Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

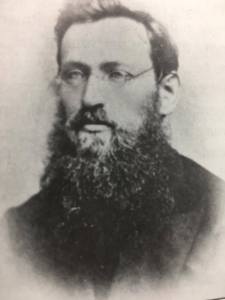

Bishop Irenaeus Frederic Baraga

~ Madeline Island Museum

This post features oral legends recorded about two of Bishop Irenaeus Frederick Baraga’s traverses from La Pointe across Lake Superior:

A) to Minnesota’s Cross River by canoe.

B) to Michigan’s Ontonagon River by ice.

In chronological order of publication, the first record was from a German traveloguer, the next two were from Catholic missionaries, and the last two were from Bad River tribal members.

- Kitchi-Gami, by Johann Georg Kohl, 1859/1860.

- Life and Labors of Bishop Baraga, by Rev. Chrysostom Verwyst, 1896.

- Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederick Baraga, by Rev. Verwyst, 1900.

- Chippewa Indian Historical Project, by United States WPA, 1936-1942.

- Chippewa Indian Historical Project, by United States WPA, 1936-1942.

Translated and republished in English as

Kitch-Gami: Wanderings Round Lake Superior,

By Johann Georg Kohl, 1860,

Pages 180-183.

German traveloguer

Johann Georg Kohl

“Dubois“ was apparently a pseudonym in Kohl’s book. The true identity of this “well-known Voyageur“ gets revealed in our other records.

Du Roy: “Do you known the summer voyage our most reverend friend, your companion, once made in a birch-bark canoe right across Lake Superior? Ah! that is a celebrated voyage, which everybody round the lake is acquainted with. Indeed, there is hardly a locality on the lake which is not connected with the history of his life, either because he built a chapel there, or wrote a pious book, or founded an Indian parish, or else underwent danger and adventures there, in which he felt that Heaven was protecting him.

“The aforesaid summer voyage, which I will tell you here as companion to his winter journey, was as follows:

“He was staying at that time on one of the Islands of the Apostles, and heard that his immediate presence was required at one of the little Indian missions or stations on the northern shore of the lake. As he is always ready to start at a moment, he walked with his breviary in his hand, dressed in his black robe, and with his gold cross fastened on his breast – he always travels in this solemn garb, on foot or on horseback, on show-shoes or in a canoe – he walked, I say, with his breviary in his hand and his three-corned hat on his head, into the hut of my cousin a well-known Voyageur, and said to him: ‘Dubois, I must cross the lake, direct from here to the northern shore. Hast thou a boat ready?’

” ‘My boat is here,’ said my cousin, ‘but how can I venture to go with you straight across the lake? It is seventy miles, and the weather does not look very promising. No one ever yet attempted this “traverse” in small boats. Our passage to the north shore is made along the coast, and we usually employ eight days in it.’

” ‘Dubois, that is too long; it cannot be. I repeat it to thee. I am called. I must go straight across the lake. Take thy paddle and “couverte,” and come!’ And our reverend friend took his seat in the canoe, and waited patiently till my obedient cousin (who, I grant, opened his eyes very wide, and shook his head at times) packed up his traps, sprang after him and pushed the canoe on the lake.

“Now you are aware, monsieur, that we Indians and Voyageurs rarely make greater traverses across the lake than fifteen miles from cape to cape, so that we may be easily able to pull our boats ashore in the annoying caprices of our weather and water. A passage of twenty-five or thirty miles we call a ‘grand traverse,’ and one of seventy miles is a impossibility. Such a traverse was never made before, and only performed this once. My cousin, however, worked away obediently and cheerfully, and they were soon floating in their nutshell in the middle of the lake like a loon, without compass and out of sight of land. Very soon, too, they had bad weather.

“It began to grow stormy, and the water rose in high waves. My cousin remarked that he had prophesied this, but his pious, earnest passenger read on in his breviary quietly, and only now and then addressed a kind word of encouragement to my cousin, saying that he had not doubted his prophecy about the weather, but he replied to it that he was called across the lake, and God would guide them both to land.

“They toiled all night through the storm and waves, and, as the wind was fortunately with them, they moved along very rapidly, although their little bark danced like a feather on the waters. The next morning they sighted the opposite shore. But how? With a threatening front. Long rows of dark rocks on either side, and at their base a white stripe, the dashing surf of the terribly excited waves. There was no opening in there, no haven, no salvation.

” ‘We are lost, your reverence,’ my cousin said, ‘for it is impossible for me to keep the canoe balanced in those double and triple breakers; and a return is equally impossible, owing to the wind blowing so stiffly against us.’

” ‘Paddle on, dear Dubois – straight on. We must get through, and a way will offer itself.’

“My cousin shrugged his shoulder, made his last prayers, and paddled straight on, he hardly knew how. Already they heard the surf dashing near them; they could no longer understand what they said to each other, owing to the deafening noise, and my cousin slipped his couverte from his shoulders, so as to be ready for a swim, when, all at once, a dark spot opened out in the white edge of the surf, which soon widened. At the same time the violent heaving of the canoe relaxed, it glided on more tranquilly, and entered in perfect safety the broad mouth of a stream, which they had not seen in the distance, owing to the rocks that concealed it.

” ‘Did I not say, Dubois, that I was called across, that I must go, and that thou wouldst be saved with me? Let us pray!’ So the man of God spoke to the Voyageur after they had stepped ashore, and drawn their canoe comfortably on the beach. They then went into the forest, cut down a couple of trees, and erected a cross on the spot where they landed, as a sign of their gratitude.

“Then they went on their way to perform their other duties. Later, however, a rich merchant, a fur trader, came along the same road, and hearing of this traverse, which had become celebrated, he set his men to work, and erected at his own expense, on the same spot, but on a higher rock, a larger and more substantial cross, which now can be seen a long distance on the lake, and which the people call ‘the Cross of —–‘s Traverse.’”

LIFE AND LABORS OF BISHOP BARAGA

A short sketch of the life and labors of Bishop Baraga

The Great Indian Apostle of the Northwest.

By Rev. Chrysostom Verwyst O.S.F. of Ashland, Wis.

Father John Chebul arrived on Lake Superior at the Sault in October 1859 to assist his fellow Slovanian Bishop Baraga. Chebul spent the winter at Ontonagon with miners before arriving at La Pointe in May 1860.

On another occasion Father Baraga went to Ontonagon from La Pointe. We will relate the incident as told to the writer by Rev. John Cebul, of Newberry, Mich. He was well acquainted with Bishop Baraga, being a fellow countryman who had been sent to La Pointe in 1860, where he labored amongst the Chippewas of that island and Bayfield, Bad River Reserve, Superior and other places, for about thirteen years, being universally loved and esteemed by all. He says:

Baraga’s faithful “man from the island“ is identified as two different men in these stories.

“Cadotte point, about 20 or 30 miles from Ontonagon“ appears to be near the Porcupine Mountains.

Bishop Baraga was intending to go on the ice to Ontonagon. He was accompanied by a man from the island. The reason they took to the ice was because it was much nearer and the walking a great deal better than on the main land. During March and April the ice on Lake Superior becomes honey-combed and rotten. If a strong wind blows, it cracks and moves from the shore if the wind blows from the land. Such fields of ice does not notice that he is in danger till he comes to the edge of the ice and then to his horror discovers a large expanse of open water between him and the mainland. Should the ice float out towards the middle of the lake or break up, he is lost. Father Baraga and his companion had traveled on the ice for some time, thinking all was right. All at once they came to the edge of the ice and saw it was impossible to reach land, as the wind had driven the ice from the shore out into the Lake. His companion became greatly alarmed. Father Baraga remained calm, praying, no doubt, fervently to Him who alone could save them. Finally the wind changed and drove the cake of ice on which they were floating to the shore. They landed at Cadotte point, about 20 or 30 miles from Ontonagon, having been carried by the wind on their ice raft about sixty miles. “See,” said the good priest to his companion, “we have traveled a great distance and yet have not labored.” It seems the good God wanted to save the saintly missionary a long and painful walk, by giving him a ride of sixty miles on a cake of ice.

“Louis Gaudin“ was one of several legendary children born to Jean Baptiste Gaudin, Sr. and Awenishen (a sister of Hole-in-the-day):

– Antoine Gordon

– Elizabeth (Gordon) Belanger

– Louison Gordon, Sr.

– Harriet (Gordon) Lemon

– John Baptiste Gordon, Jr.

– Angelique Gordon

– Joseph Gordon

Louison Gordon, Sr. (1814-1899) married Julia Brebant, whose sisters were married to Henry Bresette and Judge John W. Bell.

Wizon is an objibwecized form of the francophone name Louison.

Undated photo from the Gordon Museum thought to be a brother of Antoine Gordon:

possibly Louis Gordon?

Chippewa Entrepreneur

Antoine Gordon

~ Noble Lives of a Noble Race (pg. 207) published by the St. Mary’s Industrial School in Odanah, 1909.

We learn from F. Baraga’s letter, written in October, 1845, that he intended to go to Grand Portage, Minn., the next fall to build a church there. It is, therefore, highly probable that he made that trip in the fall of 1846. He first went to La Pointe, where, no doubt, he spent some time attending to the spiritual wants of the good people. He then engaged a half-breed Indian, named Louis Gaudin, to go with him to Grand Portage. They had but a small fishing boat with a mast and sail, without keel or centre-board. Such a boat might do on a river or small lake, but would be very unsafe on a large lake, where it would easily founder or be driven lake a cork before the wind. The boat was but eighteen feet long. When they started from La Pointe, the people laughed at them for attempting to make the journey. They said it would take them a month to make the voyage, as they would have to keep close to the shore all the way, going first west some seventy miles to the end of the lake and then, doubling, turn northward, coasting along the northern shore of Lake Superior. this would make the distance about two hundred miles, perhaps even more.

However, Father Baraga and his guide set out on their perilous journey. At Sand Island they awaited a favorable wind to cross the lake, which is about forty miles wide at that place. By so doing they would save from eight to one hundred miles, but would expose themselves to great danger, as a high wind might arise, whilst they were out on the open lake, and engulf their frail bark.

They set sail on an unusually calm day. Father Baraga steered and Louis rowed the boat. Before they got midway a heavy west wind arose and the lake grew very rough. They were constantly driven leeward and when they finally reached the north shore they were at least thirty miles east of their intended landing place, having made a very perilous sail of seventy miles during that day.

While in the height of the storm, in mid-ocean, it might be said, Louis became frightened and exclaimed in Chippewa to the Father, who was lying on his back in the boat, reciting his office in an unconcerned manner: “Nosse, ki ga-nibomin, gananbatch” – Father, perhaps we are going to perish!” The Father answered quietly: “Kego segisiken, Wizon” (Chippewa for Louis) – “Don’t be afraid, Wizon; the priest will not die in the water. If he died here in the water the people on the other shore, whither we are going, would be unfortunate.”

When nearing the north shore the danger was even greater than out on the open water, for there were huge breakers ahead. Louis asked the Father whither to steer, and, as if following a certain inspiration, F. Baraga told him to steer straight ahead for the land. Through a special disposition of Divine Providence watching over the precious life of the saintly missionary, they passed through the breakers unharmed and ran their boat into the mouth of a small river, heretofore unnamed, but now called Cross River.

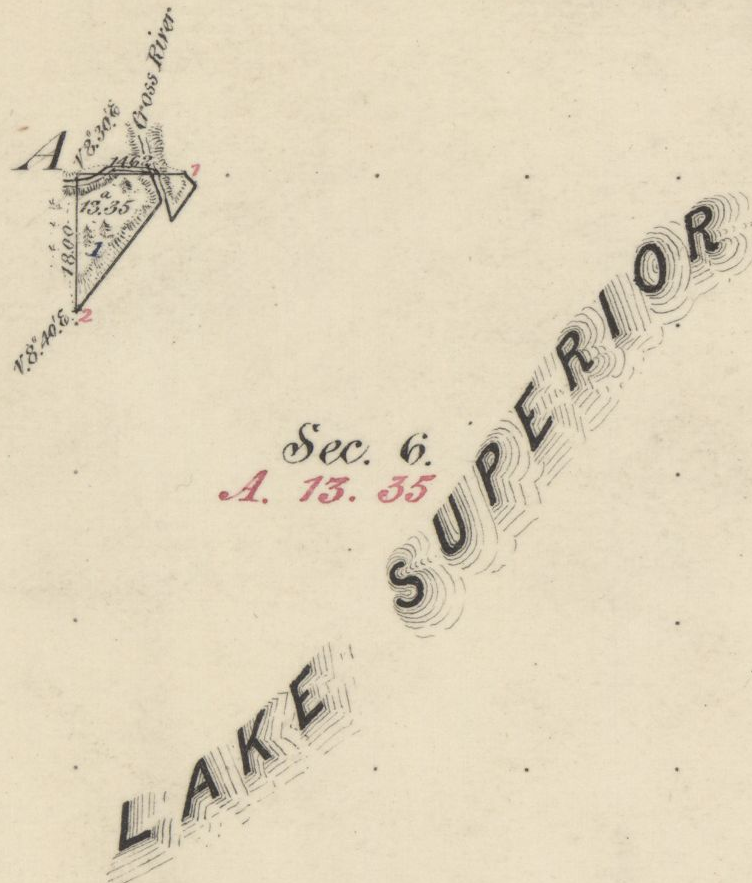

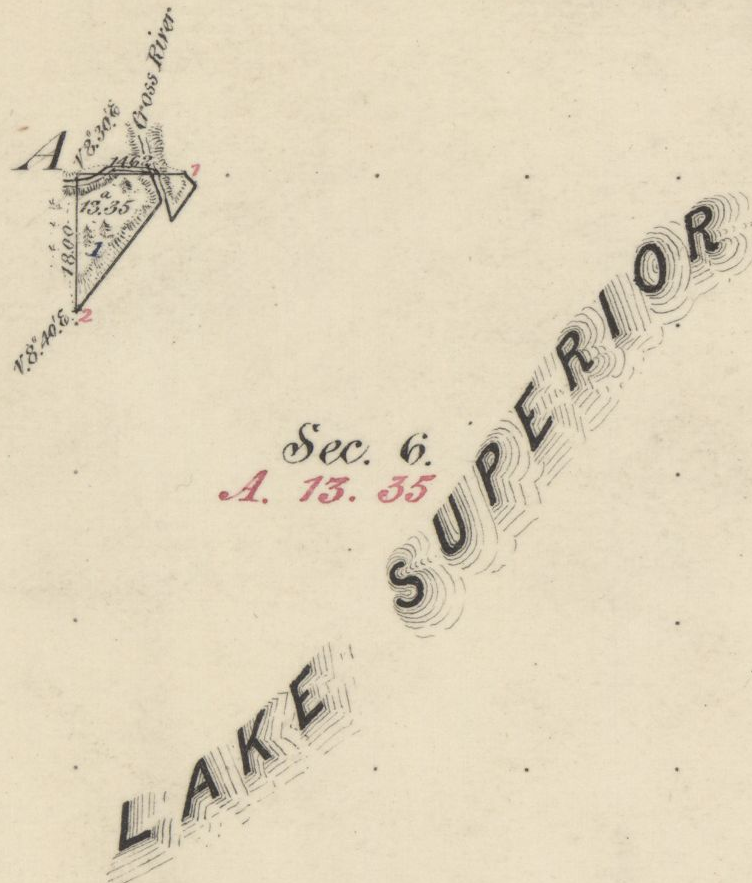

1859 PLSS detail of trees at the mouth of “Cross River”.

Full of gratitude for their miraculous escape, they at once proceeded to erect a cross. Hewing a tree in a rough manner, they cut off the top as far up as they could reach, and taking a shorter piece, they nailed it cross-wise to the tree. “Wizon,” said the Father, “let us make a cross here that the Christian Indians may know that the priest coming from La Pointe landed here.” The cross was, it is true, unartistic, but it was emblem of their holy faith and it gave the name, Tchibaiatigo-Sibi, “Cross River,” to the little stream where they landed.

They arrived none too soon. Ascending an eminence and looking out on the immense lake they saw that the storm was increasing every moment; high waves with white caps, which would surely have engulfed their little bark. They landed about six o’clock in the evening. Having spent the night there, they continued their journey next day, and in two days arrived at Grand Portage, having made the whole journey in three days. May we not think with Louis Gaudin that their safe passage across the stormy lake, and their deliverance from a watery grave, was due to a special intervention of Divine Providence in favor of the saintly missionary?

In 1667 Father Claude Allouez, S. J., then stationed at the mission of the Holy Ghost at the head of Chequamegon Bay, made the voyage across the lake from Sand Island. He made the voyage in a birch-canoe with three Indians. He remarks that they paddled their canoe all day as hard as they could without intermission, for fear of losing any of the beautiful calm weather they had. It took them twelve hours to make the trip across. The Father was then on his way to visit some Christian Indians residing at Lake Nipigon – “Animibigong” in Chippewa. For the particulars of this journey we refer the reader to “Missionary Labors of Fathers Marquette, Allouez, and Menard in the Lake Superior Region.”

The following narrative is not to be found in any of Baraga’s published letters, but the writers has it from the mouth of trustworthy persons, among whom is Father Chebul, a countryman of F. Baraga, who was stationed at Bayfield for many years. We will give the account, as we have it from Rev. F. Chebul.

Francois Newago, Sr. is the “man named Newagon” from Madeline Island, as his children were still young teenagers then.

One time F. Baraga was going to Ontonagon in company with an Indian half-breed in the month of March or April. At that season of the year the ice, though thick, becomes honey-combed and rotten. Some say that Baraga’s companion was a man named Newagon. They went on the ice at La Pointe Island. As the walking on the sandy beach would have been very fatiguing and long, they determined to make straight for Ontonagon over the ice. By so doing they would not only have better walking, but also shorten their way a great deal.

A strong southwest wind was blowing at the time, and the ice, becoming detached from the shore, began drifting lakeward. After they had traveled for some time, they became aware of what hat happened, for they could see the blue waters between them and the shore. Newagon became greatly alarmed, for almost certain death stared them in the face. Had the wind continued blowing in the same direction, the ice would have been driven far out into the lake and broken up into small fragments. They would surely have perished.

To encourage the drooping spirit of his companion, F. Baraga kept telling him that they would escape all right and that they must trust in God, their loving Father and Protector. He also sang Chippewa hymns to divert Newagon’s attention and calm his excitement. Finally the wind shifted and blew the field of ice back towards the shore.

1847 PLSS detail of brownstone points, village, cross, and trailhead at the mouth of Iron River.

“Cadotte Point, near Union Bay“

appears to be located at what is now

Silver City at the

mouth of Iron River and eastern trailhead to the Porcupine Mountains.

Michel Cadotte, Sr. ran a trading post by the Old French Fort on Madeline Island around 1800 and smaller stations scattered along the Wisconsin / Michigan shoreline of Lake Superior. Cadotte first worked for the British North West Company and later the American Fur Company after The War of 1812.

They landed near Cadotte Point, near Union Bay, a short distance from Ontonagon, which they reached that same day. “See,” said the missionary to his companion, “we have traveled a great distance and have worked little.” The distance from La Pointe to Ontonagon is about sixty or seventy miles by an air line. Had they been obliged to walk the whole distance around the bend of the lake, it would probably have taken them two or three days of very hard and fatiguing traveling. So what at first seemed to threaten certain death was used by God’s fatherly providence to shorten and facilitate the saintly priest’s journey.

United States. Works Progress Administration:

(Northland Micro 5; Micro 532)

Reel 1, Envelop 3, Item 5

BISHOP BARAGA’S TRIP TO ONTONAGON

As related by William Obern to John Teeple.

William Henry Obern’s grandparents were

Francois Belanger, Sr.

and Elizabeth (Gordon) Belanger. The Belanger Settlement was founded by their son Frank Belanger, Jr. and Elizabeth (Morrow) Belanger.

The journey I am about to describe is taken from the many experiences of Bishop Baraga, which were related to me by my grandfather. It deals with a journey made at an almost impossible time for ice travel on any of the Great Lakes, and portrays the important part the elements can play in a man’s life, for good or bad, for weal or for woe, as well as Bishop Baraga’s unfaltering confidence in Divine Providence.

Baraga’s guide Louis Gordon was Obern’s great-uncle.

The season of the year in which this incident took place was in the spring – along in April. Bishop Baraga and his faithful guide, Louis Gordon, started from LaPointe enroute to Ontonagon, Michigan, a distance of some eighty or ninety miles from LaPointe, straight across as the crow flies over the frozen water of Lake Superior. Dogs were used to a very large extent in those days for the purpose of transportation.

On account of the prevailing soft weather, the ice on the lake was not very solid, and with the right kind of wind, a general break-up was apt to occur at any time. In this instance, when the Bishop and his guide were about ten miles from LaPointe a south-west wind began to blow, increasing in velocity with each passing hour. The ice broke away from the shore, and began drifting outward into the open waters of Lake Superior, carrying its passengers with it. The guide, seeing the danger, suggested to the Bishop that they land on one of the islands, but the Bishop told him not to worry and to keep going in the direction of Ontonagon; that with the help of God they would reach their destination in safety.

With the coming of night the wind increased, and the two travelers were drifting out into the open waters with considerable speed. Soon the mainland was lost to view, and the guide knew that to remain on the ice mean ultimate death by freezing or drowning, but it was too late to do anything now. They had passed up the opportunity of getting off.

The missionary told Louis to look out for the dogs, and after taking a lunch, he wrapped himself up and went to sleep. He advised the guide to do likewise. The guide wrapped himself up, but he did not sleep. He kept constant vigil; about midnight the wind changed, coming from the opposite direction.

The guide woke Bishop Baraga, telling him that the wind had changed. The priest asked his guide from what direction it was blowing, and upon being told that it was coming from the north-east remarked, “It is just what I hoped for and suspected.” He again told his guide to lie down and go to sleep, but the guide fearing that the plate of ice they were on might break up, would not sleep. They began to drift back almost in the same direction they had come, and when daylight came the outline of the Porcupine Mountains could be plainly seen in the distance. They were traveling at a very high rate of speed, and about mid afternoon they landed on the south shore of Lake Superior, one mile from Ontonagon, their destination.

“There,” said the bishop after they got off the ice and stepped on to the mainland, “this is just what I expected.”

At the time of this narrative, Ontonagon was a small settlement of Indians with but a few white men, who were engaged in the fur trade with the Indians and represented the American Fur Company.

* According to the description furnished by the guide, the piece of ice they were on was about one hundred by two hundred feet.

United States. Works Progress Administration:

(Northland Micro 5; Micro 532)

Reel 1, Envelop 3, Item 6

Cross River

ORIGIN OF THE NAME

Related by William Obern

To John Teeple.

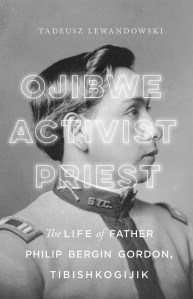

The story I am about to relate deals with an incident of one of the many experiences of Bishop Baraga. The narrative was related to me by my grandmother, Elizabeth Bellanger, who before her marriage was Elizabeth Gordon. She was a blood relative of Father Philip Gordon. The Gordon family consisted of the parents; sons, John, Louis and Antoine, and daughters My grandmother (Elizabeth) and Angelique.

Louis Gordon acted as the guide and all-around servant of Bishop Baraga, the missionary priest. The latter had a very large territory to cover; the northern and southern shores of Lake Superior, thence to the Dakotas and down to the waters known as Chippewa River, which emptied into the Mississippi below St. Paul.

Louis Gordon, the guide, (my grand-uncle) told of many of the experiences he had on these trips with Bishop Baraga. In speaking of my grand-uncle, Louis Gordon, I wish to state first, upon my honor as a gentleman, that he was a Christian in every sense of the word; he never took a drink of intoxicating liquor in his life; and never used profane language.

The stories related to me by my grandmother I well remember, and coming from a man like my grand-uncle, I believe them.

One day Bishop Baraga and his guide, Louis Gordon, started from LaPointe, on the western end of Lake Superior, near the place now known as Bayfield, on the shore of the lake, and about twenty-five miles from the present city of Ashland. At the time of this incident there were no white settlements to speak of at the western end of Lake Superior and the “head of the lakes” region. Bayfield, Washburn, Ashland, Superior and Duluth did not exist in those days. There were few white men among the Indians, and those few represented the American Fur Company. A few, mostly Frenchmen, had in former years settled in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

As formerly stated the trip started from LaPointe. It was to be made by water, and the boat used by the missionary and his guide, from the description given, could not have been more than 16 or 18 feet long. It was just large enough to accommodate the Bishop and his guide and to take care of their camping equipment, and although small, it came out the victor in many storms, proving itself quite seaworthy. These voyagers had a make-shift sail, which furnished them power when the wind was fair, probably a blanket which was raised on a pole; but in calm weather, or when the seas became too rough, the craft was usually propelled with oars. Wind and weather conditions in those days controlled lake travel largely, and when the lake became too rough and the seas too choppy, the voyageurs usually made a landing in some bay or stream outlet.

In this instance, the missionary and his guide were headed for Grand Marias, on the north shore of Lake Superior, a distance of fifty or fifty-five miles from the group of islands known as “Apostle Islands.” Leaving LaPointe, it was necessary for them to cross Lake Superior, traveling directly North. In the event of a severe storm, there is, of course, no place for shelter in the open waters of Lake Superior, and when once started it was necessary for them to continue their voyage until they reached Grand Marias, the point of their destination.

When the Bishop and his guide were about to leave the Apostle Islands, Louis Gordon, the guide, said to Bishop Baraga: “No-say,” (meaning father in Chippewa), “it would not be safe for us to cross the lake in this small boat today. The wind is from the south-west, and it is getting stronger. The lake will become very rough, the seas high, and I am afraid we may perish if we venture out in this wind. We had better not leave this island today, or else follow the south shore around to the end of the lake, so we can find a place to land should the seas become too rough.”

Bishop Baraga replied, “My son, have faith in God. Across that lake my Indians are waiting they must be expecting me, and it is my duty to get there as soon as possible. It would be a waste of time for us to go along the south shore, then along the north shore from the St. Louis River to Grand Marias, when we can cross here and save many miles of hard rowing and precious time. We will trust in God and make the crossing in safety.”

So, Louis Gordon, having unbounded faith in the Bishop, obeyed him, and they began their voyage across the lake, notwithstanding the fact that the wind was increasing in fury and the seas becoming higher and rougher with each passing moment. After they got into the open waters, the guide had considerable difficulty in manning the boat and keeping it from being swamped by the breaking seas. He stood up, and turning to Bishop Baraga said, “No-say, we will never reach the shore.” The Bishop was sitting at the stern of the boat, reciting his breviary. “Louis,” he said, “do not lose faith in God; fear not, He is with us.” The guide was kept busy in keeping the boat in its course, and bailing it out, to prevent it from being filled as the white caps would break over it. He headed it to a point west of Grand Marias in order that he might be better able to ride the crest of the seas, praying and hoping that when they reached the shore, which he hoped would be before dark, they would find a place to land in safety.

I wish to state here that I have seen the north shore of Lake Superior. After leaving Duluth, going east along the north shore, one will find a very rugged shore, ledges of rock from 20 to 200 feet in height standing perpendicularly along the shore line. In these rock ledges are great caves that have been fashioned by angry waves of Lake Superior during centuries. To fully appreciate this story it is well for the reader to know a little concerning the dangers of Lake Superior. Salt-water sailors who have been on the five oceans prefer to be on the ocean in a storm rather than on Lake Superior. The fact that Lake Superior is more dangerous than the oceans is conceded by sailors generally, particularly in the fall of the year. In the ocean, the billows are longer with great spaces between them; while on Lake Superior they are short, choppy, and heavy; and create much more hazard.

Night overtook the missionary and the guide before they reached the north shore; the wind became stronger and the billows higher. The only light they had to guide them was the distant glimmer of the stars, and the guide was able to keep his course by keeping his craft nosed in the direction of the North Star.

After many hours of hard pulling on the oars, the guide knew that they were reaching the shore because he was familiar with the shoreline, and knew that the noise which was all but deafening was created by the breakers dashing against the rock-bound shore.

The guide said to his companion, “No-say, we are nearing the shore, but I am sure we are many miles from Grand Marias. There is no river known in this region and on account of the precipitous formation of the shore line, we have no place to land in safety in this storm.” Bishop Baraga answered, “My son, do as I say, and we will make a landing in safety.” The guide obeyed. His hand were blistered; his strength was leaving his body, but he managed to keep up his struggle against the angry seas. The back-wash created by the billows dashing against the perpendicular rocks of the shore-line made conditions more perilous. The guide said, “Father, there is nothing but certain death ahead of us. We cannot survive this storm.” The noise was so great that it was impossible for the two voyagers to hear each other without shouting, though they were only fifteen or sixteen feet apart; but the Bishop simply said, “Louis, keep going straight ahead.”

Much water had entered their little boat, and it was coming in faster now that they were nearing the ledges of rocks, and the seas, augmented by the back-wash, were becoming rougher, so that destruction seemed imminent. Then amid the tumult and tossing of the boat upon the choppy seas, the boat was suddenly driven from the rough sea into tranquil waters, seemingly guided by some supernatural power. The guide knew that the craft was not being directed by his efforts, and that they were nearing the shore with each sweep of the waves. To his amazement, the boat grounded, and by feeling the depth of the water with his oar he knew that they were in shallow water, but he was unable to determine whether they were in a cave or at the mouth of some stream.

“Father,” Louis cried delightedly, “it seems to me that we are in a cave or at the mouth of some stream, because by feeling around with my oar I can feel a current coming from the land direction.” The missionary then told him to take out their bundle, and light the lantern so that they could see where they were and explore their surroundings.

After lighting the lantern, they made a survey of their surroundings and found that they were at the mouth of a large stream. They climbed out of the river and to higher ground, and there made their camp for the night.

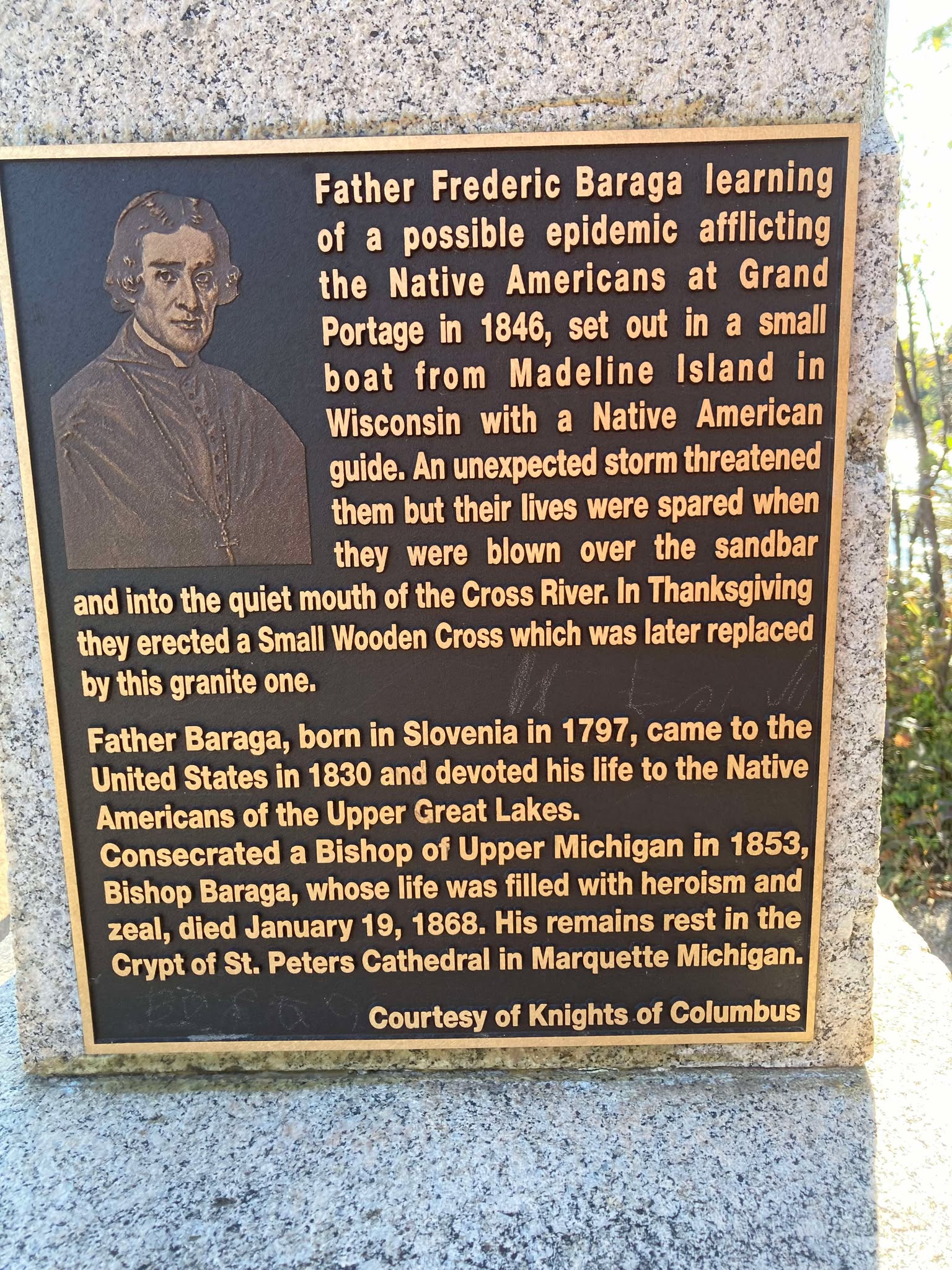

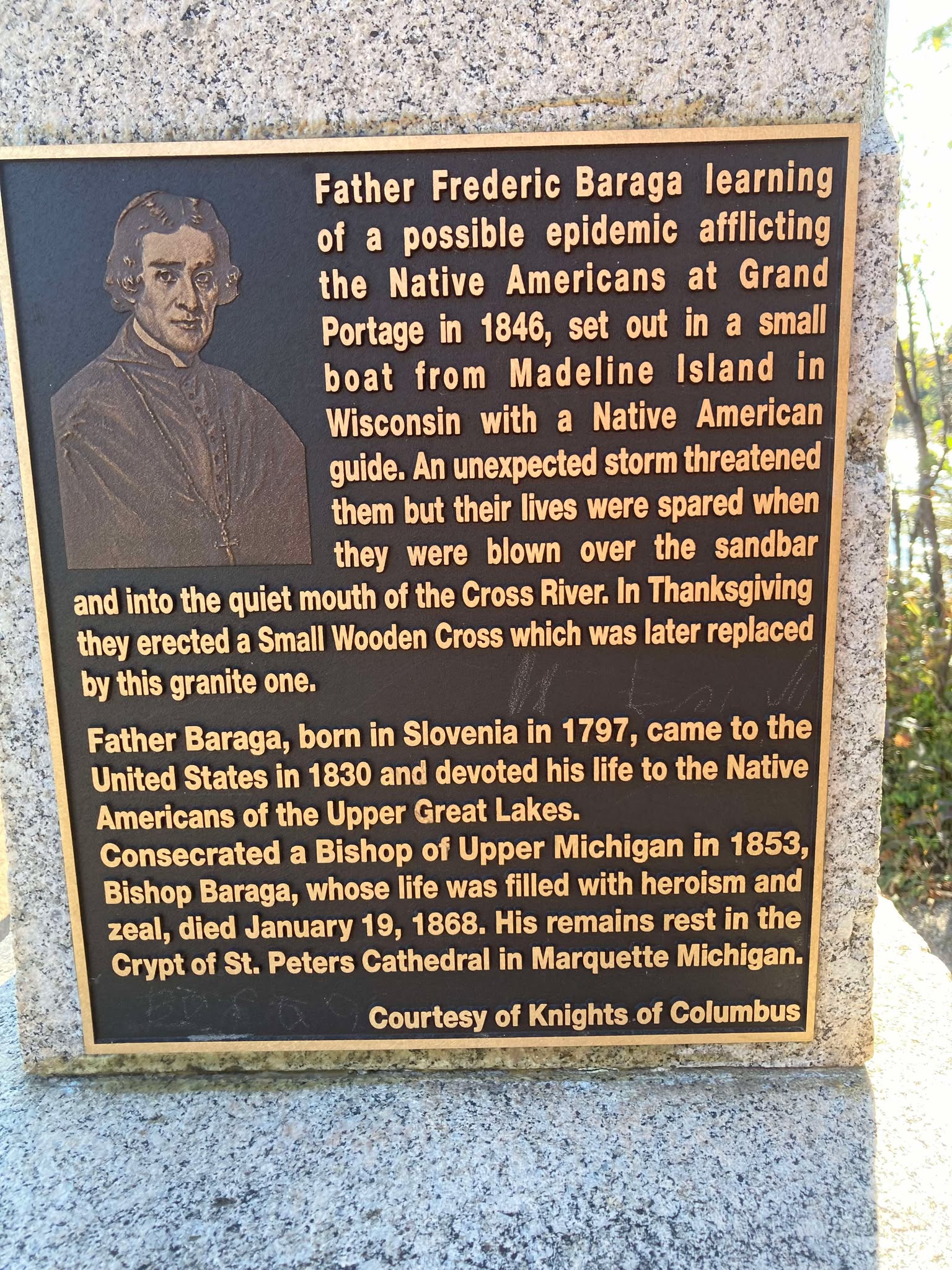

Cross River Historical Marker

Photo by Brian Finstad, 2024.

The following morning, Bishop Baraga told his guide that they would stay there that day, that they would construct and erect a cross in token of thanksgiving to God for his help and guidance to safety. So, all that day they worked. They cut down some large cedar trees and erected a large cedar cross, which they set up on the shore at the mouth of the stream. The next morning Bishop Baraga and his guide went down to the site of the cross they had erected, and again offered thanks to God for their safe deliverance. The missionary told his guide: “Hereafter this stream shall be known as “Cross River”. It has been thus known from that time on.

About twenty or twenty-five years ago, a large number of people from Duluth, Superior, and other towns and cities in the Lake Superior region, regardless of creed, made a trip to Cross River and erected a substantial cross there in place of the old cedar cross set up by Bishop Baraga and his guide, Louis Gordon, in thanksgiving to God for the wonderful guidance and loving care of his servants who landed safely at the mouth of this stream after such a perilous voyage.

Louison Gordon, Sr. moved from La Pointe to Red Cliff later in life.

Bishop Baraga stopped at Superior on their way back from the North Shore. They did not venture another lake-crossing. This zealous Lake Superior Chippewa Indian Missionary died at Marquette, Michigan, on January 19, 1868.

Cross River Historical Marker

Photo by Brian Finstad, 2024.