In the Fall of 1850, the Lake Superior Ojibwe (Chippewa) bands were called to receive their annual payments at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi River. The money was compensation for the cession of most of northern Wisconsin, Upper Michigan, and parts of Minnesota in the treaties of 1837 and 1842. Before that, payments had always taken place in summer at La Pointe. That year they were switched to Sandy Lake as part of a government effort to remove the entire nation from Wisconsin and Michigan in blatant disregard of promises made to the Ojibwe just a few years earlier.

There isn’t enough space in this post to detail the entire Sandy Lake Tragedy (I’ll cover more at a later date), but the payments were not made, and 130-150 Ojibwe people, mostly men, died that fall and winter at Sandy Lake. Over 250 more died that December and January, trying to return to their villages without food or money.

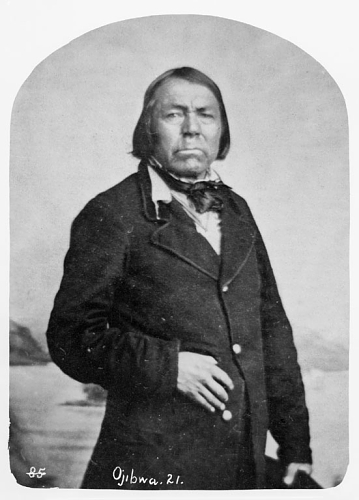

George Warren (b.1823) was the son of Truman Warren and Charlotte Cadotte and the cousin of William Warren. (photo source unclear, found on Canku Ota Newsletter)

If you are a regular reader of Chequamegon History, you will recognize the name of William Warren as the writer of History of the Ojibway People. William’s father, Lyman, was an American fur trader at La Pointe. His mother, Mary Cadotte was a member of the influential Ojibwe-French Cadotte family of Madeline Island. William, his siblings, and cousins were prominent in this era as interpreters and guides. They were people who could navigate between the Ojibwe and mix-blood cultures that had been in this area for centuries, and the ever-encroaching Anglo-American culture.

The Warrens have a mixed legacy when it comes to the Sandy Lake Tragedy. They initially supported the removal efforts, and profited from them as government employees, even though removal was completely against the wishes of their Ojibwe relatives. However, one could argue this support for the government came from a misguided sense of humanitarianism. I strongly recommend William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader by Theresa Schenck if you are interested in Warren family and their motivations. The Wisconsin Historical Society has also digitized several Warren family letters, and that’s what prompted this post. I decided to transcribe and analyze two of these letters–one from before the tragedy and one from after it.

The first letter is from Leonard Wheeler, a missionary at Bad River, to William Warren. Initially, I chose to transcribe this one because I wanted to get familiar with Wheeler’s handwriting. The Historical Society has his papers in Ashland, and I’m planning to do some work with them this summer. This letter has historical value beyond handwriting, however. It shows the uncertainty that was in the air prior to the removal. Wheeler doesn’t know whether he will have to move his mission to Minnesota or not, even though it is only a month before the payments are scheduled.

Sept 6, 1850

Dear Friend,

I have time to write you but a few lines, which I do chiefly to fulfill my promise to Hole in the Day’s son. Will you please tell him I and my family are expecting to go Below and visit our friends this winter and return again in the spring. We heard at Sandy Lake, on our way home, that this chief told [Rev.?] Spates that he was expecting a teacher from St. Peters’ if so, the Band will not need another missionary. I was some what surprised that the man could express a desire to have me come and live among his people, and then afterwards tell Rev Spates he was expecting a teacher this fall from St. Peters’. I thought perhaps there was some where a little misunderstanding. Mr Hall and myself are entirely undecided what we shall do next Spring. We shall wait a little and see what are to be the movements of gov. Mary we shall leave with Mr Hall, to go to school during the winter. We think she will have a better opportunity for improvement there, than any where else in the country. We reached our home in safety, and found our families all well. My wife wishes a kind remembrance and joins me in kind regards to your wife, Charlotte and all the members of your family. If Truman is now with you please remember us to him also. Tomorrow we are expecting to go to La Pointe and take the Steam Boat for the Sault monday. I can scarcely realize that nine years have passed away since in company with yourself and Pa[?] Edward[?] we came into the country.

Mary is now well and will probably write you by the bearer of this.

Very truly yours

L. H. Wheeler

By the 1850s, Young Hole in the Day was positioning himself to the government as “head chief of all the Chippewas,” but to the people of this area, he was still Gwiiwiizens (Boy), his famous father’s son. (Minnesota Historical Society)

By the 1850s, Young Hole in the Day was positioning himself to the government as “head chief of all the Chippewas,” but to the people of this area, he was still Gwiiwiizens (Boy), his famous father’s son. (Minnesota Historical Society)Samuel Spates was a missionary at Sandy Lake. Sherman Hall started as a missionary at La Pointe and later moved to Crow Wing.

Mary, Charlotte, and Truman Warren are William’s siblings.

The Wheeler letter is interesting for what it reveals about the position of Protestant missionaries in the 1850s Chequamegon region. From the 1820s onward, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent missionaries, mostly Congregationalists and Presbyterians from New England, to the Lake Superior Country. Their names, Wheeler, Hall, Ely, Boutwell, Ayer, etc. are very familiar to historians, because they produced hundreds of pages of letters and diaries that reveal a great deal about this time period.

Leonard H. Wheeler (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Ojibwe people reacted to these missionaries in different ways. A few were openly hostile, while others were friendly and visited prayer, song, and school meetings. Many more just ignored them or regarded them as a simple nuisance. In forty-plus years, the amount of Ojibwe people converted to Protestantism could be counted on one hand, so in that sense the missions were a spectacular failure. However, they did play a role in colonization as a vanguard for Anglo-American culture in the region. Unlike the traders, who generally married into Ojibwe communities and adapted to local ways to some degree, the missionaries made a point of trying to recreate “civilization in the wilderness.” They brought their wives, their books, and their art with them. Because they were not working for the government or the Fur Company, and because they were highly respected in white-American society, there were times when certain missionaries were able to help the Ojibwe advance their politics. The aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy was such a time for Wheeler.

This letter comes before the tragedy, however, and there are two things I want to point out. First, Wheeler and Sherman Hall don’t know the tragedy is coming. They were aware of the removal, and tentatively supported it on the grounds that it might speed up the assimilation and conversion of the Ojibwe, but they are clearly out of the loop on the government’s plans.

Second, it seems to me that Hole in the Day is giving the missionaries the runaround on purpose. While Wheeler and Spates were not powerful themselves, being hostile to them would not help the Ojibwe argument against the removal. However, most Ojibwe did not really want what the missionaries had to offer. Rather than reject them outright and cause a rift, the chief is confusing them. I say this because this would not be the only instance in the records of Ojibwe people giving ambiguous messages to avoid having their children taken.

Anyway, that’s my guess on what’s going on with the school comment, but you can’t be sure from one letter. Young Hole in the Day was a political genius, and I strongly recommend Anton Treuer’s The Assassination of Hole in the Day if you aren’t familiar with him.

I read this as “passed away since in company with yourself and Pa[?] Edward we came into the country.” Who was Wheeler’s companion when a young William guided him to La Pointe? I intend to find out and fix this quote. (from original in the digital collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society)

In 1851, Warren was in failing health and desperately trying to earn money for his family. He accepted the position of government interpreter and conductor of the removal of the Chippewa River bands. He feels removing is still the best course of action for the Ojibwe, but he has serious doubts about the government’s competence. He hears the desires of the chiefs to meet with the president, and sees the need for a full rice harvest before making the journey to La Pointe. Warren decides to stall at Lac Courte Oreilles until all the Ojibwe bands can unite and act as one, and does not proceed to Lake Superior as ordered by Watrous. The agent is getting very nervous.

Clement and Paul (pictured) Hudon Beaulieu, and Edward Conner, were mix-blooded traders who like the Warrens were capable of navigating Anglo-American culture while maintaining close kin relationships in several Ojibwe communities. Clement Beaulieu and William Warren had been fierce rivals ever since Beaulieu’s faction drove Lyman Warren out of the American Fur Company. (Photo original unknown: uploaded to findadagrave.com by Joan Edmonson)

Clement and Paul (pictured) Hudon Beaulieu, and Edward Conner, were mix-blooded traders who like the Warrens were capable of navigating Anglo-American culture while maintaining close kin relationships in several Ojibwe communities. Clement Beaulieu and William Warren had been fierce rivals ever since Beaulieu’s faction drove Lyman Warren out of the American Fur Company. (Photo original unknown: uploaded to findadagrave.com by Joan Edmonson)For more on Cob-wa-wis (Oshkaabewis) and his Wisconsin River band, see this post.

“Perish” is what I see, but I don’t know who that might be. Is there a “Parrish”, or possibly a “Bineshii” who could have carried Watrous’ letter? I’m on the lookout. (from original in the digital collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society)

Aug 9th 1851

Friend Warren

I am now very anxiously waiting the arrival of yourself and the Indians that are embraced in your division to come out to this place.

Mr. C. H. Beaulieu has arrived from the Lake Du Flambeau with nearly all that quarter and by an express sent on in advance I am informed that P. H. Beaulieu and Edward Conner will be here with Cob-wa-wis and they say the entire Wisconsin band, there had some 32 of the Pillican Lake band come out and some now are in Conner’s Party.

I want you should be here without fail in 10 days from this as I cannot remain longer, I shall leave at the expiration of this time for Crow Wing to make the payment to the St. Croix Bands who have all removed as I learn from letters just received from the St. Croix. I want your assistance very much in making the Crow Wing payment and immediately after the completion of this, (which will not take over two days[)] shall proceed to Sandy Lake to make the payment to the Mississippi and Lake Bands.

The goods are all at Sandy Lake and I shall make the entire payment without delay, and as much dispatch as can be made it; will be quite lots enough for the poor Indians. Perish[?] is the bearer of this and he can tell you all my plans better then I can write them. give My respects to your cousin George and beli[e]ve me

Your friend

J. S. Watrous

W. W. Warren Esq.}

P. S. Inform the Indians that if they are not here by the time they will be struck from the roll. I am daily expecting a company of Infantry to be stationed at this place.

JSW

Sources:

Schenck, Theresa M., William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Treuer, Anton. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul, MN: Borealis, 2010. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Maangozid’s Family Tree

April 14, 2013

(Amos Butler, Wikimedia Commons) I couldn’t find a picture of Maangozid on the internet, but loon is his clan, and “loon foot” is the translation of his name. The Northeast Minnesota Historical Center in Duluth has a photograph of Maangozid in the Edmund Ely papers. It is reproduced on page 142 of The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849 (2012) ed. Theresa Schenck.

In the various diaries, letters, official accounts, travelogues, and histories of this area from the first half of the nineteenth century, there are certain individuals that repeatedly find their way into the story. These include people like the Ojibwe chiefs Buffalo of La Pointe, Flat Mouth of Leech Lake, and the father and son Hole in the Day, whose influence reached beyond their home villages. Fur traders, like Lyman Warren and William Aitken, had jobs that required them to be all over the place, and their role as the gateway into the area for the American authors of many of these works ensure their appearance in them. However, there is one figure whose uncanny ability to show up over and over in the narrative seems completely disproportionate to his actual power or influence. That person is Maangozid (Loon’s Foot) of Fond du Lac.

Naagaanab, a contemporary of Maangozid (Undated, Newberry Library Chicago)

In fairness to Maangozid, he was recognized as a skilled speaker and a leader in the Midewiwin religion. His father was a famous chief at Sandy Lake, but his brothers inherited that role. He married into the family of Zhingob (Shingoop, “Balsam”) a chief at Fond du Lac, and served as his speaker. Zhingob was part of the Marten clan, which had produced many of Fond du Lac’s chiefs over the years (many of whom were called Zhingob or Zhingobiins). Maangozid, a member of the Loon clan born in Sandy Lake, was seen as something of an outsider. After Zhingob’s death in 1835, Maangozid continued to speak for the Fond du Lac band, and many whites assumed he was the chief. However, it was younger men of the Marten clan, Nindibens (who went by his father’s name Zhingob) and Naagaanab, who the people recognized as the leaders of the band.

Certainly some of Maangozid’s ubiquity comes from his role as the outward voice of the Fond du Lac band, but there seems to be more to it than that. He just seems to be one of those people who through cleverness, ambition, and personal charisma, had a knack for always being where the action was. In the bestselling book, The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell talks all about these types of remarkable people, and identifies Paul Revere as the person who filled this role in 1770s Massachusetts. He knew everyone, accumulated information, and had powers of persuasion. We all know people like this. Even in the writings of uptight government officials and missionaries, Maangozid comes across as friendly, hilarious, and most of all, everywhere.

Recently, I read The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849 (U. of Nebraska Press; 2012), edited by Theresa Schenck. There is a great string of journal entries spanning from the Fall of 1836 to the summer of 1837. Maangozid, feeling unappreciated by the other members of the band after losing out to Nindibens in his bid for leadership after the death of Zhingob, declares he’s decided to become a Christian. Over the winter, Maangozid visits Ely regularly, assuring the stern and zealous missionary that he has turned his back on the Midewiwin. The two men have multiple fascinating conversations about Ojibwe and Christian theology, and Ely rejoices in the coming conversion. Despite assurances from other Ojibwe that Maangozid has not abandoned the Midewiwin, and cold treatment from Maangozid’s wife, Ely continues to believe he has a convert. Several times, the missionary finds him participating in the Midewiwin, but Maangozid always assures Ely that he is really a Christian.

J.G. Kohl (Wikimedia Commons)

It’s hard not to laugh as Ely goes through these intense internal crises over Maangozid’s salvation when its clear the spurned chief has other motives for learning about the faith. In the end, Maangozid tells Ely that he realizes the people still love him, and he resumes his position as Mide leader. This is just one example of Maangozid’s personality coming through the pages.

If you’re scanning through some historical writings, and you see his name, stop and read because it’s bound to be something good. If you find a time machine that can drop us off in 1850, go ahead and talk to Chief Buffalo, Madeline Cadotte, Hole in the Day, or William Warren. The first person I’d want to meet would be Maangozid. Chances are, he’d already be there waiting.

Anyway, I promised a family tree and here it is. These pages come from Kitchi-Gami: wanderings round Lake Superior (1860) by Johann Georg Kohl. Kohl was a German adventure writer who met Maangozid at La Pointe in 1855.

When Kitchi-Gami was translated from German into English, the original French in the book was left intact. Being an uncultured hillbilly of an American, I know very little French. Here are my efforts at translating using my limited knowledge of Ojibwe, French-Spanish cognates, and Google Translate. I make no guarantees about the accuracy of these translations. Please comment and correct them if you can.

1) This one is easy. This is Gaadawaabide, Maangozid’s father, a famous Sandy Lake chief well known to history. Google says “the one with pierced teeth.” The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary translates it as “he had a gap in his teeth.” Most 19th-century sources call him Broken Tooth, La Breche, or Katawabida (or variants thereof).

2) Also easy–this is the younger Bayaaswaa, the boy whose father traded his life for his when he was kidnapped by the Meskwaki (Fox) (see post from March 30, 2013). Bayaaswaa grew to be a famous chief at Sandy Lake who was instrumental in the 18th-century Ojibwe expansion into Minnesota. Google says “the man who makes dry.” The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary lists bayaaswaad as a word for the animate transitive verb “dry.”

3) Presumably, this mighty hunter was the man Warren called Bi-aus-wah (Bayaaswaa) the Father in History of the Ojibways. That isn’t his name here, but it was very common for Anishinaabe people to have more than one name. It says “Great Skin” right on there. Google has the French at “the man who carries a large skin.” Michiiwayaan is “big animal skin” according to the OPD.

4) Google says “because he had very red skin” for the French. I don’t know how to translate the Ojibwe or how to write it in the modern double-vowel system.

5) Weshki is a form of oshki (new, young, fresh). This is a common name for firstborn sons of prominent leaders. Weshki was the name of Waabojiig’s (White Fisher) son, and Chief Buffalo was often called in Ojibwe Gichi-weshki, which Schoolcraft translated as “The Great Firstborn.”

6) “The Southern Sky” in both languages. Zhaawano-giizhig is the modern spelling. For an fascinating story of another Anishinaabe man, named Zhaawano-giizhigo-gaawbaw (“he stands in the southern sky”), also known as Jack Fiddler, read Killing the Shamen by Thomas Fiddler and James R. Stevens. Jack Fiddler (d.1907), was a great Oji-Cree (Severn Ojibway) chief from the headwaters of the Severn River in northern Ontario. His band was one of the last truly uncolonized Indian nations in North America. He commited suicide in RCMP custody after he was arrested for killing a member of his band who had gone windigo.

7) Google says, “the timber sprout.” Mitig is tree or stick. Something along the lines of sprouting from earth makes sense with “akosh,” but my Ojibwe isn’t good enough to combine them correctly in the modern spelling. Let me know if you can.

8) Google just says, “man red head.” Red Head is clearly the Ojibwe meaning also–miskondibe (OPD).

9) “The Sky is Afraid of the Man”–I can’t figure out how to write this in the modern Ojibwe, but this has to be one of the coolest names anyone has ever had.

**UPDATE** 5/14/13

Thank you Charles Lippert for sending me the following clarifications:

“Kadawibida Gaa-dawaabide Cracked Tooth

Bajasswa Bayaaswaa Dry-one

Matchiwaijan Mechiwayaan Great Hide

Wajki Weshki Youth

Schawanagijik Zhaawano-giizhig Southern Skies

Mitiguakosh Mitigwaakoonzh Wooden beak

Miskwandibagan Miskwandibegan Red Skull

Gijigossekot Giizhig-gosigwad The Sky Fears

“I am cluless on Wajawadajkoa. At first I though it might be a throat word (..gondashkwe) but this name does not contain a “gon”. Human skin usually have the suffix ..azhe, which might be reflected here as aja with a 3rd person prefix w.”

Kohl’s Kitchi-Gami is a very nice, accessible introduction to the culture of this area in the 1850s. It’s a little light on the names, dates, and events of the narrative political history that I like so much, but it goes into detail on things like houses, games, clothing, etc.

There is a lot to infer or analyze from these three pages. What do you think? Leave a comment, and look out for an upcoming post about Tagwagane, a La Pointe chief who challenges the belief that “the Loon totem [is] the eldest and noblest in the land.”

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings round Lake Superior. London: Chapman and Hall, 1860. Print.

Miller, Cary. Ogimaag: Anishinaabeg Leadership, 1760-1845. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2010. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Kah-puk-wi-e-kah: Cornucopia, Herbster, or Port Wing?

March 30, 2013

Official railroad map of Wisconsin, 1900 / prepared under the direction of Graham L. Rice, Railroad Commissioner. (Library of Congress) Check out Steamboat Island in the upper right. According to the old timers, that’s the one that washed away.

Not long ago, a long-running mystery was solved for me. Unfortunately, the outcome wasn’t what I was hoping for, but I got to learn a new Ojibwe word and a new English word, so I’ll call it a victory. Plus, there will be a few people–maybe even a dozen who will be interested in what I found out.

Go Big Red!

First a little background for those who haven’t spent much time in Cornucopia, Herbster, or Port Wing. The three tiny communities on the south shore have a completely friendly but horribly bitter animosity toward one another. Sure they go to school together, marry each other, and drive their firetrucks in each others’ parades, but every Cornucopian knows that a Fish Fry is superior to a Smelt Fry, and far superior to a Fish Boil. In the same way, every Cornucopian remembers that time the little league team beat PW. Yeah, that’s right. It was in the tournament too!

If you haven’t figured it out yet, my sympathies lie with Cornucopia, and most of the animosity goes to Port Wing (after all, the Herbster kids played on our team). That’s why I’m upset with the outcome of this story even though I solved a mystery that had been nagging me.

“A bay on the lake shore situated forty miles west of La Pointe…”

This all began several years ago when I read William W. Warren’s History of the Ojibway People for the first time. Warren, a mix-blood from La Pointe, grew up speaking Ojibwe on the island. His American father sent him to the East to learn to read and write English, and he used his bilingualism to make a living as an interpreter when he returned to Lake Superior. His mother was a daughter of Michel and Madeline Cadotte, and he was related to several prominent people throughout Ojibwe country. His History is really a collection of oral histories obtained in interviews with chiefs and elders in the late 1840s and early 1850s. He died in 1853 at age 28, and his manuscript sat unpublished for several decades. Luckily for us, it eventually was, and for all its faults, it remains the most important book about the history of this area.

As I read Warren that first time, one story in particular jumped out at me:

Warren, William W. History of the Ojibway Nation. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1885. Print. Pg. 127 Available on Google Books.

Pg. 129 Warren uses the sensational racist language of the day in his description of warfare between the Fox and his Ojibwe relatives. Like most people, I cringe at lines like “hellish whoops” or “barbarous tortures which a savage could invent.” For a deeper look at Warren the man, his biases, and motivations, I strongly recommend William W. Warren: the life, letters, and times of an Ojibwe leader by Theresa Schenck (University of Nebraska Press, 2007)

I recognized the story right away:

Cornucopia, Wisconsin postcard image by Allan Born. In the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society (WHI Image ID: 84185)

This marker, put up in 1955, is at the beach in Cornucopia. To see it, go east on the little path by the artesian well.

It’s clear Warren is the source for the information since it quotes him directly. However, there is a key difference. The original does not use the word “Siskiwit” (a word derived from the Ojibwe for the “Fat” subspecies of Lake Trout abundant around Siskiwit Bay) in any way. It calls the bay Kah-puk-wi-e-kah and says it’s forty miles west of La Pointe. This made me suspect that perhaps this tragedy took place at one of the bays west of Cornucopia. Forty miles seemed like it would get you a lot further west of La Pointe than Siskiwit Bay, but then I figured it might be by canoe hugging the shoreline around Point Detour. This would be considerably longer than the 15-20 miles as the crow flies, so I was somewhat satisfied on that point.

Still, Kah-puk-wi-e-kah is not Siskiwit, so I wasn’t certain the issue was resolved. My Ojibwe skills are limited, so I asked a few people what the word means. All I could get was that the “Kah” part was likely “Gaa,” a prefix that indicates past tense. Otherwise, Warren’s irregular spelling and dropped endings made it hard to decipher.

Then, in 2007, GLIFWC released the amazing Gidakiiminaan (Our Earth): An Anishinaabe Atlas of the 1836, 1837, and 1842 Treaty Ceded Territories. This atlas gives Ojibwe names and translations for thousands of locations. On page 8, they have the south shore. Siskiwit Bay is immediately ruled out as Kah-puk-wi-e-kah, and so is Cranberry River (a direct translation of the Ojibwe Mashkiigiminikaaniwi-ziibi. However, two other suspects emerge. Bark Bay (the large bay between Cornucopia and Herbster) is shown as Apakwaani-wiikwedong, and the mouth of the Flagg River (Port Wing) is Gaa-apakwaanikaaning.

On the surface, the Port Wing spelling was closer to Warren’s, but with “Gaa” being a droppable prefix, it wasn’t a big difference. The atlas uses the root word apakwe to translate both as “the place for getting roofing-bark,” Apakwe in this sense referring to rolls of birch bark covering a wigwam. For me it was a no-brainer. Bark Bay is the biggest, most defined bay in the area. Port Wing’s harbor is really more of a swamp on relatively straight shoreline. Plus, Bark Bay has the word “bark” right in it. Bark River goes into Bark Bay which is protected by Bark Point. Bark, bark, bark–roofing bark–Kapukwiekah–done.

Cornucopia had lost its one historical event, but it wasn’t so bad. Even though Bark Bay is closer to Herbster, it’s really between the two communities. I was even ready to suggest taking the word “Siskiwit” off the sign and giving it to Herbster. I mean, at least it wasn’t Port Wing, right?

Over the next few years, it seemed my Bark Bay suspicions were confirmed. I encountered Joseph Nicollet’s 1843 map of the region:

Then in 2009, Theresa Schenck of the University of Wisconsin-Madison released an annotated second edition of Warren’s History. Dr. Schenck is a Blackfeet tribal member but is also part Ojibwe from Lac Courte Oreilles. She is, without doubt, the most knowledgeable and thorough researcher currently working with written records of Ojibwe history. In her edition of Warren, the story begins on page 83, and she clearly has Kah-puk-wi-e-kah footnoted as Bark Bay–mystery solved!

But maybe not. Just this past year, Dr. Schenck edited and annotated the first published version of The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849. Ely was a young Protestant missionary working for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) in the Ojibwe communities of Sandy Lake, Fond du Lac, and Pokegama on the St. Croix. He worked under Rev. Sherman Hall of La Pointe, and made several trips to the island from Fond du Lac and the Brule River. He mentions the places along the way by what they were called in the 1830s and 40s. At one point he gets lost in the woods northwest of La Pointe, but he finds his way to the Siscoueka sibi (Siskiwit River). Elsewhere are references to the Sand, Cranberry, Iron, and “Bruley” Rivers, sometimes by their Ojibwe names and sometimes translated.

On almost all of these trips, he mentions passing or stopping at Gaapukuaieka, and to Ely and all those around him, Gaapukuaieka means the mouth of the Flagg River (Port Wing).

There is no doubt after reading Ely. Gaapukuaieka is a well-known seasonal camp for the Fond du Lac and La Pointe bands and a landmark and stopover on the route between those two important Ojibwe villages. Bark Bay is ruled out, as it is referred to repeatedly as Wiigwaas Point/Bay, referring to birch bark more generally. The word apakwe comes up in this book not in reference to bark, but as the word for rushes or cattails that are woven into mats. Ely even offers “flagg” as the English equivalent for this material. A quick dictionary search confirmed this meaning. Gaapukuaieka is Port Wing, and the name of the Flagg River refers to the abundance of cattails and rushes.

My guess is that the good citizens of Cornucopia asked the State Historical Society to put up a historical marker in 1955. Since no one could think of any history that happened in Cornucopia, they just pulled something from Warren assuming no one would ever check up on it. Now Cornucopia not just faces losing its only historical event, it faces the double-indignity of losing it to Port Wing.

William Whipple Warren (1825-1853) wrote down the story of Bayaaswaa from the oral history of the chief’s descendents.

So what really happened here?

Because the oral histories in Warren’s book largely lack dates, they can be hard to place in time. However, there are a few clues for when this tragedy may have happened. First, we need a little background on the conflict between the “Fox” and Ojibwe.

The Fox are the Meskwaki, a nation the Ojibwe called the Odagaamiig or “people on the other shore.” Since the 19th-century, they have been known along with the Sauk as the “Sac and Fox.” Today, they have reservations in Iowa, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Warfare between the Chequamegon Ojibwe and the Meskwaki broke out in the second half of the 17th-century. At that time, the main Meskwaki village was on the Fox River near Green Bay. However, the Meskwaki frequently made their way up the Wisconsin River to the Ontonagon and other parts of what is now north-central Wisconsin. This territory included areas like Lac du Flambeau, Mole Lake, and Lac Vieux Desert. The Ojibwe on the Lake Superior shore also wanted to hunt these lands, and war broke out. The Dakota Sioux were also involved in this struggle for northern Wisconsin, but there isn’t room for them in this post.

In theory, the Meskwaki and Ojibwe were both part of a huge coalition of nations ruled by New France, and joined in trade and military cooperation against the Five Nations or Iroquois Confederacy. In reality, the French at distant Quebec had no control over large western nations like the Ojibwe and Meskwaki regardless of what European maps said about a French empire in the Great Lakes. The Ojibwe and Meskwaki pursued their own politics and their own interests. In fact, it was the French who ended up being pulled into the Ojibwe war.

What history calls the “Fox Wars” (roughly 1712-1716 and 1728-1733) were a series of battles between the Meskwaki (and occasionally their Mascouten, Kickapoo, and Sauk relatives) against everyone else in the French alliance. For the Ojibwe of Chequamegon, this fight started several decades earlier, but history dates the beginning at the point when everyone else got involved.

By the end of it, the Meskwaki were decimated and had to withdraw from northern Wisconsin and seek shelter with the Sauk. The only thing that kept them from being totally eradicated was the unwillingness of their Indian enemies to continue the fighting (the French, on the other hand, wanted a complete genocide). The Fox Wars left northern Wisconsin open for Ojibwe expansion–though the Dakota would have something to say about that.

So, where does this story of father and son fit? Warren, as told by the descendents of the two men, describes this incident as the pivotal event in the mid-18th century Ojibwe expansion outward from Lake Superior. He claims the war party that avenged the old chief took possession of the former Meskwaki villages, and also established Fond du Lac as a foothold toward the Dakota lands.

According to Warren, the child took his father’s name Bi-aus-wah (Bayaaswaa) and settled at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi. From Sandy Lake, the Ojibwe systematically took control of all the major Dakota villages in what is now northern Minnesota. This younger Bayaaswaa was widely regarded as a great and just leader who tried to promote peace and “rules of engagement” to stop the sort of kidnapping and torture that he faced as a child. Bayaaswaa’s leadership brought prestige to his Loon Clan, and future La Pointe leaders like Andeg-wiiyaas (Crow’s Meat) and Bizhiki (Buffalo), were Loons.

So, how much of this is true, and how much are we relying on Warren for this story? It’s hard to say. The younger Bayaaswaa definitely appears in both oral and written sources as an influential Sandy Lake chief. His son Gaa-dawaabide (aka. Breche or Broken Tooth) became a well-known chief in his own right. Both men are reported to have lived long lives. Broken Tooth’s son, Maangozid (Loon’s Foot) of Fond du Lac, was one of several grandsons of Bayaaswaa alive in Warren’s time and there’s a good chance he was one of Warren’s informants.

Caw-taa-waa-be-ta, Or The Snagle’d Tooth by James Otto Lewis, 1825 (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: WHi-26732) “Broken Tooth” was the son of Bayaaswaa the younger and the grandson of the chief who gave his life. Lewis was self-taught, and all of his portraits have the same grotesque or cartoonish look that this one does.

Within a few years of Warren’s work, Maangozid described his family history to the German travel writer Johann Kohl. This family history is worth its own post, so I won’t get into too much detail here, but it’s important to mention that Maangozid knew and remembered his grandfather. Broken Tooth, Maangozid’s father and Younger Bayaaswaa’s son, is thought to have been born in the 1750s. This all means that it is totally possible that the entire 130-year gap between Warren and the Fox Wars is spanned by the lifetimes of just these three men. This also makes it totally plausible that the younger Bayaaswaa was born in the 1710s or 20s and would have been a child during the Fox Wars.

My guess is that the attack at Gaapukuaieka and the death of the elder Bayaaswaa occurred during the second Fox War, and that the progress of the avenging war party into the disputed territories coincides with the decimation of the Meskwaki as described by the French records. While I don’t think the entire Ojibwe expansion of the 1700s can be attributed to this event, Ojibwe people in the 1850s, over a century later still regarded it as a highly-significant symbolic moment in their history.

So what’s to be done?

[I was going to do some more Port Wing jokes here, but writing about war, torture, and genocide changes the tone of a post very quickly.]

I would like to see the people of Cornucopia and Port Wing get together with the Sandy Lake, Fond du Lac, and Red Cliff bands and possibly the Meskwaki Nation, to put a memorial in its proper place. It should be more than a wooden marker. It needs to recognize not only the historical significance, but also the fact that many people died on that day and in the larger war. This is a story that should be known in our area, and known accurately.

If Cornucopia still needs a history, we can put up a marker for the time we beat Port Wing in the tournament.