1827 Deed for Old La Pointe

December 27, 2022

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Chief Buffalo and other principal men for the La Pointe Bands of Lake Superior Chippewa began signing treaties with the United States at the 1825 Treaty of Prairie Du Chien; followed by the 1826 Treaty of Fond Du Lac, which reserved Tribal Trust Lands for Chippewa Mixed Bloods along the St. Mary’s River between Lake Superior and Lake Huron:

ARTICLE 4.

The Indian Trade & Intercourse Act of 1790 was the United States of America’s first law regulating tribal land interests:

SEC. 4. And be it enacted and declared, That no sale of lands made by any Indians, or any nation or tribe of Indians the United States, shall be valid to any person or persons, or to any state, whether having the right of pre-emption to such lands or not, unless the same shall be made and duly executed at some public treaty, held under the authority of the United States.

It being deemed important that the half-breeds, scattered through this extensive country, should be stimulated to exertion and improvement by the possession of permanent property and fixed residences, the Chippewa tribe, in consideration of the affection they bear to these persons, and of the interest which they feel in their welfare, grant to each of the persons described in the schedule hereunto annexed, being half-breeds and Chippewas by descent, and it being understood that the schedule includes all of this description who are attached to the Government of the United States, six hundred and forty acres of land, to be located, under the direction of the President of the United States, upon the islands and shore of the St. Mary’s river, wherever good land enough for this purpose can be found; and as soon as such locations are made, the jurisdiction and soil thereof are hereby ceded. It is the intention of the parties, that, where circumstances will permit, the grants be surveyed in the ancient French manner, bounding not less than six arpens, nor more than ten, upon the river, and running back for quantity; and that where this cannot be done, such grants be surveyed in any manner the President may direct. The locations for Oshauguscodaywayqua and her descendents shall be adjoining the lower part of the military reservation, and upon the head of Sugar Island. The persons to whom grants are made shall not have the privilege of conveying the same, without the permission of the President.

The aforementioned Schedule annexed to the 1826 Treaty of Fond du Lac included (among other Chippewa Mixed Blood families at La Pointe) the families of Madeline & Michel Cadotte, Sr. and their American son-in-laws, the brothers Truman A. Warren and Lyman M. Warren:

-

To Michael Cadotte, senior, son of Equawaice, one section.

-

To Equaysay way, wife of Michael Cadotte, senior, and to each of her children living within the United States, one section.

-

To each of the children of Charlotte Warren, widow of the late Truman A. Warren, one section.

-

To Ossinahjeeunoqua, wife of Michael Cadotte, Jr. and each of her children, one section.

-

To each of the children of Ugwudaushee, by the late Truman A. Warren, one section.

-

To William Warren, son of Lyman M. Warren, and Mary Cadotte, one section.

Detail of Michilimackinac County circa 1818 from Michigan as a territory 1805-1837 by C.A. Burkhart, 1926.

~ UW-Milwaukee Libraries

Now, if it seems odd for a Treaty in Minnesota (Fond du Lac) to give families in Wisconsin (La Pointe) lots of land in Michigan (Sault Ste Marie), just remember that these places were relatively ‘close’ to each other in the sociopolitical fabric of Michigan Territory back in 1827. All three places were in Michilimackinac County (seated at Michilimackinac) until 1826, when they were carved off together as part of the newly formed Chippewa County (seated at Sault Ste Marie). Lake Superior remained Unceded Territory until later decades when land cessions were negotiated in the 1836, 1837, 1842, and 1854 Treaties.

Ultimately, the United States removed the aforementioned Schedule from the 1826 Treaty before ratification in 1827.

Several months later, at Michilimackinac, Madeline & Michel Cadotte, Sr. recorded the following Deed to reserve 2,000 acres surrounding the old French Forts of La Pointe to benefit future generations of their family.

Register of Deeds

Michilimackinac County

Book A of Deeds, Pages 221-224

Michel Cadotte and

Magdalen Cadotte

to

Lyman M. Warren

~Deed.

Received for Record

July 26th 1827 at two Six O’Clock A.M.

J.P. King

Reg’r Probate

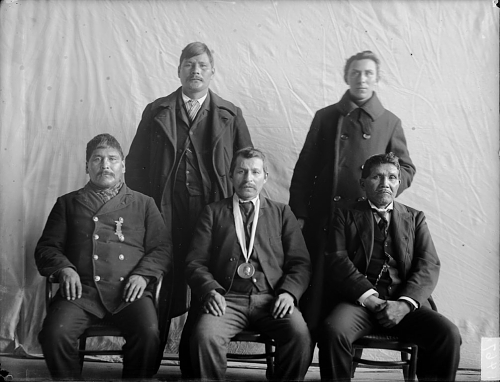

Bizhiki (Buffalo), Gimiwan (Rain), Kaubuzoway, Wyauweenind, and Bikwaakodowaanzige (Ball of Dye) signed the 1826 Treaty of Fond Du Lac as the Chief and principal men of La Pointe.

“Copy of 1834 map of La Pointe by Lyman M. Warren“ at Wisconsin Historical Society. Original map (not shown here) is in the American Fur Company papers of the New York Historical Society.

Whereas the Chief and principal men of the Chippeway Tribe of indians, residing on and in the parts adjacent to the island called Magdalen in the western part of Lake Superior, heretofore released and confirmed by Deed unto Magdalen Cadotte a Chippeway of the said tribe, and to her brothers and sisters as tenants in common, thereon, all that part of the said Island called Magdalen, lying south and west of a line commencing on the eastern shore of said Island in the outlet of Great Wing river, and running directly thence westerly to the centre of Sandy bay on the western side of said Island;

and whereas the said brothers and sisters of said Magdalen Cadotte being tenants in common of the said premises, thereafterwards, heretofore, released, conveyed and confirmed unto their sister, the said Magdalen Cadotte all their respective rights title, interest and claim in and to said premises,

and whereas the said Magdalen Cadotte is desirous of securing a portion of said premises to her five grand children viz; George Warren, Edward Warren and Nancy Warren children of her daughter Charlotte Warren, by Truman A. Warren late a trader at said island, deceased, and William Warren and Truman A. Warren children of her daughter Mary Warren by Lyman M. Warren now a trader at said Island;

and whereas the said Magdalen Cadotte is desirous to promote the establishment of a mission on said Island, by and under the direction, patronage and government of the American board of commissioners for foreign missions, according to the plan, wages, and principles and purposes of the said Board.

William Whipple Warren was one of the beneficiary grandchildren named in this Deed.

Now therefore, Know all men by these presents that we Michael Cadotte and Magdalen Cadotte, wife of the said Michael, of said Magdalen Island, in Lake Superior, for and in consideration of one dollar to us in hand paid by Lyman M. Warren, the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged, and for and in consideration of the natural love and affection we bear to our Grandchildren, the said George, Edward, Nancy, William W., and Truman A. Warren, children of our said daughters Charlotte and Mary;

and the further consideration of our great desire to promote the establishment of a mission as aforesaid, under and by the direction, government and patronage of Board aforesaid, have granted, bargained, sold, released, conveyed and confirmed, and by these presents do grant, bargain, sell, release, convey and confirm unto the said Lyman M. Warren his heirs and assigns, out of the aforerecited premises and as part and parcel thereof a certain tract of land on Magdalen Island in Lake Superior, bounded as follows,

Detail of Ojibwemowin placenames on GLIFWC’s webmap.

that is to say, beginning at the most southeasterly corner of the house built and now occupied by said Lyman M. Warren, on the south shore of said Island between this tract and the land of the grantor, thence on the east by a line drawn northerly until it shall intersect at right angles a line drawn westerly from the mouth of Great Wing River to the Centre of Sandy Bay, thence on the north by the last mentioned line westward to a Point in said line, from which a line drawn southward and at right angles therewith would fall on the site of the old fort, so called on the southerly side of said Island; thence on the west by a line drawn from said point and parallel to the eastern boundary of said tract, to the Site of the old fort, so called, thence by the course of the Shore of old Fort Bay to the portage; thence by a line drawn eastwardly to the place of beginning, containing by estimation two thousand acres, be the same more or less, with the appurtenances, hereditaments, and privileges thereto belonging.

To have and to hold the said granted premises to him the said Lyman M. Warren his heirs and assigns: In Trust, Nevertheless, and upon this express condition, that whensoever the said American Board of Commissioners for foreign missions shall establish a mission on said premises, upon the plan, usages, principles and purposes as aforesaid, the said Lyman M. Warren shall forthwith convey unto the american board of commissioners for foreign missions, not less than one quarter nor more than one half of said tract herein conveyed to him, and to be divided by a line drawn from a point in the southern shore of said Island, northerly and parallel with the east line of said tract, and until it intersects the north line thereof.

And as to the residue of the said Estate, the said Lyman M. Warren shall divided the same equally with and amongst the said five children, as tenants in common, and not as joint tenants; and the grantors hereby authorize the said Lyman M. Warren with full powers to fulfil said trust herein created, hereby ratifying and confirming the deed and deeds of said premises he may make for the purpose ~~~

In witness whereof we have hereunto set our respective hands, this twenty fifth day of july A.D. one thousand eight hundred and twenty seven, of Independence the fifty first.

(Signed) Michel Cadotte {Seal}

Magdalen Cadotte X her mark {Seal}

Signed, Sealed and delivered

in presence of us }

Daniel Dingley

Samuel Ashman

Wm. M. Ferry

(on the third page and ninth line from the top the word eastwardly was interlined and from that word the three following lines and part of the fourth to the words “to the place” were erased before the signing & witnessing of this instrument.)

~~~~~~

Territory of Michigan }

County of Michilimackinac }

Be it known that on the twenty sixth day of July A.D. 1827, personally came before me, the subscriber, one of the Justices of the Peace for the County of Michilimackinac, Michel Cadotte and Magdalen Cadotte, wife of the said Michel Cadotte, and the said Magdalen being examined separate and apart from her said husband, each severally acknowledged the foregoing instrument to be their voluntary act and deed for the uses and purposes therein expressed.

(Signed) J. P. King

Just. peace

Cxd

fees Paid $2.25

Perrault, Curot, Nelson, and Malhoit

March 8, 2014

I’ve been getting lazy, lately, writing all my posts about the 1850s and later. It’s easy to find sources about that because they are everywhere, and many are being digitized in an archival format. It takes more work to write a relevant post about the earlier eras of Chequamegon History. The sources are sparse, scattered, and the ones that are digitized or published have largely been picked over and examined by other researchers. However, that’s no excuse. Those earlier periods are certainly as interesting as the mid-19th Century. I needed to just jump in and do a project of some sort.

I’m someone who needs to know the names and personalities involved to truly wrap my head around a history. I’ve never been comfortable making inferences and generalizations unless I have a good grasp of the specific. This doesn’t become easy in the Lake Superior country until after the Cass Expedition in 1820.

But what about a generation earlier?

The dawn of the 19th-century was a dynamic time for our region. The fur trade was booming under the British North West Company. The Ojibwe were expanding in all directions, especially to west, and many of familiar French surnames that are so common in the area arrived with Canadian and Ojibwe mix-blooded voyageurs. Admittedly, the pages of the written record around 1800 are filled with violence and alcohol, but that shouldn’t make one lose track of the big picture. Right or wrong, sustainable or not, this was a time of prosperity for many. I say this from having read numerous later nostalgic accounts from old chiefs and voyageurs about this golden age.

We can meet some of the bigger characters of this era in the pages of William W. Warren and Henry Schoolcraft. In them, men like Mamaangazide (Mamongazida “Big Feet”) and Michel Cadotte of La Pointe, Beyazhig (Pay-a-jick “Lone Man) of St. Croix, and Giishkiman (Keeshkemun “Sharpened Stone”) of Lac du Flambeau become titans, covered with glory in trade, war, and influence. However, there are issues with these accounts. These two authors, and their informants, are prone toward glorifying their own family members. Considering that Schoolcraft’s (his mother-in law, Ozhaawashkodewike) and Warren’s (Flat Mouth, Buffalo, Madeline and Michel Cadotte Jr., Jean Baptiste Corbin, etc.) informants were alive and well into adulthood by 1800, we need to keep things in perspective.

The nature of Ojibwe leadership wasn’t different enough in that earlier era to allow for a leader with any more coercive power than that of the chiefs in 1850s. Mamaangazide and his son Waabojiig may have racked up great stories and prestige in hunting and war, but their stature didn’t get them rich, didn’t get them out of performing the same seasonal labors as the other men in the band, and didn’t guarantee any sort of power for their descendants. In the pages of contemporary sources, the titans of Warren and Schoolcraft are men.

Finally, it should be stated that 1800 is comparatively recent. Reading the journals and narratives of the Old North West Company can make one feel completely separate from the American colonization of the Chequamegon Region in the 1840s and ’50s. However, they were written at a time when the Americans had already claimed this area for over a decade. In fact, the long knife Zebulon Pike reached Leech Lake only a year after Francois Malhoit traded at Lac du Flambeau.

The Project

I decided that if I wanted to get serious about learning about this era, I had to know who the individuals were. The most accessible place to start would be four published fur-trade journals and narratives: those of Jean Baptiste Perrault (1790s), George Nelson (1802-1804), Michel Curot (1803-1804), and Francois Malhoit (1804-1805).

The reason these journals overlap in time is that these years were the fiercest for competition between the North West Company and the upstart XY Company of Sir Alexander MacKenzie. Both the NWC traders (such as Perrault and Malhoit) and the XY traders (Nelson and Curot) were expected to keep meticulous records during these years.

I’d looked at some of these journals before and found them to be fairly dry and lacking in big-picture narrative history. They mostly just chronicle the daily transactions of the fur posts. However, they do frequently mention individual Ojibwe people by name, something that can be lacking in other primary records. My hope was that these names could be connected to bands and villages and then be cross-referenced with Warren and Schoolcraft to fill in some of the bigger story. As the project took shape, it took the form of a map with lots of names on it. I recorded every Ojibwe person by name and located them in the locations where they met the traders, unless they are mentioned specifically as being from a particular village other than where they were trading.

I started with Perrault’s Narrative and tried to record all the names the traders and voyageurs mentioned as well. As they were mobile and much less identified with particular villages, I decided this wasn’t worth it. However, because this is Chequamegon History, I thought I should at least record those “Frenchmen” (in quotes because they were British subjects, some were English speakers, and some were mix-bloods who spoke Ojibwe as a first language) who left their names in our part of the world. So, you’ll see Cadotte, Charette, Corbin, Roy, Dufault (DeFoe), Gauthier (Gokee), Belanger, Godin (Gordon), Connor, Bazinet (Basina), Soulierre, and other familiar names where they were encountered in the journals. I haven’t tried to establish a complete genealogy for either, but I believe Perrault (Pero) and Malhoit (Mayotte) also have names that are still with us.

For each of the names on the map, I recorded the narrative or journal they appeared in:

JBP= Jean Baptiste Perrault

GN= George Nelson

MC= Michel Curot

FM= Francois Malhoit

Red Lake-Pembina area: By this time, the Ojibwe had started to spread far beyond the Lake Superior forests and into the western prairies. Perrault speaks of the Pillagers (Leech Lake Band) being absent from their villages because they had gone to hunt buffalo in the west. Vincent Roy Sr. and his sons later settled at La Pointe, but their family maintained connections in the Canadian borderlands. Jean Baptiste Cadotte Jr. was the brother of Michel Cadotte (Gichi-Mishen), the famous La Pointe trader.

Leech Lake and Sandy Lake area: The names that jump out at me here are La Brechet or Gaa-dawaabide (Broken Tooth), the great Loon-clan chief from Sandy Lake (son of Bayaaswaa mentioned in this post) and Loon’s Foot (Maangozid). The Maangozid we know as the old speaker and medicine man from Fond du Lac (read this post) was the son of Gaa-dawaabide. He would have been a teenager or young man at the time Perrault passed through Sandy Lake.

Fond du Lac and St. Croix: Augustin Belanger and Francois Godin had descendants that settled at La Pointe and Red Cliff. Jean Baptiste Roy was the father of Vincent Roy Sr. I don’t know anything about Big Marten and Little Marten of Fond du Lac or Little Wolf of the St. Croix portage, but William Warren writes extensively about the importance of the Marten Clan and Wolf Clan in those respective bands. Bayezhig (Pay-a-jick) is a celebrated warrior in Warren and Giishkiman (Kishkemun) is credited by Warren with founding the Lac du Flambeau village. Buffalo of the St. Croix lived into the 1840s. I wrote about his trip to Washington in this post.

Lac Courte Oreilles and Chippewa River: Many of the men mentioned at LCO by Perrault are found in Warren. Little (Petit) Michel Cadotte was a cousin of the La Pointe trader, Big (Gichi/La Grande) Michel Cadotte. The “Red Devil” appears in Schoolcraft’s account of 1831. The old, respected Lac du Flambeau chief Giishkiman appears in several villages in these journals. As the father of Keenestinoquay and father-in-law of Simon Charette, a fur-trade power couple, he traded with Curot and Nelson who worked with Charette in the XY Company.

La Pointe: Unfortunately, none of the traders spent much time at La Pointe, but they all mention Michel Cadotte as being there. The family of Gros Pied (Mamaangizide, “Big Feet”) the father of Waabojiig, opened up his lodge to Perrault when the trader was waylaid by weather. According to Schoolcraft and Warren, the old war chief had fought for the French on the Plains of Abraham in 1759.

Lac du Flambeau: Malhoit records many of the same names in Lac du Flambeau that Nelson met on the Chippewa River. Simon Charette claimed much of the trade in this area. Mozobodo and “Magpie” (White Crow), were his brothers-in-law. Since I’ve written so much about chiefs named Buffalo, I should point out that there’s an outside chance Le Taureau (presumably another Bizhiki) could be the famous Chief Buffalo of La Pointe.

L’Anse, Ontonagon, and Lac Vieux Desert: More Cadottes and Roys, but otherwise I don’t know much about these men.

At Mackinac and the Soo, Perrault encountered a number of names that either came from “The West,” or would find their way there in later years. “Cadotte” is probably Jean Baptiste Sr., the father of “Great” Michel Cadotte of La Pointe.

Malhoit meets Jean Baptiste Corbin at Kaministiquia. Corbin worked for Michel Cadotte and traded at Lac Courte Oreilles for decades. He was likely picking up supplies for a return to Wisconsin. Kaministiquia was the new headquarters of the North West Company which could no longer base itself south of the American line at Grand Portage.

Initial Conclusions

There are many stories that can be told from the people listed in these maps. They will have to wait for future posts, because this one only has space to introduce the project. However, there are two important concepts that need to be mentioned. Neither are new, but both are critical to understanding these maps:

1) There is a great potential for misidentifying people.

Any reading of the fur-trade accounts and attempts to connect names across sources needs to consider the following:

- English names are coming to us from Ojibwe through French. Names are mistranslated or shortened.

- Ojibwe names are rendered in French orthography, and are not always transliterated correctly.

- Many Ojibwe people had more than one name, had nicknames, or were referenced by their father’s names or clan names rather than their individual names.

- Traders often nicknamed Ojibwe people with French phrases that did not relate to their Ojibwe names.

- Both Ojibwe and French names were repeated through the generations. One should not assume a name is always unique to a particular individual.

So, if you see a name you recognize, be careful to verify it’s reall the person you’re thinking of. Likewise, if you don’t see a name you’d expect to, don’t assume it isn’t there.

2) When talking about Ojibwe bands, kinship is more important than physical location.

In the later 1800s, we are used to talking about distinct entities called the “St. Croix Band” or “Lac du Flambeau Band.” This is a function of the treaties and reservations. In 1800, those categories are largely meaningless. A band is group made up of a few interconnected families identified in the sources by the names of their chiefs: La Grand Razeur’s village, Kishkimun’s Band, etc. People and bands move across large areas and have kinship ties that may bind them more closely to a band hundreds of miles away than to the one in the next lake over.

I mapped here by physical geography related to trading posts, so the names tend to group up. However, don’t assume two people are necessarily connected because they’re in the same spot on the map.

On a related note, proximity between villages should always be measured in river miles rather than actual miles.

Going Forward

I have some projects that could spin out of these maps, but for now, I’m going to set them aside. Please let me know if you see anything here that you think is worth further investigation.

Sources:

Curot, Michel. A Wisconsin Fur Trader’s Journal, 1803-1804. Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites. Wisconsin Historical Collections, vol. XX: 396-472, 1911.

Malhoit, Francois V. “A Wisconsin Fur Trader’s Journal, 1804-05.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Reuben Gold Thwaites. Vol. 19. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1910. 163-225. Print.

Nelson, George, Laura L. Peers, and Theresa M. Schenck. My First Years in the Fur Trade: The Journals of 1802-1804. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 2002. Print.

Perrault, Jean Baptiste. Narrative of The Travels And Adventures Of A Merchant Voyager In The Savage Territories Of Northern America Leaving Montreal The 28th of May 1783 (to 1820) ed. and Introduction by, John Sharpless Fox. Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections. vol. 37. Lansing: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, Crawford Co., 1900.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Information Respecting The History,Condition And Prospects OF The Indian Tribes Of The United States. Illustrated by Capt. S. Eastman. Published by the Authority of Congress. Part III. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Company, 1953.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Philip P. Mason. Expedition to Lake Itasca; the Discovery of the Source of the Mississippi. East Lansing: Michigan State UP, 1958. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

The Enemy of my Enemy: The 1855 Blackbird-Wheeler Alliance

November 29, 2013

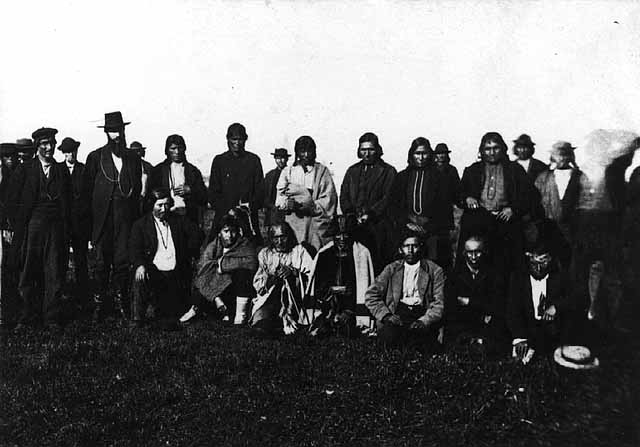

Identified by the Minnesota Historical Society as “Scene at Indian payment, probably at Odanah, Wisconsin. c. 1865.” by Charles Zimmerman. Judging by the faces in the crowd, this is almost certainly the same payment as the more-famous image that decorates the margins of the Chequamegon History site (Zimmerman MNHS Collections)

A staunch defender of Ojibwe sovereignty, and a zealous missionary dedicating his life’s work to the absolute destruction of the traditional Ojibwe way of life, may not seem like natural political allies, but as Shakespeare once wrote, “Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows.”

In October of 1855, two men who lived near Odanah, were miserable and looking for help. One was Rev. Leonard Wheeler who had founded the Protestant mission at Bad River ten years earlier. The other was Blackbird, chief of the “Bad River” faction of the La Pointe Ojibwe, that had largely deserted La Pointe in the 1830s and ’40s to get away from the men like Wheeler who pestered them relentlessly to abandon both their religion and their culture.

Their troubles came in the aftermath of the visit to La Pointe by George Manypenny, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to oversee the 1855 annuity payments. Many readers may be familiar with these events, if they’ve read Richard Morse’s account, Chief Buffalo’s obituary (Buffalo died that September while Manypenny was still on the island), or the eyewitness account by Crockett McElroy that I posted last month. Taking these sources together, some common themes emerge about the state of this area in 1855:

- After 200 years, the Ojibwe-European relationship based on give and take, where the Ojibwe negotiated from a position of power and sovereignty, was gone. American government and society had reached the point where it could by impose its will on the native peoples of Lake Superior. Most of the land was gone and with it the resource base that maintained the traditional lifestyle, Chief Buffalo was dead, and future chiefs would struggle to lead under the paternalistic thumb of the Indian Department.

- With the creation of the reservations, the Catholic and Protestant missionaries saw an opportunity, after decades of failures, to make Ojibwe hunters into Christian farmers.

- The Ojibwe leadership was divided on the question of how to best survive as a people and keep their remaining lands. Some chiefs favored rapid assimilation into American culture while a larger number sought to maintain traditional ways as best as possible.

- The mix-blooded Ojibwe, who for centuries had maintained a unique identity that was neither Native nor European, were now being classified as Indians and losing status in the white-supremacist American culture of the times. And while the mix-bloods maintained certain privileges denied to their full-blooded relatives, their traditional voyageur economy was gone and they saw treaty payments as one of their only opportunities to make money.

- As with the Treaties of 1837 and 1842, and the tragic events surrounding the attempted removals of 1850 and 1851, there was a great deal of corruption and fraud associated with the 1855 payments.

This created a volatile situation with Blackbird and Wheeler in the middle. Before, we go further, though, let’s review a little background on these men.

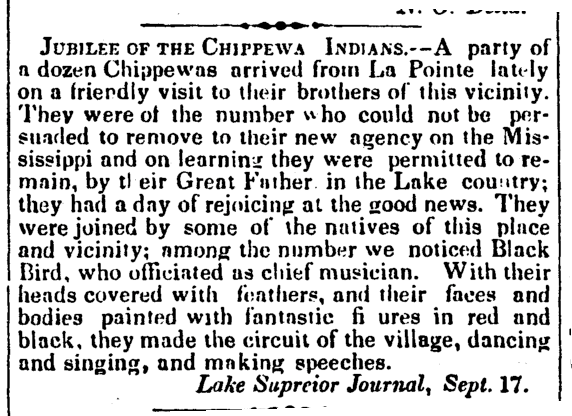

This 1851 reprint from Lake Superior Journal of Sault Ste. Marie shows how strongly Blackbird resisted the Sandy Lake removal efforts and how he was a cultural leader as well as a political leader. (New Albany Daily Ledger, October 9, 1851. Pg. 2).

Who was Blackbird?

Makadebineshii, Chief Blackbird, is an elusive presence in both the primary and secondary historical record. In the 1840s, he emerges as the practical leader of the largest faction of the La Pointe Band, but outside of Bad River, where the main tribal offices bear his name, he is not a well-known figure in the history of the Chequamegon area at all.

Unlike, Chief Buffalo, Blackbird did not sign many treaties, did not frequently correspond with government officials, and is not remembered favorably by whites. In fact, his portrayal in the primary sources is often negative. So then, why did the majority of the Ojibwe back Blackbird at the 1855 payment? The answer is probably the same reason why many whites disliked him. He was an unwavering defender of Ojibwe sovereignty, he adhered to his traditional culture, and he refused to cooperate with the United States Government when he felt the land and treaty rights of his people were being violated.

One needs to be careful drawing too sharp a contrast between Blackbird and Buffalo, however. The two men worked together at times, and Blackbird’s son James, later identified his father as Buffalo’s pipe carrier. Their central goals were the same, and both labored hard on behalf of their people, but Buffalo was much more willing to work with the Government. For instance, Buffalo’s response in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, when the fate of Ojibwe removal was undecided, was to go to the president for help. Blackbird, meanwhile, was part of the group of Ojibwe chiefs who hoped to escape the Americans by joining Chief Zhingwaakoons at Garden River on the Canadian side of Sault Ste. Marie.

Still, I hesitate to simply portray Blackbird and Buffalo as rivals. If for no other reason, I still haven’t figured out what their exact relationship was. I have not been able to find any reference to Blackbird’s father, his clan, or really anything about him prior to the 1840s. For a while, I was working under the hypothesis that he was the son of Dagwagaane (Tugwaganay/Goguagani), the old Crane Clan chief (brother of Madeline Cadotte), who usually camped by Bad River, and was often identified as Buffalo’s second chief.

However, that seems unlikely given this testimony from James Blackbird that identifies Oshkinawe, a contemporary of the elder Blackbird, as the heir of Guagain (Dagwagaane):

Statement of James Blackbird: Condition of Indian affairs in Wisconsin: hearings before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, [61st congress, 2d session], on Senate resolution, Issue 263. pg 203. (Digitized by Google Books).

It seems Commissioner Manypenny left La Pointe before the issue was entirely settled, because a month later, we find a draft letter from Blackbird to the Commissioner transcribed in Wheeler’s hand:

Mushkesebe River Oct. 1855

Blackbird. Principal chief of the Mushkisibi-river Indians to Hon. G. Manepenny Com. of Indian Affairs Washington City.

Father; Although I have seen you face to face, & had the privilege to talking freely with you, we did not do all that is to be attended to about our affairs. We have not forgotten the words you spoke to us, we still keep them in our minds. We remember you told us not to listen to all the foolish stories that was flying about–that we should listen to what was good, and mind nothing about anything else. While we listened to your advice we kept one ear open and the other shut, & [We?] kept retained all you spoke said in our ears, and. Your words are still ringing in our ears. The night that you left the sound of the paddles in boat that carried you away from us was had hardly gone ceased before the minds of some of the chiefs was were tuned by the traders from the advice you gave, but we did not listen to them. Ja-jig-wy-ong, (Buffalo’s son) son says that he & Naganub asked Mr. Gilbert if they could go to Washington to see about the affairs of the Indians. Now father, we are sure you opened your heart freely to us, and did not keep back anything from us that is for our good. We are sure you had a heart to feel for us & sympathise with us in our trials, and we think that if there is any important business to be attended to you would not have kept it secret & hid it from us, we should have knew it. If I am needed to go to Washington, to represent the interests of our people, I am ready to go. The ground that we took against about our old debts, I am ready to stand shall stand to the last. We are now in Mr. Wheelers house where you told us to go, if we had any thing to say, as Mr. W was our friend & would give us good advice. We have done so. All the chiefs & people for whom I spoke, when you were here, are of the same mind. They all requested before they left that I should go to Washington & be sure & hold on to Mr. Wheeler as one to go with me, because he has always been our steadfast friend and has al helped us in our troubles. There is another thing, my father, which makes us feel heavy hearted. This is about our reservation. Although you gave us definite instructions about it, there are some who are trying to shake our reserve all to pieces. A trader is already here against our will & without any authority from Govt, has put him up a store house & is trading with our people. In open council also at La Pointe when speaking for our people, I said we wanted Mr. W to be our teacher, but now another is come which whom we don’t want, and is putting up a house. We supposed when you spoke to us about a teacher being permitted to live among us, you had reference to the one we now have, one is enough, we do not wish to have any more, especially of the kind of him who has just come. We forbid him to build here & showed him the paper you gave us, but he said that paper permitted him rather than forbid him to come. If the chiefs & young men did not remember what you told them to keep quiet there would already be have been war here. There is always trouble when there two religions come together. Now we are weak and can do nothing and we want you to help us extend your arms to help us. Your arms can extend even to us. We want you to pity & help us in our trouble. Now we wish to know if we are wanted, or are permitted, three or four of us to come to which Washington & see to our interests, and whether our debts will be paid. We would like to have you write us immediately & let us know what your will is, when you will have us come, if at all. One thing further. We do not want any account to be allowed that was not presented to us for us to pass our opin us to pass judgement on, we hear that some such accounts have been smuggled in without our knowledge or consent.

The letter is unsigned, lacks a specific date, and has numerous corrections, which indicate it was a draft of the actual letter sent to Manypenny. This draft is found in the Wheeler Family Papers in the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center. As interesting as it is, Blackbird’s letter raises more questions than answers. Why is the chief so anxious to go to Washington? What are the other chiefs doing? What are these accounts being smuggled in? Who are the people trying to shake the reservation to pieces and what are they doing? Perhaps most interestingly, why does Blackbird, a practitioner of traditional religion, think he will get help from a missionary?

For the answer to that last question, let’s take a look at the situation of Leonard H. Wheeler. When Wheeler, and his wife, Harriet came here in 1841, the La Pointe mission of Sherman Hall was already a decade old. In a previous post, we looked at Hall’s attitudes toward the Ojibwe and how they didn’t earn him many converts. This may have been part of the reason why it was Wheeler, rather than Hall, who in 1845 spread the mission to Odanah where the majority of the La Pointe Band were staying by their gardens and rice beds and not returning to Madeline Island as often as in the past.

When compared with his fellow A.B.C.F.M. missionaries, Sherman Hall, Edmund Ely, and William T. Boutwell, Wheeler comes across as a much more sympathetic figure. He was as unbending in his religion as the other missionaries, and as committed to the destruction of Ojibwe culture, but in the sources, he seems much more willing than Hall, Ely, or Boutwell to relate to Ojibwe people as fellow human beings. He proved this when he stood up to the Government during the Sandy Lake Tragedy (while Hall was trying to avoid having to help feed starving people at La Pointe). This willingness to help the Ojibwe through political difficulties is mentioned in the 1895 book In Unnamed Wisconsin by John N. Davidson, based on the recollections of Harriet Wheeler:

From In Unnamed Wisconsin pg. 170 (Digitized by Google Books).

So, was Wheeler helping Blackbird simply because it was the right thing to do? We would have to conclude yes, if we ended it here. However, Blackbird’s letter to Manypenny was not alone. Wheeler also wrote his own to the Commissioner. Its draft is also in the Wheeler Family Papers, and it betrays some ulterior motives on the part of the Odanah-based missionary:

example not to meddle with other peoples business.

Mushkisibi River Oct. 1855

L.H. Wheeler to Hon. G.W. Manypenny

Dear Sir. In regard to what Blackbird says about going to Washington, his first plan was to borrow money here defray his expenses there, & have me start on. Several of the chiefs spoke to me before soon after you left. I told them about it if it was the general desire. In regard to Black birds Black Bird and several of the chiefs, soon after you left, spoke to me about going to Washington. I told them to let me know what important ends were to be affected by going, & how general was the desire was that I should accompany such a delegation of chiefs. The Indians say it is the wish of the Grand Portage, La Pointe, Ontonagun, L’anse, & Lake du Flambeaux Bands that wish me to go. They say the trader is going to take some of their favorite chiefs there to figure for the 90,000 dollars & they wish to go to head them off and save some of it if possible. A nocturnal council was held soon after you left in the old mission building, by some of the traders with some of the Indians, & an effort was made to get them Indians to sign a paper requesting that Mr. H.M. Rice be paid $5000 for goods sold out of the 90,000 that be the Inland Indians be paid at Chippeway River & that the said H.M. Rice be appointed agent. The Lake du Flambeau Indians would not come into the [meeting?] & divulged the secret to Blackbird. They wish to be present at [Shington?] to head off [sail?] in that direction. I told Blackbird I thought it doubtful whether I could go with him, was for borrowing money & starting immediately down the Lake this fall, but I advised him to write you first & see what you thought about the desirability of his going, & know whether his expenses would be born. Most of the claimants would be dread to see him there, & of course would not encourage his going. I am not at all certain certain that I will be [considered?] for me to go with Blackbird, but if the Dept. think it desirable, I will take it into favorable consideration. Mr. Smith said he should try to be there & thought I had better go if I could. The fact is there is so much fraud and corruption connected with this whole matter that I dread to have anything to do with it. There is hardly a spot in the whole mess upon which you can put your finger without coming in contact with the deadly virus. In regard to the Priest’s coming here, The trader the Indians refer to is Antoine [Gordon?], a half breed. He has erected a small store house here & has brought goods here & acknowledges that he has sold them and defies the Employees. Mssrs. Van Tassel & Stoddard to help [themselves?] if they can. He is a liquer-seller & a gambler. He is now putting up a house of worship, by contract for the Catholic Priest. About what the Indians said about his coming here is true. In order to ascertain the exact truth I went to the Priest myself, with Mr. Stoddard, Govt [S?] man Carpenter. His position is that the Govt have no right to interfere in matters of religion. He says he has a right to come here & put up a church if there are any of his faith here, and they permit him to build on his any of their claims. He says also that Mr. Godfrey got permission of Mr. Gilbert to come here. I replied to him that the Commissioner told me that it was not the custom of the Gov. to encourage but one denomination of Christians in a place. Still not knowing exactly the position of Govt upon the subject, I would like to ask the following questions.

1. When one Missionary Society has already commenced labors a station among a settlement of Indians, and a majority of the Indians people desire to have him for their religious teacher, have missionaries of another denomination a right to come in and commence a missionary establishment in the same settlement?

Have they a right to do it against the will of a majority of the people?

Have they a right to do it in any case without the permission of the Govt?

Has any Indian a right, by sold purchase, lease or otherwise a right to allow a missionary to build on or occupy a part of his claim? Or has the same missionary a right to arrange with several missionaries Indians for to occupy by purchase or otherwise a part of their claims severally? I ask these questions, not simply with reference to the Priest, but with regard to our own rights & privileges in case we wish to commence another station at any other point on the reserve. The coming of the Catholic Priest here is a [mere stroke of policy, concocted?] in secret by such men as Mssrs. Godfrey & Noble to destroy or cripple the protestant mission. The worst men in the country are in favor of the measure. The plan is under the wing of the priest. The plan is to get in here a French half breed influence & then open the door for the worst class of men to come in and com get an influence. Some of the Indians are put up to believe that the paper you gave Blackbird is a forgery put up by the mission & Govt employ as to oppress their mission control the Indians. One of the claimants, for whom Mr. Noble acts as attorney, told me that the same Mr. Noble told him that the plan of the attorneys was to take the business of the old debts entirely out of your hands, and as for me, I was a fiery devil they when they much[?] tell their report was made out, & here what is to become of me remains to be seen. Probably I am to be hung. If so, I hope I shall be summoned to Washington for [which purpose?] that I may be held up in [t???] to all missionaries & they be [warned?] by my […]

The dramatic ending to this letter certainly reveals the intensity of the situation here in the fall of 1855. It also reveals the intensity of Wheeler’s hatred for the Roman Catholic faith, and by extension, the influence of the Catholic mix-blood portion of the La Pointe Band. This makes it difficult to view the Protestant missionary as any kind of impartial advocate for justice. Whatever was going on, he was right in the middle of it.

So, what did happen here?

From Morse, McElroy, and these two letters, it’s clear that Blackbird was doing whatever he could to stop the Government from paying annuity funds directly to the creditors. According to Wheeler, these men were led by U.S. Senator and fur baron Henry Mower Rice. It’s also clear that a significant minority of the Ojibwe, including most of the La Pointe mix-bloods, did not want to see the money go directly to the chiefs for disbursement.

I haven’t uncovered whether the creditors’ claims were accepted, or what Manypenny wrote back to Blackbird and Wheeler, but it is not difficult to guess what the response was. Wheeler, a Massachusetts-born reformist, had been able to influence Indian policy a few years earlier during the Whig administration of Millard Fillmore, and he may have hoped for the same with the Democrats. But this was 1855. Kansas was bleeding, the North was rapidly turning toward “Free Soil” politics, and the Dred Scott case was only a few months away. Franklin Pierce, a Southern-sympathizer had won the presidency in a landslide (losing only Massachusetts and three other states) in part because he was backed by Westerners like George Manypenny and H. M. Rice. To think the Democratic “Indian Ring,” as it was described above, would listen to the pleas coming from Odanah was optimistic to say the least.

“[E]xample not to meddle with other peoples business” is written at the top of Wheeler’s draft. It is his handwriting, but it is much darker than the rest of the ink and appears to have been added long after the fact. It doesn’t say it directly, but it seems pretty clear Wheeler didn’t look back on this incident as a success. I’ll keep looking for proof, but for now I can say with confidence that the request for a Washington delegation was almost certainly rejected outright.

So who are the good guys in this situation?

If we try to fit this story into the grand American narrative of Manifest Destiny and the systematic dispossession of Indian peoples, then we would have to conclude that this is a story of the Ojibwe trying to stand up for their rights against a group of corrupt traders. However, I’ve never had much interest in this modern “Dances With Wolves” version of Indian victimization. Not that it’s always necessarily false, but this narrative oversimplifies complex historical events, and dehumanizes individual Indians as much as the old “hostile savages” framework did. That’s why I like to compare the Chequamegon story more to the Canadian narrative of Louis Riel and company than to the classic American Little Bighorn story. The dispossession and subjugation of Native peoples is still a major theme, but it’s a lot messier. I would argue it’s a lot more accurate and more interesting, though.

So let’s evaluate the individuals involved rather than the whole situation by using the most extreme arguments one could infer from these documents and see if we can find the truth somewhere in the middle:

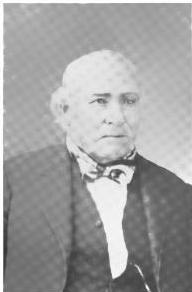

Henry Mower Rice (Wikimedia Images)

Henry M. Rice

The case against: H. M. Rice was businessman who valued money over all else. Despite his close relationship with the Ho-Chunk people, he pressed for their 1847 removal because of the enormous profits it brought. A few years later, he was the driving force behind the Sandy Lake removal of the Ojibwe. Both of these attempted removals came at the cost of hundreds of lives. There is no doubt that in 1855, Rice was simply trying to squeeze more money out of the Ojibwe.

The case for: H. M. Rice was certainly a businessman, and he deserved to be paid the debts owed him. His apparent actions in 1855 are the equivalent of someone having a lien on a house or car. That money may have justifiably belonged to him. As for his relationship with the Ojibwe, Rice continued to work on their behalf for decades to come, and can be found in 1889 trying to rectify the wrongs done to the Lake Superior bands when the reservations were surveyed.

From In Unnamed Wisconsin pg. 168. It’s not hard to figure out which Minnesota senator is being referred to here in this 1895 work informed by Harriet Wheeler. (Digitized by Google Books).

Antoine Gordon from Noble Lives of a Noble Race (pg. 207) published by the St. Mary’s Industrial School in Odanah.

Antoine Gordon

The case against: Antoine Gaudin (Gordon) was an unscrupulous trader and liquor dealer who worked with H. M. Rice to defraud his Ojibwe relatives during the 1855 annuities. He then tried to steal land and illegally squat on the Bad River Reservation against the expressed wishes of Chief Blackbird and Commissioner Manypenny.

The case for: Antoine Gordon couldn’t have been working against the Ojibwe since he was an Ojibwe man himself. He was a trader and was owed debts in 1855, but most of the criticism leveled against him was simply anti-Catholic libel from Leonard Wheeler. Antoine was a pious Catholic, and many of his descendants became priests. He built the church at Bad River because there were a number of people in Bad River who wanted a church. Men like Gordon, Vincent Roy Jr., and Joseph Gurnoe were not only crucial to the development of Red Cliff (as well as Superior and Gordon, WI) as a community, they were exactly the type of leaders the Ojibwe needed in the post-1854 world.

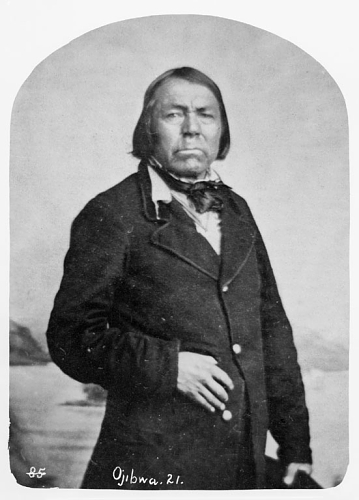

Portrait of Naw-Gaw-Nab (The Foremost Sitter) n.d by J.E. Whitney of St. Paul (Smithsonian)

Naaganab

The case against: Chiefs like Naaganab and Young Buffalo sold their people out for a quick buck. Rather than try to preserve the Ojibwe way of life, they sucked up to the Government by dressing like whites, adopting Catholicism, and using their favored position for their own personal gain and to bolster the position of their mix-blooded relatives.

The case for: If you frame these events in terms of Indians vs. Traders, you then have to say that Naaganab, Young Buffalo, and by extension Chief Buffalo were “Uncle Toms.” The historical record just doesn’t support this interpretation. The elder Buffalo and Naaganab each lived for nearly a century, and they each strongly defended their people and worked to preserve the Ojibwe land base. They didn’t use the same anti-Government rhetoric that Blackbird used at times, but they were working for the same ends. In fact, years later, Naaganab abandoned his tactic of assimilation as a means to equality, telling Rice in 1889:

“We think the time is past when we should take a hat and put it on our heads just to mimic the white man to adopt his custom without being allowed any of the privileges that belong to him. We wish to stand on a level with the white man in all things. The time is past when my children should stand in fear of the white man and that is almost all that I have to say (Nah-guh-nup pg. 192).”

Leonard H. Wheeler

L. H. Wheeler (WHS Image ID 66594)

The case against: Leonard Wheeler claimed to be helping the Ojibwe, but really he was just looking out for his own agenda. He hated the Catholic Church and was willing to do whatever it took to keep the Catholics out of Bad River including manipulating Blackbird into taking up his cause when the chief was the one in need. Wheeler couldn’t mind his own business. He was the biggest enemy the Ojibwe had in terms of trying to maintain their traditions and culture. He didn’t care about Blackbird. He just wanted the free trip to Washington.

The case for: In contrast to Sherman Hall and some of the other missionaries, Leonard Wheeler was willing to speak up forcefully against injustice. He showed this during the Sandy Lake removal and again during the 1855 payment. He saw the traders trying to defraud the Ojibwe and he stood up against it. He supported Blackbird in the chief’s efforts to protect the territorial integrity of the Bad River reservation. At a risk to his own safety, he chose to do the right thing.

Blackbird

The case against: Blackbird was opportunist trying to seize power after Buffalo’s death by playing to the outdated conservative impulses of his people at a time when they should have been looking to the future rather than the past. This created harmful factional differences that weakened the Ojibwe position. He wanted to go to Washington because it would make him look stronger and he manipulated Wheeler into helping him.

The case for: From the 1840s through the 1860s, the La Pointe Ojibwe had no stronger advocate for their land, culture, and justice than Chief Blackbird. While other chiefs thought they could work with a government that was out to destroy them, Blackbird never wavered, speaking consistently and forcefully for land and treaty rights. The traders, and other enemies of the Ojibwe, feared him and tried to keep their meetings and Washington trip secret from him, but he found out because the majority of the people supported him.

I’ve yet to find a picture of Blackbird, but this 1899 Bad River delegation to Washington included his son James (bottom right) along with Henry and Jack Condecon, George Messenger, and John Medegan–all sons and/or grandsons of signers of the Treaty of 1854 (Photo by De Lancey Gill; Smithsonian Collections).

Final word for now…

An entire book could be written about the 1855 annuity payments, and like so many stories in Chequamegon History, once you start the inquiry, you end up digging up more questions than answers. I can’t offer a neat and tidy explanation for what happened with the debts. I’m inclined to think that if Henry Rice was involved it was probably for his own enrichment at the expense of the Ojibwe, but I have a hard time believing that Buffalo, Jayjigwyong, Naaganab, and most of the La Pointe mix-bloods would be doing the same. Blackbird seems to be the hero in this story, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if there was a political component to his actions as well. Wheeler deserves some credit for his defense of a position that alienated him from most area whites, but we have to take anything he writes about his Catholic neighbors with a grain of salt.

As for the Blackbird-Wheeler relationship, showcasing these two fascinating letters was my original purpose in writing this post. Was Blackbird manipulating Wheeler, was Wheeler manipulating Blackbird, or was neither manipulating the other? Could it be that the zealous Christian missionary and the stalwart “pagan” chief, were actually friends? What do you think?

Sources:

Davidson, J. N., and Harriet Wood Wheeler. In Unnamed Wisconsin: Studies in the History of the Region between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi. Milwaukee, WI: S. Chapman, 1895. Print.

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

McElroy, Crocket. “An Indian Payment.” Americana v.5. American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Pupil’s of St. Mary’s, and Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration. Noble Lives of a Noble Race. Minneapolis: Brooks, 1909. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

No Princess Zone: Hanging Cloud, the Ogichidaakwe

May 12, 2013

This image of Aazhawigiizhigokwe (Hanging Cloud) was created 35 years after the battle depicted by Marr and Richards Engraving of Milwaukee for use in Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).

Here is an interesting story I’ve run across a few times. Don’t consider this exhaustive research on the subject, but it’s something I thought was worth putting on here.

In late 1854 and 1855, the talk of northern Wisconsin was a young woman from from the Chippewa River around Rice Lake. Her name was Ah-shaw-way-gee-she-go-qua, which Morse (below) translates as “Hanging Cloud.” Her father was Nenaa’angebi (Beautifying Bird) a chief who the treaties record as part of the Lac Courte Oreilles band. His band’s territory, however, was further down the Chippewa from Lac Courte Oreilles, dangerously close to the territories of the Dakota Sioux. The Ojibwe and Dakota of that region had a long history of intermarriage, but the fallout from the Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1825) led to increased incidents of violence. This, along with increased population pressures combined with hunting territory lost to white settlement, led to an intensification of warfare between the two nations in the mid-18th century.

As you’ll see below, Hanging Cloud gained her fame in battle. She was an ogichidaakwe (warrior). Unfortunately, many sources refer to her as the “Chippewa Princess.” She was not a princess. Her father was not a king. She did not sit in a palace waited on hand and foot. Her marriageability was not her only contribution to her people. Leave the princesses in Europe. Hanging Cloud was an ogichidaakwe. She literally fought and killed to protect her people.

Americans have had a bizarre obsession with the idea of Indian princesses since Pocahontas. Engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe (1616) Wikimedia Images

Americans have had a bizarre obsession with the idea of Indian princesses since Pocahontas. Engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe (1616) Wikimedia ImagesIn An Infinity of Nations, Michael Witgen devotes a chapter to America’s ongoing obsession with the concept of the “Indian Princess.” He traces the phenomenon from Pocahontas down to 21st-century white Americans claiming descent from mythical Cherokee princesses. He has some interesting thoughts about the idea being used to justify the European conquest and dispossession of Native peoples. I’m going to try to stick to history here and not get bogged down in theory, but am going to declare northern Wisconsin a “NO PRINCESS ZONE.”

Ozhaawashkodewekwe, Madeline Cadotte, and Hanging Cloud were remarkable women who played a pivotal role in history. They are not princesses, and to describe them as such does not add to their credit. It detracts from it.

Anyway, rant over, the first account of Hanging Cloud reproduced here comes from Dr. Richard E. Morse of Detroit. He observed the 1855 annuity payment at La Pointe. This was the first payment following the Treaty of 1854, and it was overseen directly by Indian Affairs Commissioner George Manypenny. Morse records speeches of many of the most prominent Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs at the time, records the death of Chief Buffalo in September of that year, and otherwise offers his observations. These were published in 1857 as The Chippewas of Lake Superior in the third volume of the State Historical Society’s Wisconsin Historical Collections. This is most of pages 349 to 354:

“The “Princess”–AH-SHAW-WAY-GEE-SHE-GO-QUA–The Hanging Cloud.

The Chippewa Princess was very conspicuous at the payment. She attracted much notice; her history and character were subjects of general observation and comment, after the bands, to which she was, arrived at La Pointe, more so than any other female who attended the payment.

She was a chivalrous warrior, of tried courage and valor; the only female who was allowed to participate in the dancing circles, war ceremonies, or to march in rank and file, to wear the plumes of the braves. Her feats of fame were not long in being known after she arrived; most persons felt curious to look upon the renowned youthful maiden.

Nenaa’angebi as depicted on the cover of Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).

Nenaa’angebi as depicted on the cover of Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).She is the daughter of Chief NA-NAW-ONG-GA-BE, whose speech, with comments upon himself and bands, we have already given. Of him, who is the gifted orator, the able chieftain, this maiden is the boast of her father, the pride of her tribe. She is about the usual height of females, slim and spare-built, between eighteen and twenty years of age. These people do not keep records, nor dates of their marriages, nor of the birth of their children.

This female is unmarried. No warrior nor brave need presume to win her heart or to gain her hand in marriage, who cannot prove credentials to superior courage and deeds of daring upon the war-path, as well as endurance in the chase. On foot she was conceded the fleetest of her race. Her complexion is rather dark, prominent nose, inclining to the Roman order, eyes rather large and very black, hair the color of coal and glossy, a countenance upon which smiles seemed strangers, an expression that indicated the ne plus ultra of craft and cunning, a face from which, sure enough, a portentous cloud seemed to be ever hanging–ominous of her name. We doubt not, that to plunge the dagger into the heart of an execrable Sioux, would be more grateful to her wish, more pleasing to her heart, than the taste of precious manna to her tongue…

…Inside the circle were the musicians and persons of distinction, not least of whom was our heroine, who sat upon a blanket spread upon the ground. She was plainly, though richly dressed in blue broad-cloth shawl and leggings. She wore the short skirt, a la Bloomer, and be it known that the females of all Indians we have seen, invariably wear the Bloomer skirt and pants. Their good sense, in this particular, at least, cannot, we think, be too highly commended. Two plumes, warrior feathers, were in her hair; these bore devices, stripes of various colored ribbon pasted on, as all braves have, to indicate the number of the enemy killed, and of scalps taken by the wearer. Her countenance betokened self-possession, and as she sat her fingers played furtively with the haft of a good sized knife.

The coterie leaving a large kettle hanging upon the cross-sticks over a fire, in which to cook a fat dog for a feast at the close of the ceremony, soon set off, in single file procession, to visit the camp of the respective chiefs, who remained at their lodges to receive these guests. In the march, our heroine was the third, two leading braves before her. No timid air and bearing were apparent upon the person of this wild-wood nymph; her step was proud and majestic, as that of a Forest Queen should be.

The party visited the various chiefs, each of whom, or his proxy, appeared and gave a harangue, the tenor of which, we learned, was to minister to their war spirit, to herald the glory of their tribe, and to exhort the practice of charity and good will to their poor. At the close of each speech, some donation to the beggar’s fun, blankets, provisions, &c., was made from the lodge of each visited chief. Some of the latter danced and sung around the ring, brandishing the war-club in the air and over his head. Chief “LOON’S FOOT,” whose lodge was near the Indian Agents residence, (the latter chief is the brother of Mrs. Judge ASHMAN at the Soo,) made a lengthy talk and gave freely…

…An evening’s interview, through an interpreter, with the chief, father of the Princess, disclosed that a small party of Sioux, at a time not far back, stole near unto the lodge of the the chief, who was lying upon his back inside, and fired a rifle at him; the ball grazed his nose near his eyes, the scar remaining to be seen–when the girl seizing the loaded rifle of her father, and with a few young braces near by, pursued the enemy; two were killed, the heroine shot one, and bore his scalp back to the lodge of NA-NAW-ONG-GA-BE, her father.

At this interview, we learned of a custom among the Chippewas, savoring of superstition, and which they say has ever been observed in their tribe. All the youths of either sex, before they can be considered men and women, are required to undergo a season of rigid fasting. If any fail to endure for four days without food or drink, they cannot be respected in the tribe, but if they can continue to fast through ten days it is sufficient, and all in any case required. They have then perfected their high position in life.

This Princess fasted ten days without a particle of food or drink; on the tenth day, feeble and nervous from fasting, she had a remarkable vision which she revealed to her friends. She dreamed that at a time not far distant, she accompanied a war party to the Sioux country, and the party would kill one of the enemy, and would bring home his scalp. The war party, as she had dreamed, was duly organized for the start.

Against the strongest remonstrance of her mother, father, and other friends, who protested against it, the young girl insisted upon going with the party; her highest ambition, her whole destiny, her life seemed to be at stake, to go and verify the prophecy of her dream. She did go with the war party. They were absent about ten or twelve days, the had crossed the Mississippi, and been into the Sioux territory. There had been no blood of the enemy to allay their thirst or to palliate their vengeance. They had taken no scalp to herald their triumphant return to their home. The party reached the great river homeward, were recrossing, when lo! they spied a single Sioux, in his bark canoe near by, whom they shot, and hastened exultingly to bear his scalp to their friends at the lodges from which they started. Thus was the prophecy of the prophetess realized to the letter, and herself, in the esteem of all the neighboring bands, elevated to the highest honor in all their ceremonies. They even hold her in superstitious reverence. She alone, of the females, is permitted in all festivities, to associate, mingle and to counsel with the bravest of the braves of her tribe…”

Benjamin Armstrong

Benjamin ArmstrongBenjamin Armstrong’s memoir Early Life Among the Indians also includes an account of the warrior daughter of Nenaa’angebi. In contrast to Morse, the outside observer, Armstrong was married to Buffalo’s niece and was the old chief’s personal interpreter. He lived in this area for over fifty years and knew just about everyone. His memoir, published over 35 years after Hanging Cloud got her fame, contains details an outsider wouldn’t have any way of knowing.

Unfortunately, the details don’t line up very well. Most conspicuously, Armstrong says that Nenaa’angebi was killed in the attack that brought his daughter fame. If that’s true, then I don’t know how Morse was able to record the Rice Lake chief’s speeches the following summer. It’s possible these were separate incidents, but it is more likely that Armstrong’s memories were scrambled. He warns us as much in his introduction. Some historians refuse to use Armstrong at all because of discrepancies like this and because it contains a good deal of fiction. I have a hard time throwing out Armstrong completely because he really does have the insider’s knowledge that is lacking in so many primary sources about this area. I don’t look at him as a liar or fraud, but rather as a typical northwoodsman who knows how to run a line of B.S. when he needs to liven up a story. Take what you will of it, these are pages 199-202 of Early Life Among the Indians.

“While writing about chiefs and their character it may not be amiss to give the reader a short story of a chief‟s daughter in battle, where she proved as good a warrior as many of the sterner sex.

In the ’50’s there lived in the vicinity of Rice Lake, Wis. a band of Indians numbering about 200. They were headed by a chief named Na-nong-ga-bee. This chief, with about seventy of his people came to La Point to attend the treaty of 1854. After the treaty was concluded he started home with his people, the route being through heavy forests and the trail one which was little used. When they had reached a spot a few miles south of the Namekagon River and near a place called Beck-qua-ah-wong they were surprised by a band of Sioux who were on the warpath and then in ambush, where a few Chippewas were killed, including the old chief and his oldest son, the trail being a narrow one only one could pass at a time, true Indian file. This made their line quite long as they were not trying to keep bunched, not expecting or having any thought of being attacked by their life long enemy.

The chief, his son and daughter were in the lead and the old man and his son were the first to fall, as the Sioux had of course picked them out for slaughter and they were killed before they dropped their packs or were ready for war. The old chief had just brought the gun to his face to shoot when a ball struck him square in the forehead. As he fell, his daughter fell beside him and feigned death. At the firing Na-nong-ga-bee’s Band swung out of the trail to strike the flanks of the Sioux and get behind them to cut off their retreat, should they press forward or make a retreat, but that was not the Sioux intention. There was not a great number of them and their tactic was to surprise the band, get as many scalps as they could and get out of the way, knowing that it would be but the work of a few moments, when they would be encircled by the Chippewas. The girl lay motionless until she perceived that the Sioux would not come down on them en-masse, when she raised her father‟s loaded gun and killed a warrior who was running to get her father‟s scalp, thus knowing she had killed the slayer of her father, as no Indian would come for a scalp he had not earned himself. The Sioux were now on the retreat and their flank and rear were being threatened, the girl picked up her father‟s ammunition pouch, loaded the rifle, and started in pursuit. Stopping at the body of her dead Sioux she lifted the scalp and tucked it under her belt. She continued the chase with the men of her band, and it was two days before they returned to the women and children, whom they had left on the trail, and when the brave little heroine returned she had added two scalps to the one she started with.

She is now living, or was, but a few years ago, near Rice Lake, Wis., the wife of Edward Dingley, who served in the war of rebellion from the time of the first draft of soldiers to the end of the war. She became his wife in 1857, and lived with him until he went into the service, and at this time had one child, a boy. A short time after he went to the war news came that all the party that had left Bayfield at the time he did as substitutes had been killed in battle, and a year or so after, his wife, hearing nothing from him, and believing him dead, married again. At the end of the war Dingley came back and I saw him at Bayfield and told him everyone had supposed him dead and that his wife had married another man. He was very sorry to hear this news and said he would go and see her, and if she preferred the second man she could stay with him, but that he should take the boy. A few years ago I had occasion to stop over night with them. And had a long talk over the two marriages. She told me the circumstances that had let her to the second marriage. She thought Dingley dead, and her father and brother being dead, she had no one to look after her support, or otherwise she would not have done so. She related the related the pursuit of the Sioux at the time of her father‟s death with much tribal pride, and the satisfaction she felt at revenging herself upon the murder of her father and kinsmen. She gave me the particulars of getting the last two scalps that she secured in the eventful chase. The first she raised only a short distance from her place of starting; a warrior she espied skulking behind a tree presumably watching for some one other of her friends that was approaching. The other she did not get until the second day out when she discovered a Sioux crossing a river. She said: “The good luck that had followed me since I raised my father‟s rifle did not now desert me,” for her shot had proved a good one and she soon had his dripping scalp at her belt although she had to wade the river after it.”

At this point, this is all I have to offer on the story of Hanging Cloud the ogichidaakwe. I’ll be sure to update if I stumble across anything else, but for now, we’ll have to be content with these two contradictory stories.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892. Print.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Witgen, Michael J. An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012. Print.

Kah-puk-wi-e-kah: Cornucopia, Herbster, or Port Wing?

March 30, 2013

Official railroad map of Wisconsin, 1900 / prepared under the direction of Graham L. Rice, Railroad Commissioner. (Library of Congress) Check out Steamboat Island in the upper right. According to the old timers, that’s the one that washed away.

Not long ago, a long-running mystery was solved for me. Unfortunately, the outcome wasn’t what I was hoping for, but I got to learn a new Ojibwe word and a new English word, so I’ll call it a victory. Plus, there will be a few people–maybe even a dozen who will be interested in what I found out.

Go Big Red!

First a little background for those who haven’t spent much time in Cornucopia, Herbster, or Port Wing. The three tiny communities on the south shore have a completely friendly but horribly bitter animosity toward one another. Sure they go to school together, marry each other, and drive their firetrucks in each others’ parades, but every Cornucopian knows that a Fish Fry is superior to a Smelt Fry, and far superior to a Fish Boil. In the same way, every Cornucopian remembers that time the little league team beat PW. Yeah, that’s right. It was in the tournament too!

If you haven’t figured it out yet, my sympathies lie with Cornucopia, and most of the animosity goes to Port Wing (after all, the Herbster kids played on our team). That’s why I’m upset with the outcome of this story even though I solved a mystery that had been nagging me.

“A bay on the lake shore situated forty miles west of La Pointe…”

This all began several years ago when I read William W. Warren’s History of the Ojibway People for the first time. Warren, a mix-blood from La Pointe, grew up speaking Ojibwe on the island. His American father sent him to the East to learn to read and write English, and he used his bilingualism to make a living as an interpreter when he returned to Lake Superior. His mother was a daughter of Michel and Madeline Cadotte, and he was related to several prominent people throughout Ojibwe country. His History is really a collection of oral histories obtained in interviews with chiefs and elders in the late 1840s and early 1850s. He died in 1853 at age 28, and his manuscript sat unpublished for several decades. Luckily for us, it eventually was, and for all its faults, it remains the most important book about the history of this area.

As I read Warren that first time, one story in particular jumped out at me:

Warren, William W. History of the Ojibway Nation. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1885. Print. Pg. 127 Available on Google Books.

Pg. 129 Warren uses the sensational racist language of the day in his description of warfare between the Fox and his Ojibwe relatives. Like most people, I cringe at lines like “hellish whoops” or “barbarous tortures which a savage could invent.” For a deeper look at Warren the man, his biases, and motivations, I strongly recommend William W. Warren: the life, letters, and times of an Ojibwe leader by Theresa Schenck (University of Nebraska Press, 2007)

I recognized the story right away:

Cornucopia, Wisconsin postcard image by Allan Born. In the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society (WHI Image ID: 84185)

This marker, put up in 1955, is at the beach in Cornucopia. To see it, go east on the little path by the artesian well.

It’s clear Warren is the source for the information since it quotes him directly. However, there is a key difference. The original does not use the word “Siskiwit” (a word derived from the Ojibwe for the “Fat” subspecies of Lake Trout abundant around Siskiwit Bay) in any way. It calls the bay Kah-puk-wi-e-kah and says it’s forty miles west of La Pointe. This made me suspect that perhaps this tragedy took place at one of the bays west of Cornucopia. Forty miles seemed like it would get you a lot further west of La Pointe than Siskiwit Bay, but then I figured it might be by canoe hugging the shoreline around Point Detour. This would be considerably longer than the 15-20 miles as the crow flies, so I was somewhat satisfied on that point.

Still, Kah-puk-wi-e-kah is not Siskiwit, so I wasn’t certain the issue was resolved. My Ojibwe skills are limited, so I asked a few people what the word means. All I could get was that the “Kah” part was likely “Gaa,” a prefix that indicates past tense. Otherwise, Warren’s irregular spelling and dropped endings made it hard to decipher.

Then, in 2007, GLIFWC released the amazing Gidakiiminaan (Our Earth): An Anishinaabe Atlas of the 1836, 1837, and 1842 Treaty Ceded Territories. This atlas gives Ojibwe names and translations for thousands of locations. On page 8, they have the south shore. Siskiwit Bay is immediately ruled out as Kah-puk-wi-e-kah, and so is Cranberry River (a direct translation of the Ojibwe Mashkiigiminikaaniwi-ziibi. However, two other suspects emerge. Bark Bay (the large bay between Cornucopia and Herbster) is shown as Apakwaani-wiikwedong, and the mouth of the Flagg River (Port Wing) is Gaa-apakwaanikaaning.

On the surface, the Port Wing spelling was closer to Warren’s, but with “Gaa” being a droppable prefix, it wasn’t a big difference. The atlas uses the root word apakwe to translate both as “the place for getting roofing-bark,” Apakwe in this sense referring to rolls of birch bark covering a wigwam. For me it was a no-brainer. Bark Bay is the biggest, most defined bay in the area. Port Wing’s harbor is really more of a swamp on relatively straight shoreline. Plus, Bark Bay has the word “bark” right in it. Bark River goes into Bark Bay which is protected by Bark Point. Bark, bark, bark–roofing bark–Kapukwiekah–done.

Cornucopia had lost its one historical event, but it wasn’t so bad. Even though Bark Bay is closer to Herbster, it’s really between the two communities. I was even ready to suggest taking the word “Siskiwit” off the sign and giving it to Herbster. I mean, at least it wasn’t Port Wing, right?

Over the next few years, it seemed my Bark Bay suspicions were confirmed. I encountered Joseph Nicollet’s 1843 map of the region: