Translation Help Needed: Ojibwe and French placenames on Joseph Nicollet’s manuscript map of Wisconsin

December 31, 2018

Joseph Nicholas Nicollet 1786-1843 (Wikipedia) *Not to be confused with Jean Nicolet, the explorer who visited Green Bay 200 years before this.

By Leo

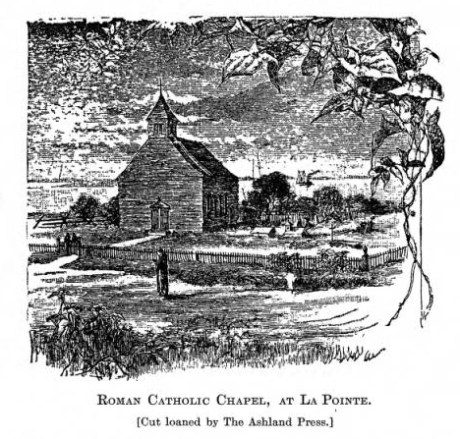

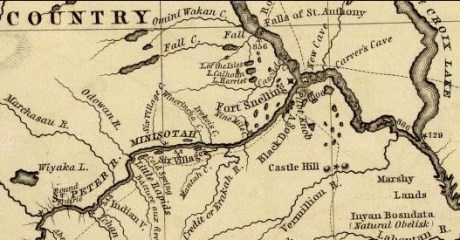

Joseph Nicollet* is a name familiar to many in the Upper Midwest. The French-born geographer is remembered in numerous place names, particularly in Minnesota. For followers of Chequamegon History, though, he is best known for his 1843 Map of the Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi. The map remains very popular for its largely-accurate geography and its retention of original Ojibwe and French placenames for rivers, lakes and other land features. I’ve always found it an attractive map, and use the Chequamegon portion of it to decorate the side panels of the blog.

So, one can imagine the excitement when Brian Finstad emailed and told me there was another version of the map, and that it was available online from St. Olaf College. This version, covering the country between the St. Croix and Wisconsin rivers (what is now the northwestern half of Wisconsin) is handwritten and contains information and names that never made it onto the published map. For those unfamiliar with Brian Finstad’s work, he is a long-time correspondent of Chequamegon History and has a keen and detailed understanding of the Gordon/Upper St. Croix region and the history of the St. Croix-La Pointe trail.

Click to Enlarge or visit the zoomable version at the Nicollet Project at St. Olaf College

The manuscript is also differs from the published map in that the placement of lakes, rivers, and portages. At first glance, to those of us used to Google and the modern highway system, to be less accurate in terms of actual fixed latitude and longitude. Instead, it seems more reflective of how Wisconsin’s geography would have been perceived at the time–as chains of water routes and portages. I need to look into it further, but my current understanding is that Nicollet did not travel extensively in Wisconsin. Therefore, one can assume that he got most of this information from his hired Ojibwe and Metis guides and voyageurs.

Zhagobe (Shakopee, Chagobai, Little Six), a Snake River chief worked with Nicollet and may have been an informant for the map. (Painting by Charles Bird King from James Otto Lewis portrait 1825 or 1826)

The handwritten map is challenging to read. Parts of it are ripped and faded, and the labels are oriented in all directions, including upside-down. Perhaps most difficult for me, as a monolingual English speaker, the map is in no fewer than four languages. French predominates, but there is a great deal of Ojibwe (especially in place names) and some English in descriptions. Near the mouth of the Chippewa River, there is another language, probably Dakota, but I don’t know Siouan languages well enough to say it is not Ho-Chunk.

After spending a few minutes with the map, I knew that the only way I would be able to engage with it fully would be to make it a project. So, I set out to reproduce the map, as faithfully as possible to the original, but with more legible text oriented according to more-modern cartographic conventions. Here is the result:

My hope is that the reproduction will make comparisons with the published map easier for scholars, or at the very least, provide a guide for working with the manuscript. However, this is where I’ll need help from readers, especially those who are good with Ojibwe and French grammar.

Here are some of the challenges we’re up against:

Familiarity of Locations

Being most familiar with the parts of Wisconsin within the Lake Superior basin, a map that focuses on the Mississippi watershed is not necessarily in my wheelhouse. Unfortunately, that’s what this truly is a map. Locations on the lakeshore are barely shown on the manuscript. There is far better detail in Nicollet’s published map showing that he must have used different sources to fill in that section of his finished product. However, because the Chequamegon area is the most ripped, faded, and difficult part to read on the entire map, familiarity was an asset. In the snippet on the left, I am fairly confident that the ripped part under “Chagwamigon” should read Long Ile ou Lapoint or something very similar. Whereas, the snippet on the right, showing the Eau Galle River area west of Eau Claire, has much clearer script, but I am far less confident in my transcription because I have not been able to locate any online references to Jolie Butte or Rhewash. Waga online. So, if there are any French or Dakota speakers out there who live near the mouth of the Chippewa let me know if there is a place called “Pretty Mound” or something similar and if I got my letters correct.

Colloquial Nouns in Poor Handwriting

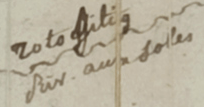

Readers of the blog know that I am a big fan of Google Translate. Compared with the early days of online translation, it is amazing how close one can to reading text in an unfamiliar language these days. No online translation is ever perfect, especially with grammar, but Google usually steers me in the right direction for nouns. That said, there are some problems. The French language, as translated by Google, is more or less the 20th-century version of what Nicollet was educated in. However, neither of those is the French that was spoken in this area. What European visitors called Patois and what Manitobans call Michif or Metis French is truly a language of its own and a product of the fur trade. The “French” of 19th-century La Pointe contained a great deal of Ojibwe and numerous archaic words from colonial Quebec. This can create challenges in translation, especially when the handwriting is ambiguous. The snippet on the left, for example, appears to be the Poplar River in Douglas County. However, the label doesn’t appear to say anything like peuplier or tremble (aspen). I played around with “frondes” or considered other river names entirely, until I stumbled across the word liard. Liard does not seem to have the meaning in modern French, but in colloquial Quebecois, it is regionally used to describe several different species of popple tree. Riv. aux Soles (right), however, has proved much more difficult. I initially saw the French name of the Totagatic as Riv. aux Lobes, but after some emails with Brian Finstad, Soles seems like the best guess. But, what is a Sole? Is it the sun? The bottom of a foot? A flounder? The same fish name can often be applied to different species in different regions. Is a sculpin a sole? Is a bullhead? Do we need to talk to old fishermen in Quebec to find out?

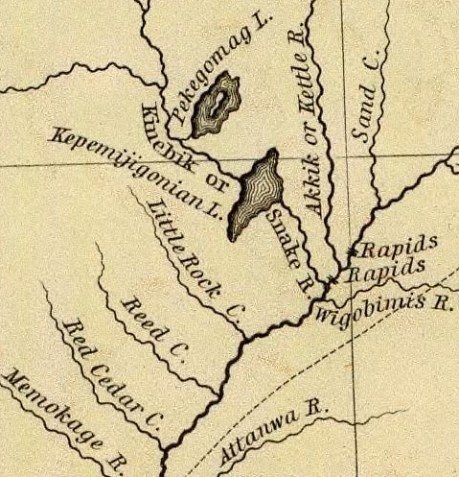

Lack of Grammatical Knowledge

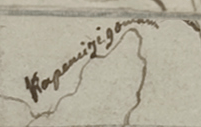

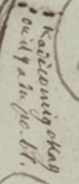

If Google Translate is my go-to place for French, the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary is where I go to try to confirm words in Ojibwe. Again, it’s great for nouns and verb-parts, but unless you speak these languages better than I do, knowing the gist of what the word means doesn’t mean you’ll get the translation right. In the snippet on the left, I transcribed the Ojibwe name for Cross Lake on the Snake River as Kapemijigonian. This word has elements of the meaning “flows through” in Ojibwe, but the word is nonsensical grammatically. Charles Lippert, who works for the Mille Lacs Band and has a wealth of information about Ojibwe linguistics, knew the real name, and was kind enough to offer Kapemijigoman as the correct transcription. Who knows how many similar errors could have been made? French can be tricky too. Mistaking ou for on, which is very possible with Nicollet’s handwriting, might not alter the meaning of a large chunk of text on Google Translate, but it sure can make you sound like a two-year old. Check out the snippet of French on the right. How can a non-Francophone read that?

I used the Inkscape vector graphics illustration program to trace the reproduction from the original.

As always, thanks for reading and please send feedback.

By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from Copper Harbor Redux.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 29, 1845.

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE.

—

[From our regular correspondent.]

ST. LOUIS, Mo. Aug. 19, 1845.

One of the most interesting sections of the North American continent is the basin of the Upper Mississippi, being, as it is, greatly diversified by soil, climate, natural productions, &c. It embraces mineral lands of great extent and value, with immense tracts of good timber, and large and fertile bodies of farming land. This basin is separated by elevated land o the northeast, which divides the headwaters of rivers emptying into the Mississippi from those that flow into the lakes Superior and Michigan, Green Bay, &c. To the north and northwest, it is separated near the head of the Mississippi, by high ground, from the watercourses which flow towards Hudson’s bay. To the west, this extensive basin is divided from the waters of the Missouri by immense tracts of elevated plateau, or prairie land, called by the early French voyageurs “Coteau des Prairies,” signifying “prairie coast,” from the resemblance the high prairies, seen at a great distance, bear to the coast of some vast sea or lake. To the south, the basin of the Upper Mississippi terminates at the junction of the Mississippi with the Des Moines river.

The portion of the valley of the Mississippi thus described, if reduced to a square form, would measure about 1,000 miles each way, with St. Anthony’s falls near the centre.

1698 detail of Saint Anthony’s Falls and Lake Superior from Amerique Septentrionalis Carte d’un tres grand Pays entre le Nouveau Mexique et la Mer Glaciace Dediee a Guilliaume IIIe. Roy de La Grand Bretagne Par le R. P. Louis de Hennepin Mission: Recol: et Not: Apost: Chez c. Specht a Utreght 1698.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

For a long time, this portion of the country remained unexplored, except by scattered parties of Canadian fur-traders, &c. Its physical and topographical geography, with some notions of its geology, have, as it were, but recently attracted attention.

Douglas Volk painting of Father Hennepin at Saint Anthony Falls.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

Father Antoine “Louis” Hennepin

~ Wikipedia.org

Father Hennepin was no doubt the first white man who visited St. Anthony’s falls. In reaching them, however, he passed the mouth of St. Peter’s river, a short distance below, without noticing it, or being aware of its existence. This was caused by the situation of an island found in the Mississippi, directly in front of the mouth of St. Peter’s, which, in a measure, conceals it from view.

After passing the falls, Father Hennepin continued to ascend the Mississippi to the St. Francis river, but went no higher.

Portrait of Jonathan Carver from his book, Travels through the interior parts of North America in the years 1766, 1767 and 1768.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

In the year 1766, three years after the fall of Canada, Captain Johnathan Carver, who had taken an active part as an officer in the English service, and was at the surrender of Fort William Henry, where (he says) 1,500 English troops were massacred by the Indians, (he himself narrowly escaping with his life,) prepared for a tour among the Indian tribes inhabiting the shores of the upper lakes and the upper valley of the Mississippi. He left Boston in June of the year stated, and, proceeding by way of Albany and Niagara, reached Mackinac, where he fitted out for the prosecution of his journey to the banks of the Mississippi.

From Mackinac, he went to Green Bay; ascended the Fox river to the country of the Winnebago Indians; from thence, crossing some portages, and passing through Lake Winnebago, he descended the Wisconsin river to the Mississippi river; crossing which, he came to a halt at Prairie du Chien, in the country of the Sioux Indians. At the early day, this was an important trading-post between French traders and the Indians. Carver says: “It contains about three hundred families; the houses are well built, after the Indian manner, and well situated, on a very rich soil, from which they raise every necessary of life in great abundance. This town is the great mart whence all the adjacent tribes – even those who inhabit the most remote branches of the Mississippi – annually assemble about the latter end of May, bringing with them their furs to dispose of to the traders.” Carver also noticed that the people living there had some good horses.

Detail of Prairie du Chien from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766.

~ Boston Public Library

The fur-trade, which at one time centred here, and gave it much consequence, has been removed to St. Peter’s river. Indeed, this trade, which formerly gave employment to so many agents, traders, trappers, &c., conferring wealth upon those prosecuting it, is rapidly declining on this continent; in producing which, several causes conspire. The first is, the animals caught for their furs have greatly diminished; and the second is, that competition in the trade has become more extensive and formidable, increasing as the white settlements continue to be pushed out to the West.

John Jacob Astor established the American Fur Company.

~ Wikipedia.com

At Prairie du Chien is still seen the large stone warehouse erected by John Jacob Astor, at a time when he ruled the trade, and realized immense profits by the business. The United States have a snug garrison at this place, which imparts more or less animation to the scene. It stands on an extensive and rather low plain, with high hills in the rear, running parallel with the Mississippi.

The house in which Carver lodged, when he visited this place, is still pointed out. There are some men living at this post, whose grandfather acted as interpreter to Carver. The Sioux Indians, whom Carver calls in his journal “the Nadowessies,” which is the Chippewa appellation for this tribe of Indians, keep up the tradition of Carver’s visit among them. The inhabitants, descendants of the first settlers at Prairie du Chien, now living at this place, firmly believe in the truth of the gift of land made to Carver by the Sioux Indians.

From this point Carver visited St. Anthony’s falls, which he describes with great accuracy and fidelity, accompanying his description with a sketch of them.

![Detail of Saint Anthony's Falls from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766. ~ Boston Public Library](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/carver-detail-of-st-anthony-falls.jpg?w=460)

Detail of Saint Anthony’s Falls from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766.

~ Boston Public Library

From the Mississippi river Carver crossed over to the Chippewa river; up which he ascended to its source, and then crossed a portage to the head of the Bois Brulé, which he called “Goddard’s river.” Descending this latter stream to Lake Superior, he travelled around the entire northern shore of that lake from west to east, and accurately described the general appearance of the country, including notices of the existence of the copper rock on the Ontonagon, with copper-mineral ores at points along the northeastern shore of the lake, &c.

![Detail of "Goddard's River," La Pointe, and Ontonagon from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766. ~ Boston Public Library](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/carver-detail-of-goddard-river-and-la-pointe.jpg?w=460)

Detail of “Goddard River,” La Pointe, and Ontonagon from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766.

~ Boston Public Library

He finally reached the Sault St. Marie, where he found a French Indian trader, (Monsieur Cadot,) who had built a stockade fort to protect him in his trade with the Indians.

![Detail of Sault Ste Marie from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766. ~ Boston Public Library](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/carver-detail-of-sault-ste-marie.jpg?w=460)

Detail of Sault Ste Marie from Carver [Jonathan], Captain. Journal of his travels with maps and drawings, 1766.

~ Boston Public Library

Descendants of this Monsieur Cadot are still living at the Sault and at La Pointe. We met one of them returning to the latter place, in the St. Croix river, as we were descending it. They, no doubt, inherit strong claims to land at the falls of the St. Mary’s river, which must ere long prove valuable to them, if properly prosecuted.

From the Sault St. Marie, Carver went to Mackinac, then garrisoned by the English, where he spent the winter. The following year he reached Boston, having been absent about two years.

From Boston he sailed for England, with a view of publishing his travels, and securing his titles to the present of land the Sioux Indians have made him, and which it is alleged the English government pledged itself to confirm, through the command of the King, in whose presence the conveyance made to Carver by the Sioux Indians was read. He not only signified his approval of the grant, but promised to fit out an expedition with vessels to sail to New Orleans, with the necessary men, &c., which Captain Carver was to head, and proceed from thence to the site of this grant, to take possession of it, by settling his people on it. The breaking out of the American revolution suspended this contemplated expedition.

Captain Carver died poor, in London, in the year 1780, leaving two sons and five daughters. I consider his description of the Indians among whom he travelled, detailing their customs, manners, and religion, the best that has ever been published.

In this opinion I am sustained by others, and especially by old Mr. Duncan Graham, whom I met on the Upper Mississippi. He has lived among the Indians ever since the year 1783. He is now between 70 and 80 years old. He told me Carver’s book contained the best account of the customs and manners of the Indians he had ever read.

His valuable work is nearly out of print, it being rather difficult to obtain a copy. It went through three editions in London. Carver dedicated it to Sir Joseph Banks, president of the Royal Society. Almost every winter on the Indians and Indian character, since Carver’s time, has made extensive plagiarisms from his book, without the least sort of acknowledgement. I could name a number of authors who have availed themselves of Carver’s writings, without acknowledgement; but as they are still living, I do not wish to wound the feelings of themselves or friends.

One of the writers alluded to, gravely puts forth, as a speculation of his own, the suggestion that the Winnebagoes, and some other tribes of Indians now residing at the north, had, in former times, resided far to the south, and fled north from the wars and persecutions of the bloodthirsty Spaniards; that the opinion was strengthened from the fact, that the Winnebagoes retained traditions of their northern flight, and of the subsequent excursions of their war parties across the plains towards New Mexico, where, meeting with Spaniards, they had in one instance surprised and defeated a large force of them, who were travelling on horseback.

Now this whole idea originated with Carver; yet Mr. ——— has, without hesitation, adopted it as a thought or discovery as his own!

Alexander Henry, The Elder.

~ Wikipedia.com

The next Englishman who visited the northwest, and explored the shores of Lake Superior, was Mr. Henry, who departed from Montreal, and reached Mackinac through Lake Huron, in a batteau laden with some goods. His travels commenced, I believe, about 1773-‘4, and ended about 1776-‘7. Mr. Henry’s explorations were conducted almost entirely with the view of opening a profitable trade with the Indians. He happened in the country while the Indians retained a strong predilection in favor of the French, and strong prejudices against the English. It being about the period of the Pontiac war, he had some hazardous adventures among the Indians, and came near losing his life. He continued, however, to prosecute his trade with the Indians, to the north and west of Lake Superior. Making voyages along the shores of this lake, he became favorably impressed with the mineral appearances of the country. Finding frequently, through is voyageurs, or by personal inspections, rich specimens of copper ore, or of the metal in its native state, he ultimately succeeded in obtaining a charter from the English government, in conjunction with some men of wealth and respectability in London, for working the mines on Lake Superior. The company, after making an ineffectual attempt to reach a copper vein, through clay, near the Ontonagon, the work was abandoned, and was not afterwards revived.

General Cass, with Colonel Allen, &c., were the next persons to pass up the southern coast of Lake Superior, and, in going to the west and northwest of the lake, they travelled through Indian tribes in search of the head of the Mississippi river. Their travels and discoveries are well known to the public, and proved highly interesting.

Mr. Schoolcraft’s travels, pretty much over the same ground, have also been given to the public; as also the expedition of General Pike on the Upper Mississippi.

Major Stephen Harriman Long published his expedition as Voyage in a Six-oared Skiff to the Falls of St. Anthony in 1817.

~ Wikipedia.org

More lately, the basin of the Upper Mississippi has received a further and more minute examination under the explorations directed by Major Long, in his two expeditions authorized by government.

Joseph Nicholas Nicollet

~ Wikipedia.org

Lastly, Mr. J. N. Nicollet, a French savan, travelling for some years through the United States with scientific objects in view, made an extensive examination of the basin of the Upper Mississippi.

He ascended the Missouri river to the Council Bluffs; where, arranging his necessary outfit of men, horses, provisions, &c., (being supplied with good instruments for making necessary observations,) he stretched across a vast tract of country to the extreme head-waters of the St. Peter’s, determining, as he went, the heights of places above the ocean, the latitude and longitude of certain points, with magnetic variations. He reached the highland dividing the waters of the St. Peter’s from those of the Red river of the North. He descended the St. Peter’s to its mouth; examined the position and geology of St. Anthony’s falls, and then ascended the same river as high as the Crow-wing river. The secondary rock observed below the falls, changes for greenstone, sienite, &c., with erratic boulders. On the east side of the river, a little below Pikwabik, is a large mass of sienitic rock with flesh-colored feldspar, extending a mile in length, half a mile in width, and 80 feet high. This is called the Little Rock. Higher up, on the same side, at the foot on the Knife rapids, there are sources that transport a very fine, brilliant, and bluish sand, accompanied by a soft and unctuous matter. This appears to be the result of the decomposition of a steachist, probably interposed between the sienitic rocks mentioned. The same thing is observed at the mouths of the Wabezi and Omoshkos rivers.

Detail of Saint Anthony’s Falls and Saint Peter’s River from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

Ascending the Crow-wing river a short distance, Mr. Nicollet turned up Gull river, and proceeded as far as Pine river, taking White Fish lake in his way; and again ascended the east fork of Pine river, and reached Little Bay river, which he descended over rapids, &c., to Leech lake, where he spent some days in making astronomical observations, &c. From Leech lake, he proceeded, through small streams and lakes, to that in which the Mississippi heads, called Itasca. Having made all necessary observations at this point, he set out on his return down the Mississippi; and finally, reaching Fort Snelling at St. Peter’s, he spent the winter there.

Detail of Leech Lake and Lake Itasca from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

Lake Itasca, in which the Mississippi heads, Mr. Nicollet found to be about 1,500 feet above the level of the ocean, and lying in lat. about 47° 10′ north, and in lon. 95° west of Greenwich.

This vast basin of the Upper Mississippi forms a most interesting and valuable portion of the North American continent. From the number of its running streams and fresh-water lakes, and its high latitude, it cannot fail to prove a healthy residence for its future population.

It also contains the most extensive body of pine timber to be found in the entire valley of the Mississippi, and from which the country extending from near St. Anthony’s falls to St. Louis, for a considerable distance on each side of the river, and up many of its tributaries, must draw supplies of lumber for building purposes.

In addition to these advantages, the upper basin is rich in mines of lead and copper; and it is not improbable that silver may also be found. Its agricultural resources are also very great. Much of the land is most beautifully situated, and fertile in a high degree. The climate is milder than that found on the same parallel of latitude east of the Alleghany mountains. Mr. Nicollet fixes the mean temperature at Itasca lake at 43° to 44°; and at St. Peter’s near St. Anthony’s falls, at 45° to 46°

“Maiden Rock. Mississippi River.“ by Currier & Ives. Maiden’s Rock Bluff. This location is now designated as Maiden Rock Bluff State Natural Area.

~ SpringfieldMuseums.org

Every part of this great basin that is arable will produce good wheat, potatoes, rye, oats, Indian corn to some extent, fine grasses, fruits, garden vegetables, &c. There is no part of the Mississippi river flanked by such bold and picturesque ranges of hills, with flattened, broad summits, as are seen extending from St. Anthony’s falls down to Prairie du Chien, including those highlands bordering Lake Pepin, &c. Among the cliffs of sandstone jutting out into perpendicular bluffs near the river, (being frequently over 100 feet high,) is seen one called Maiden’s rock. it is said an Indian chief wished to force his daughter to marry another chief, while her affections were placed on another Indian; and that, rather than yield to her father’s wishes, she cast herself over this tall precipice, and met an instant death. On hearing of which, her real lover, it is said, also committed suicide. Self-destruction is very rare among the Indians; and we imagine, when it does occur, it must be produced by the strongest kind of influence over their passions. Mental alienation, if not entirely unknown among them, must be exceedingly rare. I have no recollection of ever having heard of a solitary case.

From St. Anthony’s falls to St. Louis is 900 miles. The only impediment to the regular navigation of the river by steamboats, is experienced during low water at the upper and lower rapids.

“St. Louis Map circa 1845”

~ CampbellHouseMuseum.org

The first are about 14 miles long, with a descent of only about 25 feet. The lower rapids are 11 miles long, with a descent of 24 feet. In each case, the water falls over beds of mountain or carboniferrous limestone, which it has worn into irregular and crooked channels. By a moderate expenditure of money on the part of the general government, which ought to be made as early as practicable, these rapids could be permanently opened to the passage of boats. As it is at present, boats, in passing the rapids at low water, and especially the lower rapids, have to employ barges and keel-boats to lighten them over, at very great expense.

From the rapid settlement of the country above, with the increasing trade in lumber and lead, the business on the Upper Mississippi is augmenting at a prodigious rate. When the river is sufficiently high to afford no obstruction on the lower rapids, not less than some 28 or 30 boats run regularly between Galena and St. Louis – the distance being 500 miles. Besides these, two or three steam packets run regularly to St. Anthony’s falls, or to St. Peter’s, near the foot of them. Every year will add greatly to the number of these boats. Other fine large and well-found packets run from St. Louis to Keokuk, at the foot of the lower rapids, four miles below which the Des Moines river enters the Mississippi river. It is the opinion of Mr. Nicollet, that this river can be opened, by some slight improvements, for 100 miles above its mouth. It is said the extensive body of land lying between the Des Moines and the Mississippi, and running for a long distance parallel with the left bank of the latter, contains the most lovely,rich and beautiful land to be found on the continent, if not in the world. It is already pretty thickly settled. Splendid crops of wheat and corn have been raised on farms opened upon it, the present year. Much of the former we found had already arrived at depots on the river, in quantities far too great to find a sufficient number of boats, at the present low water, to carry it to market.

I do not see but the democratic party are regularly gaining strength throughout the great West, as the results of the recent elections, which have already reached you, sufficiently indicate.

Those who wish to obtain more general, as well as minute information, respecting the basin of the Upper Mississippi, I would recommend to consult the able report, accompanied with a fine map of the country, by Mr. J. N. Nicollet, and reprinted by order of the Congress at their last session.

I am, very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

MORGAN.

This curious series of correspondences from “Morgan” is continued in the September 1 and September 5 issues of The Daily Union, where he arrived in New York City again after 4,200 miles and two and a half months on this delegation. As those articles are not pertinent to the greater realm of Chequamegon History, this concludes our reproduction of these curious correspondences.

The End.

Wisconsin Territory Delegation: Saint Croix Falls

April 28, 2016

By Amorin Mello

A curious series of correspondences from “Morgan”

… continued from La Pointe.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

August 27, 1845.

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE.

—

(From our regular correspondent.)

FALLS, ST. CROIX, W. T., Aug. 7, 1845.

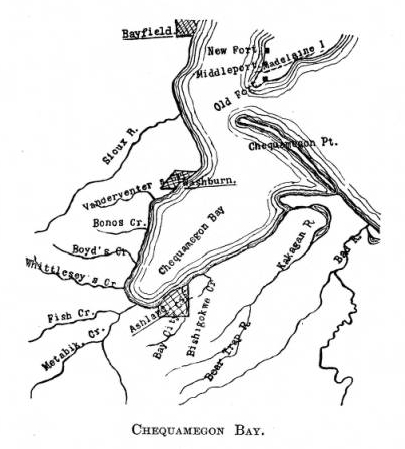

We left La Pointe on the afternoon of the day on which my last letter was dated. We had about 70 miles (English,) or 63 of French voyageur’s miles, to travel westward on the lake, before reaching the Brulé river, which we were to ascend for 75 miles, to make the portage to the St. Croix; the latter river being, from its source to the Mississippi river, including the Lake St. Croix at its mouth, about 300 miles long – thus making a journey before us of about 445 miles to reach the Mississippi. To La Pointe we had already coasted from Sault St. Marie, including the curves, bends, bays, &c , with the entire circuit of Keweena point, the distance of at least 500 miles. The two added together, give 945 miles of travel, in open boats by day, and under tents by night, with the exception of the three miles portage between the two rivers. We left the Sault on the 4th July, and reached this place within 50 miles of the Mississippi, making the whole time consumed one month and about three or four days, by the time we will have reached the “father of waters.”

Detail of the shoreline between La Pointe and the Bois Brulé River from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The distance, in a direct line, from the head of the bay opposite La Pointe, to the portage at the head of the Brulé, by land, is only 80 miles; while by the lake and river, it is about 145. The whole distance, in a direct line, by land, from La Pointe to the falls of St. Anthony, or to the mouth of the St. Peter’s, does not exceed, by the Indian trail alluded to, over 200 miles.

The first day we left La Pointe we were only enabled to reach Raspberry river, a small stream emptying into the lake 15 miles west of La Pointe, inside the group of islands.

We first encountered a prodigious thick fog, with a head wind. We had no sooner landed and raised our tent, than a thunder-storm, with a heavy rain, burst upon us. The voyageurs, as is their custom, had puled the bark canoes out of the water, and turned them over, placing provisions and other articles under them for shelter. The Indians, in travelling with their canoes, invariably pull them out of the water at night, turn them bottom upwards, and in bad weather, sleep under them; as our voyageurs (especially Jocko, our Indian voyageur) did on the night in question. In such cases, they turn water like the roof of a house. We had, late in the afternoon, doubled some frowning sandstone cliffs alluded to in my other letter, with the grottoes, caves, and excavations wrought out near the water’s edge, by the combined action of the waves and frost. Another high sandstone promontory still lay just ahead of us, which Ribedoux, our head man, said extended for six miles without affording a landing-place for a boat.

Next morning we found a severe gale blowing from the north-northeast, accompanied with rain. This compelled us to remain where we were till about 3 or 4 o’clock in the afternoon, when we set out. The wind had died away, but the sea was running very high, over which our canoes danced along at a great rate – riding them, however, like swans. The heaviest rolls would be mounted and slid over with as much ease as though the canoes were feathers, as they were propelled forward by the oars and paddles of our skillful voyageurs.

One canoe being small, only admitted of the use of paddles. The larger craft allowed a pair of oars to be used in front, while a paddle was employed in the stern. The usual plan of working canoes is to have only two persons to attend to one canoe. They are always steered with a paddle. One voyageur seats himself in the bow; while another does the same thing in the stern – the baggage, provisions, passengers, &c., being stored amidships, low in the hull. Thus arranged, the men apply their paddles with great skill, driving the canoe forward at a pretty rapid speed.

The Voyageurs by Charles Deas, 1846.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

The Indians display a deal of skill in the construction of their bark canoes. Their hulls have great symmetry of form; and, under careful handling, which the Indians perfectly understand and practise, they are very light and very strong.

The birch bark, from which they are principally made, is found of excellent quality on the shores and tributaries of Lake Superior, and is extensively used by the Indians for building their lodges, &c., as well as for canoes. In the latter application, the inside of the bark is exposed to the water and weather; while, in the former case, the outside of the bark is turned to the weather. Their lodges are of a hemispherical shape, with an opening at the top for the escape of smoke, with a door opening on one side of them, before which a blanket is usually suspended. The floor of the lodge, with the wealthier class, is usually covered with fine large richly-colored rush mats, on which the Indians recline or sit like Turks on them. The men, when at home, do little else than recline on the mats and smoke, while the squaws and half-grown children perform all the necessary manual labor. If an Indian brings in game or fish, he throws it down near his lodge, and troubles himself no more about it; or, if it be troublesome to carry, he leaves it in the woods, returns to the lodge, and sends his squaw for it.

The females among the Indians invariable exhibit the most modest and retiring deportment – equally as much so, I have thought, as is seen or met with among the most civilized whites. Neither males nor females, when you enter their villages or lodges, ever fix upon you that rude glare, or gaze, which white people often do upon the sudden appearance of a stranger. The usual salutation of the Chippewa, on meeting you, is “Bojour, bojour, bojour,” at the same time extending his hand to you in friendship. And if there are fifty men in company, they will all do the same thing. The exclamations they use is a corruption of the French salutation of “bon jour,” “good day;” or, in English parlance, “how d’ye do.”

The Indians are very fond of bathing and swimming, and they do not consider it the least indelicate for all sexes to bathe at the same time in the immediate vicinity of each other. I am told, on such occasions, the females wear dresses prepared for the purpose. The men also are partly clad.

“There are indications that Granville served as a teacher in a school unrelated to ABCFM on or near the Mackinaw Island from the fall of 1834 to the fall of 1835. His first connection with ABCFM dates from September 1835, and he was officially appointed by ABCFM as a missionary assistant some time in 1836. Granville took a leave between July 1837 and June 1838, then returned to La Pointe with his newly wed wife, Florantha nee Thompson. After one unsuccessful pregnancy, Florantha had two healthy daughters, in October 1842, and March 1844. Granville and Florantha retired from the mission in the summer of 1846.”

~ The Sproats at La Pointe: From pages of the Missionary Herald, Boston

I was told by Mr. Grote, who has resided at the Presbyterian mission at La Pointe for some 10 or 12 years, that the Indians, during long peace, and when little surrounds them of a nature to arouse or excite their energies, become, in general, very lethargic, and sink apparently (from ennui) into premature old age, few of them attaining to the years of advanced life. Among the chiefs I saw at La Pointe, was an old man of sixty. His hair was quite gray. He was introduced to me by a friend, at his own request. He wanted to know where I was from, and whether I had been sent to carry off the Indians. He was told that I had come on no such errand, but merely to visit and see the country, and that I was a “medicine man,” a “mushkiwinini:” this announcement put me on a very friendly footing with him. He bore a strong resemblance to Robert Dale Owen, the lecturer.

I was told by Mr. Grote that this old chief retained very strong predilections in favor of the British; that he frequently spoke of the good old times when they received fine presents and cheap goods from their great father, the King over the water; and that he annually paid a visit to the Hudson Bay Company’s trading-post at Fort William, or at the Sault, and received presents to some small amount. he nevertheless professed much friendship for the Americans.

“Mainland sea caves from the water.”

~ Apostle Islands National Lakeshore

We left Raspberry river between 3 and 4 p.m., and passed one among the most picturesque cliffs of sand-stone it was our lot to see during the voyage. It spread along the shore for 6 or 7 miles, varying in height from 50 to 100 feet. Its base was carved into holes and grottoes of every variety of form, into which the heavy rolls of the waves were pitching with a rumbling and heavy sound; while the white spray flew in foaming whiteness about the outward rocks. Making a beach near dark at the bottom of the bay, beyond the cliffs, we landed and camped. Early next morning we were again under way. In the afternoon we passed four Indian canoes loaded with Indians bound for La Pointe. They were from Fond-du-Lac.

Making Cranberry river, we found Capt. Stanard and his party of voyageurs, who had preceded us from La Pointe, and were bound for Fond-du-Lac, had stopped for dinner. We concluded to land at the same place for the same purpose.

We were told by Capt. S that he had, on his way, visited an encampment of Indians from Fond-du-Lac, who stated that the Chippewas at that place were laboring under a good deal of excitement. It seemed that two Indians of that place had been on a visit to the falls of St. Croix, where liquor was freely sold to the Indians; that one of the Indians and a white man quarrelled about a dog; that the latter mauled and beat the former most unmercifully, when the other Indian attempted to interfere, whom the white man attacked and commenced beating also. The last Indian thereupon stabbed the white man in the breast with a knife, the point of which struck a bone and glanced. The white man then drew a pistol, and fired it at the Indian, wounded him severely in the thigh. The Indians then left the falls, and returned to Fond-du-Lac highly incensed, and swearing vengeance against the whites; saying their relations numbered thirty warriors, who would aid them, if necessary, in seeing justice done. They also said that, some time ago, a Sioux Indian had killed a Chippewa, and that the whites did nothing with him for it. When the brother of the deceased Chippewa went over to St. Peter’s, and killed the Sioux, the whites had taken up two Chippewas, and had them in jail, which they thought very hard of. It was also said that sometimes, when the Chippewas left their homes to go to the payment, the Sioux followed them, with a view of annoying and harassing them in the rear.

Captain S. said that he had intended to visit the falls of the Brulé, to fish for trout; but that, owing to these reported difficulties, he should proceed directly to Fond-du-Lac. It seems that the whole foundation of the troubles on the St. Croix, with the Chippewas, has grown out of the circumstance of grog-shops having been opened at different places along that stream – say one at the falls, another at Wolf river, eighteen or twenty miles above, and a third at the Rising Sun, twenty-five miles above the falls – by low and villanous white men, or half-breeds engaged in their service. It seems that, some years since, the Chippewas made a treaty, ceding all their lands to the United States, south of a line running due south some fifty miles from the extreme west end of Lake Superior, and from that southern point due west to the mouth of Crow-wing river, on the Upper Mississippi, cutting nearly through the centre of Mille Lake in its course. There is a proviso in the treaty of cession, which authorizes the Indians to remain in the occupancy of the ceded territory till it is wanted by the government. I understood Mr. Hays (the Indian agent at La Pointe) to say that he had no power to stop the sale of ardent spirits to the Indians, by the white squatters in the ceded country. These drunken outrages, if not put a stop to on the St. Croix, will, ere long, lead to serious and disastrous consequences. The Indians and whites will soon become embroiled in a border “guerrilla” war, and the poor savages, in the end, be butchered and driven out of the country – all, too, growing out of the cupidity of a few rascally men, who aim to cheat and rob the Indians of their last blanket, by selling them the hellish poison of whiskey. What is the massacre of innocent whites, with the ruin and degradation of Indians, to them, provided they can turn a penny by dealing out rum!! Mr. Hays lives almost too remote from the St. Croix to prevent these outrages, even if he had the power. But it does seem to me, that the Indian agent at St. Peter’s, who resides within a day or two’s journey of these outrages, might do something to prevent them.

With due vigilance and firmness on his part, it would appear probable, at least, that Indian murders would not transpire within gun-shot of his agency at St. Peter’s.

The War Department should adopt immediate measures to break up the sale of whiskey to the Indians on the St. Croix, and other parts of that ceded territory, or very serious consequences will follow. One poor Indian from Fond-du-Lac, on a visit to one of the grogeries on the St. Croix, was made beastly drunk, who, in his helplessness, fell with his face on the fire; having his cheek, with one eye, awfully disfigured and burnt; leaving his whole visage an object of loathing and disgust for life.

As our course to the Mississippi lay along the St. Croix, directly through the whiskey district, the reports of present and prospective difficulties were not very pleasant. We nevertheless made up our minds to persevere, and meet whatever might happen.

Negwanebi (Quill)

Wazhashkokon (Muskrat’s Liver, aka Pítad in Dakota);

Noodin (Wind).

Towards sunset, we made the mouth of the Brulé, where we found about thirty Chippewa Indians with two or three chiefs encamped, who were on their way to La Pointe; from Leech Lake and Mille Lake. They belonged to the band denominated “pillageurs,” so nicknamed from their alleged propensity to steal small matters. We landed on the opposite side of the river to their camp, on a flat – the stream being about twice as wide as the Tiber in good water at Washington. We were soon joined by Captain Stanard, whose men pitched his tent near ours, and cooked supper by the same fire. We had scarcely kindled our camp fire, before the chiefs of the “pillageurs” manned their canoes, and came over, crying out, as they came up; “Bojour,” “bojour,” and giving us their hands, which we accepted. They looked poor and dirty, some of whom were nearly naked. They said they had nothing to eat, and were very hungry, and wished us to give them some flour, which we complied with. No sooner did the rest find out we were dispensing “farine,” as the French voyageurs term it, than the whole [posse?] kept coming over in instalments, till we had the whole camp upon our hands – women, children, and all.

We gave them all round about a pint of flour, from Captain S.’s and our own supply, and then gave them to understand we wished them to retire to their own side of the river; they all left us, except some old chiefs, who were privileged to remain, and appeared desirous of smoking their pipes before our fire, and talking over news with Jocko, our Indian voyageur, and one of Captain S.’s half-breeds.

In their camp opposite – out of joy, I suppose, over the flour we had given them – they commenced beating a drum, and singing in a most wild and monotonous manner, which they kept up till near ten p.m., when all became silent. We all fell fast asleep; and when I awoke next morning, calling the hands for an early start, all was quiet in the Indian camp. Captain Stanard prepared to depart at the same time, and before sunrise he was off to Fond-du-Lac, and we to the Mississippi. Whatever the “pillageurs” may have done elsewhere, we will do them the justice to say that they stole nothing from us; for next morning, on packing up, we missed nothing whatever. Many of them had pleasing and honest countenances, whatever else may be said about them.

Detail of the Bois Brulé River (aka “Wissakude [Wisakoda] or Burnt Wood”) and the portage over the Great Divide (a continential divide between the Lake Superior Basin and Missisippi River Basin) to the Saint Croix River from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

At many places the rapids were so powerful, and the channel so crooked and narrow, that the voyageurs had to wade in the water frequently to their waist, and push the canoes forward with their hands. Sometimes their feet would slip from the spurs of trap-rock boulders, and they would go into holes of deep water, nearly to their arm-pits or chins.

We worked forward in this way over rapids, for about thirty miles; and having passed three portages, around which we had to walk and carry our baggage, with still the fourth and last severe one before us, we finally struck up a camp near the head of the third portage, where all were sufficiently fatigued to sleep most soundly. At this last portage rapid, there appeared in the bottom of the river a mass of trap crossing it, over which the water fell two or three feet nearly perpendicular.

We were off next morning early, after having examined the bottoms of our canoes, and patched and gummed the leaky places with birch bark and Canada balsam-tree rosin. The small canoe had to be patched and pitched two or three times, having been punched with holes by the rocks.

“In consideration of the cession aforesaid, the United States agree to make to the Chippewa nation, annually, for the term of twenty years, from the date of the ratification of this treaty, the following payments.

1. Nine thousand five hundred dollars, to be paid in money.

2. Nineteen thousand dollars, to be delivered in goods.

3. Three thousand dollars for establishing three blacksmiths shops, supporting the blacksmiths, and furnishing them with iron and steel.

4. One thousand dollars for farmers, and for supplying them and the Indians, with implements of labor, with grain or seed; and whatever else may be necessary to enable them to carry on their agricultural pursuits.

5. Two thousand dollars in provisions.

6. Five hundred dollars in tobacco.

The provisions and tobacco to be delivered at the same time with the goods, and the money to be paid; which time or times, as well as the place or places where they are to be delivered, shall be fixed upon under the direction of the President of the United States.

The blacksmiths shops to be placed at such points in the Chippewa country as shall be designated by the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, or under his direction.

If at the expiration of one or more years the Indians should prefer to receive goods, instead of the nine thousand dollars agreed to be paid to them in money, they shall be at liberty to do so. Or, should they conclude to appropriate a portion of that annuity to the establishment and support of a school or schools among them, this shall be granted them.”

“Whereas the whole country between Lake Superior and the Mississippi, has always been understood as belonging in common to the Chippewas, party to this treaty; and whereas the bands bordering on Lake Superior, have not been allowed to participate in the annuity payments of the treaty made with the Chippewas of the Mississippi, at St. Peters July 29th 1837, and whereas all the unceded lands belonging to the aforesaid Indians, are hereafter to be held in common, therefore, to remove all occasion for jealousy and discontent, it is agreed that all the annuity due by the said treaty, as also the annuity due by the present treaty, shall henceforth be equally divided among the Chippewas of the Mississippi and Lake Superior, party to this treaty, so that every person shall receive an equal share.”

Towards noon, we began to find the rapids less frequent and difficult, till we finally came into a beautiful low bottom, or meadow land, of elm trees, which lasted us for many miles; when, towards night, we again passed some severe rapids, and then entered a long lake of irregular width, formed by the expansion of the river at this point – in no case being more than from seventy-five to one hundred yards wide, with generally a swamp on one side, and considerable sloping pine hills or bluffs on the other. We found this river, and especially the lake part of it, to be very full of brook trout, some of which we caught, and found them not only beautiful in color, but most excellent to eat; they were continually jumping above the water. During this day and yesterday, we met several parties of half-breeds and Indians on their way to La Pointe. On inquiring of them about the fight at the falls, and the difficulties at St. Peter’s, they gave us the most favorable accounts of the quiet and peaceful disposition of the Indians, and said that we might travel just where we pleased, without the least danger whatever. At any rate, there was one guarantee of their good conduct for a few weeks to come – and that was the forthcoming payment at La Pointe, to which they go up with as much eagerness as the Jews of old did to the Passover. Any serious disturbance at the present time, or probably at any time, would jeopard the receipt of their annuity, and likely lead to their expulsion from the country. Besides, at the payment they have an opportunity of laying their numerous grievances before the father, who has to promise them to speak for them in the ear of the great father at Washington. So matters progress from one year to another, till many grievances of a minor or trivial nature are forgotten.

We camped on a sloping pine ridge, on the east side of the lake part of the river, about 7 p.m. We found all the nights on the Brulé cool and pleasant. The water throughout we found as cold as the best mountain spring-water.

We continued our ascent at an early hour next morning, and by noon found our little stream very much diminished in size and volume of water, dwindling first into a small creek, and afterwards into a mere meadow-brook, nearly choked up by the hanging and interlocked alder bushes, the limbs of which we had to push out of our way to enable us to pass. The little river on this swampy meadow-land also became very crooked. In going a mile, we very often had to traverse the meadow nearly a dozen times.

“Recreation of a voyageur carrying two 90 lb packs of fur across a portage to avoid rapids or move to another river.”

~ Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway

About half-past 2 p.m., however, we arrived at the portage, or the place where we were to take our canoes out, transport them, and afterwards their contents, on our backs, across hill-sides, and over the summit of one or two pine, sand, and pebble hills, about one hundred and fifty feet above the level of the swamp in which the St. Croix and Brulé head. The two rivers are said to have a common origin in one spring. But the swamp, in which they both head, is no doubt full of springs – some running one way and some running another. This swamp is wide, extending from one river to the other, nearly north and south. On the east side of this swamp, and parallel with it, are found the range of pine hills by the sides, and over the summits of which the portage path crosses. Still to the east of this short range of hills, is a small lake, which empties into the river Brulé at some distance below the portage, called by the voyageurs White-fish lake. Near the head of streams of the St. Croix river is Upper St. Croix lake, to which our portage path descended at the northeast corner, descending to it down the southern side of the hills spoken of, being three miles from the place of debarkation on the Brulé. The sources of these rivers are laid down in Mr. Nicollet’s map as being nine hundred feet above the Atlantic. They are also said to be two hundred and seventy-five feet above the level of the lake; but I am inclined to believe that they are higher than stated – especially so above the level of the lake, if the high land we crossed be included in the estimate. Most of the maps are in error about the geography of this part of the country, both with regard to the heading of the rivers; as well as to their size and course.

The course of the Brulé is from south-southeast to north-northwest from the portage to the lake, being comparatively a small river. The course of the St. Croix, from its head to the Mississippi is south-southwest, and is by no means so crooked low down as represented. It is so large, for fifty or seventy-five miles above the falls, as to compare very favorably with the Ohio; which, at some points, it much resembles. It, and its tributaries, have a deal of fine pine timber growing along its banks; a good deal of which has been cut, to supply the mills below. Mr. Nicollet’s map, which is generally very correct, lays down hills between the waters of the Brulé and St. Croix, where none exist. I believe he did not visit the portage in person, but relied on the information of voyageurs.

It was an agreeable reflection to know, when standing on the highest point of hills on the portage, that we could overlook the course of one river sweeping away to the north, on its vast journey to the Gulf of the St. Lawrence; while to the south were seen the waters of the St. Croix, just gathered into a pretty, quiet lake, from its conglomerate of springs near by about to speed its waters to the Mississippi, and down it to the Gulf of Mexico! and when once there, perchance, gathered in the Gulf stream, and be again wafted by it to the banks of Newfoundland, where it may again unite with the water of its kindred Brulé!

What a wonderful continent is this of ours! What cast rivers and lakes intersect it! To appreciate their lengths, magnitude, scenery, &c., they must be travelled over to be understood. In June, I was at the Falls of Niagara; in a few days I shall probably be at the Falls of St. Anthony – passing from one to the other by water, with the exception of three miles!

Having, on August the 2d, succeeded in getting everything over the portage, including canoes, luggage, &c.; and it being towards sundown; we concluded to camp, and get ready for an early start next morning. Sunday morning, the 3d of August, found us descending the beautiful upper lake St. Croix, bordered in the distance with rolling pine-hills.

Detail of the upper Saint Croix River, Brule Bog portage, and “Chipeway Village” from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River From Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by J.N. Nicollet, 1843. Also shown is the Grand Footpath (long dotted line) between Chequamegon Bay and Saint Anthony Falls.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

We soon began to meet large parties of Indians in their canoes, bound to La Pointe, to be present at the payment. As Mr. Hays (the Indian agent at La Pointe) had told us that he expected the Rev. Mr. Ely, who had charge of a Presbyterian missionary station on the Percagaman, or Snake river, to be over at the payment, and thought it probable that we might meet him; and learning that some of the Indians we met were from Snake river, I asked them if they knew whether Mr. Ely had left. They told me he had, and that he was at his camp down the river, which we would soon reach.

We continued on, amidst fields of wild rice in full bloom, which covered the lake for acres upon acres on each side of the channel. This wild rice (rizania aquatica) is of great importance to the Indians, who gather large quantities of it when ripe, in autumn, for their winter food. Its soft stem and watery roots are immersed about 2 to 2½ feet under water, while the blades, head, and stalk reach about a foot to a foot and a half above water. In flowering, its heads present a singular appearance. Its pistils, or grain part of the flower, are clustered on a long, sharp-pointed spicular, terminating in a sharp cone at the very head of the stalk; while the pollen appears attached to the stalk below the head.

Why could not this rice be sown and cultivated in the lakes of western New York and in New England? Besides the value of the grain for poultry and various other purposes, its tops or blades would make the richest and sweetest fodder for cattle. I chewed the blades, and found them tender, and as sweet as the tender blades of green corn. The experiment might be worth the trial.

About the middle of the afternoon we reached the first rapids in descending the St. Croix, now contracted from a lake into a narrow river, strewed here and there with black boulders of trap. We here had the pleasure of finding Mr. Ely encamped on the west bank of the river, who had remained still all day, as it was Sunday. He had in company with him the Rev. Mr. Rosselle, a young clergyman from Ogdensburg, New York, to whom he introduced me. Mr. Rosselle informed me that he had been to the falls of St. Anthony, from whence he had gone on a steamboat “Still-water,” at the head of the lower Lake St. Croix, and from thence to the missionary station on the Pergacaman, or Snake river, where he concluded to accompany the Rev. Mr. Ely to La Pointe, and be present at the Indian payment. From La pointe he expected to make his way home by the Sault St. Marie, Mackinac, &c. Mr. Ely had some Indians along with him, who were evidently attached to the mission. He said the success of the mission had been interfered with, to some extend, by the dread in which the Chippewas held the Sioux in that part of the country; that in constant fear of their natural enemy, they disliked making permanent settlements and to improve them. After some other general conversation, we continued our journey over rapids, till near night, when we camped (as was often the case) on an old Indian camping-ground, and saw lying about us dog bones, on the meat of which the Indians had feasted. An innumerable swarm of horseflies surrounded our tent and camp-fire, which the voyageurs at first mistook for bumble bees, whose nest, they conceived, they had disturbed, and, for fear of being stung, they fled; but, on ascertaining they were merely noisy flies, they came back again.

We made an early start next morning, to resume our descent over rapids dashing over trap and granite boulders. We met a half-breed and his wife, who had a keg of whiskey in his canoe. They were going to La Pointe, where Mr. Hays suffers no liquor to land. The man offered to treat my voyageurs, one of whom was known to him. I consented that they might take one dram each, but no more. This being given them, we thanked him, and proceeded on our journey. About noon, we passed the last severe rapids, and the mouth of a large tributary from the east, called the Macagon, about 100 miles above the falls, and within 50 miles of Snake river.

Detail of the Saint Croix River with tributaries Snake River and Kettle River from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River From Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by J.N. Nicollet, 1843. Also shown is the Grand Footpath (long dotted line) between Chequamegon Bay and Saint Anthony Falls.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

The St. Croix, from this point down, became a larger, more beautiful, and more interesting stream. The bottoms, too, became wide and rich, but subject to inundation at very high water. The stratified red sandstone was seen to skirt the margins of the river, all along the rapids; while boulders of trap and granite were strewn over the centre of the channel. But, as we approached Kettle and Snake rivers, we began to notice the appearance of white sandstone on the shores of the river, which continued to appear till near the falls, and again rose in high cliffs below them, and continued to the Mississippi. At night, we camped on a high pine bluff on the right bank of the river, a large swamp being on the opposite side. Here we were nearly devoured by mosquitoes, and were glad to make our escape next morning without breakfast – intending to stop and cook at a place, if possible, less infested by them; which we did, on the pebbly beach of an island.

We had a showery forenoon, but continued our journey. We met with several long rapids, and, passing Kettle river, reached the mouth of Snake river, about 10 a.m. – where we found a body of Indians encamped, going to La Pointe. We exchanged some meal for some fish, and gave an old woman some sugar for a sick child. Then, wishing them a “bon voyage,” we put off. About 25 miles above the falls, we passed Sunrise river, with splendid and extensive bottom-land opposite to it on the left bank, lying high and dry above high-water mark.

The next place we made was Wolf river, about 18 or 20 miles above the falls. Here we found a rude village, on a rich piece of land, settled by half-breeds, Indians, and a Frenchman or two. They had lots of liquor, and offered to sell me some; but I declined to purchase, or to let my voyageurs buy any; and, though late in the afternoon, moved for some 8 or 10 miles further, and camped just within the first rapid or two, at the commencement of the falls. From the head of the rapids to the falls is 9 miles.

Detail of Saint Croix Falls with tributaries Sunrise River (“Memokage”) and Wolf Creek (“Attanwa”) from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River From Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by J.N. Nicollet, 1843. Also shown is the Grand Footpath (long dotted line) between Chequamegon Bay and Saint Anthony Falls.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

~ Fifty Years in the Northwest by William H. C. Folsom, 1888, page 87.

We reached the falls next morning to breakfast, where I made the acquaintance of Mr. Purinton, to whom I bore a letter of introduction, and found him a very clever and enterprising man. He has done more to develop this part of the country, and to enhance its value and settlement, than any other man in it. The falls afford a splendid water-power, fully equal to that yielded by the falls of the Merrimac at Lowell. Mr. Purinton is the proprietor, and has a saw-mill running with five saws, in separate frames. His logs come down the St. Croix.

There is a trap formation in place, crossing the river at the falls, obliquely from northwest to southeast. It is lost a short distance to the northwest of the river, but runs off in a range of 20 miles to the southeast of the falls. It differs a good deal from the trap-formation on Lake Superior. It is of a bluish and lighter color than the trap on the lake in the high perpendicular cliffs of this stone, which faces the river at, and for some little distance below the falls, may be seen strong indications of a columnar structure in its form; while in the trap on Lake Superior, the same rock is uniformly amorphous in its form.

Besides, the trap on Lake Superior appears uniformly to have had an upheaval through red sandstone; while that at the falls has been borne up through white sandstone, very distinct in its character from the red sandstone of the lake. It is probable, therefore, that there is no continuous connexion or homogeneousness of character between the trap-rock of the falls, and that on Lake Superior; and that they may have been raised at far different and distinct periods. Be this as it may, however, I found the trap at the falls of St. Croix to give very favorable indications of the existence of copper ore. Mr. Purinton gave me some very interesting specimens of the ore found in the vicinity of his mill.

While rambling about the falls, I discovered, also, one or two very fine mineral chalybeate springs.

Detail of the Saint Croix River from the Falls to the head of Saint Croix Lake (Stillwater, Minnesota) from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River From Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by J.N. Nicollet, 1843. Also shown is the Grand Footpath (long dotted line) between Chequamegon Bay and Saint Anthony Falls (Minneapolis, Minnesota.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

Having paid off my voyageurs at the falls, and sent them back in one of the canoes, I prepared to descend the river to the head of the lake, or to Stillwater, in the other; which I reached next day. There is a saw-mill at this place, and two others between it and the falls – all being turned by streams which enter the river on one side or the other. At Stillwater, a town not quite a year old, there is a tavern, two stores, a blacksmith-shop, one lawyer, one doctor, no preacher, no schoolmaster, no justice of the peace or mayor, one saw-mill, no school, a large cool spring, and a very pretty place for the town to grow on. We here met the steamboat Lynx, on which we took passage, after disposing of my canoe.

The land on the west side of Lake St. Croix is beautiful all the way to the Mississippi, and is fast settling up. This beautiful sheet of water is 22 miles long, and from one and a half to two miles wide.

I am, very respectfully and sincerely, yours,

MORGAN.

To be continued in Copper Harbor Redux…

Wisconsin Territory Delegation: To The Far West

April 4, 2016

By Amorin Mello

The Daily Union was a newspaper in Washington, D.C., now archived online at the Library of Congress, that published a curious series of correspondences with the pen name “Morgan” during 1845. In this series, “Morgan” included a remarkable and vicarious description of his experiences on Lake Superior and at La Pointe. Based on the circumstances and narrative, the identity of “Morgan” is assumed to be Morgan Lewis Martin.

Portrait of Morgan L. Martin Painted by Samuel Marsden Brookes (1816-1892) and Thomas H. Stevenson. Oil on canvas, 1856.

(Wisconsin Historical Museum object #1942.37.) WHI 2786

—

“From the time of his arrival in Green Bay in 1827, Morgan Lewis Martin (1805-1887) was an important figure in Wisconsin. Martin was an organizer of the Wisconsin Democratic Party, a member of the territorial and state legislatures, a delegate to Congress, and a Civil War paymaster. He played a key role in the early development of Milwaukee and for almost fifty years promoted various Fox and Wisconsin River improvement projects. Brookes and Stevenson, a Milwaukee-based partnership, executed this portrait of Martin during a two-month visit to Green Bay in the summer of 1856.”

According to the Biographical Directory of the United States Government:

MARTIN, Morgan Lewis, (cousin of James Duane Doty), a Delegate from the Territory of Wisconsin; born in Martinsburg, Lewis County, N.Y., March 31, 1805; attended the common schools and was graduated from Hamilton College, Clinton, N.Y., in 1824; studied law; was admitted to the bar and commenced practice in Detroit, Mich.; moved to Green Bay, Wis., in 1827 (then a part of Michigan Territory); member of the Michigan Territorial legislature 1831-1835; member of the Wisconsin Territorial legislature 1838-1844 and served as president in 1842 and 1843; elected as a Democrat to the Twenty-ninth Congress (March 4, 1845-March 3, 1847); president of the second State constitutional convention in 1847 and 1848; again elected to the State assembly in 1855; member of the State senate in 1858 and 1859; served in the Union Army as paymaster with the rank of major 1861-1865; Indian agent 1866-1869; unsuccessful candidate for election in 1866 to the Fortieth Congress; resumed the practice of his profession; elected judge of Brown County in 1875, in which capacity he served until his death at Green Bay, Brown County, Wis., December 10, 1887; interment in Woodlawn Cemetery.

Shortly before Morgan Lewis Martin was elected to the 29th Congress, the Territory of Wisconsin passed the following Joint Resolution:

JOINT RESOLUTION relative to Mail Routes.

Resolved by the Council and House of Representatives of the Territory of Wisconsin:

That our Delegate in Congress be requested to procure the establishment of a mail route from Janesville to Racine on the United States road between those places; also one from Racine to Prairie Village in Millwaukee county; and also one from Wheatland to Racine both in the county of Racine; also one from Mineral Point in Iowa county by way of Shullsburg and New Diggings to White Oak Springs in Iowa county, also one from Madison in Dane county via Sun Prairie, Columbus, and Beaver. 113 dam to Waupun in Fond du Lac county; also one from the falls of St. Croix [to] La Point on Lake Superior; also one from Prairieville in Milwaukee county by the way of Lisbon to Limestone in Washington county; also one from Potosi by way of Hurricane and Cassville to Patch Grove in Grant county; also one from Fond du Lac, Fond du Lac county, by the way of Ceresco and Green Lake to Fort Winnebago in Portage cou nty; also one from Madison to Prairie du Chien in Crawford county -by the most direct route; also, one from Plattville in Grant county by Jamestown to Fairplay, and from Fairplay by Hazel Green to White Oak Springs in Iowa county; also, one from Millwaukee by Lisbon, Warren, Oconomewoc, Watertown and Sun Prairie to Madison ; and also, one. from Milwaukee by Hustis Rapids to Fort Winnebago; also, one from Milwaukee via Whitewater and McFadden, on Sugar River to Mineral Point.

APPROVED, February 15, 1845.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

June 19, 1845.

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE

—

[From our regular correspondent.]

NEW YORK, June 16, 1845.

We have had two arrivals from China, bringing dates as late as the 13th of March; but the papers received are said to contain little news of interest. Trade was represented as dull, except for gray cotton cloth and yarn.

Photographic copy of an 1845 daguerreotype featuring 78 year-old Andrew Jackson (seventh President of the United States) shortly before his death. ~ Commons.WikiMedia.org

The announcement of General Jackson’s death reached this city yesterday afternoon, and produced the deepest feelings of regret among thousands of people. The flags on the shipping in port, and at all the places of public resort, were immediately hoisted at half-mast, as the news spread by extra newspapers over the city like an electric shock. No doubt, arrangements will be speedily made to commemorate his death, and to express the sorrow of the people for the fall of so great a patriot, by every kind of suitable demonstration.

It is seldom in the annals of history that such men as Gen. Jackson rise up and stand out so prominently from the mass of mankind. Whatever else may be thought of him, his devoted love of country, his integrity of purpose, his Christian purity and benevolence can never be questioned by any one.

I have no general news of importance to note. Trade and stocks are dull; without material change in either since my last. Indeed, we have no change to expect till the arrival of the news by the Boston and Liverpool steamer, which is now daily looked for.

I must make my letter brief to-day, as I am about getting ready for a trip to the “far West,” and when you hear from me again, it will be en route towards sunset.

Yours, very truly and respectfully,

MORGAN.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

June 24, 1845.

EDITOR’S CORRESPONDENCE

—

[From our regular correspondent.]

BUFFALO, N. Y., June 19, 1845.

“Niagara, Hudson River steamboat built 1845.” Painting by James Bard.

I left New York at 7, a.m. yesterday morning, on board the splendid new steamboat called “Niagara,” on her first trip to Albany as a day-boat. She is 275 feet long on her keel, and 285 long on her main deck. Her large engine has a stroke of 11 feet; the main cylinder is 72 inches in diameter. She is fitted up like a palace. She ran the distance from New York to West Point, about 55 or 60 miles, in six minutes less than three hours. No boat runs as well when perfectly new, as when the portions of machinery subject to much friction have been worn smooth. The “Niagara” put us down in Albany a little before 5, p.m. Here we had to wait till 8, p.m., before a train left carrying us west towards Buffalo. We travelled all night, and reached the latter place, 584 or 585 miles, in 36 hours from New York; or, subtracting delays, in the remarkable short space of 30 hours, running time!

I slept as well as I could in the cars; and am here, at half-past 10, p.m., after a fatiguing thirty-six hours’ travel, sitting down trying to indite something for the “Union;” but, from a heavy feeling in my eye-lids, I fear I may make a drowsy affair of it.

“Map of the rail roads, from Rome to Albany and Troy, by one of the engineers who assisted in constructing, prepared from actual survey.” By Levi William, 1845. Digitized by the Library of Congress.

I found the western part of New York, and especially the country west of Utica, much better than I anticipated. The country looked new, for one of the old thirteen. As populous as the State is, western New York contains still much virgin soil to come into cultivation.

The staple productions appear to be wheat, rye, oats, potatoes, barley, &c. The first article is the greatest of all. The valley of the Mohawk is an interesting section of New York; but I think the country lying on the Genesee valley, and bordering the lakes of Cayuga, Seneca, and Canadaigua, c., by far the most interesting – and that portion especially about Seneca Falls, Waterloo, &c. The crops looked remarkably well in color, &c.; but seemed generally rather backward for the season. Wheat has headed very well, but does not appear very high, or to stand very thick on the ground, except in places, as the English farmers express it, I think “the heads of grain may be large and full,” if nothing happens; but “the straw will be light.”

After leaving Albany, the first place we stopped at of any note was Utica – 93 miles west of that town. It contains about 12,000 inhabitants, and is quite a well-built and pretty place. It is in Oneida county, much of which has been settled by industrious Welsh farmers. The county cast a majority of about 700 votes for the democratic electoral ticket last November.

As it was 3 o’clock at night when we reached Utica, we walked out to look at the place by moonlight, and were much pleased with its appearance.

From Utica we pushed on from village to village, bearing a variety of ancient Indian, Greek, and Roman names, till we were set down at this point.

As the country is familiar to many, and has been often described, I may have, in my next, to say something more about it. At present, I must close, or fall asleep over the paper.

Yours, very respectfully,

MORGAN.

P.S. I visit Niagara Falls to-morrow, and expect to return the same day, in time to take a boat (the St. Louis) at seven in the evening for Detroit, Michigan.

The Daily Union (Washington D.C.)

“Liberty, The Union, And The Constitution.”

July 1, 1845.

[From our regular correspondent.]

DETROIT, MICHIGAN, June 24, 1845.