Among The Otchipwees: III

July 20, 2016

By Amorin Mello

… continued from Among The Otchipwees: II

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 4 February 1885

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 335-342.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

III.

The Northern tribes have nothing deserving the name of historical records. Their hieroglyphics or pictorial writings on trees, bark, rocks and sheltered banks of clay relate to personal or transient events. Such representations by symbols are very numerous but do not attain to a system.

Their history prior to their contact with the white man has been transmitted verbally from generation to generation with more accuracy than a civilized people would do. Story-telling constitutes their literature. In their lodges they are anything but a silent people. When their villages are approached unawares, the noise of voices is much the same as in the camps of parties on pic-nic excursions. As a voyageur the pure blood is seldom a success, and one of the objections to him is a disposition to set around the camp-fire and relate his tales of war or of the hunt, late into the night. This he does with great spirit, “suiting the action to the word” with a varied intonation and with excellent powers of description. Such tales have come down orally from old to young many generations, but are more mystical than historical. The faculty is cultivated in the wigwam during long winter nights, where the same story is repeated by the patriarchs to impress it on the memory of the coming generation. With the wild man memory is sharp, and therefore tradition has in some cases a semblance to history. In substance, however, their stories lack dates, the subjects are frivolous or merely romantic, and the narrator is generally given to embellishment. He sees spirits everywhere, the reality of which is accepted by the child, who listens with wonder to a well-told tale, in which he not only believes, but is preparing to be a professional story-teller himself.

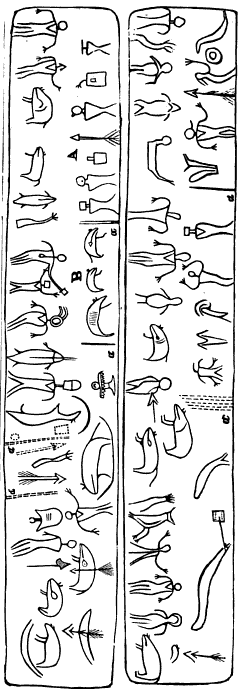

Indian picture-writings and inscriptions, in their hieroglyphics, are seen everywhere on trees, rocks and pieces of bark, blankets and flat pieces of wood. Above Odanah, on Bad River, is a vertical bank of clay, shielded from storms by a dense group of evergreens. On this smooth surface are the records of many generations, over and across each other, regardless of the rights of previous parties. Like most of their writings, they relate to trifling events of the present, such as the route which is being traveled; the game killed; or the results of a fight. To each message the totem or dodem of the writer is attached, by which he is at once recognized. But there are records of some consequence, though not strictly historical.

Charles Whittlesey also reproduced Okandikan’s autobiography in Western Reserve Historical Society Tract 41.

Before a young man can be considered a warrior, he must undergo an ordeal of exposure and starvation. He retires to a mountain, a swamp, or a rock, and there remains day and night without food, fire or blankets, as long as his constitution is able to endure the exposure. Three or four days is not unusual, but a strong Indian, destined to be a great warrior, should fast at least a week. One of the figures on this clay bank is a tree with nine branches and a hand pointing upward. This represents the vision of an Indian known to one of my voyagers, which he saw during his seclusion. He had fasted nine days, which naturally gave him an insight of the future, and constituted his motto, or chart of life. In tract No. 41 (1877), of the Western Reserve Historical Society, I have represented some of the effigies in this group; and also the personal history of Kundickan, a Chippewa, whom I saw in 1845, at Ontonagon. This record was made by himself with a knife, on a flat piece of wood, and is in the form of an autobiography. In hundreds of places in the United States such inscriptions are seen, of the meaning of which very little is known. Schoolcraft reproduced several of them from widely separated localities, such as the Dighton Boulder, Rhode Island; a rock on Kelley’s Island, Lake Erie, and from pieces of birch bark, conveying messages or memoranda to aid an orator in his speeches.

~ New Sources of Indian History, 1850-1891: The Ghost Dance and the Prairie Sioux, A Miscellany by Stanley Vestal, 2015, page 269.

The “Indian rock” in the Susquehanna River, near Columbia, Pennsylvania; the God Rock, on the Allegheny, near Brady’s Bend; inscriptions on the Ohio River Rocks, near Wellsville, Ohio, and near the mouth of the Guyandotte, have a common style, but the particular characters are not the same. Three miles west of Barnsville, in Belmont County, Ohio, is a remarkable group of sculptured figures, principally of human feet of various dimensions and uncouth proportions. Sitting Bull gave a history of his exploits on sheets of paper, which he explained to Dr. Kimball, a surgeon in the army, published in fascimile in Harper’s Weekly, July 1876. Such hieroglyphics have been found on rocky faces in Arizona, and on boulders in Georgia.

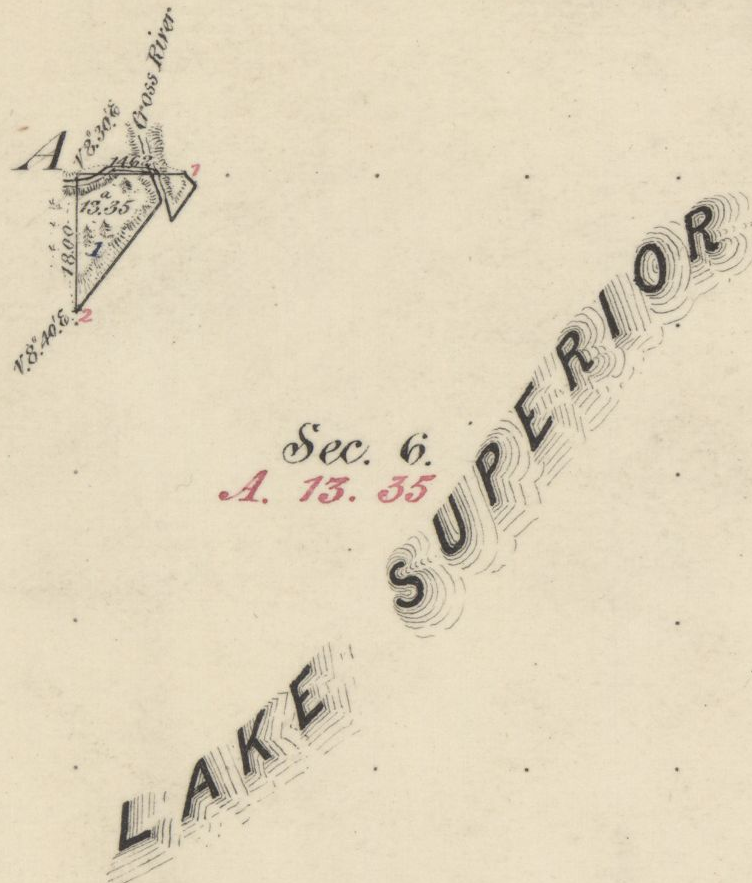

Pointe De Froid is the northwestern extremity of La Pointe on Madeline Island. Map detail from 1852 PLSS survey.

~ Report of a geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota: and incidentally of a portion of Nebraska Territory, by David Dale Owen, 1852, page 420.

~ Geology of Wisconsin: Paleontology by R. P. Whitfield, 1880, page 58.

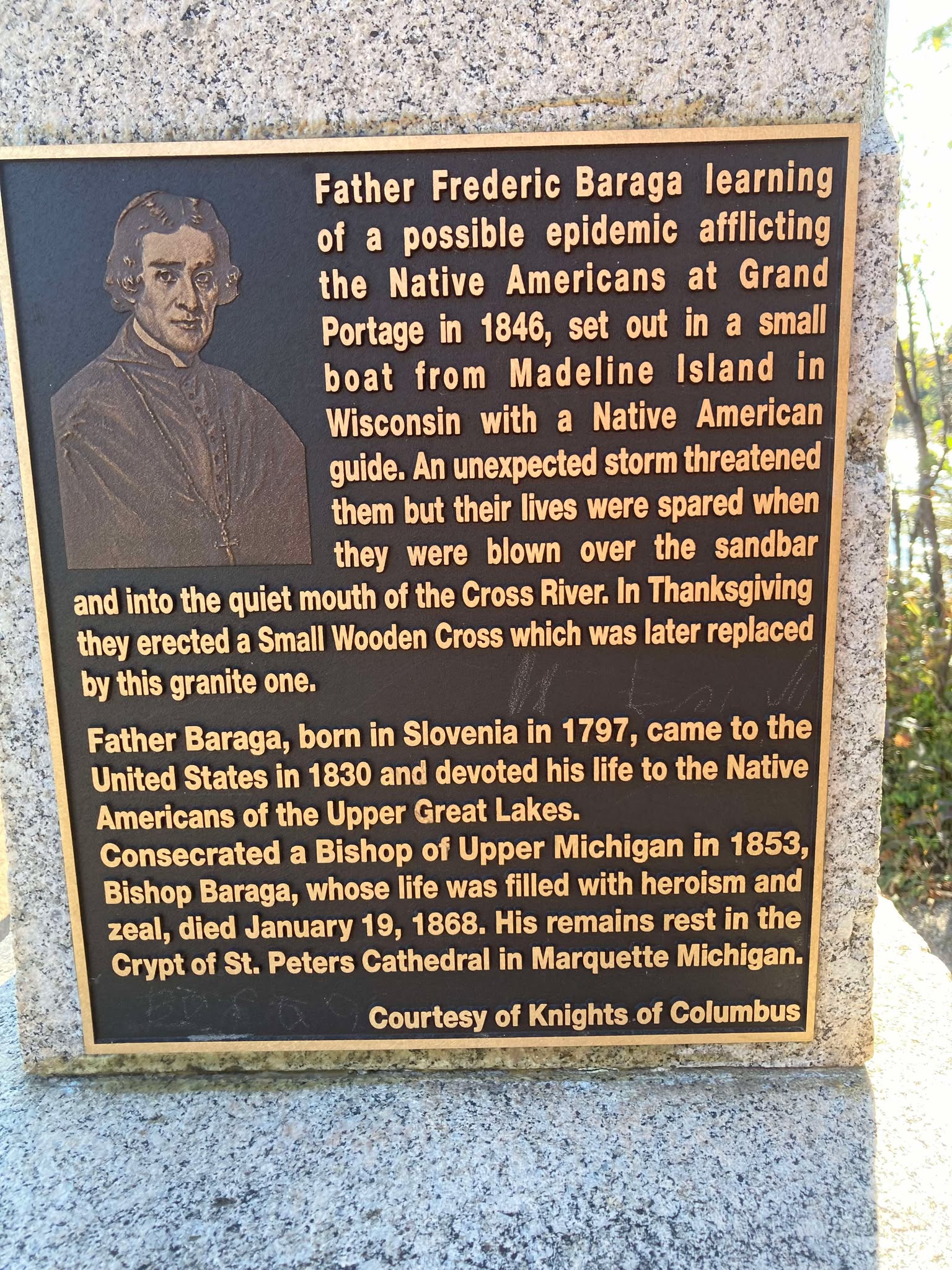

While pandemonium was let loose at La Pointe towards the close of the payment we made a bivouac on the beach, between the dock and the mission house. The voyageurs were all at the great finale which constitutes the paradise of a Chippewa. One of my local assistants was playing the part of a detective on the watch for whisky dealers. We had seen one of them on the head waters of Brunscilus River, who came through the woods up the Chippewa River. Beyond the village of La Pointe, on a sandy promontory called Pointe au Froid, abbreviated to Pointe au Fret or Cold Point, were about twenty-five lodges, and probably one hundred and fifty Indians excited by liquor. For this, diluted with more than half water, they paid a dollar for each pint, and the measure was none too large – neither pressed down nor running over. Their savage yells rose on the quiet moon-lit atmosphere like a thousand demons. A very little weak whisky is sufficient to work wonders in the stomach of a backwoods Indian, to whom it is a comparative stranger. About midnight the detective perceived our traveler from the Chippewa River quietly approaching the dock, to which he tied his canoe and went among the lodges. To the stern there were several kegs of fire-water attached, but weighted down below the surface of the water. It required but a few minutes to haul them in and stave the heads of all of them. Before morning there appeared to be more than a thousand savage throats giving full play to their powerful lungs. Two of them were staggering along the beach toward where I lay, with one man by my side. he said we had better be quiet, which, undoubtedly, was good advice. They were nearly naked, locked arm in arm, their long hair spread out in every direction, and as they swayed to and fro between the water line and the bushes, no imagination could paint a more complete representation of the demon. There was a yell to every step – apparently a bacchanalian song. They were within two yards before they saw us, and by one leap cleared everything, as though they were as much surprised as we were. The song, or howl, did not cease. It was kept up until they turned away from the beach into the mission road, and went on howling over the hill toward the old fort. It required three days for half-breed and full-blood alike to recover from the general debauch sufficiently to resume the oar and pack. As we were about to return to the Penoka Mountains, a Chippewa buck, with a new calico shirt and a clean blanket, wished to know if the Chemokoman would take him to the south shore. He would work a paddle or an oar. Before reaching the head of the Chegoimegon Bay there was a storm of rain. He pulled off his shirt, folded it and sat down upon it, to keep it dry. The falling rain on his bare back he did not notice.

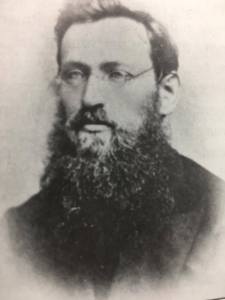

Portrait of Stephen Bonga

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

We had made the grand portage of nine miles from the foot of the cataract of the St. Louis, above Fond du Lac, and encamped on the river where the trail came to it below the knife portage. In the evening Stephen Bungo, a brother of Charles Bungo, the half-breed negro and Chippewa, came into our tent. He said he had a message from Naugaunup, second chief of the Fond du Lac band, whose home as at Ash-ke-bwau-ka, on the river above. His chief wished to know by what authority we came through the country without consulting him. After much diplomatic parley Stephen was given some pequashigon and went to his bivouac.

Joseph Granville Norwood

~ Wikipedia.org

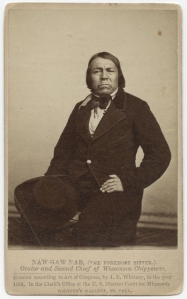

Portrait of Naagaanab

~ Minnesota Historical Society

The next morning he intimated that we must call at Naugaunup’s lodge on the way up, where probably permission might be had, by paying a reasonable sum, to proceed. We found him in a neat wigwam with two wives, on a pleasant rise of the river bluff, clear of timber, where there had been a village of the same name. His countenance was a pleasant one, very closely resembling that of Governor Corwin, of Ohio, but his features were smaller and also his stature. Dr. Norwood informed him that we had orders from the Great Father to go up the St. Louis to its source, thence to the waters running the other way to the Canada line. Nothing but force would prevent us from doing this, and if he was displeased he should make a complaint to the Indian agent at La Pointe, and he would forward it to Washington. We heard no more of the invasion of his territory, and he proceeded to do what very few Chippewas will do, offered to show us valuable minerals. In the stream was a pinnacle of black sale, about sixty feet high. Naugaunup soon appeared from behind it, near the top, in a position that appeared to be inaccessible, a very picturesque object pointing triumphantly to some veins of white quartz, which are very common in metamorphic slate.

Those who have heard him, say that he was a fine orator, having influence over his band, a respectable Indian, and a good negotiator. If he imagined there was value in those seams of quartz it is quite remarkable and contrary to universal practice among Chippewas that he should show them to white men. They claim that all minerals belong to the tribe. An Indian who received a price for showing them, and did not give every one his share, would be in danger of his life. They had also a superstitious dread of some great evil if they disclosed anything of the kind. Some times they promise to do so, but when they arrive at the spot, with some verdant white man, expecting to become suddenly rich, the Great Spirit or the Bad Manitou has carried it away. I have known more than one such instance, where persons have been sustained by hopeful expectation after many days of weary travel into the depths of the forest. The editor of the Ontonagon Miner gives one of the instances in his experience:

“Many years ago when Iron River was one of the fur stations, of John Jacob Astor and the American Fur Company, the Indians were known to have silver in its native state in considerable quantities.”

Men are now living who have seen them with chunks of the size of a man’s fist, but no one ever succeeded in inducing them to tell or show where the hidden treasure lay. A mortal dread clung to them, that if they showed white men a deposit of mineral the Great Manitou would punish them with death.

Several years since a half-breed brought in very fine specimens of vein rock, carrying considerable quantities of native silver. His report was that his wife had found it on the South Range, where they were trapping. To test his story he was sent back for more. In a few days he returned bringing with him quite a chunk from which was obtained eleven and one-half ounces of native silver. He returned home, went among the Flambeaux Indians and was killed. His wife refused to listen to any proposals or temptation from friend or foe to show the location of this vein, clinging with religious tenacity to the superstitious fears of her tribe.

When the British had a fort on St. Joseph’s Island in the St. Mary’s River, in the War of 1812, an Indian brought in a rich piece of copper pyrites. The usual mode of getting on good terms with him, by means of whisky, failed to get from him the location of the mineral. Goods were offered him; first a bundle, then a pile, afterwards a canoe-load, and finally enough to load a Mackinaw boat. No promise to disclose the place, no description or hint could be extorted. It was probably a specimen from the veins on the Bruce or Wellington mining property, only about twenty miles distant on the Canadian shore.

Detail of John Beargrease the Younger from stereograph “Lake Superior winter mail line” by B. F. Childs, circa 1870s-1880s.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

Crossing over the portage from the St. Louis River to Vermillion River, one of the voyageurs heard the report of a distant shot. They had expected to meet Bear’s Grease, with his large family, and fired a gun as a signal to them. The ashes of their fire were still warm. After much shouting and firing, it was evident that we should have no Indian society at that time. That evening, around an ample camp fire, we heard the history of the old patriarch. His former wives had borne him twenty-four children; more boys than girls. Our half-breed guide had often been importuned to take one of the girls. The old father recommended her as a good worker, and if she did not work he must whip her. Even a moderate beating always brought her to a sense of her duties. All he expected was a blanket and a gun as an offset. He would give a great feast on the occasion of the nuptials. Over the summit to Vermillion, through Vermillion Lake, passing down the outlet among many cataracts to the Crane Lake portage, there were encamped a few families, most of them too drunk to stand alone. There were two traders, from the Canada side, with plenty of rum. We wanted a guide through the intricacies of Rainy Lake. A very good-looking savage presented himself with a very unsteady gait, his countenance expressing the maudlin good nature of Tam O’Shanter as he mounted Meg. Withal, he appeared to be honest. “Yes, I know that way, but, you see, I’m drunk; can’t you wait till to-morrow.” A young squaw who apparently had not imbibed fire-water, had succeeded in acquiring a pewter ring. Her dress was a blanket of rabbit skins, made of strips woven like a rag carpet. It was bound around her waist with a girdle of deer’s hide, answering the purpose of stroud and blanket. No city belle could exhibit a ring of diamonds more conspicuously and with more self-satisfaction than this young squaw did her ring of pewter.

As we were all silently sitting in the canoes, dripping with rain, a sudden halloo announced the approach of living men. It was no other than Wau-nun-nee, the chief of the Grand Fourche bands, who was hunting for ducks among the rice. More delicious morsels never gladdened the palate than these plump, fat, rice-fed ducks. Old Wau-nun-nee is a gentleman among Indian chiefs. His band had never consented to sell their land, and consequently had no annuities. He even refused to receive a present from the Government as one of the head men of the tribe, preferring to remain wholly independent. We soon came to his village on Ash-ab-ash-kaw Lake. No band of Indians in our travels appeared as comfortable or behaved as well as this. Their country is well supplied with rice and tolerably good hunting ground. The American fur dealers (I mean the licensed ones) do not sell liquor to the Indians, and use their influence to aid Government in keeping it from them. Wau-nun-nee’s baliwick was seldom disturbed by drunken brawls. His Indians had more pleasant countenances than any we had seen, with less of the wild and haggard look than the annuity Indians. It was seldom they left their grounds, for they seldom suffered from hunger. They were comfortably clothed, made no importunities for kokoosh or pequashigon, and in gratifying their savage curiosity about our equipments they were respectful and pleasant. In his lodge the chief had teacups and saucers, with tea and sugar for his white guests, which he pressed us to enjoy. But we had no time for ceremonials, and had tea and sugar of our own. Our men recognized numerous acquaintances among the women, and as we encamped near a second village at Round Lake they came to make a draft on our provision chest. We here laid in a supply of wild rice in exchange for flour. Among this band we saw bows and arrows used to kill game. They have so little trade with the whites, and are so remote from the depots of Indian goods, that powder and lead are scarce, and guns also. For ducks and geese the bow and arrow is about as effectual as powder and shot. In truth, the community of which Wau-nun-nee was the patriarch came nearer to the pictures of Indians which poets are fond of drawing than any we saw. The squaws were more neatly clad, and their hair more often combed and braided and tied with a piece of ribbon or red flannel, with which their pappooses delighted to sport. There were among them fewer of those distinguished smoke-dried, sore-eyed creatures who present themselves at other villages.

By my estimate the channel, as we followed it to the head of the Round Lake branch, is two hundred and two mile in length, and the rise of the stream one hundred and eight feet. The portage to a stream leading into the Mississippi is one mile.

At Round Lake we engaged two young Indians to help over the portage in Jack’s place. Both of them were decided dandies, and one, who did not overtake us till late the next morning, gave an excuse that he had spent the night in courting an Indian damsel. This business is managed with them a little differently than with us. They deal largely in charms, which the medicine men furnish. This fellow had some pieces of mica, which he pulverized, and was managing to cause his inamorata to swallow. If this was effected his cause was sure to succeed. He had also some ochery, iron ore and an herb to mix with the mica. Another charm, and one very effectual, is composed of a hair from the damsel’s head placed between two wooden images. Our Lothario had prepared himself externally so as to produce a most killing effect. His hair was adorned with broad yellow ribbons, and also soaked in grease. On his cheeks were some broad jet black stripes that pointed, on both sides, toward his mouth; in his ears and nose, some beads four inches long. For a pouch and medicine bag he had the skin of a swan suspended from his girdle by the neck. His blanket was clean, and his leggings wrought with great care, so that he exhibited a most striking collection of colors.

At Round Lake we overtook the Cass Lake band on their return from the rice lakes. This meeting produced a great clatter of tongues between our men and the squaws, who came waddling down a slippery bank where they were encamped. There was a marked difference between these people and those at Ash-ab-ash-kaw. They were more ragged, more greasy, and more intrusive.