Le Boeuf et Le Pain: Alexis Cadotte’s letter to Chief Buffalo and Manabozho, January 11, 1840

April 30, 2024

By Leo

This was supposed to be a short post highlighting an interesting document with some light analysis of the relationship between the Ojibwe chiefs at La Pointe and the ones on the British-Canadian side of Sault Ste. Marie. It’s grown into an unwieldy musing on the challenges of doing what we do here at Chequamegon History. If you are only interested in the document, here it is:

(Copy)

Sault St. Maries 11 Janvier 1840

A Msr. le Beuf chef au tête à la pointe}

Cher grand-père,

Nous avons Recu votre par le darnier voyage des Barque de la Société. Ala nous avons apris la mort de votre fils qui nous a cose Boucup de chagrain, nous avons aussi bien compri le reste de votre, nous somme satisfait de n avoir vien neuf à la tréte de la pointe plus que vous ave vien neuf vous même nous somme de plus contents de vous pour L année prochaine arrive ici à votre endroit tachez de va espere promilles que vous nous fait que nous ayon la satisfaction an vous voyent de vous a tete cas il nous manque des Beuf ici, nous isperon que vous vous l espère Sanger il bon que vous venite a venire aucure une au Sault est Boucoup change de peu que la vie du Le Pain ne pas ici peu etre quil vous quelque chose pas cette ocation espre baucoup de vous voir l’etee prochienne, nous avons rien de particulier a vous mas que si non que faire. Baucoup a vous contée car il y a de grande nouvelles qui regarde toute votre nation et la nôtre tachez de nous faire réponse à notre lettre par le même.

2 Toute notre famille sont ans asse santé et Madame Birron qui est malade depui un mois et demi, un autre de ce petit garcon malade de pui cinq jour. Mon cher grand père nous finisson au vous Souhaitons toute sorte de Bonne prospérité croyez moi pour la vis votre tautre et efficionne fils

Signed Alexi Cadotte

Mon nomele Mainabauzo,

Je vous fais le meme Discours a vous dece que je vien de dire ici au Bouf. Il faut absolument que vous vene nous voir ici particulièrement votre patron qui moi meme et mon fils il y a un an l’été Darnier je vous espère au aspeill à la pointe nous avant neuf après ent la réponce du contenu de notre di proure si vous vere nous rejoindre nous iron ansemble à l ile Manito Wanegue au présent Anglois Car les Mitif se toi en Britanique resoive à présent comme les Sauvage vous dire à votre Jandre La pluve blanche que nous avon pas compri la lettre mon chère on ete je fini au vous enbrassan toute croyez moi pour la vie votre neveux.

signed Alexis Cadotte

Toute la famille vous fon des complément. Complement tous nous parans particulièrement

signed Cadotte

If you only want the translation, keep scrolling. If you want the story, read on.

Several years ago, I received a copy of this letter from Theresa Schenck, author and editor of several of the most important recent books on Ojibwe history. She knew that I was interested in the life of Chief Buffalo of La Pointe and described it as a charming letter written to Buffalo by one of his Cadotte relatives at Sault Ste. Marie. Dr. Schenck made a special point of telling me there were jokes inside.

My immediate reaction was what many of you might be thinking, “But I don’t speak French!” Her response was very matter-of-fact, “Well you need to know French if you’re going to study Lake Superior history. Learn French.”

During the pandemic, I finally got to it, and according to Duolingo, I now have the equivalent of three years of high-school French even though I can’t speak it at all. I can read enough to decipher Alexis Cadotte’s handwriting, though, and get the words into Google Translate. That’s where we hit a second problem.

The French that Cadotte uses in 1840 is not the same French that Duolingo and Google Translate use in 2023. Ojibwe was almost certainly the mother tongue of Alexis, who was born at Lac Courte Oreilles around 1799, but later he would have picked up French, and later still English. However, the French spoken by Cadotte and his contemporaries was commonly called patois or Metis/Michif (Alexis spells it “Mitif”), and was a mixture of French, Ojibwe, and Cree. This letter shows that Cadotte had some formal education, but even formal Quebec French deviates significantly from modern standard French. This is all to say that the letter is filled with non-standard spellings and vocabulary.

Lacking confidence in my translation, I shared the letter with Patricia McGrath, a distant relative of Alexis’ and Canadian Chequamegon History reader, and with the help of her her cousin Stéphane, we combined to produce this:

(Copy)

Sault St. Maries 11 January 1840

To Mr. Le Boeuf, Head chief at La Pointe}

Dear grandfather,

We received your communication at the last arrival of the Company Boat. It was then that we learned of the death of your son, which left us in grief. We also understood the rest of your message. You are more satisfied to have us come again to the head of “La Pointe” than for you to come here yourself. We are more than happy to see you next year, when we arrive at your place, but we hold out hope for the promise you made to give us the satisfaction of seeing you here in person. We are missing some Beef here. We hope you agree. My blood, it would be good that you should come here soon. There are many changes at the Sault. One is that Le Pain does not live here anymore. Perhaps there is something wrong with the timing. We hope to see you next summer. We have nothing new in particular to say to you. Much has been said to you because there is great news, which concerns your entire nation and ours. Try to respond to our letter in the same way.

2 Our whole family is in good health but for Madame Birron, who has been ill for a month and a half, along with one of her little boys who has been sick for five days. My dear grandfather, we end by wishing you all kinds of good prosperity. Believe me, for life, your affectionate other son

Signed Alexi Cadotte

My namesake Mainabauzo,

I am making the same speech to you as I have just said here to Le Boeuf. You absolutely have to come see us here, especially your chief, who was with me and my son a year ago last summer. I hope you will welcome us to La Pointe. Please respond to the content of our report if you wish to join us, go together to Manito Wanegue Island and receive the presents of the English, because the Mitif, if you are in British territory, now receive them as the Indians do. You tell your son-in-law White Plover that we didn’t understand his letter. My dear one, we have finished greeting you all. Believe me, for life, your nephew.

signed Alexis Cadotte

The whole family sends salutations, especially the parents.

signed Cadotte

Food puns? Long, circular statements that seem to only say “come visit your relatives.” What the heck is going on here? Another letter, written by Alexis Cadotte on the same day, sheds some light.

Sault Ste Marie, January 11 1840

Cadotte clarifies here that Le Pain is yet another food pun–this time on Le Pin, or the Pine. Zhingwaakoons (Pine) was a powerful Ojibwe chief on the British side of the Sault. The Lagardes and their in-laws, the LeSages were Metis trading families in the region.

Cadotte clarifies here that Le Pain is yet another food pun–this time on Le Pin, or the Pine. Zhingwaakoons (Pine) was a powerful Ojibwe chief on the British side of the Sault. The Lagardes and their in-laws, the LeSages were Metis trading families in the region.Eustache Legarde

My dear friend,

I write you this to wish you good health & to send my compliments to all our friends. I make known to you the result of the counsel we held yesterday with the Bread.* The answer is now received. The English Government has accepted all the applications of the Indians in favor of the half breeds, so the half breeds will begin to receive presents of the Government next summer. Furthermore the Government promises to supply the Indians with all things necessary to cultivate the soil. Besides all this the Government promises to build houses for the Half breeds, and to let them have a Forge. The Bread (Pine) is looking for a convenient place to build a half breed village. I recommend that you tell this news to all who are concerned in this matter. I am very sorry to inform you that your youngest nephew died some days ago. The rest of Sages family appear to be well. I close wishing you all kind of prosperity.

Believe me your friend

Alexis Cadotte

*Pine

From this letter, it becomes clear who “The Bread” is. It also shows that Cadotte’s motivation for writing Buffalo and Manabozho goes beyond simply missing his relatives. He wants the La Pointe chiefs to maintain their relationship with the British government and potentially relocate to Canada permanently.

By 1840, the Lake Superior Ojibwe were beginning to feel the heat of American colonization. The influx of white settlers (aside from in the lumber camps on the Chippewa and St. Croix) had yet to begin in earnest, but missionaries had settled in Ojibwe villages, and their presence was far from universally welcomed. The fur trade was in steep decline, and the monopolistic American Fur Company was well into its transition into a business model based on debts, land cessions, and annuity payments (what Witgen calls the political economy of plunder). The Treaty of St. Peters (1837) further divided Ojibwe society, creating deep resentments between the Lake Superior Bands and the Mississippi and Leech Lake Bands. Resentments also grew between the “full bloods” who were able to draw annuities from treaties, and the “mix-bloods,” who did not receive annuities but were able to use American citizenship and connections to the fur company for continued economic gain post-fur trade. Finally, the specter of removal hung over any Indian nation that had ceded its lands. The Lake Superior Ojibwe were well aware of the fates of the Meskwaki-Sauk, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Ho-Chunk and other nations to their south.

Keeping up relations with the British offered benefits beyond just the material goods described by Cadotte. It forced the American government to remain on friendly terms with the Ojibwe to prove that they were a more benevolent people than the British. In negotiations, the Ojibwe leadership often reminded the U.S. of the generosity of the “British Father.” Canadian territory also offered a potential refuge in the event of forced removal. The Jay Treaty (1796) had drawn a line through Lake Superior on European maps, but in 1840, there was still Ojibwe territory on both sides of the lake, and the people of La Pointe had many relatives on both sides of the Soo.

Zhingwaakoons was a fierce advocate of Ojibwe self-determination, and Cadotte’s letter shows that Little Pine (a.k.a. The Bread) was beginning to implement his scheme to concentrate as many Ojibwe people as possible at Garden River. If he could add the Lake Superior bands on the American side to his number, it would strengthen his position with the British-Canadian authorities. The British were open to the idea, as the Ojibwe provided a military buffer against American aggression in the event of another war between the United States and the United Kingdom. The more Ojibwe on the border in Canada, the stronger the buffer.

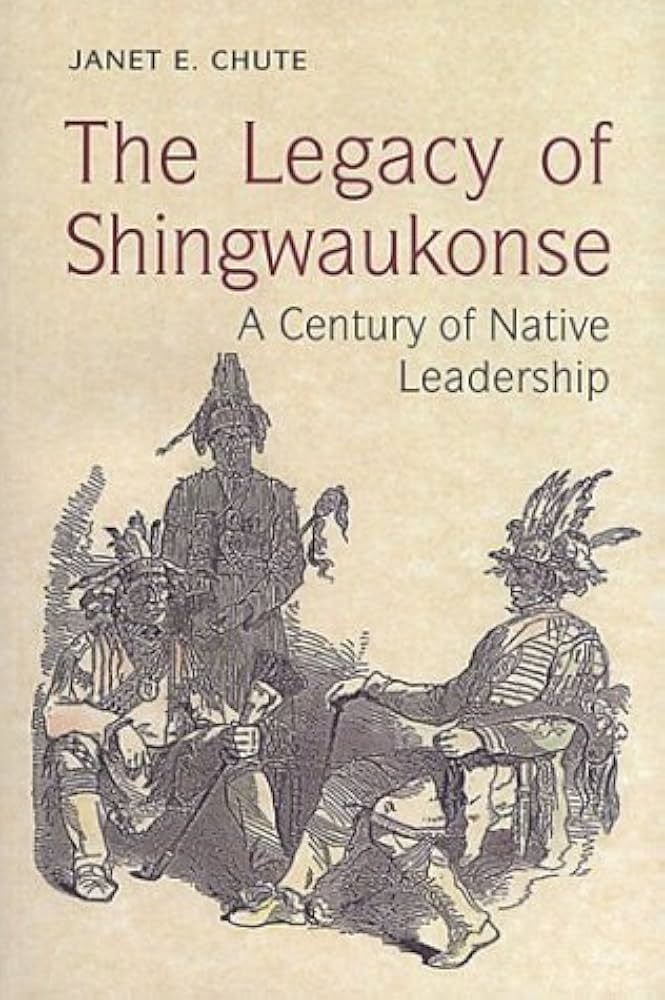

If you are interested in these topics, I strongly recommend this book:

I had already been writing Chequamegon History for a few years before I discovered The Legacy of Shingwaukonse: A Century of Native Leadership by Janet E. Chute through multiple fascinating references in Paap’s Red Cliff, Wisconsin. It was a nice wakeup call. It’s easy to get into the rut of only looking at records from the U.S. Government, the fur companies, and the missionary societies. There are other sources out there, of which the material coming from the British side of the Sault is a one example.

One of the puzzling things about the Alexis Cadotte letter is that it’s written in French. The common mother tongue of Cadotte, Buffalo, and Manabozho would have been Ojibwe. Granted, 1840 was a little early for Father Baraga’s Ojibwe writing system to have caught on, and Cadotte wouldn’t have known Sherman Hall’s system. In the following decades, letters in the Ojibwe language would become slightly more common, but at that early point, Cadotte may have still regarded Ojibwe as strictly a spoken language. It’s also possible that French offered a little more secrecy than English. Potential translators on Madeline Island would be other Metis (or Canadien heads of Metis families), whose goals would align more with Cadotte’s than with the United States Government’s. However, this is speculation.

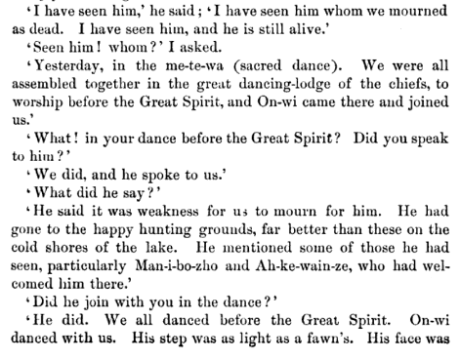

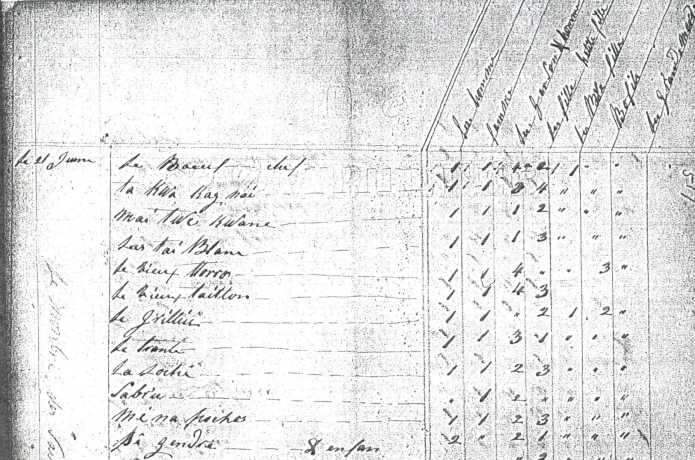

Chief Buffalo is probably referenced more than any other individual on Chequamegon History, but we haven’t had a lot to say about Manabozho. The truth is, we don’t have a lot of sources about him. From another French document, from another Cadotte, we know that he was living at La Pointe in 1831:

This 1831 census of La Pointe was taken by Big Michel Cadotte (first cousin of Alexis’ father, Little Michel Cadotte), and we see Le Boeuf listed as chief of the band. Me-na-poch-o is the eleventh household listed, and “se gendre,” an unidentified son-in-law and grandson are directly beneath him. 1 man (des hommes) 1 wife (des femmes) 2 sons (des hommes & garsons) and 3 daughters or granddaughters (des filles et petite filles) were living in Manabozho’s household.

We also see his name among the two La Pointe chiefs who signed the Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1825).

“Gitshee X Waiskee or Le Bouf of La pointe Lake superior” “Nainaboozho X of La pointe Lake Superior” Manabozho is named after the famous trickster and rabbit manitou who William Warren called “the universal uncle of the An-ish-in-aub-ag.” The initial consonant in the name of this powerful being could be an “M,” “N,” or “W” depending on grammatical context and regional dialect. Spellings in La Pointe documents from this era use all three.

And from the testimony from the 1839 payments at La Pointe, to mix-bloods and traders under the third and fourth articles of the Treaty of St. Peters (1837), we can see that Manabozho and Buffalo had a history of working with Alexis’ family. This testimony was given in favor of Alexis’ brother Louis’ claim against the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe:

Heirs of Michel Cadotte a British Subject

To amount of private property destroyed at the post occupied by Mr. Louis Corbin in the year 1809 or 1810, the claimant being then absent from said post but had left there his private property and that of his deceased father, Estimated at Eight hundred Dollars– $800.00

Louis Cadotte

His X mark

La Pointe 30th August 1838

G Franchere } witnesses

Eustache Roussain

N.B. The papers and books were all destroyed

L x C

We the undersigned Pé-jé-ké, chief of the Chippewa Tribe of Indians, residing at La Pointe and Mé-na-bou-jou, also of La pointe but formerly residing at Lac Court Oreil, do hereby certify that, to our knowledge, to the best of our recollection, about the year 1809 or 1810 the above claimant and his father had who was an Indian trader at said Lac Court Oreil, had their property destroyed by a band of Chippewa Indians, whilst said claimant was absent as well as his late father who had gone to Michilimackinac to get his usual years supply of Goods for the prosecution of his trade, which we firmly believe that the amount of Eight hundred Dollars as specified in the above account, is just and reasonable, and ought to be allowed. In witness whereof we have signed these presents the same having been read over and interpreted to us by Eustache Roussain. La Pointe this 30th day of August 1838.

Pé-jé-ké his X mark The Buffalo

Mé-na-bou-jo his X mark

This claim is for property destroyed by followers of the Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa on the Cadotte outfit post of Jean Baptiste Corbine at Lac Courte Oreille. Tenskwatawa, the brother of Tecumseh, had many followers in this region. Chequamegon History covered this incident, and Chief Buffalo’s role, back in 2013.

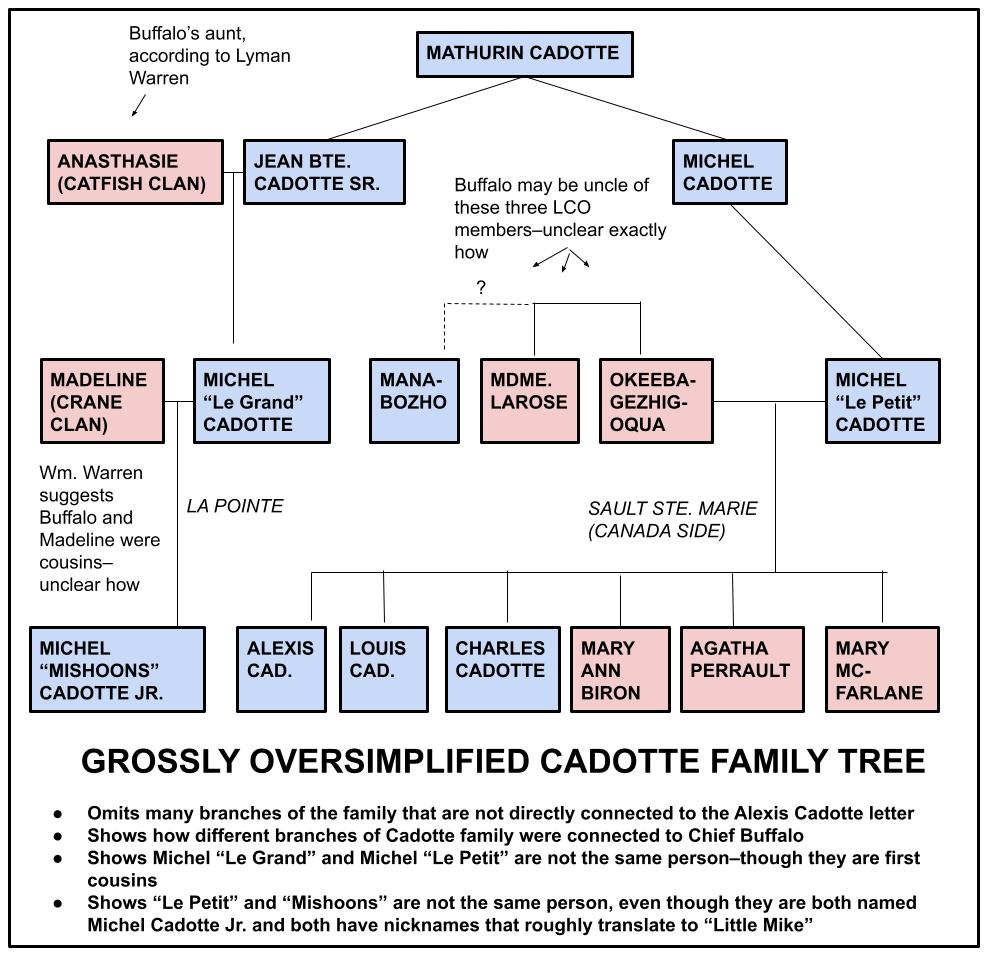

In the general mix blood claims, published in Theresa Schenck’s All Our Relations: Chippewa Mixed Bloods and the Treaty of 1837 (Amik Press; 2009), we learn more the exact relationship of Manabozho and Buffalo to the Cadottes. The former is their uncle, and the latter is their great uncle. Whether that makes the two men closely related to each other isn’t clear. The claims don’t say if they are blood relatives or in-laws of the Cadotte’s mother, Okeebagezhigoqua. However, if Manabozho was born into the band of Buffalo’s grandfather, Andegwiiyaas, and was living at Lac Courte Oreilles at the dawn of the 19th century, this would be consistent with a pattern of the “La Pointe Bands” of that era who were associated with La Pointe but living and hunting inland.

I should note that in Alexis Cadotte’s letter, he refers to Buffalo as grandpere rather than grand oncle. Don’t get too hung up on this. I am no expert on traditional Ojibwe conceptions of kinship other than to say they can be very different from European kinship systems and that it would not be at all unusual for a grandnephew to address his granduncle with the honorific title of grandfather.

From Francois, Joseph, and Charles LaRose claim

“Their Uncles are now residing at the Point, one of them is a respectable full blood Chippewa named Na-naw-bo-zho. The chief at La Pointe called Buffalo is their grand uncle. Their mother is a sister to the Cadottes. (Schenck, pg. 86)

From claims of Alexis, Louis, and Charles Cadotte, Mary Ann Biron, Agathe Perrault, and Mary McFarlane

“[Their] father was Michael Cadotte, a French trader in the ceded country, where he married a woman of the Ojibwa nation from Lake Coute Oreille named O-kee-ba-ge-zhi-go-qua.” (Schenck pg. 41)

“Five of the Earliest Indian Inhabitants of St. Mary’s Falls, 1855: 1) Louis Cadotte, John Boushe, Obogan, O’Shawan, [Louis] Gurnoe If this caption is to be trusted, andcaptions aren’t always to be trusted, there is a man named Louis Cadotte in this photo who would be about the right age to be Alexis’s brother. I read the numbers to indicate that he’s the man in the upper right. Others have interpreted this photo differently.

Sometimes different people have the same name. Very few of us can be expected to be fluent in English, Ojibwe, and regional dialects and creoles of 18th-century Quebec French (that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try!). It’s not only language. Subtle differences of religious and cultural understanding can skew the way a source is interpreted. Sources can be hard to come by, contradictory, misinterpreted by other researchers, or in unexpected places. Sometimes you stumble upon a previously unknown source that throws a monkey wrench into all your previous conclusions.

All this means that if you’re going to do this research, expect that you are going to have to humble yourself, admit mistakes, and admit when you might be pretty sure of something but not absolutely certain. My next few posts will explore these concepts further.

As always, thanks for reading,

Leo

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

P.S. Speaking of monkey wrenches…

Facts, Volumes 2-3. Facts Publishing Company. Boston, 1883. Pg. 66-68.

At Chequamegon History, we try to use reliable narrators. We try to use sources from before 1860. First-hand information is preferable to second or third-hand information, and we do not engage in much speculation or evaluation when it comes to questions of spirituality. This is especially true of traditional Ojibwe spirituality, of which we know very little.

Therefore, I strongly considered leaving out this excerpt from FACTS Prove the Truth of Science, and we do not know by any other means any Truth; we, therefore, give the so-called Facts of our Contributors to prove the Intellectual Part of Man to be Immortal. From what I can tell, this bizarre 1883 publication is dedicated to stories of “Spiritualism,” the popular late 19th-century pseudoscience (think the earliest Ouija boards, Rasputin, etc.). If you haven’t already guessed from the the length of the title, FACTS… appears to have been pretty fringe even for its own time. Take it for what it is.

Florantha (above) and Granville Sproat were more than just teachers with funny names. They wrote about 1840s La Pointe. The sex scandal that led to their departure sent a ripple through the Protestant mission community. (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Granville Sproat, however, was a real person–a schoolteacher in the Protestant mission at La Pointe. His wife, Florantha, is quoted near the top of this post, referencing the death of Chief Buffalo’s sons. The Sproats’ impact on this area’s history is pretty minimal, though they did produce a fair amount of writing in the late 1830s and early ’40s. Perhaps the most interesting part of their Chequamegon story is their abrupt departure from the Island after Granville became embroiled in what I believe is Madeline Island’s earliest recorded gay sex scandal. Since I can’t end on that cliff hanger, and it might be several years before I get to that particular story, you can learn more from Bob Mackreth’s thorough and informative treatment of Florantha’s life on youtube.

This post has really gone off the rails. Thanks for sticking with it, and as always, thanks for reading. ~LF

Special thanks to Theresa, Patricia, and Stephane for making this post possible.

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Island Museum Painting

November 9, 2013

This post is one of several that seek to determine how many images exist of Great Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855. To learn why this is necessary, please read this post introducing the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

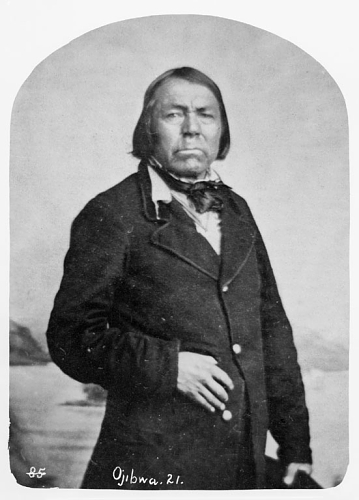

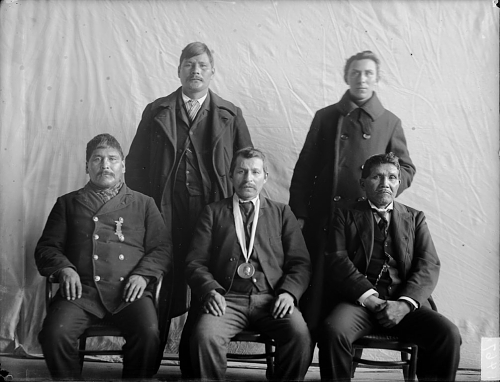

(Wisconsin Historical Society, Image ID: 3957)

If any image has been as closely tied to Chief Buffalo from La Pointe as the the bust of the Leech Lake Buffalo in Washington, it is an image of a kindly but powerful-looking man in a U.S. Army jacket with a medal around his neck. This image appears on the cover of the 1999 edition of Walleye Warriors, by treaty-rights activist Walter Bresette and Rick Whaley. It is identified as Buffalo in both Ronald Satzʼs Chippewa Treaty Rights, and Patty Loewʼs Indian Nations of Wisconsin. It occupies a prominent position in the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society and hangs in the Madeline Island Museum, but in spite of the enduring popularity of this image, very little is known about it.

As I have not been able to thoroughly examine the originals or find any information whatsoever about their creation, chain of custody, or even when they entered the Historical Society’s collections, this post will be the most speculative of the Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

There are two versions of this image. One appears to be an early type of photograph. The Wisconsin Historical Society describes it as “over-painted enlargement, possibly from a double-portrait (possibly an ambrotype).” I’ve been told by staff that the painting that hangs in the museum is a copy of this earlier version.

A photograph of the original image is in the Societyʼs archives as part of the Hamilton Nelson Ross collection. On the back of the photo, “Chief Buffalo, Grandson of Great Chief Buffalo” is handwritten, presumably by Ross. This description would seem to indicate that the image shows one of Chief Buffaloʼs grandsons. However, we need to be careful trusting Ross as a source of information about Buffalo’s family.

Ross, a resident of Madeline Island, gathered volumes of information on his home community in preparation for his book La Pointe Village Outpost on Madeline Island (1960). Although the book is exhaustively researched and highly detailed about the white and mix-blooded populations of the Island, it contains precious little information about individual Indians. The image of Buffalo is not in the book. In fact, the only mention of the chief comes in a footnote about his grave on page 177:

O-Shaka was also known as O-Shoga and Little Buffalo, and he was the son of Chief Great Buffalo. The latter’s Ojibway name was Bezhike, but he was also known as Kechewaishkeenh–the latter with a variety of spellings. Bezhike’s tombstone, in the Indian cemetery, has had the name broken off…

Oshogay was not Buffalo’s son (though he may have been a son-in-law), and he was not the man known as “Little Buffalo,” but until his untimely death in 1853, he seemed destined to take over leadership of Buffalo’s “Red Cliff” faction of the La Pointe Band. The one who did ultimately step into that role, however, was Buffalo’s son Jayjigwyong (Che-chi-gway-on):

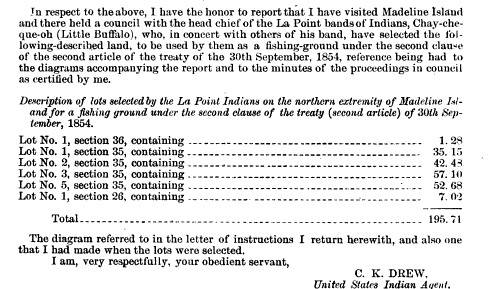

Drew, C.K. Report of the Chippewa Agency of Lake Superior. 26 Oct. 1858. Printed in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. 1858 (Digitized by Google Books)

We will return to Jayjigwyong later in the post, but for now, let’s examine the image itself.

The man in the picture wears an early 19th-century army jacket and a medal. This is consistent with the practices of Chief Buffalo’s day. The custom of handing out flags, jackets, and medals goes back at least to the 1700s with the French. The practice continued under the British and Americans as a way of recognizing certain individuals as chiefs and asserting imperial claims. For the chiefs, the items were symbolic of agreements and alliances. Large councils, treaty signings, and diplomatic missions were all occasions where they were given out. Buffalo had received medals and jackets from the British, and between 1820 and 1855, he took part in the negotiations of at least five treaties, many council meetings and annuity payments, visited Washington, and frequently went back and forth to the agency at Sault Ste. Marie. The United States Government favored Buffalo over the more forcefully-independent chiefs on the Ojibwe-Dakota frontier in Minnesota. Considering all this, it is likely that Buffalo received many jackets, flags, and medals from the Americans over the course of his long interaction with them. An excerpt from a letter by teacher Granville Sproat, who lived in the Lake Superior region in the 1830s reads:

Ke-che Be-zhe-kee, or Big Buffalo, as he was called by the Americans, was then chief of that band of Ogibway Indians who dwell on the south-west shores of Lake Superior, and were best known as the Lake Indians. He was wise and sagacious in council, a great orator, and was much reverenced by the Indians for his supposed intercourse with the Man-i-toes, or spirits, from whom they believed he derived much of his eloquence and wisdom in governing the affairs of the tribe.

“In the summer of 1836, his only son, a young man of rare promise, suddenly sickened and died. The old chief was almost inconsolable for his loss, and, as a token of his affection for his son, had him dressed and laid in the grave in the same military coat, together with the sword and epaulettes, which he had received a few months before as a present from the great father [president] at Washington. He also had placed beside him his favorite dog, to be his companion on his journey to the land of souls (qtd. in Peebles 107).

It is strange that Sproat says Buffalo had only one son given that his wife Florantha Sproat references another son in her description of this same funeral, but sorting out Buffalo’s descendants has never been an easy task. There are references to many sons, daughters, and wives over the course of his very long life.

Another description from the Treaty of 1842 reads:

On October 1 Buffalo appeared, wearing epaulettes on his shoulders, a hat trimmed with tinsel, and a string of bear claws about his neck (Dietrich qtd. in Paap 177-78).

From these accounts we know that Buffalo had these kinds of coats, but dozens of other Ojibwe chiefs would have had similar ones, so the identification cannot be made based on the existence of the coat alone. Consider Naaganab at the 1855 annuity payment:

Na-gon-ub is head chief of the Fond du Lac bands; about the age of forty, short and close built, inclines to ape the dandy in dress, is very polite, neat and tidy in his attire. At first, he appeared in his native blanket, leggings, &c. He soon drew from the Agent a suit of rich blue broadcloth, fine vest, and neat blue cap,–his tiny feet in elegant finely-wrought moccasins. Mr. L., husband of Grace G., with whom he was a special favorite, presented him with a pair of white kid gloves, which graced his hands on all occasions. Some two or three years since, he visited Washington, a delegate from his tribe. Upon this journey, some one presented him with a pair of large and gaudy epaulettes, said to be worth sixty dollars. These adorned his shoulders daily; his hair was cut shorter than their custom. He quite inclined to be with, and to mingle in the society, of the officers, and of white men. These relied on him more, perhaps, than any other chief, for assistance among the Chippewas… (Morse pg. 346)

Portrait of Naw-Gaw-Nab (The Foremost Sitter) n.d by J.E. Whitney of St. Paul (Smithsonian)

In many ways, this description of Naaganab fits the image better than any description of Buffalo I’ve seen. The man is dressed in European fashion, has short hair, and large epaulets. We also know that Naaganab had presidential medals, since he continued to display them until his death in the 1890s. The image isn’t dated, but if it truly is an ambrotype, as described by the State Historical Society, that is a technique of photography used mostly in the late 1850s and 1860s. When Buffalo died in 1855, he was reported to be in his nineties. Naaganab would have been in his forties or fifties at that time. To me, the man in the image appears middle-aged rather than elderly.

So is Naaganab the man in the picture? I don’t think so. For one, there are multiple photographs of the Fond du Lac chief out there. The clothing and hairstyle largely match, but the face is different. The other thing to consider is that this image, to my knowledge, has never been identified with Naaganab. Everything I’ve ever seen associates it with the name Buffalo.

However, there is a La Pointe chief who was a political ally of Naaganab, also dressed in white fashion, could have easily owned a medal and fancy army jacket, would have been middle-aged in the 1850s, and bore the English name of “Buffalo.” It was Jayjigwyong, the son of Chief Buffalo.

Alfred Brunson recorded the following in 1843:

(pg. 158) From elsewhere in the account, we know that the “fifty” year-old is Chief Buffalo. This is odd, as most sources had Buffalo in his eighties at that time.

(pg. 191)

Unlike his famous father, Jayjigwyong, often recorded as “Little Buffalo,” is hardly remembered, but he is a significant figure in the history of our region. He was a signatory of the treaties of 1837, 1847, and 1854. He led the faction of the La Pointe Band that felt that rapid assimilation represented the best chance for the Ojibwe to survive and keep their lands. In addition to wearing white clothing and living in houses, Jayjigwyong was Catholic and associated more with the mix-blooded population of the Island than with the majority of the La Pointe band who sought to maintain their traditions at Bad River.

According to James Blackbird, whose father Makadebineshiinh (Black Bird) led the Bad River faction, it was Jayjigwyong who chose where the Red Cliff reservation was to be. James Blackbird, about eleven or twelve at the time of the Treaty of 1854, would have known both the elder and younger Buffalo.

Statement of James Blackbird in the Matters of the Allotments on the Bad River Reservation, Wis. Odanah, 23 Sep. 1909. Published in Condition of Indian affairs in Wisconsin: hearings before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, [61st congress, 2d session], on Senate resolution, Issue 263. United States Congress. 1910. Pg. 202.

The younger Blackbird, offered more information about the younger Buffalo in another publication.

Even though it is from 1915, there are a number of items in this account that if accurate are very relevant to pre-1860 history. For this post, I’ll stick to the two that involve Jayjigwyong. This is the only source I’ve ever seen that refers to Chief Buffalo marrying a white woman captured on a raid. This lends further credence to the argument explored by Dietrich and Paap that Chief Buffalo fought in the Ohio Valley wars of the 1790s. It also begs the question of whether being perceived as a “half-breed” had an impact on Jayjigwyong’s decisions as an adult.

James Blackbird (seated) with interpreter John Medeguan in Washington, 1899. (Photo by Gil DeLancy, Smitsonian Collections)

The other interesting part of the statement is that James Blackbird says his father was pipe carrier for Jayjigwyong. This would be surprising as Blackbird was the most influential La Pointe chief after the death of Buffalo. However, this idea of Jayjigwyong, inheriting the symbolic “head chief” title from his father can also be seen in the following document from 1857:

Published in Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior. Office of Indian Affairs. 1882. pg. 299. (Digitized by Google Books)

Today the fishing ground at the tip of Madeline Island is now considered part of the Bad River Reservation, but it was the Red Cliff chief who picked it out. This shows how the political division of the La Pointe Band into two distinct entities took several years to take shape, and was not an abrupt split at the Treaty of 1854.

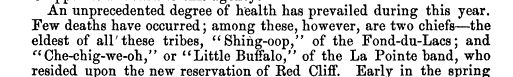

Jayjigwyong continued to be regarded as a chief until his death in 1860:

Drew, C.K. Report on the Chippewas of Lake Superior. Red Cliff Agency. 29 Oct. 1860. Pg. 51 of Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Bureau of Indian Affairs. 1860. (Digitized by Google Books). Zhingob (Shing-oop) was Naaganab’s cousin and the hereditary chief at Fond du Lac. Also known as Nindibens, he figures prominently in Edmund F. Ely’s journals of the mid-1830s.

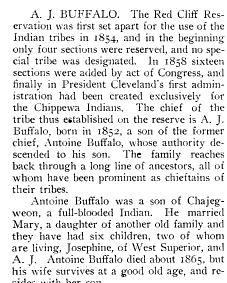

Future generations of the Buffalo family continued to be looked at as hereditary chiefs in Red Cliff, and sources can be found calling these grandsons and great-grandsons “Chief Buffalo.”

J.H. Beers and Co. Commemorative Biographical Record of the Upper Lake Region. 1905. Pg. 379. (Digitized by Google Books).

Antoine brings us full circle. If we remember, Hamiton Ross wrote that the image of the chief in the army jacket was Chief Buffalo’s grandson. And while we don’t know where Ross got his information, and he made mistakes about Buffalo’s family elsewhere, we have to consider that Antoine Buffalo was an adult by 1852 and he could have inherited his father’s, or grandfather’s, medal and coat.

The Verdict

Although we’ve uncovered several lines of inquiry for this image, all the evidence is circumstantial. Until we know more about the creation and chain of custody, it’s impossible to rule Chief Buffalo in or out. My gut tells me it’s Buffalo’s son, Jajigwyong, but it could be his grandson, Naaganab, or and entirely different chief. We don’t know.