Steamboats, Celebrities, Soo Shipping, and Superior Speculation: Joseph R. Williams’ Account of the 1855 Payment

July 30, 2014

By Leo

“They fade, they perish, as the grass of the prairies withers before the devouring element. The officers of our government, in their conference, have been accustomed to talk about the protection their Great Father vouchsafes to them, but it is the protection which the vulture affords the sparrow. Whatever may be the intentions of our professedly paternal government, no alternative seems to remain to the Indian, but submission to its crushing and onward march.”

-Joseph R. Williams, 1855

When Joseph R. Williams stepped out from the steamboat Planet onto the dock at La Pointe in August of 1855 he tried to make sense out of the scene before him. The arrival of the Toledo-based newspaper editor and hundreds of his fellow passengers, including dignitaries, celebrities, and politicians at Madeline Island coincided with the arrival of thousands of members of the Lake Superior Ojibwe bands for the first annuity payment under the Treaty of 1854.

The portrayal of the Chequamegon region in history would never be the same.

Prior to that year, the main story depicted in the written record is the expansion of the indigenous Ojibwe and Ojibwe-French mix-blood populations, their interactions with the nations of France, Britain, and the Dakota Sioux, and ultimately their attempt to defend their lands and sovereignty against an ever-encroaching United States.

After 1855, the Ojibwe and even the first-wave white settlers appear in the written history only as curious relics of a bygone age. They are an afterthought to the story of “progress”: shipping, real estate, mining, logging, and tourism. This second version of history, what I often call “Shipwrecks and Lighthouses” still dominates today. Much of it has been written by outsiders and newcomers, and it is a more sanitary history. It’s heavy on human triumph and light on controversy, but ultimately it conceals the earlier more-interesting history and its legacy.

If we could pick one event to mark this shift, what would it be? Was it the death of Chief Buffalo that summer of 1855? Was it the creation of the reservations? Was it the new Indian policies in Washington? While those events are related, and each is significant in its own right, none explains why the ideology of Manifest Destiny (as expressed by men like Williams) so swiftly and thoroughly took over the written record.

No, if there is one event that gets credit (or I would argue blame) for changing the tone of history in the summer of 1855, it was that the first vessels passed through the new canal at Sault Ste. Marie.

The Soo Locks and Superior

The St. Mary’s Falls Canal, or the Soo Locks as we commonly call them today, had been a dream of Great Lakes industrialists and the State of Michigan for years. In their view, Lake Superior was essentially cut off from the rest of the United States because all its water passes through Sault Ste. Marie, dropping over twenty feet as it drains into Lake Huron.

These falls, or more accurately rapids, were of immense economic, symbolic, and strategic value to the Ojibwe people. The French, British, and American governments also recognized their significance as a gateway to Lake Superior and beyond. However, for the merchants of Detroit, Cleveland, and Buffalo, drawn to Lake Superior by the copper mines of the Upper Peninsula or the rich iron deposits on the North Shore (opened up by the Treaty of 1854), the falls were only an obstacle to be overcome. Traders and speculators in the western part of Lake Superior also stood to gain from increased shipping traffic and eagerly watched the progress on the canal. We can see this in the amount of space Joseph Austrian, brother of La Pointe merchant Julius Austrian, gave the canal in his memoirs.

For the young city of Superior, the opening of the canal was seen as one of the critical steps toward becoming the next St. Louis or Chicago. In 1855, Duluth did not exist. Squatters had made claims on the Minnesota side under the Preemption Act, but the real action was on the Wisconsin side where a faction of Americans led by Col. D. A. Robinson was locked in a full-on real estate speculation battle with Sen. Henry M. Rice of Minnesota. Rice, had many La Pointe traders including Vincent Roy Jr. wrapped up in his scheme, but without the lifeline of the canal, neither faction would have the settlers, goods, or commerce necessary to grow the city beyond its few hundred residents.

Steamer North Star: From American Steam Vessels, page 40 by Samuel Ward Stanton (Wikimedia Images)

The Steamers

When the first steamboats embarked on the lower Great Lakes in the 1810s, few large sailing vessels had ever appeared on Lake Superior. Birchbark canoes and Mackinac boats provided virtually all the shipping traffic. Brought by the copper rush in the Upper Peninsula, a few steamers appeared on Lake Superior in the late 1840s and early 1850s but these were modified from earlier sailing ships or painfully brought overland around the Sault. Once on Lake Superior, these vessels were confined and could no longer go back and forth to Mackinaw, Detroit, or beyond. These steamers did carry passengers, but primarily their job was to go back and forth from the copper mines to the Sault.

The opening of the canal on June 22, 1855, however, brought a new type of steamer all the way to the western end of Lake Superior. The North Star, Illinois, and Planet were massive, brightly-painted, beauties with grand dining halls with live music. They could luxuriously carry hundreds of passengers from Cleveland to Superior and back in a little over a week, a trip that had previously taken three weeks.

Decrease travel time also meant that news could travel back and forth much more quickly. Chequamegon Bay residents could get newspaper articles about unfolding war in the Crimea and the bloody fallout from the Kansas-Nebraska Act. And on June 12, 1855 the first issue of the weekly Superior Chronicle appeared off the presses of John C. Wise and Washington Ashton of Superior. The paper printed literature, world news, local events and advertisements, but large portions of its pages were devoted to economic opportunities and descriptions of the Superior area. Conspicuously absent from its pages is much mention at all of the politics of the local Ojibwe bands or any indication whatsoever that Ojibwe and mix-blooded families made up the largest percentage of the area’s population. In this way, the Chronicle, being backed by Henry Rice, was as much about promoting Superior to the outside world as it was about bringing news in.

Advertisements began to appear in the eastern papers…

New-York daily tribune. August 04, 1855 (Image provided by Library of Congress, Washington, DC Persistent link: http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030213/1855-08-04/ed-1/seq-3/)

…and the press took notice:

THE NEW YORK MIRROR says: “The fashionable watering places are not nearly as full as they were a year ago at this season; one reason for the falling off is, that thousands who have hitherto summered at these resorts have gone to Europe; and another is that the hard times of last autumn and winter have left their pinching reminiscences in many men’s purses.” The editor of the Sandusky Register seems to think that if these “fashionables” would cease to frequent Saratoga, Newport and Niagra, where $100 goes just far enough to make a waiter smile, there would be no cause for complaints of “too poor to spend the season North.”–When the snobs and devotees at the shrine of show and fashion learn that there are such places as Lake Superior, as the Islands in Lake Erie, as St. Catherines in Canada, where to live costs no more than a residence at home, we might suppose no further cause for complaint of poverty would exist. But the fact is, “go where the crowd goes or go not at all” is the motto with the fashionables; and until the places above named become popular resorts they will receive the attention only of those whose good sense leads them to prefer pure air, quiet, the pleasures of boating, bathing, fishing, &c., to the follies of Saratoga or Newport. To those who would enjoy a healthful and truly agreeable resort we can but commend the islands in Lake Erie, with a trip to the Upper Lake of Superior.

Bedford [IN] White River Standard, July 26, 1855

North Star: from American Steam Vessels by Samuel Ward Stanton, 1895 (Google Books).

By the time the August payment rolled around, steamers carrying hundreds of passengers from the highest rungs of American society. Chequamegon Bay had become a tourist destination.

The Tourists

Prof. J. G. Kohl (Wikimedia Images)

Johann Georg Kohl is a familiar name to readers of the Chequamegon History website. Kohl’s Kitchi Gami, originally published in his native Germany, is a standard of Ojibwe cultural history and anthropology. His astute observations and willingness to actually ask questions about unfamiliar cultural practices of the people practicing them, created a work that has stood the test of time much better than those of his contemporaries. The modern reader will find Kohl’s depiction of Ojibwe people as actual intelligent human beings stands in refreshing contrast to most 19th-century works. Kohl also wrote some untranslated articles for German newspapers mentioning his time at La Pointe. One of these, on the subject of the death and conversion of Chief Buffalo, partially appeared on this site back in April.

Johann Kohl was atypical of the steamboat tourists, but he was a steamboat tourist nonetheless:

Prof. Kohl, professor in Dresden University has been rusticating for a few weeks past, in the Lake Superior Country, collecting matter for a forthcoming work, which he intends publishing after his return to Germany. He expressed himself highly pleased with his visit, and remarked that the more familiar he became with the American people and the resources of our country, the better satisfied he was that America had fallen into the hands of those who were perfectly competent to develop her riches and improve the natural sources of wealth and prosperity, which nature has given her.

Grace Greenwood has also been paying her respects to the Lake Superior region, and came down on the North Star with Prof. Kohl.

[Milwaukee] Daily Free Democrat, September 15, 1855

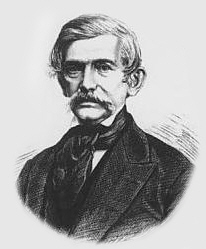

Sara Jane Lippincott, a.k.a. Grace Greenwood (Wikimedia Images).

“Grace Greenwood” was the pseudonym of Sara Jane Lippincott, and a household name in 1855. Though more forgotten to history than some of the other names in this post, the New York native was probably the biggest celebrity to visit La Pointe in the summer of 1855. As an acclaimed poet, she had risen to the highest rungs of American literary society and was a strong advocate of abolitionism and women’s rights. However, she was probably best known as the editor of The Little Pilgrim, a popular children’s magazine. She is mentioned in several accounts of the 1855 payment, but none mention an important detail, considered improper for the time, detail. Sara was very pregnant. Annie Grace Lippincott was born less than two months after her mother left Lake Superior on the North Star.

Although much of her work is digitized and online for the public, the only mention of the trip I’ve found from her pen is this blurb from the front page of the September 1855 edition of The Little Pilgrim:

Our little readers will please forgive whatever delay there may be in the coming of our paper this month, for we are among the wild Indians away up in Lake Superior on the island of La Pointe; and the mails from this far region are so slow and irregular that our articles may not reach Philadelphia till two or three weeks after they should do so (The Little Pilgrim: Google Books).

Dr. Richard F. Morse was one of the chroniclers of the 1855 payment who made sure to mention Lippincott. Morse’s essay, The Chippewas of Lake Superior, published in the third volume of the Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin (1857), is entirely about the payment. It is also the clearest example of the abrupt shift in narrative discussed above. It is full of the suffocating racism of benevolent paternalism. Morse arrogantly portrays himself as an advocate for the Lake Superior bands, but his analysis shows how little he knows of the Ojibwe and their political situation in 1855. Unlike Kohl, he doesn’t seem to care enough to ask and learn.

In fairness, Morse’s account is a valuable document, excerpted in several posts on this website (see People Index). It is also the document that years ago inspired the first steps toward this research by planting the question, “Where did all these fancy people at the 1855 annuity come from?” Chippewas of Lake Superior is too long and too well-known to bother reproducing on this site, but it can be read in it’s entirety on Google Books.

Crockett McElroy (Cyclopedia of Michigan [1890])

After the Civil War, McElroy would go on to find wealth in the Great Lakes shipping industry and be elected as a Republican to several offices in the State of Michigan. In the summer of 1855, however, he was only nineteen years old and looking for work. Crockett’s father, Francis McElroy appears in several later 19th-century censuses as a resident of Bayfield. Apparently, Francis (along with Crockett’s younger brothers) split time between Bayfield and Michigan. Young Crockett did not stay in Bayfield, but his biography in the Cyclopedia of Michigan (1890) suggest his account can be considered that of a semi-local laborer in contrast to the fancier visitors he would have shared a steamboat with:

Crocket McElroy, the subject of this sketch, received his early education at Gait, Ontario; and, when twelve years of age, removed to Detroit. Here he attended one of. the public schools of that city for a short time, and, afterwards, a commercial academy. When thirteen years of age, he began to act as clerk in a wholesale and retail grocery store, remaining three years; he then, for two years, sold small beer. In 1853 he went to Ira, St. Clair County, as clerk, to take charge of a general store; and for the next five years served as clerk and taught school, spending the summer months of 1854-55 in the Lake Superior region (pg. 310).

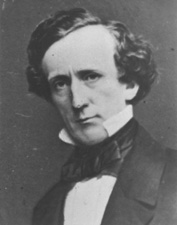

Lewis Cass (Wikimedia Images)

Another Michigan-based politician, considerably more famous than McElroy, Lewis Cass’ excursion to Lake Superior in 1855 was portrayed as a homecoming of sorts. The 72 year-old Michigan senator had by then occupied several high-level cabinet and congressional positions, and was the Democratic nominee for president in 1848, but those came after he had already entered the American popular imagination. Thirty-five years earlier, as a little known governor of the Michigan Territory (which included Wisconsin and the arrowhead of Minnesota) he led an American expedition to Red Cedar (Cass) Lake near the headwaters of the Mississippi. Thirty-seven years after the Treaty of Paris, and seven years after the death of Tecumseh, it was the first real attempt by the United States to assert dominion over the Lake Superior country. In some ways, 1855 marked the end of that colonization process and brought the Cass Expedition full-circle, the significance of which was not lost on the editors of the Superior Chronicle:

The Predictions of Gen. Cass.: At the opening of the Wabash and Erie Canal, which unites the waters of Lake Erie with those of the Mississippi, the celebration of which took place at Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1844, Gen. Cass in his address subsequently predicted the union of Lake Michigan from Chicago to the Mississippi; this prediction was fulfilled in 1850. At the same time he said that there were then present those who would witness the settlement of the region at the southwest extremity of Lake Superior, and lay the foundation for a similar union of the waters of that lake with the Mississippi.

On the last trip of the steamer Illinois to this place, Gen. Cass was among the passengers, and witnessed the fulfillment of his prediction in respect to the settlement of this region. May he live to be present at the opening of the channel which will connect this end of the lake with the Mississippi, and witness the consummation of all his prophesies.

Superior Chronicle, August 21, 1855

Charles Sumner in 1855 (Wikimedia Images)

A political opponent of western Democrats like Cass, Charles Sumner has gone down in history as the only man to be nearly beaten to death on the floor of the United States senate. Less than a year before Rep. Preston Brooks of South Carolina would attack him with a cane, sending the country hurtling ever-faster toward civil war, the Massachusetts senator visited La Pointe to watch the annuity payment. By 1855, Sumner already had a reputation as a staunch abolitionist, and he even wrote a letter to the Anti-Slavery Reporter while on board the North Star. Aside from a handful of like-minded native New Englanders like Edmund Ely and Leonard Wheeler, Sumner was not in a part of the country where most voters shared his views (the full-blood and most mix-blood Ojibwe were not considered citizens and therefore ineligible to vote). The Lake Superior country was overwhelmingly Democratic, and the Superior Chronicle praised the “popular sovereignty” views of Stephen Douglas in the midst of the violence following the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Sumner, whose caning resulted from his fierce criticism of popular sovereignty, was among those “radical Bostonians” the Chronicle warned its readers about. However, the newspaper was kind and uncritical when the senator appeared in its city:

Senator Sumner at Superior and La Pointe.: In our last number we neglected to announce the visit of Hon. Charles Sumner, Bishop McClosky, and other distinguished persons to Superior. They came by the North Star, and staying but a few hours, had merely time to hastily view our thriving town. They expressed gratfication at its admirable location and rapidity of its growth.

At La Pointe, the heat stopped to allow the passengers an opportunity to see that pretty village and the large number of Indians and others congregating there to the last great payment at this station of the Lake Superior Chippewas. Here Mr. Sumner was the guest of the reverend Catholic missionary, whose successful endeavors to gratify the numerous visitors at La Pointe we have frequently heard commended.

Superior Chronicle, August 14, 1855

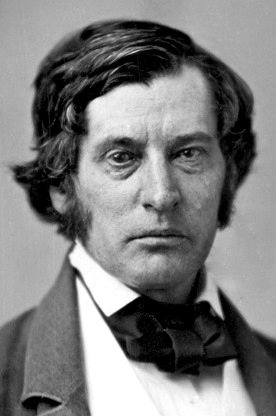

Jesse D. Bright (Wikimedia Images)

Staying a little longer at Superior, another U.S. senator, Jesse Bright the President pro tempore Indiana, also appeared on Lake Superior in the summer of 1855. For Bright, however, this was more than a pleasure excursion. He had a chance to make real money in the real estate boom of the 1850s. Superior, at the head of the lake with ship traffic through the Soo, and military road and potential railroad connection to St. Paul, looked poised to be the next great gateway to the west. He invested and apparently lost big when the Great Lakes real-estate boom busted in the Panic of 1857.

Bright would go on to be a Southern sympathizer and a “Copperhead” during the Civil War and was the only northerner to be expelled from the Senate for supporting the Confederacy. In 1855, he was already a controversial figure in the partisan (Democrat, Whig, Know-Nothing) newspapers:

The Buffalo Commercial, upon the authority of the Cincinnati Gazette, states “that Mr. Bright, of Indiana, President of the Senate, pro tem lately made a Sunday speech, an hour and a half long to the people of a town on Lake Superior, and the passengers of the steamer in which he was travelling. He discoursed most eloquently on the virtues and glories of modern Democracy, whose greatest exemplar, he said, was the administration of Franklin Pierce.” The Know Nothing press, of which the Commercial and the Gazette are leading journals, must be rather hard up for material, when recourse to such misrepresentation as the above becomes necessary…

…The speaker did not allude to politics, and did not speak over ten minutes.

And out of this mole hill the Commercial manufactures a mountain of speculation, headed “Jesse D. Bright–The Presidency.” –Sandusky Mirror.

Fort Wayne [IN] Sentinel, September 5, 1855

Promoters & Proprietors of Old Superior: (Clockwise from upper left) U.S. Senator W[illiam]. A. Richardson, Sen. R[obert] M. T. Hunter, Sen. Jesse Bright, Sen. John C. Breckinridge, Benjamin Brunson, Col. John W. Fourney, Henry M. Rice (Flower, Frank A. Report of the City Statistician [1890] Digitized by Google Books)

John C. Breckinridge (Wikimedia Images)

It may also be uncomfortable for the modern northern reader to see how cozy the politicians of our area were with unabashedly pro-slavery Democrats and future Confederates. The biggest name among these Lake Superior investors and 1855 visitors would be John C. Breckinridge. Breckinridge, coming off a stint as U.S. Representative from Kentucky, would go on to be Vice President of the United States under James Buchanan, and Secretary of War for the Confederacy. However, he is most famous for finishing second to Abraham Lincoln in the pivotal presidential election of 1860. Chequamegon Bay residents will probably find another investment of the future vice-president more interesting even than the Superior scheme:

A PLEASANT SUMMER RESIDENCE–The senior editor of the Chicago Press writes from Lake Superior:

Basswood Island, one of the group of Apostle Island has been entered by Mr. Breckinridge of Kentucky, who, I am told, contemplates the erection of a summer residence upon it. We landed at this Island for wood. There is deep water up to its base, and our steamer lay close alongside the rocky shore as though it had been a pier erected for the purpose. There is deep water, I am told, in the channels between most of the Islands of the group furnished an excellent shelter for vessels in tempestuous weather.

[Milwaukee] Weekly Wisconsin, August 15, 1855

Hon J. C. Breckenridge, of Kentucky, has purchased Basswood Island, one of the group of Apostle Islands, in Lake Superior, and intends erecting a summer residence thereon.

Boston Post, August 23, 1855

Captain John Wilson (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated)

The Whig/Free Soil press’ condemnation of Senator Bright for allegedly forgetting the Sabbath and to keep it holy may remind the Chequamegon History reader of the A.B.C.F.M missionaries’ obsession with that particular commandment in their efforts among the Ojibwe people. However, it seems to be one of those features of 19th-Century America that was fussed about more than it was actually observed.

A good example of this comes from Captain John Wilson, who led the steamer Illinois to La Pointe in the summer of 1855. He seems to have been one of those larger-than-life characters, and he is often mentioned in newspaper accounts from the various Great Lakes ships he commanded. Wilson died off the shore of Milwaukee in the sinking of the Lady Elgin, in 1860 along with over 300 passengers. “The Titanic of the Great Lakes,” as the disaster came to be known, is still the greatest loss of life in the history of the lakes (this article gives a good overview). Other than the North Star, the Lady Elgin, which began its runs to the “Upper Lake” in 1855, was probably the most famous steamer on Lake Superior before its sinking. Captain Wilson was afterwards praised for his character heroism during the ordeal, which was blamed on the captain of the schooner that collided with the Elgin.

Captain Wilson’s charisma shines through in the following 1855 Lake Superior account, but I’ll let the reader be the judge of his character:

A MAN FOR ALL OCCASIONS–TWO AMUSEMENTS–Capt Wilson, of the steamer Illinois, on the Upper Lakes is proverbially a man for all occasions and is equally at home in a horse-race or a dance. During a recent excursion of his beautiful boat to Lake Superior, he happened to arrive at a place on Sunday, where several tribes of Indians were soon to receive their annuity from the General Government and where a large number were already present. As soon as the breakfast table was cleared Capt. W. commenced arrangements for religious services in the ladies’ cabin, agreeably to the request of a preacher on board. Chairs and sofa were placed across the hall and the piano, with a large bible on it, represented a pulpit. The large bell of the boat was tolled, and in a short time quite a respectable congregation occupied the seats. As soon as service had fairly begun, the Captain came upon the forward deck where a number of gentlemen were enjoying their pipes and meerschaum, and thus addressed them.

Gentlemen–I come to let you know that meetin‘ is now going on in the aft cabin, where all of you in need of prayers and who wish to hear a good sermon had better retire. I would also state that in accordance with the desire of several passengers , I intend to get up an Indian foot race on shore for a barrel of flour.–You can make your own selection of the two amusements.”

The foot race did come off, and it was fortunate that all the lady passengers were at “meetin,” as one of the Indians who started with nothing on him but a calico shirt came in minus that! He won the flour, however. Good for you! —Spirit of the Times

[Milwaukee] Weekly Wisconsin, October 3, 1855

Joseph R. Williams (Wikimedia Images)

Finally, we get back to Joseph R. Williams. The reason so many stories like Captain Wilson’s made it into the papers that summer was that each of the steamboats seemed to be carrying one or more Midwestern newspaper editors. Williams, the editor of the Toledo Blade, arrived on the Planet in time to witness the La Pointe payment.

Williams would go on to become the first president of what would become Michigan State University and serve in multiple positions in the state government in Michigan. His letters and notes from Lake Superior turned into multiple articles that made their way back up to the Superior Chronicle. In a later post, I may transcribe his record of C. C. Trowbridge’s account of the 1820 Cass Expedition or his description of Superior, but in the name of brevity, I’ll limit this post to his a article on the payment itself:

From La Pointe–Indian Payment, etc.

The following interesting incidents of the recent meeting of Chippeways at La Pointe are taken from the letters of Mr. Williams, editor of the Toledo Blade. Mr. W. was among those who visited Lake Superior on the last excursion of the steamer Planet. In another portion of this week’s paper will be made an account of General Cass’ expedition to the Northwest, from the pen of the same gentleman. We commend it and the following extracts, to the perusal of our readers.

This is one of the old American Fur Company’s stations, a village such as formerly existed at Detroit and Mackinac. Indian huts with bark roofs, the long low warehouse, the half dressed and painted Indians, here and there a Frenchman speaking his mother tongue, his whole air indicating his lineage plainly that he was the descendant of an old voyager, revive the reflection of those days so graphically described by Washington Irving in his Astoria. La Pointe is upon an island, and the harbor gracefully curves around us from the north.

Here we find Colonel Manypenny, Commissioner of Indian Affairs; H. C. Gilbert, Indian Agent for Michigan; Hon. D. A. Noble and Hon. H. L. Stevens, late members of Congress, and other gentlemen, who are awaiting the Indian payment to take place the beginning of next month. Grace Greenwood, who came up on the Illinois a few days since is also excursioning here. The store houses are full of the goods provided for the payment, piles of [?] and provisions, [?], plows, spades, [?] carts, mattresses, bedsteads, blankets, clothing, and [?] a well [?] supply of such articles as are calculated to promote the comfort and civilization of the ill-fated remnant of the former lords of these [many] isles scattered around us, and [the] “forests primeval,” on either shore of this vast inland sea.

Colonel Manypenny deserves great credit for the [ind?bility] with which he has endeavoured to carry into wholesale effect the [?] method adopted of paying the Indians their annuities. Formerly, the unfortunate [race] were paid in specie, and close on the tract of the dispenser of the payment came a swarm of cormorant and heartless Indians traders, who, for whisky and trinkets, and inferior arms and implements, including perhaps blankets and some useful articles of dress, obtained the dollars as soon as they were paid. The Indian dances followed by wild drunken orgies, were a perpetual accompaniment. The Indian, besotted by liquor, parted with almost everything of value, and returned to his home and his hunting grounds, poor and in worse condition than he came. Many years since I attended a payment at Grand Rapids, Michigan, and it was a mournful spectacle. One hardly knew whether to pity the weakness of the victims or abhor the heartlessness of the destroyers most. As late as 1833 the last Indian payment was made on the Maumee in the immediate vicinity of Toledo, on the point below Manhattan. One Lloyd was Indian Agent in 1830. It is said that he purloined from each of the thousand dollar boxes paid the Indians one or two hundred dollars, and that during the night whites went around among the wigwams and cut off the portion of the dresses of the Indians in which the specie was tied up. But the picture before us is relieved of features so disgraceful and disgusting. We saw no drunken Indian on shore. Indeed several of the Caucasian lords of these fading tribes, whom we had on board, might have taken a useful lesson in sobriety from the red men. The traders however are here. They mutter curses upon Colonel Manypenny, because he does not wink at their robberies. It is supposed abundance of whisky is concealed on the island, which will be unwrapped and sold, to besot the Indians, as soon at the valuables are distributed among them.

***

On his arrival here, the Indians proposed a dance. As dances end in Bacchanalian revels, the colonel has set his face against them. Enlivened and excited, however, by our band of music, the Indians could resist no longer. A dozen or more emerged from their cabins, bearing before them their war flag, which was a staff with a fringe of long feathers extending its length, and with bells attached to it, and engaged in a war dance. Their bodies were nearly naked and painted. The dance was a pantomimic description of war scenes. The leading brave struck the flagstaff to stop the dance, and made a speech describing how he had, less than thirty days ago, killed and scalped a Sioux, and he held up in his clenched fist, in triumph before us, the almost yet reeking scalp of his victim. His speech was accompanied by vigorous and appropriate [motion]. It was the imprompt and natural movement of body, [hands], and features from this brief specimen, it was easy enough to imagine that the Indian is often eloquent. This small band of dancers were splendid physical specimens of men, and the dance was real exultation over a late actual achievement. The Chippeways–and they are all Chippeways in these regions–maintain a traditional hostility to the Sioux, and are rarely at peace. It was only a few months since a band of Chippeways pioneered down into the village of St. Paul, and killed a Sioux woman trading in a store. Before the witnesses had recovered from the terror excited, the band had fled as rapidly as they appeared. The Sioux remain on the lands beyond, and the Chippeways this side of the Mississippi.

After the war dance was finished, they danced a beggar’s dance, the purport of which was that they wanted three beeves of Colonel Manypenny. At its close, the brave presented a pipe to Captain Ward, who smoked it in a token of amity. He then forced through the surrounding crowd, and sought Colonel M., who stood at a distance. The Colonel rejected the proffered pipe. His acceptance would have been a sanction of the dances he disapproved, and a concession of the three beeves. The Chief returned to the ring, and made a brief vehement speech, evidently a concentration of indignant scorn. Mrs. A., of Monroe, Michigan, an educated lady of Indian blood, informed me that it was full of defiance, bitterness and mortification.

******

In speaking of the Indians assembled at the payment in my last, I said they were a motley crew, and indeed they are. The braves, engaged in the dances described, were fine specimens of manhood. Their erect forms, developed chests, and symmetry, and general health, as developed in every muscle and feature, illustrate the perfection to which physical man is brought in savage life. But in sad contrast, we see around us pitiable specimens of humanity, crouching, lazy, filthy, besotted beings, who possess all the vices of both the white and the red races, and none of the virtues of either.

Canoes are marshalled along the beach, which have wafted here the tenants of both shores of Superior. Indians have dotted their clusters of wigwams over the vicinity, and seem to have brought along all their aged and infirm as well as infants.

I think one Indian woman here is the oldest human being I ever saw. The deep furrows, the folds of skin which have lost almost the appearance of vitality, so withered and dead as to resemble gutta percha, eye sight lost, hearing gone, no sense left except touch, which was indicated by the avidity with which she seized small pieces of money thrown into her lap, all these proofs convinced me that she was older by ten or fifteen years than any person I ever saw. A son and daughter were near her, apparently kind and affectionate, and proud to protect her, who themselves, were verging upon old age, an illustrative example of these [?ate] savages, to unnatural whites of whom melancholy tales of ingratitude are told. Even her children could not tell her age. All they could say was that she was “the oldest Indian.” Old Buffalo, the Chief, who was ninety years old, looked like a young man compared with her.

Nothing more surprised our party than the great proportion of their children, of all sizes, and I may add, shades of color, for the infusion of French blood from a long series of successive intermarriages, is found in every tribe. Infants fastened on boards, with the children and youth under sixteen, outnumber the adults. The children are all plump, all have rounded and full muscles, all good chests, thus showing that their life, vicious as it is, is more favorable to health and development, in consequence of their freedom of motion, perpetual exercise in the open air. Their gregariousness, flocking together where impulse carried them, as self reliant as their parents who seemed to allow them perfect freedom, even though strangers were so numerous among them, bore a pleasing, and to us instructive contrast to the entire and melancholy helplessness to which white children, especially in cities, are doomed.

Many of the Indians wore a feather or feathers in their cap, indicating the number of Sioux they had scalped. One displayed six feathers. He told us that he had in battle killed two, and taken the scalps of four others, killed by unknown hands of his band. The last victim he had slain but a month ago. One erect youth, of not more than eighteen, with a fresh and handsome face, bore proudly a single feather as a token of his early prowess. One man, in answer to the question, whether he had ever taken a scalp, replied gravely, without a smile, that he had not, and was of no more account that a woman in his tribe. An illustration of their generosity and savage ferocity is afforded by a sub-Chief who had an interview with Mr. Gilbert, the Indian Agent, a few days since. He presented Mr. G. an elegant cloak, made entirely of beaver skins, in expectation of nothing but a large medal in return. He was intent in speech, and animated and pleasant in address. No trace of savage ferocity lingered in his face. Yet it was stated that this man had actually killed and eaten his own child.

Sometimes their earnings if economically used would afford them a comfortable subsistence. The whites, even in their ordinary trade have practiced habitually heartless extortion. When Gov. Cass’s expedition visited this country in 1820, the Indians were in the habit of paying the traders a beaver skin, worth sixteen dollars, for a gill of powder; the same for a shirt; the same for thirty balls; and three beaver skins for a single blanket. I inquired of the Chief, Old Buffalo, what was the highest price he had ever paid for tobacco. He replied that they formerly made purchases of the Hudson Bay Company, tobacco was coiled up in ropes of about three quarters of an inch in diameter, and that he had paid ten beaver skins for a fathom, or at least ten dollars for a foot in length. But when the poor creatures became maniacs or idiots from drink, no possession was so prized that they would not part with it for a single cup of fire water. That the trader availed himself of the imbecility he created, is acknowledged. A large share of the boundless wealth of Mr. Astor was based on acquisitions, through his instruments and agents of this questionable and indeed diabolical character. Well might Burns exclaim in sorrow,

“Man’s inhumanity to man.

Makes countless thousands mourn.”

for whether among men and families of the same blood, or between civilized and savage men, either in peace or in the antagonism of war, the whole world and all time has teemed with sickening, heart-rending examples of its melancholy truth.

By chance we have been able to witness what can not be seen, a few years hence on this side of the “Father of waters,” or indeed on the continent. Here in our magnificent floating palace and the crowd of intellectual and cultivated people on board, surrounded by the refinements of life, we have the highest triumphs of civilization, side by side and in contrast with the rudest manifestations of primitive savage life.–An interesting episode in human affairs, though prompting [a] thousand sad reflections. The doom of entire extirpation of the red man seems surely and gradually to approach. The perpetual warfare among tribes on the extreme frontier annually declinates their most vigorous braves, and consequently it is manifest that among this tribe at least there were far more women than men between the ages of twenty and forty. Many perish from ignorance of the laws of nature, and many from excessive exposure and famine. Rapacity of the whites, and whiskey, finish the merciless work. They fade, they perish, as the grass of the prairies withers before the devouring element. The officers of our government, in their conference, have been accustomed to talk about the protection their Great Father vouchsafes to them, but it is the protection which the vulture affords the sparrow. Whatever may be the intentions of our professedly paternal government, no alternative seems to remain to the Indian, but submission to its crushing and onward march.

Dr. Bethune Duffield (Detroit–biographical sketches by Walter Buell [1886] Google Books)

1855 as a Turning Point: A plea to today’s Chequamegon Bay residents

Williams’ quote about the vulture and the sparrow, excerpted at the very top of this post, is about as succinct a statement about Manifest Destiny as I have ever read. If it weren’t surrounded by so many grossly-ignorant and disgusting statements about Ojibwe people, one might almost take it as sympathy for the Ojibwe cause. Still, the statement holds the key to our understanding of the story of 1855.

In the grand scheme of our region’s history, the payment was less significant than the treaty itself or the tragic removal politics of the early 1850s. Sure, it was the first payment under the final treaty and it featured the visit of Indian Affairs Commissioner George Manypenny to La Pointe, but ultimately it was largely like the rest of the 30-plus annuity payments that took place in our area in the middle of the 19th century. The death of Chief Buffalo in September 1855, and visit of Manypenny who shifted American Indian policy from removal to assimilation, represented both real and symbolic breaks with the past, but ultimately the great shift of 1855 is only one of tone.

Ultimately, however, this shift is only superficial and the reality of life for most Chequamegon residents didn’t change overnight in 1855. The careers of men like Blackbird, Vincent Roy Jr., Julius Austrian, Naaganab, and others show the artificiality of such a line. To them, the tourists on the Planet and North Star were probably just a distraction or curiosity.

Williams was wrong. The Ojibwe did not perish before the “devouring element,” and neither did that earlier history. Somehow, though, since then those of us who live in this area have allowed outsiders to write the story. Maybe it’s comfortable for those, like myself, of European ancestry to focus on shipwrecks and lighthouses rather than colonialism and dispossession, but in doing so we deny ourselves the most significant events of our area’s history and an understanding of its legacy on today.

By all means, learn the names of Grace Greenwood, John Breckinridge, and the Lady Elgin, but understand the fleeting impact of those names on our area’s history. Then, read up on Blackbird, Jechiikwii’o, Leonard Wheeler, Benjamin Armstrong and other players in 1855 politics who really did leave a lasting legacy.

Off my soapbox for now…

The bulk of this article comes from newspaper articles found on two digital archives. Access Newspaper Archive is available to Wisconsin library card holders through badgerlink.net. The Library of Congress Chronicling America site is free at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/. Other sources are linked within the post.

![Group of people, including a number of Ojibwe at Minnesota Point, Duluth, Minnesota [featuring William Howenstein] ~ University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/howenstein-minnesota-point.jpg?w=300&h=259)