of a most agreeable drink to slake his thirst. His tree bearing fruit every month in year, fresh springs of water are supplied the growing upon the trees before his own door. Although the birch bark does not supply the same wants throughout to the Indian, yet they supply wants as numerous and in some respects nearly as important to their mode of living as does the cocoanut to the Inhabitants of the South Sea Islands.

Biskitenaagan: a sap bucket of folded birch bark (Ojibwe People’s Dictionary) Photo: Waugh Collection; Smithsonian

Biskitenaagan: a sap bucket of folded birch bark (Ojibwe People’s Dictionary) Photo: Waugh Collection; SmithsonianIt is with the bark he covers his house. With this bark he makes his canoe. What could the Indian do without his wigwam and his canoe? The first use (of the bark) we notice in the sugar making business what is called the piscatanagun, or vessel for catching sap in. The Indian is not to the expence or trouble of making troughs or procuring buckets to catch the sap at the trees. A piece of birch bark some 14 inches wide and 18 or 20 inches wide in the shape of a pane of glass by a peculiar fold at each end kept in place by a stitch of bark string makes a vessel for catching sap called a piskitenagun. These are light, cheap, easily made and with careful usage will last several years. When I first saw these vessels, it struck me as being the most skillful use of the bark I had seen. It contrasted so beautifully with the clumsy trough or the more expensive bucket I had seen used in N.E. This bark is not only used to catch the sap in but also to carry it in to the sugar camps, a substitute for pails, though lighter and much more convenient for this purpose than a pail.

In making a sap bucket bark of a more substantial kind is used than for the piskatanaguns. They made large at the bottom small at the top, to prevent the sap from spilling out by the motion of carrying. They are sewed up with bark the seams gummed and a hoop about the top to keep them in shape and a lid. But we are not yet done with the bark at the sugar bush. In boiling sap in the evening thin strips are rolled tight together, which is a good substitute for a candle. Every once in a little while the matron of the lodge may be seen with her little torch in hand walking around the fire taking a survey of her kettles. Lastly when the sugar is made it is finally deposited in large firmly wrought mukuks, which are made of bark. This however is not the end of bark. It is used for a variety of other purposes. Besides being a substitute in many cases for plates, [bearers & etc.?], it is upon birch bark that the most important events in history are recorded–National records–songs, & etc. are written in hieroglific characters (upon this article) and carefully preserved by many of the Indians.

And finally the most surprising use of bark of which I have heard or could conceive of, is before the acquaintance of the Indians with the whites, the bark was used as a substitute for kettles in cooking, not exactly for bake kettles but for (kettles for) boiling fish, potatoes, & etc. This fact we have from undoubted authority. Some of the Indians now living have used it for this purpose themselves, and many of them say their fathers tell them it was used by their ancestors before iron kettles were obtained from the whites. One kettle of bark however would not answer but for a single use.

Transcription note: Spelling and grammatical errors have been maintained except where ambiguous in the original text. Original struck out text has been maintained, when legible, and inserted text is shown in parentheses. Brackets indicate illegible or ambiguous text and are not part of the original nor are the bolded words and phrases, which were added to draw attention to the sidebars.

The original document is held by the Wisconsin Historical Society in the Wheeler Family Papers at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center in Ashland.

“Chippewa Bucket and Trays Made of Birch Bark” (

“Chippewa Bucket and Trays Made of Birch Bark” (