The banner at the top of this website reads “Primary history of the Chequamegon Region before 1860. In the About page, I explain that 1860 is really an arbitrary round number, and what I’m really focusing on is this area before it became dominated by an English-speaking American society. This is not an easy date to pinpoint, though I think most would argue it happened between 1842 and 1855. While the Treaty of La Pointe in 1854 is an easy marker of separation between the two eras, I would argue that the annuity payments that took place on the island the next summer, can also be seen as a watershed moment in history.

Crocket McElroy from a short biography in the Cyclopedia of Michigan: historical and biographical, comprising a synopsis of general history of the state, and biographical sketches of men who have, in their various spheres, contributed toward its development. Ed. John Bersey. Western Engraving and Publishing; 1890 (Digitized by Google Books)

The 1855 payment, in many ways, illustrates the change in the relationship between the United States and the Ojibwe people that would characterize the rest of the 19th century and early 20th century. The threats of Ojibwe removal or military conflict between the two nations largely ended with the treaty and the establishment of reservations. However, in their place was a paternalistic and domineering government that felt a responsibility to “civilize the Indian.” No one at this time embodied this idea more than George Manypenny, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and it was Manypenny, himself, who presided over the 1855 payment.

The days were over when master politicians like Buffalo and Flat Mouth could try to negotiate with the Americans as equals while playing them off of the British in Canada at the same time. In fact, Buffalo died during the 1855 payment, and the new generation of chiefs were men who had spent their youth in a time of Ojibwe power, but who would grow old in an era where government Indian Agents would rule the reservations like petty dictators. The men of this generation, Jayjigwyong (“Little Buffalo”) of Red Cliff, Blackbird of Bad River, and Naaganab of Fond du Lac, were the ones who were prominent during the summer of 1855.

Until this point, our knowledge of the 1855 payment cams largely from the essay The Chippewas of Lake Superior by a witness named Richard Morse. Dr. Morse’s writing includes a number of speeches by the Ojibwe leadership and a number of smaller accounts of items that piqued his interest, including the story of Hanging Cloud the female warrior, and the deaths of Buffalo and Oshogay. However, when reading Morse, one gets the sense that he or she is not getting stray observations of an uninformed visitor rather than a complete story.

It was for this reason that I got excited today when I stumbled across a second memoir of the 1855 payment. It comes from Volume 5 of Americana, a turn-of-the-century historical journal. Crocket McElroy, the author, is writing around fifty years after he witnessed the 1855 payment as a young clerk in Bayfield.

We still do not have a full picture of the 1855 payment, since we will never have full written accounts from Blackbird, Naaganab, and the rest of the Ojibwe leadership, but McElroy’s essay does provide an interesting contrast to Morse’s. The two men saw many of the same events but interpreted them very differently. And while McElroy’s racist beliefs skew his observations and make his writing hard to stomach, in some ways his observations are as informative as Morse’s even though his work is considerably shorter:

From Americana v.5 American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

AN INDIAN PAYMENT

By Crocket McElroy

In August 1855 about three thousand Chippewa Indians gathered at the village of Lapointe, on Lapointe Island, Lake Superior, for an Indian Payment and also to hold a council with the commissioner of Indian affairs, who at that time was George W. Monypenny of Ohio. The Indians selected for their orator a chief named Blackbird, and the choice was a good one, as Blackbird held his own well in a long discussion with the commissioner. Blackbird was not one of the haughty style of Indians, but modest in his bearing, with a good command of language and a clear head. In his speeches he showed much ingenuity and ably pleaded the cause of his people. He spoke in Chippewa stopping frequently to give the interpreter time to translate what he said into English. In beginning his address he spoke substantially as follows:

“My great white father, we are pleased to meet you and have a talk with you We are friends and we want to remain friends. We expect to do what you want us to do, and we hope that you will deal kindly with us. We wish to remind you that we are the source from which you have derived all your riches. Our furs, our timber, our lands, everything that we have goes to you; even the gold out of which that chain was forged (pointing to a heavy watch chain that the commissioner carried) came from us, and now we hope that you will not use that chain to bind us.”

Buffalo’s death in 1855 marked the end of an era. Jayjigwyong (Young Buffalo) was no young man when he took over from his father. The connection between Buffalo and Buffalo, New York also appears in Morse on page 368, although he says the names are not connected. If Buffalo did indeed live in the Niagara region, it may lend credence to the hypothesis explored in Paap’s Red Cliff Wisconsin, that Buffalo fought the Americans in the Indian Wars of the 1790s and signed the Treaty of Greenville (Photo: Wikimedia Images).

The commissioner was an amiable man and got along pleasantly with his savage friends, besides managing the council skilfully.

Among the prominent chiefs attending the payment was Buffalo, then called “Old Buffalo,” as he had a son called “Young Buffalo” who was also an old man. Old Buffalo was said to be over one hundred years old. He died during the council and the writer witnessed the funeral. He was buried in the Indian grave yard near the Indian church in Lapointe village. The body was laid on a stretcher formed of two poles laid lengthwise and several poles laid crosswise. The stretcher was carried on the shoulders of four Indians. Following the corpse was a long procession of Indians in irregular order. It was claimed for Buffalo, that he maintained a camp many years before at the mouth of Buffalo Creek on the Niagara River, and that the creek and the present large and flourishing city of Buffalo were named after him.

Naaganab’s (above) comments about Wheeler being ungenerous with food echoed a common Ojibwe complaint about the ABCFM missionaries. Wheeler’s Protestant Ethic of upward mobility and self-reliance made little sense in a tribal society where those who had extra were expected to share. Read The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, edited by Theresa Schenck, for Naaganab’s experience with another missionary two decades earlier. Read this post if you don’t understand why the Ojibwe resented the missionaries over the issue of food (Photo from Newberry Library Collections, Chicago).

Another prominent chief attending the conference was Ne-gon-up, head chief of the Fond du lac Indians. Negonup’s camp was on the south side of the St Louis River in Wisconsin, about where the city of Superior now stands. Negonup was a shrewd, practical Indian and had considerable influence. The writer saw him going to the Indian church one Sunday, there was a squaw on each side of him and one behind, they were said to be his wives. A good and zealous Methodist minister named Wheeler desired to talk to Negonup and his tribe about the Great Spirit. Negonup it is said expressed himself in regard to Mr. Wheeler in this manner:

“Mr. Wheeler comes to us and says he wants to do us good. He looks like a good man and we think he is and we believe his intentions are good, but he does not bring us any proof. Now if Mr. Wheeler will bring to me a good supply of barrels of flour and barrels of pork, for distribution among my people, then I shall be convinced that he is a good man.”

The sessions of the council began on August 30th and were held in the open air on a grass common. On the second day the special police acting under directions from the Indian agent H. Gilbert, seized two barrels of whisky that was being secretly sold to the half-breeds and Indians. The proceedings of the council were suspended and the two barrels of whisky were rolled into the center of the common. Mr. Gilbert then took a hatchet, chopped a hole into each barrel and poured the whiskey out on the ground. A few half-breeds and Indians in the outer edge of the crowd dropped on their knees and sucked some of the whisky out of the grass.

In accordance with the stipulations of a treaty, the government was distributing among the Indians a large quantity of blankets, cotton cloth, calico, and other kinds of cloth to be used for clothing or bedding. Also provisions, farming implements, cooking utensils, and other articles supposed to be useful to the Indians The Indians were entitled to a certain value per head in goods and also in cash. The cash payment was I think two dollars and fifty cents per head. The goods were distributed first to the heads of families. After the goods were disposed of the money was paid in gold and silver.

Notwithstanding the care exercised by the Indian agent to prevent the sale of liquor to Indians they were still able to find it, and occasionally some would be found drunk. One who was acting badly was arrested and confined in a log lockup, and while there created a great disturbance. He pounded his head against the logs and yelled so loud and continuously as to excite the other Indians and some of them became very angry. It was feared they would make trouble and a rumor spread through the village that the Indians would rise that night, break into the jail, release the prisoner and then murder all the white people on the island. As the Indians outnumbered the whites ten to one the excitement became painfully intense and a meeting of whites and half breeds was called to take action. A company of volunteers was organized to assist the Indian agent in searching for and destroying liquors. A systematic and thorough search was made of nearly every building in the village, from attic to cellar. A good deal of liquor was found and promptly destroyed. After two days of this kind of work the danger of murders being committed by drunken Indians was supposed to be past and quiet was restored. Either the laws of the United States give the Indian agent in such cases arbitrary power, or the agent assumed it at any rate it was courageously exercised.

Rev. Leonard Wheeler’s mission was Congregational-Presbyterian, not Methodist as McElroy states. The Fond du Lac Indians were familiar with both Protestant sects, but the “civilized” Fond du Lac chiefs Zhingob (Nindibens) and Naaganab, much like Jayjigwyong in Red Cliff, aligned with the Catholics. This represented a major threat to Wheeler and his virulently anti-Catholic colleagues who envisioned a fully-assimilated Protestant future for the Ojibwe (Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society).

A good many of the Indians were warriors, who were frequently, in fact, almost constantly at war with the Sioux. They were pure savages, totally uncivilized, and the faces of some of them had an expression as utterly destitute of human kindness as I have ever seen in wild beasts. A small portion of them were partially civilized and a very few could talk a little English. Nearly all the Indians came to the island in their own canoes bringing along the entire family.

The agent completed his work in about twenty-five days.

There is hardly anything that a savage Indian has less use for than money and when it comes into his hands he hastens to spend it. It goes quickly into the hands of traders, half-breeds and the partially civilized Indians.

A few days previous to the opening of the council, the Indians gave a war dance which was attended by a large crowd of Indians and whites. A ring about twenty feet in diameter was formed by male Indians and squaws sitting cross legged around it, a number of whom had small unmusical drums. The ceremony commenced with the Indians in the circle singing: “Hi yi yi, i e, i o.” This was the whole song and it was repeated over and over with tiresome monotony, and the drums were beaten to keep time with the singing. After the singing had been going on for some minutes a warrior bounced into the ring and began to talk. Instantly the singing stopped. The orator showed great agitation, no doubt for the purpose of convincing his hearers that he was a brave warrior. He hopped and jumped about the ring, swung his arms violently and pointed toward his enemies in the west. He was apparently telling how badly the Sioux had been beaten in the last fight, or how they would be whipped in the next one, and perhaps also how many scalps he had taken. So soon as the talking stopped the singing would begin again and after a little more of the ridiculous music, another warrior would bounce into the ring and begin his speech.

For this occasion some of the Indians were painted with different colored paints, made out of clay and other coarse materials daubed on without much regard to order or taste. A good many males were entirely naked except that they wore breech clouts. One Indian had one leg painted black and the other red, and his face was daubed with various colored paints, so that except in the form of his body, he looked like anything but a human being. When a few speeches had been made the war dance ended.

During the council a begging party of Indians went the rounds of the camps to solicit donations for a squaw widow with four children, whose husband had been killed by the Sioux. At every tent something was given and the articles were carried along by the party. One of the presents was a dead dog, a rope was tied to the dog’s legs and an Indian put the rope over his head and let the dog hang on his back. The widow marched in the procession she was a large strong woman with long hair in a single braid hanging down her back. To the end of the braid was tied two scalps which dangled about one foot below. It was said she had killed two Sioux in revenge for their killing her husband and had taken their scalps.

Among the notable persons in attendance at the council, was a lady distinguished as a writer of fiction under the pen name of Grace Greenwood. She had been recently married to a Mr. Lippincott and was accompanied by her husband. Mrs. Lippincott. did not look like a healthy woman, but she lived to be forty-nine years older and to be highly respected and honored before she died in the year 1904.

Hopefully this document will contribute to the understanding of our area in the earliest years after the Treaty of 1854. Look for an upcoming post with a letter from Blackbird himself on issues surrounding the payment.

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

McElroy, Crocket. “An Indian Payment.” Americana v.5. American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Western Publishing and Engraving. Cyclopedia of Michigan: historical and biographical, comprising a synopsis of general history of the state, and biographical sketches of men who have, in their various spheres, contributed toward its development. John Bersey Ed. Western Publishing and Engraving Co., 1890.

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Capitol Busts

July 17, 2013

This post is one of several that seek to determine how many images exist of Great Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855. To learn why this is necessary, please read this post introducing the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

Posts on Chequamegon History are generally of the obscure variety and are probably only interesting to a handful of people. I anticipate this one could cause some controversy as it concerns an object that holds a lot of importance to many people who live in our area. All I can say about that is that this post represents my research into original historical documents. I did not set out to prove anybody right or wrong, and I don’t think this has to be the last word on the subject. This post is simply my reasoned conclusions based on the evidence I’ve seen. Take from it what you will.

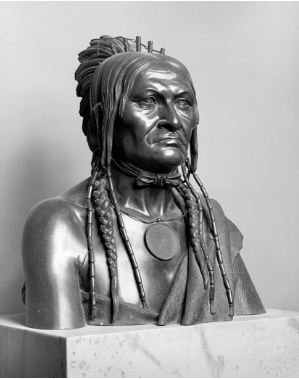

Be sheekee, or Buffalo by Francis Vincenti, Marble, Modeled 1855, Carved 1856 (United States Senate)

Be Sheekee: A Chippewa Warrior from the Sources of the Mississippi, bronze, by Joseph Lassalle after Francis Vincenti, House wing of the United States Capitol (U.S. Capitol Historical Society).

“A Chippewa Warrior from the Sources of the Mississippi”

There is no image that has been more widely identified with Chief Buffalo from La Pointe than the marble bust and bronze copy in the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington D.C. Red Cliff leaders make a point of visiting the statues on trips to the capital city, the tribe uses the image in advertising and educational materials, and literature from the United States Senate about the bust includes a short biography of the La Pointe chief.

I can trace the connection between the bust and the La Pointe chief to 1973, when John O. Holzhueter, editor of the Wisconsin Magazine of History wrote an article for the magazine titled Chief Buffalo and Other Wisconsin-Related Art in the National Capitol. From Holzhueterʼs notes we can tell that in 1973, the rediscovery of the story of the La Pointe Buffalo was just beginning at the Wisconsin Historical Society (the publisher of the magazine). Holzhueter deserves credit for helping to rekindle interest in the chief. However, he made a critical error.

In the article he briefly discusses Eshkibagikoonzhe (Flat Mouth), the chief of the Leech Lake or Pillager Ojibwe from northern Minnesota. Roughly the same age as Buffalo, Flat Mouth is as prominent a chief in the history of the upper Mississippi as Buffalo is for the Lake Superior bands. Had Holzhueter investigated further into the life of Flat Mouth, he may have discovered that at the time the bust was carved, the Pillagers had another leader who had risen to prominence, a war chief named Buffalo.

Holzhueter clearly was not aware that there was more than one Buffalo, and thus, he had to invent facts to make the history fit the art. According to the article (and a book published by Holzhueter the next year) the La Pointe Buffalo visited President Pierce in Washington in January of 1855. Buffalo did visit Washington in 1852 in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, but the old chief was nowhere near Washington in 1855. In fact, he was at home on the island in declining health having secured reservations for his people in Wisconsin the previous summer. He would die in September of 1855. The Buffalo who met with Pierce, of course, was the war chief from Leech Lake.

“He wore in his headdress 5 war-eagle feathers“

The Pillager Buffalo was in Washington for treaty negotiations that would transfer most of the remaining Ojibwe land in northern Minnesota to the United States and create reservations at the principal villages. The minutes of the February 1855 negotiations between the Minnesota chiefs and Indian Commissioner George Manypenny are filled with Ojibwe frustration at Manypennyʼs condescending tone. The chiefs, included the powerful young Hole-in-the-Day, the respected elder Flat Mouth, and Buffalo, who was growing in experience and age, though he was still considerably younger than Flat Mouth or the La Pointe Buffalo. The men were used to being called “red children” in communications with their “fathers” in the government, but Manypennyʼs paternalism brought it to a new low. Buffalo used his clothing to communicate to the commissioner that his message of assimilation to white ways was not something that all Ojibwes desired. Manypennyʼs words and Buffaloʼs responses as interpreted by the mix- blooded trader Paul Beaulieu follow:

The commissioner remarked to Buffalo, that if he was a young man he would insist upon his dispensing with his headdress of feathers, but that, as he was old, he would not disturb a custom which habit had endeared to him.

Buffalo repoled ithat the feathered plume among the Chippewas was a badge of honor. Those who were successful in fighting with or conquering their enemies were entitled to wear plumes as marks of distinction, and as the reward of meritorious actions.The commissioner asked him how old he was.

Buffalo said that was a question which he could not answer exactly. If he guessed right, however, he supposed he was about fifty. (He looked, and was doubtless, much

older).Commissioner. I would think, my firend, you were older than that. I would like to philosophise with you about that headdress, and desired to know if he had a farm, a house, stock, and other comforts about him.

Buffalo. I have none of those things which you have mentioned. I live like other members of the tribe.

Commissioner. How long have you been in the habit of painting—thirty years or more?

Buffalo. I can not tell the number of years. It may have been more or it may have been less. I have distinguished myself in war as well as in peace among my people and the whites, and am entitled to the distinction which the practice implies.

Commissioner. While you, my firend, have been spending your time and money in painting your face, how many of your white brothers have started without a dollar in the world and acquired all those things mentioned so necessary to your comfort and independent support. The paint, with the exception of what is now on my friend’s face, has disappeared, but the white persons to whom I alluded by way of contrast are surrounded by all the comforts of life, the legitimate fruits of their well-directed industry. This illustrates the difference between civilized and savage life, and the importance of our red brothers changing their habits and pursuits for those of the white.

Major General Montgomery C. Meigs was a Captain before the Civil War and was in charge of the Capitol restoration, As with Thomas McKenney in the 1820s, Meigs was hoping to capture the look of the “vanishing Indian.” He commissioned the busts of the Leech Lake chiefs during the 1855 Treaty negotiations. (Wikimedia Images)

While Manypenny clearly did not like the Ojibwe way of life or Buffaloʼs style of dress, it did catch the attention of the authorities in charge of building an extension on the U.S. Capitol. Captain Montgomery Meigs, the supervisor, had hired numerous artists and much like Thomas McKenney two decades earlier, was looking for examples of the indigenous cultures that were assumed to be vanishing. On February 17th, Meigs received word from Seth Eastman that the Ojibwe delegation was in town.

The Captain met Bizhiki and described him in his journal:

“He is a fine-looking Indian, with character strongly marked. He wore in his headdress 5 war-eagle feathers, the sign of that many enemies put to death by his hand, and sat up, an old murderer, as proud of his feathers as a Frenchman of his Cross of the Legion of Honor. He is a leading warrior rather than a chief, but he has a good head, one which would not lead one, if he were in the Senate, to think he was not fit to be the companion of the wise of the land.”

Buffalo was paid $5.00 and sat for three days with the skilled Italian sculptor Francis Vincenti. Meigs recorded:

“Vincenti is making a good likeness of a fine bust of Buffalo. I think I will have it put into marble and placed in a proper situation in the Capitol as a record of the Indian culture. 500 years hence it will be interesting.”

Vincenti first formed clay models of both Buffalo and Flat Mouth. The marbles would not be finished until the next year. A bronze replica of Buffalo was finished by Joseph Lassalle in 1859. The marble was put into the Senate wing of the Capitol, and the bronze was placed in the House wing.

Clues in the Marble

The sculptures themselves hold further clues that the man depicted is not the La Pointe Buffalo. Multiple records describe the La Pointe chief as a very large man. In his obituary, recorded the same year the statue was modeled, Morse writes:

Any one would recognize in the person of the Buffalo chief, a man of superiority. About the middle height, a face remarkably grave and dignified, indicating great thoughtfulness; neat in his native attire; short neck, very large head, and the most capacious chest of any human subject we ever saw.

At the time of his death, he was thought to have been over ninety years old. The man in the sculpture is lean and not ninety. In addition, there is another clue that got by Holzhueter even though he printed it in his article. There is a medallion around the neck of the bronze bust that reads, “Beeshekee, the BUFFALO; A Chippewa Warrior from the Sources of the Mississippi…” This description works for a war chief from Leech Lake, but makes no sense for a civil chief and orator from La Pointe.

Another Image of the Leech Lake Bizhiki

The Treaty of 1855 was signed on February 22, and the Leech Lake chiefs returned to Minnesota. By the outbreak of the Civil War, Flat Mouth had died leaving Buffalo as the most prominent Pillager chief. Indian-White relations in Minnesota grew violent in 1862 as the U.S.- Dakota War (also called the Sioux Uprising) broke out in the southern part of the state. The Gull Lake chief, Hole in the Day, who had claimed the title of head of the Ojibwes, was making noise about an Ojibwe uprising as well. When he tried to use the Pillagers in his plan, Buffalo voiced skepticism and Hole in the Dayʼs plans petered out. In 1863, Buffalo returned to Washington for a new treaty. Ironically, he was still very much alive in the midst of complicated politics in a city where his bust was on display as monument to the vanishing race.

At some point during these years, the Pillager Buffalo had his photograph taken by Whitneyʼs Gallery in St. Paul. Although the La Pointe Buffalo was dead by this time, internet sites will occasional connect it with him even with an original caption that reads “Head Chief of the Leech Lake Chippewas.”

The Verdict

Although it wasn’t the outcome I was hoping for, my research leads me to definitively conclude that the busts in the U.S. Capitol are of Buffalo the Leech Lake war chief. It’s disappointing for our area to lose this Washington connection, but our loss it Leech Lake’s gain. Though less well-known than the La Pointe band’s chief, their chief Buffalo should also be remembered for his role in history.

Not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe: This is Chief Buffalo from Leech Lake.

Not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe: This is Chief Buffalo from Leech Lake.

Not Chief Buffalo from La Pointe: This is Chief Buffalo from Leech Lake.

Sources:

Holzhueter, John O. “Chief Buffalo and Other Wisconsin-Related Art in the National Capitol.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 56.4 (1973): 284-89. Print.

———– Madeline Island & the Chequamegon Region. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1974. Print.

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 21 June 2012. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Kloss, William, Diane K. Skvarla, and Jane R. McGoldrick. United States Senate Catalogue of Fine Art. Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O., 2002. Print.

Legendary Waters Resort and Casino. Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, 2012. Web. 28 June 2012. <http://www.legendarywaters.com/>.

Minutes of the 1855 Treaty. 1855. MS. Bureau of Indian Affairs, Washington. Gibagdinamaagoom. White Earth Tribal and Community College Et. Al. Web. 28 June 2012. <gibagadinamaagoom.info/images/1855TreatyMinutes.pdf>.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Treuer, Anton. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul, MN: Borealis, 2010. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Whitney’s Gallery. Be-she-kee (Buffalo). c.1860. Photograph. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul. MHS Visual Resource Database. Minnesota Historical Society, 2012. Web. 28 June 2012. <http://collections.mnhs.org/visualresources/>.

Wolff, Wendy, ed. Capitol Builder: The Shorthand Journals of Montgomery C. Meigs, 1853-1859, 1861. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC: 2001. Print.

No Princess Zone: Hanging Cloud, the Ogichidaakwe

May 12, 2013

This image of Aazhawigiizhigokwe (Hanging Cloud) was created 35 years after the battle depicted by Marr and Richards Engraving of Milwaukee for use in Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).

Here is an interesting story I’ve run across a few times. Don’t consider this exhaustive research on the subject, but it’s something I thought was worth putting on here.

In late 1854 and 1855, the talk of northern Wisconsin was a young woman from from the Chippewa River around Rice Lake. Her name was Ah-shaw-way-gee-she-go-qua, which Morse (below) translates as “Hanging Cloud.” Her father was Nenaa’angebi (Beautifying Bird) a chief who the treaties record as part of the Lac Courte Oreilles band. His band’s territory, however, was further down the Chippewa from Lac Courte Oreilles, dangerously close to the territories of the Dakota Sioux. The Ojibwe and Dakota of that region had a long history of intermarriage, but the fallout from the Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1825) led to increased incidents of violence. This, along with increased population pressures combined with hunting territory lost to white settlement, led to an intensification of warfare between the two nations in the mid-18th century.

As you’ll see below, Hanging Cloud gained her fame in battle. She was an ogichidaakwe (warrior). Unfortunately, many sources refer to her as the “Chippewa Princess.” She was not a princess. Her father was not a king. She did not sit in a palace waited on hand and foot. Her marriageability was not her only contribution to her people. Leave the princesses in Europe. Hanging Cloud was an ogichidaakwe. She literally fought and killed to protect her people.

Americans have had a bizarre obsession with the idea of Indian princesses since Pocahontas. Engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe (1616) Wikimedia Images

Americans have had a bizarre obsession with the idea of Indian princesses since Pocahontas. Engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe (1616) Wikimedia ImagesIn An Infinity of Nations, Michael Witgen devotes a chapter to America’s ongoing obsession with the concept of the “Indian Princess.” He traces the phenomenon from Pocahontas down to 21st-century white Americans claiming descent from mythical Cherokee princesses. He has some interesting thoughts about the idea being used to justify the European conquest and dispossession of Native peoples. I’m going to try to stick to history here and not get bogged down in theory, but am going to declare northern Wisconsin a “NO PRINCESS ZONE.”

Ozhaawashkodewekwe, Madeline Cadotte, and Hanging Cloud were remarkable women who played a pivotal role in history. They are not princesses, and to describe them as such does not add to their credit. It detracts from it.

Anyway, rant over, the first account of Hanging Cloud reproduced here comes from Dr. Richard E. Morse of Detroit. He observed the 1855 annuity payment at La Pointe. This was the first payment following the Treaty of 1854, and it was overseen directly by Indian Affairs Commissioner George Manypenny. Morse records speeches of many of the most prominent Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs at the time, records the death of Chief Buffalo in September of that year, and otherwise offers his observations. These were published in 1857 as The Chippewas of Lake Superior in the third volume of the State Historical Society’s Wisconsin Historical Collections. This is most of pages 349 to 354:

“The “Princess”–AH-SHAW-WAY-GEE-SHE-GO-QUA–The Hanging Cloud.

The Chippewa Princess was very conspicuous at the payment. She attracted much notice; her history and character were subjects of general observation and comment, after the bands, to which she was, arrived at La Pointe, more so than any other female who attended the payment.

She was a chivalrous warrior, of tried courage and valor; the only female who was allowed to participate in the dancing circles, war ceremonies, or to march in rank and file, to wear the plumes of the braves. Her feats of fame were not long in being known after she arrived; most persons felt curious to look upon the renowned youthful maiden.

Nenaa’angebi as depicted on the cover of Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).

Nenaa’angebi as depicted on the cover of Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians (Wikimedia Images).She is the daughter of Chief NA-NAW-ONG-GA-BE, whose speech, with comments upon himself and bands, we have already given. Of him, who is the gifted orator, the able chieftain, this maiden is the boast of her father, the pride of her tribe. She is about the usual height of females, slim and spare-built, between eighteen and twenty years of age. These people do not keep records, nor dates of their marriages, nor of the birth of their children.

This female is unmarried. No warrior nor brave need presume to win her heart or to gain her hand in marriage, who cannot prove credentials to superior courage and deeds of daring upon the war-path, as well as endurance in the chase. On foot she was conceded the fleetest of her race. Her complexion is rather dark, prominent nose, inclining to the Roman order, eyes rather large and very black, hair the color of coal and glossy, a countenance upon which smiles seemed strangers, an expression that indicated the ne plus ultra of craft and cunning, a face from which, sure enough, a portentous cloud seemed to be ever hanging–ominous of her name. We doubt not, that to plunge the dagger into the heart of an execrable Sioux, would be more grateful to her wish, more pleasing to her heart, than the taste of precious manna to her tongue…

…Inside the circle were the musicians and persons of distinction, not least of whom was our heroine, who sat upon a blanket spread upon the ground. She was plainly, though richly dressed in blue broad-cloth shawl and leggings. She wore the short skirt, a la Bloomer, and be it known that the females of all Indians we have seen, invariably wear the Bloomer skirt and pants. Their good sense, in this particular, at least, cannot, we think, be too highly commended. Two plumes, warrior feathers, were in her hair; these bore devices, stripes of various colored ribbon pasted on, as all braves have, to indicate the number of the enemy killed, and of scalps taken by the wearer. Her countenance betokened self-possession, and as she sat her fingers played furtively with the haft of a good sized knife.

The coterie leaving a large kettle hanging upon the cross-sticks over a fire, in which to cook a fat dog for a feast at the close of the ceremony, soon set off, in single file procession, to visit the camp of the respective chiefs, who remained at their lodges to receive these guests. In the march, our heroine was the third, two leading braves before her. No timid air and bearing were apparent upon the person of this wild-wood nymph; her step was proud and majestic, as that of a Forest Queen should be.

The party visited the various chiefs, each of whom, or his proxy, appeared and gave a harangue, the tenor of which, we learned, was to minister to their war spirit, to herald the glory of their tribe, and to exhort the practice of charity and good will to their poor. At the close of each speech, some donation to the beggar’s fun, blankets, provisions, &c., was made from the lodge of each visited chief. Some of the latter danced and sung around the ring, brandishing the war-club in the air and over his head. Chief “LOON’S FOOT,” whose lodge was near the Indian Agents residence, (the latter chief is the brother of Mrs. Judge ASHMAN at the Soo,) made a lengthy talk and gave freely…

…An evening’s interview, through an interpreter, with the chief, father of the Princess, disclosed that a small party of Sioux, at a time not far back, stole near unto the lodge of the the chief, who was lying upon his back inside, and fired a rifle at him; the ball grazed his nose near his eyes, the scar remaining to be seen–when the girl seizing the loaded rifle of her father, and with a few young braces near by, pursued the enemy; two were killed, the heroine shot one, and bore his scalp back to the lodge of NA-NAW-ONG-GA-BE, her father.

At this interview, we learned of a custom among the Chippewas, savoring of superstition, and which they say has ever been observed in their tribe. All the youths of either sex, before they can be considered men and women, are required to undergo a season of rigid fasting. If any fail to endure for four days without food or drink, they cannot be respected in the tribe, but if they can continue to fast through ten days it is sufficient, and all in any case required. They have then perfected their high position in life.

This Princess fasted ten days without a particle of food or drink; on the tenth day, feeble and nervous from fasting, she had a remarkable vision which she revealed to her friends. She dreamed that at a time not far distant, she accompanied a war party to the Sioux country, and the party would kill one of the enemy, and would bring home his scalp. The war party, as she had dreamed, was duly organized for the start.

Against the strongest remonstrance of her mother, father, and other friends, who protested against it, the young girl insisted upon going with the party; her highest ambition, her whole destiny, her life seemed to be at stake, to go and verify the prophecy of her dream. She did go with the war party. They were absent about ten or twelve days, the had crossed the Mississippi, and been into the Sioux territory. There had been no blood of the enemy to allay their thirst or to palliate their vengeance. They had taken no scalp to herald their triumphant return to their home. The party reached the great river homeward, were recrossing, when lo! they spied a single Sioux, in his bark canoe near by, whom they shot, and hastened exultingly to bear his scalp to their friends at the lodges from which they started. Thus was the prophecy of the prophetess realized to the letter, and herself, in the esteem of all the neighboring bands, elevated to the highest honor in all their ceremonies. They even hold her in superstitious reverence. She alone, of the females, is permitted in all festivities, to associate, mingle and to counsel with the bravest of the braves of her tribe…”

Benjamin Armstrong

Benjamin ArmstrongBenjamin Armstrong’s memoir Early Life Among the Indians also includes an account of the warrior daughter of Nenaa’angebi. In contrast to Morse, the outside observer, Armstrong was married to Buffalo’s niece and was the old chief’s personal interpreter. He lived in this area for over fifty years and knew just about everyone. His memoir, published over 35 years after Hanging Cloud got her fame, contains details an outsider wouldn’t have any way of knowing.

Unfortunately, the details don’t line up very well. Most conspicuously, Armstrong says that Nenaa’angebi was killed in the attack that brought his daughter fame. If that’s true, then I don’t know how Morse was able to record the Rice Lake chief’s speeches the following summer. It’s possible these were separate incidents, but it is more likely that Armstrong’s memories were scrambled. He warns us as much in his introduction. Some historians refuse to use Armstrong at all because of discrepancies like this and because it contains a good deal of fiction. I have a hard time throwing out Armstrong completely because he really does have the insider’s knowledge that is lacking in so many primary sources about this area. I don’t look at him as a liar or fraud, but rather as a typical northwoodsman who knows how to run a line of B.S. when he needs to liven up a story. Take what you will of it, these are pages 199-202 of Early Life Among the Indians.

“While writing about chiefs and their character it may not be amiss to give the reader a short story of a chief‟s daughter in battle, where she proved as good a warrior as many of the sterner sex.

In the ’50’s there lived in the vicinity of Rice Lake, Wis. a band of Indians numbering about 200. They were headed by a chief named Na-nong-ga-bee. This chief, with about seventy of his people came to La Point to attend the treaty of 1854. After the treaty was concluded he started home with his people, the route being through heavy forests and the trail one which was little used. When they had reached a spot a few miles south of the Namekagon River and near a place called Beck-qua-ah-wong they were surprised by a band of Sioux who were on the warpath and then in ambush, where a few Chippewas were killed, including the old chief and his oldest son, the trail being a narrow one only one could pass at a time, true Indian file. This made their line quite long as they were not trying to keep bunched, not expecting or having any thought of being attacked by their life long enemy.

The chief, his son and daughter were in the lead and the old man and his son were the first to fall, as the Sioux had of course picked them out for slaughter and they were killed before they dropped their packs or were ready for war. The old chief had just brought the gun to his face to shoot when a ball struck him square in the forehead. As he fell, his daughter fell beside him and feigned death. At the firing Na-nong-ga-bee’s Band swung out of the trail to strike the flanks of the Sioux and get behind them to cut off their retreat, should they press forward or make a retreat, but that was not the Sioux intention. There was not a great number of them and their tactic was to surprise the band, get as many scalps as they could and get out of the way, knowing that it would be but the work of a few moments, when they would be encircled by the Chippewas. The girl lay motionless until she perceived that the Sioux would not come down on them en-masse, when she raised her father‟s loaded gun and killed a warrior who was running to get her father‟s scalp, thus knowing she had killed the slayer of her father, as no Indian would come for a scalp he had not earned himself. The Sioux were now on the retreat and their flank and rear were being threatened, the girl picked up her father‟s ammunition pouch, loaded the rifle, and started in pursuit. Stopping at the body of her dead Sioux she lifted the scalp and tucked it under her belt. She continued the chase with the men of her band, and it was two days before they returned to the women and children, whom they had left on the trail, and when the brave little heroine returned she had added two scalps to the one she started with.

She is now living, or was, but a few years ago, near Rice Lake, Wis., the wife of Edward Dingley, who served in the war of rebellion from the time of the first draft of soldiers to the end of the war. She became his wife in 1857, and lived with him until he went into the service, and at this time had one child, a boy. A short time after he went to the war news came that all the party that had left Bayfield at the time he did as substitutes had been killed in battle, and a year or so after, his wife, hearing nothing from him, and believing him dead, married again. At the end of the war Dingley came back and I saw him at Bayfield and told him everyone had supposed him dead and that his wife had married another man. He was very sorry to hear this news and said he would go and see her, and if she preferred the second man she could stay with him, but that he should take the boy. A few years ago I had occasion to stop over night with them. And had a long talk over the two marriages. She told me the circumstances that had let her to the second marriage. She thought Dingley dead, and her father and brother being dead, she had no one to look after her support, or otherwise she would not have done so. She related the related the pursuit of the Sioux at the time of her father‟s death with much tribal pride, and the satisfaction she felt at revenging herself upon the murder of her father and kinsmen. She gave me the particulars of getting the last two scalps that she secured in the eventful chase. The first she raised only a short distance from her place of starting; a warrior she espied skulking behind a tree presumably watching for some one other of her friends that was approaching. The other she did not get until the second day out when she discovered a Sioux crossing a river. She said: “The good luck that had followed me since I raised my father‟s rifle did not now desert me,” for her shot had proved a good one and she soon had his dripping scalp at her belt although she had to wade the river after it.”

At this point, this is all I have to offer on the story of Hanging Cloud the ogichidaakwe. I’ll be sure to update if I stumble across anything else, but for now, we’ll have to be content with these two contradictory stories.