Wheeler Papers: 1854 La Pointe before the Treaty

August 7, 2017

By Amorin Mello

Selected letters from the

Wheeler Family Papers,

Box 3, Folders 11-12; La Pointe County.

Crow-wing, Min. Ter.

Jan. 9th 1854

Brother Wheeler,

Reverend Leonard Hemenway Wheeler ~ In Unnamed Wisconsin by Silas Chapman, 1895, cover image.

Though not indebted to you just now on the score of correspondence, I will venture to intrude upon you a few lines more. I will begin by saying we are all tolerably well. But we are somewhat uncomfortable in some respects. Our families are more subject to colds this winter than usual. This probably may be attributed in part at least to our cold and open houses. We were unable last fall to do any thing more than fix ourselves temporarily, and the frosts of winter find a great many large holes to creep in at. Some days it is almost impossible for us to keep warm enough to be comfortable.

Our prospects for accomplishing much for the Indians here I do not think look more promising than they did last fall. There are but few Indians here. These get drunk every time they can get whiskey, of which there is an abundance nearby. Among the white people here, none are disposed to attend meetings much except Mr. [Welton?]. He and his wife are discontented and unhappy here, and will probably get away as soon as they can. We hear not a word from the Indian Department. Why they are minding us in this manner I cannot tell. But I should like it much better, if they would tell us at once to be gone. I have got enough of trying to do anything for Indians in connection with the Government. We can put no dependence upon any thing they will do. I have tried the experiment till I am satisfied. I think much more could be done with a boarding school in the neighborhood of Lapointe than here And my opinion is, that since things have turned out as they have here, we had better get out of it as soon as we can. With such an agent as we now have, nothing will prosper here. He is enough to poison everything, and will do more moral evil in such a community, as this, than a half a dozen missionaries can do good. My opinion is, that if they knew at Washington how things are and have been managed here, there would be a change. But I do not feel certain of this. For I sometimes am tempted to adopt the opinion that they do not care much there how things go here. But should there be a change, I have little hope that is would would make things materially better. The moral and social improvement of the Indians, I fear, has little to do with the appointment of agents and superintendents. I do not think I ought to remain here very long and keep my family here, as things are now going. If we were not involved with the Government with regard to the school matter, I would advise the Committee to quit here as soon as we can find a place to go to. My health is not very good. The scenes, and labors and attacks of sickness which I have passed through during the past two years have made almost a wreck of my constitution. It might rally under some circumstances. But I do not think it will while I stay here, so excluded from society, and so harassed with cares and perplexities as I have been and as I am likely to be in future, should we go on and try to get up a school. My wife is in no better spirits than I am. She has had several quite ill turns this winter. the children all wish to get away from here, and I do not know that I shall have power to keep them here, even if I am to stay.

But what to do I do not know. The Committee say they do not wish to abandon the Ojibwas. I cannot in future favor the removal of the lake Indians. I believe that all the aid they will receive from the Government will never civilize or materially benifit them. I judge from the manner in which things have been managed here. Our best hope is to do what we can to aid them where they are to live peaceably with the whites, and to improve and become citizens. The idea of the Government sending infidels and heathens here to civilize and Christianize the Indians is rediculous.

I always thought it doubtful whether the experiment we are trying would succeed. In that case it was my intention to remove somewhere below here, and try to get a living, either by raising my potatoes or by trying to preach to white people, or by uniting both. but I do not hardly feel strong enough to begin entirely anew in the wilderness to make me a home. I suppose my family would be as happy at Lapointe, as they would any where in the new and scattered settlements for fifty or a hundred miles below here. And if thought I could support myself then, I might think of going back there. There are our old friends for whose improvement we have laborred so many years. I feel almost as much attachment for them as for my won children. And I do not think they ought to be left like sheep upon the mountains without a shepherd. And if the Board think it best to expend money and labor for the Ojibwas, they had better expend it there than here, as things now are at least. I think we were exerting much much more influence there before we left, then we have here or are likely to exert. I have no idea that the lake Indians will ever remove to this place, or to this region.

Reverend Sherman Hall

~ Madeline Island Museum

What do you think of recommending to the Board to day to exert a greater influence on the people in the neighborhood of Lapointe[?/!] I feel reluctant to give up the Indians. And if I could get a living at Lapointe, and could get there, I should be almost disposed to go back and live among those few for whom I have labored so long, if things turn out here as I expect they will. I have not much funds to being life with now, nor much strength to dig with. But still I shall have to dig somewhere. The land is easier tilled in this region than that about the lake. But wood is more scarce. My family do not like Minesota. Perhaps they would, if they should get out of the Indian country. Edwin says he will get out of it in the spring, and Miles says he will not stay in such a lonesome place. I shall soon be alone as to help from my children. My boys must take care of themselves as soon as they arrive at a suitable age, and will leave me to take care of myself. We feel very unsettled. Our affairs here must assume a different aspect, or we cannot remain here many months longer. Is there enough to do at Lapointe; or is there a prospect that there will soon be business to draw people enough then, to make it an object to try to establish the institution of the gospel there? Write me and let me know your views on such subjects as these.

[Unsigned, but appears to be from Sherman Hall]

Crow-wing Feb. 10th 1854

Brother Wheeler:

I received your letter of jan. 16th yesterday, and consequently did not sleep as much as usual last night. We were glad to hear that you are all well and prosperous. We too are well which we consider a great blessing, as sickness in present situation would be attended with great inconvenience. Our house is exceedingly cold and has been uncomfortable during some of the severe cold weather have had during the last months. Yet we hope to get through the winter without suffering severely. In many respects our missionary spirit has been put to a severer test than at any previous time since we have been in the Indian country, during the past year. We feel very unsettled, and of course somewhat uneasy. The future does not look very bright. We cannot get a word from the Indian Department whether we may go on or not. If we cannot get some answer from them before long I shall be taking measures to retire. We have very little to hope, I apprehend, from all the aid the Government will render to words the civilization and moral and intellectual improvement of the Indians. For missionaries or Indians to depend on them, is to depend on a broken staff.

~ Minnesota Historical Society

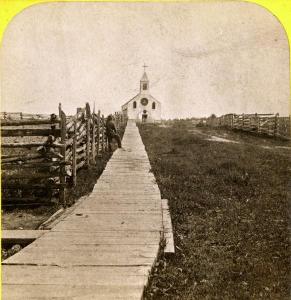

“The American Fur Company therefore built a ‘New Fort’ a few miles farther north, still upon the west shore of the island, and to this place, the present village, the name La Pointe came to be transferred. Half-way between the ‘Old fort’ and the ‘New fort,’ Mr. Hall erected (probably in 1832) ‘a place for worship and teaching,’ which came to be the centre of Protestant missionary work in Chequamegon Bay.”

~ The Story of Chequamegon Bay

I do not see that our house is so divided against itself, that it is in any great danger of falling at present. My wife never did wish to leave Lapointe and we have ever, both of us, thought that the station ought not to be abandoned, unless the Indians were removed. But this seemed not to be the opinion of the committee or of our associates, if I rightly understood them. I had a hard struggle in my mind whether to retire wholly from the service of the Board among the Indians, or to come here and make a further experiment. I felt reluctant to leave them, till we had tried every experiment which held out any promise of success. When I remove my family here our way ahead looked much more clear than it does now. I had completed an arrangement for the school which had the approval of Gov. Ramsey, and which fell through only in consequence of a little informality on his part, and because a new set of officers just then coming into power must show themselves a little wiser than their predecessors. Had not any associates come through last summer, so as to relieve me of some of my burdens and afford some society and counsel in my perplexities I could not have sustained the burden upon me in the state of my health at that time. A change of officers here too made quite an unfavorable change in our prospects. I have nothing to reproach myself with in deciding to come here, nor in coming when we did, though the result of our coming may not be what we hoped it would be. I never anticipated any great pleasure in being connected with a school connected in any way with the Government, nor did I suppose I should be long connected with it, even if it prospered. I have made the effort and now if it all falls, I shall feel that Providence has not a work for us to do here. The prospects of the Indians look dark, what is before me in the future I do not know. My health is not good, though relief from some of the pressure I had to sustain for a time last fall and the cold season has somewhat [?????] me for the time being. But I cannot endure much excitement, and of course our present unsettled affairs operate unfavorably upon it. I need for a time to be where I can enjoy rest from everything exciting, and when I can have more society that I have here, and to be employed moderately in some regular business.

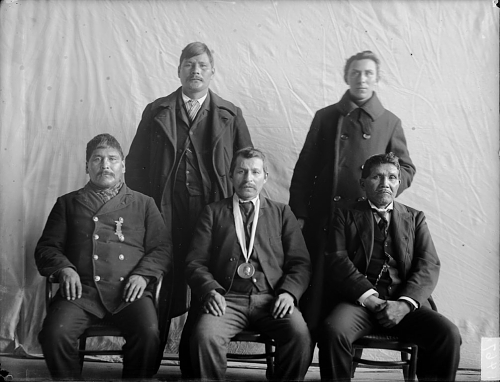

Antoine Gordon [Gaudin]

~ Noble Lives of a Noble Race by the St. Mary’s Industrial School (Bad River Indian Reservation), 1909, page 207.

Charles Henry Oakes

~ Findagrave.com

As to your account I have not had time to examine it, but will write you something about it by & by. As to any account which Antoine Gaudin has against me, I wish you would have him send it to me in detail before you pay it. I agreed with Mr. Nettleton to settle with him, and paid him the balance due to Antoine as I had the account. I suppose he made the settlement, when he was last at Lapointe. As to the property at Lapointe, I shall immediately write to Mr. Oakes about it. But I suppose in the present state of affairs, it will be perhaps, a long time before it will be settled so as to know who does own it. It is impossible for me to control it, but you had better keep posession of it at present. I cannot send Edwin [??] through to cultivate the land & take care of it. He will be of age in the spring, and if he were to go there I must hire him. He will probably leave us in the spring. Please give my best regards to all. Write me often.

Yours truly

S. Hall

Crow-wing, Min. Ter.

Feb. 21st 1854

Brother Wheeler,

Paul Hudon Beaulieu

~ FamilySearch.org

I wrote you a few days ago, and at the same time I wrote to Mr. Oakes inquiring whether he had got possession of the Lapointe property. I have not yet got a reply from him, but Mr. Beaulieu tells me that he heard the same report which you mentioned in your letter, and that he inquired of Mr. Oakes about it when he saw him on a recent visit to St. Paul, and finds that it is all a humbug. Oakes has nothing to do with it. Mr. Beaulieu said that the sale of last spring has been confirmed, and that Austrian will hold Lapointe. So farewell to all the inhabitants’ claims then, and to anything being done for the prosperity of the peace for the present, unless it gets out of his hands.

I have written to Austrian to try to get something for our property if we can. But I fear there is not much hope. If he goes back to Lapointe in the spring, do the best you can to make him give us something. I feel sorry for the inhabitants there that they are left at his mercy. He may treat them fairly, but it is hardly to be expected.

Clement Hudon Beaulieu

~ TreatiesMatter.org

As to our affairs here, there has been no particular change in their aspects since I wrote a few days ago. There must be a crisis, I think, in a few weeks. We must either go on or break up, I think, in the spring. We are trying to get a decision. I understand our agent has been threatened with removal if he carries on as he has done. I believe there is no hope of reformation in his case, and we may get rid of him. Perhaps God sent us here to have some influence in some such matters, so intimately connected with the welfare of the Indians. I have never thought I [????] can before I was sent in deciding to come here. Some trials and disappointments have grown out of my coming, but I feel conscious of having acted in accordance with my convictions of duty at this time.

If all falls through, I know not what to do in the future. The Home Missionary Society have got more on their hands now than they have funds to pay, if I were disposed to offer myself to labor under them. I may be obliged to build me a shanty somewhere on some little unoccupied piece of land and try to dig out a living. In these matters the Lord will direct by his providence.

You must be on your guard or some body will trip you up and get away your place. There are enough unprincipled fellows who would take all your improvements and send you and all the Indians into the Lake if they could make a dollar by it. I should not enlarge much, without getting a legal claim to the land. Neither would I advise you to carry on more family than is necessary to keep what team you must have, and to supply your family with milk and vegetables. It will be advantage/disadvantage to you in a pecuniary point of view, it will load you with and tend to make you worldly minded, and give your establishment the air of secularity in the eyes of the world. If I were to go back again to my old field, I would make my establishment as small as I could & have enough to live comfortable. I with others have thought that your tendency was rather towards going to largely into farming. I do not say these things because I wish to dictate or meddle with your affairs. Comparing views sometimes leads to new investigations in regard to duty.

May the Lord bless you and yours, and give you success and abundant prosperity in your labours of love and efforts to Save the Souls around you.

Give my best regards to Mrs. W., the children, Miss S and all.

Yours truly,

S. Hall

I forgot to say that we are all well. Henry and his family have enjoyed better health here, then they used to enjoy at Lapointe.

Feb 27

Brother Wheeler.

My delay to answer your note may require an explanation. I have not had time at command to attend to it conveniently at an earlier period. As to your first questions. I suppose there will be no difference of opinion between us as to the correctness of the following remarks.

- The Gospel requires the members of a church to exercise a spirit of love, meekness and forbearance towards an offending brother. They are not to use unnecessary severity in calling him to account for his errors. Ga. 6:1.

- The Object of Church discipline is, not only to [pursue/preserve?] the Church pure in doctrine & morals, that the contrary part may have no evil thing to say of them; but also to bring the offender to a right State of mind, with regard this offense, and gain him back to duty and fidelity.

- If prejudice exist in the mind of the offender towards his brethren for any reason, the spirit of the gospel requires that he be so approached if possible as to allay that prejudice, otherwise we can hardly expect to gain a candid hearing with him.

Charles William Wulff Borup, M.D. ~ Minnesota Historical Society

I consider that these remarks have some bearing on the case before us. If it was our object to gain over Dr. B. to our views of the Sabbath, and bring him to a right State of mind with regard this Sabbath breaking, the manner of approaching him would have, in my view, much to do with the offence. He may be approached in a Kind and [forbearing?] manner, when one of sternness and dictation will only repel him from you. I think we ought, if possible, and do our duty, avoid a personal quarrel with him. To have brought the subject before the Church & made a public affair of it, before [this/then?] and more private means have been tried to get satisfaction, would, I am sure, have resulted in this. I found from my own interviews with him, that there was hope, if the rest of the brethren would pursue a similar course. I felt pretty sure they would obtain satisfaction. IF they had [commenced?] by a public prosecution before the church, it would only have made trouble without doing any good. The peace of our whole community would have been disturbed. I thought one step was gained when I conversed with him, and another when you met him on the subject. I knew also that prejudices existed both in his mind towards us, & in our minds towards him which were likely to affect the settlement of this affair, and which as I thought, would be much allayed by individuals going to him and speaking face to face on this subject in private. He evidently expected they would do so. Mutual conversations and explanations allay these feelings very much. At least it has been so in my experience.

As to your second question. I do not say that it was Mr. Ely’s duty to open the subject to Doc. Borup at the preparatory lecture. If he had done so, it would have been only a private interview; for there [was?] not enough present to transact business. All I meant to affirm respecting that occasion is, that it afforded a good opportunity to do so, if he wishes, and that Dr. B. expected he would have done so, as I afterwards learnt, if he has any objection to make against his coming to the communion.

As to your third question. I have no complaint to make of the church, that I have urged them to the performance of any “duties“ in this case they have refused to perform.

And now permit me to ask in my turn.

What “duties” have they urged me to perform in this case, which I “have been unwilling, or manifested a reluctance to perform?”

Did you intend by anything which wrote to me or said verbally, to request me to commence a public prosecution of Doc. Borup before the Church?

Will you have the goodness to state in writing, the substance of what you said to me in your study as to your opinion and that of others suspecting my delinquency in maintaining church discipline.

A reply to these questions would be gratefully received.

Your brother in Christ

S. Hall

Crow Wing. March 12th 1854

Brother Wheeler:

Your letter of Feb 17th came to hand by our last mail; and though I wrote you but a short time ago, I will say a few words in relation to one or two topics to which you allude. Shortly after I received your former letter I wrote to Mr. Oakes enquiring about the property at Lapointe. In reply, says that himself and some others purchased Mr. Austrian’s rights at Lapointe of Old Hughes on the strength of a power of attorney which he held. Austrian asserts the power of attorney to be fraudulent, and that they cannot hold the property. Oakes writes as if he did not expect to hold it. Some time ago I wrote to Mr. Austrian on the same subject, and said to him that if I could get our old place back, I might go back to Lapointe. He says in reply —

Julius Austrian

~ Madeline Island Museum

“I should feel much gratified to see you back at Lapointe again, and can hold out to you the same inducements and assurances as I have done to all other inhabitants, that is, I shall be at Lapointe early in the spring and will have my land surveyed and laid out into lots, and then I shall be ready to give to every one a deed for the lot he inhabits, at a reasonable price, not paying me a great deal more than cost trouble, and time. But with you, my dear Sir, will be no trouble, as I have always known you a just and upright man, and have provided ways to be kind towards us, therefore take my assurance that I will congratulate myself to see you back again; and it shall not be my fault if you do not come. If you come to Lapointe, at our personal interview, we will arrange the matter no doubt satisfactory.”

“The property” from the James Hughes Affair is outlined in red. This encompassed the Church at La Pointe (New Fort) and the Mission (Middleport) of Madeline Island. 1852 PLSS survey map by General Land Office.

I suppose Austrian will hold the property and probably we shall never realize anything for our improvements. You must do the best you can. Make your appeal to his honor, if he has any. It will avail nothing to reproach him with his dishonesty. I do not know what more I can do to save anything, or for any others whose property is in like circumstances with ours.

You speak discouragingly of my going back to Lapointe. I do not think the Home Miss. Soc. would send a missionary there only for the few he could reach in the English language. If the people want a Methodist, encourage them to get one. It is painful to me to see the place abandoned to irreligion and vices of every Kind, and the labours I have expended there thrown away. I can hardly feel that it was right to give up the station when we did. If I thought I could support myself there by working one half the time and devoting the rest to ministerial labors for the good of those I still love there, I should still be willing to go back, if could get there & had a shelter for my head, unless there is a prospect of being more useful here. But the land at Lapointe is so hard to subdue that I am discouraged about making an attempt to get a living there by farming. I am not much of a fisherman. There is some prospect that we may be allowed to go on here. Mr. Treat has been to Washington, and says he expects soon to get a decision from the Department. We have got our school farm plowed, and the materials are drawn out of the woods for fencing it. If I have no orders to the contrary, I intend to go on & plant a part of it, enough to raise some potatoes. We may yet get our school established. If we can go ahead, I shall remain here, but if not, I think it is not my duty to remain here another year, as I have the past. In other circumstances, I could do more towards supporting myself and do more good probably.

I have felt much concerned for the people of Lapointe and Bad River on account of the small pox. May the Lord stay this calamity from spreading among you. Write us every mail and tell us all. It is now posted here today that the Old Chief [Kibishkinzhugon?] is dead. I hardly credit the report, though I should suppose he might be one of the first victims of the disease.

I can write no more now. We are all very well now. Give my love to all your family and all others.

Tell Robert how the matters stands about the land. It stands him in how to be on good terms with the Jew just now.

Yours truly,

S. Hall

The snow is nearly all off the ground and the weather for two or three weeks has been as mild as April.

Crow Wing M.H. Apr. 1 1854

Dear Br. & Sr. Wheeler.

I have received a letter from you since I wrote to you & am therfore in your debt in that matter. I have also read your letters to Br. & Sr. Welton I suppose you have received my letter of the 13th of Feb. if so, you have some idea of our situation & I need say no more of that now; & will only say that we are all well as usual & have been during the winter. Mrs. P_ is considerably troubled with her old spinal difficulty. She has got over her labors here last summer * fall. Harriet is not well I fear never will be, because the necessary means are not likely to be used, she has more or less pain in her back & side all the time, but she works on as usual & appears just as she did at LaPointe, if she could be freed from work so as to do no more than she could without injury & pursue uninterruptedly & proper medical course I think she might regain pretty good health. (Do not, any of you, send back these remarks it would not be pleasing to her or the family.) We have said what we think it best to say) –

Br. Hall is pretty well but by no means the vigorous man he once was. He has a slight – hacking cough which I suppose neither he nor his family have hardly noticed, but Mrs. P_ says she does not like the sound of it. His side troubles him some especially when he is a good deal confined at writing. Mr. & Mrs. W_ are in usual health. Henry’s family have gone to the bush. They are all quite well. He stays here to assist br. H_ in the revision & keeps one or two of his children with him. They are now in Hebrews, with the Revision. Henry I suppose still intends to return to Lapointe in the spring. –

Now, you ask, in br. Welton’s letter, “are you all going to break up there in the spring.” Not that I know of. It would seem to me like running away rather prematurely. When the question is settled, that we can do nothing here, then I am willing to leave, & it may be so decided, but it is not yet. We have not had a whisper from Govt. yet. Wherefore I cannot say.

It looks now as if we must stay this season if no longer. Dr. Borup writes to br. Hall to keep up good courage, that all will come out right by & by, that he is getting into favor with Gov. Gorman & will do all he can to help us. (Br. Hall’s custom is worth something you know).

Henry C. Gilbert

~ Branch County Photographs

By advise of the Agent, we got out (last month) tamarack rails enough to fence the school farm (which was broke last summer) of some 80 acres & it will be put up immediately. Our great father turned out the money to pay for the job. These things look some like our staying awhile I tell br H_ I think we had better go as far as we can, without incurring expense to the Board (except for our support) & thus show our readiness to do what we can. if we should quit here I do not know what will be done with us. Br Hall would expect to have the service of the Board I suppose. Should they wish us to return to Bad River we should not say nay. We were much pleased with what we have heard of your last fall’s payment & I am as much gratified with the report of Mr. H. C. Gilbert which I have read in the Annual Report of the Com. of Indian Affairs. He recommends that the Lake Superior Indians be included in his Agency, that they be allowed to remain where they are & their farmers, blacksmith & carpenter be restored to them. If they come under his influence you may expect to be aided in your efforts, not thwarted , by his influence. I rejoice with you in your brightening prospects, in your increased school (day & Sabbath) & the increased inclination to industry in those around you. May the lord add his blessing, not only upon the Indians but upon your own souls & your children, then will your prosperity be permanent & real. Do not despise the day of small things, nor overlook especially neglect your own children in any respect. Suffer them not to form idle habits, teach them to be self reliant, to help themselves & especially you, they can as well do it as not & better too, according to their ability & strength, not beyond it, to fear God & keep his commandments & to be kind to one another (Pardon me these words, I every day see the necessity of what I have said.) We sympathize with you in your situation being alone as you are, but remember you have one friend always near who waits to [commence?] with you, tell Him & all with you from Abby clear down to Freddy.

Affectionately yours

C. Pulsifer

Write when you can.

Crow wing Min. Ter.

April 3d 1854

Brother Wheeler

George E. Nettleton and his brother William Nettleton were pioneers, merchants, and land speculators at what is now Duluth and Superior.

~ Image from The Eye of the North-west: First Annual Report of the Statition of Superior, Wisconsin by Frank Abial Flower, 1890, page 75.

Since I wrote you a few days ago, I have received a letter from Mr. G. E. Nettleton, in which he says, that when he was at Lapointe in December last, he was very much hurried and did not make a full settlement with Antoine. He says further, that he showed him my account, and told him I had settled with him, and that he would see the matter right with Antoine. A. replied that all was right. I presume therefore all will be made satisfactory when Mr. N. comes up in the Spring, and that you will have need to make yourself no further trouble about this matter.

I have also received a short note from Mr. Treat in which he says,

“I have not replied to your letters, because I have been daily expecting something decisive from Washington. When I was there, I had the promise of immediate action; but I have not heard a word from them”.

“I go to Washington this Feb, once more. I shall endeavor to close up the whole business before I return. I intend to wait till I get a decision. I shall propose to the Department to give up the school, if they will indemnify us. If I can get only a part of what we lose, I shall probably quit the concern”.

Thus our business with the Government stood on March the 9th, I have lost all confidence in the Indian Department of our Government under this administration, to say nothing of the rest of it. If the way they have treated us is an index to their general management, I do not think they stand very high for moral honesty. The prospects for the Indians throughout all our territories look dark in the extreme. The measures of the Government in relation to them are not such as will benefit and save many of them. They are opening the floodgates of vice and destruction upon them in every quarter. The most solemn guarantees that they shall be let alone in the possession of domains expressly granted them mean nothing.

Our prospects here look dark. For some time past I have been rather anticipating that we should soon get loose and be able to go on. But all is thrown into the dark again. What I am to do in future to support my family, I do not know. If we are ordered to quit here and turn over the property, it would turn [illegible] out of doors.

Mr. Austrian expects us back to Lapointe in the Spring & Mr. Nettleton proposes to us to go to Fond du Lac, (at the Entry). He says there will be a large settlement then next season. A company is chartered to build a railroad through from the Southern boundary of this territory to that place. It is probable that Company [illegible] will make a grant of land for that purpose. If so, it will probably be done in a few years. That will open the lake region effectually. I feel the need of relaxation and rest before I do anything to get established anywhere.

We are still working away at the Testament, it is hard work, and we make lately but slow progress. There is a prospect that the Bible Society will publish it but it is not fully decided. I wish I could be so situated that I could finish the grammar.

But I suppose I am repeating what I have said more than once before. We are generally in good health and spirits. We hope to hear from by next mail.

Yours truly

S. Hall

What do you think about the settlements above Lapointe and above the head of the Lake?

Detroit July 10th 1854

Rev. Dr. Bro.

At your request and in fulfilment of my promise made at LaPointe last fall so after so long a time I write: And besides “to do good & to communicate” as saith the Apostle “forget not, for with such sacrifices God is well pleased.”

We did not close up our Indian payments of last year until the middle of the following January, the labors, exposures and excitements of which proved too much for me and I went home to New York sick & nearly used up about the last of February & continued so for two months. I returned here about a week ago & am now preparing for the fall pay’ts.

The Com’sr. has sent in the usual amounts of Goods for the LaPointe Indians to Mr. Gilbert & I presume means to require him to make the payment at La P. that he did last fall, although we have received nothing from the Dep’t. on the subject.

“George Washington Manypenny (1808-1892) was the Director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs of the United States from 1853 to 1857.”

~ Wikipedia.org

In regard to the Treaty with the Chipp’s of La Sup’r & the Miss’i, the subject is still before Congress and if one is made this fall it has been more than intimated that Com’r Manypenny will make it himself, either at LaP’ or at F. Dodge or perhaps at some place farther west. Of course I do not speak from authority or any of the points mentioned above, for all is rumour & inference beyond the mere arrival here of the Goods to Mr G’s care.

From various sources I learn that you have passed a severe winter and that much sickness has been among the Indians and that many of them have been taken away by the Small Pox.

This is sad and painful intelligence enough and I can but pray God to bless & overrule all to the goods of his creasures and especially to the Missionaries & their families.

Notwithstanding I have not written before be assured that I have often [???] of and prayed for you and yours and while in [Penn.?] you made your case my own so far as to represent it to several of our Christian brethren and the friends of missions there and who being actuated by the benevolent principles of the Gospel, have sent you some substanted relief and they promise to do more.

The Elements of the political world both here and over the waters seem to be in fearful & [?????] commotion and what will come of it all none but the high & holy one can know. The anti Slavery Excitement with us at the North and the Slavery excitement at the South is augmenting fact and we I doubt not will soon be called upon to choose between Slavery & freedom.

If I do not greatly misjudge the blessed cause of our holy religion is or seems to be on the wane. I trust I am mistaken, but the Spirit of averice, pride, sensuality & which every where prevails makes me think otherwise. The blessed Christ will reign [recenth-den?] and his kingdom will yet over all prevail; and so may it be.

Let us present to him daily the homage of a devout & grateful heart for his tender mercies [tousward?] and see to it that by his grace we endure unto the end that we may be saved.

My best regards to Mrs. W. to Miss Spooner to each of the dear children and to all the friends & natives to each of whom I desire to be remembered as opportunity occurs.

The good Lord willing I may see you again this fall. If I do not, nor never see you again in this world, I trust I shall see and meet you in that world of pure delight where saints immortal reign.

May God bless you & yours always & ever

I am your brother

In faith Hope & Charity

Rich. M. Smith

Rev Leonard H. Wheeler

LaPointe

Lake Superior

Miss. House Boston

Augt’ 31, 1854

Rev. L. H. Wheeler,

Lake Superior

Dear Brother

Yours of July 31 I laid before the Com’sr at our last meeting. They have formally authorized the transfer of Mr & Mrs Pulsifer to the Lake, & also that of Henry Blatchford.

Robert Stuart was formerly an American Fur Company agent and Acting Superintendent on Mackinac Island during the first Treaty at La Pointe in 1842.

~ Wikipedia.org

In regard to the “claims” their feeling is that if the Govt’ will give land to your station, they have nothing to say as to the quantity. But if they are to pay the usual govt’ price, the question requires a little caution. We are clear that we may authorize you to enter & [???] take up so much land as shall be necessary for the convenience of the [mission?] families; but we do not see how we can buy land for the Indians. Will you have the [fondness?] to [????] [????] on these points. How much land do you propose to take up in all? How much is necessary for the convenience of the mission families?

Perhaps you & others propose to take up the lands with private funds. With that we have nothing to do, so long as you, Mr P. & H. do not become land speculators; of which, I presume, there is no danger.

As to the La Pointe property, Mr Stuart wrote you some since, as you know already I doubt not, and replied adversely to making any bargain with Austrian. I took up the opinion of the Com’sr after receiving your letter of July 31, & they think it the wise course. I hope Mr Stewart will get this matter in some shape in due time.

I will write to him in reference to the Bad River land, asking him to see it once if the gov’ will do any thing.

Affectionate regards to Mrs W. & Miss Spooner & all.

Fraternally Yours

S. B. Treat

P.S. Your report of July 31 came safely to hand, as you will & have seen from the Herald.

The Woman In Stone

March 15, 2016

By Amorin Mello & Leo Filipczak

Photograph of the Wheeler and Wood Families from the Wheeler Family Papers at the Wisconsin Historical Society. The woman dressed in white is Harriet Martha Wheeler, according to the book about her mother, Woman in the Wilderness: Letters of Harriet Wood Wheeler, Missonary Wife, 1832-1892, by Nancy Bunge, 2010.

![Leonard Hemenway Wheeler ~ Unnamed Wisconsin by [????]](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/leonard-hemenway-wheeler-from-unnamed-wisconsin.jpg?w=237&h=300)

Leonard Hemenway Wheeler: husband of Harriet Wood Wheeler, and father of author Harriet Martha Wheeler.

~ Unnamed Wisconsin, by John Nelson Davidson, 1895.

Harriet Wood Wheeler: wife of Leonard Wheeler, and mother of author Harriet Martha Wheeler.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

This is a reproduction of the final chapter from Harriet Martha Wheeler’s 1903 book, The Woman in Stone: A Novel. If you want to read the entire novel without spoiling the final chapter featured here, you can download it here as a PDF file: The Woman in Stone: A Novel. Special thanks to Paul DeMain at Indian Country Today Media Network for making the digitization of this novel possible for the public to read with convenience.

“Hattie” was named after her mother, Harriet Wood Wheeler; the wife of Reverend Leonard Hemenway Wheeler. Hattie was born in 1858 at Odanah, shortly after the events portrayed in her novel. Hattie’s experiences and writings about the Lake Superior Chippewa are summarized in an academic article by Nancy Bunge, published in The American Transcendental Quarterly , Vol. 16, No. 1 , March 2002: Straddling Cultures: Harriet Wheeler’s and William W. Warren’s Renditions of Ojibwe History

William Whipple Warren (c. 1851)

~ Wikimedia.org

“Mary Warren English, White Earth, Minnesota”

~ University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library, NEMHC Collections

Harriet Wheeler and William W. Warren not only both lived on Ojibwe reservations in northern Wisconsin during the nineteenth century, but their families had strong bonds between them. William Warren’s sister, Mary Warren English, writes that her brother returned to La Pointe, Wisconsin, from school on the same boat Harriet’s parents took to begin their mission work. The Wheelers liked him and appreciated his help: “He won a warm and life-long friendship–with these most estimable people–by his genial and happy disposition–and ever ready and kindly assistance–during their long and tedious voyage” (Warren Papers). When Mary Warren English’s parents died, she moved in with the Wheelers, and, long after she and Harriet no longer shared the same household, she began letters to Harriet with the salutation, “Dear Sister.” But William Warren’s History of the Ojibwe People (1885) and Harriet Wheeler’s novel The Woman in Stone (1903) reveal that this shared background could not overcome the cultural differences between them. Even though Wheeler and Warren often describe the same events and people, their accounts have different implications. Wheeler, the daughter of Congregational missionaries from New England, portrays the inevitable and necessary decline of the Ojibwe, as emissaries of Christianity help civilization progress; Warren, who had French and Ojibwe ancestors, as well as Yankee roots, identifies growing Anglo-Saxon influence on the Ojibwe as a cause of moral decay.

Hattie’s book appears to provide some valuable insights about certain events in Chequamegon history, yet it is clearly erroneous about other such events. According to the University of Wisconsin – Madison, Harriet’s novel is “based on discovery of petrified body of Indian woman in northern Wisconsin.” This statement seems to acknowledge this peculiar event as being somewhat factual. However, Hattie’s novel is clearly a work of fiction; it appears that some of her references were to actual events. At this point in time, this mystery of the forest may never be thoroughly confirmed or debunked.

An incomplete theater screenplay, with the title “Woman in Stone,” was also written by Hattie. It appears to be based on her novel, can be found at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center Archives, in the Wheeler Family Papers: Northland Mss 14; Box 10; Folder 19. However, only several pages of this screenplay copy still exist in the archive there. A complete copy of Hattie’s screenplay may still exist somewhere else yet.

The Woman in Stone: A Novel by Harriet Martha Wheeler, 1903.

[Due to the inconsistencies found in Hattie’s novel, we have omitted most of this novel for this reproduction. We shall skip to the final chapter of Hattie’s novel, to the rediscovery of long lost “Wa-be-goon-a-quace,” the Little Flower Girl. If you want to read the entire novel first, before spoiling this final chapter, you can download it here: The Woman in Stone: A Novel, by Harriet Wheeler, 1903. Special thanks to Paul DeMain at Indian Country Today Media Network for making the digitization of this novel possible for the public to read with convenience.]

(Pages 164-168)

CHAPTER XX.

THE DISCOVERY OF THE WOMAN IN STONE

A hundred years swept over the island Madelaine, bringing change and decay in their train. But, nature renews the waste of time with a prodigal hand and robed the island in verdant loveliness.

Madelaine still towers the queen of the Apostle group, with rocky dells and pine clad shores and odorous forests, through which murmur the breezes from the great lake, and over all hover centuries of history, romance, and legendary lore.

Jean Michel Cadotte was Madelaine’s father-in-law, not husband. Madelaine Cadotte’s Ojibwe name was Ikwezewe, and she was still alive at La Pointe, in her ’90s, during Hattie‘s childhood in Odanah. It’s kind of disturbing how little of this Hattie got right considering Mary Warren (Madeline’s granddaughter) was basically Hattie’s stepsister.

Evolution toward the spiritual is the destiny of humanity and in this trend of progress the Red Men are vanishing before the onward march of the Pale Face. In the place of the blazing Sacred Fire stands the Protestant Mission. The settlers’ cabin supplants the wigwam. No longer are heard the voyageur’s song and the rippling canoes. This is the age of steam, and far and near echoes the shrill whistle. Overgrown mounds mark the sites of the forts of La Ronde and Cadotte. In the spacious log cabin of Jean and Madelaine Cadotte lives their grandson, John Cadotte.

“Dirt trail passing log shack that was probably the home of Michael and Madeline Cadotte, La Pointe,” circa 1897.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

A practical man is John. He tills his garden, strings his fish-net in the bay, and acts as guide, philosopher and friend for all the tourists who visit the island.

Hildreth Huntington and his father may have been fictionalized, or they may be actual people from the Huntington clan:

by the Huntington Family Association, 1915.

On a June morning of the year 1857, John sat beneath a sheltering pine mending his fish-net. he smoked a cob-pipe, which he occasionally laid by to whistle a voyageur’s song. A shrill whistle sounded and a tug steamed around the bend to the wharf. John laid aside his fish-net and pipe and strolled to the beach. Two gentlemen, clad in tourist’s costume, stepped from the tug and approached John.

“Can you direct us to Mr. John Cadotte?” said the elder man.

“I am your man,” responded John.

Augustus Hamilton Barber had copper and land claims around the Montreal and Tyler Forks Rivers before his death in 1856. It is possible that this father and son pair in Hattie’s novel actually represent Joel Allen Barber and his father, Giles Addison Barber. They were following up on their belated Augustus’ unresolved business in this area during June of 1857. This theory about the Barber family is explored in more details with “Legend of the Montreal River,” by George Francis Thomas.

“My name is Huntington. This young man is my son, Hildreth. We came from New York, and are anxious to explore the region about Tyler’s fork where copper has been discovered. We were directed to you as a guide on whom we might depend. Can we secure your services, sir?” asked the stranger.

“It is also proper to state in addition to what has been already mentioned, that at, or about this time [1857], a road was opened by Mr. Herbert’s order, from the Hay Marsh, six miles out from Ironton, to which point one had been previously opened, to the Range [on the Tyler Forks River], which it struck about midway between Sidebotham’s and Lockwood’s Stations, over which, I suppose, the 50,000 tons as previously mentioned, was to find its way to Ironton, (in a horn).“

~ Penokee Survey Incidents: IV

“I am always open to engagement,” responded John.

“Very well, we will start at once, if agreeable to you.”

“I will run up to the house and pack my traps,” said John.

The stranger strolled along the beach until John’s return. Then all aboard the tug and steamed away towards Ashland. John entertained the strangers with stories and legends of those romantic and adventurous days which were fading into history.

“The company not being satisfied with Mr. Herbert as agent, he was removed and Gen. Cutler appointed in his place, who quickly selected Ashland as headquarters, to which place all the personal property, consisting of merchandise principally, was removed during the summer by myself upon Gen. C.’s order – and Ironton abandoned to its fate.”

~ Penokee Survey Incidents: I

The party left the tug at Ashland and engaged a logger’s team to carry them to Tyler’s Forks, twenty miles away. A rough road had been cut through the forest where once ran an Indian trail. Over this road the horses slowly made their way. Night lowered before they had reached their destination and they pitched their tents in the forest. John kindled a camp-fire and prepared supper. The others gathered wood and arranged bough beds in the tent. They were wearied with the long and tedious journey and early sought this rude couch.

John’s strident tones summoned them to a sunrise breakfast. They broke camp and resumed their journey, arriving at the Forks at noon.

The tourists sat down on the banks of the river and viewed the beautiful falls before them.

“This is the most picturesque spot I have seen, Hildreth. It surpasses Niagara, to my mind,” said Mr. Huntington.

The preface to this novel is a photograph of Brownstone Falls, where the Tyler Forks River empties into the Bad River at Copper Falls State Park. George Francis Thomas’ “A Mystery of the Forest” was originally published as “Legend of the Montreal River“ (and republished here). It suggests that the legend takes place at the Gorge on the Tyler Forks River, where it crosses the Iron Range; not where it terminates on Bad River along the Copper Range.

They gazed about them in wondering admiration. The forest primeval towered above them. Beyond, the falls rolled over their rocky bed. The ceaseless murmur of the rapids sounded below them and over all floated the odors of the pines and balsam firs.

“This description will, I think, give your readers a very good understanding of the condition as well as the true inwardness of the affairs of the Wisconsin & Lake Superior Mining and Smelting Co., in the month of June, 1857.”

[…]

“Rome was not built in a day, but most of these cabins were. I built four myself near the Gorge [on Tyler Forks River], in a day, with the assistance of two halfbreeds, but was not able to find them a week afterwards. This is not only a mystery but a conundrum. I thinksome traveling showman must have stolen them; but although they werenon est we could swear that we had built them, and did.“

~ Penokee Survey Incidents: IV

After dinner the party began their explorations under John’s leadership. Two days were spent in examining the banks of Bad River. On the third morning they came to the gorge. Here, the river narrowed to a few feet and cut its way through high banks of rock. The party examined the rocks on both sides. John climbed to the pool behind the gorge and examined the rocks lying beneath the shallow water. He rested his hand on what seemed to be a water-soaked log and was surprised to find the log a solid block of stone. He examined it carefully. The stone resembled a human form.

“Mr. Huntington, come down here,” he called.

“Have you struck a claim, John?” asked Mr. Huntington.

“Not exactly. Look at this rock. What do you call it, sir?”

Mr. Huntington, his son and the teamster climbed down to the pool and examined the rock.

“A petrification of some sort,” exclaimed Mr. Huntington. “Let us lift it from the water.”

The men struggled some time before they succeeded in raising the solid mass. They rested it against the rocky bank.

Wabigance: Little Flower Girl

Hattie identified this character as “Wa-be-goon-a-quace.” In the Ojibwemowin language, Wabigance is a small flower. Wabigon or Wabegoon is a flower. Wabegoonakwe is a flower that is female.

“A petrified Indian girl,” exclaimed Mr. Huntington.

The men bent low over the strange figure, examining it carefully.

“Look at her moccasins, father,” exclaimed Hildreth, “and her long hair. Here is a rosary and cross about her neck. Evidently she was a good Catholic.”

“Holy Mother,” exclaimed John, “it is the Little Flower Girl.”“And who was she?” asked Mr. Huntington.

“She was my grandmother Madelaine’s cousin. I have heard my grandmother tell about her many times when I was a boy. The Little Flower Girl lost her mind when her pale-faced lover died in battle. She was always hunting for him in the island woods. One evening she disappeared in her canoe and never returned.”

“How came she by this cross?”

“The Holy Father Marquette gave it to her grandmother, Ogonã. The Little Flower Girl wore it always. She thought it protected her from evil and would lead her to her lover, Claude.”

And so it has. The cross has led the Little Flower Girl up yonder where she has found her Claude and life immortal.

“A touching romance, worthy to be embalmed in stone,” said Hildreth.

“Barnum’s Museum Fire, New York City, 1868 Incredible view of the frozen ruins of Barnum’s ‘American Museum’ just after the March, 1868 fire. 3-1/4×6-3/4″ yellow-mount view published by E & HT Anthony; #5971 in their series of ‘Anthony’s Stereoscopic Views.’ Huge ice formations where the water sprays hit the building; burned out windows and doors.”

~ CraigCamera.com

“Yes, and worthy of a better resting place,” responded Mr. Huntington. “We must take the Little Flower Girl with us, Hildreth. Her life belongs to the public. Our great city will be better for this monument of her romantic, tragic, sorrowing life.”

Over the forest road, where her moccasined feet had strayed one hundred years before, they bore the Little Flower Girl. And the eyes of the Holy Father shone on her as she crossed the silvery water where her “Ave Maria” echoed long ago. Back to the island Madelaine they carried her, and on, down the great lakes, the Little Flower Girl followed in the wake of her lover, Claude. To the great city of New York they bore her. In one of that great city’s museum rests the Woman in Stone.

Leonard Wheeler Obituary

May 31, 2014

Rev. Leonard Hemenway Wheeler 1811-1872 (Photo: In Unnamed Wisconsin)

Bob Nelson recently contacted me with a treasure he transcribed from an 1872 copy of the Bayfield Press. For those who don’t know, Mr. Nelson is one of the top amateur historians in the Chequamegon area. He is on the board of the Bayfield Heritage Association, chairman of the Apostle Islands Historic Preservation Conservancy, and has extensively researched the history of Bayfield and the surrounding area.

The document itself is the obituary of Leonard Wheeler, the Congregational-Presbyterian minister who came to La Pointe as a missionary in 1841. Over the next quarter-century, spent mostly at Odanah where he founded the Protestant Mission, he found himself in the middle of the rapid social and political changes occurring in this area.

Generally, my impression of the missionaries has always tended to be negative. While we should always judge historical figures in the context of the times they lived in, to me there is something inherently arrogant and wrong with going among an unfamiliar culture and telling people their most-sacred beliefs are wrong. The Protestant missionaries, especially, who tended to demand conversion to white-American values along with conversion to Christianity, generally come off as especially hateful and racist in their writings on the Ojibwe and mix-blooded families of this area.

Leonard Wheeler, however, is one of my historical heroes. It’s true that he was like his colleagues Sherman Hall, William T. Boutwell, and Edmund Ely, in believing that practitioners of the Midewiwin and Catholicism were doomed to a fiery hell. He also believed in the superiority of white culture and education. However, in his writings, these beliefs don’t seem to diminish his acceptance of his Ojibwe neighbors as fellow human beings. This is something that isn’t always clear in the writings of the other missionaries.

Furthermore, Wheeler is someone who more than once stood up for justice and against corruption even when it brought him powerful enemies and endangered his health and safety. For this, he earned the friendship of some of the staunchest traditionalists among the Bad River leadership. He relocated to Beloit by the end of his life, but I am sure that Wheeler’s death in 1872 brought great sadness to many of the older residents of the Chequamegon Bay region and would have been seen as a significant event.

Therefore, I am very thankful to Bob Nelson for the opportunity to present this important document:

Reverend Leonard H. Wheeler

Missionary to the Ojibway

From the Beloit Free Press

Entered in the Bayfield Press

March 23, 1872

The recent death of Reverend Leonard H. Wheeler, for twenty-five years missionary to the Ojibway Indians on Lake Superior and for the last five and one half years a resident of Beloit, Wisconsin and known to many through his church and business relations, seems to call for some notice of his life and character through your paper.

Mr. Wheeler was born at Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, April 13, 1811. His mother dying during his infancy, he was left in charge of an aunt who with his father soon afterward removed to Bridgeport, Vermont, where the father still lives. At the age 17 he went first from home to reside with an uncle at Middlebury, Vermont. Here he was converted into the church in advance of both his father and uncle. His conversion was of so marked a character and was the occasion of such an awakening and putting forth of his mental and spiritual facilities that he and his friends soon began to think of the ministry as an appropriate calling. With this in view he entered Middlebury College in 1832, and soon found a home in the family of a Christian lady with whom he continued to reside until his graduation. For the kindly and elevating influences of that home and for the love that followed him afterwards, as if he had been a son, he was ever grateful. After his graduation he taught for a year or two before entering the theological seminary at Andover.

During his theological course the marked traits of character were developed which seem to have determined his future course. One was a deep sympathy with the wronged and oppressed; the other was conscious carefulness in settling his convictions and an un-calculating and unswerving firmness (under a gentle and quiet manner) in following such ripened convictions. These made him a staunch but a fanatical advocate of the enslaved, long before anti-slavery sentiments became popular. And thus was he moved to offer his services as a missionary to the Indians – relinquishing for that purpose his original plan to go on a mission to Ceylon. The turning point of his decision seems to have been the fact that for the service abroad men could readily be found, while few or none offer themselves to the more self-denying and unromantic business of civilizing and Christianizing the wild men within our own borders.

Harriet Wood Wheeler much later in life (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Reverend Wheeler found in Ms. Harriet Woods, of Lowell, Massachusetts, the spirit kindred with his own in these self-denying purposes and labors of love. There married on April 26, 1841, and June of that year they set out, and in August arrived at La Pointe – a fur trading post on Madeline Island in Lake Superior. They spent four years in learning the Ojibway language, in preaching and teaching, and in caring for the temporal and spiritual welfare of the Indians and half-breeds at that station. Their fur trading friends held out many inducements to remain at La Pointe but having become fully satisfied that the civilizing of the Indians required their removal to someplace where they might obtain lands and homes of their own; the Wheelers secured their removal to Odanah on the Bad River. Here the humble and slowly rewarded labors of the island were renewed with increased energy and hopefulness, and continued without serious interruption for seven years. Then, the white man’s greed, which has often dictated the policy of the government toward the Indians, and oftener defeated its wise and liberal intentions, clamored for their second removal to the Red Lake region, in Minnesota, and by forged petitions and misrepresentation, an order to this effect was obtained.

Mr. Wheeler’s spirit was stirred within him by these iniquitous proceedings, and he set himself calmly but resolutely to work to defeat the measure, even after it had been so far consummated. To make sure of his ground he explored the Red Lake region during the heat of midsummer. Becoming fully satisfied with the temptations to intemperance and other evil thereof, bonding would prove the room of this people. He made such strong and truthful representations of this matter (not without hazards to himself and his family) that the order was at last revoked. But the agitation and delays thus occasioned proved well nigh the ruin of the mission. For two years Mr. Wheeler without help from government, stood between his people and absolute starvation; and had at last the satisfaction of knowing that his course was fully approved. The year 1858 found the mission and Odanah almost prostrate again by unusual labors. Mrs. Wheeler was compelled by order of her physician to return to her eastern home for indispensable rest. Mr. Wheeler, worn by superintending the erection of buildings in addition to his preaching four times on the Sabbath and in other necessary cares and labors, also undertook a journey to the east to bring back his family and partly as a measure of relief to himself.

He started in March on snowshoes and traveled nearly 200 miles in that way. On his way he fell in with the band of Indians whose lands were about to be sold in violation of solemn treaties. He undertook their case and did not abandon it, yet visited Washington and obtained justice in their behalf. He reached Lowell, Massachusetts on his return from Washington, worn in body and mind, and with the severe cold firmly settled on his lungs. Trusting to an iron constitution to right it, he kept on preaching and visiting among his eastern friends. He then set out to return to his beloved people and his eastern home, trusting to find in a quiet journey by water the rest which had now become imperative. But he was not thus to be relieved. Soon after reaching home he was taken with violent hemorrhage and was ever after this a broken man.

Once again he asked to be relieved and a stronger man be sent in his place. But this was not done, and he continued to struggle on doing what he could until the fall of 1866, when the boarding school – which had been his right hand – was denied further support from the government. Mr. Wheeler’s strength not being equal to the task of obtaining for its support from other quarters, he retired from the mission, and he, with his family became residents of Beloit, and for these five years and more he has bravely battled with disease, and, for a sick man, has led a happy and withal useful life.

“ECLIPSE BELOIT:” Originally invented for the Odanah mission, Rev. Wheeler’s patent on the Eclipse Windmill brought wealth to his descendants (Wikimedia Images).

Mr. Wheeler had by nature something of that capacity for being self-reliant and patient, continuous thoughts which marks the inventor. Thrown upon his own resources for as much, and in need of a mill for grinding, he devised, while in his mission, a windmill for that purpose with improvements of his own. Unable to speak or preach as he was when he came among us, and incapacitated for continuous manual laborers, he busied himself with making drawings and a model of his previous invention. He obtained a patent, and with the aid of friends here began the manufacture of windmills. Thus has the sick man proved one of our most useful citizens, and established a business which we hope will do credit to his ingenuity and energy and be a source of substantial advantage to his family in the place.

Debilitated by the heat of last summer he took a journey to the east in September for his health, and to visit their aged parents. His health was for a time improved, but soon after his return hemorrhages began to appear, and after a long and trying sickness, borne with great cheerfulness and Christian resignation, he went to his rest on the Sabbath, February 25, 1872. During the delirium of his disease, and in his clear hours, his thoughts were much occupied with his former missionary cares and labors. Doing well to that people was evidently his ruling passion. It was a great joy in his last sickness to get news from there, to know that the boarding school had been revived and then some whom he had long worn upon his heart had become converts to Christ.

Thus has passed away one whose death will be severely limited by the people for whom he gave his life and whom he longed once more to visit. It will add not a little to the pleasure and richness of life’s recollections that we have known so true a fair and good a man. While we cherish his memory and follow his family with affectionate sympathy for his sake in their own, let us not overlook the simple faith, the utter integrity and soundness of soul which one for him such unbounded confidence from us and from all who knew him, and gave to his character so much gentleness blended with so much dignity and strength. He was an Israelite, indeed in who was no guile, a Nathaniel, given of God, prepared in a crystalline medium through which the light from heaven freely passed to gladden and to bless.

For more on Rev. Leonard Wheeler on this site, check out the People Index, or the Wheeler Papers category.

Leonard Wheeler’s original correspondence, journals, legal documents and manuscripts can be found in the Wheeler Family Papers at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center.

The book In Unnamed Wisconsin (1895) contains several incidents from Wheeler’s time at La Pointe and Odanah from the original writings of his widow, Harriet Wood Wheeler.

Finally, the article White Boy Grew Up Among the Chippewas from the Milwaukee Journal in 1931 is a nice companion to this obituary. The article, about Wheeler’s son William, sheds unique insight on what it was like to grow up as the child of a missionary. This article exists transcribed on the internet because of the efforts of Timm Severud, the outstanding amateur historian of the Barron County area. This is just one of many great stories uncovered by Mr. Severud, who passed away in 2010 at age 55.

Ishkigamizigedaa! Bad River Sugar Camps 1844

March 15, 2014

Indian Sugar Camp by Seth Eastman c.1850 (Minnesota Historical Society)

Since we’re into the middle of March 2014 and a couple of warm days have had people asking, “Is it too early to tap?” I thought it might be a good time to transcribe a document I’ve been hanging onto for a while.

170 years ago, that question would have been on everyone’s mind. The maple sugar season was perhaps the most joyous time of the year. The starving times of February and early March were on the way out, and food would be readily available again. Friends and relatives, separated during the winter hunts, might join back together in sugar camp, play music around the fire as the sap boiled, and catch up on the winter’s news.

Probably the only person around here who probably didn’t like the sugar season was the Rev. Sherman Hall. Hall, who ran the La Pointe mission and school, aimed to convert Madeline Island’s Native and non-Native inhabitants to Protestantism. To him, Christianity and “civilization” went hand and hand with hard labor and settling down in one place to farm the land. When, at this time of the year, all his students abandoned the Island with everyone else, for sugar camps at Bad River and elsewhere on the mainland and other islands, he saw it as an impediment to their progress as civilized Christians.

Rev. Leonard Wheeler, who joined Hall in 1841, shared many of his ethnocentric attitudes toward Ojibwe culture. However, over the next two decades Wheeler would show himself much more willing than Hall and other A.B.C.F.M. missionaries to meet Ojibwe people on their own cultural turf. It was Wheeler who ultimately relocated from La Pointe to Bad River, where most of the La Pointe Band now stayed, partly to avoid the missionaries, where he ultimately befriended some of the staunchest traditionalists among the Ojibwe leadership. And while he never came close to accepting the validity of Ojibwe religion and culture, he would go on to become a critical ally of the La Pointe Band during the Sandy Lake Tragedy and other attempted land grabs and broken Government promises of the 1850s and ’60s.

In 1844, however, Wheeler was still living on the island and still relatively new to the area. Coming from New England, he knew the process and language of making sugar–it’s remarkable how little the sugar-bush vocabulary has changed in the last 170 years–but he would see some unfamiliar practices as he followed the people of La Pointe to camp in Bad River. Although there is some condescending language in his written account, not all of his comparisons are unfavorable to his Ojibwe neighbors.

Of course, I may have a blind spot for Wheeler. Regular readers might not be surprised that I can identify with his scattered thoughts, run-on sentences, and irregular punctuation. Maybe for that reason, I thought this was a document that deserved to see the light of day. Enjoy:

Bad River Monday March 25, 1844

We are now comfortably quartered at the sugar camps, Myself, wife, son and Indian Boy. Here we have been just three weeks today.

I came myself the middle of the week previous and commenced building a log cabin to live in with the aid of two men , we succeeded in putting up a few logs and the week following our house was completed built of logs 12 by 18 feet long and 4 feet high in the walls, covered with cedar birch bark of most miserable quality so cracked as to let in the wind and rain in all parts of the roof. We lived in a lodge the first week till Saturday when we moved into our new house. Here we have, with the exception of a few very cold days, been quite comfortable. We brought some boards with us to make a floor–a part of this is covered with a piece of carpeting–we have a small cooking stove with which we have succeeded in warming our room very well. Our house we partitioned off putting the best of the bark over the best part we live in, the other part we use as a sort of storeroom and woodhouse.

We have had meetings during on the Sabbath and those who have been accustomed to meet with us have generally been present. We have had a public meeting in the foreroom at Roberts sugar bush lodge immediately after which my wife has had a meeting with the women or a sabbath school at our house. Thus far our people have seemed to keep up their interest in Religion.

They have thus far generally remembered the Sabbath and in this respect set a good example to their neighbors, who both (pagan) Indians and Catholics generally work upon the Sabbath as upon other days. If our being here can be the means of preventing these from declension in respect to religion and from falling into temptation, (especially) in respect to the Sabbath, an important end will be gained.

The sugar making season is a great temptation to them to break the sabbath. It is quite a test upon their faith to see their sap buckets running over with sap and they yet be restrained from gathering it out of respect to the sabbath, especially should their neighbors work in the same day. Yet they generally abstain from Labor on the Sabbath. In so doing however they are not often obliged to make much sacrifice. By gathering all the sap Saturday night, their sap buckets do not ordinarily make them fill in one day, and when the sap is gathered monday morning.

They do not in this respect suffer much loss. In other respects, they are called to make no more sacrifice by observing the sabbath than the people of N.E. do during the season of haying. We are now living more strictly in the Indian country among an Indian community than ever before. We are almost the only persons among a population of some 5 or 600 people who speak the English language. We have therefore a better opportunity to observe Indian manners and customs than heretofore, as well as to make proficiency in speaking the language.

Process of making sugar and skillful use of birch bark.

The process of making sugar from the (maple) sap is in general as that practiced elsewhere where this kind of sugar is make, and yet in some respects the modus operandi is very different. The sugar making season is the most an important event to the Indians every year. Every year about the middle of March the Indians, French and halfbreeds all leave the Islands for the sugar camps. As they move off in bodies from the La Pointe, sometimes in companies of 8, 10, 12 or 20 families, they make a very singular appearance.

Upon some pleasant morning about sunrise you will see these, by families, first perhaps a Frenchman with his horse team carrying his apuckuais for his lodge–provisions kettles, etc., and perhaps in addition some one or two of the [squaw?] helpers of his family. The next will be a dog train with two or three dogs with a similar load driven by some Indians. The next would be a similar train drawn by a man with a squaw pushing behind carrying a little child on her back and two or three little children trudging behind on foot. The next load in order might be a squaw drawn by dogs or a man upon a sled at each end. This forms about the variety that will be witnessed in the modes of conveyance. To see such a ([raucous?] company) [motley process?] moving off, and then listen to the Frenchmen whipping his horse, which from his hard fare is but poorly able to carry himself, and to hear the yelping of the dogs, the (crying of) the children, and the jabbering in french and Indian. And if you never saw the like before you have before you the loud and singular spectacle of the Indians going to the sugar bush.

“Frame of Lodge Used For Storage and Boiling Sap;” undated (Densmore Collection: Smithsonian)

One night they are obliged to camp out before they reach the place of making sugar. This however is counted no hardship the Indian carries his house with him. When they have made one days march it might when they come to a place where they wish to camp, all hands set to work to make to make a lodge. Some shovel away the snow another cut a few poles. Another cuts up some wood to make a fire. Another gets some pine, cedar or hemlock (boughs) to spread upon the ground for floor and carpet. By the time the snow is shoveled away the poles are ready, which the women set around in a circular form at the bottom–crossed at the top. These are covered with a few apuckuais, and while one or two are covering the putting up the house another is making a fire, & perhaps is spreading down the boughs. The blankets, provisions, etc. are then brought in the course of 20 or ½ an hour from the time they stop, the whole company are seated in their lodge around a comfortable fire, and if they are French men you will see them with their pipes in their mouths. After supper, when they have anything to eat, each one wraps himself in a blanket and is soon snoring asleep. The next day they are again under way and when they arrive at the sugar camp they live in their a lodge again till they have some time to build a more substantial (building) lodge for making sugar. A sugar camp is a large high lodge or a sort of a frame of poles covered with flagg and Birch apuckuais open at the top. In the center is a long fire with two rows of kettles suspended on wooden forks for boiling sap. As Robert (our hired man) sugar makes (the best kind of) sugar and does business upon rather a large scale in quite a systematic manner. I will describe his camp as a mode of procedure, as an illustration of the manner in which the best kind of sugar is made. His camp is some 25 or 30 feet square, made of a sort of frame of poles with a high roof open at the (top) the whole length coming down with in about (4 feet) of the ground. This frame is covered around the sides at the bottom with Flag apukuais. The outside and roof is covered with birch (bark) apukuais. Upon each side next to the wall are laid some raised poles, the whole length of the (lodge) wall. Upon these poles are laid some pine & cedar boughs. Upon these two platforms are places all the household furniture, bedding, etc. Here also they sleep at night. In the middle of the lodge is a long fire where he has two rows of kettles 16 in number for boiling sap. He has also a large trough, one end of it coming into the lodge holding several Barrels, as a sort of reservoir for sap, beside several barrels reserved for the same purpose. The sap when it is gathered is put into this trough and barrels, which are kept covered up to prevent the exposure of the sap to the wind and light and heat, as the sap when exposed sours very quick. For the same reason also when the sap and well the kettles are kept boiling night and day, as the sap kept in the best way will undergo some changes if it be not immediately boild. The sap after it is boild down to about the consistency of molases it is strained into a barrel through a wollen blanket. After standing 3 or 4 days to give it an opportunity to settle, some day, when the sap does not run very well, is then set aside for sugaring off. When two or 3 kettles are hung over the fire a small fire built directly under the bottom. A few quarts of molasses are then put into the kettles. When this is boiled enough to make sugar one kettle is taken off by Robert, by the side of which he sets down and begins to stir it with a small paddle stick. After stirring it a few moments it begins to grow all white, swells up with a peculiar tenacious kind of foam. Then it begins to grain and soon becomes hard like [?] Indian pudding. Then by a peculiar moulding for some time with a wooden large wooden spoon it becomes white as the nicest brown sugar and very clean, in this state, while it is yet warm, it is packed down into large birch bark mukoks made of holding from 50 to a hundred lbs.

Makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Ojibwe People’s Dictionary) Photo: Densmore Collection; Smithsonian

Makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Ojibwe People’s Dictionary) Photo: Densmore Collection; SmithsonianCertainly no sugar can be more cleaner than that made here, though it is not all the sugar that is made as nice. The Indians do not stop for all this long process of making sugar. Some of (their) sorup does not pass through anything in the shape of a strainer–much less is it left to stand and settle after straining, but is boiled down immediately into sugar, sticks, soot, dirt and all. Sometimes they strain their sorup through the meshes of their snow shoe, which is but little better than it would be to strain it through a ladder. Their sugar of course has rather a darker hue. The season for making sugar is the most industrious season in the whole year. If the season be favorable, every man wom and child is set to work. And the departments of labor are so various that every able bodied person can find something to do.

The British missionary John Williams describes the coconut on page 493 of his A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands (1837). (Wikimedia Commons)